Abstract

Plasticity or evolution in behavioural responses are key attributes of successful animal invasions. In northern Australia, the invasive cane toad (Rhinella marina) recently invaded semi-arid regions. Here, cane toads endure repeated daily bouts of severe desiccation and thermal stress during the long dry season (April–October). We investigated whether cane toads have shifted their ancestral nocturnal rehydration behaviour to one that exploits water resources during the day. Such a shift in hydration behaviour could increase the fitness of individual toads by reducing exposure to desiccation and thermal stress suffered during the day even within terrestrial shelters. We used a novel method (acoustic tags) to monitor the daily hydration behaviour of 20 toads at two artificial reservoirs on Camfield station, Northern Territory. Remarkably, cane toads visited reservoirs to rehydrate during daylight hours, with peaks in activity between 9.00 and 17.00. This diurnal pattern of rehydration activity contrasts with nocturnal rehydration behaviour exhibited by adult toads in their native geographical range and more mesic parts of Australia. Our results demonstrate that cane toads phase shift a key behaviour to survive in a harsh semi-arid landscape. Behavioural phase shifts have rarely been reported in invasive species but could facilitate ongoing invasion success.

Keywords: invasive species, cane toad, Rhinella marina, plasticity, temporal niche shift

1. Introduction

Species are being translocated around the Earth as a result of both natural and human actions. However, only a small percentage of species that are transported across the globe become invasive. To become a successful invader, a species must pass through all four stages (transport, introduction, establishment and spread) of the invasion process [1]. Recently, there has been growing awareness that behavioural plasticity is a key mechanism of successful invaders [2]. Many successful invaders possess multiple correlated traits (behavioural syndromes) that allow them to pass through multiple stages of the invasion process [3]. For example, high activity and exploratory behaviour may increase the chances that an invader locates cargo and is transported to new locations, while boldness and aggression may enable colonists to secure essential resources necessary for successful establishment and spread in novel environments [2].

Temporal phase shifts in activity times may enable invaders to colonize novel habitats and allow individuals to access essential resources, avoid physiological stressors, or evade predators and competitors [4–6]. Such shifts in activity times may also allow invaders to cope with novel environments during the spread phase of the invasion [7]. When faced with novel selection pressures, individuals that employ flexible behaviours, for example switching activity times, may accrue survival or reproductive benefits [8].

One well-studied invasive species that has rapidly adapted to novel environments is the cane toad Rhinella marina [9,10]. This large, terrestrial toad recently invaded semi-arid regions of Australia which are hotter and drier than its native geographical range [7]. Unlike native desert-dwelling frogs that burrow and produce cocoons to reduce evaporative water loss, cane toads rely solely on behavioural means to maintain osmotic balance [11]. In mesic regions of Australia and their native range, adult toads are nocturnal and rehydrate at night through direct contact with water or moist surfaces [11–13]. Nocturnal activity, common in adult cane toads, is thought to reduce predation risk and limit exposure to thermal and hydration stressors most prevalent during the day [13].

Because cane toads living in the desert experience severe hydric and thermal stress in terrestrial shelters (deep soil cracks and grass clumps) where temperatures can exceed 40°C [9], we hypothesized that toads might shift their daily hydration behaviour from a nocturnal to a diurnal phase. Such behavioural plasticity could optimize the fitness of individuals by reducing their exposure to hydric and thermal stress, thus increasing survival and lifetime reproductive success. To investigate activity patterns of desert-dwelling cane toads, we fitted 20 adult toads with acoustic tags and monitored their usage of reservoirs during the early and late dry season.

2. Material and methods

We studied daily patterns in the hydration behaviour of cane toads near two bore-fed reservoirs on Camfield pastoral station (17°02′ S, 131°17′ E) in the Victoria River District, Australia. This semi-arid region experiences less than 500 mm of rain annually, most of which falls between December and February. During the dry season (April–November), small, bore-fed reservoirs (10–15 m diameter) are the only permanent water sources available to cane toads across much of the landscape (figure 1a). These reservoirs occur at approximately 10 km intervals and function as dry season refuges for cane toads [14].

Figure 1.

(a) Study site with a bore-filled reservoir in the foreground. (b) An adult cane toad fitted with an acoustic tag.

We captured five adult male and female toads at each of two reservoirs during late April 2010. Males were smaller than females (males: mean SUL = 109 mm, range 97–116 mm; mean mass = 195, range 165–230 g; females: mean SUL = 120 mm, range 87–132 mm; mean mass = 276 g, range 160–340 g). To each toad, we fitted a coded acoustic transmitter (T-9, Thelma Biotel, Norway; length: 16 mm; weight in water: 1.8 g; frequency: 69 kHz; ratio of transmitter mass in water to toad mass = 0.5–1.0%) using a metal chain-link waistband (figure 1b).

The acoustic transmitters emitted unique coded signals allowing individual recognition of toads. Signals from the transmitters were detected with a passive listening station (VR2W, VEMCO, Canada) suspended 1 m beneath a float in the middle of each reservoir. Listening stations only detect signals from acoustic tags through water, thus the toads had to be in the water for a signal to be detected. The short reception distance from the water's edge to the listening stations (less than 8 m) resulted in high signal detection [15].

Once a toad left the water, the signal was lost. We defined a visit as a period of detection that commenced when a toad was first detected in the water and finished when no signal was detected thereafter for 30 min. In this way, we determined the timing, number and duration of visits to reservoirs by cane toads. We obtained 140 422 data points for 20 individual toads monitored continuously during the early dry season (23 April 2010–20 May 2010), and a further 100 369 data points for six of these toads (four males and two females) which were still alive during the late dry season (16 August 2010–17 September 2010). Air temperatures during these two periods ranged from 13.0 to 31.7°C and 12.9 to 35.8°C at night, and 12.8 to 37.1°C and 13.6 to 40.0°C by day, respectively.

3. Results

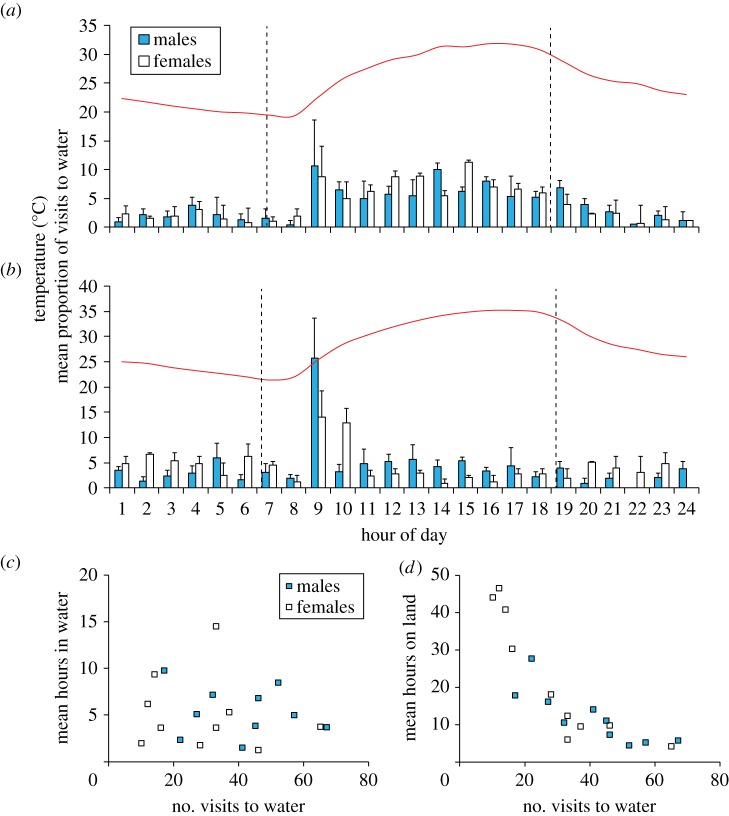

During the early dry season, we observed cane toads travelling from soil cracks to the water during the day. Acoustic tag data revealed that cane toads of both sexes visited the water during daylight hours, with peaks of activity between 9.00 and 17.00 (figure 2a). During the late dry season, toads of both sexes visited the water most often in the morning (figure 2b). During the early dry season, there were no sex differences in the mean duration spent immersed in the water (two factor ANOVA: dam F1,16 = 3.50, p = 0.08; sex F1,16 = 0.02, p = 0.88; dam × sex F1,16 = 0.30, p = 0.59) nor the mean time periods spent in terrestrial shelter sites (dam F1,16 = 0.03, p = 0.86; sex F1,16 = 2.88, p = 0.11; dam × sex F1,16 = 0.35, p = 0.56). The time spent on land or immersed in water was not correlated with toad body size or mass (all correlations, p > 0.05). Inspection of the data suggested that cane toads adopted different behavioural strategies to cope with high thermal and desiccation stress. The number of visits made to water was not correlated with the time during which cane toads spent immersed in water (figure 2c). However, some toads made infrequent visits to water and spent long periods in terrestrial shelters, whereas other toads made frequent visits to water and spent shorter periods in terrestrial shelters (figure 2d).

Figure 2.

Hour of day during which cane toads (n = 20) entered the water during the (a) early dry season and (b) late dry season (n = 6). Graphs show means and standard errors. Solid line shows mean air temperature, whereas dotted lines show sunrise and sunset. The mean number of visits made to water by cane toads is plotted against (c) the mean number of hours they spent immersed in water and (d) the mean number of hours they spent on land during the early dry season. (Online version in colour.)

4. Discussion

There is increasing evidence that behavioural plasticity may be a necessary prerequisite for successful invasion, particularly during the spread phase of invasions when species encounter environmental conditions very different to those of their native geographical range [2,8]. Our study provides evidence that daily temporal shifts in key behaviours may have facilitated the spread of an invasive, normally nocturnal amphibian into drier, hotter regions than those experienced in its native geographical range.

The desert-dwelling toads that we tracked displayed a striking pattern for diurnal hydration behaviour. Over 90% of visits by cane toads to the water were made during daylight hours, with peaks in activity around 9.00 and 17.00 (figure 2). By contrast, all prior studies of adult cane toads from their native geographical range and Australia have found that adult toads remain inactive within shelter sites by day and migrate to water sources at night to hydrate [11–13,16,17]. In previous studies, toads residing in daytime refuges experienced little thermal stress; for example, body temperatures of adult toads inside burrows on Orpheus Island (QLD) did not exceed 30°C [18]. By contrast, temperatures of water-saturated plaster toad models placed inside deep soil cracks and under grass tussocks on our study site exceeded 40°C and lost more than 40% of their mass in 24 h [15]. Hence, cane toads at our study sites have probably phase shifted from their normally nocturnal hydration behaviour to diurnal rehydration behaviour to avoid lethal thermal and hydric stress in terrestrial shelter sites [9,14]. Because cane toads can attain high densities on our study site [14], intraspecific competition for diurnal shelter sites might further explain why cane toads have shifted their activity times. Alternatively, cane toads might visit the water by day to avoid nocturnal predators; however, diurnal raptors are the major predator of adult cane toads at our study site [14]. Indeed, the risk of diurnal predation seems minor relative to the lethal environmental conditions that confront cane toads daily during the long dry season.

Although daily activity patterns were once considered ‘fixed’ traits, evidence from both field and laboratory studies suggests that phase shifts of key behaviours may be more widespread than previously thought [19,20]. Shifts from nocturnal to diurnal behaviour have rarely been reported in invasive species [4], but may allow some invaders to survive in novel or physiologically challenging environments. Our study shows how phenotypic plasticity can facilitate a biological invader's spread into a novel and physiologically challenging environment.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ben Wratten and Tom Nichols for logistical support, and two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments.

Ethics approval was provided by the University of Sydney Animal Ethics Committee (L04/9-2009/3/5132).

Data accessibility

Data available from the Dryad Digital Repository: Dryad http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.nm12c.

Funding statement

Financial support was provided by the Hermon Slade Foundation (M.L., J.K.W., T.D.) and Australian Research Council (J.K.W.).

References

- 1.Blackburn TM, Pysek P, Bacher S, Carlton JT, Duncan RP, Jarosik V, Wilson JRU, Richardson DM. 2011. A proposed unified framework for biological invasions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 26, 333–339 (doi:10.1016/j.tree.2011.03.023) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chapple DG, Simmonds SM, Wong BBM. 2012. Can behavioral and personality traits influence the success of unintentional species introductions? Trends Ecol. Evol. 27, 57–64 (doi:10.1016/j.tree.2011.09.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sih A, Cote J, Evans M, Fogarty S, Pruitt J. 2012. Ecological implications of behavioural syndromes. Ecol. Lett. 15, 278–289 (doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01731.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrington LA, Harrington AL, Yamaguchi N, Thom MD, Ferreras P, Windham TR, MacDonald DW. 2009. The impact of native competitors on an alien invasive: temporal niche shifts to avoid interspecific aggression? Ecology 90, 1207–1216 (doi:10.1890/08-0302.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kronfeld-Schor N, Dayan T. 2003. Partitioning of time as an ecological resource. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 34, 153–181 (doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132435) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fenn MGP, Macdonald DW. 1995. Use of middens by red foxes: risk reverses rhythms of rats. J. Mammal. 76, 130–136 (doi:10.2307/1382321) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tingley R, Greenlees MJ, Shine R. 2012. Hydric balance and locomotor performance of an anuran (Rhinella marina) invading the Australian arid zone. Oikos 121, 1959–1965 (doi:10.1111/j.1600-0706.2012.20422.x) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wright TF, Eberhard JR, Hobson EA, Avery ML, Russello MA. 2010. Behavioral flexibility and species invasions: the adaptive flexibility hypothesis. Ethol. Ecol. Evol. 22, 393–404 (doi:10.1080/03949370.2010.505580) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jessop TS, Letnic M, Webb JK, Dempster T. 2013. Adrenocortical stress responses influence an invasive vertebrate's fitness in an extreme environment. Proc. R. Soc. B 280, 20131444 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.1444) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phillips BL, Brown GP, Webb JK, Shine R. 2006. Invasion and the evolution of speed in toads. Nature 439, 803 (doi:10.1038/439803a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seebacher F, Alford RA. 1999. Movement and microhabitat use of a terrestrial amphibian (Bufo marinus) on a tropical island: Seasonal variation and environmental correlates. J. Herpetol. 33, 208–214 (doi:10.2307/1565716) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown GP, Kelehear C, Shine R. 2011. Effects of seasonal aridity on the ecology and behaviour of invasive cane toads in the Australian wet-dry tropics. Funct. Ecol. 25, 1339–1347 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2435.2011.01888.x) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zug GR, Zug PB. 1979. The marine toad, Bufo marinus: a natural history resume of native populations. Smithson. Contrib. Zool. 284, 1–58 (doi:10.5479/si.00810282.284) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Florance D, Webb JK, Dempster T, Kearney MR, Worthing A, Letnic M. 2011. Excluding access to invasion hubs can contain the spread of an invasive vertebrate. Proc. R. Soc. B 278, 2900–2908 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.0032) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Letnic M, Webb JK, Jessop TS, Florance D, Dempster T. 2014. Artificial water points facilitate the spread of an invasive vertebrate in arid Australia. Journal of Applied Ecology. (doi:10.1111/1365-2664.1223) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwarzkopf L, Alford RA. 1996. Desiccation and shelter-site use in a tropical amphibian: comparing toads with physical models. Funct. Ecol. 10, 193–200 (doi:10.2307/2389843) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tingley R, Shine R. 2011. Desiccation risk drives the spatial ecology of an invasive anuran (Rhinella marina) in the Australian semi-desert. PLoS ONE 6, 1–6 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025979) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seebacher F, Alford RA. 2002. Shelter microhabitats determine body temperature and dehydration rates of a terrestrial amphibian (Bufo marinus). J. Herpetol. 36, 69–75 (doi:10.1670/0022-1511(2002)036[0069:smdbta]2.0.co;2) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hut RA, Kronfeld-Schor N, van der Vinne V, De la Iglesia H. 2012. In search of a temporal niche: environmental factors. In Progress in brain research (eds Kalsbeek A, Merrow M, Roenneberg T, Foster RG.), pp. 281–304 Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mrosovsky N, Hattar S. 2005. Diurnal mice (Mus musculus) and other examples of temporal niche switching. J. Comp. Physiol. A Neuroethol. Sens. Neural Behav. Physiol. 191, 1011–1024 (doi:10.1007/s00359-005-0017-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data available from the Dryad Digital Repository: Dryad http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.nm12c.