Abstract

Objective

To determine the optimal strategy for cervical cancer screening in women with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection by comparing two strategies: visual inspection of the cervix with acetic acid (VIA) and VIA followed immediately by visual inspection with Lugol’s iodine (VIA/VILI) in women with a positive VIA result.

Methods

Data from a cervical cancer screening programme embedded in two HIV clinic sites in western Kenya were evaluated. Women at a central site underwent VIA, while women at a peripheral site underwent VIA/VILI. All women positive for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse (CIN 2+) on VIA and/or VILI had a confirmatory colposcopy, with a biopsy if necessary. Overall test positivity, positive predictive value (PPV) and the CIN 2+ detection rate were calculated for the two screening methods, with biopsy being the gold standard.

Findings

Between October 2007 and October 2010, 2338 women were screened with VIA and 1124 with VIA/VILI. In the VIA group, 26.4% of the women tested positive for CIN 2+; in the VIA/VILI group, 21.7% tested positive (P < 0.01). Histologically confirmed CIN 2+ was detected in 8.9% and 7.8% (P = 0.27) of women in the VIA and VIA/VILI groups, respectively. The PPV of VIA for biopsy-confirmed CIN 2+ in a single round of screening was 35.2%, compared with 38.2% for VIA/VILI (P = 0.41).

Conclusion

The absence of any differences between VIA and VIA/VILI in detection rates or PPV for CIN 2+ suggests that VIA, an easy testing procedure, can be used alone as a cervical cancer screening strategy in low-income settings.

Résumé

Objectif

Déterminer la stratégie optimale pour dépister le cancer du col de l'utérus chez les femmes infectées par le virus de l'immunodéficience humaine (VIH) en comparant deux stratégies: l'inspection visuelle du col de l'utérus en utilisant de l'acide acétique (IVA) et l'IVA suivie immédiatement par une inspection visuelle en utilisant du soluté de Lugol (IVA/IVL) chez les femmes ayant obtenu un résultat positif pour l'IVA.

Méthodes

Les données provenant d'un programme de dépistage du cancer du col de l'utérus mis en œuvre dans deux sites cliniques pour le VIH dans l'ouest du Kenya ont été évaluées. Les femmes qui consultaient dans un site central ont été examinées par IVA alors que les femmes qui consultaient dans un site périphérique ont été examinées par IVA/IVL. Toutes les femmes présentant un résultat positif pour une néoplasie intraépithéliale du col de l'utérus de grade 2 ou supérieur (CIN 2+) après examen par IVA et/ou IVL ont ensuite eu une colposcopie de confirmation, avec une biopsie si nécessaire. La positivité globale du test, la valeur prédictive positive (VPP) et le taux de détection des lésions CIN 2+ ont été calculés pour les deux méthodes de dépistage, avec la biopsie comme référence absolue.

Résultats

Entre octobre 2007 et octobre 2010, 2338 femmes ont été examinées par IVA et 1124 par IVA/IVL. Dans le groupe IVA, 26,4% des femmes ont obtenu un résultat positif pour des lésions CIN 2+; dans le groupe IVA/IVL, 21,7% des femmes ont obtenu un résultat positif (P < 0,01). Des lésions CIN 2+ confirmées histologiquement ont été détectées chez 8,9% et 7,8% (P = 0,27) des femmes dans les groupes IVA et IVA/IVL, respectivement. La VPP de l'IVA pour les lésions CIN 2+ confirmées par biopsie dans une seule série de dépistage était de 35,2%, contre 38,2% pour l'IVA/IVL (P = 0,41).

Conclusion

L'absence de différence entre l'IVA et l'IVA/IVL pour les taux de détection ou la VPP des lésions CIN 2+ suggère que l'IVA est une procédure de test simple, qui peut être utilisée seule comme stratégie de dépistage du cancer du col de l'utérus dans les pays à faible revenu.

Resumen

Objetivo

Determinar la mejor estrategia para detectar el cáncer de cuello uterino en las mujeres con el virus de inmunodeficiencia humana (VIH) mediante la comparación de dos estrategias: la inspección visual del cuello uterino con ácido acético (IVAA) y la IVAA seguida inmediatamente de la inspección visual con yodo de Lugol (IVAA/IVYL) en mujeres con un resultado positivo en la IVAA.

Métodos

Se evaluaron los datos de un programa de detección de cáncer de cuello uterino integrado en dos centros clínicos de VIH en el oeste de Kenya. Las mujeres de una zona central se sometieron a la IVAA, mientras que las mujeres de una zona periférica se sometieron a la IVAA/IVYL. Se realizó una colposcopia de confirmación, además de una biopsia cuando era necesario, a todas las mujeres con un diagnóstico positivo de neoplasia intraepitelial cervical de grado 2 o peor (CIN 2+) en la IVAA y/o IVYL. Se calculó la positividad de la prueba general, el valor predictivo positivo (VPP) y la tasa de detección de CIN 2+ de ambos métodos de detección, con la biopsia como la regla de oro.

Resultados

Entre octubre de 2007 y octubre de 2010, se examinó a 2338 mujeres con la IVAA y a 1124 con la IVAA/IVYL. En el grupo IVAA, el 26,4 % de las mujeres dio positivo en CIN 2+, mientras que en el grupo IVAA/IVYL, el 21,7 % dio positivo (P < 0,01). Se detectó CIN 2+ con confirmación histológica en el 8,9 % y el 7,8 % (P = 0,27) de las mujeres de los grupos IVAA y IVAA/IVYL, respectivamente. El VPP de la IVAA para detectar CIN 2+ con confirmación por biopsia en una ronda única de detección fue del 35,2 %, comparado con el 38,2 % de IVAA/IVYL (P = 0,41).

Conclusión

La ausencia de diferencias entre la IVAA y la IVAA/IVYL en las tasas de detección o el VPP para detectar CIN 2+ indica que la IVAA, un procedimiento de prueba sencillo, puede utilizarse por separado como estrategia de detección de cáncer cervical en comunidades de bajos ingresos.

ملخص

الغرض

تحديد الاستراتيجية المثلى لتحري سرطان عنق الرحم لدى النساء المصابات بعدوى فيروس العوز المناعي البشري عن طريق مقارنة بين استراتيجيتين: الفحص البصري لعنق الرحم باستخدام حمض الخليك والفحص البصري لعنق الرحم باستخدام حمض الخليك المتبوع على الفور بالفحص البصري باستخدام يود لوغول مع النساء اللاتي كانت نتيجة الفحص البصري لعنق الرحم باستخدام حمض الخليك لديهن إيجابية.

الطريقة

تم تقييم البيانات المستمدة من برنامج لتحري سرطان عنق الرحم المدمج في موقعين سريريين لفيروس العوز المناعي البشري في مناطق غرب كينيا. وخضعت النساء في موقع مركزي لفحص بصري لعنق الرحم باستخدام حمض الخليك، في حين خضعت النساء في موقع طرفي لفحص بصري لعنق الرحم باستخدام حمض الخليك المتبوع على الفور بفحص بصري باستخدام يود لوغول. وخضعت جميع النساء الإيجابيات للورم العنقي داخل الظهارة من الدرجة الثانية أو الأسوأ (CIN 2+)، اللاتي خضعن للفحص البصري لعنق الرحم باستخدام حمض الخليك و/أو الفحص البصري باستخدام يود لوغول، لتنظير المهبل التوكيدي مع أخذ خزعة عند الاقتضاء. وبشكل عام، تم حساب إيجابية الاختبار والقيمة التنبؤية الإيجابية (PPV) ومعدل كشف CIN 2+ في طريقتي التحري، وكانت الخزعة هي المعيار الذهبي.

النتائج

في الفترة من تشرين الأول/ أكتوبر 2007 إلى تشرين الأول/ أكتوبر 2010، تم تحري 2338 سيدة بالفحص البصري لعنق الرحم باستخدام حمض الخليك و1124 سيدة بالفحص البصري لعنق الرحم باستخدام حمض الخليك/الفحص البصري باستخدام يود لوغول. وفي مجموعة الفحص البصري لعنق الرحم باستخدام حمض الخليك، كانت نسبة 26.4 % من النساء اللاتي اختبرن إيجابيات للورم العنقي داخل الظهارة من الدرجة الثانية أو الأسوأ؛ وفي مجموعة الفحص البصري لعنق الرحم باستخدام حمض الخليك المتبوع على الفور بالفحص البصري باستخدام يود لوغول، كانت نسبة 21.7 % من النساء اللاتي اختبرن إيجابيات (الاحتمال < 0.01). وتم التأكيد من حيث الأنسجة على كشف CIN 2+ في 8.9 % و7.8 % (الاحتمال = 0.27) من النساء في مجموعتي الفحص البصري لعنق الرحم باستخدام حمض الخليك والفحص البصري لعنق الرحم باستخدام حمض الخليك المتبوع على الفور بالفحص البصري باستخدام يود لوغول، على التوالي. وكانت القيمة التنبؤية الإيجابية للورم العنقي داخل الظهارة من الدرجة الثانية أو الأسوأ في الفحص البصري لعنق الرحم باستخدام حمض الخليك الذي تم توكيده بالخزعة في جولة واحدة من التحري 35.2 %، مقارنة بنسبة 38.2 % في الفحص البصري لعنق الرحم باستخدام حمض الخليك/ الفحص البصري باستخدام يود لوغول ( الاحتمال = 0.41).

الاستنتاج

يشير عدم وجود أي اختلافات بين الفحص البصري لعنق الرحم باستخدام حمض الخليك والفحص البصري لعنق الرحم باستخدام حمض الخليك المتبوع على الفور بالفحص البصري باستخدام يود لوغول في معدلات الكشف أو القيمة التنبؤية الإيجابية للورم العنقي داخل الظهارة من الدرجة الثانية أو الأسوأ إلى إمكانية استخدام الفحص البصري لعنق الرحم باستخدام حمض الخليك، أحد إجراءات الاختبار السهلة، منفرداً كاستراتيجية تحري لسرطان عنق الرحم في البيئات المنخفضة الدخل.

摘要

目的

通过比较两种策略确定艾滋病毒感染(HIV)妇女宫颈癌筛查最佳策略:一种是使用醋酸(VIA)的宫颈癌肉眼观察,另一种是使用VIA检查之后立即对VIA结果为阳性的女性使用吕戈尔碘染色肉眼观察(VIA/VILI)。

方法

对来自肯尼亚西部的两个艾滋病诊所的宫颈癌筛查计划的数据进行评价。对在中心诊疗点的女性执行VIA检查,对在外围诊疗点的女性执行VIA/VILI检查。对VIA和/或VILI检查结果中宫颈上皮内瘤变2级或以上(CIN 2+)呈阳性的所有女性进行阴道镜确诊检查,必要时使用活组织检查。对两种筛查方法计算整体检测阳性、阳性预测值(PPV)和CIN 2+检出率,以活检为黄金标准。

结果

在2007年10月和2010年10月之间,对2338名妇女进行了VIA检查,对1124名妇女进行了VIA/VILI检查。在VIA组中,26.4%的妇女检测为CIN 2+阳性,在VIA/VILI组中,21.7%的妇女检测为阳性(P < 0.01)。VIA和VIA/VILI组中的妇女分别有8.9%和7.8%(P = 0.27)经组织学确诊检测到CIN 2+。单轮筛查中,VIA组活检确认为CIN 2+的PPV是35.2%,VIA/VILI组则为38.2%(P = 0.41)。

结论

VIA和VIA/VILI在检出率或CIN 2+的PPV上没任何差别,这表明在低收入地区可以单纯使用VIA这种简易的检查程序作为宫颈癌筛查策略。

Резюме

Цель

Определить оптимальную стратегию скрининга рака шейки матки у женщин с вирусом иммунодефицита человека (ВИЧ) посредством сравнения двух стратегий: визуального осмотра и теста с уксусной кислотой (VIA) и теста с уксусной кислотой (VIA) с немедленным последующим визуальным осмотром и тестом с йодным раствором Люголя (VIA/VILI) у женщин с положительным результатом по итогам VIA.

Методы

Была проведена оценка данных программы скрининга рака шейки матки, которая была реализована в двух ВИЧ‑клиниках в западной части Кении. Женщины в центральной клинике прошли процедуру VIA, а женщины в периферийной клинике прошли процедуру VIA/VILI. В отношении всех женщин, у которых скрининг VIA или VILI выявил внутриэпителиальную неоплазию шейки матки второй степени или более тяжелое состояние (CIN 2+), была проведена кольпоскопия, а также, при необходимости, биопсия. Общий показатель положительных тестов, прогностичность положительного результата (PPV) и коэффициент обнаружения CIN 2+ были рассчитаны для обоих методов скрининга, причем результаты биопсии рассматривались в качестве эталонных.

Результаты

В период с октября 2007 года по октябрь 2010 года 2338 женщин были обследованы с использованием VIA и 1124 женщины — с использованием VIA/VILI. В группе, обследованной при помощи VIA, тесты 26,4% женщин оказались позитивными на CIN 2+, а в группе VIA/VILI 21,7% тестов дали положительный результат (P < 0,01). Гистологически подтвержденный CIN 2+ был обнаружен у 8,9% и 7,8% (Р = 0,27) женщин в группах VIA и VIA/VILI соответственно. PPV VIA для подтвержденного биопсией CIN 2+ в одном раунде скрининга составило 35,2% по сравнению с 38,2% в случае с VIA/VILI (Р = 0,41).

Вывод

Отсутствие каких-либо различий между VIA и VIA/VILI в части уровня обнаружения или PPV для CIN 2+ дает основания предположить, что более легкая процедура тестирования VIA может быть использована самостоятельно в качестве стратегии скрининга рака шейки матки в странах с низким уровнем доходов.

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the second most common cancer among women in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where resources for cancer prevention programmes are often scarce.1 Rates of cervical cancer in sub-Saharan Africa are among the highest in the world.2 Infection with human immunodeficiency (HIV) virus increases women’s risk for human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, cervical cancer precursor lesions and invasive cancer.3 Two thirds of the world’s cases of HIV infection are found in sub-Saharan Africa, where a shortage of resources and biological factors work synergistically to increase women’s lifetime risk for developing cervical cancer.4 As a result, cervical cancer prevention is a public health priority in sub-Saharan Africa, especially among HIV-infected women.

Different cervical cancer screening strategies, including cytology, visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA)or with Lugol’s iodine (VILI) and HPV testing have been investigated for use in LMICs, but seldom among HIV-infected women.5 The infrastructural requirements necessary for successful cytology programmes, including laboratory and transport facilities, trained cytopathologists and tracking systems for specimens and patients, along with the cost and need for multiple visits, make cytology-based programmes impossible to implement in most low-resource settings.6 The costs of currently available HPV tests, along with a high HIV–HPV coinfection rate, make HPV testing unsuitable as a population-level strategy in countries with a high prevalence of HIV infection.7,8 As a result, many international organizations and ministries of health in LMICs have recommended VIA or VIA followed by VILI (VIA/VILI) in cases with positive VIA results as the screening tests of choice in “see & treat” or “see & refer” cervical cancer prevention strategies.9

The overall test positivity rate and positive predictive value (PPV) are indicative of test performance in specific populations. Screening tests with a low PPV can result in an overburdened referral system or, in “see & treat” programmes, in many women being exposed to unnecessary treatment. Unlike sensitivity and specificity, PPV is influenced by population-specific disease prevalence and can be measured in operational settings where women only undergo diagnostic confirmation if their screening test is positive. Factors associated with HIV infection, including the prevalence of cervical lesions, their size and character and the concomitant presence of genital infections can influence the PPV of VIA or VIA/VILI and affect the overall impact and cost of a screening programme.10,11 In fact, a wide range of PPVs has been reported for visual screening tests performed in populations of HIV-infected women,12–14 making it difficult to estimate disease prevalence and plan for the costs and resources necessary for programme implementation.

To inform the implementation of the cervical cancer screening protocol in health facilities served by the Family AIDS Care and Education Services (FACES) programme, we evaluated the test positivity rate and PPV for VIA and VIA/VILI for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 (moderate dysplasia) or worse (CIN 2+) among HIV-infected women. To do this, we performed a cross-sectional analysis of results in women who underwent cervical cancer screening and received prevention services as part of their HIV care and treatment in Kisumu, Kenya.

Methods

Screening protocol

Cervical cancer screening was offered to women enrolled for care in the period from October 2007 to October 2010 at two HIV clinics supported by FACES in Kisumu, in the Nyanza Province of western Kenya, starting in October 2007.15 According to the FACES Cervical Cancer Screening and Prevention protocol, all women enrolled for HIV care were eligible for screening if they were at least 23 years old and not pregnant. All services were offered free of charge.

At the Lumumba Health Centre site, women underwent VIA. At the Kisumu District Hospital site, women underwent VIA, followed immediately by VILI if the VIA result was positive. All women with positive screening results (on VIA or on both VIA and VILI) were offered confirmatory testing with colposcopy and a biopsy of any lesions looking suspicious for CIN 2+. Colposcopies were performed at Lumumba Health Centre, which allowed women seen at that centre with a positive VIA to undergo colposcopy during the same visit. Women from Kisumu District Hospital were referred to Lumumba Health Centre for colposcopy based on positive results on both VIA and VILI. The two sites were approximately two kilometres apart and accessible through public transportation or on foot. Women with negative screening results (negative VIA in either group, positive VIA followed by negative VILI in the VIA/VILI group) were offered repeat screening in three years.

Biopsy specimens were stored in 10% buffered formalin at room temperature and analysed at the Kenya Medical Research Institute pathology laboratory in Nairobi. Results were categorized as negative, inflammation, CIN 1 (mild dysplasia), CIN 2+ or invasive cancer. For specimens with more than one diagnosis, the outcome was defined in terms of the most severe lesion. Closer surveillance with repeat screening after one year was offered to women with CIN 1 (diagnosed by colposcopic impression or biopsy) or with a colposcopic impression of CIN 2+ followed by a less severe biopsy result. Women with confirmed CIN 2+ were offered treatment with the loop electrosurgical excision procedure.16 Women with invasive cervical cancer were referred to hospitals for appropriate treatment.

Testing procedures

VIA and VILI were performed by trained and certified clinical officers and nurses. VIA was considered positive if a well-defined, opaque, densely acetowhite lesion was seen near the border of the squamocolumnar junction one minute after the application of a 3–5% acetic acid solution. VILI was defined as positive if a yellow-staining lesion (saffron or mustard in colour) was seen near the squamocolumnar junction after application of Lugol’s iodine. Women who had cervical friability, erythema or pus were diagnosed with cervicitis, treated with antibiotics and invited to return for screening after resolution of the infection. Tests were considered unsatisfactory if the squamocolumnar junction could not be identified or, for VILI, if uptake of Lugol’s iodine throughout the cervix was inadequate. Colposcopy was performed by two trained and certified providers (one nurse and one clinical officer) using standard guidelines for visual impression of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia.17

Calculation of positive predictive value

We calculated the PPV of VIA and VIA/VILI for the detection of CIN 2+ by dividing the number of biopsy confirmed CIN 2+ cases (true positives) by the number of positive screening tests. Test positivity was defined as a positive VIA result in the VIA group or as a positive result on both tests in the VIA/VILI group. For this analysis, women with visual signs of inflammation or unsatisfactory VIA or VILI results were excluded from the calculation of PPV, although they may have been referred for colposcopy. Women who underwent colposcopic biopsies but whose results were missing were also excluded. CIN 2+ results from the primary screening were used to calculate PPV.

Data collection and statistical analysis

The results of VIA, VILI, colposcopy – and information on whether a biopsy was performed – were collected at the time of the screening visit and entered into a Microsoft Access Database (Microsoft Inc., Redmond, United States of America). Data on clinical and demographic variables, including age, relationship status, education, reproductive history, use of family planning methods, CD4+ T-lymphocyte (CD4+ cell) count, stage of HIV infection according to the classification of the World Health Organization (WHO), duration of clinical care at FACES and highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) treatment were collected as part of routine clinical care and entered into OpenMRS, an electronic medical record system. Each woman’s lowest recorded CD4+ cell count was extracted and categorized as being under 200, from 200 to 350, from 351 to 500 and over 500 cells per microlitre (cells/µl). For those on HAART, the time since the confirmed initiation of a three-drug regimen and the type of regimen given at screening (first-line, second-line or other) were extracted.

To address incompleteness in the demographic variables, we performed multiple imputation using chained equations with logistic regression, ordinal regression, truncated linear regression and predictive mean matching. Observations with missing biopsy results or with HIV clinical care of unknown duration were excluded. We imputed 50 data sets and assessed the plausibility of the imputed values using diagnostic plots.18 Because the results of the regression models using the imputed data were not significantly different from those for the complete data set, we only present the results from the original data set.

Significant differences in positivity rates by demographic and clinical predictors were assessed for VIA and VIA/VILI independently. Pearson’s χ2 test was used to compare screening outcomes for categorical variables and proportions; Student’s t-test was used for continuous variables. Fisher's exact test was used for comparisons of proportions with fewer than eight observations per cell. As this evaluation was based on data from a clinical programme, we did not calculate the sample size necessary to determine these outcomes. Multivariable logistic regression modelling using a backward elimination approach was carried out for any predictors with a significance level of < 0.1 and with complete data for VIA and VIA/VILI independently on more than two thirds of the original data set. Models were selected based on statistical significance and highest strength of correlation for imputed data with no significant difference in trends in the original data set. Imputation and all statistical analyses were performed in Stata 11 (StataCorp LP, College Station, USA) and graphs were created with Excel 2007 (Microsoft, Seattle, USA).

Approval for the study was obtained from the Committee on Human Research at the University of California, San Francisco, and the Ethical Review Committee at the Kenya Medical Research Institute.

Results

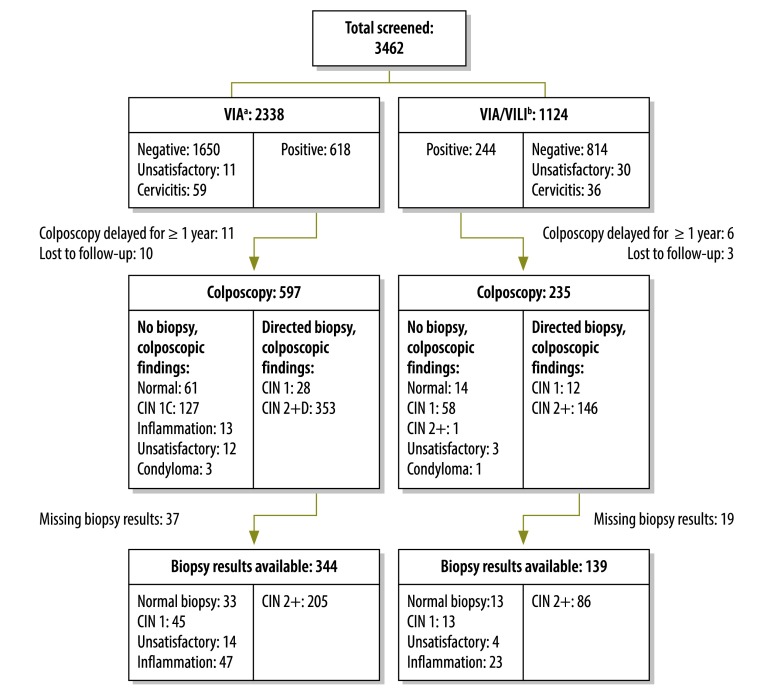

Between October 2007 and October 2010, 3462 women between the ages of 23 and 60 years underwent cervical cancer screening in two FACES-supported HIV clinics in Kisumu, Kenya. Eligibility and initial screening results are shown in Fig. 1. Women in the VIA group were slightly younger, had more pregnancies, had used hormonal contraception more often in the past 90 days and were more likely to be on HAART than those in the VIA/VILI group (Table 1). Of the 2338 women in the VIA group, 618 (26.4%) had a positive result; of these women, 597 (96.6%) underwent immediate colposcopy. Among the 1124 women in the VIA/VILI group, 244 (21.7%) had a positive result on both tests and were referred for colposcopy (P < 0.01). Of these women, 235 (96.3%) underwent colposcopy within one year of the positive screening test (mean time to colposcopy: 15.7 days). The prevalence of histologically confirmed CIN 2+ was 8.9% and 7.8% (P = 0.27), respectively, in the VIA and VIA/VILI groups. For every case of CIN 2+ that was detected, 2.9 colposcopies and 2.7 colposcopies (P = 0.57) were performed in the VIA and VIA/VILI groups, respectively. The PPV of VIA for a biopsy-confirmed primary outcome of CIN 2+ on initial screening was 35.2%, compared with 38.2% for VIA/VILI (P = 0.41) (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of single round of cervical cancer screening of HIV-positive women with two primary screening strategies and results of colposcopy and biopsy, Kisumu, Kenya, October 2007 to October 2010

CIN 1, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 1 (mild dysplasia); CIN 2+, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 (moderate dysplasia) or worse; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

a Cervical visual inspection with acetic acid.

b VIA, followed by visual inspection with Lugol’s iodine if VIA was positive for CIN 2+.

Table 1. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of HIV-infected women screened for cervical cancer with two different screening strategies, Kisumu, Kenya, October 2007 to October 2010.

| Characteristic | Total n | VIAa (n = 2336) | VIA/VILIb (n = 1124) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean, (SD) | – | 34.9 (8.2) | 35.7 (8.7) | 0.01 |

| Education, no., (%) | 1565 | 0.65 | ||

| Attended primary school | – | 578 (57.8) | 332 (58.8) | |

| Attended secondary school | – | 327 (32.7) | 184 (32.6) | |

| Attended university | – | 95 (9.5) | 49 (8.7) | |

| Relationship status,c no., (%) | 1539 | 0.78 | ||

| No current partner | – | 471 (48.4) | 269 (47.6) | |

| At least one current partner | – | 503 (51.6) | 296 (52.4) | |

| Reproductive history, no., (SD) | 900 | < 0.01 | ||

| Pregnancies | – | 3.4 (2.3) | 2.2 (1.5) | |

| Hormonal contraceptive use,d no., (%) | 2966 | < 0.01 | ||

| Oral | – | 505 (23.0) | 163 (21.5) | 0.37 |

| Injectable | – | 459 (20.7) | 32 (4.2) | < 0.001 |

| Implant | – | 18 (0.8) | 14 (1.8) | 0.02 |

| Intrauterine device in placee | – | 16 (0.7) | 9 (1.2) | 0.24 |

| HIV-related parameters | ||||

| Months since diagnosis of HIV infection, mean, (SD) | – | 12.4 (14.0) | 15.9 (15.4) | < 0.01 |

| WHO stage of HIV infection, no., (%) | 3326 | 0.10 | ||

| 1 | – | 508 (22.2) | 210 (21.0) | |

| 2 | – | 598 (26.0) | 267 (26.2) | |

| 3 | – | 835 (36.2) | 473 (46.5) | |

| 4 | – | 367 (15.9) | 68 (6.9) | |

| CD4+ cell nadir (cells/µL), no., (%) | 2841 | 0.77 | ||

| < 200 | – | 593 (29.4) | 250 (30.4) | |

| 201–350 | – | 655 (32.5) | 246 (29.9) | |

| 351–500 | – | 395 (19.6) | 164 (19.9) | |

| > 500 | – | 375 (18.6) | 163 (19.8) | |

| On HAART, no., (%) | 3460 | 1367 (58.5) | 402 (35.8) | < 0.01 |

| Months on HAART, mean, (SD) | – | 10.5 (7.4) | 5.0 (6.8) | < 0.01 |

| On first-line HAART regimen,f no. (%) | 1769 | 1308 (95.7) | 394 (98.0) | 0.04 |

| Months in care before HAART initiation, mean, (SD) | – | 4.5 (8.0) | 14.4 (12.8) | < 0.01 |

| CCSP performed at FACES enrolment visit, no., (%) | 3460 | 109 (4.7) | 144 (12.8) | < 0.01 |

CCSP, cervical cancer screening and prevention; CIN 2+, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 (moderate dysplasia) or worse; FACES, Family AIDS Care and Education Services; HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; SD, standard deviation; WHO, World Health Organization.

a Cervical visual inspection with acetic acid.

b VIA, followed by visual inspection with Lugol’s iodine if VIA was positive for CIN 2+.

c Women were defined as having a current partner if they reported living with a spouse or unmarried partner.

d Within the 90 days preceding the screening visit. Women may have been using more than one method.

e At the time of this analysis, levonorgestrol-releasing intrauterine devices (IUDs) were not available in western Kenya. Therefore, IUDs are not classified under hormonal contraception.

f First-line HAART regimens consisted of a triple drug combination of either zidovudine or stavudine + lamivudine + either nevirapine or efaviranz.

Note: Row totals reflect missing data. The sum of the percentages for each predictor may not equal 100 due to rounding. VIA was performed on 2338 women and VIA/VILI on 1124 women. Excluded from this table are 2 women with missing demographic information.

Table 2. Comparative performance of two different cervical cancer screening strategies in HIV-infected women, Kisumu, Kenya, October 2007 to October 2010.

| Characteristic | VIAa | VIA/VILIb | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screening positivity rate, % | 26.4 | 21.7 | 0.003 |

| Follow-up colposcopy rate, % | 96.6 | 96.3 | 0.743 |

| Prevalence of CIN 2+ detected in a single screening round, % | 8.9 | 7.8 | 0.271 |

| PPV for CIN 2+ in a single screening round, % | 35.2 | 38.2 | 0.409 |

CIN 2+, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 (moderate dysplasia) or worse; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PPV: positive predictive value.

a Cervical visual inspection with acetic acid.

b VIA, followed by visual inspection with Lugol’s iodine if VIA was positive for CIN 2+.

Follow-up colposcopy data were available for only 65 (17%) of the 377 women referred for increased surveillance on account of abnormal results on the first round of screening. More women in the VIA group (55 of 266, or 21%) than in the VIA/VILI group (10 of 111, or 9%) had follow-up tests (P < 0.01). Among the women who did, 19 (29%) additional cases of CIN 2+ were identified over the three-year study period: 17 among women in the VIA group and two among women in the VIA/VILI group. All additional cases of CIN 2+ were found at the first follow-up colposcopy. Among women who had more than one follow-up colposcopy, no additional cases of CIN 2+ were identified.

In bivariate analysis, older age was associated with significantly reduced odds of a positive screening result in both the VIA and the VIA/VILI group (Table 3). In the VIA group, women using combined oral contraceptives or progesterone implants and women who had a longer history of HIV positivity had increased age-adjusted odds of testing positively on screening. In this group, having advanced HIV infection, having been on HAART treatment for longer and being on a first-line antiretroviral regimen were negatively associated with the age-adjusted odds of a positive screening result. In the VIA/VILI group, only the use of oral contraceptives was significantly associated with the odds of a positive screening result. When evaluated in a multivariate model with adjustment for age, length of time on HAART continued to show a significant negative association with the odds of a positive VIA result (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] per month on HAART: 0.97; 95% confidence interval, CI: 0.96–0.99), while the odds of using combined oral contraceptive pills (aOR: 1.56; 95% CI: 1.24–1.96) or progesterone implants (aOR: 15.46, 95% CI: 2.94–81.34) continued to show a significant positive association with the odds of a positive VIA result in all women. For women in the VIA/VILI group, the only significant association in the multivariate model was a positive one between the use of oral contraceptive pills and the odds of having a positive VIA result (aOR: 1.53; 95% CI: 1.02–2.77).

Table 3. Demographic and clinical predictors of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse (CIN 2+) in HIV-infected women screened for cervical cancer with two different screening strategies, Kisumu, Kenya, October 2007 to October 2010.

| Predictor | Total n | VIAa (n = 2266) |

VIA/VILIb (n = 1 058) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative (n = 1650) | Positive (n = 616) | ORc | 95% CI | Negative (n = 814) | Positive (n = 244) | ORc | 95% CI | |||

| Age (years), mean, (SD) | – | 35.5 (8.7) | 33.5 (6.8) | 0.97 | 0.96–0.98 | 36.7 (9.1) | 32.9 (6.7) | 0.94 | 0.92–0.96 | |

| Relationship status, no., (%) | 1539 | |||||||||

| No current partner | 317 (48.9) | 136 (46.7) | 1.00 | – | 188 (47.2) | 71 (50.7) | 1.00 | – | ||

| At least one current partner | 331 (51.1) | 155 (53.3) | 0.92 | 0.69–1.23 | 206 (52.3) | 69 (49.3) | 0.83 | 0.56–1.23 | ||

| Reproductive history, no., (%) | 900 | |||||||||

| Pregnancies | – | 3.55 (2.4) | 3.14 (2.0) | 0.99 | 0.91–1.08 | 2.7 (1.5) | 2.2 (1.5) | 1.02 | 0.50–2.09 | |

| Hormonal contraceptive used | 2966 | |||||||||

| Oral | 318 (20.5) | 175 (30.6) | 1.55 | 1.24–1.93 | 92 (17.8) | 59 (30.3) | 1.62 | 1.09–2.39 | ||

| Injectable | – | 309 (19.9) | 130 (22.0) | 1.01 | 0.80–1.28 | 24 (4.7) | 8 (4.1) | 0.68 | 0.30–1.57 | |

| Implant | – | 2 (0.2) | 16 (2.8) | 20.1 | 4.6–88.0 | 6 (1.2) | 8 (4.1) | 2.83 | 0.95–8.41 | |

| Intrauterine device in placee | – | 11 (0.7) | 4 (0.7) | 0.99 | 0.31–3.12 | 7 (1.4) | 2 (1.0) | 0.88 | 0.18–4.36 | |

| HIV-related parameters | ||||||||||

| Months since diagnosis of HIV infection, mean, (SD) | – | 11.2 (11.9) | 14.5 (17.0) | 1.02 | 1.01–1.03 | 16.8 (15.6) | 14.2 (15.3) | 0.99 | 0.98–1.00 | |

| WHO stage, no., (%) | 3326 | |||||||||

| 1 | – | 336 (21.0) | 152 (25.2) | 1.00 | – | 152 (20.8) | 40 (17.9) | 1.00 | – | |

| 2 | – | 419 (25.6) | 163 (27.0) | 0.92 | 0.70–1.20 | 190 (26.0) | 57 (25.5) | 1.30 | 0.81–2.06 | |

| 3 | – | 600 (36.7) | 211 (34.9) | 0.87 | 0.68–1.13 | 339 (46.4) | 112 (50.0) | 1.49 | 0.98–2.26 | |

| 4 | – | 279 (17.1) | 78 (12.9) | 0.69 | 0.50–0.95 | 49 (6.7) | 15 (6.7) | 1.35 | 0.68–2.68 | |

| CD4+ cell nadir (cells/µL), no., (%) | 2841 | |||||||||

| < 200 | – | 407 (28.6) | 168 (31.5) | 1.00 | – | 166 (29.2) | 69 (34.5) | 1.00 | – | |

| 201–350 | – | 468 (32.8) | 169 (31.7) | 0.86 | 0.67–1.11 | 168 29.5) | 64 (32.0) | 0.91 | 0.60–1.37 | |

| 351–500 | – | 286 (20.1) | 97 (18.2) | 0.79 | 0.59–1.06 | 122 (21.4) | 32 (16.0) | 0.64 | 0.39–1.04 | |

| > 500 | – | 264 (18.5) | 100 (18.7) | 0.85 | 0.63–1.14 | 113 (19.9) | 35 (17.5) | 0.69 | 0.43–1.12 | |

| On HAART, no., (%) | 3460 | 988 (59.9) | 341 (55.4) | 0.89 | 0.73–1.07 | 281 (34.5) | 96 (39.3) | 1.29 | 0.95–1.74 | |

| Months on HAART, mean (SD) | – | 11.0 (7.4) | 9.2 (7.3) | 0.97 | 0.95–0.98 | 4.8 (6.9) | 5.6 (7.1) | 1.02 | 0.99–1.05 | |

| On first-line regimen, no. (%) | 1769 | 950 (96.2) | 321 (94.1) | 0.57 | 0.32–0.99 | 276 (98.2) | 93 (96.9) | 0.64 | 0.15–2.83 | |

| Months in care before HAART initiation, mean (SD) | – | 4.5 (8.0) | 4.2 (7.9) | 0.99 | 0.98–1.01 | 15.3 (16.3) | 11.7 (15.6) | 0.99 | 0.97–1.01 | |

| CCSP performed at enrolment in HIV care, no. (%) | 3460 | 75 (4.5) | 31 (5.2) | 1.15 | 0.75–1.77 | 98 (12.0) | 35 (14.3) | 1.20 | 0.79–1.83 | |

CCSP, cervical cancer screening and prevention; CI, confidence interval; HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; OR, odds ratio; SD, standard deviation; WHO, World Health Organization.

a Cervical visual inspection with acetic acid.

b VIA, followed by visual inspection with Lugol’s iodine if VIA was positive for CIN 2+ (moderate dysplasia or worse).

c The ORs of all predictors (except age) are adjusted for age at screening test.

d Within the 90 days preceding the screening visit.

e At the time of this analysis, levonorgestrol-releasing intrauterine devices (IUDs) were not available in western Kenya. Therefore, IUDs are not classified under hormonal contraception.

Note: Row totals reflect missing data. The sum of the percentages for each predictor may not equal 100 due to rounding. VIA was performed on 2338 women and VIA/VILI on 1124 women. Excluded from this table are 138 women: 95 with cervicitis, 41 with unsatisfactory screening results and 2 with missing demographic information.

In all women, regardless of screening strategy, test positivity rates and the proportion of cases with CIN 2+ decreased with increasing age. As a result, optimal PPV was achieved in both groups among women between 30 and 35 years of age, with a significantly lower PPV among women between the ages of 23 and 29 years and older than 35 years (P < 0.001 for trend in both the VIA and the VIA/VILI group).

Discussion

This paper presents outcomes from a cervical cancer screening and prevention programme among almost 3500 HIV-infected women using two different visual inspection techniques in a low-resource clinical setting. Although this study took place in western Kenya, this experience may be applicable to similar settings in other LMICs and may help with protocol planning and decision-making for clinicians and programme managers alike. Our analysis suggests that a screening strategy based on performing VILI immediately after obtaining a positive result on VIA was only slightly more efficient than VIA alone. The two strategies yielded a similar prevalence of CIN 2+ (8.9% versus 7.8%) and had similar PPVs (35.2% versus 38.2%).

As cervical cancer prevention captures increasing attention and resources, WHO and many LMICs are introducing recommendations for programmes that apply “see & treat” strategies based on VIA followed by VILI coupled with cryotherapy.19 Although “see & treat” programmes are more cost-effective and sustainable than those requiring multiple visits for disease confirmation, one of their drawbacks is that the prevalence of CIN 2+ among women receiving treatment is unknown. By using biopsy results as a gold standard, we were able to predict the true prevalence of disease requiring treatment, along with rates of overtreatment, in a “see & treat” programme.

When we stratified our results by age group, we observed lower test positivity rates among older women in both the VIA and the VIA/VILI group. CIN 2+ was also somewhat less frequent in older women and the PPV of both screening strategies was correspondingly slightly lower in this group, albeit to a statistically significant degree. This lower risk of CIN 2+ among older women is in keeping with the results of other studies.20,21 However, it is also possible that the sensitivity of unaided visual screening is lower in older women because with age the transformation zone becomes less clearly visible during speculum examination – a recognized drawback of screening methods based on visual inspection.22 This situation needs to be further explored in a study in which all participants undergo colposcopy with biopsy, regardless of screening results, especially in light of the findings of another study among HIV-infected women in Kenya that showed an increase in CIN 2+ with age.23

Our results also show higher rates of positive VIA results among women using certain types of hormonal contraceptives and those who had known of their positivity to HIV for a longer time. In addition, being on a first-line regimen and having been on HAART for longer were associated with lower odds of having a positive VIA. Unlike the observed association between older age and lower rates of VIA positivity, for which the effect of age on the visibility of the transformation zone and hence on test performance is a biologically plausible explanation, these results may reflect an association between the use of hormonal contraceptives, immunosuppression and CIN 2+. Although the relationship between immunosuppression and the risk of CIN 2+ has been well established, the role played by hormonal contraceptives in this relationship is still controversial.24–26 Owing to confounding behavioural characteristics, the data obtained in this study allow no conclusion to be drawn about the relationship between screening test performance, CIN 2+ prevalence and the use of hormonal contraceptives.

We have previously shown that the screening programme described in this paper had high uptake and that satisfaction on the part of both patients and providers was high. Also the screening and treatment procedures were safe and acceptable to both patients and providers.16,27,28 In this paper, we show that the rate of follow-up colposcopy was high (96%), even among women who had to go to a different clinic to undergo colposcopy. This probably reflects the effect of counselling and of close geographic proximity and pre-existing linkages for other aspects of HIV care between the two sites where women were tested. This finding is encouraging for the many programmes that need to couple screening with either a diagnostic or a treatment visit at a second site nearby. However, a striking finding from this report is the attrition rate in the women requiring increased surveillance. Results were available for only 17% of those women who should have had a second or third colposcopy, and the proportion was significantly lower in women receiving their care in the clinical site not equipped for colposcopy. A portion of the loss to follow-up is probably attributable to some women having transferred or dropped out of HIV care. However, better procedures for identifying, tracing and screening this group of women are clearly necessary.

One of the main strengths of this study is that it included a large number of women undergoing cervical cancer screening as part of routine, comprehensive HIV care. While this provides insight into actual practice, there were also limitations to this analysis. Results were missing from 10% of the women who underwent biopsy and who therefore had to be excluded from the analysis. If these results had been included, the prevalence of CIN 2+ and PPV would probably have increased. However, the loss of biopsy results is problematic in biopsy-based programmes. Another limitation of our data set is the lack of colposcopic or biopsy data for women with a negative screening result. Although this would have provided the reference standard necessary to calculate the sensitivity, specificity and negative predictive value of VIA and VIA/VILI, universal colposcopy is not part of standard clinical care and would not have been feasible in this setting. Therefore, we were unable to calculate these additional important test parameters.

In summary, cervical cancer continues to affect large numbers of women and burdens health-care systems in LMICs. HIV-infected women, who have an increased risk of developing the disease, carry a disproportionate amount of the burden. Therefore, appropriate screening strategy for this population is needed. We have shown that VIA and VIA/VILI have similar PPV for CIN 2+ in HIV-positive women in western Kenya, with only slightly better diagnostic efficiency in the VIA/VILI group. Given the additional resources and training necessary to perform two screening tests rather than a single one, VIA alone appears to be a more suitable strategy for cervical cancer screening in HIV clinics.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sasco AJ, Jaquet A, Boidin E, Ekouevi DK, Thouillot F, Lemabec T, et al. The challenge of AIDS-related malignancies in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8621. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moodley JR, Hoffman M, Carrara H, Allan BR, Cooper DD, Rosenberg L, et al. HIV and pre-neoplastic and neoplastic lesions of the cervix in South Africa: a case-control study. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Global Report: UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic 2010 Geneva: UNAIDS; 2010.

- 5.Arbyn M, Sankaranarayanan R, Muwonge R, Keita N, Dolo A, Mbalawa CG, et al. Pooled analysis of the accuracy of five cervical cancer screening tests assessed in eleven studies in Africa and India. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:153–60. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holschneider CH, Ghosh K, Montz FJ. See-and-treat in the management of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions of the cervix: a resource utilization analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:377–85. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(99)00337-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dols JA, Reid G, Brown JM, Tempelman H, Bontekoe TR, Quint WG, et al. HPV Type Distribution and Cervical Cytology among HIV-Positive Tanzanian and South African Women. ISRN Obstet Gynecol. 2012;2012:514146. doi: 10.5402/2012/514146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silverberg MJ, Schneider MF, Silver B, Anastos KM, Burk RD, Minkoff H, et al. Serological detection of human papillomavirus type 16 infection in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive and high-risk HIV-negative women. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2006;13:511–9. doi: 10.1128/CVI.13.4.511-519.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Comprehensive cervical cancer control: a guide to essential practice Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horo A, Jaquet A, Ekouevi DK, Toure B, Coffie PA, Effi B, et al. IeDEA West Africa Collaboration Cervical cancer screening by visual inspection in Côte d’Ivoire, operational and clinical aspects according to HIV status. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:237. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maiman M, Fruchter RG, Sedlis A, Feldman J, Chen P, Burk RD, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and accuracy of cytologic screening for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in women with the human immunodeficiency virus. Gynecol Oncol. 1998;68:233–9. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1998.4938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moon TD, Silva-Matos C, Cordoso A, Baptista AJ, Sidat M, Vermund SH. Implementation of cervical cancer screening using visual inspection with acetic acid in rural Mozambique: successes and challenges using HIV care and treatment programme investments in Zambézia Province. J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15:17406. doi: 10.7448/IAS.15.2.17406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mabeya H, Khozaim K, Liu T, Orango O, Chumba D, Pisharodi L, et al. Comparison of conventional cervical cytology versus visual inspection with acetic acid among human immunodeficiency virus-infected women in Western Kenya. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2012;16:92–7. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e3182320f0c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Firnhaber C, Mayisela N, Mao L, Williams S, Swarts A, Faesen M, et al. Validation of cervical cancer screening methods in HIV positive women from Johannesburg South Africa. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53494. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis Kulzer J, Penner JA, Marima R, Oyaro P, Oyanga AO, Shade SB, et al. Family model of HIV care and treatment: a retrospective study in Kenya. J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15:8. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-15-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huchko MJ, Maloba M, Bukusi EA. Safety of the loop electrosurgical excision procedure performed by clinical officers in an HIV primary care setting. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2010;111:89–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walker P, Dexeus S, De Palo G, Barrasso R, Campion M, Girardi F, et al. Nomenclature Committee of the International Federation for Cervical Pathology and Colposcopy International terminology of colposcopy: an updated report from the International Federation for Cervical Pathology and Colposcopy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:175–7. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(02)02581-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eddings W, Marchenko Y. Diagnostics for multiple imputation in Stata. Stata J. 2012;12:353–67. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santesso N, Schünemann H, Blumenthal P, De Vuyst H, Gage J, Garcia F, et al. World Health Organization Steering Committee for Recommendations on Use of Cryotherapy for Cervical Cancer Prevention World Health Organization Guidelines: Use of cryotherapy for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;118:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leinonen MK, Nieminen P, Lönnberg S, Malila N, Hakama M, Pokhrel A, et al. Detection rates of precancerous and cancerous cervical lesions within one screening round of primary human papillomavirus DNA testing: prospective randomised trial in Finland. BMJ. 2012;345(nov29 3):e7789. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ronco G, Giorgi-Rossi P, Carozzi F, Confortini M, Dalla Palma P, Del Mistro A, et al. New Technologies for Cervical Cancer screening (NTCC) Working Group Efficacy of human papillomavirus testing for the detection of invasive cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:249–57. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cremer M, Conlisk E, Maza M, Bullard K, Peralta E, Siedhoff M, et al. Adequacy of visual inspection with acetic acid in women of advancing age. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;113:68–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Vuyst H, Mugo NR, Chung MH, McKenzie KP, Nyongesa-Malava E, Tenet V, et al. Prevalence and determinants of human papillomavirus infection and cervical lesions in HIV-positive women in Kenya. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:1624–30. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Longatto-Filho A, Hammes LS, Sarian LO, Roteli-Martins C, Derchain SF, Eržen M, et al. Hormonal contraceptives and the length of their use are not independent risk factors for high-risk HPV infections or high-grade CIN. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2011;71:93–103. doi: 10.1159/000320742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Syrjänen K. New concepts on risk factors of HPV and novel screening strategies for cervical cancer precursors. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2008;29:205–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Denny LA, Franceschi S, de Sanjosé S, Heard I, Moscicki AB, Palefsky J. Human papillomavirus, human immunodeficiency virus and immunosuppression. Vaccine. 2012;30(Suppl 5):F168–74. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huchko MJ, Bukusi EA, Cohen CR. Building capacity for cervical cancer screening in outpatient HIV clinics in the Nyanza province of western Kenya. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;114:106–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woo VG, Cohen CR, Bukusi EA, Huchko MJ. Loop electrosurgical excision procedure: safety and tolerability among human immunodeficiency virus-positive Kenyan women. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:554–9. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31822b0991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]