Abstract

For more than two decades, there have been extensive studies of experience-based neural plasticity exploring effective applications of brain plasticity for cognitive and motor development. Research suggests that human brains continuously undergo structural reorganization and functional changes in response to stimulations or training. From a developmental point of view, the assumption of lifespan brain plasticity has been extended to older adults in terms of the benefits of cognitive training and physical therapy. To summarize recent developments, first, we introduce the concept of neural plasticity from a developmental perspective. Secondly, we note that motor learning often refers to deliberate practice and the resulting performance enhancement and adaptability. We discuss the close interplay between neural plasticity, motor learning and cognitive aging. Thirdly, we review research on motor skill acquisition in older adults with, and without, impairments relative to aging-related cognitive decline. Finally, to enhance future research and application, we highlight the implications of neural plasticity in skills learning and cognitive rehabilitation for the aging population.

Keywords: cognitive development, geriatric rehabilitation, motor performance, movement-dependent neural plasticity, skill acquisition

Introduction

Functional decline is evident in cognitive, motor, social, psychological, physical domains. Older adults often experience greater anxiety, poorer memory and attention, slower processing speeds; motor control and learning capabilities decreased; greater behavioral variability is usually observed. These areas of decline collectively cause neurodegenerative disorders like mild cognitive impairment (MCI), Alzheimer’s disease (AD), or AD-related dementia. The compromised functionality reduces the quality of life and causes great concerns in the geriatric and gerontological communities. However, functional deterioration is not inevitable. Behavioral improvements are likely to occur while having an active lifestyle that is a key to reduce the negative impact of cognitive-motor aging on daily functions and to enhance the quality of life. The development of effective diagnostic tools, better intervention strategies and technologies is of the utmost importance for geriatric researchers and practitioners (Yan and Zhou, 2009; Ren et al., 2013).

The gradual age-related decline in neural-behavioral functionality considerably impacts adults aged 65 or older (Yan et al., 1998, 2000). It is encouraging, however, that motor, physical and mental activities often promote brain fitness or health (e.g., the capacity to learn, improve and meet various cognitive demands) and motor abilities for coping with daily challenges. Actively engaging in physical, motor or intellectual exercises, or deliberately receiving multisensory stimulations, can prevent functional decline and preserve cognitive functions. In general, cognitive and motor performance deteriorates considerably as a result of an inactive lifestyle, biological aging and cognitive impairments (Yan, 1999; Teri et al., 2003; Yan and Dick, 2006; Liu et al., 2013).

Although the exact role of regular physical and mental exercise for brain fitness is unclear, there is a consensus that cognitive-motor activities or stimulations facilitate neuro-protection (Hillman et al., 2008; Taubert et al., 2010). One of the processes is to strengthen experience-based neural plasticity through deliberate practice (Rakic, 2002; Trachtenberg et al., 2002; Colcombe et al., 2004; DeFelipe, 2006). Structural and functional changes (neural reorganizations) of the brain include the development of new neurons (neurogenesis), the generation of new glial cells (gliogenesis), strengthening of existing connections or growth of new synapses (synaptogenesis), and the creation of new blood vessels in the brain (Buonomano and Merzenich, 1998; Cotman and Berchtold, 2002; Dong and Greenough, 2004; Ming and Song, 2005; Voelcker-Rehage and Willimczik, 2006; Ponti et al., 2008). Brain plasticity is a lifetime developmental process and continues to play a significant role in older adulthood. Cognitive and motor activities have to be intellectually stimulating and physically appropriate to bring about maximal benefits to the aging brain (Colcombe et al., 2003, 2006).

The increasing number of older adults and those who develop MCI or AD pose great challenges to our society (Brookmeyer et al., 2007). Effective interventions must be taken to reduce the impact of functional decline. We summarize recent knowledge of brain plasticity and highlight the applications of developmental studies on cognitive training and movement therapy. We discuss the close relationship between neural plasticity, motor learning and cognitive aging. The goal is to integrate empirical results focusing on motor skills acquisition and the benefits of motor practice or exercise in older adults.

Neural plasticity

Cognitive and motor development plays an essential role in human brain maturity and a wide variety of daily functions (Elbert et al., 1995; Barnett et al., 2009). To make better sense of the close interactions between cognitive and motor skills across the lifespan, identifying the biological and environmental factors of human development is of particular interest (Quartz and Sejnowski, 1997; Diamond, 2000; Johnson, 2003; Ronnlund et al., 2005). Over the past few decades, researchers have made substantial efforts and progress in understanding the brain mechanisms of functional changes and structural reorganizations in people at varying developmental stages. Lifetime cognitive and motor development is closely related to each other (Samuelson and Smith, 2000; Yan et al., 2000; Johnston et al., 2001; Salthouse and Davis, 2006). Essentially, brain plasticity, neural maturation and cognitive development play an important role in cognitive and motor learning (Ungerleider et al., 2002; Lacourse et al., 2004; Wright and Harding, 2004).

Neural plasticity (also known as neuroplasticity, brain plasticity, cortical plasticity, cortical re-mapping) is an inherent characteristic or ability for lifelong skills learning and relearning. Specifically, neural plasticity refers to the capacity of the central nervous system (CNS) to alter its existing cortical structures (anatomy, organization) and functions (physiological mechanisms or processes) in response to experience, learning, training, or injury (Hubel and Wiesel, 1970; Kolb and Whishaw, 1998; Wall et al., 2002; Kolb et al., 2003; Ballantyne et al., 2008). When describing neural structures and functions, the cortical sensory organizations are usually portrayed as mappings where specific sensory inputs project to given cortical locations to form sensory-based neural representations (Buonomano and Merzenich, 1998). When an individual acquires novel skills or information, the newly obtained experience will alter the neural maps, networks, pathways or circuits made up of countless neurons and synapses (Wall et al., 2002). Neural plasticity is, therefore, a biological foundation of the learning brain (Taubert et al., 2010).

Experience-dependent changes in the lower neocortical regions can reshape the activation patterns and the anatomy of the cerebral cortex (Wall et al., 2002). Sensory input, knowledge and motor learning activities stimulate cortical changes (Rakic, 2002; Taubert et al., 2010). In skill learning or repeated exposure to stimulations and experiences, relevant neurons often “fire together [and] wire together”. The associated neurons of a given response will be activated simultaneously in response to similar stimuli in the future. Learning endeavors or experiences modify the existing cortical structures or mechanisms via neurogenesis, gliogenesis, or by changing the strength of inter-neuronal connections (synaptogenesis) (Buonomano and Merzenich, 1998; Cotman and Berchtold, 2002; Dong and Greenough, 2004; Voelcker-Rehage and Willimczik, 2006; Ponti et al., 2008).

Learning-dependent neural plasticity is a lifetime developmental process in which age-related critical periods or time windows seem to exist for significant cortical reorganization (Buonomano and Merzenich, 1998; Cotman and Berchtold, 2002; Rakic, 2002; Dong and Greenough, 2004; Voelcker-Rehage and Willimczik, 2006; Ponti et al., 2008). During the critical periods in early life, among competing sensory inputs of a given experience, neural representation of the most critical aspect is formed and consolidated (e.g., the hippocampus helps the formation of long-term memories) (Hensch, 2005). In contrast, experiences may induce fewer changes during non-critical periods of brain development. Young children may gain more from skill learning during the age-sensitive periods than their older peers (Ito, 2004). Developing brains may have a greater potential to be trained or are more flexible in skills learning than developed brains (Kolb, 2000; Bunge and Wright, 2007). Training or treating children with certain developmental disorders during sensitive periods can maximize the benefits of neural plasticity and skill learning, which is important for their rehabilitation (Yan et al., 2002; Ito, 2004).

Sensory networks may be immutable beyond the critical periods of cortical plasticity (Ponti et al., 2008). However, experiences still enhance cognitive and motor functions via synaptogenesis and neurogenesis in certain brain areas, such as the hippocampus and cerebellum. Brain plasticity may be an age-related, age-dependent, or age-independent developmental process (Kolb et al., 1998). Instead of being a unitary process, experience-based neural plasticity is dynamic: varying as a function of cortical regions, time, and types of sensory or motor learning (Quartz and Sejnowski, 1997; Johnson, 2003). Understanding experience-related neural plasticity within a developmental framework along with the optimal timing of skills training or rehabilitation for individuals at different ages certainly has clinical and educational relevance. With the understanding of brain plasticity, for instance, clinicians can effectively assess and treat developmental disorders (e.g., developmental coordination disorders (DCD), and developmental dyspraxia, a kind of motor learning difficulty in children) and aging-related dysfunctions (e.g., MCI, AD, or dementia). Instructors can teach developmentally appropriate skills to children (Yan et al., 2002; Ito, 2004). Without doubt, there are pressing and increasing demands for the development of more effective approaches for older adults who suffer from cognitive or motor deficiencies (Yan and Zhou, 2009; Belleville et al., 2011; Hill et al., 2011; Ren et al., 2013).

The next question concerns the length of learning that can induce activity-dependent neural plasticity in macro- or micro-structures. Developed brains may restructure themselves due to extensive or rigorous skill learning lasting months or following a short period of practice (Taubert et al., 2010). A remarkable increase of gray matter volume was observed in the prefrontal, frontal and parietal regions while the learners were acquiring a balance-control skill. Changes in fractional anisotropy of the related white matter were observed following skill learning. Even minor adjustments in the training experience result in structural modifications and the rebuilding of functional capacities. Furthermore, a few weeks of training in mice led to the formation and removal of synapses, and a heightened level of synapse turnover. These changes may collectively cause an adaptive remapping of neural pathways (Trachtenberg et al., 2002). When a given stimulus is repeatedly and intentionally coupled with the consistent activation patterns of a set of neurons during the critical period, the neural representation of that stimulus is reinforced (Zhou and Merzenich, 2007).

Therefore, activity-dependent neural plasticity can be induced by both lengthy-extensive and brief-intensive practice (Ziemann et al., 2004). In learning a complex visuomotor task, older and younger learners showed similar increases in corticomotor excitability after several minutes of training, reflecting similar cognitive-motor plasticity of the two age groups (Cirillo et al., 2011). When younger adults actively engaged in a learning and memory task for months, the size of gray matter expanded remarkably in the posterior and lateral parietal sites (Draganski et al., 2006). Task-specific memory capacity, developed via a dynamic process of information encoding and retrieval, results in greater functional plasticity in the multi-level memory networks. For elite athletes, superior sport expertise and performance are the outcomes of long-term training and cortical-spinal plasticity (the “Olympic brains”) (Nielsen and Cohen, 2008). Sport-specific experiences and the resultant neural enhancements contribute to an effective use of sensory information in judgments or decision-making and better motor memory consolidation in expert players.

Mental exercise is also reported to have a positive impact on long-term neural activities (Lutz et al., 2004). For example, adaptive working memory training increased neural efficiency in working memory tasks in older adults (Brehmer et al., 2011). Working memory training induced white matter increases that were correlated with performance improvements in older adults (Engvig et al., 2012). In addition, multitasking was enhanced in older adults after video game training. The benefits can be transferred to non-trained sustained attention and working memory tasks (Anguera et al., 2013). It is thought that complex training environments (e.g., video games) are a key for successful cognitive training and interventions (Bavelier et al., 2012).

Evidence shows that experience-dependent neural plasticity can be stimulated both by physical and mental practice to different extents, depending on the training contents and the abilities to test. Compared to physical training, greater improvements in executive functions were observed after cognitive training (Gajewski and Falkenstein, 2012). Cardiovascular and coordination training led to differential changes in sensorimotor and visual-spatial networks (Voelcker-Rehage et al., 2011). These observations are important for both cognitive improvements and motor learning.

Motor learning

Motor learning is conceptualized as the process of deliberate or goal-directed practice that results in long-lasting performance stabilization and adaptation (Schmidt and Lee, 2005). Motor learning and relearning are lifelong activities directly associated with experience-related brain plasticity (Ungerleider et al., 2002; Voelcker-Rehage and Willimczik, 2006; Taubert et al., 2010). Recent studies reported that motor skills can be learned both in on- and off-line modes. On-line learning (also known as within-session practice-dependent acquisition) occurs when a learner practices a given skill or a set of skills. Upon completion of the task-specific practice, a learner continues to acquire or stabilize a given skill or a set of skills. In particular, motor learning would be more pronounced after an optimal post-practice interval during which a learner is sleeping or napping. This mode of motor learning refers to off-line learning (also known as between-session practice-independent performance enhancement). Nighttime sleeping or daytime napping is required for such a learning mode. In motor behavior literature, motor skill acquisition is said to be composed of these two closely related learning mechanisms (Newell, 1991; Sanes, 2000, 2003; Thomas et al., 2000; Cohen et al., 2005; Yan et al., 2009; Debarnot et al., 2011; Wilhelm et al., 2012). Both practice and sleeping facilitate motor skills learning.

Motor learning takes place when a learner repeatedly and actively engages in physical or mental practice of a given skill or a set of skills (Schmidt and Bjork, 1992). Researchers of on-line learning primarily examine how learners of different ages or skill levels, in different learning conditions, acquire a variety of motor or cognitive skills during practice. If on-line learning occurs, skill improvements can be observed during the practice phase and can be captured in immediate or delayed retention or transfer tests. Over the last few decades, substantial evidence has shown that on-line learning benefits children and younger adults (Thomas et al., 1979; Newell, 1991; Deutsch and Newell, 2001, 2005; Schmidt and Lee, 2005; Magill, 2011). Despite having cognitive-motor deficits (Yan, 2000; Schaie, 2004; Dennis and Cabeza, 2008), older learners are able to use skill feedback (e.g., knowledge of results (KR), feedback about the outcome of a motor skill) for motor learning to an extent similar to that of younger adults (Swanson and Lee, 1992; Carnahan et al., 1993, 1996; Wishart and Lee, 1997; Schiffman et al., 2002). However, Liu et al. (2013) recently showed that older learners with cognitive-motor deficiency demonstrated limited on-line learning as reflected in small improvements of movement time (MT, time difference between onset and offset of an action) and small reductions in timing error (TE, time gap between the target time and MT). In retention tests, older adults with intact cognitive and motor functions outperformed those who had relatively poorer scores in an eye-hand-coordination test (finger tapping), the Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE), and the Trail Making Test (TMT-A and B). Cognitive, neural and motor deficiencies in older adults might explain their compromised on-line motor learning (Albert, 1997; Seidler, 2006; Yan et al., 2008; Yan and Zhou, 2009; Ren et al., 2013).

One important finding of Liu et al. (2013) was that the interval between each learning trial and the delivery of KR, and the interval between the delivery of KR and the next learning trial, were critical for successful on-line motor timing. For cognitively unhealthy older learners, longer intervals (6, 12 s) reduced the beneficial effect of KR on on-line learning to a greater degree than on the learning of their healthy counterparts and younger adults. Poorer attention, concentration and working memory, and decreased information processing speeds in older adults may be the reasons. For instance, cognitive aging is typically associated with reductions of attention and memory capacities (Salthouse, 1996; Chao and Knight, 1997; Maylor, 1998; Maylor and Lavie, 1998; Johnson et al., 2002; Hedden and Gabrieli, 2004; Anguera et al., 2011). Older learners might fail to register the given KR or keep the action-related information active for a long period of time. This working memory problem is the “binding deficit” of older learners in using KR for on-line learning (Johnson et al., 2002). Furthermore, Anguera et al. (2011) attributed the reduced learning efficiency in older adults to their inability to couple KR for a given trial with the neural representation of the skill. Interactions of cognitive and motor aging, environment and neural processes collectively contribute to the observed differences in motor learning between older and younger adults. In the case of cognitively healthy older adults, without additional practice, their newly acquired motor experiences or memories could be retrievable for a minimum of 2 years after learning (Smith et al., 2005). Thus, aging is not necessarily associated with memory deterioration, but aging-related cognitive-motor dysfunction plays a central role in the decline of on-line motor learning.

Based on the results, a subsequent question to consider is how motor training (on- or off-line) strengthens memory and executive functions that are crucial for older learners suffering from functional decline (Baddeley, 1996, 2002; Anderson et al., 1998; Seidler, 2007). The second question is whether sleep-based off-line motor learning enhances brain functionality of older adults. The third question is how physical exercise, motor practice and skill learning improve motor performance and brain fitness based on the neural plasticity mechanisms aforementioned. Perhaps off-line learning is more profitable than on-line learning in motor learning in older learners. There is less interference with learning during sleep; the off-line learning mode may allow sufficient time or cognitive resources to process and consolidate skill-related information into long-term memories (Yan et al., 2009).

While motor skills become better during practice sessions, skills continue improving between practice sessions, particularly during post-practice sleeping (Walker et al., 2003; Walker and Stickgold, 2004; Walker, 2005, 2009). Different neural mechanisms for over-day and over-night off-line learning modes may exist (Robertson et al., 2004, 2005). Contrary to our expectation that sleep-based learning would be more advantageous than on-line learning, older learners showed small gains in skill retrieval after sleep (Yan et al., 2009). Brown et al. (2009) suggested that over-night sleeping had little benefit for motor learning in older adults with intact motor or cognitive functions. The findings of Yan et al. (2009) were inconsistent with the learning effects observed in children or young adults and might suggest a reduction of neural plasticity in older adults (Thomas et al., 2000; Wilhelm et al., 2008, 2012; Yan et al., 2009). Discrepancies of results are possibly due to quality, timing, or duration of sleep, experimental design or interference from other experiences (Rickard et al., 2008; Cai and Rickard, 2009). For example, during the 24 h post-practice interval, there was no control over the activities or schedules of the learners, which might have affected the learning of older adults more than that of their younger peers (Brown et al., 2009). Greater individual differences in the cognitive and motor capacities of older adults may also hinder their on- and off-line motor learning (Yan et al., 2009). Subsequent research is warranted to clarify these issues.

Finally, we discuss how and why physical practice and mental training improve motor skills and brain fitness based on the concept of brain plasticity. Two essential questions need to be answered: what are the neural changes associated with motor learning? How does neural plasticity contribute to motor learning? From a biological viewpoint, skills learning or relearning is associated with neural plasticity for the survival and development of a species. Structural and functional alternations take place in the neural system throughout the lifetime (Ungerleider et al., 2002; Voelcker-Rehage and Willimczik, 2006; Taubert et al., 2010). Motor learning results in neurobehavioral changes, making the neural system shift from a conscious control (central, command-driven, top-down) to an unconscious (peripheral, feedback-based, button-up) control mode; the neural representations of the skill are formed during this process (Willingham, 1998). The flexible or changeable nature of cortical reorganization is the basis of skill learning.

Physical exercise brings about changes to brain structures and functions. An animal study suggested that physical exercise or motor learning can increase the thickness of the motor cortex (Anderson et al., 2002). An increased density of blood vessels and the development of synapses in the cerebellum were observed following physical exercise (Black et al., 1990). Physical exercise contributes to memory formation and increases the number of neurons and synapses (dentate gyrus) in both young and old mice (van Praag et al., 1999a,b, 2005). Deliberate training, or changing the surrounding environment, enhances cortical reorganization and functions that facilitate memory formation in rats through altering gene expression and the concentration of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor, BDNF (Briones et al., 2004; Farmer et al., 2004; Berchtold et al., 2005). The benefits of physical and mental training are largely mediated by enhanced BDNF signaling (Korol et al., 2013); whereas increased temporal lobe connectivity after aerobic training is associated with BDNF, insulin-like growth factor type 1 (IGF-1), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF; Voss et al., 2013).

Environmental factors such as exercise, training, injuries and rehabilitation change neural plasticity by varying degrees in different cortical regions. As a result of long-term professional training, the cerebral structures and functions of expert musicians show significant changes. The cortical alterations may start in the early stages of training, or life, and develop continuously in higher regions later, reflecting rapid and remarkable changes in the critical period of neural plasticity (Schlaug, 2001). In humans, intentional exercise and cortical plasticity are closely related; exercise contributes to better memory by elevating BDNF (Vaynman et al., 2004, 2006). At the behavioral level, older adults demonstrated “motor plasticity” or the ability to acquire new motor skills to an extent similar to that of younger peers (Roller et al., 2002; Voelcker-Rehage and Willimczik, 2006). Skill differences between younger and older adults in motor learning should reflect the ability of CNS to reduce neural noise and coordinate agonist-antagonist muscle activities, but not older adults’ inferior potential to learn or relearn (Christou et al., 2007).

Furthermore, computer-based practice significantly enhances cognitive rehabilitation in healthy older adults; the beneficial effects of training can be sustained for 3 months. The results bear important implications about the “reversibility” of older brains (Mahncke et al., 2006). Injury studies support the notion of structural and functional reversibility of the higher regions of CNS. For instance, certain therapeutic treatments or training can repair or recover the vanished, or reduced, brain functions caused by injury (Stein and Hoffman, 2003; Wieloch and Nikolich, 2006). Given the potential value of plasticity-based skill learning and the contribution of motor practice to functional neural regeneration, these studies have important implications for older adults. Specifically, older adults normally suffer from functional deficiencies. The plasticity-based motor learning or training should integrate multiple tasks or activities to be implemented at multiple skill levels (fundamental, daily, motor, and special skills) and with multisensory inputs (Nojima et al., 2012). Training regimens should be specific, function-oriented, precise, simple, and combined with daily tasks (e.g., locomotion, balance control or fall prevention). Individual differences in cognitive and motor functions in older adults should be considered when designing and implementing training programs. Future research to identify major barriers and facilitators to brain fitness and motor functionality in older adults is integral to cognitive-motor skill learning and rehabilitation. An apparent challenge now lies in the search for an optimal therapeutic approach to enhance skills learning in older adults.

Cognitive aging

While discussing brain fitness or motor ability of older adults, we describe the developmental pattern and define “normal aging”, and “cognitive aging”. We will also answer the questions, “what is successful aging?” and, “how do older adults achieve successful aging through exercise or practice?” Importantly, we address the features of learning and relearning in older adults who are cognitively and motorically intact or impaired. Finally, the links between physical exercise and brain function in older adults will be highlighted.

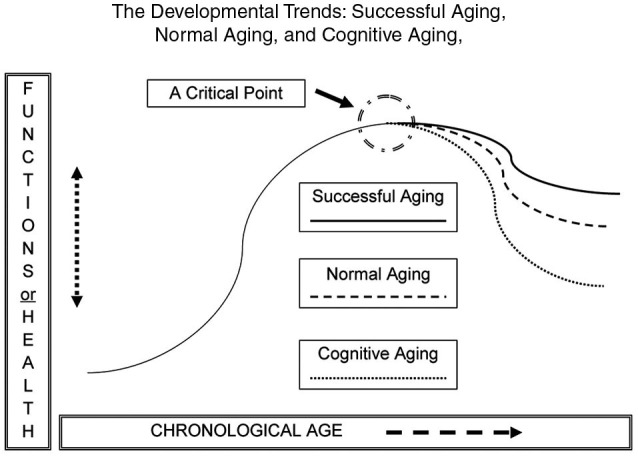

Figure 1 shows an inverted U-shaped pattern of motor and cognitive ability and three possible descending paths in older adulthood: normal aging; cognitive aging; and successful aging (Yan et al., 1998, 2000; Yan and Zhou, 2009). Functional capacity increases during childhood and young adulthood and decreases in older adulthood. The slope of functional changes largely depends on individual differences in genetics, personality, motivation, lifestyle, socio-cultural background, exercise opportunities and learning experiences. Variations in the curves are collective or interactive outcomes of these biological and environmental factors.

Figure 1.

The likely developmental trends across the human lifespan (an inverted U-shape). The down-turning paths are for normal aging, cognitive aging, and successful aging in motor and cognitive functions. Overall, the functional curves are moving downwards during older adulthood. The slope of functional change is subject to a number of biological and environmental factors.

From a lifespan developmental viewpoint, normal aging or aging literally means that an individual may experience multiple aspects of expected change (e.g., neural, biological, physiological, psychological or social) during the passage of time, from conception to death. A functional increment or progression can be seen in early life (childhood, youth, and young adulthood), and even in older stages; regression takes place at later stages (Bowen and Atwood, 2004). Cognitive aging is a set of gradual and functional regressions of cognitive abilities (e.g., attention, memory, reasoning, decision-making and processing speed; Salthouse, 2004). Steady decline of cognitive ability can be observed across the lifespan, and it accelerates after young or middle adulthood (Salthouse, 2009). Older adults also experience a major decline in movement functionality, such as reduced walking speed, poorer eye-hand coordination, and compromised learning abilities (Yan, 1999, 2000; Yan et al., 2009; Studenski et al., 2011).

Functional deteriorations in cognitive and motor domains are of the greatest concern to many older adults and the people around them. However, Figure 1 also shows the third and optimal path of development in the “getting older” process. This ideal course of development is successful aging, owing to the contributions of neural or cognitive reserves of older adults with an active lifestyle (Arbuckle et al., 1998; Stern et al., 2003; Daffner, 2010). Contrary to the greater functional decline in older adults in the categories of “cognitive aging” or “normal aging”, those in the category of “successful aging” suffer less from declining abilities and enjoy a relatively higher level of cognitive wellness through the reorganization of brain networks (Sala-Llonch et al., 2012). The main characteristics of successful aging are “low probability of disease or disability, high cognitive and physical function capacity, and active engagement with life” (p. 433), along with others such as having greater life or emotional satisfaction, enjoying more learning opportunities, and participating in active social and intellectual activities (Rowe and Kahn, 1997; Chou and Chi, 2002; Strawbridge et al., 2002; Menec, 2003; Duay and Bryan, 2006).

Motor and cognitive functions seem to be fairly homogeneous in early life and gradually become more heterogeneous as humans approach the hypothetical “critical point”, and thereafter (Figure 1). Variations of cognitive and motor capacity lead to three possible trends in older adults (Rowe and Kahn, 1987; Yan et al., 2000). Attaining the state of successful aging is the goal to maximize the quality of life and reduce the negative impact of cognitive aging in older adults (Rowe and Kahn, 1987). Here we focus on the benefits of potential applications of training-induced neural plasticity in successful aging.

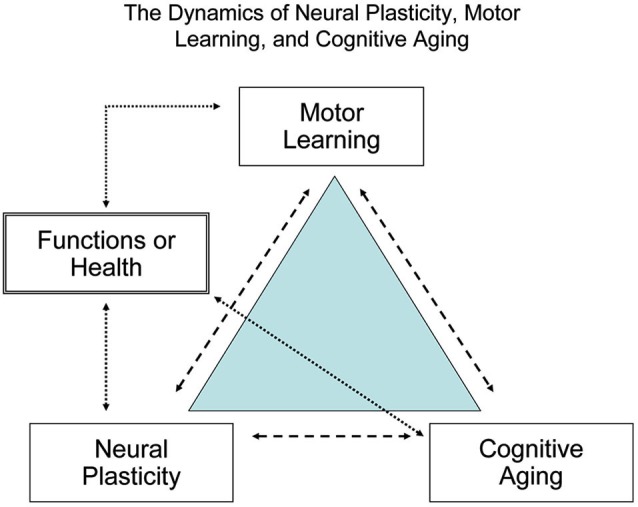

Figure 2 shows the dynamics of neural plasticity (the biological foundation for learning), motor learning or relearning (the process of acquiring or consolidating new or learned skills), and cognitive aging (the deteriorating capacities). Interactions of cognitive aging, experiences, environments and brain development collectively contribute to the observed discrepancies in motor and cognitive functions between younger and older learners. To achieve successful aging, regular cognitive and motor training is essential throughout the lifespan and especially for older adults who are at high risk of functional deterioration (Kramer et al., 2000, 2006).

Figure 2.

The dynamic relationship between brain plasticity, motor learning, and cognitive aging. To maximize human brain fitness and motor functions signaled by the quality of life and independence in daily activity, habitual cognitive and motor learning or practice is required across the lifespan, particularly for older adults.

Over the past three decades, there has been a large volume of research to delineate how exercise or motor practice improves neurocognitive function or wellness in older adults (Colcombe and Kramer, 2003). Of particular interest are the studies concerning how the brain responds to physical exercise or skill learning to improve neurocognitive functions in older adults. Kramer et al. (2006) reviewed cross-sectional, longitudinal and interventional research into the relationship between physical fitness and brain function in older adults (Kramer et al., 2006). The beneficial effects of aerobic fitness on executive functions and working memory in older adults were supported by several subsequent studies (Carlson et al., 1999; Yaffe et al., 2001; Barnes et al., 2003, 2007; Studenski et al., 2006). The benefits of vigorous exercise and motor learning for improving neurocognitive functions in older adults can be explained by one or all of the three theoretical accounts: information processing, executive functioning, and memory development (Clarkson-Smith and Hartley, 1989; Tomporowski and Hatfield, 2005). The robust relation between exercise and cognition apparently requires additional clarification: (1) exercise participation may contribute more to executive processes than to the other two domains (information processing and memory development); (2) genetic factors may play a critical role in identifying the target population at risk of cognitive impairment; and (3) the measurement of differences between subjects is critical. Brain processes are not often observable or detectible at behavioral level. However, neuroimaging techniques can show small changes in neural metabolism or activation to indicate major differences as the result of exercise or skills learning for neurocognitive functions.

Although studies have suggested the positive effects of exercise on cognitive functions in older adults, one of the prevailing problems was that many studies were cross-sectional ignoring time to time performance changes. A need for longitudinal-interventional studies became apparent. For instance, Yaffe et al. (2001) reported that when community-dwelling older women took cognitive tests 6 years after baseline tests, those who had higher physical activity levels showed less cognitive decline (2001). A decade-long study also showed that poorer fluid intelligence was associated with lower levels of physical activity; those who reported the lowest levels of activity in middle age were at the highest risk of cognitive decline later in life (Singh-Manoux et al., 2005). In a study over the course of 12 weeks, older adults in the walking group outperformed, in inhibitory control and selective attention, those who were not physically active. Therefore, a sustained exercise program can protect against cognitive decline in older adults (Kamijo et al., 2007).

Another question to ask is, “how can the required training or exercise (exercise modality, intensity, duration and frequency) be implemented in a meaningful and effective way to help older adults?” Some researchers classified research on exercise and brain health into four categories: (1) to determine frequency, intensity, type and level of physical activity for diverse aging populations; (2) to identify the major or realistic cognitive benefits by participating in physical activity; (3) to understand the psychological and physiological factors that influence physical activity participation both in healthy and unhealthy older adults; and (4) to promote appropriate interventions, establish practical evaluation criteria and develop policies to increase physical activity among those at risk of cognitive impairment (Prohaska and Peters, 2007). With the outcome of these studies, researchers can bridge the gap between research and the implementation of physical activity for brain health. Of course, the difficult question of how to implement exercise still remains to be answered; however, these studies offer some of the most important guidelines for physical exercise and behavioral enhancement in older adults.

Brain functionality has long been attributed to the maintenance of independence and a high quality of life in older adults (Kramer et al., 2000). The preservation of neurocognitive function during aging is crucial for maintaining the required capacities of neural pathways and cortical networks that control cognition and motor behaviors (Yan and Dick, 2006; Yan et al., 2008). Brain health or fitness is crucial for cognitive and motor functioning in older adults, and for protection against pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases such as AD (Cotman and Berchtold, 2002). For example, short-term intensive exercise or long-term regular training improves learning while preventing the progression of AD in mice by increasing BDNF protein and decreasing extracellular amyloid-β plaques (Adlard et al., 2004, 2005). In large-sample longitudinal investigations, Laurin et al. (2001) and Barnes et al. (2003) suggested that physical exercise could protect older adults from cognitive deterioration and, possibly, from dementia. Exercise improves vascular function, decreases obesity and reduces inflammatory markers to enhance brain health and functioning (Laurin et al., 2001; Barnes et al., 2007). Equally important, exercise prevents loss of neurons or neural dysfunction that ultimately leads to the development of dementia (Verghese et al., 2003, 2006; Barnes et al., 2007). Physical activity also helps reduce cognitive decline associated with long-term hormone replacement therapy in menopausal women (Erickson et al., 2007). Both exercise and environmental enrichment can ameliorate hippocampal aging by restoring neurogenesis and neuroimmune cytokine signaling in aged mice (Kumar et al., 2012; Speisman et al., 2013a,b).

Regarding the effects of exercise on brain plasticity, Colcombe et al. (2004) tested older adults ranging from 58 to 77 years in a cross-sectional study with VO2 (oxygen consumption), reaction time, cognitive tests, functional MRI (fMRI) measures. Very fit older adults outperformed those less fit in behavioral and neuroimaging parameters. Better cardiovascular fitness resulted in superior test performances on executive functions, suggesting exercise-dependent neural plasticity of the aging brain. By improving physical fitness, neural structure, synaptic plasticity and transmission can be strengthened.

Finally, we discuss our two experiments exploring motor control and learning in MCI and AD patients. MCI usually refers to the transitional or intermediate phase between cognitive aging and AD. Older adults with MCI are increasingly at risk of developing dementia (Petersen et al., 1999, 2000; Petersen, 2000). In the first study, we examined whether deliberate training can improve functional control and motor performance in healthy older adults and their AD and MCI peers (Yan and Dick, 2006). A ballistic aiming arm movement was the task to learn and test. Differences in MT, jerk (movement smoothness), and the percentage of primary sub-movement (a reflection of top-down or motor planning control) between subject groups across six blocks of tests provided critical evidence concerning motor control mechanisms. Surprisingly, as a result of motor learning, AD and MCI subjects demonstrated an increased programming control and more extended improvements in MT and movement smoothness than their healthy counterparts. In the subsequent study, a handwriting task was used to explore whether AD or MCI had impaired fine motor actions primarily controlled by small muscles or muscle groups (Yan et al., 2008). Results showed that cognitive disorders reduced the control efficiency of fine motor tasks in complex settings (combining wrist and finger movements), but not in simple settings (only requiring wrist or finger movements). The findings of both studies may not be directly associated with the effects of motor learning on brain health or neural plasticity. However, we certainly know more about how cognitive disorders impair motor control, its possible underlying mechanisms, and potential therapeutic interventions for affected older adults.

Future research

The human lifespan continues to increase and the general population is aging quickly. We highlight key theories and related research into neural plasticity and the application to cognitive training and movement therapy in older adults. We discuss the close relations between the neurodevelopmental characteristics of brain plasticity, motor learning and the functional changes associated with the aging processes (cognitive and successful aging). We emphasize the benefits of motor practice or physical exercise for both cognitively normal and impaired older adults. We propose ideas to enhance future geriatric research or practice for older adults. We suggest using off-line sleep-based motor learning and mindfulness training for older adults who may suffer from cognitive or motor disorders.

More attention should be paid to the contribution of sleep-based skills learning to cognitive and motor skills, and possibly to the physical and neural rehabilitation of older adults (Walker et al., 2003; Robertson et al., 2004, 2005; Walker and Stickgold, 2004; Walker, 2005, 2009; Yan et al., 2009). Although research in this area seems inconclusive, in that reduced capacity of off-line learning is sometimes observed in older learners, we believe that older adults should take advantage of their sleep (or nap) as a supplemental means to develop greater brain fitness. In fact, a number of factors may have confounded the reported insignificance of sleep benefits in older adults (Brown et al., 2009; Siengsukon and Boyd, 2009; Yan et al., 2009). Time-of-day of sleep (the circadian effect) or homeostasis (time since last sleep) may reduce memory consolidation and play an unknown part in off-line motor learning in older adults (Rickard et al., 2008; Cai and Rickard, 2009). Individual differences in cognitive and motor functionality in older adults may decrease the gain from sleep-based learning (Yan et al., 2009). Variation of sleep habits in older adults is an important factor requiring control in future research. Off-line learning or memory consolidation may contribute to older adults’ cognitive and motor functionality. For instance, cuing or re-arousing existing experiences during sleep may be used to facilitate memory consolidation (Rasch et al., 2007; Rudoy et al., 2009). These approaches may be worth trying in older adults.

Furthermore, mindfulness training or awareness meditation may also benefit cognitive and motor rehabilitation in older adults. Mindfulness training refers to the mind and body exercises that facilitate attention focus on the experience of current time. It helps participants reach internal peacefulness, mind-body integration or coupling, via meditation (Siegel, 2009). Importantly, the inner experience of mindfulness improves brain function, reminiscence and social connections, thereby contributing to better mental and physical wellness (Hölzel et al., 2008, 2011). In this regard, mindfulness training has clinical implications for cognitive or motor therapy in older adults. However, the mechanisms underlying the benefits of mindfulness training are still open to discussion. Mindfulness exercise may be useful to increase neuro-protection that older adults need.

Finally, we have three important points. The first is that participation in exercise is critical for preventing cognitive decline in older adults. Persistence maximizes the gains from physical activity (Neely and Bäckman, 1993; Dik et al., 2003). Secondly, physical activity should be realistic and easy to accomplish for older adults (e.g., deliberate walking, mind games, or leisure activities; Willis and Nesselroade, 1990; Hultsch et al., 1999; Scarmeas et al., 2001; Schooler and Mulatu, 2001; Ball et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2002; Wilson et al., 2002; Weuve et al., 2004). Last but not the least, as the use of technology becomes increasingly prevalent, more computer-driven technologies will be utilized in training or rehabilitating older adults. In recent years, computerized training has demonstrated promising benefits for improving memory, which can be maintained beyond the training period (Zelinski et al., 2011). The development of such training programs would definitely contribute to better cognitive and motor skills for older adults in future. All activities for older adults may enhance their cognitive-motor functionality due to brain plasticity and, eventually, increase their quality of life over a long period of time.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the reviewers for their comments and suggestions. This work was supported in part by Neuro-Academics Ltd., Hong Kong.

References

- Adlard P. A., Perreau V. M., Engesser-Cesar C., Cotman C. W. (2004). The timecourse of induction of brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA and protein in the rat hippocampus following voluntary exercise. Neurosci. Lett. 363, 43–48 10.1016/s0304-3940(04)00365-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adlard P. A., Perreau V. M., Pop V., Cotman C. W. (2005). Voluntary exercise decreases amyloid load in a transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 25, 4217–4221 10.1523/jneurosci.0496-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert M. S. (1997). The ageing brain: normal and abnormal memory. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 352, 1703–1709 10.1098/rstb.1997.0152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson B. J., Eckburg P. B., Relucio K. I. (2002). Alterations in the thickness of motor cortical subregions after motor-skill learning and exercise. Learn. Mem. 9, 1–9 10.1101/lm.43402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P. G., Mulder T., Nienhuis B., Hulstijn W. (1998). Are older adults more dependent on visual information in regulating self-motion than younger adults? J. Mot. Behav. 30, 104–113 10.1080/00222899809601328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anguera J. A., Boccanfuso J., Rintoul J. L., Al-Hashimi O., Faraji F., Janowich J., et al. (2013). Video game training enhances cognitive control in older adults. Nature 501, 97–101 10.1038/nature12486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anguera J. A., Reuter-Lorenz P. A., Willingham D. T., Seidler R. D. (2011). Failure to engage spatial working memory contributes to age-related declines in visuomotor learning. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 23, 11–25 10.1162/jocn.2010.21451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle T. Y., Maag U., Pushkar D., Chaikelson J. S. (1998). Individual differences in trajectory of intellectual development over 45 years of adulthood. Psychol. Aging 13, 663–675 10.1037/0882-7974.13.4.663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley A. (1996). Exploring the central executive. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. (Hove) 49, 5–28 10.1080/713755608 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley A. (2002). Is working memory still working? Eur. Psychol. 7, 85–97 10.1027//1016-9040.7.2.85 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ball K., Berch D. B., Helmers K. F., Jobel J. B., Leveck M. D., Marsiske M., et al. (2002). Effects of cognitive training interventions with older adults: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 288, 2271–2281 10.1001/jama.288.18.2271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballantyne A. O., Spilkin A., Hesselink J., Trauner D. A. (2008). Plasticity in the developing brain: intellectual, language and academic functions in children with ischaemic perinatal stroke. Brain 131, 2975–2985 10.1093/brain/awn176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes D. E., Whitmer R. A., Yaffe K. (2007). Physical activity and dementia: the need for prevention trials. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 35, 24–29 10.1097/jes.0b013e31802d6bc2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes D. E., Yaffe K., Satariano W. A., Tager I. B. (2003). A longitudinal study of cardiorespiratory fitness and cognitive function in healthy older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 51, 459–465 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51153.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett L. M., Van Beurden E., Morgan P. J., Brooks L. O., Beard J. R. (2009). Childhood motor skill proficiency as a predictor of adolescent physical activity. J. Adolesc. Health 44, 252–259 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavelier D., Green C. S., Pouget A., Schrater P. (2012). Brain plasticity through the life span: learning to learn and action video games. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 35, 391–416 10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-152832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belleville S., Clément F., Mellah S., Gilbert B., Fontaine F., Gauthier S. (2011). Training-related brain plasticity in subjects at risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 134, 1623–1634 10.1093/brain/awr037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berchtold N. C., Chinn G., Chou M., Kesslak J. P., Cotman C. W. (2005). Exercise primes a molecular memory for brain-derived neurotrophic factor protein induction in the rat hippocampus. Neuroscience 133, 853–861 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black J. E., Isaacs K. R., Anderson B. J., Alcantara A. A., Greenough W. T. (1990). Learning causes synaptogenesis, whereas motor activity causes angiogenesis, in cerebellar cortex of adult rats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 87, 5568–5572 10.1073/pnas.87.14.5568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen R. L., Atwood C. S. (2004). Living and dying for sex. Gerontology 50, 265–290 10.1159/000079125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brehmer Y., Rieckmann A., Bellander M., Westerberg H., Fischer H., Bäckman L. (2011). Neural correlates of training-related working-memory gains in old age. Neuroimage 58, 1110–1120 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.06.079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briones T. L., Klintsova A. Y., Greenough W. T. (2004). Stability of synaptic plasticity in the adult rat visual cortex induced by complex environment exposure. Brain Res. 1018, 130–135 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookmeyer R., Johnson E., Ziegler-Graham K., Arrighi H. M. (2007). Forecasting the global burden of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 3, 186–191 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.04.381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R. M., Robertson E. M., Press D. Z. (2009). Sequence skill acquisition and off-line learning in normal aging. PLoS One 4:e6683 10.1371/journal.pone.0006683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunge S. A., Wright S. B. (2007). Neurodevelopmental changes in working memory and cognitive control. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 17, 243–250 10.1016/j.conb.2007.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonomano D. V., Merzenich M. M. (1998). Cortical plasticity: from synapses to maps. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 21, 149–186 10.1146/annurev.neuro.21.1.149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai D. J., Rickard T. C. (2009). Reconsidering the role of sleep for motor memory. Behav. Neurosci. 123, 1153–1157 10.1037/a0017672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson M. C., Fried L. P., Xue Q. L., Bandeen-Roche K., Zeger S. L., Brandt J. (1999). Association between executive attention and physical functional performance in community-dwelling older women. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 54, S262–S270 10.1093/geronb/54b.5.s262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnahan H., Vandervoot A. A., Swanson L. R. (1993). “The influence of aging on motor learning,” in Sensorimotor Impairments in the Elderly, ed Stelmach G. (Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer; ), 41–56 [Google Scholar]

- Carnahan H., Vandervoot A. A., Swanson L. R. (1996). The influence of summary knowledge of results and aging on motor learning. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 67, 280–287 10.1080/02701367.1996.10607955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao L. L., Knight R. T. (1997). Prefrontal deficits in attention and inhibitory control with aging. Cereb. Cortex 7, 63–69 10.1093/cercor/7.1.63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K. L., Chi I. (2002). Successful aging among the young-old, old-old, and oldest-old Chinese. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 54, 1–14 10.2190/9k7t-6kxm-c0c6-3d64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christou E. A., Poston B., Enoka J. A., Enoka R. M. (2007). Different neural adjustments improve endpoint accuracy with practice in young and old adults. J. Neurophysiol. 97, 3340–3350 10.1152/jn.01138.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirillo J., Todd G., Semmler J. G. (2011). Corticomotor excitability and plasticity following complex visuomotor training in young and old adults. Eur. J. Neurosci. 34, 1847–1856 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07870.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson-Smith L., Hartley A. A. (1989). Relationships between physical exercise and cognitive abilities in older adults. Psychol. Aging 4, 183–189 10.1037/0882-7974.4.2.183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D. A., Pascual-Leone A., Pree D. Z., Robertson E. M. (2005). Off-line learning of motor skill memory: a double dissociation of goal and movement. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 102, 18237–18241 10.1073/pnas.0506072102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colcombe S. J., Erickson K. I., Raz N., Webb A. G., Cohen N. J., McAuley E., et al. (2003). Aerobic fitness reduces brain tissue loss in aging humans. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 58, M176–M180 10.1093/gerona/58.2.m176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colcombe S. J., Erickson K. I., Scalf P. E., Kim J. S., Prakash R., McAuley E., et al. (2006). Aerobic exercise training increases brain volume in aging humans. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 61, 1161–1170 10.1093/gerona/61.11.1166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colcombe S., Kramer A. F. (2003). Fitness effects on the cognitive function of older adults: a meta-analytic study. Psychol. Sci. 14, 125–130 10.1111/1467-9280.t01-1-01430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colcombe S. J., Kramer A. F., Erickson K. I., Scalf P., McAuley E., Cohen N. J., et al. (2004). Cardiovascular fitness, cortical plasticity, and aging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 101, 3316–3321 10.1073/pnas.0400266101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotman C. W., Berchtold N. C. (2002). Exercise: a behavioral intervention to enhance brain health and plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 25, 295–301 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02143-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daffner K. R. (2010). Promoting successful cognitive aging: a comprehensive review. J. Alzheimers Dis. 19, 1101–1122 10.3233/JAD-2010-1306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debarnot U., Castellani E., Valenza G., Sebastiani L., Guillot A. (2011). Daytime naps improve motor imagery learning. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 11, 541–550 10.3758/s13415-011-0052-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFelipe J. (2006). Brain plasticity and mental processes: cajal again. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7, 811–817 10.1038/nrn2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis N. A., Cabeza R. (2008). “Nenuoimaging of healthy cognitive aging,” in The Handbook of Aging and Cognition, 3rd Edn. eds Craik F. I. M., Salthouse T. A. (New York, NJ: Psychology Press; ), 1–54 [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch K. M., Newell K. M. (2001). Age differences in noise and variability of isometric force production. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 80, 392–408 10.1006/jecp.2001.2642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch K. M., Newell K. M. (2005). Noise, variability, and the development of children’s perceptual-motor skills. Dev. Rev. 25, 155–180 10.1016/j.dr.2004.09.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond A. (2000). Close interrelation of motor development and cognitive development and of the cerebellum and prefrontal cortex. Child Dev. 71, 44–56 10.1111/1467-8624.00117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dik M., Deeg D. J., Visser M., Jonker C. (2003). Early life physical activity and cognition at old age. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 25, 643–653 10.1076/jcen.25.5.643.14583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong W. K., Greenough W. T. (2004). Plasticity of nonneuronal brain tissue: roles in developmental disorders. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 10, 85–90 10.1002/mrdd.20016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draganski B., Gaser C., Kempermann G., Kuhn H. G., Winkler J., Büchel C., et al. (2006). Temporal and spatial dynamics of brain structure changes during extensive learning. J. Neurosci. 26, 6314–6317 10.1523/jneurosci.4628-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duay D. L., Bryan V. C. (2006). Senior adults’ perceptions of successful aging. Educ. Gerontol. 32, 423–445 10.1080/03601270600685636 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elbert T., Pantev C., Weinbruch C., Rockstroh B., Taub E. (1995). Increased cortical representation of the fingers of the left hand in string players. Science 270, 305–307 10.1126/science.270.5234.305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engvig A., Fjell A. M., Westlye L. T., Moberget T., Sundseth Ø., Larsen V. A., et al. (2012). Memory training impacts short-term changes in aging white matter: a longitudinal diffusion tensor imaging study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 33, 2390–2406 10.1002/hbm.21370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson K. I., Colcombe S. J., Elavsky S., McAuley E., Korol D. L., Scalf P. E., et al. (2007). Interactive effects of fitness and hormone treatment on brain health in postmenopausal women. Neurobiol. Aging 28, 179–185 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer J., Zhao X., van Praag H., Wodtke K., Gage F. H., Christie B. R. (2004). Effects of voluntary exercise on synaptic plasticity and gene expression in the dentate gyrus of adult male Sprague-Dawley rats in vivo. Neuroscience 124, 71–79 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.09.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajewski P. D., Falkenstein M. (2012). Training-induced improvement of response selection and error detection in aging assessed by task switching: effects of cognitive, physical, and relaxation training. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 6:130 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedden T., Gabrieli J. D. E. (2004). Insights into the ageing mind: a view from cognitive neuroscience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 5, 87–96 10.1038/nrn1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensch T. K. (2005). Critical period plasticity in local cortical circuits. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 877–888 10.1038/nrn1787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill N. L., Kolanowski A. M., Gill D. J. (2011). Plasticity in early Alzheimer’s disease: an opportunity for intervention. Top. Geriatr. Rehabil. 27, 257–267 10.1097/tgr.0b013e31821e588e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillman C. H., Erickson K. I., Kramer A. F. (2008). Be smart, exercise your heart: exercise effects on brain and cognition. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 58–65 10.1038/nrn2298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hölzel B. K., Carmodyc J., Vangela M., Congletona C., Yerramsettia S. M., Garda T., et al. (2011). Mindfulness practice leads to increases in regional brain gray matter density. Psychiatry Res. 191, 36–43 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hölzel B. K., Ott U., Gard T., Hempel H., Weygandt M., Morgen K., et al. (2008). Investigation of mindfulness meditation practitioners with voxel-based morphometry. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 3, 55–61 10.1093/scan/nsm038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubel D. H., Wiesel T. N. (1970). The period of susceptibility to the physiological effects of unilateral eye closure in kittens. J. Physiol. 206, 419–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hultsch D. F., Hertzog C., Small B. J., Dixon R. A. (1999). Use it or lose it: engaged lifestyle as a buffer of cognitive decline in aging? Psychol. Aging 14, 245–263 10.1037/0882-7974.14.2.245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M. (2004). ‘Nurturing the brain’ as an emerging research field involving child neurology. Brain Dev. 26, 429–433 10.1016/j.braindev.2003.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M. H. (2003). Development of human brain functions. Biol. Psychiatry 54, 1312–1316 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00426-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston M. V., Nishimura A., Harum K. H., Pekar J., Blue M. E. (2001). Sculpting the developing brain. Adv. Pediatr. 48, 1–38 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M. K., Reeder J. A., Raye C. L., Mitchell K. J. (2002). Second thoughts versus second looks: an age-related deficit in reflectively refreshing just-activated information. Psychol. Sci. 13, 64–67 10.1111/1467-9280.00411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamijo K., Nishihira Y., Sakai T., Higashiura T., Kim S. R., Tanaka K. (2007). Effects of a 12-week walking program on cognitive function in older adults. Adv. Exerc. Sports Physiol. 13, 31–39 [Google Scholar]

- Kolb B. (2000). Experience and the developing brain. Educ. Can. 39, 24–26 [Google Scholar]

- Kolb B., Forgie M., Gibb R., Gorny G., Rowntree S. (1998). Age, experience and the changing brain. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 22, 143–159 10.1016/s0149-7634(97)00008-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb B., Gibb R., Robinson T. E. (2003). Brain plasticity and behavior. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 12, 1–5 10.1111/1467-8721.01210 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb B., Whishaw I. Q. (1998). Brain plasticity and behavior. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 49, 43–64 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korol D. L., Gold P. E., Scavuzzo C. J. (2013). Use it and boost it with physical and mental activity. Hippocampus 23, 1125–1135 10.1002/hipo.22197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer A. F., Erickson K. I., Colcombe S. J. (2006). Exercise, cognition, and the aging brain. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 101, 1237–1242 10.1152/japplphysiol.00500.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer A. F., Hahn S., McAuley E. (2000). Influence of aerobic fitness on the neurocognitive function of older adults. J. Aging Phys. Act. 8, 379–385 [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Rani A., Tchigranova O., Lee W. H., Foster T. C. (2012). Influence of late-life exposure to environmental enrichment or exercise on hippocampal function and CA1 senescent physiology. Neurobiol. Aging 33, 828.e1–828.e17 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.06.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacourse M. G., Turner J. A., Randolph-Orr E., Schandler S. L., Cohen M. J. (2004). Cerebral and cerebellar sensorimotor plasticity following motor imagery-based mental practice of a sequential movement. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 41, 505–524 10.1682/jrrd.2004.04.0505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurin D., Verreault R., Lindsay J., MacPherson K., Rockwood K. (2001). Physical activity and risk of cognitive impairment and dementia in elderly persons. Arch. Neurol. 58, 498–504 10.1001/archneur.58.3.498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Cao C. M., Yan J. H. (2013). Functional aging impairs the role of feedback in motor learning. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 13, 849–859 10.1111/ggi.12013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz A., Greischar L. L., Rawlings N. B., Ricard M., Davidson R. J. (2004). Long-term meditators self-induce high-amplitude gamma synchrony during mental practice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 101, 16369–16373 10.1073/pnas.0407401101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magill R. A. (2011). Motor Learning and Control: Concepts and Applications. 9th Edn. New York: McGraw-Hill [Google Scholar]

- Mahncke H. W., Connor B. B., Appelman J., Ahsanuddin O. N., Hardy J. L., Wood R. A., et al. (2006). Memory enhancement in healthy older adults using a brain plasticity-based training program: a randomized, controlled study. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 103, 12523–12528 10.1073/pnas.0605194103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maylor E. A. (1998). Changes in event-based prospective memory across adulthood. Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 5, 107–128 10.1076/anec.5.2.107.599 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maylor E. A., Lavie N. (1998). The influence of perceptual load on age differences in selective attention. Psychol. Aging 13, 563–573 10.1037/0882-7974.13.4.563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menec V. H. (2003). The relation between everyday activities and successful aging: a 6-year longitudinal study. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 58, S74–S82 10.1093/geronb/58.2.s74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ming G. L., Song H. (2005). Adult neurogenesis in the mammalian central nervous system. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 28, 223–250 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.051804.101459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neely A. S., Bäckman L. (1993). Long-term maintenance of gains from memory training in older adults: two 3 1/2 year follow-up studies. J. Gerontol. 48, P233–P237 10.1093/geronj/48.5.p233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newell K. M. (1991). Motor skill acquisition. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 42, 213–237 10.1146/annurev.psych.42.1.213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen J. B., Cohen L. G. (2008). The Olympic brain. Does corticospinal plasticity play a role in acquisition of skills required for high-performance sports? J. Physiol. 586, 65–70 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.142661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nojima I., Mima T., Koganemaru S., Thabit M. N., Fukuyama H., Kawamata T. (2012). Human motor plasticity induced by mirror visual feedback. J. Neurosci. 32, 1293–1300 10.1523/jneurosci.5364-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen R. C. (2000). Mild cognitive impairment: transition between aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurologia 15, 93–101 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen R. C., Jack C. R., Xu Y. C., Waring S. C., O’Brien P. C., Smith G. E., et al. (2000). Memory and MRI-based Hippocampal volumes in aging and AD. Neurology 54, 581–587 10.1212/wnl.54.3.581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen R. C., Smith G. E., Waring S. C., Ivnik R. J., Tangalos E. G., Kokmen E. (1999). Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch. Neurol. 56, 303–308 10.1001/archneur.56.3.303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponti G., Peretto P., Bonfanti L. (2008). Genesis of neuronal and glial progenitors in the cerebellar cortex of peripuberal and adult rabbits. PLoS One 3:e2366 10.1371/journal.pone.0002366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prohaska T. R., Peters K. E. (2007). Physical activity and cognitive functioning: translating research to practice with a public health approach. Alzheimers Dement. 3, S58–S64 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quartz S. R., Sejnowski T. J. (1997). The neural basis of cognitive development: a constructivist manifesto. Behav. Brain Sci. 20, 537–596 10.1017/s0140525x97001581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P. (2002). Neurogenesis in adult primate neocortex: an evaluation of the evidence. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 65–71 10.1038/nrn700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasch B., Büchel C., Gais S., Born J. (2007). Odor cues during slow-wave sleep prompt declarative memory consolidation. Science 315, 1426–1429 10.1126/science.1138581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren J., Wu Y. D., Chan J. S. Y., Yan J. H. (2013). Cognitive aging affects motor performance and learning. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 13, 19–27 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2012.00914.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickard T. C., Cai D. J., Rieth C. A., Jones J., Ard M. C. (2008). Sleep does not enhance motor sequence learning. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 34, 834–842 10.1037/0278-7393.34.4.834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson E. M., Pascual-Leone A., Miall R. C. (2004). Current concepts in procedural consolidation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 5, 576–582 10.1038/nrn1426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson E. M., Press D. Z., Pascual-Leone A. (2005). Off-line learning and the primary motor cortex. J. Neurosci. 25, 6372–6378 10.1523/jneurosci.1851-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roller C. A., Cohen H. S., Kimball K. T., Bloomberg J. J. (2002). Effects of normal aging on visuo-motor plasticity. Neurobiol. Aging 23, 117–123 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00264-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronnlund M., Nyberg L., Backman L., Nilsson L. G. (2005). Stability, growth, and decline in adult life span development of declarative memory: cross-sectional and longitudinal data from a population-based study. Psychol. Aging 20, 3–18 10.1037/0882-7974.20.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe J. W., Kahn R. L. (1997). Successful aging. Gerontologist 37, 433–440 10.1093/geront/37.4.433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe J. W., Kahn R. L. (1987). Human aging: usual and successful. Science 237, 143–149 10.1126/science.3299702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudoy J. D., Voss J. L., Westerberg C. E., Paller K. A. (2009). Strengthening individual memories by reactivating them during sleep. Science 326, 1079 10.1126/science.1179013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala-Llonch R., Arenaza-Urquijo E. M., Valls-Pedret C., Vidal-Piñeiro D., Bargalló N., Junqué C., et al. (2012). Dynamic functional reorganizations and relationship with working memory performance in healthy aging. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 6:152 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse T. A. (1996). The processing speed theory of adult age differences in cognition. Psychol. Rev. 103, 403–428 10.1037//0033-295x.103.3.403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse T. A. (2004). What and when of cognitive aging. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 13, 140–144 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00293.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse T. A. (2009). When does age-related cognitive decline begin? Neurobiol. Aging 30, 507–514 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.09.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse T. A., Davis H. P. (2006). Organization of cognitive abilities and neuropsychological variables across the lifespan. Dev. Rev. 26, 31–54 10.1016/j.dr.2005.09.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Samuelson L. K., Smith L. B. (2000). Grounding development in cognitive processes. Child Dev. 71, 98–106 10.1111/1467-8624.00123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanes A. N. (2000). Skill learning: motor cortex rules for learning and memory. Current Biology 10, R495–R497 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00557-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanes J. N. (2003). Neocortical mechanisms in motor learning. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 13, 225–231 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00046-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarmeas N., Levy G., Tang M. X., Manly J., Stern Y. (2001). Influence of leisure activity on the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 57, 2236–2242 10.1212/wnl.57.12.2236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaie K. W. (2004). “Cognitive aging,” in Technology for Adaptive Aging, eds Pew R. W., Van Hemel S. B. (Washington, DC: National Academy Press; ), 41–63 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffman J. M., Luchies C. W., Richards L. G., Zebas C. J. (2002). The effects of age and feedback on isometric knee extensor force control abilities. Clin. Biomech. (Bristol, Avon) 17, 486–493 10.1016/s0268-0033(02)00041-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlaug G. (2001). The brain of musicians: a model for functional and structural plasticity. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 930, 281–299 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05739.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt R. A., Bjork R. A. (1992). New conceptualizations of practice: common principles in three paradigms suggest new concepts for training. Psychol. Sci. 3, 207–217 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1992.tb00029.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt R. A., Lee T. D. (2005). Motor Control and Learning: A Behavioral Emphasis. 4th Edn. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics [Google Scholar]

- Schooler C., Mulatu M. S. (2001). The reciprocal effects of leisure time activities and intellectual functioning in older people: a longitudinal analysis. Psychol. Aging 16, 466–482 10.1037/0882-7974.16.3.466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidler R. D. (2006). Differential effects of age on sequence learning and sensorimotor adaptation. Brain Res. Bull. 70, 337–346 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidler R. D. (2007). Aging affects motor learning but not saving at transfer of learning. Learn. Mem. 14, 17–21 10.1101/lm.394707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel D. J. (2009). Mindful awareness, mindsight and neural integration. Humanistic Psychol. 37, 137–158 10.1080/08873260902892220 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siengsukon C. F., Boyd L. A. (2009). Does sleep promote motor learning? Implications for physical rehabilitation. Phys. Ther. 89, 370–383 10.2522/ptj.20080310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh-Manoux A., Hillsdon M., Brunner E., Marmot M. (2005). Effects of physical activity on cognitive functioning in middle age: evidence from the Whitehall II prospective cohort study. Am. J. Public Health 95, 2252–2258 10.2105/AJPH.2004.055574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C. D., Walton A., Loveland A. D., Umberger G. H., Kryscio R. J., Gash D. M. (2005). Memories that last in old age: motor skill learning and memory preservation. Neurobiol. Aging 26, 883–890 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speisman R. B., Kumar A., Rani A., Foster T. C., Ormerod B. K. (2013a). Daily exercise improves memory, stimulates hippocampal neurogenesis and modulates immune and neuroimmune cytokines in aging rats. Brain Behav. Immun. 28, 25–43 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.09.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speisman R. B., Kumar A., Rani A., Pastoriza J. M., Severance J. E., Foster T. C., et al. (2013b). Environmental enrichment restores neurogenesis and rapid acquisition in aged rats. Neurobiol. Aging 34, 263–274 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.05.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein D. G., Hoffman S. W. (2003). Concepts of CNS plasticity in the context of brain damage and repair. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 18, 317–341 10.1097/00001199-200307000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern Y., Zarahn E., Hilton H. J., Flynn J., DeLaPaz R., Rakitin B. (2003). Exploring the neural basis of cognitive reserve. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 25, 691–701 10.1076/jcen.25.5.691.14573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strawbridge W. J., Wallhagen M. I., Cohen R. D. (2002). Successful aging and well-being: self-rated compared with Rowe and Kahn. Gerontologist 42, 727–733 10.1093/geront/42.6.727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studenski S., Carlson M. C., Fillit H., Greenough W. T., Kramer A., Rebok G. W. (2006). From bedside to bench: does mental and physical activity promote cognitive vitality in late life? Sci. Aging Knowledge Environ. 10, 21–27 10.1126/sageke.2006.10.pe21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studenski S., Perera S., Patel K., Rosano C., Faulkner K., Inzitari M., et al. (2011). Gait speed and survival in older adults. JAMA 305, 50–58 10.1001/jama.2010.1923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson L. R., Lee T. D. (1992). The effects of aging and schedules of knowledge of results on motor learning. J. Gerontol. 47, P406–P411 10.1093/geronj/47.6.p406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taubert M., Draganski B., Anwander A., Muller K., Horstmann A., Villringer A., et al. (2010). Dynamic properties of human brain structure: learning-related changes in cortical areas and associated fiber connections. J. Neurosci. 30, 11670–11677 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2567-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teri L., Gibbons L. E., McCurry S. M., Logsdon R. G., Buchner D. M., Barlow W. E., et al. (2003). Exercise plus behavioral management in patients with Alzheimer disease. JAMA 290, 2015–2022 10.1001/jama.290.15.2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J. R., Solmon M. A., Mitchell B. (1979). Precision knowledge of results and motor performance: relationship to age. Res. Q. 50, 687–698 [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J. R., Yan J. H., Stelmach G. E. (2000). Movement characteristics change as a function of practice in children and adults. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 75, 228–244 10.1006/jecp.1999.2535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomporowski P. D., Hatfield B. D. (2005). Effects of exercise on neurocognitive functions. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Psychol. 3, 363–379 10.1080/1612197x.2005.9671778 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trachtenberg J. T., Chen B. E., Knott G. W., Feng G., Sanes J. R., Welker E., et al. (2002). Long-term in vivo imaging of experience-dependent synaptic plasticity in adult cortex. Nature 420, 788–794 10.1038/nature01273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungerleider L. G., Doyon J., Karni A. (2002). Imaging brain plasticity during motor skill learning. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 78, 553–564 10.1006/nlme.2002.4091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Praag H., Christie B. R., Sejnowski T. J., Gage F. H. (1999b). Running enhances neurogenesis, learning, and long-term potentiation in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 96, 13427–13431 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Praag H., Kempermann G., Gage F. H. (1999a). Running increases cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the adult mouse dentate gyrus. Nat. Neurosci. 2, 266–270 10.1038/6368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Praag H., Shubert T., Zhao C., Gage F. H. (2005). Exercise enhances learning and hippocampal neurogenesis in aged mice. J. Neurosci. 25, 8680–8685 10.1523/jneurosci.1731-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaynman S., Ying Z., Gomez-Pinilla F. (2004). Hippocampal BDNF mediates the efficacy of exercise on synaptic plasticity and cognition. Eur. J. Neurosci. 20, 2580–2590 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03720.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]