Abstract

Endoscopic esophageal stent placement is widely used in the treatment of a variety of benign and malignant esophageal conditions. Self expanding metal stents (SEMS) are associated with significantly reduced stent related mortality and morbidity compared to plastic stents for treatment of esophageal conditions; however they have known complications of stent migration, stent occlusion, tumor ingrowth, stricture formation, reflux, bleeding and perforation amongst others. A rare and infrequently reported complication of SEMS is stent fracture and subsequent migration of the broken pieces. There have only been a handful of published case reports describing this problem. In this report we describe a case of a spontaneously fractured nitinol esophageal SEMS, and review the available literature on the unusual occurrence of SEMS fracture placed for benign or malignant obstruction in the esophagus. SEMS fracture could be a potentially dangerous event and should be considered in a patient having recurrent dysphagia despite successful placement of an esophageal SEMS. It usually requires endoscopic therapy and may unfortunately require surgery for retrieval of a distally migrated fragment. Early recognition and prompt management may be able to prevent further problems.

Keywords: Esophagus, Self-expanding metal stent, Stent complication, Stent fracture, Stent migration

Core tip: Esophageal self expanding metal stents are widely used for the treatment of a variety of benign and malignant esophageal conditions. A rare and infrequently reported complication of this procedure is stent fracture and subsequent migration of the broken pieces. There have only been a handful of case reports describing this problem. We report a case of spontaneous fracture of a nitinol esophageal self expanding metal stent, the first reported case from the United States, and review the available literature on this unusual occurrence.

INTRODUCTION

Esophageal stent placement is widely used for the palliative treatment of esophageal and gastric cardia cancer. More recently, fully covered esophageal stents have been used for benign esophageal conditions such as refractory stricture, tracheoesophageal fistula, iatrogenic perforation, and post-surgical leaks[1,2]. Esophageal stents have evolved from rigid polyvinyl plastic prostheses (“Celestin tubes”) to self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) which may be uncovered, partially covered, or fully covered. SEMS are associated with significantly reduced rates of stent related mortality and morbidity in the form of esophageal perforation and stent migration as compared to plastic stents[3]. SEMS offer a safe and effective means of treatment, which can be placed as an outpatient procedure at low costs[4].

However, SEMS are associated with their own complications. Early complications include chest pain, aspiration from gastroesophageal reflux, bleeding, perforation and stent migration. Delayed complications include stent migration, stent occlusion, tumor ingrowth or overgrowth, stricture formation, reflux, tracheoesophageal fistula formation, bleeding and perforation. Stent migration is the most common complication amongst all, with a frequency of 7%-75%[5,6]. A rare complication of esophageal SEMS is stent fracture described in a handful of case reports, dating as early as 1999 with periodic reports since then. We report a case of a spontaneously fractured nitinol SEMS, which is the first recorded instance in the United States and present a review of all previously published reports of esophageal SEMS fracture.

CASE REPORT

A 71-year old female with history of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the tongue was treated with radiation and surgical excision 10 years ago. She presented with worsening dyspnea, progressive dysphagia and weight loss. CT scan showed a subcarinal mediastinal mass with extension to the mid-esophagus and metastatic disease to the right upper lung. Endoscopic ultrasound with fine needle aspiration of a lymph node confirmed recurrence of SCC. Chemotherapy was begun and the esophageal lesion was treated with four rounds of liquid nitrogen cryotherapy resulting in shrinkage of the esophageal tumor with symptomatic improvement of her dysphagia.

One year later, she again developed dysphagia; repeat endoscopy showed a malignant stricture from 26 to 31 cm from the incisors. The stricture could only be traversed with an ultra-thin endoscope (outer diameter 5.5 mm) with some resistance. An 18 mm diameter by 12 cm long fully covered Nitinol SEMS (Bonastent, Standard Sci-Tech, Inc, Seoul, South Korea) was successfully deployed across the stricture with its proximal end at 24 cm. Radiographic images of the deployed stent revealed that it was correctly positioned and post-placement fluoroscopy showed complete passage of contrast. The patient also received targeted stereotactic radiotherapy to the right upper lobe of her lung after the stent was placed due to enlarging pulmonary lesions. The radiation field for the lung did not overlap the position of the esophageal stent.

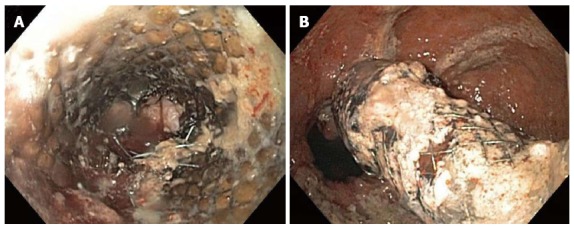

An episode of food impaction within the stent occurred 7 mo after deployment which was cleared endoscopically and she was found to have candida esophagitis with food stasis. During that endoscopy, it was noted that the esophageal stent had Nitinol wire disruption at the 9 o’clock position in the middle of her stent however, the stent lumen was intact. Four months later (11 mo after stent placement), she presented again with dysphagia. Endoscopy showed recurrence of stenosis from the tumor and a complete fracture of the stent at its mid-point with the proximal half embedded into the esophageal lumen and the distal fragment migrated and wedged in a hiatal hernia (Figure 1). Endoscopic dilation was performed using a 10 to 13.5 mm through-the-scope balloon catheter. After dilation, the distal fragment of the broken stent was gently directed down into the stomach. The retrieval lasso at the flared end of the distal fragment was grasped with retrieval forceps and the stent fragment was removed with careful maneuvering. The retrieval lasso at the flared end of the proximal piece was pulled, but the stent could not be moved due to embedding into the esophageal mucosa. The distal end of the proximal fragment was then grasped with an alligator forceps and turned inside out finally allowing successfully removal (Figure 2). A new 18 mm diameter by 10 cm long partially covered Nitinol SEMS (WallFlex, Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, United States) was deployed successfully under fluoroscopic and endoscopic guidance. The patient had significant improvement of her dysphagia and tolerated an oral diet. The patient died 3 mo later after an episode of massive hemoptysis.

Figure 1.

Endoscopic view of the fractured pieces of the esophageal self expanding metal stent with the proximal fragment embedded in the upper esophagus and the distal migrated fragment wedged in the hiatal hernia. A: Proximal fragment; B: Distal migrated fragment.

Figure 2.

Endoscopically removed pieces of the fractured esophageal self expanding metal stent.

DISCUSSION

Esophageal SEMS may be made of stainless steel or Nitinol. Nitinol is an alloy made of 55% nickel and 45% titanium, whose name is derived from its composition and its place of discovery: Nickel Titanium Naval Ordnance Laboratory[7]. Nitinol’s biocompatibility and the unusual and useful property of shape memory are the reasons for its widespread use in medicine. These stents may be exposed to significant stress-induced fatigue which over a period of time may cause weakening of the metal structure of the stent leading to subsequent fracture and fragmentation.

There have only been 8 published cases of complete esophageal SEMS fracture[8-14] (Table 1). These were all Nitinol stents from different manufacturers and the timing of stent fracture was anywhere from 8 to 40 wk after initial stent placement. The mean patient age was 66 years (range 50-79 years) with 5 male patients, 1 female patient and 2 with gender not reported. The presenting complaint in all cases was dysphagia. They were managed in a variety of different ways. In some cases, the fractured stent pieces were removed endoscopically and a new stent was placed. In other cases, a new stent was placed without removal of the fractured stent. Surgical removal of the distally migrated stent fragment was required in 2 instances. Three of the SEMS were fully covered stents and 5 uncovered. Half of these cases involved the Esophacoil SEMS, which is no longer available. There has been a report of an esophageal fractured stent fragment migrating into the stomach and resulting in the formation of a gastrocolic fistula[13] and thus whenever possible, migrated stents should be retrieved.

Table 1.

Review of all cases of complete esophageal self-expanding metal stent fracture

| Ref. | Country of Origin | Age (yr)/Gender | Reason for stent placement | Location | Pre-stent procedures | Initial stent | Stent fracture time after placement | Stent fracture management | Repeat stent placement |

| Current Case | United States | 71/female | Dysphagia from metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma | Mid esophagus | None | 18 mm × 120 mm, Fully covered Nitinol SEMS - Bonastent, Standard Sci-Tech, Inc, Seoul, South Korea | 45 wk | Proximal piece in the upper esophagus and distal fragment wedged in a hiatal hernia, both removed endoscopically | 18 mm × 100 mm, Partially covered Nitinol SEMS - Wallflex, Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, United States |

| Wadsworth et al[8], 2010 | United Kingdom | 75/female | Dysphagia from refractory benign esophageal stricture | Distal esophagus | None | 22 mm × 120 mm, Fully covered Nitinol SEMS - EBN stent, Diagmed Healthcare Ltd, Thirsk, United Kingdom | 8 wk | Proximal piece in esophagus removed endoscopically, and distal fragment migrated to the colon, passed rectally | Was under consideration at the time of publication |

| Wiedmann et al[9], 2009 | Germany | 69/not reported | Dysphagia from metastastic EAC | Distal esophagus | None | 22 mm × 160 mm, Fully covered Nitinol SEMS - Hanarostent, M.I.Tech Co., Inc, Seoul, South Korea | 20 wk | Proximal piece in esophagus and distal fragment in the gastric antrum, both removed endoscopically | 22 mm × 120 mm, Fully covered Nitinol SEMS - Hanarostent, M.I.Tech Co., Inc, Seol, South Korea |

| Chhetri et al[10], 2008 | United Kingdom | 50/male | Dysphagia from EAC | Distal esophagus | Palliative chemotherapy | 18 mm × 110 mm, Fully covered Nitinol SEMS - Choostent, M.I.Tech Co., Inc, Seoul, South Korea | 28 wk | Proximal piece in the esophagus removed endoscopically as it was causing trauma and bleeding, and the distal fragment wedged in the distal two-thirds of the tumor | 18 mm × 120 mm, Partially covered Nitinol SEMS - Ultraflex Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, United States, was placed across the exposed upper end of the tumor and through the prior fractured stent |

| Doğan et al[11], 2005 | Turkey | 50/not reported | Dysphagia from metastastic EAC | Distal esophagus | None | 18 mm × 100 mm, Uncovered Nitinol SEMS - Esophacoil, Medtronic InStent Inc., Minneapolis, MN, Unites States | 10 wk | Proximal piece with tumor overgrowth and partial obstruction in the esophagus and distal fragment migrated and left in the stomach | 18 mm, Uncovered Nitinol SEMS - Esophacoil, Medtronic InStent Inc., Minneapolis, MN, United States inserted through the proximal fractured fragment |

| Reddy et al[12], 2003 | United Kingdom | 76/male | Dysphagia from EAC at the GE junction | GE junction | Dilation and argon plasma ablation | 18 mm × 100 mm, Uncovered Nitinol SEMS - Esophacoil, Kimal PLC, Uxbridge, United Kindom | 22 wk | Proximal piece in the esophagus with tumor occlusion and the distal fragment in the stomach which subsequently migrated into the right inguinal hernia, removed surgically by enterotomy, followed by herniorrhaphy | Uncovered Nitinol SEMS - Esophacoil, Medtronic InStent Inc., Minneapolis, MN, United States inserted through the proximal fractured fragment |

| Reddy et al[12], 2003 | United Kingdom | 76/male (same patient) | Dysphagia from EAC at the GE junction | GE junction | None | Size NR, Uncovered Nitinol SEMS - Esophacoil, Kimal PLC, Uxbridge, United Kingdom | 23 wk | Stent fracture in 2 places with proximal piece in the esophagus, middle piece in the stomach and the distal piece in the small intestine, not removed as patient died due to aspiration pneumonia | None |

| Altiparmak et al[13], 2000 | Turkey | 52/male | Dysphagia from EAC | NR | None | Size NR, Uncovered Nitinol SEMS - Wallstent, Schneider Inc., Plymouth, MN, United States | 40 wk | Proximal piece in the esophagus and the distal fragment in the stomach causing a gastrocolic fistula with unsuccessful endoscopic removal requiring surgical gastrotomy and fistula repair | None |

| Grimley et al[14], 1999 | United Kingdom | 79/male | Dysphagia from refractory anastomotic stricture after resection of EAC | Proximal esophagus | Dilation of anastomotic stricture | 18 mm × 100 mm, Uncovered Nitinol SEMS - Esophacoil, Medtronic InStent Inc., Minneapolis, MN, Unites States | 8 wk | Proximal piece in the esophagus and the distal 2 cm fragment migrated into the stomach, subsequently passed rectally | Partially covered Nitinol SEMS - Ultraflex Boston Scientific, Galway, Ireland, was placed across the exposed upper end of the tumor and through the prior fractured stent |

SEMS: Self-expanding metal stent; EAC: Esophageal adenocarcinoma; GE: Gastroesophageal.

Partial Nitinol esophageal stent fracture has been reported more commonly, with 6 publications accounting for 33 patients[9,15-19]. However most of these cases did not need any intervention as it did not affect stent function and only 6 of these cases required placement of new stents through the lumen of the damaged stent due to symptomatic dysphagia, tumor ingrowth and stenosis. Since these stents did not fracture completely, migration of the stent was not an issue.

Fracture of Nitinol SEMS used for the management of malignant obstruction in other parts of the gastrointestinal tract have also been reported. One study reported 2 cases of partial break in the stent wall both in an uncovered and covered enteral Nitinol SEMS placed for symptomatic management of malignant gastric outlet obstruction, with the latter one requiring cutting of the broken part and placement of a second stent to manage food impaction[20]. Two case reports described complete circumferential stent fractures of enteral Nitinol SEMS, one with 2 consecutive fully covered enteral Nitinol SEMS placed for benign duodenal stricture in the same patient[21] and another with an uncovered Nitinol SEMS for duodenal obstruction from periampullary adenocarcinoma[22]. There have been 5 reports describing a total of 14 cases of partial as well as complete fractures of uncovered biliary Nitinol SEMS placed for palliation of malignant biliary obstruction[23-27]. There have also been 3 reports of fracture of colonic Nitinol SEMS placed for malignant large bowel obstruction[28-30].

The possibility of disease or treatment related factors leading to stent fracture have been considered. The use of balloon catheters to dilate Nitinol stents immediately post deployment to guarantee rapid and complete stent expansion to their maximum diameter has been associated with stent fracture in 1 reported case[17]. There have been some instances where esophageal stent breakage has occurred related to laser application to control bleeding from tumor ingrowth. In these cases the authors have postulated that thermal straining of the nitinol alloy could have resulted in stent fracture[18]. In another case series, high dose radiation therapy was associated with fracture of stainless steel tracheobronchial stents[31]. Our patient had also undergone stereotactic radiotherapy to the right upper lobe of her lung after the stent was placed. However the area that was irradiated did not involve the esophagus and hence most likely this did not contribute to the stent fracture.

Nitinol esophageal SEMS are a great improvement over Celestin tubes for the management of malignant dysphagia, mainly due to considerably easier and safer deployment. In addition, they are seeing wider use for management of refractory benign esophageal strictures. However, there are potential complications that may occur following successful deployment. Stent fracture is a rare but potentially dangerous occurrence that should be considered in a patient having recurrent dysphagia after successful placement of an esophageal SEMS. This complication may occur as early as 2 mo after placement. It usually requires endoscopic therapy and may unfortunately require surgery for retrieval of a distally migrated fragment. Early recognition and prompt management may be able to prevent further problems.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers: Bugaj AM, Xu XC S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

References

- 1.Sharma P, Kozarek R. Role of esophageal stents in benign and malignant diseases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:258–273; quiz 274. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kochman ML, McClave SA, Boyce HW. The refractory and the recurrent esophageal stricture: a definition. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:474–475. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yakoub D, Fahmy R, Athanasiou T, Alijani A, Rao C, Darzi A, Hanna GB. Evidence-based choice of esophageal stent for the palliative management of malignant dysphagia. World J Surg. 2008;32:1996–2009. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9654-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hindy P, Hong J, Lam-Tsai Y, Gress F. A comprehensive review of esophageal stents. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2012;8:526–534. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinez JC, Puc MM, Quiros RM. Esophageal stenting in the setting of malignancy. ISRN Gastroenterol. 2011;2011:719575. doi: 10.5402/2011/719575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baron TH. Expandable metal stents for the treatment of cancerous obstruction of the gastrointestinal tract. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1681–1687. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105313442206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kauffman GB, Mayo I. The story of nitinol: the serendipitous discovery of the memory metal and its applications. The Chemical Educator. 1997;2:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wadsworth CA, East JE, Hoare JM. Early covered-stent fracture after placement for a benign esophageal stricture. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:1260–1261; discussion 1261. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiedmann M, Heller F, Zeitz M, Mössner J. Fracture of a covered self-expanding antireflux stent in two patients with distal esophageal carcinoma. Endoscopy. 2009;41 Suppl 2:E129–E130. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1214661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chhetri SK, Selinger CP, Greer S. Fracture of an esophageal stent: a rare but significant complication. Endoscopy. 2008;40 Suppl 2:E199. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1077463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doğan UB, Eğilmez E. Broken stent in oesophageal malignancy: a rare complication. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2005;68:264–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reddy AV, Alwair H, Trewby PN. Fractured esophageal nitinol stent: Report of two fractures in the same patient. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:138–139. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Altiparmak E, Saritas U, Disibeyaz S, Sahin B. Gastrocolic fistula due to a broken esophageal self-expandable metallic stent. Endoscopy. 2000;32:S72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grimley CE, Bowling TE. Oesophageal metallic stent dysfunction: first reported case of stent fracture and separation. Endoscopy. 1999;31:S45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rana SS, Bhasin DK, Sidhu GS, Rawal P, Nagi B, Singh K. Esophageal nitinol stent dysfunction because of fracture and collapse. Endoscopy. 2009;41 Suppl 2:E170–E171. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1214771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cwikiel W, Tranberg KG, Cwikiel M, Lillo-Gil R. Malignant dysphagia: palliation with esophageal stents--long-term results in 100 patients. Radiology. 1998;207:513–518. doi: 10.1148/radiology.207.2.9577503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winkelbauer FW, Schöfl R, Niederle B, Wildling R, Thurnher S, Lammer J. Palliative treatment of obstructing esophageal cancer with nitinol stents: value, safety, and long-term results. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;166:79–84. doi: 10.2214/ajr.166.1.8571911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schoefl R, Winkelbauer F, Haefner M, Poetzi R, Gangl A, Lammer J. Two cases of fractured esophageal nitinol stents. Endoscopy. 1996;28:518–520. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1005534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grund KE, Storek D, Becker HD. Highly flexible self-expanding meshed metal stents for palliation of malignant esophagogastric obstruction. Endoscopy. 1995;27:486–494. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1005753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maetani I, Ukita T, Tada T, Shigoka H, Omuta S, Endo T. Metallic stents for gastric outlet obstruction: reintervention rate is lower with uncovered versus covered stents, despite similar outcomes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:806–812. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stern N, Smart H. Repeated enteral stent fracture in patient with benign duodenal stricture. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:655–657. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goenka AH, Garg PK, Sharma R, Sharma B. Spontaneous fracture of an uncovered enteral stent with proximal migration of fractured segment into cervical esophagus: first report. Endoscopy. 2009;41 Suppl 2:E204–E205. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1214864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rasmussen IC, Dahlstrand U, Sandblom G, Eriksson LG, Nyman R. Fractures of self-expanding metallic stents in periampullary malignant biliary obstruction. Acta Radiol. 2009;50:730–737. doi: 10.1080/02841850903039763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshida H, Mamada Y, Taniai N, Mizuguchi Y, Shimizu T, Aimoto T, Nakamura Y, Nomura T, Yokomuro S, Arima Y, et al. Fracture of an expandable metallic stent placed for biliary obstruction due to common bile duct carcinoma. J Nippon Med Sch. 2006;73:164–168. doi: 10.1272/jnms.73.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshida H, Tajiri T, Mamada Y, Taniai N, Kawano Y, Mizuguchi Y, Arima Y, Uchida E, Misawa H. Fracture of a biliary expandable metallic stent. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:655–658. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)01884-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peck R, Wattam J. Fracture of Memotherm metallic stents in the biliary tract. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2000;23:55–56. doi: 10.1007/s002709910008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tesdal IK, Adamus R, Poeckler C, Koepke J, Jaschke W, Georgi M. Therapy for biliary stenoses and occlusions with use of three different metallic stents: single-center experience. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1997;8:869–879. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(97)70676-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baraza W, Lee F, Brown S, Hurlstone DP. Combination endo-radiological colorectal stenting: a prospective 5-year clinical evaluation. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:901–906. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suzuki N, Saunders BP, Thomas-Gibson S, Akle C, Marshall M, Halligan S. Colorectal stenting for malignant and benign disease: outcomes in colorectal stenting. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1201–1207. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0556-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Odurny A. Colonic anastomotic stenoses and Memotherm stent fracture: a report of three cases. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2001;24:336–339. doi: 10.1007/s00270-001-0033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakajima Y, Kurihara Y, Niimi H, Konno S, Ishikawa T, Osada H, Kojima H. Efficacy and complications of the Gianturco-Z tracheobronchial stent for malignant airway stenosis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1999;22:287–292. doi: 10.1007/s002709900390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]