Abstract

Nurses Improving Care of Healthsystem Elders (NICHE) provides hospitals with tools and resources to implement a geriatric initiative to improve health outcomes and experiences for older adults and their families. Beginning in 2011, members have engaged in a process of program self-evaluation, designed to evaluate internal progress toward developing, sustaining and disseminating NICHE. This manuscript describes the NICHE Site Self -evaluation and reports the inaugural self-evaluation data in 180 North American hospitals. NICHE members evaluate their program utilizing the following dimensions of a geriatric acute care program: guiding principles, organizational structures, leadership, geriatric staff competence, interdisciplinary resources and processes, patient- and family-centered approaches, environment of care, and quality metrics. The majority of NICHE sites were at the progressive implementation level (n= 100, 55.6%), having implemented interdisciplinary geriatric education and the geriatric resource nurse (GRN) model on at least one unit; 29% have implemented the GRN model on multiple units, including specialty areas. Bed size, teaching status, and Magnet® status were not associated with level of implementation, suggesting that NICHE implementation can be successful in a variety of settings and communities.

Keywords: acute care, models, older adults, program evaluation

Introduction

The hospital setting continues to play a pivotal role influencing the health and functional trajectories of older adults throughout the world. Multiple co-morbidities and the practice of polypharmacy increase the risk of exacerbations of chronic illness and the need for acute care interventions (Creditor, 1993). Additional baseline vulnerabilities, including age-related cognitive, functional, and physical impairment predispose hospitalized older adults to iatrogenic problems including delirium (Inoyue, 2006; Han et al., 2009), falls (Tinetti et al., 1995; Tinetti & Kumar, 2010), and pressure ulcers (Baumgarten et al., 2006; Cox, 2011). Additionally, they are at increased risk for functional decline (Gill et al., 2010; Covinsky et al., 2003; Covinsky et al. 2011; Wilson et al., 2012), cognitive loss (Makris et al., 2010), higher resource consumption, and higher rates of readmission (Jencks, 2009; U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics). There has been an increasing international awareness that a misalignment of the social, physical, and care environment with the complex needs of older adults may be responsible for many of the negative outcomes associated with hospitalization (Boltz et al., 2010, Brown et al., 2004, Brown et al., 2011; Parke & Chappel, 2010; Steinman & Hanlon, 2004; Zisberg et al., 2011). In response, acute care geriatric models of care have emerged, with the intention of promoting a better older person-hospital environment fit and improving the outcomes and experiences of hospitalization.

Literature Review

Models of Acute Geriatric Care

According to Hickman and colleagues (2007) an ideal model of care addresses the patient, provider and system issues related to the delivery of health care. Several geriatric acute care models have demonstrated improvements in clinical and organizational outcomes including decreased cost. They include interdisciplinary care provided in specialized units (Counsell et al., 2000; Conroy et al., 2011) or through mobile consultant teams (Conroy et al., 2011; Ellis et al., 2011; Farber et al., 2011) specialized assessment and multi-component interventions (Inouye et al., 1999), and programs of early discharge planning and transitional care (Naylor et al., 2004; Coleman et al., 2006). In addition, Nurses Improving Care for Healthsystem Elders (NICHE) hospitals have embedded infrastructures that support the development, evaluation and sustainability of a geriatric acute care initiative to promote the implementation and sustainability of evidence-based care (Boltz et al., 2008b; Leff et al., 2012).

NICHE as Infrastructure to Geriatric Initiatives

The goal of NICHE is to support a systemic, cross-disciplinary diffusion of knowledge and application of geriatric best practices into daily operations of the organization (Naylor, 2004). A program of New York University College of Nursing, NICHE is a membership organization comprised of 378 hospitals and their affiliate providers (long term care and home health care) of post-acute services who engage in active collaboration focused on continuing education, quality initiatives, and program evaluation. NICHE engages nursing staff at all levels. However, it is the support and guidance of executive nurses that is essential to the uptake and sustainability of the program (Capezuti et al., 2012). Foundational to NICHE is the Geriatric Resource Nurse (GRN) model wherein staff nurses are supported by an advanced nurse clinician to become unit based peer consultants and educators, and leaders of quality initiatives (NICHE, 2012). GRNs function in any unit that serves older adults, and are integral to the uptake and dissemination of evidence based practice (Boltz et al., 2008a).

NICHE members utilize project management tools and are guided through a leadership training program to develop the following infrastructure: an interdisciplinary, inter-departmental steering committee; a core gerontologic curriculum and learning resources that build clinical competency in all levels of staff; evidence – based clinical guidelines and complementary operational tools, and a comprehensive set of metrics (Turner et al., 2001; Boltz et al., 2008a; NICHE, 2012). This infrastructure supports the dissemination of educational and clinical initiatives, and promotes a “gerontologizing” of the hospital culture, wherein the needs of older adults are represented in broader hospital and outreach programs.

NICHE Measurement and Program Evaluation

The following quality metrics are associated with NICHE: evaluation of the “institutional milieu” surrounding care of older adults (staff knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of the care environment), using the Geriatric Institutional Assessment Profile (GIAP) (Fletcher et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2009; McKenzie et al., 2011) clinical measures (related to catheter associated urinary tract infections, pressure ulcers, falls and fall injuries, and restraint use); and measures of staffing volume and certification(Kim et al., 2007). In addition, since 2011, members have engaged in a process of biennial program self-evaluation, designed to evaluate internal progress toward developing, sustaining and disseminating a NICHE program. The purpose of this manuscript is to describe the NICHE Site Self-evaluation and to report the inaugural self-evaluation data.

Methods

Design

This retrospective, descriptive study used data extracted from the NICHE Site Self-evaluation. Data is submitted on a biennial basis as a part of a member’s recommitment and is used by hospitals in their internal planning and evaluation. In addition, the results inform resource development by NYU NICHE. The study was granted an exempt status from the New York University Committee on Activities Involving Human Subjects (NYUCIHS).

Sample

One hundred eighty (180) NICHE hospitals who conducted the self-evaluation between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2011 were included in the analysis. Those eligible for inclusion included the 215 sites that were designated NICHE hospitals for one year or more, scheduled to submit evaluation data for the year 2011. Thus, the response rate was 84%.

Measures

Hospital characteristics

Descriptive hospital information included teaching status (academic medical center, teaching hospital and non-teaching hospital), bed size (small=less than 200 beds, medium=200–400 beds, large=more than 400 beds), and Magnet® status (designated or not). External recognition, the presence of geriatric administrative units, specialized units, geriatric acute and non-acute programs were described. We also collected information on the utilization of the following acute care models: GRN, Acute Care of Elders {ACE} units, Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP), as well as transitional care models: Better Outcomes for Old Adults through Safe Transitions (BOOST), the Care Transitions Program, and the Transitional Care Model.

NICHE Program Self-evaluation instrument development

The NICHE Site Self-evaluation is a 49-item tool that measures the depth (degree of application of evidence-based resources) and penetration (dissemination throughout the hospital) of programs. The self-evaluation is submitted by the NICHE Coordinator via a web-based portal.

The content of the self-evaluation was developed in previous research that engaged the views of clinicians, consumers, and gerontologic researchers to identify the components of a geriatric acute care program (Boltz, Capezuti, & Shabbat, 2010). That study yielded dimensions or components of a systemic program aimed at improving care of hospitalized older adults: guiding principles, organizational structures, leadership, resources to build geriatric staff competence, interdisciplinary resources and processes, patient and family centered approaches, environment of care, and aging sensitive practices. Dimensions were associated with 113 items, or activities associated with program development, implementation, and evaluation.

The NICHE research team at NYU College of Nursing engaged a team of content experts, (NICHE administrators, gerontologic/geriatric researchers, and clinicians) to review the dimensions along with associated items to determine their usefulness in the NICHE program and establish content validity. It was decided that the dimensions were aligned conceptually with the established NICHE principles of 1) evidence based, geriatric care at the bedside, 2) patient/family centered environments, 3) healthy and productive practice environment, and 4) multi-dimensional metrics of quality. The 113 items were closely examined; 49 items were extracted from this list, identified as salient “action items” that were relevant to NICHE implementation, useful for sites to self-evaluate NICHE progress.

Through an iterative process, the group refined the items and came to consensus to create a draft self-evaluation instrument. The content experts reviewed the items, graded them on a scale of 1–4 for level of complexity (with four as highest) and established a scoring system to calculate four levels of implementation. The content experts used the NICHE Implementation Planning and Implementation Manual (NICHE, 2012) to guide the evaluation of items. The items range from activities associated with early stage implementation (e.g., designating a NICHE Implementation Team) to more complex activities (engaging in national activities such as publishing program results). Fourteen items each were determined to be associated with the following phases: 1) early phase, 2) progressive, and 3) senior friendly. Seven items were classified as “exemplar” (score 4). Accordingly, the experts agreed that the sum of items result in the following implementation levels, described with associated items:

early implementation level: developing infrastructure: oversight, leadership, staff development and evaluation (score 0–13)

progressive level: comprehensive geriatric acute care model, including the GRN model, implemented on at least one unit (score 14–27)

senior friendly level: geriatric initiatives on multiple units; has assumed a regional leadership role (score 28–41)

exemplar level: geriatric initiative throughout and beyond the organization and national leadership role (score 42–49).

Analysis

Descriptive statistics for the hospital sample were examined. Self-evaluation items were subjected to calculations of reliability estimates, using coefficient alpha. The levels of implementation were calculated for each hospital in the sample and the frequency per level reported. The resultant levels of implementation were examined, using chi-square test for independence, to determine if there was a relationship between levels and hospital characteristics.

Results

Sample Characteristics

As shown in Table 1, the majority of sites are US acute care, medium sized teaching hospitals that have a comprehensive geriatric assessment program, a dementia evaluation program, geriatric primary care, and an affiliation with home health and some form of hospice. Forty percent (n=72) of the hospitals have Magnet® designation. All sites maintain a not-for-profit status. Table 2 shows that 76% have a geriatric resource nurse model, with 45.0 GRNs on average (± 88.6), present on 4.4 units on average (±6.1) in the hospital. The average number of nurses reported national certification in gerontological nursing g is 8.4 (± 22.5).

Table 1.

Profile of hospital participants (N=180)

| n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Hospital Type

| ||

| US Acute Care Hospital | 166 (92.2) | |

| Canadian Acute Care Hospital | 14 (7.8) | |

| Bed Size | ||

| Small (0–200) | 51 (28.3) | |

| Medium (201–400) | 70 (38.9) | |

| Large (400+) | 59 (32.8) | |

| Teaching Status | ||

| Academic Medical Center | 38 (21.1) | |

| Teaching | 76 (42.2) | |

| Non-teaching | 66 (36.7) | |

| External recognition | ||

| Magnet®† | 72 (40.0) | |

| Baldridge ‡ | 9 (5.0) | |

| AARP § | 6 (3.3) | |

| Administrative units | ||

| Hospital-wide geriatric administrative units? | 27 (15.0) | |

| Geriatric Service Line | 57 (31.7) | |

| Geriatric medical department | 60 (33.3) | |

| Specialized units | ||

| Gero-psych unit | 37 (20.6) | |

| Dementia unit | 9 (5.0) | |

| Hospice unit | 35 (19.4) | |

| Geriatric Emergency Department | 12 (6.7) | |

| Geriatric Acute Care Programs | ||

| Comprehensive geriatric assessment | 104 (57.8) | |

| Mobile ACE (Acute Care of Elderly) | 20 (11.1) | |

| Palliative care | 42 (23.3) | |

| Transitional care | 79 (43.9) | |

| Non-acute programs | ||

| Senior membership program | 43 (23.9) | |

| Comprehensive geriatric assessment | 87 (48.3) | |

| Dementia evaluation program | 103 (55.4) | |

| Geriatric primary care | 101 (56.1) | |

| Non-acute affiliations | ||

| Sub-acute care | 66 (36.7) | |

| Long term nursing home care | 41 (22.8) | |

| Assisted living | 28 (15.6) | |

| Home health | 110 (61.1) | |

| In-patient hospice care | 102 (57.3) | |

| Home hospice care | 86 (47.8) | |

| Adult day care | 30 (16.7) | |

The Magnet Recognition Program® “recognizes health care organizations for quality patient care, nursing excellence and innovations in professional nursing practice” (http://www.nursecredentialing.com/Magnet/ProgramOverview.aspx).

The Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award is given to organizations that have demonstrated an “outstanding system for managing its products, services, human resources, and customer relationships. As part of the evaluation, an organization is asked to describe its system for assuring the quality of its goods and services. It also must supply information on quality improvement and customer engagement efforts and results” (http://www.nist.gov/baldrige/).

The AARP Best Employers for Workers over 50 program,”cosponsored by the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM), awards businesses and organizations that have implemented new and innovative policies and best practices in talent management. These organizations are creating road maps for others on how to attract and retain top talent in today’s multigenerational workforce” (http://www.aarp.org/work/employee-benefits/best_employers/).

Table 2.

Model Utilization (N=180)

| n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Geriatric Resource Nurse (GRN) Model † | 137 (76.1)

|

|

| Mean ± SD (mini-max)

|

||

| Number of GRNs | 45.0 ± 88.6 (0–80) | |

| Number of units with GRNs | 4.4 ± 6.1 (0–41) | |

| Number of nurses certified in geriatrics | 8.4 ± 22.5 (0–195) | |

|

| ||

| Acute Care of Elders (ACE) unit ‡ | 49 (27.2) | |

|

| ||

| Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP) § | 15 (8.3) | |

|

| ||

| Better Outcomes for Old Adults through Safe Transitions (BOOST) ± | 21 (11.7) | |

|

| ||

| The Care Transitions Program (Coleman model)1 | 22 (12.2) | |

|

| ||

| Transitional Care Model (Naylor model)δ | 8 (4.4) | |

Geriatric Resource Nurse (GRN) Model: bedside nurses receive gerontologic training and serve as peer consultants and change agents http://www.nicheprogram.org/

Acute Care of Elders (ACE) unit: specially – prepared environments that utilize evidence-based protocols implemented by interdisciplinary teams

Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP): interdisciplinary staff, volunteers, and targeted intervention protocols to improve patients’ outcomes (delirium and functional decline) and provide cost-effective care http://www.hebrewseniorlife.org/research-abc-hospital-elder-life-program-help

Better Outcomes for Old Adults through Safe Transitions (BOOST): hospitalist-led program that identify high-risk patients on admission and target risk-specific interventions to prevent readmissions and improve outcomes http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Home&TEMPLATE=/CM/HTMLDisplay.cfm&CONTENTID=27659

The Care Transitions Program (Coleman model): patients with complex care needs and family caregivers work with a “Transition Coach” and learn self-management skills that will ease their transition from hospital to home http://www.caretransitions.org/

Transitional Care Model (Naylor model): comprehensive in-hospital planning and home follow-up for chronically ill high-risk older adults http://www.transitionalcare.info/

Internal consistency of items

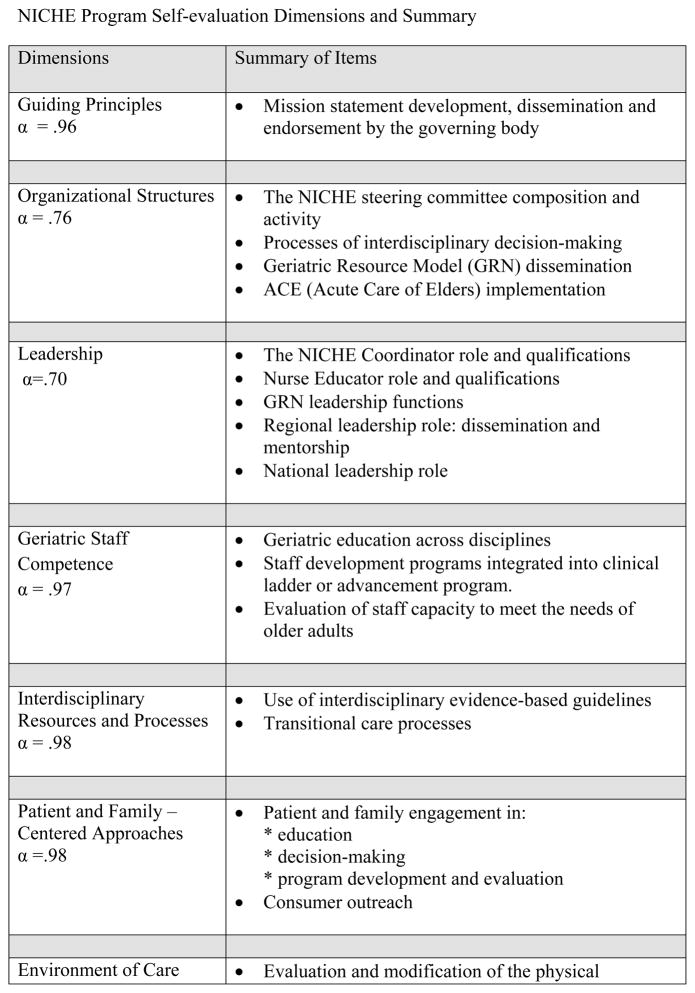

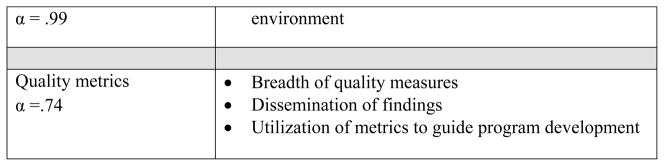

An internal consistency estimate using coefficient alpha resulted in a slight modification of the instrument. The aging sensitive practices dimension was eliminated when the two associated items were re-categorized into other dimensions. Additionally, “quality metrics” was added as a dimension. The final 8 dimensions and associated 49 items demonstrate good internal to excellent consistency (α=.70–.98). Items are designated according to level of complexity (level 1–4); independent of the complexity level, the 49 items are scored yes = 1; 0=no, with a possible total score of 0 to 49. Figure 1 shows the dimensions and a summary of item content.

Figure 1.

NICHE Program Self-evaluation Dimensions and Summary

NICHE Level of Implementation

As shown in Table 3, 15.6% (n=28) of the sites were early implementers, i.e., they had identified a coordinator, developed a steering committee with representation from nursing management, quality management, staff education, and clinical management, and created a mission statement and a two year action plan. The majority of NICHE sites were at the progressive implementation level (n= 100, 55.6%), having implemented interdisciplinary geriatric education and the GRN model on at least one unit. Senior friendly implementers (n=45, 25.0%) have engaged community based providers and consumers in their steering committees and expanded the GRN model to multiple units, including specialty areas. This cohort is also characterized by policies that promote patient/family engagement in decision making, and a robust set of measures to evaluate program effectiveness. Finally, the exemplar sites (n= 7, 3.9%) have implemented the GRN model and geriatric training of nursing assistants on all units serving older adults, addressed the physical environment in their program planning and evaluation, and assumed a national leadership role by providing mentorship to other sites and supporting the development and dissemination of NICHE resources.

Table 3.

NICHE Self-evaluation levels (N=180)

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Early implementation | 28 (15.6) |

| Progressive implementation | 104 (57.8) |

| Senior-friendly implementation | 42 (23.3) |

| Exemplar implementation | 6 (3.3) |

Upon examining the relationship between hospital characteristics and level of implementation, we found that bed size, teaching status, and Magnet® status were not associated with level of implementation. The presence of an ACE unit (p=.021), mobile ACE unit (p= .022), and a comprehensive geriatric assessment programs, both inpatient (p=0.029) and outpatient (p=.008) were more likely to be senior friendly implementers as opposed to early or progressive implementers.

The seven exemplar sites were examined by teaching status, size, geriatric administrative units, and use of other models. The following is a summary:

Five are teaching hospitals and two are non-teaching sites. (None are academic medical centers).

Bed size is represented as follows: one small, four medium, and two large hospitals.

Four hospitals have a comprehensive geriatric evaluation program.

Three hospitals have ACE units.

Five of the seven hospitals have a formal transitional care program (BOOST, Care Transitions Program, or the Transitional Care Model); two hospitals have blended implementation of more than one transitional model.

Three hospitals have Magnet® designation.

Discussion

The NICHE self-evaluation process provides sites with the opportunity to create a blueprint for growth and sustainability of their geriatric acute care program. Although the sample in this biennial survey is comprised of approximately 50% of the total NICHE sites, it represents hospitals with structural characteristics (bed size and teaching status) of NICHE sites as a whole. The high percentage of sites utilizing the GRN model and uptake of this model in multiple units underscore the capacity of this model to be disseminated and sustained (Turner et al., 2001).

The results show that a little more than half of the sites are in the progressive stage of implementation, with other sites dispersed over the other three levels, demonstrating the need to support sites at varying stages of program development. The NICHE faculty at NYU supports diversity in the degree of program maturity through several programmatic approaches. Fledgling sites are mentored by sites with well-developed programs. Sites that are in the progressive stage of implementation are supported through discussion boards and regularly scheduled educational webinars. Senior-friendly and exemplar initiatives are frequently shared at regional and national conferences, and in NICHE publications. The successes of sites at various levels are acknowledged at the annual conference and profiled on the NICHE website, which helps members sustain their internal administrative support.

The evaluation of this preliminary self-evaluation data indicates that hospital size and teaching status is not a factor influencing level of implementation. We did not evaluate financial parameters however, such as payer mix and profit margins, an area for future exploration. An understanding of these indices would support the development of resources and strategies for senior programs in hospitals that are financially challenged. Additionally, the influence of geographic features including rurality upon program development and dissemination is an area for future investigation.

Findings indicate that hospitals that have ACE programs and comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) programs also have higher levels of NICHE implementation, not a surprising finding. Acute care environments that foster interdisciplinary collaboration and the clinical leadership of geriatric specialists are associated with enhanced uptake of aging sensitive principles (Boltz et al., 2008a; Ellis et al., 2011). Nonetheless, there are high performing NICHE hospitals that do not have access to geriatric medical specialists. Further exploration of the influence of these services as well as the alternative approaches upon systemic NICHE uptake is warranted.

Limitations

The study included NICHE sites only; thus results are not generalizable to non-NICHE sites. Also, the NICHE Site Self-evaluation tool, and consequently this study, did not evaluate salient measures of quality including clinical and financial outcomes related to care of hospitalized older adults, an area for future investigation.

Implications for Practice and Research

As key caregivers in hospitals, nurses significantly influence the quality of care provided and ultimately, patient, family, and organizational outcomes. Their central role positions them to lead interdisciplinary teams in the development and evaluation of system-wide programs designed to improve care of older adult patients and their families. The NICHE Site Self-evaluation tool may be used to chart a plan toward improving the clinical and organizational culture related to care of older adults, and evaluate progress on an ongoing basis. The structures and processes associated with the eight dimensions of the self-evaluation, which are relevant for NICHE and non-NICHE sites alike, can be triangulated with clinical outcomes and other measures of quality to facilitate a robust set of indicators to guide quality improvement activity. Future research that examines the association of self-evaluation dimensions as well as program “dose” (e.g., the number of geriatric resource nurses or quantity of staff training) with patient and organizational outcomes will yield decision-support tools for organizations to use when prioritizing elder care initiatives.

Conclusion

The ever increasing number of older adults and the growing societal imperative to improve quality represent compelling reasons for hospitals to upgrade their care delivery to older adults. An essential component of acute geriatric care model is evaluation, including assessing the uptake and dissemination of aging specific knowledge and standards, the goal of the NICHE program. The NICHE Site Self-evaluation provides a mechanism to chart and track progress toward this goal. Preliminary findings utilizing this process indicate that NICHE implementation can be successful in a variety of settings.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Boltz’s work was supported by Grant UL1 TR000038 from the National Center for the Advancement of Translational Science (NCATS), National Institutes of Health; Dr. Galvin by P30 AG008051 (NIA NIH HHS)

Footnotes

Contributions

Study Design: MB

Data Collection and Analysis: MB, EC, JS, JB, DC, SC, SD, RL, DL, SN, TS

Manuscript Writing: MB, EC, JS, JB, DC, SC, SD, RL, DL, SN, TS, JG

References

- Baumgarten M, Margolis D, Localio A, et al. Pressure ulcers among elderly patients early in the hospital stay. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:749–54. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.7.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boltz M, Capezuti E, Bowar-Ferres S, et al. Hospital nurses’ perceptions of the geriatric care environment. J Nurs Scholarship. 2008a;40(3):282–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2008.00239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boltz M, Capezuti E, Bower-Ferres S, et al. Changes in the geriatric care environment associated with NICHE. Geriatr Nurs. 2008b;29(3):176–185. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boltz M, Capezuti E, Kim H, Fairchild S, Secic M. Test-retest reliability of the GIAP (Geriatric Institutional Assessment Profile) Clin Nurs Res. 2009;18:242–252. doi: 10.1177/1054773809338555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boltz M, Capezuti E, Shabbat N. Building a framework for a geriatric acute care model. Leadersh Health Serv. 2010;23:334–360. [Google Scholar]

- Boltz M, Capezuti E, Shabbat N, Hall K. Going home better not worse: Older adults’ views on physical function during hospitalization. Int J Nurs Pract. 2010;16:381–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2010.01855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boltz M, Capezuti E, Shabbat N. Nursing staff perceptions of physical function in hospitalized older adults. Appl Nurs Res. 2011;24:215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CJ, Friedkin RJ, Inouye SK. Prevalence and outcomes of low mobility in hospitalized older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1263–1270. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capezuti E, Boltz E, Cline D, et al. NICHE – A model for optimizing the geriatric nursing practice environment. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04259.x. JCN-2011-0599.R2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min S. The care transitions intervention. Arch Int Med. 2006;166:1822–1828. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conroy SP, Stevens T, Parker SG, Gladman JR. A systematic review of comprehensive geriatric assessment to improve outcomes for frail older people being rapidly discharged from acute hospital: ‘interface geriatrics’. Age and Aging. 2011;40:436–443. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afr060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Counsell SR, Holder CM, Liebenauer LL, et al. Effects of a multicomponent intervention on functional outcomes and process of care in hospitalized older adults: A randomized controlled trial of Acute Care for Elders (ACE) in a community hospital. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1572–1581. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, et al. Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illness: Increased vulnerability with age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:451–458. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covinsky KE, Pierluissi E, Johnston CB. Hospitalization-Associated Disability. JAMA. 2011;306:1782–1793. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J. Predictors of pressure ulcers in adult critical care patients. Am J Crit Care. 2011;26:364–74. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2011934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creditor MC. Hazards of hospitalization of the elderly. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:219–223. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-3-199302010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis G, Whitehead MA, O’Neill D, Langhorne P, Robinson D. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital. BMJ. 2011;343:d6553. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d6553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farber JI, Korc-Grodzicki B, Du Q, Leipzig RM, Siu AL. Operational and quality outcomes of a mobile acute care for the elderly service. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:358–63. doi: 10.1002/jhm.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher K, Hawkes P, Williams-Rosenthal S, Mariscal CS, Cox BA. Using nurse practitioners to implement best practice care for the elderly during hospitalization: The NICHE journey at the University of Virginia Medical Center. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2007;19:321–337. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill TM, Allore HG, Gahbauer EA, Murphy TE. Change in disability after hospitalization or restricted activity in older persons. JAMA. 2010;304:1919– 1928. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goode PS, Burgio KL, Richter HE, Markland AD. Incontinence in older women. JAMA. 2010;303:2172–2181. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JH, Zimmerman EE, Cutler N, et al. Delirium in older emergency department patients: recognition, risk factors, and psychomotor subtypes. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;16:193–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00339.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman L, Newton P, Halcomb EJ, Chang E, Davidson P. Best practice interventions to improve the management of older people in acute care settings: a literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2007;60:113–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye SK, Bogardus ST, Baker DI, Leo-Summers L, Cooney LM. The Hospital Elder Life Program: a model of care to prevent cognitive and functional decline in older hospitalized patients Hospital Elder Life Program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1697–706. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoyue SK. Delirium in older persons. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1157–1165. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among Patients in the Medicare Fee-for-Service Program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1418–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Capezuti E, Boltz M, Fairchild S, Fulmer T, Mezey M. Factor structure of the geriatric care environment scale. Nurs Res. 2007;56:339–347. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000289500.37661.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leff B, Spragens LH, Morano B, et al. Rapid reengineering of acute medical care for Medicare beneficiaries: the Medicare innovations collaborative. Health Aff. 2012;31:1204–1215. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makris N, Dulhunty JM, Paratz JD, et al. Unplanned early readmission to the intensive care unit: a case-control study of patient, intensive care and ward-related factors. Anesth Intensive Care. 2010;38:723–31. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1003800338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie LJA, Blandford AA, Menec VH, Boltz M, Capezuti E. Hospital nurses’ perceptions of the geriatric care environment in one Canadian health care region. JNurs Scholarship. 2011;43:181–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2011.01387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor MD, Brooten DA, Campbell RL, Maislin G, McCauley KM, Schwartz JS. Transitional care of older adults hospitalized with heart failure: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:675–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICHE. NICHE Home. 2013 Available at: http://www.nicheprogram.org/ [March, 20 2013]

- Parke B, Chappel NL. Transactions between older people and the hospital environment: A social ecological analysis. J of Aging Stud. 2010;24:115–124. [Google Scholar]

- Steinman MA, Hanlon JT. Managing medications in clinically complex elders: “There’s got to be a happy medium”. JAMA. 2004;304:1592–1601. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinetti ME, Inouye SK, Gill TM, Doucette JT. Shared risk factors for falls, incontinence, and functional dependence: Unifying the approach to geriatric syndromes. JAMA. 1995;273:1348–1353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinetti ME, Kumar C. The patient who falls: “it’s always a trade-off”. JAMA. 2010;303:258–266. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JT, Lee V, Fletcher K, Hudson K, Barton D. Measuring quality of care with an inpatient elderly population: The Geriatric resource nurse model. J Gerontological Nurs. 2001;27:8–18. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20010301-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Labor. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index All Urban Consumers (CPI-U), US city average. http://www.bls.gov/cpi/#data [March 20, 2013]

- Wilson RS, Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Dong X, Leurgens SE, Evans DA. Cognitive decline after hospitalization in a community population of older persons. Neurology. 2012;78 (13):950–6. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31824d5894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zisberg A, Shadmi E, Sinoff G, Gur-Yaish N, Srulovici E, Admi H. Low mobility during hospitalization and functional decline in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:266–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]