Abstract

Classic non-homologous end-joining (C-NHEJ) is required for the repair of radiation-induced DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) in mammalian cells and plays a critical role in lymphoid V(D)J recombination. A core C-NHEJ component is the DNA ligase IV co-factor, Cernunnos/XLF (hereafter XLF). In patients, mutations in XLF cause predicted increases in radiosensitivity and deficits in immune function, but also cause other less well-understood pathologies including neural disorders. To characterize XLF function(s) in a defined genetic system, we used a recombinant adeno-associated virus-mediated gene targeting strategy to inactivate both copies of the XLF locus in the human HCT116 cell line. Analyses of XLF-null cells (which were viable) showed that they were highly sensitive to ionizing radiation and a radiomimetic DNA damaging agent, etoposide. XLF-null cells had profound DNA DSB repair defects as measured by in vivo plasmid end-joining assays and were also dramatically impaired in their ability to form either V(D)J coding or signal joints on extrachromosomal substrates. Thus, our somatic XLF-null cell line recapitulates many of the phenotypes expected from XLF patient cell lines. Subsequent structure:function experiments utilizing the expression of wild-type and mutant XLF cDNAs demonstrated that all of the phenotypes of an XLF deficiency could be rescued by the overexpression of a wild-type XLF cDNA. Unexpectedly, mutant forms of XLF bearing point mutations at amino acid positions L115 and L179, also completely complemented the null phenotype suggesting, in contrast to predictions to the contrary, that these mutations do not abrogate XLF function. Finally, we demonstrate that the absence of XLF causes a small, but significant, increase in homologous recombination, implicating XLF in DSB pathway choice regulation. We conclude that human XLF is a non-essential, but critical, C-NHEJ-repair factor.

1. Introduction

DNA double-strand-breaks (DSBs) are the most cytotoxic form of DNA damage. They can occur following exposure of cells to exogenous agents such as ionizing radiation (IR), topoisomerase inhibitors and radiomimetic drugs (e.g. bleomycin and etoposide), and are generated by endogenous cellular processes such as V(D)J {variable(diversity)joining} recombination, stalled replication fork collapse and reactions that produce reactive oxygen species [1, 2].

In mammalian cells, there are two major pathways for the repair of IR-induced DSBs: homologous recombination (HR) and non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) [3, 4]. HR is a generally accurate (“error-free”) form of repair, which requires an undamaged homolog or, preferentially, a sister chromatid to act as a DNA template and thus functions most efficiently only after DNA replication. In contrast, the major sub-pathway of NHEJ, classic NHEJ (C-NHEJ), is active throughout the cell cycle [5, 6] and is considered the major pathway for the repair of IR-induced DSBs in human cells [7, 8]. In its most elementary form, C-NHEJ facilitates the straightforward ligation of the broken DNA ends of a DSB. However, since the DNA ends formed by IR exposure are complex and frequently contain non-ligatable end groups, the successful repair of such DNA lesions by C-NHEJ minimally requires the processing of the ends prior to ligation [2, 8]. This requirement often leads to the loss or addition of nucleotides from either side of the DSB, often making C-NHEJ “error-prone”. In addition, a back-up pathway for C-NHEJ {alternative NHEJ or A-NHEJ}, which has features reminiscent of both HR and C-NHEJ, has been described [9, 10]. However, whether A-NHEJ provides important functions in normal cells — or only when C-NHEJ is deficient — is not yet clear.

There are seven well-characterized C-NHEJ factors: the Ku70/Ku86 heterodimer (Ku), the DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs), Artemis, X-ray-cross-complementation gene 4 (XRCC4), DNA ligase IV (LIGIV), and Cernunnos/XRCC4-like factor (hereafter XLF) [2, 7, 8]. Processing enzymes, such as DNA polymerases μ and λ, and polynucleotide kinase also likely play a role in C-NHEJ, at least at a subset of DNA ends [11, 12], but are not generally considered core C-NHEJ factors. The mechanism of C-NHEJ-mediated DSB repair likely requires that the Ku heterodimer binds to the DSB ends, where among other functions, it recruits downstream C-NHEJ factors [13, 14]. DNA-bound Ku forms a complex with and activates the DNA-dependent catalytic subunit, DNA-PKcs [15], which subsequently activates the endonuclease activity of Artemis [16, 17]. The Artemis endonuclease likely processes at least a subset of DNA ends to prepare them for end joining [18]. Finally LIGIV, in association with XRCC4 and XLF, performs the end ligation reaction [19-21]. This linear, stepwise model for C-NHEJ may be oversimplified as there is, for example, evidence that LIGIV, XRCC4 and XLF may perform roles both upstream and downstream in the repair process [22-24].

In mammals, the generation of the immune system requires a somatic site-specific rearrangement process termed V(D)J recombination [2, 25, 26]. In lymphoid progenitor cells, clusters of isolated variable (V), diversity (D) and joining (J) elements reside along the chromosome. During B- and T-cell development, individual V, D, and J elements are extracted from these clusters and enzymatically assembled to generate a functional gene that will ultimately encode an immunoglobulin or T-cell receptor protein, respectively. V(D)J recombination is initiated by the recombination activating genes 1 and 2 (RAG1 and RAG2, respectively), which introduce DSBs between participating V, D or J coding sequences and flanking recombination signal (RS) sequences. RAG-mediated cleavage produces two blunt 5’-phosphorylated RS ends and two covalently sealed (hairpin) coding ends. Subsequently, C-NHEJ repairs the RS ends and coding ends to form signal and coding joints, respectively [2, 25, 26]. The core C-NHEJ factors are required for both coding and signal joins, although DNA-PKcs and Artemis influence coding, much more than signal joint, formation due to their role in opening and processing hairpin intermediates [17]. Intriguingly, a recent study has also implicated XRCC4 and XLF interactions as preferentially affecting coding junctions as well [23].

XLF is the most recent member of the NHEJ pathway identified and its role(s) in CNHEJ and, more specifically, V(D)J recombination is still under investigation [23, 24, 27-33]. The human XLF mRNA is ubiquitously expressed and it encodes a nuclear protein of 299 amino acids with a molecular weight of just 33 kDa [34-36]. XLF is, however, conserved to a low degree from yeast to human [27, 37, 38]. Moreover, the importance of XLF is underscored by the fact that mutation of this gene in human patients results in progressive lymphocytopenia and radiation sensitivity [34, 35].

XLF is similar in structure to XRCC4 [34, 38, 39], interacts with XRCC4 [34, 36, 39-42], with which it can form extensive hetero-filaments [22, 43-45] and is required for CNHEJ and V(D)J recombination [23, 34, 35, 42, 46]. In vitro, XLF stimulates the activity of LIGIV towards non-compatible DNA ends, suggesting that XLF can regulate the activity of XRCC4:LIGIV under at least a subset of conditions [47, 48] and may stimulate end joining by promoting the re-adenylation of LIGIV [49]. Like XRCC4, XLF also interacts with DNA. This interaction is dependent upon the length of the DNA molecule and is enhanced by Ku [13, 41]. It was originally surprising that given the ability of XLF to interact with XRCC4, XRCC4 was not required for the recruitment of XLF to sites of DNA damage in vivo [13]. This observation, however, is consistent with recent work showing that in XRCC4:XLF filaments, the interaction with DNA is mediated almost exclusively via XLF's C-terminus [22]. Like XRCC4, XLF is phosphorylated in vitro at C-terminal sites by the DNA-PK complex and this appears to regulate the ability of the XRCC4:XLF filaments to bridge DNA molecules and possibly regulate V(D)J recombination [23]. XLF is also phosphorylated by both ATM and DNAPK in vivo, however these phosphorylation events are not required for C-NHEJ and their function remains unclear [50].

In mice, deficiency of any of the six non-XLF canonical C-NHEJ factors results in increased IR sensitivity, genomic instability and severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) due to the inability to complete V(D)J recombination [2, 25, 26]. In contrast, while XLF mutations in humans lead to microcephaly and a combined immunodeficiency, the phenotypes are generally less severe than those associated with mutations in other C-NHEJ genes [34, 35]. XLF deficient human fibroblasts [34, 35] and mouse ES cells [51] are IR sensitive and have DSB repair defects, including severely impaired V(D)J recombination. Surprisingly, however, a XLF-null mouse was viable and presented with a very modest defect in chromosomal V(D)J recombination [27]. This data suggested that, during embryonic development, the absence of XLF could be compensated for by other factors. Recent, elegant genetic analyses have confirmed (and complicated) this hypothesis. Thus, mutations in either ATM, H2AX, [29], 53BP1 [30, 31] or DNA-PKcs [32] will greatly exacerbate the V(D)J recombination defects of XLF-null mice, making them as defective as a canonical C-NHEJ mutant mouse. These observations demonstrate — in the mouse — the presence of a lymphocyte-specific compensation mechanism for XLF function. It is likely that a similar compensation exists in human lymphocytes since the XLF-defective patients show a less severe immunodeficiency compared to the other NHEJ-deficient individuals. The precise mechanism by which lymphocyte-specific compensation for the absence of XLF occurs is an important question that still needs to be answered.

To begin to explore the requirement for XLF expression in human somatic cells in more detail, we have disrupted, via gene targeting, the XLF gene in the human adenocarcinoma somatic tissue culture cell line, HCT116. While HCT116 is an immortalized and transformed cell line, it is diploid, has a stable karyotype, and is wild type for most DNA repair, DNA checkpoint, and chromosome stability genes [52]. We describe here the isolation and characterization of HCT116 cell lines that are heterozygous and null for XLF expression. Our data confirm that XLF is not an essential gene in human somatic cells. Moreover, we have used biochemical and cellular approaches to demonstrate that while the majority of phenotypes of XLF-null human somatic cells mirror phenotypes of model murine and patient cell lines, differences were observed that illuminate XLF's role in C-NHEJ in human cells.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture

Human wild type HCT116 cells were cultured in McCoy's 5A media containing 10% fetal calf serum, 100 U/ml penicillin and 50 U/ml streptomycin. The media was also supplemented with L-glutamine. The cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. Cell lines derived from correct targeting events were grown in the presence of 1 mg/ml G418. Cell lines stably infected with pBABE-Puro constructs were selected with 2 μg/ml of puromycin.

2.2. Targeting vector construction

The targeting vectors were constructed utilizing the recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) system [53-55]. Briefly, the right and left homology arms of the XLF targeting were constructed by PCR from HCT116 genomic DNA. The primers used to construct the left homology arm for XLF were XLF4F1, 5’-ATACATACGCGGCCGCTGATCTTCAAGGGTCTTTACCTTCTGTTG-3’ and XLF4R1, 5’-AAGTTATCCGCGGTGGAGCTCCAGCTTTTGTTCCCTTTAGAGATATCAATTAG CCAAAAGACT-3’. The right homology arm was constructed using the primers XLF4F2, 5’-TATGGTACCCAATTCGCCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTACTTCGAGGTAAGAGGAC ATTCTTGGAG-3’ and XLF4R2, 5’-ATACATACGCGGCCGCAACAGAACAGGGCTACTTAGGAAAGAGGA-3’. The arms were used in a fusion PCR reaction, together with a 4-kb PvuI restriction enzyme fragment containing the neomycin drug selection marker. The fusion PCR product was gel purified and ligated to the pAAV backbone using NotI restriction enzyme sites to construct the final targeting vector.

2.3. Packaging and isolating virus

The targeting vector (8.0 μg) was mixed with pAAV-RC and pHelper plasmids (8.0 μg of each) from the AAV Helper-Free System and was transfected into AAV 293 cells using Lipofectamine 2000. Virus was isolated from the AAV 293 cells 48 h after transfection using a freeze-thaw method [53].

2.4. Infections

HCT116 cells were grown to ~70-80% confluence in 6-well tissue culture plates. Fresh media (1.5 ml) was added to the cells 3 h prior to addition of the virus. The required volume of the virus was added drop-wise to the plates. After a 2 h incubation at 37°C, another 1.5 ml of media was added to the plates. After a further 48 h incubation, the cells were transferred to 96-well plates and placed under selection (1 mg/ml G418) to obtain single colonies.

2.5. Isolation of genomic DNA and Southern hybridizations

Chromosomal DNA was prepared, digested, subjected to electrophoresis and then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane as described [56]. The membrane was hybridized with probe a (Fig. 1C) to detect correct targeting of the XLF targeting vector. The probe corresponds to ~550 bp and was made by PCR with the primers XLF5’ProbeF1, 5’-ATGAGTCTGGCTTGCACATGTTATG-3’ and XLF5’ProbeR1, 5’-CATTCTGTGACTAAGGGAAGTTATCAGAC-3’. The PCR product was electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel and gel purified prior to use. Probe ‘neo’ is an internal probe, 416 bp in length, and was obtained by digesting the selection cassette with the restriction enzymes AflIII and ApaLI. The Prime-It® II kit was used to radiolabel the Southern probe with {32P}-α-dATP.

Fig. 1. Generation of XLF heterozygous and null clones.

(A) A cartoon of a partial XLF genomic locus in the HCT116 cell line. Exons are shown (not to scale) as numbered, open rectangles. Restriction enzyme recognition sites are designated as B (BamHI) or N (NheI). The approximate location and direction of exon 4-specific PCR primers are shown as small horizontal arrows. (B) A cartoon of the XLF rAAV targeting vector. In the targeting vector the left and right homology arms (LHA and RHA, respectively) needed to facilitate targeting by homologous recombination are shown as gray rectangles. Open rectangles represent vector sequences not present on the chromosome. The loxP sites are shown as open triangles. The hatched rectangle represents the neomycin-resistance (NEO) gene. The approximate location and direction of vector- and chromosome-specific PCR primers are shown as small horizontal arrows. (C) A cartoon of a first-round targeted allele. The targeting vector has replaced exon 4 on one chromosome. All symbols are the same as in (A and B). The small, black rectangles (a and Neo) represent probes that were used for subsequent Southern blot analyses. (D) A cartoon of the first-round targeted allele following Cre-mediated LoxP recombination. All symbols are the same as in (A, B and C). (E) The identification of XLF+/− cell lines. Four diagnostic PCR reactions were carried out: an experimental 5’ PCR (F1 × LArmR) to confirm correct targeting events on the 5’ side; an experimental 3’ PCR (RArmF × R1) to confirm correct targeting events from the 3’ side; a vector control PCR (RarmF × 4R2) to confirm the presence of the targeting vector in the cell lines; and a DNA quality PCR (4F2 × R1) to confirm the quality of the genomic DNA preparations. All the gels were ethidium bromide-stained, with a marker (M) ladder on the far left. Genomic DNA was isolated and analyzed from the WT HCT116 cell line (+/+, WT), two heterozygous clones (+/NEO, #27 and #72), and two clones (+/+, #38 and #47) in which random targeting had occurred. (F) The identification of XLF−/− cell lines. Three diagnostic PCRs were carried out to confirm the presence (or absence) of exon 4 sequences. The first primer pair was Ex4F1 and 4R2, which scored for the presence of exon 4. This was confirmed with a second PCR (4ExF2 × 4R2). The third primer pair (NEOF2 × R2) scored for the presence of NEO. Genomic DNA was isolated and analyzed from the WT HCT116 cell line (+/+, WT), a heterozygous clone after Cre treatment (+/−, #27cre), the same heterozygous clone before Cre treatment (+/NEO, #27) and a second round targeting clone in which the remaining allele of XLF had been disrupted (−/NEO, #101). All the gels were ethidium bromide-stained, with a marker (M) ladder on the far left.

2.6. Isolation of genomic DNA and genomic PCR

Genomic DNA for PCR screening was isolated using the PUREGENE® DNA purification kit. Cells were harvested from confluent wells of a 24-well culture dish. DNA was dissolved in a final volume of 50 μl, 1 μl of which was used in each PCR reaction. For XLF targeting events, PCR was performed at both the 5’ and 3’ sides of the targeted locus to confirm correct targeting. For the 5’-end, correct targeting was determined using LarmR, 5’- GCTCCAGCTTTTGTTCCCTTTAG and F1, 5’-GTTGTGTGTAGAGTGCGTTGGCTTATA-3’ (Figs. 1B and 1C). For the 3’-end, correct targeting was determined using RArmF and R1, 5’-CAACCACACACACAAGCCACCTAACAC-3’ (Figs. 1B and 1C). As an internal control, PCR was carried out using the primer set RArmF, 5’-CGCCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTAC-3’ and 4R2 (Fig. 1B).

2.7. RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from cells using an RNeasy kit. Reverse transcription PCRs (RT-PCRs) were performed using a Qiagen LongRange two-step RT-PCR kit. Briefly, 2 μg of total RNA was used as a template for the first-strand cDNA synthesis primed by an XLF-specific reverse primer (Cer7/8R), which hybridizes only to the cDNA and not genomic DNA (Fig. 2C). The resulting cDNA was then used in a PCR with three different sets of primers:

CerF1 (5'-TTTCGGTTCGCGCGAGCGGG-3') and Cer7R (5'-AGACCAGTTGTTCTGGCTGG-3')

CerF1 and CerR2 (5'-GGGAAGGACTAGCTAGCATGCAGT-3') or

CerF2 (5'-TTGATTCGTCCTCTGATGGG-3') and Cer7R

Fig. 2. Confirmation of XLF heterozygous and null clones.

(A) An RT-PCR analysis of XLF-deficient cells. A cartoon of the XLF genomic locus showing the approximate locations and size of the relevant exons as well as the position and directionality of the primers used for the RT-PCR analysis. (B) Total mRNA was purified from the indicated cell lines (designations are the same as in Fig. 1) and then reverse transcribed using primer Cer7/8 R1, which can only amplify mRNA and not genomic DNA. This first strand cDNA was then used in three different PCR reactions with the primer pairs indicated on the right side of the panel. The PCR products were identified by their indicated sizes (in bp) on an ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel. (C) XLF-null cells lack detectable XLF protein. Whole-cell extracts were prepared from the parental cell line (+/+, WT), two heterozygous clones (+/−, #27 and #72) and two null clones (−/−, #101 and #320). The extracts were then analyzed by immunoblot for XLF protein and then sequentially probed with three more antibodies: XRCC4, LIGIV and, as a loading control, α-tubulin. (D) Complementation of null clones. A wild-type, L115A or L179A mutant XLF cDNA was stably expressed in XLF−/− cells (−/−, #101) using a retroviral vector. Two wild-type complemented clones (clones #1 and #2) and a singly complemented clone for each of the mutants (L115A & L179A) are shown along with the parental (+/+, WT) cell line. Whole-cell extracts from the indicated cell lines were then analyzed by immunoblot for XLF or, as a loading control, α-tubulin.

2.8. Expression constructs

For creation of stable, XLF-complemented cell lines, a full-length XLF cDNA was cloned into the pBABE-Puro [34] eukaryotic expression vector. For pCherry expression constructs, a wild-type XLF full-length cDNA was cloned into a pCherry expression vector. Subsequently, point mutations in the XLF cDNA were introduced using a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit. Primers sequences are available upon request.

2.9. Whole cell extract preparation

Cells were trypsinized and washed twice with phosphate buffered saline. For whole cell extraction, cells were boiled in lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM PMSF, 1X protease inhibitor cocktail; Roche) for 5 min. The samples were then digested with DNase I (0.1 U/μl) for 10 min at 37°C. The samples were finally boiled in 5X sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) buffer (0.225 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 50% {v/v} glycerol, 5% SDS, 0.05% bromophenol blue, 0.14 M β-mercaptoethanol).

2.10. Immunoblotting

For immunoblot detection, proteins were subjected to electrophoresis on a 4 to 20% gradient gel, electroblotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane and detected as described [57]. The relevant antibodies were as follows: a polyclonal rabbit XLF antibody raised against the region between amino acids 250 and 299 was from Bethyl Laboratories. Anti-XRCC4 (AHP 387) and anti-DNA LigIV (AHP 554) were purchased from Serotec. An α-tubulin antibody was obtained from Covance and a GFP antibody (JL-8) was purchased from Clontech.

2.11. Cell proliferation assay

To obtain a growth curve, 3 × 104 HCT116 cells were plated in each well of a 6-well plate in duplicate. Cell numbers were determined using a hemacytometer and triplicate counting everyday thereafter starting at day four utilizing growth media without selection.

2.12. X-ray survival assay

For HCT116 cell lines, 300 cells were seeded into each well of a 6-well tissue culture plate about 10 to 12 h before irradiation. Cells were then X-irradiated using a 137Cs source at the indicated doses. After irradiation, HCT116 cells were allowed to grow for 10 to 14 days before the colonies were fixed, stained, counted and a cell survival percentage was calculated [58].

2.13. Etoposide sensitivity assay

300 cells were seeded into each well of a 6-well tissue culture dish in duplicate 16 h prior to drug treatment. Etoposide was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide to give a 10 mM stock solution and subsequently diluted in medium at the indicated final concentration. Cells were incubated in etoposide-containing medium for 12 days at 37°C, and then fixed, stained with crystal violet and counted as described above.

2.14. Extrachromosomal DNA repair assays, transfections and FACS analysis

The in vivo end-joining reporter plasmid pEGFP-Pem1-Ad2 has been described [52, 59]. The plasmid was digested to completion (8 to 12 h) with HindIII or I-SceI (NEB) to generate different types of DNA ends. Supercoiled pEGFP-Pem1 plasmid was used to optimize the transfection and analysis conditions. The pCherry plasmid was cotransfected with either linearized pEGFP-Pem1-Ad2 or with supercoiled pEGFP-Pem1 as a control of transfection efficiency. Cells were subcultured a day before transfection and were 60 to 70% confluent at the time of transfection. All the plasmids were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 according to manufacturer's (Invitrogen) instructions. Green (pEGFP-Pem1) and red (pCherry) fluorescence were measured by flow cytometry 24 h later [52]. For FACS analysis, cells were harvested, washed in 1X phosphate buffered saline and fixed using 2% paraformaldehyde before FACS analysis was performed on a FACSCalibur instrument. For the HCT116 cell line a red-versus-green standard curve was derived with varying amount of cherry and green plasmid to avoid measurements near the plateau region. The values of repaired events are reported as a ratio of cells that were double positive for red and green fluorescence over total cells that were only positive for red fluorescence. This ratio normalizes the repair events to the transfection controls. The value of end joining for the mutants is reported as a percent of the activity of the wild type cells. The FACS data was analyzed and plotted using FlowJo 8.5.2 software.

The extrachromosomal reporters for detecting specifically HR {DR-GFP; [60]}, single-strand annealing {SSA, SA-GFP; [61]} and A-NHEJ {EJ2-GFP+; [62]} have been described. Briefly, cells were subcultured in 6-well tissue culture plates. The next day, the cells were transfected with 0.5 μg pCherry, 1.0 μg of an I-SceI expression plasmid and 1.0 μg DR-GFP, SA-GFP or EJ2-GFP+ assay substrates. GFP and mCherry expression was then analyzed 48 hr post transfection using flow cytometry as described above. The repair efficiency was calculated as the percentage of GFP and mCherry doubly positive cells divided by the mCherry-positive cells.

2.15. Microhomology assay

The microhomology assay (which is an independent measure of A-NHEJ) was performed as described [52, 63]. In brief, 2.5 μg of EcoRV- and AfeI-digested plasmid pDVG94 was transfected into cells (at ~60% confluency), in 6-well plates, using Lipofectamine 2000 according to manufacturer's (Invitrogen) instruction. The transfection efficiency of wild type HCT116 and the mutant cell lines were determined using the pEGFP-Pem1 plasmid described above. After transfection (48 h), pDVG94 plasmid DNA was recovered using a modified Qiagen miniprep protocol [52]. Repaired pDVG94 plasmid was PCR amplified using primer FM30 and a radiolabeled DAR5 primer [63]. The radioactive PCR product was then digested with BstXI and the resulting restriction fragments were separated along with any undigested PCR product in a 6% polyacrylamide gel. The gel was subsequently dried and exposed to film. The bands representing the undigested PCR product (180 bp) or restriction enzyme-digested (120 bp) product produced by BstXI digestion were quantified using ImageQuant software and compared.

2.16. V(D)J recombination assay

Extrachromosomal V(D)J recombination assays were carried out using pGG49 and pGG51 reporter plasmids to monitor signal joint or coding joint formation, respectively [64, 65]. Briefly, 3 μg of one of the reporter plasmids was transfected along with 8 μg each of RAG-1 and RAG-2 expression vectors [66] into 106 exponentially growing cells using Lipofectamine 2000. The cells were then incubated for 48 h at 37°C prior to recovery of the reporter plasmid by a modified Qiagen miniprep protocol [52]. Isolated plasmids were treated with the restriction enzyme DpnI (to remove un-replicated plasmids), transfected into chemically competent Top10 cells and then plated on ampicillin (100 μg/ml) or ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and chloramphenicol (22 μg/ml) plates. DAC colonies (DAC = DpnI-treated-AmpR-CamR) represent V(D)J recombination events, whereas DA colonies (DA = DpnI-treated-AmpR) are a measure of total plasmids recovered from each transfection. The percentage of signal joint or coding joint formation was calculated by dividing DAC by DA counts.

2.17. Telomere FISH

Cells were treated with colcemid at 100 μg/ml for 3 h to obtain metaphases. The cells were then trypsinized and harvested by centrifugation. Metaphase spreads were prepared according to the manufacturer's (Dako) instruction. A Cy3-PNA telomere-specific probe was hybridized according to the protocol supplied by the manufacturer except that the sample was denatured at 85°C to 90°C for 8 min and then incubated in humidified chamber overnight at 37°C. The fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) images were captured and processed with FluoView 1000 software using an Olympus IX2 Inverted Confocal Microscope.

2.18. Immunostaining

The indicated cell lines were grown on 4-well chamber slides for 1 day. The cells were then transfected with 2 μg of a pCherry plasmid carrying either a wild type or mutant XLF cDNA. After transfection (24 h), cells were harvested and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in phosphate buffered saline for 5 min at room temperature. DAPI was used to stain the nucleus. Images were captured with Zeiss Axiovert 2 Upright Microscope

2.19. Cytogenetic analyses

G-banding cytogenetic analyses were performed in the Cytogenomics Core Laboratory at the University of Minnesota as described [67].

2.20. Immunofluorescence staining for Rad51 foci

Cells were seeded onto 4-well chamber slides and irradiated with 6 Gy of gamma rays. 3 h later cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 20 min at room temperature, permeabilized on ice for 10 min with PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 and blocked with 5% BSA/PBS at room temperature for 20 min. The cells were then immunostained with a Rad51 antibody (Santa Cruz) at a 1:500 dilution in 1.5% BSA/PBS overnight at 4 °C. Subsequently, the cells were washed three times (30 min each) with PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and the cells were further incubated with 1 μg/mL fluorescent secondary antibodies in PBS containing 1.5% BSA/PBS for 1 h at room temperature, washed again with PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100, and incubated with PBS containing 1 μg/mL of 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Images were obtained and processed using a DeltaVision deconvolution fluorescence microscope and SoftWoRx software (Applied Precision) as described above. Images were acquired with five Z-series optical sections at 0.5-μm steps. The average number of Rad51 foci was determined after scoring at least 100 nuclei.

3. Results

3.1. Generation of heterozygous XLF+/− HCT116 cell lines

To characterize the function of XLF in human cells, we utilized a rAAV-mediated gene targeting strategy [53, 55] to replace exon 4 of the XLF locus in a well-characterized, diploid, human colon carcinoma cell line, HCT116, with a LoxP-flanked copy of the neomycin phosphotransferase (NEO) drug resistance marker (Fig. 1). XLF is encoded by 8 exons on chromosome 2 (Fig. 1A). Exon 4 was chosen for two reasons. First, any expression of the first 3 exons should yield a greatly truncated protein missing its XRCC4 and LIGIV interaction domains [38, 39] and second, splicing over the deleted sequence should generate an out-of-frame protein. The targeting vector contained ~900 bp long left and right homology arms (LHA & RHA, respectively) bordering a floxed (flanked by LoxP sites) neomycin-resistant (NEO) selection cassette (Fig. 1B). Correct targeting of the endogenous genomic XLF locus should delete exon 4 and simultaneously result in a G418-resistant cell line (Fig. 1C). Five correctly targeted clones (XLF+/NEO) were identified from 201 NEO-resistant clones for a gene targeting frequency of 2.5%, which is comparable to other rAAV-mediated studies [68, 69]. The five clones (the analysis of two: #27 and #72 is shown) were confirmed as being correctly targeted using PCR strategies to demonstrate the presence of the 5’- and 3’-ends of the targeting vector at the proper genomic location (Fig. 1E). In contrast, two randomly targeted clones (#38 and #47) produced no such PCR product (Fig. 1E). Control PCRs were also performed to confirm the presence of the vector sequence in all G418-resistant clones (Fig. 1E, Vector Control), and to check the quality of isolated DNA (Fig. 1E, DNA Quality).

3.2. Generation of XLF−/− cell lines

To construct a XLF−/− cell line, one of the XLF+/NEO cell lines (#27) was transiently exposed to Cre recombinase. Cre should excise the internal NEO cassette (Fig. 1D), and render the resulting clone sensitive to G418. Correct excision of the NEO gene was confirmed by the absence of a diagnostic PCR product (e.g., #27cre; Fig. 1F). One of several such clones (XLF+/−) obtained in this fashion was then used for a second round of gene targeting with the original targeting vector. Productive infection produced one of three outcomes: i) random targeting (the majority of the events), ii) correct targeting, but of the already inactivated allele from the first round of targeting (i.e., “re-targeting”); or iii) correct targeting of the remaining allele to generate the desired null clone. Six correctly targeted clones from 290 G418 resistant, internal-control-PCR-positive clones (targeting frequency of 2.1%) were identified. A diagnostic PCR strategy was then utilized to distinguish re-targeting from null events. Four out of the six clones were retargeted. The conclusion was drawn by the fact that although four clones were correctly targeted, they still retained exon 4 (data not shown) whereas two clones {#101 (Fig. 1F) and #320 (see below)} lacked exon 4.

Southern hybridization confirmed the authenticity of the targeting events. Genomic DNA was isolated and digested with the restriction enzymes BamH1 and NheI. Importantly, the NheI site in exon 4 should be lost if correct targeting has occurred (Fig. 1A). Southern blot analysis was then performed using either a 5’-probe (probe “a”; Fig. 1C) or a probe corresponding to the vector sequence (probe “Neo”; Fig. 1C). For the 5’-end Southern analysis, the appearance of a novel ~6 kb band caused by the absence of the NheI site and the presence of the targeting vector, confirmed that correct targeting events had occurred in one of the original heterozygous clones (#27, XLF+/NEO; Supplemental Fig. 1A) as well as in one of the putative null clones (#101, XLF−/NEO; Supplemental Fig. 1A). The ~6-kb band was absent from the parental HCT116 cell line (WT), where only the expected endogenous ~2.4-kb band was observed (Supplemental Fig. 1A). Excision of the NEO cassette from one of the XLF alleles via Cre recombination resulted in the reduction of the ~6 kb 5’-flanking fragment to ~3.8 kb, as expected (Supplemental Fig. 1A). When genomic DNA from the indicated lines was digested with BamHI alone and probed with “Neo”, clones #27 (XLF+/NEO) and #101 (XLF−/NEO) exhibited a single ~6 kb band corresponding to the correct insertion of the targeting vector whereas this band was absent, as expected, in the parental HCT116 cell line (Supplemental Fig. 1B).

To confirm that no full-length XLF mRNA was produced in the XLF-null cells, total mRNA was isolated and first strand cDNA was generated using a primer (cer7/8R1) that spanned exon 7 and 8 sequences, which ensured that only mRNA, and not genomic DNA, was amplified (Fig. 2A). The resulting cDNA was then subjected to PCR using primers (CerF1 and Cer7R) complementary to sequences located in exon 1 and exon 7, respectively (Fig. 2A). A 855 bp PCR product corresponding to the region encompassing exons 1 to 7 was produced from mRNA isolated from the parental cell line (HCT116 WT), a randomly targeted clone (#38) and XLF +/− cell line (#27) but was absent from the XLF−/NEO (#101) clone (Fig. 2B), demonstrating that XLF−/NEO did not produce any detectable full-length XLF mRNA. A faint, truncated 716 bp band was detected with the XLF−/NEO clone (Fig. 2B). This product corresponded to the skipping of exon 4 — which generates an out-of-frame mRNA and cannot encode for a functional XLF protein. All of the cell lines produced a RT-PCR product corresponding to exons 1 through 3 (Fig. 2B). In contrast, a 382 bp RT-PCR band diagnostic of an mRNA containing exons 4 through 7 was specifically absent in the XLF−/NEO cell line (#101; Fig. 2B), demonstrating the successful homozygous deletion of exon 4 from the XLF genomic locus.

Finally, the residual copy of NEO was excised from the two XLF−/NEO clones (#101 & #320) by Cre expression to generate derivatives that were null for XLF and were G418 sensitive (XLF−/− clones). These clones were then analyzed for protein expression levels by immunoblot analysis using a rabbit polyclonal XLF antibody raised against the C-terminus of XLF. The XLF+/− clones (#27 and #72) expressed XLF at a level ~50% of that observed for the parental cells with α-tubulin utilized as a loading control (Fig. 2C), while neither XLF−/− cell line contained any detectable wild type (or truncated) protein (Fig. 2C). To check whether a XLF deficiency affected the expression or stability of XRCC4 or LIGIV, the same immunoblot was stripped and blotted sequentially with antibodies against XRCC4 and LIGIV. The absence of XLF protein had no significant effect on XRCC4 or LIGIV protein levels (Fig. 2C), leading us to conclude that XLF is dispensable for the stability of both XRCC4 and LIGIV.

In summary, based upon the PCR, Southern, RT-PCR and Western blot analyses (Figs. 1 and 2 and Supplemental Fig. 1) we concluded that the XLF−/− cell lines represented two true null clones.

3.3. Complementation of the XLF-deficient cell lines

One of the XLF−/− cell lines (#101) was stably complemented with either a wild type XLF cDNA or cDNAs containing either a L115A or L179A mutation. Two wild-type clones were selected that expressed slightly less (clone 1) or more (clone 2) XLF than the parental cells (Fig. 2D). L115A and L179A are not naturally occurring patient mutations [34, 35], but several groups have implicated these residues as being critical either for XRCC4 interaction and LIGIV activity, respectively [22, 23, 38, 39, 42-45]. The mutant proteins were expressed at a level comparable to that observed in the parental cell line (Fig. 2D).

3.4. XLF-deficient cells are impaired for repairing DSBs

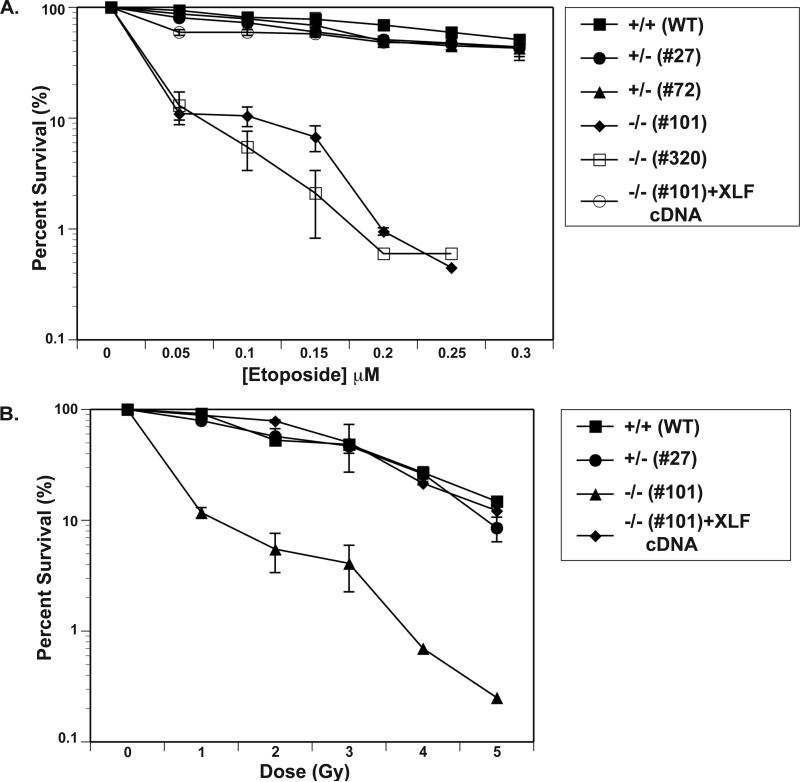

One of the hallmarks of patient cell lines harboring XLF mutations and/or murine cell lines engineered to mimic XLF loss-of-function mutations is that they are very sensitive to DNA damaging agents [27, 35, 51]. To determine if this phenotype could be extended to our model cell lines, we treated them with a radiomimetic drug, etoposide, which is a topoisomerase II inhibitor and a potent inducer of DNA DSBs [70]. The XLF+/− cell lines (#27 and #72) were as sensitive as WT HCT116 cells (Fig. 3A), suggesting that, as we previously inferred [52], there is no haploinsufficiency associated with XLF loss-of-function. In contrast, the XLF−/− cell lines (#101 and #320) were extremely sensitive to etoposide and this phenotype could be completely rescued by the re-expression of the wild type XLF cDNA (Fig. 3A). In addition, the sensitivity of the cell lines to IR was determined. The D37 (the dose required to reduce survival to 37%) for parental and the XLF+/− line (#27), was 3.5 Gy (again demonstrating no obvious haploinsufficiency), whereas D37 for one of the XLF−/− cell lines (#101) was ~0.5 Gy (Fig. 3B). The stable expression of a full-length XLF in XLF−/− cells restored the IR sensitivity back to levels indistinguishable from wild type, demonstrating that a XLF deficiency was specifically responsible for the increased IR sensitivity of the XLF−/− cell lines (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3. The etoposide and IR sensitivity of XLF-null clones.

(A) Etoposide sensitivity. Three hundred parental (+/+, WT), heterozygous (+/−, #27 and #72), null (−/−, #101 and #320), or XLF-null complemented {−/−, (#101)+XLF cDNA} cells were seeded on tissue culture plates in duplicate and exposed to the indicated levels of etoposide. Cells surviving to form colonies of at least 50 cells after 15 days were scored and reported as percent survival. (B) IR sensitivity. Three hundred cells of the indicated genotypes (as indicated above) were seeded on tissue culture plates in duplicate and X-irradiated at the indicated doses. Cells surviving to form colonies of at least 50 cells after 15 days were scored. Both panels show the averages (+/− standard deviation) of at least two independent experiments.

To determine whether the etoposide and IR hypersensitivities of XLF-deficient cell lines were associated with an intrinsic defect in DNA DSB repair, the capacity of XLF-deficient cells to perform NHEJ using an in vivo plasmid end joining assay [52, 59] was measured. In this assay, extrachromosomal end joining is measured by the reconstitution of GFP expression. The principle characteristic of the assay plasmid (pEGFP-Pem1-Ad2) is the interruption of the EGFP sequence by the Pem1 intron, within which restriction sites for HindIII have been engineered both upstream and downstream of the Ad2 exon (Fig. 4A). Digestion with HindIII at both sites generates a linear plasmid with cohesive 5’-overhangs. Because of the retention of the Ad2 exon, un-digested or partially-digested products generate — upon ligation — a product unable to express GFP. Due to the extensive “buffering” capacity of the intron, end joining of the transfected, linearized plasmid by the cellular NHEJ repair pathway re-constitutes GFP expression, even when extensive additions or deletions of nucleotides have occurred [52, 59]. A final advantage of the assay is that when HindIII-linearized plasmid is introduced into the cell line to be queried, intracellular circularization allowing GFP expression can be detected and quantitated by flow cytometry within 48 hr post-transfection. Thus, we used this assay to assess the NHEJ capacity of the XLF mutant cell lines. The parental cell line repaired this linearized construct at least an order of magnitude better than the XLF-null cells and, as expected, the XLF-null cells complemented with a wild-type cDNA had almost wild-type levels of NHEJ activity (Figs. 4B & 4C). Unexpectedly, the XLF-null cells complemented with the XLF cDNAs expressing L115A and L179A mutants repaired as robustly as the parental cell line and the XLF-null cells complemented with a wild-type cDNA (Fig. 4B & 4C).

Fig. 4. The NHEJ activity of XLF-null and complemented cell lines.

(A) A cartoon of the reporter substrate used for the analysis of NHEJ. The reporter vector consists of GFP interrupted by an artificially-engineered intron, which itself is interrupted by an adenoviral exon flanked by restriction sites (HindIII) that are used to linearize the vector. (B) The efficiency of NHEJ in the parental (+/+, WT), null (−/−, #101) or null cell line complemented with either a wild-type (+XLF cDNA), L115A (+L115A XLF cDNA) or L179A (+L179A XLF cDNA) cDNA is shown. The indicated cells were cotransfected with the HindIII-digested reporter substrate and (as a transfection control) a pCherry expression vector. The number of green (GFP+) and cherry positive cells was determined by FACS analysis. The fraction of cells that were doubly green and cherry is shown in the upper right quadrant of each panel. (C) Quantitation of the results shown in (B), plotted as relative plasmid rejoining. The ratio of GFP+:Cherry+ to Cherry+ was used as a measure of NHEJ efficiency. The profiles show the average (+/− the standard deviation) of at least two independent experiments.

To confirm these results we used a complementary assay. The reporter plasmid (pDVG94) for this assay is biased towards detecting A-NHEJ events and is designed such that the relative efficiency of C-NHEJ versus A-NHEJ events can be assessed [52, 63]. When pDVG94 is restriction digested with AfeI and EcoRV it results in a blunt-ended, linear substrate with 6-bp repeats at both ends (Fig. 5A). C-NHEJ can rejoin these ends, which yields a wide variety of junctions but A-NHEJ generates almost exclusively a single product in which the 2 repeats have been reduced to one and in the process generates a novel BstXI restriction enzyme site (Fig. 5A). Thus, linearized pDVG94 plasmid was transfected into XLF-null cells as well as cells expressing wild type, L115A or L179A XLF cDNAs and 48 hr later, repaired plasmids were recovered, and then used as substrates for PCR using a 5’-radiolabeled PCR primer (Fig. 5B). The level of ANHEJ was subsequently determined by quantitation of the BstXI-digested PCR products. For XLF-null cells 97% of all the repair products were mediated by A-NHEJ as shown by their susceptibility to BstXI digestion (Fig. 5C). In contrast, this cleavage product was produced only about 2% to 3% of the time from the plasmids re-isolated from either the wild-type or the null cell line complemented with a wild-type or mutant (L115A and L179A) cDNA. From these experiments (Figs. 4 and 5), we conclude that although XLF-deficient cells carry out very little end-joining the end-joining that they do carry out is almost exclusively A-NHEJ whereas XLF-proficient cells — including XLF-deficient cells complemented with mutant (L115A and L179A) cDNAs — robustly utilize almost exclusively C-NHEJ.

Fig. 5. XLF-null cell lines utilize A-NHEJ almost exclusively.

(A) A cartoon of a reporter plasmid biased towards the detection of A-NHEJ. The reporter has been designed such that cleavage with Eco47III and EcoRV results in a blunt-ended linear substrate with 6-bp direct repeats (boxes) at both ends. C-NHEJ joining will result in the retention of some of both repeats whereas microhomology-mediated end joining should generate a single, perfect repeat, which is a substrate for BstXI. This panel is excerpted from Verkaik et al., 2002, Eur. J. Immunol., 32:701. (B) The experimental scheme for analysis of the plasmids recovered from transfected cells. The plasmids were subjected to PCR using one radiolabeled (asterisk) primer. The PCR products were then subjected to BstXI restriction enzyme digestion. (C) Autoradiograms of representative A-NHEJ assays using the indicated cell lines (designations the same as in Fig. 4). The size of the primary PCR product (180 bp) and the BstXI cleavage product (120 bp) are indicated. Two independent experiments similar to the one shown were quantitated with a phosphoimager and averaged and are reported under the panel as “Microhomology Use”.

3.5. The absence of XLF leads to defects in V(D)J recombination in human cells

To evaluate the role of XLF in V(D)J recombination in human cells, we used a transient V(D)J recombination assay [64, 65]. Wild type HCT116, XLF+/−, XLF−/− and XLF−/− cell lines expressing either a full-length, wild type XLF or mutant XLF cDNA were transfected with vectors that expressed full-length RAG1 and RAG2 proteins and a plasmid recombination substrate that was designed to measure the frequency of either signal joint (pGG49) or coding joint (pGG51) formation. The reporter plasmids pGG49 and pGG51 constitutively confer ampicillin resistance and if they undergo V(D)J recombination inside of the transfected cells they will also acquire resistance to chloramphenicol, which can be subsequently quantitated [64, 65]. XLF-null human cells were at least 1 to 2 orders of magnitude (~50-fold) more deficient for both signal joint and coding joint formation than the parental cell line, whereas heterozygous XLF cells were capable of performing V(D)J recombination at essentially wild-type levels (Table 1). To confirm that the signal and coding joining defects observed in XLF−/− cells were due to the absence of XLF, we also assayed XLF−/− cells expressing a full-length, wild type XLF cDNA and observed that these cells carried out V(D)J signal and coding joint formation at wild type levels indicating that the observed defects in XLF−/− cells were specifically associated with the deletion of XLF gene (Table 1). Finally, and consistent with the repair data, the XLF−/− cells complemented with cDNAs expressing either L115A and L179A mutant cDNAs complemented the XLF deficiency to ~wild-type levels indicating that these mutations do not abrogate XLF function.

Table 1.

V(D)J Recombination

| Substrate |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pGG49 (SJ Substrate) |

pGG51 (CJ Substrate) |

|||||

| Cell Lines | DAC/DAa | SJ (%) | Relative Eff. (%) | DAC/DAa | CJ (%) | Relative Eff. (%) |

| WT HCT116 | 107/129600 | 0.82 | 257/120000 | 0.21 | ||

| 2625/72000 | 3.64 | 100 | 32/6000 | 0.53 | 100 | |

| 2014/1200000 | 0.16 | 27/43200 | 0.06 | |||

| +/- (#27) | 96/77400 | 0.12 | 160/65400 | 0.24 | ||

| 214/180000 | 0.11 | 64 | 10/3600 | 0.27 | 140 | |

| 942/324000 | 0.29 | 64/20700 | 0.30 | |||

| -/- (#101) | 21/450000 | 0.005 | 0/10950 | 0.000 | ||

| 21/420000 | 0.005 | 2 | 0/70200 | 0.000 | 2 | |

| 53/468000 | 0.001 | 10/186000 | 0.005 | |||

| +WT cDNA | 685/87300 | 0.78 | 214/87300 | 0.24 | ||

| 1928/540000 | 0.35 | 123 | 192/540000 | 0.04 | 36 | |

| 106/23880 | 0.44 | 31/27360 | 0.11 | |||

| +L115A cDNA | 61/31440 | 0.19 | 222/69300 | 0.32 | ||

| 25/17800 | 0.14 | 58 | 96/80000 | 0.12 | 120 | |

| 156/74200 | 0.21 | 172/68800 | 0.25 | |||

| +L179A cDNA | 360/240000 | 0.15 | 181/45250 | 0.42 | ||

| 97/40400 | 0.24 | 45 | 121/75600 | 0.16 | 142 | |

| 181/139200 | 0.13 | 223/76800 | 0.29 | |||

Transient V(D)J recombination assays were performed in the presence of RAG-1 and RAG-2 expression vectors.

DAC, numbers of ampicillin-chloramphenicol-resistant E. coli transformants after DpnI treatment; DA, numbers of ampicillin-resistant transformants after DpnI treatment.

3.5. The absence of XLF leads to an increase in HR

As detailed in the introduction, XLF-null mutants usually present with phenotypes less severe than those associated with mutations in other C-NHEJ genes [34, 35]. These observations suggested that — in the mouse — the absence of XLF could be compensated for by other repair pathways; a hypothesis recently validated by experimental data [29-32]. We have demonstrated that the loss of Ku expression from human somatic cells results in an up-regulation of both A-NHEJ [52] and HR [68]. To experimentally address whether a similar enhancement of these alternative DSB repair pathways was occurring in XLF-null cells we queried for their presence with transient extrachromosomal reporters, that detect either gene conversion-mediated HR {DR-GFP; [60]}, single-strand annealing (SSA), a HR subpathway {SA-GFP; [61]} or A-NHEJ {EJ2-GFP+; [62]}. The design of the vectors and the experimental strategy were very similar to that detailed above for pEGFP-Pem1-Ad2 and C-NHEJ. Thus, each of the vectors was linearized by I-SceI restriction enzyme digestion, transfected into cells and then GFP activity was measured 48 hr later (Fig. 6A). These assays demonstrated that the level of gene conversion-mediated HR and SSA were significantly (p = 0.0003 and 0.0119, respectively) elevated approximately 2-fold in XLF-null cells, whereas A-NHEJ activity was not affected (Fig. 6B). For both HR and SSA, the enhanced activity could be completely suppressed by the re-introduction of a wild type XLF cDNA (Fig. 6B). To extend these studies, we also X-irradiated (6 Gy) the cell lines and then 3 hr later assessed them for the appearance of Rad51, a key HR factor, foci (Fig. 6C). As suggested by the repair assays, XLF-null cells exhibited about a 3-fold enhancement of Rad51 focus formation, a phenotype that could, at least partially, be complemented by the re-expression of XLF (Fig. 6D). These data demonstrated that XLF-null human cells display an enhanced ability to carry out HR.

Fig. 6. XLF-null cell lines are upregulated for HR.

(A) The three reporter vectors are cartooned. The top vector detects gene conversion-mediated HR. The middle vector detects SSA and the bottom vector detects microhomology-mediated ANHEJ. All three plasmids require prior linearization by ISceI restriction enzyme digestion and depend upon restoring a GFP coding sequence that can be used for detection and quantitation. A pCherry plasmid (not shown) was used with each reporter as a transfection control. (B) Quantitation of the results of two independent experiments, plotted as repair efficiency normalized to the parental HCT116 cell line. The ratio of GFP+:Cherry+ to Cherry+ was used as a measure of NHEJ efficiency. ***, p = 0.0003; *, p = 0.0119. (C) A) Representative images of wild type HCT116, XLF−/− and XLF−/− + a wild-type XLF cDNA cells immunostained with an anti-Rad51 antibody (red) 3 hr after gamma-irradiation. Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). (D) Average numbers of Rad51 foci at 3 h post-irradiation are plotted for wild type HCT116, XLF−/− and XLF−/− + a wild-type XLF cDNA complemented cells.

3.6. Intracellular localization of mutant XLF proteins

Finally, to expand upon these studies, we also constructed and independently expressed three naturally occurring patient mutations: R57G, C123R and R178X [35]. As expected, none of the cDNAs encoding these mutants was capable of restoring any NHEJ activity to the XLF-null cell line as assessed by any of the in vivo plasmid end-joining assays (data not shown). To try and explore the lack of complementation in more detail, fusion proteins with pCherry were made for each of these proteins as well as for the wild type and the L115A and L179A derivatives. These constructs were then transiently transfected into the XLF-null cell line. The L115A, L179A and R178X proteins were expressed at levels comparable to wild type (Fig. 7A). C123R and R57G were expressed less well, suggesting that the mutations result in misfolded and/or unstable proteins as has been previously suggested [39, 41, 43]. All of the proteins were expressed at sufficient levels, however, to determine their cellular localization. As expected, the wild-type protein showed predominately nuclear staining although some of the protein could be detected in the cytoplasm (Fig. 7B). In contrast, the L115A, L179A and R178X mutant proteins showed significantly more cytoplasmic expression. The C123R and especially the R57G proteins, however, were virtually cytoplasmic (Fig. 7B). A comparable result for R57G using a c-myc epitope tag and a different cell line has also been reported [41], suggesting that this is a biologically relevant and reproducible result. Several tentative conclusions can be drawn from these results. First, the patient mutations C123R and R57G appear to result in unstable proteins that mis-localize to the cytoplasm. Secondly, it appears as if the wild type XLF protein is regulated by nuclear/cytoplasmic partitioning. If the latter conclusion is true, the mechanism is probably atypical as the R178X mutation, which removes a classical monopartite nuclear localization signal located at the extreme C-terminus of the protein [71], still localizes to the nucleus as well as wild-type protein. Moreover, although XLF is an extremely leucine-rich protein (42 of 299 residues are leucine), there are no obvious leucine-rich nuclear export consensus sequences [72]. Taken together, this data implies that the C123R and R57G residues, which in 3-dimentional space reside near each other [34, 38, 39] may define a nuclear localization, retention or export domain.

Fig. 7. Localization of pCherry-tagged XLF and XLF mutant proteins.

(A) XLF−/− cells (clone #101) were transiently transfected with a cDNA encoding either wild type (WT) or the indicated mutant XLF cDNAs, all of which were expressed as pCherry fusion proteins. Whole cell extracts were prepared from each of the indicated cell lines and probed with XLF or, as a loading control, actin antibodies. The asterisk (*) indicates a truncated XLF protein. (B) The identical pCherry-tagged cDNAs were transiently expressed in XLF−/− cells (clone #101) and the localization of the tagged XLF protein was examined by fluorescent microscopy. A single representative image for each of the indicated cell lines is shown.

4. Discussion

C-NHEJ is the major DNA DSB repair pathway in humans and defects in any of the seven integral C-NHEJ factors results in either severe pathological consequences or death. Because of its importance, C-NHEJ has been studied in a bevy of model systems, including yeast and mice and these studies have led to many significant mechanistic insights [2, 8]. Ultimately, however, the goal of such research is to apply the gleaned knowledge to the treatment of human patients. To this end, a number of investigators have also studied immortalized cell lines derived from C-NHEJ-mutant patients, in the hopes that these cell lines might mimic the biology of the patient as well as, or better than, non-human model systems. Although these studies have, like the yeast and mouse work, been informative, the data generated from them has been tempered by the genetic and phenotypic variability inherent in the human population. Several years ago — as an alternative model system — we set out to create a panel of isogenic human somatic cell lines containing loss-of-function mutations for all of the DNA DSB genes with a specific emphasis on C-NHEJ genes. The cell line we chose was HCT116. HCT116 is a human adenocarcinoma somatic tissue culture cell line that is mismatch repair defective [73, 74]. A disadvantage of this cell line is that defects in mismatch repair have been implicated in reducing the efficacy of both HR- and NHEJ-mediated DSB repair {reviewed by [75]}. Moreover, the cell line contains slightly reduced levels of Mre11, an important repair gene that has a documented role in HR and which is probably involved in A-NHEJ as well {reviewed in [76]}. Despite these deficiencies, HCT116 is only slightly diminished for general NHEJ activity [77]. In addition, it is diploid, has a stable karyotype, exhibits normal DNA damage checkpoints and is wild type for all of the other known DNA DSB repair genes {reviewed in [78]}. These latter facts, combined with the previous extensive use of HCT116 in gene targeting studies {reviewed in [78]} recommended this cell line for these analyses.

To this end, we have used rAAV-mediated gene targeting [55] to generate derivative cell lines that are reduced or deficient in the expression of Ku70 [68], Ku86 [79, 80], DNA-PKcs [69], LIGIV [81] and, now, XLF. In addition, we have also constructed viable null cell lines for XRCC4 and Artemis (B. Ruis and E. A. Hendrickson, unpublished data) such that a null or conditionally-null human cell line for every integral C-NHEJ gene now exists. Although gene targeting in human somatic cells is not novel {reviewed in [55, 78]}, this is, to our knowledge, the first demonstration of an entire pathway of genes being inactivated in human somatic cells and it should provide a rich source of reagents for doing structure:function (as described previously and herein) or epistasis analyses {e.g., [81]}.

Specifically, we have demonstrated that the inactivation of XLF in HCT116 cells results in modest proliferation defects (Supplemental Fig. 2), a profound hypersensitivity to DNA damaging agents (Fig. 3), and in severe defects in DSB repair (Figs. 4 and 5) and in extra-chromosomal V(D)J recombination (Table 1). These features are consistent with the phenotypes of human patients with XLF mutations [34, 35] and XLF-deficient mouse ES cells [51] and consequently validate this cell line as a tractable model system for elucidating XLF functions.

The loss of even one XLF allele resulted in a modest proliferation defect that was exacerbated with the loss of remaining XLF allele (Supplemental Fig. 2). This phenotype was not observed in XLF-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts [27], but is consistent with the phenotypes of human patients carrying XLF mutations [35]. Moreover, this phenotype is quite similar to human somatic cell lacking either LIGIV [81] or XRCC4 (B. Ruis and E. Hendrickson, unpublished data), where a nearly identical modest proliferation defect was observed. The cause of the reduced proliferation is unknown, but it likely is linked to the genomic instability of the cell line, which, in turn, ultimately results in higher levels of cell death. Thus, karyotype analysis demonstrated that 3 out of 20 XLF-null metaphases showed some form of gross chromosomal abnormality, including the loss of whole chromosomes (Supplemental Fig. 3). This 15% rate of abnormalities is slightly higher than the 9.7% rate of spontaneous abnormalities detected in the parental cell line [69]. If the increased genomic instability is indeed responsible for the reduced growth of XLF-mutant human cells, it provides a reasonable mechanism for the developmental delay and microcephaly associated with XLF patients [35]. A similar hypothesis was proposed based upon XLF patient cells’ impaired responses to agents that induce replication stress [82]. If XLF does play a role in ameliorating the DNA damage associated with endogenous DNA replication stress, then the absence of XLF should result in increased replication-linked damage [82], higher genomic instability (this study) and could explain the cellular phenotypes of XLF patients. Superficially inconsistent with this observation is the increased gene conversion HR activity observed in XLF-null cells (Fig. 6B), which should presumably protect against replication stress. We note however, that a similar increase in SSA, a non-conservative HR subpathway, was also observed in XLF-null cells (Fig. 6B). Thus, any benefit that XLF-null cells experience due to enhanced HR, is likely offset by the lack of XLF-mediated C-NHEJ and the increase in SSA.

Immortalized fibroblasts of XLF patients or human cells in which XLF had been knocked down by RNA interference showed increased sensitivity to IR and to the DSB-inducing agent bleomycin, as well as impaired end ligation of restriction enzyme-induced DSBs in vivo and in vitro in comparison to XLF-proficient cells [34, 35]. The targeted disruption of XLF in HCT116 cells completely phenocopied these features. Thus, XLF-null HCT116 cells were very IR and etoposide (a strong radiomimetic agent) sensitive (Fig. 3). Similarly, XLF-null HCT116 cells were reduced, by at least an order of magnitude, for plasmid end-joining in vivo (Fig. 4). All of these phenotypes could be fully rescued by the re-introduction of a wild-type XLF cDNA demonstrating that the phenotypes were due to the absence of XLF. It is important to note that while total end-joining activity was severely reduced (Fig. 4), that the level of A-NHEJ was unaltered (Fig. 6) even though A-NHEJ was the only end joining activity detectable in the cells (Fig. 5). These data demonstrate that for end joining, XLF participates exclusively in CNHEJ.

The magnitude of the IR-sensitivity and the defects in DNA DSB repair were nearly identical to those observed for cells deficient in other core C-NHEJ factors, LIGIV and DNA-PKcs [52, 69, 81]. Nonetheless, XLF-null cells are not completely devoid of DNA DSB repair activity and are even slightly enhanced for HR (Fig. 6B). The residual end joining activity that such cells have, however, is utterly dependent upon microhomology usage, which is facilitated by A-NHEJ (Fig. 5C). In this regard, XLF-null cells are similar to LIGIV-null and DNA-PKcs-null cells, but strikingly different from Ku-deficient cells, which have highly elevated levels of HR [68] and A-NHEJ activity [52]. Indeed, the data presented here for XLF-null cells strongly supports the hypothesis that Ku is the major C-NHEJ factor that regulates DNA pathway choice in human cells [52].

Patients with mutations in XLF are immunodeficient [35]. The immunological defects are due to T and B lymphocytopenia and hypogammaglobulinemia of serum IgG and IgA antibodies. Mechanistically, these deficits reflect a role of XLF in V(D)J and class switch recombination. Thus, immortalized patient fibroblasts are severely impaired in forming V(D)J coding and signal junctions using transient, extrachromosomal assays [35, 42, 83]. Similarly, murine XLF-null ES cells were severely impaired for the ability to form V(D)J coding and signal joins when assayed using the same extrachromosomal system [51]. Our data confirm these findings. Thus, our XLF-null HCT116 cells are 50-fold reduced for both coding and signal joins (Table 1). Surprisingly, the mice derived from the murine XLF-null ES cell lines were only slightly immune deficient and showed robust chromosomal V(D)J proficiency, which the authors suggested could be due to a whole animal lymphocyte-specific compensatory mechanism for XLF function [27]. This hypothesis has recently been validated by studies that demonstrated that the coincident loss of ATM [29], 53BP1 [30, 31], or DNA-PKcs [32] with the absence of XLF uncovers a profound chromosomal V(D)J defect. The mechanistic reasons why the loss of genes as disparate as ATM, 53BP1 and DNA-PKcs would uncover a similar synthetic deficiency and why an XLF deficiency is so much more severe in ES cell lines versus whole animals is unclear and warrants more investigation. It is interesting to note, however, that ATM, 53BP1 and DNA-PKcs, while not normally viewed as canonical HR factors have nonetheless been implicated in co-regulating either HR {ATM and DNA-PKcs, [84, 85]} or end resection {53BP1, [86]}, which is required for HR. Thus, these mutations may, albeit indirectly, reduce the enhanced levels of HR in XLF-null cells and generate a more severe phenotype. Finally, it should be noted, however, that — from a strictly technical point of view — the construction in the XLF-null HCT116 cell line of double knockouts for ATM, 53BP1, DNA-PKcs or just about any other synthetic candidate gene to explore these issues is quite feasible [81].

One of the most surprising findings of this study was the robust complementation observed for the L115A and L179A XLF cDNAs. First, not all of the mutant cDNAs provided complementation. Indeed, the three patient-derived mutations (R178X, C123R and R57G) that were analyzed were completely incapable of restoring IR-resistance, DNA DSB repair or V(D)J recombination activity (data not shown), observations which are consistent with work from other laboratories [39, 41, 43]. In contrast, the L115A and L179A XLF alterations, which were non-patient, site-directed mutations that we intentionally constructed, were proficient for DNA DSB repair (Figs. 4 and 5) and V(D)J recombination (Table 1). The functionality of the L115A construct was particularly unexpected. L115 has been predicted to be part of a hydrophobic “leucine lock” [43] necessary for a XLF:XRCC4 filament and the mutation of L115 to L115D has been documented to disrupt the interaction of XLF with XRCC4 and negate XLF's repair and V(D)J recombination activity [42-44]. One explanation is that the L115D mutation may simply be much more destabilizing for a hydrophobic interaction than L115A. In this case, L115A may be able to provide sufficient interaction with XRCC4 to provide function to the putative XLF:XRCC4 filament. This explanation is consistent with recent work from the Meek laboratory, which demonstrated, using mutations in XRCC4's XLF-interaction domain, that the loss of XRCC4:XLF interactions resulted in an asymmetric defect in V(D)J recombination, with coding junction formation being preferentially deleteriously affected [23]. Since we observed no such V(D)J recombination defect (Table 1), we infer that XLF L115A is likely capable of interacting with XRCC4. The strongest data against this argument are observations by Andres et al. [38], who demonstrated in vitro using purified, epitope-tagged proteins that XLF L115A no longer interacted with XRCC4 and that XLF L115A and the L179A mutant were incapable of performing an in vitro end-joining reaction. Since both of our DNA DSB repair assays and the V(D)J recombination assay were performed in vivo, we suggest that in vitro, some necessary factor(s) were absent, which are important for XLF function — as the recent synthetic deficiency experiments imply [29-32].

In conclusion, this is the first report of a targeted XLF inactivation in a human somatic cell line. Our characterizations of XLF-deficient cell line suggests that this cell line should be very useful for a structure-function analysis of XLF and for probing the mechanism of C-NHEJ.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

➢ We used rAAV-mediated gene targeting to inactivate the XLF gene in human cells.

➢ XLF-null cells were very sensitive to DNA damaging agents.

➢ XLF-null cells were extremely deficient for DNA end joining.

➢ XLF-null cells were defective for extrachromosomal V(D)J recombination.

➢ Complementation analyses yielded insight into the XLF structure/function.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Drs. S. Jackson (Cambridge University, UK), V. Gorbunova (University of Rochester, NY), G. Iliakis (University of Duisburg-Essen Medical School, Germany), M. Jasin (Sloan Kettering, NY), J. Stark (City of Hope, CA) and D. van Gent (Erasmus University, Netherlands) and members of their laboratories who were extremely generous with their reagents and advice. We thank Dr. A.-K. Bielinsky for her careful reading of the manuscript and helpful comments. We would like to acknowledge the assistance of the Flow Cytometry Core Facility of the Masonic Cancer Center, a comprehensive cancer center designated by the National Cancer Institute, supported in part by P30 CA77598. These studies were supported in part by a National Institutes of Health grant GM088351 and a National Cancer Institute grant CA154461 to EAH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement. EAH declares that he is a member of the scientific advisory board of Horizon Discovery, Ltd., a company that specializes in rAAV-mediated gene targeting technology.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hakem R. DNA-damage repair; the good, the bad, and the ugly. Embo J. 2008;27:589–605. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boboila C, Alt FW, Schwer B. Classical and alternative end-joining pathways for repair of lymphocyte-specific and general DNA double-strand breaks. Adv Immunol. 2012;116:1–49. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394300-2.00001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hartlerode AJ, Scully R. Mechanisms of double-strand break repair in somatic mammalian cells. Biochem J. 2009;423:157–168. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kass EM, Jasin M. Collaboration and competition between DNA double-strand break repair pathways. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:3703–3708. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.07.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee SE, Mitchell RA, Cheng A, Hendrickson EA. Evidence for DNA-PK-dependent and -independent DNA double-strand break repair pathways in mammalian cells as a function of the cell cycle. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1425–1433. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rothkamm K, Kruger I, Thompson LH, Lobrich M. Pathways of DNA double-strand break repair during the mammalian cell cycle. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5706–5715. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.16.5706-5715.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dobbs TA, Tainer JA, Lees-Miller SP. A structural model for regulation of NHEJ by DNA-PKcs autophosphorylation. DNA Repair (Amst) 2010;9:1307–1314. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lieber MR. The mechanism of double-strand DNA break repair by the nonhomologous DNA end-joining pathway. Annu Rev Biochem. 2010;79:181–211. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.052308.093131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nussenzweig A, Nussenzweig MC. A backup DNA repair pathway moves to the forefront. Cell. 2007;131:223–225. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mladenov E, Iliakis G. Induction and repair of DNA double strand breaks: the increasing spectrum of non-homologous end joining pathways. Mutat Res. 2011;711:61–72. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akopiants K, Zhou RZ, Mohapatra S, Valerie K, Lees-Miller SP, Lee KJ, Chen DJ, Revy P, de Villartay JP, Povirk LF. Requirement for XLF/Cernunnos in alignment-based gap filling by DNA polymerases lambda and mu for nonhomologous end joining in human whole-cell extracts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:4055–4062. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramsden DA, Asagoshi K. DNA polymerases in nonhomologous end joining: are there any benefits to standing out from the crowd? Environ Mol Mutagen. 2012;53:741–751. doi: 10.1002/em.21725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yano K, Chen DJ. Live cell imaging of XLF and XRCC4 reveals a novel view of protein assembly in the non-homologous end-joining pathway. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:1321–1325. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.10.5898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yano K, Morotomi-Yano K, Lee KJ, Chen DJ. Functional significance of the interaction with Ku in DNA double-strand break recognition of XLF. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:841–846. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reynolds P, Anderson JA, Harper JV, Hill MA, Botchway SW, Parker AW, O'Neill P. The dynamics of Ku70/80 and DNA-PKcs at DSBs induced by ionizing radiation is dependent on the complexity of damage. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:10821–10831. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moshous D, Callebaut I, de Chasseval R, Corneo B, Cavazzana-Calvo M, Le Deist F, Tezcan I, Sanal O, Bertrand Y, Philippe N, Fischer A, de Villartay JP. Artemis, a novel DNA double-strand break repair/V(D)J recombination protein, is mutated in human severe combined immune deficiency. Cell. 2001;105:177–186. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00309-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma Y, Pannicke U, Schwarz K, Lieber MR. Hairpin opening and overhang processing by an Artemis/DNA-dependent protein kinase complex in nonhomologous end joining and V(D)J recombination. Cell. 2002;108:781–794. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00671-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rooney S, Sekiguchi J, Zhu C, Cheng HL, Manis J, Whitlow S, DeVido J, Foy D, Chaudhuri J, Lombard D, Alt FW. Leaky Scid phenotype associated with defective V(D)J coding end processing in Artemis-deficient mice. Mol Cell. 2002;10:1379–1390. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00755-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teo SH, Jackson SP. Identification of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA ligase IV: involvement in DNA double-strand break repair. Embo J. 1997;16:4788–4795. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.15.4788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson TE, Grawunder U, Lieber MR. Yeast DNA ligase IV mediates nonhomologous DNA end joining. Nature. 1997;388:495–498. doi: 10.1038/41365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grawunder U, Zimmer D, Fugmann S, Schwarz K, Lieber MR. DNA ligase IV is essential for V(D)J recombination and DNA double-strand break repair in human precursor lymphocytes. Mol Cell. 1998;2:477–484. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80147-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andres SN, Vergnes A, Ristic D, Wyman C, Modesti M, Junop M. A human XRCC4-XLF complex bridges DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:1868–1878. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roy S, Andres SN, Vergnes A, Neal JA, Xu Y, Yu Y, Lees-Miller SP, Junop M, Modesti M, Meek K. XRCC4's interaction with XLF is required for coding (but not signal) end joining. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:1684–1694. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cottarel J, Frit P, Bombarde O, Salles B, Negrel A, Bernard S, Jeggo PA, Lieber MR, Modesti M, Calsou P. A noncatalytic function of the ligation complex during nonhomologous end joining. J Cell Biol. 2013;200:173–186. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201203128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Helmink BA, Sleckman BP. The response to and repair of RAG-mediated DNA double-strand breaks. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:175–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malu S, Malshetty V, Francis D, Cortes P. Role of non-homologous end joining in V(D)J recombination. Immunol Res. 2012;54:233–246. doi: 10.1007/s12026-012-8329-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li G, Alt FW, Cheng HL, Brush JW, Goff PH, Murphy MM, Franco S, Zhang Y, Zha S. Lymphocyte-specific compensation for XLF/cernunnos end-joining functions in V(D)J recombination. Mol Cell. 2008;31:631–640. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yano K, Morotomi-Yano K, Akiyama H. Cernunnos/XLF: a new player in DNA double-strand break repair. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:1237–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zha S, Guo C, Boboila C, Oksenych V, Cheng HL, Zhang Y, Wesemann DR, Yuen G, Patel H, Goff PH, Dubois RL, Alt FW. ATM damage response and XLF repair factor are functionally redundant in joining DNA breaks. Nature. 2011;469:250–254. doi: 10.1038/nature09604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu X, Jiang W, Dubois RL, Yamamoto K, Wolner Z, Zha S. Overlapping functions between XLF repair protein and 53BP1 DNA damage response factor in end joining and lymphocyte development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:3903–3908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120160109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oksenych V, Alt FW, Kumar V, Schwer B, Wesemann DR, Hansen E, Patel H, Su A, Guo C. Functional redundancy between repair factor XLF and damage response mediator 53BP1 in V(D)J recombination and DNA repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:2455–2460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121458109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oksenych V, Kumar V, Liu X, Guo C, Schwer B, Zha S, Alt FW. Functional redundancy between the XLF and DNA-PKcs DNA repair factors in V(D)J recombination and nonhomologous DNA end joining. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:2234–2239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222573110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vera G, Rivera-Munoz P, Abramowski V, Malivert L, Lim A, Bole-Feysot C, Martin C, Florkin B, Latour S, Revy P, de Villartay JP. Cernunnos deficiency reduces thymocyte life span and alters the T cell repertoire in mice and humans. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33:701–711. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01057-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahnesorg P, Smith P, Jackson SP. XLF interacts with the XRCC4-DNA ligase IV complex to promote DNA nonhomologous end-joining. Cell. 2006;124:301–313. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buck D, Malivert L, de Chasseval R, Barraud A, Fondaneche MC, Sanal O, Plebani A, Stephan JL, Hufnagel M, le Deist F, Fischer A, Durandy A, de Villartay JP, Revy P. Cernunnos, a novel nonhomologous end-joining factor, is mutated in human immunodeficiency with microcephaly. Cell. 2006;124:287–299. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Callebaut I, Malivert L, Fischer A, Mornon JP, Revy P, de Villartay JP. Cernunnos interacts with the XRCC4 x DNA-ligase IV complex and is homologous to the yeast nonhomologous end-joining factor Nej1. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:13857–13860. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500473200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hentges P, Ahnesorg P, Pitcher RS, Bruce CK, Kysela B, Green AJ, Bianchi J, Wilson TE, Jackson SP, Doherty AJ. Evolutionary and functional conservation of the DNA non-homologous end-joining protein, XLF/Cernunnos. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:37517–37526. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608727200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]