Abstract

Background

Overall, gastric cancer prognosis remains poor. Detailed characterization of molecular markers that govern gastric cancer pathogenesis is warranted to establish innovative therapeutic options. HIF-1α overexpression has been linked to poor gastric cancer prognosis. However, though researched for years, the prognostic role of HIF-1α in gastric cancer is still controversial. Hence, the objective of the present study was to analyze the prognostic values of HIF-1α, TGF-β, VEGF and pERK1/2 in gastric cancer patients following gastrectomy.

Methods

This study included 446 patients with confirmed gastric cancer who underwent gastrectomy in a single Chinese Cancer Center between 2005 and 2006. Clinicopathologic features, as well as immunohistochemical analysis of TGF-β, HIF-1α, VEGF and pERK1/2 were determined. Long-term survival of these patients was analyzed using univariate and multivariate analyses.

Results

HIF-1α overexpression was more frequent in patients with hepatic metastases (71.6% versus 43.0% in those without hepatic metastases, P = 0.000, χ2 = 23.086) and more frequent in patients with peritoneum cavity metastasis (62.3% versus 43.0% in those without such metastasis, P = 0.000, χ2 = 13.691). In univariate analysis, patients with HIF-1α overexpression had a shorter disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) than patients with weak-expression (DFS: NA VS. 16.8 m, P = 0.000, χ2 = 74.937; OS: NA VS. 25.5 m, P = 0.000, χ2 = 90.594). Importantly, HIF-1α overexpression was a promising prognostic marker for poor survival by multivariate analysis (DFS: HR 2.766, 95%CI 2.136–2.583, P = 0.000; OS: HR 3.529, 95%CI 2.663–4.667, P = 0.000).

Conclusions

HIF-1α overexpression could be considered a useful independent prognostic biomarker in gastric cancer after gastrectomy, and is correlated to both a poor overall survival and disease-free survival in these patients. HIF-1α expression can be used to stratify patients at higher risk for poor prognosis, and is potentially an important therapeutic target in gastric cancer patients.

Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) is one of the most common malignancies in the world. Due to lack of specific early symptoms or effective tumor biomarkers, most patients with GC are not diagnosed until advanced stages. Although there has been great improvement in traditional treatments, the prognosis is still poor, and 30% to 50% of patients show relapse within 5 years of surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy [1], [2]. Thus, it is critical to identify specific markers and develop novel therapeutic strategies for advanced and recurrent gastric cancer.

Angiogenesis is an important determinant of tumor progression. Local tumor recurrence and distal metastasis are both dependent on neovascularization, which is regulated through angiogenesis factors. Several of these factors have been found to play an important role in regulating tumor angiogenesis, and are up regulated concomitantly with rapid growth and early metastasis [3]. Perhaps the best characterized markers are vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), hypoxia inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF-1α), extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) and transforming growth factor- beta (TGF-β) [4].

Hypoxia and oxygen radicals co-operatively promote tumor angiogenesis [5] and cause the activation of HIF-1α, which in turn stimulates VEGF expression [6], [7]. TGF-β is also a major factor responsible for increased VEGF secretion. ERK is a downstream effector of the VEGF signaling pathway, which is regulated through angiogenesis. Clearly, these markers are intertwined as molecular components of angiogenesis. We hypothesized that these pathways might be responsible for tumor progression and metastasis in advanced gastric cancer.

In this study, the correlations of TGF-β, HIF-1α, VEGF and pERK1/2 expressions with clinicopathologic parameters and prognosis were evaluated in patients with gastric cancer. Furthermore, the influence of these markers on the recurrence and distant metastasis were assessed. The findings from the current study will contribute to predicting the risk of recurrence and metastasis of gastric cancer after gastrectomy, and help guide individualized treatment and development of new therapeutic targets.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

Signed informed consent was obtained from all study participants and all clinical investigations were conducted according to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chinese People's Liberation Army (PLA) General Hospital. All samples were procured from the tissue bank of Department of Pathology of PLA General Hospital.

Patient selection and study design

A total of 446 patients with gastric cancer who underwent gastrectomy were enrolled in this study between January 2005 and December 2006 at the Chinese PLA General Hospital (China, Beijing). All patients had undergone initial curative gastrectomy. None of the patients received chemotherapy or radiotherapy before surgery. Only patients who had adequate paraffin embedded tumor specimens were included, and patients with adenosquamous carcinoma or neuroendocrine carcinoma were excluded. Patients lost during follow up or who died within one year of surgery were excluded from the analysis. Tumor staging was done according to the seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer/Union International Control Center TNM staging manual. Lesions staged as I to III with no evidence of metastatic disease were included.

Of the patients enrolled in this study, 348 (78.0%) were male and 98 (22.0%) were female, with a median age of 59.9 years (range 22.9–82.4 years). The median follow-up time was 63.9 months (range 55.0–78.8 months) until the end of the follow-up period (August 1, 2011). The clinicopathological features of the patients that were examined including gender, age, borrmann type, tumor size, tumor histological morphology, lauren classification, tumor differentiation (according to the WHO classification for gastric cancer in 2000), T category, N category, TNM stage (TNM 7th edition by American Joint Committee on Cancer), vascular invasion, perineural invasion, operation, and adjuvant chemotherapy. As of the follow-up end date, 19.7% of the patients (88/446) had hepatic metastases and 29.1% (130/446) had peritoneum cavity metastasis. The clinicopathological characteristics of patients are summarized in Table 1 .

Table 1. Patient characteristics and Univariate analysis (n = 446).

| Characteristics | N (%) | DFS | OS | ||||

| months | P* | χ2 | months | P* | χ2 | ||

| Age(median,years) | 59.9 | ||||||

| <60 | 224 (50.2) | 37.9 | 0.044 | 4.042 | 51.0 | 0.015 | 5.860 |

| ≥60 | 222 (49.8) | 23.5 | 30.9 | ||||

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 348 (78.0) | 28.4 | 0.656 | 0.198 | 42.5 | 0.808 | 0.059 |

| Female | 98 (22.0) | 25.3 | 38.9 | ||||

| Borrmann type | |||||||

| I | 63 (14.1) | 42.6 | 0.000 | 38.858 | 60.7 | 0.000 | 49.961 |

| II+III | 354 (79.4) | 30.9 | 44.8 | ||||

| IV | 25 (5.6) | 6.0 | 9.8 | ||||

| V | 4 (0.9) | 5.8 | 4.0 | ||||

| Tumor Size | |||||||

| <5 cm | 193 (44.3) | 45.6 | 0.000 | 17.518 | 60.7 | 0.000 | 13.375 |

| ≥5 cm | 253 (56.7) | 19.6 | 30.6 | ||||

| Tumor Histological Morphology | |||||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 287 (64.3) | 45.7 | 0.000 | 28.041 | 60.7 | 0.000 | 31.692 |

| Absolute signet ring cell carcinoma | 71 (15.9) | 15.1 | 21.3 | ||||

| Mixed carcinoma | 88 (19.8) | 19.5 | 28.7 | ||||

| Lauren type | |||||||

| Intestinal | 205 (46.0) | 47.0 | 0.000 | 24.151 | 69.6 | 0.000 | 26.506 |

| Diffuse | 204 (45.7) | 17.5 | 26.7 | ||||

| Mixed type | 37 (8.3) | 47.7 | 63.9 | ||||

| Tumor differentiation a | |||||||

| Poor | 354 (79.4) | 24.7 | 0.033 | 4.569 | 33.0 | 0.006 | 7.702 |

| Moderate and High | 92 (20.6) | 44.2 | NA | ||||

| Vessel invasion | |||||||

| No | 279 (62.6) | 33.9 | 0.021 | 5.289 | 48.5 | 0.013 | 6.223 |

| Yes | 167 (37.4) | 18.4 | 29.5 | ||||

| Perineural invasion | |||||||

| No | 313 (70.2) | 37.9 | 0.004 | 8.196 | 51.0 | 0.005 | 7.967 |

| Yes | 133 (29.8) | 18.9 | 27.6 | ||||

| T category | |||||||

| T1 | 17 (3.8) | NA | 0.000 | 60.358 | NA | 0.000 | 57.479 |

| T2 | 32 (7.2) | NA | NA | ||||

| T3 | 66 (14.8) | NA | NA | ||||

| T4 | 331 (74.2) | 18.9 | 29.2 | ||||

| N category | |||||||

| N0 | 97 (21.7) | NA | 0.000 | 116.151 | NA | 0.000 | 104.945 |

| N1 | 94 (21.1) | 47.2 | 69.6 | ||||

| N2 | 109 (24.5) | 22.6 | 29.5 | ||||

| N3 | 146 (32.7) | 11.5 | 20.5 | ||||

| TNM stageb | |||||||

| IA+IB | 27 (6.1) | NA | 0.000 | 163.206 | NA | 0.000 | 148.082 |

| IIA | 22 (4.9) | NA | NA | ||||

| IIB | 83 (18.6) | NA | NA | ||||

| IIIA | 83 (18.6) | 32.1 | 46.7 | ||||

| IIIB | 106(23.8) | 17.5 | 27.1 | ||||

| IIIC | 125(28.0) | 10.2 | 17.8 | ||||

| Operation | |||||||

| D1 | 270(60.5) | 24.0 | 0.435 | 0.610 | 32.8 | 0.170 | 1.883 |

| D2 | 176(39.5) | 33.9 | 50.4 | ||||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | |||||||

| Yes | 282(63.2) | 45.7 | 0.000 | 65.261 | 63.9 | 0.000 | 41.181 |

| No | 164(36.8) | 14.6 | 23.9 | ||||

| Hepatic metastases | |||||||

| Yes | 88(19.7) | 12.0 | 0.000 | 83.481 | 24.6 | 0.000 | 60.630 |

| No | 358(80.3) | 46.2 | 60.7 | ||||

| Peritoneum cavity metastasis | |||||||

| Yes | 130(29.1) | 9.7 | 0.000 | 220.748 | 15.7 | 0.000 | 227.078 |

| No | 316(70.9) | 55.4 | NA | ||||

| TGF-β | |||||||

| Weak-expression | 265(59.4) | 36.4 | 0.053 | 3.759 | 45.3 | 0.139 | 2.187 |

| Over-expression | 181(40.6) | 26.1 | 36.6 | ||||

| HIF-1α | |||||||

| Weak-expression | 229(51.3) | NA | 0.000 | 74.937 | NA | 0.000 | 90.594 |

| Over-expression | 217(48.7) | 16.8 | 25.5 | ||||

| VEGF | |||||||

| Weak-expression | 252(56.5) | 33.9 | 0.161 | 1.968 | 46.7 | 0.217 | 1.526 |

| Over-expression | 194(43.5) | 24.0 | 34.8 | ||||

| pERK1/2 | |||||||

| Weak-expression | 297(66.6) | 37.7 | 0.107 | 2.595 | 49.1 | 0.018 | 5.594 |

| Over-expression | 149(33.4) | 19.8 | 27.8 | ||||

Tumor differentiation according to the WHO classification for gastric cancer in 2000; bTNM stage according to TNM 7th edition by AJCC(American Joint Committee on Cancer); NA Not arrival; *P<0.05.

In the absence of symptoms, physical examination was performed every 3–6 months for 5 consecutive years. Follow-up assessments consisted of physical examination, a complete blood count, liver function test, pulmonary, abdominal, and pelvic CT scan. The date of the first relapse and the date of death were recorded, and survival was calculated from the time of surgery until the last follow-up or death from any cause. Disease-free survival (DFS) was determined as the period between the date of surgery and the relapse diagnosis obtained by tests. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the interval in months measured between the date of resection and death for any cause.

Tissue Microarray (TMA) Construction

For TMA construction, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded samples containing primary tumors and paired normal mucosa were retrieved from the archives of the Department of Pathology of our hospital. Representative areas of tissue were established by microscopic review of H&E stained slides, and 1.0 mm diameter cores were punched from the paraffin blocks. Three cores from primary cancer and one core from normal tissues (at least 2 cm distal to the tumor) were arrayed. TMAs were created using a Tissue Microarrayer (ALPHELYS, Minicore Tissue Arrayer Central Unit, France). All specimens were examined by at least two pathologists to prevent bias. Tumor and normal mucosa morphology on the arrays were validated as having high accordance with that of the whole archived section.

Immunohistochemistry Staining

TGF-β, HIF-1α, VEGF and pERK1/2 expression were detected on the TMAs following citrate buffer (pH 6.0) antigen retrieval using standard methodology. Samples were incubated with primary antibody against TGF-β (Rabbit polyclonal Antibody, 1∶150, Abcam), HIF-1α (Rabbit Monoclonal Antibody, 1∶600, Epitomics), VEGF (Rabbit polyclonal, 1∶150, Abcam) or pERK1/2 (Rabbit Monoclonal Antibody, 1∶200, Cell Signaling), and then incubated with the second antibody (Dako REALTM EnVison TM Detection Syetem, Denmark). Tissue sections were counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin. The positive controls were samples from our pathology specimen bank, while negative controls were experimental samples incubated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) instead of primary antibody.

Immunohistochemical assessment

Immunohistochemical staining was evaluated independently by two pathologists without the knowledge of patient outcomes (double-blinded) according to the staining area and intensity [8]–[10]; the interobserver concordance was > 90%. In order to obtain accurate views of the tumors, three cores of representative regions were collected from primary cancer for tissue microarray. Pathologists comprehensively evaluated immunohistochemical staining of three cores, then provided a final score reflecting both the percentage of positive cells and the intensity of signal in positive cells (H-score range 0–12). Immunohistochemical score was applied as shown in Table 2, with the median H-score used as the cutoff. According to the H-scores of TGF-β, HIF-1α, VEGF and pERK1/2, each patient was assigned to either the overexpression group or the weak-expression group.

Table 2. Two procedures for evaluation of HER-2 expression.

| IRS (Immunoreactive Score) modified by pathologists * | |||

| Intensity of reaction | Points | Percentage of positive cells | Points |

| No reaction | 0 | No positive cells | 0 |

| Weak colour reaction | 1 | <25% positive cells | 1 |

| Moderate intensity | 2 | 25–50% positive cells | 2 |

| Intense reaction | 3 | 51–75% positive cells | 3 |

| >75% positive cells | 4 | ||

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis, Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS), version 19.0 was used. Correlations between the expressions of TGF-β, HIF-1α, VEGF and pERK1/2 were explored using Spearman's rank test, Correlations between clinicopathological factors and expression of TGF-β, HIF-1α, VEGF and pERK1/2 were examined using Pearson's Chi-Square test or Fisher's Exact test. The survival rate was calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and univariate survival analysis was performed using log-rank test. Multivariable analysis of prognostic factors was conducted by Cox proportional hazards model; P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

TGF-β, HIF-1α, VEGF and pERK 1/2 expressions in gastric cancer patients

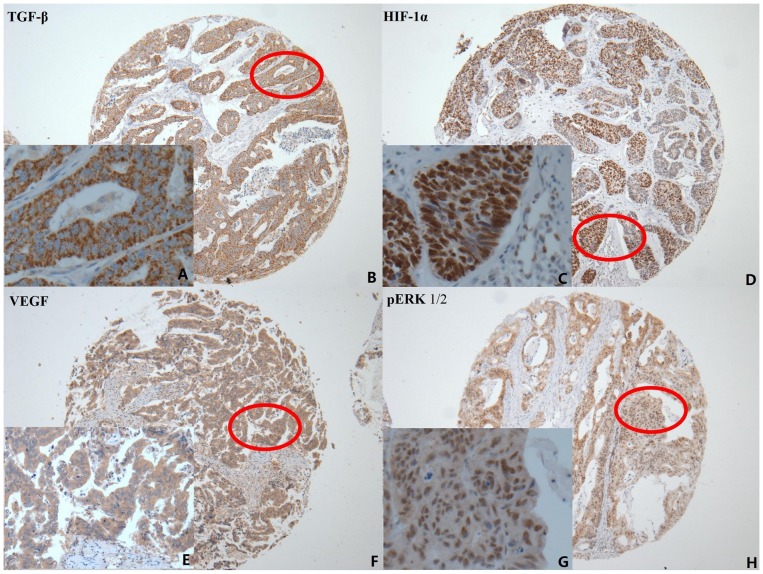

TGF-β ( Fig. 1A and 1B ) and VEGF ( Fig. 1E and 1F ) was dispersed granularly within the cytoplasm of tumor cells, expressed at varying levels (indicated by level intensity of color development). HIF-1α was expressed in tumor cell nuclei ( Fig. 1C and 1D ). pERK1/2 was observed both in tumor cell cytoplasm and nuclei (Fig. 1G and 1H). Among the total of 446 gastric cancer specimens, TGF-β overexpression was detected in 181 (40.6%), HIF-1α overexpression in 217 (48.7%), VEGF overexpression in 194 (43.5%), and pERK overexpression in 149 (34.3%).

Figure 1. Immunohistochemical staining of TGF-β, HIF-1α, VEGF and pERK 1/2 expression in gastric cancer.

A. Immunohistochemical staining of TGF-β was located mainly in the cytoplasm of tumor cells (positive expression ×400); B. TGF-β original magnification ×100; C. HIF-1α was located mainly in the nucleus of tumor cells (positive expression ×400); D. HIF-1α original magnification ×100; E. VEGF was located mainly in the cytoplasm of tumor cells (positive expression ×400); F. VEGF original magnification×100; G. pERK1/2 was located in the cytoplasm and nucleus of tumor cells (positive expression ×400); H. pERK1/2 original magnification ×100.

Using Spearman's rank test, correlations between the expressions of TGF-β, HIF-1α, VEGF and pERK1/2 were explored. There is significant correlation between the overexpression of any two of these four proteins (P<0.05).

Correlations between TGF-β, HIF-1α, VEGF and pERK1/2 expressions and clinicopathological factors

Correlations between clinicopathological factors and expression of TGF-β, HIF-1α, VEGF and pERK1/2 were observed using Pearson's Chi-Square test or Fisher's Exact test. The detailed characteristics are shown in Table 3 and Table 4. TGF-β overexpression was more frequent in patients with peritoneum cavity metastasis (50.8% versus 36.4% in those without peritoneum cavity metastasis, P = 0.005, χ2 = 7.895). HIF-1α overexpression was more frequent in patients with hepatic metastases (71.6% versus 43.0% in those without hepatic metastases, P = 0.000, χ2 = 23.086) and was more frequent in patients with peritoneum cavity metastasis (62.3% versus 43.0% in those without peritoneum cavity metastasis, P = 0.000, χ2 = 13.691).

Table 3. TGF-β and HIF-1α expressions and Clinicopathologic characteristics.

| Characteristics | TGF-β | HIF-1α | ||||

| Low | High | P a | Low | High | P a | |

| 265(59.4) | 181(40.6) | 229(51.3) | 217(48.7) | |||

| Age | ||||||

| <60 | 135(60.3) | 89(39.7) | 0.713 | 124(55.4) | 100(44.6) | 0.089 |

| ≥60 | 130(58.6) | 92(41.4) | 105(47.3) | 117(52.7) | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 204(58.6) | 144(41.4) | 0.519 | 176(50.6) | 172(49.4) | 0.540 |

| Female | 61(62.2) | 37(37.8) | 53(54.1) | 45(45.9) | ||

| Borrmann type | ||||||

| I | 40(63.5) | 23(36.5) | 0.183 | 28(44.0) | 35(55.6) | 0.435 |

| II+III | 207(58.5) | 147(41.5) | 186(52.5) | 168(47.5) | ||

| IV | 14(56.0) | 11(44.0) | 14(56.0) | 11(44.0) | ||

| V | 4 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1(25.0) | 3 (75.0) | ||

| Tumor Size | ||||||

| <5 cm | 125(64.8) | 68(35.2) | 0.044 | 98(50.8) | 95(49.2) | 0.834 |

| ≥5 cm | 140(55.3) | 113(44.7) | 131(51.8) | 122(48.2) | ||

| Tumor Histological Morphology | ||||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 175(61.0) | 112(39.0) | 0.644 | 156(54.4) | 131(45.6) | 0.230 |

| Absolute signet ring cell carcinoma | 41(57.7) | 30(42.3) | 33(46.5) | 38(53.5) | ||

| Mixed carcinoma | 49(55.7) | 39(44.3) | 40(45.5) | 48(54.5) | ||

| Lauren type | ||||||

| Intestinal | 125(61.0) | 80(39.0) | 0.366 | 107(52.2) | 98(47.8) | 0.854 |

| Diffuse | 115(56.4) | 89(43.6) | 102(50.0) | 102(50.0) | ||

| mixed type | 25(67.6) | 12(32.4) | 20(54.1) | 17(45.9) | ||

| Tumor differentiation | ||||||

| Poor | 209(59.0) | 145(41.0) | 0.750 | 183(51.7) | 171(48.3) | 0.772 |

| Moderate and High | 56(60.9) | 36(39.1) | 46(50.0) | 46(50.0) | ||

| Vessel invasion | ||||||

| Yes | 160(57.3) | 119(42.7) | 0.250 | 142(50.9) | 137(49.1) | 0.806 |

| No | 105(62.9) | 62(37.1) | 87(52.1) | 80(47.9) | ||

| Perineural invasion | ||||||

| Yes | 181(57.8) | 132(42.2) | 0.294 | 166(53.0) | 147(47.0) | 0.273 |

| No | 84(63.2) | 49(36.8) | 63(47.4) | 70(52.6) | ||

| T category | ||||||

| T1 | 12(70.6) | 5(29.4) | 0.630 | 8(47.1) | 9(52.9) | 0.112 |

| T2 | 18(56.3) | 14(43.8) | 15(46.9) | 17(53.1) | ||

| T3 | 36(54.5) | 30(45.5) | 43(65.2) | 23(34.8) | ||

| T4 | 199(60.1) | 132(39.9) | 163(49.2) | 168(50.8) | ||

| N category | ||||||

| N0 | 65(67.0) | 32(33.0) | 0.069 | 53(54.6) | 44(45.4) | 0.147 |

| N1 | 47(50.0) | 47(50.0) | 46(48.9) | 48(51.1) | ||

| N2 | 61(56.0) | 48(44.0) | 47(43.1) | 62(56.9) | ||

| N3 | 92(63.0) | 54(37.0) | 83(56.8) | 63(43.2) | ||

| TNM stage | ||||||

| IA+IB | 20(74.1) | 7(25.9) | 0.005 | 15(55.6) | 12(44.4) | 0.775 |

| IIA | 15(68.2) | 7(31.8) | 13(59.1) | 9(40.9) | ||

| IIB | 50(60.2) | 33(39.8) | 43(51.8) | 40(48.2) | ||

| IIIA | 35(42.2) | 48(57.8) | 37(44.6) | 46(55.4) | ||

| IIIB | 61(57.5) | 45(42.5) | 54(50.9) | 52(49.1) | ||

| IIIC | 84(67.2) | 41(32.8) | 67(53.6) | 58(46.4) | ||

| Hepatic metastases | ||||||

| No | 219(61.2) | 139(38.8) | 0.128 | 204(57.0) | 154(43.0) | 0.000 |

| Yes | 46(52.3) | 42(47.7) | 25(28.4) | 63(71.6) | ||

| Peritoneum cavity metastasis | ||||||

| No | 201(63.6) | 115(36.4) | 0.005 | 180(57.0) | 136(43.0) | 0.000 |

| Yes | 64(49.2) | 66(50.8) | 49(37.7) | 81(62.3) | ||

Pearson's Chi-Square test or Fisher's Exact test, P<0.05.

Table 4. VEGF and pERK expressions and Clinicopathologic characteristics.

| Characteristics | VEGF | pERK | ||||

| Low | High | P a | Low | High | P a | |

| 252(56.5) | 194(43.5) | 297(65.7) | 149(34.3) | |||

| Age | ||||||

| <60 | 120(53.6) | 104(46.4) | 0.210 | 147(65.6) | 77(34.4) | 0.664 |

| ≥60 | 132(59.5) | 90(40.5) | 150(67.6) | 72(32.4) | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 192(55.2) | 156(44.8) | 0.286 | 236(67.8) | 112(32.2) | 0.302 |

| Female | 60(61.2) | 38(38.8) | 61(62.2) | 37(37.8) | ||

| Borrmann type | ||||||

| I | 39(61.9) | 24(38.1) | 0.642 | 36(57.1) | 27(42.9) | 0.090 |

| II+III | 195(55.1) | 159(44.9) | 238(67.2) | 116(32.8) | ||

| IV | 16(64.0) | 9(36.0) | 21(84.0) | 4(16.0) | ||

| V | 2 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) | 2(50.0) | 2 (50.0) | ||

| Tumor Size | ||||||

| <5 cm | 113(58.5) | 80(41.5) | 0.446 | 135(69.9) | 58(30.1) | 0.189 |

| ≥5 cm | 139(54.9) | 114(45.1) | 162(64.0) | 91(36.0) | ||

| Tumor Histological Morphology | ||||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 153(53.3) | 134(46.7) | 0.001 | 191(66.6) | 96(33.4) | 0.903 |

| Absolute signet ring cell carcinoma | 54(76.1) | 17(23.9) | 46(64.8) | 25(35.2) | ||

| Mixed carcinoma | 45(51.1) | 43(48.9) | 60(68.2) | 28(31.8) | ||

| Lauren type | ||||||

| Intestinal | 109(53.2) | 96(46.8) | 0.400 | 134(65.4) | 71(34.6) | 0.822 |

| Diffuse | 122(59.8) | 82(40.2) | 137(67.2) | 67(32.8) | ||

| mixed type | 21(56.8) | 16(43.2) | 26(70.3) | 11(29.7) | ||

| Tumor differentiation | ||||||

| Poor | 202(57.1) | 152(42.9) | 0.640 | 238(67.2) | 116(32.8) | 0.574 |

| Moderate and High | 50(54.3) | 42(45.7) | 59(64.1) | 33(35.9) | ||

| Vessel invasion | ||||||

| Yes | 167(59.9) | 112(40.1) | 0.065 | 187(67.0 | 92(33.0) | 0.802 |

| No | 85(50.9) | 82(49.1) | 110(65.9) | 57(34.1) | ||

| Perineural invasion | ||||||

| Yes | 184(58.8) | 129(41.2) | 0.136 | 208(66.5) | 105(33.5) | 0.924 |

| No | 68(51.1) | 65(48.9) | 89(66.9) | 44(33.1) | ||

| T category | ||||||

| T1 | 12(70.6) | 5(29.4) | 0.471 | 10(58.2) | 7(41.2) | 0.293 |

| T2 | 20(62.5) | 12(37.5) | 17(53.1) | 15(46.9) | ||

| T3 | 34(51.5) | 32(48.5) | 43(65.2) | 23(34.8) | ||

| T4 | 186(56.2) | 145(42.8) | 227(68.6) | 104(31.4) | ||

| N category | ||||||

| N0 | 64(66.0) | 33(34.0) | 0.091 | 66(68.0) | 31(32.0) | 0.619 |

| N1 | 51(54.3) | 43(45.7) | 61(64.9) | 33(35.1) | ||

| N2 | 64(58.7) | 45(41.3) | 68(62.4) | 41(37.6) | ||

| N3 | 73(50.0) | 73(50.0) | 102(69.9) | 44(30.1) | ||

| TNM stage | ||||||

| IA+IB | 20(74.1) | 7(25.9) | 0.240 | 14(50.0) | 13(50.0) | 0.540 |

| IIA | 13(59.1) | 9(40.9) | 14(50.0) | 8(50.0) | ||

| IIB | 50(60.2) | 33(39.8) | 56(67.8) | 27(32.2) | ||

| IIIA | 50(60.2) | 33(39.8) | 59(69.4) | 24(30.6) | ||

| IIIB | 55(51.9) | 51(48.1) | 68(65.3) | 38(34.7) | ||

| IIIC | 64(41.2) | 61(48.8) | 86(67.2) | 39(32.8) | ||

| Hepatic metastases | ||||||

| No | 206(57.5) | 152(42.5) | 0.372 | 240(67.0) | 118(33.0) | 0.686 |

| Yes | 46(52.3) | 42(47.7) | 57(64.8) | 31(35.2) | ||

| Peritoneum cavity metastasis | ||||||

| No | 174(55.1) | 142(44.9) | 0.339 | 218(69.0) | 98(31.0) | 0.094 |

| Yes | 78(60.0) | 58(40.0) | 79(60.8) | 51(39.2) | ||

Pearson's Chi-Square test or Fisher's Exact test, P<0.05.

Univariate analysis

Using the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test, correlations between clinicopathological factors and patient outcomes were evaluated. Of the 446 patients, 295 (66.1%) developed recurrence and/or metastasis, and 263 (59.0%) died prior to the follow-up end date (August 1, 2011). Median DFS was 28.1 months and median OS was 40.2 months. The 3-year and 5-year overall survival rates were 52% and 39%, respectively.

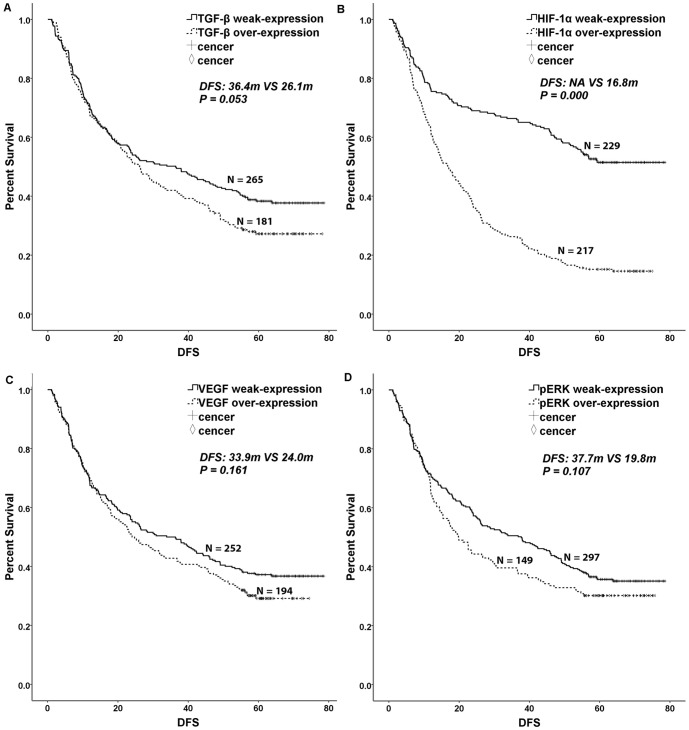

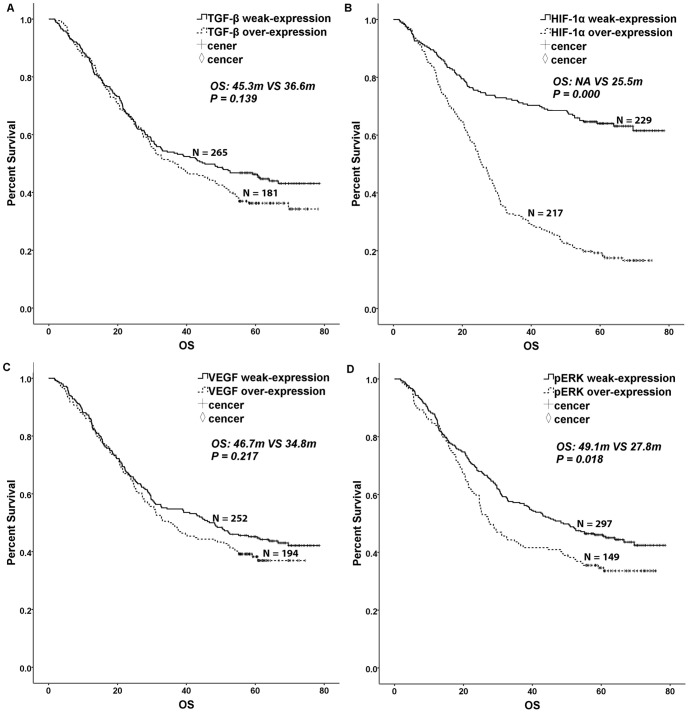

The widely accepted prognostic factors of borrmann type, tumor size, tumor histology, lauren type, tumor differentiation, vessel invasion, perineural invasion, T category, N category, TNM stage and adjuvant chemotherapy were associated with DFS and OS in gastric cancer after gastrectomy. Hepatic metastases and peritoneum cavity metastasis were associated with OS in gastric cancer after gastrectomy. Patients displaying weak TGF-β expression had a longer DFS than those displaying overexpression of TGF-β, with a P value close to 0.05. However, no difference in OS was observed (DFS: 36.4 m VS. 26.1 m, P = 0.053, χ2 = 3.759, Tab 1, Fig. 2A; OS: 45.3 m VS. 36.6 m, P = 0.139, χ2 = 2.187, Tab 1, Fig. 3A). Patients with HIF-1α weak-expression had a longer survival time than those with HIF-1α over-expression (DFS: NA VS. 16.8 m, P = 0.000, χ2 = 74.937, Tab 1, Fig. 2B; OS: NA VS. 25.5 m, P = 0.000, χ2 = 90.594, Tab 1, Fig. 3B). Patients with pERK weak-expression had a longer OS than patients with over-expression of pERK (DFS: 37.7 m VS. 19.8 m, P = 0.107, χ2 = 2.595, Tab 1, Fig. 2D; OS: 49.1 m VS. 27.8 m, P = 0.018, χ2 = 5.594, Tab 1, Fig. 3D). However, VEGF expression was not correlated with DFS and OS (P>0.1, Tab 1, Fig. 2C, Fig. 3C).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier curves for disease-free survival.

TGF-β, HIF-1α, VEGF and pERK 1/2 overexpression were divided into an overexpression group and a weak-expression group. A log-rank test was used to calculate significance. A. Disease-free survival curves stratified by TGF-β expression (P = 0.053). B. Disease-free survival curves stratified by HIF-1α expression (P = 0.000). C. Disease-free survival curves stratified by VEGF expression (P = 0.161). D. Disease-free survival curves stratified by pERK 1/2 expression (P = 0.107).

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier curves for overall survival.

TGF-β, HIF-1α, VEGF and pERK 1/2 overexpression were divided into an overexpression group and a weak-expression group. A log-rank test was used to calculate significance. A. Overall survival curves stratified by TGF-β expression (P = 0.139). B. Overall survival curves stratified by HIF-1α expression (P = 0.000). C. Overall survival curves stratified by VEGF expression (P = 0.217). D. Overall survival curves stratified by pERK 1/2 expression (P = 0.018).

Multivariate analysis

Parameters with P-values of ≤0.1 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis using the Cox proportional hazards. The results are summarized in Table 5. Results from the Cox proportional hazards model using the backward stepwise method indicated that HIF-1α overexpression was an independent prognostic factor in predicting DFS and OS. Patients with HIF-1α overexpression had a shorter survival and higher risk of recurrence and death than patients with HIF-1α weak-expression (DFS: HR 2.766, 95%CI 2.136–2.583, P = 0.000; OS: HR 3.529, 95%CI 2.663–4.667, P = 0.000, Table 5).

Table 5. Multivariate analysis of significant prognostic factors for survival in patients with gastric carcinoma.

| Variables | DFS | OS | ||||

| P * | HR | 95%CI | P * | HR | 95%CI | |

| Age(<60years, ≥60years) | 0.968 | 1.005 | 0.787–1.283 | 0.676 | 1.058 | 0.813–1.376 |

| Borrmann type(I, II+III, IV, V) | 0.000 | 1.671 | 1.306–2.138 | 0.000 | 1.950 | 1.475–2.578 |

| Tumor Size(<5 cm, ≥5 cm) | 0.311 | 1.138 | 0.886–1.463 | 0.706 | 1.052 | 0.808–1.369 |

| Histological Morphology(A, S, M)1 | 0.481 | 1.036 | 0.939–1.143 | 0.505 | 1.305 | 0.935–1.146 |

| Lauren type(I, D, M)2 | 0.259 | 1.109 | 0.927–1.327 | 0.226 | 1.124 | 0.930–1.360 |

| Tumor differentiation(P/D, M/D+H/D)3 | 0.894 | 0.978 | 0.702–1.362 | 0.437 | 0.866 | 0.602–1.245 |

| Vessel invasion(YES, NO) | 0.239 | 1.157 | 0.908–1.475 | 0.152 | 1.201 | 0.935–1.544 |

| Perineural invasion(YES, NO) | 0.661 | 1.060 | 0.816–1.377 | 0.871 | 1.016 | 0.836–1.235 |

| T category(T1, T2, T3, T4) | 0.444 | 1.103 | 0.858–1.420 | 0.723 | 1.051 | 0.798–1.384 |

| N category(N0, N1, N2, N3) | 0.219 | 1.382 | 0.825–2.313 | 0.314 | 1.336 | 0.760–2.347 |

| TNM stage(I, II, IIIA, IIIB, IIIC) | 0.000 | 2.008 | 1.781–2.265 | 0.000 | 1.654 | 1.522–1.798 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy(YES, NO) | 0.000 | 0.346 | 0.268–0.447 | 0.000 | 0.330 | 0.252–0.432 |

| TGF-β expression(W, O)4 | 0.143 | 1.191 | 0.943–1.506 | 0.319 | 1.136 | 0.884–1.460 |

| HIF-1α expression(W, O)4 | 0.000 | 2.766 | 2.136–2.583 | 0.000 | 3.529 | 2.663–4.667 |

| pERK1/2 expression(W, O)4 | 0.084 | 1.249 | 0.971–1.606 | 0.009 | 1.420 | 1.092–1.845 |

DFS, Disease-free survival; OS, Overall Survival; HR, hazard ratio; CI, Confidence interval; *P<0.05; 1, A, Adenocarcinoma, S, Absolute signet ring cell carcinoma, M, Mixed carcinoma; 2, I, Intestinal, D, Diffuse, M, Mixed type; 3, P/D, Poor differentiation, M/D, Moderate differentiation, H/D High differentiation; 4, W, Weak-expression, O, Overexpression.

Discussion

Metastasis remains a major cause of treatment failure for patients with cancer, and angiogenesis is for metastasis to occur. In 1970s, Folkman found that tumor growth and metastasis are dependent on angiogenesis when the tumor size exceeds 2–3 mm [7]. Factors that can be used to predict the metastatic potential of cancer have been actively sought for several decades. The most significant finding from the current study is that TGF-β, HIF-1α, VEGF and pERK, all proangiogenic and angiogenic factors found within solid tumors and up regulated in malignancy, are linked to poor prognosis with disease progression [11]–[12], [4].

Hypoxia is one of the most important environmental factors that induce cancer metastasis [13]–[17]. Each step of the metastatic process, from the initial epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) to the ultimate organotropic colonization, can potentially be regulated by hypoxia, suggesting a master regulator role for hypoxia and HIFs in metastasis. Furthermore, modulation of cancer stem cell self-renewal by HIFs may also contribute to the hypoxia-regulated metastasis program [15]. HIF-1α regulates both transcription factors and chromatin modifiers to induce metastasis in an EMT-dependent or -independent manner. In addition, various targets regulated by HIF-1α that mediate other biological effects such as metabolism might also contribute to metastasis [16]. HIF-1α expression is correlated with poor prognostic clinicopathologic characteristics and survival in different cancers [18]. In an analysis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma, Wei et al found that hypoxia significantly promotes cell proliferation and migration, resulting in metastasis both in vitro and in vivo [17]. Wang et al examined the possible role for HIF-1α and HIF-2α in the process of invasiveness and metastasis of gastric cancer during hypoxia, with involvement of the JNK signal pathway. Their results showed that HIF-1α and HIF-2α were more highly expressed in metastatic gastric cancers compared to non-metastatic carcinomas [19], indicating that HIF-1α is likely a major determinant of invasion and metastasis in several tumor types.

In fact, the targeted inhibition of HIF-1α has been shown to inhibit the growth of gastric tumors in animals [20], [21]. Furthermore, the prognostic role of HIF-1α in gastric tumor had been searched in many trials. However, though researched for years, the prognostic role of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF-1α) in gastric cancer is still controversial. In a meta-analysis performed by Zhang et al. [22], involving 12 trials (1,555 patients), it was reported that HIF-1α expression was significantly correlated with poor overall survival of gastric cancer patients (HR = 1.34, 95%CI: 1.13–1.58; P = 0.0009), but not with poor disease free survival of gastric cancer patients (HR = 1.67, 95%CI: 0.99–2.82; P = 0.06). This is also the point where the novelty of our current manuscript becomes apparent. Of the 12 studies that formed the basis of the aforementioned meta-analysis, the largest sample size was 216 [22]. The sample size in our study was 446 patients. Hence, the current study is the single largest sample size in which correlation of HIF-1α and prognosis of gastric cancer was evaluated. Our univariate analysis revealed that patients with HIF-1α overexpression had both a shorter disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) than patients with weak-expression. Importantly, HIF-1α overexpression was also a promising prognostic marker for poor survival by multivariate. This is in stark contrast to the conclusion of the aforementioned meta-analysis [22], where it was not related to DFS. Hence, our study shows for the first time that HIF-1α overexpression is correlated to not only OS, but also DFS, in gastric cancer patients. Through rational extrapolation such a finding will come into the equation when novel therapeutics targeting HIF-1α, will be evaluated.

In the present study, increased overexpression of HIF-1α was observed in GC patients with peritoneum cavity metastasis. These results are consistent with previous basic research studies. Using in vivo metastatic models, Miyake et al provided a possible mechanism in which peritoneal dissemination of gastric cancer develops via a vascular network, whereby HIF-1α activates tumor angiogenesis [23]. Matsuo et al showed that HIF-1α expression was significantly associated with the high incidence of hepatic metastasis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [24]. Shimomura et al analyzed patients who underwent curative resection and found that overexpression of HIF-1α was an independent risk factor in colorectal liver metastasis [25]. In work presented here, increased overexpression of HIF-1α was observed in GC patients with hepatic metastases, a result consistent with the above studies showing a close link between HIF-1α and liver metastasis.

Many studies indicate that TGF-β signaling can act as either a tumor promoter or a tumor suppressor. Some investigators have explored the role of TGF-β1 in lung cancer, finding in patients that TGF-β predicted poor distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) and poor brain metastasis after adjustment for other factors. They also found in culture that transfection with TGF-β stimulated migration and invasion of lung cancer cells, suggesting that TGF-β may be involved in increased metastatic potential [26], [27], [14]. In addition, cancer cells over-expressing active TGF-β increased metastatic ability, and targeting of TGF-signaling prevented metastasis in several cancers such as breast and prostate [28]–[30]. Others have suggested that TGF-β protein levels might independently predict survival in patients with lung adenocarcinoma [27], [31]. In those studies, TGF-β expression in primary lung cancer tissues was higher among patients with pulmonary metastases than in patients without such metastases. Additional work has investigated differences in TGF-β levels and their association with colorectal cancer (CRC) progression, finding that TGF-β levels in this context are a robust predictor of disease relapse [32], [33]. In gastric cancer, Comerci et al found that secreted TGF-β1 might indirectly promote tumor progression [34]. Ottaviano et al showed that TGF-β1-mediated crosstalk between gastric cancer cells and stromal elements influenced cell surface- and pericellular matrix-degrading potential in vitro [35]. Fu et al reported that TGF- significantly promoted the invasion and metastasis of the gastric cancer cell lines SGC7901 and BGC823 by increasing fascin1 expression via the ERK and JNK signaling pathways [36]. Additionally, Ma et al concluded that the secretion of TGF-β by both tumor and stromal cells might play important roles in development and maintenance of the tumor microenvironment [37]. Researchers have also examined human tissues with early gastric cancer (EGC) and advanced gastric cancer (AGC). Positive staining for the intracellular form of TGF-β was found in 59.1% of EGC, and 66.7% of AGC samples. In contrast, there was no difference in the expression of TGF-β in relation to Helicobacter pylori (Hp) infection, Lauren's classification or lymph node involvement. Moreover, clinical studies showed the positive correlation of TGF-β expression with lymph node metastasis and poor prognosis in gastric carcinoma [38], [39]. Similar to these results we have found in the current study that TGF-β overexpression was more frequent in patients with peritoneum cavity metastasis than in patients without such metastasis. Patients with TGF-β overexpression had a shorter disease-free survival time than those with TGF-β weak-expression in the univariate analysis, while it was excluded from the multivariate analysis. Therefore, our findings indicate that TGF-β might facilitate cancer metastasis but does not constitute an independent factor.

It should be noted that one limitation of this study is that the data used was limited and retrospective. Further research will be important to better understand the relationship between the above markers and survival.

Conclusions

Our work here suggests that overexpression of HIF-1α could be an important indicator of poor prognosis in gastric cancer after gastrectomy. Although further work will be needed to validate these conclusions in a clinical setting, HIF-1α overexpression correlated well with hepatic metastases and peritoneum cavity metastasis in patients with GC. In addition, further research into the relationship between antiangiogenic therapy and metastasis of gastric cancer may provide additional potential drug targets, resulting in therapies that can enhance the clinical benefits of antiangiogenic treatment.

Funding Statement

We are grateful to all the subjects who participated in this study. This study was supported by the Doctor Fund of People's Liberation Army General Hospital (10BCZ04). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, et al. (2011) Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 61(2): 69–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kamangar F, Dores GM, Anderson WF (2006) Patterns of cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence across five continents: defining priorities to reduce cancer disparities in different geographic regions of the world. J Clin Oncol 24(14): 2137–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lin EY, Li JF, Bricard G, Wang W, Deng Y, et al. (2007) VEGF Restores Delayed Tumor Progression in Tumors Depleted of Macrophages. Mol Oncol 1(3): 288–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yang SY, Yu H, Krygier JE, Wooley PH, Mott MP (2007) High VEGF with rapid growth and early metastasis in a mouse osteosarcoma model. Sarcoma 2007: 95628 10.1155/2007/95628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brown NS, Bicknell R (2001) Hypoxia and oxidative stress in breast cancer: Oxidative stress: its effects on the growth, metastatic potential and response to therapy of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 5: 323–327 10.1186/bcr315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gu JW, Makey KL, Tucker KB, Chinchar E, Mao X, et al. (2013) EGCG, a major green tea catechin suppresses breast tumor angiogenesis and growth via inhibiting the activation of HIF-1α and NFκB, and VEGF expression. Vasc Cell 5(1): 9 10.1186/2045-824X-5-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Folkman J (1974) Proceedings: Tumor angiogenesis factor. Cancer Res 34(8): 2109–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Remmele W, Stegner HE (1987) Recommendation for uniform definition of an immunoreactive score (IRS) for immunohistochemical estrogen receptor detection (ER-ICA) in breast cancer tissue. Pathologe 8(3): 138–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen J, Tang H, Wu Z, Zhou C, Jiang T, et al. (2013) Overexpression of RBBP6, Alone or Combined with Mutant TP53, Is Predictive of Poor Prognosis in Colon Cancer. PLoS One 8(6): e66524 10.1371/journal.pone.0066524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Halon A, Donizy P, Biecek P, Rudno-Rudzinska J, Kielan W, et al. (2012) HER-2 expression in immunohistochemistry has no prognostic significance in gastric cancer patients. ScientificWorldJournal 2012: 941259 10.1100/2012/941259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nam SY, Ko YS, Jung J, Yoon J, Kim YH, et al. (2011) A hypoxia-dependent upregulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 by nuclear factor-κB promotes gastric tumourgrowth and angiogenesis. Br J Cancer 104(1): 166–74 10.1038/sj.bjc.6606020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Folkman J (2002) Role of angiogenesis in tumor growth and metastasis. Semin Oncol 29(6 Suppl 16)15–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tsai YP, Wu KJ (2012) Hypoxia-regulated target genes implicated in tumor metastasis. J Biomed Sci 19: 102 10.1186/1423-0127-19-102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Semenza GL (2012) Hypoxia-inducible factors: mediators of cancer progression and targets for cancer therapy. Trends Pharmacol Sci 33(4): 207–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lu X, Kang Y (2010) Hypoxia and hypoxia-inducible factors: master regulators of metastasis. Clin Cancer Res 16(24): 5928–35 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Majmundar AJ, Wong WJ, Simon MC (2010) Hypoxia-inducible factors and the response to hypoxic stress. Mol Cell 40: 294–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wei H, Li F, Fu P, Liu X (2013) Effects of the silencing of hypoxia-inducible Factor-1 alpha on metastasis of pancreatic cancer. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 17 (4): 436–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang Q, Chen Y, Zhang B, Shi B, Weng W, et al. (2013) Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α polymorphisms and risk of cancer metastasis: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 28 8(8): e70961 10.1371/journal.pone.0070961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang Y, Li Z, Zhang H, Jin H, Sun L, et al. (2010) HIF-1α and HIF-2α correlate with migration and invasion in gastric cancer. Cancer Biol Ther 10(4): 376–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yeo EJ, Chun YS, Cho YS, Kim J, Lee JC, et al. (2003) a potential anticancer drug targeting hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J Natl Cancer Inst 95: 516–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stoeltzing O, McCarty MF, Wey JS, Fan F, Liu W, et al. (2004) Role of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha in gastric cancer cell growth, angiogenesis, and vessel maturation. J Natl Cancer Inst 96: 946–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhang ZG, Zhang QN, Wang XH, Tian JH (2013) Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF-1α) as a prognostic indicator in patients with gastric tumors: a meta-analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 14 (7): 4195–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Miyake S, Kitajima Y, Nakamura J, Kai K, Yanagihara K, et al. (2013) HIF-1α is a crucial factor in the development of peritoneal dissemination via natural metastatic routes in scirrhous gastric cancer. Int J Oncol 43(5): 1431–40 10.3892/ijo.2013.2068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Matsuo Y, Ding Q, Desaki R, Maemura K, Mataki Y, et al. (2013) Hypoxia inducible factor-1 alpha plays a pivotal role in hepatic metastasis of pancreatic cancer: an immunohistochemical study. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 21(2): 105–12 10.1002/jhbp.6.Epubaheadofprint [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shimomura M, Hinoi T, Kuroda S, Adachi T, Kawaguchi Y, et al. (2013) Overexpression of Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1 Alpha is an Independent Risk Factor for Recurrence After Curative Resection of Colorectal Liver Metastases. Ann Surg Oncol 3: S527–36. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26. Yuan X, Wei Q, Komaki R, Liu Z, Yang J, et al. (2013) TGFβ1 Polymorphisms Predict Distant Metastasis-Free Survival in Patients with Inoperable Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer after Definitive Radiotherapy. PLoS One 8(6): e65659 10.1371/journal.pone.0065659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Saji H, Nakamura H, Awut I, Kawasaki N, Hagiwara M, et al. (2003) Significance of expression of TGF-beta in pulmonary metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer tissues. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 9(5): 295–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ivanovic V, Melman A, Davis-Joseph B, Valcic M, Geliebter J (1995) Elevated plasma levels of TGF-beta1 in patients with invasive prostate cancer. Nat Med 1: 282–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bandyopadhyay A, Agyin JK, Wang L, Tang Y, Lei X, et al. (2006) Inhibition of pulmonary and skeletal metastasis by a transforming growth factor-beta type I receptor kinase inhibitor. Cancer Res 66: 6714–6721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ehata S, Hanyu A, Fujime M, Katsuno Y, Fukunaga E, et al. (2007) Ki26894, a novel transforming growth factor-beta type I receptor kinase inhibitor, inhibits in vitro invasion and in vivo bone metastasis of a human breast cancer cell line. Cancer Sci 98: 127–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Domagała-Kulawik J, Hoser G, Safianowska A, Grubek-Jaworska H, Chazan R (2006) Elevated TGF-beta1 concentration in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients with primary lung cancer. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 54(2): 143–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Calon A, Espinet E, Palomo-Ponce S, Tauriello DV, Iglesias M, et al. (2012) Dependency of colorectal cancer on a TGF-β-driven program in stromal cells for metastasis initiation. Cancer Cell 22(5): 571–84 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.08.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Markowitz SD, Bertagnolli MM (2009) Molecular origins of cancer: Molecular basis of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 361(25): 2449–60 10.1056/NEJMra0804588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Comerci JT Jr, Runowicz CD, Flanders KC, De Victoria C, Fields AL, et al. (1996) Altered expression of transforming growth factor-beta 1 in cervical neoplasia as an early biomarker in carcinogenesis of the uterine cervix. Cancer 77(6): 1107–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ottaviano AJ, Sun L, Ananthanarayanan V, Munshi HG (2006) Extracellular matrix-mediated membrane-type 1 matrix metalloproteinase expression in pancreatic ductal cells is regulated by transforming growth factor-beta1. Cancer Res 66(14): 7032–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fu H, Hu Z, Wen J, Wang K, Liu Y (2009) TGF-beta promotes invasion and metastasis of gastric cancer cells by increasing fascin1 expression via ERK and JNK signal pathways. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 41(8): 648–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ma GF, Miao Q, Zeng XQ, Luo TC, Ma LL, et al. (2013) Transforming growth factor-β1 and -β2 in gastric precancer and cancer and roles in tumor-cell interactions with peripheral blood mononuclear cells in vitro. PLoS One 8(1): e54249 10.1371/journal.pone.0054249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Maehara Y, Kakeji Y, Kabashima A, Emi Y, Watanabe A, et al. (1999) Role of transforming growth factor-beta 1 in invasion and metastasis in gastric carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 17(2): 607–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Saito H, Tsujitani S, Oka S, Kondo A, Ikeguchi M, et al. (2000) An elevated serum level of transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-beta 1) significantly correlated with lymph node metastasis and poor prognosis in patients with gastric carcinoma. Anticancer Res 20(6B): 4489–4493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]