Abstract

AIM: To investigate the usefulness of branched-chain amino acids (BCAA) before transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) or radiofrequency ablation (RFA).

METHODS: We investigated the usefulness of pre-intervention with BCAAs by comparing patients treated with BCAAs at 12.45 g/d orally for at least 2 wk before TACE or RFA and those not receiving such pretreatment. A total of 270 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma complicated by cirrhosis were included in the study. Mean changes from baseline (Δ) in serum albumin (Alb), C-reactive protein (CRP), and transaminase levels, as well as peak body temperature were also determined and compared at days 2, 5, and 10 after the start of TACE or RFA.

RESULTS: In patients who underwent TACE or RFA, BCAA pre-intervention significantly suppressed the development of post- intervention hypoalbuminemia and reduced inflammatory reactions during the subsequent clinical course. After TACE, the ΔAlb peaked on day 2, remained constantly lower in BCAA-treated patients, compared to the control group, and was -0.13 ± 0.42 g/dL in BCAA-treated patients and -0.33 ± 0.51 g/dL in untreated patients on day 10. The ΔCRP was also significantly lower in BCAA-treated patients on days 2, 5 and 10 after TACE. Like the trends noted after TACE, a similar tendency was noted as to the ΔAlb and ΔCRP after RFA. The changes in serum Alb level were inversely correlated with CRP changes; therefore, a possible involvement of the anti-inflammatory effect of BCAAs was inferred as a factor contributory to the suppression of decrease in serum Alb level.

CONCLUSION: Pre-intervention with BCAAs may hasten the recovery of serum Alb level and mitigate post-operative complications in patients undergoing TACE or RFA.

Keywords: Branched-chain amino acids, Cirrhosis, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Transarterial chemoembolization, Radiofrequency ablation, Hypoalbuminemia

Core tip: This study investigated whether the short-term effect of branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) for transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) or radiofrequency ablation (RFA), focusing on BCAA treatment prior to therapeutic intervention, suppresses the decrease in serum albumin (Alb) level associated with TACE or RFA and reduces postoperative complications. We thought that C-reactive protein (CRP) elevation was suppressed in BCAA-treated patients, that the severity of fever was milder as a result of BCAA treatment, and that the serum Alb level decreased to a lesser extent in patients with milder changes in CRP level.

INTRODUCTION

Decrease in plasma albumin (Alb) level occurs early after therapeutic intervention such as transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) for treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and the underlying mechanism of this condition includes the extravasation of Alb into the embolized or ablated hepatic region and the involvement of inflammatory cytokine[1]. HCC arises in association with cirrhosis in most patients, readily produces hypoalbuminemia, edema, ascites, and impairs the patient’s quality of life, with a poor vital prognosis[2,3]. Measures to cope with hypoalbuminemia are needed in that therapeutic intervention options as well as the prognosis in HCC patients are dependent on this condition[4-7].

When administered to cirrhosis patients presenting with hypoalbuminemia, the branched-chain amino acids (BCAA) efficiently increase the Fisher ratio and thus improve hypoalbuminemia[8-13]. Improved event-free survival rate has been reported in patients with liver cirrhosis maintained on long-term continuous BCAA treatment[14,15], and the use of such treatment is recommended in guidelines in various countries[16]. In recent years, a liver-protective effect, e.g., lessening of oxidative stress, of BCAAs has been attracting attention[17-19] and BCAA treatment has been reported to maintain skeletal muscles; these multifunctional pharmacological effects of this preparation have become the focus of increased interest[4].

Hypoalbuminemia is noted often early after TACE or RFA in patients with HCC complicated by cirrhosis[1]. This retrospective study was conducted to determine whether pre-intervention with BCAAs is effective in suppressing such hypoalbuminemia early after the intervention, as well as factors involved in such effect.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total of 270 patients with HCC complicated by cirrhosis who were admitted to Yokkaichi Digestive Disease Center and treated there between April 2004 and April 2012 were included in the study. TACE was performed in 162 patients (of them, 76 and 86 patients were treated with BCAAs and untreated before TACE, respectively) and RFA in 108 patients (of them, 40 and 68 patients were treated with BCAAs and untreated before RFA, respectively). Cirrhosis and HCC were diagnosed based on the findings in various imaging studies and hematological/blood chemical test results, and, where deemed necessary, liver biopsy and/or tumor biopsy findings were also used. Anticancer agents, cisplatin and epirubicin hydrochloride, were used in patients who underwent TACE. In the BCAA-treated group, patients received LIVACT® Granules (Ajinomoto Pharma Co., Ltd., Tokyo) at 12.45 g/d orally (in 3 divided doses daily, after each meal) for at least 2 wk before TACE or RFA, and the oral dosage of the drug remained unchanged throughout the study period. Patients who had not received such treatment constituted the non-BCAA-treated group (control group). Patients who received transfusion of Alb preparation, blood transfusion, and/or newly instituted BCAA treatment and patients who underwent TACE in combination with RFA during the course of study treatment were excluded from the study.

Patients were compared with respect to the following clinical parameters: pre-treatment (baseline) Child-Pugh score [serum Alb level, prothrombin time (PT) expressed as a percentage, total bilirubin (T-Bil), and severity of ascites/encephalopathy], clinical stage of HCC, maximum tumor diameter, C-reactive protein (CRP) level, and tumor markers. Mean changes from baseline (Δ) in serum Alb, CRP, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, as well as peak body temperature were also determined and compared at days 2, 5, and 10 after the start of treatment.

Statistical analysis

Data obtained were expressed as the mean ± SD, and comparisons between the patient groups were performed using χ2 test and t test. Changes in laboratory test parameters and body temperature from baseline (Δ) were analyzed using t test. Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficient was used for testing the correlation between the two groups.

RESULTS

Patient demographic characteristics of the two groups prior to TACE or RFA

Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of patients who underwent TACE in this study. Patients in whom cirrhosis was etiologically not attributable to hepatitis virus were more frequent in the control group. There was a greater percentage of patients with advanced (stage-IVa) HCC in the BCAA-treated group although no significant difference was noted between the two groups in respect of maximum tumor diameter. BCAA-treated patients had a lower hepatic functional reserve, as indicated by a serum Alb level of 3.3 ± 0.4 g/dL, than non-BCAA-treated patients with a serum Alb level of 3.8 ± 0.5 g/dL. PT% and T-Bil were also poorer in BCAA-treated patients; hence the significantly higher Child-Pugh score for these patients. The doses of cisplatin and epirubicin hydrochloride used in combination with TACE did not significantly differ between BCAA-treated and non-BCAA-treated patients. The demographic characteristics of patients receiving RFA in this study are shown in Table 1. Depression of hepatic functional reserve, such as a significantly higher Child-Pugh score, was noted for the BCAA-treated group, as was the case with patients who underwent TACE. There was no significant difference between the BCAA-treated and non-BCAA-treated groups with respect to the cause of cirrhosis, clinical stage of HCC, or maximum tumor diameter.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study groups underwent transarterial chemoembolization and radiofrequency ablation

| Characteristics |

TACE |

RFA |

||||

| Control group | BCAA group | P value | Control group | BCAA group | P value | |

| n = 86 | n = 76 | n = 68 | n = 40 | |||

| Male/female | 57/29 | 46/30 | 0.746 | 47/21 | 13/27 | < 0.001 |

| Age (yr) | 72.2 ± 8.6 | 71.7 ± 7.2 | 0.055 | 71.9 ± 6.5 | 73.0 ± 6.0 | 0.386 |

| Cause of hepatic cirrhosis | 13/49/24 | 9/64/3 | 0.025 | 7/47/14 | 0/34/6 | 0.068 |

| (B/C/non B non C) | ||||||

| Child-Pugh (A/B/C) | 11/1/1974 | 35/36/5 | < 0.001 | 59/9/0 | 23/16/1 | < 0.001 |

| Child-Pugh score | 5.6 ± 0.9 | 6.8 ± 1.4 | < 0.001 | 5.7 ± 0.9 | 6.6 ± 1.1 | 0.001 |

| HCC clinical stage | 21/49/11/5/0 | 13/14/21/27/1 | < 0.001 | 21/40/6/0/1 | 16/16/7/1/0 | 0.276 |

| (I/II/III/IVa/IVb) | ||||||

| Alb (g/dL) | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 3.3 ± 0.4 | < 0.001 | 3.6 ± 0.4 | 3.2 ± 0.4 | < 0.001 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.5 | < 0.001 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.5 | 0.010 |

| Body temperature (°C) | 36.2 ± 0.4 | 36.4 ± 0.5 | 0.006 | 36.3 ± 0.5 | 36.4 ± 0.4 | 0.006 |

| PT | 95% ± 10% | 86% ± 15% | < 0.001 | 94% ± 10% | 87% ± 14% | 0.008 |

| T-Bil (mg/dL) | 0.9 ± 0.5 | 1.3 ± 1.1 | 0.007 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 0.014 |

| AFP (ng/mL) | 392 ± 70 | 1657 ± 434 | 0.009 | 392 ± 70 | 1657 ± 434 | 0.009 |

| PIVKA-II (mAU/mL) | 334 ± 975 | 385 ± 1180 | 0.819 | 334 ± 975 | 385 ± 1180 | 0.819 |

| Max tumor size (mm) | 29 ± 26 | 29 ± 32 | 0.937 | 21 ± 8 | 20 ± 8 | 0.364 |

Data were assessed using student’s t test. HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; Alb: Albumin; CRP: C-reactive protein; PT: Prothrombin time; T-Bil: Total bilirubin; AFP: α-fetoprotein; PIVKA-II: Prothrombin induced by vitamin K absence-II; TACE: Transarterial chemoembolization; RFA: Radiofrequency ablation; BCAA: Branched-chain amino acids.

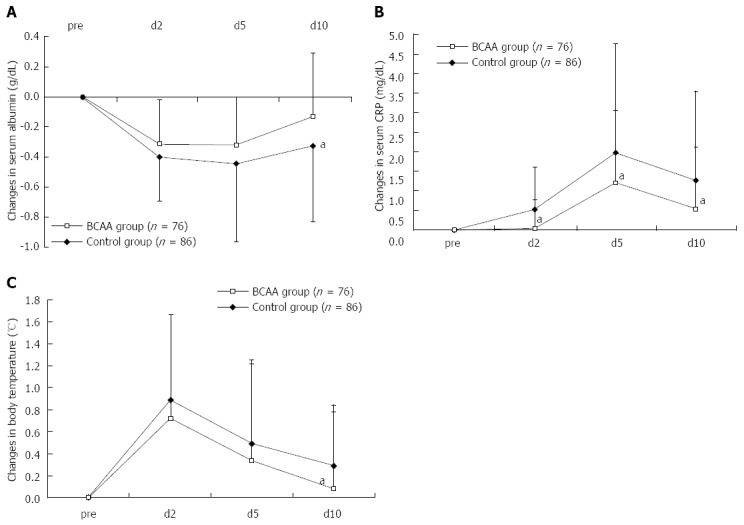

Laboratory values and body temperature over time after TACE

After TACE, the ΔAlb peaked on day 2, remained constantly lower in BCAA-treated patients, compared to the control group, and was -0.13 ± 0.42 g/dL in BCAA-treated patients and -0.33 ± 0.51 g/dL in untreated patients on day 10, thus returning almost to the baseline level in the BCAA-treated group (Figure 1A). The ΔCRP was also significantly lower in BCAA-treated patients on days 2, 5 and 10 after TACE, and peaked on day 5 in both treated and untreated patients (Figure 1B). The maximum body temperature was significantly lower on day 10 post-TACE in the BCAA-treated group (Figure 1C). No significant difference was noted as to ΔAST or ΔALT between BCAA-treated and untreated patients.

Figure 1.

Changes in serum albumin (A), C-reactive protein (B) and body temperature (C) levels in comparison to the baseline level after transarterial chemoembolization. Data were assessed using student’s t test (mean ± SD). aP < 0.05 vs control group. CRP: C-reactive protein; BCAA: Branched-chain amino acids.

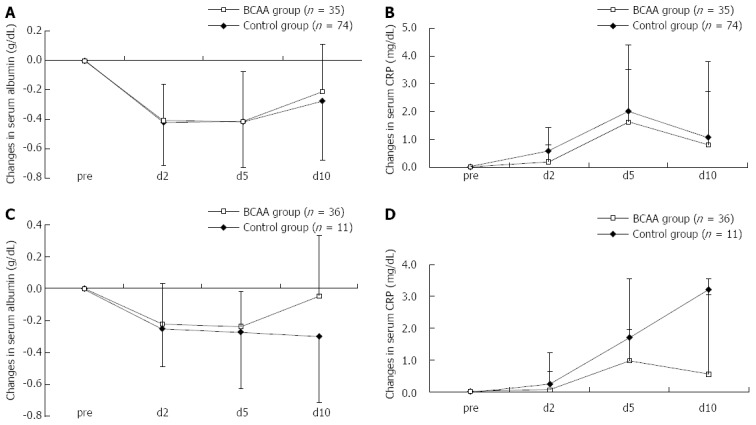

As there was a significant difference in the hepatic functional reserve of BCAA-treated and untreated patients before TACE, we carried out an additional analysis with stratification by Child-Pugh A and B. The analysis revealed a tendency for Child A patients to show a faster recovery in serum Alb level and suppression of CRP elevation (Figure 2A and B). Child B patients exhibited the same trends (Figure 2C and D), indicating that responses to BCAA therapy were independent of pre-TACE hepatic functional reserve.

Figure 2.

Comparison in Child A and B patients with serum albumin and C-reactive protein levels after transarterial chemoembolization. The analysis revealed a tendency for Child A patients to show a faster recovery in serum albumin level (A) and suppression of C-reactive protein (CRP) elevation (B). The analysis revealed a tendency for Child B patients to show a faster recovery in serum albumin level (C) and suppression of CRP elevation (D). Data were assessed using student’s t test (mean ± SD). BCAA: Branched-chain amino acids.

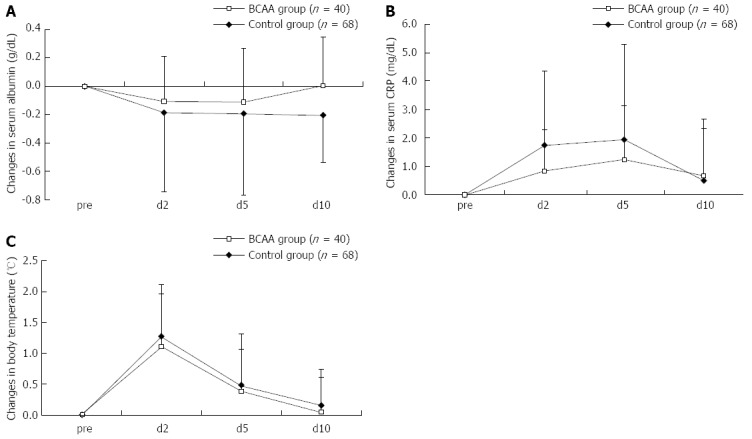

Laboratory values and body temperature over time after RFA

Like the trends noted after TACE, a similar tendency was noted as to the ΔAlb and ΔCRP after RFA; the elevation was suppressed in the BCAA-treated group (Figure 3). The ΔAlb and ΔCRP peaked on days 2 and 5 after RFA, respectively, in these groups, as with the case with these parameters after TACE. As seen in the case of TACE, no significant difference was observed in respect of ΔAST or ΔALT between BCAA-treated and untreated patients.

Figure 3.

Changes in serum albumin (A), C-reactive protein (B) and body temperature (C) levels in comparison to the baseline level after radiofrequency ablation. Data were assessed using student’s t test (mean ± SD). aP < 0.05 vs control group. CRP: C-reactive protein; BCAA: Branched-chain amino acids.

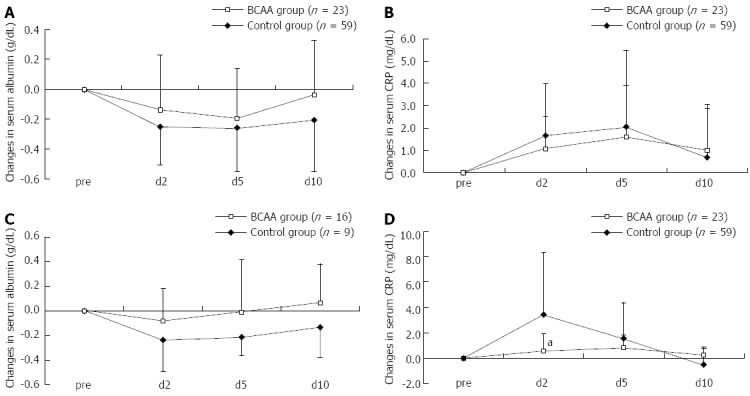

The stratified analysis of data on patients having undergone RFA also revealed a tendency for the serum Alb level to be recovered earlier and the CRP elevation to be suppressed (the suppression was significant especially in Child B on day 2) in both Child A and Child B patients, again indicating that pre-RFA hepatic functional reserve was unlikely to be involved in the patient response to BCAA therapy (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Comparison in Child A and B patients with serum albumin and C-reactive protein levels after radiofrequency ablation. A: A faster recovery of serum albumin level was noted in Child A; B: No difference of C-reactive protein (CRP) was noted in changes in Child A; C: A faster recovery of serum albumin level was noted in Child B; D: A significant difference of CRP was noted in changes in Child B. Data were assessed using student’s t test (mean ± SD). aP < 0.05 vs control group. BCAA: Branched-chain amino acids.

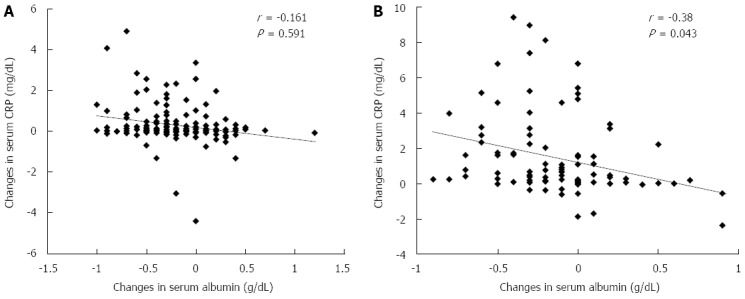

Correlation between ΔAlb and ΔCRP

The correlation between ΔAlb on day 2 post-TACE and ΔCRP on day 10 post-TACE tended to indicate that the greater the serum CRP elevation, the more decreased was the serum Alb level (Figure 5A). Furthermore, there was a significant negative correlation between ΔAlb on day 2 post-RFA and ΔCRP on day 10 post-RFA (Figure 5B). Analyses for correlation at time points of days 2, 5 and 10 revealed no significant correlation.

Figure 5.

Relationship between Δalbumin (day 2) and ΔC-reactive protein (day 10). A: Transarterial chemoembolization; B: Radiofrequency ablation correlation between each variable was tested using Pearson’s correlation coefficient.

DISCUSSION

TACE and RFA are established treatment modalities for hepatocellular carcinoma[20]. However, depression of hepatic functional reserve including hypoalbuminemia may develop after these therapeutic interventions[1]. It was reported that treatment with the BCAAs efficiently increases in Fisher ratio and improves hypoalbuminemia in cirrhosis patients presenting with hypoalbuminemia, and such treatment has become extensively used in daily clinical practice[4,5,14,15]. This effect is thought to result from enhanced mRNA translation for Alb with a consequent promotion of protein synthesis via activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) of hepatocytes that occurs in response to the BCAA supplement[21,22].

The effect of BCAA treatment on post-TACE hypoalbuminemia has already been investigated; Takeshita et al[23] reported that administration of BCAAs at 22:00 after every evening meal inhibited the development of hypoalbuminemia at 2 wk after TACE. Recently, Nishikawa et al[24] also reported that BCAA treatment was useful for long-term maintenance of nutrition after TACE in that the development of hypoalbuminemia was found to be suppressed at 1, 3, and 6 mo post-TACE. However, in the former study, nevertheless, patients had newly started BCAA treatment at the time TACE was performed, and the latter report does not refer to the changes during the early stage after TACE; the two reports differ from the present article in these respects.

On the other hand, based on their findings demonstrating a significant correlation between CRP elevation and decrease in serum Alb level, Koda et al[1] reported that the underlying mechanism of hypoalbuminemia developed following RFA was as follows: inflammatory cytokines liberated due to inflammation at the sites of cauterization act upon liver cells, thereby inducing production of acute inflammatory reactive proteins such as CRP and inhibiting Alb synthesis. They concluded that BCAA treatment was not effective in reversing a short-term decrease in serum Alb level early after RFA because there was no significant difference in serum Alb level decrease at 1 wk post-RFA between BCAA-pretreated and untreated patients[1].

The results of our review of a number of TACE- or RFA-treated patients demonstrated that the decline in serum Alb level was suppressed over 10 d post-treatment in BCAA-treated patients. BCAA pre-treatment might be effective in suppressing an early decline in serum Alb level after the therapeutic intervention. We inferred that the inflammation-inhibitory effect of BCAA treatment might be involved in the suppression of the decrease in serum Alb level[4,17-19] on the grounds that CRP elevation was suppressed in BCAA-treated patients, that the severity of fever was milder as a result of BCAA treatment, and that the decrease in serum Alb level was also to a lesser extent in patients with milder changes in CRP level. The following mechanism seemed likely to be operating: serum Alb level falls into a trough due to extravasation mainly into the embolized or ablated hepatic region as early as 2 d after TACE or RFA, and in patients receiving BCAA pre-treatment, its anti-inflammatory effect and sustained stimulation of mTOR from continued BCAA treatment lead to serum Alb level restoration nearly to the baseline level by day 10 post-intervention. While a direct hepatocyte damage-mitigating effect of BCAA treatment was demonstrated in an animal study[18,25,26], there was no significant difference in ΔAST or ΔALT between the BCAA-treated and untreated patients in this study; therefore, BCAA treatment is thought to be virtually devoid of hepatocyte damage-mitigating effect in the clinical setting.

The present results suggest that BCAA treatment prior to therapeutic intervention suppresses the decrease in serum Alb level associated with TACE or RFA and may reduce postoperative complications although confirmation of such effect observed in this study through prospective investigation and clarification of the underlying mechanism are needed.

COMMENTS

Background

Decrease in plasma albumin (Alb) level occurs early after therapeutic intervention such as transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) or radiofrequency ablation (RFA) for treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Measures to cope with hypoalbuminemia are needed in that therapeutic intervention options as well as the prognosis in HCC patients are dependent on this condition.

Research frontiers

When administered to patients with cirrhosis, branched-chain amino acids (BCAA) not only raises serum Alb level but also exerts a liver-protective effect such as lessening of oxidative stress. Authors investigated the usefulness of pre-intervention with BCAAs by comparing patients treated with BCAAs for at least 2 wk before TACE or RFA and those not receiving such pretreatment.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The inflammation-inhibitory effect of BCAA treatment might be involved in the suppression of decrease in serum Alb level on the grounds that C-reactive protein (CRP) elevation was suppressed in BCAA-treated patients, and that the decrease in serum Alb level was also to a lesser extent in patients with milder changes in CRP level.

Applications

Pre-intervention with BCAAs may hasten the recovery of serum Alb level and mitigate post-operative complications in patients undergoing TACE or RFA.

Terminology

In recent years, a liver-protective effect, e.g., lessening of oxidative stress, of BCAAs has been attracting attention and BCAA treatment has been reported to maintain skeletal muscles; these multifunctional pharmacological effects of this preparation have become the focus of increased interest.

Peer review

The study found BCAA pre-intervention could significantly suppress the development of post-operative hypoalbuminemia and reduce inflammatory reactions during the subsequent clinical course in 162 patients, the changes in serum Alb level were inversely correlated with CRP changes. It is very important for patients with HCC to avoid hypoalbuminemia after the treatment of TACE or RFA.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers: Ramani K, Villa-Trevino S, Zhang SJ, Zeng Z S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

References

- 1.Koda M, Ueki M, Maeda Y, Mimura KI, Okamoto K, Matsunaga Y, Kawakami M, Hosho K, Murawaki Y. The influence on liver parenchymal function and complications of radiofrequency ablation or the combination with transcatheter arterial embolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res. 2004;29:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.hepres.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Les I, Doval E, Flavià M, Jacas C, Cárdenas G, Esteban R, Guardia J, Córdoba J. Quality of life in cirrhosis is related to potentially treatable factors. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:221–227. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283319975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shiraki M, Nishiguchi S, Saito M, Fukuzawa Y, Mizuta T, Kaibori M, Hanai T, Nishimura K, Shimizu M, Tsurumi H, et al. Nutritional status and quality of life in current patients with liver cirrhosis as assessed in 2007-2011. Hepatol Res. 2013;43:106–112. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawaguchi T, Izumi N, Charlton MR, Sata M. Branched-chain amino acids as pharmacological nutrients in chronic liver disease. Hepatology. 2011;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1002/hep.24412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishikawa H, Osaki Y. Clinical significance of therapy using branched-chain amino acid granules in patients with liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res. 2014;44:149–158. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Limquiaco JL, Wong GL, Wong VW, Lai PB, Chan HL. Evaluation of model for end stage liver disease (MELD)-based systems as prognostic index for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:63–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang L, Li J, Yan JJ, Liu CF, Wu MC, Yan YQ. Prealbumin is predictive for postoperative liver insufficiency in patients undergoing liver resection. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:7021–7025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i47.7021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishikawa T. Branched-chain amino acids to tyrosine ratio value as a potential prognostic factor for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2005–2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i17.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Usui T, Moriwaki H, Hatakeyama H, Kasai T, Kato M, Seishima M, Okuno M, Ohnishi H, Yoshida T, Muto Y. Oral supplementation with branched-chain amino acids improves transthyretin turnover in rats with carbon tetrachloride-induced liver cirrhosis. J Nutr. 1996;126:1412–1420. doi: 10.1093/jn/126.5.1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suzuki K, Suzuki K, Koizumi K, Ichimura H, Oka S, Takada H, Kuwayama H. Measurement of serum branched-chain amino acids to tyrosine ratio level is useful in a prediction of a change of serum albumin level in chronic liver disease. Hepatol Res. 2008;38:267–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2007.00268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holecek M. Three targets of branched-chain amino acid supplementation in the treatment of liver disease. Nutrition. 2010;26:482–490. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2009.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishikawa T. Early administration of branched-chain amino acid granules. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4486–4490. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i33.4486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hidaka H, Nakazawa T, Kutsukake S, Yamazaki Y, Aoki I, Nakano S, Asaba N, Minamino T, Takada J, Tanaka Y, et al. The efficacy of nocturnal administration of branched-chain amino acid granules to improve quality of life in patients with cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:269–276. doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0632-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muto Y, Sato S, Watanabe A, Moriwaki H, Suzuki K, Kato A, Kato M, Nakamura T, Higuchi K, Nishiguchi S, et al. Effects of oral branched-chain amino acid granules on event-free survival in patients with liver cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:705–713. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marchesini G, Bianchi G, Merli M, Amodio P, Panella C, Loguercio C, Rossi Fanelli F, Abbiati R. Nutritional supplementation with branched-chain amino acids in advanced cirrhosis: a double-blind, randomized trial. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1792–1801. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00323-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plauth M, Cabré E, Riggio O, Assis-Camilo M, Pirlich M, Kondrup J, Ferenci P, Holm E, Vom Dahl S, Müller MJ, et al. ESPEN Guidelines on Enteral Nutrition: Liver disease. Clin Nutr. 2006;25:285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fukushima H, Miwa Y, Shiraki M, Gomi I, Toda K, Kuriyama S, Nakamura H, Wakahara T, Era S, Moriwaki H. Oral branched-chain amino acid supplementation improves the oxidized/reduced albumin ratio in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatol Res. 2007;37:765–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2007.00123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuwahata M, Kubota H, Katsukawa M, Ito S, Ogawa A, Kobayashi Y, Nakamura Y, Kido Y. Effect of branched-chain amino acid supplementation on the oxidized/reduced state of plasma albumin in rats with chronic liver disease. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2012;50:67–71. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.11-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schieke SM, Phillips D, McCoy JP, Aponte AM, Shen RF, Balaban RS, Finkel T. The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway regulates mitochondrial oxygen consumption and oxidative capacity. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:27643–27652. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603536200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cabibbo G, Latteri F, Antonucci M, Craxì A. Multimodal approaches to the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:159–169. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ijichi C, Matsumura T, Tsuji T, Eto Y. Branched-chain amino acids promote albumin synthesis in rat primary hepatocytes through the mTOR signal transduction system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;303:59–64. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00295-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsumura T, Morinaga Y, Fujitani S, Takehana K, Nishitani S, Sonaka I. Oral administration of branched-chain amino acids activates the mTOR signal in cirrhotic rat liver. Hepatol Res. 2005;33:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.hepres.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takeshita S, Ichikawa T, Nakao K, Miyaaki H, Shibata H, Matsuzaki T, Muraoka T, Honda T, Otani M, Akiyama M, et al. A snack enriched with oral branched-chain amino acids prevents a fall in albumin in patients with liver cirrhosis undergoing chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nutr Res. 2009;29:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nishikawa H, Osaki Y, Inuzuka T, Takeda H, Nakajima J, Matsuda F, Henmi S, Sakamoto A, Ishikawa T, Saito S, et al. Branched-chain amino acid treatment before transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1379–1384. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i12.1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iwasa J, Shimizu M, Shiraki M, Shirakami Y, Sakai H, Terakura Y, Takai K, Tsurumi H, Tanaka T, Moriwaki H. Dietary supplementation with branched-chain amino acids suppresses diethylnitrosamine-induced liver tumorigenesis in obese and diabetic C57BL/KsJ-db/db mice. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:460–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01402.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuwahata M, Kubota H, Kanouchi H, Ito S, Ogawa A, Kobayashi Y, Kido Y. Supplementation with branched-chain amino acids attenuates hepatic apoptosis in rats with chronic liver disease. Nutr Res. 2012;32:522–529. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]