Abstract

Introduction

Major abdominal surgery leads to a postoperative systemic inflammatory response, making it difficult to discriminate patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome from those with a beginning postoperative infectious complication. At present, physicians have to rely on their clinical experience to differentiate between the two. Pancreatic stone protein (PSP) and pancreatitis-associated protein (PAP), both secretory proteins produced by the pancreas, are dramatically increased during pancreatic disease and have been shown to act as acute-phase proteins. Increased levels of PSP have been detected in polytrauma patients developing sepsis and PSP has shown a high diagnostic accuracy in discriminating the severity of peritonitis and in predicting death in intensive care unit patients. However, the prognostic value of PSP/PAP for infectious complications among patients undergoing major abdominal surgery is unknown.

Methods and analysis

160 patients undergoing major abdominal surgery will be recruited preoperatively. On the day before surgery, baseline blood values are attained. Following surgery, daily blood samples for measuring regular inflammatory markers (c-reactive protein, procalcitonin, interleukin-6, tumour necrosis factor-α and leucocyte counts) and PSP/PAP will be acquired. PSP/PAP will be measured using a validated ELISA developed in our research laboratory. Patient's discharge marks the end of his/her trial participation. Complication grade including mortality and occurrence of infectious postoperative complications according to validated diagnostic criteria will be correlated with PSP/PAP values. Total intensive care unit days and total length of stay will be recorded as further outcome parameters.

Ethics and dissemination

The PSP trial is a prospective monocentric cohort study evaluating the prognostic value of PSP and PAP for postoperative infectious complications. In addition, a comparison with established inflammatory markers in patients undergoing major abdominal surgery will be performed to help evaluate the role of these proteins in predicting and diagnosing infectious and other postoperative complications.

Institution ethics board approval ID

KEKZH-Nr. STV 11-2009.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01258179.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Assessment of the novel sepsis biomarkers pancreatic stone protein/pancreatitis-associated protein (PSP/PAP) in an abdominal surgical study population.

Comparison of PSP/PAP to other acute-phase reaction proteins, regularly measured in surgical study populations.

Evaluation of ability of PSP/PAP to predict infectious complications in patients undergoing major abdominal surgery.

Evaluation of ability of PSP/PAP to predict postoperative sepsis in patients undergoing major abdominal surgery (independently and in comparison with other inflammatory markers).

External validation of PSP/PAP as a sepsis marker in an independent, prospective patient cohort.

Limited ability to generalise to other surgical or medical patient populations.

Limited ability to determine role in guiding treatment decisions.

Non-blinded, non-randomised single-centre observational cohort study.

Background and current knowledge

The acute-phase reaction is a systemic, non-specific response of the organism to acute inflammation and infection, which also occurs after surgery, and is also associated with changes in the plasma protein profile.1 Endothelial cells, fibroblasts and inflammatory cells such as macrophages secrete endogenous immune mediators in the damaged tissue, such as interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-6, interferon-γ and tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). In the presence of cortisol, this results in the induction of synthesis of various acute-phase proteins stemming from the liver.2 These include c-reactive protein (CRP), serum amyloid A (SAA), fibrinogen and the complement C3.3 These proteins can be used as outcome measures of the acute-phase reaction3 and have been established in clinical practice. Prolonged increase of acute-phase proteins has been shown to be predictive for postoperative infections and septic complications.4 5 In addition, studies have shown that inflammatory markers such as TNF, IL-10 and IL-6 play an important role in the pathogenesis of postoperative systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS).6 However, acute-phase proteins are not synthesised in the liver. It has been shown that the pancreas increases the production of pancreatic secretory proteins such as pancreatitis-associated protein (PAP) and the pancreatic stone protein/regenerating protein (PSP/reg), known as secretory stress proteins (SSPs).7 8 In previous work, our group has shown an increased production and secretion of SSPs in stress induction of a murine pancreatitis-model (WBN/Kob rat).9 10 Another group was able to demonstrate a correlation between the course of pancreatitis and the induction of pancreatic SSPs.11 However, it has also been demonstrated that PAP and PSP are secreted in other organs, such as the small intestine.12 13 PAP was increased under inflammatory conditions of the small intestine, especially in coeliac disease.13 More recently, it was demonstrated that PAP and its associated metalloproteinases are involved in wound healing processes.14

In a clinical study in polytrauma patients, a significant increase of PSP was observed in those patients who developed infections or sepsis.15 The same study showed that PSP binds and activates neutrophils, thus acting as an acute-phase protein. The concept that PSP is an early marker of sepsis was further confirmed in subsequent studies on patient populations admitted to the ICU.16–18

Therefore, it seems clear that PAP and PSP play an important role in various inflammatory events, not only in pancreatitis but also in sepsis subsequent to other inflammatory diseases. However, until now, no perioperative study exists, which looks at the value of these proteins and their role as postoperative inflammatory serum markers following major abdominal surgery. In addition, differentiating between a simple inflammatory response and a true infectious complication following abdominal surgery still remains a challenge in clinical practice. Here, PAP and PSP/reg may provide valuable information and aid in differentiating between both events in the postoperative setting.

Methods and study design

The PSP study is a prospective, monocentric cohort study evaluating the role of PSP and PAP as new markers for postoperative infectious complications following abdominal surgery. Our study population will consist of patients undergoing liver (n=30), pancreas (n=30), upper gastrointestinal tract (n=30) and lower gastrointestinal tract (n=30) surgery as well as patients undergoing emergency abdominal procedures (n=20) and patients undergoing combined renal/pancreas transplantation (n=10). A total of 160 patients will be recruited. To ensure adequate data quality, an interim analysis will be performed once 80 patients have been recruited. A power analysis will be performed based on the actual and precise data collected. At interim analysis, the potential need to modify the sample size will be investigated. If the external data monitoring committee suggests any changes based on these calculations, the principal investigators will decide on the feasibility of the potential changes and submit a formal addendum to the ethics committee. Unless first approved by the local ethics committee, no changes will be made to the protocol or study design. Any changes to the protocol approved by the ethics committee will be updated at clinicaltrials.gov [NCT01258179].

Study objectives and endpoints

Study objectives

To determine serum levels of PAP and PSP/reg attained from venous samples of patients undergoing major abdominal surgery.

To determine an association between PSP/PAP expression and current, routinely measured inflammatory markers (CRP, procalcitonin, TNF-α, IL-6, white cell count and thrombocyte count) and compare these with regard to predicting postoperative complications.

To determine whether PSP/PAP levels correlate with postoperative infectious complications and general postoperative complications as graded by the validated Clavien-Dindo classification for postoperative surgical complications.19

To determine whether PSP/PAP can be used as a predictive marker for postoperative infectious complications and sepsis.

Endpoints

Primary endpoint

Secondary endpoints

Correlation/comparison of PSP/PAP expression values to current markers of inflammation in patients undergoing major abdominal surgery.

Association of PSP/PAP expression values with overall complication grade according to the Clavien-Dindo score for postoperative complications which includes mortality.

Association of PSP/PAP expression values with overall postoperative infectious complications and the correlation between PSP/PAP expression values and changes/alterations to management of postoperative complications.

Value of serum PSP/PAP levels at time of admission to intensive care unit (ICU) to predict infection/sepsis outcome during postoperative course including total ICU days and total length of stay.

Inclusion criteria

Age >18 years.

Patients scheduled for abdominal surgery including liver, pancreas, upper gastrointestinal tract, lower gastrointestinal tract procedures, patients planned for combined kidney-renal transplantation as well as patients requiring emergency abdominal procedures.

Patients able to provide informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

Age <18 years.

Patients unable to provide informed consent.

SIRS and sepsis criteria

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome

Fever ≥38.0°C or hypothermia ≤36.0°C measured rectal, intravascular or within the bladder.

Tachycardia ≥90/min.

Tachypnoea ≥20/min or hyperventilation (measured via arterial blood gas analysis showing PaCO2 ≤4.3 kPa/33 mm Hg).

Leukocytosis ≥12 000/mm3 or leucopenia ≤4000/mm3 or ≥10% of immature neutrophils on differential blood analysis.

At least two of the aforementioned criteria must be fulfilled to diagnose SIRS.20 21

Sepsis

Proven microbiological infection (eg, positive blood cultures).

At least two of the above mentioned SIRS criteria.

Data collection and statistical methodology

Data collection

Patients will be recruited on the day before surgery or on admission for emergency abdominal surgery. They will be evaluated for inclusion criteria and informed about the study as well as the possibility of study participation. Once the informed consent form has been read, understood and signed, baseline blood samples will be obtained and sent in for routine as well as separate analysis of PSP/PAP levels. Following surgery, daily blood samples will be obtained and analysed for the sample values. Blood samples will be marked with patient's names, date of birth and date of sample extraction for identification purposes during transportation to our laboratory. However, following arrival of the blood sample in our laboratory and prior to processing, all patients’ information will be modified to allow for anonymous biobanking and study participation.

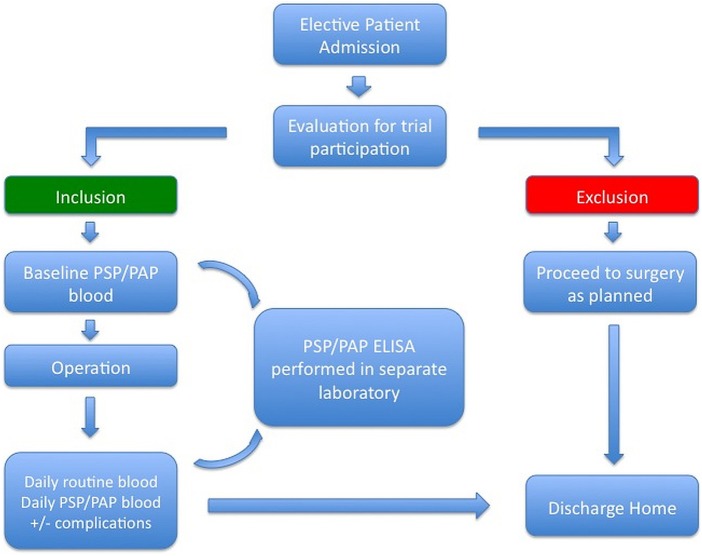

If postoperative complications occur, they will be documented in the patient's chart by the treating physicians according to the Clavien-Dindo classification of postoperative complications, as is usual clinical practice in our department. In the presence of infectious complications, evaluation for the presence of SIRS/sepsis according to the aforementioned criteria will occur. If criteria for SIRS are fulfilled, blood cultures will be taken according to the aforementioned guidelines to document septic complications. Patient demographic data will be collected via chart analysis by the principal investigator and other participating investigators and will be documented in a central, prospective database (see online supplementary file 1). Study participation ends with patient discharge (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patient recruitment and study participation. PAP, pancreatitis-associated protein; PSP, pancreatic stone protein.

No commercial analysis kit exists for PSP/PAP analysis. Therefore, separate blood samples will be sent to our in-house research team, where direct protein detection through a validated ELISA is performed.22 Excessive material will be stored and catalogued in a central, anonymous biobank (−80°C fridge).

Statistical methods

We will compare continuous variables with the Student t, Mann-Whitney U, one-way analysis of variance and Kruskal-Wallis tests. Differences among proportions derived from categorical data will be assessed using the Fisher's exact or the Pearson χ2 tests where appropriate. Paired statistics will be used where appropriate. All p values will be two-sided and statistical significance will be if p≤0.05. Sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, positive likelihood ratio, negative likelihood ratio, Yuden's index, diagnostic OR and the receiver operator characteristic curve will be calculated. Where appropriate, Kaplan-Meier survival curves and survival comparison using the log-rank test will be performed. Where appropriate, data will be presented as mean (SD), median (IQR) and ORs (95% CI). We will duplicate the blood samples to analyse reproducibility of PSP/PAP measurements and assess the variability by the Pearson's correlation coefficient. We will use SPSS Statistics V.20 (SPSS: an IBM company, Chicago Illinois, 2011) to perform statistical analysis.

Study site

Department of Surgery, University Hospital Zurich, Raemistrasse 100, CH-8091 Zurich, Switzerland

Study starting and estimated completion date

First patient recruitment for this study occurred following the approval by the local ethics committee in February 2011. Expected study completion date will be December 2014.

Ethics

This study is conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and ‘good clinical practice’ guidelines.

Discussion

Until now, no perioperative studies exist looking at the value and role of PAP and PSP/reg as postoperative inflammatory serum markers in patients having major abdominal surgery, although it has been demonstrated that PSP/PAP play an important role in various inflammatory events models.7 9 10 13 14 In addition, many serum markers have been studied in the hope of discovering new biomarkers, which will aid in recognising sepsis.3–5 23 However, until now no single test exists, which enables physicians to diagnose sepsis and they, therefore, still have to rely on a combination of physical examination and laboratory findings as well as clinical judgement, thereby potentially delaying adequate treatment. This is crucial, as septic complications following abdominal surgery are treacherous and require early diagnosis and aggressive management due to their high rate of morbidity and mortality.24 25 Here, PSP/PAP may serve as novel markers for postoperative sepsis, to facilitate early diagnosis of sepsis and thereby hopefully directing resources to those patients at highest risk for death due to septic complications.

Conclusion

The PSP study is a prospective, monocentric cohort study evaluating the role of PSP and PAP as new markers for postoperative infectious complications following abdominal surgery.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Martha Bain, Udo Ungethuem, Theresia Reding Graf and Tanja Jakob for their excellent technical assistance. The authors would also like to thank the Gebert Rüf Foundation Switzerland, for funding their study (GRS-014/12).

Footnotes

Contributors: OMF and CEO drafted the manuscript and contributed equally to this work. CEO and RG designed the study protocol in its previous version. DAR performed the study design and calculation of the sample size for the study. All other authors participated in the design of the study. All authors were involved in editing the manuscript and read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The study is supported by the Gebert Rüf Foundation, Switzerland (GRS-014/12).

Competing interests: RG is the inventor and the University of Zurich owns the patent for PSP/reg as a marker of sepsis.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Commission of the Canton of Zurich, Switzerland via a peer-reviewed process (Kantonale Ethikkommission Zurich; Institution Ethics Board Approval ID: KEKZH-Nr. STV 11-2009).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: We intend to publish all scientific results resulting from this research project in peer-reviewed journals and to present project data at international and national scientific meetings and congresses.

References

- 1.Gressner AM TL. Proteinstoffwechsel. Lehrbuch der Klinischen Chemie und Pathobiochemie. New York: Schattauer Stuttgart, 1989:152 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andus T, Heinrich PC, Castell JC, et al. [Interleukin-6: a key hormone of the acute phase reaction]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 1989;114:1710–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Staehler M, Hammer C, Meiser B, et al. Procalcitonin: a new marker for differential diagnosis of acute rejection and bacterial infection in heart transplantation. Transplant Proc 1997;29:584–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oberhoffer M, Karzai W, Meier-Hellmann A, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of various markers of inflammation for the prediction of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-6 in patients with sepsis. Crit Care Med 1999;27:1814–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Welsch T, Muller SA, Ulrich A, et al. C-reactive protein as early predictor for infectious postoperative complications in rectal surgery. Int J Colorectal Dis 2007;22:1499–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dimopoulou I, Armaganidis A, Douka E, et al. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF alpha) and interleukin-10 are crucial mediators in post-operative systemic inflammatory response and determine the occurrence of complications after major abdominal surgery. Cytokine 2007;37:55–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kemppainen E, Sand J, Puolakkainen P, et al. Pancreatitis associated protein as an early marker of acute pancreatitis. Gut 1996;39:675–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iovanna J, Orelle B, Keim V, et al. Messenger RNA sequence and expression of rat pancreatitis-associated protein, a lectin-related protein overexpressed during acute experimental pancreatitis. J Biol Chem 1991;266:24664–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bimmler D, Schiesser M, Perren A, et al. Coordinate regulation of PSP/reg and PAP isoforms as a family of secretory stress proteins in an animal model of chronic pancreatitis. J Surg Res 2004;118:122–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graf R, Schiesser M, Scheele GA, et al. A family of 16-kDa pancreatic secretory stress proteins form highly organized fibrillar structures upon tryptic activation. J Biol Chem 2001;276:21028–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iovanna JL, Keim V, Nordback I, et al. Serum levels of pancreatitis-associated protein as indicators of the course of acute pancreatitis. Multicentric Study Group on Acute Pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 1994;106:728–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masciotra L, Lechene de la Porte P, Frigerio JM, et al. Immunocytochemical localization of pancreatitis-associated protein in human small intestine. Dig Dis Sci 1995;40:519–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carroccio A, Iovanna JL, Iacono G, et al. Pancreatitis-associated protein in patients with celiac disease: serum levels and immunocytochemical localization in small intestine. Digestion 1997;58:98–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li L, Bachem MG, Zhou S, et al. Pancreatitis-associated protein inhibits human pancreatic stellate cell MMP-1 and -2, TIMP-1 and -2 secretion and RECK expression. Pancreatology 2009;9: 99–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keel M, Harter L, Reding T, et al. Pancreatic stone protein is highly increased during posttraumatic sepsis and activates neutrophil granulocytes. Crit Care Med 2009;37:1642–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gukasjan R, Raptis DA, Schulz HU, et al. Pancreatic stone protein predicts outcome in patients with peritonitis in the ICU. Crit Care Med 2013;41:1027–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boeck L, Graf R, Eggimann P, et al. Pancreatic stone protein: a marker of organ failure and outcome in ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chest 2011;140:925–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Que YA, Delodder F, Guessous I, et al. Pancreatic stone protein as an early biomarker predicting mortality in a prospective cohort of patients with sepsis requiring ICU management. Crit Care 2012;16:R114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004;240:205–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gesellschaft DS. Leitlinien Sepsis. Secondary Leitlinien Sepsis 2010. http://www.sepsis-gesellschaft.de/cgi-bin/WebObjects/DsgCMS.woa/2/wo/2ewkjkZfYnXP78ZyUCxIGM/2.1.MainWrapper.25.1.1.0.3.1.1.3.7.0.0.

- 21.[No authors listed] American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference: definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Crit Care Med 1992;20:864–74 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scherr A, Graf R, Bain M, et al. Pancreatic stone protein predicts positive sputum bacteriology in exacerbations of COPD. Chest 2013;143:379–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sankar V, Webster NR. Clinical application of sepsis biomarkers. J Anesth 2013;27:269–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore LJ, Moore FA, Todd SR, et al. Sepsis in general surgery: the 2005-2007 national surgical quality improvement program perspective. Arch Surg 2010;145:695–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore LJ, Moore FA, Jones SL, et al. Sepsis in general surgery: a deadly complication. Am J Surg 2009;198:868–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.