Abstract

Objective To examine how the results of network meta-analyses are reported.

Design Methodological systematic review of published reports of network meta-analyses.

Data sources Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Medline, and Embase, searched from inception to 12 July 2012.

Study selection All network meta-analyses comparing the clinical efficacy of three or more interventions in randomised controlled trials were included, excluding meta-analyses with an open loop network of three interventions.

Data extraction and synthesis The reporting of the network and results was assessed. A composite outcome included the description of the network (number of interventions, direct comparisons, and randomised controlled trials and patients for each comparison) and the reporting of effect sizes derived from direct evidence, indirect evidence, and the network meta-analysis.

Results 121 network meta-analyses (55 published in general journals; 48 funded by at least one private source) were included. The network and its geometry (network graph) were not reported in 100 (83%) articles. The effect sizes derived from direct evidence, indirect evidence, and the network meta-analysis were not reported in 48 (40%), 108 (89%), and 43 (36%) articles, respectively. In 52 reports that ranked interventions, 43 did not report the uncertainty in ranking. Overall, 119 (98%) reports of network meta-analyses did not give a description of the network or effect sizes from direct evidence, indirect evidence, and the network meta-analysis. This finding did not differ by journal type or funding source.

Conclusions The results of network meta-analyses are heterogeneously reported. Development of reporting guidelines to assist authors in writing and readers in critically appraising reports of network meta-analyses is timely.

Introduction

When several healthcare interventions are available for the same condition, the corresponding network of results from randomised controlled trials must be considered (that is, which of the considered interventions have been compared against each other or against a common comparator such as placebo).1 2 A network meta-analysis allows for a quantitative synthesis of the network by combining direct evidence from comparisons of interventions within randomised trials and indirect evidence across randomised trials on the basis of a common comparator.3 4 5 6

Networks of trials and network meta-analyses are increasingly used to evaluate healthcare interventions.7 8 9 10 11 Compared with pairwise meta-analyses, network meta-analyses allow for visualisation of a larger amount of evidence, estimation of the relative effectiveness among all interventions (even if some head to head comparisons are lacking), and rank ordering of the interventions.

The conduct of network meta-analyses poses multiple challenges. Several reviews have explained how to approach these challenges in practice11 12 13; others have evaluated how indirect comparison meta-analyses and network meta-analyses have been conducted and reported.8 9 14 15 Most reviews have focused on checking the validity of key assumptions required in network meta-analyses (homogeneity, similarity/transitivity, consistency, or an overarching assumption of exchangeability); others have assessed the presence of essential methodological components of the systematic review process (for example, conducting a literature search and assessing the risk of bias of individual studies).10 These reviews did not evaluate the presentation of findings in reports of network meta-analyses.

Although reporting guidelines have been developed for systematic reviews and pairwise meta-analyses, we lack reporting guidelines for network meta-analyses. An international group is preparing an extension of the PRISMA statement for network meta-analyses. Inadequate reporting of findings and inadequate evaluation of the required assumptions may impede confidence in the findings and conclusions of network meta-analyses.16 Reports of network meta-analyses should allow the reader to assess the amount of evidence in the network of randomised trials and the relative effect sizes between interventions, along with their uncertainty.9 17

On the basis of a previous methodological systematic review of published reports of network meta-analyses,10 we aimed to examine how network meta-analysis results are reported.

Methods

Selection of articles

The search strategy and the selection criteria for reports of network meta-analyses have been described elsewhere.10 In brief, we considered networks of randomised trials that assessed three or more treatments but excluded meta-analyses with an open loop network of three interventions. The articles were screened from a sample of 893 potentially relevant publications indexed in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Medline, and Embase. The date of the last search was 12 July 2012. We identified three additional network meta-analyses from methodological articles. Two independent reviewers excluded non-network meta-analysis reports on the basis of the title and abstract of retrieved citations, and the full text articles were then evaluated according to pre-specified eligibility criteria. Disagreements were discussed to reach consensus.

Data extraction

We used a standardised data collection form to collect all data, for general characteristics and those pertaining to reporting of results, from 121 original reports of network meta-analyses and all supplementary appendices referenced in the articles, when available. Two reviewers independently extracted all data for a random sample of 20% of reports, except items that involved subjective interpretation, which were extracted independently and in duplicate for all reports. These items were the information on the structure of the network, whether the authors applied a Bayesian approach, which types of prior distributions for the basic parameters and the between trial variance were used, and whether the authors applied a method to investigate the impact of effect modifiers. Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

General characteristics

We collected data on the following general characteristics: type of journal (general or specialty), funding source (we classified network meta-analyses as having public funding if they were explicitly not funded and were conducted by academic authors or were funded by a public source, private funding if they were funded by at least one private source, and unclear funding if the authors did not report any information on the funding), type of interventions included in the network (pharmacological, non-pharmacological (defined as any intervention that did not include an active substance), or both), the type of outcome (binary, continuous, or time to event) and number of outcomes assessed per network meta-analysis, the number of printed pages (excluding the supplement or appendices), existence of a supplement or appendix, and the number of tables and figures (including the supplement or appendices).

Statistical aspects

We evaluated whether the authors applied a Bayesian approach, because this affects the reporting of results such as treatment rankings. In that case, we also assessed whether the authors used non-informative or informative priors for the basic parameters and the between trial variance.18 We also assessed whether the authors reported a method to investigate non-transitivity, a key to the validity of a network meta-analysis, which occurs when studies are not sufficiently similar in important clinical and methodological characteristics (effect modifiers).11 In accordance with Donegan and colleagues,19 we considered two methods: comparing patients’ or trials’ characteristics across treatment comparisons (for example, using descriptive statistics describing the characteristics across the comparisons) and investigating potential treatment effect modifying covariates (for example, using subgroup analysis or network meta-regression analysis).

Presentation of results

In accordance with recommendations from Ioannidis,20 Mills and colleagues,21 Cipriani and colleagues,11 and Ades and colleagues,12 we chose items to assess the reporting of the amount of evidence in the network of randomised trials, and of effect size estimates for pairwise comparisons between interventions. Furthermore, we assessed the reporting of rank ordering of interventions.

Amount of evidence in network of randomised trials

We assessed whether the reports included data to allow for gauging of the description of the network and its geometry. In particular, we assessed whether each report allowed for explicit identification of the interventions included in the network, the direct comparisons between the interventions, and the number of randomised trials and patients for each comparison. We also assessed whether a network graph or diagram was reported. In cases of star networks (that is, all interventions were compared with a common comparator but not against each other) and fully connected networks (all interventions were compared with each other), we considered that the network structure was clear provided that the authors explicitly mentioned the interventions and direct comparisons between the interventions included in the network.

Effect size estimates for pairwise comparisons between interventions

We evaluated whether the following components were reported: results of all individual randomised trials used in the network meta-analysis (summary data for each intervention group or estimates of treatment effect) and effect estimates with measures of uncertainty (such as confidence intervals, standard error, variance) from pairwise meta-analyses (direct evidence), indirect comparison meta-analyses (indirect evidence), or network meta-analyses (mixed evidence). In the case of the last of these, we assessed the reporting of all pairwise comparisons between interventions or only some selected pairwise comparisons between interventions (for example, all comparisons with placebo or reference intervention). We also assessed how these effect sizes were reported. Possible formats included a table, a matrix, a forest plot, a network graph (each edge labelled with the corresponding effect size), or narrative reporting in the results section.

Rank ordering of interventions

We assessed whether the reports gave some form of rank ordering of interventions. We assessed whether the authors presented the probabilities of each intervention being the best, the probabilities of each intervention taking each possible rank (in an absolute or cumulative ranking curve), or the mean ranks (or the surface under the cumulative ranking curve) and whether authors stated which intervention was the best. We also assessed whether the authors considered the uncertainty in rank ordering (by reporting confidence/credible intervals for the ranks or by reporting all probabilities for each intervention with each possible rank, in an absolute or cumulative ranking curve22).

Composite outcome assessing inadequate reporting

We built a composite outcome describing inadequate reporting of results based on guidelines from Ioannidis,20 Mills and colleagues,21 Ades and colleagues,12 and Cipriani and colleagues.11 We considered reporting to be inadequate in the case of absence of one of the following items: no reporting of interventions included in the network, direct comparisons between interventions, and number of randomised trials and patients for each comparison; or no reporting of results from direct, indirect, or mixed evidence.

Statistical analysis

We summarised quantitative data as medians and interquartile ranges and categorical data as numbers and percentages. We used the Fisher exact test for categorical data to analyse the composite outcome. All tests were two sided, and we considered P<0.05 to be significant. We used SAS 9.3 for statistical analyses.

Results

General characteristics

We identified 121 eligible reports of network meta-analyses (table 1): 55 (45%) published in general journals and 66 (55%) in specialty journals; 55 (45%) network meta-analyses were funded by public sources and 48 (40%) by at least one private source. A total of 100 (83%) reports assessed pharmacological interventions. The median number of outcomes assessed per network meta-analysis was 2 (interquartile range 1-3). In all, 70 (58%) reports of network meta-analyses included a supplement or appendix.

Table 1.

General characteristics of 121 reports of network meta-analyses

| Item and subcategory | No (%) of reports |

|---|---|

| Journal type: | |

| General journal | 55 (45) |

| Specialty journal | 66 (55) |

| Funding source: | |

| Private (at least one private source) | 48 (40) |

| Public | 55 (45) |

| Unclear | 18 (15) |

| Type of intervention assessed: | |

| Pharmacological intervention | 100 (83) |

| Non-pharmacological intervention | 11 (9) |

| Both (pharmacological and non-pharmacological intervention) | 10 (8) |

| Bayesian statistical approach: | 91 (75) |

| Basic parameter: | |

| Non-informative prior | 51/91 (56) |

| Informative prior | 0 (0) |

| Not reported | 40/91 (44) |

| Between trial variance: | |

| Non-informative prior | 30/91 (33) |

| Informative prior | 4/91 (4) |

| Not reported | 57/91 (63) |

| Methods to assess non-transitivity: | 43 (36) |

| Comparing patients’ or trials’ characteristics (across comparisons) | 40/43 (93) |

| Investigating potential intervention effect modifying covariates | 3/43 (7) |

| Type of outcomes: | |

| Binary | 78 (64) |

| Continuous | 28 (23) |

| Time to event: | 15 (12) |

| No of outcomes assessed per network* | 2 (1-3) |

| No of printed pages* | 11 (9-15) |

| Supplement or appendix published | 70 (58) |

| No of tables per network* | 5 (3-6) |

| No of figures per network* | 3 (2-5) |

*Data are medians (interquartile range).

Statistical aspects

Overall, 91 (75%) network meta-analyses applied a Bayesian approach: 51 used non-informative priors for the basic parameters, and 30 used them for the between trial variance. In all, 43 (36%) used a method to assess non-transitivity.

Amount of evidence in the network of randomised trials

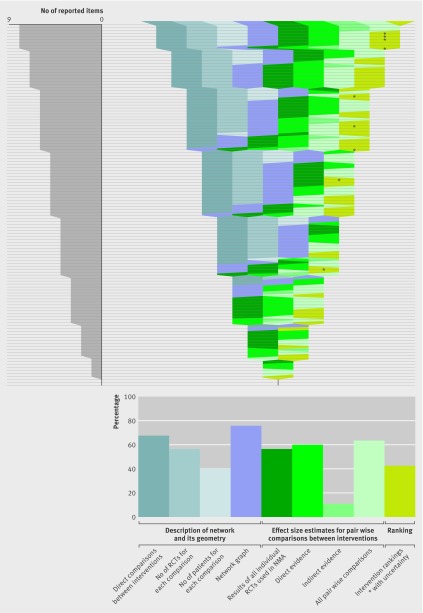

Of 121 network meta-analyses, 52 (43%) did not report the number of randomised trials for each comparison and 96 (79%) did not report the number of patients (table 2). Overall, 100 (83%) network meta-analyses did not give a description of the network (that is, the interventions included in the network, direct comparisons between interventions, number of randomised trials and patients for each comparison) and its geometry (a network graph or information needed to know the network structure) (table 2, figure, appendix table A).

Table 2.

Presentation of results in 121 reports of network meta-analysis. Values are numbers (percentages)

| Items—yes if reported | Overall (n=121) | General journals (n=55) | Specialty journals (n=66) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amount of evidence in network of randomised trials | |||

| Interventions included in network | 121 (100) | 55 (100) | 66 (100) |

| Direct comparisons between interventions | 82 (68) | 39 (71) | 43 (65) |

| No of trials for each comparison | 69 (57) | 34 (62) | 35 (53) |

| No of patients for each comparison | 25 (21) | 14 (25) | 11 (17) |

| Network graph* | 89 (74) | 44 (80) | 45 (68) |

| Effect size estimates for pairwise comparisons between interventions | |||

| Results of all individual trials used in network meta-analysis | 68 (56) | 28 (51) | 40 (61) |

| Direct evidence | 73 (60) | 33 (60) | 40 (61) |

| Indirect evidence | 13 (11) | 6 (11) | 7 (11) |

| Mixed evidence | 78 (64) | 34 (62) | 44 (67) |

| Effect estimates for some selected pairwise comparisons between interventions from network meta-analysis | 43 (36) | 21 (38) | 22 (33) |

| Format of results†: | 78 (64) | 29 (53) | 49 (74) |

| Table | 41 (34) | 24 (44) | 17 (26) |

| Forest plot | 7 (6) | 3 (5) | 4 (6) |

| Matrix | 6 (5) | 3 (5) | 3 (5) |

| Figure | 4 (3) | 2 (4) | 2 (3) |

| Text | |||

| Rank order of interventions | |||

| Rank order of interventions‡ | 52/91 (57) | 22/38 (58) | 30/53 (57) |

| Rank order of interventions with uncertainty | 9/52 (17) | 6/22 (27) | 3/30 (10) |

*7 star networks and 4 fully connected networks reported no network graph, but authors explicitly mentioned interventions and direct comparisons in network.

†Multiple answers were possible, so total does not equal 100%.

‡Network meta-analyses that did not use Bayesian approach cannot derive intervention rankings; 91 network meta-analyses used Bayesian approach.

Reporting items for results of network meta-analyses. The idea is to show which items were reported in each of the 121 network meta-analyses. Each horizontal line of the gap chart corresponds to one network meta-analysis report. A specific colour was attributed to each of the 10 items studied. The colour bands show which of these items (labelled at the top) were reported for each network meta-analysis. Items were grouped into three categories: 4 items in blue pertain to the description of network, and 1 item in purple pertains to its geometry (network graph); 4 items in green pertain to effect size estimates for pairwise comparisons between interventions; 1 item pertains to intervention ranking. The 121 network meta-analysis reports were sorted according to the total number of reported items, in decreasing order. The diagram on the left shows the distribution of the total number of reported items across the 121 network meta-analyses. The diagram at the bottom shows the proportion of network meta-analysis reports that reported each item

Effect size estimates for pair-wise comparisons between interventions

Of 121 reports of network meta-analyses, 53 (44%) did not give the results of all individual randomised trials used in the network meta-analysis. A total of 48 (40%) did not report the effect sizes for all pairwise comparisons between interventions with a measure of uncertainty derived from pairwise meta-analyses (that is, direct evidence), and 108 (89%) did not give indirect evidence (the effect sizes for all pairwise comparisons between interventions with a measure of uncertainty from indirect evidence). In all, 109 (90%) reports did not give both direct and indirect evidence and 71 (59%) did not give both direct and mixed evidence (that is, the effect sizes for all pairwise comparisons between interventions with a measure of uncertainty from network meta-analyses); 112 (93%) did not describe direct as well as indirect and mixed evidence (table 2, figure , appendix table A).

Rank order of interventions

Among 91 network meta-analyses with a Bayesian approach, 52 reports gave the rank order of interventions; 40 of these gave the probabilities of each intervention being the best, 7 used absolute or cumulative rankograms, and 5 stated which intervention was the best. However, 43 of the 52 reports did not report a measure of uncertainty in ranking (table 2). When reported, the uncertainty in ranking was assessed by absolute or cumulative rankograms (7/9) or confidence/credible intervals (2/9).

Composite outcome assessing inadequate reporting

Overall, 119 (98%) reports of network meta-analyses showed inadequate reporting of results (that is, the authors did not report the interventions included in the network or direct comparisons between the interventions; number of randomised trials and patients for each comparison; or results from direct, indirect, or mixed evidence). This finding did not differ by journal type (general journals: 100%, 95% confidence interval 94% to 100%; specialty journals: 97%, 93% to 100%; P=0.5) or funding source (public: 98%, 94% to 100%; private: 100%, 93% to 100%; P=0.53).

Discussion

Our sample of 121 network meta-analyses included a large number of recently published network meta-analyses covering a wide range of medical areas. Essential components of reporting results of network meta-analyses were missing in most of the articles.

An important element in understanding a network meta-analysis is assessing the network geometry.20 21 Firstly, knowing precisely the shape of the network (that is, which interventions are included in the network and which interventions have been compared against each other in randomised trials) is a preliminary step for researchers and readers to assess the available evidence base. The geometry of the network may show that some (head to head) comparisons have been ignored or that some comparators were preferred.23 24 25 26 Identifying trials that have not been conducted may help in designing the research agenda. Secondly, the reader should consider the number of randomised trials and patients for each comparison. In fact, differences in the numbers and sizes of trials across interventions and comparisons may affect the reliability of some network meta-analyses’ estimates.27 The amount of available evidence may be imbalanced because of differential reporting bias across comparisons, which may substantially affect the results.28 Thirdly, readers should be able to assess whether similar but not identical interventions were grouped, which may weaken the interpretability of a network meta-analysis. For transparency, authors of network meta-analyses should clearly report the interventions included in the network, the direct comparisons between the interventions, and the number of randomised trials and patients for each comparison and should give a graphical representation of the network.11 However, only 17% of our reports of network meta-analyses adequately described the network and its geometry.

The most important element for readers may be the assessment of the relative effectiveness of the considered interventions. When direct and indirect evidence is available, a potential difficulty is choosing among direct, indirect, and mixed evidence, especially with discrepancies between direct and indirect evidence. Checking consistency is a preliminary step before proceeding to the network meta-analysis.29 Empirical studies have detected statistically significant inconsistency between direct and indirect comparisons in 14% of 112 single loops of evidence and 2-9% of 303 loops from complete networks, depending on the measure of effect and the method for estimating heterogeneity.30 31 However, excluding inconsistency on the basis of the results of statistical tests is difficult because the results may suggest no major inconsistency although it may be present. Moreover, statistically non-significant inconsistency does not necessarily imply clinical consistency.30 Consequently, readers should be able to compare effect estimates from direct, indirect, and mixed evidence, even in the absence of statistical inconsistency. Indirect evidence may be considered of lower quality than evidence from head to head trials because it is prone to similarity/transitivity problems.32 However, in some cases, indirect evidence may be more reliable than direct and mixed evidence,33 34 35 and when trials are similarly biased an indirect comparison is not biased.36 Transparency is important to allow readers to make their own judgment according to explicitly presented discrepancies. However, only 10% of our network meta-analysis reports gave both direct and indirect evidence and only 7% gave direct, indirect, and mixed evidence.

One appealing feature of a network meta-analysis is the rank ordering of interventions. This information is attractive for clinical researchers and physicians because it seems to respond to their main concern: determining the best available intervention. However, an intervention may be ranked highly even though it was assessed in only a few trials and with a few patients, which resulted in a misleadingly strong endorsement for the intervention despite large uncertainty. Discussion is ongoing as to whether rankings must be reported and are appropriate to derive inference. Clinical researchers and physicians should always be able to examine the uncertainty in the ranking of interventions, because the difference between interventions might be small and not clinically relevant. However, only 17% of our network meta-analysis reports that ranked interventions reported the uncertainty.

Strengths and limitations of study

To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has tackled the problem of presentation of results in a large sample, such as 121 network meta-analyses. Recently, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality assessed the statistical methods used in a sample of 34 closed loop Bayesian mixed treatment comparisons,15 37 and Tan et al explored the presentational approaches used in the United Kingdom for reporting evidence synthesis of 19 reports of studies involving indirect and mixed treatment comparisons.38 These authors focused mainly on the statistical methods or possible formats of results but did not assess reporting of the amount of evidence in the network of trials (that is, the interventions included in the network, direct comparisons between the interventions, number of trials and patients for each comparison, network graph/or diagram) or the reporting of effect estimates with uncertainty from direct, indirect, or mixed evidence.

Our study had some limitations. Several journals have space constraints, so the study authors may have omitted important details from their reports or key information may have been deleted during the publication process. Nevertheless, most journals now allow an online appendix for extended descriptions of methods and results, and we assessed all data from both the original reports of network meta-analyses and the supplementary appendices when available. Another limitation is that we searched only for reports of network meta-analyses published in journals and did not search for health technology assessment (HTA) reports. Network meta-analyses are increasingly being used to support HTAs. However, identifying network meta-analyses in HTA reports by usual search strategies is difficult. The reporting of results may differ in HTA reports and journal articles. Finally, we built a composite outcome based on the available recommendations from Ioannidis,20 Mills and colleagues,21 Ades and colleagues,12 and Cipriani and colleagues,11 as a possible core set of information that we would like to see in any report of a network meta-analysis. However, we acknowledge that consensus is lacking on which items should be required in network meta-analysis reports. This is an area of ongoing debate.

Conclusions

Our study shows that the results of network meta-analyses are heterogeneously reported. These results might reflect the fact that we lack a general consensus on what should be reported in a network meta-analysis. This review reinforces the need to develop reporting guidelines for network meta-analyses to facilitate their reporting. It may provide a basis for the future development of a quality assessment tool for reporting network meta-analyses and aiding appropriate interpretation.

What is already known on this topic

The findings from network meta-analyses may be difficult for clinicians and decision makers to interpret

Inadequate reporting of results may affect the interpretation of network meta-analyses and mislead clinical researchers

Reports of network meta-analysis should allow the reader to assess the amount of evidence in the network of trials and the relative effectiveness of the considered interventions

What this study adds

The findings from network meta-analyses are heterogeneously reported

These results might reflect the lack of a general consensus on what should be reported in a network meta-analysis

A clear need exists to extend reporting guidelines to network meta-analyses to improve the reporting of network meta-analyses

We thank Elise Diard (French Cochrane Center) and Monica Serrano (monicaserrano.com) for their help with the infographics and Laura Smales for language revision of manuscript. We are particularly indebted to Josefin Blomkvist for data extraction of items on the Bayesian approach and type of prior distribution for the basic parameters and the variance.

Contributors: AB was involved in the study conception, search for trials, selection of trials, data extraction, data analysis, interpretation of results, and drafting the manuscript. LT was involved in the study conception, search for trials, selection of trials, interpretation of results, and drafting the manuscript. RS was involved in data extraction, interpretation of results, and drafting the manuscript. PR was involved in study conception, interpretation of results, and drafting the manuscript. PR is the guarantor.

Funding: AB was funded by an academic grant for doctoral students from Pierre et Marie Curie University, France. Our team is supported by an academic grant for the programme Equipe Espoirs de la Recherche, from the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale, France. The funding agencies had no role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or preparation and review of the manuscript.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not needed.

Transparency: PR (the manuscript’s guarantor) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2014;348:g1741

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

References

- 1.Salanti G, Kavvoura FK, Ioannidis JP. Exploring the geometry of treatment networks. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:544-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ioannidis JP, Karassa FB. The need to consider the wider agenda in systematic reviews and meta-analyses: breadth, timing, and depth of the evidence. BMJ 2010;341:c4875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Higgins JP, Whitehead A. Borrowing strength from external trials in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 1996;15:2733-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lumley T. Network meta-analysis for indirect treatment comparisons. Stat Med 2002;21:2313-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salanti G, Higgins JP, Ades AE, Ioannidis JP. Evaluation of networks of randomized trials. Stat Methods Med Res 2008;17:279-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu G, Ades AE. Combination of direct and indirect evidence in mixed treatment comparisons. Stat Med 2004;23:3105-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jansen JP, Fleurence R, Devine B, Itzler R, Barrett A, Hawkins N, et al. Interpreting indirect treatment comparisons and network meta-analysis for health-care decision making: report of the ISPOR Task Force on Indirect Treatment Comparisons Good Research Practices: part 1. Value Health 2011;14:417-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donegan S, Williamson P, Gamble C, Tudur-Smith C. Indirect comparisons: a review of reporting and methodological quality. PLoS One 2010;5:e11054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song F, Loke YK, Walsh T, Glenny AM, Eastwood AJ, Altman DG. Methodological problems in the use of indirect comparisons for evaluating healthcare interventions: survey of published systematic reviews. BMJ 2009;338:b1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bafeta A, Trinquart L, Seror R, Ravaud P. Analysis of the systematic reviews process in reports of network meta-analyses: methodological systematic review. BMJ 2013;347:f3675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cipriani A, Higgins JP, Geddes JR, Salanti G. Conceptual and technical challenges in network meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2013;159:130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ades AE, Caldwell DM, Reken S, Welton NJ, Sutton AJ, Dias S. Evidence synthesis for decision making 7: a reviewer’s checklist. Med Decis Making 2013;33:679-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoaglin DC, Hawkins N, Jansen JP, Scott DA, Itzler R, Cappelleri JC, et al. Conducting indirect-treatment-comparison and network-meta-analysis studies: report of the ISPOR Task Force on Indirect Treatment Comparisons Good Research Practices: part 2. Value Health 2011;14:429-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edwards SJ, Clarke MJ, Wordsworth S, Borrill J. Indirect comparisons of treatments based on systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials. Int J Clin Pract 2009;63:841-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sobieraj DM, Cappelleri JC, Baker WL, Phung OJ, White CM, Coleman CI. Methods used to conduct and report Bayesian mixed treatment comparisons published in the medical literature: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abdelhamid AS, Loke YK, Parekh-Bhurke S, Chen YF, Sutton A, Eastwood A, et al. Use of indirect comparison methods in systematic reviews: a survey of Cochrane review authors. Research Synthesis Methods 2012;3:71-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song F, Altman DG, Glenny AM, Deeks JJ. Validity of indirect comparison for estimating efficacy of competing interventions: empirical evidence from published meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;326:472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thorlund K, Thabane L, Mills EJ. Modelling heterogeneity variances in multiple treatment comparison meta-analysis—are informative priors the better solution? BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donegan S, Williamson P, D’Alessandro U, Tudur Smith C. Assessing key assumptions of network meta-analysis: a review of methods. Research Synthesis Methods 2013;4:291-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ioannidis JP. Integration of evidence from multiple meta-analyses: a primer on umbrella reviews, treatment networks and multiple treatments meta-analyses. CMAJ 2009;181:488-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mills EJ, Thorlund K, Ioannidis JP. Demystifying trial networks and network meta-analysis. BMJ 2013;346:f2914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salanti G, Ades AE, Ioannidis JP. Graphical methods and numerical summaries for presenting results from multiple-treatment meta-analysis: an overview and tutorial. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:163-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lathyris DN, Patsopoulos NA, Salanti G, Ioannidis JP. Industry sponsorship and selection of comparators in randomized clinical trials. Eur J Clin Invest 2010;40:172-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Estellat C, Ravaud P. Lack of head-to-head trials and fair control arms: randomized controlled trials of biologic treatment for rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:237-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rizos EC, Salanti G, Kontoyiannis DP, Ioannidis JP. Homophily and co-occurrence patterns shape randomized trials agendas: illustration in antifungal agents. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:830-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stamatakis E, Weiler R, Ioannidis JP. Undue industry influences that distort healthcare research, strategy, expenditure and practice: a review. Eur J Clin Invest 2013;43:469-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thorlund K, Mills EJ. Sample size and power considerations in network meta-analysis. Syst Rev 2012;1:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trinquart L, Abbe A, Ravaud P. Impact of reporting bias in network meta-analysis of antidepressant placebo-controlled trials. PLoS One 2012;7:e35219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dias S, Welton NJ, Sutton AJ, Caldwell DM, Lu G, Ades AE. Evidence synthesis for decision making 4: inconsistency in networks of evidence based on randomized controlled trials. Med Decis Making 2013;33:641-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song F, Xiong T, Parekh-Bhurke S, Loke YK, Sutton AJ, Eastwood AJ, et al. Inconsistency between direct and indirect comparisons of competing interventions: meta-epidemiological study. BMJ 2011;343:d4909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Veroniki AA, Vasiliadis HS, Higgins JP, Salanti G. Evaluation of inconsistency in networks of interventions. Int J Epidemiol 2013;42:332-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Woodcock J, Brozek J, Helfand M, et al. GRADE guidelines: 8. Rating the quality of evidence-indirectness. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:1303-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song F, Harvey I, Lilford R. Adjusted indirect comparison may be less biased than direct comparison for evaluating new pharmaceutical interventions. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:455-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alkhafaji AA, Trinquart L, Baron G, Desvarieux M, Ravaud P. Impact of evergreening on patients and health insurance: a meta analysis and reimbursement cost analysis of citalopram/escitalopram antidepressants. BMC Med 2012;10:142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Madan J, Stevenson MD, Cooper KL, Ades AE, Whyte S, Akehurst R. Consistency between direct and indirect trial evidence: is direct evidence always more reliable? Value Health 2011;14:953-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Song F, Clark A, Bachmann MO, Maas J. Simulation evaluation of statistical properties of methods for indirect and mixed treatment comparisons. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012;12:138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coleman CI, Phung OJ, Cappelleri JC, Baker WL, Kluger J, White CM, et al. Use of mixed treatment comparisons in systematic reviews. AHRQ Publication No. 12-EHC119-EF. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2012 (available from www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/reports/final.cfm). [PubMed]

- 38.Tan SH, Bujkiewicz S, Sutton A, Dequen P, Cooper N. Presentational approaches used in the UK for reporting evidence synthesis using indirect and mixed treatment comparisons. J Health Serv Res Policy 2013;18:224-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.