Abstract

Objective

In São Paolo, Brazil, patients can appeal to the courts, registering law suits against the government claiming the need for biological agents for treatment of psoriasis. If the lawsuits are successful, which is usually the case, the government then pays for the biologic agent. The extent to which the management of such patients, after gaining access to government payment for their biologic agents, adheres to authoritative guidelines, is uncertain.

Methods

We identified patients through records of the State Health Secretariat of São Paulo from 2004 to 2011. We consulted guidelines from five countries and chose as standards only those recommendations that the guidelines uniformly endorsed. Pharmacy records provided data regarding biological use. Guidelines not only recommended biological agents only in patients with severe psoriasis who had failed to respond to topical and systemic therapies (eg, ciclosporin and methotrexate) but also yearly monitoring of blood counts and liver function.

Results

Of 218 patients identified in the database, 3 did not meet eligibility criteria and 12 declined participation. Of the 203 patients interviewed, 91 were still using biological medicine; we established adherence to laboratory monitoring in these patients. In the total sample, management failed to meet standards of prior use of topical and systemic medication in 169 (83.2%) patients. Of the 91 patients using biological medicine at the time of the survey, 23 (25.2%) did not undergo appropriate laboratory tests.

Conclusions

Important discrepancies exist between clinical practice and the recommendations of guidelines in the management of plaintiffs using biological drugs to treat psoriasis.

Keywords: Clinical Pharmacology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We obtained a complete list of all individuals who succeeded in obtaining government payment for biological agents for psoriasis.

We obtained pharmacy records of medication use and corroborating information from patient interviews.

A duplicate review of interview recordings ensured accurate information.

Our study includes the possibility that the patients’ memory of prior medication use may not have been accurate.

The interviews, however, included detailed descriptions of medications, including topical agents, and the patients’ failure to remember the use of topical agents may be implausible.

We did not obtain corroboration of reports of adverse effects or apparent improvement with the biological agents, and these data are therefore suspect.

We did not study the management of patients who have received biologics through the usual healthcare system.

Introduction

Psoriasis, a chronic, inflammatory immune-mediated skin disease that predominantly affects the skin and joints, occurs in between 1.5% and 3% of the population.1 Onset may occur at any age but peaks in the second and third decades. The severity of psoriasis varies widely, and its course is characterised by relapses and remissions, though it usually persists throughout life. Its negative impact on health-related quality of life is similar to that of ischaemic heart disease, diabetes, depression and cancer.2

The significant reduction in quality of life and the psychosocial disability suffered by patients highlight the need for prompt, effective treatment and long-term disease control.3 4 In mild psoriasis, topical treatment can be effective.5 Those with moderate-to-severe disease often require treatment with phototherapy and systemic treatment.6 When systemic traditional treatment with ciclosporin, methotrexate or acitretin fails (non-biological systemic agents or N-BISYS), systemic biological therapies such as the tumour necrosis factor (TNF) antagonists' adalimumab, etanercept and infliximab, and the monoclonal antibody ustekinumab, which targets interleukin 12 (IL-12) and IL-23, become options.6–9

Owing to their immunosuppressive activity, some anti-TNFs have been associated with a small increased risk of infection in patients with psoriasis,10 and studies of TNF antagonist use in other disease areas have raised concerns over a potential link to cardiovascular side effects, malignancies and neurological defects.10–12 Guidelines uniformly recommend at least one annual patient review to check for infections, malignancies and other adverse effects of biological agents.

In Brazil, patients can, once they are prescribed by a clinician, go to the courts to force the state to pay for expensive medication such as biologics. Court decisions may not be consistent with optimal standards of care in terms of patients who are appropriate for use of biologics. Furthermore, once patients receive biologics through court decisions, subsequent management may not be optimal.

The objective of this study was to identify standards of management of psoriasis common to major international guidelines and to evaluate the extent to which Brazilian physicians who prescribed biologics that courts approved on the basis of lawsuits adhered to these standards.

Methods

The protocol (cross-sectional design) was authorised by the São Paulo State Department of Health (SES-SP).

Choice of guidelines and guideline recommendations

We consulted guidelines from the following countries: the UK,13 Germany,7 Brazil,9 the USA,14 Canada15 and Europe.16 We used both national guidelines (National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN))5 6 and specialty society guidelines. We reviewed all recommendations in each guideline and chose as standards only those recommendations that for prior treatment were uniformly endorsed across all guidelines and for monitoring were endorsed by four of the five guidelines.

Recommendations uniformly endorsed by every guideline5–9 specified that biologics should only be used in patients with severe psoriasis who had failed to respond to, have a contraindication to, or are intolerant of topical therapies, and at least one systemic therapy (eg, ciclosporin or methotrexate). Guidelines also uniformly recommend at least one annual patient review to check for infections, malignancies and other adverse effects of biological agents and also to evaluate control of psoriasis. Guidelines specified that the review should include monitoring of complete blood cell count and liver function tests.

Eligibility criteria

Patients were eligible if they had, through lawsuits filed against the state of São Paulo in the period 2004–2010, gained access to biologics for treatment of psoriasis. All patients gave informed consent.

Identification of patients and collection of patient data

In order to identify eligible patients, two researchers abstracted data from all the dispensing orders in the database for psoriasis—identified by International Classification of Diseases (ICD) code L40—originating from lawsuits from 2004 to 2010 including the name, address and telephone number, gender, age, healthcare provider, whether that provider worked in the public or private system, type of biologics dispensed and diagnoses. We excluded patients with psoriatic arthritis.

We contacted patients with psoriasis by telephone, and if they proved eligible and agreed to participate in the study, conducted interviews. The interviews were conducted by telephone using computer-assisted telephonic interviews technology with a microcomputer handset with headphones. This system allows the recording and monitoring of the duration of the conversation.17 18 Research staff working in pairs independently recorded data from the interviews, with discrepancies resolved by the principal investigator (LCL).

The interview schedule was developed in consultation with a local dermatologist (see online supplementary appendix) after consideration of the recommendations consistent across guidelines. An electronic form was developed in Microsoft Office Access based on the instrument developed for the interviews. To address the items listed in the instrument, 16 screens were designed to record the data from the interviews. Each interviewer received training on the use of language related to each question in the interview schedule. The questionnaire included the following: what drugs the patient was using for the treatment of psoriasis prior to the court judgement, the time of diagnosis of psoriasis, comorbidities and whether patients received at least an annual review. For patients still taking biologics, we determined if they had received a medical consultation in the previous year and what tests had been undertaken in the previous year. In Brazil, patients receive records of all their laboratory tests and typically retain these records indefinitely; all patients still receiving biologics reported that they had retained records of all of the laboratory tests undertaken during the previous year.

Patients’ reports of the period in which they used the biologics were cross-checked with data obtained from pharmacy records and from legal records from lawsuits. Legal records from lawsuits gave us the name of patients, name of the drugs obtained through the lawsuit, whether the prescription came from private or public insurance, sex, diagnostic and age of patients. If we found a discrepancy among the three sources of information, we considered the information from pharmacy records definitive. Thus, definitive information about the name of the biologics and the duration of use of the biologics was obtained from the pharmacy, and definitive information of the time of diagnosis, use of previous medicines and laboratory results was obtained from the patient. We considered guideline adherence adequate when court decisions and subsequent clinical care had adhered to all recommendations from guidelines.

In the interviews, we also asked patients about their adverse effects and whether these led to discontinuing medications and their perception of the effectiveness of the biological agents.

Results

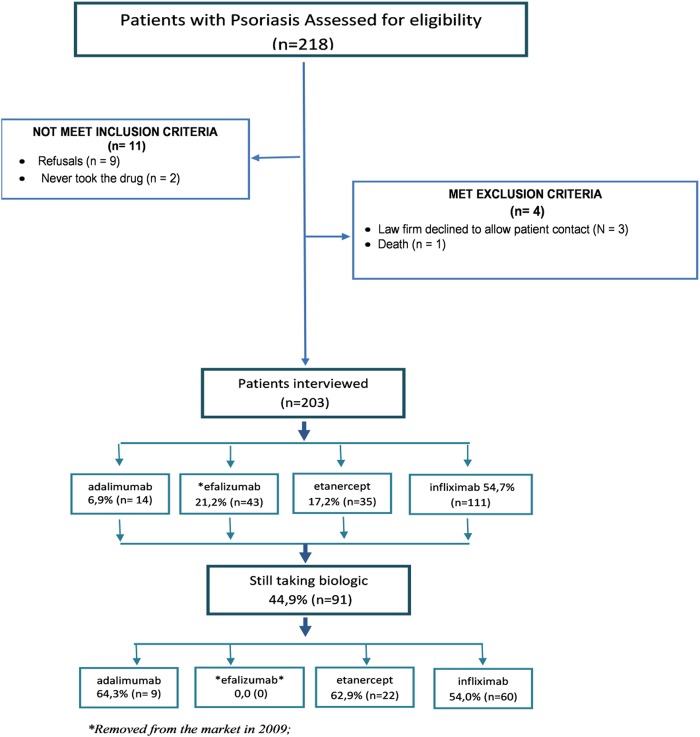

We reviewed 25 184 lawsuits that had succeeded in obtaining medicines, dietary supplements or other health products, such as orthotics and prosthetics, in which the claims were made and registered in the Public Finance Courts Capital during the years 2004 to 2010. Of 218 patients identified as using biologics for psoriasis, in 3 the contact information was a law office that did not allow us to contact patients, 1 patient had died, 2 had never used the biologics that was mandated by the court decision and 9 refused the interview. We interviewed 203 patients, of whom 91 (44.8%) were still using a biological agent (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the steps of the sample composition of a plaintiff included in the study.

Eligible patients received one of four biological drugs: adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab and efalizumab. Table 1 presents the sociodemographic and medical health characteristics of the 203 eligible patients as well as the duration the patients used the biological agents granted payment by the courts. Over a third of the patients used the biological agents for less than a year, and over 50% used them for 1–3 years.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of plaintiffs with psoriasis

| Patients N=203 | Per cent | |

|---|---|---|

| City of residence | ||

| São Paulo | 122 | 60 |

| Other | 81 | 40 |

| Healthcare | ||

| Private | 141 | 69.5 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 129 | 63.5 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 19–59 | 156 | 76.9 |

| ≥60 | 47 | 23.1 |

| Mean±SD | 48.9±13.7 | |

| Time of diagnosis (years previously) | ||

| 6 or more | 177 | 84.9 |

| 2–5 | 25 | 10.2 |

| ≤1 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Comorbidities | ||

| None | 128 | 63 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 26 | 12.8 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 12 | 5.9 |

| Others | 37 | 18.2 |

| Duration of use of biologics (months) | ||

| 12 or less | 69 | 34.0 |

| 13–36 | 110 | 54.2 |

| 37–72 | 24 | 11.8 |

Table 2 presents the use of non-biological medications prior to the lawsuit decision to pay for the use of a biological agent. Over 20% of the patients had not used any conventional interventions—topical, light or systemic agents—for psoriasis prior to launching their lawsuit for use of biological agents. Topical agents were used very infrequently—in only approximately 16% of patients. Similarly, phototherapy was infrequently used—in 36.9% of the patients. Approximately 71% of patients had used N-BISYS therapy before their lawsuit. No patients had contraindications, or were using drugs with problematic interactions, that would have prevented the use of all recommended systemic agents (ciclosporin, methotrexate and acitretin). Given that guideline adherence requires the use of topical and systematic therapy before beginning biologics use, only 34 patients (16.7%) met the guideline requirements.

Table 2.

Treatment prior to initiating lawsuit for biologics use

| Adalimumab 14 (6.9) |

Efalizumab 43 (21.2) |

Etanercept 35 (17.2) |

Infliximab 111 (54.7) |

Total 203 (100) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Therapies | |||||

| None | 1 (7.1) | 12 (27.9) | 6 (17.1) | 25 (22.5) | 44 (21.7) |

| Only topical | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Only phototherapy | 0 (0.0) | 5 (11.6) | 3 (8.7) | 7 (6.3) | 15 (7.4) |

| Only N-BIOSYS* | 10 (71.4) | 2 (4.6) | 12 (34.3) | 36 (32.4) | 60 (29.6) |

| Combination of therapies prior to the use of biologics, n (%) | |||||

| Topical+phototherapy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Topical+N-BIOSYS* | 1 (7.1) | 4 (9.3) | 3 (8.6) | 16 (14.4) | 24 (11.8) |

| Phototherapy+N-BIOSYS* | 2 (14.3) | 18 (41.8) | 8 (22.8) | 22 (19.8) | 50 (24.6) |

| Topical+phototherapy+N-BIOSYS* | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.6) | 3 (8.6) | 5 (4.5) | 10 (4.9) |

| Recommended use of biological agents according to guidelines (7–10), n (%) | |||||

| Topical+N-BIOSYS | 1 (7.1) | 6 (14.0) | 6 (17.1) | 21 (18.9) | 34 (16.7) |

*Acitretin, methotrexate and ciclosporin.

N-BIOSYS, non-biological systemic.

Table 3 presents the findings in the 91 patients who were still using a biological agent at the time of the interview. The pattern of prior use was similar to that of the overall group, with 19.3% of patients having used a topical agent and systemic therapy. All patients had visited a doctor at least once a year, but 25.2% did not undergo the recommended laboratory tests (blood count, differential count and liver function; table 3). Thus, only 14.2% of the patients met the guideline criteria for the use of prior agents and appropriate monitoring.

Table 3.

Clinical follow-up and outcome judgement in patient with psoriasis still taking biological agents

| Outcomes | Adalimumab 9 (9.9) |

Etanercept 22 (62.9) |

Infliximab 60 (54.0) |

Total 91(100) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual review | ||||

| A—consults* | 9 (100) | 22 (100) | 60 (100) | 91 (100) |

| B—laboratorial examinations† | 7 (77.8) | 15 (68.2) | 46 (76.7) | 68 (74.8) |

| Clinical monitoring adequate | ||||

| C—A+B | 7 (77.8) | 15 (68.9) | 46 (76.4) | 68 (74.8) |

| Therapies | ||||

| None | 0 (0.0) | 3 (13.6) | 14 (23.3) | 17 (18.7) |

| Only topical | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Only phototherapy | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.5) | 4 (6.7) | 5 (5.5) |

| Only N-BIOSYS‡ | 7 (77.8) | 9 (40.9) | 18 (30.0) | 34 (37.4) |

| Combination of therapies prior to the use of biologics, n (%) | ||||

| Topical +phototherapy | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| D—topical+N-BIOSYS‡ | 1 (11.1) | 3 (13.6) | 8 (13.3) | 12 (13.2) |

| Phototherapy+N-BIOSYS‡ | 1 (11.1) | 4 (18.2) | 13 (21.7) | 18 (19.8) |

| E—topical+phototherapy+N-BIOSYS | 0 (0.0) | 2 (9.1) | 3 (5.0) | 5 (5.5) |

| F—recommended use of biological agents according to guidelines | ||||

| D+E | 1 (11.1) | 5 (22.7) | 11 (18.3) | 17 (19.3) |

| Adherence of guideline | ||||

| Prior drugs and monitoring (C+D) | 1 (11.1) | 3 (13.6) | 9 (15.0) | 13 (14.2) |

*At least one annual medical consult; blood differential (complete blood cell count), liver function tests.

†Blood differential (complete blood cell count), liver function tests.

‡Use of biological agent after treatment with topic and one systemic non-biological agent.

Of the 203 respondents, 134 (66%) perceived that they experienced important improvement with the use of biological agents, although 20 patients reported a deterioration that they attributed to the use of biological agents. Adverse effects severe enough to discontinue medication were reported by 23 patients (11.3%).

Discussion

Main findings

The key finding of this investigation is that very few patients obtaining payment for use of biological agents for treatment of psoriasis had met the guideline criteria for use of non-biological therapy prior to the start of expensive and potentially toxic biological agents (tables 2 and 3). In particular, topical agents had seldom been used in these patients. In addition, approximately 30% had not used any N-BISYS agents. Further, of those still using biological agents, approximately 25% had not undergone the recommended laboratory investigations in the prior year. Thus, complete adherence to guideline recommendations for prior therapy occurred in only 16.7% of patients and complete guideline adherence including prior therapy and laboratory monitoring in only 14.2% of those still using biological agents (tables 2 and 3).

The patients in this sample did not have the New York Heart Association class III/IV (NYHA III/IV) heart disease, a potential contraindication for TNFs (table 1). However, the prevalent comorbidities detected in these patients involve the cardiovascular system, the main contraindication to the use of biological drugs (22). Thus, the pattern of comorbidity raises further concern regarding the use of biological agents without, in approximately 30%, the prior use of non-biological immunosuppressant therapy.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The strengths of this study include our ability to obtain a complete list of all individuals who succeeded in obtaining government payment for biological agents for psoriasis. We were able to contact and obtain consent from 203 or 218 potentially eligible patients. We obtained pharmacy records of medication use and corroborating information from patient interviews. A duplicate review of interview recordings ensured accurate information. We surveyed a number of key guidelines including public agencies and specialty societies from a number of countries and used as criteria only recommendations included in all the guidelines.

The possible limitations in our study include the possibility that the patients’ memory of prior medication use may not have been accurate. In particular, approximately 20% of patients reported no prior topical, phototherapy or system therapy prior to the use of biological agents. The interviews, however, included detailed descriptions of medications, including topical agents, and patients’ failure to remember the use of topical agents may be implausible. We did not obtain corroboration of reports of adverse effects or apparent improvement with the biological agents, and these data are therefore suspect.

Also, the fact that we did not study the management of patients who have received biologics through the usual healthcare system (ie, without recourse to the courts) represents another limitation of the study. Thus, our study provides only indirect evidence regarding how these patients are managed within the “Brazilian public health system”.

Relation to evidence and recommendations

The guidelines we reviewed were consistent in their recommendation that patients with severe psoriasis who do not respond or have a contraindication to or are intolerant to topical therapy and systemic therapy with immunosuppressants, including ciclosporin and methotrexate, are candidates for biological therapies.5–8 15 The guidelines also recommended phototherapy as an alternative. Despite evidence of the cost-effectiveness of phototherapy in moderate-to-severe psoriasis,19 20 the guidelines did not insist on a trial of phototherapy before treatment with biological agents.

Biological agents may be associated with serious adverse effects, including an increase in the risk of malignancies, opportunistic fungal infection and lymphoma.10–12 Of particular concern is the use of drugs over the long term. Currently, the data available are insufficient to draw clear and reliable conclusions about either the efficacy of long-term treatments or the frequency of adverse effects over the long term.21–23 The majority of plaintiffs are using biologics for over a year, and more than 10% for over 3 years, raising another possible concern.

Implications

Biological agents are not included in Brazilian official guidelines to treat psoriasis. Therefore, access to this medication is largely from prescriptions by private practitioners. Having obtained a prescription for a biological agent, a Brazilian citizen can launch legal action to have the government pay for the high-cost medication. It is perhaps ironic that despite the last report of the Brazilian health assessment technology committee (Conitec) choosing to not recommend (1) the use of these biological drugs in the treatment of psoriasis primarily because of safety concerns, judicial decisions in favour of their use requires the public health system to provide funding.

One could argue that it may be unreasonable to ask judges to be aware of medical guidelines, particularly those arising from other jurisdictions. A proposed solution to this problem would be to provide the court with high-quality technical analyses. In this case, experts in psoriasis aware of the guidelines would provide the analyses. So far, such analyses are unavailable.24–26 Our results emphasise the need for technical analyses to guide court decisions, ideally considering two independent opinions.

Irrespective of issues of whether governments should fund biologics in psoriasis at all, clinical practice and judicial decisions should be consistent with highly credible international guidelines. Our results show an important gap between clinical practice and judicial decisions in treatments prescribed to plaintiffs demanding medicines for psoriasis in São Paulo, Brazil and corresponding guidelines.

Explanations for inappropriate practice include inadequate training and knowledge of the physicians who prescribe the drugs.27 28 Another possibility is that incentives from the pharmaceutical industry are influencing the prescription of biological agents in psoriasis. Whatever the reason, our findings demonstrate that the court system is not functioning well. This is not necessarily the fault of the judges, but of a system that does not ensure that judges have appropriate access to expert guidance. An independent review by disinterested experts would have led the court to insist on appropriate prior treatment before considering biological agents. The health system also appears to be negligent in not ensuring optimal follow-up to patients who receive payment for their drugs from the government. The responsibility for informing practitioners of optimal management could rest with the pharmaceutical industry, the national dermatologic society or the government.

Our results suggest that changes at both the level of clinical practice and the function of the judicial system are urgently needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the FAPESP (Foundation for Research Support of the State of São Paulo) process number 2009/0530841, at UNISO (University of Sorocaba) for their support of this project, and pharmaceutics Livia Marengo and Andressa Marcondes and Larissa Colombo Marcondes, Bruna Cipriano that have helped use doing part of extraction and interview of patients. They also thank CODES SES-SP (Strategic Coordination Demands of Ministry of Health of São Paulo) for their cooperation in giving them the data from the database and helping them find the lawsuit papers in their files.

Footnotes

Collaborators: Larissa Zavatini Marcondes, Andressa Z Colombo Marcondes, Bruna Cipriano, Livia L Marengo.

Contributors: LCL, IAdC, SB-F and CGSO-d-C had the original idea and they developed the study protocol. GG, LCL, MSdNS and CGSO-d-C performed data analysis and drafted the manuscript. MSdNS, FdSDF, SB-F, MCdC and IAdC contributed to data collection. All authors contributed to the preparation of the manuscript and read and approved the final version.

Funding: This work was supported by the FAPESP—Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa—process N. 2009/53084-1.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This study is part of the PSAR Project approved by the ethics committee for clinical research of University of Sorocaba on 17 August 2009, with protocol number 011/2009.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Zachariae H. Prevalence of joint disease in patients with psoriasis: implications for therapy. Am J Clin Dermatol 2003;4:441–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rapp SR, Feldman SR, Exum ML, et al. Psoriasis causes as much disability as other major medical diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol 1999;41(3 Pt 1):401–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Menter A, Griffiths CE. Current and future management of psoriasis. Lancet 2007;370:272–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith CH, Barker JN. Psoriasis and its management. BMJ 2006;333:380–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.NICE Psoriasis: the assessment and management of psoriasis. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence—Clinical Guidelines, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 6.SIGN. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network Diagnosis and management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in adults. A national clinical guideline. Vol. 121 Edinburgh (Scotland): Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), 2010:65 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nast A, Boehncke WH, Mrowietz U, et al. S3—guidelines on the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris (English version). Update. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2012;10(Suppl 2):S1–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith CH, Anstey AV, Barker JN, et al. British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for biologic interventions for psoriasis 2009. Br J Dermatol 2009;161:987–1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.SBD Consenso Brasileiro de Psoríase 2012—Guias de avaliação e tratamento Sociedade Brasileira de Dermatologia. 2nd edn. Rio de Janeiro: Sociedade Brasileira de Dermatologia, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dommasch ED, Abuabara K, Shin DB, et al. The risk of infection and malignancy with tumor necrosis factor antagonists in adults with psoriatic disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011;64:1035–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bongartz T, Sutton AJ, Sweeting MJ, et al. Anti-TNF antibody therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of serious infections and malignancies: systematic review and meta-analysis of rare harmful effects in randomized controlled trials. JAMA 2006;295:2275–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh JA, Wells GA, Christensen R, et al. Adverse effects of biologics: a network meta-analysis and Cochrane overview. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011(2):CD008794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Psoriasis: the assessment and management of psoriasis. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence—Clinical Guidelines, 2012

- 14.Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis Section 1. Overview of psoriasis and guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with biologics. American Academy of Dermatology, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papp K, Gulliver W, Lynde C, et al. Canadian guidelines for the management of plaque psoriasis: overview. J Cutan Med Surg 2011;15:210–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pathirana D, Ormerod AD, Saiag P, et al. European S3-guidelines on the systemic treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2009;23(Suppl 2):1–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.GRUPO. IBOPE INTELIGÊNCIA Coleta de dados. Diversos métodos para atender à sua demanda. Publicação em 28/04/2009. http://www.ibope.com.br (Acesso em 28 ju. 2011) 2011

- 18.LIPE. PESQUISAS Dúvidas frequentes: o que é CATI? Disponível em http://www.lipe.com.br . (Acesso em 28 jul. 2011) 2011

- 19.Miller DW, Feldman SR. Cost-effectiveness of moderate-to-severe psoriasis treatment. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2006;7:157–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pearce DJ, Thomas CG, Fleischer AB, Jr,et al. The cost of psoriasis therapies: considerations for therapy selection. Dermatol Nurs 2004;16:421–8, 432 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lucka TC, Pathirana D, Sammain A, et al. Efficacy of systemic therapies for moderate-to-severe psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of long-term treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2012;26:1331–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmitt J, Zhang Z, Wozel G, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of biologic and nonbiologic systemic treatments for moderate-to-severe psoriasis: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br J Dermatol 2008;159:513–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naldi L, Rznay B. Psoriasis (chronic plaque). Clin Evid 2009;1706:1–109 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vieira FS, Zucchi P. Distorções causadas pelas ações judiciais à política de medicamentos no Brasil. Rev Saúde Pública 2007;41:214–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Biehl J, Amon JJ, Socal MP, et al. Between the court and the clinic: lawsuits for medicines and the right to health in Brazil. Health Hum Rights 2012;14:E36–52 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chieffi AL, Barata RB. [‘Judicialization’ of public health policy for distribution of medicines]. Cad Saude Publica 2009;25:1839–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Lavis JN, et al. Knowledge translation of research findings. Implement Sci 2012;7:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA 1999;282:1458–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.