Abstract

Resveratrol is suggested to have beneficial cardiovascular and renoprotective effects. Resveratrol increases endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) expression and nitric oxide (NO) synthesis. We hypothesized resveratrol acts as an acute renal vasodilator, mediated through increased NO production and scavenging of reactive oxygen species (ROS). In anesthetized rats, we found 5.0 mg/kg body weight (bw) of resveratrol increased renal blood flow (RBF) by 8% [from 6.98 ± 0.42 to 7.54 ± 0.17 ml·min−1·gram of kidney weight−1 (gkw); n = 8; P < 0.002] and decreased renal vascular resistance (RVR) by 18% from 15.00 ± 1.65 to 12.32 ± 1.20 arbitrary resistance units (ARU; P < 0.002). To test the participation of NO, we administered 5.0 mg/kg bw resveratrol before and after 10 mg/kg bw of the NOS inhibitor N-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME). l-NAME reduced the increase in RBF to resveratrol by 54% (from 0.59 ± 0.05 to 0.27 ± 0.06 ml·min−1·gkw−1; n = 10; P < 0.001). To test the participation of ROS, we gave 5.0 mg/kg bw resveratrol before and after 1 mg/kg bw tempol, a superoxide dismutase mimetic. Resveratrol increased RBF 7.6% (from 5.91 ± 0.32 to 6.36 ± 0.12 ml·min−1·gkw−1; n = 7; P < 0.001) and decreased RVR 19% (from 18.83 ± 1.37 to 15.27 ± 1.37 ARU). Tempol blocked resveratrol-induced increase in RBF (from 0.45 ± 0.12 to 0.10 ± 0.05 ml·min−1·gkw−1; n = 7; P < 0.03) and the decrease in RVR posttempol was 44% of the control response (3.56 ± 0.34 vs. 1.57 ± 0.21 ARU; n = 7; P < 0.006). We also tested the role of endothelium-derived prostanoids. Two days of 10 mg/kg bw indomethacin pretreatment did not alter basal blood pressure or RBF. Resveratrol-induced vasodilation remained unaffected. We conclude intravenous resveratrol acts as an acute renal vasodilator, partially mediated by increased NO production/NO bioavailability and superoxide scavenging but not by inducing vasodilatory cyclooxygenase products.

Keywords: resveratrol, nitric oxide, renal hemodynamics, prostaglandins, reactive oxygen species, tempol

in addition to maintaining water balance and electrolyte levels, the kidney must regulate renal vascular resistance (RVR) to maintain renal blood flow (RBF) and glomerular filtration rate. RBF is maintained by vessels constantly adjusting diameter and tone in response a variety of mechanisms including local shear stress, sympathetic, endocrine, and paracrine factors (30). Nitric oxide (NO), a vasodilator, is tonically produced in the vascular endothelium by the enzyme endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and synthesized from the amino acid substrate l-arginine (38). In normotensive rats, NO inhibition results in acute hypertension and renal vasoconstriction (3–4). The vascular endothelium maintains the balance between vasodilatation and vasoconstriction. In hypertension, renal failure, and diabetes mellitus, diseases characterized by endothelial dysfunction, pharmacological agents that increase nitric oxide production or reduce vasoconstriction may improve renal perfusion (52).

Resveratrol (3,5,4′-trihydroxystilbene), a naturally occurring polyphenol found in red wine and other dietary vegetation, is proposed to have cardioprotective effects as well as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anticancer properties (2). Resveratrol increases eNOS expression and NO production (54,55). Resveratrol has been shown to increase vascular relaxation in endothelial-intact aortic strips and N-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride (l-NAME), a NOS inhibitor, was able to block this effect (12). Bhatt et al. (8) reported resveratrol partially reversed the endothelial dysfunction found in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRs). While SHRs had significantly lower NO levels compared with control Wistar-Kyoto rats, resveratrol treatment increased NO content and increased eNOS protein expression. They also found vascular relaxation in phenylephrine-preconstricted mesenteric arterial rings was significantly improved in SHR by resveratrol.

In addition to stimulating NO, resveratrol is itself a reported antioxidant and scavenger of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (42, 31). Excessive production of ROS contributes to the development of hypertension, and the antihypertensive effect of (chronic) resveratrol may be in part through inhibition of ROS-producing NADPH and xanthine oxidase and through direct actions as a free radical-scavenging antioxidant (41, 27, 11). Resveratrol has also been shown to activate NAD(+)-dependent protein deacetylase SIRT1 (22), which stimulates the mitochondrial free radical scavenging enzyme superoxide dismutase (SOD2). Further, it has been shown that ROS are renal vasoconstrictors (25, 29) and their production in renal afferent arterioles is induced by increased luminal pressure (40). Tempol significantly attenuated this pressure-induced renal vasoconstriction (40). Lai et al. (29) have also shown that superoxide constricts the renal afferent arteriole.

Combined, these data suggest resveratrol may vasodilate by increasing the synthesis of NO and decreasing the vasoconstrictor ROS. Although cardiac hemodynamic effects of acute and chronic resveratrol have been studied, the effects of resveratrol on renal hemodynamics still remain unclear (46). The only published report of the effects of resveratrol on the renal artery are from Gojkovic-Bukarica et al. (18), which investigated the mechanism of resveratrol-induced vasorelaxation of the renal artery in normal and diabetic rats using an in vitro mounted isometric tension preparation.

Vasodilator arachidonic acid products such as prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and PGI2 are renal vasodilators (6, 23, 24). Resveratrol has a complex relationship with arachidonic acid metabolism. The anti-inflammatory actions of resveratrol are suggested to be due to its chronic suppression of cyclooxygenase (COX) expression, induction, activity, and prostanoid production (35). However, it has also been shown to selectively inhibit the COX-1 isoform but not COX-2 (49). Similarly, prostaglandin H synthase (PGHS), a primary enzyme in the biosynthesis of prostaglandins (21), is differentially isoenzyme-specific for resveratrol. The constitutive PGHS-1 is inhibited by resveratrol while PGHS-2 is activated by it (24). In vitro relaxation of porcine coronary arteries has been characterized as partially NO-dependent but unaffected by COX inhibition using indomethacin (32). In contrast, resveratrol has been shown to enhance the antiaggregatory actions of PGE2 and PGI2 (56). Thus it is not really clear if acute resveratrol-mediated renal vasodilation is in part a function of renal vascular prostanoid production. One might build a case for or against such a role, but no data exist in the literature for the renal response.

We hypothesized resveratrol would induce acute renal vasodilation and decrease RVR, mediated through an increase in endothelium-derived NO and a reduction of vasoconstrictive ROS including superoxide. We also tested the possibility that resveratrol may act through stimulation of vasodilatory prostanoids.

METHODS

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River, Wilmington MA) of 225–250 g body wt (bw) were fasted overnight but allowed free access to drinking water. On the day of the experiment, rats were anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection with thiobutabarbital (125 mg/kg bw; Inactin, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Rats were placed on a heated surgical table to maintain constant body temperature (BrainTree Scientific, Braintree, MA). A tracheotomy was performed using PE-240 tubing to allow free breathing of room air. A femoral cut down was performed to cannulate the femoral artery and vein with PE-50 catheters (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). The arterial catheter was connected to an iWorx BP-102 probe with LabScribe2 software (iWorx, Dover, NH) for simultaneous recording of mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR). Pressure transducers were calibrated using a digital, mercury-free Traceable manometer (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburg, PA). The femoral venous catheter was used for a 1-ml supplement of 6% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich), for a constant infusion physiologic saline at a rate of 38 μl/min using a Genie Plus micro-pump (Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT), and for bolus resveratrol administration. A mid-ventral abdominal incision was performed, and the intestines were wrapped in moist gauze and moved to the side of the peritoneal cavity to expose the left kidney. The renal artery and vein were carefully isolated and the renal artery was fitted with a Doppler flow probe (Transonic, Ithaca, NY) connected to a transit-time perivascular flow meter TS-420 model (Transonic) to record RBF via the iWorx system. The rat was draped and allowed to stabilize for 30 min before the running of the experimental protocols.

All protocols and surgical procedures employed in this study were reviewed and approved by the Henry Ford Health System Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals endorsed by the American Physiological Society in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Protocol 1: measurement of renal hemodynamics in response to resveratrol.

We hypothesized resveratrol would act as acute renal vasodilator. To test this, we first ran a resveratrol dose response. Resveratrol (or vehicle) was given as an acute bolus injection (300 μl over 30 s to minimize infusion artifacts) intravenously via the femoral vein catheter. RBF, MAP, and HR were recorded. RVR was calculated by dividing MAP by RBF in units of mmHg·ml·min−1·gram of kidney weight−1 (gkw) hereafter referred to as arbitrary resistance units (ARU). Any small infusion artifact found with the vehicle was subtracted from all paired responses to resveratrol in each experiment. The resveratrol (Sigma-Aldrich) doses were prepared daily. Fifteen milligrams of resveratrol (Sigma-Aldrich) were dissolved in DMSO and diluted with 0.9% saline to 300 μl. Resveratrol is reported to be photosensitive (13). The resveratrol was stored in light-protected Eppendorf tubes wrapped in aluminum foil and kept at 37°C until experimental use. Resveratrol doses of 0 mg/kg (vehicle control), 0.5, 2.0, and 5.0 mg/kg bw were each administered over 30 s. Following each bolus, a recovery period of 15 min was provided. At the conclusion of the protocol, animals were terminated by barbiturate overdose and aortic transection. The left kidney was removed, decapsulated, and weighed to allow for normalization of RBF per gram of kidney weight (n = 8).

Protocol 2: resveratrol and NO-mediated renal vasodilation.

To investigate the role of endothelium-derived NO in mediating resveratrol-induced renal vasodilation, we used NOS inhibition via Nω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride (l-NAME; Sigma-Aldrich). We used a 5.0 mg/kg bw vasodilator dose of resveratrol, as determined in protocol 1. The same surgical procedures were performed as above. Only the vehicle and 5.0 mg/kg resveratrol dose was administered before and 10 min after 10 mg/kg bw l-NAME treatment. We have previously shown that l-NAME at this dose produces complete and sustained inhibition of systemic and renal endothelium-dependent vasodilation (44). l-NAME was administered intravenously, via the femoral vein. RBF, MAP, and HR were recorded. (n = 10).

Protocol 3: resveratrol renal vasodilation with AT1 receptor blockade.

To serve as a control for protocol 4, we administered 5.0 mg/kg bw resveratrol before and after delivering 10 mg/kg bw losartan (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI) since two pharmacological treatments were used in protocol 4 (losartan and l-NAME). We measured RBF, MAP, HR, and RVR in response to resveratrol before and after treatment with losartan (n = 6).

Protocol 4: resveratrol and NO-mediated renal vasodilation after eliminating the l-NAME-induced changes in baseline hemodynamics.

l-NAME given to an anesthetized rat produces significant renal vasoconstriction and acute hypertension due to the unbridled effect of elevated angiotensin II in the absence of NO (3). To minimize these hemodynamic effects of l-NAME in our anesthetized preparation but still evaluate the role of NO, we administered the angiotensin AT1 receptor blocker losartan (Cayman Chemicals) after our control period but before l-NAME was given. This minimized the overall renal hemodynamic and pressor effects of l-NAME treatment to change the baseline. The same surgical procedures were performed as in protocol 2 with the exception of treatment with 10 mg/kg bw losartan given 5 min before l-NAME administration. We measured RBF, MAP, HR, and RVR in response to resveratrol before and after treatment with losartan and l-NAME. (n = 11).

Protocol 5: resveratrol and scavenging of superoxide anion.

We hypothesized resveratrol-induced renal vasodilation may be mediated in part through NO scavenging of superoxide, reducing its inherit vasoconstriction. The ROS superoxide anion reacts quickly with NO in the vasculature, producing peroxynitrite and depleting NO. To investigate the role of superoxide scavenging properties of resveratrol, we administered 5.0 mg/kg bw resveratrol before and after delivering 1.0 mg/kg bw tempol (Sigma-Aldrich), a superoxide dismutase mimetic. Thus if tempol scavenged superoxide before the resveratrol bolus, resveratrol-induced renal vasodilation should be diminished. (n = 7).

Protocol 6: resveratrol and vasodilatory prostanoids.

To investigate whether resveratrol-induced vasodilation was mediated in part via vasodilator prostaglandins, rats were pretreated with the nonselective COX inhibitor indomethacin (Sigma-Aldrich); 4 mg/kg bw the day before the experiment, 4 mg/kg bw again on the day of the experiment, and 2 mg/kg bw just before the surgery as previously described (20). Indomethacin was dissolved in DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich). Surgical procedures were performed as above using only vehicle and 5.0 mg/kg resveratrol before and 10 min after 10 mg/kg l-NAME treatment in indomethacin-pretreated animals. RBF, MAP, and HR were recorded. RVR was calculated. (n = 10).

Analysis.

For dose responses (protocol 1), the changes in RBF minus any vehicle infusion artifact and the changes in RVR were analyzed using ANOVA for repeated measures using a Bonferroni adjustment of the P value as a post hoc test for multiple comparisons. All statistically significant responses are listed only as an adjusted P < 0.05 for Fig. 1. For comparisons of the resveratrol response between untreated controls and after treatment (protocols 2–6), we used a paired Student's t-test with an α acceptance at 0.05, and n values were chosen to provide a power of at least 0.8.

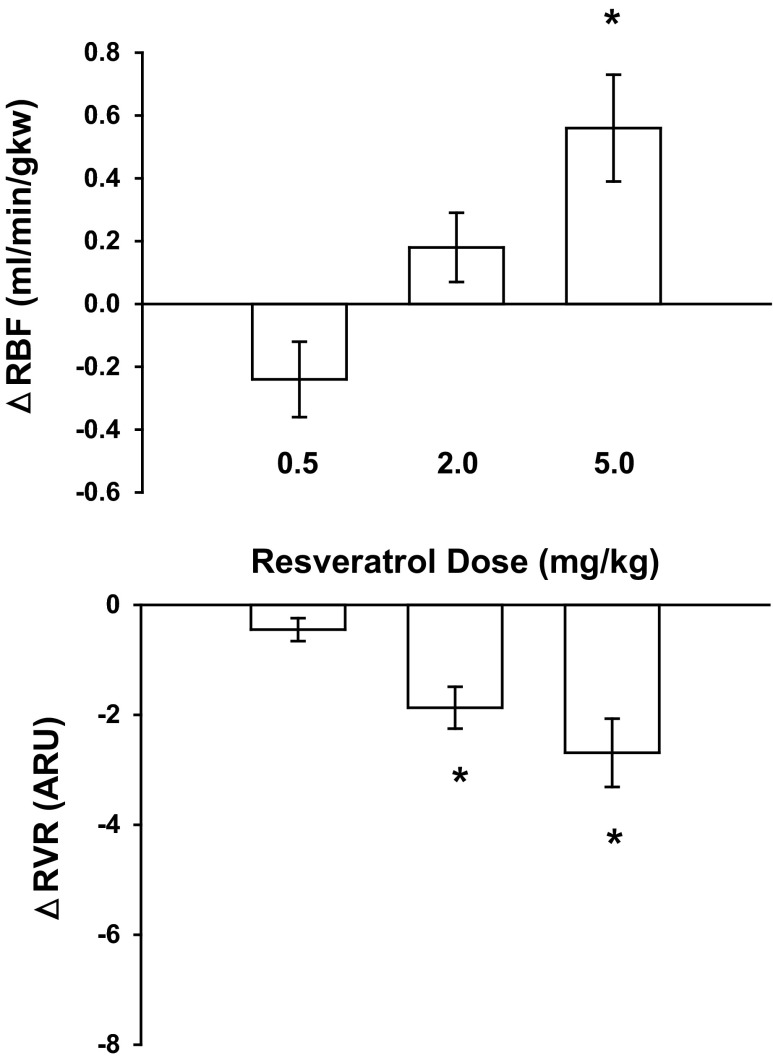

Fig. 1.

Effect of a dose response by resveratrol on renal blood flow (RBF) and renal vascular resistance (RVR; n = 8); 5.0 mg/kg resveratrol increased RBF by 8% and decreased RVR by 18%. ARU, arbitrary resistance units; gkw, gram of kidney weight. *P < 0.05, statistically significant responses.

RESULTS

Protocol 1: measurement of renal hemodynamics in response to resveratrol.

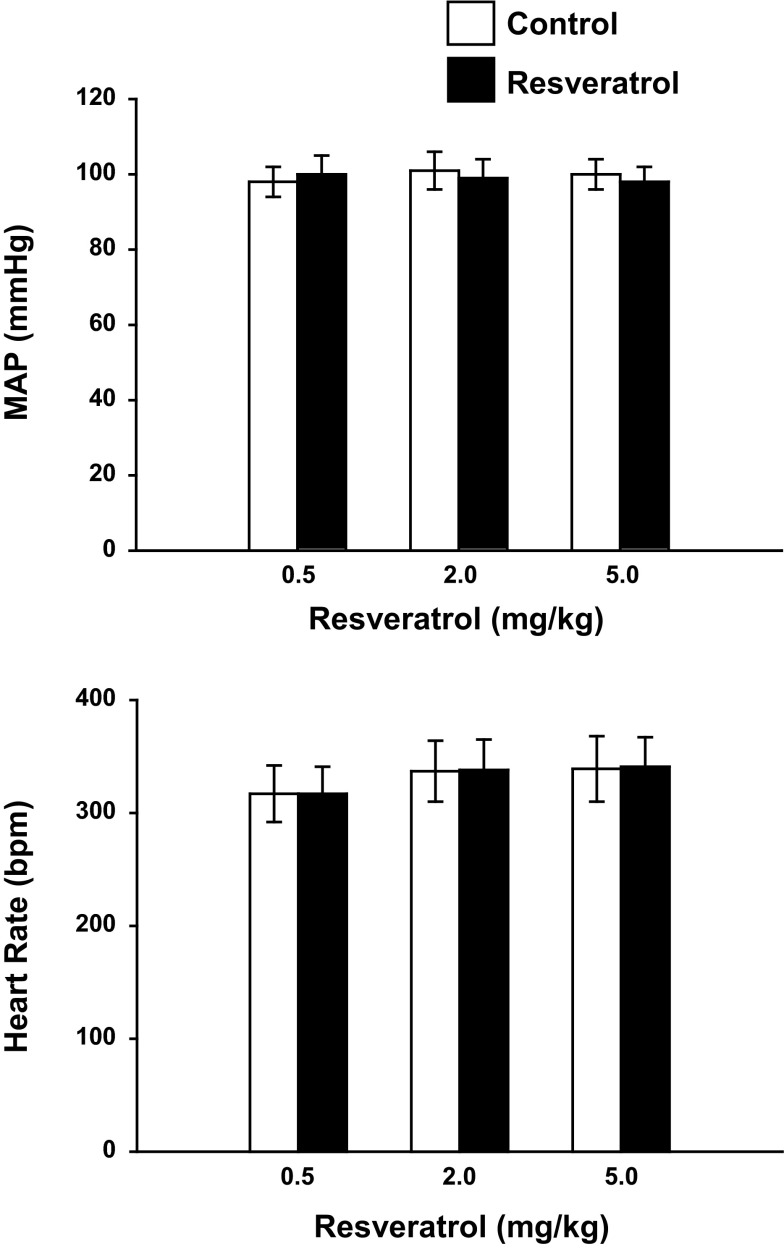

A significant increase in RBF was observed with 5.0 mg/kg resveratrol (Fig. 1). At this dose RBF increased 8% from 6.98 ± 0.42 to 7.54 ± 0.17 ml·min−1·gkw−1 (n = 8; P < 0.05) and RVR decreased by 18% from 15.00 ± 1.65 to 12.32 ± 1.20 ARU (P < 0.05). Neither MAP nor HR was changed in response to resveratrol (Fig. 2). The increase in RBF and decrease in RVR in response to resveratrol were transient responses, and resveratrol-induced changes in RBF and RVR returned to preinjection values. Thus we chose a bolus dose of 5.0 mg/kg bw for all subsequent protocols to investigate the mechanism of vasodilation.

Fig. 2.

Effect of acute resveratrol on mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR; n = 8). Acute resveratrol had no effect on MAP or HR; bpm, beats/min.

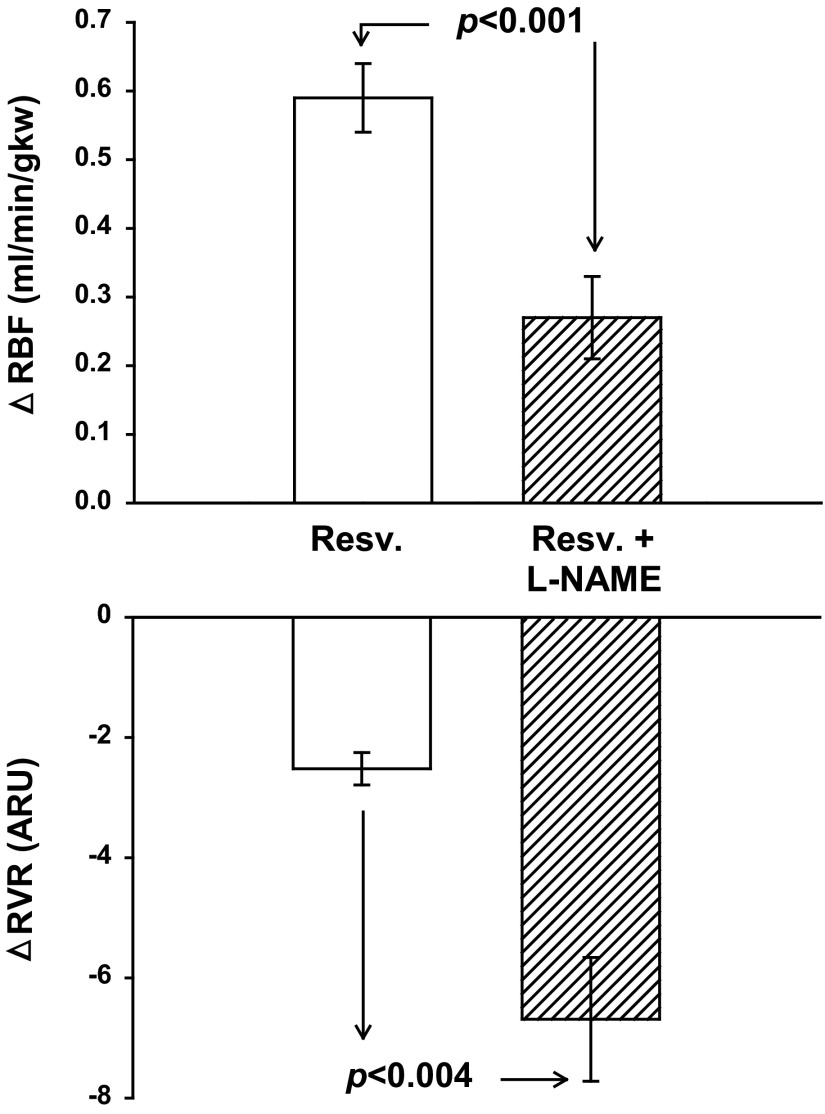

Protocol 2: resveratrol and NO-mediated renal vasodilation.

As in protocol 1, 5.0 mg/kg resveratrol increased RBF 8% from 7.09 ± 0.44 to 7.68 ± 0.46 ml·min−1·gkw−1 (P < 0.001). Likewise, RVR decreased 17% from 14.65 ± 0.92 to 12.14 ± 0.82 ARU (P < 0.001). MAP remained unchanged at 101 ± 3 to 98 ± 2 mmHg, and HR was unaffected [327 ± 16 beats/min (bpm)]. Following administration of l-NAME, basal RBF decreased from 7.09 ± 0.44 to 4.36 ± 0.32 ml·min−1·gkw−1 (P < 0.0001), RVR increased from 14.65 ± 0.92 to 33.41 ± 2.63 ARU (P < 0.0001), MAP increased from 101 ± 3 to 139 ± 6 mmHg (P < 0.0001), and HR decreased from 327 ± 16 to 274 ± 11 bpm (P < 0.003). l-NAME significantly diminished but did not eliminate resveratrol-induced renal vasodilation. Resveratrol-induced vasodilation increased RBF from 4.36 ± 0.32 to 4.63 ± .32 ml·min−1·gkw−1 (P < 0.001), an absolute change of 0.27 ± 0.06 ml·min−1·gkw−1, which was only half the response seen before l-NAME (Fig. 3). l-NAME-treated rats had a significant decrease in RVR with resveratrol from 33.41 ± 2.63 to 26.72 ± 2.27 ARU. After l-NAME administration, resveratrol did not affect HR, but it significantly decreased MAP from 139 ± 6 to 131 ± 6 mmHg (P < 0.003). Overall, we found l-NAME reduced resveratrol-induced vasodilation by 54% suggesting a significant component of resveratrol-induced vasodilation is mediated in part by NO.

Fig. 3.

Effect of nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibition with N-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME) on RBF and RVR on resveratrol-induced vasodilation (n = 7). l-NAME reduced the increase in RBF in response to resveratrol by 54% (P < 0.001) and significantly decreased the change in RVR by 20% (P < 0.004).

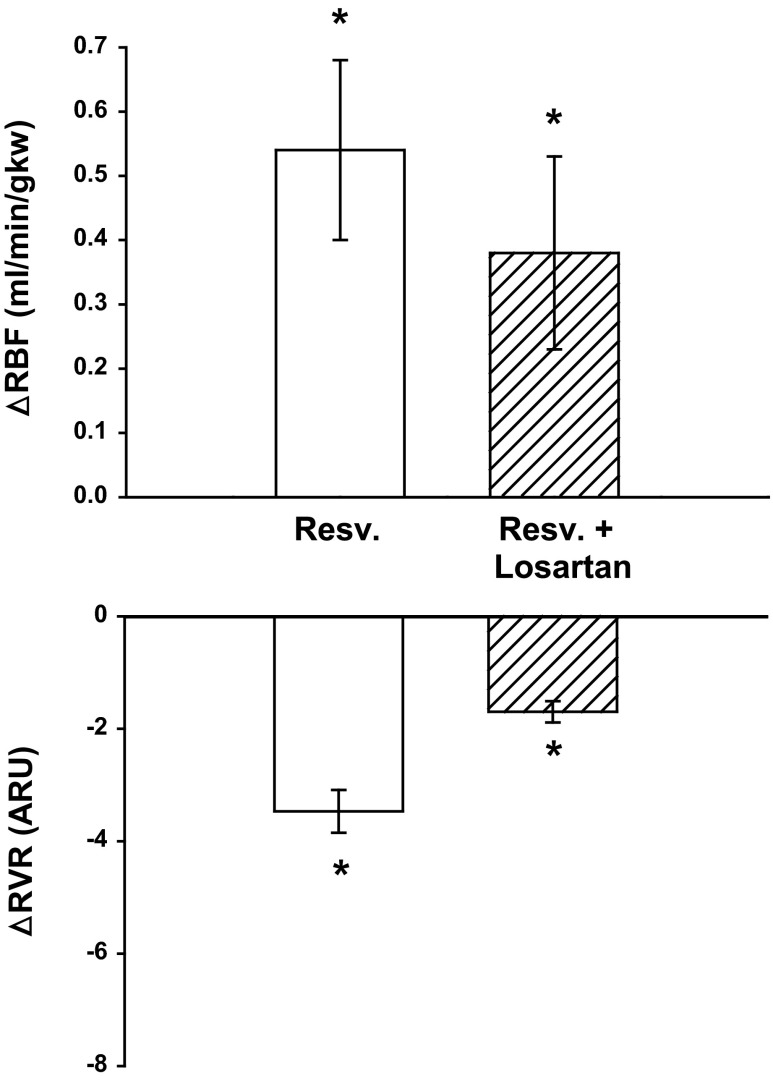

Protocol 3: resveratrol renal vasodilation with AT1 receptor blockade.

We expected resveratrol-induced renal vasodilation would decrease due to the vasodilatory actions of losartan. 5.0 mg/kg resveratrol increased RBF 7.5% from 7.12 ± 0.29 to 7.66 ± 0.42 ml·min−1·gkw−1 (n = 6, P < 0.01) and decreased RVR 21% from 15.46 ± 85 to 12.24 ± 0.84 ARU (P < 0.001; Fig. 4). Following administration of 10 mg/kg bw losartan, baseline RBF increased 16% from 7.12 ± 0.29 to 8.27 ± 0.32 ml·min−1·gkw−1 (P < 0.0001) and RVR decreased 24% from 15.46 ± 0.85 to 11.80 ± 0.74 ARU (P < 0.0001), MAP decreased 12% from 109 ± 4 to 97 ± 4 mmHg (P < 0.0001), and HR was unchanged from 312 ± 19 to 309 ± 23 bpm. Even after administration of losartan, 5.0 mg/kg resveratrol still significantly increased RBF 4.5% from 8.27 ± 0.32 to 8.65 ± 0.44 ml·min−1·gkw−1 (P < 0.049) and RVR decreased 14% from 11.80 ± 0.74 to 10.10 ± 0.90 ARU (P < 0.003).

Fig. 4.

Effect of AT1receptor inhibition with losartan on resveratrol-induced renal vasodilation (n = 6). With losartan treatment, resveratrol-induced vasodilation still increased RBF 4.5%. * Represents a significant change from baseline. See text for P values.

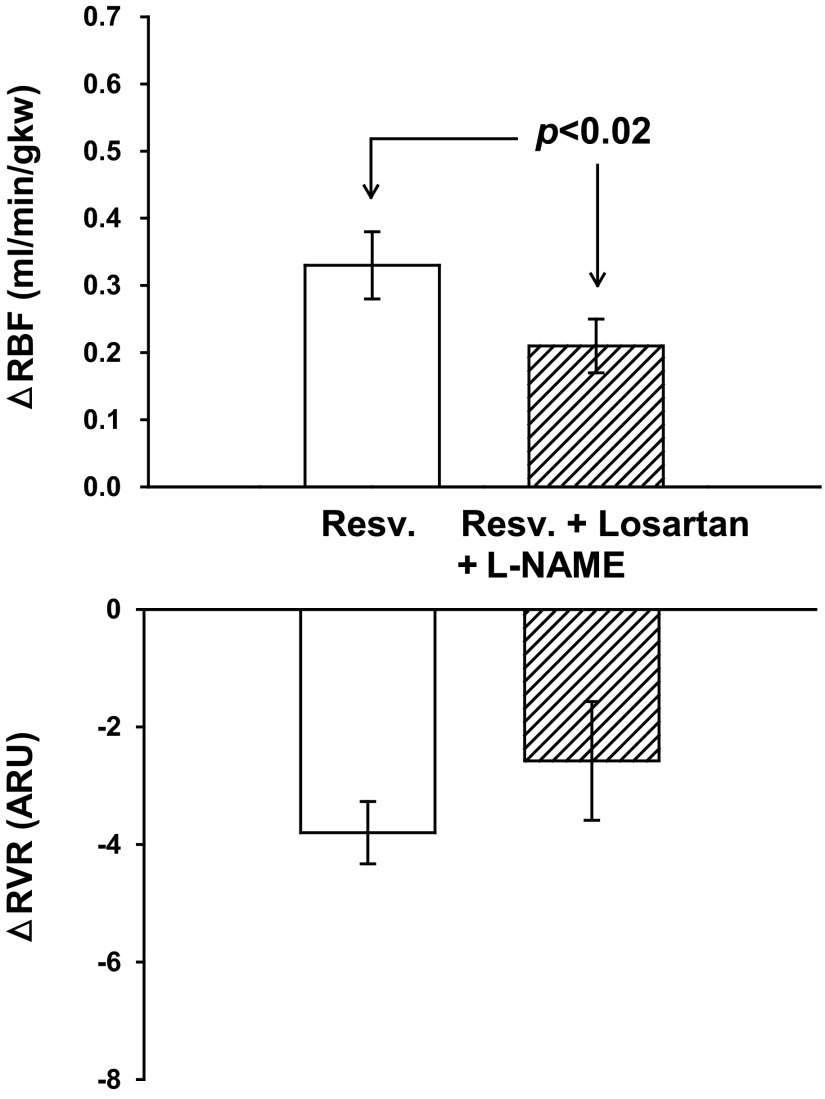

Protocol 4: resveratrol and NO-mediated renal vasodilation after eliminating the l-NAME-induced changes in baseline hemodynamics.

Under control conditions, resveratrol increased RBF (Fig. 5) from 6.58 ± 0.36 to 6.91 ± 0.39 ml·min−1·gkw−1 (P < 0.0001) and RVR decreased from 18.27 ± 1.44 to 14.47 ± 1.10 ARU (P < 0.0001). Losartan diminished the renal hemodynamic changes induced by l-NAME treatment (seen in protocol 2) by preventing the significant decrease in RBF. Basal RBF was 6.58 ± 0.36, and after both losartan and l-NAME, the baseline was 6.16 ± 0.53 ml·min−1·gkw−1. MAP was unchanged 123 ± 4 mmHg, but HR fell significantly from 304 ± 12 to 263 ± 14 bpm (P < 0.001). Similar to the results of protocol 2 with l-NAME alone, NO inhibition in the presence of losartan significantly reduced the resveratrol-induced renal vasodilation from an increase in RBF of 0.33 ± 0.05 to just 0.21 ± 0.04 ml·min−1·gkw−1 (P < 0.02). RVR decreased from 21.29 ± 1.72 to 18.70 ± 2.13 ARU (P < 0.03; Fig. 5). MAP and HR were unchanged in response to resveratrol. Overall, angiotensin receptor blockade prevented the hemodynamic and pressor effects associated with NOS inhibition. Resveratrol-induced renal vasodilation was significantly reduced by NOS inhibition, similar to the results of protocol 2.

Fig. 5.

Effect of NOS inhibition with l-NAME after AT1 receptor inhibition with losartan on resveratrol-induced renal vasodilation and RVR (n = 11). Losartan and l-NAME reduced the resveratrol-induced increase in RBF by 36%.

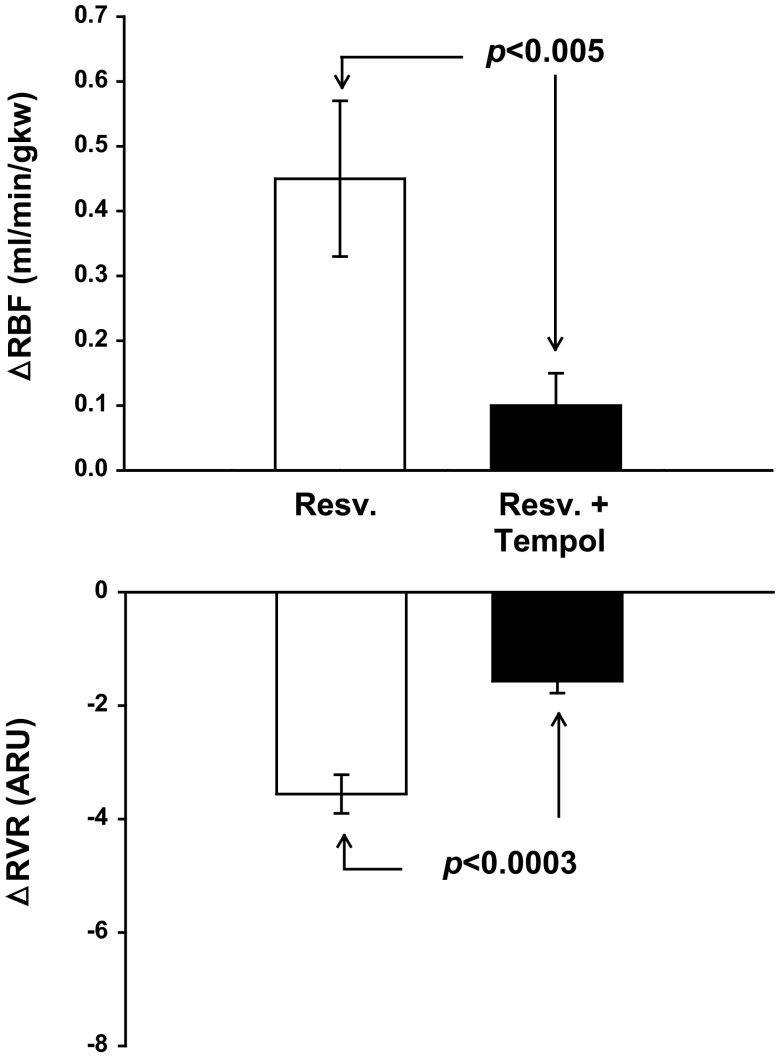

Protocol 5: resveratrol and scavenging of superoxide anion.

Resveratrol increased RBF 8% (from 5.91 ± 0.32 to 6.36 ± 0.12 ml·min−1·gkw−1; n = 7; P < 0.001) and decreased RVR 19% (from 18.83 ± 1.37 to 15.27 ± 1.37 ARU; Fig. 6) under control conditions. Tempol alone increased RBF 9% (from 5.91 ± 0.32 to 6.43 ± 0.28 ml·min−1·gkw−1; P < 0.005), decreased RVR 20% (18.83 ± 1.37 to 15.01 ± 0.77 ARU P < 0.006), decreased MAP 14 mmHg (from 109 ± 2 to 95 ± 3 n = 7 P < 0.001), and decreased HR 15% (327 ± 15 to 277 ± 15 bpm; P < 0.003). Tempol treatment completely blocked the resveratrol-induced increase in RBF (a decrease of 78% in vasodilation from 0.45 ± 0.12 to 0.10 ± 0.05 ml·min−1·gkw−1; P < 0.03), and the decrease in RVR in response to resveratrol was only 44% that of the control response (3.56 ± 0.34 vs. 1.57 ± 0.21 ARU; P < 0.006). Thus by scavenging superoxide, the resveratrol-induced vasodilation was completely eliminated.

Fig. 6.

Effect of superoxide scavenging with tempol on resveratrol-induced renal vasodilation and RVR (n = 7). Tempol eliminated resveratrol-induced vasodilation.

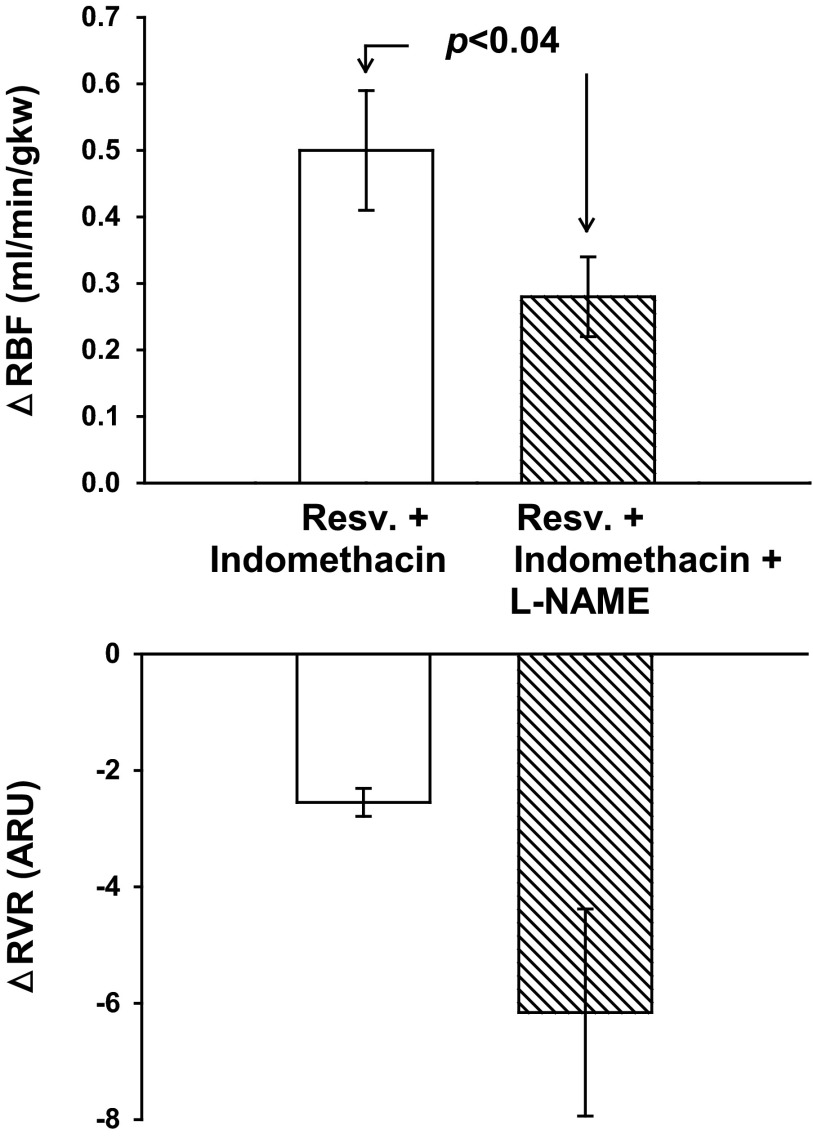

Protocol 6: resveratrol and vasodilatory prostanoids.

In indomethacin-treated rats, a bolus of 5.0 mg/kg resveratrol resulted in a significant increase in RBF (Fig. 7) from 6.77 ± 0.18 to 7.17 ± 0.23 ml·min−1·gkw−1 (P < 0.0004), similar to the change seen as in protocol 2. Resveratrol also decreased RVR from 15.08 ± 0.50 to 12.53 ± 0.49 ARU (P < 0.0001). In indomethacin-treated rats, l-NAME increased MAP from 100 ± 3 to 138 ± 5 mmHg (P < 0.0001), decreased HR from 331 ± 10 to 265 ± 11 bpm (P < 0.001), and increased RVR from 15.08 ± 0.50 to 31.77 ± 3.81 ARU (P < 0.002). As in protocol 2, l-NAME significantly blunted renal vasodilation seen in response to resveratrol by 44%, from 0.50 ± 0.09 to 0.28 ± 0.06 ml·min−1·gkw−1 (n = 10; P < 0.044). Resveratrol also decreased RVR from 31.77 ± 3.81 to 25.62 ± 2.51 ARU (P < 0.007; Fig. 7). In indomethacin-treated rats, resveratrol did not affect heart rate but significantly decreased MAP from 100 ± 3 to 95 ± 3 mmHg (P < 0.001) and after l-NAME decreased MAP from 138 ± 5 to 131 ± 6 mmHg (P < 0.003). Overall, COX inhibition did not change the renal hemodynamic response to resveratrol or its attenuation by l-NAME.

Fig. 7.

Effect of cyclooxygenase inhibition with indomethacin and NOS inhibition on resveratrol-induced renal vasodilation and RVR (n = 10). Similar to controls, indomethacin did not change resveratrol-induced vasodilation. With indomethacin treatment, l-NAME reduced resveratrol-induced vasodilation by 44% (P < 0.04).

DISCUSSION

Very little is known about the renal hemodynamic effects of resveratrol. In this study we present in vivo data to support our hypothesis that resveratrol is a renal vasodilator. In particular the mechanisms by which resveratrol functions as a renal vasodilator include 1) increased NO production and/or NO availability, and 2) subsequent reduction of vasoconstrictor ROS, presumably superoxide. Resveratrol treatment significantly increased RBF and with a concomitant decrease in RVR. Our findings are consistent with the literature that resveratrol acutely increases NO synthesis. Wallerath et al. (54, 55) demonstrated resveratrol increases eNOS expression and NO production in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Here we demonstrate resveratrol is capable of inducing renal vasodilation in normal rats by an endothelial dependent, NO-mediated pathway. However, only about half of the resveratrol-induced renal vasodilation was blocked by competitive NOS inhibition. This is similar to the in vitro results of Li et al. (32) using isolated porcine coronary arteries. They found that either NOS inhibition or de-endothelization of the preparation only partially reversed the resveratrol-induced vascular relaxation.

One concern of blocking NOS using l-NAME in an in vivo protocol is the significant shift in the hemodynamic baselines. l-NAME given to an anesthetized rat produces significant renal vasoconstriction and acute hypertension due to the unbridled effect of elevated angiotensin II in the absence of NO (3). To serve as a control, in protocol 4, we solely treated with losartan because in protocol 5 we treated with both losartan and l-NAME to minimize hemodynamic changes. In protocol 4, we found both in the control and with losartan treatment, resveratrol elicited significant vasodilation, albeit, the vasodilation magnitude was decreased with losartan treatment, as would be expected. In protocol 4, we controlled for the hemodynamic and pressor effects of l-NAME. After the control period, we administered the AT1 antagonist losartan (17). Previous work has shown losartan was able to diminish the decreased RBF due to l-NAME (45). Under these conditions, we replicated our results of diminished resveratrol-induced renal vasodilation after NOS inhibition with the inclusion of losartan eliminating gross changes in the hemodynamic baseline induced by l-NAME. Collectively, these data also support the results in protocol 2 that resveratrol-induced renal vasodilation is at least partially NO dependent, as evident during NOS inhibition.

Nitric oxide and superoxide interact and scavenge each other in a balance that controls endothelial function (26). With approximately half of resveratrol-induced renal vasodilation explained by an endothelial NO-dependent mechanism, we tested whether this renal vasodilation is mediated through scavenging of ROS by reducing the vasoconstrictor effects of superoxide. Besides the ROS scavenging of NO, resveratrol has been shown to directly scavenge ROS (31, 48). Resveratrol treatment has been shown to dowregulate NOX4 expression (47). Since our protocol was an acute experiment, expression is unlikely to be a significant factor. Our idea was that resveratrol may be acting as an antioxidant, either through its stimulation of NO synthesis, or independently acting as a ROS scavenger, or both. When we delivered resveratrol after administration of the superoxide dismutase mimetic tempol, renal vasodilation was completely blocked. This finding suggests resveratrol may increase RBF through both increasing acute NO release as well as directly scavenging free radicals. This could explain why tempol was more efficacious in blocking the resveratrol-induced vasodilatory response than just NOS inhibition alone. Resveratrol-induced renal vasodilation mediated by scavenging ROS is a novel finding under normal basal conditions. In our protocol, we do not have direct measurements of NO synthesis in the renal resistance vessels. Thus we do not really know if the resveratrol induces increased NO synthesis or alternatively exerts a NOS-dependent vasodilation resulting from a mechanism involving direct resveratrol scavenging of ROS, which in turn would allow increased NO bioavailability without actually increasing NOS activity or NO production (or both of these possibilities).

This scavenging and its effect on renal hemodynamics may have therapeutic potential. Increased oxidative stress and reactive oxygen species and the subsequent endothelial dysfunction are often found in hypertension (1) and other renal diseases (16).

Following tempol treatment in our protocol, we witnessed an increase in RBF. It should be noted that the involvement of ROS in regulation of renal hemodynamics during resting basal conditions is a controversial topic. Conflicting studies debate the role ROS contributes toward resting vasomotor tone in the kidney. Some studies support ROS in having a tonic vasoconstricting effect as evident in knockout and pharmacological inhibition experiments (19, 33, 34). Conversely, different studies demonstrate tempol does not alter renal hemodynamics in normotensive rats (42, 28). Confounding this issue is different treatment dosages and RBF measurements taken over different time periods make direct comparisons difficult.

One final closing thought concerning the interpretation of tempol protocol data (protocol 5) should be highlighted. It is straightforward to recognize when the vasculature is in a vasodilated state, this will decrease the dilator response to vasodilatory agent. In our data tempol increased basal RBF 9% and virtually abolished resveratrol-induced vasodilation. However, in protocol 4 we found losartan increased basal RBF 16%, an amount greater than with tempol, and still resveratrol was able to significantly vasodilate following losartan treatment. In both protocols, the pharmacological treatments (losartan or tempol) increased basal RBF, but there were divergent vasodilatory outcomes in response to resveratrol. Overall, this suggests the reduced vasodilation in response to resveratrol during tempol treatment is not merely due to dilated state of the vessel.

Previously, we have shown acute NOS inhibition unmasked renal vasoconstriction with COX-2 inhibition, suggesting that the influence of COX-2-derived vasodilator eicosanoids is exaggerated to maintain renal perfusion, compensating for the acute loss of NO (5). However, in vitro fibroblast culture studies have shown resveratrol may inhibit phospholipase A2 activity and PGE2 synthesis (36). In a cancer line, resveratrol has been suggested to inhibit COX-2 (57). However, another study has shown resveratrol increases COX mRNA levels (10). Since resveratrol-induced renal vasodilation was not completely eliminated by NOS inhibition, we considered the possible influence of prostanoids in resveratrol-induced renal vasodilation by pretreating rats with indomethacin. However, our results suggest no involvement of prostanoids in acute resveratrol-induced vasodilation. In vitro relaxation of porcine coronary arteries has been characterized as partially NO dependent but similar to our data unaffected by COX inhibition using indomethacin (32). In contrast, resveratrol has been shown to enhance the anti-aggretory actions of PGE2 and PGI2 (56) suggesting some acute interaction with the actions of prostaglandin. There are no existing data for an interaction between resveratrol and vasodilator prostaglandins in the renal vasculature. Overall these data generally support our findings that resveratrol-induced renal vasodilation is not influenced by vasodilator prostanoids.

The acute renal vasodilation we observed in response to resveratrol administration was a transient event. Peak vasodilation took place within 30 s following the resveratrol bolus, and blood flow gradually returned to prebolus values within a few of minutes. In human subjects treated with oral 14C-resveratrol (53), absorption of resveratrol is ∼70%, and it has a plasma half-life of 9.2 ± 0.6h. Boocock et al. (9) found peak plasma levels of resveratrol at 539 ± 384 ng/ml, in healthy human volunteers, 1.5 h after consuming a 5-g dose of resveratrol. Our transient increase in RBF and decrease in RVR may be explained in part due the metabolism, distribution and possibly excretion of resveratrol.

We did not observe any significant changes in MAP with acute resveratrol administration in normal rats under control conditions. However, in both l-NAME and indomethacin plus l-NAME groups, we observed resveratrol significantly decreased MAP. Other groups have reported that resveratrol may reduce blood pressure. Thandapilly et al. (51) reported grape powder in SHRs significantly decreased blood pressure (200 ± 4 vs.190 ± 2 mmHg with treatment). In diabetic patients, resveratrol supplements for 3 mo (250 mg/day) lowered systolic pressure from 139 ± 16 to 127 ± 15 mmHg (7). Bhatt et al. (8) showed that resveratrol treatment (5 mg/kg/day) attenuated hypertension development in SHR as indicated by lower MAP in resveratrol-treated SHR compared with control SHR (161 ± 2 vs. 180 ± 1 mmHg, respectively). These are, however, chronic studies and do not reflect the immediate changes we see. The explanation for why the treated animals responded but the controls did not remains elusive, though the changes in MAP we report are relatively small.

Although the data we present support either increased NO production and/or NO bioavailability, there may be a possible alternative which might explain NO-mediated resveratrol induced renal vasodilation. Park et al. (39) found resveratrol inhibits phosphodiesterase (PDE) isoforms 1, 3, and 4. PDE-4 is expressed in endothelial cells, and within the kidney several PDE isoforms are present including PDE-4 (37). In a dog model, Tanahashi et al. (50) observed that intracranial arterial infusion of rolipram, a selective phosphodiesterase IV inhibitor, increased renal blood flow. Dalaklioglu and Ozbey (14) found, in isolated corpus cavernosum, resveratrol produced a concentration-dependent relaxation that was significantly attenuated by removal of the endothelium, l-NAME, or the soluble guanylyl cyclase inhibitor 1H-[1, 2,4]oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one (ODQ), suggesting a cGMP-mediated effect (14). As in our results, the COX inhibitor indomethacin had no effect (14). El-Mowafy (15) found that in sheep coronary arteries resveratrol increased cGMP formation threefold, and this was not abrogated by the phosphodiesterase inhibitor IBMX. Further, resveratrol activated guanylyl cyclase in the particulate, but not in the soluble membrane fraction. He proposed that resveratrol increases cGMP in coronary arteries partially by activation of particulate guanylyl cyclase (15). Thus resveratrol could act via its second messenger cGMP through a direct effect on nitric oxide synthesis, through activation of particulate guanylyl cyclase, through inhibition of phosphodiesterase(s), or through some combinations of all these pathways. It remains to be shown if acute resveratrol increases renal vasodilation through one or all of these actions.

Because our study is based on acute and transient responses to a bolus injection of resveratrol, it does not lend itself to measuring any metric for NO or O2− levels in a meaningful manner. Both these molecules are short-lived and highly reactive. Thus we have not attempted to quantify such changes. Lastly, another possible limitation of this study is that tempol increased RBF. The resultant vasodilation by tempol may have masked the actions of vasodilatory actions of resveratrol, yet with losartan treatment there was vasodilation and resveratrol still induced significant vasodilation.

In summary, our findings suggest acute resveratrol treatment influences renal hemodynamics inducing a significant increase in RBF and decreased RVR. The mechanism of renal vasodilation is partially mediated by either stimulating endothelial-NO production and/or increasing NO availability and through a reduction of endogenous reactive oxygen species; either due to the increased NO synthesis or a direct ROS scavenging by resveratrol itself. Resveratrol-induced renal vasodilation is not influenced by COX metabolism and vasodilatory prostanoids.

GRANTS

This research was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant 5P01-HL-090550–04.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: K.L.G. and W.H.B. conception and design of research; K.L.G. performed experiments; K.L.G. and W.H.B. analyzed data; K.L.G. and W.H.B. interpreted results of experiments; K.L.G. and W.H.B. prepared figures; K.L.G. and W.H.B. drafted manuscript; K.L.G. and W.H.B. edited and revised manuscript; K.L.G. and W.H.B. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank D'Anna Potter for technical instruction and training. K. Gordish is a predoctoral student and a member of the Wayne State University School of Medicine, Department of Physiology PhD program.

REFERENCES

- 1.Araujo M, Wilcox C. Oxidative stress in hypertension: role of the kidney. Antioxid Redox Signal 20: 74–101,2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baur JA, Sinclair DA. Therapeutic potential of resveratrol: the in vivo evidence. Nat Rev Drug Discov 6: 493–506, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baylis C, Harton P, Engels K. Endothelium derived relaxing factor controls renal hemodynamics in normal rat kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 875–881,1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beierwaltes WH, Sigmon DH, Carretero OA. Endothelium modulates renal blood flow but not autoregulation. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 262: F943–F949, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beierwaltes WH. Cyclooxygenase-2 products compensate for inhibition of nitric oxide regulation of renal perfusion. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 283: F68–F72, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breyer MD, Breyer RM. G protein-coupled prostanoids receptors and the kidney. Annu Rev Physiol 63: 579–605, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhatt JK, Thomas S, Nanjan MJ. Resveratrol supplementation improves glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nutr Res 32: 537–541, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhatt SR, Lokhandwala MF, Banday AA. Resveratrol prevents endothelial nitric oxide synthase uncoupling and attenuates development of hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Eur J Pharmacol 30: 258–264, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boocock DJ, Faust GE, Patel KR, Schinas AM, Brown VA, Ducharme MP, Booth TD, Crowell JA, Perloff M, Gescher AJ, Steward WP, Brenner DE. Phase I dose escalation pharmacokinetic study in healthy volunteers of resveratrol, a potential cancer chemopreventive agent. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 16: 1246–1252, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Botden IP, Oeseburg H, Durik M, Leijten FP, Van Vark-Van Der Zee LC, Musterd-Bhaggoe UM, Garrelds IM, Seynhaeve AL, Langendonk JG, Sijbrands EJ, Danser AH, Roks AJ. Red wine extract protects against oxidative-stress-induced endothelial senescence. Clin Sci (Lond) 123: 499–507, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burkitt MJ, Duncan J. Effects of trans-resveratrol on copper-dependent hydroxyl-radical formation and DNA damage: evidence for hydroxyl-radical scavenging and a novel, glutathione-sparing mechanism of action. Arch Biochem Biophys 381: 253–263, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen CK, Pace-Asciak CR. Vasorelaxing activity of resveratrol and quercetin in isolated rat aorta. Gen Pharmacol 27: 363–366, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corduneanu O, Patricia Janeiro P, Brett AM. On the electrochemical oxidation of resveratrol. Electroanalysis 18: 757–762, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dalaklioglu S, Ozbey G. The potent relaxant effect of resveratrol in rat corpus cavernosum and its underlying mechanisms. Int J Impot Res 25: 188–193, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El-Mowafy AM. Resveratrol activates membrane-bound guanylyl cyclase in coronary arterial smooth muscle: a novel signaling mechanism in support of coronary protection. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 15: 1218–1224, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forbes JM, Coughlan MT, Cooper ME. Oxidative stress as a major culprit in kidney disease in diabetes. Diabetes 57: 1446–1454, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gandhi SK, Ryder DH, Brown NJ. Losartan blocks aldosterone and renal vascular responses to angiotensin II in humans. Hypertension 28: 961–966, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gojkovic-Bukarica L, Kanjuh V, Novakovic R, Protic D, Cvejic J, Atanackovic M. The differential effect of resveratrol on the renal artery of normal and diabetic rats. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol 13, Suppl 1: A48, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haque MZ, Majid DS. Assessment of renal functional phenotype in mice lacking gp91PHOX subunit of NAD(P)H oxidase. Hypertension 43: 335–340, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harding P, Carretero OA, Beierwaltes WH. Chronic cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition blunts low sodium-stimulated renin without changing renal haemodynamics. J Hypertens 18: 1107–1113, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hata AN, Breyer RM. Pharmacology and signaling of prostaglandin receptors: multiple roles in inflammation and immune modulation. Pharmacol Ther 103: 147–166, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hosoda R, Kuno A, Hori YS, Ohtani K, Wakamiya N, Oohiro A, Hamada H, Horio Y. Differential cell-protective function of two resveratrol (trans-3,5,4′-trihydroxystilbene) glycosides against oxidative stress. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 344: 124–132, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jackson EK, Heidemann HT, Branch RA, Gerkens JF. Low dose intrarenal infusion of PGE2, PGI2, and 6-keto-PGE1 vasodilate the in vivo rat kidney. Circ Res 51: 67–72, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson JL, Maddipati KR. Paradoxical effects of resveratrol on the two prostaglandin synthases. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 56: 131–143, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Just A, Whitten C, Arendshorst W. Reactive oxygen species participate in acute renal vasoconstrictor responses induced by ETA and ETB receptors. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F719–F728, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalinowski MD, Dobrucki LW, Brovkovych MS, Malinski V, Tadeusz M. Increased nitric oxide bioavailability in endothelial cells contributes to the pleiotropic effect. Circulation 105: 933–938, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karlssol J, Emgrad M, Burkitt MJ. Trans-resveratrol protects embryonic mesencephalic cells from tert-butyl hydroperoxide: electron paramagnetic resonance spin trapping evidence for a radical scavenging mechanism. J Neurochem 75: 141–150, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kopkan L, Castillo A, Navar L, Majid D. Enhanced superoxide generation modulates renal function in ANG II-induced hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F80–F86, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai EY, Wellstein A, Welch WJ, Wilcox CS. Superoxide modulates myogenic contractions of mouse afferent arterioles. Hypertension 58: 650–656, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lamas S, Rodriguez-Puyol D. Endothelium and the kidney endothelial control of vasomotor tone: the kidney perspective. Semin Nephrol 32: 156–166, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leonard SS, Xia C, Jiang BH, Stinefelt B, Klandorf H, Harris GK, Shi X. Resveratrol scavenges reactive oxygen species and effects radical-induced cellular responses. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 309: 1017–1026, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li HF, Tian ZF, Qui XQ, Wu JX, Zhang P, Jia ZJ. A study of mechanisms involved in vasodilation induced by resveratrol in isolated porcine coronary artery. Physiol Res 55: 365–372, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lopez B, Salom MG, Arregui B, Valero F, Fenoy FJ. Role of superoxide in modulating the renal effects of angiotensin II. Hypertension 42: 1150–1156, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Majid DS, Nishiyama A. Nitric oxide blockade enhances renal responses to superoxide dismutase inhibition in dogs. Hypertension 39: 293–297, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martinez J, Moreno JJ. Effect of resveratrol, a natural polyphenolic compound, on reactive oxygen species and prostaglandin production. Biochem Pharmacol 59: 865–870, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moreno JJ. Resveratrol modulates arachidonic acid release, prostaglandin synthesis, and 3T6 fibroblast growth. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 294: 333–338, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Netherton SJ, Maurice DH. Vascular endothelial cell cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases and regulated cell migration: implications in angiogenesis. Mol Pharmacol 67: 263–272, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palmer RM, Ashton DS, Moncada Palmer S. Vascular endothelial cells synthesize nitric oxide from l-arginine. Nature 333: 664–666, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park SJ, Ahmad F, Philp A, Baar K, Williams T, Luo H, Ke H, Rehmann H, Taussig R, Brown AL, Kim MK, Beaven MA, Burgin AB, Manganiello V, Chung JH. Resveratrol ameliorates aging-related metabolic phenotypes by inhibiting cAMP phosphodiesterases. Cell 148: 421–433, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ren Y, D'Ambrosio MA, Liu R, Pagano PJ, Garvin JL, Carretero OA. Enhanced myogenic response in the afferent arteriole of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298: H1769–H1775, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodrigo R, Gil D, Miranda-Merchak A, Kalantzidis G. Antihypertensive role of polyphenols. Adv Clin Chem 58: 225–254, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rodrigo R, Miranda A, Vergara L. Modulation of endogenous antioxidant system by wine polyphenols in human disease. Clin Chim Acta 412: 410–424, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schnackenberg CG, Welch WJ, Wilcox CS. Normalization of blood pressure and renal vascular resistance in SHR with a membrane-permeable superoxide dismutase mimetic: role of nitric oxide. Hypertension 32: 59–64, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sigmon DH, Beierwaltes WH. Angiotensin II: nitric oxide interaction and the distribution of blood flow. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 265: R1276–R1283, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sigmon DH, Beierwaltes WH. Renal nitric oxide and angiotensin II interaction in renovascular hypertension. Hypertension 22: 237–242, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spaak J, Merlocco AC, Soleas GJ, Tomlinson G, Morris BL, Picton P, Notarius CF, Chan CT, Floras JS. Dose-related effects of red wine and alcohol on hemodynamics, sympathetic nerve activity, and arterial diameter. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H605–H612, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spanier G, Xu H, Xia N, Tobias S, Deng S, Wojnowski L, Forstermann U, Li H. Resveratrol reduces endothelial oxidative stress by modulating the gene expression of superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPx1) and NADPH oxidase subunit (Nox4). J Physiol Pharmacol 60, Suppl 4:111–116, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Subramanian M, Balasubramanian P, Garver H, Northcott C, Zhao H, Haywood JR, Fink GD, MohanKumar SM, MohanKumar PS. Chronic estradiol-17β exposure increases superoxide production in the rostral ventrolateral medulla and causes hypertension: reversal by resveratrol. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 300: R1560–R1666, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Szewczuk LM, Forti L, Stivala LA, Penning TM. Resveratrol is a peroxidase-mediated inactivator of COX-1 but not COX-2; a mechanistic approach to the design of COX-1 selective agents. J Biol Chem 279: 22727–22737, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tanahashi M, Hara S, Yoshida M, Suzuki-Kusaba M, Hisa H, Satoh S. Effects of rolipram and cilostamide on renal functions and cyclic AMP release in anesthetized dogs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 289: 1533–158, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thandapilly SJ, LeMaistre JL, Louis XL, Anderson CM, Netticadan T, Anderson HD. Vascular and cardiac effects of grape powder in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Am J Hypertens 25: 1070–1076, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tousoulis D, Kampoli AM, Tentolouris C, Papageorgiou N, Stefanadis C. The role of nitric oxide on endothelial function. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 10: 4–18, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walle T. Bioavailability of resveratrol. Ann NY Acad Sci 1215: 9–15, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wallerath T, Deckert G, Ternes T, Anderson H, Li H, Witte K, Förstermann U. Resveratrol, a polyphenolic phytoalexin present in red wine, enhances expression and activity of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circulation 106: 1652–1658, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wallerath T, Poleo D, Li H, Förstermann U. Red wine increases the expression of human endothelial nitric oxide synthase: a mechanism that may contribute to its beneficial cardiovascular effects. J Am Coll Cardiol 4: 471–478, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu CC, Wu CI, Wang WY, Wu YC. Low concentrations of resveratrol potentiate the antiplatelet effect of prostaglandins. Planta Med 73: 439–443, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zykova TA, Zhu F, Zhai X, Ma WY, Ermakova SP, Lee KW, Bode AM, Dong Z. Resveratrol directly targets COX-2 to inhibit carcinogenesis. Mol Carcinog 47: 797–805, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]