Dear Editor,

Sideroblastic anemia is a heterogeneous disorder that is characterized by increased serum iron and ferritin levels, high number of hypochromic red blood cells (RBCs), and ineffective erythropoiesis with ringed sideroblasts in the bone marrow (BM) [1]. There are two forms of sideroblastic anemia: inherited and acquired. Acquired sideroblastic anemia usually develops because of alcohol consumption, toxin exposure, substance abuse, and myelodysplastic syndrome-refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts (MDS-RARS). Inherited sideroblastic anemia has a heterogeneous inheritance pattern including X-linked, autosomal, and mitochondrial entities. X-linked sideroblastic anemia (XLSA) is the most common type, constituting about 40% of inherited sideroblastic anemia [2]. Most cases of XLSA result from deficiency of delta-aminolevulinate synthase 2 (ALAS2), an erythroid-specific enzyme involved in the heme biosynthetic pathway. To date, more than 60 different mutations in the ALAS2 gene on the X chromosome of XLSA patients have been described [3]. Although several reports on inherited sideroblastic anemia in Korea have been published [4-6], the underlying genetic change, a well-known point mutation, was confirmed only in one case [4]. Since the morphologic findings of inherited sideroblastic anemia are usually similar to those of neoplastic MDS-RARS, genetic analyses are useful in identifying inherited sideroblastic anemia. Here, we report a novel missense mutation of the ALAS2 gene in a young male patient presenting with severe sideroblastic anemia.

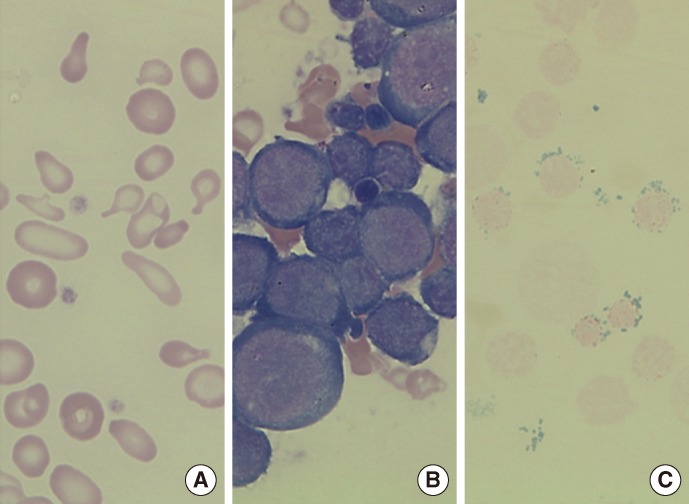

A 27-yr-old man with a medical history of persistent severe anemia (at the age of 15) visited Seoul National University Hospital in November 2012. There was no family history of sideroblastic anemia. The initial complete blood count was as follows: Hb, 4.2 g/dL; Hct, 15.3%; erythrocytes, 3.16×109/L; mean corpuscular volume (MCV), 50.0 fL; mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), 13.2 pg; mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), 26.4 g/dL; red cell distribution width (RDW), 24.9%; reticulocytes, 0.2%; white blood cells, 6.15×106/L; and platelets, 530×106/L. The peripheral blood smear revealed a dimorphic red-cell population including normocytic, normochromic and microcytic, and hypochromic erythrocytes, along with severe anisopoikilocytosis (Fig. 1A). Tests for iron status indicated iron overload, with a serum iron level of 212 µg/dL, ferritin level of 641 ng/mL, and a total iron binding capacity of 249 µg/dL. Chromosome analysis, Hb electrophoresis, and flow cytometry analysis for cluster of differentiation (CD) 55 and CD59 did not indicate any abnormalities. BM study revealed marked erythroid hyperplasia (myeloid:erythroid ratio of 0.3:1) with mild dyserythropoietic changes, including nuclear budding and internuclear bridging (Fig. 1B). The ringed sideroblasts with multiple perinuclear iron granules constituted over 50% of total erythroblasts in the Prussian blue-stained specimens (Fig. 1C). Stored iron in marrow was increased to grade 4, using Gale's histological grading method [7].

Fig. 1.

(A) Peripheral blood smear showing dimorphic red blood cells (RBCs) including microcytic hypochromic RBCs with severe anisopoikilocytosis (Wright-Giemsa stain, ×1,000). (B) Bone marrow (BM) aspirate smear showing marked increase of erythroid precursors (Wright-Giemsa stain, ×1,000). (C) Iron stain of BM aspirate showing many ringed sideroblasts, which accounted for up to 50% of the total erythroid precursors (Prussian blue stain, ×1,000).

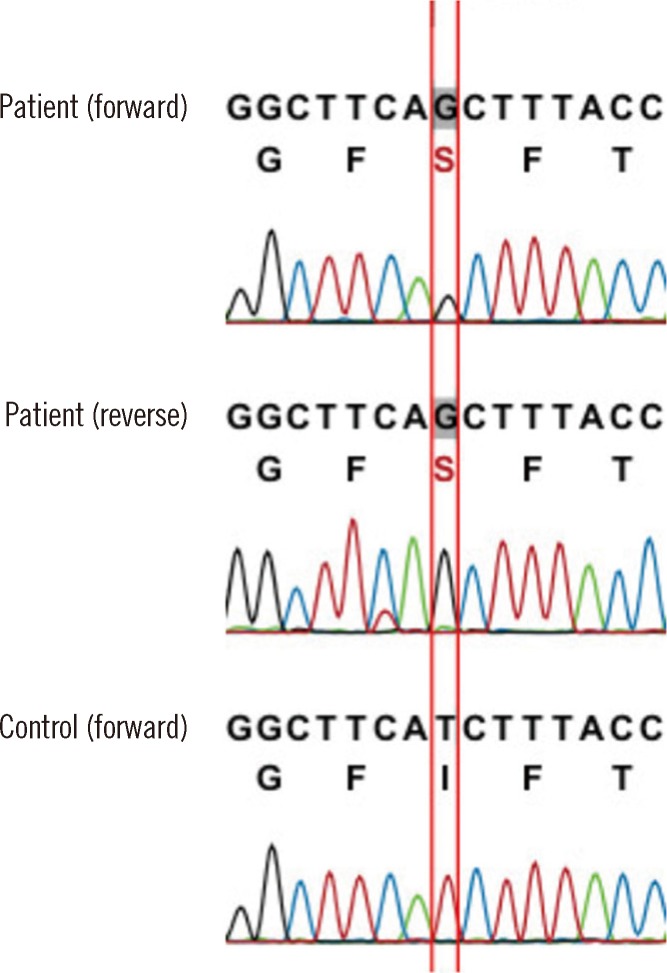

The patient was suspected of having inherited sideroblastic anemia rather than MDS-RARS, considering his young age and the presence of severe microcytic anemia. Therefore, genetic analysis for the ALAS2 gene was performed by using direct sequencing of the patient's genomic DNA, which was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes. PCR and direct sequencing of the ALAS2 gene were performed to amplify the coding and flanking regions from exon 5 to exon 12, as these regions are thought to encode the core functional parts of the enzyme, and most of the known mutations associated with XLSA have been found in these regions [1, 2]. We detected a novel mutation-a substitution of thymine with guanine, in the beginning part of exon 9 (c.1253T>G) (Fig. 2). This mutation leads to a change in the 418th amino acid in the ALAS2 polypeptide from isoleucine to serine (p.Ile418Ser; p.I418S). We used the SIFT (http://sift.jcvi.org/www/SIFT_enst_submit.html), Align GVGD (http://agvgd.iarc.fr/), and Polyphen-2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/) web-based tools to determine the significance of this missense mutation. The results suggest that this substitution, which changes a nonpolar amino acid to a polar amino acid, has a high probability for affecting the function (score 0.00 in SIFT, class C65 in Align GVGD, and score 1.000 in Polyphen-2) of ALAS2, and that the ALAS2 polypeptide sequence is evolutionarily conserved in most eukaryotes. Although the patient did not report a family history of anemia for the patient's brother, mother, and other siblings, the patient was presumed to have XLSA on the basis of the results of mutation analysis.

Fig. 2.

Direct sequencing of the ALAS2 gene showing a hemizygous c.1253T>G (between red lines) missense mutation in exon 9, which results in the conversion of isoleucine to serine at the 418th amino acid (p.I418S).

Oral pyridoxine was prescribed to the patient for 3 months, which dramatically increased Hb levels up to the normal range (Hb, 13.2 g/dL; MCV, 70.7 fL; MCH, 21.8 pg; and RDW, 18.9%) without transfusion. However, microscopic hypochromic features of erythrocytes remained, showing little improvement.

XLSA is the most common inherited form of sideroblastic anemia, followed by the autosomal recessive inheritance pattern. Mutations of the ALAS2 gene lead to a deficiency of ALAS2 in mitochondria in erythropoietic precursors [3]. ALAS2 catalyzes the first step of heme biosynthesis-the condensation of glycine and succinyl-CoA to form delta-aminolevulinic acid in the presence of a pyridoxal 5'-phosphate (PLP; a metabolite of vitamin B6) as a cofactor [8]. XLSA is also referred to as pyridoxine-responsive anemia because pyridoxine supplementation usually improves this form of anemia [1, 9]. The responsiveness to this simple medication enables a differential diagnosis with other microcytic anemia. In addition to XLSA, other genetic causes of several clinically distinctive forms of inherited sideroblastic anemia have been elucidated. Mutations in SLC25A38, ABCB7, GLRX5, PUS1, and SLC19A have been associated with inherited sideroblastic anemia [3]. However, these mutations are less prevalent, and patients with these mutations are not responsive to pyridoxine therapy [2, 3].

Most anemia patients show features of iron overload, including increased ferritin and transferrin saturation in serum as a result of decreased iron utilization. Above all, increased ringed sideroblasts in BM is a hallmark of the disease, which often facilitates its differentiation from MDS-RARS, especially in elderly patients. Although macrocytic anemia and pyridoxine non-responsiveness suggest MDS-RARS, identification of ALAS2 mutations may be required to exclude XLSA because of the shared morphological features in XLSA and MDS-RARS, such as the dyserythropoietic features and presence of ringed sideroblasts. A few reports have described the misdiagnosis of elderly patients with ALAS2 mutations as having RARS or other anemia, with clinical improvement in some of these patients following supplementation of pyridoxine alone [10-12].

The mutation c.1253T>G (p.I418S) found in our case was located in the beginning part of exon 9. Although many point mutations have been found in exon 9 [1, 13], to our knowledge, the site described in this study was not identified previously. The I418S substitution was predicted to generate a mutant protein with altered function that may contribute to the pathogenesis of XLSA. The isoleucine at position 418 and adjacent residues are important for binding of the PLP cofactor, which is crucial for the stability of the enzyme maintaining a conformation optimal for substrate binding and product release, and for the induction of catalytic activity [8, 14]. Moreover, these sites have been conserved throughout evolution in ALAS2 proteins of different species [1]. Thus, I418S disrupts ALAS2 binding with PLP, but the disruption does not seem to be severe because pyridoxine therapy improves anemia. Previous studies found that the substitutions adjacent to I418, such as in R411 or G416, could generate variants underlying the pathogenesis of pyridoxine supplementation-responsive XLSA [1, 13].

In summary, we identified a novel hemizygous c.1253T>G missense mutation in the ALAS2 gene in a 27-yr-old Korean man with a 12-yr history of severe microcytic hypochromic anemia. Several morphologic features of inherited sideroblastic anemia are shared with acquired sideroblastic anemia; however, the different prognoses and treatments, genetic analysis of ALAS2 for inherited sideroblastic anemia can facilitate an accurate diagnosis. Its importance is emphasized in young patients with microcytic hypochromic anemia that show resistance to iron therapy, laboratory findings of iron overload, and inconsistent features with other hemoglobinopathies, even without a family history of anemia.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant of the Korean Health Technology R & D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (A120659).

Footnotes

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

References

- 1.May A, Bishop DF. The molecular biology and pyridoxine responsiveness of X-linked sideroblastic anaemia. Haematologica. 1998;83:56–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Camaschella C. Recent advances in the understanding of inherited sideroblastic anaemia. Br J Haematol. 2008;143:27–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleming MD. Congenital sideroblastic anemias: iron and heme lost in mitochondrial translation. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2011;2011:525–531. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2011.1.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choung HS, Kim HJ, Jung CW, Kim SH. Identification of a hemizygous R170H mutation in the ALAS2 gene in a young male patient with X-linked sideroblastic anemia. Korean J Hematol. 2008;43:118–121. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jun KR, Sohn YH, Park CJ, Jang SS, Chi HS, Seo JJ. A case of hereditary sideroblastic anemia. Korean J Hematol. 2005;40:49–53. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sung JS, Kim KH, Han DG, Kim MJ, Cho YK, Chung HY, et al. Pyridoxine responsive sideroblastic anemia in a boy with mitral valve prolapse. Korean J Pediatr. 2006;49:1223–1226. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gale E, Torrance J, Bothwell T. The quantitative estimation of total iron stores in human bone marrow. J Clin Invest. 1963;42:1076–1082. doi: 10.1172/JCI104793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shoolingin-Jordan PM, Al-Daihan S, Alexeev D, Baxter RL, Bottomley SS, Kahari ID, et al. 5-Aminolevulinic acid synthase: mechanism, mutations and medicine. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1647:361–366. doi: 10.1016/s1570-9639(03)00095-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iolascon A, De Falco L, Beaumont C. Molecular basis of inherited microcytic anemia due to defects in iron acquisition or heme synthesis. Haematologica. 2009;94:395–408. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cazzola M, May A, Bergamaschi G, Cerani P, Rosti V, Bishop DF. Familial-skewed X-chromosome inactivation as a predisposing factor for late-onset X-linked sideroblastic anemia in carrier females. Blood. 2000;96:4363–4365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cotter PD, May A, Fitzsimons EJ, Houston T, Woodcock BE, al-Sabah AI, et al. Late-onset X-linked sideroblastic anemia. Missense mutations in the erythroid delta-aminolevulinate synthase (ALAS2) gene in two pyridoxine-responsive patients initially diagnosed with acquired refractory anemia and ringed sideroblasts. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2090–2096. doi: 10.1172/JCI118258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Furuyama K, Harigae H, Kinoshita C, Shimada T, Miyaoka K, Kanda C, et al. Late-onset X-linked sideroblastic anemia following hemodialysis. Blood. 2003;101:4623–4624. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ducamp S, Kannengiesser C, Touati M, Garçon L, Guerci-Bresler A, Guichard JF, et al. Sideroblastic anemia: molecular analysis of the ALAS2 gene in a series of 29 probands and functional studies of 10 missense mutations. Hum Mutat. 2011;32:590–597. doi: 10.1002/humu.21455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Astner I, Schulze JO, van den Heuvel J, Jahn D, Schubert WD, Heinz DW. Crystal structure of 5-aminolevulinate synthase, the first enzyme of heme biosynthesis, and its link to XLSA in humans. EMBO J. 2005;24:3166–3177. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]