Introduction

Breast cancer usually originates in milk ducts (ductal carcinoma) or milk-supplying lobules (lobular carcinoma). It can be an aggressive cancer because these structures are proximate to lymph nodes and other vital organs.1 Treatment delay can result in disease progression, potential worsening of prognosis and even death.2 Clinically, treatment can involve numerous specialists and tasks associated with surgery, chemotherapy, radiation and hormonal treatment.3 On the patient level, cancer diagnosis affects logistical issues, decision-making, subjective feelings, instrumental and social support and health care system interaction.4 These especially affect women unfamiliar with the health care system or facing barriers such as logistic problems, psychosocial issues, inadequate health care insurance or other aspects of low socioeconomic status and socioeconomic marginalization.5 The interaction of clinical and patient-level challenges following a breast cancer diagnosis can be a significant source of health care disparities.4 The National Cancer Institute (NCI) defines "cancer health disparities" as adverse differences in cancer incidence (new cases), cancer prevalence (all existing cases), cancer death (mortality), cancer survivorship, and burden of cancer or related health conditions that exist among specific population groups in the United States.6

Patient navigation (PN) has evolved as a promising strategy to overcome these disparities. Individuals trained to assist people to overcome barriers were introduced as key components of Freeman’s unique navigation model, which increased access and efficacy of care in Harlem, New York.7 Financial barriers (including uninsured and under insured), communication barriers (inadequate understanding), medical system barriers (fragmented medical system, missed appointments, lost results), psychological barriers (fear, distrust) and other barriers (e.g. transportation, child care) have been negotiated by PN in a variety of venues.8–11 However, barriers are particularly difficult to overcome when linguistic and other cultural aspects complicate them further. Inattention to the root causes of cancer care disparities results in the barriers experienced by some groups. Failure to address specific cultural features that create or exacerbate barriers can lead to less-than optimal navigation results.12–14

One important group affected by this situation is women of Hispanic/Latino (henceforth referred to as “Latino” or the feminine “Latina”) heritage. These represent a heterogeneous group, defined by the United States Office for Management and Budget as “A person of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, South or Central American, or other Spanish culture or origin, regardless of race”.15 In this study, women identified themselves as Latino of Mexican-American, Central American, Cuban, Puerto Rican, South American, Caribbean, or Other Hispanic/Latino origin. For this group, treatment delay and lower survival rates continue to constitute a significant health disparity.16 According Cancer is the leading cause of death overall in Latinos, and breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death among Latinas.17 Approximately 2,200 Latinas died from breast cancer in 2009,18 and 2,400 more are expected to have died in 2012.17 Breast cancer mortality ranks higher in Latinas than Non-Hispanic White (NHW) women probably because it is diagnosed and treated later in Latinas than NLW16 when stage is more advanced, tumors are larger and the complexities of treating more frequent negative hormone-receptor status breast cancer are realized.17, 19, 20 Differences are associated with socioeconomic and cultural factors marginalizing Latinas and other minorities from cancer care, as well as biological factors unique to Latinos. Cultural barriers have been often ignored, as navigation services sometimes neglect to address the implications and effects of language barriers and social norms such as respeto (“respect”), familismo (family-centeredness), marianismo (high value of being dedicated wives and mothers), simpatia (formal friendliness or kindness), fatalismo (fatalism), dignidad (dignity) and others.21 An obvious consequence is reduced efficacy of navigation services and more importantly, suboptimal use of cancer care services.20, 22 These are significant, because Latinos are currently the largest U.S. minority and by 2030 will constitute an estimated one-third of the nation’s population.23, 24 Fueled by psychosocial, linguistic and other sociocultural barriers, disparities translate into increasingly larger gaps with respect to access to care, quality of life, and ultimately survival rates along the entire cancer care continuum.5, 25, 26

To address these disparities, study leaders in San Antonio and five other regional partners of the federally-funded Redes En Acción: The National Latino Cancer Research Network developed a culturally-tailored PN intervention model for Latinas with breast cancer.27 Informed by Harold Freeman’s successful navigation model,7 our prior work with Latina breast cancer survivors,27–30 and critical pieces of several health-related models (e.g. Social Cognitive Theory,31 Health Belief Model,32 Theory of Reasoned Action33), trained, bilingual community health workers assisted Latinas in utilizing cancer care services in cities with significant Latino populations (San Francisco, San Diego, New York, Miami, Houston and San Antonio, Texas).28 We applied our model to women with an abnormal mammogram to determine its effectiveness in reducing time from abnormal breast exam findings to definitive diagnosis,29 and here evaluate its effect on time from definitive diagnosis to initiation of treatment (T1–T2) overall and within 30 days (T1–T2/30) and 60 days (T1–T2/60) and how PN activities influence those times. We hypothesize that navigation increases rates of T1–T2/30 and T1–T2/60 and reduces T1–T2 compared to non-navigated Latinas receiving standard care. We also hypothesize that patient navigator activities mediate T1–T2/30 and T1–T2/60.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

We used a quasi-experimental design to recruit 480 self-identified Latinas (n=251 navigated and 229 non-navigated controls) at community-based health clinics in the six study sites from January 2008-January 2011. Written consent was obtained for all subjects. Navigators recruited eligible women for the navigation intervention by telephone and in person generally within one week of the documentation of the abnormal screening test result. Consent from control subjects was obtained through the primary care delivery site standard consent process. Women were enrolled into the study backward-sequentially (for controls) or if navigated, forward-sequentially as identified. Eligibility criteria included Latina females aged 18 years or older with an abnormal breast screening mammogram result of Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) -3, -4, or -5, and excluded if any treated cancer in the past five years and/or had experienced past navigation. Of the original group of 480 Latinas recruited, we previously analyzed 425 for whom we had complete data through diagnosis and reported those results.29 Here we assess a subset of those diagnosed with breast cancer (n=109) from July 2008-January 2011 (42 navigated, 67 controls). We focus on proportions of women who began treatment within 30 and 60 days of diagnosis, and the association of specific navigator activities related to treatment initiation time.

Navigation

Patient navigation was based on our developed culturally-tailored PN) intervention model for Latinas with breast cancer described above.27 Six bilingual Latina navigators were employed (1 per study site community). They were women 25–47 years old with at least a high school diploma or college degree, and trained to coordinate care for those referred for diagnostic evaluation and treatment if needed. All navigators were trained either in San Antonio or at their own sites according to guidelines developed previously by the Institute for Health Promotion Research.27 Navigators emphasized adherence to diagnostic and treatment plans and assisted patients in achieving treatment goals through direct actions and effective communication (including language translation services), education and empathy. Common scripts were not used by navigators. Rather, navigators contacted patients weekly or were contacted by patients at need determined by patients. Consequently, navigators responded to express needs by providing culturally sensitive support and guidance and served as an advocate and liaison in encouraging patient understanding of their disease and treatment and overcoming potential barriers such as lack of transportation and/or child care, imprecise communication with health care providers, health insurance issues, and fear of cancer and/or treatment of it.34 Finally, navigators maintained regular logs of encounters with patients. Encounters were either navigator-initiated (at least once a month or more often as appointments and/or situations required), or patient-initiated via telephone contact with the navigator. For each encounter, navigators recorded any of 10 pre-identified barriers reported by patients at that encounter, actions subsequently taken by the navigator to assist the patient in overcoming each specific barrier, and the time (minutes) required for each. A summary field was also coded indicating whether or not that particular barrier was resolved.

Data

Data were collected beginning in January 2008 (at initial abnormal mammogram) via a combination of interviews and medical chart abstraction by patient navigators. Interviews were conducted for navigated women at baseline and completion of diagnosis (if non-cancer) or completion of treatment (up to 365 days following initial abnormal finding) at the last visit to a clinic by participants in either Spanish or English (but not both languages) as preferred by that participant. Data was collected for control patients only via medical chart abstraction. Project coordinators at each site reviewed all records for completeness, accuracy, and internal consistency. Data were then entered into a secure, password-protected database.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes were dichotomous measures of time from diagnosis to treatment initiation within 30 or 60 days of diagnosis, referred to as “timely” treatment within the period specified. Date of diagnosis was determined as the first (earliest) date of definitive tissue diagnosis (biopsy with pathology report) or clinical evaluation resulting in no further diagnostic evaluation.35 The date of treatment initiation was determined as the first (earliest) date of any type of treatment including surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, or hormone therapy. Both the 30 and 60-day timely treatment cutoffs were calculated because each has demonstrated validity in several studies. A recent analysis of compliance with the treatment initiation benchmark showed a median time to treatment in Hispanic women of 12–15 days.36 A separate study using data from the United Kingdom, European Union, and the U.S. National Initiative for Cancer Care Quality (NICCQ)37 found that timeliness recommendations from breast cancer diagnosis to surgery was a maximum of ~37 working days.3 A timeliness audit by the same authors of 2004–2006 found a median time of 11 business days from diagnosis to date of surgery, which met the requirements of the Metropolitan Chicago Breast Cancer Task Force benchmark of 30 days from diagnosis to timely treatment.38

Other studies have shown that a 60-day cutoff for timely treatment is appropriate. The National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program service delivery goal is 60 days from diagnosis to treatment.39 Additionally, McLaughlin and colleagues showed that waiting ≥ 60 days to initiate treatment was associated with a significant 66% and 85% increased risk of overall and breast cancer-related death.2 In light of this evidence, we used both 30 and 60 days as criteria for timely treatment of breast cancer.

Independent Measures

Independent variables were taken from baseline interviews and chart abstraction. They included country of origin, primary language spoken and marital, employment, and insurance status. “Country of origin” was derived from participant birthplace, encompassing the OMB definition of Latino40 and collapsed as United States, Mexico, or Other. Age was calculated from birth month and year at enrollment and categorized as <50 or ≥50 years. Clinical variables included initial treatment type, stage of cancer, sentinel lymph node status, # of negative receptor sites, and presence of comorbidity. Navigator encounters were examined to determine whether navigator-coded actions, patient-reported barriers, or time to take specific actions had an impact on time to treatment. In this study we focused on navigator action types recorded during encounters occurring from the date of cancer diagnosis until initial treatment. These included referral, accompaniment, transportation, phone support, records assistance, education, appointment scheduling, family support, translation services, system intervention, and total types of actions taken. Neither measures of the number of times a particular action was taken by a navigator (“navigation intensity”), nor time required by specific activities were evaluated in this study due to the relatively small sample size considered and complexity of analysis required.

Analysis

Analyses were conducted using SPSS version 20 (2012, Chicago, Ill). Descriptive statistics of group characteristics were calculated using Chi-Square tests. We compared rates of timely treatment (within 30 or 60 days) between groups using Chi-Square analysis. Overall time-to-treatment was compared between navigated and control participants using the Kaplan-Meier method. Finally, we determined the frequency that navigators conducted certain actions and evaluated timely treatment within 30 days in the navigated group by comparing proportions of women with and without timely treatment if each navigator action was taken, again using Chi-Square analysis for each. (We did not perform this step for timely treatment within 60 days because all but one navigated woman achieved treatment within this benchmark period). A 2-sided p <0.05 indicated statistical significance in all comparisons.

RESULTS

Descriptive characteristics of participants

Of the original cohort of 480 patients with initial abnormal mammograms, follow-up data were available for 425 (88.5%).29 All participants were initially seen by a primary care clinician in community-based clinics reflecting general uninsured or publically insured status. Of these, 109 were diagnosed with cancer. Their demographic and clinical characteristics are displayed for the navigated and control groups in Table 1. There were no significant differences between groups with respect to age, country of origin, primary language, marital status, or employment or insurance status. Overall, characteristics of this population suggest older Latinas of other than U.S. or Mexican country of origin who were unemployed and underinsured. In terms of clinical characteristics there were no differences between groups. Of note, 38.7% and 26.4% of cancer diagnoses were at stage 2 and 3–4 progression respectively, and 29.3% of examined receptor sites revealed 2 or more negative results. Rates of missing information did not vary between groups.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Navigated and Control Womena

| Measure | Control N=67 | Navigated N=42 | P-value | Total N=109 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | |||||||

| Age (categories) | 1.000 | ||||||

| <50 years | 28 | 41.8 | 18 | 42.9 | 46 | 42.2 | |

| 51+ years | 39 | 58.2 | 24 | 57.1 | 63 | 57.8 | |

| Country of Originb | 0.519 | ||||||

| US | 4 | 16.0 | 9 | 25.0 | 13 | 21.3 | |

| Mexico | 6 | 24.0 | 11 | 30.6 | 17 | 27.9 | |

| Other | 15 | 60.0 | 16 | 44.4 | 31 | 50.8 | |

| Primary Language | 0.507 | ||||||

| English | 22 | 36.7 | 15 | 45.5 | 37 | 39.8 | |

| Spanish | 38 | 63.3 | 18 | 54.5 | 56 | 60.2 | |

| Marital | 0.841 | ||||||

| Married/Living as married | 27 | 41.5 | 17 | 43.6 | 44 | 42.3 | |

| Unmarried | 38 | 58.5 | 22 | 56.4 | 60 | 57.7 | |

| Employment | 1.000 | ||||||

| Yes | 14 | 37.8 | 13 | 36.1 | 27 | 37.0 | |

| No | 23 | 62.2 | 23 | 63.9 | 46 | 63.0 | |

| Insurance | 0.979 | ||||||

| Medicare | 5 | 7.5 | 3 | 7.3 | 8 | 7.4 | |

| Private insurance | 13 | 19.4 | 7 | 17.1 | 20 | 18.5 | |

| Other local government | 22 | 32.8 | 13 | 31.7 | 35 | 32.4 | |

| None | 27 | 40.3 | 18 | 43.9 | 45 | 41.7 | |

| Clinical | |||||||

| Initial Treatment | 0.702 | ||||||

| Lumpectomy | 26 | 40.1 | 16 | 38.1 | 42 | 39.3 | |

| Mastectomy | 29 | 44.5 | 18 | 42.9 | 47 | 43.9 | |

| Chemotherapy | 10 | 15.4 | 8 | 19.0 | 18 | 16.8 | |

| Stage of Cancer | 0.614 | ||||||

| 0–1 | 22 | 34.4 | 15 | 35.7 | 37 | 34.9 | |

| 2 | 23 | 35.9 | 18 | 42.9 | 41 | 38.7 | |

| 3–4 | 19 | 29.7 | 9 | 21.4 | 28 | 26.4 | |

| Sentinel Lymph Node Positive | 0.282 | ||||||

| Yes | 6 | 12.8 | 5 | 25.0 | 11 | 16.4 | |

| No | 41 | 87.2 | 15 | 75.0 | 56 | 83.6 | |

| #Negative Receptor Sites | 0.241 | ||||||

| 0–1 | 43 | 75.4 | 22 | 62.9 | 65 | 70.7 | |

| 2–3 | 14 | 24.6 | 13 | 37.1 | 27 | 29.3 | |

| Charlson Comorbidityc | 0.768 | ||||||

| No | 55 | 87.3 | 32 | 84.2 | 87 | 86.1 | |

| Yes | 8 | 12.7 | 6 | 15.8 | 14 | 13.9 | |

Sample sizes vary due to missing data

All women self-identified as of Latino origin, consistent with United States Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Directive 15 guidelines. Women of Hispanic/Latino, Mexican-American, Central American, Puerto Rican, South American, Caribbean, or Other origin were included in this study, regardless of reported birthplace. Above, “Other” refers to Latino participants who reported origin as one of these places exclusive of the United States or Mexico.

Any comorbidity on chart or patient report

Percentage and time to treatment initiation

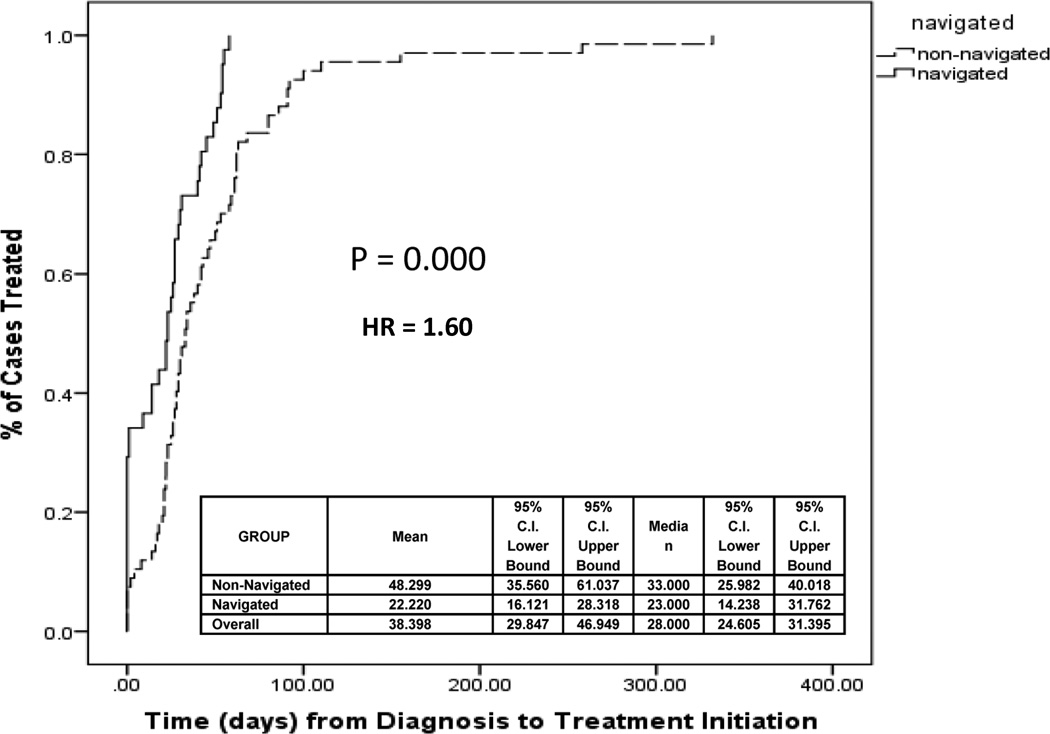

Table 2 shows that, compared with control patients, a higher percentage of navigated subjects initiated treatment within 30 days (66.7% versus 56.7%, p=0.045) and 60 days (97.8% versus 78.4%, p=0.021) following their cancer diagnosis. Kaplan-Meier curves presented in Figure 1 suggest that, compared with controls, women in the navigated group experienced shorter time to treatment initiation overall (HR=1.60, p=0.000). In concrete terms, this reflects time from cancer diagnosis to first treatment was lower in the navigated group (mean 22.22, median 23.00 days) than controls (mean 48.30, median 33.00 days). These results were independent of cancer stage at diagnosis and numerous characteristics of cancer clinics and individual participants. We also controlled for time from initial abnormal mammogram until diagnosis for cancer patients per our previous study.29 It did not affect time from diagnosis until treatment initiation.

Table 2.

Proportion of Participants with Initial Treatment within 30 and 60 days of Diagnosis*

| 30 Days | 60 Days | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | treated | % | P | treated | % | P |

| Navigated n = 42 | 29 | 69.0 | 0.029 | 41 | 97.6 | 0.001 |

| Controls n = 67 | 31 | 46.3 | 49 | 73.1 | ||

Based on intent-to-treat. A lost navigated case (sought a second opinion) is considered untreated within the time frame specified.

Figure 1.

Time to Treatment of Navigated and Non-Navigated Patients

Navigation activities

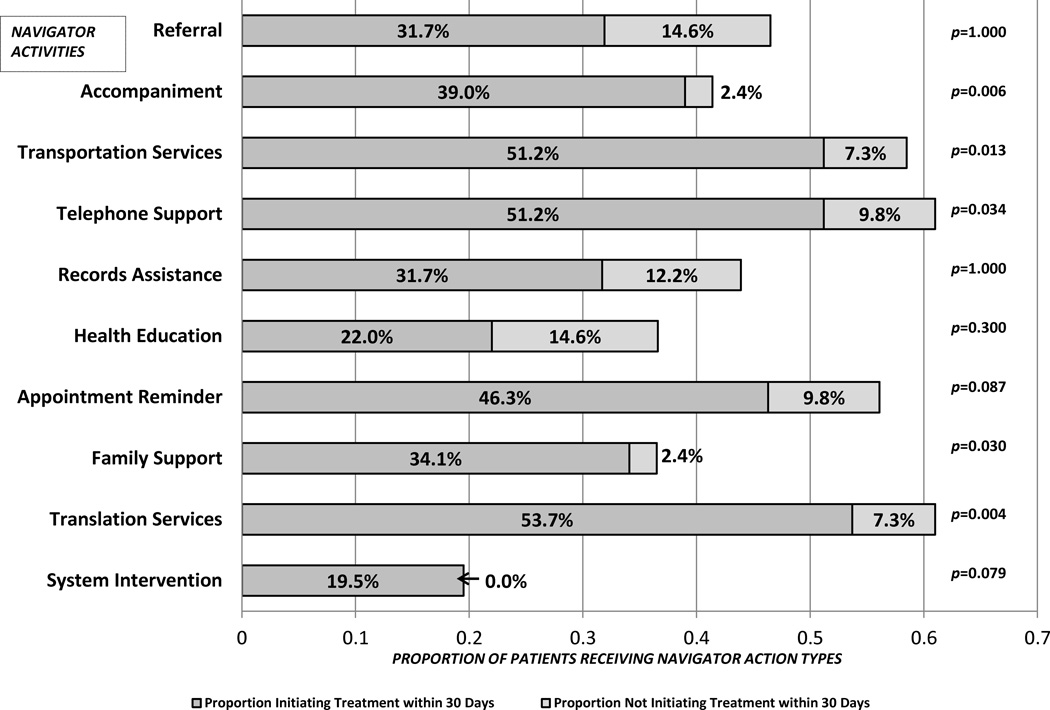

Figure 2 shows 11 types of navigator activities conducted from diagnosis to treatment initiation. The height of vertical bars indicates the proportion of navigated patients for whom each activity was conducted. Above each bar we show the p-value of the association of each activity with timely treatment within 30 days of diagnosis. The most frequently-performed navigator activities were Spanish-English translation services (61.8% of patients), followed by telephone support (59.8%) and transportation services (56.1%). Faster treatment times were achieved through at least six activities related to oncology appointments: accompaniment (p=0.002), transportation arrangements (p=0.020), patient telephone support (generally emotional support, p=0.041), patient-family telephone support (p=0.027), Spanish-English language translation services (p=0.001), and assistance with insurance paperwork related issues (p=0.023).

Figure 2.

Navigator Activities and Association with Treatment Initiation within 30 Days of Diagnosis

DISCUSSION

Study limitations

An outstanding limitation of this study was the relatively small sample size addressed (n=109). This is however, simply the number of patients of a larger study who were unfortunate to be diagnosed with cancer; the number could not be made larger. This deficiency was overcome somewhat by the national representation of Latinas who comprised it. Our sample was comprised of Latinas from all regions of the United States, and likely constitutes a good representation of Latinas in general. Another potential limitation involves the potential threat to validity posed by how data were collected: patient characteristics were defined by interview for the navigated cohort but by medical record review for the control cohort. Therefore a mode effect could occur whereby different data sources, rather than differences in initiation of treatment is responsible for the reported outcomes. We consider this threat minimal however, because all information for navigated and non-navigated women was entered into the medical by health care providers (in some cases, the same blinded person) according to identical protocols. Also, whether or not controls received some form of navigation other than program-delivered was unknown, possibly yielding an underestimate of group differences. Finally, at the end of the first phase of our study (examining time from abnormal mammogram to definitive diagnosis), we conducted a power analysis in which we noted that approximately 120 patients with cancer would be required to achieve power of 0.73 to demonstrate a statistically significant difference (p<0.05) if we improved the number of patients diagnosed within a given time period by 20%. In point of fact, we exceeded this goal.

Delayed treatment = Lower survival

Results from this study contribute in several ways to advancing knowledge about the efficacy of PN and the activities of navigators in assisting patients. Studies have shown that delaying treatment for breast cancer can result in significantly decreased survival rates.2 This tends to occur more often among women of lower socioeconomic status and racial/ethnic minorities.19, 26 These disparities manifest themselves in lower survival rates of disadvantaged women, and have been shown to be a consequence of a cluster of circumstances from minority status and marginalization, lack of medical insurance, inability to access and adequately utilize medical resources, unavailability of those resources in some locales, late diagnoses and more severe disease, and similar delays in treatment ultimately leading to higher rates of death.41 The disparities not only appear to be of sociodemographic origin, but linked sociocultural origin as well. This implies a complex problem from the standpoint of intervention; namely, how to apply possible solutions to a multifaceted problem having its roots in the fabric of society?22

Positive effect of PN on breast cancer treatment initiation

In our Latina sample, time to treatment was significantly decreased by PN. However, our sample’s mean time of 25 days, although within our self-imposed 30-day limit, was still lower than the treatment interval of ≤ 2 weeks observed among institutions participating in the NBCCEDP.39 The National Consortium of Breast Centers (NCBC) created a set of quality indicators, the National Quality Measures for Breast Centers program (NQMBC®), in order to improve quality of care. Seven time intervals occurring between evaluation and treatment are included.3 PN may provide an effective intervention to ameliorate disparities in time to treatment. The expected impact of PN on some aspects of the cancer care continuum is high, but demonstrating efficacy has been difficult. Evidence is summarized in a recent review noting the rapid expansion of PN while underscoring study limitations including lack of randomization, absence of control groups, small sample sizes and inability to compare endpoints.42 While the benefits of PN to the barriers faced by low-income underserved minority groups in dealing with cancer remains unclear, there is some evidence that PN works when applied correctly and in a timely fashion to specific clinical challenges.29 An important question to be answered is why this particular intervention was successful.

The role of ethnicity in PN

Some studies of PN interventions have shown success in reducing time from initial abnormal mammogram to confirmed diagnosis.8, 43 Similar reductions of time from diagnosis to treatment have not been reported, however, nor has it been demonstrated how navigation achieves its goal. Our results regarding PN among Latinas suggest how this might occur. As reported separately by Battaglia,8 Raich43 and colleagues, PN reduced time from abnormal mammogram to definitive diagnosis among groups consisting largely of socioeconomically disadvantaged people whose primary problem was time (immediacy) and cost. Patient navigators were largely successful at countering those problems, and patients were diagnosed faster if navigated. This was not so in our own study of Latinas, who though faced with the same problems, were handicapped further by sociocultural and linguistic barriers that required not only navigator investment of time to gain the trust of patients,28 but ability to assist patients to overcome barriers deriving from cultural norms – often expressed as the provision of support of one form or another (e.g. accompaniment to appointments to help overcome patient fears and telephone calls to family members to gain their support for patients’ adhering to health care system timetables). Another significant activity – possibly the most significant activity – was the ability of navigators to provide language translation services (following a suitable time to engage the trust of patients) to enable patients to proceed in a timely and informed fashion through cancer treatment initiation.

CONCLUSION

To our knowledge this is the first study of its kind. We report successful application of PN to increase the percentage of Latinas initiating breast cancer treatment within 30 and 60 days of diagnosis. Additionally, we show how this was achieved through navigator provision services such as accompaniment to appointments, transportation arrangements, patient telephone support, patient-family telephone support, Spanish-English language translation, and assistance with insurance paperwork.

References

- 1.Sariego J. Breast cancer in the young patient. American Surgeon. 2010;76(12):1397–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McLaughlin JM, Anderson RT, Ferketich AK, Seiber EE, Balkrishnan R, Paskett ED. Effect on survival of longer intervals between confirmed diagnosis and treatment initiation among low-income women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(36):4493–500. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.39.7695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Landercasper J, Linebarger JH, Ellis RL, et al. A quality review of the timeliness of breast cancer diagnosis and treatment in an integrated breast center. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210(4):449–455. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carroll JK, Humiston SG, Meldrum SC, et al. Patients'xperiences with navigation for cancer care. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;80(2):241–247. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ward E, Halpern M, Schrag N, et al. Association of insurance with cancer care utilization and outcomes. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58(1):9–31. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Cancer Institute. Fact Sheet: Cancer Health Disparities. [accessed September 5, 2013];2013 Available from URL: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/disparities/cancer-health-disparities.

- 7.Freeman HP. A model patient navigator program. Oncology Issues. 2004;19:44–47. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Battaglia TA, Bak SM, Heeren T, et al. Boston Patient Navigation Research Program: the impact of navigation on time to diagnostic resolution after abnormal cancer screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(10):1645–1654. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chatman MC, Green RD. Addressing the unique psychosocial barriers to breast cancer treatment experienced by African-American women through integrative navigation. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc. 2011;22(2):20–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haideri NA, Moormeier JA. Impact of patient navigation from diagnosis to treatment in an urban safety net breast cancer population. J Cancer. 2011;2:467–473. doi: 10.7150/jca.2.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Markossian TW, Darnell JS, Calhoun EA. Follow-up and timeliness after an abnormal cancer screening among underserved, urban women in a patient navigation program. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(10):1691–1700. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall CP, Hall JD, Pfriemer JT, Wimberley PD, Jones CH. Effects of a culturally sensitive education program on the breast cancer knowledge and beliefs of Hispanic women. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34(6):1195–1202. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.1195-1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jimenez EA, Xie Y, Goldsteen K, Chalas E. Promoting knowledge of cancer prevention and screening in an underserved Hispanic women population: a culturally sensitive education program. Health Promot Pract. 2011;12(5):689–695. doi: 10.1177/1524839910364370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ulrich A, Thompson B, Livaudais JC, Espinoza N, Cordova A, Coronado GD. Issues in biomedical research: what do Hispanics think? Am J Health Behav. 2013;37(1):80–85. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.37.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katzen S. United States Office for Management and Budget Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. Washington, DC: United States Printing Office; 1997. Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ashing-Giwa KT, Padilla G, Tejero J, et al. Understanding the breast cancer experience of women: a qualitative study of African American, Asian American, Latina and Caucasian cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2004;13(6):408–428. doi: 10.1002/pon.750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures for Hispancis/Latinos 2012–2014. Atlanta, Ga: American Cancer Society; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures for Hispanics/Latinos. 2009–2011. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Livaudais JC, Hershman DL, Habel L, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in initiation of adjuvant hormonal therapy among women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;131(2):607–617. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1762-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller BA, Hankey BF, Thomas TL. Impact of sociodemographic factors, hormone receptor status, and tumor grade on ethnic differences in tumor stage and size for breast cancer in US women. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;155(6):534–545. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.6.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davila YR, Reifsnider E, Pecina I. Familismo: influence on Hispanic health behaviors. Appl Nurs Res. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Viswanath K, Ackerson LK. Race, ethnicity, language, social class, and health communication inequalities: a nationally-representative cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):e14550. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howe H, Carozza S, O’alley C, et al. Cancer Incidence in US Hispanic/Latinos, 1995–2000. Springfield (IL): North American Association of Central Cancer Registries; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 24.United States Bureau of the Census. United States Census Bureau. Current Population Survey. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freedman RA, He Y, Winer EP, Keating NL. Trends in racial and age disparities in definitive local therapy of early-stage breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(5):713–719. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.9234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erwin DO, Trevino M, Saad-Harfouche FG, Rodriguez EM, Gage E, Jandorf L. Contextualizing diversity and culture within cancer control interventions for Latinas: changing interventions, not cultures. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(4):693–701. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Redes En Acción: The National Latino Cancer Research Network. A Patient Navigation Manual for Latino Audiences: The Redes En Acción Experience. [accessed Sept 27, 2012]; Available from URL: http://www.redesenaccion.org/PatientNavigatorManual. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braun KL, Kagawa-Singer M, Holden AE, et al. Cancer Patient Navigator Tasks across the Cancer Care Continuum. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(1):398–413. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramirez AG, Perez-Stable EJ, Penedo FJ, et al. Navigating Latinas with breast screen abnormalities to diagnosis: The Six Cities Study. Cancer. 2012 doi: 10.1002/cncr.27912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramirez AG, McAlister A, Gallion KJ, et al. Community level cancer control in a Texas barrio: Part I--Theoretical basis, implementation, and process evaluation. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1995;(18):117–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education & Behavior. 2004;31(2):143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenstock IM. The health belief model and preventive health behavior. Health Education Monographs. 1974;2:354–386. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fishbein M. A theory of reasoned action: some applications and implications. Nebr Symp Motiv. 1980;27:65–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wells KJ, Battaglia TA, Dudley DJ, et al. Patient Navigation: State of the Art or Is it Science? Cancer. 2008;113(8):1999–2010. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freund KM, Battaglia TA, Calhoun E, et al. National Cancer Institute Patient Navigation Research Program: methods, protocol, and measures. Cancer. 2008;113(12):3391–3399. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malin JL, Ko C, Ayanian JZ, et al. Understanding cancer patients' experience and outcomes: development and pilot study of the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance patient survey. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14(8):837–848. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0902-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malin JL, Schneider EC, Epstein AM, Adams J, Emanuel EJ, Kahn KL. Results of the National Initiative for Cancer Care Quality: how can we improve the quality of cancer care in the United States? J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(4):626–634. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Metropolitan Chicago Breast Cancer Task Force. Task Force Projects. Explanation of Measures: Treatment. [accessed Sept. 26, 2012]; Available from URL: http://www.chicagobreastcancer.org/site/epage/101109_904.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Caplan LS, May DS, Richardson LC. Time to diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer: results from the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program, 1991–1995. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(1):130–134. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.1.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.United States Office for Management and Budget. United States Office for Management and Budget Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. Directive No. 15. Washington, DC: United States Printing Office; 1977. DIRECTIVE NO. 15 RACE AND ETHNIC STANDARDS FOR FEDERAL STATISTICS AND ADMINISTRATIVE REPORTING. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peres J. Mammography Screening: After the Storm, Calls for More Personalized Approaches. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2010;102(1):9–11. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paskett ED, Harrop JP, Wells KJ. Patient Navigation: An Update on the State of the Science. Ca-a Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2011;61(4):237–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raich PC, Whitley EM, Thorland W, Valverde P, Fairclough D. Patient navigation improves cancer diagnostic resolution: an individually randomized clinical trial in an underserved population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(10):1629–1638. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]