Abstract

In this study, Candida glabrata, an efficient pyruvate-producing strain, was metabolically engineered for the production of the food ingredient diacetyl. A diacetyl biosynthetic pathway was reconstructed based on genetic modifications and medium optimization. The former included (i) channeling carbon flux into the diacetyl biosynthetic pathway by amplification of acetolactate synthase, (ii) elimination of the branched pathway of α-acetolactate by deleting the ILV5 gene, and (iii) restriction of diacetyl degradation by deleting the BDH gene. The resultant strain showed an almost 1∶1 co-production of α-acetolactate and diacetyl (0.95 g L−1). Furthermore, addition of Fe3+ to the medium enhanced the conversion of α-acetolactate to diacetyl and resulted in a two-fold increase in diacetyl production (2.1 g L−1). In addition, increased carbon flux was further channeled into diacetyl biosynthetic pathway and a titer of 4.7 g L−1 of diacetyl was achieved by altering the vitamin level in the flask culture. Thus, this study illustrates that C. glabrata could be tailored as an attractive platform for enhanced biosynthesis of beneficial products from pyruvate by metabolic engineering strategies.

Introduction

Diacetyl is known to be the major component in butter [1], and is widely used in artificial butter flavoring, margarines, or similar oil-based products to impart butter flavor to the final product. When compared with diacetyl production through chemical synthesis, microbial production of diacetyl is more safe and environmental-friendly. Various prokaryotic organisms such as lactic acid bacteria and Enterobacter aerogenes have been studied for their potential role in diacetyl production (Table 1). In these bacteria, acetolactate synthase (ALS) catalyzes the condensation reaction of pyruvate to α-acetolactate, which is subsequently converted to diacetyl through non-enzymatic decarboxylation (NOD) in the presence of oxygen. The intermediate α-acetolactate can be channeled to acetoin through acetolactate decarboxylase (ALDB). In addition, diacetyl can be converted to acetoin and 2,3-butanediol in a two-step reduction process by diacetyl reductase (DR) and butanediol dehydrogenase (BDH) [2].

Table 1. Comparison of diacetyl production using different microorganisms in terms of culture medium, engineering strategies, and performance.

| Organisms | Year | Culture medium | Engineering strategies | Diacetyl (g L−1) | Yield (mol mol−1) | Reference |

| Lactobacillus casi | 2009 | MRS | Deletion of LDH and the E2 subunit of PDHc, overexpression of ALS | 1.4 | 0.15 | [3] |

| Lactococcus lactis | 2000 | Potassium phosphate buffer with 0.5% glucose | Overexpression of NOX, deletion of ALDB | 0.38 | 0.16 | [6] |

| Lactococcus lactis | 2012 | Reconstituted skim milk with 1% glucose | Overexpression of NOX, deletion of ALDB | 0.36 | 0.07 | [7] |

| Lactococcus lactis subsp. latis biovar diacetylactis | 2000 | MRS | Attenuation of LDH and ALDB | 0.52 | 0.05 | [4] |

| Enterobacter aerogenes | 2009 | Chemically defined medium | A UV mutant with decreased activities of ALDC, LDH and DR | 1.35 | 0.04 | [5] |

| Streptococcus thermophilus | 2007 | Reconstituted skim milk | Inactivation of ALDB | 0.02 | - | [8] |

| Candida glabrata DA-3 | 2013 | Chemically defined medium | Overexpression of ALS, deletion of AHAIR and DR, medium optimization | 4.70 | 0.10 | This study |

Several metabolic engineering strategies have been designed to improve diacetyl production (Table 1). To increase the carbon flux toward the α-acetolactate pathway for diacetyl production, ALS was overexpressed and the pyruvate alternative pathways were blocked [3]. In addition, a combined inactivation of ALDB was found to be necessary to reroute the metabolic flux from acetoin to diacetyl synthesis. Monnet et al. showed that Lactococcus lactis mutants with low ALDB and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activities were able to overproduce diacetyl and α-acetolactate [4]. In another study, a mutant strain of E. aerogenes with decreased ALDB, LDH, and DR activities was developed, and a maximum diacetyl titer of 1.35 g L−1 was achieved [5]. Furthermore, NADH oxidase (NOX) overexpression in L. lactis was reported to be an efficient strategy to reroute the metabolic flux away from lactate production toward oxidized products [6], [7]. Moreover, a combination of NOX overexpression with ALDB inactivation in L. lactis was observed to reroute 80% of pyruvate produced from glucose breakdown to diacetyl synthesis via α-acetolactate [6]. However, most of these studies had been based on lactic acid bacteria [3], [6]–[8], and were aimed at conferring intense butter aroma to products such as cheese and yogurt. Although the diacetyl yields of some engineered strains have been impressive, the final diacetyl titers have been low for efficient purification and large-scale diacetyl production (Table 1).

The multivitamin auxotrophic yeast Candida glabrata CCTCC M202019 is a well-established microorganism used for the industrial production of pyruvate [9]. The biosynthetic pathway of diacetyl in C. glabrata is similar to that in other bacteria. However, it was identified that C. glabrata does not produce the enzyme ALDB [10], which competes with diacetyl for α-acetolactate. Moreover, it was found that the concentrations of thiamine (cofactor for pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDHc) and pyruvate decarboxylase (PDC)), nicotinic acid (NA; cofactor for glycolysis and PDHc), pyridoxine, and biotin (cofactor for pyruvate carboxylase) in the medium could affect the corresponding enzymes [9]. It has been reported that under optimal concentration of vitamins, C. glabrata could produce byproducts at low level and block most of the carbon flux at the node of pyruvate (C. glabrata can accumulate pyruvate extracellularly with a yield of 0.635 g (g glucose)−1) [11], a key precursor of diacetyl. These advantages make C. glabrata a promising alternative host for diacetyl production.

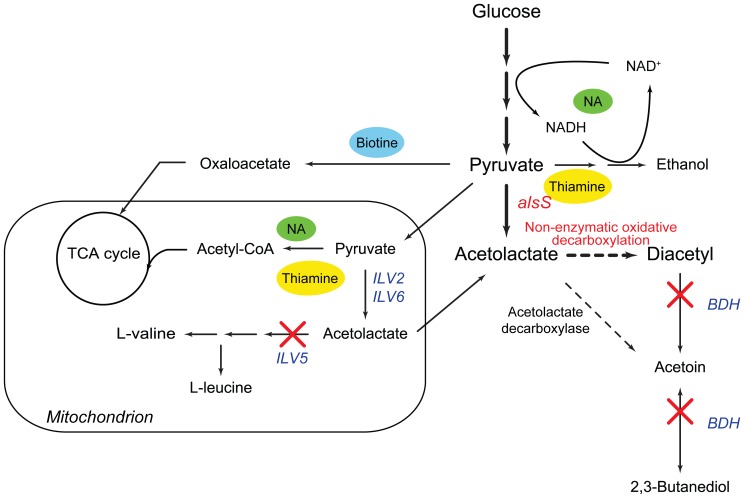

In this study, C. glabrata CCTCC M202019 was tailored for diacetyl production (Figure 1). With the aim of redirecting the carbon flux to diacetyl from the pyruvate node, the accumulation of α-acetolactate was first enhanced through overexpression of the ALS encoded by the alsS gene from Bacillus subtilis. Then, the branched pathway of α-acetolactate and degradation of diacetyl were eliminated by deleting the genes ILV5 and BDH, respectively. The addition of metal ions to the medium enhanced the NOD of α-acetolactate to diacetyl, and re-optimization of the vitamin levels was an essential process to achieve increased diacetyl production.

Figure 1. Illustration of diacetyl metabolic pathway and pyruvate metabolism in engineered C. glabrata.

The red marks indicate metabolic modifications performed in this study, and the cytosolic ALS encoded by alsS was from B. subtilis. Additional descriptions of the reactions with thiamine and NA as cofactors are provided in Table S1.

Results

Overexpression of ALS Leads to Diacetyl Production

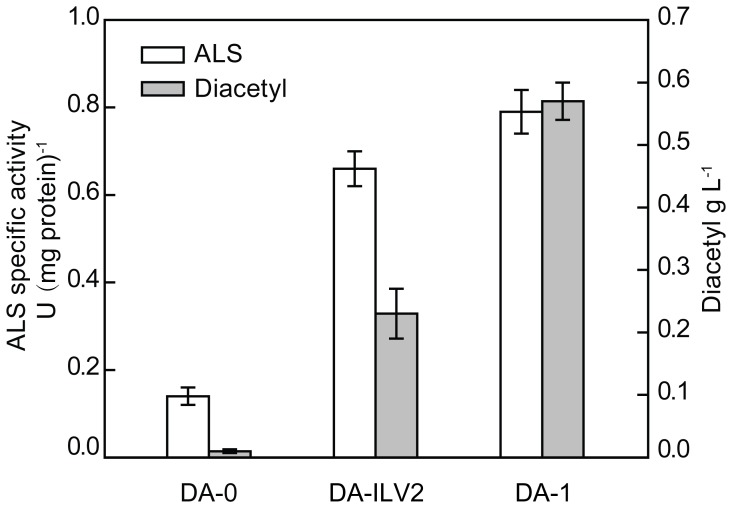

To select the right ALS as the overexpression target for diacetyl production, two different ALS enzymes were introduced into C. glabrata, respectively. First, overexpression of the native ALS encoded by the ILV2 gene resulted in a 3.7-fold increase in ALS activity and increased the diacetyl production to 0.23 g L−1 from trace amounts, when compared with the control strain DA-0 harboring empty plasmid (Figure 2). Alternatively, the strain overexpressing the alsS gene encoding ALS obtained from B. subtilis showed a slight increase in the ALS activity and could produce 0.57 g L−1 of diacetyl, when compared with that overexpressing the ILV2 gene (Figure 2). Therefore, the alsS gene was selected for overexpression and the corresponding engineered strain was designated as DA-1.

Figure 2. Evaluation of ALS activity and diacetyl production using different ALS enzymes.

The ALS activities were determined in cells at mid-log growth phase of batch-flask fermentation. The mean values of three independent experiments are shown. The error bars indicate the respective standard deviations.

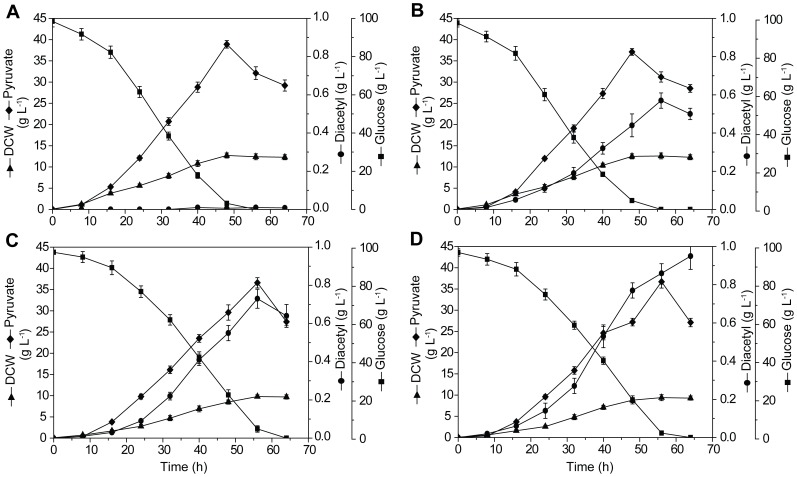

The fermentation parameters of the engineered strain DA-1 and control strain DA-0 were compared. First, the growth rate of DA-1 and its biomass concentration were noted to be slightly lower than those of DA-0 (Figure 3A and 3B). In strain DA-0, there was almost no carbon flux in the diacetyl metabolic pathway (Table 2). In contrast, with increased ALS activity in strain DA-1, the ability to accumulate α-acetolactate was significantly upregulated, leading to diacetyl production. The final α-acetolactate and diacetyl productions were 0.61 and 0.57 g L−1, respectively. In addition, accumulation of α-acetolactate also resulted in the increased productions of L-valine, acetoin, and 2,3-butanediol, suggesting increased carbon fluxes in the branched pathway of α-acetolactate and degradation pathway of diacetyl (Table 2). In response to the diversion of carbon flux into α-acetolactate pathway, strain DA-1 showed a 4.7% decrease in pyruvate production, when compared with strain DA-0, and the ethanol accumulation level remained constant (Table 2).

Figure 3. Fermentation profile for cell growth and product accumulation during shake-flask culture of the control strain DA-0 (A) and the engineered strains DA-1 (B), DA-2 (C), and DA-3 (D).

Table 2. Comparison of fermentation results obtained with metabolically engineered C. glabrata strains and the control strain.

| Strains | Pyruvate | Acetolactate | Diacetyl | Acetoin | 2,3-Butanediol | Valine | Leucine | Ethanol |

| DA-0 | 38.9±0.7a | 0.01±0.00 | 0.01±0.00 | 0.03±0.00 | 0.03±0.01 | 0.02±0.00 | 0.01±0.00 | 1.76±0.14 |

| DA-1 | 37.1±1.0 | 0.61±0.06 | 0.57±0.07 | 0.21±0.03 | 0.23±0.04 | 0.03±0.00 | 0.00±0.00 | 1.69±0.09 |

| DA-2 | 36.6±1.2 | 0.83±0.07 | 0.73±0.05 | 0.23±0.02 | 0.28±0.02 | – | – | 1.86±0.12 |

| DA-3 | 36.7±1.5 | 0.86±0.05 | 0.95±0.07 | 0.11±0.00 | 0.08±0.00 | – | – | 1.80±0.07 |

Concentration of fermentation products (g L−1).

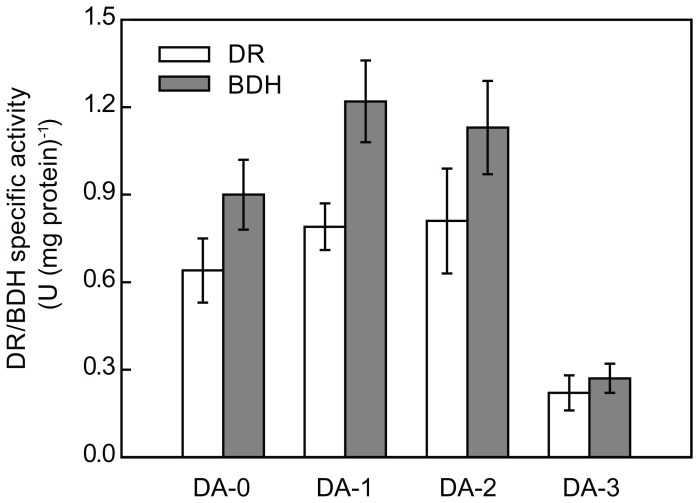

Host Gene Deletion to Increase Diacetyl Production

The ILV5 gene, encoding acetohydroxy acid reductoisomerase, was deleted in the strain DA-1 to form DA-2. As shown in Table 2, strain DA-2 exhibited 28% higher diacetyl production and 37% higher α-acetolactate accumulation than DA-1. The deletion of ILV5 also led to a slight increase in the accumulation of acetoin and 2,3-butanediol. To produce strain DA-3, the BDH gene was deleted in strain DA-2. Although deletion of the BDH gene could not completely disrupt the activities of DR and BDH (Figure 4), it did increase diacetyl production by lowering acetoin formation from 0.23 to 0.11 g L−1 and 2,3-butanediol formation from 0.28 to 0.08 g L−1 (Table 2). The strain DA-3 showed an almost 1∶1 co-production of α-acetolactate and diacetyl (0.95 g L−1). Table 2 also shows that the changes in pyruvate and ethanol concentrations of the cultures of strains DA-2 and DA-3 were not substantial (<10%), when compared with those of their respective controls. These results indicated that the deletion of ILV5 and BDH genes effectively redirected the flux at the α-acetolactate and diacetyl node, but had no apparent effect on the flux distribution around the pyruvate node.

Figure 4. Comparison of DR and BDH activities in the engineered strains and control strain.

The activities of DR and BDH were determined in cells at mid-log growth phase of batch-flask fermentation. The mean values of three independent experiments are shown. The error bars indicate the respective standard deviations.

It should be noted that the deletion of ILV5 introduced auxotrophy for branched-chain amino acids and D-pantothenate. With the addition of sufficient nutrients, the growth rate of strain DA-2, with a value of 0.12 h−1, was lower than that of DA-1 (0.15 h−1), and the biomass concentration of DA-2 was 81.2% of that of DA-1 (Figure 3B and 3C). In addition, strain DA-2 also showed lower glucose consumption rate, when compared with strain DA-1 (Figure 3B and 3C). On the other hand, the additional deletion of BDH in DA-2 had no effect on the growth rate and biomass concentration, and the glucose consumption rates of strains DA-2 and DA-3 were identical (Figure 3C and 3D).

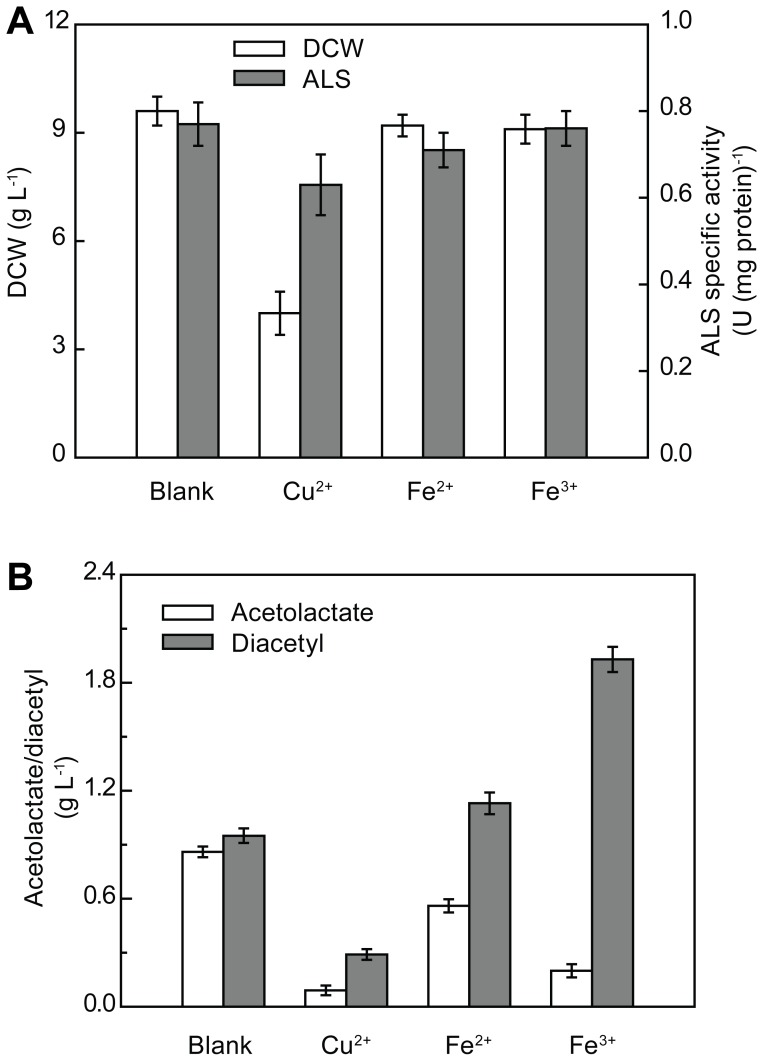

Fe3+ Enhanced NOD of α-Acetolactate to Diacetyl

In order to achieve optimal production of diacetyl alone, rather than co-production of α-acetolactate and diacetyl, NOD of α-acetolactate to diacetyl should be enhanced. Mohr et al. [12] reported that α-acetolactate can be converted to diacetyl by heating in the presence of metal ions (Cu2+, Fe2+, Fe3+, and Mo6+) or hemin. In the present study, the characteristics of the engineered strain DA-3 in medium containing Cu2+, Fe2+, and Fe3+ were studied. Fe3+ was selected as an accelerator for the decarboxylation of α-acetolactate to diacetyl, because the addition of Fe3+ exhibited lower inhibition for strain growth as well as ALS activity, but preferable oxidant activity, when compared with Cu2+ and Fe2+ (Figure 5). As shown in Table 3, addition of 20 mM Fe3+ led to a two-fold increase in diacetyl production up to a level of 2.1 g L−1 and decreased the accumulation of α-acetolactate by 79.1%. Furthermore, Fe3+ addition also resulted in 75 and 62.5% increase in the accumulation of acetoin and 2,3-butanediol, respectively. These results suggested that the NOD of α-acetolactate to diacetyl could be enhanced by the addition of Fe3+.

Figure 5. Characteristics of the engineered strain DA-3 in medium containing Cu2+, Fe2+, and Fe3+.

(A) Effects of metal ions on cell growth and ALS activity. (B) The ability of metal ions to transform α-acetolactate to diacetyl in the fermentation process. The present data were obtained after optimizing the titers of the metal ions added with respect to diacetyl production and cell growth.

Table 3. Results of fermentation carried out using strain DA-3 with different concentrations of metal ions and vitamins.

| Metal ions/vitamins levels | Controla | A | B | C |

| Consumed glucose (g L−1) | 96.9±1.9 | 96.4±2.5 | 96.8±3.6 | 97.3±2.7 |

| Specific growth rate (1 h−1) | 0.12±0.01 | 0.12±0.02 | 0.19±0.03 | 0.13±0.01 |

| Biomass (g L−1) | 9.3±0.05 | 9.3±0.4 | 15.3±0.7 | 11.2±0.4 |

| Diacetyl (g L−1) | 0.95±0.07 | 2.1±0.2 | 3.5±0.2 | 4.7±0.4 |

| α-Acetolactate (g L−1) | 0.86±0.05 | 0.18±0.02 | 0.25±0.01 | 0.24±0.03 |

| Acetoin (g L−1) | 0.11±0.00 | 0.18±0.01 | 0.51±0.03 | 0.32±0.02 |

| Butanediol (g L−1) | 0.08±0.00 | 0.15±0.02 | 0.36±0.02 | 0.61±0.05 |

| Yield (g (g glucose)−1)b | ||||

| Diacetyl | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| Ethanol | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.13 |

| Biomass | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.12 |

| Pyruvate | 0.38 | 0.36 | 0.16 | 0.10 |

Control: 0 mM FeCl3, 0.02 mg L−1 VB1, 8 mg L−1 NA.

A: 20 mM FeCl3, 0.02 mg L−1 VB1, 8 mg L−1 NA.

B: 20 mM FeCl3, 0.08 mg L−1 VB1, 8 mg L−1 NA.

C: 20 mM FeCl3, 0.08 mg L−1 VB1, 2 mg L−1 NA.

VB1 and NA represent thiamine and nicotinic acid, respectively.

The standard deviation for each yield was below 10%.

Effect of Thiamine and NA levels on Carbon Flux Redistribution

The concentrations of thiamine, NA, pyridoxine, and biotin in the medium were minimized to limit the activities of enzymes responsible for further conversion of pyruvate and achieve increased accumulation of pyruvate. Therefore, we examined whether low concentration of thiamine, the cofactor for ALS (Table S1) [13], limited the production of diacetyl. As shown in Table 3, with the supplementation of 0.08 mg L−1 of thiamine to the medium, a 3.5-g L−1 diacetyl production was achieved, which was 81.3% higher than that of the control (0.02 mg L−1 of thiamine). The concentrations of acetoin and 2,3-butanediol were also found to increase from 0.18 to 0.51 g L−1 and from 0.14 to 0.36 g L−1, respectively. Furthermore, strain DA-3 showed obvious increase in the growth rate and biomass as well as in the accumulation of ethanol. The biomass and ethanol yields increased from 0.09 to 0.15 g (g glucose)−1 and from 0.02 to 0.12 g (g glucose)−1, respectively. As a result, the accumulated pyruvate titer decreased to 15.9 g L−1 with a yield of 0.17 g (g glucose)−1 (Table 3). These results suggested that increased carbon flux was redirected into the TCA cycle and ethanol pathway, in addition to the diacetyl biosynthetic pathway, in the presence of higher concentration of thiamine.

Subsequently, the effect of NA, another cofactor involved in the TCA cycle and ethanol pathway, but not in the diacetyl biosynthesis (Figure 1 and Table S1), on diacetyl production was evaluated. As shown in Table 3, with the decrease in the NA level from 8 to 2 mg L−1, the strain DA-3 first showed a decrease in both growth rate and biomass. However, contrary to the expectation, the yield of ethanol was increased by 13.5%. This increase could be elucidated by the improved NADH/NAD+ ratio from 0.53 to 0.79 (Table 4), suggesting a more reductive intracellular environment. The final diacetyl titer was 4.7 g L−1, which was 34.3% higher than that obtained in the control. Furthermore, the yield of pyruvate was further decreased to 0.12 g (g glucose)−1 (Table 3).

Table 4. Comparison of intracellular NADH/NAD+ concentrations of strain DA-3 at different vitamin levels.

| Vitamin levels | Aa | B | C |

| Intracellular NAD+ (µmol (g DCW)−1) | 7.3±0.7 | 7.8±0.6 | 4.2±0.3 |

| Intracellular NADH/NAD+ ratio | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.79 |

A: 0.02 mg L−1 VB1, 8 mg L−1 NA.

B: 0.08 mg L−1 VB1, 8 mg L−1 NA.

C: 0.08 mg L−1 VB1, 2 mg L−1 NA. VB1 and NA represent thiamine and nicotinic acid, respectively.

Discussion

Due to the excellent performance of C. glabrata as an industrial pyruvate-producing strain, the research on redirecting carbon flux toward the desired pathways and developing a platform strain for the production of other useful bioproducts is quite attractive. In the present study, we demonstrated the successful metabolic engineering of C. glabrata for enhanced production of a target product, using diacetyl as an example. Three metabolic modifications contributed to increased production of diacetyl: (i) directed genetic modification of diacetyl biosynthetic pathway; (ii) enhanced conversion of α-acetolactate to diacetyl in the presence of Fe3+; and (iii) redistribution of the carbon flux around the pyruvate node by manipulating the cofactor (thiamine and NA) levels.

In most of the reported studies, the pyruvate alternative pathway was inactivated to improve diacetyl production (Table 1). In C. glabrata, the carbon flux was blocked at the pyruvate node, which allowed channeling of the carbon flux into diacetyl biosynthetic pathway by direct overexpression of ALS. Two different types of ALS have been reported to exist in microorganisms. One is involved in the biosynthesis of branched-chain amino acids, and its overexpression had been used for enhanced production of diacetyl in Lactobacillus casei or for the production of L-valine in Escherichia coli [3], [14]. The other type of ALS is a catabolic enzyme required for 2,3-butanediol fermentation, and had been employed for the robust production of acetoin or 2,3-butanediol in prokaryotic strains such as B. subtilis, Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, and Klebsiella oxytoca [15]–[17]. In a recent study, the ALS of B. subtilis, encoded by the alsS gene, was overexpressed for improved 2,3-butanediol production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae [18]. These studies led us to investigate the impact of overexpression of the two types of ALS for diacetyl production. In the present study, the ALS from B. subtilis was demonstrated to be more suitable for increased diacetyl production than the native ALS (Figure 2). One reason for this is the stronger preference of the ALS from B. subtilis for pyruvate over 2-ketobutyrate, when compared with that of the native ALS [19]. In addition, the native ALS (Ilv2p) is synthesized in the cytosol as a precursor protein with an N-terminal mitochondrial targeting sequence, which directs import into the mitochondrial matrix [20]. However, the expressed ALS from B. subtilis remains in the cytosol, and this cytosolic localization of ALS could lead to elevated diacetyl production [21].

In yeasts, the precursor of diacetyl, α-acetolactate, can be channeled to L-valine and L-leucine biosynthesis through acetohydroxy acid isomeroreductase encoded by the gene ILV5. Previous studies have reported that overexpression or cytosolic localization of the ILV5 gene could limit diacetyl formation [22], [23]. Accordingly, in the present study, the gene ILV5 was deleted and its suitability for increased diacetyl production was evaluated. It should be noted that Ilv5p is a bifunctional mitochondrial enzyme required for branched-chain amino acid biosynthesis as well as for the stability of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and its parsing into nucleoids [24], [25]. It has been reported that the wild-type mtDNA is unstable in Δilv5 mutant, leading to the production of ρ− petites [26]. In the present study, strain DA-2 (Δilv5) showed a distinct decrease in the cell growth rate and maximum dry cell weight (18.8%, Figure 3B and 3C), although sufficient amounts of branched-chain amino acid and calcium pantothenate were added to the culture. This finding indicated that the stability of mtDNA could be affected by ILV5 mutation in strain DA-2. Furthermore, deletion of the ILV5 gene was found to increase the accumulation of α-acetolactate by 37% and diacetyl production by 28% (Table 2). This result suggested that the L-valine and L-leucine biosynthesis was a notable pathway in strain DA-1, which competed with diacetyl for α-acetolactate. It has been reported that diacetyl is reabsorbed by the yeast cells and converted to acetoin and subsequently to 2,3-butanediol by the action of BDH and other not fully characterized ketoreductase(s) [27], [28]. Two genes, BDH1 and BDH2, encoding BDH have been characterized in S. cerevisiae, but only one gene has been detected in C. glabrata through gene annotation [10], [29]. Thus, C. glabrata may probably have other independent genes encoding BDH. In the present study, we showed that the BDH gene product is a major enzyme for DR and BDH activities in C. glabrata, and its disruption could lead to obvious limitation of diacetyl catabolism (Table 2).

Further improvement in the diacetyl-producing strain was achieved by enhancing the conversion of α-acetolactate to diacetyl in the presence of Fe3+. Most of the engineered strains described in previous studies have been reported to exhibit co-production of α-acetolactate and diacetyl following an inefficient NOD of α-acetolactate to diacetyl [4], [6]. In the study by Hugenholtz et al. [6], the final molar ratio of α-acetolactate and diacetyl was 57∶16, and the authors suggested that a more efficient chemical conversion of α-acetolactate to diacetyl could be achieved by extended aeration of the culture medium. In the present study, batch cultures of strain DA-3 were carried out in a 3-L fermentor and the impact of different dissolved oxygen concentrations on diacetyl production was studied. However, the results did not meet the expectations because of the increased volatilization of diacetyl (Table S2). Mohra et al. [12] reported that Cu2+ caused more significant decarboxylation of α-acetolactate to diacetyl than Fe2+ and Fe3+ during steam distillation of milk at pH 3.5. A complex between enediol, formed after decarboxylation of α-acetolactate, and a Cu2+–O2 complex may be involved in the Cu- or Fe-catalyzed diacetyl formation [30]. However, in the fermentation process, not only the ability of metal ions to transform α-acetolactate to diacetyl, but also their influence on cell growth, pyruvate accumulation, and the critical enzymes for diacetyl production should be considered. In the present study, we showed that Fe3+ could be a suitable accelerator for NOD of α-acetolactate to diacetyl, without causing obvious inhibition to cell growth or ALS activity (Figure 5).

The production of diacetyl by C. glabrata was enhanced stepwise, but the carbon flux channeled into the diacetyl biosynthetic pathway accounted for a very low proportion of the total carbon flux (Table 3). In the multi-vitamin auxotrophic C. glabrata, it was observed that the vitamin level in the culture medium could affect the activities of the corresponding enzymes (Figure 1), which also provided a strategy for redirecting the carbon flux by altering the vitamin level [31]. As shown in Table S1, thiamine is a cofactor for ALS, PDHc, ketoglutarate dehydrogenase, and PDC, while NA is involved in the TCA cycle and ethanol formation, but not in diacetyl biosynthesis. In the present study, the thiamine level was proved to be a key factor in redirecting the carbon flux from pyruvate to diacetyl. Increasing the thiamine level also resulted in increased yields of biomass and ethanol (Table 3), suggesting that more carbon flux was channeled into the TCA cycle and ethanol pathway. At this stage, a reduction in the NA level was expected to downregulate the TCA cycle and ethanol pathway, and increase the flux through diacetyl biosynthetic pathway. As expected, strain DA-3 showed obvious decrease in the biomass yield, but further increase in the diacetyl yield because of a lower NA level (Table 3). In addition, we also found that the decreased NA level led to a continuous increase in ethanol accumulation with improved NADH/NAD+ ratio (Tables 3 and 4). Nevertheless, the diacetyl titer increased from 2.1 to 4.7 g L−1, suggesting that redistribution of carbon flux at the pyruvate node was successful achieved by altering the thiamine and NA levels for increased diacetyl production.

In summary, metabolic engineering based on diacetyl metabolic pathway allowed for the development of C. glabrata capable of producing diacetyl. Furthermore, re-optimization of the vitamin level was also found to be necessary for redistributing the carbon flux into the desired pathway and realizing metabolic engineering goals. In the present study, a diacetyl yield of 0.05 g (g glucose)−1 was obtained, and further investigations are required to develop the engineered strain for industrial-scale production of diacetyl. The remaining DR and BDH activities in strain DA-3, which does not possess BDH, resulted in the reduction of diacetyl to acetoin and 2,3-butanediol, and the reduction was more obvious in the presence of higher diacetyl production (Table 3). Therefore, for optimal production of diacetyl, a more efficient inactivation of this reduction should be achieved. This may be accomplished by overexpressing NOX, which could lead to prevention of NADH-dependent reactions, such as acetoin and 2,3-butanediol formation as well as ethanol formation [6], [32].

Materials and Methods

Strains, Plasmids, and Genetic Modifications

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 5. The primers used for gene cloning and deletion are listed in Table S3. The ILV2 and alsS genes were respectively overexpressed with a C. glabrata-specific expression plasmid pYES-PGK1, which was constructed in the frame of plasmid pYES2 by replacing the GAL1 promoter with C. glabrata PGK1 promoter (Figure S1). The ILV5 gene deletion in C. glabrata strain DA-1 was performed by homologous recombination, according to the method previously described [33], which comprised the following steps: construction of the ILV5 deletion frame, efficient electroporation, enrichment with nystatin, and selection on limited medium (Figure S2). Inactivation of the BDH gene was achieved by replacing the BDH ORF with ARG8 (Figure S3). The detailed procedures for genetic modifications are presented in the File S1.

Table 5. Candida glabrata strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strains/plasmids | Genotypes/descriptions | Sources |

| Strains | ||

| FMME019 | C. glabrata Δura3 Δarg8 mutant strain derived from C. glabrata CCTCC M202019 | [33] |

| DA-0 | FMME019 pYES-PGK1 | This study |

| DA-ILV2 | FMME019 pYES-PGK1-ILV2 | This study |

| DA-1 | FMME019 pYES-PGK1-alsS | This study |

| DA-2 | FMME019 Δilv5 pYES-PGK1-alsS | This study |

| DA-3 | FMME019 Δilv5 Δbdh::arg8 pYES-PGK1-alsS | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pYES2 | 2μ, Amp, URA3, PGAL1 | Invitrogen |

| pYES-PGK1 | 2μ, Amp, URA3, PPGK1 | This study |

| pYES-PGK1-ILV2 | C. glabrata ILV2 gene under the control of PGK1 promoter in pYES-PGK1 | This study |

| pYES-PGK1-alsS | Bacillus subtilis alsS gene under the control of PGK1 promoter in pYES-PGK1 | This study |

Media Formulations

Yeast peptone dextrose culture medium (YPD), nitrogen-free minimal medium (NFMM), minimal medium (MM), limited medium (LM), and supplement medium (SM) were used for the construction of the C. glabrata engineered strains, and their compositions were as follows: YPD (g L−1): yeast extract, 10; peptone, 20; and dextrose, 20. NFMM (g L−1): glucose, 20; KH2PO4, 1.0; and MgSO4, 0.5. MM: NFMM with 10 g L−1 of (NH4)2SO4. LM: MM with 5 mg L−1 of branched-chain amino acids (L-valine, L-leucine, and L-isoleucine) and 3 mg L−1 of calcium pantothenate. SM: MM with 40 mg L−1 of arginine (SM-A; for Δarg8 mutant); MM with 80 mg L−1 of uracil and 40 mg L−1 of arginine (SM-UA; for Δura3 Δarg8 mutant); MM with 80 mg L−1 of branched-chain amino acids (valine, leucine, and isoleucine) and 10 mg L−1 of calcium pantothenate (SM-BP; for Δilv5 mutant); and MM with 40 mg L−1 of arginine, 80 mg L−1 of branched-chain amino acids, and 30 mg L−1 of calcium pantothenate (SM-ABP; for Δarg8 Δilv5 mutant).

The medium used for seed culture (medium A) was the corresponding SM according to the genotypes of the engineered strains. For slant culture, 2% agar was added to medium A. The fermentation medium (medium B) contained 100 g L−1 of glucose, 7 g L−1 of urea, 5 g L−1 of KH2PO4, 0.8 g L−1 of MgSO4·7H2O, and 3 g L−1 of sodium acetate. In addition, arginine (0.3 g L−1), branched-chain amino acids (0.5 g L−1), and calcium pantothenate (20 mg L−1) were added to the medium to overcome auxotrophy when necessary. The metal ion solutions were prepared as concentrated solutions and diluted in the corresponding ratio before use. The initial pH of all the media was adjusted to 5.5, and 10 mL of vitamin solution (8 mg L−1 of NA, 0.02 mg L−1 of thiamine, 0.04 mg L−1 of biotin, and 0.4 mg L−1 of pyridoxine-HCl) were added to all the media. All the amino acids, vitamins, and metal ion solutions were filter-sterilized before being added to the medium. All plates contained the corresponding liquid medium with 15 g L−1 of agar.

Culture Conditions

The seed culture inoculated from the slant was cultivated in a 250-mL flask containing 25 mL of medium A on a reciprocal shaker (200 rpm, 30°C) for 24 h. Fermentation was carried out in a 500-mL flask containing 50 mL of medium B. The inoculum's size was 10% (v/v). For flask culture, 40 g L−1 of CaCO3 was used as the pH buffer after dry-heat sterilization at 160°C for 30 min. All cultivations were carried out at 30°C under agitation at 200 rpm in a shaker (HYL-B, Taicang, China).

Quantification of Substrates and Products

Dry cell weight (DCW) was determined according to the method described by Liu et al. [34]. Glucose, pyruvate, ethanol, acetoin, and 2,3-butanediol were analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) using a Dionex Ultimate 3000 series instrument equipped with a refractive index detector (RID, Agilent 1100 series). Analyte separation was achieved by using an Aminex® HPX-87H column (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) with 5 mM H2SO4 as the mobile phase at a flow rate of 0.6 mL min−1. The column and detector temperatures were each set to 35°C throughout the analysis.

Determination of α-acetolactate and diacetyl was accomplished as described in previous reports [12]. In order to restrict spontaneous decarboxylation of α-acetolactate to diacetyl, the pH of the samples was adjusted to 0.5 or below using 4 M H2SO4 before the analysis. The samples were then examined using headspace gas chromatography with flame ionization detector (HS-GC-FID). During headspace at 70°C for 30 min in a low-pH environment, α-acetolactate was converted to acetoin, while diacetyl remained unchanged. Thus, α-acetolactate was quantified from the difference in the concentration of acetoin between the GC and HPLC results. HS-GC-FID analyses were performed using a gas chromatograph (GC-2010; Shimadzu Co., Kyoto, Japan), and analyte separation was accomplished on a capillary column (PEG-20M, 30 m×0.32 mm I.D.). Nitrogen was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.2 mL min−1. The injection and detector temperatures were 200°C and 250°C, respectively, and the temperature program was as follows: 5 min at 40°C, subsequent increase to 180°C at the rate of 10°C min−1, and 5 min at 180°C.

The amino acids were separated by Agilent 1200 HPLC using a 4.0 125-mm Hypersil ODS C18 column. The solvents and gradient conditions employed were as described by Chen et al. [35]. The detection wavelength was set at UV 338 nm. The extraction and detection of intracellular NADH and NAD+ were carried out as described previously [36].

Quantification of Enzyme Activity

The cell extracts for enzyme activity assay were prepared as previously described [34]. The activities of ALS from C. glabrata [37] and B. subtilis [38] were determined as described earlier. The DR and BDH activities were assayed with diacetyl and acetoin as substrates, respectively, as previously reported [39]. The protein concentration was measured by the Lowry method, with bovine serum albumin as the standard [40].

Supporting Information

The detailed procedures for genetic modifications.

(DOCX)

Construction and confirmation of the ALS expressed strains. (A) The construction of expression expression plasmid pYES-PGK1; (B) Analysis of recombinant plasmid pYES-PGK1 with restriction endonulease digestion; (C) Confirmation of positive clones overexpressing ILV2 by restriction endonulease digestion; (D) Colony PCR of positive clones overexpressing alsS. Lane M, 10 kb Marker; Lane 1, pYES-PGK1 with HindIII and NaeI; Lane 2, pYES-PGK1-ILV2 with HindIII and XhoI; Lane 3, pYES-PGK1-ILV2; Lane 4, positive strains overexpressing alsS; Lane 5, control stain DA-0.

(DOCX)

The knockout and confirmation of the ILV5 gene. (A) Construction of fusion frames used for gene deletion; (B) The schematics of gene knockouts; (C) Purified PCR fragments used for ILV5 deletion; (D) Enrichment result of ILV5 mutants on LM; (E) Confirmation of the auxotrophic mutants on SM-A and SM-ABP plates; (F) Colony PCR of the DA-2 positive clones. Lane M, 10 kb DNA Marker; Lane 1, ILV5 knockout frame; Lane 2, ILV5 left arm; Lane 3, ILV5 right arm; Lane 4–5, strain DA-2; Lane 6, control stain DA-1.

(DOCX)

The knockout and confirmation of the BDH gene. (A)The construction of BDH knockout frame for BDH inactivation; (B) Purified PCR fragments used for BDH inactivation. Lane M, 10 kb DNA Marker; Lane 1, Δbdh::arg8 cassette; Lane 2, BDH left arm; Lane 3, ARG8 ORF; Lane 4, BDH right arm; (C) The schematic of gene BDH knockout; (D) Colony PCR of the DA-3 positive clones. Lane 5–6, strain DA-3; Lane 7, control strain DA-2.

(DOCX)

The reactions with thiamine or NA as cofactor in the central metabolic pathway of C. glabrata .

(DOCX)

Comparison of diacetyl production of strain DA-3 under different dissolved oxygen concentration.

(DOCX)

Primers used in this study.

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Linxiang Wang and Shuying Wang of the State Key Laboratory of Food Science and Technology, Jiangnan University, for their experimental assistance with GC analysis and amino acid determination.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Supporting Program for Outstanding National Young Talents, the fund from Wuxi City (CLE01N1111), the Science Foundation for Distinguished Young Scholars of Jiangsu Province (BK2012002), the Program for Innovative Research Team of Ministry of Education of China (IRT1249), the Major State Basic Research Development Program of China (973 Program, 2013CB733600) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (31270079). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Ott A, Fay LB, Chaintreau A (1997) Determination and Origin of the Aroma Impact Compounds of Yogurt Flavor. J Agr Food Chem 45: 850–858. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chuang LF, Collins EB (1968) Biosynthesis of diacetyl in bacteria and yeast. J Bacteriol 95: 2083–2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nadal I, Rico J, Perez-Martinez G, Yebra MJ, Monedero V (2009) Diacetyl and acetoin production from whey permeate using engineered Lactobacillus casei . J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 36: 1233–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Monnet C, Aymes F, Corrieu G (2000) Diacetyl and alpha-acetolactate overproduction by Lactococcus lactis subsp lactis biovar diacetylactis mutants that are deficient in alpha-acetolactate decarboxylase and have a low lactate dehydrogenase activity. Appl Environ Microbiol 66: 5518–5520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhao L, Bao YM, Wang JY, Liu BS, An LJ (2009) Optimization and mechanism of diacetyl accumulation by Enterobacter aerogenes mutant UV-3. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 25: 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hugenholtz J, Kleerebezem M, Starrenburg M, Delcour J, de Vos W, et al. (2000) Lactococcus lactis as a cell factory for high-level diacetyl production. Appl Environ Microbiol 66: 4112–4114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Guo T, Kong J, Zhang L, Zhang C, Hu S (2012) Fine tuning of the lactate and diacetyl production through promoter engineering in Lactococcus lactis. PLoS ONE 7: e36296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Monnet C, Corrieu G (2007) Selection and properties of alpha-acetolactate decarboxylase-deficient spontaneous mutants of Streptococcus thermophilus . Food Microbiol 24: 601–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li Y, Chen J, Lun SY, Rui XS (2001) Efficient pyruvate production by a multi-vitamin auxotroph of Torulopsis glabrata: key role and optimization of vitamin levels. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 55: 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Xu N, Liu L, Zou W, Liu J, Hua Q, et al. (2013) Reconstruction and analysis of the genome-scale metabolic network of Candida glabrata . Mol BioSyst 9: 205–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liu L, Xu Q, Li Y, Shi Z, Zhu Y, et al. (2007) Enhancement of pyruvate production by osmotic-tolerant mutant of Torulopsis glabrata . Biotechnol Bioeng 97: 825–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mohr B, Aymes F, Rea MC, Monnet C, Cogan TM (1997) A new method for the determination of 2-acetolactate in dairy products. Int Dairy J 7: 701–706. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Holtzclaw WD, Chapman LF (1975) Degradative acetolactate synthase of Bacillus subtilis: purification and properties. J Bacteriol 121: 917–922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Park JH, Lee KH, Kim TY, Lee SY (2007) Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for the production of L-valine based on transcriptome analysis and in silico gene knockout simulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 7797–7802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Renna MC, Najimudin N, Winik LR, Zahler SA (1993) Regulation of the Bacillus subtilis alsS, alsD, and alsR genes involved in post-exponential-phase production of acetoin. J Bacteriol 175: 3863–3875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shin SH, Kim S, Kim JY, Lee S, Um Y, et al. (2012) Complete genome sequence of Klebsiella oxytoca KCTC 1686, used in production of 2,3-butanediol. J Bacteriol 194: 2371–2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang Y, Li S, Liu L, Wu J (2013) Acetoin production enhanced by manipulating carbon flux in a newly isolated Bacillus amyloliquefaciens . Bioresour Technol 130: 256–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ng CY, Jung MY, Lee J, Oh MK (2012) Production of 2,3-butanediol in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by in silico aided metabolic engineering. Microb Cell Fact 11: 68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gollop N, Damri B, Chipman DM, Barak Z (1990) Physiological implications of the substrate specificities of acetohydroxy acid synthases from varied organisms. J Bacteriol 172: 3444–3449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Falco SC, Dumas KS, Livak KJ (1985) Nucleotide sequence of the yeast ILV2 gene which encodes acetolactate synthase. Nucleic Acids Res 13: 4011–4027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dasari S, Kolling R (2011) Cytosolic localization of acetohydroxyacid synthase Ilv2 and its impact on diacetyl formation during beer fermentation. Appl Environ Microbiol 77: 727–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mithieux SM, Weiss AS (1995) Tandem integration of multiple ILV5 copies and elevated transcription in polyploid yeast. Yeast 11: 311–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Omura F (2008) Targeting of mitochondrial Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ilv5p to the cytosol and its effect on vicinal diketone formation in brewing. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 78: 503–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bateman JM, Iacovino M, Perlman PS, Butow RA (2002) Mitochondrial DNA instability mutants of the bifunctional protein Ilv5p have altered organization in mitochondria and are targeted for degradation by Hsp78 and the Pim1p protease. J Biol Chem 277: 47946–47953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Macierzanka M, Plotka M, Pryputniewicz-Drobinska D, Lewandowska A, Lightowlers R, et al. (2008) Maintenance and stabilization of mtDNA can be facilitated by the DNA-binding activity of Ilv5p. Biochim Biophys Acta 1783: 107–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zelenaya-Troitskaya O, Perlman PS, Butow RA (1995) An enzyme in yeast mitochondria that catalyzes a step in branched-chain amino acid biosynthesis also functions in mitochondrial DNA stability. EMBO J 14: 3268–3276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gonzalez E, Fernandez MR, Larroy C, Sola L, Pericas MA, et al. (2000) Characterization of a (2R,3R)-2,3-butanediol dehydrogenase as the Saccharomyces cerevisiae YAL060W gene product. Disruption and induction of the gene. J Biol Chem 275: 35876–35885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Duong CT, Strack L, Futschik M, Katou Y, Nakao Y, et al. (2011) Identification of Sc-type ILV6 as a target to reduce diacetyl formation in lager brewers' yeast. Metab Eng 13: 638–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gonzalez E, Fernandez MR, Marco D, Calam E, Sumoy L, et al. (2010) Role of Saccharomyces cerevisiae oxidoreductases Bdh1p and Ara1p in the metabolism of acetoin and 2,3-butanediol. Appl Environ Microbiol 76: 670–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gollop N, Barak Z, Chipman DM (1987) A method for simultaneous determination of the two possible products of acetohydroxy acid synthase. Anal Biochem 160: 323–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Liu L, Li Y, Zhu Y, Du G, Chen J (2007) Redistribution of carbon flux in Torulopsis glabrata by altering vitamin and calcium level. Metab Eng 9: 21–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang Y, San KY, Bennett GN (2013) Cofactor engineering for advancing chemical biotechnology. Curr Opin Biotechnol 6: 994–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhou J, Dong Z, Liu L, Du G, Chen J (2009) A reusable method for construction of non-marker large fragment deletion yeast auxotroph strains: A practice in Torulopsis glabrata . J Microbiol Methods 76: 70–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu LM, Li Y, Li HZ, Chen J (2004) Manipulating the pyruvate dehydrogenase bypass of a multi-vitamin auxotrophic yeast Torulopsis glabrata enhanced pyruvate production. Lett Appl Microbiol 39: 199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chen DW, Zhang M, Shrestha S (2007) Compositional characteristics and nutritional quality of Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis). Food Chem 103: 1343–1349. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liu L, Li Y, Du G, Chen J (2006) Redirection of the NADH oxidation pathway in Torulopsis glabrata leads to an enhanced pyruvate production. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 72: 377–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Poulsen C, Stougaard P (1989) Purification and properties of Saccharomyces cerevisiae acetolactate synthase from recombinant Escherichia coli . Eur J Biochem 185: 433–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Atsumi S, Li Z, Liao JC (2009) Acetolactate synthase from Bacillus subtilis serves as a 2-ketoisovalerate decarboxylase for isobutanol biosynthesis in Escherichia coli . Appl Environ Microbiol 75: 6306–6311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ehsani M, Fernandez MR, Biosca JA, Julien A, Dequin S (2009) Engineering of 2,3-butanediol dehydrogenase to reduce acetoin formation by glycerol-overproducing, low-alcohol Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Appl Environ Microbiol 75: 3196–3205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ (1951) Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem 193: 265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The detailed procedures for genetic modifications.

(DOCX)

Construction and confirmation of the ALS expressed strains. (A) The construction of expression expression plasmid pYES-PGK1; (B) Analysis of recombinant plasmid pYES-PGK1 with restriction endonulease digestion; (C) Confirmation of positive clones overexpressing ILV2 by restriction endonulease digestion; (D) Colony PCR of positive clones overexpressing alsS. Lane M, 10 kb Marker; Lane 1, pYES-PGK1 with HindIII and NaeI; Lane 2, pYES-PGK1-ILV2 with HindIII and XhoI; Lane 3, pYES-PGK1-ILV2; Lane 4, positive strains overexpressing alsS; Lane 5, control stain DA-0.

(DOCX)

The knockout and confirmation of the ILV5 gene. (A) Construction of fusion frames used for gene deletion; (B) The schematics of gene knockouts; (C) Purified PCR fragments used for ILV5 deletion; (D) Enrichment result of ILV5 mutants on LM; (E) Confirmation of the auxotrophic mutants on SM-A and SM-ABP plates; (F) Colony PCR of the DA-2 positive clones. Lane M, 10 kb DNA Marker; Lane 1, ILV5 knockout frame; Lane 2, ILV5 left arm; Lane 3, ILV5 right arm; Lane 4–5, strain DA-2; Lane 6, control stain DA-1.

(DOCX)

The knockout and confirmation of the BDH gene. (A)The construction of BDH knockout frame for BDH inactivation; (B) Purified PCR fragments used for BDH inactivation. Lane M, 10 kb DNA Marker; Lane 1, Δbdh::arg8 cassette; Lane 2, BDH left arm; Lane 3, ARG8 ORF; Lane 4, BDH right arm; (C) The schematic of gene BDH knockout; (D) Colony PCR of the DA-3 positive clones. Lane 5–6, strain DA-3; Lane 7, control strain DA-2.

(DOCX)

The reactions with thiamine or NA as cofactor in the central metabolic pathway of C. glabrata .

(DOCX)

Comparison of diacetyl production of strain DA-3 under different dissolved oxygen concentration.

(DOCX)

Primers used in this study.

(DOCX)