Abstract

Background: The incidence of thyroid cancer has increased at an alarming rate in both men and women in the United States. The etiology of this epidemic is unclear. We tested the hypothesis that a significant component of this epidemic is due to increased detection of occult disease. We examined whether the density of endocrinologists and general surgeons as well as employment of cervical ultrasonography were factors associated with this epidemic.

Methods: Thyroid cancer incidence rates by states were obtained from the United States Cancer Statistics 1999–2009 reported by the National Program of Cancer Registries. The densities of endocrinologists and general surgeons and the employment of cervical ultrasonography were calculated on a statewide basis and correlated with the incidence of thyroid cancer.

Results: Age-standardized incidence rates of thyroid cancer have increased in every state in the United States. Significant regional variations were noted, with the highest incidence rates in the northeast and the lowest in the south. The incidence rates were significantly correlated with the density of endocrinologists (r=0.58, p<0.0001 for males; r=0.44, p=0.0031 for females) and the employment of cervical ultrasonography (r=0.40, p=0.0091 for males; r=0.36, p=0.0197 for females). Both the density of endocrinologists and general surgeons and employment of cervical ultrasonography could explain 57% of the variability in state-level incidence for males and 49% for females.

Conclusions: These data offer evidence to suggest that the epidemic of thyroid cancer is due to increased detection of a reservoir of previously occult disease. The increased detection of thyroid cancer results in therapeutic interventions including surgery and radioactive thyroid treatment that may be of limited benefit.

Introduction

Over the past decade, the incidence of thyroid cancer has increased at an alarming rate, and thyroid cancer is now the fifth most common cancer in women in the United States (1). In spite of this striking incidence increase in both men and women, the mortality rate for thyroid cancer has not changed. There are three plausible explanations: (i) a real increase in disease has occurred due to environmental factors; (ii) the apparent epidemic is due to increased detection of the disease due to enhanced screening; or (iii) a combination of these events.

It has been suggested that the increasing incidence of thyroid cancer in the United States was predominantly due to the increased detection of subclinical disease, not an increase in the true occurrence of thyroid cancer, because the vast majority of cases were small tumors and the mortality of the disease remained stable (2). A recent ecologic study using the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) data indicated that higher levels of healthcare access are associated with higher papillary thyroid cancer rates, which provided supportive evidence for the overdiagnosis of thyroid cancer (3). However, other studies offered divergent opinions (4,5). The study based on the Department of Defense's Automated Central Tumor Registry found that the age-adjusted incidence rate of thyroid cancer in the military was significantly higher than the general population, and the rates varied by military service branch, suggesting that heightened medical surveillance does not appear to explain the temporal increase in thyroid cancer incidence fully (4). Nonetheless, the results of this study are consistent with overdiagnosis.

To examine further the hypothesis ascribing that the epidemic of thyroid cancer is due to increased detection, we analyzed data from the United States Cancer Statistics 1999–2009 to study the incidence variation across the United States and to ascertain whether the variation could be explained by the density of endocrinologists or general surgeons and employment of cervical ultrasonography in a given region.

Materials and Methods

To examine the secular trends and variation in the incidence of thyroid cancer statewide, age-standardized incidence rates and confidence intervals (CIs) were obtained from the United States Cancer Statistics (USCS) from 1999–2009, as reported by the National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) (6). All rates were age adjusted to the 2000 U.S. population. The number of endocrinologists and general surgeons in each state was obtained from the LifeScript Doctor Review (7). The LifeScript Doctor Review includes more than 720,000 doctors nationwide, which represents about 75% of the total number of U.S. doctors. The densities of endocrinologists, general surgeons, and primary care physicians by state were calculated as the number of members per 100,000 population in each state. Data on neck ultrasonography came from the retrospective administrative patient claims data affiliated with OptumInsight (8). OptumInsight includes data from United Health Group (UHG) and non-UHG plans, and the individuals covered by these health plans (approximately 32 million annual lives in 2010) are geographically diverse across the United States. The plans provide fully insured coverage for professional (e.g., physician), facility (e.g., hospital), and outpatient prescription medication services. The frequencies of neck ultrasonography in 2000–2011 were expressed as the counts of neck ultrasonography per 100,000 insured individuals for each state. This was a retrospective cohort analysis, and no identifiable protected health information was extracted or accessed during the course of the study. The study protocols are compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

States (n=37) that had incidence data for the entire time period 1999–2009 were included for trend analysis. Trends in age-adjusted incidence rates were examined for males and females combined and separately. The annual percentage change in thyroid cancer rates between 1999 and 2009 was calculated for each state to show the relative change in incidence for overall population and male and female separately. Incidence rates of thyroid cancer for the states (n=43) that have populations of more than one million were presented for the time period 2005–2009. Pearson correlation was used to assess the linear correlation between thyroid cancer incidence rates and the densities of endocrinologists, general surgeons, and primary care physicians, as well as the frequencies of neck ultrasonography and thyroid biopsy. Overall strength of the association was determined by a generalized least-squares regression model weighted by state population through calculating the overall R2 of the model. Median household income by state in 2011 inflation-adjusted dollars, obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau population survey annual social and economic supplements (9), was also included in the final model. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS software (v9.3, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

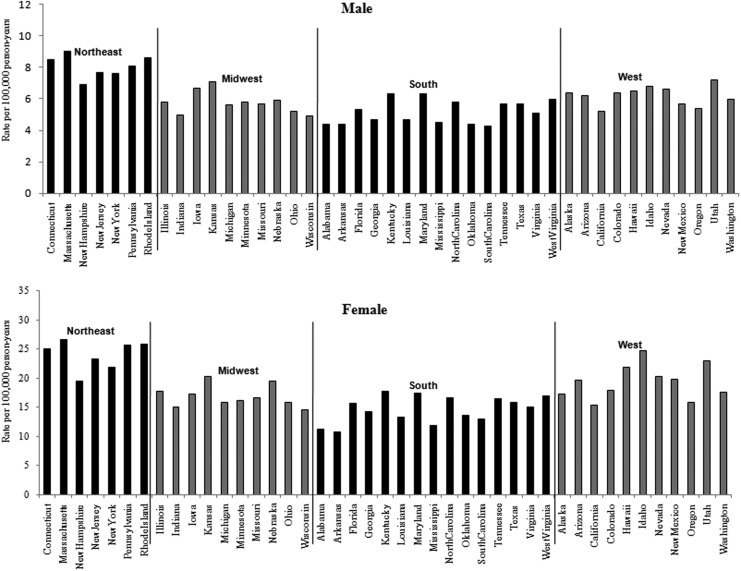

Thyroid cancer incidence rates in the United States are depicted in Table 1 and Figure 1 for both sexes combined and separately on a statewide basis (6). The greatest annual increase of age-adjusted incidence rate of thyroid cancer from 1999 to 2009 was 20.6% for females and 16.5% for males respectively. Although there was an increased incidence in every state, the pattern is neither random nor uniform. To analyze regional variations, thyroid cancer incidence rates between 2005 and 2009 are presented in Figure 2. The range was 2.5 times comparing the lowest incidence state (Arkansas) to the highest (Massachusetts) in females, and 2.1 times comparing the lowest (South Carolina) to the highest (Massachusetts) in males. The pattern for both sexes demonstrated that in the northeast the incidence was highest, whereas in the south the lowest incidence was observed.

Table 1.

National Geographic Variation in Thyroid Cancer Incidence Rates, 1999–2009

| 1999 | 2009 | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Both | Female | Male | Both | Female | Male | Annual % change | |||||||||

| States | Rate | CI | Rate | CI | Rate | CI | Rate | CI | Rate | CI | Rate | CI | Both | Female | Male |

| Northeast | |||||||||||||||

| Connecticut | 7.4 | 6.5–8.4 | 10.6 | 9.1–12.2 | 4.0 | 3.1–5.1 | 19.3 | 17.9–20.8 | 28.4 | 26.0–31.0 | 9.7 | 8.3–11.3 | 16.1 | 16.8 | 14.3 |

| Massachusetts | 7.3 | 6.7–8.0 | 10.7 | 9.6–11.8 | 3.8 | 3.2–4.6 | 19.5 | 18.5–20.6 | 28.7 | 27.0–30.6 | 9.9 | 8.8–11.0 | 16.7 | 16.8 | 16.1 |

| New Hampshire | 5.8 | 4.5–7.3 | 7.2 | 5.3–9.7 | 4.4 | 2.9–6.5 | 11.9 | 10.1–13.9 | 15.9 | 13.0–19.2 | 8.1 | 6.1–10.5 | 10.5 | 12.1 | 8.4 |

| New York | 8.0 | 7.6–8.4 | 11.6 | 11.0–12.3 | 4.0 | 3.6–4.5 | 17.5 | 16.9–18.1 | 25.6 | 24.6–26.6 | 8.9 | 8.3–9.6 | 11.9 | 12.1 | 12.3 |

| New Jersey | 7.7 | 7.1–8.3 | 10.9 | 10.0–12.0 | 4.2 | 3.6–4.9 | 18.4 | 17.5–19.3 | 27.8 | 26.3–29.4 | 8.8 | 7.9–9.7 | 13.9 | 15.5 | 11.0 |

| Pennsylvania | 8.6 | 8.1–9.1 | 12.5 | 11.7–13.4 | 4.4 | 3.9–5.0 | 20.0 | 19.2–20.7 | 29.8 | 28.5–31.2 | 9.8 | 9.1–10.6 | 13.3 | 13.8 | 12.3 |

| Rhode Island | 9.1 | 7.4–11.1 | 14.6 | 11.5–18.1 | 3.4 | 2.0–5.4 | 21.8 | 19.0–24.8 | 33.5 | 28.7–38.8 | 9.3 | 6.9–12.2 | 14.0 | 12.9 | 17.4 |

| Midwest | |||||||||||||||

| Illinois | 7.1 | 6.6–7.6 | 10.2 | 9.5–11.1 | 3.8 | 3.3–4.4 | 13.2 | 12.5–13.8 | 20.0 | 19.0–21.1 | 6.2 | 5.5–6.8 | 8.6 | 9.6 | 6.3 |

| Indiana | 5.7 | 5.1–6.4 | 8.1 | 7.2–9.2 | 3.3 | 2.7–4.1 | 10.3 | 9.6–11.1 | 15.4 | 14.0–16.8 | 5.2 | 4.4–6.1 | 8.1 | 9.0 | 5.8 |

| Iowa | 7.5 | 6.5–8.6 | 10.6 | 9.0–12.4 | 4.3 | 3.2–5.5 | 15.6 | 14.2–17.1 | 22.8 | 20.4–25.4 | 8.4 | 6.9–10.0 | 10.8 | 11.5 | 9.5 |

| Kansas | 7.7 | 6.7–8.8 | 10.9 | 9.2–12.8 | 4.4 | 3.3–5.7 | 15.2 | 13.8–16.8 | 22.5 | 20.0–25.2 | 7.9 | 6.5–9.5 | 9.7 | 10.6 | 8.0 |

| Michigan | 7.1 | 6.5–7.6 | 10.5 | 9.6–11.5 | 3.4 | 2.9–4.0 | 12.3 | 11.6–13.0 | 18.1 | 16.9–19.3 | 6.3 | 5.6–7.0 | 7.3 | 7.2 | 8.5 |

| Minnesota | 6.7 | 5.9–7.4 | 9.5 | 8.3–10.8 | 3.9 | 3.1–4.8 | 12.1 | 11.1–13.0 | 18.4 | 16.8–20.2 | 5.8 | 5.0–6.9 | 8.1 | 9.4 | 4.9 |

| Missouri | 6.9 | 6.3–7.7 | 10.1 | 9.0–11.4 | 3.5 | 2.8–4.3 | 12.5 | 11.6–13.4 | 18.6 | 17.1–20.2 | 6.1 | 5.2–7.0 | 8.1 | 8.4 | 7.4 |

| Nebraska | 6.4 | 5.2–7.7 | 9.5 | 7.6–11.9 | 3.1 | 2.0–4.6 | 14.2 | 12.5–16.1 | 22.6 | 19.6–26.0 | 5.9 | 4.5–7.8 | 12.2 | 13.8 | 9.0 |

| Ohio | 5.7 | 5.3–6.2 | 7.9 | 7.2–8.7 | 3.4 | 2.9–3.9 | 11.9 | 11.3–12.5 | 17.6 | 16.5–18.7 | 6.0 | 5.4–6.7 | 10.9 | 12.3 | 7.6 |

| South | |||||||||||||||

| Alabama | 5.8 | 5.1–6.6 | 8.3 | 7.1–9.5 | 3.3 | 2.5–4.2 | 8.2 | 7.4–9.1 | 11.2 | 9.9–12.6 | 5.1 | 4.2–6.1 | 4.1 | 3.5 | 5.5 |

| Florida | 6.2 | 5.9–6.6 | 9.0 | 8.4–9.7 | 3.4 | 3.0–3.8 | 11.5 | 11.1–12.0 | 17.3 | 16.5–18.2 | 5.7 | 5.2–6.1 | 8.5 | 9.2 | 6.8 |

| Georgia | 5.4 | 4.9–6.0 | 7.9 | 7.0–8.8 | 3.0 | 2.4–3.6 | 10.5 | 9.8–11.1 | 15.5 | 14.4–16.6 | 5.2 | 4.6–6.0 | 9.4 | 9.6 | 7.3 |

| Kentucky | 6.8 | 6.0–7.6 | 10.1 | 8.8–11.6 | 3.2 | 2.4–4.1 | 13.3 | 12.2–14.4 | 19.2 | 17.4–21.1 | 7.1 | 6.0–8.4 | 9.6 | 9.0 | 12.2 |

| Louisiana | 5.4 | 4.7–6.2 | 7.5 | 6.4–8.7 | 3.1 | 2.4–4.0 | 10.2 | 9.3–11.2 | 15.0 | 13.4–16.6 | 5.1 | 4.2–6.2 | 8.9 | 10.0 | 6.5 |

| Maryland | 7.3 | 6.5–8.0 | 11.0 | 9.8–12.3 | 3.2 | 2.5–4.0 | 12.8 | 11.9–13.8 | 18.5 | 17.0–20.1 | 6.6 | 5.7–7.7 | 7.5 | 6.8 | 10.6 |

| Oklahoma | 4.7 | 4.0–5.5 | 6.8 | 5.6–8.1 | 2.8 | 2.0–3.8 | 10.1 | 9.1–11.1 | 15.3 | 13.5–17.2 | 4.7 | 3.7–5.8 | 11.5 | 12.5 | 6.8 |

| South Carolina | 5.2 | 4.5–6.0 | 7.3 | 6.2–8.6 | 2.9 | 2.2–3.8 | 9.6 | 8.7–10.5 | 13.8 | 12.3–15.3 | 5.1 | 4.2–6.2 | 8.5 | 8.9 | 7.6 |

| Texas | 6.5 | 6.2–6.9 | 9.1 | 8.5–9.7 | 4.0 | 3.6–4.4 | 11.9 | 11.4–12.3 | 17.3 | 16.5–18.0 | 6.4 | 5.9–6.9 | 8.3 | 9.0 | 6.0 |

| West Virginia | 7.6 | 6.4–8.9 | 11.3 | 9.3–13.7 | 3.5 | 2.4–5.0 | 11.7 | 10.2–13.4 | 17.4 | 14.9–20.3 | 5.8 | 4.4–7.5 | 5.4 | 5.4 | 6.6 |

| West | |||||||||||||||

| Alaska | 8.7 | 6.4–11.7 | 10.5 | 7.1–15.2 | 7.2 | 4.1–11.8 | 12.7 | 10.1–15.8 | 17.5 | 13.2–22.7 | 8.3 | 5.5–12.2 | 4.6 | 6.6 | 1.5 |

| Arizona | 6.7 | 6.0–7.5 | 9.6 | 8.5–11.0 | 3.8 | 3.0–4.7 | 14.2 | 13.3–15.2 | 22.1 | 20.5–23.8 | 6.4 | 5.6–7.4 | 11.2 | 13.0 | 6.8 |

| California | 6.6 | 6.3–6.9 | 9.7 | 9.3–10.2 | 3.5 | 3.2–3.8 | 11.4 | 11.1–11.8 | 17.2 | 16.6–17.8 | 5.7 | 5.4–6.1 | 7.3 | 7.7 | 6.3 |

| Colorado | 7.0 | 6.2–7.9 | 10.6 | 9.2–12.0 | 3.4 | 2.7–4.4 | 14.4 | 13.4–15.5 | 20.7 | 18.9–22.5 | 8.2 | 7.1–9.5 | 10.6 | 9.5 | 14.1 |

| Hawaii | 9.0 | 7.4–10.8 | 11.9 | 9.3–14.9 | 6.2 | 4.4–8.6 | 16.6 | 14.5–19.0 | 26.3 | 22.4–30.6 | 7.3 | 5.4–9.7 | 8.4 | 12.1 | 1.8 |

| Idaho | 6.1 | 4.8–7.6 | 8.4 | 6.2–11.0 | 4.0 | 2.5–5.9 | 16.5 | 14.5–18.7 | 25.7 | 22.1–29.7 | 7.6 | 5.7–9.8 | 17.0 | 20.6 | 9.0 |

| Nevada | 6.9 | 5.7–8.1 | 10.8 | 8.8–13.0 | 3.1 | 2.1–4.5 | 17.0 | 15.5–18.7 | 26.3 | 23.6–29.3 | 8.2 | 6.7–9.9 | 14.6 | 14.4 | 16.5 |

| New Mexico | 8.5 | 7.1–9.9 | 12.3 | 10.1–14.8 | 4.3 | 3.0–5.9 | 14.3 | 12.7–16.1 | 23.1 | 20.2–26.3 | 5.3 | 3.9–6.9 | 6.8 | 8.8 | 2.3 |

| Oregon | 6.2 | 5.4–7.1 | 8.5 | 7.2–10.0 | 3.9 | 3.0–4.9 | 10.8 | 9.8–11.9 | 16.4 | 14.6–18.3 | 5.2 | 4.2–6.3 | 7.4 | 9.3 | 3.3 |

| Utah | 7.9 | 6.7–9.4 | 12.2 | 10.1–14.7 | 3.7 | 2.5–5.3 | 19.0 | 17.3–20.9 | 29.4 | 26.3–32.6 | 8.7 | 7.1–10.7 | 14.1 | 14.1 | 13.5 |

| Washington | 7.8 | 7.1–8.6 | 11.5 | 10.3–12.7 | 4.2 | 3.4–5.0 | 12.9 | 12.1–13.8 | 19.9 | 18.5–21.5 | 6.0 | 5.2–6.8 | 6.5 | 7.3 | 4.3 |

Data source: U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group (6).

CI, confidence interval.

FIG. 1.

Trends in age-standardized thyroid cancer rates by gender and state for the time period 1999–2009: (A) male; (B) female.

FIG. 2.

Age standardized incidence rates of thyroid cancer by U.S. state for the time period 2005–2009.

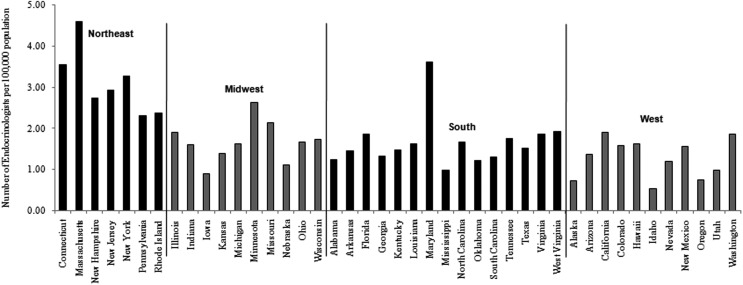

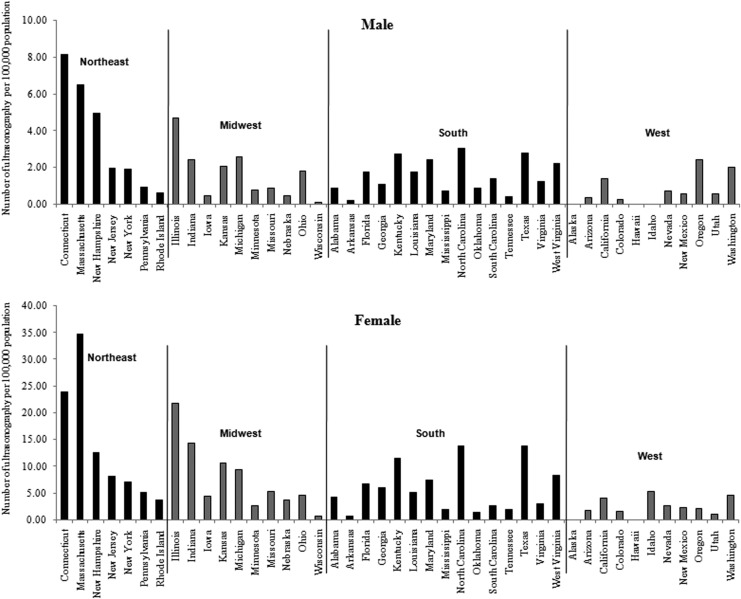

A total of 5923 endocrinologists, 27,533 general surgeons, and 97,936 primary care physicians were identified from the LifeScript Doctor Review list (7). As demonstrated in Figures 3 and 4, the densities of endocrinologists and general surgeons per 100,000 populations were also highest in the northeast. The incidence rates of thyroid cancer were significantly correlated with the densities of endocrinologists (r=0.58, p<0.0001 for males; r=0.44, p=0.0031 for females) and general surgeons (r=0.50, p=0.0006 for males; r=0.42, p=0.0045 for females). No significant associations between primary care physicians and the incidence rates of thyroid cancer were seen. The frequency of cervical ultrasonography was also highest in the northeast (Fig. 5). The linear correlation between the frequency of cervical ultrasonography and thyroid cancer incidence rates were statistically significant for both males (r=0.40, p=0.0091) and females (r=0.36, p=0.0197). However, there was no significant linear correlation between the frequency of thyroid biopsy and the incidence rates of thyroid cancer.

FIG. 3.

Density of endocrinologists by U.S. state (number of endocrinologists per 100,000 population).

FIG. 4.

Density of general surgeons by U.S. state (number of general surgeons per 100,000 population).

FIG. 5.

The counts of neck ultrasonography per 100,000 commercially insured population for the period 2005–2009.

When the regression model included the densities of endocrinologists and general surgeons as well as the frequency of cervical ultrasonography, these three variables explained about 57% of the variability in state-level incidence for males (R2=0.57, F=16.98, p<0.0001) and 49% for females (R2=0.49, F=12.01, p<0.0001). After controlling for median household income, the model explained an additional 2% of the variability for both males (R2=59, F=13.16, p<0.0001) and females (R2=0.51, F=9.74, p<0.0001).

Discussion

Our study supports the notion that the epidemic of thyroid cancer in the United States is due in large part to increased detection. These findings have broad and significant public health and economic implications. Most thyroid cancers are small papillary tumors that are relatively slow growing that heretofore would not have been diagnosed. The diagnosis of a cytologically proven thyroid cancer results, for the vast majority of patients, in referral for surgical intervention. The most commonly performed procedure for a cytologically proven thyroid cancer according to the American Thyroid Association Guidelines is a total thyroidectomy and may also include a coincident central neck lymph node (level VI) dissection (10). It is not clear if all or even most of these patients benefit from surgical extirpation of what had once been clinically occult disease. Autopsy series suggest that patients who die from nonthyroid cancer-related disease frequently have occult thyroid cancers. The autopsy prevalence rate of occult thyroid cancer in the Finnish population is 35.6%, suggesting that thyroid cancer is both common and clinically insignificant for the vast majority of individuals (11).

In Japan, a subset of patients with subcentimeter cytologically proven thyroid cancer is being followed in the absence of surgical intervention (12). With more than 10 years of follow-up, surgical intervention was performed in only one third of these patients. The majority showed no evidence of disease progression, as evidenced by either tumor growth or development of nodal metastases. Importantly, no patient appears to have been harmed by prudent observation. A recent study examined the risk of secondary cancers after a first thyroid cancer primary utilizing the SEER database found that the highest risk was observed in patients with recently diagnosed microcarcinomas, indicating a potential negative impact from treatment for occult thyroid microcarcinomas (13). This epidemic of thyroid cancer is a classic example of “cancer overdiagnosis” where the diagnosis is made in a silent disease reservoir and treatment is initiated for individuals who are unlikely to develop symptoms or have their life-spans shortened (14). It is likely that individuals with clinically insignificant thyroid cancer would not benefit from either surgery or additional treatments including radioactive iodine and lifelong thyroid hormone suppression and/or replacement.

Because the results from our study and another study (3) showed that approximately half of the variability in thyroid cancer incidence in either state or county levels could not be explained by the “overdiagnosis” theory, the possibility of environmental factors resulting in the increased incidence of thyroid cancer should also be considered.

There is a clear association between the development of thyroid cancer and exposure to ionizing radiation, especially in childhood. Supportive evidence includes the dramatic outbreak of thyroid cancer, particularly in children and young adults that occurred following nuclear accidents such as the Chernobyl event in 1986 (15). A dramatic rise in medical imaging includes the increased use of nuclear medicine studies and more strikingly axial imaging, particularly computed tomography (CT) scans, employed in children and young adults (16). The thyroid gland exposure during a head and neck CT scan is up to 52.0 mGy (17). Neck CT scans are associated with an increased risk of developing thyroid cancer up to 390 per million patients (17).

Chemical exposure should also be considered. Blood concentrations of polybrominated diphenyl ether flame retardants (PBDEs) alter thyroid hormone homeostasis and cause thyroid dysfunction (18). Exposure to PBDEs in the U.S. population has increased significantly during the past decades (19), paralleling the observed increasing trend of thyroid cancer. Although there is lack of direct human evidence, these chemicals have been speculated to be responsible for some of the increasing trend of thyroid cancer (20).

Obesity influences thyroid hormone levels and leads to insulin resistance and increased production of insulin and insulin-like growth factors, which have been linked to thyroid disorders (21,22). Epidemiological studies have consistently reported that individuals who are either overweight or obese are at an increased risk of thyroid cancer (23–27). The increasing trend of obesity might be another factor that accounts for some of the observed increasing incidence of thyroid cancer, although the degree of its contribution is unclear. Both deficiency and overconsumption of iodine have been suggested to be risk factors for thyroid cancer, although the results from epidemiologic studies have been inconsistent (28–30). Based on the data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), urinary iodine measurements have shown that the general U.S. population is iodine sufficient, although urinary iodine levels decreased by more than 50% between 1971 and 1974 and 1988 and 1994, and have remained stable since 2000 (31,32). It seems unlikely that the change in iodine consumption is a possible explanation of the increased trend of thyroid cancer in the Unites States.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the study results. The use of ultrasound is likely underrepresented by the OptumInsight. Many endocrinologists routinely use bedside ultrasound and don't bill unless there is a fine-needle aspiration. In addition, many patients would not be captured with this database, and there may be variability in the number captured based on region. While the LifeScript Doctor Review includes approximately 75% of the total number of U.S. doctors, it is unclear whether the coverage varies by state. Many identified general surgeons or endocrinologists may not focus on the thyroid. Endocrine surgeons, however, would be captured in the general surgeon population. Furthermore, we were unable to capture the density of otolaryngologists and their use of thyroid ultrasounds. Given these crude measurements, it is likely that the true associations between thyroid cancer incidence and the densities of endocrinologists and general surgeons, as well as the frequency of cervical ultrasound, were underestimated.

In conclusion, the thyroid cancer epidemic is real. The increased incidence of thyroid cancer is most likely due to overdiagnosis given that 57% of the variability in state-level incidence for males and 49% for females are due to densities of endocrinologists and general surgeons, and the use of ultrasound. It is likely that the majority of diagnosed thyroid cancer patients will not benefit from surgical and/or adjuvant interventions. As a medical community, we must critically analyze our response to treat heretofore undetectable and frequently indolent disease.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially supported by the NIH grant ES020361 and ACS grant RSGM-10-038-01-CCE.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist for either of the authors.

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute 2012SEER cancer statistics review 1975–2009. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2009_pops09 (accessed October30, 2012)

- 2.Davies L, Welch HG.2006Increasing incidence of thyroid cancer in the United States, 1973–2002. JAMA 295:2164–2167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris LG, Sikora AG, Tosteson TD, Davies L.2013The increasing incidence of thyroid cancer: the influence of access to care. Thyroid 23:885–891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Enewold LR, Zhou J, Devesa SS, Berrington de Gonzalez A, Anderson WF, Zahm SH, Stojadinovic A, Peoples GE, Marrogi AJ, Potter JF, McGlynn KA, Zhu K.2011Thyroid cancer incidence among active duty U.S. military personnel, 1990–2004. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 20:2369–2376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu C, Zheng T, Kilfoy BA, Han X, Ma S, Ba Y, Bai Y, Wang R, Zhu Y, Zhang Y.2009A birth cohort analysis of the incidence of papillary thyroid cancer in the United States, 1973–2004. Thyroid 19:1061–1066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group 2013United States cancer statistics: 1999–2010 incidence and mortality web-based report. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute, Atlanta, GA: Available at: www.cdc.gov/uscs [Google Scholar]

- 7.LifeScript Doctor Review 2013Find a local endocrinologist. Available at: www.lifescript.com/doctor-directory/specialty/endocrinology.aspx (accessed in May2013)

- 8.Oleen-Burkey M, Cyhaniuk A, Swallow E.2013Treatment patterns in multiple sclerosis: administrative claims analysis over 10 years. J Med Econ 16:397–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.U.S. Census Bureau 2012Income, poverty, and health insurance in the United States: 2011. Available at www.census.gov/hhes/www/income/data/incpovhlth/2011/stateonline_11.xls

- 10.Cooper DS, Doherty GM, Haugen BR, Kloos RT, Lee SL, Mandel SJ, Mazzaferri EL, McIver B, Pacini F, Schlumberger M, Sherman SI, Steward DL, Tuttle RM.2009Revised American Thyroid Association management guidelines for patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid 19:1167–1214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harach HR, Franssila KO, Wasenius VM.1985Occult papillary carcinoma of the thyroid. A “normal” finding in Finland. A systematic autopsy study. Cancer 56:531–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ito Y, Miyauchi A, Inoue H, Fukushima M, Kihara M, Higashiyama T, Tomoda C, Takamura Y, Kobayashi K, Miya A.2010An observational trial for papillary thyroid microcarcinoma in Japanese patients. World J Surg 34:28–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim C, Bi X, Pan D, Chen Y, Carling T, Ma S, Udelsman R, Zhang Y.2013The risk of second cancers after diagnosis of primary thyroid cancer is elevated in thyroid microcarcinomas. Thyroid 23:575–582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Welch HG, Black WC.2010Over-diagnosis in cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 102:605–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bard D, Verger P, Hubert P.1997Chernobyl, 10 years after: health consequences. Epidemiol Rev 19:187–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhargavan M.2008Trends in the utilization of medical procedures that use ionizing radiation. Health Phys 95:612–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mazonakis M, Tzedakis A, Damilakis J, Gourtsoyiannis N.2007Thyroid dose from common head and neck CT examinations in children: is there an excess risk for thyroid cancer induction? Eur Radiol 17:1352–1357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hallgren S, Darnerud PO.2002Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and chlorinated paraffins (CPs) in rats-testing interactions and mechanisms for thyroid hormone effects. Toxicology 177:227–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schecter A, Papke O, Tung KC, Joseph J, Harris TR, Dahlgren J.2005Polybrominated diphenyl ether flame retardants in the U.S. population: current levels, temporal trends, and comparison with dioxins, dibenzofurans, and polychlorinated biphenyls. J Occup Environ Med 47:199–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y, Guo GL, Han X, Zhu C, Kilfoy BA, Zhu Y, Boyle P, Zheng T.2008Do polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) increase the risk of thyroid cancer? Biosci Hypotheses 1:195–199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vella V, Sciacca L, Pandini G, Mineo R, Squatrito S, Vigneri R, Belfiore A.2001The IGF system in thyroid cancer: new concepts. Mol Pathol 54:121–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Volzke H, Friedrich N, Schipf S, Haring R, Ludemann J, Nauck M, Dorr M, Brabant G, Wallaschofski H.2007Association between serum insulin-like growth factor-I levels and thyroid disorders in a population-based study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:4039–4045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Renehan AG, Tyson M, Egger M, Heller RF, Zwahlen M.2008Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Lancet 371:569–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kitahara CM, Platz EA, Freeman LE, Hsing AW, Linet MS, Park Y, Schairer C, Schatzkin A, Shikany JM, Berrington de Gonzalez A.2011Obesity and thyroid cancer risk among U.S. men and women: a pooled analysis of five prospective studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 20:464–472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leitzmann MF, Brenner A, Moore SC, Koebnick C, Park Y, Hollenbeck A, Schatzkin A, Ron E.2010Prospective study of body mass index, physical activity and thyroid cancer. Int J Cancer 126:2947–2956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meinhold CL, Ron E, Schonfeld SJ, Alexander BH, Freedman DM, Linet MS, Berrington de Gonzalez A.2010Nonradiation risk factors for thyroid cancer in the US Radiologic Technologists Study. Am J Epidemiol 171:242–252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rinaldi S, Lise M, Clavel-Chapelon F, Boutron-Ruault MC, Guillas G, Overvad K, Tjonneland A, Halkjaer J, Lukanova A, Kaaks R, Bergmann MM, Boeing H, Trichopoulou A, Zylis D, Valanou E, Palli D, Agnoli C, Tumino R, Polidoro S, Mattiello A, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Peeters PH, Weiderpass E, Lund E, Skeie G, Rodriguez L, Travier N, Sanchez MJ, Amiano P, Huerta JM, Ardanaz E, Rasmuson T, Hallmans G, Almquist M, Manjer J, Tsilidis KK, Allen NE, Khaw KT, Wareham N, Byrnes G, Romieu I, Riboli E, Franceschi S.2012Body size and risk of differentiated thyroid carcinomas: findings from the EPIC study. Int J Cancer 131:E1004–E1014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clero E, Doyon F, Chungue V, Rachedi F, Boissin JL, Sebbag J, Shan L, Bost-Bezeaud F, Petitdidier P, Dewailly E, Rubino C, de Vathaire F.2012Dietary iodine and thyroid cancer risk in French Polynesia: a case-control study. Thyroid 22:422–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dal Maso L, Bosetti C, La Vecchia C, Franceschi S.2009Risk factors for thyroid cancer: an epidemiological review focused on nutritional factors. Cancer Causes Control 20:75–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horn-Ross PL, Morris JS, Lee M, West DW, Whittemore AS, McDougall IR, Nowels K, Stewart SL, Spate VL, Shiau AC, Krone MR.2001Iodine and thyroid cancer risk among women in a multiethnic population: the Bay Area Thyroid Cancer Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 10:979–985 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caldwell KL, Makhmudov A, Ely E, Jones RL, Wang RY.2011Iodine status of the U.S. population, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2005–2006 and 2007–2008. Thyroid 21:419–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hollowell JG, Staehling NW, Hannon WH, Flanders DW, Gunter EW, Maberly GF, Braverman LE, Pino S, Miller DT, Garbe PL, DeLozier DM, Jackson RJ.1998Iodine nutrition in the United States. Trends and public health implications: iodine excretion data from National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys I and III (1971–1974 and 1988–1994). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83:3401–3408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]