Abstract

Intra-amniotic exposure to proinflammatory agonists causes chorioamnionitis and fetal gut inflammation. Fetal gut inflammation is associated with mucosal injury and impaired gut development. We tested whether this detrimental inflammatory response of the fetal gut results from a direct local (gut derived) or an indirect inflammatory response mediated by the chorioamnion/skin or lung, since these organs are also in direct contact with the amniotic fluid. The gastrointestinal tract was isolated from the respiratory tract and the amnion/skin epithelia by fetal surgery in time-mated ewes. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or saline (controls) was selectively infused in the gastrointestinal tract, trachea, or amniotic compartment at 2 or 6 days before preterm delivery at 124 days gestation (term 150 days). Gastrointestinal and intratracheal LPS exposure caused distinct inflammatory responses in the fetal gut. Inflammatory responses could be distinguished by the influx of leukocytes (MPO+, CD3+, and FoxP3+ cells), tumor necrosis factor-α, and interferon-γ expression and differential upregulation of mRNA levels for Toll-like receptor 1, 2, 4, and 6. Fetal gut inflammation after direct intestinal LPS exposure resulted in severe loss of the tight junctional protein zonula occludens protein 1 (ZO-1) and increased mitosis of intestinal epithelial cells. Inflammation of the fetal gut after selective LPS instillation in the lungs caused only mild disruption of ZO-1, loss in epithelial cell integrity, and impaired epithelial differentiation. LPS exposure of the amnion/skin epithelia did not result in gut inflammation or morphological, structural, and functional changes. Our results indicate that the detrimental consequences of chorioamnionitis on fetal gut development are the combined result of local gut and lung-mediated inflammatory responses.

Keywords: endotoxin, fetal inflammatory response, necrotizing enterocolitis, sheep

a frequent association with preterm delivery is chorioamnionitis, a bacterial infection of the amniotic fluid, fetal membranes, and placenta (13, 28, 30). Chorioamnionitis is associated with an increased risk for poor postnatal developmental outcomes (3, 4, 15, 32). The inflammatory response to chorioamnionitis is postulated to be the proximal cause of injury to fetal organs, which increase the risk of periventricular leukomalacia (6) necrotizing enterocolitis (3, 4), and bronchopulmonary dysplasia (34, 37). Because the fetus swallows and aspirates the amniotic fluid, infection of the amniotic fluid exposes the premature lungs and intestine directly to bacteria and inflammatory products. In addition, the fetal skin and the amniotic epithelium are exposed to the contaminated amniotic fluid.

We have used a preterm fetal sheep model of chorioamnionitis, induced by bacteria or their proinflammatory components, to characterize the effects of chorioamnionitis on fetal organ development. The earliest organ inflammation after lipopolysaccharide (LPS) exposure was detected in the amnion/chorion (23). A fetal inflammatory response in the lung was initiated within a few hours after intra-amniotic LPS delivery (21, 23). In addition, 2 days after intra-amniotic LPS administration, proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines were detected in the ovine fetal skin (25, 41).

Importantly, the pulmonary and cutaneous inflammatory responses resulted in systemic inflammation of the fetus (21, 24, 27). In contrast to these early responses, we recently observed no signs of inflammation in the fetal intestine 2 days following intra-amniotic injection of LPS or live Ureaplasma parvum (38, 39). However, 7 and 14 days after intra-amniotic injection of LPS or U. parvum, there was an inflammatory response in the preterm gut (38, 39). Therefore, an important question is whether gut inflammation is induced by direct contact with swallowed LPS or the result of indirect inflammation in other fetal organs. The delayed inflammatory response in the fetal intestine impaired the development of the intestinal immune system and barrier function (38–40). The mechanisms underlying disrupted gut development in premature neonates in the course of chorioamnionitis remain largely unknown. Therefore, we asked if the inflammatory response to chorioamnionitis in the fetal gut results from a local (gut-derived) or fetal inflammatory response syndrome (FIRS) mediated by the fetal lung, chorioamnion, or the skin. We surgically isolated the fetal gastrointestinal tract from the respiratory tract and the skin/chorioamnion and evaluated intestinal inflammation and development following LPS administration either in the trachea, the gastrointestinal tract, or the amniotic fluid.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

This study was approved by the animal ethics committee of the University of Western Australian (Perth, WA, Australia) and the Children's Hospital Medical Center (Cincinnati, OH). Fetal lambs were allocated at random to fetal surgery and LPS (Escherichia coli 055:B5; Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) or saline exposure for either 2 or 6 days as defined below and in Table 1. LPS was infused by an osmotic pump over 24 h (Alzet, Cupertino, CA), and the doses used were as follows: 10 mg for inta-amniotic (IA) infusion, 5 mg for gut infusion, and 1 mg for tracheal infusion. These reduced lung and gut infusion doses were based on previous data (26) and the presumed fractional volumes of amniotic fluid that contact the gut and lung. Fetal surgery was performed using strict aseptic precautions. Ewes received premedication with intramuscular injections of buprenorphine (0.02 mg/kg) and acepromazine (0.01 mg/kg) at least 30 min before induction of anesthesia with an intravenous bolus of midazolam (0.25 mg/kg) and ketamine (5 mg/kg). After intubation, general anesthesia was maintained with 1–2% isoflurane. A second surgery was performed at 124 days gestational age (GA) ± 2 days to deliver the fetal sheep, 2 or 6 days after the initial surgery. The ewe and fetus were killed with an intravenous bolus of pentobarbitone (100 mg/kg). The pulmonary and systemic inflammation in these animals was recently reported (24).

Table 1.

Summary of fetal surfaces exposed to intervention (either Escherichia coli LPS or saline) in each surgical group

| 2 Days Exposure |

6 Days Exposure |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedure and Site of Delivery | Site of exposure | n | Abbreviation for group | Site of exposure | n | Abbreviation for group |

| Gut isolation and stomach infusion | Gut LPS | 5 | 2 days LPS gut | Gut LPS | 5 | 6 days LPS gut |

| Lung isolation and tracheal infusion | Lung LPS | 6 | 2 days LPS lung | Lung LPS | 6 | 6 days LPS lung |

| Sham surgery and IA infusion | Gut, lung, skin, amniotic cavity | 6 | 2 days LPS IA | Gut, lung, skin, amniotic cavity | 6 | 6 days LPS IA |

| Snout occlusion and IA infusion | Amniotic cavity skin | 6 | 2 days LPS Ocln | Amniotic cavity skin | 6 | 6 days LPS Ocln |

| Combined control* | Saline 2 days* | 8 | 2 days saline | Saline 6 days* | 8 | 6 days saline |

n, No. of animals. LPS, lipopolysaccharide; IA, intra-amniotic; Ocln, occlusion.

Combined control group for all surgical groups.

Isolation of the fetal lung.

An incision was made in the cartilage ring just below the cricoid cartilage for the insertion of two occlusive catheters. One catheter was connected to a 2-liter collection bag that was sited in the amniotic cavity to collect fetal lung fluid. A second catheter was attached to a miniosmotic pump (secured in a subdermal pocket in the fetal neck) for delivery of 1 mg LPS (or saline for controls) to the distal trachea over a 24-h period. The trachea was occluded around the catheters and ligated above the catheter site. Thus we separated the fluid exchange in fetal lung from the amniotic fluid. Therefore, LPS administered to the fetal lung did not reach the amniotic fluid. We also ligated the esophagus so that amniotic fluid could not be swallowed.

Fetal gastrointestinal tract isolation.

The trachea was cannulated to drain fetal lung fluid to a bag as for the lung surgery. A catheter attached to a miniosmotic pump was passed via a small incision in the esophagus into the stomach. The osmotic pump was secured in a subdermal pocket in the neck and delivered 5 mg LPS (or saline for controls) in the fetal stomach over 24 h. The esophagus was ligated above the catheter insertion site to achieve LPS exposure to the gastrointestinal tract only.

Fetal snout occlusion.

The trachea was cannulated to drain fetal lung fluid to a bag, and the esophagus was ligated as for the other surgery groups. The snout was occluded securely with a sterile, size 6 surgical glove (Ansell, Iselin, NJ). A miniosmotic pump was sutured to a hindlimb for the intra-amniotic delivery of 10 mg LPS (or saline for controls) over a 24-h period. This procedure allowed us to expose only the fetal skin and chorioamnion to LPS, specifically with no exposure of LPS to the oral and nasal epithelium, the tonsils, the lung, or the gastrointestinal tract.

Intra-amniotic.

The surgical procedures were identical to those for the lung, gut, and fetal snout occlusion (“IA Ocln”) groups with the exception that the trachea, esophagus, and fetal snout were not occluded (sham surgery). Thus these animals were able to freely swallow or aspirate amniotic fluid. A miniosmotic pump was sutured to a hindlimb to deliver 10 mg LPS (or saline for controls) in the amniotic fluid over 24 h.

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used: rabbit antibodies against human myeloperoxidase (MPO, catalog no. A0398, 1:500; Dakocytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) and CD3 (catalog no. A0452, Dakocytomation, 1:200); phospho-histone H3 (pHistone-H3) (catalog no. sc-101679, 1:1,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and zonula occludens protein 1 (ZO-1) (catalog no. 617300, 1:100; Invitrogen, San Francisco, CA), monoclonal antibody against human FoxP3 (catalog no. 14-7979-82, 1:250; eBioscience, San Diego, CA), guinea pig antibody against human Kruppel-like factor 5 (KLF5) (1:2,000) (kindly provided by Dr. Jeffrey Whitsett, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH), human Ki-67 (catalog no. M7240, 1:100; Dako), biotin-conjugated goat anti-mouse (catalog no. E0433, 1:200; Dakocytomation), biotin-conjugated swine anti-rabbit (catalog no. E0353 1:200; Dakocytomation), Texas red-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (catalog no. 4050-07, 1:100; ITK Diagnostics SouthernBiotech), peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (catalog no. 111-035-045, 1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA), and biotin-conjugated goat anti-guinea pig (catalog no. 106-065-003, 1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on terminal ileal tissue as described (38). We evaluated the terminal ileum since this region of the gastrointestinal tract is most vulnerable to injury and intestinal pathologies such as necrotizing enterocolitis in the preterm. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded samples (3 μm) were incubated with the primary antibody of interest. After being washed, sections were incubated with the appropriate secondary conjugated antibody. CD3, FoxP3, KLF5, and pHistone-H3 antibodies were detected with the streptavidin-biotin system (Dakocytomation), and the MPO antibody was detected using a peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. Positive staining for MPO and CD3 was visualized with 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (Sigma); nuclei were counterstained with hematoxylin. Immunoreactivity for FoxP3, KLF5, Ki-67, and pHistone-H3 was visualized using nickel-DAB. The number of cells exhibiting immunostaining were counted per single (MPO, CD3, and pHistone-H3, ×200) or three (FoxP3, ×100) high-power fields. Stained sections were scored by three investigators who were blinded to the experimental conditions.

Immunofluoresence

Immunofluoresence was performed and interpreted as described (38). Briefly, ileal cryosections embedded in optimum-cutting temperature (3 μm) compound were incubated with anti-ZO-1 followed by Texas Red-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (Jackson) and 2 min incubation with 2′,6-amino-2-phenyl indole. The ZO-1 distribution was recorded at a magnification of ×200 using the Metasystems Image Pro System (black and white charge-couple device camera; Metasystems, Sandhausen, Germany) mounted on a Leica DM-RE fluorescence microscope (Leica, Wetzler, Germany).

Cytokine and Toll-Like Receptor mRNA Quantitation

Total RNA was isolated from terminal ileal tissue by Trizol/chloroform extraction. mRNA quantitation was performed using real-time PCR. Total RNA was reverse transcribed using oligo(dT) primer and Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies) according to the supplier's recommendations. cDNA was used as a template with primers and Taqman probes (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) specific to sheep sequences. The values for each cytokine or Toll-like receptor (TLR) were normalized to the internal 18S rRNA value. Data were expressed as fold increase over the control values.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

Differences of plasma intestinal fatty acid-binding protein (I-FABP) levels were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to measure intestinal mucosal cell damage (10, 39). A 96-well plate was coated overnight at 4°C with 5 μg of anti-human I-FABP monoclonal antibody. A standard titration curve was developed by serial dilution of a known quantity of human recombinant I-FABP protein. Fetal plasma samples were diluted at least fourfold and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Next, the plates were incubated with biotin-conjugated anti-human I-FABP polyclonal antibody (2 μg/ml), followed by washing and incubation with streptavidin peroxidase for 1 h. After 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine substrate was added, the reaction was stopped with acid, and the optical density was determined at 450 nm. Plasma haptoglobin levels were measured by ELISA following the manufacturer's instructions (catalog no. E-10HPT; ICL, Portland, OR).

Circulatory Endotoxin Levels

Total circulating endotoxin was determined in fetal plasma by a chromogenic limulus amoebocyte lysate assay following the manufacturer's instructions (Genscript, Piscataway, NJ).

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean and SD. The number of cells with immunostaining for MPO, CD3, FoxP3, and pHistone-H3 were counted per high-power field. Because the data were not distributed normally, Mann-Whitney nonparametric U-tests were used for between-group comparisons. In addition, time-dependent TLR changes were separately analyzed by a two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni test for post hoc analysis. Statistical calculations were made using SPSS 15.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL), and differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Systemic Inflammation Following the LPS Exposures

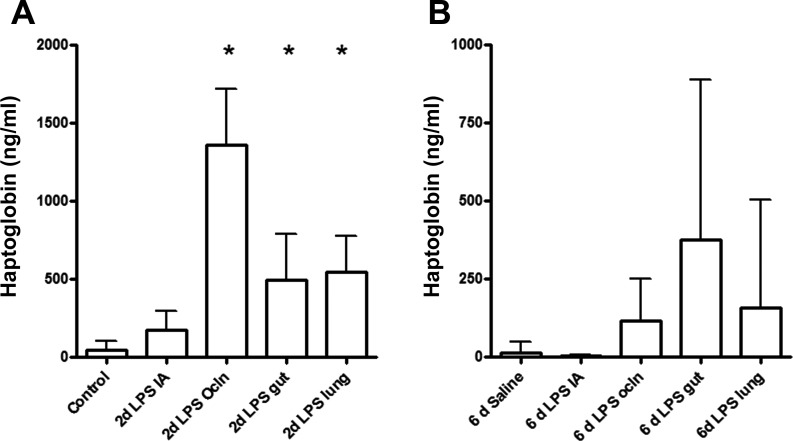

We first determined whether selective LPS exposure of the gut, lung, skin, and chorioamnion resulted in a systemic inflammatory response. The acute phase plasma protein haptoglobin is a marker for systemic inflammation (17). Relative to controls, 2 days LPS exposure resulted in significantly increased concentrations of plasma haptoglobin in “gut,” “lung,” IA Ocln, and “IA” groups (Fig. 1A). Although variable, haptoglobin levels in all groups were not different from control values when lambs were exposed to endotoxin for 6 days (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

The concentration of circulating haptoglobin was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and groups were compared with the Mann-Whitney test. Haptoglobin plasma levels significantly increased in the 2-day “IA Ocln,” 2-day “gut,” and the 2-day “lung” LPS groups (A). No significant changes in circulating haptoglobin levels were detected after 6 days of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) exposure (B). IA, intra-amniotic; Ocln,. *P < 0.05 vs. controls using a Mann-Whitney nonparametric U-test.

LPS in fetal plasma could not be detected within 2 or 6 days post-LPS treatment in any of the experimental groups (data not shown). Systemic inflammation in the 2-day groups after selective LPS exposure is therefore most likely not the result of LPS absorbance and distribution via the fetal blood.

Inflammation in the Fetal Ileum Following Selective Gut, Pulmonary, Cutaneous, or Intra-amniotic LPS Exposure

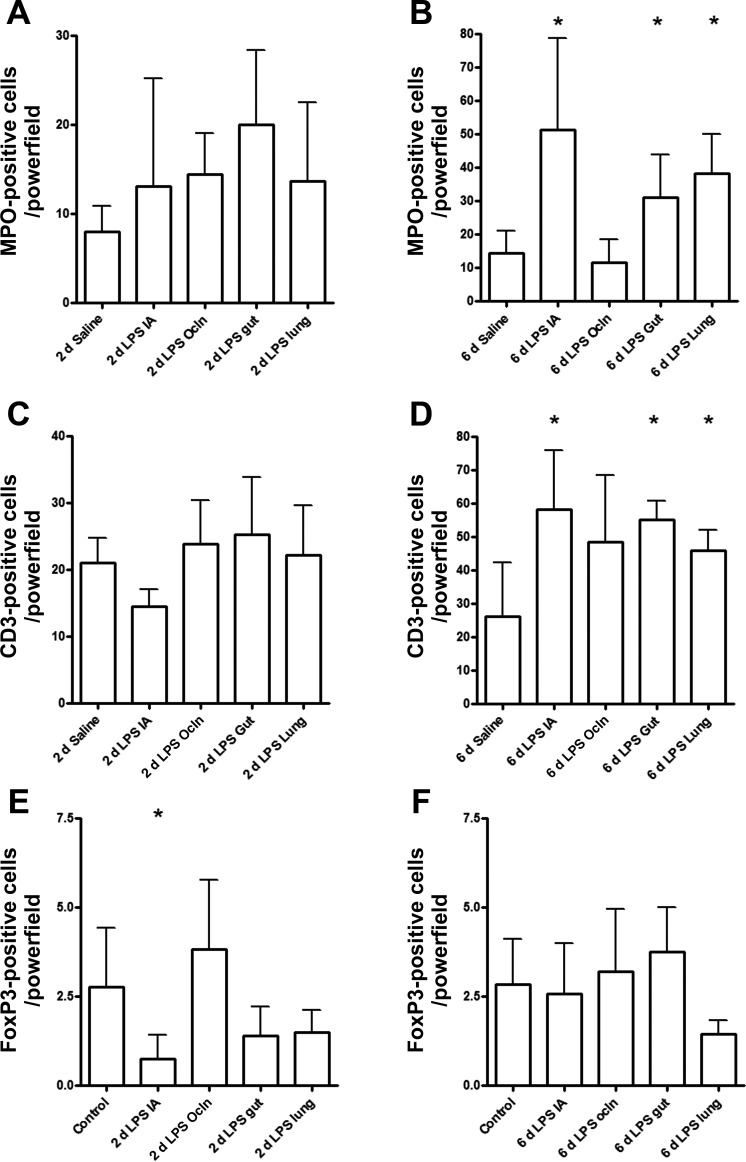

Small numbers of cells expressing MPO, an enzyme expressed by activated neutrophils and monocytes, were detected in the ileum from preterm control animals. The number of infiltrating MPO positive cells did not change after 2 days LPS exposure in any compartment (Fig. 2A). Infusion of LPS in either the lung or the gut for 6 days resulted in increased numbers of MPO-expressing cells in the ileum (Fig. 2B). As described previously (38), intra-amniotic endotoxin exposure for 6 days resulted in an influx of MPO-expressing cells (Fig. 2B) in the fetal ileum, whereas occlusion of the snout before intra-amniotic endotoxin injection did not result in an increased influx of MPO+ cells (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

For each experimental group, myeloperoxidase (MPO, A and B)-, CD3 (C and D)-, or FoxP3 (E and F)-positive cells were counted in the fetal ileum per high-power field, and the average value of the sum of 3 representative areas is given. Groups were compared with the Mann-Whitney test. *P < 0.05 vs. control using a Mann-Whitney nonparametric U-test.

Similar to MPO expression, the number of CD-3-expressing lymphocytes was not altered in any of the 2-day exposure groups (Fig. 2C). After 6 days of LPS treatment, increased CD3+ T cells were detected in the fetal ileum in the gut, lung, and IA groups exposed to LPS. CD3+ cells in the IA Ocln group remained unchanged compared with saline-treated control animals (Fig. 2D).

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) are a subset of T cells that have potent anti-inflammatory effects and can be identified by the expression of the transcription factor FoxP3 (12, 16). Compared with control animals, ileal FoxP3-positive cells tended to decrease at 2 days after LPS exposure in the gut (P = 0.10) or in the lung (P = 0.14) (Fig. 2E). Remarkably, at 6 days after LPS infusion in the gastrointestinal tract, the number of FoxP3+ cells returned to control levels in the gut group, whereas these cells remained decreased in the ileum after 6 days of LPS infusion in the “6 day lung” group (P = 0.09) (Fig. 2F). Intra-amniotic endotoxin exposure for 2 days resulted in a significant decrease of FoxP3-expressing cells (Fig. 2E) that normalized within 6 days after IA endotoxin injection (Fig. 2F). The number of ileal FoxP3+ cells in the “IA LPS Ocln” group remained unchanged compared with saline-treated control animals at 2 and 6 days (Fig. 2, E and F).

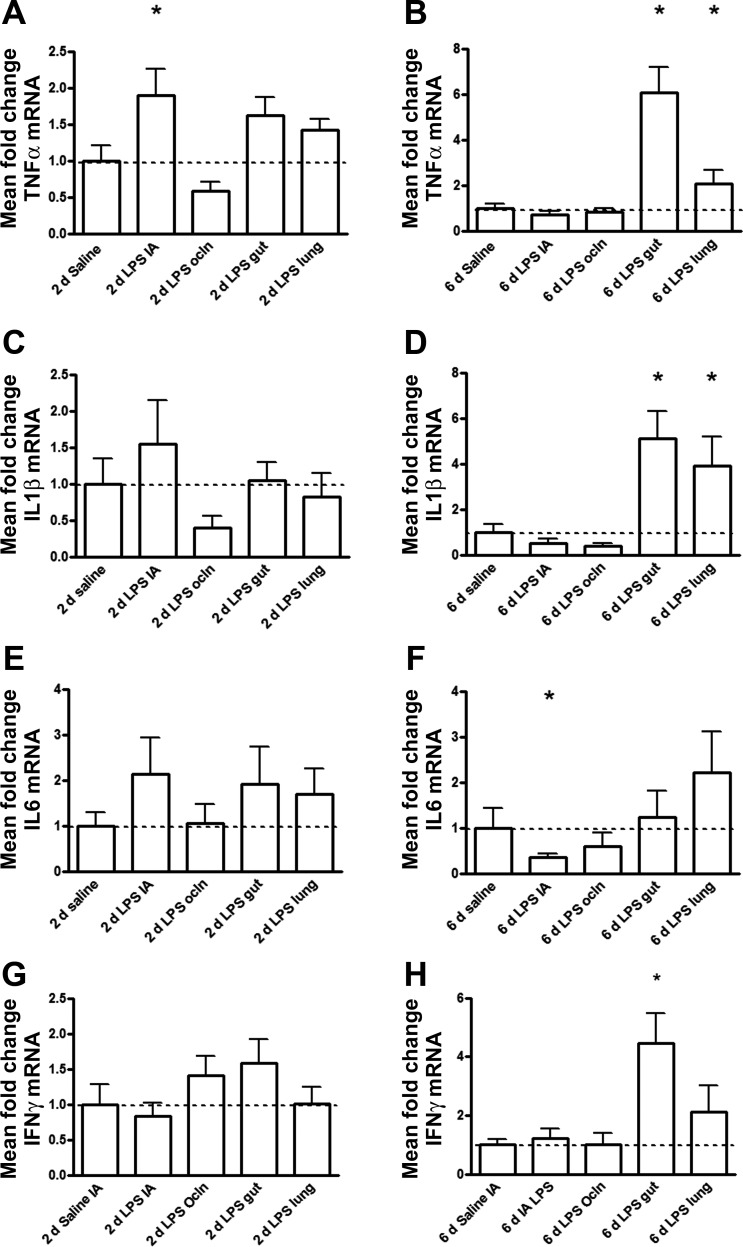

Compared with controls, increased ileal tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α mRNA levels were only detected in the IA LPS group (Fig. 3A), whereas IL-1β, IL-6, and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) mRNA did not increase in any of the 2-day exposure groups (Fig. 3, C, E, and G). TNF-α, IL-1β, and IFN-γ mRNA levels in the fetal ileum increased after selective gut LPS exposure for 6 days (Fig. 3, B, D, and H). In contrast to the responses after selective gut exposure, only a modest increase of TNF-α and IL-1β in the fetal ileum after 6 days of intratracheal LPS infusion was seen (Fig. 3B), whereas no significant increase for IFN-γ mRNA levels was detected (Fig. 3D). Compared with controls, ileal IL-6 mRNA levels decreased after 6 days of IA LPS exposure with no change in the other 6-day LPS-exposed groups (Fig. 3F).

Fig. 3.

Quantitative real-time PCR assays in the fetal ileum using ovine-specific primers and Taqman probes. The values for tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α (A and B), IL-1β (C and D), IL-6 (E and F), and interferon (IFN)-γ (G and H) were normalized to 18S rRNA, and groups were compared with the Mann-Whitney test. The mean mRNA signal in controls was assigned to a value of 1. Mean fold changes in mRNA expression of all other experimental groups were expressed relative to controls. *P < 0.05 vs. control using a Mann-Whitney nonparametric U-test.

Consistent with the other inflammatory indicators, no significant changes in either TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, or IFN-γ mRNA levels were measured in the fetal ileum in the IA Ocln group compared with the controls (Fig. 3, A–D).

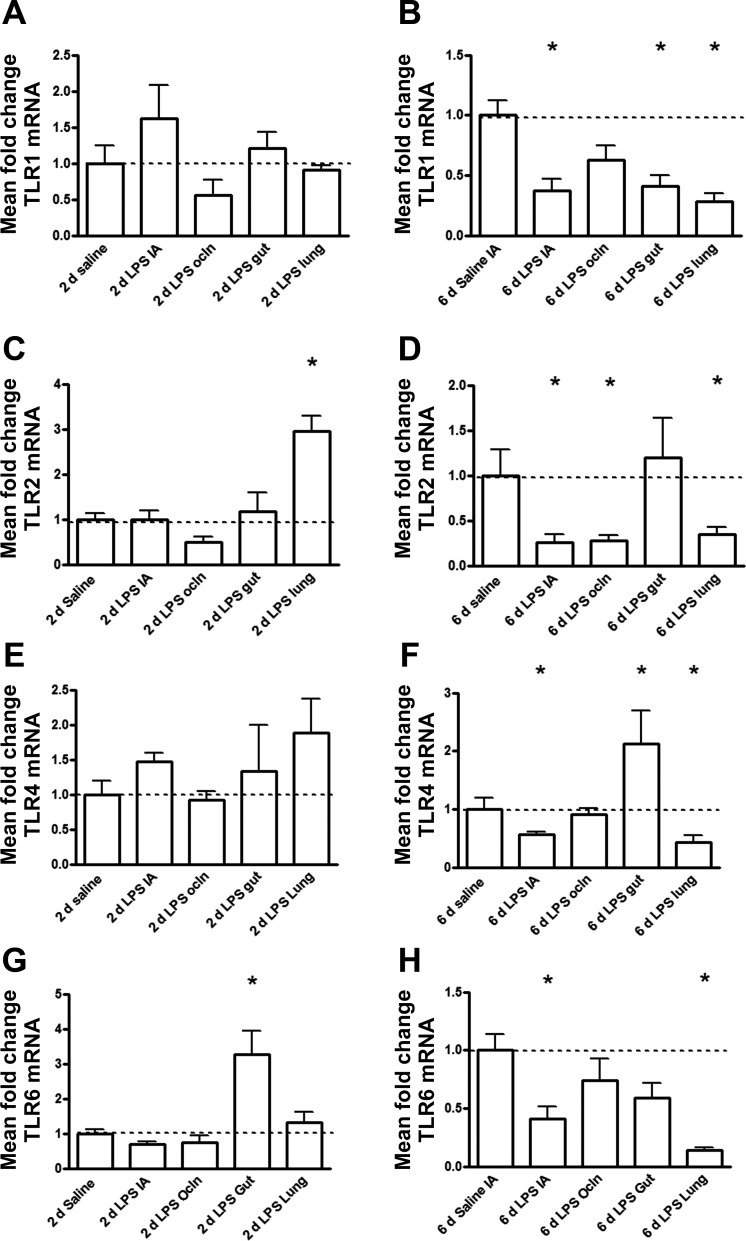

TLRs in the Fetal Ileum Are Differently Regulated after Intratracheal or Gastrointestinal LPS Exposure

Ileal TLR1 mRNA levels did not change after 2-day exposures in any group (Fig. 4A). However, compared with age-matched saline-treated animals, ileal TLR1 mRNA expression decreased after 6 days of selective LPS exposure to the gut, the lung, or the amniotic cavity but not in the IA Ocln group (Fig. 4B). Time-dependent changes of TLR1 mRNA between days 2 and 6 were significantly different (Table 2). TLR1 mRNA levels in the fetal ileum decreased at 6 days of exposure in the “IA,” gut, and lung LPS groups.

Fig. 4.

Quantitative real-time PCR mRNA expression levels of Toll-like receptors (TLRs) in the fetal ileum using sheep-specific primers and Taqman probes. TLR mRNA values were normalized to 18S rRNA, and groups were compared with the Mann-Whitney test. The mean mRNA signal in controls was set to 1, and levels at each time point were expressed in a relative manner. *P < 0.05 vs. control using a Mann-Whitney nonparametric U-test.

Table 2.

Relative TLR mRNA changes in the fetal ileum between the 2- and 6-day post-LPS treatment groups for each surgical group

| LPS IA 2 vs. 6 Days | LPS Ocln 2 vs. 6 Days | LPS Gut 2 vs. 6 Days | LPS Lung 2 vs. 6 Days | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TLR1 mRNA | <0.05 | NS | <0.05 | <0.05 |

| TLR2 mRNA | <0.05 | NS | NS | <0.001 |

| TLR4 mRNA | <0.05 | NS | NS | <0.05 |

| TLR6 mRNA | <0.05 | NS | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Data are P values. TLR, Toll-like receptor. Time-dependent TLR changes were analyzed by a two-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni post hoc test. NS, not significant.

Gut TLR2 mRNA levels in the fetal ileum selectively increased at 2 days of LPS exposure to the lung (Fig. 4C) and decreased after 6 days of lung, IA, or IA Ocln exposure compared with matched saline-treated animals (Fig. 4D). In contrast, ileal TLR2 mRNA levels remained unaltered after 2 or 6 days of selective LPS exposure to the gut (Fig. 4, C and D). Ileal TLR2 mRNA levels significantly decreased between 2 and 6 days of endotoxin exposure in the IA and lung LPS groups (Table 2). Compared with age-matched saline-treated animals, ileal TLR4 mRNA increased after 6 days of selective LPS exposure to the gut but decreased after 6 days of selective IA or lung LPS exposure with no change in the IA Ocln group (Fig. 4F). Time-dependent changes in the fetal ileum of TLR4 mRNA between days 2 and 6 were significantly different (Table 2). TLR4 mRNA levels decreased at 6 days of exposure in the gut and lung LPS groups.

TLR6 mRNA in the fetal ileum increased after 2 days of selective LPS exposure to the gut compared with age-matched control animals (Fig. 4G). Compared with all groups, ileal TLR6 mRNA levels were reduced at 6 days after intra-amniotic or intratracheal injection of LPS (Fig. 4H). Time-dependent changes of TLR6 mRNA in the fetal ileum between days 2 and 6 were significantly different (Table 2). TLR6 mRNA levels decreased at 6 days of exposure in the IA, gut, and lung LPS groups.

Intestinal Epithelial Differentiation and Proliferation

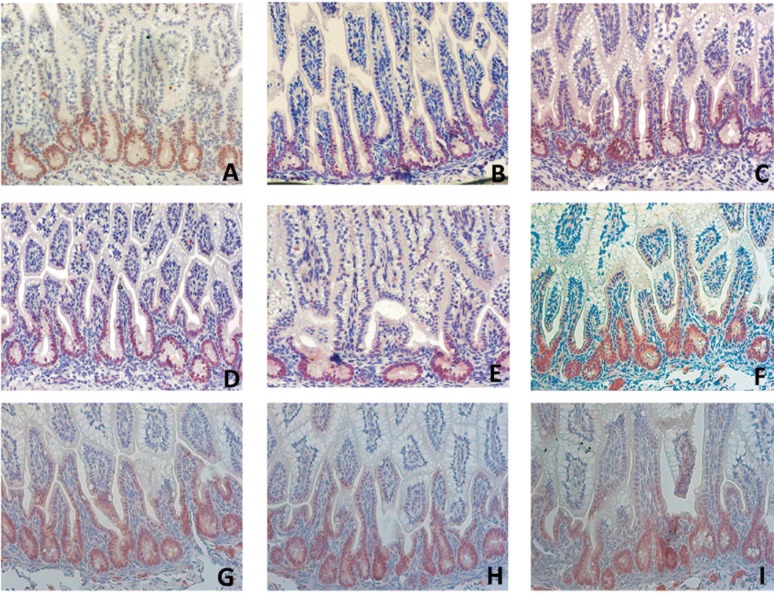

We stained ileal tissue for KLF5 to gain insight into whether selective LPS exposure was associated with impaired proliferation and migration of intestinal epithelial cells (Fig. 5, A–I). KLF5 regulates mucosal healing through its effects on epithelial proliferation, differentiation, and cell positioning along the crypt radial axis (23). Consistent with previous reports, constitutive KLF5 expression was high in intestinal epithelial cells located in the lower to middle crypt region (9). The number of KLF5+ cells was only reduced after selective endotoxin exposure of the lung for 2 days (Fig. 5E). In these animals, KLF5 expression was restricted to the bottom of the crypts (Fig. 5E).

Fig. 5.

For each experimental group, the ileal distribution of Kruppel-like factor 5-positive (KLF5+) cells was analyzed by immunohistochemistry. Compared with control animals (A), reduced KLF5+ cell numbers were observed in fetuses of the “2-day LPS lung” group (E). The distribution of KLF5+ cells in the “2-day LPS IA” (B), “2-day LPS Ocln” (C), “2-day LPS gut” (D), “6-day LPS IA” (F), “6-day LPS Ocln” (G), “6-day LPS gut” (H), and “6-day LPS lung” (I) LPS groups did not change. Magnification ×200.

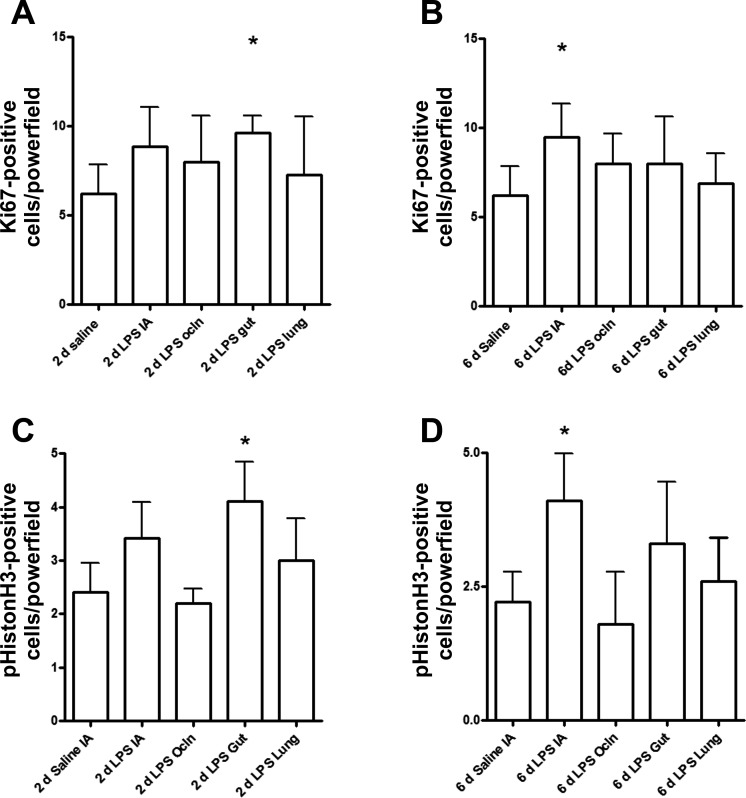

To determine whether the reduced number of KLF5-expressing enterocytes was paralleled by changes in cell proliferation, we evaluated Ki67 and pHistone-H3 by immunohistochemical staining. The number of proliferating and mitotic cells in the fetal ileum increased after selective gut exposure to endotoxin for 2 days compared with control animals (Fig. 6, A and B). Consistent with the reduced number of KLF5+ cells, proliferating cell numbers did not increase after selective infusion of LPS in the lung (Fig. 6, A and B). Interestingly, increased proliferation was seen after 6 days intra-amniotic LPS (Fig. 6, C and D). However, the number of proliferating and mitotic cells remained unchanged in the IA LPS Ocln group compared with saline-treated control animals (Fig. 6, C and D). Importantly, the increase of proliferating cells in the fetal ileum after selective gut exposure to LPS for 2 days and intra-amniotic LPS exposure for 6 days did not result in significant changes of the villus lengths compared with the other groups (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

The numbers of proliferating and mitotic cells in the fetal ileum were measured by an immunohistochemical staining for Ki67 and phospho-histone H3 (pHistoneH3), respectively. Gut exposure to LPS for 2 days increased the number of Ki67- and phospho-histone H3-positive cells (A and B). Compared with controls, intra-amniotic LPS exposure for 6 days resulted in increased Ki67 and phospho-histone H3-positive cells (C and D). Groups were compared with the Mann-Whitney test. *P < 0.05 vs. control using a Mann-Whitney nonparametric U-test.

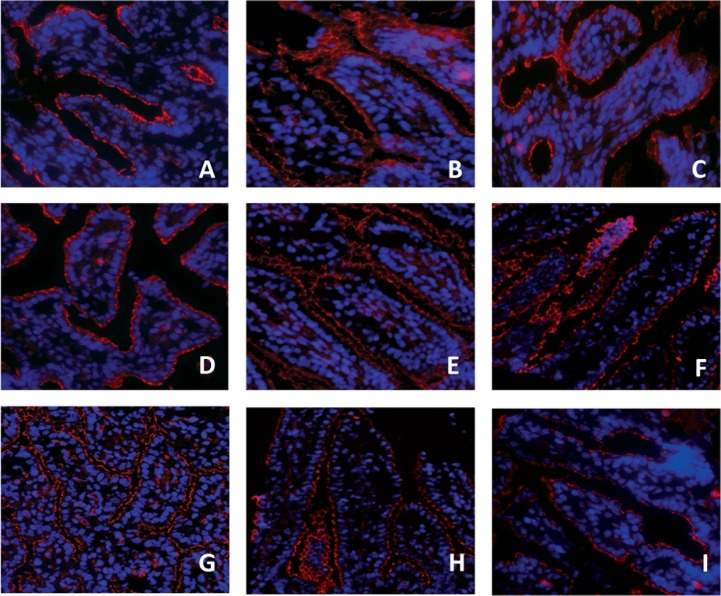

Gut Wall Integrity Loss Following Selective Local Gut or Pulmonary LPS Exposure

Consistent with our previous reports in preterm sheep fetuses (38, 40), the epithelial tight junction protein ZO-1 staining was fragmented in premature saline-treated control animals of 125 days GA (Fig. 7A). This pattern remained unchanged after 2 days of LPS exposure in all surgical groups (Fig. 7, B–E). In contrast, fetuses selectively exposed to LPS for 6 days in the gut, the lung, or amniotic cavity had a further fragmented tight junctional distribution with the most severe disturbance in the intra-amniotic and gut-exposed groups (Fig. 7, F–I). The ZO-1 distribution was not changed in the IA LPS Ocln group compared with saline-treated control animals (Fig. 7I).

Fig. 7.

Zonula occludens protein 1 (ZO-1) distribution was assessed in fetal ileal tissue using an immunofluorescent staining. A fragmented ZO-1 staining was observed in premature saline-treated control animals (A) and in lambs from the “2-day IA LPS” (B), 2-day LPS Ocln (C), 2-day LPS gut (D), or 2-day LPS lung (E) groups. ZO-1 distribution was even more disturbed in the 6-day LPS IA (F), 6-day LPS gut (H), and 6-day LPS lung (I) groups. The ZO-1 distribution pattern in the 6-day LPS Ocln group (G) was comparable to saline-treated control animals (A). Magnification ×200.

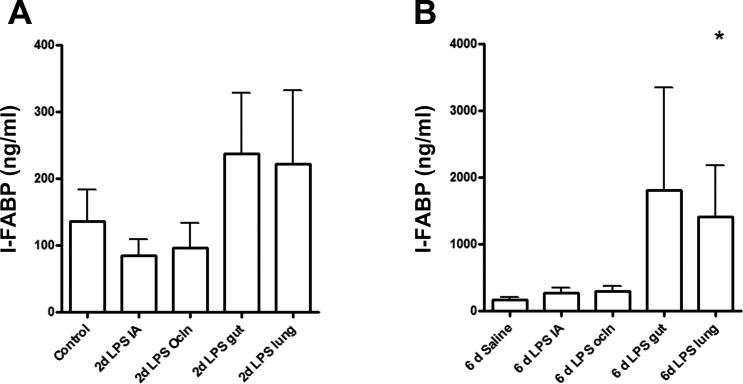

Mucosal damage was further assessed by circulating I-FABP levels, since this cytosolic protein is present in enterocytes and rapidly released in the systemic circulation upon cell damage (5). The concentration of I-FABP in the fetal circulation was significantly elevated (P < 0.05) only in 6-day LPS lung-exposed animals compared with saline controls (Fig. 8B), and there was no change in any of the 2-day groups (Fig. 8A).

Fig. 8.

Circulating intestinal fatty acid-binding protein (I-FABP) levels were measured by ELISA, and groups were compared with the Mann-Whitney test. I-FABP plasma levels did not change after exposure to LPS for 2 days in each experimental group (A). Lung exposure to LPS for 6 days significantly increased I-FABP plasma levels (B). *P < 0.05 vs. control using a Mann-Whitney nonparametric U-test.

DISCUSSION

The pathways to gut inflammation and postnatal intestinal pathologies in preterm infants following exposure to chorioamnionitis are unknown. We previously reported that proinflammatory agonists in the amniotic cavity induce fetal gut inflammation and an injury response (38–40). We demonstrate in this study that LPS infusion in the amniotic cavity and selective infusion of LPS in the gut induced fetal gut inflammation and mucosal injury. This response is consistent with an inflammatory reaction induced by direct contact between LPS and gut epithelium. We report the unanticipated novel finding that selective LPS exposure in the fetal lung also resulted in fetal gut inflammation and subsequent mucosal injury, which is not the result of direct LPS contact with the gut epithelium or systemic translocation of LPS in the blood. Interestingly, when fetal swallowing was abolished by snout occlusion, amniotic infusion of LPS did not result in gut inflammation or injury. Therefore, our experiments demonstrated that the gut responses to chorioamnionitis require either contact of the proinflammatory agonist to the gastrointestinal mucosa or the lung epithelium.

The gut inflammation/injury in our experiments occurred because of local effects of LPS, since LPS was not detected in the plasma after infusion in any of the fetal compartments. This is in line with previous results demonstrating that 1–5 μg of LPS given intravascularly causes profound hypotension in preterm sheep (11, 12a), but doses of up to 100 mg LPS given intra-amniotically (>10,000-fold higher dose) are tolerated without hypotension (18). Taken together, these results strongly suggest that the IA LPS does not cross into the systemic circulation.

Gut inflammation induced by LPS selectively infused in different fetal compartments was qualitatively different with distinct temporal patterns. The response of the fetal gut after tracheal LPS infusion could be clearly distinguished from the intestinal response after LPS exposure of the gastrointestinal tract by the lymphocyte influx and the high ileal TNF-α and IFN-γ mRNA levels in the “LPS-gut” animals. This different pattern suggests that the inflammatory response of the fetal gut differs depending on the site of the inflammatory stimulus and the origin of the activated immune cells (33, 36).

This is consistent with earlier findings showing that resident and circulating cells that orchestrate the inflammatory response of the fetal gut will be different depending on the origin of the inflammatory process. Such involvement of other immune cells could result in a different TLR repertoire expression and concomitant innate immune sensing (19). In keeping with these reports, the levels of TLR mRNAs in the fetal gut following LPS exposure to the gut or the lung were different in our study. CD3+ cells and MPO+ cells increased 6 days after selective LPS exposure to the gut, lung, or amniotic cavity. However, a more detailed analysis of the CD3+ cells and the FoxP3-positive Treg cells might reveal differences in subsets of lymphocytes based on site of origin of proinflammatory stimulus. In addition, a functional analysis of lamina propria located CD4+ CD25high CD127low Treg cells would be ideal to determine the immunosuppressive capacity of these cells. Unfortunately, such experiments are hampered by a lack of suitable antibodies for sheep.

Another reason for the observed differences of the inflammatory characteristics could be the timing of the onset of the inflammatory process. We previously reported that LPS exposure of the fetal lung induced a rapid local and systemic inflammatory response within hours after exposure (27), whereas amniotic LPS exposure did not induce gut inflammation within 48 h (38).

The relatively high levels of TNF-α and IFN-γ after direct LPS exposure were paralleled by severe loss of ZO-1 in the fetal ileum, whereas a slight increase of TNF-α and IFN-γ mRNA such as detected in the “lung LPS” fetuses was associated with a milder loss of ZO-1 in the fetal gut. Consistent with these observations, this tight junctional protein that has a crucial role in paracellular barrier sealing was previously shown to be disrupted by both proinflammatory cytokines (7). Remarkably, loss in epithelial cell integrity, as indicated by increased plasma I-FABP levels, was only observed in pulmonary LPS-exposed fetuses but not after direct LPS contact with the fetal gut. These findings indicate that LPS exposure of the fetal lung or direct gut exposure to LPS via amniotic fluid swallowing results in different characteristics of gut inflammation that determine the level of epithelial and or tight junctional integrity loss.

In this study, we demonstrated that LPS exposure to the fetal gut resulted in increased mitosis of cells in the intestinal mucosa. Our findings are supported by data from germ-free animals and in vitro experiments showing that mitosis and proliferation of intestinal epithelial cells are substantially increased following exposure to bacteria (2, 35) or LPS in particular (31).

Despite the inflammatory and injury response in the fetal gut after lung LPS exposure, there were no changes in the number of proliferating cells in the crypts in this group compared with the controls. The altered distribution of the proproliferative regulator KLF5 could be a mechanistic explanation for the apparent lack of increased mitosis after pulmonary LPS exposure, since the number of cells expressing KLF5 become restricted to the lowest crypt region within 2 days after pulmonary LPS exposure. However, because KLF5 is known to be regulated in response to stress stimuli such as tissue damage or LPS exposure (8, 29), it remains unclear why the distribution of KLF5 in the fetal intestine is specifically influenced following intratracheal LPS instillation and not after intestinal LPS exposure.

Because preterm fetal sheep have an inadequate gut barrier, LPS translocation and systemic inflammation might be expected to occur after gut exposure to LPS. However, no endotoxin could be detected in the plasma following gastrointestinal LPS delivery. Consistently, in the current study and in a recent report from Kemp et al., selective gut exposure to LPS only results in a mild systemic response as shown by modestly increased circulating haptoglobin and amyloid A3 levels (24). Importantly, despite the increase of these acute phase proteins, no other systemic inflammatory markers, including monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP)-1, IL-6, and IL-8, were detected in the Kemp et al. study. Based on these combined findings, it is unlikely that a gastrointestinal-mediated systemic reaction could be responsible for the detrimental inflammatory response of the fetal gut.

The systemic inflammatory response of the fetus, induced by lung or chorioamnion/cutaneous LPS exposure, was more prominent compared with the mild systemic effects following LPS delivery in the gastrointestinal tract. Pulmonary or amniotic LPS but not gastrointestinal tract LPS induced leucocytosis, neutrophilia, and elevated circulatory MCP-1 levels and inflammation of the fetal liver and spleen (24).

Interestingly, the systemic inflammatory response of the fetus following LPS exposure of the fetal skin/amniotic compartment (IA Ocln group) did not provoke an inflammatory response and adverse outcomes of the fetal gut. Furthermore, Kemp et al. showed that systemic inflammation after fetal skin/amnion exposure did not result in fetal lung inflammation, indicating that exposure of the skin/amnion did not result in a multiorgan systemic fetal inflammatory response (24).

The mechanisms by which pulmonary LPS exposure causes changes of the fetal intestine are thus not clear. We speculate that the lymphatics mediate the effects since the lymphatic channels between the gut and the lung communicate. In this regard, we previously demonstrated that the posterior mediastinal lymph node responds with a doubling of weight and increased trafficking of activated neutrophils and monocytes as a result of intrauterine lung inflammation (20). We recently demonstrated that IA LPS injection decreased Tregs and increased IL-17-producing cells in the posterior mediastinal lymph node of fetal rhesus macaques (22). Interestingly, these profound changes in the local lymph nodes were not paralleled by changes in the blood cells, showing compartmentalization of the FIRS responses after chorioamnionitis. These results highlight the peculiar characteristics of the fetal immune response in FIRS and provide a better understanding of the higher rate of severe neonatal morbidity such as necrotizing enterocolitis after chorioamnionitis (1, 14).

In summary, our findings suggest that the detrimental consequences of chorioamnionitis on fetal gut development (38, 40) are the combined result of local gut-derived and pulmonary-driven systemic inflammatory responses. Moreover, the distinct inflammatory responses in the fetal gut following indirect or direct LPS exposure interfere with different segments of the developing fetal intestine. This study contributes to an understanding of the mechanisms of local and compartment-specific systemic inflammation and organ injury responses after chorioamnionitis.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant HD-57869 (to S. G. Kallapur), the Ter Meulen Fund of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (to T. G. A. M. Wolfs) and the Research School for Oncology and Developmental Biology (GROW), Maastricht University.

DISCLOSURES

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: T.G.W., B.W.K., M.W.K., J.P.N., A.H.J., and S.G.K. conception and design of research; T.G.W., G.T., M.W.K., M.S., M.G.W., and P.S.-K. performed experiments; T.G.W. and G.T. analyzed data; T.G.W., G.T., A.H.J., and S.G.K. interpreted results of experiments; T.G.W. prepared figures; T.G.W. and G.T. drafted manuscript; T.G.W., B.W.K., A.H.J., and S.G.K. approved final version of manuscript; B.W.K., A.H.J., and S.G.K. edited and revised manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for the technical assistance of Leon Janssen, Irma Tindemans (UM), Megan McAuliffe and Manuel Alvarez (CCHMC).

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams-Chapman I. Long-term impact of infection on the preterm neonate. Semin Perinatol 36: 462–470, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alam M, Midtvedt T, Uribe A. Differential cell kinetics in the ileum and colon of germfree rats. Scand J Gastroenterol 29: 445–451, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrews WW, Goldenberg RL, Faye-Petersen O, Cliver S, Goepfert AR, Hauth JC. The Alabama Preterm Birth study: polymorphonuclear and mononuclear cell placental infiltrations, other markers of inflammation, and outcomes in 23- to 32-week preterm newborn infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol 195: 803–808, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Been JV, Lievense S, Zimmermann LJ, Kramer BW, Wolfs TG. Chorioamnionitis as a risk factor for necrotizing enterocolitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pediatr 162: 236–242, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beuk RJ, Heineman E, Tangelder GJ, Quaedackers JS, Marks WH, Lieberman JM, oude Egbrink MG. Total warm ischemia and reperfusion impairs flow in all rat gut layers but increases leukocyte-vessel wall interactions in the submucosa only. Ann Surg 231: 96–104, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burd I, Balakrishnan B, Kannan S. Models of fetal brain injury, intrauterine inflammation, and preterm birth. Am J Reprod Immunol 67: 287–294, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Capaldo CT, Nusrat A. Cytokine regulation of tight junctions. Biochim Biophys Acta 1788: 864–871, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chanchevalap S, Nandan MO, McConnell BB, Charrier L, Merlin D, Katz JP, Yang VW. Kruppel-like factor 5 is an important mediator for lipopolysaccharide-induced proinflammatory response in intestinal epithelial cells. Nucleic Acids Res 34: 1216–1223, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conkright MD, Wani MA, Anderson KP, Lingrel JB. A gene encoding an intestinal-enriched member of the Kruppel-like factor family expressed in intestinal epithelial cells. Nucleic Acids Res 27: 1263–1270, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dello SA, Reisinger KW, van Dam RM, Bemelmans MH, van Kuppevelt TH, van den Broek MA, Olde Damink SW, Poeze M, Buurman WA, Dejong CH. Total intermittent Pringle maneuver during liver resection can induce intestinal epithelial cell damage and endotoxemia. PLoS One 7: e30539, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duncan JR, Cock ML, Scheerlinck JP, Westcott KT, McLean C, Harding R, Rees SM. White matter injury after repeated endotoxin exposure in the preterm ovine fetus. Pediatr Res 52: 941–949, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol 4: 330–336, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12a.Gisslen T, Hillman NH, Musk GC, Kemp MW, Kramer BW, Senthamaraikannan P, Newnham JP, Jobe AH, Kallapur SG. Repeated exposures to intra-amniotic LPS partially protects against adverse effects of intravenous LPS in preterm lambs. Innate Immun 20: 214–224, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldenberg RL, Hauth JC, Andrews WW. Intrauterine infection and preterm delivery. N Engl J Med 342: 1500–1507, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gomez R, Romero R, Ghezzi F, Yoon BH, Mazor M, Berry SM. The fetal inflammatory response syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 179: 194–202, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hartling L, Liang Y, Lacaze-Masmonteil T. Chorioamnionitis as a risk factor for bronchopulmonary dysplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis 97: F8–F17, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science 299: 1057–1061, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huntoon KM, Wang Y, Eppolito CA, Barbour KW, Berger FG, Shrikant PA, Baumann H. The acute phase protein haptoglobin regulates host immunity. J Leukocyte Biol 84: 170–181, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jobe AH, Newnham JP, Willet KE, Moss TJ, Gore Ervin M, Padbury JF, Sly P, Ikegami M. Endotoxin-induced lung maturation in preterm lambs is not mediated by cortisol. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 162: 1656–1661, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kadowaki N, Ho S, Antonenko S, Malefyt RW, Kastelein RA, Bazan F, Liu YJ. Subsets of human dendritic cell precursors express different toll-like receptors and respond to different microbial antigens. J Exp Med 194: 863–869, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kallapur SG, Kramer BW, Nitsos I, Pillow JJ, Collins JJ, Polglase GR, Newnham JP, Jobe AH. Pulmonary and systemic inflammatory responses to intra-amniotic IL-1α in fetal sheep. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 301: L285–L295, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kallapur SG, Nitsos I, Moss TJ, Polglase GR, Pillow JJ, Cheah FC, Kramer BW, Newnham JP, Ikegami M, Jobe AH. IL-1 mediates pulmonary and systemic inflammatory responses to chorioamnionitis induced by lipopolysaccharide. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 179: 955–961, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kallapur SG, Presicce P, Senthamaraikannan P, Alvarez M, Tarantal AF, Miller LM, Jobe AH, Chougnet CA. Intra-amniotic IL-1beta induces fetal inflammation in rhesus monkeys and alters the regulatory T cell/IL-17 balance. J Immunol 191: 1102–1109, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kallapur SG, Willet KE, Jobe AH, Ikegami M, Bachurski CJ. Intra-amniotic endotoxin: chorioamnionitis precedes lung maturation in preterm lambs. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 280: L527–L536, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kemp MW, Kannan PS, Saito M, Newnham JP, Cox T, Jobe AH, Kramer BW, Kallapur SG. Selective exposure of the fetal lung and skin/amnion (but not gastro-intestinal tract) to LPS elicits acute systemic inflammation in fetal sheep. PLoS One 8: e63355, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kemp MW, Saito M, Nitsos I, Jobe AH, Kallapur SG, Newnham JP. Exposure to in utero lipopolysaccharide induces inflammation in the fetal ovine skin. Reprod Sci 18: 88–98, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kramer BW, Kallapur SG, Moss TJ, Nitsos I, Polglase GP, Newnham JP, Jobe AH. Modulation of fetal inflammatory response on exposure to lipopolysaccharide by chorioamnion, lung, or gut in sheep. Am J Obstet Gynecol 202: 77 e71–e79, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kramer BW, Moss TJ, Willet KE, Newnham JP, Sly PD, Kallapur SG, Ikegami M, Jobe AH. Dose and time response after intraamniotic endotoxin in preterm lambs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 164: 982–988, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larsen B, Hwang J. Mycoplasma, ureaplasma, and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a fresh look. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2010: 521921, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McConnell BB, Ghaleb AM, Nandan MO, Yang VW. The diverse functions of Kruppel-like factors 4 and 5 in epithelial biology and pathobiology. Bioessays 29: 549–557, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oh KJ, Lee KA, Sohn YK, Park CW, Hong JS, Romero R, Yoon BH. Intraamniotic infection with genital mycoplasmas exhibits a more intense inflammatory response than intraamniotic infection with other microorganisms in patients with preterm premature rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 203: 211 e211–e218, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olaya J, Neopikhanov V, Uribe A. Lipopolysaccharide of Escherichia coli, polyamines, and acetic acid stimulate cell proliferation in intestinal epithelial cells. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 35: 43–48, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shatrov JG, Birch SC, Lam LT, Quinlivan JA, McIntyre S, Mendz GL. Chorioamnionitis and cerebral palsy: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol 116: 387–392, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith PD, Smythies LE, Shen R, Greenwell-Wild T, Gliozzi M, Wahl SM. Intestinal macrophages and response to microbial encroachment. Mucosal Immunol 4: 31–42, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Speer CP. Inflammation and bronchopulmonary dysplasia: a continuing story. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 11: 354–362, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uribe A, Alam M, Midtvedt T, Smedfors B, Theodorsson E. Endogenous prostaglandins and microflora modulate DNA synthesis and neuroendocrine peptides in the rat gastrointestinal tract. Scand J Gastroenterol 32: 691–699, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Varol C, Zigmond E, Jung S. Securing the immune tightrope: mononuclear phagocytes in the intestinal lamina propria. Nat Rev Immunol 10: 415–426, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Viscardi RM, Muhumuza CK, Rodriguez A, Fairchild KD, Sun CC, Gross GW, Campbell AB, Wilson PD, Hester L, Hasday JD. Inflammatory markers in intrauterine and fetal blood and cerebrospinal fluid compartments are associated with adverse pulmonary and neurologic outcomes in preterm infants. Pediatr Res 55: 1009–1017, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wolfs TG, Buurman WA, Zoer B, Moonen RM, Derikx JP, Thuijls G, Villamor E, Gantert M, Garnier Y, Zimmermann LJ, Kramer BW. Endotoxin induced chorioamnionitis prevents intestinal development during gestation in fetal sheep. PLoS One 4: e5837, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolfs TG, Kallapur SG, Knox CL, Thuijls G, Nitsos I, Polglase GR, Collins JJ, Kroon E, Spierings J, Shroyer NF, Newnham JP, Jobe AH, Kramer BW. Antenatal ureaplasma infection impairs development of the fetal ovine gut in an IL-1-dependent manner. Mucosal Immunol 6: 547–556, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wolfs TG, Kallapur SG, Polglase GR, Pillow JJ, Nitsos I, Newnham JP, Chougnet CA, Kroon E, Spierings J, Willems CH, Jobe AH, Kramer BW. IL-1alpha mediated chorioamnionitis induces depletion of FoxP3+ cells and ileal inflammation in the ovine fetal gut. PLoS One 6: e18355, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang L, Saito M, Jobe A, Kallapur SG, Newnham JP, Cox T, Kramer B, Yang H, Kemp MW. Intra-amniotic administration of E coli lipopolysaccharides causes sustained inflammation of the fetal skin in sheep. Reprod Sci 19: 1181–1189, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]