Abstract

We examined whether CB1 receptors in smooth muscle conform to the signaling pattern observed with other Gi-coupled receptors that stimulate contraction via two Gβγ-dependent pathways (PLC-β3 and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/integrin-linked kinase). Here we show that the anticipated Gβγ-dependent signaling was abrogated. Except for inhibition of adenylyl cyclase via Gαi, signaling resulted from Gβγ-independent phosphorylation of CB1 receptors by GRK5, recruitment of β-arrestin1/2, and activation of ERK1/2 and Src kinase. Neither uncoupling of CB1 receptors from Gi by pertussis toxin (PTx) or Gi minigene nor expression of a Gβγ-scavenging peptide had any effect on ERK1/2 activity. The latter was abolished in muscle cells expressing β-arrestin1/2 siRNA. CB1 receptor internalization and both ERK1/2 and Src kinase activities were abolished in cells expressing kinase-deficient GRK5(K215R). Activation of ERK1/2 and Src kinase endowed CB1 receptors with the ability to inhibit concurrent contractile activity. We identified a consensus sequence (102KSPSKLSP109) for phosphorylation of RGS4 by ERK1/2 and showed that expression of a RGS4 mutant lacking Ser103/Ser108 blocked the ability of anandamide to inhibit acetylcholine-mediated phosphoinositide hydrolysis or enhance Gαq:RGS4 association and inactivation of Gαq. Activation of Src kinase by anandamide enhanced both myosin phosphatase RhoA-interacting protein (M-RIP):RhoA and M-RIP:MYPT1 association and inhibited Rho kinase activity, leading to increase of myosin light chain (MLC) phosphatase activity and inhibition of sustained muscle contraction. Thus, unlike other Gi-coupled receptors in smooth muscle, CB1 receptors did not engage Gβγ but signaled via GRK5/β-arrestin activation of ERK1/2 and Src kinase: ERK1/2 accelerated inactivation of Gαq by RGS4, and Src kinase enhanced MLC phosphatase activity, leading to inhibition of ACh-stimulated contraction.

Keywords: beta arrestin, CB1 receptors, ERK1/2, GRK5, Src kinase

the properties and role of G protein-coupled cannabinoid receptors, CB1 and CB2, have been extensively studied in their primary locations: the central and peripheral nervous system and the immune system, respectively (3, 8, 22, 32). The location of CB1 receptors in the brain (cerebral cortex, hippocampus, basal ganglia, amygdala, and cerebellum) correlates with the observed psychotropic effects of cannabinoids. It is increasingly evident, however, that CB1 receptors and the endocannabinoid system that provides them with lipid ligands on demand are more widely distributed, though less abundantly than in neural tissue. Thus CB1 receptors are expressed in both vascular and visceral smooth muscle [e.g., cerebral arterial smooth muscle (7), vas deferens (5), and myometrial smooth muscle (2)], where they signal variously via Gαi-dependent inhibition of adenylyl cyclase and Gβγ-dependent inhibition of voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channels, and activation of various kinases [phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI 3-kinase), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK1/2), and Src kinase].

In the present study, we examined signaling by Gi-coupled CB1 receptors in gastric smooth muscle cells, a model system used extensively to examine signaling by G protein-coupled receptors (16, 20). Earlier studies had shown that receptors coupled to Gi1 (e.g., opioid μ, δ, κ) (19), Gi2 (e.g., somatostatin sstr3) (17), or Gi3 (e.g., adenosine A1) (18) induce contraction by activating dual pathways initiated by Gβγ: the first involves activation of PLC-β3, stimulation of IP3-dependent Ca2+ release, and phosphorylation of myosin light chain (MLC) 20 (MLC20) by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent MLC kinase, resulting in a transient initial muscle contraction. The second pathway involves sequential activation of PI 3-kinase and integrin-linked kinase: the latter acts as a Ca2+-independent MLC kinase and inhibits MLC phosphatase by activating CPI-17 (PKC-potentiated inhibitor 17-kDa protein), an endogenous inhibitor of the catalytic PP1cδ subunit of MLC phosphatase (10). The dual effects of integrin-linked kinase result in sustained MLC20 phosphorylation and muscle contraction. We wondered whether CB1 receptors would conform to the stimulatory pattern of signaling observed with other Gi-coupled receptors or trigger pathways that attenuate smooth muscle contraction, consistent with the inhibitory effect of CB1 receptors in other locations. Here we show that the expected activation of Gβγ-dependent pathways that lead to stimulation of contraction was abrogated. Except for inhibition of adenylyl cyclase via Gαi, signaling resulted from Gβγ-independent phosphorylation of CB1 receptors by GRK5, binding of β-arrestin to the phosphorylated receptors, and activation of ERK1/2 and Src kinase (26). Both ERK1/2 and Src kinase inhibited concurrent contraction stimulated by acetylcholine (ACh) by targeting specific steps in the pathways that mediate contraction: ERK1/2 via phosphorylation of RGS4 (regulator of G protein signaling) and rapid inactivation of Gαq.GTP, and Src kinase via enhanced association of RhoA and MYPT1 (myosin phosphatase targeting subunit) with M-RIP (myosin phosphatase RhoA-interacting protein), leading to increase in MLC phosphatase activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

N-arachidonylethanolamine (anandamide; AEA) was obtained from Sigma, St. Louis, MO; AM251, N6-cyclopentyl adenosine (CPA), and [D-Pen2,D-Pen5]enkephalin (DPDPE) were obtained from Tocris, Ellisville, MO; [125I]cAMP, [γ-32P]ATP, [35S]GTPγS, CP55940, and myo-[3H]inositol were from PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA; collagenase CLS type II and soybean trypsin inhibitor were from Worthington, Freehold, NJ; Western blotting, Dowex AG-1 × 8 resin (100–200 mesh in formate form), chromatography material and protein assay kit, 10% Tris·HCl Ready Gels were from Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA; antibodies to CB1 receptor (SC-10066), Gαq, Gαi1, Gαi2, Gαi3, Gα12, Gα13, Gαs, RGS4, MYPT1, M-RIP, RhoA, Src kinase, Rho kinase, ERK1/2 were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA and antibody to CB2 receptor (AB5640P) from Chemicon, Billerica, MA; myelin basic protein was from EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA; Y27632, PP2, PD98049, PTx, forskolin, cAMP were from Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA; RNAqueous kit was obtained from Ambion, Austin, TX; Effectene Transfection Reagent, QIAEXII Gel extraction kit and QIAprepSpin Miniprep kit were from Qiagen Sciences, Valencia, CA; PCR reagents were from SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase and TOPO TA Cloning Kit Dual Promoter were from Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY; EcoRI was from New England BioLabs; Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) was from Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA. All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma, St. Louis, MO.

Experimental animals.

New Zealand White rabbits (weight: 4–5 lbs) were purchased from RSI Biotechnology, Clemmons, NC. The rabbits were housed in the animal facility administered by the Division of Animal Resources, Virginia Commonwealth University, and maintained in a temperature-controlled environment with free access to food and water. The rabbits were euthanized by injection of Euthasol overdose (100 mg/kg); this and all other procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Virginia Commonwealth University.

Preparation of dispersed and cultured smooth muscle cells.

Smooth muscle cells were isolated from strips of circular muscle layer of rabbit stomach by sequential enzymatic digestion, filtration, and centrifugation as described in detail previously (17–19). Freshly dispersed muscle cells were suspended in a medium consisting of 120 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 2.6 mM KH2PO4, 2 mM CaCl2, 0.6 mM MgCl2, 25 mM HEPES, 14 mM glucose, and 2.1% Eagle's essential amino acid mixture (pH 7.4). In some experiments, smooth muscle cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum until they attained confluence; the cells were redispersed and passaged once for use in various studies (20).

Detection of cannabinoid receptor expression by PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from cultured gastric smooth muscle cells by treatment with RNaqueous reagent and contaminant genomic DNA removed by treatment with TURBO DNase as described previously (23). RNA (5 μg) was reversibly transcribed and amplified by PCR under standard conditions. Specific primers for rabbit CB1 and CB2 receptors were designed based on identical sequences in human, rat, and mouse cDNA. CB1: forward 5′ACATGGCATCCAAATTAGG3′ reverse 5′CAGTTTGAACAGAAACAC3′; CB2: forward 5′AGCTGACTTCCTGGCCAG3′ reverse 5′AGTCTTGGCCAACCTCAC3′. PCR products were purified and sequenced.

Detection of cannabinoid receptors by Western blot.

The expression of CB1 or CB2 receptors was determined by Western blot as described previously (23) by using homogenates prepared from freshly dispersed gastric smooth muscle cells. Proteins were resolved by 15% SDS-PAGE and electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were incubated for 12 h at 4°C with specific antibodies for CB1 or CB2 receptors and then for 1 h with secondary antibody. The bands were identified by enhanced chemiluminescence.

Binding of CB1 receptor agonist [3H]CP55,940 to muscle cells.

Cultured gastric smooth muscle cells were resuspended in HEPES medium containing 1% BSA, 10 μM amastatin, 1 μM phosphoramidon, and 0.7 mM bacitracin. Triplicate aliquots (0.3 ml) of cell suspension (106 cells/ml) were incubated for 60 min at 4°C with 50 pM [3H]CP55,940 alone or with 1 μM AEA. Bound and free radioligands were separated by rapid filtration through 5-μm polycarbonate nucleopore filters followed by washing with HEPES medium. Nonspecific binding (26 ± 5%) was determined as the amount of radioactivity associated with the muscle cells in the presence of 1 μM AEA.

Identification of G proteins coupled to CB1 receptors.

G proteins activated by AEA were identified by an adaptation of the method of Okamoto et al. (21, 34) as described previously. Homogenates of dispersed muscle cells were centrifuged at 30,000 g for 30 min at 4°C, and the membranes solubilized at 4°C in 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) buffer. Solubilized membranes were incubated for 20 min at 37°C with 100 nM [35S]GTPγS in 10 mM HEPES in the presence or absence of 1 μM AEA. The reaction was stopped and the membranes were reincubated for 2 h on ice in wells precoated with specific antibodies to Gαs, Gαq, Gαi1, Gαi2, and Gαi3. Radioactivity from each well was counted by liquid scintillation.

Transfection of GRK2, GRK5, and RGS4 mutants and β-arrestin1 and -2 siRNA into cultured smooth muscle cells.

Wild-type GRK2, GRK5, RGS4, kinase-deficient GRK2(K220R) and GRK5(K215R), phosphorylation-deficient RGS4(S103A/S108A), and β-arrestin1 and -2 siRNA were subcloned into the multiple cloning site (EcoRI) of the eukaryotic expression vector pcDNA3. Recombinant plasmid cDNAs were transiently transfected into smooth muscle cultures for 48 h. The cells were cotransfected with 2 μg pcDNA3 vector and 1 μg of pGreen Lantern-1 DNA to monitor transfection efficiency (23).

Cannabinoid receptor phosphorylation.

Phosphorylation of CB1 receptor was determined from the amount of 32P incorporated after immunoprecipitation with specific antibody for CB1 receptor. Cultured muscle cells were transfected with control vector or vector containing kinase-deficient GRK5(K215R) in wells containing 2 × 106 cells and labeled with 0.5 μCi/ml of [32P]orthophosphate for 3 h. The cells were then treated with or without 1 μM AEA for 15 min. The reaction was terminated with an equal volume of lysis buffer (final concentrations: 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% SDS, 0.75% deoxycholate, 10 mM EDTA, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 100 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 mM Na2P2O7, 50 mM NaF, 0.2 mM Na3VO4) and placed on ice for 30 min. Cell lysates were separated by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. The lysates were incubated with CB1 receptor antibody for 2 h at room temperature, and then overnight at 4°C after addition of 25 μl of Protein A/G plus agarose. The immunoprecipitates were washed with lysis buffer, extracted by boiling with Laemmli buffer for 15 min, and separated by SDS gel electrophoresis. 32P-labeled CB1 receptor was visualized by autoradiography (15).

Protein:protein association (M-RIP:RhoA, M-RIP:MYPT1, and Gαq:RGS4).

Sequential immunoprecipitation and immunoblot with selective antibodies were used to determine the association of M-RIP with RhoA and MYPT1. Dispersed or cultured muscle cells were treated with 1 μM AEA, 0.1 μM ACh, or a combination of AEA and ACh for 5 min. In some experiments, the cells were treated in the same fashion in the presence of the Src kinase inhibitor PP2 (1 μM) or the CB1 receptor antagonist AM251 (1 μM). For Gαq:RGS4 association, the cells were treated with 1 μM AEA and 0.1 μM ACh or a combination of AEA and ACh for 30 s.

Assay of PI hydrolysis.

Phosphoinositide (PI) hydrolysis was measured by anion exchange chromatography and expressed as total inositol phosphate formation as described previously (34). Freshly dispersed muscle cells (106 cells/ml) were labeled with myo-[3H]inositol (0.5 μCi/ml) for 3 h, then centrifuged at 350 g for 10 min and resuspended in 10 ml fresh HEPES medium. Cell aliquots (2 × 106 cells/ml) were treated with ACh for 60 s in the presence or absence of 1 μM AEA. In other studies, muscle cells were cultured in wells (2 × 106 cells/well) and labeled with myo-[3H]inositol for 24 h, and then treated with AEA and ACh as described above for dispersed muscle cells. [3H]inositol phosphate radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation.

Measurement of ERK1/2 and Rho-kinase activities.

ERK1/2 and Rho-kinase activities were determined in cell extracts by immunokinase assay as described previously (9, 30). Dispersed smooth muscle cells (106 cells/ml) or cultured muscle cells (2 × 106 cells/well) were treated with AEA for 5 min and with ACh for 10 min and then centrifuged for 5 min. Cell pellets were solubilized and equal amounts of protein extracts were incubated with ERK1/2 or Rho kinase-2 antibody plus protein A/G agarose overnight at 4°C. The immunoprecipitates were washed and incubated for 5 min on ice with 5 μg of myelin basic protein. The assay was initiated by the addition of 10 μCi of [32P]ATP (3,000 Ci/mmol) and 20 μM ATP. 32P-labeled myelin basic protein was absorbed onto phosphocellulose disks and the amount of radioactivity was measured by liquid scintillation.

Measurement of Src kinase activity.

Src kinase activity was measured by Western blot using a phospho-Src (Tyr416) antibody. Dispersed muscle cells (106 cells/ml) or cultured muscle cells (2 × 106 cells/well) were treated with AEA for 5 min in the presence or absence of PP2 (1 μM), AM251 (1 μM), or PTx (400 ng/ml) and solubilized on ice for 2 h in 20 mM Tris·HCl medium. The proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and phosphorylation of Src kinase was analyzed by Western blot using phospho-Src (Tyr416) antibody.

Measurement of cAMP in smooth muscle cells.

Cyclic AMP production was measured by radioimmunoassay using 125I-cAMP. Cells (3×10 cells) were treated with AEA for 60 s in the presence of 100 μm isobutylmethylxanthine 1-methyl-3-isobutylxanthine or 3,7-dihydro-1-methyl-3-(2-methylpropyl)-1H-purine-2,6-dione (IBMX), and the reaction was terminated with 10% trichloroacetic acid. The samples were acetylated with triethylamine/acetic anhydride (2:1) for 30 min and cAMP was measured in duplicate by using 100-μl aliquots. The results were expressed as picomoles per milligram protein.

Measurement of [Ca2+]i in cultured smooth muscle cells.

Dispersed muscle cells were plated on coverslips for 12 h in DMEM. The cells were washed and loaded with 10 μM fura 2-AM in HEPES medium. [Ca2+]i was measured by fluorescence in single smooth muscle cells loaded with the fluorescent Ca2+ dye fura 2-AM as previously described (11). The cells were alternately excited at 380 and 340 nm and imaged at 15-s intervals. The emitted light was imaged at 510 nm. Background and autofluorescence were corrected from images of unloaded control cells.

Measurement of contraction in dispersed smooth muscle cells.

Muscle cell contraction was measured in freshly dispersed muscle cells by scanning microscopy as described previously (11, 34). Cell aliquots containing ∼104 muscle cells/ml were treated with 1 μM AEA and 0.1 μM ACh for different time periods (30 s to 10 min), and the reaction was terminated with 1% acrolein. The lengths of treated muscle cells were compared with the lengths of untreated cells, and contraction was expressed as the percent decrease in cell length from control.

Statistical analysis.

The results were expressed as means ± SE of n experiments and analyzed for statistical significance by Student's t-test for paired and unpaired values. Differences among groups were tested by ANOVA and checked for significance via Fisher's protected least significant difference test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Selective expression of CB1 receptors in smooth muscle cells.

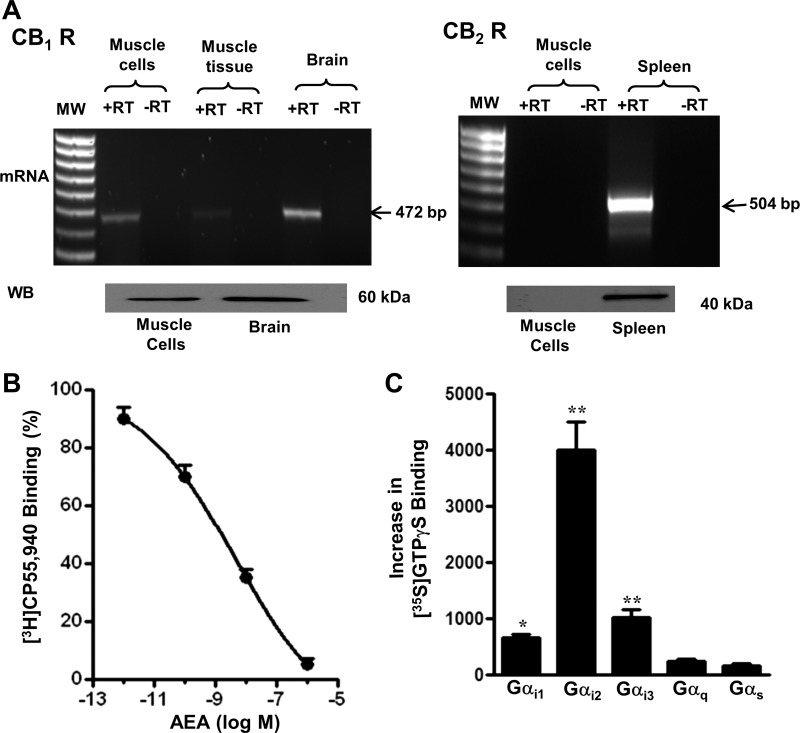

CB1 receptors were detected by RT-PCR and Western blot in cultured rabbit gastric smooth muscle cells and in brain homogenates, whereas CB2 receptors were detected in spleen homogenates but not in cultured smooth muscle cells (Fig. 1A). The partial amino acid sequence of rabbit CB1 receptors was closely similar to the corresponding amino acid sequences of human (96%), rat (96%), and mouse (97%). Binding of [3H]CP55,940 to dispersed smooth muscle cells was inhibited by AEA in a concentration-dependent fashion (IC50 5 nM), consistent with expression of CB1 receptors in these cells (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

A: selective expression of cannabinoid CB1 receptor (CB1 R) in smooth muscle cells. Total RNA isolated from cultured gastric smooth muscle cells in first passage and from brain homogenates was reverse transcribed. PCR product of the expected size (472 bp) was obtained for CB1 receptor, but not for CB2 receptor (CB2 R). CB2 receptor was detected in spleen homogenates. Western blot analysis confirmed expression of the corresponding receptor protein. B: inhibition of binding of CB1 receptor agonist [3H]CP55,940 to smooth muscle cells by anandamide (AEA). Results are expressed as percent of control specific binding (IC50 5 nM). Measurements were done in triplicate and the values are means ± SE of 5 experiments. C: preferential activation of Gαi2 by AEA in smooth muscle. AEA increased the binding of [35S]GTPγS to Gαi1, Gαi2, and Gαi3, but not to Gαq or Gαs. Values are means ± SE of 4 experiments; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. MW, molecular weight; RT, reverse transcriptase.

Preferential activation of Gαi2 by CB1 receptors.

Anandamide (AEA) increased [35S]GTPγS binding to Gαi1, Gαi2, and Gαi3 by 66 ± 13, 182 ± 20, and 54 ± 11%, respectively, but had no effect on [35S]GTPγS binding to Gαq/11 or Gαs (Fig. 1C). The results implied that CB1 receptors are preferentially coupled to Gαi2.

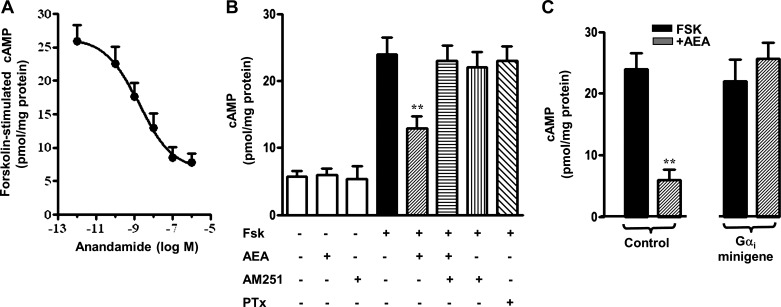

Consistent with the coupling of CB1 receptors to Gαi1–3, AEA inhibited forskolin-stimulated cAMP formation in dispersed muscle cells in a concentration-dependent fashion (IC50 13 nM) (Fig. 2A). The inhibition was blocked by the CB1 receptor antagonist AM251 and by preincubation of the muscle cells for 60 min with 400 ng/ml of PTx. By itself, AEA had no effect on basal cAMP formation, and AM251, which can act as a reverse agonist in some cells (6, 27), had no effect on basal or forskolin-stimulated cAMP formation in smooth muscle cells (Fig. 2B). AEA inhibited forskolin-stimulated cAMP formation in cultured muscle cells also; the inhibition was blocked in cells expressing Gαi minigene (Fig. 2C). Our previous studies had shown that Gαi minigenes selectively block responses mediated by Gαi (34).

Fig. 2.

Concentration-dependent inhibition of forskolin (FSK)-stimulated cAMP formation by AEA in dispersed smooth muscle cells (A), and selective blockade of inhibition by AM251 and pertussis toxin (PTx) (B). C: inhibition of forskolin-stimulated cAMP by AEA in cultured smooth muscle cells selectively blocked in cells expressing Gi minigene but not in cells expressing control, random-order Gi minigene. Results are means ± SE of 3 experiments; **P < 0.01.

Absence of Gβγ-dependent stimulation of PI hydrolysis and muscle contraction by CB1 receptor agonist.

Receptors coupled to Gi1–3 stimulate PI hydrolysis and smooth muscle contraction via Gβγ-dependent activation of PLC-β3 (17–19). Activation of CB1 receptors with AEA, however, did not stimulate PI hydrolysis or induce muscle contraction (Figs. 3, A and B). In contrast, as shown previously (18, 19) and confirmed in this study, activation of Gi3-coupled adenosine A1 receptors with CPA and Gi2-coupled δ-opioid receptors with DPDPE stimulated PI hydrolysis and induced muscle contraction (Figs. 3, A and B). The results implied that CB1 receptors did not bind or activate Gβγ.

Fig. 3.

Differential effect of Gi2-coupled CB1, Gi2-coupled opioid δ, and Gi3-coupled adenosine A1 receptor agonists on phosphoinositide (PI) hydrolysis (A) and muscle contraction (B). AEA (1 μM) had no effect on PI hydrolysis or muscle contraction, whereas [D-Pen2,D-Pen5]enkephalin (DPDPE; 1 μM) and cyclopentyl adenosine (CPA; 1 μM) stimulated PI hydrolysis and muscle contraction. Muscle contraction was expressed as percent decrease in cell length from control. PI hydrolysis was expressed as cpm/mg protein. Results are means ± SE of 3 experiments.

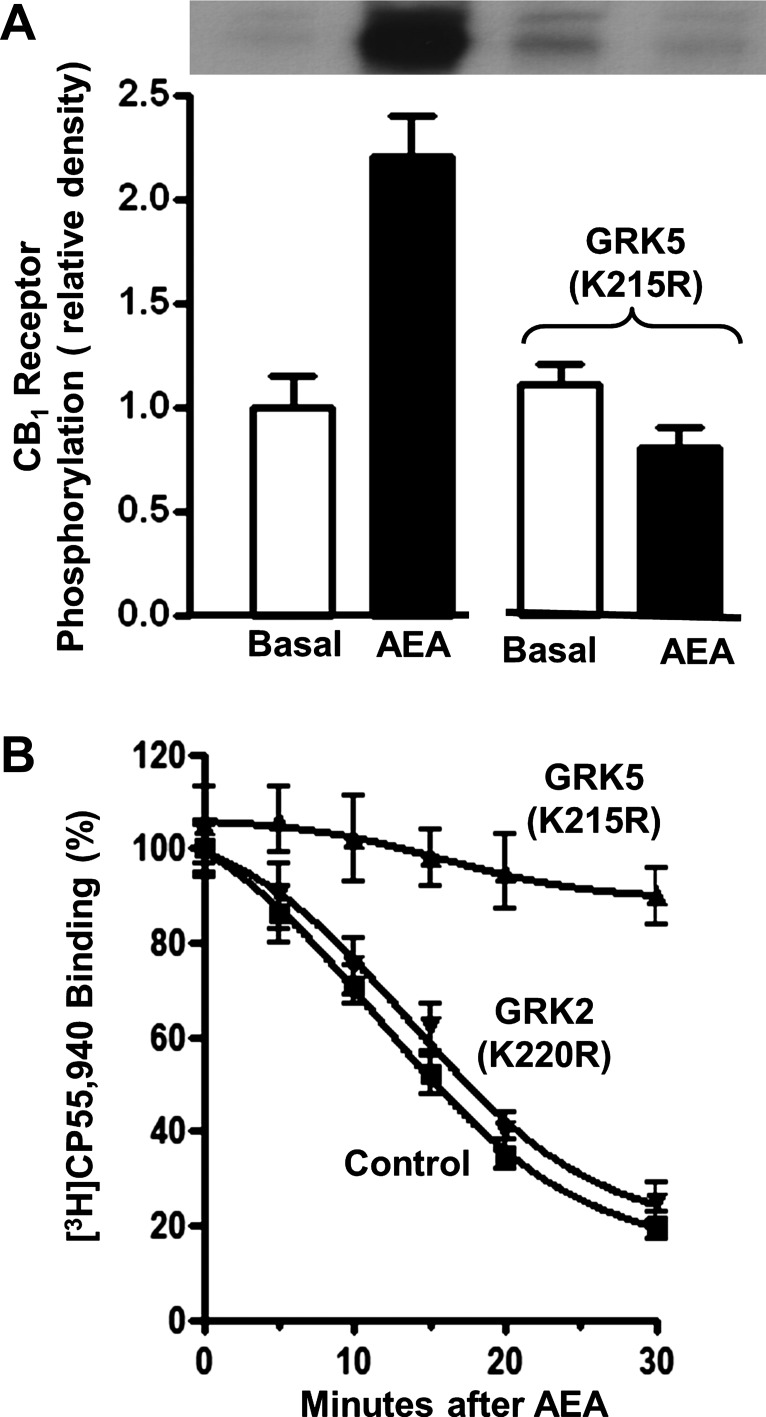

CB1 receptor phosphorylation by GRK5 mediates receptor internalization.

Treatment of cultured smooth muscle cells with 1 μM AEA for 15 min induced CB1 receptor phosphorylation; receptor phosphorylation was abolished in cells transfected with kinase-deficient GRK5 [GRK5(K215R)] (Fig. 4A). CB1 receptor internalization, determined from the decrease in binding of [3H]CP55,940 to cultured smooth muscle cells after treatment with 1 μM AEA, was ∼10% within 5 min, 50% within 15 min, and 80% within 30 min (Fig. 4B). Expression of kinase-deficient GRK5(K215R) blocked CB1 receptor internalization whereas expression of kinase-deficient GRK2(K220R) had no effect, suggesting that CB1 receptor internalization was dependent on receptor phosphorylation by GRK5 and not by GRK2/3 (9, 11) (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

GRK5-mediated phosphorylation and internalization of CB1 receptors. A: cultured smooth muscle cells transfected with control vector or vector expressing kinase-deficient GRK5 [GRK5(K215R)] were treated for 15 min with 1 μM AEA. B: time course of decrease in [3H]CP55,940 binding to cultured smooth muscle cells after treatment with 1 μM AEA in cells transfected with control vector, vector expressing kinase-deficient GRK5 [GRK5(K215R)], or vector expressing kinase-deficient GRK2 [GRK2(K220R)]. Receptor phosphorylation and internalization were blocked in cells expressing kinase-deficient GRK5. Results are means ± SE of 4 experiments.

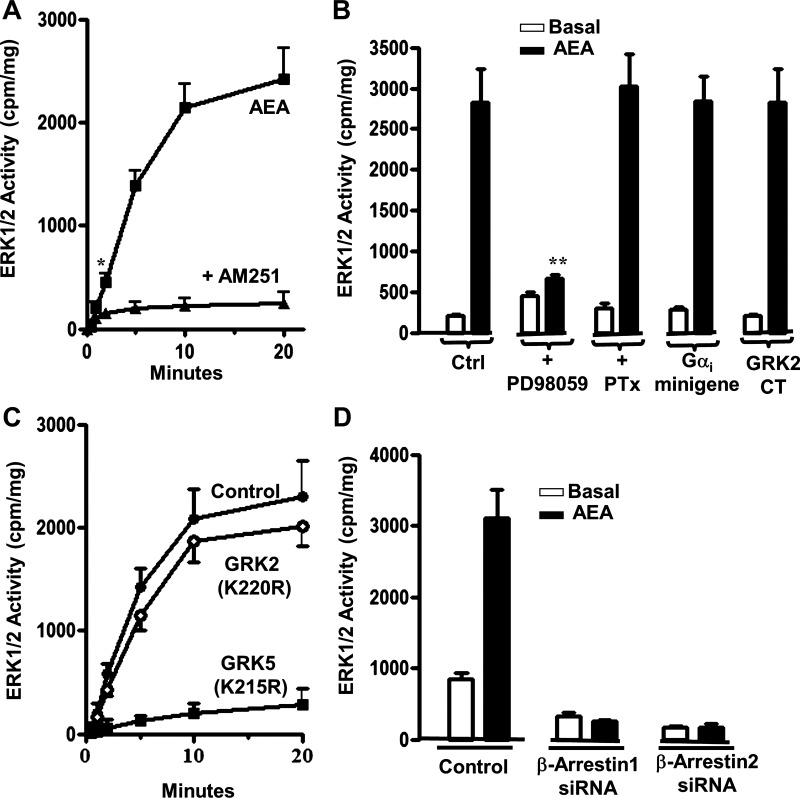

ERK1/2 and Src kinase activation by CB1 receptors depends on receptor phosphorylation and activation of β-arrestin1/2.

Treatment of cultured smooth muscle cells with AEA stimulated ERK1/2 activity in a time-dependent fashion; ERK1/2 activity was blocked by AM251 (Fig. 5A). The increase in ERK1/2 activity was significant within 1 min and attained a sustained maximum within 10 min (Fig. 5A). ERK1/2 activity was abolished by the ERK1/2 inhibitor PD98059 but was not affected by the PKC inhibitor bisindolylmaleimide or PTx or in cells expressing a Gi minigene, implying that it was not dependent on activation of Gαi (Fig. 5B). ERK1/2 activity was not affected also in cells expressing the COOH-terminal sequence of GRK2 [GRK2CT(495–689)], which competes with cytosolic GRK2 for binding to Gβγ (Fig. 5B), or in cells expressing kinase-deficient GRK2(K220R) (Fig. 5C), implying that ERK1/2 activity was not dependent on recruitment of GRK2 to the receptor by Gβγ or receptor phosphorylation by GRK2. ERK1/2 activity was blocked, however, in cells expressing kinase-deficient GRK5(K215R) (Fig. 5C) and in cells expressing siRNA for β-arrestin1 and 2 (Fig. 5D), implying that ERK1/2 activation resulted from AEA-induced phosphorylation of CB1 receptors by GRK5 and binding of β-arrestin1/2 to phosphorylated CB1 receptors.

Fig. 5.

Activation of ERK1/2 by CB1 receptors is dependent on receptor phosphorylation by GRK5 and recruitment of β-arrestin1/2. A: time course of ERK1/2 activation by AEA (1 μM) in cultured smooth muscle cells in the presence or absence of the CB1 receptor antagonist AM251 (1 μM). ERK1/2 activity was determined by immunokinase assay and expressed as cpm/mg protein. The increase in ERK1/2 activity was significant within 1 min (P < 0.05) and near maximal within 10 min. Values are means ± SE of 4 experiments. B: G protein-independent activation of ERK1/2. Treatment of cultured smooth muscle cells with PD98059 abolished AEA-stimulated ERK1/2 activity, whereas treatment with PTx (400 ng/ml for 1 h) and expression of Gαi minigene or GRK2CT(495–689), a Gβγ-scavenging peptide, or PKC inhibitor (bisindolylmaleimide, 1 μM for 10 min) had no effect. ERK1/2 activity was not affected by PKC or p38 MAP kinase inhibitors (data not shown). Values are means ± SE of 4 experiments. C: selective inhibition of AEA-stimulated ERK1/2 activity in smooth muscle cells expressing kinase-deficient GRK5(K215R). Cultured smooth muscle cells expressing vector alone (control), kinase-deficient GRK2 [GRK2(K220R)], or kinase-deficient GRK5 [GRK5(K215R)] were treated with 1 μM AEA for various times up to 20 min. Values are means ± SE of 4 experiments. D: inhibition of AEA-stimulated ERK1/2 activity in cells expressing siRNA for β-arrestin1 and -2. Values are means ± SE of 3 experiments; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

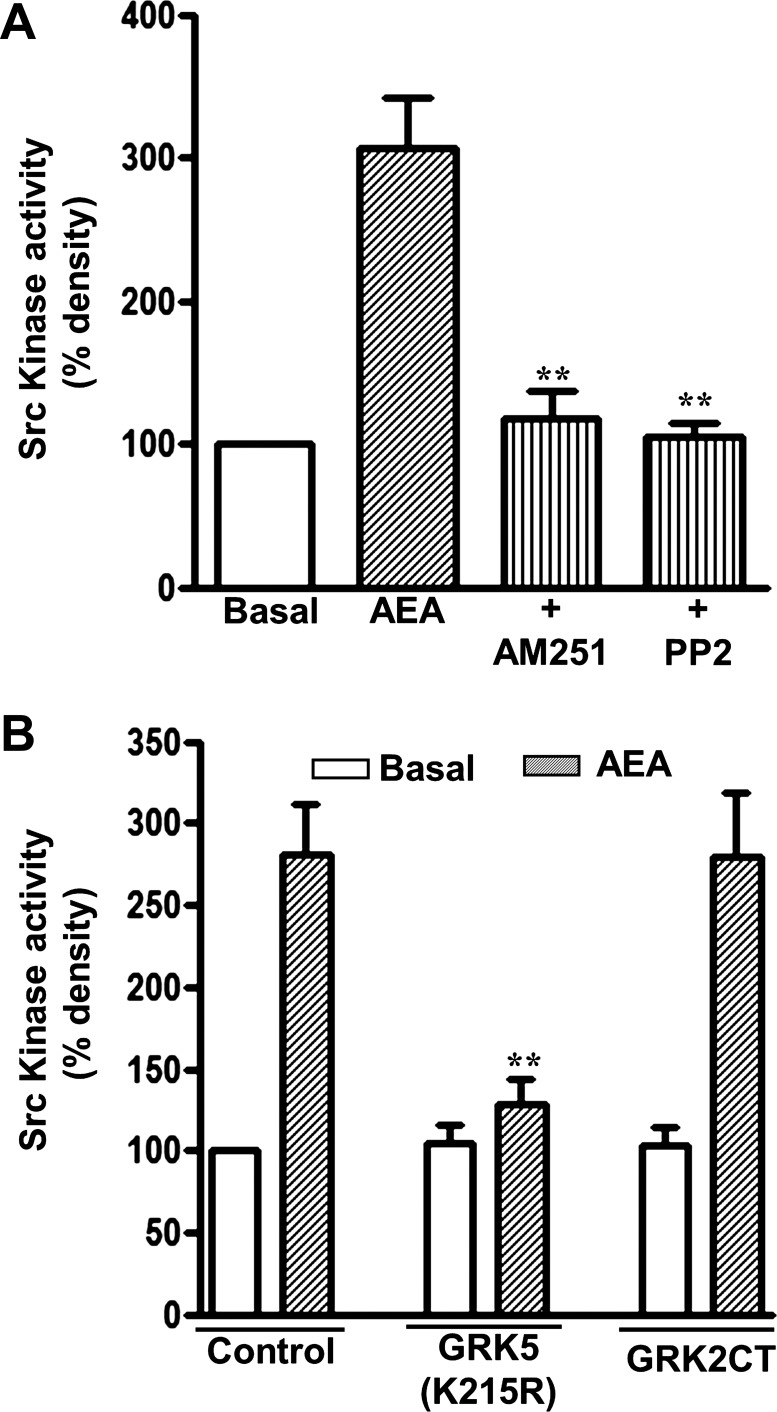

In similar fashion, treatment of cultured muscle cells with AEA for 5 min stimulated Src kinase activity. Activation of Src kinase was blocked by PP2 and AM251 (Fig. 6A), and in cells expressing GRK5(K215R) (Fig. 6B), but not in cells expressing GRK2CT(495–689). Thus Src kinase activation also resulted from AEA-induced phosphorylation of CB1 receptors via Gβγ-independent GRK5 and the binding of β-arrestin to phosphorylated CB1 receptors.

Fig. 6.

Activation of Src kinase by CB1 receptors is dependent on receptor phosphorylation by GRK5 and independent of Gβγ. A: cultured smooth muscle cells were treated for 5 min with AEA in the presence and absence of 1 μM AM251 or 1 μM PP2 (Src kinase inhibitor). Src kinase activity was determined using phospho-specific Src(Tyr416) antibody. Values are means ± SE of 4 experiments. B: selective inhibition of AEA-stimulated Src kinase activity in cultured muscle cells expressing kinase-deficient GRK5(K215R). Cultured smooth muscle cells expressing vector (control), kinase-deficient GRK5 [GRK5(K215R)], and GRK2CT(495–689), a Gβγ scavenging peptide, were treated for 5 min with AEA. Values are means ± SE of 4 experiments; **P < 0.01.

Activation of ERK1/2 and Src kinase modulates ACh-stimulated contraction via phosphorylation of RGS4 by ERK1/2 and M-RIP and MYPT1 by Src kinase.

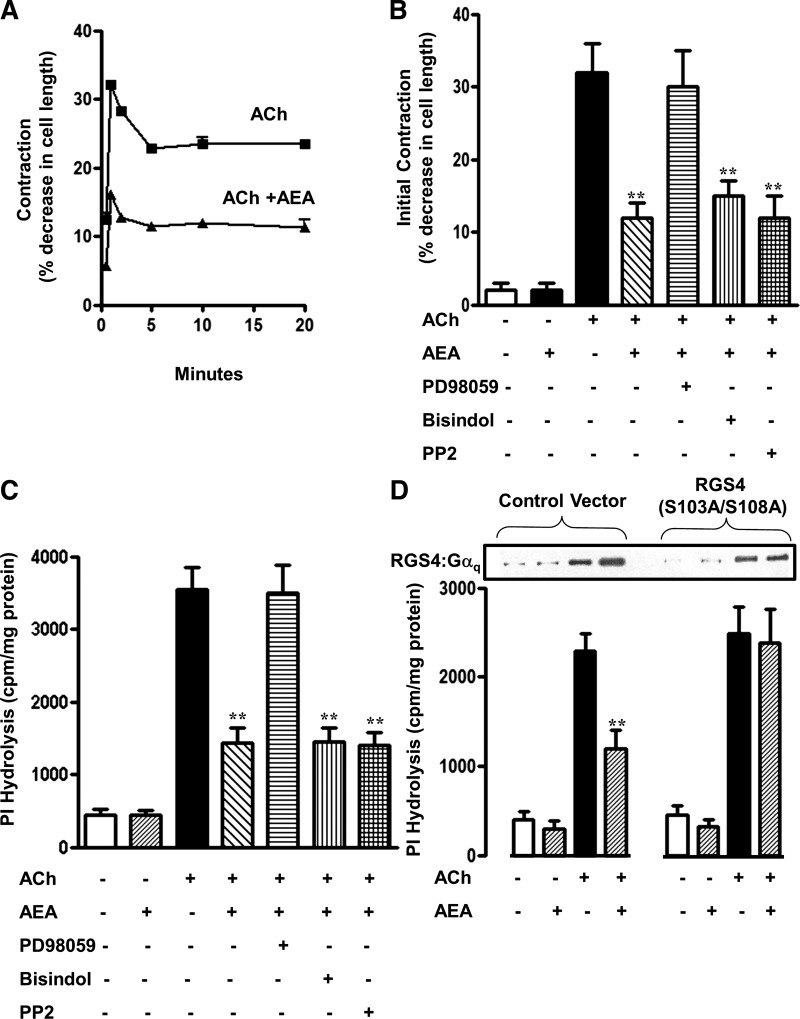

Activation of ERK1/2 and Src kinase raised the possibility that one or both kinases could modulate concurrent smooth muscle contraction. As shown previously (20) and confirmed in the present study, ACh acting via m3 receptors (i.e., ACh in the presence of the m2 receptor antagonist methoctramine) stimulates PI hydrolysis and induces a biphasic contraction consisting of an initial 30 s peak followed by a sustained contraction. AEA inhibited both initial and sustained ACh-stimulated contraction (Fig. 7A). AEA inhibited ACh-stimulated PI hydrolysis, [Ca2+]i, and initial contraction in dispersed smooth muscle cells by 65 ± 6% (P < 0.01), 66 ± 13% (P < 0.01), and 54 ± 2% (P < 0.001), respectively: the inhibition of PI hydrolysis and initial contraction was selectively blocked by PD98059, but not by bisindolylmaleimide or PP2 (Figs. 7, B and C), implying that it was mediated by ERK1/2.

Fig. 7.

Inhibition of ACh-stimulated initial contraction by AEA is mediated by ERK1/2. A: time course of inhibition of ACh-stimulated initial and sustained muscle contraction by AEA. Dispersed smooth muscle cells were treated with 0.1 μM ACh in the presence of 0.1 μM methoctramine (m2 receptor antagonist) with or without 1 μM AEA for various time periods. Cell contraction was measured by scanning micrometry and expressed as percent decrease in cell length from control (109 ± 4 μm). Values are means ± SE of 4 experiments. B: dispersed smooth muscle cells were treated with 1 μM AEA for 10 min followed by 0.1 μM ACh and 0.1 μM methoctramine for 30 s. The experiments were repeated in the presence of 10 μM PD98059, 1 μM PP2, or 1 μM bisindolylmaleimide. PD98059 reversed AEA-induced inhibition of peak 30-s muscle contraction. Values are means ± SE of 4–5 experiments. C: dispersed smooth muscle cells were labeled with myo-[3H]inositol for 3 h and then treated with 1 μM AEA for 10 min followed by 0.1 μM ACh and 0.1 μM methoctramine for 30 s. The experiments were repeated in the presence of 10 μM PD98059, 1 μM PP2, or 1 μM bisindolylmaleimide. PD98059 reversed AEA-induced inhibition of PI hydrolysis. Values are means ± SE of 3 experiments. D: blockade of AEA-induced inhibition of PI hydrolysis in cells expressing phosphorylation-deficient RGS4 mutant. Bottom: cultured smooth muscle cells expressing wild-type RGS4 (vector alone) or phosphorylation-deficient RGS4(S103A/108A) were labeled with myo-[3H]inositol for 24 h and then treated with AEA for 10 min followed by 0.1 μM ACh and 0.1 μM methoctramine for 30 s. Values are means ± SE of 4 experiments. Top: bands show that the increase in Gαq:RGS4 association induced by ACh was augmented upon addition of AEA in control cells but not in cells expressing RGS4(S103A/108A) **P < 0.01.

We next examined the mechanism by which ERK1/2 inhibited PI hydrolysis and muscle contraction. ACh-stimulated PI hydrolysis in smooth muscle is mediated by Gαq-dependent activation of PLC-β1 and regulated by RGS4, which binds to and enhances the intrinsic GTPase activity of Gαq.GTP (12). We identified a proline-rich consensus site (102KSPSKLSP109) in RGS4 for phosphorylation by ERK1/2 and hypothesized that phosphorylation of Ser103 and/or Ser108 by ERK1/2 could further enhance the GTPase activity of Gαq.GTP leading to rapid inactivation of Gαq and inhibition of Gαq-dependent PI hydrolysis. In control cultured muscle cells, AEA inhibited ACh-stimulated PI hydrolysis and increased Gαq:RGS4 association, whereas in cultured muscle cells expressing a mutant RGS4(S103A/S108A) that lacks ERK1/2 phosphorylation sites, AEA did not inhibit PI hydrolysis or increase Gαq:RGS4 association (Fig. 7D). The results suggest that inhibition of PI hydrolysis and initial muscle contraction by AEA-stimulated ERK1/2 is mediated via stimulatory phosphorylation of RGS4, resulting in rapid inactivation of Gαq.GTP.

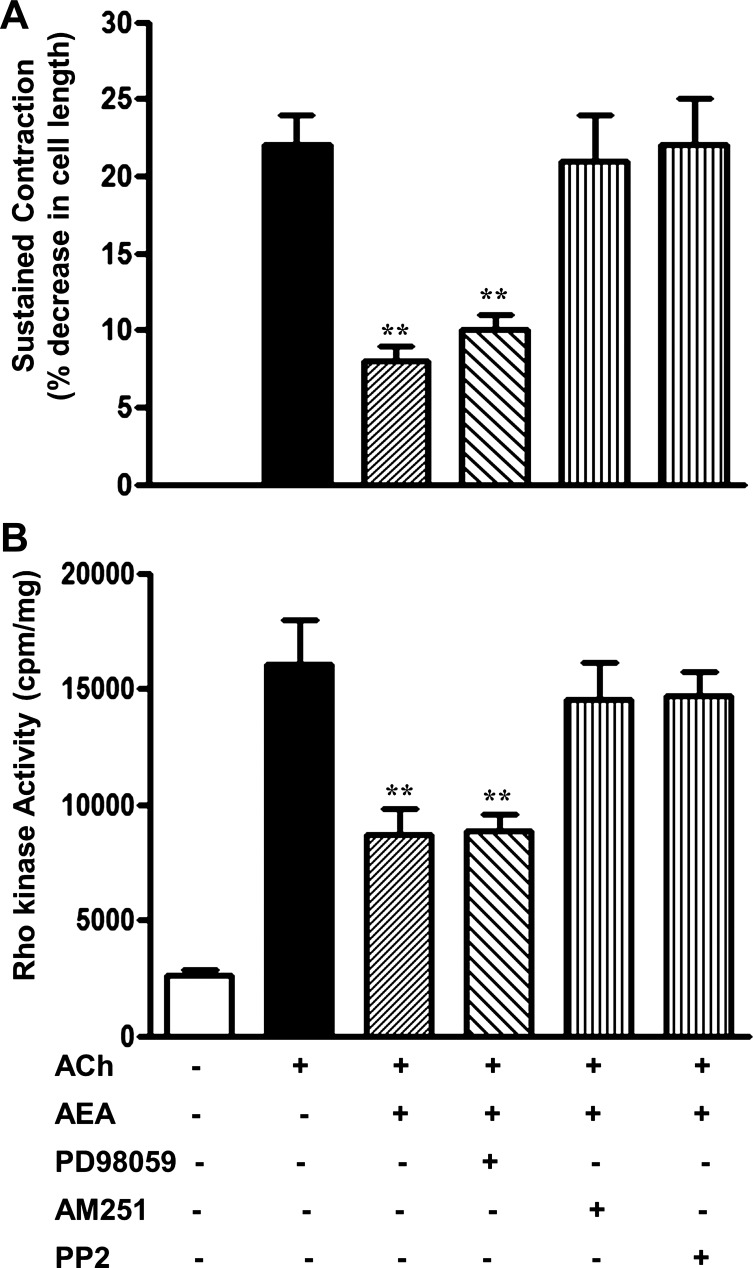

Unlike initial contraction, sustained contraction is mediated by Rho kinase-dependent phosphorylation of MYPT1 and inhibition of MLC phosphatase activity (16, 20). Measurements of sustained contraction and Rho kinase activity were, therefore, made 5 min after treatment with ACh and AEA. AEA inhibited ACh-stimulated Rho kinase activity and sustained contraction in dispersed muscle cells by 48 ± 8 and 48 ± 5%, respectively; P < 0.01 (Fig. 8, A and B). Inhibition of sustained contraction and Rho kinase activity was blocked by AM251 and PP2, but not by PD98059 (Fig. 8, A and B).

Fig. 8.

Inhibition of ACh-stimulated sustained contraction and Rho kinase activity by AEA is mediated by Src kinase. A and B: dispersed smooth muscle cells were treated with 1 μM AEA for 10 min followed by 0.1 μM ACh and 0.1 μM methoctramine for 5 min (the time point corresponds to the start of sustained contraction; see Fig. 7A). The experiments were repeated in the presence of 10 μM PD98059, 1 μM PP2, or 1 μM AM251. Smooth muscle contraction was measured by scanning micrometry and expressed as percent decrease in cell length from control (106 ± 4 μm). Values are means ± SE of 4–5 experiments. Rho kinase activity was determined by immunokinase assay and expressed as cpm/mg protein. Values are means ± SE of 3 experiments. AEA-induced inhibition of sustained muscle contraction and Rho kinase activity was reversed by the Src kinase inhibitor, PP2, and the CB1 receptor antagonist AM251. **P < 0.01.

As previously shown (16, 20, 30), the decrease in Rho kinase activity should lead to decrease in MYPT1 phosphorylation by Rho kinase and thus enhance MLC phosphatase activity.

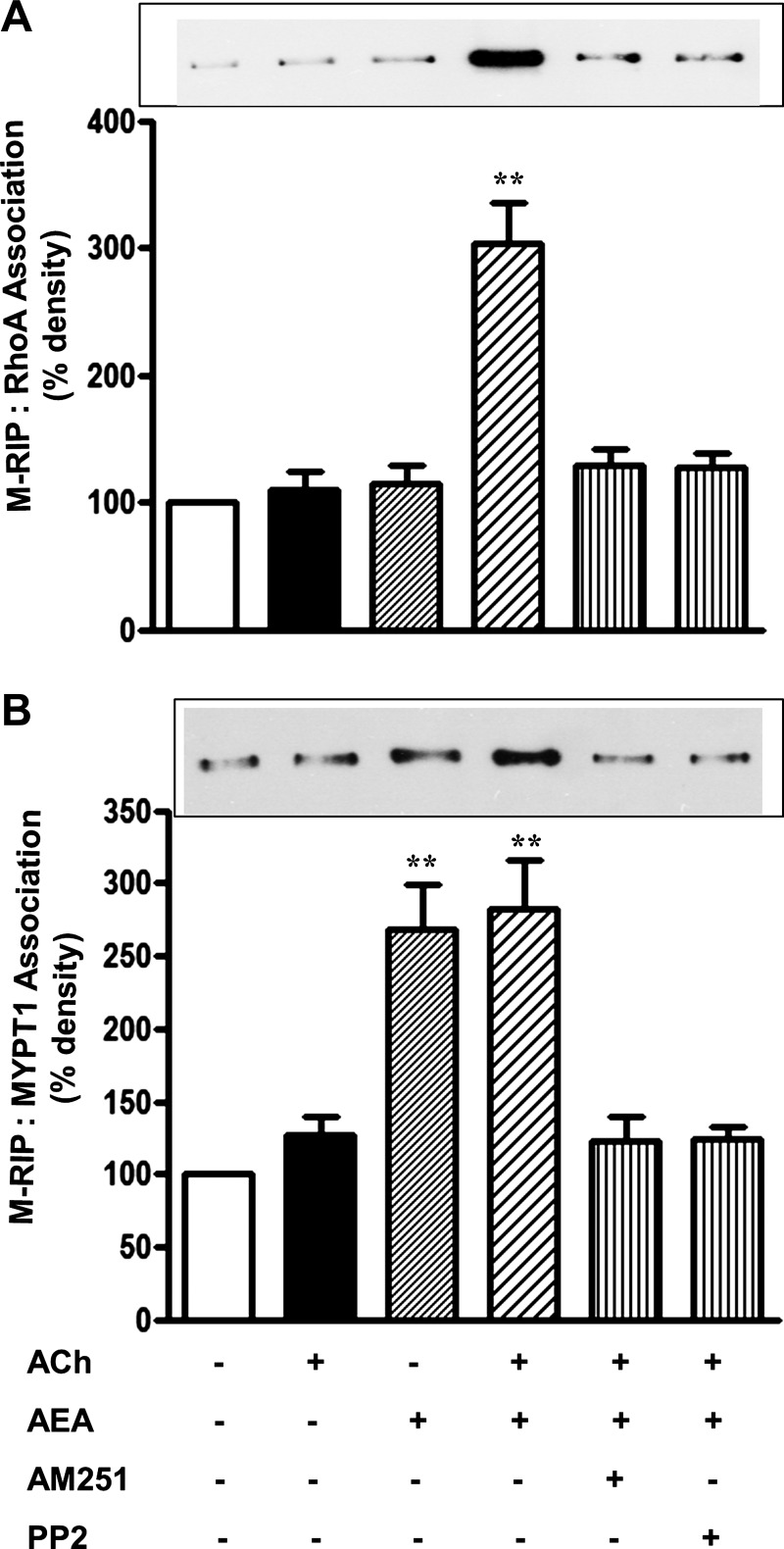

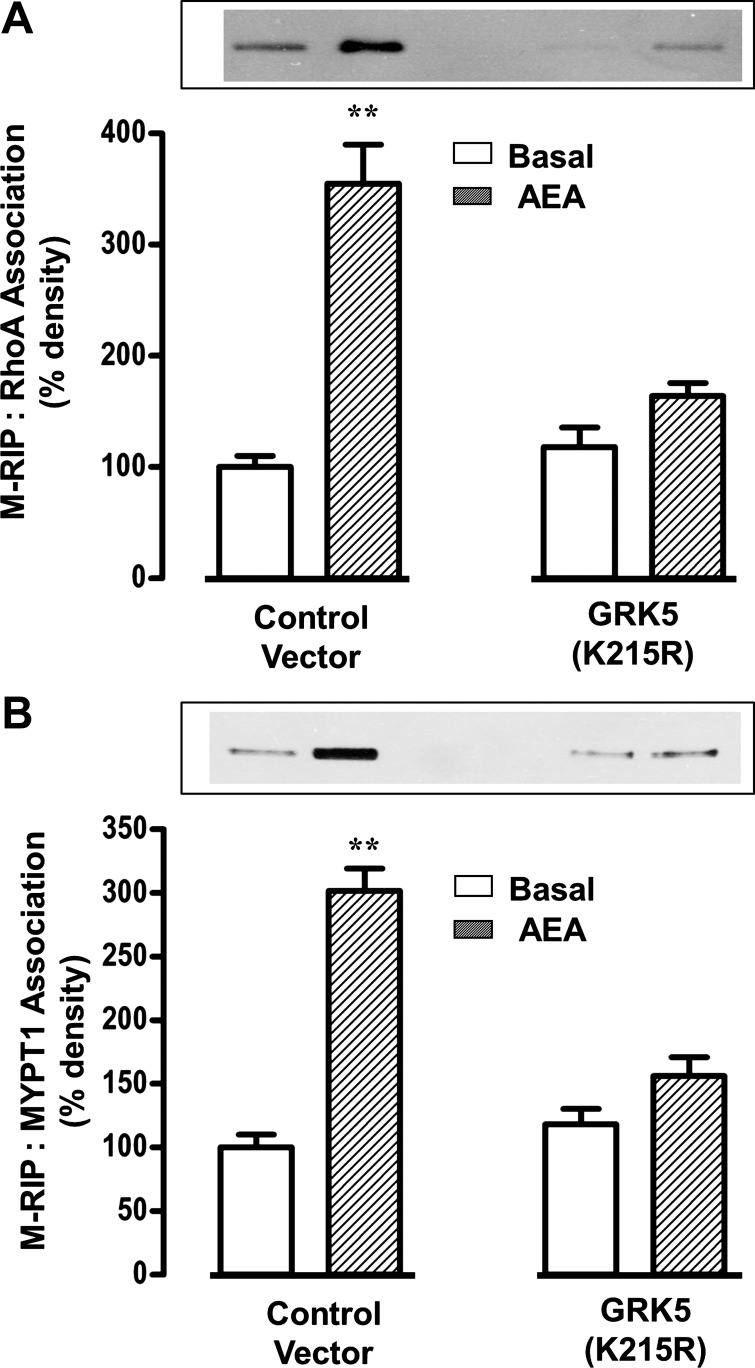

We hypothesized that Src kinase enhances the association of M-RIP (MYPT1/RhoA interacting protein) (13, 24) with both RhoA and MYPT1 leading to increase in MLC phosphatase activity (16, 20). Treatment of cultured muscle cells with AEA for 10 min enhanced association of M-RIP with RhoA (Fig. 9A) and MYPT1 (Fig. 9B). The increase in M-RIP:RhoA and M-RIP:MYPT1 association was blocked by AM251 and PP2 (Fig. 9, A and B), and in smooth muscle cells expressing kinase-deficient GRK5(K215R) (Fig. 10, A and B). Thus activation of Src kinase upon phosphorylation of CB1 receptors by GRK5 enhanced the association of M-RIP with both RhoA and MYPT1. The increase in M-RIP:RhoA association inhibited Rho kinase activity and thus should inhibit Rho kinase-dependent MYPT1 phosphorylation, leading to increase in MLC phosphatase activity. The increase in M-RIP:MYPT1 association should enhance further the activity of the MLC phosphatase holoenzyme by fostering its binding to the actomyosin complex (13). Both mechanisms result in inhibition of sustained muscle contraction.

Fig. 9.

Stimulation of myosin phosphatase RhoA-interacting protein (M-RIP):RhoA and M-RIP:MYPT1 association by AEA is mediated by Src kinase. Dispersed smooth muscle cells were treated separately with 1) 0.1 μM ACh plus 0.1 μM methoctramine, 2) 1 μM AEA, and 3) 1 μM AEPP2 or 1A plus 0.1 μM ACh plus 0.1 μM methoctramine for 5 min. The experiments were repeated in the presence of 1 μM PP2 or 1 μM AM251. Immunoprecipitates derived from 500 μg of protein by using RhoA antibody (A) or MYPT1 antibody (B) were separated on SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with M-RIP antibody. AEA alone or with ACh increased M-RIP:MYPT1 association. The increase in M-RIP:RhoA and M-RIP:MYPT1 association induced by a combination of AEA and ACh was abolished by PP2 and AM251. Values are means ± SE of 4 experiments; **P < 0.01.

Fig. 10.

Inhibition of M-RIP:RhoA and M-RIP:MYPT1 association in cells expressing kinase-deficient GRK5. Cultured smooth muscle expressing vector or GRK5(K215R) were treated with 1 μM AEA, 0.1 μM ACh, and 0.1 μM methoctramine for 5 min. Immunoprecipitates derived from 500 μg of protein by using RhoA antibody (A) or MYPT1 (B) antibody were separated on SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with M-RIP antibody. The increase in M-RIP:RhoA and M-RIP:MYPT1 association was abolished in cells expressing kinase-deficient GRK5(K215R). Values are means ± SE of 4 experiments; **P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

The present study shows that CB1 receptors are selectively expressed in smooth muscle cells and signal via Gαi2, causing inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity, but do not signal via Gβγ as do other Gi-coupled receptors in these cells (17–19). CB1 receptors signal also via β-arrestin1/2 in a G protein-independent fashion to activate ERK1/2 and Src kinase. Uncoupling of CB1 receptors from Gi by PTx or by expression of Gi minigene abolished inhibition of cAMP but had no effect on ERK1/2 activity, whereas expression of kinase-deficient GRK5(K215R) or silencing of β-arrestin1/2 with siRNA abolished ERK1/2.

AEA-induced CB1 receptor phosphorylation was blocked in smooth muscle cells expressing kinase-deficient GRK5 [GRK5(K215R)], implying that CB1 receptors were phosphorylated by GRK5. Unlike GRK2/3, which are located in the cytosol and are recruited to G protein-coupled receptors by activated Gβγ (9, 11), GRK5 and GRK6 are constitutively tethered to the plasma membrane, where they directly phosphorylate agonist-bound receptors (4). Activation of ERK1/2, which was significant within 1 min and maximal within 10 min, was not affected by expression of kinase-deficient GRK2(K220R) or a Gβγ-scavenging peptide, implying that it was not dependent on activation of Gβγ or recruitment of GRK2. ERK1/2 activity was blocked, however, by expression of kinase-deficient GRK5(K215R) or β-arrestin1/2 siRNA, implying that ERK1/2 activation resulted from agonist-induced phosphorylation of CB1 receptors by GRK5 and binding of β-arrestin1/2 to phosphorylated CB1 receptors.

GRK5-dependent activation of ERK1/2 and Src kinase endowed CB1 receptors with the ability to inhibit concurrent contractile activity. We had previously shown that the initial transient contraction induced by ACh is mediated by Gαq-dependent activation of PLC-β1 and terminated by RGS4 (9, 11). In this study, we identified a consensus sequence (102KSPSKLSP109) for phosphorylation of RGS4 by ERK1/2 and showed that expression of a phosphorylation-deficient RGS4 mutant lacking Ser103 and Ser108 blocked the ability of AEA to inhibit of ACh-stimulated PI hydrolysis or enhance Gαq:RGS4 association. Huang et al. (12) had previously reported a similar mechanism involving phosphorylation of RGS4 at Ser52 by cyclic AMP- and cGMP-dependent protein kinases that resulted in inhibition of ACh-stimulated initial contraction and PI hydrolysis (12).

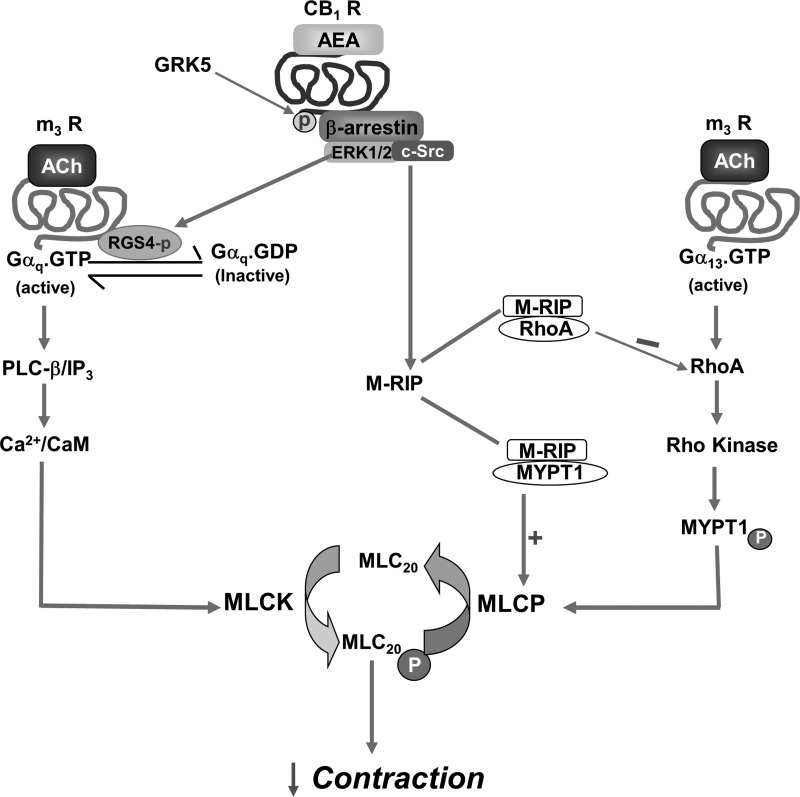

Unlike the initial transient contraction, sustained contraction is mediated in part by Rho kinase-dependent phosphorylation of the myosin phosphatase-targeting subunit, MYPT1 (16, 29, 31). Phosphorylation of MYPT1 at Thr696 by Rho kinase inhibits the activity of the catalytic subunit of MLC phosphatase and fosters sustained MLC20 phosphorylation and contraction. Stimulation of Src kinase activity by AEA enhanced both M-RIP:RhoA and M-RIP:MYPT1 association. The increase in M-RIP:RhoA association inhibited Rho kinase activity and, therefore, should attenuate MYPT1 phosphorylation by Rho kinase, leading to increase in MLC phosphatase activity, whereas the increase in M-RIP:MYPT1 association should enhance further the ability of MYPT1 to activate MLC phosphatase holoenzyme by fostering its binding to the actomyosin complex. The dual mechanism initiated by Src kinase upon phosphorylation of CB1 receptors increased MLC phosphatase activity and inhibited sustained contraction (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11.

Scheme depicting the inhibition of smooth muscle contraction via CB1 receptors. CB1 receptor phosphorylation by GRK5 leads to recruitment of β-arrestin1/2 and activation of ERK1/2 and Src kinase. ERK1/2 phosphorylates RGS4 at Ser103/108 and increases its association with and activation of Gαq-GTPase, resulting in inhibition of the Gαq/PLC-β/IP3/Ca2+/MLCK pathway that mediates initial contraction. Activation of Src kinase stimulates 1) M-RIP:MYPT1 association enhancing the ability of MYPT1 to activate MLC phosphatase, and 2) M-RIP:RhoA association, causing inhibition of Rho kinase and decreasing its ability to phosphorylate and inhibit MYPT1. Thus Src kinase acting via M-RIP enhanced MLCP activity, leading to inhibition of the Gα13/RhoA/Rho kinase/MYPT1/MLCP pathway that mediates sustained contraction.

The results of this study may be usefully compared with those of Shenoy et al. (25) obtained in cell lines expressing a β2 adrenergic receptor mutant (β2ARTYY) incapable of G protein activation. Overexpression of GRK5 or -6 in these cells enhanced recruitment of β-arrestin to the receptor and its ability to induce prompt, sustained activation of ERK1/2. GRK2 expression was effective only when targeted to the membrane by coexpression of a prenylation signal (CAAX). In our study, CB1 receptors constitutively expressed in a native smooth muscle cell, signaled concurrently via Gαi and β-arrestin, the latter upon receptor phosphorylation by GRK5. Uncoupling CB1 receptors from G proteins by PTx or expression of Gi minigene had no effect on β-arrestin-dependent activation of ERK1/2 and Src kinase. Unlike other Gi-coupled receptors in smooth muscle, CB1 receptors did not engage Gβγ to initiate signaling that would have resulted in activation of dual pathways involving PLC-β3 and PI 3-kinase/integrin linked kinase (17–19).

The present study does not resolve the fate or role of Gβγ in CB1 receptor signaling. It is possible that interaction of Gβγ with both CB1 receptor and Gαi allows for productive guanine nucleotide exchange on Gαi without sustaining downstream signaling via Gβγ. Alternatively, the Gβγ dimer could be atypical, consisting, for example, of Gβ5 bound to the Gγ-like domain of R7 subfamily of RGS proteins (e.g., RGS6, -7, -9, -11) (1, 28). This subfamily is defined by the presence of three domains: an NH2-terminal DEP (Dishevelled, Egl, Pleckstrin) domain, linked via a DEP helical extension to a central Gγ-like domain tightly bound to a COOH-terminal catalytic domain with selectivity for Gαi. Although these atypical G protein dimers are preferentially expressed in neural tissues (28), a member of this subfamily, Gβ5-RGS6, has also been found in smooth muscle (14). A Gβ5-RGS6 heterodimer could bind to Gαi and permit CB1 receptor-mediated nucleotide exchange without being able to substitute for, or signal in place of, a canonical Gβγ. This intriguing notion, however, remains speculative.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants to K. S. Murthy (DK28300 and DK15564).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.M. and K.S.M. conception and design of research; S.M., W.S., and J.H. performed experiments; S.M., W.S., J.H., and K.S.M. analyzed data; S.M. prepared figures; S.M. and K.S.M. drafted manuscript; S.M., J.R.G., and K.S.M. edited and revised manuscript; J.H., J.R.G., and K.S.M. interpreted results of experiments; J.R.G. and K.S.M. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson GR, Posokhova E, Martemyanov KA. The R7 RGS protein family: multi-subunit regulators of neuronal G protein signaling. Cell Biochem Biophys 54: 33–46, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brighton PJ, Marczylo TH, Rana S, Konje JC, Willets JM. Characterization of the endocannabinoid system, CB1 receptor signalling and desensitization in human myometrium. Br J Pharmacol 164: 1479–1494, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown AJ. Novel cannabinoid receptors. Br J Pharmacol 152: 567–575, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferguson SS. Evolving concepts in G protein-coupled receptor endocytosis: the role in receptor desensitization and signaling. Pharmacol Rev 53: 1–24, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Filipeanu CM, de Zeeuw D, Nelemans SA. Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol activates [Ca2+]i increases partly sensitive to capacitative store refilling. Eur J Pharmacol 336: R1–R3, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fiori JL, Sanghvi M, O'Connell MP, Krzysik-Walker SM, Moaddel R, Bernier M. The cannabinoid receptor inverse agonist AM251 regulates the expression of the EGF receptor and its ligands via destabilization of oestrogen-related receptor a protein. Br J Pharmacol 164: 1026–1040, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gebremedhin D, Lange AR, Campbell WB, Hillard CJ, Harder DR. Cannabinoid CB1 receptor of cat cerebral arterial muscle functions to inhibit L-type Ca2+ channel current. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 276: H2085–H2093, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howlett AC, Barth F, Bonner TI, Cabral G, Casellas P, Devane WA, Felder CC, Herkenham M, Mackie K, Martin BR, Mechoulam R, Pertwee RG. International Union of Pharmacology. XXVII. Classification of cannabinoid receptors. Pharmacol Rev 54: 161–202, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang J, Mahavadi S, Sriwai W, Grider JR, Murthy KS. Cross-regulation of VPAC2 receptor desensitization by M3 receptors via PKC-mediated phosphorylation of RKIP and inhibition of GRK2. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 292: G867–G874, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang J, Mahavadi S, Sriwai W, Hu W, Murthy KS. Gi-coupled receptors mediate phosphorylation of CPI-17 and MLC20 via preferential activation of the PI3K/ILK pathway. Biochem J 396: 193–200, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang J, Zhou H, Mahavadi S, Sriwai W, Lyall V, Murthy KS. Signaling pathways mediating gastrointestinal smooth muscle contraction and MLC20 phosphorylation by motilin receptors. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 288: G23–G31, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang J, Zhou H, Mahavadi S, Sriwai W, Murthy KS. Inhibition of Gαq-dependent PLC-β1 activity by PKG and PKA is mediated by phosphorylation of RGS4 and GRK2. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292: C200–C208, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koga Y, Ikebe M. p116Rip decreases myosin II phosphorylation by activating myosin light chain phosphatase and by inactivating RhoA. J Biol Chem 280: 4983–4991, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahavadi S, Zhou H, Murthy KS. Distinctive signaling by cannabinoid CB1 receptors in smooth muscle cells: absence of Gβγ-dependent activation of PLC-β (Abstract). Gastroenterology 126: A-275, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murthy KS. Modulation of soluble guanylate cyclase activity by phosphorylation. Neurochem Int 45: 845–851, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murthy KS. Signaling for contraction and relaxation in smooth muscle of the gut. Annu Rev Physiol 68: 345–374, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murthy KS, Coy DH, Makhlouf GM. Somatostatin receptor-mediated signaling in smooth muscle. Activation of phospholipase C-β3 by Gβγ and inhibition of adenylyl cyclase by Gαi1 and Gαo. J Biol Chem 271: 23458–23463, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murthy KS, Makhlouf GM. Adenosine A1 receptor-mediated activation of phospholipase C-β3 in intestinal muscle: dual requirement for α and βγ subunits of Gi3. Mol Pharmacol 47: 1172–1179, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murthy KS, Makhlouf GM. Opioid μ, δ, and κ receptor-induced activation of phospholipase C-β3 and inhibition of adenylyl cyclase is mediated by Gi2 and Go in smooth muscle. Mol Pharmacol 50: 870–877, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murthy KS, Zhou H, Grider JR, Brautigan DL, Eto M, Makhlouf GM. Differential signalling by muscarinic receptors in smooth muscle: m2-mediated inactivation of myosin light chain kinase via Gi3, Cdc42/Rac1 and p21-activated kinase 1 pathway, and m3-mediated MLC20 (20 kDa regulatory light chain of myosin II) phosphorylation via Rho-associated kinase/myosin phosphatase targeting subunit 1 and protein kinase C/CPI-17 pathway. Biochem J 374: 145–155, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okamoto T, Ikezu T, Murayama Y, Ogata E, Nishimoto I. Measurement of GTP γ S binding to specific G proteins in membranes using G-protein antibodies. FEBS Lett 305: 125–128, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pertwee RG, Howlett AC, Abood ME, Alexander SP, Di Marzo V, Elphick MR, Greasley PJ, Hansen HS, Kunos G, Mackie K, Mechoulam R, Ross RA. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXIX. Cannabinoid receptors and their ligands: beyond CB1 and CB2. Pharmacol Rev 62: 588–631, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rajagopal S, Kumar DP, Mahavadi S, Bhattacharya S, Zhou R, Corvera CU, Bunnett NW, Grider JR, Murthy KS. Activation of G protein-coupled bile acid receptor, TGR5, induces smooth muscle relaxation via both Epac-and PKA-mediated inhibition of RhoA/Rho kinase pathway. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 304: G527–G535, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riddick N, Ohtani K, Surks HK. Targeting by myosin phosphatase-RhoA interacting protein mediates RhoA/ROCK regulation of myosin phosphatase. J Cell Biochem 103: 1158–1170, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shenoy SK, Drake MT, Nelson CD, Houtz DA, Xiao K, Madabushi S, Reiter E, Premont RT, Lichtarge O, Lefkowitz RJ. β-arrestin-dependent, G protein-independent ERK1/2 activation by the β2 adrenergic receptor. J Biol Chem 281: 1261–1273, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shukla AK, Xiao K, Lefkowitz RJ. Emerging paradigms of β-arrestin-dependent seven transmembrane receptor signaling. Trends Biochem Sci 36: 457–469, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sink KS, Segovia KN, Collins LE, Markus EJ, Vemuri VK, Makriyannis A, Salamone JD. The CB1 inverse agonist AM251, but not the CB1 antagonist AM4113, enhances retention of contextual fear conditioning in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 95: 479–484, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slepak VZ. Structure, function, and localization of Gβ5-RGS complexes. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 86: 157–203, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Somlyo AP, Somlyo AV. Ca2+ sensitivity of smooth muscle and nonmuscle myosin II: modulated by G proteins, kinases, and myosin phosphatase. Physiol Rev 83: 1325–1358, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sriwai W, Zhou H, Murthy KS. Gq-dependent signalling by the lysophosphatidic acid receptor LPA3 in gastric smooth muscle: reciprocal regulation of MYPT1 phosphorylation by Rho kinase and cAMP-independent PKA. Biochem J 411: 543–551, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sward K, Mita M, Wilson DP, Deng JT, Susnjar M, Walsh MP. The role of RhoA and Rho-associated kinase in vascular smooth muscle contraction. Curr Hypertens Rep 5: 66–72, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turu G, Hunyady L. Signal transduction of the CB1 cannabinoid receptor. J Mol Endocrinol 44: 75–85, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Witherow DS, Wang Q, Levay K, Cabrera JL, Chen J, Willars GB, Slepak VZ. Complexes of the G protein subunit Gβ5 with the regulators of G protein signaling RGS7 and RGS9. Characterization in native tissues and in transfected cells. J Biol Chem 275: 24872–24880, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou H, Murthy KS. Distinctive G protein-dependent signaling in smooth muscle by sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors S1P1 and S1P2. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 286: C1130–C1138, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]