Abstract

This study aimed to investigate whether corneal nerve and corneal stem/progenitor cells are altered in insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I-) treated individuals with diabetes. A group consisting of db/db mice with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) and a wild-type group were assessed by neural and corneal stem/progenitor cell markers immunostaining and real-time PCR. Moreover, the expression of corneal nerve and stem/progenitor cell markers was examined in IGF-1-treated diabetic mice. Compared with a normal cornea, swelling and stratification of the corneal epithelium were noted in db/db mice. Beta-III tubulin immunostaining revealed that the corneal subbasal plexuses in diabetic mice were thinner with fewer branches. mRNA expression levels of Hes1, Keratin15, and p75 (corneal stem/progenitor cell markers) and the intensity and number of positive cells of Hes1 and Keratin19 immunostaining diminished in the diabetic corneas. Compared with the subbasal nerve density in the normal group, a decrease in the diabetic group was observed, whereas the corneal subbasal nerve density increased in IGF-1-treated diabetic group. The decreased expression of Hes1 and Keratin19 was prevented in IGF-1-treated diabetic group. Our data suggest that corneal nerve and stem/progenitor cells are altered in type 2 DM, and IGF-I treatment is capable of protecting against corneal damage in diabetes.

1. Introduction

Corneolimbal epithelial progenitor/stem cells are a small subpopulation of oligopotent cells that are primarily located in the basal epithelial layer of the limbus. They produce undifferentiated progeny with limited proliferative potential that centripetally migrate from the periphery of the cornea to replace cells that desquamate during normal life [1–7]. Corneolimbal stem cells primarily reside in the palisades of Vogt in a niche that maintains their stemness by producing a unique anatomical and functional milieu [8, 9]. Although in humans the exact anatomical location of the niche is considered to be in the limbus, it has recently been proposed that epithelial progenitor/stem cells of equal potency are distributed throughout the entire ocular surface in other mammals [10]. Detection of corneal epithelial stem cells is the object of controversy among several groups because corneal progenitor/stem cell markers remain undetermined. Hes1 is known to be important for maintaining the self-renewal ability of progenitors and repressing the commitment of multipotent progenitor cells to a neuronal fate. In addition, Nakamura et al. reported that Hes1 regulates the corneal development and homeostatic function of corneal stem/progenitor cells [11]. p75NTR is a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, originally identified as a receptor for neurotrophins, and is expressed in the nervous system. p75 is also selectively expressed by basal epithelial cells in the corneal limbus; however, it is absent in the central cornea. ATP-binding cassette subfamily G member 2 (ABCG2) and keratin 19 and 15 as putative corneal epithelial stem/progenitor cell-associated molecules are also expressed in the corneal limbal basal cells.

Diabetes mellitus is a systemic disease that is characterized by chronic hyperglycemia [12, 13]. Ocular complications, such as retinopathy, cataract, and glaucoma, are well known. In particular, patients with diabetic keratopathy (DK) show various symptoms such as persistent corneal epithelial defects [14–17]. Alterations in the epithelial basement membrane, insufficient tear secretion, and neuropathy-associated denervation have been linked to abnormalities of the ocular surface.

Diabetes/diabetes (db/db) mice are generally used to study the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes. These mice have mutations in the genes that code for the leptin receptor, which is primarily localized in the hypothalamic region where it regulates the body weight and energy balance [18]. Db/db mice are hyperglycemic, hyperinsulinemic, and insulin resistant, and they demonstrate impaired tissue inflammatory responses in the cornea [19]. These mice have sensory nerve conduction deficits, small sensory nerve fiber neuropathy, and intraepidermal sensory nerve fiber loss [20]. Several studies have shown that skin wound healing is impaired in db/db mice, which is associated with a dysregulated inflammatory response [21]. To the best of our knowledge, there have been only a few reports that have focused on the influence of corneal progenitor/stem cells in neurodegenerative disorder such as type 2 diabetes. We have previously reported that corneolimbal stem cells significantly reduce after depletion of sensory nerves by electrocoagulation of the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve [22, 23]. Our data suggested a critical role of innervation in maintaining stem cells and/or the stem cell niche. The purpose of this study was to elucidate whether putative corneal stem/progenitor cells are altered in type 2 diabetic corneas and understand the pathogenesis of DK.

The prevention and amelioration of various complications caused by type 2 diabetes have been investigated. The insulin-like growth factor (IGF) system has been shown to play a role in diabetic retinopathy [24]. In previous studies, recombinant human insulin-like growth factor-I (rhIGF-I) has been shown to enhance the proliferation of several cell lines and protect cells from apoptosis induced by various factors [24–30]. We further aimed to assess and clarify whether IGF-I treatment is capable of protecting against corneal nerve damage and corneal stem/progenitor cells in diabetes. Our data demonstrate that sensory nerve degeneration of cornea affects stem cell homeostasis and leads to a significant increase in the number of corneolimbal stem/progenitor cells and corneal nerve in the rhIGF-1-treated diabetes. Herein, we hypothesized that there is a therapeutic potential of IGF-1 administration in neurodegenerative diseases such as type 2 diabetes.

2. Methods

2.1. Animals

Twelve-week-old male leptin receptor mutant (db/db) mice on a C57Bl/6 background and 12-week-old male C57BL/6 mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Db/db mice are widely used as models of type 2 diabetes. The research protocol conformed to the standards of the Association for Research in Vision and the Ophthalmology Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and was approved by the Animal Care Facility of St. Marianna University School of Medicine.

2.2. Retrobulbar Administration of rhIGF-I

rhIGF-I was purchased from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ, USA). rhIGF-I was reconstituted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and stored at −80°C until use according to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, the mice were anesthetized and placed in a stereotaxic frame (Narishige Scientific Instrument Lab, Tokyo, Japan). For rhIGF-1 treatment of the diabetic group, 11-week-old ob/ob mice were administered a retrobulbar injection of 100 μg/kg rhIGF-I twice daily for 7 days. On day 7 of the postexperimental procedure, the corneas from diabetic animals (n = 8) were enucleated.

2.3. Immunohistochemistry

Cryostat sections of 5 μm thickness were prepared from tissue that was embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT compound (Sakura Finetek USA, Inc., Torrance, CA, USA). After fixation with cold acetone for 10 min, the tissues were incubated with 10% goat serum containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and 1% BSA (room temperature (RT); 1 h) for Cytokeratin 19 (CK19) and with 1% BSA and goat serum (RT; 30 min) for hairy enhancer of split 1 (Hes1) [11]. For the CK19 staining, overnight incubation with a mouse monoclonal antibody against CK19 (1 : 200) (Abcam plc, Cambridge, MA, USA) was performed. For Hes1 staining, a rabbit anti-Hes1 polyclonal antibody (1 : 1,000) was used (from Dr. T. Sudo, Toray Industries, Inc., Tokyo, Japan). These sections were subsequently incubated (RT, 1 h) with the appropriate primary antibody and washed 3 times in PBS containing 0.15% Triton X-100 for 15 min. Antibody binding was detected by Alexa 488 or Alexa 594 conjugated secondary antibodies (Life Technologies GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany). The slides were washed 3 times in PBS containing 0.15% Triton X-100 for 15 min, coverslipped with antifading mounting medium containing 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Vectashield, Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA), and examined under a confocal microscope (LSM-510, Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Jena, Germany). For whole-mount immunofluorescence corneal staining, freshly excised corneas including the limbus were harvested and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, stained with anti-β tubulin-III antibody (1 : 200) (Rabbit anti-β tubulin-III polyclonal antibody, EMD Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA), and incubated with a secondary antibody that was conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (1 : 200) (Donkey anti-rabbit IgG, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Radial cuts were prepared in the cornea so that it could be flattened by a coverslip, and the cornea was mounted using the mounting medium (Vectashield, Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA). Images were taken at 400× magnification. Control incubations were performed with the appropriate normal mouse or rabbit IgGs at the same concentration as the primary antibody.

2.4. Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

RNA was isolated (RNeasy Micro Kit; QIAGEN Inc., Valencia, CA, USA) and reverse-transcribed (Superscript III Kit; Life Technologies Corporation). Real-time PCR was performed with a PCR mix (TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix; Life Technologies Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) and preformulated primers for Abcg2 (assay ID Mm00496364_m1), Hes1 (assay ID Mm00468601_m1), Keratin15 (assay ID Mm00492972_m1), p75 (assay ID Mm01309635_m1), and 18S ribosomal RNA (assay ID Mm03928990_g1) (all Applied Biosystems, Austin, TX, USA). The 18S ribosomal RNA was used as the endogenous reference for each reaction. The results were derived from the relative threshold cycle (Ct) by the deltadelta Ct method and normalized by 18S ribosomal RNA used as an internal control. The relative messenger RNA (mRNA) level in the normal corneas (normal group) was used as the normalized control for the groups with diabetes.

2.5. Quantitative Analysis

Image J 1.45 (provided program from National Institutes of Health) was used to create stacked images and calculate the corneal nerve density for the subbasal nerve branches of normal, diabetic, and rhIGF-1-treated mice. All subbasal nerve branches of the stacked corneal images were traced. Corneal nerve fiber density was subsequently determined with the length of the nerve fibers in each 1 mm2 area. The differences in corneal nerve fiber density between the two consecutive groups of mice were compared by the analysis of variance using a statistical analysis software package (SSRI Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical evaluation of data was performed with the unpaired t-test and the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test for comparisons among groups. The data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean and the value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Alterations in Ocular Properties

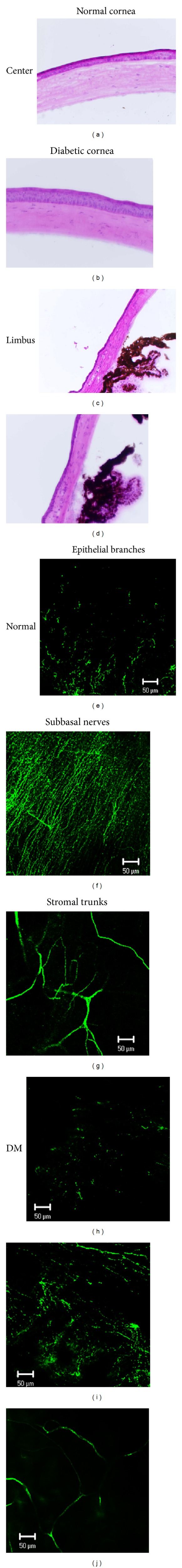

The morphology of the corneal epithelium and stroma was compared between a normal cornea (Figure 1(a): the center and Figure 1(c): the limbus) and the diabetic cornea of 12-week-old db/db mice (Figure 1(b): the center and Figure 1(d): the limbus) with hematoxylin and eosin staining, and the swelling and stratification of the diabetic corneal epithelium, both in the center (Figure 1(b)) and limbus (Figure 1(d)), were noted compared with that of the normal corneas (Figures 1(a) and 1(c)). In the diabetic group, the subbasal nerve plexus did not exhibit its characteristic branching pattern. The corneal subbasal nerve branches in the diabetic group (Figure 1(i)) appeared faint and disrupted. Moreover, no clear nerve structure of the epithelial branches could be significantly detected in the diabetic group (Figure 1(h)) compared with that in the normal group (Figure 1(e)).

Figure 1.

Ocular properties in ob/ob mice. Representative histological photomicrographs of hematoxylin and eosin-stained globe sections that were obtained from normal and 12-week-old diabetic mice. Swelling and stratification of the diabetic corneal epithelium are noted in comparison with the normal cornea. Magnification: 200x. Representative biomicroscopy of a normal cornea ((a) and (c)) and of a diabetic mouse cornea after 12 weeks ((b) and (d)). Representative histological photomicrographs of corneal nerves that were immunostained with an anti-β-III-tubulin fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated antibody showing the epithelial nerve (left column), subbasal nerve plexus (middle column), and stromal nerves (right column) in the normal eye ((e), (f), and (g)) and in a 12-week-old diabetic mouse eye ((h), (i), and (j)). Note the development of marked nerve degeneration after 12 weeks when the nerves appear faint and interrupted. Magnification: 200x.

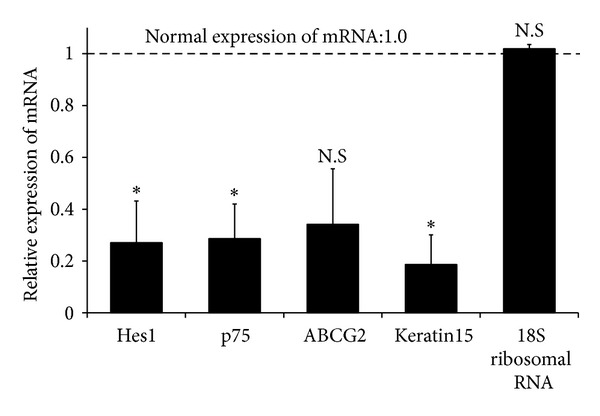

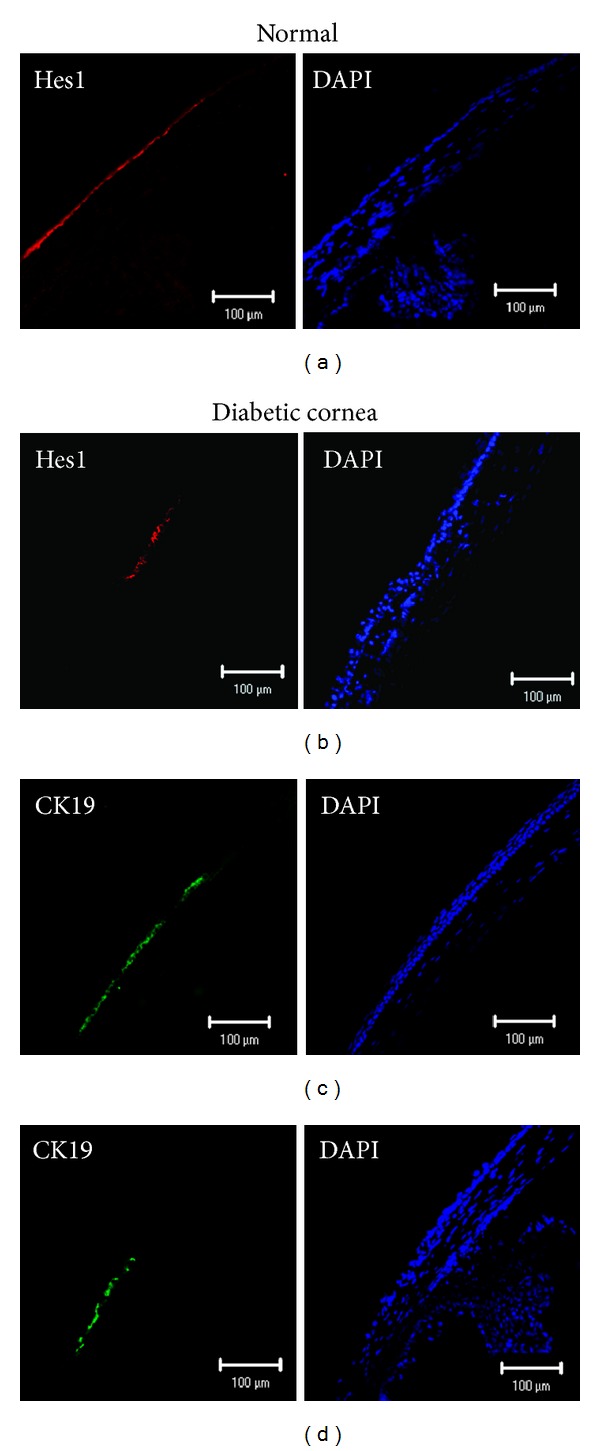

3.2. mRNA Expression and Immunostaining of Stem Cell Markers

We analyzed the expression levels of Abcg2, Hes1, p75, and Keratin15 in normal and diabetic corneas using real-time PCR (Figure 2). Decreased mRNA expression levels of p75 (3-fold; P = 0.019), Hes1 (3-fold: P = 0.035), and Keratin15 (5-fold; P = 0.043) were observed in diabetic corneas compared with normal corneas. An approximately 1.5-fold reduction in Abcg2 was also observed, although this was not statistically significant. 18S ribosomal RNA expression showed no significant difference between the normal group and group with diabetes (P = 0.254). To further compare protein expression of corneal stem/progenitor markers, we performed immunofluorescence microscopic studies in normal and diabetic corneas. The expression levels of Hes1 and Keratin19 was examined in normal corneal limbal cells (Figures 3(a) and 3(c)). The expression levels of both these stem cell markers decreased in the diabetic corneas (Figures 3(b) and 3(d)).

Figure 2.

Diminished mRNA expression levels of stem cell markers in diabetic cornea. The transcript levels of p75, hairy enhancer of split 1 (Hes1), Abcg2, and Keratin15 in the cornea are shown. The mRNA expression levels of p75, Hes1, and Keratin15 significantly decreased in diabetic corneas. A reduction of Abcg2 was also observed, although this was not statistically significant. 18S ribosomal RNA expression showed no significant difference between diabetic corneas and normal corneas. Statistical significance for mRNA levels is calculated on fold-change values over those of diabetic corneas. The dotted line represents the mRNA expression levels in normal corneas (normal expression of mRNA: 1.0). Statistical evaluation of data was performed with the unpaired t-test. The bars represent the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) (*P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Decreased expression levels of corneal progenitor/stem cell markers in diabetes. Representative immunostained micrographs of the cross-sections of the normal ((a) and (c)) and diabetic ((b) and (d)) corneas showing the expression of stem cell markers. Expression levels of Hes1 (b) and Keratin19 (d) decreased in diabetic eyes after 12 weeks compared with those in the normal eyes ((a) and (c)).

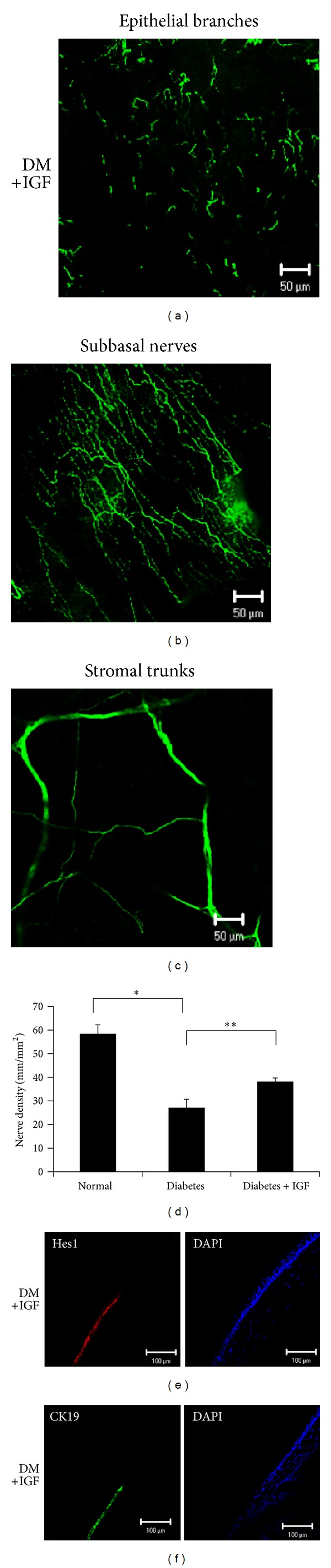

3.3. Effects of rhIGF-1 Administration on Corneal Innervation and Corneal Progenitor/Stem Cells

Figure 4 provides representative illustrations of the nerve fibers innervating the corneal epithelium (a) and the subbasal layer (b) in rhIGF-1-treated diabetic mice. In rhIGF-1-treated diabetic mice, corneal innervations significantly increased. We compared the corneal subbasal nerve density between the normal and diabetic corneas (Figure 4(d)). The corneal subbasal nerve plexus density of normal corneas was 58.29 ± 3.94 mm/mm2, whereas that of diabetic corneas was 27.01 ± 3.70 mm/mm2 (P < 0.00001). The subbasal nerve density in rhIGF-1-treated diabetic mice significantly increased (38.06 ± 1.67 mm/mm2) compared with that in the diabetic mice (P < 0.01). There was no significant difference in the corneal stromal nerve trunk densities among the normal, diabetic mice, and rhIGF-1-treated diabetic mice (data not shown). Moreover, the decrease in Hes1 and Keratin19 staining was suppressed in the rhIGF-treated diabetic cornea (Figures 4(e) and 4(f)) compared with that in diabetic corneas (Figures 3(b) and 3(d)).

Figure 4.

Effect of diabetes and treatment with recombinant human insulin-like growth factor-I (rhIGF-1) on corneal innervation and corneal progenitor/stem cells. Representative histological photomicrographs of corneal nerves that were immunostained with β-III-tubulin showing epithelial nerve (a), the subbasal nerve plexus (b), and stromal nerve trunks. (c) The rhIGF-I administration significantly accelerated recovery of the corneal subbasal nerve and epithelial branches. (d) Histogram of the quantification of the corneal subbasal nerve density. The subbasal nerve plexuses of the diabetic eyes completely diminished compared with that in the normal eyes, whereas those of rhIGF-1-treated diabetic corneas recovered. Statistical comparison of data between groups was performed using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test. The bars represent the mean ± SEM (*P < 0.00001, **P < 0.01). Representative immunostained micrographs of cross-sections of diabetic and rhIGF-1-treated corneas showing the expression of progenitor/stem cell markers. The decrease in Hes1 (e) and Keratin19 (f) staining was prevented in rhIGF-1-treated diabetic mice compared with diabetic mice (Figures 3(b) and 3(d)).

4. Discussion

In this study, we used db/db model mice and observed that the impaired corneal stem/progenitor cells that were observed in the type 2 diabetes models could have involved a loss of corneal nerves. Corneal nerves, in addition to their well-known sensory functions, help maintain the integrity of the ocular surface by releasing epitheliotrophic substances that promote corneal surface health [31]. In particular, the subbasal corneal nerve plexus contains the highest number of nerve branches in the cornea, and these branches directly extend into the corneal epithelium [32–34]. Prior studies have shown a reduction of the subbasal plexus in subjects with diabetes compared with normal subjects [35]. We also observed a decreased density of the corneal subbasal nerve plexus and corneal epithelial branches in leptin receptor mutant mice, which are an accepted animal model of type 2 diabetes. In this model, higher tortuosity was observed in the corneal subbasal nerve than in the normal nerve.

Diabetic corneal ulcerations remain an unresolved clinical condition. Diabetic patients suffer severe peripheral neuropathy, which is associated with the development of persistent corneal epithelial defects [36–38]. Although various nerve-secreted factors and peptides, such as NGF, substance P, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor, are important for epithelial regeneration and wound healing [39–44], corneal stem/progenitor cells are also closely related to corneal wound healing. However, Seitz et al. have shown that the underlying leptin deficiency in db/dbmice further amplifies these impairments in skin repair [45]. To characterize this, we studied the expression of putative corneal progenitor/stem cell markers and found a 60% reduction in p75, Keratin15, and Hes1 expression in diabetic corneas. In our study, not only were epithelial abnormalities and decreased innervation present in diabetic corneas but also the corneal epithelial progenitor/stem cells were altered and/or impaired. The high tear glucose concentration and various complications of diabetes make it difficult to fully dissociate the contribution of nerve depletion versus other pathological aspects of the disease with the stem cell reduction. However, given that the corneal limbus, where the corneal progenitor/stem cells reside, is densely innervated, delayed corneal epithelial wound healing may result, at least in part, due to impaired corneal progenitor/stem cells in diabetic corneas. Furthermore, these results supported those of our previous studies that the number of corneal stem/progenitor cells significantly decrease after deprivation of the sensory nerves [21].

With regard to physiological effects of diabetes, there are several studies that indicate a potential role for IGF, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), and dipeptidyl peptidase inhibitors in neuroprotection. Our results demonstrated that the rhIGF-I-treated diabetes group exhibited a significantly accelerated recovery of the corneal subbasal nerve and epithelial branches. The corneal subbasal nerve tortuosity remained in the rhIGF-1-treated diabetic mice, although we observed an increase in the density of the subbasal nerves. With topical administration of rhIGF-1 in diabetic corneas, alterations in the expression patterns of the corneal stem/progenitor proteins became consistent with healing. The normal corneal epithelium is a stratified layer of cells connected by tight junctions that provide a barrier against compounds larger than 1 nm. The pharmacological action was considered to be poorly effective because the high molecular weight (e.g., rhIGF-1) made penetration of the corneal epithelium difficult. The ciliary nerves of the trigeminal nerve entering the sclera are anatomically located close to the optic nerve at the posterior globe. In previous reports, the sclera permeability was significantly higher than the respective permeability across the cornea and conjunctiva for macromolecular substances [46]. It was difficult to inject the precise volume and maintain the drug so that the mouse cornea could exhibit minimum thickness at the limbus. Furthermore, we aimed to inhibit the fluctuating or low concentration of the drug by tear fluid. Although there are no studies on the effectiveness of retrobulbar IGF-1 injections, we used a periocular approach for retrobulbar injection in order to avoid any delivery loss of the medicine because of frequent blink and to achieve high infiltration and drug retention in the periocular tissue.

Recently, Chen reported that treatment with rhIGF-I can promote hematopoietic stem cell/progenitor survival, as shown by the increased frequency of Sca-1+ cells in bone marrow harvested after subcutaneous injection with rhIGF-I following total body irradiation [47]. The direct neuronal (intrathecal) delivery of IGF-I improved and reversed the slowing of motor and sensory conduction velocity in rats with diabetes. In addition, insulin and IGF-I prevented atrophy in myelinated sensory axons in the sural nerve [48]. As they also mentioned, it is thought that the direct delivery of IGF-I to neurons may correct diabetes-associated abnormalities by restoring suitable mitochondrial function. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that rhIGF-I decreases apoptosis and promotes cell survival in a PI3-kinase-dependent manner [49]. IGF-I activates the serine/threonine kinase Akt through PI3-kinase. This activation phosphorylates and inhibits caspase-3, resulting in decreased apoptosis. Therefore, rhIGF-1 treatment could protect corneal stem/progenitor cells from damage. Taken together, our data suggested that the preservation of corneal stem/progenitor cells could be a consequence of regenerative changes in the corneal nerves in type 2 diabetes. With regard to the healing of corneal nerve and stem/progenitor cells, the topical administration of IGF-1 may become applicable in severe situations caused by persistent corneal ulcers in patients with type 2 diabetes.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, our results suggest that the number of corneal progenitor/stem cells significantly reduce in an animal model of type 2 diabetes. We provided novel evidence for the critical role of innervation in maintaining corneal epithelial cells and/or the stem cell niche in diabetes. Furthermore, our studies showed that rhIGF-1 prevented and/or decreased changes in the corneal progenitor cells and nerves that were associated with type 2 diabetes. These findings were also innovative results, wherein alterations in the corneal nerve and stem/progenitor cells were consistent with healing in IGF-1-treated diabetes. It is provocative to guess that the functional relationship between the nerve and stem cells that was described in this paper could apply to other epithelial/nonepithelial stem cells in the body. Thus, these findings contributed to our understanding of the factors that are relevant to maintaining the progenitor/stem cell niche in diabetes.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by a Grant (no. 25861657) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (KAKENHI).

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Schermer A, Galvin S, Sun T-T. Differentiation-related expression of a major 64K corneal keratin in vivo and in culture suggests limbal location of corneal epithelial stem cells. The Journal of Cell Biology. 1986;103(1):49–62. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cotsarelis G, Cheng S-Z, Dong G, Sun T-T, Lavker RM. Existence of slow-cycling limbal epithelial basal cells that can be preferentially stimulated to proliferate: implications on epithelial stem cells. Cell. 1989;57(2):201–209. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90958-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kinoshita S, Friend J, Thoft RA. Sex chromatin of donor corneal epithelium in rabbits. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 1981;21(3):434–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buck RC. Measurement of centripetal migration of normal corneal epithelial cells in the mouse. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 1985;26(9):1296–1299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kruse FE. Stem cells and corneal epithelial regeneration. Eye. 1994;8(2):170–183. doi: 10.1038/eye.1994.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beebe DC, Masters BR. Cell lineage and the differentiation of corneal epithelial cells. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 1996;37(9):1815–1825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagasaki T, Zha J. Centripetal movement of corneal epithelial cells in the normal adult mouse. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2003;44(2):558–566. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stepp MA, Zieske JD. The corneal epithelial stem cell niche. The Ocular Surface. 2005;3(1):15–26. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70119-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies SB, Chui J, Madigan MC, Provis JM, Wakefield D, Di Girolamo N. Stem cell activity in the developing human cornea. Stem Cells. 2009;27(11):2781–2792. doi: 10.1002/stem.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Majo F, Rochat A, Nicolas M, Jaoudé GA, Barrandon Y. Oligopotent stem cells are distributed throughout the mammalian ocular surface. Nature. 2008;456(7219):250–254. doi: 10.1038/nature07406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakamura T, Ohtsuka T, Sekiyama E, et al. Hes1 regulates corneal development and the function of corneal epithelial stem/progenitor cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26(5):1265–1274. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feman SS. Diabetes and the eye. In: Tasman W, editor. Duane’s Clinical Ophthalmology. Vol. 5. Philadelphia, Pa, USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000. pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herse PR. A review of manifestations of diabetes mellitus in the anterior eye and cornea. American Journal of Optometry and Physiological Optics. 1988;65(3):224–230. doi: 10.1097/00006324-198803000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaji Y. Prevention of diabetic keratopathy. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2005;89(3):254–255. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.055541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schultz RO, Van Horn DL, Peters MA, Klewin KM, Schutten WH. Diabetic keratopathy. Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society. 1981;79:180–199. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sánchez-Thorin JC. The cornea in diabetes mellitus. International Ophthalmology Clinics. 1998;38(2):19–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cisarik-Fredenburg P. Discoveries in research on diabetic keratopathy. Optometry. 2001;72(11):691–704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elmquist JK, Maratos-Flier E, Saper CB, Flier JS. Unraveling the central nervous system pathways underlying responses to leptin. Nature neuroscience. 1998;1(6):445–450. doi: 10.1038/2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maruyama K, Asai J, Ii M, Thorne T, Losordo DW, D’Amore PA. Decreased macrophage number and activation lead to reduced lymphatic vessel formation and contribute to impaired diabetic wound healing. The American Journal of Pathology. 2007;170(4):1178–1191. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi TJ, Zhang MD, Zeberg H, et al. Coenzyme Q10 prevents peripheral neuropathy and attenuates neuron loss in the db-/db- mouse, a type 2 diabetes model. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110(2):690–695. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220794110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kämpfer H, Schmidt R, Geisslinger G, Pfeilschifter J, Frank S. Wound inflammation in diabetic ob/ob mice: functional coupling of prostaglandin biosynthesis to cyclooxygenase-1 activity in diabetes-impaired wound healing. Diabetes. 2005;54(5):1543–1551. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.5.1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferrari G, Chauhan SK, Ueno H, et al. A novel mouse model for neurotrophic keratopathy: trigeminal nerve stereotactic electrolysis through the brain. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2011;52(5):2532–2539. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ueno H, Ferrari G, Hattori T, et al. Dependence of corneal stem/progenitor cells on ocular surface innervation. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2012;53(2):867–872. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burgos R, Mateo C, Cantón A, Hernández C, Mesa J, Simó R. Vitreous levels of IGF-I, IGF binding protein 1, and IGF binding protein 3 in proliferative diabetic retinopathy: a case-control study. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(1):80–83. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma J, Sawai H, Matsuo Y, et al. IGF-1 mediates PTEN suppression and enhances cell invasion and proliferation via activation of the IGF-1/PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in pancreatic cancer cells. Journal of Surgical Research. 2010;160(1):90–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Özdinler PH, Macklis JD. IGF-I specifically enhances axon outgrowth of corticospinal motor neurons. Nature Neuroscience. 2006;9(11):1371–1381. doi: 10.1038/nn1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bian D, Li Z, Ma H, et al. Effects of diosgenin on cell proliferation induced by IGF-1 in primary human thyrocytes. Archives of Pharmacal Research. 2011;34(6):997–1005. doi: 10.1007/s12272-011-0617-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoon MJ, Roser JF. Insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) protects cultured equine Leydig cells from undergoing apoptosis. Animal Reproduction Science. 2010;122(3-4):353–358. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qiu W, Leibowitz B, Zhang L, Yu J. Growth factors protect intestinal stem cells from radiation-induced apoptosis by suppressing PUMA through the PI3K/AKT/p53 axis. Oncogene. 2010;29(11):1622–1632. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown-Borg HM, Rakoczy SG, Romanick MA, Kennedy MA. Effects of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-1 on hepatocyte antioxidative enzymes. Experimental Biology and Medicine. 2002;227(2):94–104. doi: 10.1177/153537020222700203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mylonas PG, Matsouka PT, Papandoniou EV, Vagianos C, Kalfarentzos F, Alexandrides TK. Growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor I protect intestinal cells from radiation induced apoptosis. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2000;160(1-2):115–122. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(99)00215-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goins KM. New insights into the diagnosis and treatment of neurotrophic keratopathy. The Ocular Surface. 2005;3(2):96–110. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70158-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Müller LJ, Vrensen GFJM, Pels L, Cardozo BN, Willekens B. Architecture of human corneal nerves. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 1997;38(5):985–994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tavakoli M, Petropoulos IN, Malik RA. Assessing corneal nerve structure and function in diabetic neuropathy. Clinical and Experimental Optometry. 2012;95(3):338–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1444-0938.2012.00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang C, Fu T, Xia C, et al. Changes in mouse corneal epithelial innervation with age. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2012;53(8):5077–5084. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-9704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yin J, Huang J, Chen C, Gao N, Wang F, Yu F-SX. Corneal complications in streptozocin-induced type I diabetic rats. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2011;52(9):6589–6596. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-7709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Cillà S, Ranno S, Carini E, et al. Corneal subbasal nerves changes in patients with diabetic retinopathy: an in vivo confocal study. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2009;50(11):5155–5158. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosenberg ME, Tervo TMT, Immonen IJ, Muller LJ, Gronhagen-Riska C, Vesaluoma MH. Corneal structure and sensitivity in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2000;41(10):2915–2921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hyndiuk RA, Kazarian EL, Schultz RO, Seideman S. Neurotrophic corneal ulcers in diabetes mellitus. Archives of Ophthalmology. 1977;95(12):2193–2196. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1977.04450120099012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishida T, Chikama T-I, Morishige N, Yanai R, Yamada N, Saito J. Persistent epithelial defects due to neurotrophic keratopathy treated with a substance P-derived peptide and insulin-like growth factor 1. Japanese Journal of Ophthalmology. 2007;51(6):442–447. doi: 10.1007/s10384-007-0480-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Araki-Sasaki K, Aizawa S, Hiramoto M M, et al. Substance P-induced cadherin expression and its signal transduction in a cloned human corneal epithelial cell line. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2000;182(2):189–195. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200002)182:2<189::AID-JCP7>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Solomon A, Meller D, Prabhasawat P, et al. Amniotic membrane grafts for nontraumatic corneal perforations, descemetoceles, and deep ulcers. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(4):694–703. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(01)01032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen H-J, Pires RTF, Tseng SCG. Amniotic membrane transplantation for severe neurotrophic corneal ulcers. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2000;84(8):826–833. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.8.826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lockwood A, Hope-Ross M, Chell P. Neurotrophic keratopathy and diabetes mellitus. Eye. 2006;20(7):837–839. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seitz O, Schürmann C, Hermes N, et al. Wound healing in mice with high-fat diet- or ob gene-induced diabetes-obesity syndromes: a comparative study. Experimental Diabetes Research. 2010;2010:15 pages. doi: 10.1155/2010/476969.476969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahmed I, Gokhale RD, Shah MV, Patton F. Physicochemical determinants of drug diffusion across the conjunctiva, sclera, and cornea. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 1987;76(8):583–586. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600760802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen S, Xu Y, Wang S, et al. Subcutaneous administration of rhIGF-I post irradiation exposure enhances hematopoietic recovery and survival in BALB/c mice. Journal of Radiation Research. 2012;53(4):581–587. doi: 10.1093/jrr/rrs029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brussee V, Cunningham FA, Zochodne DW. Direct insulin signalling of neurons reverses diabetic neuropathy. Diabetes. 2004;53(7):1824–1830. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.7.1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li Y, Wu H, Khardori R, Song Y-H, Lu YW, Geng Y-J. Insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor activation prevents high glucose-induced mitochondrial dysfunction, cytochrome-c release and apoptosis. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2009;384(2):259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.04.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]