Abstract

Midgut malrotation commonly presents in the neonatal period, and rarely manifests its symptoms in adulthood with an estimated incidence of 0.2–0.5%. Nevertheless, the symptoms are non-specific with no strong pointers towards the clinical diagnosis. Consequently, the diagnosis is usually disclosed with imaging or surgery. We report a case of small bowel obstruction secondary to a congenital peritoneal band with underlying midgut malrotation in a 48-year-old man.

Background

Midgut malrotation commonly presents in the neonatal period,1 and rarely presents in adulthood.

The symptoms are non-specific with no strong pointers towards the clinical diagnosis. Hence, cross-sectional imaging is the most useful non-invasive investigation to diagnose midgut malrotation and its complications. We report an adult case of small bowel obstruction secondary to a congenital peritoneal band with underlying midgut malrotation.

Case presentation

A 48-year-old man presented with sudden onset of severe abdominal pain associated with nausea and vomiting. He denied any history of altered bowel habit, loss of weight, loss of appetite or fever. He had no history of abdominal surgery. Further questioning revealed a history of intermittent, non-specific abdominal pain in every 3–4 months interval for the past 2 years. The pain was usually relieved by sleeping on the abdomen in the prone position. However, this measure was not effective for the current episode of pain.

On clinical examination, he was pink and afebrile. The abdomen was distended but soft. There was no palpable mass. The bowel sounds were normal. Digital rectal examination showed no evidence of maelenic stool or rectal mass.

Investigations

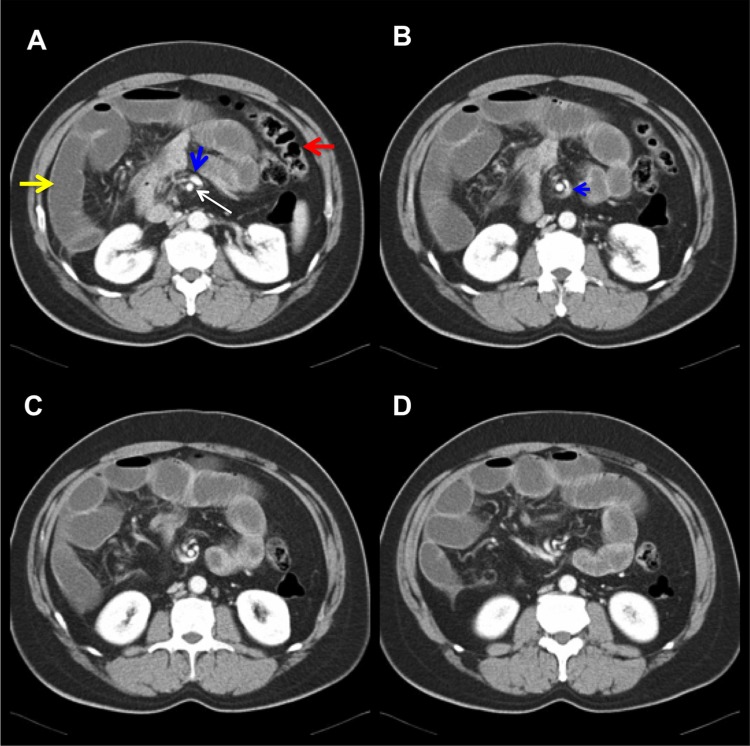

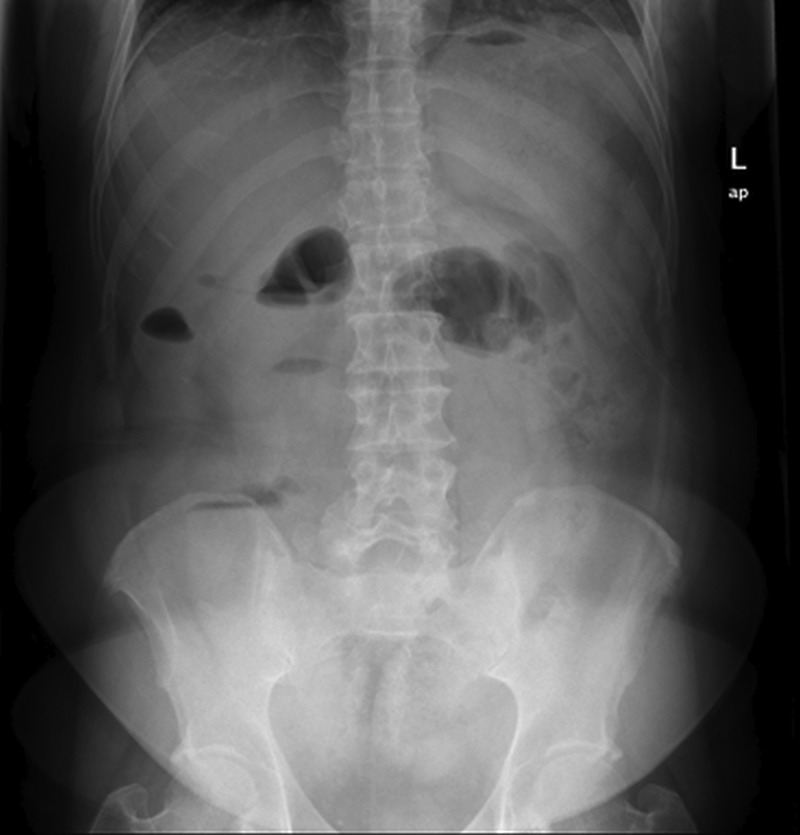

An abdominal X-ray (figure 1) was performed which showed paucity of bowel gas. No dilated loops of bowel were seen. In view of the acute-on-chronic clinical presentation in a middle-aged patient, a working diagnosis of intestinal obstruction secondary to bowel malignancy was made. A contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen was performed for further evaluation.

Figure 1.

Abdominal X-ray showing paucity of bowel gas with short segment of non-specific gas-filled small bowel.

The CT of the abdomen (figure 2) showed grossly dilated small bowel with air fluid levels. All the loops of small bowel were located on the right side of the abdomen, whereas the collapsed large bowel was located on the left side. At the root of the mesentery, the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) was located to the left of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) while rotating around the SMA. However, there was no loop of bowel seen twisting around the mesentery. The normal bowel wall enhancement was preserved and the mesenteric veins were not engorged. There was no bowel related mass or pneumoperitoneum.

Figure 2.

CT of the abdomen showing dilated loops of small bowel which indicate small bowel obstruction. The dilated loops of small bowel (yellow arrow) are located on the right side of the abdomen while the collapsed large bowel (red arrow) is located on the left side. The superior mesenteric vein (blue arrow) is rotated around the superior mesenteric artery (white arrow). The mesenteric veins are not engorged.

Differential diagnosis

A diagnosis of midgut malrotation with small bowel obstruction was made. However, the possibility of midgut volvulus could not be excluded as the exact cause of the intestinal obstruction was not detectable. The patient was managed by emergency laparotomy to relieve the small bowel obstruction.

Treatment

Intraoperatively, a peritoneal band connecting the ileum and the distal appendix was discovered about 100 cm from the duodenojejunal junction. The peritoneal band had resulted in a tight external compression to the terminal ileum. The caecum was located at the left iliac fossa. The entire small bowel proximal to the caecum was dilated whereas the large bowel was collapsed. The small bowel wall was oedematous. However, no gangrenous segment was seen. There was also no evidence of midgut volvulus. Surgical findings confirmed the diagnosis of small bowel obstruction secondary to a congenital peritoneal band with underlying midgut malrotation. The peritoneal band was divided and ligated. The caecum was returned to the right iliac fossa after the appendicectomy was performed.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient was discharged after 4 days once he recovered uneventfully. There was no recurrence of symptoms on subsequent follow-up.

Discussion

Midgut malrotation commonly presents in the neonatal period. Approximately 85% of cases present in the first 2 weeks of life.1 Rarely, midgut malrotation manifests itself in adulthood with the estimated incidence of 0.2–0.5%.2 The incidental finding of midgut malrotation in an asymptomatic adult on cross-sectional imaging is common. Nevertheless, the symptoms are non-specific with no strong pointers towards the clinical diagnosis. The diagnosis is usually disclosed with imaging or surgery. Adult midgut malrotation may present either acutely as intestinal obstruction due to volvulus or congenital peritoneal bands or chronically as vague abdominal pain.3 In the present case, the patient experienced acute and chronic intermittent symptoms. The chronic intermittent symptoms improved with the patient lying in the prone position. This remedial action may have altered the configuration of the band and alleviated the obstruction.

During the stages of intrauterine development, the gut lies outside the abdominal cavity for up to 10 weeks of gestation. Subsequently, the gut returns into the abdominal cavity with counterclockwise rotation of 270°.3 Midgut malrotation occurs when the degree of bowel rotation is less than normally expected.4 This results in a broad spectrum of rotational and fixation anomalies.4 It causes malposition of the duodenojejunal junction to the right of midline. It is also associated with narrow mesenteric attachment of the small bowel which predisposes to twisting or volvulus of the bowel.4 The band that fixes the duodenum and caecum to the posterior abdominal wall continue to form, resulting in the peritoneal band which is known as Ladd's band.5 Ladd's band potentially compresses the second or third part of the duodenum and results in small bowel obstruction.5

Other congenital bands are rare and the origin is not well understood. It may be related to mesenteric developmental anomaly. These congenital bands may cause obstruction at mid-jejunum, ileum and colon.6 The incidence of a congenital peritoneal band in an adult is extremely rare. As for the present case, the peritoneal band had connected the ileum to the distal appendix. However, it was only revealed intraoperatively and was not visualised on CT scan.

By definition, midgut volvulus is the twisting of small bowel about its mesentery. On cross-sectional imaging, one should be able to see the affected segment of bowel twisted about the mesentery. This imaging feature is known as the whirlpool sign.7

In the present case, the swirling of SMV around the SMA and the inversed position of the SMV and SMA indicate midgut malrotation but not midgut volvulus. However, the presence of midgut volvulus must be carefully sought due to its catastrophic effects of vascular compromise and bowel infarction. Other associated findings in bowel volvulus are as follows: truncated SMA on ultrasound, mesenteric vein congestion, bowel wall oedema and peritoneal free fluid. A conventional supine abdominal X-ray is commonly employed to rule out intestinal obstruction. However, the radiographic sign of small bowel obstruction would be obscured when the dilated bowel is distended with fluid. A CT scan is the most useful imaging modality to diagnose midgut volvulus and its associated complications.

In conclusion, the adult presentation of midgut malrotation with small bowel obstruction secondary to congenital peritoneal band poses a diagnostic challenge because of its rare occurrence and non-specific clinical presentation. Hence, the possibility of this condition should be borne in mind. The current available imaging facilities enable accurate and early diagnosis. Surgery remains the mainstay of treatment.

Learning points.

Midgut malrotation rarely presents in adulthood. They can present either acutely with intestinal obstruction secondary to volvulus or peritoneal bands, or chronically with vague abdominal pain.

Cross-sectional imaging is the most useful non-invasive diagnostic tool to diagnose midgut malrotation and its complications.

Peritoneal bands should be considered as the cause of small bowel obstruction in midgut malrotation when there is no volvulus or other identifiable causes on cross-sectional imaging.

Footnotes

Contributors: YLL was involved in drafting the manuscript. SFL and CSN revised the article for important intellectual content. RS edited the manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.McIntosh R, Donovan EJ. Disturbances of rotation of the intestinal tract. Am J Dis Child 1939;57:116–66 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang CA, Welch CE. Anomalies of intestinal rotation in adolescents and adults. Surgery 1963;8:839–55 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gamblin TC, Stephens RE, Jr, Johnson RK, et al. Adult malrotation: a case report and review of the literature. Curr Surg 2003;60:517–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pickhardt PJ, Bhalla S. Intestinal malrotation in adolescents and adults: spectrum of clinical and imaging features. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2002;179:1429–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Long FR, Kramer SS, Markowitz RI, et al. Radiographic patterns of intestinal malrotation in children. Radiographics 1996;16:547–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akgur FM, Tanyel FC, Buvukpamukcu N, et al. Anomalous congenital bands causing intestinal obstruction in children. J Pediatr Surg 1992;27:471–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ha HK, Rha SE, Kim JH, et al. CT diagnosis of strangulation in patients with small-bowel obstruction: current status and future direction. Emerg Radiol 2000;7:47–55 [Google Scholar]