Abstract

Objective

Maternal and child health (MCH) care may provide an entry point for HIV services in high HIV-prevalence settings. Our objective was to assess integration of HIV with MCH services in public sector facilities in Swaziland.

Design

In 2009, 2010 and 2012, client flow assessments (CFAs) were conducted over 5 days in the MCH units of eight government facilities, purposively selected as intervention or comparison sites.

Participants

8263 MCH visits with female clients were tracked: 3261 in 2009, 2086 in 2010 and 2916 in 2012.

Intervention

Activities and resources to strengthen integration of HIV services into postnatal care (PNC), 2009–2010.

Main outcome measures

The proportion of all visits in which an HIV/sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing, counselling or treatment was received together with an MCH service; the proportion of all visits in which a client receives HIV counselling.

Results

Across facilities, the proportion of visits in which HIV/STI and MCH services were received varied considerably, for example, from 9% to 49% in 2009. HIV/STI services were integrated most frequently with child health (CH), antenatal care (ANC) and family planning (FP)—the most common reasons for women's attendance—and least often with PNC and cervical screening (CS). There was no meaningful difference in integration over time by design group and considerable heterogeneity across facilities. Receipt of integrated services increased in one intervention and two comparison facilities, where HIV counselling also rose, and fell in one intervention and two comparison facilities.

Conclusions

Provision of HIV/STI services with MCH care occurred at all facilities, yet relatively few women receive integrated services. Increases in integration were driven by increases in HIV counselling, while sharp declines in some facilities indicate that integration is difficult to sustain. Opportunities for intensifying HIV integration lie with ANC, CH and FP, while HIV-PNC integration will remain limited until more women attend PNC.

Trial registration number

Current Controlled Trials NCT01694862.

Keywords: REPRODUCTIVE MEDICINE, SEXUAL MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The main strength is the scale and novelty of client flow data in public sector facilities in sub-Saharan Africa, offering detailed combinations of services received in every consultation. Such detail is typically unavailable from routine health information systems.

The study fills a current gap in evidence—regarding the feasibility of integrating HIV services with infant/child health services and postnatal services.

An important limitation is the logistical challenge in conducting client flow assessments simultaneously across eight government facilities, affecting comparability of data across facilities and time points.

Considerable heterogeneity among facilities hindered the utility of comparisons by design group; facility-level comparisons were considered more informative.

Introduction

Maternal mortality and HIV have been described as ‘intersecting epidemics’ which must be simultaneously tackled.1 2 In the setting for this study—Swaziland, where more than 40% of pregnant women are infected with HIV—HIV is intimately linked with maternal mortality and hinders efforts to lower maternal death rates.3 4

Since the International Conference on Population and Development in 1994, a strong case has been made for integrating HIV services into sexual and reproductive health (SRH) with potential benefits for both clients and facilities.5 6 Integration can simultaneously address clients’ reproductive health goals and their needs for HIV prevention and treatment and prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT).7 Process evaluations of integrated HIV and family planning (FP) services indicate that facilities can gain by increasing the provision, uptake and efficiency of services while improving client satisfaction and reducing HIV-related stigma in clinics.8

Recently, the case for expanding integration of HIV/AIDS services to maternal, neonatal, child health (CH) and nutrition, including FP, has been supported in a systematic review which concludes that integration of such services is feasible to implement under certain circumstances.9 Furthermore, such integration can yield positive effects on the quality of services as well as client outcomes, including contraceptive use, antiretroviral therapy (ART) in pregnancy and HIV testing.9

Maternal and child health (MCH) services can thus serve as entry points for HIV prevention, treatment and care, particularly in contexts of high HIV prevalence. Yet, little is known about existing levels of integration, particularly in public sector health facilities, or how provision can be improved and scaled up.8

The Integra Initiative is a large-scale non-randomised evaluation designed to assess different models of SRH-HIV integration, including the integration of HIV/STI services with postnatal care (PNC) in Swaziland. Although not a randomised controlled trial, Integra was registered for good practice and transparency (Current Controlled Trials NCT01694862). The specific models of integration and their hypothesised benefits for clients and healthcare efficiency are detailed in the Integra study protocol.10 In brief, Integra defines integration as the provision of two or more services in the same visit, with the model in Swaziland focusing on PNC as an entry point for HIV/STI counselling, testing and/or treatment services.

As part of the Integra Initiative, this study analysed client flow data collected in eight public sector facilities in Swaziland in 2009, 2010 and 2012 to determine whether clients seeking MCH services receive integrated services, and if so, in what combinations of HIV/STI and MCH services.10 We also sought to understand how the receipt of integrated services differs over time and between facilities which did and did not receive the Integra intervention. We hoped the answers would help identify gaps and opportunities for integrating HIV within maternal health services and achieving universal access to both.

Methods

Data collection

As part of Integra's non-randomised design, eight public sector facilities were selected from three of Swaziland's four regions. Four facilities were purposively designated as Intervention facilities (referred to as Facilities A–D) based on their previous participation in an operations research study by Population Council, one of the Integra institutional partners.11 Four comparison facilities were selected based on their distance from intervention sites (to avoid contamination) and no current (at the time in 2008) provision of integrated HIV-PNC services (Facilities E–H), as determined by discussions with the Ministry of Health and site visits by Population Council.

In the intervention facilities, between October 2009 and December 2010, Integra delivered a programme designed to strengthen and maintain the provision of integrated HIV and PNC services. The intervention components included: (1) a training package to facilitate mentoring of front-line health providers by more experienced providers; (2) job aids to promote integration, including the Balanced Counselling Strategy Plus (BCS+) toolkit containing an algorithm, counselling cards and brochures to support counselling, including HIV service provision, within PNC consultations11 12 and (3) ongoing support to discuss role clarification, organisational change, referral/linkages and management of service statistics.

The client flow assessments (CFAs) comprise one data component of the Integra evaluation. The CFAs were modelled on the Patient Flow Analysis, a method developed by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in the 1970s to track patients’ movements through a clinic over 1 day,13 14 and shown to be effective in measuring intervention effectiveness within the context of usual practice.15 In this context, CFAs were designed to capture service utilisation patterns among clients seeking MCH services, given that data on integrated service provision were not available from routine clinical data (which collect data on different services in separate registers). Specifically, CFAs were conducted in all study facilities in November 2009, December 2010 and August 2012. Over a period of 5 days, Monday through Friday, all clients entering the facility for MCH services were given a client flow form by teams of trained local researchers or service providers. Clients carried the form throughout their visit, and each service provider they saw completed the form in their consultation room/cubicle, indicating session start/end times, the service(s) received by the client and any referrals to other providers.

The first CFA (late November 2009) was conducted soon after the intervention began in October 2009, but before it was fully implemented in any site. For logistical reasons, the CFAs could not be conducted in the same week of each year, and specific circumstances in some facilities meant that assessments could not be simultaneous in all eight sites, as the protocol had intended. In some facilities, with the support of facility managers, CFAs were conducted for more than the 5 days intended. To preserve the original protocol design, we restricted this analysis to the first Monday through Friday on which data were collected.

Data analysis

We defined our unit of analysis to be a visit, which comprised all providers seen and services received in the same day for each client, as captured on the client assessment form. Clients were either a single adult or an adult plus a child. We excluded visits of males aged 12 years or over to focus on MCH services. The age of 12 was selected because reproductive health services were received by females as young as 12.

The following primary and secondary outcomes were calculated for each facility and time point:

Receipt of integrated HIV-MCH services: the proportion of all visits in which a client receives any HIV or STI service, specifically: HIV testing, counselling or treatment; PMTCT; or STI counselling or testing, and any of the following MCH services: FP counselling or provision; PNC for mother or baby; cervical cancer screening; CH (including weighing and immunisations); and antenatal care (ANC). We hypothesised that HIV-MCH integration would increase in facilities that received the Integra intervention.

Receipt of HIV counselling: the proportion of all visits in which a client receives HIV counselling. We hypothesised that HIV counselling would increase as a result of the Integra intervention, regardless of women's need for HIV testing or treatment which are not constant (medical histories, including the need for testing or treatment, were not captured on the CFA form).

We also sought to describe which MCH services were most commonly combined with HIV/STI services by calculating the percentage of visits in which an HIV/STI service was combined with each type of MCH service. We examined the change over time in the proportion of visits receiving integrated HIV/STI and MCH services (primary outcome) and HIV counselling (secondary outcome) separately for each facility. We used the 95% CI around the difference (in the 2010 and 2012 proportions compared with 2009) as an indication of whether the observed change was due to chance (if it included the null value of zero).

To examine differences in the key outcomes by design group, we calculated the risk difference in 2010 and 2012 (each compared with 2009) for intervention versus comparison facilities for the primary and secondary outcomes using a two-stage approach. In the first stage, we estimated facility-level residuals by fitting a logistic regression model and including terms to adjust for baseline value (corresponding proportion of visits in 2009), average annual client load (<10000, 10000+) and rural/urban status. Difference residuals were then obtained as the difference between the observed and predicted values (divided by facility size). In the second stage, we analysed the facility-level residuals based on the assumption that in the absence of any intervention effect the residuals should be distributed normally with no systematic difference between the intervention and comparison arms. Difference residuals were analysed using linear regression including an interaction term representing the difference in ‘change from baseline’ between the design groups.

Results

Across eight facilities, 3261 visits were tracked in November 2009, 2086 visits in December 2010 and 2916 in August 2012. Table 1 presents the general characteristics of the visits and facilities. Additional details about each facility are provided in online supplementary table S1. Overall, about half of the visits included an adult female and child (under 12 years) versus an adult client only, although this proportion varied across facilities (range 28–95%). In almost all facilities, clients received an average more than one service during their visit, with many receiving two or more. Each year, approximately 8% of clients did not receive any service or referral during their visit, with the highest proportions in the facilities with highest client load (eg, 18% of clients in facility B and 31% in facility D in 2010). In all facilities, and in both years, CH services were either the first or second most common service received. FP counselling or provision and ANC were among the top three services for most facilities. Across facilities, the least common services received were PNC and cervical screening (CS; see online supplementary table S2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the facilities, visits and services tracked in 2009, 2010 and 2012

| Intervention | 2009 | 2010 | 2012 | 2009 | 2010 | 2012 | 2009 | 2010 | 2012 | 2009 | 2010 | 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facility A |

Facility B |

Facility C |

Facility D |

|||||||||

| Visits tracked | 590 | 475 | 532 | 855 | 263 | 408 | 211 | 184 | 241 | 753 | 411 | 607 |

| Client category | ||||||||||||

| Adult (12+ years) only | 395 (66.9%) | 196 (41.3%) | 211 (39.7%) | 443 (51.8%) | 153 (58.2%) | 172 (42.2%) | 144 (68.2%) | 87 (47.3%) | 82 (34%) | 310 (41.2%) | 197 (47.9%) | 408 (67.2%) |

| Adult+child | 176 (29.8%) | 278 (58.5%) | 320 (60.2%) | 153 (17.9%) | 109 (41.4%) | 236 (57.8%) | 64 (30.3%) | 97 (52.7%) | 156 (64.7%) | 93 (12.4%) | 213 (51.8%) | 198 (32.6%) |

| Adult age | ||||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 26.2 (6.4) | 26.2 (7.2) | 26.3 (6.5) | 26.8 (8.2) | 27 (7.2) | 26.6 (7.3) | 28.5 (8.4) | 26.8 (8) | 27.7 (8.5) | 27.6 (7.4) | 27.3 (8.4) | 31.3 (10.2) |

| Missing | 9 (1.5%) | 258 (54.3%) | 17 (3.2%) | 357 (41.8%) | 40 (15.2%) | 13 (3.2%) | 2 (0.9%) | 2 (1.1%) | 1 (0.4%) | 382 (50.7%) | 165 (40.1%) | 12 (2%) |

| Services received per visit | ||||||||||||

| None | 37 (6.3%) | 24 (5.1%) | 88 (16.5%) | 134 (15.7%) | 47 (17.9%) | 23 (5.6%) | 11 (5.2%) | 6 (3.3%) | 32 (13.3%) | 93 (12.4%) | 129 (31.4%) | 29 (4.8%) |

| One | 319 (54.1%) | 106 (22.3%) | 192 (36.1%) | 479 (56%) | 145 (55.1%) | 208 (51%) | 47 (22.3%) | 57 (31%) | 114 (47.3%) | 246 (32.7%) | 135 (32.8%) | 238 (39.2%) |

| Two or more | 234 (39.7%) | 345 (72.6%) | 252 (47.4%) | 242 (28.3%) | 71 (27%) | 177 (43.4%) | 153 (72.5%) | 121 (65.8%) | 95 (39.4%) | 414 (55%) | 147 (35.8%) | 340 (56%) |

| Visits where ≥1 service received | ||||||||||||

| Mean (SD) services received | 1.8 (1.3) | 2.5 (1.4) | 2.6 (2) | 1.6 (1.1) | 1.4 (.8) | 2 (1.6) | 2.6 (1.7) | 2 (1) | 1.9 (1.3) | 2.1 (1.2) | 2 (1.3) | 2 (1.3) |

| Mean (SD) providers seen | 1.3 (0.5) | 1.5 (0.5) | 1.6 (0.9) | 1.2 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 1.4 (0.7) | 1.3 (0.5) | 1.1 (0.4) | 1.3 (0.5) | 1.5 (0.7) | 1.5 (0.7) | 1.1 (0.3) |

| Visits where no services were either referred or received | 36 (6.1%) | 22 (4.6%) | 88 (16.5%) | 112 (13.1%) | 47 (17.9%) | 15 (3.7%) | 7 (3.3%) | 6 (3.3%) | 16 (6.6%) | 81 (10.8%) | 69 (16.8%) | 29 (4.8%) |

| Average annual client load* | 32 321 | 65 794 | 9974 | 40 485 | ||||||||

| Setting (urban/rural) | Urban | Urban | Peri-urban | Urban | ||||||||

| Comparison | Facility E |

Facility F |

Facility G |

Facility H |

||||||||

| Visits tracked | 220 | 215 | 380 | 317 | 333 | 347 | 146 | 170 | 114 | 169 | 35 | 287 |

| Client category | ||||||||||||

| Adult (12+ years) only | 131 (59.5%) | 72 (33.5%) | 234 (61.6%) | 194 (61.2%) | 183 (55%) | 154 (44.4%) | 74 (50.7%) | 106 (62.4%) | 47 (41.2%) | 110 (65.1%) | 2 (5.7%) | 178 (62%) |

| Adult+child | 78 (35.5%) | 143 (66.5%) | 145 (38.2%) | 117 (36.9%) | 150 (45%) | 193 (55.6%) | 69 (47.3%) | 64 (37.6%) | 67 (58.8%) | 48 (28.4%) | 33 (94.3%) | 107 (37.3%) |

| Adult age | ||||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 26 (7.5) | 26 (5.9) | 34.5 (12.6) | 26.1 (6.2) | 26.4 (6.3) | 26.5 (7.4) | 27.4 (7.8) | 31.4 (10.8) | 26.5 (7.2) | 25.1 (6) | 29.5 (10.6) | 30.9 (11.9) |

| Missing | 1 (.5%) | 95 (44.2%) | 53 (13.9%) | 5 (1.6%) | 124 (37.2%) | 9 (2.6%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (3.5%) | 5 (4.4%) | 0 (0%) | 33 (94.3%) | 67 (23.3%) |

| Services received per visit | ||||||||||||

| None | 10 (4.5%) | 3 (1.4%) | 13 (3.4%) | 1 (0.3%) | 5 (1.5%) | 8 (2.3%) | 11 (7.5%) | 6 (3.5%) | 14 (12.3%) | 31 (18.3%) | 0 (0%) | 29 (10.1%) |

| One | 99 (45%) | 34 (15.8%) | 45 (11.8%) | 100 (31.5%) | 177 (53.2%) | 46 (13.3%) | 19 (13%) | 84 (49.4%) | 32 (28.1%) | 32 (18.9%) | 8 (22.9%) | 155 (54%) |

| Two or more | 111 (50.5%) | 178 (82.8%) | 322 (84.7%) | 216 (68.1%) | 151 (45.3%) | 293 (84.4%) | 116 (79.5%) | 80 (47.1%) | 68 (59.6%) | 106 (62.7%) | 27 (77.1%) | 103 (35.9%) |

| Visits where ≥1 service received | ||||||||||||

| Mean (SD) services received | 1.8 (1.1) | 2.4 (1.1) | 3.2 (1.6) | 2.3 (1.6) | 1.6 (0.9) | 3.4 (1.6) | 3.2 (1.6) | 1.6 (0.6) | 2.6 (1.6) | 2.7 (1.6) | 2.8 (1.3) | 1.8 (1.5) |

| Mean (SD) providers seen | 1.3 (.5) | 1.1 (.2) | 1.7 (0.7) | 1.8 (0.8) | 1 (0.2) | 1.3 (0.6) | 1.5 (0.5) | 1.4 (0.6) | 1.3 (0.6) | 1.4 (0.6) | 1.1 (0.3) | 1.2 (0.5) |

| Visits where no services were either referred or received | 9 (4.1%) | 2 (0.9%) | 12 (3.2%) | 1 (0.3%) | 5 (1.5%) | 7 (2%) | 11 (7.5%) | 5 (2.9%) | 8 (7%) | 3 (1.8%) | 0 (0%) | 21 (7.3%) |

| Average annual client load* | 7736 | 28 202 | 9674 | 6959 | ||||||||

| Setting (urban/rural) | Rural | Peri-urban | Rural | Rural | ||||||||

*Annual client load taken from health facility assessments conducted for the Integra Initiative in 2010. All tables are N (%) unless indicated otherwise.

Receipt of integrated HIV-MCH services

There was evidence of HIV-MCH integration at all facilities and time points, although the extent of integration (the proportion of visits in which integrated HIV-MCH services were received) varied by facility: specifically, between 9% and 49% in 2009, 2% and 22% in 2010, and 10% and 44% in 2012 (see table 2). In the short term, five facilities experienced declines in integration between 2009 and 2010: by 7% and 13% points in two intervention facilities; and by 12%, 19% and 48% points in three comparison facilities. In the longer term, integration increased in one intervention site (facility A, from 9% in 2009 to 17% of visits in 2012) and two comparison facilities (facility E, from 11% to 37%; and facility F, from 16% to 44% in 2012, after experiencing an initial drop to 9% in 2010). Meanwhile, integration fell in one intervention site (facility C, from 33% to 16%) and two comparison facilities (facility G, from 49% to 27%; facility H, from 25% to 14%). Two intervention facilities (B and D) experienced no significant change in HIV-MCH integration between 2009 and 2012.

Table 2.

Proportion of visits receiving the primary and secondary outcomes, by facility, year and design group

| Intervention | Outcome | Change from baseline | Outcome | Change from baseline | Outcome | Change from baseline | Outcome | Change from baseline | Outcome* | Change from baseline† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facility A |

Facility B |

Facility C |

Facility D |

All intervention facilities |

||||||

| Outcome 1: Any HIV/STI service plus any MCH service received in same visit | ||||||||||

| 2009 | 54/590 (9.2%) | 83/855 (9.7%) | 69/211 (32.7%) | 98/753 (13%) | 16.1% | |||||

| 2010 | 74/475 (15.6%) | 6.4% (2.4 to 10.4) | 6/263 (2.3%) | −7.4% (−10.1 to −4.7) | 38/184 (20.7%) | −12% (−20.7 to −3.4) | 73/411 (17.8%) | 4.7% (0.3 to 9.2) | 14.1% | −0.8% (−19.3 to 17.7) |

| 2012 | 91/532 (17.1%) | 8% (4 to 11.9) | 40/408 (9.8%) | 0.1% (−3.4 to 3.6) | 38/241 (15.8%) | −16.9% (−24.8 to −9.1) | 78/607 (12.9%) | −0.2% (−3.8 to 3.4) | 13.9% | −8.1% (−27.0 to 10.8) |

| Outcome 2: HIV counselling received | ||||||||||

| 2009 | 38/590 (6.4%) | 38/855 (4.4%) | 56/211 (26.5%) | 24/753 (3.2%) | 10.2% | |||||

| 2010 | 72/475 (15.2%) | 8.7% (4.9 to 12.5) | 20/263 (7.6%) | 3.2% (−0.3 to 6.6) | 30/184 (16.3%) | −10.2% (−18.2 to −2.2) | 54/411 (13.1%) | 10% (6.5 to 13.5) | 13.1% | 0.1% (−13.0 to 13.2) |

| 2012 | 81/532 (15.2%) | 8.8% (5.1 to 12.4) | 13/408 (3.2%) | −1.3% (−3.5 to 0.9) | 21/241 (8.7%) | −17.8% (−24.8 to −10.9 | 53/607 (8.7%) | 5.5% (3 to 8.1) | 9.0% | −11% (−32.6 to 10.6) |

| Comparison | Facility E |

Facility F |

Facility G |

Facility H |

All comparison facilities |

|||||

| Outcome 1: Any HIV/STI service plus any MCH service received in same visit | ||||||||||

| 2009 | 24/220 (10.9%) | 52/317 (16.4%) | 72/146 (49.3%) | 42/169 (24.9%) | 25.4% | |||||

| 2010 | 57/215 (26.5%) | 15.6% (8.4 to 22.8) | 30/333 (9%) | −7.4% (−12.5 to −2.3) | 6/170 (3.5%) | −45.8% (−54.4 to −37.2 | 5/35 (14.3%) | −10.6% (−23.9 to 2.7) | 13.3% | −10.8% (−29.2 to 7.7) |

| 2012 | 141/380 (37.1%) | 26.2% (19.8 to 32.6) | 154/347 (44.4%) | 28% (21.3 to 34.6) | 31/114 (27.2%) | −22.1% (−33.6 to −10.6 | 39/287 (13.6%) | −11.3% (−18.9 to −3.6) | 30.6% | 0.6% (−19.5 to 18.2) |

| Outcome 2: HIV counselling received | ||||||||||

| 2009 | 10/220 (4.5%) | 27/317 (8.5%) | 44/146 (30.1%) | 24/169 (14.2%) | 14.4% | |||||

| 2010 | 29/215 (13.5%) | 8.9% (3.6 to 14.3) | 13/333 (3.9%) | −4.6% (−8.3 to −0.9) | 4/170 (2.4%) | −27.8% (−35.6 to −20) | 3/35 (8.6%) | −5.6% (−16.3 to 5) | 7.1% | −10.1% (−23.1 to 3.0) |

| 2012 | 114/380 (30%) | 25.5% (20.1 to 30.8) | 202/347 (58.2%) | 49.7% (43.7 to 55.7) | 18/114 (15.8%) | −14.3% (−24.4 to −4.3) | 18/287 (6.3%) | −7.9% (−13.9 to −2) | 27.6% | 3.4% (−18.2 to 25.0) |

*Unadjusted cluster-level proportions analysed separately at each time point.

†Change from baseline adjusted for facility size and rural/urban status. All CIs are at 95% confidence level.

MCH, maternal and child health; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Combinations of HIV/STI and MCH services received

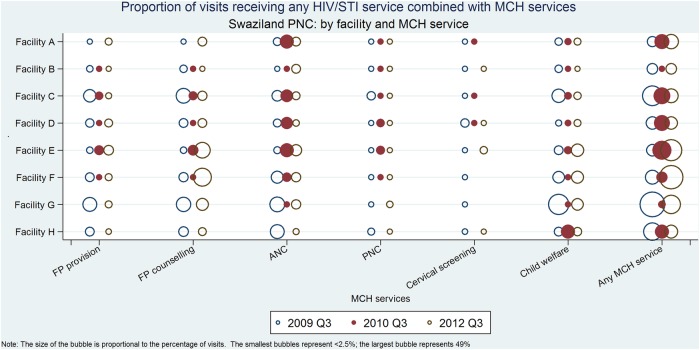

In 2009, at least one client in every facility received each type of HIV-MCH integration investigated, that is, one or more clients received integration of HIV-FP (provision and counselling), HIV-ANC, HIV-PNC (for mother or baby), HIV-CS and HIV-CH. Figure 1 shows the proportion of visits in which each service combination was received at each facility. The most common integration in 2009 was HIV with CH services (up to 33% of all visits in facility G), followed by HIV-ANC and HIV-FP (counselling or provision). Less frequent was integration of HIV services with PNC (a maximum of 6% of visits in facility C) or CS (maximum 6% of visits in facility D).

Figure 1.

Proportion of visits receiving any HIV/STI service combined with MCH services Swaziland PNC: by facility and MCH service. STI, sexually transmitted infection; MCH, maternal and child health; PNC, postnatal care; FP, family planning; ANC, antenatal care.

In 2010, integration of HIV services with the MCH services no longer occurred in every facility. For example, in three facilities, there were zero visits in which integration of HIV services and FP occurred; in one intervention and all comparison facilities, there was no integration of HIV services and CS services; and in two comparison sites, there were no cases of HIV-ANC and HIV-PNC integration. Excluding the latter two sites, integration of HIV-ANC was the most common type of integration in 2010. Between 2009 and 2012, HIV integration with FP counselling rose in facilities A, E and F—the same facilities that experienced increases in overall HIV-MCH integration. HIV-FP counselling integration declined in the other facilities, and integration of HIV and PNC services—the focus of the intervention—remained low in all facilities over time.

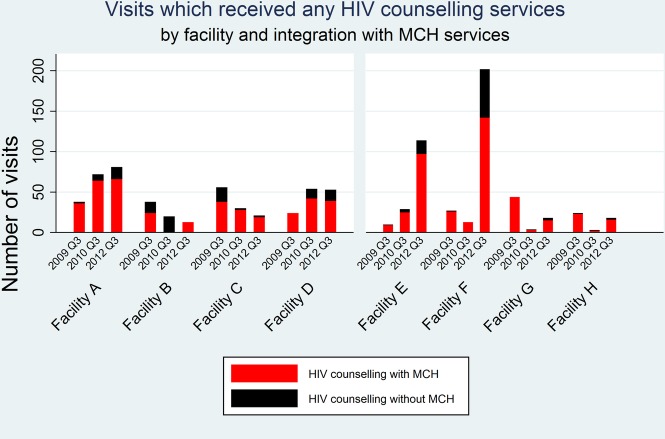

Receipt of HIV counselling

As a secondary outcome, we hypothesised that HIV counselling would increase in the intervention facilities. Table 2 shows that the proportion of visits in which a client received HIV counselling increased between 2009 and 2012 in two intervention (A and D) and two comparison facilities (E and F), and declined in two intervention sites (facility C) and two comparison sites (G and H). The absolute numbers of visits that included HIV counselling are presented in figure 2, which also shows that HIV counselling was more often provided in combination with an MCH service than alone. Specifically, HIV counselling was most often provided together with ANC, FP counselling or CH services (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Visits which received any HIV counselling services by facility and integration with MCH services. MCH, maternal and child health; PNC, postnatal care.

Evidence of an intervention effect

As shown in table 2 (final column), there was no statistical evidence that integration increased over time in intervention facilities as a group. On average, the intervention facilities provided integrated services in 16% of visits in 2009 and 14% in 2010 and 2012. Nor was there statistical evidence that the proportion of visits providing HIV counselling increased in the intervention group (averaging 10% in 2009 and 9% in 2012). In the comparison group, overall HIV-MCH integration and HIV counselling increased between 2009 and 2012 (by 5% and 13% points) after experiencing a decline in 2010. For these differences, 95% CIs include the null value of zero. Between the intervention and comparison groups, there was no statistical difference in change from baseline levels of HIV-MCH integration or provision of HIV counselling (data not shown).

Discussion

With what we believe are among the most detailed data on HIV-MCH integration in the public sector in Africa, we have been able to assess the extent to which clients are receiving integrated services, and in which combinations over time. The CFAs have shown that HIV/STI services (counselling, testing and treatment) are being integrated with a wide range of MCH services, including FP, ANC, PNC, CS and CH services. This is evidence of the capacity to integrate, in large urban facilities as well as small, rural facilities across Swaziland. It also fills a current gap in evidence—regarding the feasibility of integrating HIV services with infant/CH services and postnatal/postpartum services. A recent systematic review of integration evaluations identified both models as ‘inadequately studied’ to date.9

Nevertheless, integration occurred in a minority of visits and varied considerably across facilities. Furthermore, the level of integration fell in three of the eight facilities between 2009 and 2012. The facility with the highest level of integration in 2009 dropped to the lowest a year later (from 49% to <2%). This may be explained by the existence of an NGO campaign to increase access to ART in the area of that facility during the 2010 assessment, as HIV treatment appears to have displaced almost all other HIV and MCH services. This suggests that integration can be susceptible to vertical programmes or competing priorities, particularly in smaller facilities where the 2010 declines in integration were steepest.

It is also possible that integration declined in settings where clients did not need HIV services with every visit. The CFA did not capture clients’ history or need for such services, and thus we cannot interpret observed changes in their provision. For this reason, we were particularly interested in the provision of HIV counselling, which can be promoted regardless of the need for testing or treatment. HIV counselling rose in two intervention and two comparison facilities. In the three sites where HIV-MCH integration rose, this appeared to be driven by an increase in HIV counselling. That HIV counselling was most often provided with an MCH service rather than alone suggests that it has a role to play in scaling up integration, but requires a concerted effort to sustain its provision.

The most common form of integration observed was between HIV services and CH, followed by ANC and FP. These services may offer the best opportunities for integration with HIV, given most women attended for CH, ANC and FP services. This is particularly encouraging in light of a recent review concluding that uptake of PMTCT in sub-Saharan Africa is inadequate, but improves with an integrated family-centred approach, for example, if HIV treatment is provided at antenatal clinics.7

Less common was integration of HIV/STI with PNC or CS, most likely due to the lower number of clients receiving PNC and CS relative to other services (or PNC clients may have received HIV/STI testing in recent ANC visits). This suggests that potential effectiveness of the Integra Initiative—which focuses on HIV-PNC integration in Swaziland—may be limited until more clients attend for PNC services, and this may require further investment in equipment and training for PNC (as well as CS, as only one facility had the capacity to offer immediate cryotherapy) as well as demand creation to increase service uptake.

The formal comparison of integration by study design (intervention vs comparison sites) showed no statistical difference in HIV-MCH integration over time. There was also no meaningful difference in the receipt of HIV counselling in the intervention group over time.

Limitations and the challenges of embedding research in ‘real-world’ settings

The observed changes in levels of integration and absence of an intervention effect could be due to a number of factors which we were unable to account for given the non-randomised design, as well as challenges implementing the protocol as intended.

With regard to design, in a small country with limited number of facilities, intervention sites could not be matched with similar-sized comparison facilities. This resulted in systematically different groups, with intervention facilities primarily large and urban, and comparison facilities mostly small and rural. Also, the comparison sites—which were determined to have no provision of integration prior to the study in 2008—were shown via the CFAs to be offering integrated HIV-RH services by 2009. Given the heterogeneity and the focus on a facility-specific outcome in this analysis, we felt it was more informative to compare changes by facility than study design. The wide variation we observed across facilities likely reflects the different capacities and infrastructure available to provide integrated services, that is, facilities cannot follow the same ‘blue print’ for integration, particularly given the variability in facility size, client volumes and staffing levels among the eight study facilities. Detailed case studies are underway to explore the role of facility differences in greater depth, including intervention dose and quality, as well as contextual information, to enhance interpretation of the levels and patterns of integration revealed by the CFAs.

Some observed changes may also be due to ‘seasonal’ differences in 2009 and 2010. Coordinating CFAs across eight facilities proved logistically challenging, and synchronicity was not always achieved as intended. In 2010, most assessments were delayed until the week before Christmas (as compared with November 2009) which may account for the smaller number of clients in most facilities in 2010. This timing may have affected the range of services provided and may account for different patterns of integration. Smaller, rural facilities—where the drops in integration were the steepest—may be impacted more than large, rural sites during such holiday periods.

It is also possible that provision of HIV and MCH services may fluctuate frequently or periodically, in patterns we could not detect from 5-day ‘snapshot’ assessments (regardless of their specific timing). An early evaluation of CDC's ‘patient flow analysis’ method, conducted over 1 day in FP clinics in Kenya, concluded that ‘the “typical” clinic day does not really exist. The client/patient load and staffing patterns are likely to vary according to many factors: by day of the week, or season of the year, staff vacation or sickness, etc’.14 Assessments were extended to 5 days in this study, yet, the ‘typical’ clinic week does not exist. It may be more informative to monitor over a longer period for more representative data. However, the 5-day assessments proved challenging and resource intensive to implement, and longer versions may be prohibitive in many settings. Previous evaluations of patient flow analyses also note that data may not be representative since staff—aware of the assessment—may try to perform at their best.14 For these reasons, strengthening routine data collection systems may be preferable, but many existing systems record services individually in separate registers, and are thus unable to document service integration without fundamentally changing the system. It was this barrier that led us to utilise the client flow assessment.

Conclusions

The client flow assessment provided rich details about the range and combinations of services received by large number of clients. This was valuable for understanding whether and how HIV and MCH services are integrated in practice. The data confirm that, in a context of high HIV prevalence, capacity exists in public sector services for integration of HIV services into MCH care. In particular, ANC, CH and FP provide promising entry points for reaching the largest number of women. Sustaining HIV-MCH integration may require concerted effort over time. The study limitations reflect the challenges of embedding rigorous research into existing and diverse facilities (ie, ‘real-world’ evaluations) and difficulties in recording the provision of integrated services.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the clients and the Integra fieldwork team for collecting and managing the data used in this analysis. The Integra research PI's are: SM, CW and Anna Vassall. We also acknowledge the support of the Ministry of Health and facility managers and providers for supporting and facilitating the client flow assessments. We thank Carol Dayo Obure for contributing data from health facility assessments, and Emma Slaymaker for inspiring figure 1.

Footnotes

Contributors: SM, JK, CW, KC and RN helped to design the data collection. JK managed the data collection. JF and WZ cleaned and managed the datasets. IJB and JF led the analysis. All authors provided input into the data interpretation. IJB drafted the manuscript. All authors read and commented on a complete draft.

Funding: This work was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (grant number 48733).

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Swaziland Scientific Review Board, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Ethics Commitee and Population Council Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The dataset will be made available via an LSHTM repository on completion of the Integra Initiative.

References

- 1.McIntyre J. Mothers infected with HIV. Br Med Bull 2003;67:127–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.PLoS Medicine Editors HIV in maternal and child heath: concurrent crises demand cooperation. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdool-Karim Q, Abouzahr C, Dehne K, et al. HIV and maternal mortality: turning the tide. Lancet 2010;375:1948–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kingdom of Swaziland . Swaziland Country Report on Monitoring the Political Declaration on HIV and AIDS Kingdom of Swaziland, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 5.United Nations Programme of Action of the United Nations International Conference on Population and Development Cairo, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO, UNAIDS, IPPF UNFPA Linking Sexual and Reproductive Health and HIV/AIDS. Geneva: UNFPA, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wettstein C, Mugglin C, Egger M, et al. Missed opportunities to prevent mother-to-child-transmission in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS 2012;26:2361–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Church K, Mayhew SH. Integration of STI and HIV prevention, care, and treatment into family planning services: a review of the literature. Stud Fam Plann 2009;40:171–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindegren ML, Kennedy CE, Bain-Brickley D, et al. Integration of HIV/AIDS services with maternal, neonatal and child health, nutrition, and family planning services. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;9:CD010119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warren CE, Mayhew SH, Vassall A, et al. Study protocol for the Integra Initiative to assess the benefits and costs of integrating sexual and reproductive health and HIV services in Kenya and Swaziland. BMC Public Health 2012;12:973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warren C, Shongwe R, Waligo A, et al. Repositioning postnatal care in a high HIV environment: Swaziland. Population Council, Horizons, 2008. http://www.popline.org/node/206889 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Population Council. The Balanced Counseling Strategy Plus: a toolkit for family planning service providers working in High HIV/STI prevalence settings http://www.popcouncil.org/publications/books/2012_BalancedCounselingStrategyPLUS.asp2012.

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/ProductsPubs/PFA_support/

- 14.Lynam PF, Smith T, Dwyer J. Client flow analysis: a practical management technique for outpatient clinic settings. Int J Qual Health Care 1994;6:179–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Potisek NM, Malone RM, Shilliday BB, et al. Use of patient flow analysis to improve patient visit efficiency by decreasing wait time in a primary care-based disease management programs for anticoagulation and chronic pain: a quality improvement study. BMC Health Services Research 2007;7:8 doi:10.1186/1472-6963-7-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.