Abstract

Cholinergic modulation of prefrontal cortex is essential for attention. In essence, it focuses the mind on relevant, transient stimuli in support of goal-directed behavior. The excitation of prefrontal layer VI neurons through nicotinic acetylcholine receptors optimizes local and top-down control of attention. Layer VI of prefrontal cortex is the origin of a dense feedback projection to the thalamus and is one of only a handful of brain regions that express the α5 nicotinic receptor subunit, encoded by the gene chrna5. This accessory nicotinic receptor subunit alters the properties of high-affinity nicotinic receptors in layer VI pyramidal neurons in both development and adulthood. Studies investigating the consequences of genetic deletion of α5, as well as other disruptions to nicotinic receptors, find attention deficits together with altered cholinergic excitation of layer VI neurons and aberrant neuronal morphology. Nicotinic receptors in prefrontal layer VI neurons play an essential role in focusing attention under challenging circumstances. In this regard, they do not act in isolation, but rather in concert with cholinergic receptors in other parts of prefrontal circuitry. This review urges an intensification of focus on the cellular mechanisms and plasticity of prefrontal attention circuitry. Disruptions in attention are one of the greatest contributing factors to disease burden in psychiatric and neurological disorders, and enhancing attention may require different approaches in the normal and disordered prefrontal cortex.

Keywords: Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, Attention, chrna5, Medial prefrontal cortex, Electrophysiology

Attention has been eloquently described as the ‘searchlight’ that focuses on relevant information in the midst of distraction in order to support goal-directed behavior [1]. In particular, it plays a pivotal role in mediating the executive functions of the prefrontal cortex [2, 3], a site of sensorimotor and emotional integration that is uniquely positioned to execute top-down control permissive to the orchestration of complex, flexible, and purposeful behavior such as problem solving, planning, and decision making [1, 3–5]. Given its intimate relationship to awareness, attention has also been qualified as the gateway to consciousness [2, 3, 6, 7].

Acetylcholine has long been known to play a role in cognition [8–10]. Non-specific lesions of the cholinergic neurons of the basal forebrain first suggested a more specific involvement of acetylcholine in attention [11–16], and it subsequently became clear that cholinergic projections to the prefrontal cortex are especially important in this regard [17, 18]. The importance of cholinergic modulation of prefrontal cortex can be seen in the detrimental effects for attention of specific lesions to its cholinergic projections. These projections, as shown in the schematic in Fig. 1, include a dense cholinergic innervation from the basal forebrain, principally from the basal nucleus and parts of the diagonal band, but also from the magnocellular preoptic nucleus and substantia innominata [19–26]. Intrabasalis infusions of the cholinergic immunotoxin 192 IgG-saporin lead to the loss of cortical cholinergic afferents, reduced acetylcholine efflux in the prefrontal cortex, and significant impairments on attention tasks [27, 28]. Bilateral infusions of 192 IgG saporin in medial prefrontal cortex are equally detrimental and demonstrate that its deafferentation of cholinergic projections is sufficient to produce attentional impairments [17, 18, 29].

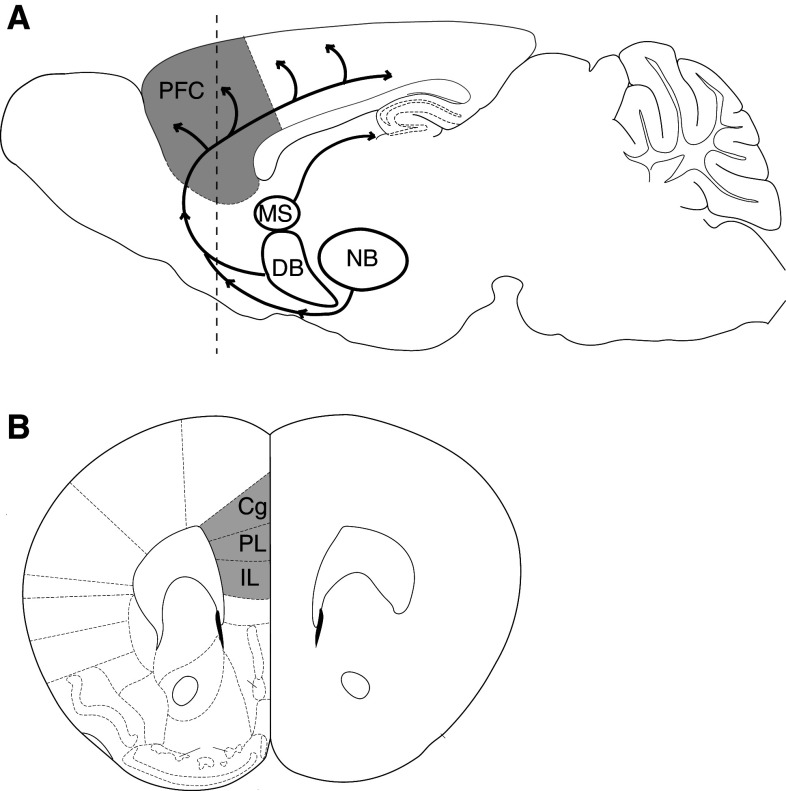

Fig. 1.

a The medial prefrontal cortex shown in gray receives cholinergic innervation from the basal forebrain. Figure adapted from Woolf [25] and Paxinos and Franklin [277] and is based on findings from Rye et al., Luiten et al., and Gaykema et al. [23, 160, 278]. The dashed line indicates the approximate location of the coronal section shown below. b Coronal brain section showing the subregions of rodent medial prefrontal cortex (in gray). Cg cingulate cortex, DB diagonal band, IL infralimbic cortex, MS medial septal nucleus, NB nucleus basalis, PFC prefrontal cortex, PL prelimbic cortex

The importance of prefrontal cholinergic modulation was further suggested by microdialysis studies showing robust acetylcholine efflux within the prefrontal cortex during the performance of attention tasks [30–32], which reflects both attentional effort [33, 34] and behavioral context [35]. Moreover, the development of choline-sensitive microelectrodes, which offer greater temporal resolution than microdialysis probes, has further revealed that acetylcholine release in the prefrontal cortex increases rapidly and transiently—on the timescale of seconds to minutes—during the performance of attention tasks [29] where, as we will emphasize in this review, it can exert profound effects on corticothalamic neurons via the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors [36–38].

Layer VI corticothalamic neurons of the prefrontal cortex play a central role in attention

Acetylcholine optimizes prefrontal cortical circuitry for top-down control [39–41]. Corticothalamic neurons, which constitute a large proportion of layer VI pyramidal cells [42], are uniquely positioned to exert these top-down influences and are robustly excited by acetylcholine [36]. These neurons integrate highly processed information from layer V pyramidal cells, from layer VI cortico-cortical neurons, and from direct thalamic inputs [42]. In turn, they exert powerful feedback influences on the thalamus [43–46]. While not all neurons in layer VI are corticothalamic, it is important to note that there are ten times more corticothalamic feedback projections than there are thalamocortical afferents [47], such that cholinergic modulation of these neurons will exert important influences on the circuits of attention.

Layer VI corticothalamic neurons constitute the major source of excitatory afferents to the thalamus [48], where they affect both the inhibitory reticular thalamic neurons [49] and the excitatory thalamocortical projection neurons [50]. During the tonic firing of wakefulness, the overall effect of this corticothalamic feedback is to focus thalamic and thalamocortical excitation [51], in part by modulating the sensitivity of thalamic neurons to incoming sensory stimuli [48, 52–54]. Prefronto-thalamic connectivity is further privileged in its modulation of attention due to its relationship with the midline and intralaminar thalamic nuclei that have long been implicated in awareness and attention [54–58].

The high percentage of layer VI neurons responding to acetylcholine [59] suggests that corticothalamic neurons are not the exclusive population of neurons subject to cholinergic modulation. This point should be emphasized since recent work has shown that layer VI neurons as a class exert powerful gain control over all the other cortical layers [60]. Cholinergic innervation is present in all layers of the prefrontal cortex [24, 26], but appears biased toward activation of the deepest layers [61]. Clear labeling of cholinergic fibers is observed in the deep cortical layers [24, 26], as demonstrated with immunostaining for choline-acetyltransferase (ChAT), the enzyme that catalyzes the synthesis of acetylcholine from acetyl-CoA and choline. Furthermore, anterograde labeling of ChAT positive cholinergic afferents from the basal forebrain indicate preferential projection to deep layers V/VI [62]. The apical dendrites from a large fraction of layer VI neurons extend all the way to the pial surface [63], where they may also be stimulated by cholinergic projections (and possibly also by cholinergic interneurons [64]) in superficial layers II/III [26, 64].

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and their modulation of prefrontal layer VI neurons

The neurotransmitter acetylcholine acts on two classes of receptors—the ionotropic nicotinic receptors, which are the main focus of this review, and the metabotropic muscarinic acetylcholine receptors, which are G-protein coupled. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors are pentameric ligand-gated cation channels [65, 66], permeable to Na+, K+, and Ca2+ ions [65, 67]. Two families of subunits can contribute to the pentameric structure necessary for functional nicotinic receptors: the α subunits (α2–α10) and the β subunits (β2–β4) [65, 66, 68]. They are arranged in a pinwheel around a central pore, assembled either as α-containing homomers or α/β heteromers. Nicotinic receptors are widely expressed in the central nervous system, and subunit composition differs from one region to the next [65, 66]. The subunit composition and stoichiometry of nicotinic receptors influence their functional properties, with important implications for nicotinic signaling [37, 69–72].

The most widely expressed nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the brain are the α4β2-containing receptors (α4β2*) [65, 73–75], which are prominently expressed throughout cortex [76–79]. The homomeric α7 nicotinic receptors are also expressed in cortex, although only weak labeling has been documented in cortical layer VI [80]. Interestingly, while the α4, α5, α7, and β2 nicotinic receptor subunits show similar expression patterns in rodent and primate brain [81], there are some species differences in the expression of nicotinic receptors with potential implications for cholinergic modulation of attention circuitry. For example, the α2 nicotinic subunit is only widely expressed in primate brain [81], although it is not enriched in layer VI.

The α4β2* receptors have high affinity for nicotinic agonists (including acetylcholine and nicotine) and desensitize slowly, on the timescale of seconds [65, 82–84]. As illustrated in the schematic in Fig. 2, the α4β2* nicotinic receptors can assume different stoichiometries, including (α4)2(β2)3 and (α4)3(β2)2. In the relatively rare brain regions that express the accessory α5 nicotinic subunit, such as layer VI of prefrontal cortex [86], these receptors can also incorporate the accessory α5 subunit to form (α4)2(β2)2(α5) receptors (α4α5β2) [65, 66, 85–88]. The accessory α5 subunits cannot form functional channels by themselves, since they do not contribute to the acetylcholine binding site and thus require co-assembly with other α and β subunits [65, 79]. However, inclusion of α5 can alter α4β2* nicotinic receptor properties substantially [71, 87, 88]: it can enhance receptor assembly and expression [87, 89], modulate receptor sensitivity to acetylcholine [37, 65, 69, 88, 90, 91], increase Ca2+ permeability [88], and confer sensitivity to allosteric modulation by galanthamine [36, 88].

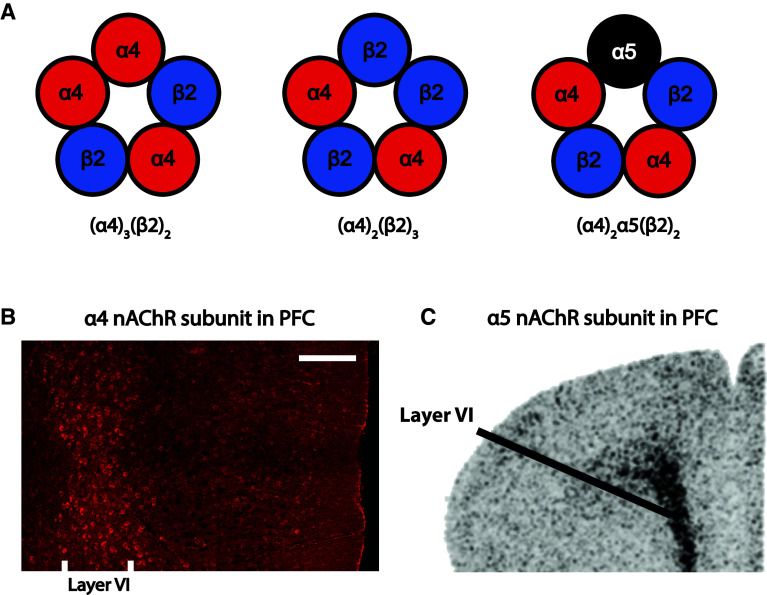

Fig. 2.

Subunit composition and layout of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits in layer VI of medial prefrontal cortex. a Schematics showing three possible compositions of α4β2* nicotinic receptors within layer VI neurons of medial prefrontal cortex. Figure adapted from McKay et al. [279]. b Photomicrograph of mouse medial prefrontal cortex immunostained for YFP-tagged nicotinic acetylcholine receptor α4 subunits, putatively expressed in α4β2*-containing cells as shown at lower resolution by Marks and colleagues [93]. White matter on the right and the medial pial surface is on the left; adapted from Alves et al. [92]. Scale bar 200 μm. c In situ hybridization showing a dense band of α5 nicotinic subunit mRNA expression in layer VI of the medial prefrontal cortex; adapted from Wada et al. [86]

Immunohistochemistry for YFP-tagged nicotinic α4 subunits in a knockin mouse suggests that high-affinity nicotinic receptors are densely expressed in layer VI of prefrontal cortex [92], where the accessory α5 subunit is also prominently expressed [86, 93–95]. Interestingly, while only one-fifth of all α4β2* nicotinic receptors in the brain are estimated to contain the α5 accessory subunit [65, 89, 96], prefrontal layer VI nicotinic receptors appear to incorporate α5 to a disproportionately large extent [37]. Indeed, functional concentration–response analyses of prefrontal corticothalamic neurons from WT and α5 knockout mice (α5−/−) suggest that the vast majority of α4β2* nicotinic receptors of its layer VI neurons are affected by this subunit [37]. As we will see, this unique expression pattern has ramifications for attentional signaling and behavior [37].

During the performance of attention tasks, brief transients of acetylcholine are released in medial prefrontal cortex [97, 98]. Population calcium imaging in slices of prefrontal cortex has demonstrated that nicotinic receptor stimulation by acetylcholine predominantly activates neurons within the deep cortical layers V/VI [61]. At the cellular level, acetylcholine elicits robust excitatory responses in the layer VI corticothalamic neurons of the medial prefrontal cortex that appear to be directly mediated by stimulation of somatodendritic postsynaptic α4α5β2 nicotinic receptors [36, 37, 59]. Acetylcholine binding to the nicotinic receptor leads to rapid conformational changes that result in channel opening and the flow of Na+, K+, and Ca2+ cations through the pore [65, 66, 83]. Nicotinic receptors rectify at more depolarized membrane potential [99, 100], such that acetylcholine likely exerts more profound effects near the resting membrane potential, where the effect of nicotinic stimulation is excitatory and results in depolarization. When sufficiently large, this membrane depolarization can lead to the generation of action potentials. Acetylcholine depolarizes the vast majority of layer VI pyramidal cells in this way [36], but these excitatory nicotinic responses are completely eliminated in β2−/− mice [38, 59], which lack functional α4β2* nicotinic receptors, and are significantly reduced in α5−/− mice [59].

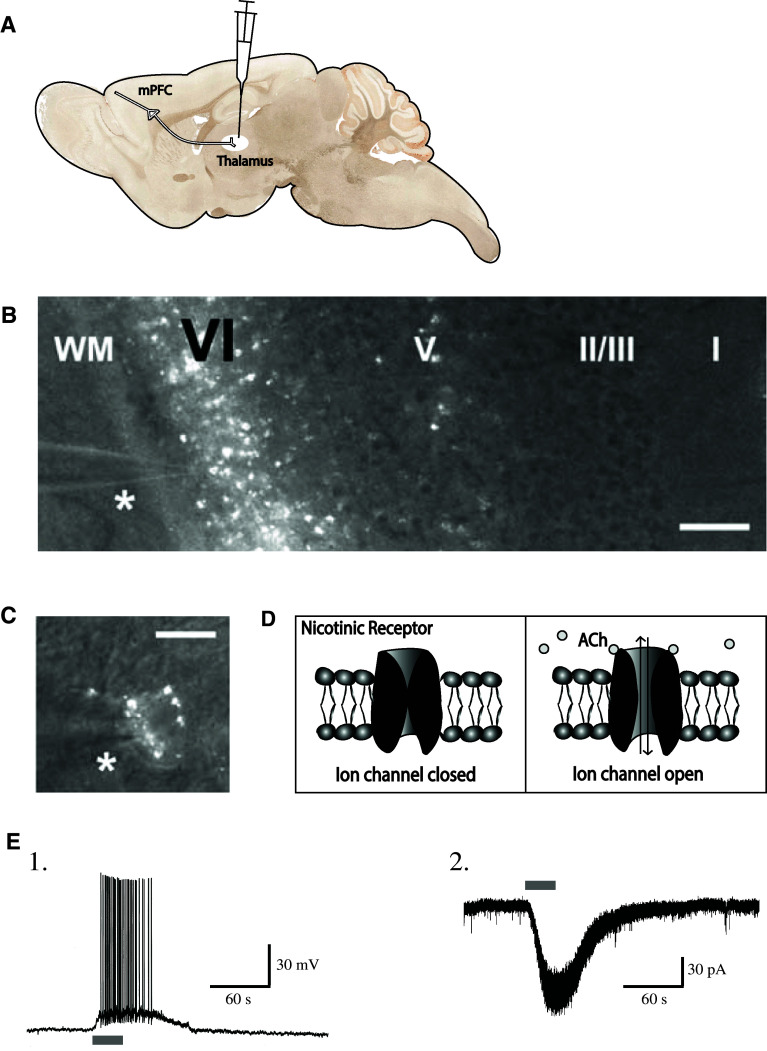

The nicotinic responses that result from the current carried by the flow of Na+, K+, and Ca2+ ions through the nicotinic receptor pore can be examined electrophysiologically in voltage clamp (where the membrane potential can be held constant experimentally so as to allow the measurement of the nicotinic current) or in current clamp (where the membrane potential is allowed to fluctuate and the injected current, or lack thereof, is held constant). Figure 3 illustrates the robust excitatory effects of nicotinic stimulation that were recorded in retrogradely labeled corticothalamic neurons in slices of prefrontal cortex [36]. Since corticothalamic neurons can also be distinguished from cortico-cortical cells based on electrophysiological properties [101, 102], Kassam et al. [36] were further able to establish that nicotinic stimulation exerts more profound excitation of cortico-thalamic than cortico-cortical neurons of layer VI prefrontal cortex.

Fig. 3.

Acetylcholine (ACh) excites labeled corticothalamic neurons in layer VI of medial prefrontal cortex. a Retrograde labeling of corticothalamic neurons through in vivo stereotaxic surgery to inject rhodamine microspheres into the medial dorsal thalamus. b Prominent retrograde labeling of layer VI neurons in a coronal prefrontal brain slice. The asterisk marks the location of a patch pipette for electrophysiologcal recordings. Scale bar 240 μm. Figure adapted from Kassam et al. [36]. c A high-magnification view of a labeled pyramidal cell body. Scale bar 20 μm. Figure adapted from Kassam et al. [36]. d Schematic showing the closed and open states of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. e A retrograde-labeled corticothalamic neuron in layer VI of medial prefrontal cortex responds to acetylcholine in (1) current clamp and (2) voltage clamp. Figure adapted from Kassam et al. [36]

The excitatory nicotinic responses of layer VI pyramidal neurons are directly mediated by postsynaptic somatodendritic receptors since currents are resistant to blockade of synaptic transmission by the Na+ channel antagonist tetrodotoxin and to pharmacological inhibition of ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate receptors [36]. Pharmacologically, these nicotinic currents are suppressed by the α4β2* competitive antagonist DHβE, insensitive to the α7 antagonist MLA and potentiated by the α5 allosteric modulator galanthamine [36, 88]. These findings are consistent with α4α5β2 nicotinic receptor involvement [36]. Most convincing, however, is the demonstration that nicotinic excitation of layer VI pyramidal cells is substantially reduced in mice in which the α5 subunit has been genetically deleted (α5−/−) [37]. Together, these findings highlight that the relatively rare α5 subunit plays an important role in mediating optimal cholinergic excitation of layer VI neurons of the prefrontal cortex, where it is densely expressed and incorporated into α4β2* nicotinic receptors.

Nicotinic receptors and attentional performance

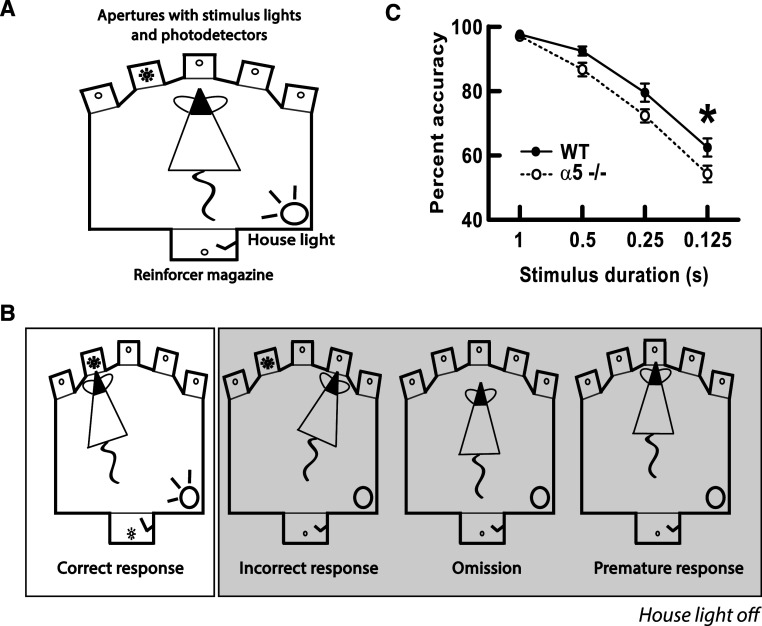

At the behavioral level, the α5 subunit is required for normal attention performance under challenging conditions [37]. The five-choice serial reaction time task (5-CSRTT) is a commonly used attention task that involves sustained and divided attention [103]. Briefly, the animal is placed in an operant chamber, illustrated in Fig. 4. A light stimulus, whose duration can be varied to alter the difficulty of the attention task, is randomly flashed in one of five apertures. The animal is required to attend to, and subsequently accurately recall, the location of this stimulus within a fixed time period. Attention performance is assessed by correct identification of the location of the stimulus by nose poke. This task measures various aspects of attentional control, including accuracy (correct responses), omissions (lack of response, reflects inattentiveness), perseveration (repeated responses at the same location, reflects lack of flexibility), and premature responses (responding before the end of the inter-trial interval, reflects impulsivity). The α5−/− mice show deficits in accuracy on the 5-CSRTT when stimulus duration is brief, a condition that requires greater attentional demand, but perform normally under baseline training conditions, when stimulus duration is longer. Interestingly, equivalent deficits in attention performance in humans are highly disruptive to cognitive function [104–107]. Mice lacking the β2 subunit (β2−/−) also show significant impairments on the 5-CSRTT, and these deficits can be rescued by lentiviral vector-mediated re-expression of β2-containing nicotinic receptors in the prefrontal cortex [38]. The 5-CSRTT studies in α5−/− and β2−/− mice employed different training and testing approaches, which may explain subtle differences in the nature of the attention deficit observed [37, 38].

Fig. 4.

Under challenging conditions, mice lacking the nicotinic α5 subunit (α5−/−) respond with decreased accuracy relative to wild-type (WT) mice in the 5-choice serial reaction time task (5-CSRTT). a Schematic of the operant chamber for the 5-CSRTT. b Four typical responses of mice performing the 5-CSRTT. From left to right: the correct response, the incorrect response, an omission, and a premature response. Figure adapted from Dalley et al. [280]. c Nicotinic receptor α5−/− mice perform significantly worse than wild-type controls in the 5-CSRTT when stimulus duration is brief. Figure adapted from Bailey et al. [37]

Compensatory plasticity of cholinergic responses in prefrontal layer VI neurons

The question arises whether the differences in attention performance observed in α5−/− mice result completely from the impaired nicotinic stimulation of α4α5β2-containing nicotinic receptors within corticothalamic circuits of adult prefrontal cortex or whether the loss of this nicotinic stimulation leads to functional or structural alterations of attention circuitry. It is conceivable that plasticity in the cholinergic system might ameliorate attention deficits that might otherwise be more severe; for example, allowing α5−/− mice to perform at near-normal levels of accuracy when longer stimulus durations are used in the 5-CSRTT [37].

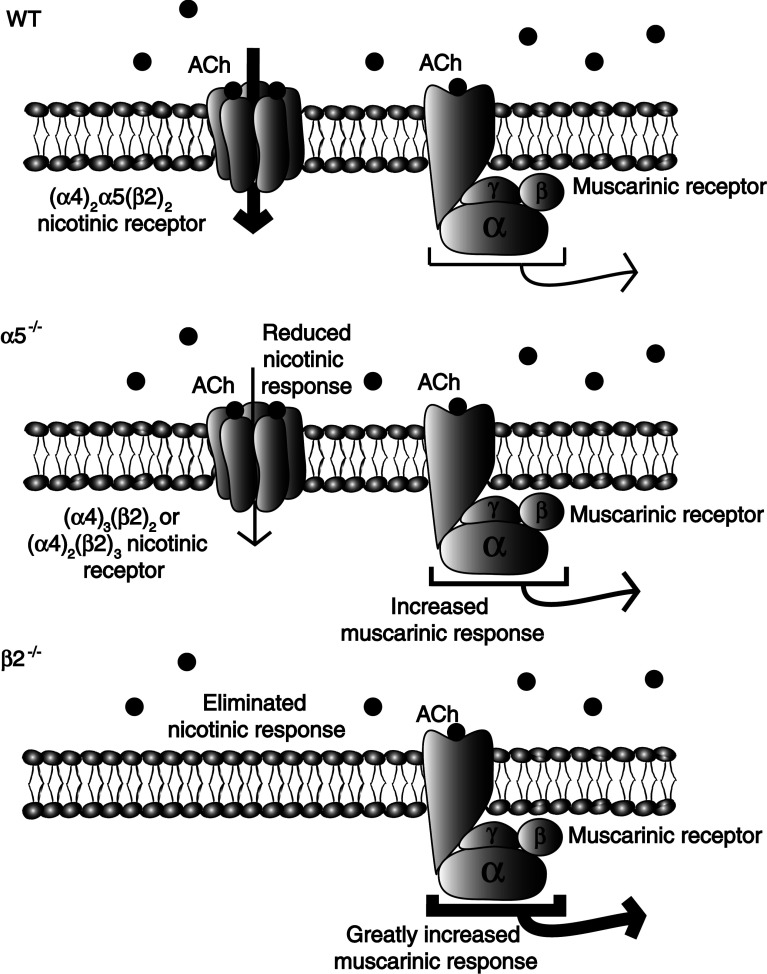

We have observed that cholinergic excitation of the layer VI pyramidal cells primarily involves nicotinic receptors in wild-type mice [59]; however, genetic deletion of the nicotinic α5 or β2 subunits (α5−/− and β2−/−, respectively) leads to the compensatory upregulation of muscarinic acetylcholine receptor excitation [59]. These G-protein coupled receptors couple to second messenger cascades and exert slower excitatory actions, significantly changing the mechanisms and timing of the cholinergic response in these layer VI neurons [59]. A schematic of this compensatory plasticity is shown in Fig. 5; it appears to affect neurons from β2−/− mice to a greater degree than those from α5−/− mice [59]. This unusual plasticity of layer VI cholinergic responsiveness indicates that the attention impairments associated with disruption of nicotinic signaling are more complex than originally anticipated. It is unclear at what stage of maturation this plasticity occurs and whether it can be reversed given sufficient time after adult rescue of the missing nicotinic receptor subunits [38].

Fig. 5.

Plasticity between nicotinic and muscarinic acetylcholine (ACh) receptors in layer VI neurons of medial prefrontal cortex. Typical responses in layer VI pyramidal neurons are highly driven by nicotinic receptors, whereas muscarinic effects are less prominent. In knockout mice with decreased nicotinic receptor function, muscarinic responses are enhanced. This compensatory upregulation in muscarinic receptor function is apparent in α5−/− mice and very pronounced in β2−/− mice. Figure summarizing results from Tian et al. [59]

Nicotinic receptor α5 subunit and morphological maturation of prefrontal layer VI neurons

The maturation of executive function and attention requires the normal development of prefrontal cortex [108–110], and developmental lesions of the cholinergic system disrupt neuronal morphology and cortical circuitry [111–114]. Cortical nicotinic acetylcholine receptors play an important role in the development of attention circuitry [36, 63, 115], and aberrations in cortical nicotinic binding are reported to occur in many neurodevelopmental disorders, including autism [116, 117], epilepsy [118], and schizophrenia [119, 120].

Cholinergic innervation of the prefrontal cortex is well developed by the third week of postnatal life in rodents [121, 122], a time period equivalent to the perinatal period in humans [123, 124]. Dense ChAT immunostaining can be seen in the frontal cortex at this time [122], and high levels of α4β2* nicotinic binding are observed in prefrontal layer VI [125]. Furthermore, peak mRNA levels for the α5 subunit are seen in layer VI during the first 2–3 weeks of postnatal development [95]. By contrast, cortical mRNA levels for the α4 and β2 subunits show a somewhat different pattern with a peak at birth and a slight decline before maintaining relatively constant expression across postnatal development [126, 127].

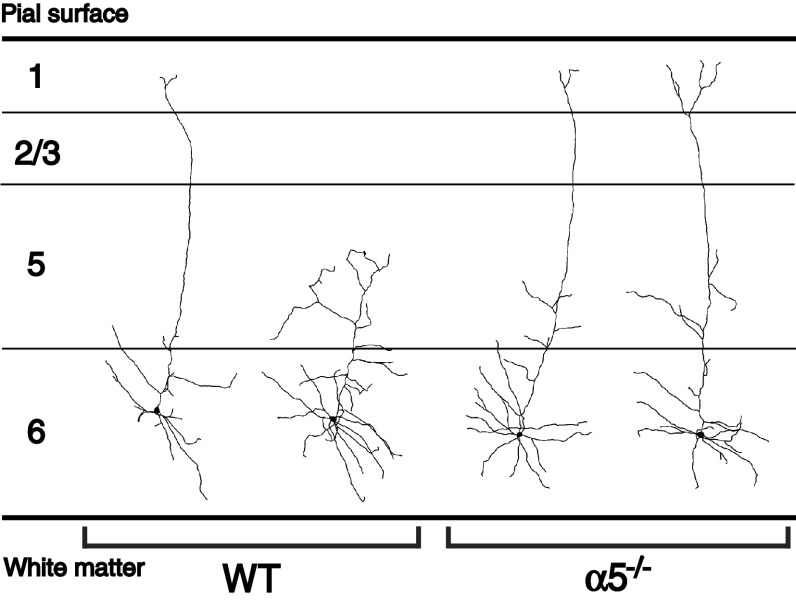

Developmental differences in nicotinic excitation and dendritic morphology coincide temporally with changes in α5 expression. The excitatory nicotinic currents of layer VI neurons exhibit a developmental profile, peaking within the first postnatal month [36]. Nicotinic stimulation can influence neuronal morphology and spur neurite retraction [128, 129], and in the first morphological analysis of these cells, Bailey et al. [63] showed that key developmental changes in neuronal complexity appear to be initiated within this critical time period. Specifically, there appears to be a developmental retraction of the apical dendrites of layer VI prefrontal cortex: whereas almost all the apical dendrites of layer VI pyramidal neurons extend to the pial surface in young mice at postnatal week 3, half of them terminate in the mid-layers by adulthood [63]. As illustrated in Fig. 6, these maturational changes in the dendritic morphology of layer VI neurons are absent in the α5−/− mice, without any further differences in overall cortical morphology [63]. Furthermore, layer VI neurons of α5−/− mice show negligible developmental changes in nicotinic excitation [63]. Thus, the α5 subunit appears to be essential for the normal maturation of corticothalamic circuitry and drives developmental differences in layer VI excitation and morphology.

Fig. 6.

The morphology of layer VI neurons in medial prefrontal cortex differs between wild-type and α5−/− mice. In adult wild-type mice, there is a roughly equal distribution of layer VI pyramidal neurons that have long apical dendrites that terminate at the pial surface and those that have short apical dendrites that terminate within the mid-layers of the medial prefrontal cortex. In contrast, layer VI neurons of α5−/− mice show a preponderance of neurons with long apical dendrites. In this sense, it could be said the layer VI neurons of α5−/− mice retain a developmental phenotype in the pattern of their apical dendritic morphology. In young mice of both genotypes, layer VI neurons have only long apical dendrites. Figure adapted from Bailey et al. [63]. Of note, these morphological changes can be recapitulated in wild-type mice by chronic in vivo nicotine treatment during development [281], likely mediated through desensitization of nicotinic receptors [281]

In summary, there are extensive differences between WT and α5−/− mice in development and adulthood. These differences are relevant to the deficits in attention performance seen in α5−/− mice in adulthood and are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Categories of differences between WT and α5−/− mice

| Effects | WT | α5−/− |

|---|---|---|

| Neuropharmacology in layer VI pyramidal cells [37, 59, 63] | ||

| ACh-elicited nicotinic receptor currents (1 mM) | 40 ± 5 pA | 14 ± 1 pA* |

| Nicotine-elicited nicotinic receptor currents (300 nM) | 16 ± 2 pA | 6 ± 1 pA* |

| Desensitization (% decrease) of ACh response after nicotine | 36 ± 4 % | 73 ± 4 %* |

| ACh-elicited muscarinic depolarization from rest | 2.9 ± 0.5 mV | 6.5 ± 1.3 mV* |

| ACh-elicited muscarinic increase in spiking frequency in excited state | 309 ± 23 % | 462 ± 65 %* |

| Developmental changes in ACh-induced currents | Peak in young mice | No change* |

| Dendritic morphology of layer VI pyramidal cells [63] | ||

| Young mice: % apical dendrites extending to the pial surface | 82 % | 92 % |

| Adult mice: % apical dendrites extending to the pial surface | 45 % | 92 %* |

| Attention behavior [37] | ||

| Performance accuracy on non-demanding attention tasks | 98 ± 1 % | 97 ± 1 % |

| Performance accuracy on demanding attention tasks | 63 ± 3 % | 54 ± 3 %* |

| Systemic nicotine changes attentional accuracy on demanding tasks | −5 ± 1 %** | −1 ± 4 % |

Data are shown as mean ± SEM (where appropriate)

* Indicates a statistically significant difference from WT with P < 0.05

** Indicates a statistically significant change from baseline with P < 0.05

Sex differences in nicotinic excitation of layer VI neurons during postnatal development

Interestingly, there are also developmental sex differences in nicotinic excitation [92]. Prefrontal layer VI nicotinic currents show a similar developmental profile in males and females, with peak nicotinic excitation achieved around the 3rd week of postnatal life and declining by the 5th week. However, within the 1st postnatal month, nicotinic currents are larger and observed in a greater proportion of cells in males than in females. It is not known whether there are any sex differences in α5 expression or function, although it appears that a similar percentage of layer VI neurons express α4 nAChRs in developing male and female mice [92]. In fact, this sex difference in nicotinic excitation of layer VI neurons during postnatal development may arise from differences in cortical neurosteroid levels between males and females. The sex steroid progesterone, for example, can directly suppress nicotinic currents through negative allosteric modulation of α4β2* nAChRs [130, 131]. The pre-pubertal rodent brain expresses all the enzymes necessary for the de novo synthesis of progesterone from cholesterol [132, 133], and the rate-limiting enzyme in this pathway shows a trend toward greater cortical expression in females than males at this stage of development [132]. Furthermore, evidence suggests that estrogenic steroid hormones may directly interact with the nicotinic receptor to potentiate excitatory ACh responses [134]. Developmental sex differences in the maturation of attention circuitry may help account for vulnerability to attention deficit disorders, which are twice as prevalent in males than females [135–137].

Additional mechanisms of cholinergic modulation of prefrontal cortex

Although nicotinic receptors located on pyramidal neurons in layer VI of the medial prefrontal cortex play a critical role in mediating attentional processes, they do not act in isolation. There are cholinergic receptors on other prefrontal neurons and on neurons in other brain regions that also contribute to attentional processing in prefrontal cortex. Relevant cholinergic receptors within prefrontal cortex itself include those on layer V neurons, on the terminals of thalamocortical projections, monoaminergic projections, and on cortical interneurons.

Acetylcholine exerts layer-specific effects in the prefrontal cortex [61], and although nicotinic stimulation exerts many effects across the prefrontal cortical column, it appears to enhance preferentially deep layer activation [61]. An elegant optogenetic study by Olsen et al. [60] has recently demonstrated that in the visual cortex, activation of layer VI cells exerts powerful gain control by means of feedback inhibition of the cortical column. It is tempting to speculate that preferential activation of the deep layers of prefrontal cortex by acetylcholine facilitates such information processing. As we have seen, layer VI pyramidal neurons show a robust excitatory response to acetylcholine mediated by postsynaptic somatodendritic nicotinic receptors [36, 37]. In contrast to layer VI, the layer V pyramidal neurons of the prefrontal cortex are predominantly subject to muscarinic modulation [138], although a rapid α7-mediated nicotinic response has been documented in the prefrontal cortex of juvenile mice [61]. Importantly in this layer, α4β2*-containing nicotinic receptors on thalamocortical terminals strongly facilitate thalamic excitation of layer V pyramidal neurons [139–141], an indirect effect that translates into a large increase in the frequency of rapid, glutamatergic excitatory postsynaptic currents. Of note, a positive feedback relationship has been demonstrated between nicotinic-elicited prefrontal glutamatergic release and the release of acetylcholine itself from cholinergic terminals in prefrontal cortex [97, 98, 142]. Nicotinic receptors have also been implicated in the modulation of monoamine release in the prefrontal cortex [143–145].

Nicotinic modulation of prefrontal GABAergic interneurons also likely contributes to attentional processing. Although α4β2*- and α7-containing nicotinic receptors excite only limited subpopulations of interneurons in the cerebral cortex [146, 147], many layer-specific effects have been documented. In layer VI, fast-spiking interneurons are excited indirectly by nicotinic stimulation [36], presumably due to innervation by corticothalamic axon collaterals [101]. In layer V, stimulation of nicotinic receptors on GABAergic interneurons increases the frequency of inhibitory postsynaptic currents on pyramidal neurons [148, 149], promotes intracolumnar inhibition [150], and modulates spike timing-dependent synaptic plasticity [149]. Most pyramidal neurons in layer II/III do not contain nicotinic receptors, nor do they receive glutamatergic inputs subject to nicotinic modulation ([61], but see [151, 152]). Instead, nicotinic receptors are found on interneurons that exert feedforward inhibition onto layer II/III pyramidal cells [61]. Nicotinic stimulation of the superficial layer I interneurons enhances synchronous activity of inhibitory cortical networks in superficial cortex [153, 154].

Nicotinic receptor and prefrontal attention circuitry in health and disease

The prefrontal cortex is a critical node in widespread and dynamic brain networks that sustain higher cognitive function in health and that perpetuate executive dysfunction in psychiatric illness [155, 156]. The cholinergic modulation of prefrontal cortex is especially powerful in its ability to subsequently influence downstream cortical and subcortical networks [4, 157, 158], as well as being uniquely positioned to exert feedback control on neuromodulatory centers [159], including the cholinergic nuclei [160, 161]. Neuroimaging studies have revealed that the prefrontal cortex is consistently activated on attention tasks, often in conjunction with the parietal cortex [162–165], which is recruited by the prefrontal cortex under conditions of increased attentional demand [157].

A substantial body of work addresses the effects of acetylcholine on attention by manipulating endogenous levels of acetylcholine and by pharmacologically or genetically altering nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Indeed, many genetic and pharmacological studies using both animal models and human subjects have found that nicotinic acetylcholine receptors are of particular importance for attention, as summarized in Table 2. Knockout mouse strains for the α5, β2, and α7 nicotinic receptor subunits have all been found to display impaired attention performance on the 5-CSRTT [37, 38, 166, 167], and human subjects expressing genetic variations in the α5, α4, or β2 genes are associated with increased risk for nicotine dependence [168–174], which may in part develop as a result of attention deficits that promote early experimentation with drugs and alcohol [168, 170, 172]. Pharmacologically, various nicotinic agonists have been found to improve attention performance in animal studies [175–180], whereas nicotinic antagonists appear to disrupt attention [178, 181]. However, it is important to note that the effects of nicotine may depend on the history of nicotine exposure [182] and on strain/species differences [37, 183].

Table 2.

Nicotinic receptor effects on attention

| Manipulation | Species | Task | Effects on attention | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic studies | ||||

| α5 subunit KO | Mice | 5-CSRTT | ↓ | [37] |

| β2 subunit KO | Mice | 5-CSRTT | ↓ | [38] |

| α7 subunit KO | Mice | 5-CSRTT | ↓ | [166, 167, 234] |

| Mice | 5-CSRTT | – | [38] | |

| Human polymorphisms (arrow indicates effect of the risk allele) | ||||

| α5 subunit | Humans | Selective and sustained attention (CPT) | ↓ | [168] |

| n-back/CPT | ↓ | [235] | ||

| α4 subunit | Humans | ADHD inattentive symptoms | ↓ | [236] |

| Cued visual search task | ↓ | [237] | ||

| Selective and sustained attention (CPT) | ↓ | [168] | ||

| Multiple object tracking and visual search | ↓ | [238] | ||

| β2 subunit | Humans | Selective attention (CPT) | ↓ | [168] |

| α7 subunit | Humans | Sustained attention (CPT) |

↑ in smokers ↓ in nonsmokers |

[168] |

| Lesion studies | ||||

| Basal forebrain lesions | Rats | 5-CSRTT | ↓ | [13, 176, 239, 240] |

| Nucleus basalis of Meynert lesions | Rats | 5-CSRTT | ↓ | [28, 31, 32] |

| mPFC lesions | Rats | 5-CSRTT | ↓ | [241, 242] |

| mPFC lesions | Rats | Attentional set-shifting | ↓ | [243] |

| Lesions of PFC cholinergic fibers | Rats | 5-CSRTT | ↓ | [17] |

| Lesions of PFC cholinergic fibers | Rats | SAT/dSAT | ↓ | [18] |

| Pharmacological studies | ||||

| Nicotine (agonist of nicotinic receptors, but act as an antagonist by desensitization) | ||||

| Nicotine | Monkeys | Covert orienting | ↑ | [244] |

| Nicotine | Monkeys | DMTS-D | ↑ | [175] |

| Nicotine | Rats | 5-CSRTT | ↑ | [245] |

| Nicotine | Rats | 5-CSRTT | – | [246] |

| Nicotine | Rats | Stimulus detection | ↑ | [178, 247–249] |

| Nicotine | Rats | 5-CSRTT | ↑ | [180, 182, 250–253] |

| Nicotine | Rats (two strains) | 5-CSRTT |

↑ in Sprague–Dawley –in Lister |

[177] |

| Nicotine | Rats | 5-CSRTT | –(acute), ↑ (chronic) | [182] |

| Nicotine (local to HIP or mPFC) | Rats | 5-CSRTT | –(HIP), ↑ (mPFC) | [180] |

| Nicotine | Mice | 5-CSRTT | ↑ | [234] |

| Nicotine (local to mPFC) | Rats | 3-CSRTT | ↑ (mPFC) | [141] |

| Nicotine | Rats | 5-CSRTT | ↑ (acute and chronic) | [254] |

| Nicotine | Mice (three strains) | 5-CSRTT |

–(acute) ↑ (chronic) in all strains |

[183] |

| Nicotine | Mice | 5-CSRTT | ↓ | [37] |

| Nicotine | Rats | SAT | ↓ | [98] |

| Nicotine | Rats | Attention set-shifting | ↑ (acute and sub-chronic) | [255] |

| Nicotine | Mice | 5-CSRTT | ↑ | [256] |

| Nicotine (tablets) | Humans | Rapid info processing | ↑ | [186] |

| Nicotine (gum) | Humans | Two-letter/digit recall | ↓ | [191, 193] |

| Nicotine (subcutaneous) | Humans | Reaction time | – | [189] |

| Nicotine (subcutaneous) | Humans | Digit recall | ↓ | [192] |

| Nicotine (patch) | Humans | POMS/CPT/Digit recall | ↑ | [188] |

| Nicotine (gum) | Humans | Flight simulator | ↑ | [187] |

| Nicotine (patch) | Humans | Digit recall | – | [257] |

| Nicotine (patch) | Humans | Covert orienting | – | [258] |

| Nicotine (subcutaneous) | Humans | N-back | ↑ | [162] |

| Nicotine (gum) | Humans | ANT | – | [190] |

| Nicotine (gum) | Humans | Cue target detection | ↑ | [259] |

| Nicotine (gum) | Humans | Discrimination (Posner-type) | – | [260] |

| Nicotine (patch) | Humans | Stroop | – | [261] |

| Nicotine (gum) | Humans | Discrimination (Posner-type) | ↑ | [262, 263] |

| Nicotine (patch) | Humans | Multiple tasks | ↑ | [264] |

| Nicotine (gum) | Humans | RVIP | ↑ | [265] |

| Nicotine (patch) | Humans | Stroop/ANT | ↑ (Stroop), ↓ (ANT) | [266] |

| Nicotine (intranasal) | Humans | CPT | ↑ | [267] |

| Agonists of nicotinic receptors | ||||

| ABT-418/ABT-089 | Rats | DMTS-D | ↑ | [175, 176] |

| SIB-1533A | Rats | 5-CSRTT | – | [250] |

| Dizocilpine then SIB-1533A | Rats | 5-CSRTT | ↓ (diz), attenuation with SIB | [268] |

| SIB-1533A | Monkeys | DMTS-D | ↑ | [268] |

| Epibatidine/ABT-418/isoarecolone/AR-R 17779 | Rats | 5-CSRTT | ↑ (epi, ABT, iso), –(AR-R) | [180] |

| ABT-594/ABT-582941 | Monkeys | DMTS-D | ↑ (ABT-594, ABT-582941) | [269] |

| R3487/galanthamine | Rats | Signal detection | ↑ (R3487), –(gal) | [270] |

| S 38232 | Rats | SAT/dSAT | ↑ | [98] |

| ABT-594 | Rats | 5-CSRTT | ↑ | [271] |

| Dizocilpine/scopolamine then sazetidine-A | Rats | Signal detection | ↓ (diz, sco), attenuation with saz | [179] |

| ABT-418 | Mouse | 5-CSRTT | ↑ | [256] |

| PNU 282987 | Mouse | 5-CSRTT | – | [256] |

| Antagonists of nicotinic receptors | ||||

| Mecamylamine | Rats | 5-CSRTT | ↓ | [272] |

| Mecamylamine/hexamethonium | Rats | 5-CSRTT | ↓ (mec), –(hex) | [273] |

| Mecamylamine | Rats | Signal detection | ↓ | [178, 248] |

| Mecamylamine | Mice | 5-CSRTT | ↓ (mec) in three strains | [183] |

| Mecamylamine | Humans | Digit vigilance, RVIP | –(mec) | [274] |

| Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors | ||||

| Physostigmine | Rats | 5-CSRTT | – | [272] |

| Donepezil | Humans | Flight simulator | ↑ | [275] |

| Donepezil | Humans | Anti-cueing | ↑ (voluntary attention only) | [276] |

| Acetylcholine reuptake blockers | ||||

| Hemicholinium | Rats | 5-CSRTT | ↓ | [13] |

The agonist nicotine is an interesting example since it is selective for nicotinic receptors and has been used in a large number of animal and human studies. Overall, the effects of nicotine in humans are far more complex and controversial, with inconsistent effects on attention performance [184, 185]. While nicotine has also been shown to improve attention in humans [186–188], this is not always the case [189–193]. Evidence suggests that nicotine may have differential effects in human smoker and non-smoker populations [185, 194–196], and in patients with attention deficits [197, 198].

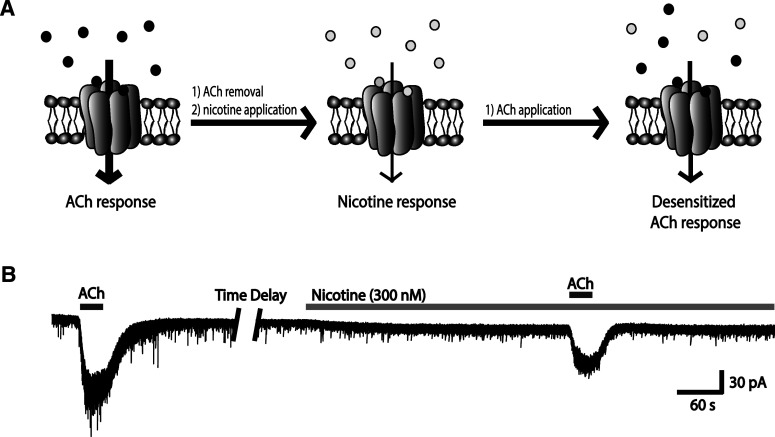

At the cellular level, nicotinic receptors are subject to desensitization; that is, they can become temporarily inactive in the continued presence of agonist, leading to a reduction in response [83, 84]. Nicotine, at levels normally seen in the blood of smokers (~300 nM) [199–201], can have such an effect on α4β2* receptors [36, 37], as illustrated in Fig. 7. Interestingly, Bailey et al. [37] reported that the α5 subunit normally protects against nicotine-induced desensitization, since layer VI neurons from WT mice show half as much desensitization as those of α5−/− mice. The low-affinity α7* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, on the other hand, do not appear to desensitize at these concentrations [202].

Fig. 7.

A concentration of nicotine similar to that seen in the blood of smokers markedly reduces subsequent nicotinic receptor-mediated responses to acetylcholine (ACh). a Schematic of the acetylcholine response, nicotine response, and acetylcholine response following receptor desensitization by nicotine. b Representative whole-cell recordings of a layer VI pyramidal neurons showing: (1) an initial response to ACh, (2) response to nicotine, and (3) response to ACh following desensitization by nicotine. Figure adapted from Bailey et al. [37]

Deficits in attention have been reported in normal human aging [203] as well as a multitude of neurological and psychiatric disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease and schizophrenia [204–207]. Decreases in prefrontal nicotinic receptor binding are observed in patients suffering from mild cognitive impairment [208, 209] as well as Alzheimer’s disease [210–215], and schizophrenia has been associated both with α7 subunit polymorphisms and expression changes [216, 217], as well as a with a higher incidence of the noncoding α5 nicotinic subunit polymorphism [218, 219]. What is more, nicotinic agonists of the α4β2* and α7 nicotinic receptors have been proposed as potential therapeutics for schizophrenia [220], Alzheimer’s disease [221–224], and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder [225–229].

In conclusion

Layer VI nicotinic receptors are integral components of prefrontal attention circuitry in development and adulthood. Despite recent advances, there remains much to be understood about their effects on the maturation of the prefrontal cortex and the modulation of its neurons and networks. Fundamental questions about the regulation of nicotinic receptors in neurons of the living brain remain unanswered. An apparently large reserve of nicotinic receptors within layer VI prefrontal neurons [63, 92], for example, suggests the potential for targeted upregulation to the membrane [230, 231]. It is interesting to note that nicotinic receptor trafficking abnormalities have been documented in psychiatric illness [232]. The issue of physiological and structural plasticity [59, 63] further suggests that the brain may be fundamentally different in certain conditions, and the best treatments may not be those that would improve the performance of the normal brain. In this regard, it is essential for research to examine the realities of prefrontal attention circuitry in different conditions associated with attention deficits. These issues are all the more important to resolve given that nicotinic receptors in layer VI of prefrontal cortex are positioned to be potential drug targets in the treatment of the attention deficits associated with psychiatric and neurological diseases [233].

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by grants to EKL from the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR, MOP 89825), the Canadian Foundation for Innovation, and the Province of Ontario (Early Researcher Award). EKL holds a Canada Research Chair (tier II) in Developmental Cortical Neurophysiology. EP is supported by a doctoral fellowship from the Ontario Mental Health Foundation. MP is supported by an NSERC undergraduate student research award. MKT is supported by a Banting and Best Canada Graduate Scholarship. CDCB is funded by an NSERC Discovery Grant.

References

- 1.Crick F. Function of the thalamic reticular complex: the searchlight hypothesis. PNAS. 1984;81:4586–4590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.14.4586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knudsen EI. Fundamental components of attention. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2007;30:57–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller EK, Cohen JD. An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:167–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Funahashi S. Neuronal mechanisms of executive control by the prefrontal cortex. Neurosci Res. 2001;39:147–165. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(00)00224-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baddeley A. Working memory. Science. 1992;255:556–559. doi: 10.1126/science.1736359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dehaene S, Changeux J-P. Experimental and theoretical approaches to conscious processing. Neuron. 2011;70:200–227. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petersen SE, Posner MI. The attention system of the human brain: 20 years after. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2012;35:73–89. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-062111-150525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deutsch JA, Rocklin KW. Amnesia induced by scopolamine and its temporal variations. Nature. 1967;216:89–90. doi: 10.1038/216089b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deutsch JA. The cholinergic synapse and the site of memory. Science. 1971;174:788–794. doi: 10.1126/science.174.4011.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warburton DM, Brown K. Attenuation of stimulus sensitivity induced by scopolamine. Nature. 1971;230:126–127. doi: 10.1038/230126a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robbins TW, Everitt BJ, Marston HM, et al. Comparative effects of ibotenic acid- and quisqualic acid-induced lesions of the substantia innominata on attentional function in the rat: further implications for the role of the cholinergic neurons of the nucleus basalis in cognitive processes. Behav Brain Res. 1989;35:221–240. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(89)80143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunnett SB, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. The basal forebrain-cortical cholinergic system: interpreting the functional consequences of excitotoxic lesions. Trends Neurosci. 1991;14:494–501. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(91)90061-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muir JL, Dunnett SB, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Attentional functions of the forebrain cholinergic systems: effects of intraventricular hemicholinium, physostigmine, basal forebrain lesions and intracortical grafts on a multiple-choice serial reaction time task. Exp Brain Res. 1992;89:611–622. doi: 10.1007/BF00229886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muir JL, Page KJ, Sirinathsinghji DJ, et al. Excitotoxic lesions of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons: effects on learning, memory and attention. Behav Brain Res. 1993;57:123–131. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(93)90128-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pang K, Williams MJ, Egeth H, Olton DS. Nucleus basalis magnocellularis and attention: effects of muscimol infusions. Behav Neurosci. 1993;107:1031–1038. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.107.6.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voytko ML, Olton DS, Richardson RT, et al. Basal forebrain lesions in monkeys disrupt attention but not learning and memory. J Neurosci. 1994;14:167–186. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-01-00167.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dalley JW, Theobald DE, Bouger P, et al. Cortical cholinergic function and deficits in visual attentional performance in rats following 192 IgG-saporin-induced lesions of the medial prefrontal cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14:922–932. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newman LA, McGaughy J. Cholinergic deafferentation of prefrontal cortex increases sensitivity to cross-modal distractors during a sustained attention task. J Neurosci. 2008;28:2642–2650. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5112-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bigl V, Woolf NJ, Butcher LL. Cholinergic projections from the basal forebrain to frontal, parietal, temporal, occipital, and cingulate cortices: a combined fluorescent tracer and acetylcholinesterase analysis. Brain Res Bull. 1982;8:727–749. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(82)90101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mesulam MM, Mufson EJ, Wainer BH, Levey AI. Central cholinergic pathways in the rat: an overview based on an alternative nomenclature (Ch1–Ch6) Neuroscience. 1983;10:1185–1201. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(83)90108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mesulam MM, Mufson EJ, Levey AI, Wainer BH. Cholinergic innervation of cortex by the basal forebrain: cytochemistry and cortical connections of the septal area, diagonal band nuclei, nucleus basalis (Substantia innominata), and hypothalamus in the rhesus monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1983;214:170–197. doi: 10.1002/cne.902140206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woolf NJ, Eckenstein F, Butcher LL. Cholinergic projections from the basal forebrain to the frontal cortex: a combined fluorescent tracer and immunohistochemical analysis in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1983;40:93–98. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(83)90285-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rye DB, Wainer BH, Mesulam MM, et al. Cortical projections arising from the basal forebrain: a study of cholinergic and noncholinergic components employing combined retrograde tracing and immunohistochemical localization of choline acetyltransferase. Neuroscience. 1984;13:627–643. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(84)90083-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewis DA. Distribution of choline acetyltransferase-immunoreactive axons in monkey frontal cortex. Neuroscience. 1991;40:363–374. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90126-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woolf NJ. Cholinergic systems in mammalian brain and spinal cord. Prog Neurobiol. 1991;37:475–524. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(91)90006-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mrzijak L, Pappy M, Leranth C, Goldman-Rakic PS. Cholinergic synaptic circuitry in the-1. J Comp Neurol. 1995;357:603–617. doi: 10.1002/cne.903570409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGaughy J, Kaiser T, Sarter M. Behavioral vigilance following infusions of 192 IgG-saporin into the basal forebrain: selectivity of the behavioral impairment and relation to cortical AChE-positive fiber density. Behav Neurosci. 1996;110:247–265. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.110.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGaughy J, Dalley JW, Morrison CH, et al. Selective behavioral and neurochemical effects of cholinergic lesions produced by intrabasalis infusions of 192 IgG-saporin on attentional performance in a five-choice serial reaction time task. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1905–1913. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-01905.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parikh V, Kozak R, Martinez V, Sarter M. Prefrontal acetylcholine release controls cue detection on multiple timescales. Neuron. 2007;56:141–154. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Passetti F, Dalley JW, O’Connell MT, et al. Increased acetylcholine release in the rat medial prefrontal cortex during performance of a visual attentional task. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:3051–3058. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dalley JW, McGaughy J, O’Connell MT, et al. Distinct changes in cortical acetylcholine and noradrenaline efflux during contingent and noncontingent performance of a visual attentional task. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4908–4914. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-13-04908.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Himmelheber AM, Sarter M, Bruno JP. Increases in cortical acetylcholine release during sustained attention performance in rats. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res. 2000;9:313–325. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(00)00012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kozak R, Bruno JP, Sarter M. Augmented prefrontal acetylcholine release during challenged attentional performance. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16:9–17. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarter M, Gehring WJ, Kozak R. More attention must be paid: the neurobiology of attentional effort. Brain Res Rev. 2006;51:145–160. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Howe WM, Berry AS, Francois J, et al. Prefrontal cholinergic mechanisms instigating shifts from monitoring for cues to cue-guided performance: converging electrochemical and fMRI evidence from rats and humans. J Neurosci. 2013;33:8742–8752. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5809-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kassam SM, Herman PM, Goodfellow NM, et al. Developmental excitation of corticothalamic neurons by nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Neurosci. 2008;28:8756–8764. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2645-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bailey CDC, De Biasi M, Fletcher PJ, Lambe EK. The nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha5 subunit plays a key role in attention circuitry and accuracy. J Neurosci. 2010;30:9241–9252. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2258-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guillem K, Bloem B, Poorthuis RB, et al. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor beta2 subunits in the medial prefrontal cortex control attention. Science. 2011;333:888–891. doi: 10.1126/science.1207079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sarter M, Paolone G. Deficits in attentional control: cholinergic mechanisms and circuitry-based treatment approaches. Behav Neurosci. 2011;125:825–835. doi: 10.1037/a0026227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sarter M, Givens B, Bruno JP. The cognitive neuroscience of sustained attention: where top-down meets bottom–up. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2001;35:146–160. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sarter M, Hasselmo ME, Bruno JP, Givens B. Unraveling the attentional functions of cortical cholinergic inputs: interactions between signal-driven and cognitive modulation of signal detection. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005;48:98–111. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thomson AM. Neocortical layer 6, a review. Front Neuroanat. 2010;4:13. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2010.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alitto HJ, Usrey WM. Corticothalamic feedback and sensory processing. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13:440–445. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gabbott PL, Warner TA, Jays PR, et al. Prefrontal cortex in the rat: projections to subcortical autonomic, motor, and limbic centers. J Comp Neurol. 2005;492:145–177. doi: 10.1002/cne.20738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zikopoulos B, Barbas H. Prefrontal projections to the thalamic reticular nucleus form a unique circuit for attentional mechanisms. J Neurosci. 2006;26:7348–7361. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5511-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Briggs F, Usrey WM. Corticogeniculate feedback and visual processing in the primate. J Physiol-London. 2011;589:33–40. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.193599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cudeiro J, Sillito AM. Looking back: corticothalamic feedback and early visual processing. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:298–306. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sherman SM. The thalamus is more than just a relay. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:417–422. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang L, Jones EG. Corticothalamic inhibition in the thalamic reticular nucleus. J Neurophysiol. 2004;91:759–766. doi: 10.1152/jn.00624.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.von Krosigk M, Monckton JE, Reiner PB, Mccormick DA. Dynamic properties of corticothalamic excitatory postsynaptic potentials and thalamic reticular inhibitory postsynaptic potentials in thalamocortical neurons of the guinea-pig dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus. Neuroscience. 1999;91:7–20. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00557-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Destexhe A. Modelling corticothalamic feedback and the gating of the thalamus by the cerebral cortex. J Physiol Paris. 2000;94:391–410. doi: 10.1016/s0928-4257(00)01093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smythies J. The functional neuroanatomy of awareness: with a focus on the role of various anatomical systems in the control of intermodal attention. Conscious Cogn. 1997;6:455–481. doi: 10.1006/ccog.1997.0315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guillery RW, Sherman SM. Thalamic relay functions and their role in corticocortical communication: generalizations from the visual system. Neuron. 2002;33:163–175. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00582-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Van der Werf Y, Witter M, Groenewegen H. The intralaminar and midline nuclei of the thalamus. Anatomical and functional evidence for participation in processes of arousal and awareness. Brain Res Rev. 2002;39:107–140. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00181-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Berendse HW, Groenewegen HJ. Restricted cortical termination fields of the midline and intralaminar thalamic nuclei in the rat. Neuroscience. 1991;42:73–102. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90151-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hoover WB, Vertes RP. Anatomical analysis of afferent projections to the medial prefrontal cortex in the rat. Brain Struct Funct. 2007;212:149–179. doi: 10.1007/s00429-007-0150-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vertes RP. Interactions among the medial prefrontal cortex, hippocampus and midline thalamus in emotional and cognitive processing in the rat. Neuroscience. 2006;142:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dempsey EW, Morison RS. The electrical activity of a thalamocortical relay system. Am J Physiol. 1942;138:283–296. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tian MK, Bailey CDC, De Biasi M, et al. Plasticity of prefrontal attention circuitry: upregulated muscarinic excitability in response to decreased nicotinic signaling following deletion of α5 or β2 subunits. J Neurosci. 2011;31:16458–16463. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3600-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Olsen SR, Bortone DS, Adesnik H, Scanziani M. Gain control by layer six in cortical circuits of vision. Nature. 2012;482:47–52. doi: 10.1038/nature10835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Poorthuis RB, Bloem B, Schak B, et al. Layer-specific modulation of the prefrontal cortex by nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Cereb Cortex. 2012;23:148–161. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Henny P, Jones BE. Projections from basal forebrain to prefrontal cortex comprise cholinergic, GABAergic and glutamatergic inputs to pyramidal cells or interneurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:654–670. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06029.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bailey CDC, Alves NC, Nashmi R, et al. Nicotinic α5 subunits drive developmental changes in the activation and morphology of prefrontal cortex layer VI neurons. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71:120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Houser CR, Crawford GD, Salvaterra PM, Vaughn JE. Immunocytochemical localization of choline acetyltransferase in rat cerebral cortex: a study of cholinergic neurons and synapses. J Comp Neurol. 1985;234:17–34. doi: 10.1002/cne.902340103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gotti C, Clementi F, Fornari A, et al. Structural and functional diversity of native brain neuronal nicotinic receptors. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;78:703–711. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Albuquerque EX, Pereira EFR, Alkondon M, Rogers SW. Mammalian nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: from structure to function. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:73–120. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fucile S. Ca2+ permeability of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Cell Calcium. 2004;35:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lindstrom J (2000) The structures of neuronal nicotinic receptors. In: Neuronal nicotinic receptors. Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg, pp 101–162

- 69.Moroni M, Zwart R, Sher E, et al. alpha4beta2 nicotinic receptors with high and low acetylcholine sensitivity: pharmacology, stoichiometry, and sensitivity to long-term exposure to nicotine. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:755–768. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.023044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Marks MJ, Meinerz NM, Brown RWB, Collins AC. 86Rb+ efflux mediated by alpha4beta2*-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors with high and low-sensitivity to stimulation by acetylcholine display similar agonist-induced desensitization. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80:1238–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tapia L, Kuryatov A, Lindstrom J. Ca2+ permeability of the (alpha4)3(beta2)2 stoichiometry greatly exceeds that of (alpha4)2(beta2)3 human acetylcholine receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:769–776. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.030445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Grady SR, Wageman CR, Patzlaff NE, Marks MJ. Low concentrations of nicotine differentially desensitize nicotinic acetylcholine receptors that include α5 or α6 subunits and that mediate synaptosomal neurotransmitter release. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:1935–1943. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ferreira M, Ebert SN, Perry DC, et al. Evidence of a functional alpha7-neuronal nicotinic receptor subtype located on motoneurons of the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;296:260–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Léna C, Changeux J-P. The role of beta2-subunit-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the brain explored with a mutant mouse. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;868:611–616. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb11333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Perry DC, Xiao Y, Nguyen HN, et al. Measuring nicotinic receptors with characteristics of alpha4beta2, alpha3beta2 and alpha3beta4 subtypes in rat tissues by autoradiography. J Neurochem. 2002;82:468–481. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wada E, Wada K, Boulter J, et al. Distribution of alpha2, alpha3, alpha4, and beta2 neuronal nicotinic receptor subunit mRNAs in the central nervous system: a hybridization histochemical study in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1989;284:314–335. doi: 10.1002/cne.902840212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hill JA, Zoli M, Bourgeois JP, Changeux J-P. Immunocytochemical localization of a neuronal nicotinic receptor: the beta2-subunit. J Neurosci. 1993;13:1551–1568. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-04-01551.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nakayama H, Shioda S, Okuda H, et al. Immunocytochemical localization of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in rat cerebral cortex. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1995;32:321–328. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(95)00092-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gotti C, Clementi F. Neuronal nicotinic receptors: from structure to pathology. Prog Neurobiol. 2004;74:363–396. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dominguez del Toro E, Juiz JM, Peng X, et al. Immunocytochemical localization of the alpha 7 subunit of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in the rat central nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 1994;349:325–342. doi: 10.1002/cne.903490302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Han ZY, Le Novère N, Zoli M, et al. Localization of nAChR subunit mRNAs in the brain of Macaca mulatta . Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:3664–3674. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gotti C, Zoli M, Clementi F. Brain nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: native subtypes and their relevance. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:482–491. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Giniatullin R, Nistri A, Yakel JL. Desensitization of nicotinic ACh receptors: shaping cholinergic signaling. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:371–378. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Quick MW, Lester RAJ. Desensitization of neuronal nicotinic receptors. J Neurobiol. 2002;53:457–478. doi: 10.1002/neu.10109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Conroy WG, Vernallis AB, Berg DK. The alpha5 gene product assembles with multiple acetylcholine receptor subunits to form distinctive receptor subtypes in brain. Neuron. 1992;9:679–691. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wada E, McKinnon D, Heinemann S, et al. The distribution of mRNA encoded by a new member of the neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor gene family (alpha5) in the rat central nervous system. Brain Res. 1990;526:45–53. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90248-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ramirez-Latorre J, Yu CR, Qu X, et al. Functional contributions of alpha5 subunit to neuronal acetylcholine receptor channels. Nature. 1996;380:347–351. doi: 10.1038/380347a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kuryatov A, Onksen J, Lindstrom J. Roles of accessory subunits in alpha4beta2(*) nicotinic receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:132–143. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.046789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mao D, Perry DC, Yasuda RP, et al. The alpha4beta2alpha5 nicotinic cholinergic receptor in rat brain is resistant to up-regulation by nicotine in vivo. J Neurochem. 2008;104:446–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.McClure-Begley TD, King NM, Collins AC, et al. Acetylcholine-stimulated [3H]GABA release from mouse brain synaptosomes is modulated by alpha4beta2 and alpha4alpha5beta2 nicotinic receptor subtypes. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75:918–926. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.052274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Grady SR, Salminen O, McIntosh JM, et al. Mouse striatal dopamine nerve terminals express alpha4alpha5beta2 and two stoichiometric forms of alpha4beta2*-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Mol Neurosci. 2010;40:91–95. doi: 10.1007/s12031-009-9263-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Alves NC, Bailey CDC, Nashmi R, Lambe EK. Developmental sex differences in nicotinic currents of prefrontal layer VI neurons in mice and rats. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e9261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Marks MJ, Pauly JR, Gross SD, et al. Nicotine binding and nicotinic receptor subunit RNA after chronic nicotine treatment. J Neurosci. 1992;12:2765–2784. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-07-02765.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Salas R, Orr-Urtreger A, Broide RS, et al. The nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit alpha5 mediates short-term effects of nicotine in vivo. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:1059–1066. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.5.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Winzer-Serhan UH, Leslie FM. Expression of alpha5 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit mRNA during hippocampal and cortical development. J Comp Neurol. 2005;481:19–30. doi: 10.1002/cne.20357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Brown RWB, Collins AC, Lindstrom JM, Whiteaker P. Nicotinic alpha5 subunit deletion locally reduces high-affinity agonist activation without altering nicotinic receptor numbers. J Neurochem. 2007;103:204–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Parikh V, Man K, Decker MW, Sarter M. Glutamatergic contributions to nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist-evoked cholinergic transients in the prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2008;28:3769–3780. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5251-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Howe WM, Ji J, Parikh V, et al. Enhancement of attentional performance by selective stimulation of alpha4beta2(*) nAChRs: underlying cholinergic mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;35:1391–1401. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.A Mathie DCSGC-C (1990) Rectification of currents activated by nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in rat sympathetic ganglion neurones. J Physiol 427:625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 100.Forster I, Bertrand D. Inward rectification of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors investigated by using the homomeric alpha7 receptor. Proc Biol Sci. 1995;260:139–148. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1995.0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.West DC, Mercer A, Kirchhecker S, et al. Layer 6 cortico-thalamic pyramidal cells preferentially innervate interneurons and generate facilitating EPSPs. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16:200–211. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mercer A, West DC, Morris OT, et al. Excitatory connections made by presynaptic cortico-cortical pyramidal cells in layer 6 of the neocortex. Cereb Cortex. 2005;15:1485–1496. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Robbins TW. The 5-choice serial reaction time task: behavioural pharmacology and functional neurochemistry. Psychopharmacology. 2002;163:362–380. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1154-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sunderland T, Weingartner H, Cohen RM, et al. Low-dose oral lorazepam administration in Alzheimer subjects and age-matched controls. Psychopharmacology. 1989;99:129–133. doi: 10.1007/BF00634466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Foldi NS, Jutagir R, Davidoff D, Gould T. Selective attention skills in Alzheimer’s disease: performance on graded cancellation tests varying in density and complexity. J Gerontol. 1992;47:P146–P153. doi: 10.1093/geronj/47.3.p146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Okonkwo OC, Wadley VG, Ball K, et al. Dissociations in visual attention deficits among persons with mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn. 2008;15:492–505. doi: 10.1080/13825580701844414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Okonkwo OC, Crowe M, Wadley VG, Ball K. Visual attention and self-regulation of driving among older adults. Int Psychogeriatr. 2008;20:162–173. doi: 10.1017/S104161020700539X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Shaw P, Eckstrand K, Sharp W, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is characterized by a delay in cortical maturation. PNAS. 2007;104:19649–19654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707741104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sullivan RM, Brake WG. What the rodent prefrontal cortex can teach us about attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: the critical role of early developmental events on prefrontal function. Behav Brain Res. 2003;146:43–55. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Krain AL, Castellanos FX. Brain development and ADHD. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26:433–444. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Nishimura A, Hohmann CF, Johnston MV, Blue ME. Neonatal electrolytic lesions of the basal forebrain stunt plasticity in mouse barrel field cortex. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2002;20:481–489. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(02)00078-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kuczewski N, Aztiria E, Leanza G, Domenici L. Selective cholinergic immunolesioning affects synaptic plasticity in developing visual cortex. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:1807–1814. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Robertson RT, Gallardo KA, Claytor KJ, et al. Neonatal treatment with 192 IgG-saporin produces long-term forebrain cholinergic deficits and reduces dendritic branching and spine density of neocortical pyramidal neurons. Cereb Cortex. 1998;8:142–155. doi: 10.1093/cercor/8.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Sherren N, Pappas BA. Selective acetylcholine and dopamine lesions in neonatal rats produce distinct patterns of cortical dendritic atrophy in adulthood. Neuroscience. 2005;136:445–456. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Heath CJ, Picciotto MR. Nicotine-induced plasticity during development: modulation of the cholinergic system and long-term consequences for circuits involved in attention and sensory processing. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56(Suppl 1):254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Perry EK, Lee ML, Martin-Ruiz CM, et al. Cholinergic activity in autism: abnormalities in the cerebral cortex and basal forebrain. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1058–1066. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.7.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Martin-Ruiz CM, Lee M, Perry RH, et al. Molecular analysis of nicotinic receptor expression in autism. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2004;123:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Picard F, Bruel D, Servent D, et al. Alteration of the in vivo nicotinic receptor density in ADNFLE patients: a PET study. Brain. 2006;129:2047–2060. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Breese CR, Lee MJ, Adams CE, et al. Abnormal regulation of high affinity nicotinic receptors in subjects with schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2000;23:351–364. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Marutle A, Zhang X, Court J, et al. Laminar distribution of nicotinic receptor subtypes in cortical regions in schizophrenia. J Chem Neuroanat. 2001;22:115–126. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(01)00117-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kristt DA. Acetylcholinesterase-containing neurons of layer VIb in immature neocortex: possible component of an early formed intrinsic cortical circuit. Anat Embryol. 1979;157:217–226. doi: 10.1007/BF00305161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Mechawar N, Descarries L. The cholinergic innervation develops early and rapidly in the rat cerebral cortex: a quantitative immunocytochemical study. Neuroscience. 2001;108:555–567. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00389-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Romijn HJ, Hofman MA, Gramsbergen A. At what age is the developing cerebral cortex of the rat comparable to that of the full-term newborn human baby? Early Hum Dev. 1991;26:61–67. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(91)90044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Watson RE, Desesso JM, Hurtt ME, Cappon GD. Postnatal growth and morphological development of the brain: a species comparison. Birth Defect Res B. 2006;77:471–484. doi: 10.1002/bdrb.20090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Tribollet E, Bertrand D, Marguerat A, Raggenbass M. Comparative distribution of nicotinic receptor subtypes during development, adulthood and aging: an autoradiographic study in the rat brain. Neuroscience. 2004;124:405–420. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Cimino M, Marini P, Colombo S, et al. Expression of neuronal acetylcholine nicotinic receptor α4 and β2 subunits during postnatal development of the rat brain. J Neural Transm. 1995;100:77–92. doi: 10.1007/BF01271531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Zhang X, Liu C, Miao H, et al. Postnatal changes of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha2, alpha3, alpha4, alpha7 and beta2 subunits genes expression in rat brain. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1998;16:507–518. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(98)00044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Lipton SA, Frosch MP, Phillips MD, et al. Nicotinic antagonists enhance process outgrowth by rat retinal ganglion cells in culture. Science. 1988;239:1293–1296. doi: 10.1126/science.3344435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Pugh PC, Berg DK. Neuronal acetylcholine receptors that bind alpha-bungarotoxin mediate neurite retraction in a calcium-dependent manner. J Neurosci. 1994;14:889–896. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-02-00889.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Bertrand D, Valera S, Bertrand S, et al. Steroids inhibit nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. NeuroReport. 1991;2:277–280. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199105000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Valera S, Ballivet M, Bertrand D. Progesterone modulates a neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. PNAS. 1992;89:9949–9953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Kohchi C, Ukena K, Tsutsui K. Age- and region-specific expressions of the messenger RNAs encoding for steroidogenic enzymes p450scc, P450c17 and 3beta-HSD in the postnatal rat brain. Brain Res. 1998;801:233–238. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00585-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Zwain IH, Yen SS. Neurosteroidogenesis in astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and neurons of cerebral cortex of rat brain. Endocrinology. 1999;140:3843–3852. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.8.6907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Paradiso K, Zhang J, Steinbach JH. The C terminus of the human nicotinic alpha4beta2 receptor forms a binding site required for potentiation by an estrogenic steroid. J Neurosci. 2001;21:6561–6568. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-17-06561.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Brown RT, Freeman WS, Perrin JM, et al. Prevalence and assessment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in primary care settings. Pediatrics. 2001;107:E43. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.3.e43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Cuffe SP, Moore CG, McKeown RE. Prevalence and correlates of ADHD symptoms in the national health interview survey. J Atten Disord. 2005;9:392–401. doi: 10.1177/1087054705280413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Smalley SL, McGough JJ, Moilanen IK, et al. Prevalence and psychiatric comorbidity of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in an adolescent Finnish population. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:1575–1583. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e3181573137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Gulledge AT, Bucci DJ, Zhang SS, et al. M1 receptors mediate cholinergic modulation of excitability in neocortical pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 2009;29:9888–9902. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1366-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Lambe EK, Picciotto MR, Aghajanian GK. Nicotine induces glutamate release from thalamocortical terminals in prefrontal cortex. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003;28:216–225. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]