Abstract

The largest genus in the conifer family Pinaceae is Pinus, with over 100 species. The size and complexity of their genomes (∼20–40 Gb, 2n = 24) have delayed the arrival of a well-annotated reference sequence. In this study, we present the annotation of the first whole-genome shotgun assembly of loblolly pine (Pinus taeda L.), which comprises 20.1 Gb of sequence. The MAKER-P annotation pipeline combined evidence-based alignments and ab initio predictions to generate 50,172 gene models, of which 15,653 are classified as high confidence. Clustering these gene models with 13 other plant species resulted in 20,646 gene families, of which 1554 are predicted to be unique to conifers. Among the conifer gene families, 159 are composed exclusively of loblolly pine members. The gene models for loblolly pine have the highest median and mean intron lengths of 24 fully sequenced plant genomes. Conifer genomes are full of repetitive DNA, with the most significant contributions from long-terminal-repeat retrotransposons. In depth analysis of the tandem and interspersed repetitive content yielded a combined estimate of 82%.

Keywords: introns, gene family, repeats, retrotransposons, conifer

LOBLOLLY pine is a long-lived, diploid member (2n = 24) of the genus Pinus, one of >100 species worldwide. The natural range of this primarily outcrossing tree extends over a large portion of the southeastern United States. Loblolly pine is extensively cultivated in this region for timber and pulpwood, with plantations growing on >30 million hectares and producing ∼18% of the world’s industrial roundwood (Prestemon and Abt 2002). Loblolly pine’s preference for mild, wet climates has made it a model for ecological considerations relating to carbon sequestration in coastal plain plantations (Noormets et al. 2010). The plant biomass on these plantations is thought to contribute to a negative accumulation of atmospheric CO2 (Johnsen et al. 2001). This species is also under investigation as a potential source of sustainable, renewable energy, both as an independent source of terpenoids in liquid biofuels and as an intercropping species with other established sources, such as switchgrass (Briones et al. 2013; Westbrook et al. 2013). The economic and ecological importance of this species has led to several long-term breeding programs and large-scale studies that have addressed questions about the genetic diversity and adaptive capabilities (Brown et al. 2004; Eckert et al. 2010).

In the absence of an affordable and capable technology to generate and assemble a conifer genome, previous investigations have relied on other techniques to generate sequence for basic and applied research in pine genetics. For non-model organisms with large and complex genomes, transcriptome resources provide valuable sequence for gene discovery and annotation, as well as for comparative genomics. In loblolly pine, these were first generated with >300,000 Sanger-sequenced expressed sequence tags (ESTs) and later as de novo assemblies from next-generation sequencing technologies (Allona et al. 1998; Kirst et al. 2003; Cairney et al. 2006; Lorenz et al. 2006, 2012). Large-scale resequencing of the first ESTs and subsequent genotyping of single nucleotide polymorphisms in large populations expanded the available molecular marker resources and provided a basis for examining their association with traits of interest (Eckert et al. 2013). The markers genotyped in these breeding populations also improved the density of the genetic linkage map for loblolly pine (Eckert et al. 2009, 2010; Martínez-García et al. 2013). The first significant insight into the genome came from the analysis of 10 bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) sequences (Kovach et al. 2010).

Gymnosperms are represented by just four divisions: Pinophyta (conifers), Cycadophyta (cycads), Gnetophyta (gnetophytes), and Ginkgophyta (Ginkgo). Their genome sizes range considerably, but are generally large, between 12 and 32 Gbp. The pine family (Pinaceae) possesses tremendous genome size variation. Pines (Pinus) diverged from spruces (Picea), their closest relatives, 85 MYA and possess larger genomes on average, estimated between 22 and 32 Gbp (Guillet-Claude et al. 2004; Willyard et al. 2007). The size of these genomes has previously served as a barrier to whole-genome sequencing, but recent advances in sequencing technologies and informatics have made assembling these megagenomes tractable. Unlike many large and complex crop genomes, there is no evidence to support a whole-genome duplication event. The large genome size has primarily been attributed to an extensive contribution of interspersed repetitive content (Morse et al. 2009; Kovach et al. 2010; Wegrzyn et al. 2013). Assembly of the Norway spruce genome has shown that LTR retrotransposons in particular are frequently nested within the long introns of some gene families (Nystedt et al. 2013). In addition, there is evidence for gene duplication, pseudogenes, and paralogs, although the extent of these is not clear (Kovach et al. 2010; Pavy et al. 2012).

To provide a foundation to study the biology of conifers, we annotated the loblolly pine genome, the first and largest pine genome assembled to date. The whole-genome shotgun sequencing and assembly (Zimin et al. 2014) produced two reference sequences. Version 1.0, the direct output of the MaSuRCA assembler (Zimin et al. 2013), was based on paired-end reads from a haploid megagametophyte and the matching long insert linking read pairs from diploid needle tissue. Version 1.01, which applied scaffolding from independent genome and transcriptome assemblies, spans 20.1 Gbp of sequence and is distributed in just over 14.4 million scaffolds covering 23.2 Gbp with an N50 of 66.9 kb (based on a genome size of 22 Gbp). Our annotation of the loblolly pine genome provides insight into the organization of the genome, its size, content, and structure.

Materials and Methods

Sequence alignments

Aligning DNA, messenger RNA (mRNA), or protein sequence to the loblolly pine genome presents challenges, as the genome is too large for many common bioinformatic programs. In our approach, we sorted the genomic data by descending scaffold length and partitioned the scaffolds into 100 bins such that the genomic sequence for each bin contained roughly the same number of bases. This allowed us to parallelize the computations and examine how fragmentation of the genomic data affected our ability to align sequence data to the genome. We generated initial mappings to the genome using blat (Kent 2002) with each bin as a target and then used blat utility programs to merge data from the 100 bins into a single file and filter that data according to quality metrics. In-house scripts were used to parse the blat results and create input files for exonerate (Slater and Birney 2005), which generated the final, more refined alignments to the genome.

A set of 83,285 de novo-assembled loblolly pine transcripts (BioProject PRJNA174450) served as the primary transcriptome reference. These were derived from multiple assemblies of 1.3 billion RNA-Seq reads, selected for uniqueness and putative protein-coding quality, and represented samplings from mixed sources of vegetative and reproductive organs, seedlings, embryos, haploid megagametophytes, and needles under environmental stress (Supporting Information, File S1). The transcriptome reference in addition to 45,085 sequences generated from >300,000 reclustered loblolly pine ESTs (Eckert et al. 2013) were aligned to the genome. Sanger-sequenced transcripts from four other pines available from the TreeGenes database (Wegrzyn et al. 2012) provided additional alignments: Pinus banksiana (13,040 transcripts), Pinus contorta (13,570 transcripts), and Pinus pinaster (15,648 transcripts). Transcriptome assemblies generated via 454 pyrosequencing and assembled with Newbler (Roche GS De novo Assembler) for Pinus palustris (16,832 transcripts) and Pinus lambertiana (40,619 transcripts) (Lorenz et al. 2012) were also aligned. Sequence alignments were examined at four different cutoffs for the loblolly sequence sets and two cutoffs for the other conifer resources. Stringent thresholds of 98% identity/98% coverage served as the starting point for loblolly pine while other conifer species were given more permissive (95% identity/95% coverage) cutoffs. The thresholds were lowered for all sequence sets to 95% identity/50% coverage to further examine the effects of genome fragmentation.

To discover orthologous proteins and align them to the genome, we began with 653,613 proteins spanning 24 species from version 2.5 of the PLAZA data set (Van Bel et al. 2012). PLAZA provides a curated and comprehensive comparative genomics resource for the Viridiplantae, including annotated proteins. This set was further curated to exclude proteins that were not full length, those shorter than 21 amino acids, and those that had genomic coordinates that did not agree with the reported coding sequence (CDS) or did not translate into the reported protein. To this set, 25,347 angiosperm proteins reported by the Amborella Genome Project (http://www.amborella.org/) were added. From annotated full-length mRNAs available in GenBank, a set of 10,793 proteins from Picea sitchensis were included. From the Picea abies v1.0 genome project (Nystedt et al. 2013), 22,070 full-length proteins were included where the reported CDS agreed with the translated protein (File S2 and Table S1). From the loblolly pine transcriptome, all 83,285 transcripts were translated for alignment. For the PLAZA protein alignments, the target version 1.01 genome was hard-masked for repeats; for all other alignments, the v1.01 genome was not repeat-masked. We accepted an alignment when at least 70% of the query sequence was included in the alignment and the exonerate similarity score (ESS) ≥70.

Gene annotation

Annotations for the assembly were generated using the automated genome annotation pipeline MAKER-P, which aligns and filters EST and protein homology evidence, produces ab initio gene predictions, infers 5′ and 3′ UTRs, and integrates these data to produce final downstream gene models with quality control statistics (Campbell et al. 2014). Inputs for MAKER-P include the Pinus taeda genome assembly (v1.0), Pinus and Picea ESTs, conifer transcriptome assemblies, a species-specific repeat library (PIER) (Wegrzyn et al. 2013), protein databases containing annotated proteins for P. sitchensis and P. abies, and version 2.5 of the PLAZA protein database (Van Bel et al. 2012). MAKER-P produced ab initio gene predictions via SNAP (Korf 2004) and Augustus (Stanke and Waack 2003). A subset of annotations (500 Mb of sequence) were manually reviewed to develop appropriate filters for the final gene models. Given the large genome size and potential for spurious annotations, conservative thresholds for these filters were chosen. Filters included the initial removal of single-exon annotations because of apparent pseudogene bias, annotations not containing a recognizable protein domain as interpreted using InterProScan (Quevillon et al. 2005), or annotations that do not partially overlap the conifer transcriptome resources available. Among the selected, nonoverlapping gene models, a subset of high confidence gene models was further analyzed based on the annotation edit distance (AED) score of < 0.20 with canonical start sites and splice sites. All gene models identified in v1.0 were also mapped to the latest assembly (v1.01). Functional annotations of the gene models were generated through blastp alignments against the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nr and plant protein databases for significant (E-values < 1e-05) and weak (E-value < 0.001) hits.

Alignments of the high-confidence MAKER-P sequences against the genome allowed for identification of large introns. Introns of lengths >20, >50, and >100 kbp and with <25% gap regions were selected for further analysis. Clusters from the Markov cluster algorithm (MCL) analysis that represented gene families with P. taeda members and contained primary introns (first CDS) >20 kbp were aligned and manually reviewed. The intronic sequences were investigated for the presence of intron-mediated expression signals (IMEs). IMEs were predicted via sequence motifs using the methodology outlined in Parra et al. (2007).

Orthologous proteins

The analysis of orthologous genes included a subset of the species that were previously selected from PLAZA. A total of 10, including: Arabidopsis thaliana (27,403), Glycine max (46,324), Oryza sativa (41,363), Physcomitrella patens (28,090), Populus trichocarpa (40,141), Ricinus communis (31,009), Selaginella moellendorffii (18,384), Theobroma cacao (28,858), Vitis vinifera (26,238), and Zea mays (39,172) were used. Three external protein sequence sets were also included: Amborella trichopoda (25,347), P. abies (22,070), and P. sitchensis (10,521). The primary source of the P. taeda sequence was the complete set of 50,172 gene models generated from the MAKER-P pipeline. All 14 sequence sets (including the 10 from PLAZA) were clustered to 90% identity within species and combined to generate 399,358 sequences.

The MCL analysis (Enright et al. 2002), as implemented in the TRIBE-MCL pipeline (Dongen and Abreu-Goodger 2012), was used to cluster the 399,358 protein sequences from 14 species into orthologous groups. The methodology was selected due to its robust implementation that avoids merging clusters that share only a few edges. This leads to accurate identifications of gene families even in the presence of lower-quality BLAST hits or promiscuous domains (Frech and Chen 2010). The analysis was performed by running pairwise NCBI blastp v2.2.27+ (Altschul et al. 1990) (E-value cutoff of 1e-05) against the full set of proteins described above. In this pipeline, the negative log10 of the resulting blastp E-values produces a network graph that serves as input to define the orthologous groups. The user-supplied inflation value is used in the second stage to simulate random walks in the previously calculated graph. A large inflation value defines more clusters with lower amount of members (fine-grained granularity); a small inflation value defines not as many clusters, but the clusters have more members (coarse granularity). A moderate inflation value of 4.0 was selected to define the orthologous groups here. Following their generation, Pfam domains (Punta et al. 2012) were assigned from the PLAZA annotations of the individual sequences. InterProScan 4.8 (Hunter et al. 2012) was applied to those sequences obtained outside of PLAZA (A. trichopoda, P. sitchensis, P. abies, and P. taeda). PFam and Gene Ontology (GO) assignments with E-values < 1e-05 were retained. To effectively compare GO annotations, the terms were normalized to level four of the classification tree. When all predicted domains for a given family were classified as retroelements, the family was removed. After functional assessment and filtering, custom scripts and Venn diagrams (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/) were applied to visualize gene family membership among species.

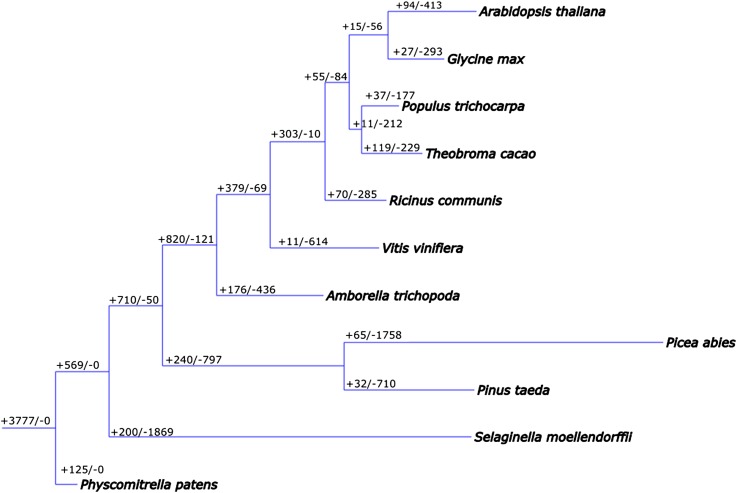

Gene family gain-and-loss phylogenetics

The DOLLOP v3.695 program from the Phylip package (Felsenstein 1989) was used to reconstruct a parsimonious tree explaining the gain and loss of gene families under the DOLLOP parsimony model. The DOLLOP algorithm estimates phylogenies for discrete character data with two states (either a 0 or 1), which assumes only one gain but as many losses as necessary to explain the evolutionary pattern of states. The filtered 8519 gene families (containing 112,899 sequences representing 13 species, the small number of sequences from P. sitchensis excluded) were used to create a gene family gain-and-loss matrix. Gene families that represented all species were dropped from the input to DOLLOP, as their phylogenetic classification would be obfuscated by a disparate number of starting proteins per species in the analysis. Branch lengths were calculated by counting the number of gains or losses for a given node. To produce the final phylogenetic reconstruction, a manual curation step was introduced to bring the P. patens and Selaginella moellendorffii branches into agreement with known phylogenies. DOLLOP was rerun on this updated tree to reconstruct the final gene family configurations of the ancestral species. Only P. patens, S. moellendorffii, and their common ancestor were updated during this step. The fidelity of the reconstructed trees was evaluated against a known phylogeny available at Phytozome (Goodstein et al. 2012).

Tandem repeat identification

Tandem Repeat Finder (TRF) v4.0.7b (Benson 1999) was run with the following parameters: matching weight of 2, mismatch weight of 7, indel penalty of 7, match probability of 80, indel probability of 10, minimum score of 50, and a maximum period size (repeating unit) of 2000. Both the genome and transcriptome were examined and investigated for tandem content. To accurately assess the overall coverage and distribution of tandem repeats, we filtered overlaps by discriminating against multimeric repeats, following previously described approaches (Melters et al. 2013), and excluded those found within interspersed repeats, such as the long terminal ends of LTR transposable elements. Mononucleotides (period size of 1) were not scrutinized due to the high likelihood of error and/or repeat collapse in the assembly process. To maintain reproducibility, common nomenclature terms—such as “microsatellites” or simple sequence repeats (SSRs) describing 1- to 8-bp periods, “minisatellites” describing 9- to 100-bp periods, and “satellites” describing >100-bp periods—were used for classification. For comparative analysis, these methods were applied to the reference genomes of A. thaliana v1.6.7, V. vinifera v1.4.5, S. moellendorffii v1.0.0, C. sativus v1.2.2, and P. trichocarpa v2.1.0, each available through Phytozome (Goodstein et al. 2012). The draft genome sequences of P. glauca v1.0.0 (Birol et al. 2013), P. abies (Nystedt et al. 2013), and A. trichopoda v1.0.0 were included. Both the filtered TRF output and consensus sequences derived from clustering the filtered TRF output (UCLUST utility at 70% identity) were used as queries in similarity searches. USEARCH (E-value < 0.01) was used to search the PlantSat database (Macas et al. 2002). Potential centromeric sequences were assessed by finding the monomeric tandem array that covered the largest amount of the genome. Interstitial and true telomeric sequences were isolated from the filtered TRF output by searching for (TTTAGGG)n motifs (n > 3 and length > 1 kbp). The thresholds applied were based on conservative estimates from telomere restriction fragment lengths described for P. taeda (Flanary and Kletetschka 2005).

Homology-based repeat identification

RepeatMasker 3.3.0 (RepeatMasker 2013) was used to identify previously characterized repeats. RepeatMasker was run using standard settings on the entire genome, with PIER 2.0 as a repeat library (Wegrzyn et al. 2013). A masked version of the genome was generated at this stage. Redundancy was eliminated through custom Python scripts by matching each reference base pair with the highest scoring alignment. For full-length estimates, we required that the genomic sequence and the reference PIER elements aligned with at least 80% identity and 70% coverage. Repeat content in introns was independently characterized using the same methodology. High-copy elements were identified by sorting families by full-length copy number. High-coverage elements were determined by sorting families by base-pair coverage, including both full-length and partial hits. MITE Hunter (release 11/2011) (Han and Wessler 2010) was used to search for miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements (MITEs) within intronic regions.

De novo repeat identification

The workflow for characterization and annotation of novel repeats largely mirrored that described in Wegrzyn et al. (2013). REPET 2.0 (Flutre et al. 2011) was used to identify sequences to form the repeat library for CENSOR 4.2.27 (Kohany et al. 2006). REPET’s de novo repeat discovery performs an all-versus-all alignment of the input sequence, an unscalable, computationally intensive operation. As such, the 63 longest scaffolds in the assembly were used as input, representing ∼1% of the genome (bin 1). For use in REPET’s classification steps, we provided REPET with the PIER database, in addition to a set of seven conifer repeat libraries described in Nystedt et al. (2013). A set of 405,109 publicly available full and partial P. taeda and Pinus elliottii transcripts were provided to REPET for host gene identification.

Previously characterized elements were removed using the PIER and spruce repeat databases and the blastn-blastx structural filters proposed in Wicker et al. (2007) and implemented in Wegrzyn et al. (2013). Previously classified elements were identified by blastn alignments passing the 80-80-80 threshold (80% identity covering 80% of each sequence for at least 80 bp). Unclassified elements were analyzed using blastx against a database of ORFs, recovered from the PIER/spruce nucleotide database with USEARCH’s “findorfs” utility at default parameters (Edgar 2010). Elements that were classified only to the superfamily level and unclassified repeats were separately clustered with UCLUST (Edgar 2010) at 80% identity. Consensus sequences for each cluster were derived from multiple alignments built with MUSCLE (Edgar 2010) and PILER (Edgar and Myers 2005). Finally, separate clusters were chained into families in which each cluster’s consensus sequence aligned with at least 80% identity with at least one other sequence in the family. Further classification of LTR retroelement families was performed using the in-house tool, GCclassif (Figure S1 and File S4).

Results and Discussion

Sequence alignments

Aligning the 83,285 de novo-assembled transcripts to the genome allowed us to infer information about gene regions, including introns and repeats (Table 1). At a stringency of 98% query coverage and 98% identity, 30,993 transcripts mapped to the genome, most of which (29,262) mapped with a unique hit; 1731 transcripts mapped to two or more genomic regions. Relaxing the cutoff criteria to 95% identity and 95% query coverage resulted in increases in the number of transcripts with unique (43,972) and non-unique hits (5409). At 95% identity and 50% query coverage, the number of transcripts with unique hits to the genome rose to 44,469, and transcripts aligning to more than one locus to 28,116. Possible reasons for a transcript aligning to two or more genomic locations include gene duplications, pseudogenes, assembly errors, and actively transcribed retroelements in the transcriptome assembly.

Table 1. Mapping EST/transcriptome resources against P. taeda version 1.01 genome.

| Project | Total sequence | Identity | Coverage | Unique hits | Non-unique hits | Total % mapped |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. taeda (reclustered ESTs) | 45,085 | 98 | 98 | 26,700 | 712 | 60.8 |

| P. taeda (reclustered ESTs) | 45,085 | 98 | 95 | 29,676 | 1,845 | 69.91 |

| P. taeda (reclustered ESTs) | 45,085 | 95 | 95 | 31,324 | 2,074 | 74.01 |

| P. taeda (reclustered ESTs) | 45,085 | 95 | 50 | 29,744 | 5,486 | 78.14 |

| P. taeda (de novo) | 83,285 | 98 | 98 | 29,262 | 1,731 | 35.21 |

| P. taeda (de novo) | 83,285 | 98 | 95 | 42,822 | 5,130 | 57.58 |

| P. taeda (de novo) | 83,285 | 95 | 95 | 43,972 | 5,409 | 59.29 |

| P. taeda (de novo) | 83,285 | 95 | 50 | 44,469 | 28,116 | 87.15 |

| P. palustris (454) | 16,832 | 95 | 95 | 11,242 | 719 | 71.06 |

| P. palustris (454) | 16,832 | 95 | 50 | 11,181 | 1,949 | 78.06 |

| P. lambertiana (454 + RNASeq) | 40,619 | 95 | 95 | 13,134 | 317 | 33.11 |

| P. lambertiana (454 + RNASeq) | 40,619 | 95 | 50 | 23,376 | 3,792 | 66.88 |

| P. banksiana (TreeGenes clusters) | 13,040 | 95 | 95 | 9,703 | 513 | 78.34 |

| P. banksiana (TreeGenes clusters) | 13,040 | 95 | 50 | 9,470 | 1,473 | 83.92 |

| P. contorta (TreeGenes clusters) | 13,570 | 95 | 95 | 9,575 | 396 | 73.48 |

| P. contorta (TreeGenes clusters) | 13,570 | 95 | 50 | 9,534 | 1,083 | 78.24 |

| P. pinaster (TreeGenes clusters) | 15,648 | 95 | 95 | 9,738 | 943 | 68.26 |

| P. pinaster (TreeGenes clusters) | 15,648 | 95 | 50 | 10,221 | 2,491 | 81.24 |

To elucidate how genome fragmentation affected our ability to map sequence to the genome, the v1.01 genome scaffolds were sorted by descending length and divided into 100 bins, with each bin containing ∼1% of the genomic sequence. Peaks in the gap region content were found in bin 59 (36.0% “N” bases) and in bin 82 (47.8% “N” bases), reflecting gaps due to linking libraries (Figure S2A). While gap-region content is greatly reduced in bins 86–100, these same bins show a sharp decrease in scaffold size and hence a sharp increase in the number of scaffolds per bin (Figure S2B). As expected, the ability to align transcripts to the genome decreased as the scaffold length shortened, with 56.4% of these transcript mappings occurring in the first 25 bins, and just 8.5% in the last 25 bins (Figure S2C).

Using the same techniques, we produced transcriptome-to-genome alignments beyond those generated with the de novo transcriptome using existing EST and transcriptome data for loblolly pine and other closely related species (Table 1). A total of 74.1% of the loblolly pine reclustered ESTs mapped at 95% query coverage, 95% sequence identity. Sequencing technology did not affect the percentage of sequence sets aligning to the genome as much as the phylogenetic relationships among the species. P. palustris is most closely related to loblolly pine and obtains mapping rates similar to the reclustered ESTs at 71.1% with 95% query coverage and 95% identity. P. lambertiana is most distant, and this is reflected in the minimal mapping success of the transcripts (Table 1).

The common lineage of the angiosperms and the gymnosperms split >300 MYA (Jiao et al. 2011), impeding searches for nucleic acid sequence homology between angiosperms and loblolly pine. However, we expect a subset of proteins to remain relatively conserved over multiple geological periods. The results of mapping and aligning three protein data sets to the loblolly pine v1.01 genome are shown in Table 2, where we determined the initial protein-to-scaffold mapping with blat and created a refined alignment with exonerate. The subset of the PLAZA data set used includes over half a million proteins from 24 nongymnosperm plant species, 16.8% of which aligned to the loblolly pine genome. Aligning proteins from members of the genus Picea (last common ancestor 85 MYA) to the loblolly pine genome proved more fruitful. Seventy-five percent of >10,000 full-length Sitka spruce proteins [the majority predicted from high-quality full-length Sanger-sequenced complementary DNA data (Ralph et al. 2008)] aligned to the genome. Sixty-nine percent of 22,070 P. abies proteins from the Congenie project aligned to the loblolly pine genome. A total of 84% of the loblolly pine proteins gleaned from the transcriptome assembly aligned.

Table 2. Mapping protein sequence against P. taeda version 1.01 genome.

| Full-length proteins from: | Total sequence | Unique hits | Non-unique hits | Total % mapped | Data source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. abies | 22,070 | 11,580 | 3,638 | 68.95 | Nystedt et al. (2013) |

| P. sitchensis | 10,793 | 6,516 | 1,574 | 74.95 | GenBank |

| P. taeda | 83,285 | 45,656 | 24,427 | 84.15 | Current assembly |

| PLAZA (24 species) | 653,613 | 90,149 | 19,492 | 16.77 | Van Bel et al. (2012) |

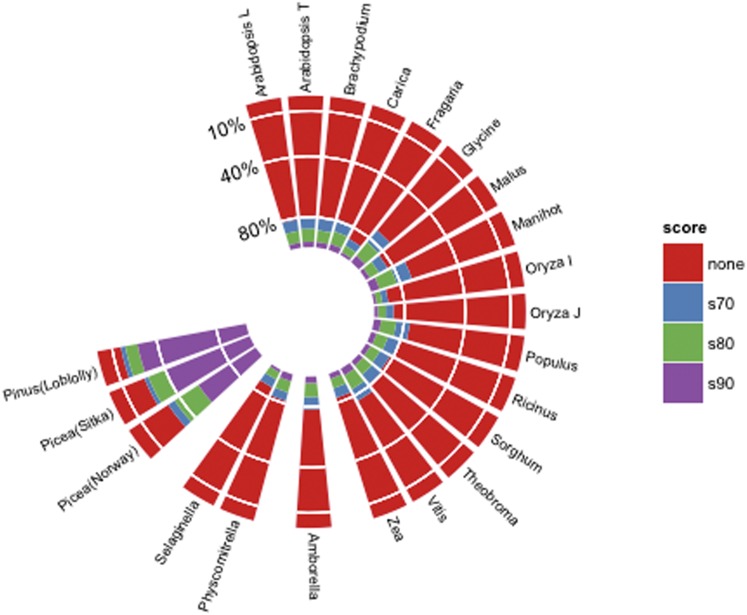

Fewer than 30% of each PLAZA species protein set aligned to the genome at our initial cutoff (query coverage ≥70% and ESS ≥70). For 18 species in the PLAZA data set, as well as A. trichopoda, P. sitchensis, P. abies, and translated P. taeda transcriptome sequences, we further break down the protein-to-genome alignments that passed the initial cutoff into three categories: ESS ≥ 90, 90 < ESS ≤ 80 and 70 ≤ ESS < 80 (Figure 1). In the ESS ≥ 90 category, 45.2% of Norway spruce proteins, 60.6% of Sitka spruce proteins, and 70.0% of loblolly pine proteins aligned to the genome (File S2). The differences between the two spruce protein sets may be partially attributed to the sequencing technologies employed to generate the original transcriptomes (Sanger vs. next-generation technologies).

Figure 1.

Orthologous proteins derived from PLAZA and mapped to the loblolly pine genome (1.01) at various similarity scores. Also included are proteins based on Picea sitenchis sequence from GenBank, P. abies proteins from the Congenie Genome project, and proteins from the Amborella Genome project. These data were generated by examining the proteins for which at least 70% of the protein was included in the local alignment. We then generated for each species, four categories based on the ESS: s90 (100 < ESS < 90), s80(90 < ESS < 80), s70 (80 < ESS < 70) and none (70 < ESS).

Gene annotation

The MAKER-P annotation pipeline considered the transcript alignments in addition to ab initio models to predict potential coding regions. The initial predictions generated >90,000 gene models; ∼44% were fragmented or otherwise indicative of pseudogenes. Previous studies of pines have identified pseudogene members in large gene families (Wakasugi et al. 1994; Skinner and Timko 1998; Gernandt et al. 2001; Garcia-Gil 2008), and pseudogene content may be as much as five times that of functional coding regions (Kovach et al. 2010). Conservative filters were therefore necessary to deduce the actual gene space. The multi-exon gene model requirement is likely biased against intronless genes, but it reduces false positives associated with repeats and pseudogenes. Because ∼20% of Arabidopsis and O. sativa genes are intronless (Jain et al. 2008), it is likely that our approach ignores as much as 20% of the gene space.

After applying multi-exon and protein domain filters, 50,172 gene models remained. These transcripts ranged from 120 bp to >12 kbp in length and represented >48 Mbp of the genome, with an average coding sequence length of 965 bp (Table S2). Since a recognizable protein domain was a requirement, the majority of gene models are functionally annotated (File S3). Functional annotations of the translated sequences revealed that 49,196 (98%) of the transcripts have homology to existing sequences in NCBI’s plant protein and nr database. A slightly smaller number, 48,614 (97%), align to a functionally characterized gene product.

The full-length gene models that are well supported by aligned evidence and with an AED score < 0.20 total 15,653. These high-confidence transcripts cover >30 Mbp of the genome and have an average coding sequence length of 1295 bp with an average of three introns per gene (Table S2). Once again, 98% of these sequences are functionally annotated; ∼23% of the high-quality alignments are to V. vinifera. Given the fragmentation of the genome and the lack of intronless genes reported, true estimates of gene number may be as high as 60,000, particularly given the 83,285 unique gene models generated from broad P. taeda RNA evidence (File S1). Previous estimates of gene number in conifers vary widely. The gene content of white spruce is estimated to be ∼32,000 (Rigault et al. 2011). While comprehensive evaluation of maritime pine transcriptomic resources from EuroPineDB produced >52,000 UniGenes (Fernandez-Pozo et al. 2011).

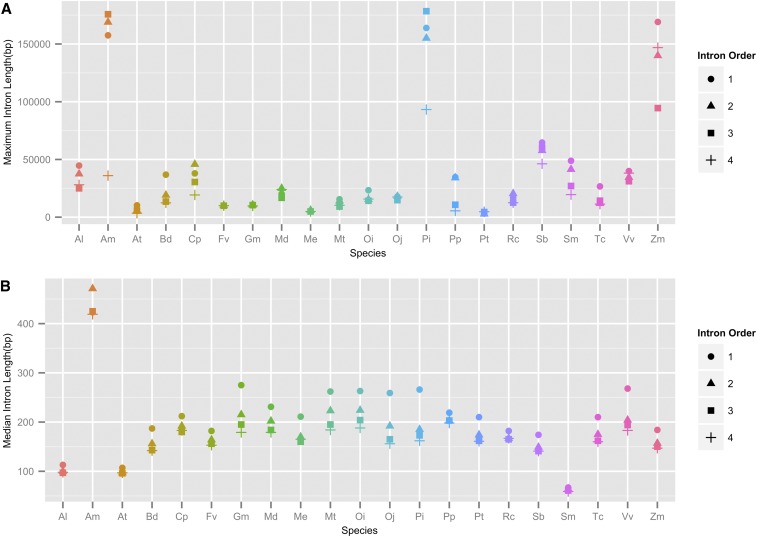

Introns

Plant introns are typically shorter than those found in mammals (Shepard et al. 2009). The gene models derived from MAKER-P yielded maximum intron lengths >50 kbp, with several >100 kbp. A total of 147,425 introns were identified in the 50,172 transcripts. A requirement of <25% gap-region content was used to calculate values on 144,425 introns (Table 3). The average length of these introns was >2.7 kbp, with a maximum length of 318 kbp. Compared with mapping the loblolly pine transcriptome against the genome, we identified only 3350 sequences (13%) with one or more introns. Among these sequences, 10,991 introns were present, an average of 3.28 per sequence. Their maximum reported lengths are ∼150 kbp. The number of genes in the transcriptome containing introns is much lower than in other eukaryotes, although this is likely skewed by the requirement of full-length genes against a fragmented genome. For this reason, we focused the analysis on our high-confidence set of 15,653 MAKER-derived transcripts, which had 48,720 usable introns with an average length of 2.4 kbp. The longest reported intron in this set is 158 kbp. In total, 1610 introns were between 20 and 49 kbp in length, 143 between 50 and 99 kbp, and 18 >100 kbp in length (File S5). When compared with the protein sequences from 22 other plant species aligned to their genomes, only A. trichopoda and Z. mays reported similar maximum values (Figure 2A). The median and mean values for P. taeda introns are comparable to the other plant species (Figure 2B), although it is likely that our intron lengths are an underestimate due to the fragmentation of the assembly. Estimates from the recent genome assembly of P. abies reported intron lengths >20 kbp and a maximum length of 68 kbp (Nystedt et al. 2013). Long intron lengths have been estimated for pines for some time and are noted to contribute to their large genome sizes (Ahuja and Neale 2005).

Table 3. Summary of intron statistics.

| Total sequences | Total no. of introns | Introns with minimal gap regions | Longest intron (bp) | Average intron length (bp) | No.of introns 20–49 kbp | No. of first introns 20–49 kbp | No. of introns 50–99 kbp | No. of first introns 50–99 kbp | No. of introns >100 kbp | No. of first introns >100 kbp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50,172 | 147,425 | 144,579 | 318,524 | 2741 | 5460 | 1840 | 699 | 343 | 108 | 63 |

| 15,653 | 49,720 | 48,720 | 158,878 | 2396 | 1810 | 592 | 143 | 84 | 18 | 13 |

Figure 2.

Intron lengths were compared for 23 species, which include 21 species curated by the PLAZA project, A. trichopoda, and P. taeda. (A) Comparison of maximum intron lengths for the first four intron positions in the CDS. (B) Comparisons of median intron lengths for the same species for the first four intron positions in the CDS. Species codes are the following: Al (Arabidopsis lyrata), Am (A. trichopoda), At (A. thaliana), Bd (B. distachyon), Cp (Carica papaya), Fv (Fragaria vesca), Gm (G. max), Md (Malus domestica), Me (Manihot esculenta), Mt (Medicago truncatula), Oi (O. sativa ssp. indica), Oj (O. sativa ssp. japonica), Pi (P. taeda), Pp (P. patens), Pt (P. trichocarpa), Rc (R. communis), Sb (S. bicolor), Sm (S. moellendorffii), Tc (T. cacao), Vv (V. vinifera), and Zm (Z. mays).

Long intron sizes delay the production of protein products and increase the error rate in intron splicing in animals (Sun and Chasin 2000). In plants, increasing intron length is positively correlated with gene expression (Ren et al. 2006). In most eukaryotes, the first (primary) intron is usually the longest (Bradnam and Korf 2008) and is generally in the 5′ UTR. The first intron in the CDS region is also generally longer than distal introns (Bradnam and Korf 2008). This is largely true for loblolly pine, as well.

IME refers to specific, well-conserved sequences in introns that enhance expression. IMEs in Arabidopsis and O. sativa introns near the transcription start site have greater signal than those more distal (Rose et al. 2008; Parra et al. 2011). We applied the word-based discriminator IMEter, designed to identify these signals in intronic sequences to the first introns in the CDS (as a comprehensive set of introns in the 5′ UTR was not available). We identified 400 primary CDS introns between 20 and 49 kbp, 38 between 50 and 99 kbp, and 8 >100 kbp in length, all with a IMEter score > 10, and several with a score >20, which suggests strong enhancement of expression. Transcripts in this category include those annotated as transcription factors (WRKY), cysteine peptidases (cathepsins), small-molecule transporters (nonaspanins), transferases, and several that are less characterized (File S5).

Orthologous proteins

A comparison of the 47,207 clustered loblolly pine gene models to the 352,151 proteins curated from 13 plant species resulted in 20,646 unique gene families (after filtering the domains that exclusively annotate as transposable elements) representing 361,433 (90.5%) sequences with an average of 17 genes per family (File S6). As with most de novo clustering methods, these predictions are likely to be an overrepresentation of family size and number, since clusters are formed for all non-orphan predictions by MCL (Bennetzen et al. 2004). The families range in size from 5229 members from 14 species to 2 members from one species.

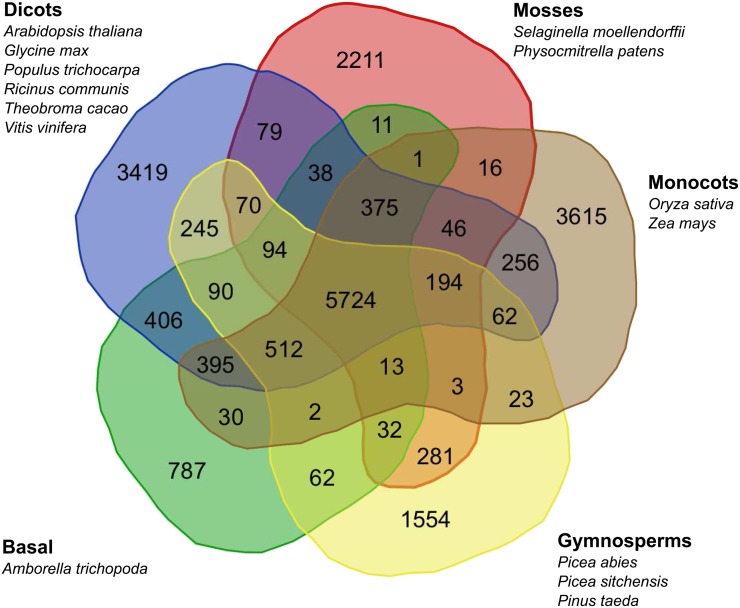

P. taeda genes belong to 7053 gene families (File S7). Distribution of gene families among conifers (P. abies, P. sitchensis, and P. taeda); a basal angiosperm species, A. trichopoda; mosses (S. moellendorffii and P. patens); monocots (O. sativa and Z. mays); and dicots (A. thaliana, G. max, P. trichocarpa, T. cacao, R. communis, and V. vinifera) are shown in Figure 3. We identified 1554 conifer-specific gene families that contain at least one sequence in the three conifer species (P. taeda, P. abies, and P. sitchensis) (File S8), slightly higher than the 1021 reported by the P. abies genome project (Nystedt et al. 2013). Some of the largest families annotated include transcription factors (Myb, WRKY, and HLH), oxidoreductases (i.e., cytochrome p450), disease resistance proteins (NB-ARC), and protein kinases. Among the conifer-specific families, 159 were unique to P. taeda, 32 of which had 5 or more members (Neale et al. 2014).

Figure 3.

Results of the TRIBE-MCL analysis that distinguishes orthologous protein groups. The Venn diagram depicts a comparison of protein family counts of five plant classifications: gymnosperms (P. abies, P. sitchensis, and P. taeda), monocots (O. sativa and Z. mays), mosses (P. patens and S. moellendorffii), dicots (A. thaliana, G. max, P. trichocarpa, R. communis, T. cacao, and V. vinifera), and a basal angiosperm (A. trichopoda).

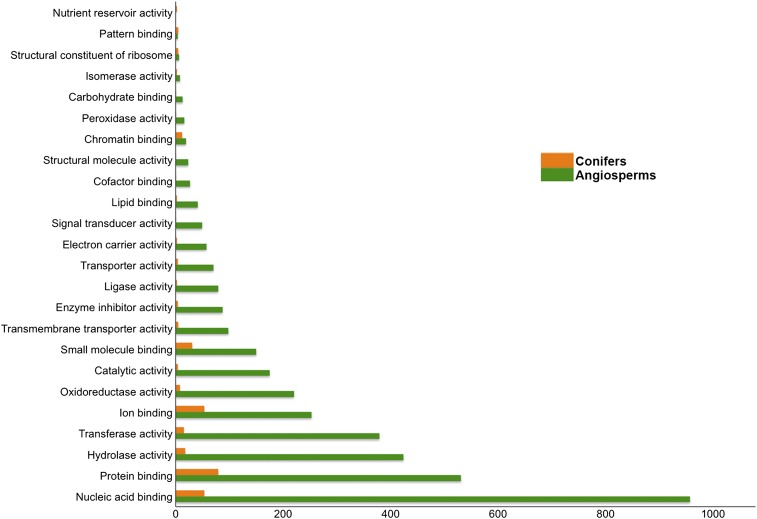

Sixty-six unique molecular function terms apply to the 8795 (42.45%) gene families annotated in 14 species. A total of 24 molecular function terms describe 241 of the 1554 conifer-specific gene families (Figure 4). When comparing the GO distribution of all 14 species against the conifer-specific families, four of the top five GO assignments are the same (protein binding, nucleic acid binding, ion binding, and hydrolase activity), with conifers having an additional large contribution from small-molecule binding (31 families). The 11,686 gene families with no contributions from conifers are described by 43 molecular function terms (Figure 4). The largest categories in this group include: hydrolase activity, nucleic acid binding, peroxidase activity, and lyase activity. Of the 7053 gene families with a P. taeda member, 6094 (86.4%) have at least one protein domain assignment and 5249 (74.42%) have molecular function GO term assignments. Since these families have members in most of the plant species analyzed, they are likely conserved across eukaryotes, thus reflecting their higher annotation rate. The largest categories containing P. taeda include protein binding, transferase activity, and nucleic acid binding, similar to recent findings for P. glauca and Picea mariana (Pavy et al. 2012). Examination of these large gene families across species also provides a preview of intron expansion, examples of which are seen in several gene families, including those involved in lipid metabolism, ATP binding, and hydrolase activity (Figure S3 and File S9).

Figure 4.

Gene Ontology distribution normalized for molecular function. The orthologous groups defined are exclusive to the angiosperms and conifers, respectively. The angiosperm set includes A. trichopoda, A. thaliana, G. max, P. trichocarpa, P. patens, S. moellendorffii, R. communis, O. sativa, T. cacao, V. vinifera, and Z. mays. The conifer set includes P. abies, P. sitchensis, and P. taeda.

Gene family gain-and-loss phylogenetics

Using DOLLOP, we constructed a single maximum parsimony tree from all TRIBE-MCL clusters containing five or more genes. This represented 10,877 gene families with a mean size of 31 genes and a total of 336,571 splice forms. Smaller gene families contributed noise to phylogenetic reconstruction that may be due to overclassification of the smaller family sizes. The final phylogenetic matrix contained 13 of the 14 species in the original MCL analysis with 8519 gene families of size ≥5. P. sitchensis was removed from the analysis because of the partial sequence representation.

The resulting tree presents our best estimate of gene family evolution for the 13 focal species (Figure 5 and Table S3). Note that the gymnosperm–angiosperm split (Pavy et al. 2012; Nystedt et al. 2013) is reproduced and represents the longest internal edge in the reconstruction. The gymnosperm common ancestor is separated from the rest of the tree by a large number of gains and losses. Similarly, there are also many lineage-specific gains and losses from the ancestral gymnosperm to the two extant gymnosperms. Notably, there are more gene families not present in gymnosperms than present in angiosperms. We observe this as many more losses than gains on the gymnosperm side of the gymnosperm–angiosperm split.

Figure 5.

Parsimonious tree predicted by DOLLOP with protein families derived from the MCL analysis of size ≥5. The gains and losses of 13 species (A. thaliana, A. trichopoda, G. max, O. sativa, P. patens, P. trichocarpa, P. abies, P. taeda, R. communis, S. moellendorffii, T. cacao, V. vinifera, and Z. mays) are indicated on tree nodes and branches.

Tandem repeat identification

Tandem repeats are the chief component of telomeres and centromeres in higher order plants and other organisms. They are also ubiquitous across heterochromatic, pericentromeric, and subtelomeric regions (Richard et al. 2008; Navajas-Perez and Paterson 2009; Cavagnaro et al. 2010; Leitch and Leitch 2012). Tandem repeats affect variation through remodeling of the structures that they constitute; they modify epigenetic responses on heterochromatin and alter expression of genes through formation of secondary structures, such as those found in ribosomal DNA (Jeffreys et al. 1998; Richard et al. 2008; Gemayel et al. 2010). Present at ∼5.6 million loci (Table S4), tandem repeats seem unusually abundant in loblolly pine. However, these loci represent only ∼2.86% of the genome, consistent with previous studies of loblolly pine (Hao et al. 2011; Magbanua et al. 2011; Wegrzyn et al. 2013) and spruce (2.71% in P. glauca and 2.40% in P. abies). Conifers are in the middle of the spectrum of tandem content among nine plant species evaluated, with estimates ranging from 1.53% in C. sativus to 4.29% in A. trichopoda (File S10).

Clustering at 70% identity cuts the number of unique tandem repeat loci to less than a quarter its original size (from 5,696,347 to 1,411,119 sequences), with the largest cluster having 4999 members. This suggests an abundance of highly diverged yet somewhat related repeats, as has been described by others (Kovach et al. 2010; Wegrzyn et al. 2013). When accounting for overlap with interspersed repeat content, loblolly pine’s total tandem repeat coverage falls to 0.78% of the genome (Table S4 and Table S5). Only 33.8% of tandem content is found outside of interspersed repeats, including the LTR retrotransposons that make up the majority of conifer genomes (Nystedt et al. 2013; Wegrzyn et al. 2013). Further blurring the line between these two classes of repeats, retrotransposons have been shown to preferentially insert into pericentromeric heterochromatin of rice and SSR-rich regions of barley (Ramsay et al. 1999; Kumekawa et al. 2001)

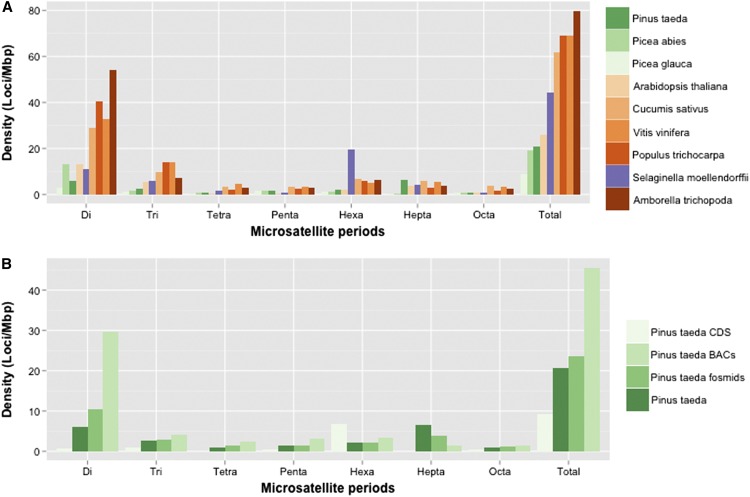

Considering microsatellites, the P. taeda genome has the densest and highest coverage of microsatellites of any conifer to date (0.12%, 467,040 loci), although not by a wide margin (Figure 6A and Table S4). Heptanucleotides are statistically more represented in loblolly pine than in the other two conifers (chi square test, χ2 = 7.367, d.f. = 2, P = 0.0251) (Figure 6A). AT-rich di- and trinucleotides are common in dicot plants (Navajas-Perez and Paterson 2009; Cavagnaro et al. 2010). Among conifers, (AG/TC)n is the most common dinucleotide in loblolly pine, while (AT/TA)n and (TG/AC)n are favored in P. abies and P. glauca, respectively. The most common trinucleotides are (AAG)n in loblolly pine, (ATT)n in P. abies, and (ATG)n in P. glauca (File S11). These findings support the notions that microsatellites are unstable and that microsatellite secondary structures are likely more conserved than their specific sequences (Jeffreys et al. 1998; Richard et al. 2008; Navajas-Perez and Paterson 2009; Gemayel et al. 2010; Melters et al. 2013). The CDS of loblolly pine is depleted in microsatellites compared to the full genome, but is denser in hexanucleotides and almost equal in trinucleotides (Figure 6B). Multiples of three (e.g., trinucleotides, hexanucleotides) are normally conserved in coding regions due to selection against frameshift mutations (Cavagnaro et al. 2010; Gemayel et al. 2010).

Figure 6.

(A) Microsatellite density for three conifer genomes (green), one clubmoss genome (purple), and five angiosperm genomes (orange), (loci per megabase). (B) Microsatellite density (loci per megabase) of the coding sequence of the loblolly pine genome compared to the v1.0 genome and two other loblolly genomic data sets (BACs and fosmids).

Minisatellites (period length of 9–100) are also slightly more represented in loblolly pine at ∼4.7 million loci representing 1.76% of the genome, compared to 1.72% in P. glauca and 1.53% in P. abies (Table S4 and Table S5). Satellites (period length of 100+) follow a similar pattern (P. taeda, 0.98%; P. abies, 0.77%; and P. glauca, 0.96%) (Table S4). Minisatellites seem to make up the overwhelming majority of the tandem repeat content. Different assemblies and/or sequencing technologies alter the quantity of tandem repeat content by as much as twofold, as can be seen by comparing the microsatellite density between the loblolly BAC assemblies, fosmid assemblies, and the full genome (Figure 6B) (Wegrzyn et al. 2013). Tandem repeats are troublesome for the assembly of large genomes, which are often partial toward dinucleotide and 9- to 30-bp periods (Figure S4) (Navajas-Perez and Paterson 2009). In fact, the top three period sizes in coverage of the genome are 27, 21, and 20 bp, in that order. Minisatellites, especially those ∼20 bp in length, contribute as much or more to the genome than microsatellites. This trend extends to other conifers (Table S5) as well as to angiosperms, including C. sativus, A. thaliana, and P. trichocarpa. In total, two consensus sequences and five monomer sequences, representing approximately five different species from PlantSat, share homology with loblolly pine satellites and minisatellites. The average coverage, however, is low (∼45%), with the most abundant hits to centromeric sequences of Pinus densiflora and Z. mays (Table S6).

The telomeric sequence (TTTAGGG)n, first identified in A. thaliana (Richards and Ausubel 1988), has the most loci (23,926) of any tandem repeat motif and the most overall sequence coverage (at ∼2.1 Mbp, or ∼0.01% of the genome). Its instances range from 1.04 to 9.5 kbp in length and from 2 to 317 in numbers of copies of the monomer per locus. Variants like those from tomato [TT(T/A)AGGG]n (Ganal et al. 1991) and multimers with those variants were not assessed, so our estimate of the amount of telomeric sequence is likely low. These estimates include the true telomeres, which are on the longer side of the spectrum in length, and copies, along with ITRs. The longest locus is 15 kbp. Telomeres appear especially long in pine (e.g., 57 kbp in Pinus longaeva) (Flanary and Kletetschka 2005), and in our assembly could be positively affected from the megagametophyte source, as has been shown in Pinus sylvestris (Aronen and Ryynanen 2012). These ITRs are remnants of chromosomal rearrangements that occupy large sections of gymnosperm chromosomes (Leitch and Leitch 2012). A potential centromere monomer, TGGAAACCCCAAATTTTGGGCGCCGGG (27 bp), is moderately high in frequency across the scaffolds and represents the second highest fraction of the genome covered, with 5183 loci covering ∼1.8 Mbp (∼0.009% of the genome). Its period size is substantially shorter than the ∼180-bp average from other plants (Melters et al. 2013). About 0.3% of the scaffolds contain this potential centromeric sequence, and these scaffolds average 779 bp in length. A close variant, TGGAAACCCCAAATTTTGGGCGCCGCA (21 bp), also high in coverage and frequency, shares homology (E-value = 3e-9; 100% identity) with the repetitive sequence of an 881-bp probe (GenBank accession: AB051860) developed to hybridize to centromeric and pericentromeric regions of P. densiflora (Hizume et al. 2001). Perhaps this second variant forms a type of “library” that facilitates centromere evolution by forming a higher-order repeat structure with the first variant. Whether the centromere is evolving in pines cannot be deduced by assembling short reads, as they fail to accurately capture such structures (Melters et al. 2013). It is also important to note that the actual coverage of centromeric sequence is likely much higher than reported, as these two variants likely do not represent the entirety of the centromere. Homologs were not found in P. abies or P. glauca, consistent with it being specific to the subgenus Pinus (Hizume et al. 2001). The presence of the Z. mays centromeric sequence along with the Pinus centromeric sequence conceivably supports the hypothesis that although certain satellites are conserved across species, their localization is not (Leitch and Leitch 2012).

Homology-based repeat identification

RepeatMasker, with PIER as a repeat library, identified 14 Gbp (58.58%) of the genome as retroelements, 240 Mbp (1.04%) as DNA transposons, and 1.2 Gbp (5.06%) as derived from uncategorized repeats (Table 4). Considering only full-length repeats, there are 179,367 (5.61%) retroelements, 11,026 (0.13%) DNA transposons, and 56,024 (0.48%) uncategorized repeats. Most studies in angiosperms have found a surplus of class I compared to class II content (Kumar and Bennetzen 1999; Civáň et al. 2011), and loblolly pine continues this trend with or without filtering for full-length elements. The ratio of uncategorized repeats to all repeats is ∼1:12 for the genome, as seen in a previous BAC and fosmid study (Wegrzyn et al. 2013). Introns contained 34.52% LTRs, 54.28% retrotransposons, and 3.52% DNA transposons (Figure S5 and File S12). First introns <20 kbp have the lowest amount of repetitive content at 50.26%, while distal introns >100 kbp have the highest amount at 73.75%. We expected higher repetitive content in longer introns, since intron expansion can be partially attributed to proliferation of repeats.

Table 4. Summary of interspersed repeats from homology-based identification.

| Full-length | All repeats | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class | Order | Superfamily | No. of elements | Length (bp) | % genome | No. of elements | Length (bp) | % genome |

| I | LTR | Gypsy | 49,183 | 264,644,712 | 1.14 | 5,127,514 | 2,544,140,822 | 10.98 |

| I | LTR | Copia | 36,952 | 207,086,169 | 0.89 | 4,385,545 | 2,119,375,506 | 9.14 |

| Total LTR | LTR | 179,367 | 962,249,326 | 4.15 | 17,432,917 | 9,660,836,674 | 41.68 | |

| I | DIRS (Dictyostelium transposable element) | 4,935 | 26,820,856 | 0.12 | 596,008 | 335,540,558 | 1.45 | |

| I | Penelope | 4,966 | 13,456,930 | 0.06 | 422,276 | 188,350,501 | 0.81 | |

| I | LINE | 15,353 | 53,411,263 | 0.23 | 906,403 | 545,648,705 | 2.35 | |

| I | SINE | 137 | 68,023 | 0.00 | 670 | 182,264 | 0.00 | |

| Total RT(Retrotransposon) | 262,028 | 1,299,761,701 | 5.61 | 25,166,637 | 13,577,984,814 | 58.58 | ||

| II | TIR | 7,932 | 20,499,522 | 0.09 | 420,769 | 185,871,618 | 0.80 | |

| II | Helitron | 1,105 | 3,500,491 | 0.02 | 47,003 | 22,396,711 | 0.10 | |

| Total DNA | 11,026 | 31,035,610 | 0.13 | 519,708 | 240,545,369 | 1.04 | ||

| Uncategorized | 56,024 | 110,604,852 | 0.48 | 3,164,894 | 1,172,394,606 | 5.06 | ||

| Total interspersed | 336,037 | 1,458,952,566 | 6.29 | 29,249,206 | 15,145,555,948 | 65.34 | ||

| Tandem repeats | 210,810,342 | 0.91 | 210,810,342 | 0.91 | ||||

| Total | 1,669,762,908 | 7.20 | 15,356,366,290 | 66.25 | ||||

LTR retroelements make up 9.7 Gbp (41.68%) of the genome sequence, of which 2.5 Gbp (10.98%) are Gypsy elements and 2.1 Gbp (9.14%) are Copia elements (Table S7). Gypsy and Copia LTR superfamilies are found across the plant phylogeny and are often a significant portion of the repetitive content (Kejnovsky et al. 2012). Partial and full-length alignments have a 1.2:1 ratio of Gypsy to Copia elements; full-length elements show a slightly more skewed ratio of 1.3:1, lower than the previous estimate of 1.9:1 in P. taeda (Wegrzyn et al. 2013). Estimates in other conifers are, on average, 2:1 with the exception of Abies sibirica, which was reported 3.2:1 (Nystedt et al. 2013). Estimates in angiosperms represent a wide range: 1.8:1 in V. vinifera, 1:3 in P. trichocarpa, 2.8:1 in A. thaliana, and 1:1.2 in C. sativus (Wegrzyn et al. 2013). The large number of LTRs that cannot be sorted into superfamilies may be due to the presence of long autonomous retrotransposon derivatives (LARDs) and terminal-repeat retrotransposons in miniature (TRIMs) among LTR content. GCclassif was able to detect protein domains on many LTRs, but fewer than half were classifiable based on the ordering of their domains. These LTRs may be nonfunctional, requiring actively transposing elements to supply the genes needed for proliferation, similar to LARDs and TRIMs (Witte et al. 2001; Kalendar et al. 2004).

Non-LTR retroelement content is usually found at lower frequencies in conifers (Friesen et al. 2001). Long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs) cover 546 Mbp (2.35%) of the genome (Table S7), higher than the 0.71% previously recorded (Wegrzyn et al. 2013) and higher than in P. sylvestris (0.52%) and P. abies (0.96%) (Nystedt et al. 2013). Some angiosperms show comparable coverage of LINEs: 2.96% in Brachypodium distachyon (Jia et al. 2013), 2.82% in Brassica rapa (Wang et al. 2011), and 3.4% in C. sativus (Huang et al. 2009). LINEs are thought to have played roles in telomerase and gene evolution (Schmidt 1999). Short interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs) cover 268 kbp (0.001%), a miniscule portion of the genome, as previously reported (Wegrzyn et al. 2013). SINE content is similarly negligible in P. sylvestris and P. abies (Nystedt et al. 2013). Low ratios of non-LTR to LTR retroelements are also seen in most angiosperms (Jia et al. 2013).

DNA transposons make a negligible contribution to interspersed element content. Terminal inverted repeats (TIRs) cover 186 Mbp (0.80%) of the genome, and helitrons cover 22 Mbp (0.10%) of the genome (Table S7). Repeats within introns are involved in exon shuffling (Bennetzen 2005) and epigenetic silencing (Liu et al. 2004). As expected, introns are richer in DNA transposons, at 3.52%, compared to 1.04% across the genome, and 93% of intronic DNA transposon content is composed of TIRs, compared to 77% across the genome (File S12). MITEs have been identified in loblolly pine BACs (Magbanua et al. 2011) and are preferentially located near genes in rice (Zhang and Hong 2000). However, the methodologies that we applied extracted only two MITE sequences across 25 Mb of intron sequence. Class II content is lower in most conifers, including P. sylvestris, P. abies (Nystedt et al. 2013), and Taxus maireri (Hao et al. 2011). This has generally been the case in angiosperms as well (Civáň et al. 2011), although there are exceptions (Feschotte and Pritham 2007).

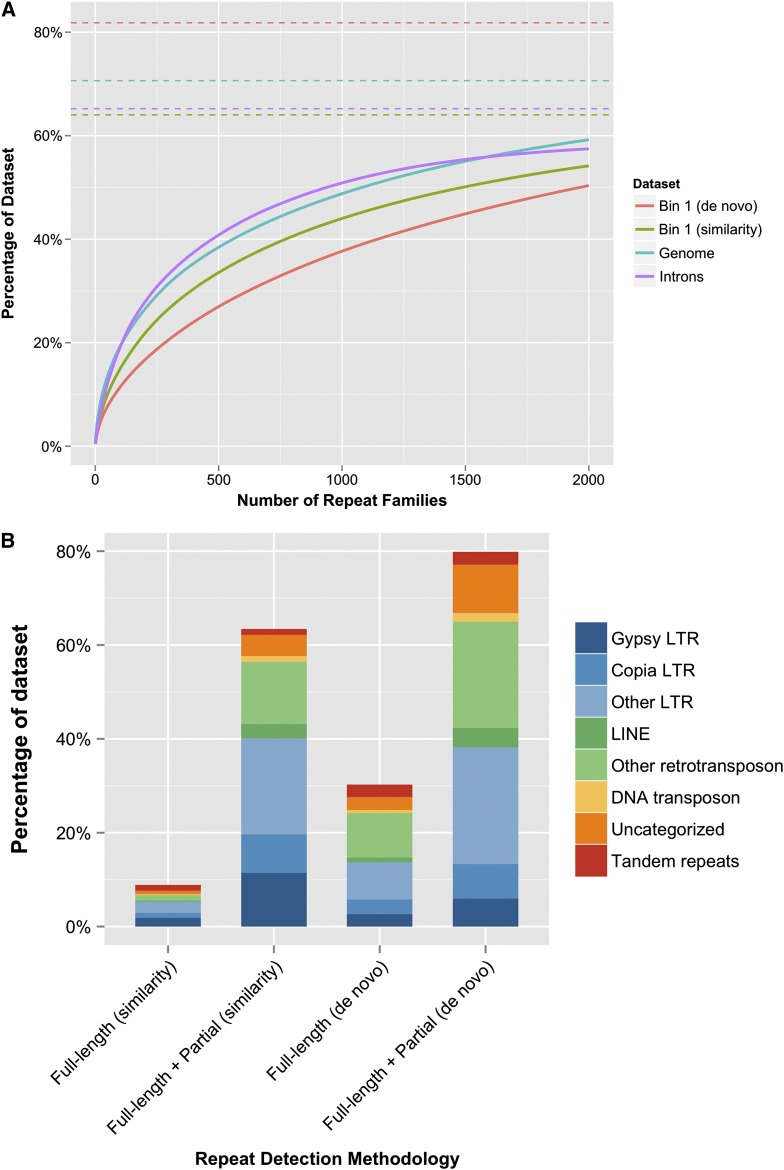

De novo repeat identification

Considering a smaller subset of the entire genome sequence allowed us to compare de novo and similarity-based repeat annotation methods. In the 63 longest scaffolds, REPET discovered 15,837 putative repeats (Table S8), forming just under 7000 novel repeat families. Full-length repeats cover 64 Mbp (28.2%) of the sequence set, and full-length and partial de novo sequences combined account for 180 Mbp (79.3%). This ratio is markedly different from the fraction of full-length repeats in the full genome determined by similarity alone. Full-length sequences identified as previously classified, or which could be classified to the superfamily level, cover 11.3 Mbp (4.98%) of the bin 1 sequence according to de novo analysis. Of these, 6.6 Mbp overlap with RepeatMasker’s similarity-based annotation of the bin. Full-length novel repeats cover 52.9 Mbp (23.26%) of the bin 1 sequence in the de novo analysis. Similarity analysis overlapped 7.4 Mbp of these repeats. As expected, REPET’s de novo contribution was left largely undiscovered by RepeatMasker’s similarity-based annotation method. In total, we see an overlap of 14 Mbp between our similarity and de novo annotation methods, and a total combined full-length repeat coverage of 69.7 Mbp.

Highly represented repeat families

High-coverage elements varied between similarity and de novo approaches. PtAppalachian, PtRLC_3, PtRLG_13, and PtRLX_3423 are shared among the top high-coverage elements (Table S9). Many of the high-coverage elements found are not highly represented in Wegrzyn et al. (2013), which used a similar approach. This corroborates a high rate of divergence and a high incidence of incomplete retrotransposon content. PtRLG_Conagree, the highest-coverage repeat, annotated 0.75% of the genome, covering 174 Mbp (Table S9). TPE1, a previously characterized Copia element, has the second-highest coverage with 114 Mbp (0.49%). Other highly represented elements include PtRLG_Ouachita, PtRLG_Talladega, PtRLX_Piedmont, PtRLG_Appalachian, and PtRLG_Angelina, which were previously characterized as part of a set of high coverage de novo repeat families (Wegrzyn et al. 2013). PtIFG7, a Gypsy element, covers 90 Mbp (0.39%) (Table S9). As previously noted in Kovach et al. (2010), no single family dominates the repetitive content, with the highest-coverage element, PtRLG_Conagree, accounting for <1% of the genome (Table S9). Gymny, thought to occupy 135 Mb in the genome with full-length elements (Morse et al. 2009), comprises only 3.3 Mbp; IFG7, thought to occupy up to 5.8% of the genome (Magbanua et al. 2011), occupies only 0.39% of the genome. The top 100 highest-coverage elements account for <20% of the genome (Figure 7A). Among high-coverage intronic repeats, PtRLX_106 and PtRLG_Appalachian were identified in both bin 1 and in the genome. Side-by-side comparisons of high-copy and high-coverage families show a much lower contribution per family in the introns, compared to the genome (Table S8 and Table S9).

Figure 7.

(A) Repeat family coverage. Repeat families on the x-axis are ordered by coverage in descending order. Solid lines illustrate cumulative coverage as more families are considered. Dashed lines represent the total repetitive content for that data set. (B) Comparison of bin 1 repetitive content for both partial and full-length annotations. “Full-length + Partial” refers to all full-length and partial hits, and “Percentage of dataset” is a function of the total length annotated by each classification.

The highly divergent nature of most of the transposable elements seems to conflict with the uniformity seen in those that are highly represented. A total of 4397 full-length PtAppalachian sequences and 2835 PtRLG_13 sequences were >80% similar to their reference sequences, and 1559 and 237 sequences align at >90% identity and 90% coverage, respectively. These alignments suggest that many of the highly represented elements may be actively transposing, despite the diverged nature of many transposable element families.

Repetitive content summary

In total, 15.3 Gbp (65.34%) of genomic sequence was labeled as interspersed content via homology (Table 4), while de novo estimates place total interspersed content at 79.3% (similarity and de novo combined in bin 1 yield 81.81%). This is consistent with the de novo figures reported by Wegrzyn et al. (2013) at 86% and by Kovach et al. (2010) at 80%, but is higher than in P. sylvestris at 52% (Nystedt et al. 2013), P. glauca at 40–60% (Hamberger et al. 2009; Liu et al. 2011; Nystedt et al. 2013), P. abies at 70% (Nystedt et al. 2013), Sorghum bicolor at 63% (Paterson et al. 2009), and Secale cereale at 69.3% (Bartos et al. 2008). Masking all repeat content results in the complete masking of 9 million scaffolds, covering 3.2 Gbp of sequence. Full-length elements cover only 7.20% of the genome, much lower than the 25.98% previously estimated in BAC and fosmid sequences (Wegrzyn et al. 2013).

Strict filters, as described in Wegrzyn et al. (2013), ensured the quality of the discovered de novo sequence, and the repeat library used in similarity analysis, PIER, was derived from de novo content in loblolly pine BACs and fosmids discovered with the same methodology. It is surprising, then, that similarity analysis characterized 66% of the genome sequence as repetitive, while de novo analysis characterized 79.3% of bin 1 as repetitive, suggesting a plethora of further high-quality novel repeat content. One possibility is that the large number of new repeat sequences discovered de novo may be due to TRIMs and LARDs, the latter for which transposition events yield high sequence variability even among mRNA transcripts (Kalendar et al. 2004). LARDs are a subset of LTRs and class I retrotransposons and could easily inflate the figures for these two categories while reducing the number and coverage of known superfamilies. High variability in retrotransposition is common among angiosperms and gymnosperms—not surprising, as reverse transcription is known to be highly error-prone (Gabriel et al. 1996). A single burst of retrotransposition can potentially result in hundreds of repeats, all independently diverging (El Baidouri and Panaud 2013). One such event may have occurred long ago in loblolly pine, resulting in the many ancient, diverged, single-copy repeat families being identified. Finally, we note that repetitive elements are a common obstacle in genome assembly; scaffold resolution may have decreased the amount of detectable repetitive content as repeats located on a terminal end of a sequence may be collapsed upon assembly. With this level of repetitive content, the likelihood of terminal repeat collapse is markedly higher than in smaller and less repetitive genomes.

Conclusion

We have presented a comprehensive annotation of the largest genome and first pine. The size of the genome and the absence of well-characterized sequence for close relatives presented significant challenges for annotation. The inclusion of a comprehensive transcriptome resource generated from deep sequencing of loblolly pine tissue types not previously examined was key to identifying the gene space. This resource, along with other conifer resources, provided a platform to train gene-prediction algorithms. The larger gene space enabled us to better quantify and examine the those that are unique to conifers, and potentially to gymnosperms. The long scaffolds available in our sequence assembly facilitated the identification of long introns, providing a resource to study their role in gene regulation and their relationship to the high levels of repetitive content in the genome. To characterize sequence repeats, we applied a combined similarity and de novo approach to improve upon our existing repeat library and to better define the components of the largest portion of the genome. This annotation will not only be the foundation for future studies within the conifer community, but also a resource for a much larger audience interested in comparative genomics and the unique evolutionary role of gymnosperms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The support and resources from the Center for High Performance Computing at the University of Utah are gratefully acknowledged. Funding for this project was made available through the U.S. Department of Agriculture/National Institute of Food and Agriculture (2011-67009-30030) award to D.B.N. at the University of California, Davis. This work used the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment, supported by National Science Foundation grant OCI-1053575, and, in particular, High Performance Computing resources of the partner centers at The University of Texas at Austin and Indiana University (grant ABI-1062432).

Note added in proof: See Zimin et al. 2014 (pp. 875–890) in this issue for a related work.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: M. Johnston

Literature Cited

- Ahuja M. R., Neale D. B., 2005. Evolution of genome size in conifers. Silvae Genet. 54: 126–137. [Google Scholar]

- Allona I., Quinn M., Shoop E., Swope K., St. Cyr S., et al. , 1998. Analysis of xylem formation in pine by cDNA sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95: 9693–9698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W., Lipman D. J., 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215: 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronen T., Ryynanen L., 2012. Variation in telomeric repeats of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.). Tree Genet. Genomes 8: 267–275. [Google Scholar]

- Bartos J., Paux E., Kofler R., Havrankova M., Kopecky D., et al. , 2008. A first survey of the rye (Secale cereale) genome composition through BAC end sequencing of the short arm of chromosome 1R. BMC Plant Biol. 8: 95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennetzen J. L., 2005. Transposable elements, gene creation and genome rearrangement in flowering plants. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 15: 621–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennetzen J. L., Coleman C., Liu R. Y., Ma J. X., Ramakrishna W., 2004. Consistent over-estimation of gene number in complex plant genomes. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 7: 732–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson G., 1999. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 27: 573–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birol I., Raymond A., Jackman S. D., Pleasance S., Coope R., et al. , 2013. Assembling the 20 Gb white spruce (Picea glauca) genome from whole-genome shotgun sequencing data. Bioinformatics 29: 1492–1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradnam K. R., Korf I., 2008. Longer first introns are a general property of eukaryotic gene structure. PLoS ONE 3: e3093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briones K. M., Homyack J. A., Miller D. A., Kalcounis-Rueppell M. C., 2013. Intercropping switchgrass with loblolly pine does not influence the functional role of the white-footed mouse (Peromyscus leucopus). Biomass Bioenergy 54: 191–200. [Google Scholar]

- Brown G. R., Gill G. P., Kuntz R. J., Langley C. H., Neale D. B., 2004. Nucleotide diversity and linkage disequilibrium in loblolly pine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101: 15255–15260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairney J., Zheng L., Cowels A., Hsiao J., Zismann V., et al. , 2006. Expressed sequence tags from loblolly pine embryos reveal similarities with angiosperm embryogenesis. Plant Mol. Biol. 62: 485–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M. S., Law M., Holt C., Stein J. C., Mogue G. D., et al. , 2014. MAKER-P: an annotation pipeline and genome-database management tool for second-generation genome projects. Plant Physiol. 164: 513–524.24306534 [Google Scholar]

- Cavagnaro P. F., Senalik D. A., Yang L., Simon P. W., Harkins T. T., et al. , 2010. Genome-wide characterization of simple sequence repeats in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). BMC Genomics 11: 569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Civáň P., Švec M., Hauptvogel P., 2011. On the coevolution of transposable elements and plant genomes. J. Bot. 10.1155/2011/893546. [Google Scholar]

- Dongen, S., and C. Abreu-Goodger, 2012 Using MCL to extract clusters from networks, pp. 281–295 in Bacterial Molecular Networks, edited by J. Helden, A. Toussaint, and D. Thieffry. Springer, Berlin; Heidelberg, Germany; New York. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert A. J., Pande B., Ersoz E. S., Wright M. H., Rashbrook V. K., et al. , 2009. High-throughput genotyping and mapping of single nucleotide polymorphisms in loblolly pine (Pinus taeda L.). Tree Genet. Genomes 5: 225–234. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert A. J., Bower A. D., Gonzalez-Martinez S. C., Wegrzyn J. L., Coop G., et al. , 2010. Back to nature: ecological genomics of loblolly pine (Pinus taeda, Pinaceae). Mol. Ecol. 19: 3789–3805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert A., Wegrzyn J., Liechty J., Lee J., Cumbie W., et al. , 2013. The evolutionary genetics of the genes underlying phenotypic associations for loblolly pine (Pinus taeda, Pinaceae). Genetics 195: 1353–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C., 2010. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26: 2460–2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C., Myers E. W., 2005. PILER: identification and classification of genomic repeats. Bioinformatics 21: i152–i158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Baidouri M., Panaud O., 2013. Comparative genomic paleontology across plant kingdom reveals the dynamics of TE-driven genome evolution. Genome Biol. Evol. 5: 954–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enright A. J., Van Dongen S., Ouzounis C. A., 2002. An efficient algorithm for large-scale detection of protein families. Nucleic Acids Res. 30: 1575–1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J., 1989. PHYLIP: Phylogeny Inference Package (Version 3.2). Cladistics 5: 164–166. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Pozo N., Canales J., Guerrero-Fernandez D., Villalobos D. P., Diaz-Moreno S. M., et al. , 2011. EuroPineDB: a high-coverage web database for maritime pine transcriptome. BMC Genomics 12: 366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feschotte C., Pritham E. J., 2007. DNA transposons and the evolution of eukaryotic genomes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 41: 331–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanary B. E., Kletetschka G., 2005. Analysis of telomere length and telomerase activity in tree species of various life-spans, and with age in the bristlecone pine Pinus longaeva. Biogerontology 6: 101–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flutre T., Duprat E., Feuillet C., Quesneville H., 2011. Considering transposable element diversification in de novo annotation approaches. PLoS ONE 6: e16526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frech C., Chen N., 2010. Genome-wide comparative gene family classification. PLoS ONE 5: e13409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friesen N., Brandes A., Heslop-Harrison J., 2001. Diversity, origin, and distribution of retrotransposons (gypsy and copia) in conifers. Mol. Biol. Evol. 18: 1176–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel A., Willems M., Mules E. H., Boeke J. D., 1996. Replication infidelity during a single cycle of Ty1 retrotransposition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93: 7767–7771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganal M. W., Lapitan N. L. V., Tanksley S. D., 1991. Macrostructure of the tomato telomeres. Plant Cell 3: 87–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Gil M. R., 2008. Evolutionary aspects of functional and pseudogene members of the phytochrome gene family in Scots pine. J. Mol. Evol. 67: 222–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemayel R., Vinces M. D., Legendre M., Verstrepen K. J., 2010. Variable tandem repeats accelerate evolution of coding and regulatory sequences. Annu. Rev. Genet. 44: 445–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gernandt D. S., Liston A., Pinero D., 2001. Variation in the nrDNA ITS of Pinus subsection Cembroides: implications for molecular systematic studies of pine species complexes. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 21: 449–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodstein D. M., Shu S., Howson R., Neupane R., Hayes R. D., et al. , 2012. Phytozome: a comparative platform for green plant genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 40: D1178–D1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillet-Claude C., Isabel N., Pelgas B., Bousquet J., 2004. The evolutionary implications of knox-I gene duplications in conifers: correlated evidence from phylogeny, gene mapping, and analysis of functional divergence. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21: 2232–2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamberger B., Hall D., Yuen M., Oddy C., Hamberger B., et al. , 2009. Targeted isolation, sequence assembly and characterization of two white spruce (Picea glauca) BAC clones for terpenoid synthase and cytochrome P450 genes involved in conifer defence reveal insights into a conifer genome. BMC Plant Biol. 9: 106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y. J., Wessler S. R., 2010. MITE-Hunter: a program for discovering miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements from genomic sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 38: e199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao D., Yang L., Xiao P., 2011. The first insight into the Taxus genome via fosmid library construction and end sequencing. Mol. Genet. Genomics 285: 197–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hizume M., Shibata F., Maruyama Y., Kondo T., 2001. Cloning of DNA sequences localized on proximal fluorescent chromosome bands by microdissection in Pinus densiflora Sieb. & Zucc. Chromosoma 110: 345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S. W., Li R. Q., Zhang Z. H., Li L., Gu X. F., et al. , 2009. The genome of the cucumber, Cucumis sativus L. Nat. Genet. 41: 1275–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter S., Jones P., Mitchell A., Apweiler R., Attwood T. K., et al. , 2012. InterPro in 2011: new developments in the family and domain prediction database. Nucleic Acids Res. 40(Database issue): D306–D312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain M., Khurana P., Tyagi A. K., Khurana J. P., 2008. Genome-wide analysis of intronless genes in rice and Arabidopsis. Funct. Integr. Genomics 8: 69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffreys A. J., Neil D. L., Neumann R., 1998. Repeat instability at human minisatellites arising from meiotic recombination. EMBO J. 17: 4147–4157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia J. Z., Zhao S. C., Kong X. Y., Li Y. R., Zhao G. Y., et al. , 2013. Aegilops tauschii draft genome sequence reveals a gene repertoire for wheat adaptation. Nature 496: 91–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao Y. N., Wickett N. J., Ayyampalayam S., Chanderbali A. S., Landherr L., et al. , 2011. Ancestral polyploidy in seed plants and angiosperms. Nature 473: 97–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnsen K. H., Wear D., Oren R., Teskey R. O., Sanchez F., et al. , 2001. Carbon sequestration and southern pine forests. J. For. 99: 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kalendar R., Vicient C. M., Peleg O., Anamthawat-Jonsson K., Bolshoy A., et al. , 2004. Large retrotransposon derivatives: abundant, conserved but nonautonomous retroelements of barley and related genomes. Genetics 166: 1437–1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kejnovsky, E., J. Hawkins, and C. Feschotte, 2012 Plant transposable elements: biology and evolution, pp. 17–34 in Plant Genome Diversity, edited by J. F. Wendel, J. Greilhuber, J. Dolezel, and I. J. Leitch. Springer, Berlin; Heidelberg, Germany; New York. [Google Scholar]

- Kent W. J., 2002. BLAT: the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 12: 656–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirst M., Johnson A. F., Baucom C., Ulrich E., Hubbard K., et al. , 2003. Apparent homology of expressed genes from wood-forming tissues of loblolly pine (Pinus taeda L.) with Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100: 7383–7388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohany O., Gentles A. J., Hankus L., Jurka J., 2006. Annotation, submission and screening of repetitive elements in Repbase: RepbaseSubmitter and Censor. BMC Bioinformatics 7: 474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korf I., 2004. Gene finding in novel genomes. BMC Bioinformatics 5: 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovach A., Wegrzyn J. L., Parra G., Holt C., Bruening G. E., et al. , 2010. The Pinus taeda genome is characterized by diverse and highly diverged repetitive sequences. BMC Genomics 11: 420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Bennetzen J. L., 1999. Plant retrotransposons. Annu. Rev. Genet. 33: 479–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumekawa N., Ohmido N., Fukui K., Ohtsubo E., Ohtsubo H., 2001. A new gypsy-type retrotransposon, RIRE7: preferential insertion into the tandem repeat sequence TrsD in pericentromeric heterochromatin regions of rice chromosomes. Mol. Genet. Genomics 265: 480–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitch A. R., Leitch I. J., 2012. Ecological and genetic factors linked to contrasting genome dynamics in seed plants. New Phytol. 194: 629–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., He Y. H., Amasino R., Chen X. M., 2004. siRNAs targeting an intronic transposon in the regulation of natural flowering behavior in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 18: 2873–2878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., Thummasuwan S., Sehgal S. K., Chouvarine P., Peterson D. G., 2011. Characterization of the genome of bald cypress. BMC Genomics 12: 553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz W. W., Sun F., Liang C., Kolychev D., Wang H., et al. , 2006. Water stress-responsive genes in loblolly pine (Pinus taeda) roots identified by analyses of expressed sequence tag libraries. Tree Physiol. 26: 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz W. W., Ayyampalayam S., Bordeaux J. M., Howe G. T., Jermstad K. D., et al. , 2012. Conifer DBMagic: a database housing multiple de novo transcriptome assemblies for 12 diverse conifer species. Tree Genet. Genomes 8: 1477–1485. [Google Scholar]