Abstract

Objectives: The aim of this study was to assess oncological outcomes in patients treated with pancreaticoduodenectomy for advanced pancreatic head adenocarcinoma after preoperative chemoradiotherapy and to compare these with outcomes in patients treated with surgery alone.

Methods: From 2004 to 2009, patients treated with pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic head adenocarcinoma were included in a retrospective comparative study. Patients with locally advanced adenocarcinoma were treated with preoperative chemoradiotherapy (CRT group) and were compared with those treated with surgery alone (SURG group).

Results: A total of 111 patients were included; these comprised 72 patients in the SURG group and 39 patients in the CRT group. The median follow-up was 21 months. Patients in the CRT group presented with a more advanced tumoral status. Microscopic resection rates were similar in both groups, but nodal status and vascular or lymphatic emboli were lower in the CRT group. At 3 years, the SURG and CRT groups exhibited similar overall (36% and 51%, respectively) and disease-free (35% and 37%, respectively) survival (P = 0.10).

Conclusions: In patients with advanced pancreatic head adenocarcinoma, a good response after preoperative chemoradiotherapy results in a survival rate similar to that in patients treated with surgery alone in whom the initial prognosis is better.

Introduction

Approximately 10 new cases of pancreatic cancer are diagnosed per 100 000 person-years in Western countries.1,2 Surgery remains the standard curative therapy for resectable pancreatic cancer,3 but only 10–15% of patients presenting with pancreatic adenocarcinoma are able to undergo a potentially curative resection. As a result of locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma (LAPA) or distant metastases, the remaining patients are not considered as candidates for resection. The definition of LAPA, comprising both borderline and unresectable tumour, is based on the relationship between the tumour and the coeliac axis (CA) or the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and is identified using computed tomography (CT). The disease is considered unresectable when CT images reveal arterial encasement of either the CA or SMA, or portal vein thrombosis. Patients diagnosed with non-metastatic LAPA, however, are likely to undergo chemoradiotherapy (CRT).4 Downstaging after CRT allows surgical resection in 20% of cases.5–7 Patients with LAPA who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) after CRT have been shown to enjoy survival rates that are twice as high as those in patients treated with CRT alone.8

The aim of this study was to determine the impact of treatment with CRT prior to PD in patients initially diagnosed with LAPA. Oncological outcomes in patients who demonstrated a good response to preoperative CRT and were subsequently treated with PD for LAPA were compared with outcomes in patients treated with surgery alone.

Materials and methods

Population

From 2004 to 2009, patients treated with PD for adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head were included in a retrospective comparative study. Patients with endocrine tumours or ampullary, bile duct or duodenal carcinoma were excluded. All patients underwent thin-section, contrast-enhanced dynamic CT. Patients with distant metastases were excluded. Tumours were considered resectable if there were no distant metastases and no evidence of superior mesenteric vein (SMV) or portal vein abutment, distortion, tumour thrombus or venous encasement with clear fat planes around the CA, hepatic artery and SMA. Tumours were considered borderline resectable in the presence of venous involvement of the SMV or portal vein demonstrating tumour abutment with impingement and narrowing of the lumen, encasement of the SMV or portal vein, but without encasement of the nearby arteries, or abutment of the hepatic artery, without extension to the CA, or abutment of the SMA of >180 ° of the circumference of the vessel wall.9 Tumours that showed SMA encasement of >180 °, any coeliac abutment, unreconstructible SMV or portal vein occlusion or aortic invasion or encasement were considered unresectable. Patients diagnosed with LAPA (borderline or unresectable tumours) were treated with preoperative CRT (CRT group) and were compared with patients treated with surgery alone (SURG group). These patients underwent a pancreatic biopsy to confirm diagnosis and biliary drainage was assessed by endoscopy or surgery in patients with obstructive jaundice. Endpoints included both global and disease-free survival.

Preoperative radiotherapy

In the process of treatment planning, a CT scan was required to define target volumes. The following volumes were based on definitions described by the International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements.10 Gross tumour volume (GTV) was determined during the planning of treatment using slice-by-slice CT scans; the clinical target volume (CTV) was defined as the GTV plus the regional lymph nodes, and the planning target volume 1 (PTV1) included the CTV plus safety margins of 10 mm in all transverse directions and 20 mm craniocaudally to allow for breathing. Following treatment with 45 Gy, the reduced PTV (PTV2) was limited to the GTV and the area between the coeliac trunk and the upper mesenteric artery plus a safety margin of 10 mm in all transverse directions. The prescribed total dose at the reference point (isocentre) of PTV1 was 45 Gy in 25 fractions of 1.8 Gy administered five times per week. During the last segment of treatment, patients received a boost of 14.4 Gy in eight fractions of 1.8 Gy per day, restricted to the initial tumour volume and the coeliac area (PTV2).

Preoperative chemotherapy

During preoperative irradiation, patients received concomitant chemotherapy comprising various fluorouracil-based protocols.11,12 Fluorouracil-based chemotherapy included a 5-fluorouracil (F-FU)–cisplatin protocol (5-FU, 300 mg/m2/day administered as a continuous infusion on days 1–5 in each week; cisplatin, 20 mg/m2/day administered on days 1–5 in weeks 1 and 5 of a 6-week period) and an LV5FU2–cisplatin protocol (folinic acid, 400 mg/m2 on day 1; cisplatin, 50 mg/m2 on day 1; 5-FU, 400 mg/m2 as a bolus infusion followed by 1200 mg/m2 as a continuous infusion on day 1 and 1200 mg/m2 as a continuous infusion on day 2 twice per month).

Patients were treated with chemotherapy alone prior to CRT using protocols based on gemcitabine and cisplatin. Briefly, chemotherapy included gemcitabine alone (1000 mg/m2 once per week for 2 months during the first cycle and for 1 month during additional cycles) and the GEMCIS protocol (gemcitabine, 1000 mg/m2 and cisplatin, 25 mg/m2 administered on days 1, 8, 15 and 28).

Since 2007, patients who might benefit from CRT have been selected using the therapeutic strategy described by the Groupe Coopérateur Multidisciplinaire en Oncologie [GERCOR (Group for Multidisciplinary Cooperation in Oncology)],13 which initially consisted of chemotherapy for ≥3 months. Patients underwent CRT if the disease did not progress during ≥3 months of chemotherapy. This chemotherapy protocol included a combination of gemcitabine and oxaliplatin, GEMOX (gemcitabine, 1000 mg/m2 on day 1, oxaliplatin, 100 mg/m2 on day 2, twice per month).

Response assessment

The therapeutic response was evaluated according to the RECIST (response evaluation criteria in solid tumours) system,14 using a CT scan performed 4 weeks following the end of treatment. Surgical exploration was scheduled in patients in whom either downsizing of the tumour or a decrease in the carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) tumour marker was seen.

Surgical procedure

Surgical exploration was performed 5–6 weeks following CRT completion. The first step in this procedure involved complete exploration of the abdominal cavity to rule out a contraindication for resection (i.e. hepatic or peritoneal metastases). Pancreaticoduodenectomy was performed in accordance with the Whipple procedure. In all cases, the first step consisted of dissection of the SMA. This surgical approach on the SMA was performed using the Kocher manoeuvre.15 To harvest biopsies of tissue in contact with arterial adventitia along the entire length and circumference of the initial LAPA required the artery to be separated from the encasement. During this process, the origin of the SMA may have been exposed and dissected. If all biopsies were negative, then a Whipple procedure was performed; however, if all biopsies were not negative, a palliative bypass was conducted. An en bloc PD with segmental portal vein resection (PVR) was performed in some patients. Portomesenteric reconstruction was performed by direct anastomosis without a prosthetic graft procedure. Specimens were stained by the surgeon on the portal vein (blue), artery (red) and retroportal area (yellow).

Postoperative morbidity was considered according to the classification system of Dindo et al.16 and pancreatic fistulae (PF) were defined as amylase-rich fluid, of more than three times serum concentration, collected from the drain placed intraoperatively in the abdomen from day 3 in accordance with criteria defined by the International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF).17

Statistical analysis

Endpoints consisted of overall and disease-free survival. Variables analysed included age, sex, body mass index (BMI), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, tumour and nodal status (before and after preoperative CRT), artery or vein involvement, and microscopic outcomes (e.g. type of resection, vascular or lymphatic emboli, and perineural invasion).

Survival was defined as the length of time from the beginning of treatment (surgery or CRT) until death. Global and disease-free survival were assessed using the Kaplan–Meier method and were compared using the log-rank test.

Differences between groups were determined by chi-squared or Fisher's exact tests as appropriate. All variables associated with overall or disease-free survival for which P-values of ≤0.10 were found in univariate analysis were considered for multivariable analysis using a logistic regression model.

Results

Population and tumour characteristics

A total of 111 patients were included in this study. Outcome data for 72 patients treated with surgery alone were compared with equivalent data for 39 patients treated with preoperative CRT. The median follow-up was 21 months. Patients treated with preoperative CRT were younger than those treated initially with surgery. Preoperative tumour and nodal statuses were more advanced in the CRT group, which showed a higher rate of artery or vein involvement. One patient with T1 tumour status, who presented preoperatively with a positive nodal status, underwent preoperative CRT. Clinical and tumour characteristics and details of preoperative chemotherapy are reported in Tables 1 and 2. A total of 10 patients underwent chemotherapy for 3 months followed by CRT prior to surgery.

Table 1.

Clinical and tumour characteristics in patients with advanced pancreatic head adenocarcinoma (n = 111)

| SURG group (n = 72) | CRT group (n = 39) | P-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Age | 0.002 | ||

| ≤65 years | 28 (38.9) | 27 (69.2) | |

| >65 years | 44 (61.1) | 12 (30.8) | |

| Sex | 0.059 | ||

| Male | 43 (59.7) | 16 (41.0) | |

| Female | 29 (40.3) | 23 (59.0) | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2a | 0.966 | ||

| ≤23 kg/m2 | 26 (53.1) | 15 (53.6) | |

| >23 kg/m2 | 23 (46.9) | 13 (46.4) | |

| ASA scorea | 0.758 | ||

| 1 | 20 (27.8) | 13 (33.3) | |

| 2 | 44 (61.1) | 21 (53.8) | |

| 3 | 8 (11.1) | 5 (12.8) | |

| Preoperative status | |||

| Tumour statusa | <0.001 | ||

| T1 | 29 (41.4) | 1 (2.6) | |

| T2 | 32 (45.7) | 0 | |

| T3 | 9 (12.9) | 14 (35.9) | |

| T4 | 0 | 24 (61.5) | |

| Nodal status | 0.001 | ||

| N− | 61 (88.4) | 20 (58.8) | |

| N+ | 8 (11.6) | 14 (41.2) | |

| Vein involvementa | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 8 (11.6) | 24 (64.9) | |

| No | 61 (88.4) | 13 (35.1) | |

| Artery involvementa | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 0 | 22 (59.5) | |

| No | 69 (100) | 15 (40.5) | |

| Postoperative status | |||

| Tumour statusa | <0.001 | ||

| T0 | 0 | 5 (12.8) | |

| T1 | 29 (41.4) | 3 (7.7) | |

| T2 | 32 (45.7) | 4 (10.3) | |

| T3 | 9 (12.9) | 27 (69.2) | |

| T4 | 0 | 0 | |

| Resection type | 0.240 | ||

| R0 | 54 (75.0) | 33 (84.6) | |

| R1 | 18 (25.0) | 6 (15.4) | |

| Vascular/lymphatic emboli | 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 32 (55.2) | 7 (20.0) | |

| No | 26 (44.8) | 28 (80.0) | |

| Perineural invasiona | 0.065 | ||

| Yes | 40 (70.2) | 19 (51.4) | |

| No | 17 (29.8) | 18 (48.6) | |

| Nodal status | <0.001 | ||

| N− | 16 (22.2) | 23 (59.0) | |

| N+ | 56 (77.8) | 16 (41.0) |

Missing data.

P-values in bold are significant at P ≤ 0.01.

SURG group, surgery-only group; CRT group, preoperative chemoradiotherapy group; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists.

Table 2.

Preoperative chemotherapy in patients with advanced pancreatic head adenocarcinoma (n = 39)

| Preoperative chemotherapy = 39) | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| 5-Fluorouracil + cisplatin | 3 | 7.7 |

| LV5FU2 + cisplatin | 8 | 20.5 |

| Gemcitabine | 4 | 10.3 |

| Gemcitabine + cisplatin | 14 | 35.9 |

| Gemcitabine + oxaliplatin | 10 | 25.6 |

Operative procedure characteristics

During the Whipple procedure, the rate of vein resection was higher in the CRT group (Table 3). Only one artery resection was conducted in the CRT group and none were conducted in the SURG group. Pancreatic tissue was considered fibrous in 41% and 73% of patients in the SURG and preoperative CRT groups, respectively. This difference was not significant.

Table 3.

Treatment and postoperative course characteristics in patients with advanced pancreatic head adenocarcinoma treated with pancreaticoduodenectomy (n = 111)

| SURG group (n = 72) | CRT group (n = 39) | P-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Vein resectiona | 0.041 | ||

| Yes | 22 (31.4) | 20 (51.3) | |

| No | 48 (68.6) | 19 (48.7) | |

| Artery resection | 0.351 | ||

| Yes | 0 | 1 (2.6) | |

| No | 72 (100) | 38 (97.4) | |

| Extensive nodal resection (N2) | 0.420 | ||

| Yes | 5 (7.0) | 1 (2.6) | |

| No | 66 (93.0) | 38 (97.4) | |

| Pancreatic anastomosis | 1.000 | ||

| Gastric | 8 (11.1) | 4 (10.3) | |

| Jejunal | 64 (88.9) | 35 (89.7) | |

| Pancreas appearancea | 0.243 | ||

| Normal | 9 (17.0) | 3 (9.1) | |

| Soft | 15 (28.3) | 6 (18.2) | |

| Fibrous | 29 (41.4) | 24 (72.7) | |

| Pancreatic fistula | 0.072 | ||

| Yes | 20 (27.8) | 5 (12.8) | |

| No | 52 (72.2) | 34 (87.2) | |

| Biliary fistula | 1.000 | ||

| Yes | 4 (5.6) | 2 (5.1) | |

| No | 68 (94.4) | 37 (94.9) | |

| Gut fistula | 1.000 | ||

| Yes | 1 (1.4) | 0 | |

| No | 71 (98.6) | 39 (100) | |

| Sepsis/collection | 0.117 | ||

| Yes | 16 (22.2) | 4 (10.3) | |

| No | 56 (77.8) | 35 (89.7) | |

| Postoperative haemorrhage | 0.418 | ||

| Yes | 6 (8.3) | 1 (2.6) | |

| No | 66 (91.7) | 38 (97.4) | |

| Postoperative treatment | <0.001 | ||

| None | 23 (33.3) | 26 (74.3) | |

| Chemotherapy | 37 (53.6) | 9 (25.7) | |

| Radiochemotherapy | 9 (13.0) | 0 |

Missing data.

P-values in bold are significant at P ≤ 0.01.

SURG group, surgery-only group; CRT group, preoperative chemoradiotherapy group.

Postoperative complications

No difference in surgical morbidity was detected between the two groups. However, rates of PF were 28% in the SURG group and 13% in the CRT group. In line with the rate of fibrous pancreatic tissue, this difference in the incidence of PF was not significant (P = 0.07).

Histology

Microscopic analysis of the specimen revealed that the rate of positive node and vascular or lymphatic emboli was lower in the CRT group than in the SURG group. Tumours were sterilized in five patients who received preoperative CRT. Patients in the CRT group exhibited less perineural invasion, but this difference was not significant. Rates of microscopic negative-margin resection were similar in both groups (Table 3).

Overall and disease-free survival

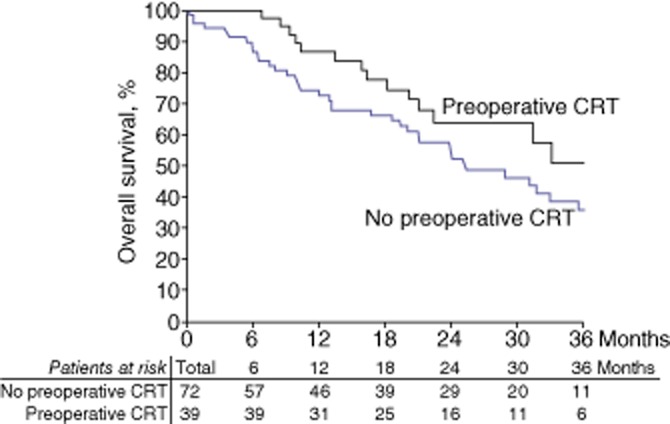

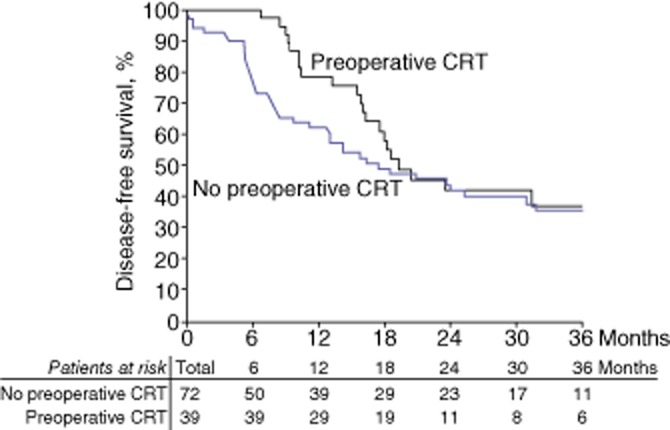

No significant difference was detected between the two groups in either overall survival or disease-free survival (31% and 19%, respectively, in the entire cohort). At 3 years, overall survival rates in the SURG and preoperative CRT groups were 36% and 51%, respectively (P = 0.096); disease-free survival rates in the SURG and preoperative CRT groups were 35% and 37%, respectively (P = 0.249) (Figs 1, 2).

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves showing overall survival in 111 patients subjected to pancreaticoduodenectomy for advanced pancreatic head adenocarcinoma, of whom 39 were treated with preoperative chemoradiotherapy (CRT) and 72 were treated with surgery alone

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves showing disease-free survival in 111 patients subjected to pancreaticoduodenectomy for advanced pancreatic head adenocarcinoma, of whom 39 were treated with preoperative chemoradiotherapy (CRT) and 72 were treated with surgery alone

Treatment characteristics (e.g. preoperative radiotherapy and resection type) and nodal status did not influence overall survival. By contrast, patient characteristics (e.g. age and ASA score) and tumour characteristics (e.g. vascular or lymphatic emboli and tumour status) did influence overall survival. Based on multivariate analysis, independent factors for overall survival were patient age of >65 years [odds ratio (OR) 1.98, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.01–3.90; P = 0.049] and low degree of tumour differentiation (OR 3.09, 95% CI 1.16–8.18; P = 0.024).

The only factors associated with disease-free survival were the tumour characteristics of low differentiation and vascular or lymphatic emboli. Results of the multivariate analysis indicated that the independent factors associated with disease-free survival were low degree of tumour differentiation (OR 3.26, 95% CI 1.27–8.41; P = 0.014) and vascular or lymphatic emboli (OR 2.05, 95% CI 1.13–3.69; P = 0.018).

Discussion

Radical surgery, which achieves tumour-free margins (R0), represents the only potentially curative option for patients diagnosed with adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head.3 Unfortunately, fewer than 20% of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma have potentially resectable tumours. For patients with unresectable lesions, the standard of care consists of chemoradiation with concurrent 5-FU.12 This regimen often includes cisplatin6,7,18 or, more recently, concurrent gemcitabine,19 which may be used in combination with oxaliplatin.20 A few studies have demonstrated that CRT will occasionally downstage locally advanced unresectable pancreatic tumours to allow for surgical resection.5–7,21 In agreement with a recent review,22 the present results demonstrate that a good tumour response to preoperative CRT for adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head results in better overall survival than surgery alone in patients who present with a better prognosis initially. This difference was not significant in the present study, probably as a result of the small size of the study population. The retrospective nature of this study, the heterogeneity of treatment and the small population size resulted in decreased statistical power for the present analyses. As demonstrated in clinical studies of CRT, one potential disadvantage of preoperative CRT is that it is associated with increased perioperative morbidity and mortality.7,18 However, in the present study, preoperative CRT did not increase perioperative morbidity, particularly PF, or mortality, as has been previously reported elsewhere.23

This study emphasizes the impact of downstaging LAPA using CRT. In this series, a high rate of R0 resection was noted in the preoperative CRT group (85%). This procedure involved an extended resection that required portal vein resection and reconstruction in half of these patients. In series that have included only patients with primarily unresectable pancreatic cancer, rates of R0/total resections ranged from 57% to 100%.22 This proportion is remarkable in comparison with the rate of R0 resection reported in the present study and is in agreement with rates recently reported in the literature, which vary from 25% to 84% in patients with primarily resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma.24–26 Additionally, the rate of positive nodal disease following treatment was lower in the preoperative CRT group than in the SURG group, which represents a reversal of the nodal status observed in CT scans prior to treatment. Survival has been shown to be directly influenced by nodal status.27–29 In the present study, nodal status did not affect survival, but the presence of fewer vascular or lymphatic emboli influenced disease-free survival. The degree of tumour differentiation and patient age impacted upon overall survival.

In the present study, patients diagnosed with LAPA who underwent PD as a result of downstaging subsequent to CRT demonstrated overall and disease-free survival comparable with those in resectable patients treated with surgery alone. The present series demonstrated a reversal of the expected trend; patients with early-stage resectable carcinoma survived longer than patients with more advanced regional disease. These findings are similar to results reported in other studies.18,23,30 In a previous study, this group reported that approximately 20% of patients treated with CRT for LAPA underwent surgical resection.5 Although this subset of patients was selected among patients who initially presented with a poor prognosis, the entire group responded positively to the preoperative treatment. Non-responders, or patients with metastases, underwent palliative care. In a series of resected, early-stage pancreatic tumours, approximately 20% of metastases occurred within 3 months following surgery, resulting in a negative impact on survival; therefore, the exclusion of these patients should be considered when interpreting the results.31 The present authors hypothesize, however, that the downstaging and downsizing of the tumour are responsible for this effect on survival, and the significant reduction of nodal involvement is the most obvious parameter with which to support this hypothesis. Moreover, only one in four patients in the CRT group underwent postoperative chemotherapy, whereas over half of the patients in the SURG group underwent chemotherapy following surgery. Treatment with postoperative chemotherapy in patients who have received preoperative CRT may decrease the distant recurrence rate and more significantly increase overall and disease-free survival.

Although surgery remains the standard curative therapy for resectable pancreatic cancer, very similar rates of survival were observed in the two treatment groups assessed in this study, which is in agreement with previous studies.18,23,30 Although it is important to note that the patients who underwent PD after preoperative CRT represented a selected subset of patients, this observation may suggest a defect in selecting patients who have been treated with radical surgery alone. Moreover, the survival of patients in the CRT group was estimated from the beginning of preoperative treatment, whereas the survival of patients in the SURG group was estimated from the time of surgery and this difference may have led to a time-associated bias in the assessment of overall survival. Additionally, 13–21% of patients in whom preoperative thin-section, contrast-enhanced dynamic CT indicated resectable tumour were found to show contraindications for Whipple surgery during the laparotomy for local progression, carcinomatosis or metastasis.32,33 These patients were not included in the present study, which leads to another bias in selection. Finally, Massucco and co-workers demonstrated that primarily resected patients who were not treated with adjuvant therapy exhibited the same median survival as unresectable patients treated with CRT alone.23 Golcher et al. suggested that preoperative CRT may increase survival in patients with resectable disease.30 Because distant metastases determine prognosis and develop frequently as the disease progresses, this strategy may be beneficial to surgeons selecting patients for surgery and may help to avoid early recurrences.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Smigal C, et al. Cancer statistics, 2006. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:106–130. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.2.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black RJ, Bray F, Ferlay J, Parkin DM. Cancer incidence and mortality in the European Union: cancer registry data and estimates of national incidence for 1990. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:1075–1107. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(96)00492-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wagner M, Redaelli C, Lietz M, Seiler CA, Friess H, Buchler MW. Curative resection is the single most important factor determining outcome in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2004;91:586–594. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White RR, Reddy S, Tyler DS. The role of chemoradiation therapy in locally advanced pancreatic cancer. HPB. 2005;7:109–113. doi: 10.1080/13651820510016506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sa Cunha A, Rault A, Laurent C, Adhoute X, Vendrely V, Bellannee G, et al. Surgical resection after radiochemotherapy in patients with unresectable adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201:359–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.White R, Lee C, Anscher M, Gottfried M, Wolff R, Keogan M, et al. Preoperative chemoradiation for patients with locally advanced adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Ann Surg Oncol. 1999;6:38–45. doi: 10.1007/s10434-999-0038-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wanebo HJ, Glicksman AS, Vezeridis MP, Clark J, Tibbetts L, Koness RJ, et al. Preoperative chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgical resection of locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Arch Surg. 2000;135:81–87. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turrini O, Viret F, Moureau-Zabotto L, Guiramand J, Moutardier V, Lelong B, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiation and pancreaticoduodenectomy for initially locally advanced head pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:1306–1311. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Callery MP, Chang KJ, Fishman EK, Talamonti MS, Traverso LW, Linehan DC. Pretreatment assessment of resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: expert consensus statement. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:1727–1733. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0408-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements. Prescribing, recording and reporting photo beam therapy. ICRU report 50: Bethesda, MD. 1993. International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements.

- 11.Moertel CG, Frytak S, Hahn RG, O'Connell MJ, Reitemeier RJ, Rubin J, et al. Therapy of locally unresectable pancreatic carcinoma: a randomized comparison of high dose (6000 rads) radiation alone, moderate dose radiation (4000 rads + 5-fluorouracil), and high dose radiation + 5-fluorouracil: the Gastrointestinal Tumour Study Group. Cancer. 1981;48:1705–1710. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19811015)48:8<1705::aid-cncr2820480803>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gastrointestinal Tumour Study Group. Treatment of locally unresectable carcinoma of the pancreas: comparison of combined-modality therapy (chemotherapy plus radiotherapy) to chemotherapy alone. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1988;80:751–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huguet F, Andre T, Hammel P, Artru P, Balosso J, Selle F, et al. Impact of chemoradiotherapy after disease control with chemotherapy in locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma in GERCOR phase II and III studies. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:326–331. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.5663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumours. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonnichon P, Rossat-Mignod JC, Corlieu P, Aaron C, Yandza T, Chapuis Y. Surgical approach to the superior mesenteric artery by the Kocher manoeuvre: anatomy study and clinical applications. Ann Vasc Surg. 1987;1:505–508. doi: 10.1016/S0890-5096(06)60743-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–213. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, et al. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Snady H, Bruckner H, Cooperman A, Paradiso J, Kiefer L. Survival advantage of combined chemoradiotherapy compared with resection as the initial treatment of patients with regional pancreatic carcinoma. An outcomes trial. Cancer. 2000;89:314–327. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000715)89:2<314::aid-cncr16>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loehrer PJ, Feng Y, Cardenes H, Wagner L, Brell JM, Cella D, et al. Gemcitabine alone versus gemcitabine plus radiotherapy in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer: an eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4105–4112. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.8904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Louvet C, Labianca R, Hammel P, Lledo G, Zampino MG, Andre T, et al. Gemcitabine in combination with oxaliplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: results of a GERCOR and GISCAD phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3509–3516. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ammori JB, Colletti LM, Zalupski MM, Eckhauser FE, Greenson JK, Dimick J, et al. Surgical resection following radiation therapy with concurrent gemcitabine in patients with previously unresectable adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:766–772. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(03)00113-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morganti AG, Massaccesi M, La Torre G, Caravatta L, Piscopo A, Tambaro R, et al. A systematic review of resectability and survival after concurrent chemoradiation in primarily unresectable pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:194–205. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0762-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Massucco P, Capussotti L, Magnino A, Sperti E, Gatti M, Muratore A, et al. Pancreatic resections after chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced ductal adenocarcinoma: analysis of perioperative outcome and survival. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:1201–1208. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Esposito I, Kleeff J, Bergmann F, Reiser C, Herpel E, Friess H, et al. Most pancreatic cancer resections are R1 resections. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:1651–1660. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-9839-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verbeke CS. Resection margins and R1 rates in pancreatic cancer – are we there yet? Histopathology. 2008;52:787–796. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van den Broeck A, Sergeant G, Ectors N, van Steenbergen W, Aerts R, Topal B. Patterns of recurrence after curative resection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:600–604. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Breslin TM, Hess KR, Harbison DB, Jean ME, Cleary KR, Dackiw AP, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: treatment variables and survival duration. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:123–132. doi: 10.1007/s10434-001-0123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Lillemoe KD, Sohn TA, Campbell KA, Sauter PK, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with or without distal gastrectomy and extended retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy for periampullary adenocarcinoma, part 2: randomized controlled trial evaluating survival, morbidity, and mortality. Ann Surg. 2002;236:355–366. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200209000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tran KT, Smeenk HG, van Eijck CH, Kazemier G, Hop WC, Greve JW, et al. Pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy versus standard Whipple procedure: a prospective, randomized, multicentre analysis of 170 patients with pancreatic and periampullary tumours. Ann Surg. 2004;240:738–745. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000143248.71964.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Golcher H, Brunner T, Grabenbauer G, Merkel S, Papadopoulos T, Hohenberger W, et al. Preoperative chemoradiation in adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. A single-centre experience advocating a new treatment strategy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:756–764. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sperti C, Pasquali C, Piccoli A, Pedrazzoli S. Recurrence after resection for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. World J Surg. 1997;21:195–200. doi: 10.1007/s002689900215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maire F, Sauvanet A, Trivin F, Hammel P, O'Toole D, Palazzo L, et al. Staging of pancreatic head adenocarcinoma with spiral CT and endoscopic ultrasonography: an indirect evaluation of the usefulness of laparoscopy. Pancreatology. 2004;4:436–440. doi: 10.1159/000079617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barbier L, Turrini O, Gregoire E, Viret F, Le Treut YP, Delpero JR. Pancreatic head resectable adenocarcinoma: preoperative chemoradiation improves local control but does not affect survival. HPB. 2011;13:64–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2010.00245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]