Abstract

This 10-year study (N=177) examines how people with HIV use spirituality to cope with life's trauma on top of HIV-related stress (e.g., facing death, stigma, poverty, limited healthcare) usual events. Spirituality, defined as a connection to a higher presence, is independent from religion (institutionalized spirituality). As a dynamic adaptive process, coping requires longitudinal studying. Qualitative content-analysis of interviews/essays yielded a coding of specific aspects and a longitudinal rating of overall spiritual coping. Most participants were rated as spiritual, using spiritual practices, about half experienced comfort, empowerment, growth/transformation, gratitude, less than one-third meaning, community, and positive reframing. Up to one-fifth perceived spiritual conflict, struggle, or anger, triggering post-traumatic stress, which sometimes converted into positive growth/transformation later. Over time, 65% used spiritual coping positively, 7% negatively, and 28% had no significant use. Spirituality was mainly beneficial for women, heterosexuals, and African Americans (p<0.05). Results suggest that spirituality is a major source of positive and occasionally negative coping (e.g., viewing HIV as sin). We discuss how clinicians can recognize and prevent when spirituality is creating distress and barriers to HIV treatment, adding a literature review on ways of effective spiritual assessment. Spirituality may be a beneficial component of coping with trauma, considering socio-cultural contexts.

Introduction

People living with HIV (PLWH) are confronted with multiple traumas. Besides the stigma and suffering of being confronted with the disease, they are also often deprived of basic necessities, such as access to health care, support from their families or community, ultimately living in isolation with a very low disability income. Other common traumas include death of a loved one, sexual abuse, and divorce. In such extreme situations, people often utilize spirituality to cope.1 The purpose of this study is to examine spiritual coping strategies and their longitudinal effect that will hopefully help guide clinicians in the trauma-treatment of PLWH.

Pargament2 has developed a transactional model of spiritual coping, defining spirituality as the search for the sacred, and religiousness as the search for the sacred within a religious denomination.3 However, due to the moral stigma associated with HIV within many religious institutions, PLWH often consider themselves rather more spiritual than religious.3–5

Our own findings in PLWH4 dovetail Pargament's research,3 but emphasize the connection aspect of spirituality rather than the sacred component. In line with others,6–10 we define spirituality as the connection to a higher presence (e.g., within oneself, others, nature, or the transcendent), and religion as an organized, institutionalized spirituality. Thus, spirituality is a broader individualistic concept that includes people who reject organized religion.6,8,9

The transactional model of stress and coping of Folkman and Lazarus11 defines coping as a reduction of the discrepancy between the primary appraisal of the stressor and the secondary appraisal of one's ability to cope. The theoretical framework of the present study is based on our functional components model of coping,12 which is similar to the transactional model but with an important added component. In addition to appraisals of the stressor and the self, a third appraisal involves the reaction to the stressor. Coping involves continuous formative evaluation of the three functional components, the stressor, the self, and the reaction. In other words, people react to stressful situations by adjusting their coping strategies, sometimes multiple times, until finding a strategy that works. For example, a gay man who prayed to God “to make him straight” finally became angry that his prayer remained unfulfilled. After developing his individual spiritual path, he came to terms with being gay.4 This example illustrates that the dynamics of the three functional components of coping need to be viewed in a longitudinal context.

The main shortcoming of prior research was that most of the studies on spiritual coping were cross-sectional or of short duration.12,13 For example, in people using spirituality to cope with trauma, a cross-sectional analysis may show a potentially spurious link between spiritual coping and depression.14 Another common pitfall of cross-sectional research on coping is the stratification of aspects of coping strategies into adaptive and maladaptive. A cross-sectional snapshot does not provide us with information about the long-term consequences. As our prior research showed, spiritual struggle at the time of trauma was often a trigger of post-traumatic growth and positive spiritual transformation.4,15–18 Our longitudinal study has shown that a positive view of God19 and an increase in spirituality after diagnosis20 predicted significantly slower disease-progression (better preservation of CD4-cells and viral load decrease),21 whereas a negative view of God predicted significantly faster disease progression over 4 years.

Traditionally, spiritual and cognitive coping have been subcategorized under emotion-focused coping.12 Therefore, measurements of coping do not differentiate whether positive-reframing or meaning-making are based on spirituality or cognitions.22–24 However, we view spiritual coping, cognitive coping, and emotion focused coping as three distinct entities.12 Spirituality is a broad construct, which may include cognitive, emotional, and behavioral aspects, and this spiritual coping may also involve concrete spiritual activities that are either cognitive or emotionally driven.

In line with others,6–10 we conceptualize spiritual coping as a focus on the connection to a higher presence that aids in meaning-making, positive reframing, self-empowerment, and growth/transformation on a personal and/or spiritual level. Ultimately, the use of spiritual coping can lead to spiritual transformation—a long-lasting profound change of one's behaviors, attitudes, beliefs (including spiritual beliefs), and self-views.4,15–18 Notably, spiritual coping can also be the “fork in the road” that turns life towards a negative path.17

Consistent with Lazarus and Folkman,11 our functional components model12 emphasizes the importance of adapting one's coping style to the stressor—using problem-focused coping for changeable situations, and spiritual, cognitive, and emotion focused coping for unchangeable situations. For example, a woman survived before effective treatment became available because she firmly believed that God would heal her from HIV. However, her spiritual control belief became detrimental when she refused available effective treatment. Thus, the same coping strategy can have either positive or negative effects depending on the context.

The present study was informed by our literature review on spirituality and coping with HIV.12,13 In a meta-analysis on effective ways of coping, Moskowitz25 pointed out the need for qualitative research to focus on aspects that may not be covered in quantitative research.

This is the first study based on the functional components model of coping that examines spiritual coping longitudinally in a large sample with qualitative and quantitative methods. The primary aims of this study are to identify and quantify which specific aspects of spirituality are relevant for coping with trauma in PLWH and to develop a longitudinal measurement of the effect, use, and dynamics of spiritual coping. A secondary aim is to identify socio-demographic factors predisposing one to use spiritual coping with a positive effect. The overall goal is to discuss the implications for PLWH, as well as healthcare workers, so they may help guide PLWH to find their best possible path to cope with trauma.

Methods

In our longitudinal study, we have followed 177 people with HIV for up to 10 years to examine psychosocial and spiritual factors related to health.19–21 In this secondary data analysis, we use a mixed method approach, applying qualitative techniques to examine aspects of spiritual coping and to develop an overall rating of spiritual coping. Quantitative variables were then derived from frequencies of these codes and ratings.

Study population and sampling

At entry, between 1997–2000, the study selected people in the mid-range of HIV disease (150–500 CD4-cells/mm3, CD4-nadir >75 cells/mm, no prior AIDS-defining symptoms). People with dementia, active substance use disorder, and/or psychosis (based on the SCID, DSM-III-R) were excluded. Participants were recruited via flyers (distributed through doctors' offices, community events, support groups, HIV organizations), newspaper ads, and word of mouth.

Procedures

The study was IRB approved; all participants gave informed consent and received $50 compensation. Our interviewers contacted the participants every 3 months by phone and scheduled them every 6 months for office visits. Either Dr. Ironson (P.I.) or a master-level mental health staff conducted the interview. We made efforts to maintain continuity of the interviewer, three of them employed between 9–14 years.

We collected in-depth interviews and essays in 6-month intervals, asking participants how they cope with HIV and traumatic events as they occur. At the initial and every follow-up interview, we explored HIV disclosure (and sexual orientation) and how the reaction to the disclosure was. We further asked how their life changed since the diagnosis; how they spent their daily life; which activities they looked forward to; if they had a partner, and if they were sexually active and practiced safer sex; if and how their partners were helpful to them, if they had someone to take care of them if needed and to share their deepest feelings with; and if they had partners or friends who died from AIDS and how they coped.

Other questions tapped into their spiritual and afterlife beliefs, estimated life expectancy, and healthcare information—we asked how they found their physician and if they were satisfied with their medical care; what they were doing to keep themselves healthy; what percentage of their well-being was due to their own attitudes and behaviors vs. medical care; if they were getting complementary or alternative treatment; and if they were taking prescribed medication and the reason behind it.

Finally, we asked about what enabled them to keep going in the face of HIV and if anything positive had resulted from being HIV-positive or anything else was relevant to maintaining their health in the face of HIV. In addition, interviews and essays captured how they coped with the most difficult life event over the past 6 months.

On the life-event scale (from −3 to +3),27,28 participants rated the stress of events that had happened to them in the past 6 months. They also wrote a “trauma” essay, which asked participants to describe the most stressful event that had happened to them in the past 6 months, including their deepest thoughts and feelings. To transcribe the most relevant interview/essay, we chose a time-point with the highest distress rating (closest to −3, very stressful) during the first 3-year period of the longitudinal study (1997 to 2000). Besides this interview/essay, a team of ten trained transcribers summarized the content of all other interviews and essays for up to 10 years.

All transcripts were quality controlled and entered in the qualitative software ATLAS.ti® and rated using directed qualitative content analysis,29–31 an empirical reliability controlled analysis of texts that allows both qualitative and quantitative operations. This method allowed us to develop a coding agenda for aspects of spiritual coping and to develop an overall rating of spiritual coping over time.

Qualitative content analysis

After completion of a transcript, the transcriber worked with the research team inductively line by line through the entire text to capture quotes and anchor examples for the coding of aspects and the overall rating of spiritual coping. At a point of saturation (after more than 70 interviews), we compiled tentative coding and rating definitions and anchor examples. Analyzing 20 interviews, ten raters established independent inter-rater reliability. For each Cronbach's alpha <0.80, definitions were revised. Next, chance-corrected inter-rater reliability of two raters was established for 20 further interviews. The definitions were fine-tuned until reliability of the coding was substantial (Cohen's Kappa above 0.60), and reliability of the overall spiritual coping rating was excellent (Kendall's tau B=0.81, p<0.001). Finally, two raters analyzed all 177 transcripts independently. Each rater provided quotes for each coded spiritual strategy and gave an overall rating of longitudinal spiritual coping. Any discrepancies on codings or ratings were either consensually agreed or discussed in the team.32 For the rating, any discrepancies >1 were quality controlled by another rater-couple, again coding independently and reviewing discrepancies consensually. In one case, there was not enough information to rate overall longitudinal spiritual coping reliably.

Statistical analysis

All qualitative data were aggregated and transferred into SPSS® version 19 for further statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics and group comparisons (ANOVA and Chi-square tests) were used to depict the frequencies and socio-demographic associations of spiritual coping.

Results

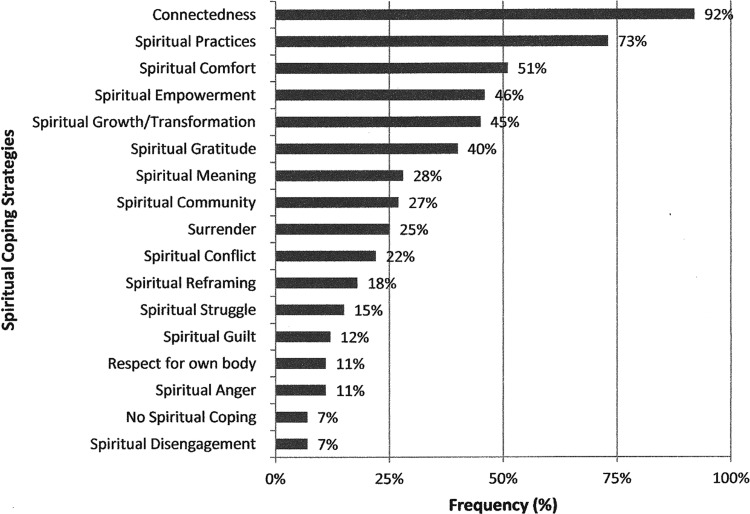

We summarized the codes, definitions, and examples of specific aspects of spiritual coping in Table 1, the longitudinal rating of spiritual coping in Table 2, and the respective frequencies in Figs. 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Specific Aspects of Spiritual Coping, Each with Definition and Example

| Coding | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Spiritual connectedness | to a higher presence. This may include the search for “the sacred”, which can also include aspects of life perceived as sacred by the individual. | “[HIV] brought me closer to God.” -“I believe in a higher power. But I don't go into church. You have to have church in your heart” -“I just became one with the mountain” described an atheist his mystical experience. - “My religion is based on mother nature and human beings; the nature of trees and water and ecology and circle of life.” |

| Spiritual practices | include any activity that one associates with cultivating spirituality. | Person attends church, meditates, prays, or does different body-mind practices such as yoga or relaxation techniques. Person attends specific “spiritual rituals” or reads spiritual books (e.g. the bible).- “Love is an integral part in practicing my beliefs.” |

| Spiritual empowerment | relates to the positive secondary appraisal of the ability of the self to cope with the stressor. The spiritual connection increases the self-efficacy to cope. This code only applies, if the sense of empowerment derives from spirituality. | “God gives me energy, […] knowledge, and wisdom, and strength to go on”; Spirituality helped to “discover myself” and “made me stronger.” |

| Spiritual growth/transformation | describes a marked, noticeable change in ways of spiritual coping that lead to long-lasting positive changes in attitudes, spiritual beliefs, behavior and/or self-views. Spiritual growth may correspond to a spiritual transformation in case changes occur in all of these four areas. | “That last drug I used was my transformation.” described a mother diagnosed with HIV during pregnancy, who was about to take her “last hit”. “God was paving the way for me, and he gave me the strength and the courage to keep walking.” Twelve years after her call on God for help, she defines herself as a responsible mother and grandmother. |

| Spiritual gratitude | can be expressed in thankfulness or appreciation and is a positive emotion or attitude in acknowledgment of a benefit that one has received or will receive. This gratitude is linked to a higher presence or spirituality. | “I thank God for being blessed in my own way”; - “I am grateful for everything around me. All the time, every day. I am grateful for the trees and nature, the flowers, the fruit, the food, the roof over my head, my work, the ability to be able to work, health, life.” |

| Spiritual meaning | is defined as finding a greater meaning and/or purpose in life via spirituality. According to this definition, the sense of meaning must have spiritual ties. | Person overcame substance use with the help of AA and is now finding meaning through helping other substance users. - “God wanted me to get HIV to teach others how to live with the disease” described an HIV counselor. - “[God] gave me kids to get me out the streets because I was still getting high.” |

| Spiritual community | provides social support. Experiencing a connectedness to a higher presence through membership in a spiritual community qualifies to receive this label. Being a member of a spiritual community alone, without a feeling of connectedness is not sufficient for this code. | Person is attending a church group, church choir, meditation classes, yoga classes or a support group. Being part of this community gives “strength”. - “When I started volunteering in the HIV arena that gave me a sense of spirituality. I was connecting. God was using me, I was being used to help people.” |

| Surrender/centrality | means that the person gives up his own will and subjects his thoughts, ideas, and deeds to the will and teachings of a higher power. Spirituality is a central driving force that influences most aspects of the person's life. Surrender can be negative if person is using it as an avoidance strategy. | “God brought me to the other side. He did what I could not do. We can't do nothing by ourselves” described a woman who feels that God “saved” her from death of substance use, being raped by a gang, and many other life threatening situations. – “I will live as long as God wants me to.” –“My faith in God is the force that keeps me going”. – Another woman avoids seeing a doctor and taking HIV medication because she feels that prayer is all she needs to stay healthy with HIV. |

| Spiritual conflict | refers to the idea that the person is definitely spiritually connected, but disagrees with, or breaks rules/doctrines dictated by spiritual belief systems. Spiritual conflict often involves religious beliefs. | “As a gay man, I still would go to Mass but I just cannot agree with their official position on homosexuality, gay adoption, condom use, and gay marriage. I have always felt that spirituality is important in my inner peace and control of HIV – but now I am at a crossroads.” |

| Spiritual positive reframing | is only coded if positive reframing occurs in a spiritual context. Positive reframing refers to a positive primary appraisal of the stressor that leads to viewing the stressor as less toxic to the self. Spiritual positive reframing enhances a transcendent perspective. | “God has chosen me [to have HIV] as part of a divine plan”; - “Now I feel I was blessed, when I thought I was cursed”. - A woman reframes sexual abuse, 3 teenage pregnancies, homelessness, prostitution, substance addiction, poverty, incarcerations etc. as “God put me through a lot of things to clean me up. God gave me a second chance to help others.” |

| Spiritual struggle | can be both constructive as well as destructive. Questioning the existence or benevolence of a higher presence. Critical thinking and challenging of spirituality/religiousness. Doubting the previous view of own spirituality. Feelings of disconnectedness. | “My faith in Catholic church has been shaken” described a person after the death of a loved one. First, this resulted in “losing faith in God” and later in “feeling a deeper connection to God”. - “Jesus got me there” blames someone with suicidal feelings out of spiritual guilt for infecting others through unprotected sex while stopping HIV medication. |

| Spiritual guilt | refers to a negative self-judgment. It can be expressed in feelings of wrong-doing or worries that a higher presence is displeased with one's behavior. Other forms refer to the feeling of not being engaged enough in spirituality. | “I wish I was more spiritual”; - “I haven't been going to church like I should”. - A gay Catholic believes “homosexuality is a sin” and prays to God to make him “straight”. - “I might go to hell for going with men” believes someone who has unprotected sex. |

| Spiritual anger | includes frustration or outrage at a higher presence or negative emotions towards spiritual communities or religious institutions. | Person is angry with God, because “this all-powerful and mighty God causes so much harm, pain and hurt”. - Another expresses feelings of hostility towards spiritual communities for “ostracizing someone for being gay” and towards institutionalized religion for its way of “handling the gay issue” or “the whole issue on condoms”: “I cussed out God. At that time I quit the Church. I told God, whenever I got to Heaven the first thing we were going to do was fight.” |

| Respect for own body | engenders in this case a greater respect for one's own body and a greater care-taking behavior that is linked to spirituality. | Someone beliefs that his body is “a gift from God” and “the temple of the soul.” This spiritual belief is the motivation to maintain a healthy lifestyle and to adhere to HIV treatment. |

| Spiritual disengage-ment | goes beyond disengaging in spiritual practices. It also involves no longer searching a connectedness to a higher presence. | “I grew up as a religious person. After I got diagnosed, I stopped believing. The longer this has happened, the more empty I have become, spiritually and religiously, dead.” |

Table 2.

Longitudinal Rating of Spiritual Coping

| Rating | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| −4 | Severe spiritual struggle, conflict, and anger. Inconsistency and confusion in spiritual beliefs. Strong spiritual “searching” but without finding a satisfactory spiritual “home.” | Participant feels “pissed of” by God causing “so much harm, pain, and hurt”, blames negativity in life on spiritual presence. Constant spiritual questioning but perceives spiritual search as negative and a “waste of time.” |

| −3 | Persistent spiritual struggle and conflict. Belief in spiritual punishment, but not questioning the existence of “higher presence”. | Participant believes that life is a “hell” in which “we pay for our sins” (i.e., own homosexuality). Engagement in spirituality to avoid punishment from “higher presence.” |

| −2 | Ambiguous spiritual coping with a negative dysbalance. Transient spiritual struggle/conflict, both negative and positive use of spiritual coping. Lack of spiritual consistency prevents effective spiritual coping. | Participant experiences spiritual struggles at times and is very engaged and positive in his/her use of spiritual coping at other times. Spiritual inconsistency is perceived as “negative experience.” |

| −1 | Some connection to a higher presence but feeling some spiritual guilt. Feeling the necessity to be more spiritually engaged but not taking any action. | Participant believes in God but “wishes” he/she could be more spiritual and “confident in God.” |

| 0 | No spiritual coping, no spiritual connection, no spiritual search | Participant believes that spirituality is “rubbish” and that life after death is “just a superstition.” Someone who states that he/she “never had any spiritual beliefs” nor questioning. |

| 1 | Some connection to a higher presence but no elaborate use of spiritual coping. Inconsistent spiritual practice. | Participant believes in God without questioning. Spirituality is not central in coping. |

| 2 | Clear connectedness to a higher presence, exhibits reasonable consistency with spiritual practices. Absence of spiritual growth, meaning or reframing. | Participant perceives benefit from spiritual practices and connectedness. |

| 3 | Presence of spiritual meaning or spiritual growth/transformation. Increasing spirituality in the face of adversity. No indication of positive spiritual surrender. | Participant exhibits an increase in spirituality since HIV diagnosis, “feeling blessed by God” for having HIV. |

| 4 | Spiritual growth/transformation or spirituality as a central component in the life. Presence of positive spiritual surrender. | Spiritual beliefs are the driving force in the participant's life. Participant believes that a higher presence has saved his/her life. |

FIG. 1.

Specific aspects of spiritual coping (% frequency).

Fig. 2.

Longitudinal rating of spiritual coping (frequencies in %). Spiritual coping is coded on a 9-point scale (see Table 2). The longitudinal use and effect of spiritual coping can be grouped into three categories: Use with negative effects (from −4 to −2), no significant use/effect (from −1 to +1), and use with positive effects (from +2 to +4).

Socio-demographics

The sample was diverse with respect to gender (30% female), ethnicity (36% African American, 31% White (non-Latino), 28% Latino), sexual orientation (45% heterosexual), and education (77% high-school or less, 19% college graduates). Most participants were relatively poor (modal annual income $10,000), which is consistent with high unemployment (15%) and disability (42%). About half (52%) did not attend religious services, 23% less than weekly, and 25% at least weekly.

Stressful life events

Within the first 3 years, 118 of 177 participants reported a very stressful event such as death of a loved one and/or divorce, or another comparably stressful life event.

Specific aspects of spiritual coping

According to our coding, most participants were spiritual (92%) and used spiritual practices (73%), whether the connection to a higher presence was found via “praying to God” or “feeling one with a mountain”. Spiritual comfort (51%), empowerment (46%), growth/transformation (45%), and gratitude (40%) were frequent positive aspects of spirituality. However, spirituality was less involved in the many ways of meaning-making (28%), positive reframing (18%), and community support (27%). Surrender (25%) was a double-edged sword, since the belief that “God is in control” could result in both overcoming substance use and not taking HIV medication.

The dynamics of spiritual coping were also illustrated by less common aspects, such as conflict (22%), struggle (15%), guilt (12%), anger (11%), and disengagement (7%). A critical confrontation with spirituality could catalyze both a spiral of negative effects and a positive transformation via an increase in spirituality.

Longitudinal rating of spiritual coping

The longitudinal rating of spiritual coping showed that each spiritual aspect can have both a positive and a negative effect on coping depending on the context. Spiritual practices do not always have positive effects as demonstrated in the introductory example of the gay man praying to God to make him straight and the woman not taking her medication because she felt her prayers had healed her from HIV. The rating of spiritual coping takes into account the overall longitudinal effect of all aspects of spiritual coping. Over time, spiritual coping is a dynamic multidimensional construct that reflects more than the sum of specific aspects and cannot be investigated by looking at one traumatic event only. Table 2 explains our longitudinal rating of spiritual coping with definitions and examples. Although the scale ranks from −4 to +4, indicating the overall negative and positive effects, the rating is not a mere linear function. The multidimensional construct of spiritual coping combines the use, the effect, and the dynamics of spiritual coping. The use of spiritual coping behaves more like a curve, with zero being the nadir (no spiritual connection and no effect) and the maxima (±4) reflecting extreme use of spiritual coping with positive/negative effects.

For example, a continuous spiritual seeker who feels lost in life and attempts suicide is categorized as −4, whereas a spiritual experience triggering a positive transformation is rated as +4. Persistent struggle with unquestioned spiritual beliefs (e.g., karma, hell) (−3) is opposed to post-traumatic spiritual growth/transformation (+3). Ambivalent spiritual coping with fluctuating effects is categorized as −2, whereas finding benefit in consistent spiritual practices is categorized as +2. Feeling guilty about not having a spiritual connection was rated as −1 and the absence of elaborate use or any effect of spiritual coping as +1.

In addition, the longitudinal rating took into account that use and effect of spiritual coping may fluctuate over time. Rating longitudinally captures whether spiritual disengagement at the time of trauma converts into future effective spiritual coping. Intense trauma often triggers dynamics and reexamination of one's spirituality. Static spirituality is more prevalent in those who do not critically reflect or elaborate on their spirituality.

In our study, some participants experienced spirituality as a central driving force that influences the person's life. Participants who rated +4 on the scale of the Longitudinal Rating of Spiritual Coping (Table 2) found ways to use spirituality to benefit them, such as complete surrender to God's will or a higher being. For instance, in one interview, the participant related how she has faced extreme adversity in her life—imprisonment, battling with drug addictions, having a low socioeconomic status, and other numerous family stressors, including death of a loved one to AIDS. However, all these stressors became manageable to her since she had started to use spirituality to cope. She stated that HIV had “opened her eyes” and this transformation had led her to becoming a Christian. The participant displayed spiritual surrender with respect to her HIV infection and believed that God will heal her and she could “live up to 101 years of age.” Furthermore, she admits: “The medicine made me real sick, I lost my hair, weight, and was very depressed. And these are only some of the side effects. So I'm leaving it in the hands of the Lord.” The participant recalled that the death of a friend had profoundly impacted her life. She continued by stating: “It changed my life, the way I was living. The drugs, alcohol, fornication with married men, all that stopped” and it made her grow more religious. She even attributed this event to “saving” her and God blessing her with two more children. She also described spiritual experiences, such as feelings of exaltation—she feels higher, she feels like she's “moving up” and “when the spirit comes upon me, I feel it.” She further relates that she has received HIV from “doing drugs; not as punishment (…), just something I had to go through in this life because we all have to go through something. It led me to God.” This participant, faced with multiple hurdles in her life, has put her life into God's hands.

Physicians' lack of awareness of negative spiritual coping

On the other pole, in some cases, spiritual coping had a long-lasting negative effect and became at times even a stressor in itself. Participants who rated −4 on the Longitudinal Rating of Spiritual Coping scale, experienced anger towards spiritual presence, and feelings of punishment. Overall, they have very negative life experiences, yet hold spiritual presence accountable for their life. Surrender may be present, but if so, it is used in a negative way (as an avoidance strategy). For instance, in one case, a participant who grew up as a Baptist identified himself as religious up until he was diagnosed with HIV, but he began to lose his faith afterwards. He testified, “The longer this has happened, the more empty I have become spiritually or religiously, (…) I feel like I don't have a soul right now. My life, my entire world has turned upside down (…) drinking a lot, you know…angry, violent; (…) I just continued an abusive path.” The “worst” for his spiritual turnaround is that his disconnectedness from God had impaired his son from forming a relationship with God. This participant had been struggling to re-engage into the church community. Importantly, participants who experienced negative effects of spiritual coping did not talk to their physicians about their struggle and were not asked by their physicians how they used their spirituality to cope.

Frequency and socio-demographic aspects of longitudinal spiritual coping

As shown in Fig. 2, 65% used spirituality with a positive effect over time to cope with trauma (spiritual coping >1), no effect (between±1) was prevalent in 28%, whereas only 7% had negative effects (<−1). Mean spiritual coping differed by gender (F=9.72, df 1,174, p=0.002), sexual orientation (F=6.98, df 1,172, p=0.009), and ethnicity (F=5.48, df 1,174, p = −0.020) (Fig. 3).Specifically, positive effective spiritual coping (>1) occurred more frequently among female (83% vs. 57%, LR=11.58, p=0.001), heterosexual (77% vs. 55 %, LR=8.94, p<0.003), and African American participants (77% vs. 51%, LR=7.88, p=0.009). No effect of spiritual coping (0) was more prevalent among Whites compared to other ethnicities (12% vs. 3%, LR=4.30, p=0.038).

FIG. 3.

Socio-demographic differences in longitudinal spiritual coping. Mean scores of longitudinal rating of spiritual coping (scale range −4 to +4) stratified by gender, sexual orientation, and ethnicity.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine longitudinally how effective PLWH use their spirituality to cope with trauma to help guide PLWH so they may recognize how to use spirituality for effectively coping with traumatic events. In our study population, almost all PLWH were spiritual in the sense of feeling connected to a higher presence and used their spirituality to cope with trauma, which is consistent with the findings from Cotton et al.33 In line with other studies in PLWH,34–36 spirituality was particularly beneficial for women, heterosexuals, and African Americans, whereas Non-Latino Whites made less use of spiritual coping. For the majority, spiritual coping was positively effective over time, which is also supported by other studies.37–40

In particular, religious stigma often prevented participants from being open about their HIV status, which dovetails the results of another qualitative study on African American gay men, experiencing religious homophobia.41 Spirituality, as part of the problem, is a known phenomenon in coping research,26,42 which was found to be associated with negative health outcomes in longitudinal studies in people with HIV.19,43

What this study identified is that spiritual coping fluctuates over time, and that spiritual coping is more than the sum of single spiritual aspects and needs to be seen in a longitudinal context within the dynamics of the three functional components of coping (stressor, self, reaction). For some participants in our study, the initial reaction to a stressor is spiritual struggle, conflict or anger (which Pargament classifies as “negative spiritual coping”).44 However, this paved the way for post-traumatic spiritual growth/transformation. Spirituality is mainly helpful as a source of comfort, empowerment, growth/transformation, gratitude, and community support, as described by others.9,45 Spirituality is an aid on its own for meaning-making and positive reframing, beyond cognitions.

The results of this study have important implications for health care. Although clinicians are often afraid to address the “Gretchen Question” which means to ask directly about spirituality,46 this question is often already the intervention to help coping with trauma.47 The spiritual coding and rating in our study is based on brief interview questions that are recommended by Pargament26 and King and Koenig8 to tap into the topic of spirituality and coping. Taking the 2–5 min to ask these questions may be an effective way to signal genuine care about illness, stigma, and trauma.47

Taking the time to assess spirituality in PLWH may save time and life in the long run and may have far-reaching clinical implications. Most PLWH do not share with their clinicians when they do not take the prescribed HIV treatment as required if they did not feel comfortable to talk about spirituality with their clinicians, which negatively impacts their life expectancy.48–50 For example, if spiritual struggle is present, taking a spiritual assessment may help with resolution.42,47,51 Opening the dialog about spiritual struggle, conflict, guilt, anger, and disengagement may prevent PLWH from a negative spiral of spiritual reactions or even initiate an individual's critical confrontation with negative religious beliefs such as karma or hell. Conversely, when spirituality is a source of meaning and growth and important in medical decision making, PLWH are often comforted by sharing beliefs with their clinician.15–18,48–50,52 This is why clinicians should not defer the spiritual assessment to others, although providing spiritual interventions is best left to experts in spiritual care.47 Koenig et al.47 dovetails our own experience that we as clinicians benefit too from bringing spirituality back to medicine by experiencing both greater work and patient satisfaction.4,53

In US surveys,54,55 about 90% of the patients but only one-third of the clinicians agreed that clinicians should ask about spirituality, whereas fewer than 10% of clinicians actually do so.56 The present study and our prior research in PLWH provide evidence that overcoming the barrier to address spirituality is beneficial for several reasons. First, as shown in this study, most PLWH use their spirituality to cope with trauma. Second, an increase in spirituality after diagnosis20 and a positive view of God19 predict slower disease progression and spiritual transformation is associated with longer survival.18 Third, spirituality plays a role in medical decision-making, adherence, quality of life, and clinician–patient relationship.12,15,16,18,48–50,52 Finally, it is important to assess the spiritual needs in order to identify people who may benefit from spiritual intervention. Potentially, spirituality-based interventions may aid in trauma treatment, as some experimental studies suggest.57–59

As Pargament60 points out, the critical question is not if but how spirituality should be assessed in the clinical setting. Before addressing the topic of spirituality, clinicians need to establish a relationship in which people feel comfortable to open up about their spirituality.53 If someone indicates that spirituality is not important to her/him, there is probably no need for further questions.61 However, it might be that this individual has problems with spirituality that may not be uncovered, when not asked for. Nevertheless, tackling spirituality in those who do not feel spiritually connected, which is more common in White gay men, may negatively affect the relationship to the individual. Vigilance is required not to offend one's spiritual belief system.26,61,62

In PLWH who are spiritually engaged, the dynamics of spiritual coping deserve special attention. In coping with trauma, spirituality may change over time from being a useful resource to being ineffective or even harmful.63 Clinicians can encourage the process of formative evaluation of the effectiveness of the individual's coping style. This study further corroborates our prior findings: those who are more spiritually engaged are more likely to reap the positive benefits of spirituality but are also at higher risk of negative effects of spirituality.

The three major limitations of this study include a cohort effect, sample bias, and interviewer bias. The cohort effect occurred through PLWH who died or did not feel well enough to visit our study site, which may have produced a bias towards positive spiritual coping, although participants would have received a rating based on initial participation in the study. In addition, this study initially excluded people with substance use dependence, dementia, active psychosis, and people who could not speak English. Thus, frequencies in this study are not representative for the population of PLWH in South Florida and may not be generalizable to other cultural contexts.

Spiritual coping can be reliably assessed in the clinical setting following the questions recommended by King and Koenig8 and Pargament26 and by using our rating scale. It is hoped that this longitudinal examination of spiritual coping in PLWH will provide useful information to guide people dealing with traumatic events based on spiritual coping. For the majority of our participants, spirituality is an effective and useful tool to cope with trauma. Even initial spiritual struggle can catalyze effective spiritual coping long-term. However, those who are engaged in spiritual struggle are at particular risk for experiencing harmful effects. Therefore, it is important for clinicians to know how to integrate spirituality constructively into trauma-treatment. Clinicians can encourage the critical evaluation of adaptive use of spiritual coping.

Our future longitudinal analysis will examine whether spiritual coping is associated with healthier behavior, better health, and longer survival with HIV [Kremer H, Ironson G, Kaplan L, et al. (under submission) Spiritual Coping Predicts HIV Disease Progression and Transmission over Four Years. AIDS Care].

Acknowledgments

We thank the Templeton Foundation for the 2-year funding of this secondary data analysis and the NIH (R01MH53791 and R01MH066697, PI: Gail Ironson) and the Metanexus Foundation for financing the longitudinal study. Further, we thank all people living with HIV for sharing their personal experiences with us. Finally, we thank the positive survivors research team for running the longitudinal study, in particular, Annie George for conducting most of the interviews, the research assistants Tony Guerra and Marietta Suarez, Franz Lutz for his suggestion to create a Wiki for the coding agenda, and all the students for their enormous help in transcribing and coding of the interviews and essays.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Pargament KI, Koenig HG, Perez LM. The many methods of religious coping: Development and initial validation of the RCOPE. J Clin Psychol 2000;56:519–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pargament KI, McCarthy S, Shah P, et al. Religion and HIV: A review of the literature and clinical implications. South Med J 2004;97:1201–1209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pargament K. The meaning of spiritual transformation. In: Spiritual Transformation and Healing: Anthropological, Theological, Neuroscientific, and Clinical Perspectives; Koss JD, Hefner P, eds. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press, 2006:10–24 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lutz F, Kremer H, Ironson G. Being diagnosed with HIV as a trigger for spiritual transformation. Religions 2011;2:398–409 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ironson G, Solomon GF, Balbin EG, et al. The Ironson-Woods Spirituality/Religiousness Index is associated with long survival, health behaviors, less distress, and low cortisol in people with HIV/AIDS. Ann Behav Med 2002;24:34–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Jager Meezenbroek E, Garssen B, van den Berg M, et al. Measuring spirituality as a universal human experience: A review of spirituality questionnaires. J Relig Health 2012;51:336–354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller WR, Thoresen CE. Spirituality, religion, and health. An emerging research field. Am Psychol 2003;58:24–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King MB, Koenig HG. Conceptualising spirituality for medical research and health service provision. BMC Health Serv Res 2009;9:116-6963–9-116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baldacchino D, Draper P. Spiritual coping strategies: A review of the nursing research literature. J Adv Nurs 2001;34:833–841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Monod S, Brennan M, Rochat E, et al. Instruments measuring spirituality in clinical research: A systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:1345–1357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York, NY: Springer, 1984 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ironson G, Kremer H. Coping, spirituality, and health in HIV. In: The Oxford Handbook of Stress, Health, and Coping. Folkman S, ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2011:289–318 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kremer H, Ironson G. Spirituality and HIV. In: Spirit, Science, and Health: How the Spiritual Mind Fuels Physical Wellness. Plante TG, Thoresen CE, eds. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2007:176–190 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richards TA, Folkman S. Spiritual aspects of loss at the time of a partner's death from AIDS. Death Stud 1997;21:527–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ironson G, Kremer H, Ironson D. Spirituality, spiritual experiences, and spiritual transformations in the face of HIV. In: Spiritual Transformation and Healing: Anthropological, Theological, Neuroscientific, and Clinical Perspectives. Koss JD, Hefner P, eds. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press, 2006:241–262 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kremer H, Ironson G. Everything changed: Spiritual transformation in people with HIV. Intl J Psychiat Medicine 2009;32:243–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kremer H, Ironson G, Kaplan L. The fork in the road: HIV as a potential positive turning point and the role of spirituality. AIDS Care 2000;21:368–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ironson G, Kremer H. Spiritual transformation, psychological well-being, health, and survival in people with HIV. Intl J Psychiat Med 2009;32:263–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ironson G, Stuetzle R, Ironson D, et al. View of God as benevolent and forgiving or punishing and judgmental predicts HIV disease progression. J Behav Med 2011;34:414–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ironson G, Stuetzle R, Fletcher MA. An increase in religiousness/spirituality occurs after HIV diagnosis and predicts slower disease progression over 4 years in people with HIV. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:S62–S68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ironson G, O'Cleirigh C, Fletcher MA, et al. Psychosocial factors predict CD4 and viral load change in men and women with human immunodeficiency virus in the era of highly active antiretroviral treatment. Psychosom Med 2005;67:1013–1021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Folkman S, Lazarus RS. Ways of Coping Questionnaire. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. J Pers Soc Psychol 1989;56:267–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol's too long: Consider the Brief COPE. Intl J Behav Med 1997;4:92–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moskowitz JT, Hult JR, Bussolari C, Acree M. What works in coping with HIV? A meta-analysis with implications for coping with serious illness. Psychol Bull 2009;135:121–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pargament KI. Spiritually Integrated Psychotherapy. New York: The Guilford Press, 2007:381–384 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sarason IG, Johnson JH. The Life Experiences Survey: Preliminary findings. Technical Report SCS-LS-001. Office of Naval Findings 1976 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarason IG, Johnson JH, Siegel JM. Assessing the impact of life changes: development of the Life Experiences Survey. J Consult Clin Psychol 1978;46:932–946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15:1277–1288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mayring P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Grundlagen und Techniken. [Qualitative content analysis. Basics and techniques]. Weinheim, Germany: Deutscher Studien Verlag, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159–174 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cotton S, Puchalski CM, Sherman SN, et al. Spirituality and religion in patients with HIV/AIDS. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:S5–S13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coleman CL, Holzemer WL, Eller LS, et al. Gender differences in use of prayer as a self-care strategy for managing symptoms in African Americans living with HIV/AIDS. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 2006;17:16–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cotton S, Tsevat J, Szaflarski M, et al. Changes in religiousness and spirituality attributed to HIV/AIDS: Are there sex and race differences?. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:S14–S20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McIntosh RC, Rosselli M. Stress and coping in women living with HIV: A meta-analytic review. AIDS Behav 2012;16:2144–2159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coleman CL, Eller LS, Nokes KM, et al. Prayer as a complementary health strategy for managing HIV-related symptoms among ethnically diverse patients. Holist Nurs Pract 2006;20:65–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duggan J, Peterson WS, Schutz M, et al. Use of complementary and alternative therapies in HIV-infected patients. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2001;15:159–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simoni JM, Martone MG, Kerwin JF. Spirituality and psychological adaptation among women with HIV/AIDS: Implications for counseling. J Couns Psychol 2002;49:139–147 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lorenc A, Robinson N. A review of the use of complementary and alternative medicine and HIV: Issues for patient care. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2013;27:503–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Balaji AB, Oster AM, Viall AH, et al. Role flexing: How community, religion, and family shape the experiences of young black men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2012;26:730–737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pargament KI, Ano GG. Spiritual resources and struggles in coping with medical illness. South Med J 2006;99:1161–1162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trevino KM, Pargament KI, Cotton S, et al. Religious coping and physiological, psychological, social, and spiritual outcomes in patients with HIV/AIDS: Cross-sectional and longitudinal findings. AIDS Behav 2010;14:379–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pargament KI, Smith B, Koenig HG, Perez L. Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. J Sci Study Religion 1998;37:710–724 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koenig HG. Religion, spirituality, and medicine: Research findings and implications for clinical practice. South Med J 2004;97:1194–1200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seyringer ME, Friedrich F, Stompe T, et al. The “Gretchen question” for psychiatry—The importance of religion and spirituality in psychiatric treatment. Neuropsychiatry 2007;21:239–247 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koenig HG. Spiritual assessment in medical practice. Am Fam Physician 2001;63:30–33 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kremer H, Ironson G. To tell or not to tell: Why people with HIV share or don't share with their physicians whether they are taking their medications as prescribed. AIDS Care 2006;18:520–528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kremer H, Ironson G, Schneiderman N, Hautzinger M. “Its my body”: Does patient involvement in decision making reduce decisional conflict? Med Decis Making 2006;18:520–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kremer H, Ironson G, Porr M. Spiritual and mind-body beliefs as barriers and motivators to HIV-treatment decision-making and medication adherence? A qualitative study. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2009;23:127–134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sulmasy DP. Spirituality, religion, and clinical care. Chest 2009;135:1634–1642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kremer H, Ironson G, Schneiderman N, Hautzinger M. To take or not to take: Decision-making about antiretroviral treatment in people living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2006;20:335–349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kremer H. Die Suche nach der Balance ist ein Thema, das uns verbindet. [The Search for Balance is a central subject connecting us: Integral care for people affected by or infected with HIV. Effects of art-therapy and psychological support on coping.]. In: AIDS–Neue Perspektiven, Therapeutische Erwartungen. Die Realitaet 1997. Jaeger H, ed. Aids und HIV-Infektionen in Klinik und Praxis Landsberg/Lech, Germany: Ecomed; 1997:200–201 [Google Scholar]

- 54.King DE, Sobal J, Haggerty J 3rd, et al. Experiences and attitudes about faith healing among family physicians. J Fam Pract 1992;35:158–162 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Monroe MH, Bynum D, Susi B, et al. Primary care physician preferences regarding spiritual behavior in medical practice. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:2751–2756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chibnall JT, Brooks CA. Religion in the clinic: The role of physician beliefs. South Med J 2001;94:374–379 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kemppainen J, Bormann JE, Shively M, et al. Living with HIV: Responses to a mantram intervention using the critical incident research method. J Altern Complement Med 2012;18:76–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bormann JE, Aschbacher K, Wetherell JL, et al. Effects of faith/assurance on cortisol levels are enhanced by a spiritual mantram intervention in adults with HIV: A randomized trial. J Psychosom Res 2009;66:161–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bormann JE, Carrico AW. Increases in positive reappraisal coping during a group-based mantram intervention mediate sustained reductions in anger in HIV-positive persons. Int J Behav Med 2009;16:74–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pargament KI, Saunders SM. Introduction to the special issue on spirituality and psychotherapy. J Clin Psychol 2007;63:903–907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Koenig HG. STUDENTJAMA. Student Journal of America Medical Association. Taking a spiritual history. JAMA 2004;291:2881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Richards PS, Bartz JD, O'Grady KA. Assessing religion and spirituality in counseling: Some reflections and recommendations. (Issues and Insights). Couns Values 2009;54:65–79 [Google Scholar]

- 63.McConnell KM, Pargament KI, Ellison CG, Flannelly KJ. Examining the links between spiritual struggles and symptoms of psychopathology in a national sample. J Clin Psychol 2006;62:1469–1484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]