Dear editor,

Synchronous primary lung cancer occurs in only 0.5% of patients with lung cancer, and coexistence of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) has been reported in a very small fraction of lung cancer cases [1, 2]. In NSCLC, malignant cells are generally arranged in three-dimensional clusters and have eccentrically placed round to oval nuclei with prominent nucleoli. The cytoplasm may contain single to many vacuoles with diffuse and strong positivity on periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) cytochemical staining. Most NSCLC cells show positive cytoplasmic immunoreactivity for cytokeratin (CK) 7 but negative immunoreactivity for CK20. In SCLC, the small tumor cells have an extremely high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio and show nuclear molding with positive immunocytochemical staining for CD56. The nuclear contours are often "squeezed" in appearance in order to accommodate the contours of the adjacent nuclei (a back-to-back appearance) [3]. To the best of our knowledge, coexistence of residual NSCLC cells and newly developed SCLC cells in ascitic fluid after chemotherapy for previously diagnosed NSCLC has not been reported. Here, we report a case of residual NSCLC cells coexisting with newly developed SCLC cells in the ascitic fluid of a patient who had received chemotherapy for previously diagnosed NSCLC.

A 54-yr-old man had been admitted to our institution in July 2013 for examination of abdominal distension that had developed 1 month previously. He was diagnosed as having NSCLC (adenocarcinoma of the lung) 5 yr previously and had subsequently undergone right upper lobe (RUL) lobectomy. Pathological examination of the surgical specimen had shown involvement of moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma up to the visceral pleura, without any regional lymph node metastasis or neoplastic cells of other origins, and pleural fluid cytology showed the presence of adenocarcinoma (NSCLC) only. The initial stage of NSCLC was assessed as T2aN0M0 (stage IB) at diagnosis. After RUL lobectomy, the patient was routinely followed up without adjuvant chemotherapy for 2 yr.

Three years before the most recent presentation, chest computed tomography (CT) showed newly developed NSCLC lesions in the right middle and lower lobes. The patient was diagnosed as having recurrent NSCLC, and chemotherapy with intravenous infusion of gemcitabine (1,000 mg/day) and cisplatin (120 mg/day) for 3 months was administered. After chemotherapy, the newly developed NSCLC lesions initially decreased in size. However, after 2 yr of chemotherapy, multiple nodules developed in the right hemithorax, which increased in size over time. Dyspnea due to an increased amount of pleural effusion was also observed. Chest CT showed pleural thickening and an increased amount of pleural fluid, with evidence of regional metastasis to the right hemithorax. On the basis of these findings, progressive disease (PD) was ascertained. Mutational analysis showed the presence of EGFR gene mutation (a deletion occurring in the 745th codon of exon 19). The patient was treated with gefitinib (250 mg/day) for 1 yr.

Initial response to gefitinib was favorable, as evidenced by a gradual decrease in pleural effusion and the size of metastatic nodules in the lung for 6 months. Pleural and ascitic fluid analyses showed no evidence of metastasis in both cavities on follow-up examination. However, follow-up chest CT performed 6 months previously showed aggravation of malignant pleural effusion and an increase in the lymph node size in the left gastric and pericaval area, with thickening of the pericardium, suggesting tumor invasion to the left hemithorax and pericardium. The patient's condition was classified as PD again, and abdominal distension developed gradually over 6 months, despite gefitinib treatment.

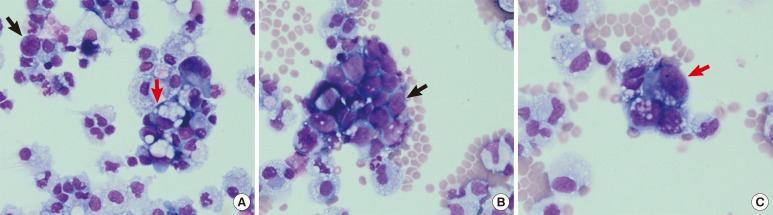

Ascitic fluid analysis performed at the most recent presentation showed 2 types of neoplastic cells differing in origin, at a frequency of 18% (Fig. 1A). The first type of identified cells were clusters of small- to medium-sized neoplastic cells with a back-to-back appearance (Fig. 1B), and the second type of cells were large neoplastic cells with mucinous contents in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Wright staining of ascitic fluid cytospin slides. Two types of neoplastic cells were detected (A, 400×, small-cell lung cancer [SCLC] cells pointed by black arrow and non-small cell lung cancer [NSCLC] cells by red arrow) at a frequency of 18%. Small-to medium-sized SCLC cells appeared as clusters of tumor cells with a back-to-back appearance (B, 400×, black arrow), and the second type of cells, large NSCLC cells, showed mucinous contents in the cytoplasm (C, 400×, red arrow).

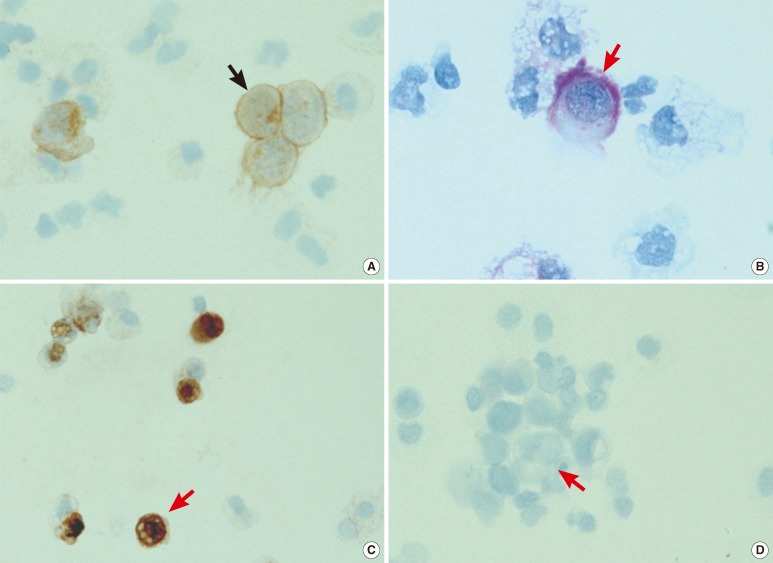

Subsequently, cytochemical staining with PAS and immunocytochemical staining for CD56 (antibody diluted to 1:100; Zymed, San Francisco, CA, USA), CK7 (antibody diluted to 1:200; Dako, Cambridge, UK), and CK20 (antibody diluted to 1:100; Dako) were performed on cytospin slides to confirm the presence of neoplastic cells of two different origins. The small- to medium-sized neoplastic cells with a back-to-back appearance showed membrane positivity for CD56 on immunocytochemical staining (Fig. 2A). The large neoplastic cells with mucinous contents in the cytoplasm showed cytoplasmic positivity with PAS cytochemical staining (Fig. 2B) as well as CK7 positivity on immunocytochemical staining (Fig. 2C), but CK20 negativity on immunocytochemical staining (Fig. 2D). The small- to medium-sized neoplastic cells with a back-to-back appearance were diagnosed as SCLC, and the large neoplastic cells with mucinous contents in the cytoplasm were diagnosed as NSCLC (adenocarcinoma). The patient was diagnosed as having peritoneal metastasis of both SCLC and residual NSCLC. Five days after diagnosis, the patient died of impending hyperkalemia and azotemia.

Fig. 2.

Cytochemical and immunocytochemical staining results of the two types of neoplastic cells detected in the ascitic fluid. The small-to medium-sized small-cell lung cancer cells (black arrow) showed membrane positivity for CD56 on immunocytochemical staining (A, 400×). The large non-small cell lung cancer cells (red arrow) showed cytoplasmic positivity with periodic acid-Schiff cytochemical staining (B, 1,000×) as well as cytokeratin 7 positivity on immunocytochemical staining (C, 400×) but cytokeratin 20 negativity on immunocytochemical staining (D, 400×).

Factors contributing to the development of synchronous primary lung cancer have not been investigated adequately because of its rarity. A previous study reported a case of synchronous primary lung cancer (SCLC and NSCLC) with strong positivity for p53 on immunohistochemical staining in a patient with a history of tobacco use for 40 yr [2]. The authors hypothesized that synchronous primary lung cancer may be associated with long-term tobacco use, which could independently lead to mutations in the p53 and K-ras genes [2]. However, in our case, the patient had a history of limited tobacco use (0.5 packs for 8 yr) and no K-ras mutation, as demonstrated by direct sequencing. Although the p53 mutation status was not investigated in our case, the clinical and molecular features partly contradict the hypothesis propounded in the previous report [2]. Factors associated with the development of synchronous primary lung cancer need to be confirmed in future studies.

In conclusion, we report a case of residual NSCLC cells coexisting with newly developed SCLC cells in the ascitic fluid of a patient after chemotherapy for previously diagnosed NSCLC.

Footnotes

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

References

- 1.Hiraki A, Ueoka H, Yoshino T, Chikamori K, Onishi K, Kiura K, et al. Synchronous primary lung cancer presenting with small cell carcinoma and non-small cell carcinoma: diagnosis and treatment. Oncol Rep. 1999;6:75–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin CC, Chian CF, Perng WC, Cheng MF. Synchronous double primary lung cancers via p53 pathway induced by heavy smoking. Ann Saudi Med. 2010;30:236–238. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.62837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atkinson BF, editor. Atlas of diagnostic cytopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2004. pp. 291–292. [Google Scholar]