Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of more intensive smoking cessation interventions compared to less intensive interventions on smoking cessation in people with type 1 or type 2 diabetes.

Design

A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials of smoking cessation interventions was conducted. Electronic searches were carried out on the following databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL and PsycINFO to September 2013. Searches were supplemented by review of trial registries and references from identified trials. Citations and full-text articles were screened by two reviewers. A random-effect Mantel-Haenszel model was used to pool data.

Setting

Primary, secondary and tertiary care.

Participants

Adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes.

Interventions

Smoking cessation interventions or medication (more intensive interventions) compared to usual care, counselling or optional medication (less intensive interventions).

Outcome measures

Biochemically verified smoking cessation was the primary outcome. Secondary outcomes were adverse events and effects on glycaemic control. We also carried out a pooled analysis of self-reported smoking cessation outcomes.

Results

We screened 1783 citations and reviewed seven articles reporting eight trials in 872 participants. All trials were of 6 months duration. Three trials included pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation. The risk ratio of biochemically verified smoking cessation was 1.32 (95% CI 0.23 to 7.43) for the more intensive interventions compared to less intensive interventions with significant heterogeneity (I2=76%). Only one trial reported measures of glycaemic control.

Conclusions

There is an absence of evidence of efficacy for more intensive smoking cessation interventions in people with diabetes. The more intensive strategies tested in trials to date include interventions used in the general population, adding in diabetes-specific education about increased risk. Future research should focus on multicomponent smoking cessation interventions carried out over a period of at least 1 year, and also assess impact on glycaemic control.

Keywords: Preventive Medicine, General Medicine (see Internal Medicine)

Strengths and limitations of this study.

It is the first systematic review of randomised trials of smoking cessation interventions in diabetes.

The statistical power of our attempts to pool data is limited by the small number of trials published to date and a relatively small number of participants in the published trials.

Interventions offered and groups studied are heterogeneous.

Available evidence to inform treatment strategies for smoking cessation in type 2 diabetes is limited.

Introduction

For adults with diabetes, as in the wider population, smoking is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events and death. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies on diabetes reported that smoking increased the risk of death by 48%, coronary heart disease by 54%, stroke by 44% and myocardial infarction by 52%.1 The risk for coronary heart disease, stroke and proteinuria is directly related to the number of cigarettes smoked per day.2 3 Patients with diabetes who smoke have higher glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) levels4 and are more likely to experience severe hypoglycaemia.5

People with diabetes who stop smoking are likely to have a lower risk of death and cardiovascular events compared with those who continue to smoke.1 Smoking cessation is also associated with a reduction in levels of albuminuria, improvement of glycaemic control and lipid profile.6 Smoking cessation has been recommended as a routine component of the treatment of diabetes by the American Diabetes Association,7 although evidence to guide best practice is limited.8

People with diabetes are faced with the challenge of extensive changes in their lifestyle, a burden that may be increased by attempts to stop smoking.9 10 Tailoring smoking cessation programmes to the needs of people with diabetes may lead to improved outcomes compared with usual care, but may also further increase the burden of self-management. Concerns have also been expressed regarding weight gain associated with smoking cessation.11

We, therefore, carried out a systematic review of randomised controlled trials reporting the effects of smoking cessation interventions in diabetes to inform clinical practice and identify potential for further research to improve patient outcomes.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

We carried out this systematic review in accordance with the study protocol (see online supplementary appendix 1).12 Peer-reviewed journal articles and conference abstracts that reported the results of a randomised controlled trial and met the following eligibility criteria were eligible for inclusion: trials recruiting non-pregnant adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes who smoked at baseline, evaluating pharmacological or non-pharmacological interventions intended to support smoking cessation (more intensive interventions) compared to usual care, counselling or optional medication (less intensive interventions). We included trials reporting at least one of the following outcomes: (1) smoking cessation, (2) glycaemic control, (3) weight. There were no restrictions on length of follow-up or language of publication. We included trials that did not report biochemically verified smoking cessation to fully capture the available evidence, characterise smoking status as reported in these trials and to add to the available data from which we could analyse effects of interventions on glycaemic control and weight where such additional data were available.

Search strategy

We based our search strategy on that used by the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group13 for identifying randomised controlled trials of smoking cessation together with the Cochrane Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders Group14 search strategy for interventions in type 1 or type 2 diabetes using the high sensitivity options (see online supplementary appendix 2).

We searched the following online databases: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials [The Cochrane Library, Wiley] (Issue 9, 2013), MEDLINE [OvidSP] (1946—present), EMBASE [OvidSP] (1974—present), CINAHL [EbscoHOST] (1980—present), PsycINFO [OvidSP] (1967—present) and Science Citation Index, Social Sciences Citation Index, Conference Proceedings Citation Index- Science & Conference Proceedings Citation Index—Social Science & Humanities [Web of Knowledge] (1945—present). The most recent search date was 3 September 2013. We also searched clinicaltrials.gov, isrctn.org, anzctr.org.au and International Clinical Trials Registry Platform for ongoing trials. References from bibliographies of included trial reports and results of a search on Web of Science Citation Index for those reports were also reviewed. We contacted authors of potentially eligible conference abstracts.

Study selection and data extraction

Two reviewers (AN and RB) independently screened the titles and abstracts of identified citations to select those requiring full-text assessment. Where there was disagreement, a third reviewer (AF) assessed the records to reach a consensus. Full-text articles were further assessed and data were entered into a prespecified table including 12 entry fields (see online supplementary appendix 3). The data extraction table included information on: (1) trial methodology, setting and duration of follow-up; (2) population characteristics; (3) type of intervention and (4) analyses and outcomes.

Data reported for intention-to-treat analyses were selected at the longest follow-up point. We assumed a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes in insulin-treated participants if the type of diabetes was not otherwise specified.

Data analysis

We used the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool to assess risk of bias at the outcome level.15 Bias was assessed in duplicate with disagreements resolved by a third reviewer. The assessed domains were random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment and completeness of outcome data. Trials deemed to have a high risk of detection bias due to assessing only self-reported smoking cessation were not included in the primary analysis of objectively measured cessation data.

The risk ratio (RR) for biochemically verified smoking cessation with 95% CI was the primary outcome measure in this analysis. We made an a priori decision to use the random effect model to take into account the variability of studied populations and intervention types. The meta-analysis was carried out in Review Manager V.5.2.3 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark) using Mantel-Haenszel method, Cochran's χ2 test and the I2 statistic to assess heterogeneity. The main meta-analysis included all measures of biochemically verified smoking cessation outcomes. We also pooled data on self-reported smoking cessation: (1) in all eligible trials and (2) in trials with biochemically verified smoking cessation. We calculated pooled means and SDs and obtained SDs from SEs of the mean using formulas recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration.16

Results

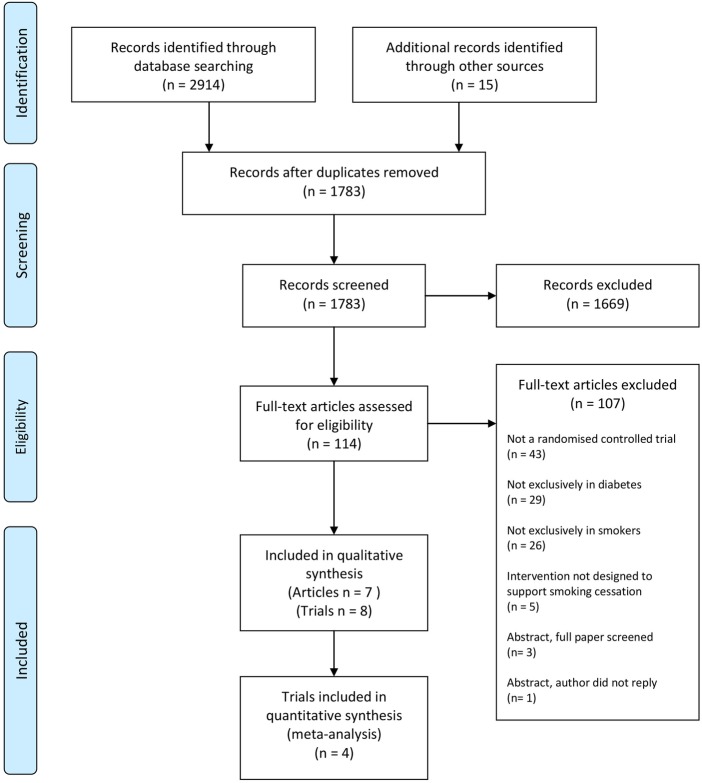

A total of 2914 citations were identified (figure 1) from electronic searches. A further 15 relevant publications were identified as citing or cited by included trial reports. After removing duplicates we screened 1783 citations. Based on the title and abstract, 1669 were assessed as ineligible. The full text of the remaining 114 articles was assessed for eligibility. Most were excluded as not reporting a randomised controlled trial (n=43), or included patients who did not have diabetes (n=29) or did not smoke (n=26). One potentially eligible conference abstract could not be retrieved. We contacted the first author, but received no reply. We selected seven articles reporting eight trials for inclusion.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of literature search, screening and selection for analysis.

Duration and settings

All eight trials were reported in English and had a 6-month maximum duration of follow-up. Two were reported in a single article.17 Three trials were carried out in Europe,1,8–20 two in Asia,21 22 two in Australia17 and one in North America.23

Population

In total, 872 smokers with type 1 or type 2 diabetes participated in the reviewed trials (table 1). Three trials reported in two publications17 21 did not include information on the type of diabetes. Two trials21 22 included only men.

Table 1.

Characteristics of trials included in the analysis

| Source | Setting | Duration, months | Sample size | Mean (SD) age, years | Men, n (%) | T1D, n (%) | T2D, n (%) | More intensive intervention | Less intensive intervention | Percentage followed up | Primary or efficacy outcome* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ardron et al19 | Diabetes clinic, UK | 6 | 60 | 29 (7) | 29 (48) | 50 (83) | 10 (17) | Doctor's advice and information pack followed by a home visit by health visitor | Routine doctor's advice | 100 | Breath CO and urinary cotinine |

| Canga et al20 | 12 primary care practices and 2 hospitals, Spain | 6 | 280 | 55 (15) | 240 (86) | 85 (30) | 195 (70) | Research nurse interview with follow-up by telephone, post and visits; optional NRT | Usual care including advice to stop smoking | 99 | Smoking cessation assessed by urinary cotinine |

| Fowler et al17 | University hospital, Australia | 6 | 18 | 47 (9) | Not reported | 3† (17) | 15† (83) | In newly diagnosed diabetes; counselling (smokescreen programme) at diagnosis | Counselling (smokescreen programme) 2 months after diagnosis | 83 | Plasma cotinine |

| Fowler et al17 | University hospital, Australia | 6 | 16 | 53 (13) | Not reported | 9† (56) | 7† (44) | In pre-existing diabetes; counselling (smokescreen programme) | Diabetes-specific counselling | 88 | Plasma cotinine |

| Hokanson et al23 | Large diabetes centre, USA | 6 | 114 | 54 (9) | 65 (57) | – | 114 (100) | Face-to-face counselling followed by repeated telephone counselling and optional NRT or bupropion | Standard care including referral to cessation programmes | 63 | Self-reported 7-day point prevalence of smoking cessation confirmed by saliva cotinine |

| Ng et al22 | 2 diabetes clinics, Indonesia | 6 | 71 | 56 (9) | 71 (100) | – | 71 (100) | Doctor's advice and visual materials with referral to cessation clinic | Doctor's advice and visual materials | 79 | Self-reported 7-day point prevalence abstinence |

| Sawicki et al18 | Diabetes clinic, Germany | 6 | 89 | 38 (12) | 54 (61) | 72 (81) | 17 (19) | 10 weekly behavioural sessions by a therapist with optional NRT | A single unstructured session by a physician with optional NRT | 100 | Smoking cessation assessed by urine cotinine |

| Thankappan et al21 | 2 diabetes clinics, India | 6 | 224 | 53 (9) | 224 (100) | Not reported | Not reported | Doctor's advice, educational materials and three 30 min non-doctor counselling sessions | Doctor's advice and educational materials | 88 | Self-reported 7-day smoking abstinence |

* Primary outcome unless it was not specified in the article.

† Assumption on the type of diabetes was made on the basis of reported treatment with insulin.

CO, carbon monoxide; NRT, nicotine replacement therapy; T1D, type 1 diabetes; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

Intervention

Five trials assessed either non-pharmacological interventions to support smoking cessation17 19 21 or referral to a smoking cessation clinic.22 Interventions reported in three other trials included optional nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) without bupropion18 20 or with bupropion.23

The intervention was delivered by nursing staff or allied health professionals in three trials18 20 23 and by both doctors and nursing staff or allied health professionals in two trials.19 21 In one trial, the intervention included advice from a doctor and referral to cessation clinic.22 In two other trials, intervention delivery was not specified.17 The interventions were not specifically tailored for people with diabetes apart from the inclusion of educational components focusing on the effects of smoking on the complications of diabetes and glycaemic control.

We did not identify any trials that specifically assessed pharmacological interventions, although among the three identified ongoing trials not included in this review, one European trial assesses the efficacy and safety of smoking cessation with varenicline tartrate in patients with diabetes.24 The two other ongoing trials carried out in North America25 and Asia26 assess the effectiveness of behavioural interventions.

The less intensive intervention comparator groups received usual care, involving advice to stop smoking in three trials,20 22 23 counselling about general health risks of smoking in another three trials17 21 22 and diabetes-specific counselling in one trial.17 In one trial, optional NRT was reported as used in addition to counselling in the comparator group.18

Outcomes

Four of eight trials included a definition of the primary outcome (table 2). In four trials, smoking cessation was biochemically verified using concentration of breath carbon monoxide (CO),19 urinary cotinine19 20 or salivary cotinine.23 Two trials assessed only self-reported cessation,21 22 and two trials reported only a total number of people with biochemically verified cessation in the study population.17 All trials measured smoking cessation as point prevalence abstinence.

Table 2.

Outcomes and effect sizes of interventions to support smoking cessation

| Type of outcome | Study | More intensive intervention | Less intensive intervention | Comparison | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Objective measures | |||||

| Biochemically verified smoking cessation | Ardron et al19 | 0 | 1 (3%) | – | – |

| Canga et al*20 | 25 (17%) | 3 (2%) | Incidence ratio (95% CI) | 7.5 (2.3 to 24.4) | |

| Hokanson et al*23 | 4 (7%) | 2 (4%) | χ2 test for difference in abstinence rate | p=0.077 | |

| Sawicki et al18 | 2 (5%) | 7 (16%) | Difference in point prevalence of cessation | Reported as not significant | |

| Urinary cotinine–creatinine ratio, µg/mg | Ardron et al19 | 7.6 (4.5) | 6.7 (4.4) | – | – |

| Breath CO (µL/L) | Ardron et al19 | 18.2 (10.0) | 19.4 (8.9) | – | – |

| HbA1c <7% (53 mmol/mol) | Hokanson et al23 | 35 (61%) | 43 (75%) | Difference in proportion of patients achieving HbA1c <7% | Reported as not significant |

| Self-reported measures | |||||

| 7-day abstinence | Ng et al*22 | 14 (37%) | 10 (30%) | Allocation effect in logistic regression model | Reported as not significant |

| Thankappan et al*21 | 58 (52%) | 14 (13%) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | 8.4 (4.1 to 17.1) | |

| Number of cigarettes smoked daily | Canga et al20 | 15.5† | 18.1† | Difference in change in mean cigarettes per day from baseline (95% CI) | −3.0 (−1.1 to −4.9) |

| >50% reduction in number of cigarettes smoked daily | Thankappan et al21 | 20 (18%) | 25 (22%) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | 1.9 (0.8 to 4.1) |

| Attempts to quit or reduce smoking | Ng et al22 | 21 (55%) | 16 (48%) | Allocation effect in logistic regression model | Reported as not significant |

| Incidence of smoking relapse | Canga et al20 | 49 (33%) | 14 (11%) | Difference (95% CI) in incidence of relapse | 22.8% (13.6 to 32.0) |

Data presented as number of events (%) or mean (SD).

*Reported as a primary outcome.

†SDs not reported.

CO, carbon monoxide; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin.

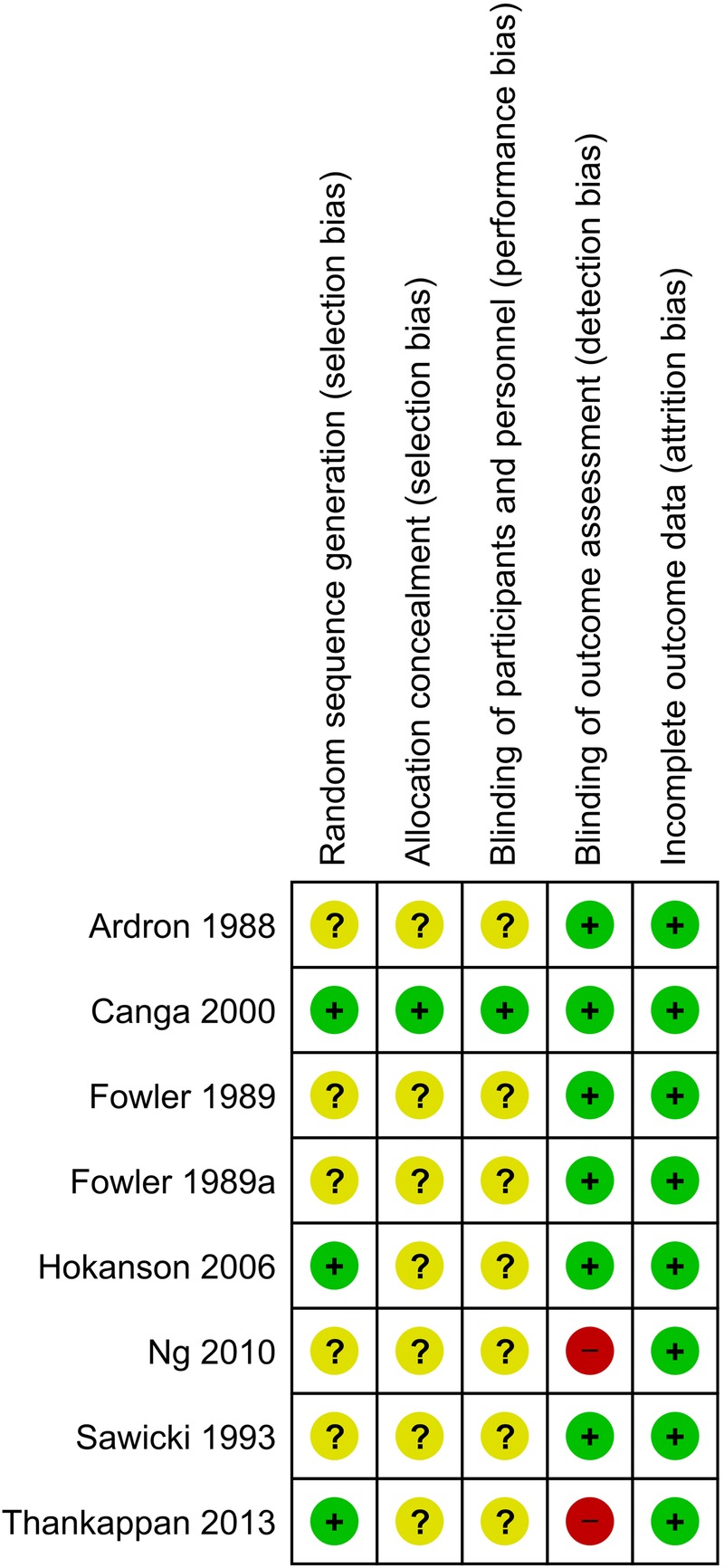

Risk of bias

All trials were deemed to have low risk of attrition bias and most trials were assessed as having low risk of detection bias (figure 2, see online supplementary appendix 4). Most trials provided incomplete information on random sequence generation, allocation concealment and blinding of participants and personnel.

Figure 2.

Summary of authors’ judgements on the risk of bias in reviewed trials.

Primary outcome

Trial findings are summarised in table 2. One article reporting two trials included only the overall number of patients who stopped smoking in both trials.17 Two trials21 22 were excluded from pooled analysis due to high risk of detection bias as a consequence of self-reported cessation outcomes.

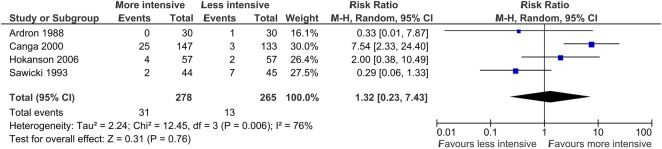

Pooled data from the four trials18–20 23 that reported point prevalence of biochemically verified smoking cessation in both trial arms are summarised in figure 3. For 543 participants, 44 smoking cessation events are reported. The likelihood of biochemically verified smoking cessation was 32% higher in patients who received more intensive intervention compared with less intensive intervention, although this effect was not significant (RR 1.32, 95% CI 0.23 to 7.43).

Figure 3.

Forest plot showing pooled analysis of trials reporting biochemically verified point prevalence of smoking cessation.

There was substantial heterogeneity between the results of trials included in the pooled analysis of the primary outcome (χ2 test for heterogeneity, p=0.006; I2=76%). Two trials,18 19 jointly accounting for 44% of the weight of these results, reported point estimates of effects that suggested a greater likelihood of smoking cessation in the less intensive intervention group compared with the more intensive intervention group. In one trial,19 the only biochemically verified incident of smoking cessation was recorded in a less intensive intervention group patient who stopped smoking after sustaining a myocardial infarction.

In the pooled analyses of self-reported smoking cessation outcomes in (1) all eligible trials and (2) in trials also reporting biochemically verified smoking cessation, participants allocated to more intensive intervention had, respectively, 1.85 times (RR 1.85, 95% CI 0.81 to 4.22) or 1.39 times (RR 1.39, 95% CI 0.28 to 6.92) greater likelihood of cessation compared with patients allocated to the less intensive intervention.

Secondary outcomes

Other outcomes reported related to smoking outcomes and metabolic outcomes (table 2). Continuous measures of urinary cotinine–creatinine ratio and breath CO were reported for one trial,19 but the results were not compared between allocated trial groups. In one trial,23 proportions of patients with HbA1c <7% (53 mmol/mol) in more intensive and less intensive intervention groups were reported at 6 months (61% vs 75%), but were not significantly different (p=0.16). No trials reported other objectively measured short-term or long-term cardiovascular risk or safety data.

Discussion

Despite an excess cardiovascular risk in people with diabetes, we have identified only a small number of trials evaluating the effect of smoking cessation interventions in this group. Interventions tested in the trials were similar to those used in the general population and included counselling, referral and advice, with, for some, the addition of diabetes-specific education. Interventions and comparator groups were heterogeneous and the pooled results did not provide evidence of efficacy for smoking cessation interventions in people with diabetes. Only one trial reported data on glycaemic outcomes, which were not significantly different between intervention groups.

This is, to our knowledge, the first systematic review of randomised trials of smoking cessation interventions in diabetes. Our analysis includes equal numbers of studies reporting positive and negative effect estimates, which reduces the likelihood of publication bias. The statistical power of the meta-analysis is limited by the small number of trials published to date and a relatively small number of participants in the published trials. Limited statistical power may partially explain the lack of significant findings in the pooled analysis. There are too few trials to draw conclusions about the types of intervention, and differences between type 1 and type 2 diabetes. The extent of heterogeneity in interventions, and intervention and comparator groups, also limited our ability to draw conclusions based on our findings. Most of the included trials provided incomplete information on randomisation, allocation concealment and blinding of participants and personnel which may potentially introduce bias at the level of individual trials.

This review does not include trials in which smoking cessation was a part of a more extensive complex intervention and in which only a proportion of patients had diabetes and smoked at baseline. This limited the number of trials to be reviewed and the size of reviewed population, but allowed us to measure specifically the effect of smoking cessation by reducing the extent of performance bias and detection bias arising from multiple interventions and multiple measurements.

Some studies suggest that smokers with diabetes may be more motivated to stop smoking, than the general smoker population27 and more likely to stop smoking after hospitalisation compared with patients without diabetes.28 There is no evidence from our review that, if such motivation is present, it translates into improved outcomes. In other high-risk patient groups, for example, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease29 and cardiovascular disease,30 higher point estimates of the effect of intervention on smoking cessation are reported with most trials extending to 12-month follow-up.

An earlier, narrative review has examined the issues associated with smoking cessation in diabetes and identified some of the reasons why evaluation of smoking cessation interventions in this group may have been dealt with cautiously.8 The datasheets for most recommended first-line smoking cessation medications31 caution against their use in diabetes.8 32 Moreover, studies report that smoking cessation may worsen metabolic profile and glycaemic control33 34 and lead to weight gain.35 We have identified four trials not included in the narrative review, two predating the narrative review.17 19

Further data from randomised trials of interventions evaluating smoking outcomes, weight change and glycaemic control would inform treatment strategies in a population in which smoking cessation is likely to have high absolute benefits.1 The issue of safety of such treatments is partly addressed in an ongoing trial of varenicline for smoking cessation in diabetes,24 but the follow-up period of 6 months is likely to be too short to identify sustained effects. Trials assessing combinations of NRT with varenicline or bupropion in addition to non-pharmacological interventions may, in any case, better reflect clinical practice.31

Despite the potential health benefits of smoking cessation in diabetes, there has been limited work on developing and evaluating tailored interventions to support smoking cessation in these patients. From a health services perspective, it would be important to know whether a tailored intervention is more effective in this patient group than providing the same management as for the general population. Given the high burden of self-management required of people with diabetes, it is possible that integrating an intervention with routine care may be more effective than managing the problem separately. Further work is needed to explore the role of this approach in clinical care using trial designs with follow-up extending to at least 1 year.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mr Joey Yang for help in carrying out an assessment of the risk of bias in included trials.

Footnotes

Contributors: AF and AN designed the protocol and the methods. AN carried out the statistical analysis. All authors contributed to data extraction, drafting of the article and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded with support from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Primary Care Research (grant BZRWUV2).

Competing interests: AF is an NIHR Senior Investigator and also receives funding from Oxford NIHR Biomedical Research Centre.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Qin R, Chen T, Lou Q, et al. Excess risk of mortality and cardiovascular events associated with smoking among patients with diabetes: meta-analysis of observational prospective studies. Int J Cardiol 2013;167:342–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hsu CC, Hwang SJ, Tai TY, et al. Cigarette smoking and proteinuria in Taiwanese men with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med 2010;27:295–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fagard RH. Smoking amplifies cardiovascular risk in patients with hypertension and diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009;32(Suppl 2):S429–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nilsson PM, Gudbjornsdottir S, Eliasson B, et al. Smoking is associated with increased HbA1c values and microalbuminuria in patients with diabetes—data from the National Diabetes Register in Sweden. Diabetes Metab 2004;30:261–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirai FE, Moss SE, Klein BE, et al. Severe hypoglycemia and smoking in a long-term type 1 diabetic population: Wisconsin Epidemiologic Study of Diabetic Retinopathy. Diabetes Care 2007;30:1437–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Voulgari C, Katsilambros N, Tentolouris N. Smoking cessation predicts amelioration of microalbuminuria in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus: a 1-year prospective study. Metabolism 2011;60:1456–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care in diabetes—2013. Diabetes Care 2012;36:S11–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tonstad S. Cigarette smoking, smoking cessation, and diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2009;85:4–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bohlen K, Scoville E, Shippee ND, et al. Overwhelmed patients: a videographic analysis of how patients with type 2 diabetes and clinicians articulate and address treatment burden during clinical encounters. Diabetes Care 2011;35:47–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vijan S, Hayward RA, Ronis DL, et al. Brief report: the burden of diabetes therapy. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20:479–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farley AC, Hajek P, Lycett D, et al. Interventions for preventing weight gain after smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;1:CD006219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.A systematic literature review and meta-analysis to assess the effects of interventions to support smoking cessation in adult patients with diabetes: study protocol. http://www.phc.ox.ac.uk/

- 13.Lancaster T, Stead L, Cahill K, et al. Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group. 2012. About The Cochrane Collaboration (Cochrane Review Groups (CRGs)) http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane/clabout/articles/TOBACCO/sect0.html.

- 14.Richter B, Bergerhoff K, Paletta G, et al. Cochrane Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders Group. 2007. About The Cochrane Collaboration (Cochrane Review Groups (CRGs)) http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane/clabout/articles/ENDOC/frame.html.

- 15.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC, eds. Chapter 8: assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. http://www.cochrane-handbook.org [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins JPT, Deeks JJ, eds. Chapter 7: selecting studies and collecting data. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). A: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. http://www.cochrane-handbook.org [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fowler PM, Hoskins PL, McGill M, et al. Anti-smoking programme for diabetic patients: the agony and the ecstasy. Diabet Med 1989;6:698–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sawicki PT, Didjurgeit U, Muhlhauser I, et al. Behaviour therapy versus doctor's anti-smoking advice in diabetic patients. J Intern Med 1993;234:407–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ardron M, MacFarlane I, Robinson C, et al. Anti-smoking advice for young diabetic smokers: is it a waste of breath? Diabet Med 1988;5:667–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Canga N, Irala J, Vara E, et al. Intervention study for smoking cessation in diabetic patients: a randomized controlled trial in both clinical and primary care settings. Diabetes Care 2000;23:1455–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thankappan K, Mini G, Daivadanam M, et al. Smoking cessation among diabetes patients: results of a pilot randomized controlled trial in Kerala, India. BMC Public Health 2013;13:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ng N, Nichter M, Padmawati RS, et al. Bringing smoking cessation to diabetes clinics in Indonesia. Chronic Illn 2010;6:125–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hokanson JM, Anderson RL, Hennrikus DJ, et al. Integrated tobacco cessation counseling in a diabetes self-management training program: a randomized trial of diabetes and reduction of tobacco. Diabetes Educ 2006;32:562–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Efficacy and safety of smoking cessation with varenicline tartrate in diabetic smokers: (DIASMOKE). http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01387425

- 25.Smoking cessation intervention for diabetic patients: (SSTOP) http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01501877.

- 26.A randomized controlled trial of a tailored intervention compared to usual care on smoking type 2 diabetic patients to promote smoking cessation and improved glycaemic control. http://www.controlled-trials.com/ISRCTN34551140

- 27.Wilkes S, Evans A. A cross-sectional study comparing the motivation for smoking cessation in apparently healthy patients who smoke to those who smoke and have ischaemic heart disease, hypertension or diabetes. Fam Pract 1999;16:608–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duffy SA, Munger A, Karvonen-Gutierrez CA, et al. Post-discharge tobacco cessation rates among hospitalized US veterans with and without diabetes. Diabet Med 2012;29:e96–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pires-Yfantouda R, Absalom G, Clemens F. Smoking cessation interventions for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—a review of the literature. Respir Care 2013;58:1955–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eisenberg MJ, Blum LM, Filion KB, et al. The efficacy of smoking cessation therapies in cardiac patients: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Can J Cardiol 2010;26:73–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.2008 PHS Guideline Update Panel, Liaisons, and Staff Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update U.S. Public Health Service Clinical Practice Guideline executive summary. Respir Care 2008;53:1217–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.British Medical Association and the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain British national formulary. 64th edn. London: BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balkau B, Vierron E, Vernay M, et al. The impact of 3-year changes in lifestyle habits on metabolic syndrome parameters: the D.E.S.I.R study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2006;13:334–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iino K, Iwase M, Tsutsu N, et al. Smoking cessation and glycaemic control in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Obes Metab 2004;6:181–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aubin HJ, Farley A, Lycett D, et al. Weight gain in smokers after quitting cigarettes: meta-analysis. BMJ 2012;345:e4439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.