Abstract

The purpose of this study was to compare the effects of yoga with an active control (nonaerobic exercise) in individuals with prehypertension and stage 1 hypertension. A randomized clinical trial was performed using two arms: (1) yoga and (2) active control. Primary outcomes were 24‐hour day and night ambulatory systolic and diastolic blood pressures. Within‐group and between‐group analyses were performed using paired t tests and repeated‐measures analysis of variance (time × group), respectively. Eighty‐four participants enrolled, with 68 participants completing the trial. Within‐group analyses found 24‐hour diastolic, night diastolic, and mean arterial pressure all significantly reduced in the yoga group (−3.93, −4.7, −4.23 mm Hg, respectively) but no significant within‐group changes in the active control group. Direct comparisons of the yoga intervention with the control group found a single blood pressure variable (diastolic night) to be significantly different (P=.038). This study has demonstrated that a yoga intervention can lower blood pressure in patients with mild hypertension. Although this study was not adequately powered to show between‐group differences, the size of the yoga‐induced blood pressure reduction appears to justify performing a definitive trial of this intervention to test whether it can provide meaningful therapeutic value for the management of hypertension.

Currently, almost 80 million US adults have high blood pressure (BP),1 with fewer than half of patients with hypertension having their BP controlled.2 Uncontrolled hypertension is thought to be responsible for 62% of cerebrovascular disease and 49% of ischemic heart disease events,3 and was estimated to cost the United States $93.5 billion in health care services, medications, and missed days of work in 2010.4 The cost of drugs, drug interactions, and nonadherence with prescribed drug regimens all contribute to the high rates of uncontrolled hypertension. Alternative, less expensive methods to reduce BP with lower risk of drug interactions, which may convey the benefit of long‐term adherence, are much needed. Yoga is an alternative health care practice that may improve BP control.5, 6 The number of persons who practice yoga continues to rise, with current estimates indicating at least 10.4 million people in the United States (5.1%) practice yoga.7

BP control is one of the most studied outcomes of yoga, with several reviews5, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and one meta‐analysis13 suggesting that yoga is generally effective with effect sizes equivalent to other types of lifestyle interventions. Importantly, however, these reviews also uniformly suggest that current studies of yoga are of poor quality with methodological limitations. In fact, a recent American Heart Association review14 classified the existing evidence for the effects of yoga on BP in the lowest possible category for estimates of certainty of treatment effect (class C). Many of the studies examining the effects of yoga on BP are uncontrolled or use nonhypertensive participants.8 Very few studies have controlled for important confounding factors and only two used ambulatory BP measures, which are known to give a more accurate estimate of treatment effects than office measurements.13 Therefore, the purpose of the current study was to conduct and evaluate a well‐controlled randomized trial comparing the effects of yoga with an active control group on ambulatory BP in individuals with prehypertension and stage 1 hypertension.

Methods

A randomized clinical trial of patients with prehypertension and stage I hypertension was performed using two arms: (1) yoga and (2) active control (nonaerobic exercise). Our hypothesis was that yoga practice would provide significantly better BP reduction than the active control. Prior to recruitment, the study was approved by the Long Island University (LIU's) institutional review board and was registered with Clinicaltrials.gov (NCTO1542359). We estimated that the study would need 90 participants (20% expected dropout rate) to achieve an 85% power to observe a 5 mm Hg change in systolic BP (SBP) between the two groups.15

Participants were recruited through flyers, advertisements, and e‐mail distribution to the local community. The study was described as a “stress reduction” program for hypertension. Inclusion criteria were age between 21 and 70 years; prehypertension or stage I hypertension as determined by a 24‐hour ambulatory BP (ABP) reading, with SBP between 120 and 159 mm Hg or diastolic BP (DBP) between 80 and 99 mm Hg3; medically stable on any current medications; body mass index (BMI) between 18.5 to 40 kg/m2; and English speaking. In addition, participants were required to be available during the expected class periods (both interventions). Exclusion criteria were current use of insulin or oral hypoglycemic agents; previous cardiovascular event (prior myocardial infarction, stroke, or angina pectoris); current or previous cancer diagnosis; congestive heart failure; history of kidney disease; signs or symptoms of significant peripheral vascular disease; significant comorbidities that preclude successful completion of the study (eg, current fractures, Parkinson's disease, vertigo); or current/regular yoga practitioner (participated in more than 3 yoga sessions within the past year).

Participants were told that the study was comparing two potentially beneficial stress‐reducing interventions. Participants in both groups were asked to attend two 55‐minute classes per week for 12 weeks and to perform 3 sessions of home practice for 20 minutes each week as described in detail below. Participants received $100 for completion of all phases of the study including pretest and posttest measures, attendance of ≥75% of the intervention sessions (18 of 24 classes), and completion of homework logs.

Potential participants who met initial criteria (eg, age, medical history, activity levels) via a phone screening and agreed to the requirements/expectations of the study were invited to a BP screening within the Physical Therapy Department at LIU where clinical measures of BP (eg, aneroid sphygmomanometer) were used to determine whether the participant's BP was in the range of the inclusion criteria. If the clinical measures were within the criterion range, the participant was asked to wear an ABP device for 24 hours. After the 24‐hour data were evaluated, if either or both the mean 24‐hour SBP or DBP were within the inclusion range, participants were invited to participate in the study. Measurements were implemented such that no longer than 1 month occurred between the measures and the start of the intervention. Five cohorts of approximately 18 participants each were enrolled across the study period.

Measures

Primary outcomes were SBP and DBP and heart rate (HR). Twenty‐four–hour ABP monitoring was performed at pretest and posttest (“Oscar2,” Suntech Medical, Morrisville, NC). This device has been validated as per internationally recognized standards.16, 17 Twenty‐four–hour ABP values were further categorized as day or night values using each participant's reported awake and sleep times. A minimum of 14 daytime values and 7 nighttime values were required for the data to be considered valid.

Demographic data on race, age, sex, and height and weight were collected at pretest (Table 1). Diet and physical activity were assessed preintervention and postintervention using the Block 100‐Item Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ)18, 19 and the Baecke Questionnaire of Physical Activity,20 respectively. Participants were encouraged to not change their diets, levels of physical activity, or medications during the course of the study unless advised to do so by their physician. At posttest, participants were asked whether they had changed medications during the course of the study. Participants were given access to both Internet‐based and paper methods of self‐report for homework compliance. Efficacy expectations of participants for their assigned intervention were obtained after attendance of the first treatment session using the Credibility Expectancy Questionnaire (CEQ).21, 22 Self‐reported psychosocial measures were obtained at pretest and posttest but will be reported elsewhere.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Randomized Group

| Yoga | Control | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 56.4 (9.78) | 52.45 (12.19) |

| Women, No. (%) | 33 (91.6) | 25 (80.6) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 30.27 (.94) | 29.75 (.93) |

| Physical activity, mean (SD)a | 6.61 (2.51) | 6.97 (2.25) |

| Prehypertensive (SBP 120–139 mm Hg) | 23 (71.9) | 25 (69.4) |

| Hypertensive (SBP >140 mm Hg) | 9 (28.1) | 11 (31.0) |

| Race or ethnicity | ||

| African American | 31 (86.2) | 27 (84.4) |

| Non‐Hispanic white | 1 (2.7) | 1 (3.1) |

| All others | 4 (11.1) | 4 (12.5) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SD, standard deviation. Data are presented as number (percentage) unless otherwise indicated.

Baecke Physical Activity Survey and total of work, leisure, and sport scores.

Randomization

Coin tosses performed by the primary investigator (MH) were used for sequence generation for treatment group assignment. Sequential results (eg, participant 1 = yoga) were placed inside 90 opaque sealed envelopes numbered in advance (eg, 1–90). Once each participant completed pretest measures (with the exception of the survey regarding expectations of treatment efficacy), he/she took the next numbered concealed envelope from within a box located with the measurement laboratory. All outcome assessors remained blinded to assignment of intervention throughout the study. By necessity for an active intervention, participants were not blinded to intervention assignment.

Interventions

The arms of the study were explicitly designed for equivalence of patient effort and time investment, investigator and instructor interaction and attention, social interaction, and expectations of efficacy. Consequently, classes and homework requirements were identical in terms of length, frequency, and duration. All participants were provided with printed text and photos describing the intervention, a video of the respective intervention on DVD, and procedures for recording homework compliance. Classes had similar opportunities before, during, and after class for social interaction. Instructors for both arms completed separate 2‐hour workshop sessions defining goals, approach to participants, administrative duties, and specific structure and physical requirement of each class. Instructors were provided with a standardized teacher's manual and a video (DVD) of the practice. Instructors for both arms were trained to provide positive expectations to participants regarding the potential for the class to lower BP.

In addition, the two interventions of the study were designed to be equivalent in terms of metabolic output. Our previous estimates of the metabolic output of the yoga exercises23 were used to design the level of physical intensity of the exercises used for the active control group. The targeted average intensity across the 55‐minute class was 3 metabolic equivalents (METs) (approximately equal to a brisk pace of walking—a level considered nonaerobic. The validity of this metabolic equivalence across groups during the study was experimentally tested. A subset of participants from each arm (yoga = 9, active control = 8) volunteered to perform his/her respective intervention within the regular class period while wearing a portable indirect calorimeter (K4b,2 Cosmed, USA, Inc, Chicago, IL).24 Estimates of metabolic output (METs) were obtained from the calorimeter through measures of oxygen and carbon dioxide flow through a facemask worn by participants. Measures for both intervention arms were taken during weeks 6 to 8 of the intervention.

Yoga Arm

Yoga is generally described as a practice that incorporates 3 elements: postures, breath control, and meditation.25, 26 The specific yoga intervention incorporated all 3 of these elements and was based on the primary (beginner) series of Ashtanga yoga originally developed by Pattabhi Jois27 and as specifically designed for this study by a long‐term student of Jois: Eddie Stern (Director of Ashtanga Yoga New York, New York, NY). The program was explicitly designed to allow adaptation of poses as needed for individual participants who were expected to be sedentary and older and with somewhat larger body mass. Please see Appendix A for a complete description of the yoga program. All yoga instructors had a minimum of 200 hours of training (Registered Yoga Teacher 200; Yoga Alliance, Arlington, VA).

Active Control Arm

The active control exercise class was nonaerobic and consisted of a warm‐up, exercises (eg, “step‐touch,” squats, upper extremity resistive band work, abdominal strengthening), and stretching/cool down. It was designed by Tracey Rawls Martin (Assistant Professor, Athletic Training and Exercise Sciences Department, LIU). Details of the active control group can be seen in Appendix B. All active control group instructors had at least 2 years of experience in leading fitness classes.

Statistical Analysis

Analytic Strategy

Means and standard deviations for all demographic and primary outcomes were calculated. The primary outcomes of interest were means of systolic and diastolic values (24‐hour, day, night, mean arterial pressure [MAP], and “dipping” status defined as mean day less mean night values), and HR. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and chi‐square analyses were used for retention analysis to determine systematic variation in the factors characterizing (1) persons who completed ≥1 classes but were lost to follow ‐up from (2) persons who participated fully. Separate repeated‐measures ANOVAs (time × group) were performed on physical activity and diet variables to determine whether these factors varied across groups during the trial. Independent t tests were performed on expectation of efficacy to determine whether this factor varied across groups at baseline and on measures of adherence at posttest (number of classes attended and homework performed). Equivalency of the interventions relative to metabolic output was determined by independent t tests of the mean MET values obtained with indirect calorimetry.

Primary Analyses

Paired t tests were used to assess changes within group preintervention to postintervention. Separate repeated‐measures ANOVAs (time × group) were used to determine significant differences relative to the intervention.

Results

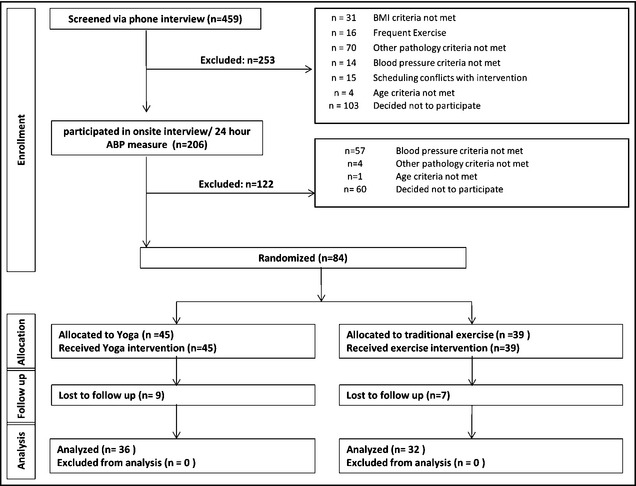

Recruitment occurred from January 2010 to March 2012, with interventions occurring from March 2010 to June 2012. A large number of potential participants were screened (n=459; Figure 1) to achieve 84 participants enrolled. Sixteen (19%) were lost to follow‐up after completing ≥1 classes, leaving 68 participants who completed the trial. Baseline demographic characteristics were similar in the randomized groups (Table 1) and no adverse events were reported. No participants reported changing BP medications during the trial.

Figure 1.

Recruitment flow diagram.

Retention Analysis

Completion did not vary by group χ2 (1)=0.81 (P=1.00) and there were no differences between completers and noncompleters as a function of sex, χ2 (1)=0.32, P=.45, race, χ2 (3)=2.51, P=.47, age, F (1, 82)=0.38, P=.54, BMI, F (1, 82)=0.12, P=.73, expectation scores from the CEQ (all P≥.12), physical activity, F (1, 77)=0.49, P=.49, HR (P=.31) or baseline 24‐hour systolic pressure (P=.20). Completers did, however, have lower DBP at baseline than those lost to follow‐up: F (1, 82)=6.56, P<.05. As might be expected, those who were lost to follow‐up after ≥1 classes attended fewer sessions: F (1, 82)=292.83, P<.01. Mean number of classes attended across groups by completers was 21.91 (±3.02).

Repeated‐measures ANOVAs (time × group) found no significant differences in physical activity (P=.174) or diet variables (all P≥.05) across the groups during the trial. Independent t tests found no significant differences in expectation of efficacy measures from the CEQ obtained at pretest (all P≥.183). Independent t tests found no significant differences between groups in number of classes attended (mean, 21.91 [±3.02]; P=.749) or in minutes of homework performed (mean, 675.45 [±464.39]; P=.506).

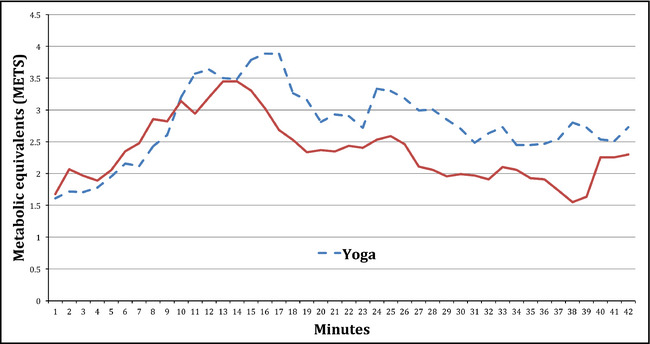

Independent t tests comparing the metabolic requirements of the two arms found that the yoga arm required significantly more energy to complete (2.79, ±0.59 METS) than the active control group (2.36, ±0.49 METS) (P<.001). Figure 2 displays the mean metabolic requirements of both arms of the trial across a single session.

Figure 2.

Metabolic requirements for each intervention.

Primary Analyses

Within Group

Results of paired t tests assessing within‐group intervention to postintervention changes are described in Table 2. Twenty‐four–hour diastolic, night diastolic, and MAP were all significantly reduced in the yoga group (−3.93, −4.7, −4.23 mm Hg, respectively). Similarly, trends (P<.10) for the yoga group to reduce BP were seen in 24‐hour SBP, day DBP, and night SBP. However, unlike the yoga group, the active control group did not demonstrate any significant within group changes or trends.

Table 2.

Results of Within‐Group and Between‐Group Analysis

| Time 1 | Time 2 | Change Value Time 1–Time 2 | Within‐Group P Value | Between‐Group P Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| Systolic 24 | Control | 133.80 | 9.86 | 133.36 | 18.29 | −.44 | 15.00 | .868 | .224 |

| Yoga | 135.53 | 9.79 | 130.68 | 14.99 | −4.84 | 14.54 | .053 | ||

| Diastolic 24 | Control | 80.17 | 7.49 | 79.76 | 11.11 | −.41 | 8.19 | .778 | .0814 |

| Yoga | 80.82 | 7.33 | 76.89 | 8.61 | −3.93 | 8.14 | .006a | ||

| HR 24 | Control | 77.58 | 10.63 | 75.75 | 9.72 | 1.83 | 8.98 | .258 | .999 |

| Yoga | 72.34 | 8.25 | 70.5 | 7.04 | 1.83 | 6.79 | .114 | ||

| Systolic (day) | Control | 138.63 | 10.39 | 138.68 | 17.87 | .052 | 16.18 | .986 | .326 |

| Yoga | 139.64 | 10.72 | 135.81 | 16.55 | −3.83 | 16.13 | .163 | ||

| Diastolic (day) | Control | 84.62 | 7.52 | 84.42 | 11.48 | −.19 | 9.90 | .913 | .256 |

| Yoga | 84.31 | 8.63 | 81.38 | 10.19 | −2.93 | 9.81 | .081 | ||

| HR (day) | Control | 80.39 | 11.10 | 79.08 | 10.38 | 1.3 | 9.75 | .454 | .905 |

| Yoga | 75.18 | 9.45 | 73.61 | 7.59 | 1.56 | 8.01 | .248 | ||

| Systolic (night) | Control | 122.61 | 12.72 | 121.76 | 19.97 | −.85 | 15.80 | .764 | .262 |

| Yoga | 125.14 | 12.06 | 119.96 | 15.05 | −5.17 | 15.70 | .056 | ||

| Diastolic (night) | Control | 69.95 | 10.55 | 69.59 | 12.23 | −.36 | 8.26 | .807 | .038a |

| Yoga | 72.07 | 7.97 | 67.36 | 7.97 | −4.70 | 8.60 | .002a | ||

| HR (night) | Control | 70.35 | 10.96 | 68.71 | 9.69 | 1.63 | 8.88 | .306 | .880 |

| Yoga | 65.59 | 8.29 | 63.65 | 7.07 | 1.93 | 7.63 | .137 | ||

| MAP 24‐h | Control | 98.13 | 7.71 | 97.62 | 13.17 | .51 | 10.23 | .781 | .134 |

| Yoga | 99.05 | 7.36 | 84.82 | 9.89 | 4.23 | 10.01 | .016a | ||

| Systolic (dip) | Control | −13.78 | 10.18 | −14.77 | 8.35 | −.98 | 11.09 | .620 | .890 |

| Yoga | −12.29 | 10.84 | −13.66 | 9.72 | −1.37 | 12.08 | .500 | ||

| Diastolic (dip) | Control | −22.80 | 16.46 | −22.86 | 14.66 | .06 | 15.5 | .981 | .370 |

| Yoga | −18.01 | 15.1 | −21.43 | 13.00 | 3.42 | 15.1 | .183 | ||

Abbreviations: between‐group, results of repeated‐measures analysis of variance (time × group); M, mean; MAP, mean arterial pressure, diastolic + (0.33333 × [systolic – diastolic]); SD, standard deviation; within‐group, results of paired t tests of within‐group change scores Time 1 vs Time 2. Values are expressed as means (standard deviations).

P<.05.

Between Group

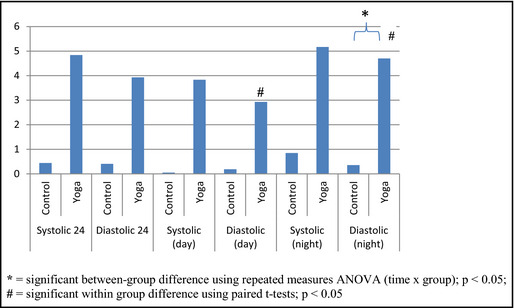

Repeated‐measures ANOVAs (time × group) demonstrated a significant difference between groups in preintervention to postintervention changes in diastolic nighttime pressures (P=.038) and a trend in diastolic 24‐hour pressures (P=.081). There were no significant differences or trends in any other variables (Table 2). See Figure 3 for a display of BP change values from pretest to posttest.

Figure 3.

Change value (decrease in mm Hg) from pretest to posttest.

Discussion

This study showed that yoga decreases BP in patients with very mild hypertension while the active control intervention (nonaerobic exercise) did not reduce BP. However, in direct comparisons of the yoga intervention with the control group, only a single BP change variable (diastolic night) was found to be significantly different. Although recruitment goals for this study were essentially met (n=84 vs goal of n=90), and effect size and dropout rates were accurately estimated, the expected variability in BP measurements was underestimated. Standard deviations are displayed in Table 2 and range from approximately 9 mm Hg to 16 mm Hg. These values are similar to some previous studies using ambulatory BP monitoring28, 29 but are greater than in others.30 Future research will require larger sample sizes to achieve sufficient power for comparisons with control groups.

The current study found that yoga decreased 24‐hour mean SBP and DBP by approximately 5 mm Hg and 4 mm Hg, respectively. These BP reductions are consistent with the values found in a recent meta‐analysis of controlled studies examining the effect of yoga on individuals with hypertension (systolic 4 mm Hg and diastolic 4 mm Hg).13 The differences in BP reported in the present study are comparable to those reported for other nonpharmacologic strategies such as the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet, physical exercise, and salt reduction. Apart from their value in all patients with hypertension, these interventions have been recommended for people with prehypertension by the national hypertension guidelines,3 and it may now be appropriate to consider yoga programs, which have no known adverse effects for participants, as an additional strategy to be considered in delaying or even preventing the onset of hypertension in patients at risk for this condition.

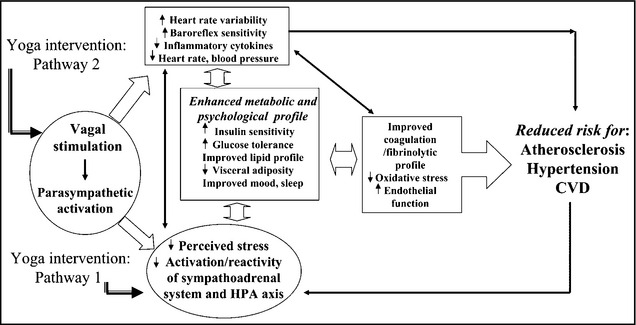

The mechanisms by which yoga may influence BP are not well understood. Figure 4 presents a previously suggested model of hypothesized pathways.6 Yoga may reduce feelings of stress and increase a sense of well‐being, reducing activation of the sympathetic nervous system and positively altering neuroendocrine status and inflammatory responses (see pathway 1 in Figure 4). The physical practices of yoga may directly stimulate the vagus nerve increasing parasympathetic output (see pathway 2 in Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Hypothesized pathways by which yoga may influence hypertension and cardiovascular risk profiles.6

To our knowledge, there are only 3 controlled trials that adequately reported BP data and have examined the effects of yoga on individuals with hypertension using exercise comparison groups.13 In all three studies31, 32, 33 there were no significant effects of yoga when compared with exercise. In the current study, the use of a nonaerobic exercise arm was designed primarily as an active control with no expectation of improvement in BP outcome; this was confirmed with the observation of no significant within‐group changes or trends. Although the intent of the design was to have the active control match the yoga arm in metabolic output, the mean METs of the yoga arm required more energy than that of the active control group. The mean difference between treatment arms was small and unlikely to be clinically meaningful, but it did achieve statistical significance. Future studies attempting to balance treatment arms relative to metabolic output would benefit from additional efforts to develop an active control arm with practices more precisely aligned with the energy requirements of the yoga practice under study.

Although this study is one of many that have examined the effects of yoga on BP, it is among the first to use rigorous methods in a randomized trial on individuals with prehypertension or stage 1 hypertension. There were no significant differences between groups on measures of physical activity, food, expectation of efficacy, or adherence minimizing these potential sources of bias. Additionally, control of potential sources of bias related to selection, detection, attrition, and reporting,34 the successful balancing of treatment arms relative to duration, frequency, and social interaction, and the use of state‐of‐the‐art ABP monitoring give confidence that this type of research can be conducted in compliance with highly credible clinical trial methodology.

Given the variability found in this study, future research will require larger sample sizes to achieve sufficient power for comparisons with control groups. Future research might also benefit from techniques to predict which patients are most likely to positively engage in yoga, thus making more targeted interventions possible.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that a yoga intervention in patients with mild hypertension can significantly reduce BP. Although this study was not adequately powered to test this effect against a control group, the size of the yoga‐induced BP reduction we observed appears to justify performing a definitive trial of this intervention to test whether it can provide meaningful therapeutic value for the management of prehypertension and stage 1 hypertension.

Conflict of Interest

There are no competing financial interests in relation to the current work.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences: 1SC3GM088049‐01A1.

Appendix A. Description of the Yoga Program

The yoga program is based on Ashtanga (Primary Series). Conscious use of the breath, frequently cued by the instructor, occurs through most of the practices. The intensity of the practice varies based on the participant's capacity through the 12‐week program. The expectation is that advances in capacity will be reflected in longer holds of postures sustained with more breath cycles and more advanced postures (eg, Warrior pose).

Below represents the total available practices for this program and the order to be followed for each class (eg, meditation, postures, breathing, and relaxation). However, not all physical postures described below will occur in each class. Instructors will make decisions regarding the appropriate level of practices based on the capacity of the students present. The warm‐up exercises will typically occur during the first month as students begin to understand the relationship of movement with breath and to have increased mobility, and may then be discarded if not needed. It is expected that during the second month, Sun Salutation B will be implemented and that during the third month, Warrior poses will be implemented. Instructors will encourage modification of postures as needed. For example, chairs and the wall will be used for support for those who cannot achieve the standard position or who have poor balance.

Class structure

-

1

Meditation 5 to 7 minutes: Upon entering, students will be asked to assume a seated position on the floor or a chair and close the eyes and begin meditating. Class begins with a led meditation focusing on the body and breath in month 1, the nervous system in month 2, and the mind in month 3.

-

2

Physical postures (Asana) – 35 minutes

-

a.

Warm‐up (3 × each exercise):

Lift arms overhead while you breathe in. As you breathe out, lower the arms.

Bend forward as you exhale, lift up as you inhale, bend forward as you exhale, then lift all the way to standing as you inhale.

On all fours, or leaning against the chair or wall, inhale as you lift your head and arch your spine, exhale as you lower your head and flex your spine. You may do this on your elbows as well.

Lie on your stomach. Place your hands on the floor under your shoulders. Gently lift your upper back and look to the right as you inhale. Slowly look to the left and lower down as you exhale.

-

b.

Sun Salutation A (5×)

-

c.

Sun Salutation B (3×) Likely to begin 2nd month of training

-

d.

Warrior 1 and 2 (3×) Likely to begin 3rd month of training

-

e.

Hands to feet pose (2–8 breaths)

-

f.

Triangle pose right and left (2–8 breaths each)

-

g.

Extended side angle right and left (2–8 breaths each)

-

h.

Spread foot pose (4 types: hands on floor/hands behind back/elbows on floor/hands on ankles) (2–8 breaths each type)

-

i.

Side Stretch pose (2–8 breaths)

-

j.

Forward Bend moving into Table Top (2–8 breaths each)

-

k.

Janu Sirshasana right and left (2–8 breaths each)

-

l.

Butterfly pose (2–8 breaths)

-

m.

Shalabasana (2–8 breaths)

-

a.

-

3

Regulated Breathing – 10 Minutes

Seated cross‐legged, hands clasped behind back, head leaning forward, flexed spine (10 breaths)

Seated cross‐legged, leaning backward with hands on floor, arching spine, looking up and back with eyes (10 breaths)

Seated cross‐legged, arms straight with forearms resting on knees, palms upward, tips of index and thumbs touching, perform Victorious Breath with Abdominal Lock (10 breaths)

Seated cross‐legged, use the thumb and little finger to hold the side of the nose and alternate: Alternate Nostril Breathing (10 breaths each side)

-

4

Relaxation – 5 minutes

Shavasana, lying on the back, palms upward to ceiling.

Appendix B. Description of Exercise Program

The exercise program consisted of a group of exercises commonly used within gyms and sports centers. The goal of the program was to create a series of exercises that could be performed by sedentary older adults and that could be varied in intensity through changing the speed and number of repetitions. Instructors were encouraged to modify exercises as needed for those with less flexibility, strength, or endurance. Breath control was explicitly not discussed. If questioned, participants were told to never stop breathing and to breathe in whatever way they felt most comfortable.

Class structure:

Warm‐up: 5 to 7 minutes: In standing: Arm circles, shoulder circles, head/neck rotation and flexion/extension, trunk flexion/extension via rolling down and up, squat position hands on knees rotate trunk right and left, lunge position stretch calves, lean forward with on leg forward, and stretch hamstrings.

Exercises: 30 to 35 minutes: All exercises performed right and left: In standing: step touch side to side hands on hips, same with “pushing arms” in rhythm, same with “swinging arms” in rhythm, rotate trunk right and left with “pushing arms” during step touch side‐to‐side. Repeat above with alterations of entire body relative to room—moving on diagonals, moving to face the rear of the room. Squats with arms forward. Remain in squat position and move one leg backwards to touch toe on floor while extending arms fully backwards. Continue alternating back‐stepping motion while arms abduct overhead in rhythm. Participants find a partner and face each other. Using a resistive band stretched between them, squat while pulling against each other with the resistive band. Face each other more closely and perform external and internal rotation shoulder exercises using the resistive band. Move to hands and knees and do Cat and Cow (spinal flexion and extension), modified push‐ups (on knees as needed). Move to back and do abdominal curl‐ups with hands behind head and then curl‐ups with rotations. Move to side lying and do lower extremity hip abduction and adduction. Move to supine and perform pelvic lifts. Maintain pelvic lift and remove one foot from floor keeping pelvis stable.

Stretches: 13 to 20 minutes: In supine: double knee to chest, hold with arms. Remain in supine. Hamstring stretch, one foot on floor, other hip flexed to 90 degrees and straighten knee. Trunk stretch in supine—bend knees with feet on floor, allow knees to fall to the side achieving trunk rotation. Allow knees to open up—bilateral horizontal abduction (butterfly position) to stretch inner thighs. In sitting with soles of feet touching each other and with knees flexed approximately 90 degrees, lean forward—stretching posterior hips and back. Straighten one leg fully, maintain other leg in Butterfly position and lean forward over straight leg. In sitting butterfly position, rotate trunk maximally with hands on floor to assist. Straighten one leg out to the side and lean over for side of trunk stretch with arm overhead reaching to foot. Place both legs out straight ahead in sitting and lean over both legs. Open up legs to as large a “V” shape as possible. Lean forward to stretch hamstrings, adductors, and back.

J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014;16:54–62. ©2013 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

References

- 1. Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd‐Jones DM, et al. On behalf of the American Heart Association statistics committee and stroke statistics subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics – 2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:188–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gillespie C, Kuklina EV, Briss PA, et al. Vital signs: prevalence, treatment, and control of hypertension, United States, 1999–2002 and 2005–2008. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:103–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Website . High blood pressure facts. 2012. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/bloodpressure/facts.htm. Accessed August 13, 2012.

- 5. Okonta NR. Does yoga therapy reduce blood pressure in patients with hypertension?: an integrative review. Holist Nurs Pract. 2012;26:137–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Innes KE, Vincent HK. The influence of yoga‐based programs on risk profiles in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2007;4:469–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Birdee GS, Legedza AT, Saper RB, et al. Characteristics of yoga users: results of a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1653–1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Innes KE, Bourguignon C, Taylor AG. Risk indices associated with the insulin resistance syndrome, cardiovascular disease, and possible protection with yoga: a systematic review. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18:491–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hutchinson SC, Ernst E. Yoga therapy for coronary heart disease: a systematic review. Focus Altern Complement Ther. 2003;8:144. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Raub JA. Psychophysiologic effects of hatha yoga on musculoskeletal and cardiopulmonary function: a literature review. J Altern Complement Med. 2002;8:797–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jayasinghe SR. Yoga in cardiac health (a review). EurJ Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2004;11:369–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bussing A, Michalsen A, Khalsa SB, et al. Effects of yoga on mental and physical health: a short summary of reviews. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:165410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hagins M, States R, Selfe T, Innes K. Effectiveness of yoga for hypertension: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:649836. doi: 10.1155/2013/649836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brook RD, Appel LJ, Rubenfire M, et al. American Heart Association Professional Education Committee of the Council for High Blood Pressure Research CoC, Stroke Nursing CoE, Prevention, Council on Nutrition PA: beyond medications and diet: alternative approaches to lowering blood pressure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2013;61:1360–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. van Montfrans GA, Karemaker JM, Wieling W, Dunning AJ. Relaxation therapy and continuous ambulatory blood pressure in mild hypertension: a controlled study. BMJ. 1990;300:1368–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jones SC, Bilous M, Winship S, et al. Validation of the Oscar 2 oscillometric 24‐hour ambulatory blood pressure monitor according to the international protocol for the validation of blood pressure measuring devices. Blood Press Monit. 2004;9:219–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Goodwin J, Bilous M, Winship S, et al. Validation of the Oscar 2 oscillometric 24‐h ambulatory blood pressure monitor according to the British Hypertension Society protocol. Blood Press Monit. 2007;12:113–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Block G, Woods M, Potosky A, Clifford C. Validation of a self‐administered diet history questionnaire using multiple diet records. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43:1327–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Block G, Thompson FE, Hartman AM, et al. Comparison of two dietary questionnaires validated against multiple dietary records collected during a 1‐year period. J Am Diet Assoc. 1992;92:686–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Baecke JA, Burema J, Frijters JE. A short questionnaire for the measurement of habitual physical activity in epidemiological studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 1982;36:936–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Deviliya GJ, Borkovecb TD. Psychometric properties of the credibility/expectancy questionnaire. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2000;31:73–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Smeets RJ, Beelen S, Goossens ME, et al. Treatment expectancy and credibility are associated with the outcome of both physical and cognitive‐behavioral treatment in chronic low back pain. Clin J Pain. 2008;24:305–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hagins M, Moore W, Rundle A. Does practicing hatha yoga satisfy recommendations for intensity of physical activity which improves and maintains health and cardiovascular fitness? BMC Complement Altern Med. 2007;7:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Maiolo C, Melchiorri G, Iacopino L, et al. Physical activity energy expenditure measured using a portable telemetric device in comparison with a mass spectrometer. Br J Sports Med. 2003;37:445–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Baldwin MC. Psychological and Physiological Influences of Hatha Yoga Training on Healthy, Exercising Adults (Yoga, Stress, Wellness)[Dissertation]. Boston, MA: Boston University; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cowen VS, Adams TBP. Physical and perceptual benefits of yoga asana practice: results of a pilot study. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2005;9:211–219. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jois P. Yoga Mala. New York: North Point Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wittke E, Fuchs SC, Fuchs FD, et al. Association between different measurements of blood pressure variability by ABP monitoring and ankle‐brachial index. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2010;10:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Imai Y, Nagai K, Sakuma M, et al. Ambulatory blood pressure of adults in Ohasama, Japan. Hypertension. 1993;22:900–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vollmer WM, Appel LJ, Svetkey LP, et al. Comparing office‐based and ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in clinical trials. J Hum Hypertens. 2005;19:77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Niranjan M, Bhagyalakshmi K, Ganaraja B, et al. Effects of yoga and supervised integrated exercise on heart rate variability and blood pressure in hypertensive patients. JCCM. 2009;4:139–143. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Subramanian H, Soudarssanane MB, Jayalakshmy R, et al. Non‐pharmacological interventions in hypertension: a community‐based cross‐over randomized controlled trial. Indian J Community Med. 2011;36:191–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Saptharishi LG, Soudarssanane MB, Thiruselvakumar D, et al. Community‐based randomized controlled trial of non‐pharmacological interventions in prevention and control of hypertension among young adults. Indian J Community Med. 2009;34:329–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, et al. Cochrane Bias Methods Group, Cochrane Statistical Methods Group. The Cochrane collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]