Abstract

Little is known about how adolescents and young adults contribute to the declines in the cascade of care from HIV-1 diagnosis to viral suppression. We reviewed published literature from the Unites States reporting primary data for youth (13–29 years of age) at each stage of the HIV cascade of care. Approximately 41% of HIV-infected youth in the United States are aware of their diagnosis, while only 62% of those diagnosed engage medical care within 12 months of diagnosis. Of the youth who initiate antiretroviral therapy, only 54% achieve viral suppression and a further 57% are not retained in care. We estimate less than 6% of HIV-infected youth in the United States remain virally suppressed. We explore the cascade of care from HIV diagnosis through viral suppression for HIV-infected adolescents and young adults in the United States to highlight areas for improvement in the poor engagement of the infected youth population.

Introduction

In the past several years, there have been new developments supporting earlier initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART).1–3 Simpler, more potent, and less toxic regimens have achieved high levels of sustained HIV viral suppression in clinical trials4 and in clinical practice.5,6 A large, multinational, randomized controlled trial has demonstrated the efficacy of how early initiation of antiretroviral treatment can decrease HIV transmission.1 However, several distinct American populations are not yet benefiting from the movement towards earlier ART initiation.7–9 Adolescents and young adults, particularly black young men who have sex with men (MSM), are still being infected at alarming rates and are not seeking treatment in a timely manner.7–9 When they do enter care, they typically already have advanced HIV disease.7,10 The incidence of new HIV infections in these populations remains disproportionately high compared to the general population, as well as other groups of MSM, and continues to rise.8,9

Several groups have recently developed a framework to evaluate the gaps between the number of people living with HIV in the U.S. and those who are virologically suppressed, using metrics defined by the U.S. Government's National AIDS Strategy.11–13 The HIV cascade of care tracks individuals from HIV diagnosis through linkage to care, ART initiation, retention in care, to ultimately viral suppression. The cascade analyses in the United States indicates that, despite movement for early initiation, less than 30% of HIV-infected adults are stably living with suppressed viral replication.11 Large numbers of Americans remain unaware of their serostatus, do not link, engage, or remain stably in care, do not initiate timely treatment, or do not adhere to their medication regimens.11 This has obvious implications for practical translation of test and treat strategies for HIV prevention, particularly for specific populations who are not diagnosed, treated, or retained in care.

The purpose of this review is to highlight the difference in the HIV cascade of care from HIV diagnosis to viral suppression among adolescents and young adults from older adults living with HIV. These differences may explain the high prevalence and increasing incidence of new HIV infections in this age group. In addition, they highlight areas that could be explored for targeted interventions resulting in earlier diagnosis, ART initiation, improved adherence and retention in care among HIV-infected adolescents and young adults.

Methods

We searched PubMed, Google Scholar, and online conference proceedings from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2012. Key words and Medical Subject Headings relevant to age (adolescent, adolescence, teen, youth, young adults) were cross-referenced with terms associated with the HIV Cascade of Care (diagnosis, testing, linkage, linkage to care, retention, retention in care, viral suppression, adherence, first-line, antiretroviral therapy, virologic failure). We reviewed literature in English reporting primary data from the United States, which included specific age ranges. Since studies reported variable age ranges, we included studies that specified age ranges to include youth aged 13–29. We report age ranges as described by the original authors. For the purpose of this review, we combine adolescents and young adults to include those aged 13–29 years.

Prevalence and Incidence of HIV Among Adolescents

As of 2010, the estimated number of HIV infections in the United States for those 13 years and older was 1,178,350.14,15 More than 6% of those infections occur in youth.9 The number of HIV infections in adolescents and young adults from ages 13–24 ranges between 56,000 and 80,600.9,12,14,15 From 2006 to 2009, the incidence of all new HIV infections has remained relatively stable; there were approximately 48,100 new HIV infections in the United States in 2009.8,16 However, among youth aged 13–29, there was a 21% increase in HIV incidence over this time period.8 This dramatic rise in new HIV infections was mostly due to significant increases in new infections among young black MSM.8,17 Among MSM aged 13–29, approximately 6500 (60%) new infections occurred in blacks in 2009 compared to 2700 (45%) for Latinos and 3200 (28%) for whites.8 Throughout this time period, the greatest increase (53%) in HIV/AIDS cases in MSM was among those aged 13–24 years.14 Data from 2010 suggests a similar trend. In 2010, there were 12,200 (26%) new infections in youth 13–24 years old.9 Of those, African Americans accounted for 57%, while MSM accounted for 72% of all infections among youths.9 In 2010, approximately 72.1% of all new HIV infections among youths aged 13–24 were attributed to male-to-male sexual contact, 19.8% to heterosexual contact with a known infected partner, 4.0% to injection drug use, and 3.7% to both male-to-male sexual contact and injection drug use.9

HIV Testing and Undiagnosed HIV Infection in Youth

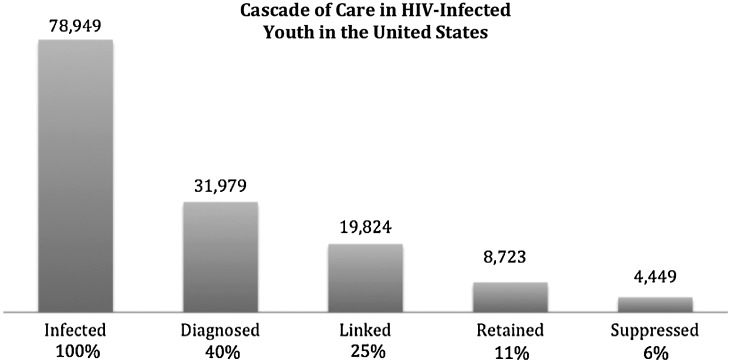

Despite having the highest incidence of new HIV infections, youth aged 18–24 have a low uptake of HIV testing. As of 2010, only between 40.5%9 and 41.1%15 of HIV-infected youth were aware they were living with HIV, as indicated in Fig. 1. This is dramatically lower than the national estimate that 80% of those 13 years and older in the United States are aware of their diagnosis.15 Undiagnosed HIV-infected individuals cannot benefit from antiretroviral therapy (ART). With ongoing viral replication and higher HIV burdens than treated persons, they are more likely to contribute to ongoing HIV transmission events if they have unprotected sex. The large difference in serostatus knowledge between youth (60% undiagnosed) and older adults (20% undiagnosed) highlights different risk perceptions and access to HIV testing.

FIG. 1.

Estimated cascade of care in HIV-infected youth (ages 13–29 years) in the United States.

HIV Testing Among Adolescents

According to the 2007 nationwide Youth Risk Behavior Survey conducted by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC), only 12.9% of all U.S. high school students had ever been tested for HIV.18 The study found that the prevalence of HIV testing increased with grade, younger age at first sexual experience, and receipt of HIV/AIDS education.18 Demographic factors suggest that among adolescents and young adults, HIV testing is higher among females,18,19 African American,7,8,18–23 and Latino/a 19,20,24 youth. Sexual factors associated with increased HIV testing among youth include having three or more sexual partners in the last three months,21 ever having a sexually transmitted infection (STI),21,25 inconsistent condom use,21 substance use,21 being a MSM or a female who had sex with a MSM,7,8,19,21–24 or having had sex with an HIV-infected partner.21 Healthcare-related factors associated with increased HIV testing among youth include those receiving Medicaid with a primary care physician who were recommended testing20 or had any healthcare in the past year.21 A study of high-risk Latino and African American gang members in Los Angeles found that only 33% had prior HIV testing.26 Many of these studies highlight that improving access and knowledge of HIV testing increases uptake among youth.

Correlates of HIV Infection

A national U.S. survey involving HIV-infected individuals older than 13 years old, found that 59% had a negative test prior to their HIV diagnosis.27 The highest incidence of recent seroconversion in this study was found in those aged 14–29 years and in MSM.27 HPTN 061, which enrolled 1556 black urban MSM, found higher rates of incident HIV infection among those aged 18–30 compared to older adults.28 Some smaller studies have seen higher incidence rates among older adults. However, age ranges vary among these studies.29,30 HIV-infected youth testing at STD clinics were more likely to return to receive confirmatory testing than older HIV-infected adults.31 Engaging young black MSM in the health system, offering HIV-preventative services, and providing routine HIV testing could decrease the number of new infections among the group with the highest HIV incidence.

Linkage to Care

In order to benefit from antiretroviral therapy, those who are diagnosed with HIV must successfully link to the healthcare system in a timely manner. Failure to successfully link to medical care can lead to disease progression and ongoing HIV transmission.32,33 While several adult studies suggest that approximately 75% of newly diagnosed adults are linked to care within one year,11,34–36 the data on adolescents and young adults are more concerning. Four separate studies found low rates of linkage to care for adolescents and young adults, ranging from between 29% and 73% within the first year of diagnosis.35,37–39 The ARTAS trial, an intervention designed to increase linkage to care using five sessions with a linkage case manager, successfully linked 73% of those aged 18–25 to care within the first 6 months, compared to 81% for older adults.37 Another intervention study, the California Bridge Project, successfully linked only 29% of those younger than 25 years of age who were previously out of care.38 There was no difference in successful linkage based on age group in this study. Observational studies suggest that approximately 62% of adolescents and young adults link to care within the first year of diagnosis.35,39,40 Other studies indicate that adolescents and young adults are less likely to link and remain in care than older adults.40–42 Some studies using different age ranges for analysis found no difference in linkage in younger adults.35,43–45 However, combining published data from these studies (Table 1), we estimate that 62% of newly diagnosed HIV-infected adolescents and young adults in the United States link to care within the first 6–12 months.

Table 1.

Published Literature from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2012, Addressing the Cascade of Care for HIV-Infected Adolescents and Young Adults (Age Range 13–29 years) in the United States

| Linkage to care | Age | N | Linked | Percent | Endpoint |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interventional studies | 198 | 124 | 63% | ||

| Craw, 2008 | 18–25 | 150 | 110 | 73% | 6 months |

| Molitor, 2006 | 18–25 | 48 | 14 | 29% | 12 months |

| Observational studies | 1,713 | 1,058 | 62% | ||

| Torian, 2008 | 13–29 | 529 | 364 | 69% | 3 months |

| Olatosi, 2009 | 18–24 | 268 | 180 | 67% | 3 years |

| Hall, 2012 | 13–24 | 916 | 514 | 56% | 1 year |

| Overall linkage to care | 1,911 | 1,182 | 62% |

| Viral suppression | Age | N | Suppressed | Percent | Endpoint |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interventional studies | 37 | 32 | 86% | ||

| Mckinney, 2007 | 3–21 | 37 | 32 | 86% | <400 at 16 weeks |

| Observational studies | 925 | 456 | 49% | ||

| Rudy, 2006 | 11–22 | 120 | 69 | 58% | <400 at 24 weeks |

| Flynn, 2004 | 18–22 | 111 | 69 | 62% | <400 at 24 weeks |

| Murphy, 2005 | 12–18 | 231 | 161 | 70% | <400 at 1 year |

| Ding, 2009 | 12–19 | 154 | 50 | 32% | 1.0 log reduction from baseline at 2nd post ART visit |

| Rutstein, 2005 | 1–17 | 263 | 80 | 30% | < 400 Cross sectional |

| Ryscavage, 2011 | 17–24 | 46 | 27 | 59% | <400 at 6 months |

| Overall viral suppression | 962 | 488 | 51% |

| Retention in care | Age | N | Retained | Percent | Endpoint |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interventional studies | 31 | 16 | 52% | ||

| Gardner, 2005 | 18–25 | 31 | 16 | 52% | 1 clinic visit within 12 months |

| Observational studies | 3,872 | 1,705 | 44% | ||

| Ikard, 2005a | 20–39 | 14,650a | 54% | CD4 or VL within last 12 months | |

| Ryscavage, 2011 | 17–24 | 46 | 26 | 57% | 36 months |

| Torian, 2011 | 13–29 | 154 | 57 | 37% | Regular care over 4 years |

| Hall, 2012 | 13–24 | 3,672 | 1,622 | 44% | ≥2 CD4 in 1 year |

| Overall retention | 3,903 | 1,721 | 44% |

The N of 14,650 is inclusive of the entire study population. Specific numbers based on ages were not reported; therefore, this data could not be used for the overall calculation.

Antiretroviral Therapy and Resistance

There is an increasing trend toward earlier initiation of ART. However, even with the trend to treat all HIV-infected individuals, significant barriers for successful ART treatment remain. First, HIV-infected individuals must be aware of their status and engage in care. Their physicians must be willing to accept potential barriers (erratic lifestyle, substance abuse, unstable housing, and nondisclosure) to initiating youth on life-long ART.46 Once in care, patients must remain in care and maintain a high degree of adherence to ART. Despite this, patients may experience baseline viral resistance or could develop resistance due to poor adherence, drug–drug interactions, medication side effects, malabsorption of medication, or any other factor that can cause prolonged low serum blood levels of ART. A large national U.S. study found 14% of the 856 adolescents and young adults aged 13–29 years had transmitted resistance compared to 15% for the entire cohort.47 Another multisite study of 130 HIV-infected young adults aged 18–24 found 9.2% carried transmitted HIV resistance mutations.48 Even with universal ART treatment, a significant portion of those who initiate therapy may not respond to typical first-line regimens.

Viral Suppression

Although recent studies with newer ART regimens have suggested high levels of viral suppression in adults,5,6 adolescents and young adults do not appear to achieve this goal. Recent first-line viral suppression rates after Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART) initiation for adolescents in clinical trials report suppression rates as high as 86%.49 However, observational studies report lower suppression rates ranging from 46% to 59%.50–53 Comparatively, adult first-line ART regimens report viral suppression rates between 79% in observational studies54 and 85–98% in clinical trials.52,55–58 By combining recent studies of potent ART regimens in adolescents and young adults, we estimate that only 51% achieve viral suppression to less than 400 copies/ml as indicated in Table 1.49–53,59,60

Adherence Among Adolescents

During adolescence, children with chronic illness commonly go through periods of poor adherence to medical regimens.61 Several studies have documented poor viral suppression rates or poor adherence among HIV-infected adolescents.62–64 Among HIV-infected adolescents, barriers to adherence include medical, psychological, and logistical reasons. Medical barriers shown to affect adherence in youth include an AIDS diagnosis,65 a difficult ART regimen,65 absence of symptoms,66 side effects of medication,67 and dissatisfaction with the health team/system.68 Logistical barriers such as forgetting medication doses,65–67 travel,66 and inconvenience/inconsistent routine66,67 commonly affect adherence in youth. Psychological barriers including depression/anxiety,69–72 perceived stigma,69 lack of support,72–74 behavioral and conduct problems71 are present in more than 50% of HIV-infected youth.75

Retention in Care

In order to sustain viral suppression while receiving antiretroviral therapy, it is essential to remain engaged in regular medical care. The ARTAS study found young adults aged 18 to 24 were significantly less likely (52%) to be retained in care than adults (59%) at one year of treatment (p=0.02).36 Another study found age was significantly associated with lack of retention in care in which 41% of those younger than age 25 were retained compared to 75% of those over 25 years old.76 A study from South Carolina found that only 31% of those aged 18–24 years were retained in care over 3 years.39 Others have also found low retention rates in young adults.40,77,78 Combining published data on adolescents and young adults, we estimate that 43% are retained in care over 1–3 years as indicated by Table 1.

Transition to Adult Care

Improvement in antiretroviral therapy has changed perinatal HIV infection from a terminal disease into a chronic, manageable infection requiring medication adherence.79 This presents an additional challenge for many perinatally infected and younger behaviorally infected adolescents cared for in pediatric or adolescent facilities who must transition to adult care in their late teens or early twenties.80,81 Although HIV-infected youth are more likely to have cognitive impairment and mental health problems,82 they are less likely to receive coordinated care in adult-oriented facilities.83 In addition, transition to adult services has been associated with lapses in adherence and worse clinical outcomes for adolescents with chronic illnesses.84–86 Changing of care providers, lack of youth-friendly services, rigid scheduling, increasing responsibilities, and decreasing involvement of adult caregivers all contribute to the challenges of transition care for adolescents and young adults.73,87

Access to Health Care

Youth with chronic illnesses are less likely to have health insurance than those in any other age group.88 In addition, HIV-infected individuals are more likely to lack health insurance than those who are uninfected.89 Lapses in health insurance, economic hardships, and lack of transportation can contribute to inconsistent HIV care for adolescents and young adults. The implementation of the Affordable Care Act may be able to decrease the health disparities experienced by this population, particularly because youth under 26 years old will be able to remain on their parents' insurance. However, because some of the youth may be alienated from their families due to lack of acceptance of their homosexuality and/or their HIV status, it will be necessary for all U.S. states to develop programs facilitating the access of emancipated minors to health insurance and stable medical care.

Discussion

Along the HIV cascade, adolescents and young adults appear to have larger declines than older adults in all steps, resulting in estimated viral suppression of less than 6% of those infected. The most striking difference between adolescents and young adults and older adults is in the number of undiagnosed youth. Approximately 80% of HIV-infected adults are aware of their status,11 compared to only 40% of adolescents and young adults. Sexual onset, particularly at younger ages, may place youth at increased risk despite the low risk perception.90 This contradiction likely contributes to low voluntary HIV testing among youth with early new infections.

Targeted HIV testing in this population is urgently needed to bridge this disparity. The American Academy of Pediatrics and U.S. CDC recommend routine HIV testing for all individuals aged 13–64.91 Campaigns using social marketing to promote and normalize HIV testing among youth have shown success at increasing HIV testing.54 In addition, venue-based testing promoting HIV testing in social venues where high-risk youth congregate are effective in identifying high proportions of previously undiagnosed youth.92 Increasing promotion, convenience, and availability of HIV testing demonstrates high uptake rates among youth.29,93 HIV testing needs to be integrated and expanded in areas where youth interact with the health system, particularly in sexual and reproductive health clinics, primary care clinics, and in emergency and urgent care facilities. These, in addition to venue-based testing, promoting recurrent testing among high-risk youth, and normalizing HIV testing, could reduce the number of undiagnosed HIV youth.

In addition to testing, linkage to care and retention in care account for a considerable drop off in the cascade of HIV-infected adolescents and young adults. Approximately 30% of the diagnosed youth are linked to care and retained for one year. Brief intensive case management and patient navigator systems have worked well with adults36,37,94 and are being used in adolescent networks.95 Peer or clinic-based system navigators form personal and professional relationships that break down some of the barriers to initiating care. The Adolescent Trials Network is focusing on improving relationships between testing sites and clinical sites, including multicultural, multilinguistic, LGBT and adolescent-friendly services to improve adolescent linkage to care.95 However, major barriers to linkage and retention in care exist, which include stigma, consent, payment, housing instability or homelessness, transportation, and mental health/substance use.95

HIV-infected adolescents may fall out of care when cared for in or transitioning to adult care facilities, which are more focused on the adult environment.60,96 Early multidisciplinary and developmentally appropriate transition preparation can assist in transitioning youth to adult services. This transition planning ideally would address issues inherent in adolescent health including mental health, medication adherence, sexuality, reproductive health, gender identity, socioeconomic and health insurance status, stigma, disclosure, and disrupted relationships.97

In addition, poor adherence among youth contributes to low viral suppression in those accessing treatment. There is no simple solution to improve adherence among youth. Successful adherence interventions are typically multifaceted and address specific adherence barriers. Simplifying treatment regimens, using directly observed therapy and cell phone reminders have shown promise in improving adherence among HIV-infected youth.98 In adults, treatment of underlying depression and offering cognitive behavioral therapy has shown to increase adherence.99 Research needs to explore new areas and tailor existing interventions for HIV-infected youth, particularly those with depression.

Although there have been significant developments in HIV prevention with pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)100,101 and treatment as prevention1 for adults, these interventions have not been sufficiently investigated, tailored, or scaled for youth. This cascade highlights that current efforts for treating already-infected adolescents and young adults remain a challenge. Most interventions to address the cascade have been developed for adults. These are not particularly generalizable to youth struggling with identity formation, economic hardships, and unstable housing. Youth-focused interventions are necessary to improve the HIV cascade for adolescents and young adults.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. . Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 2011;365:493–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson MA, Aberg JA, Cahn P, et al. . Antiretroviral treatment of adult HIV infection: 2010 recommendations of the International AIDS Society-USA panel. JAMA 2010;304:321–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. 2012; http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/adultandadolescentgl.pdf Accessed December14, 2012

- 4.Rockstroh JK, Lennox JL, Dejesus E, et al. . Long-term treatment with raltegravir or efavirenz combined with tenofovir/emtricitabine for treatment-naive human immunodeficiency virus-1-infected patients: 156-week results from STARTMRK. Clin Infect Dis 2011;53:807–816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Das M, Chu PL, Santos GM, et al. . Decreases in community viral load are accompanied by reductions in new HIV infections in San Francisco. PLoS One 2010;5:e11068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gill VS, Lima VD, Zhang W, et al. . Improved virological outcomes in British Columbia concomitant with decreasing incidence of HIV type 1 drug resistance detection. Clin Infect Dis 2010;50:98–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Millett GA, Peterson JL, Flores SA, et al. . Comparisons of disparities and risks of HIV infection in black and other men who have sex with men in Canada, UK, and USA: A meta-analysis. Lancet 2012;380:341–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prejean J, Song R, Hernandez A, et al. . Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2006–2009. PLoS One 2011;6:e17502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vital Signs: HIV infection, testing, and risk behaviors among youths–United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012;61:971–976 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu DJ, Byers R, Jr, Fleming PL, Ward JW. Characteristics of persons with late AIDS diagnosis in the United States. Am J Prev Med 1995;11:114–119 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, Del Rio C, Burman WJ. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52:793–800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Vital signs: HIV prevention through care and treatment–United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011;60:1618–1623 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The White House Office of National AIDS Policy National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States. The White House Office of National AIDS Policy, 2010

- 14.Center for Disease Control HIV/AIDS Statistics and Surveillance. 2012; http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/index.htm Accessed December/4/2012, 2012

- 15.Chen M, Rhodes PH, Hall IH, Kilmarx PH, Branson BM, Valleroy LA. Prevalence of undiagnosed HIV infection among persons aged >/=13 years—National HIV Surveillance System, United States, 2005–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012;61Suppl:57–64 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Center for Disease Control HIV surveillance—United States, 1981–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011;60:689–693 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Millett GA, Jeffries WLt, Peterson JL, et al. . Common roots: A contextual review of HIV epidemics in black men who have sex with men across the African diaspora. Lancet 2012;380:411–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Center for Disease Control HIV testing among high school students—United States, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2009;58:665–668 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caldeira KM, Singer BJ, O'Grady KE, Vincent KB, Arria AM. HIV testing in recent college students: Prevalence and correlates. AIDS Educ Prev 2012;24:363–376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim EK, Thorpe L, Myers JE, Nash D. Healthcare-related correlates of recent HIV testing in New York City. Prev Med 2012;54:440–443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Straub DM, Arrington-Sanders R, Harris DR, et al. . Correlates of HIV testing history among urban youth recruited through venue-based testing in 15 US cities. Sex Transm Dis 2011;38:691–696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall HI, Walker F, Shah D, Belle E. Trends in HIV diagnoses and testing among U.S. adolescents and young adults. AIDS Behav 2012;16:36–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Center for Disease Control HIV Surveillence in Adolescents and Young Adults. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/slides/msm/index.htm Accessed November15, 2012

- 24.Ober AJ, Martino SC, Ewing B, Tucker JS. If you provide the test, they will take it: Factors associated with HIV/STI testing in a representative sample of homeless youth in Los Angeles. AIDS Educ Prev 2012;24:350–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swenson RR, Rizzo CJ, Brown LK, et al. . Prevalence and correlates of HIV testing among sexually active African American adolescents in 4 US cities. Sex Transm Dis 2009;36:584–591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brooks RA, Lee SJ, Stover GN, Barkley TW. HIV testing, perceived vulnerability and correlates of HIV sexual risk behaviours of Latino and African American young male gang members. Int J STD AIDS 2011;22:19–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Previous HIV testing among adults and adolescents newly diagnosed with HIV infection—National HIV Surveillance System, 18 jurisdictions, United States, 2006–2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012;61:441–445 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koblin BMKE S, Wang L, Shoptaw S, et al. . Correlates of HIV incidence among black men who have sex with men in 6 U.S. cities (HPTN 061). 19th International AIDS Conference: Abstract no. MOAC0106, 2012, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 29.Castel AD, Magnus M, Peterson J, et al. . Implementing a novel citywide rapid HIV testing campaign in Washington, D.C.: Findings and lessons learned. Public Health Rep 2012;127:422–431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Christopoulos KA, Kaplan B, Dowdy D, et al. . Testing and linkage to care outcomes for a clinician-initiated rapid HIV testing program in an urban emergency department. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2011;25:439–444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Begley E, VanHandel M. Provision of test results and posttest counseling at STD clinics in 24 health departments: U.S., 2007. Public Health Rep 2012;127:432–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Metsch LR, Pereyra M, Messinger S, et al. . HIV transmission risk behaviors among HIV-infected persons who are successfully linked to care. Clin Infect Dis 2008;47:577–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andrews JR, Wood R, Bekker LG, Middelkoop K, Walensky RP. Projecting the benefits of antiretroviral therapy for HIV prevention: The impact of population mobility and linkage to care. J Infect Dis 2012;206:543–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perkins D, Meyerson BE, Klinkenberg D, Laffoon BT. Assessing HIV care and unmet need: Eight data bases and a bit of perseverance. AIDS Care 2008;20:318–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Torian LV, Wiewel EW, Liu KL, Sackoff JE, Frieden TR. Risk factors for delayed initiation of medical care after diagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:1181–1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gardner LI, Metsch LR, Anderson-Mahoney P, et al. . Efficacy of a brief case management intervention to link recently diagnosed HIV-infected persons to care. AIDS 2005;19:423–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Craw JA, Gardner LI, Marks G, et al. . Brief strengths-based case management promotes entry into HIV medical care: Results of the antiretroviral treatment access study-II. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008;47:597–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Molitor F, Waltermeyer J, Mendoza M, et al. . Locating and linking to medical care HIV-positive persons without a history of care: Findings from the California Bridge Project. AIDS Care 2006;18:456–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Olatosi BA, Probst JC, Stoskopf CH, Martin AB, Duffus WA. Patterns of engagement in care by HIV-infected adults: South Carolina, 2004–2006. AIDS 2009;23:725–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hall HI, Gray KM, Tang T, Li J, Shouse L, Mermin J. Retention in care of adults and adolescents living with HIV in 13 U.S. areas. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012;60:77–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Giordano TP, Visnegarwala F, White AC Jr., et al. . Patients referred to an urban HIV clinic frequently fail to establish care: Factors predicting failure. AIDS Care 2005;17:773–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Howe CJ, Cole SR, Napravnik S, Eron JJ. Enrollment, retention, and visit attendance in the University of North Carolina Center for AIDS Research HIV clinical cohort, 2001–2007. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2010;26:875–881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mugavero MJ, Lin HY, Allison JJ, et al. . Failure to establish HIV care: Characterizing the “no show” phenomenon. Clin Infect Dis 2007;45:127–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tobias CR, Cunningham W, Cabral HD, et al. . Living with HIV but without medical care: Barriers to engagement. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2007;21:426–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rumptz MH, Tobias C, Rajabiun S, et al. . Factors associated with engaging socially marginalized HIV-positive persons in primary care. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2007;21:S30–S39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gagliardo C, Murray M, Saiman L, Neu N. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy in youth with HIV: A U.S.-based provider survey. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2013;27:498–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wheeler WH, Ziebell RA, Zabina H, et al. . Prevalence of transmitted drug resistance associated mutations and HIV-1 subtypes in new HIV-1 diagnoses, U.S.-2006. AIDS 2010;24:1203–1212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Agwu AL, Bethel J, Hightow-Weidman LB, et al. . Substantial multiclass transmitted drug resistance and drug-relevant polymorphisms among treatment-naive behaviorally HIV-infected youth. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2012;26:193–196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McKinney RE, Jr, Rodman J, Hu C, et al. . Long-term safety and efficacy of a once-daily regimen of emtricitabine, didanosine, and efavirenz in HIV-infected, therapy-naive children and adolescents: Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol P1021. Pediatrics 2007;120:e416–e423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murphy DA, Belzer M, Durako SJ, Sarr M, Wilson CM, Muenz LR. Longitudinal antiretroviral adherence among adolescents infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2005;159:764–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rudy BJ, Lindsey JC, Flynn PM, et al. . Immune reconstitution and predictors of virologic failure in adolescents infected through risk behaviors and initiating HAART: Week 60 results from the PACTG 381 cohort. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2006;22:213–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Flynn PM, Rudy BJ, Douglas SD, et al. . Virologic and immunologic outcomes after 24 weeks in HIV type 1-infected adolescents receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis 2004;190:271–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ding H, Wilson CM, Modjarrad K, McGwin G, Jr., Tang J, Vermund SH. Predictors of suboptimal virologic response to highly active antiretroviral therapy among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adolescents: Analyses of the reaching for excellence in adolescent care and health (REACH) project. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2009;163:1100–1105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Futterman DC, Peralta L, Rudy BJ, et al. . The ACCESS (Adolescents Connected to Care, Evaluation, and Special Services) project: Social marketing to promote HIV testing to adolescents, methods and first year results from a six city campaign. J Adolesc Health 2001;29:19–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nachega JB, Hislop M, Dowdy DW, et al. . Efavirenz versus nevirapine-based initial treatment of HIV infection: Clinical and virological outcomes in Southern African adults. AIDS 2008;22:2117–2125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Amoroso A, Etienne-Mesubi M, Edozien A, et al. . Treatment outcomes of recommended first-line antiretroviral regimens in resource-limited clinics. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012;60:314–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Markowitz M, Nguyen BY, Gotuzzo E, et al. . Rapid and durable antiretroviral effect of the HIV-1 integrase inhibitor raltegravir as part of combination therapy in treatment-naive patients with HIV-1 infection: Results of a 48-week controlled study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2007;46:125–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Allan PS, Arumainayagam J, Harindra V, et al. . Sustained efficacy of nevirapine in combination with two nucleoside analogues in the treatment of HIV-infected patients: A 48-week retrospective multicenter study. HIV Clin Trials 2003;4:248–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rutstein RM, Gebo KA, Flynn PM, et al. . Immunologic function and virologic suppression among children with perinatally acquired HIV Infection on highly active antiretroviral therapy. Med Care 2005;43:III15–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ryscavage P, Anderson EJ, Sutton SH, Reddy S, Taiwo B. Clinical outcomes of adolescents and young adults in adult HIV care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2011;58:193–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bryden KS, Dunger DB, Mayou RA, Peveler RC, Neil HA. Poor prognosis of young adults with type 1 diabetes: A longitudinal study. Diabetes Care 2003;26:1052–1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Giacomet V, Albano F, Starace F, et al. . Adherence to antiretroviral therapy and its determinants in children with human immunodeficiency virus infection: A multicentre, national study. Acta Paediatr 2003;92:1398–1402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gibb DM, Goodall RL, Giacomet V, McGee L, Compagnucci A, Lyall H. Adherence to prescribed antiretroviral therapy in human immunodeficiency virus-infected children in the PENTA 5 trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2003;22:56–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Belzer ME, Fuchs DN, Luftman GS, Tucker DJ. Antiretroviral adherence issues among HIV-positive adolescents and young adults. J Adolesc Health 1999;25:316–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chandwani S, Koenig LJ, Sill AM, Abramowitz S, Conner LC, D'Angelo L. Predictors of antiretroviral medication adherence among a diverse cohort of adolescents with HIV. J Adolesc Health 2012;51:242–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Buchanan AL, Montepiedra G, Sirois PA, et al. . Barriers to medication adherence in HIV-infected children and youth based on self- and caregiver report. Pediatrics 2012;129:e1244–e1251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Murphy DA, Sarr M, Durako SJ, Moscicki AB, Wilson CM, Muenz LR. Barriers to HAART adherence among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2003;157:249–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Martinez J, Harper G, Carleton RA, et al. . The impact of stigma on medication adherence among HIV-positive adolescent and young adult females and the moderating effects of coping and satisfaction with health care. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2012;26:108–115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tanney MR, Naar-King S, MacDonnel K. Depression and stigma in high-risk youth living with HIV: A multi-site study. J Pediatr Health Care 2012;26:300–305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wagner GJ, Goggin K, Remien RH, et al. . A closer look at depression and its relationship to HIV antiretroviral adherence. Ann Behav Med 2011;42:352–360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Malee K, Williams P, Montepiedra G, et al. . Medication adherence in children and adolescents with HIV infection: Associations with behavioral impairment. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2011;25:191–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Williams PL, Storm D, Montepiedra G, et al. . Predictors of adherence to antiretroviral medications in children and adolescents with HIV infection. Pediatrics 2006;118:e1745–e1757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Naar-King S, Montepiedra G, Nichols S, et al. . Allocation of family responsibility for illness management in pediatric HIV. J Pediatr Psychol 2009;34:187–194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nichols SL, Montepiedra G, Farley JJ, et al. . Cognitive, academic, and behavioral correlates of medication adherence in children and adolescents with perinatally acquired HIV infection. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2012;33:298–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bing EG, Burnam MA, Longshore D, et al. . Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatr 2001;58:721–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Israelski D, Gore-Felton C, Power R, Wood MJ, Koopman C. Sociodemographic characteristics associated with medical appointment adherence among HIV-seropositive patients seeking treatment in a county outpatient facility. Prev Med 2001;33:470–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Palacio H, Shiboski CH, Yelin EH, Hessol NA, Greenblatt RM. Access to and utilization of primary care services among HIV-infected women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999;21:293–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ikard K, Janney J, Hsu LC, et al. . Estimation of unmet need for HIV primary medical care: A framework and three case studies. AIDS Educ Prev 2005;17:26–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Life expectancy of individuals on combination antiretroviral therapy in high-income countries: A collaborative analysis of 14 cohort studies. Lancet 2008;372:293–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.A consensus statement on health care transitions for young adults with special health care needs. Pediatrics 2002;110:1304–1306 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Freed GL, Hudson EJ. Transitioning children with chronic diseases to adult care: Current knowledge, practices, and directions. J Pediatr 2006;148:824–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mellins CA, Brackis-Cott E, Dolezal C, Abrams EJ. Psychiatric disorders in youth with perinatally acquired human immunodeficiency virus infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2006;25:432–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wiener LS, Kohrt BA, Battles HB, Pao M. The HIV experience: Youth identified barriers for transitioning from pediatric to adult care. J Pediatr Psychol 2011;36:141–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cervia JS. Transitioning HIV-infected children to adult care. J Pediatr 2007;150:e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brousseau DC, Owens PL, Mosso AL, Panepinto JA, Steiner CA. Acute care utilization and rehospitalizations for sickle cell disease. JAMA 2010;303:1288–1294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hunt SE, Sharma N. Transition from pediatric to adult care for patients with sickle cell disease. JAMA 2010;304:408–409; author reply 409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fair CD, Sullivan K, Dizney R, Stackpole A. “It's like losing a part of my family”: Transition expectations of adolescents living with perinatally acquired HIV and their guardians. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2012;26:423–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Callahan ST, Cooper WO. Continuity of health insurance coverage among young adults with disabilities. Pediatrics 2007;119:1175–1180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Remien RH, Mellins CA. Long-term psychosocial challenges for people living with HIV: Let's not forget the individual in our global response to the pandemic. AIDS 2007;21:S55–S63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Outlaw AY, Phillips G, 2nd, Hightow-Weidman LB, et al. . Age of MSM sexual debut and risk factors: Results from a multisite study of racial/ethnic minority YMSM living with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2011;25:S23–S29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Committee on Pediatric A, Emmanuel PJ, Martinez J. Adolescents and HIV infection: The pediatrician's role in promoting routine testing. Pediatrics 2011;128:1023–1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Barnes W, D'Angelo L, Yamazaki M, et al. . Identification of HIV-infected 12- to 24-year-old men and women in 15 US cities through venue-based testing. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2010;164:273–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Myers JE, Braunstein SL, Shepard CW, et al. . Assessing the impact of a community-wide HIV testing scale-up initiative in a major urban epidemic. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012;61:23–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bradford JB, Coleman S, Cunningham W. HIV System Navigation: An emerging model to improve HIV care access. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2007;2:S49–S58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fortenberry JD, Martinez J, Rudy BJ, Monte D, Adolescent Trials Network for HIVAI Linkage to Care for HIV-Positive Adolescents: A multisite study of the Adolescent Medicine Trials Units of the Adolescent Trials Network. J Adolesc Health 2012;51:551–556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Agwu AL, Siberry GK, Ellen J, et al. . Predictors of highly active antiretroviral therapy utilization for behaviorally HIV-1-infected youth: Impact of adult versus pediatric clinical care site. J Adolesc Health 2012;50:471–477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cervia JS. Easing the transition of HIV-infected adolescents to adult care. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2013;27:692–696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Reisner SL, Mimiaga MJ, Skeer M, Perkovich B, Johnson CV, Safren SA. A review of HIV antiretroviral adherence and intervention studies among HIV-infected youth. Top HIV Med 2009;17:14–25 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Safren SA, O'Cleirigh C, Tan JY, et al. . A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in HIV-infected individuals. Health Psychol 2009;28:1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. . Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med 2012;367:399–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. . Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med 2010;363:2587–2599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]