Abstract

Health video blogs (vlogs) allow individuals with chronic illnesses to share their stories, experiences, and knowledge with the general public. Furthermore, health vlogs help in creating a connection between the vlogger and the viewers. In this work, we present a qualitative study examining the various methods that health vloggers use to establish a connection with their viewers. We found that vloggers used genres to express specific messages to their viewers while using the uniqueness of video to establish a deeper connection with their viewers. Health vloggers also explicitly sought interaction with their viewers. Based on these results, we present design implications to help facilitate and build sustainable communities for vloggers.

Author Keywords: Health vlogs, YouTube, video blogging, chronic illness management, communication, patient-centered

General Terms: Human Factors

INTRODUCTION

Lily’s first video on her YouTube channel showed her joking about wearing a “beautiful [neck] brace” due to lesions on her spine because of her breast cancer. Sixty-three videos and 10 months later, the last video uploaded showed a solemn man, Lily’s husband. “This update is long and coming. I apologize for its tardiness…Lily passed last Saturday. She lost the battle.” As he paused and continued to speak about the messages (“don’t take labels, be yourself, make a difference in the world”) his wife wanted to remind her viewers, he became emotional and apologized, “Forgive me, this is a little hard.” Although it had only been 7 days since his wife had passed away, Lily’s husband still felt the need to update his wife’s viewers, treating them as if they actually knew her and were friends. It is clear that Lily felt a strong connection with those who watched her videos (her videos had a total of 11,806 views). Many people like Lily opt to share their story with the public through social networking websites and blogs. Over the years traditional text-based blogs have evolved to support various presentation forms—art blogs, photoblogs, sketch blogs, audio blogs, and video blogs (vlogs in short).

Vlogs have been widely used for e-learning [39], citizen journalism [23], product marketing [17], and daily interaction with family and friends [22]. Another emerging area is health vlogs, in which individuals with health conditions share their stories with others. Sharing personal experiences with others has been proven to be helpful for peer-support, especially for those who have chronic illness [3]. The connection between the vlogger and the viewers is critical in health vlogs as past literature has shown that social support or connections with others work as self-therapy [36]. Despite the apparent advantages in further developing health vlogs, few studies have explored ways to improve patients’ connections with others in health vlogs.

In this paper, we present our study on chronic illness patients’ use of health vlogs on YouTube. We examined how health vloggers attempt to connect with viewers and identified different genres of health vlogs. We then discuss the affordances that video provides as a blogging tool, and the challenges vloggers’ face in practice. Finally, we discuss implications for the design of health vlogging tools.

RELATED WORK

Video sharing sites such as YouTube, Vimeo, and DailyMotion are affordable, accessible media production sites where amateur video producers can share their messages with a worldwide audience. People use vlogs for various purposes, ranging from daily personal diaries to informal music learning [42] to health communication [8].

Studies have shown that vlogs are useful in a wide variety of domains. For example, rural Brazilian communities adopted vlogs to empower citizen journalism and build self-sustainable telecommunication centers [9]. The D/deaf community also uses vlogging as an alternative medium for rich communication [15]. Raun discussed vlogs as a Do-It-Yourself (DIY) Therapy [30], where vlogs have become an arena for “truth telling” as seen in self-help groups and political gatherings [41] and “confession,” a mode of governance [10]. Vlogs often carry the forms of personal speaking to invisible listeners, and conducting such an activity can help the speaker feel better [24].

Some studies have investigated the use of vlogs in the domain of health. Molyneaux and O’Donnell [26] found that participants reported high levels of interest in watching user-generated video as a source of awareness and learning around health information. The Kaiser Family Foundation also uses vlogs to target young people about the impact of HIV. The young people get to hear first-hand how HIV has affected people their age and how they can prevent or test for HIV [16]. While Chou et al. [6] looked at cancer vlogs on YouTube to understand what made a cancer narrative effective, many of these studies do not examine the connection between the vlogger and the audience.

Blogging

Sundar et al. [35] discussed how seminal work around virtual worlds [40] and blogging and identities [27] bleeds over to help understand the motivations and benefits of health blogs. Nardi et al. [27] discussed five general motivations for blogging: autobiographical narratives, commentary, catharsis, muse, and community forum. Bloggers telling the story of their lives for catharsis can be particularly important for people dealing with a mental illness because telling one’s life story “can renew a sense of meaning and possibility” [33].

Similar to vlogs, relatively few studies have examined health blogs as an independent genre. Miller and Pole [25] showed that half of 951 health blogs published between 2007 and 2008 were written by health professionals, one third by patients, and a few by unpaid caregivers. Previous research has shown that cancer patients benefit emotionally by sharing their experience with other patients through blogs [7]. Many bloggers also explored multiple identities through blogging.

It is unclear how much the results around blogs apply to health blogs on other diseases not necessarily dominated by emotional problems (e.g., diabetes), highly stigmatized (e.g., HIV), or often terminal (e.g., cancer). Although much of what we know about blogs and virtual worlds will carry over to health vlogs, the video medium affords high personal information disclosure and suggests new kinds of phenomena around health vlogging. Though Ressler et al. [32] found that blogging about chronic pain and illness helped patients feel less of an isolation because of the online connection, Nardi et al. [28] found that bloggers were not interested in “holding any but a minimal conversation” between their readers. However, this may hold differently for health vlogs due to the affordances of video. Furthermore, few studies have explicitly examined design issues around health vlogging tools.

Presenter and Audience

Goffman suggests the concept of presentation of self [13]. If we consider vloggers to be similar to an actor on a stage, and a vlogger’s viewers as their audience, the goal of the presentation is acceptance from the audience. Essentially, if the actor has succeeded in the presentation, the audience will see the actor as the actor intended. This idea of self-expression and self-representation is one of the affordances that vlogs offer. However, there has been little work in examining the interaction between the vlogger and the viewers and the affordances that vlogs allow.

Social Support and Self-Therapy

According to Thoits, social support is defined as a social “fund” that people draw from when handling stressors [37]. Social support can include help in material aid, behavioral assistance, intimate interaction, feedback, and positive social interaction [1]. Many studies have shown the importance of social support for anyone [2]. However, with chronic illnesses, the feelings of isolation can be exacerbated [5], and thus social support becomes essential.

Giving support to others has been shown to help the patients themselves as well; helping others creates a type of self-therapy. One study looked at elderly patients and found that those who gave informal assistance to others reported enhanced feelings of personal control [19]. Similarly, another study suggested that women who were abused saw the ability to provide help to others as proof of their own recovery [14]. Schwartz and Sendor suggested that peer supporters (those who provided support to people with the same disease) were able to reframe their disease experience, resulting in an enhanced perception of quality of life [34].

A few video resources for social support are available to the public1,2. Although these examples are considered health videos, they are curated by an organization, and in some cases, use actors rather than the patients. Instead, we were interested in understanding health videos that patients generated and maintained, particularly to explore self-therapy or to help others.

Building on existing work, we examine how health vloggers attempt to build a viewer connection as a form of self-therapy and social support. We also examine remaining challenges and suggest potential design features.

METHODS

Data Collection

To examine health vloggers who post a series of health vlogs, rather than a one-time vlog, we studied health vlogs on three chronic diseases that require self-management activities over time: HIV (human immunodeficiency virus), diabetes, and cancer, though cancer is not always a chronic disease. We chose these three diseases because they have a high prevalence in the world for us to be able to collect a reasonable amount of data, differ in ways in which self-management strategies are formed and maintained, and have different levels of social stigma.

We considered all forms of diabetes, and we did not distinguish cancer types. Because YouTube did not have a specific health category, we utilized YouTube’s search mechanism by using the keywords “<disease name= blog” to get the search results. We received 2500, 2090, and 12900 search results for diabetes, HIV, and cancer, respectively. We narrowed down the list to a set of vloggers who we considered health vloggers using the following inclusion criteria: (1) The vlog title contained words directly related to diabetes, HIV, or cancer. Examples include “blood sugar” for diabetes, and “chemotherapy” for cancer; (2) Either verbally in the video or written in the caption, the vlogger confirmed that he/she was diagnosed with the illness; (3) The vlogger was the diagnosed patient him/herself and not an institution or organization. We chose these criteria because many videos uploaded by an institution are professionally edited, but we were more interested in looking at amateur vloggers.

We reached data saturation after 36 vloggers (the first 12 vloggers for each disease). For each vlogger, we analyzed their first and last health vlog posted (72 vlogs total). Certain characteristics of the vloggers (e.g., all HIV vloggers were homosexual males) were a result of the selection process. Table 1 shows more information on each disease vlog group. We changed names of the vloggers throughout the paper.

Table 1.

Descriptive data for each category of vloggers. Values are the Median (Min/Max) per person.

| HIV | Diabetes | Cancer | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 12M | 9M/3F | 8M/4F |

| Age (Min/Max) | 27 (21/51) | 33 (15/75) | 38 (25/49) |

| Videos per person (Min/Max) | 46.5 (2/150) | 14 (2/1027) | 23 (6/197) |

| Views per person (Min/Max) | 14,808 (258/341788) | 5,441.5 (570/313235) | 14,808 (258/341788) |

| Subscribers (Min/Max) | 232.5 (1/1457) | 21 (4/405) | 22.5 (1/505) |

Analysis

Each of three coders separately analyzed 6 videos for each disease, resulting in 18 videos of 9 unique users in total to develop descriptive codes as a group. The resulting descriptive codes focused on the following attributes: basic information about the vlog (title, post date, vlog length, caption), demographical information about the author, medical information about the author (disease timeline, emotional stage), visual information (video editing, scripted, location), and other information that describes the different styles of authors’ performance and attitude, as well as the way stories are presented (attitude, message of the video, intended audience, purpose).

Next, we used open coding to analyze 18 more videos each, for a total of 54 in this round (72 in total, including the 18 to develop coding). We iteratively developed our coding schemes by continuously revising the coding scheme as a group, merging them, and then generating subsets of codes as we found common and contrasting themes. Through our analysis, we identified relevant themes that emerged from both the descriptive codes and the open coding schemes. The three coders then came together to perform an affinity diagram analysis.

RESULTS

In this section, we describe how vloggers used vlogs as a medium to connect with their viewers as a form of self-therapy while helping others. We first discuss different genres that vloggers devised to convey specialized messages to the viewers. We then discuss how video affords richer viewer connection than text-based media. Lastly, we discuss various methods that vloggers used to explicitly interact with viewers.

Health Vlogging Genres

Vloggers produced different genres of vlogs, depending on the stage they were in, their illness trajectory, the chronic illness they were suffering from, and their purpose for vlogging. The different genres, discussed below, reflected the messages vloggers wanted to convey and how they wanted to present their messages to the viewers.

Teaching

In teaching vlogs, vloggers attempt to educate viewers with information about their illness and management strategies. Vloggers typically created teaching vlogs with content highlighting their own knowledge and experience. Teaching vlogs allowed vloggers to cast themselves as an expert to viewers in what they do.

More of the diabetes vlogs in our study were for the purpose of teaching (42%), compared to vlogs for the other illnesses—HIV (13%) and cancer (17%). For diabetes management, self-education is critical. Because diabetes is a chronic illness that can be managed through diet and personal lifestyle, many diabetes vloggers offered suggestions to viewers. Examples included eating certain types of food, such as cinnamon (DIB12a) or a particular brand of pasta (DIB8b), or advocating for a lifestyle change, such as a vegan lifestyle (DIB9a). Thus, one would expect that many diabetes vloggers would attempt to teach strategies and solutions that others could use.

In teaching videos, vloggers shared information on characterizing their illness and strategies to manage the illness. For example, Anthony wanted to distinguish between Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes, by giving an overview of the differences:

“When people talk about diabetes, they’re almost always thinking that it’s diabetes Type 2… For me, I'm Type 1 so… we just don't produce insulin…But for Type 2 diabetics, they could have complete insulin resistance, so that's a whole other thing.” (Anthony, DIB5b)

We observed frequent “show-and-tell” behavior throughout the teaching videos, which is difficult to convey through text-based blogs. For example, vloggers demonstrated how a device worked, how to cook low-carb meals (DIB4a, DIB7a), or how to replace gauze on open wounds (CAN12a). One diabetes vlogger explained that he had a heart monitoring device and said, “I have electrodes attached to my chest” (DIB4b) before showing how the heart monitor device worked. John showed how he got blood tests done (HIV4a). Vloggers also used hand descriptions to show the size of a swollen testicle using their index finger and thumb (CAN6a) or where and how long in length the stitches were (CAN4b).

Vloggers also used a mixture of video recordings, still images, and hand drawings to present informational material. As shown in Figure 1, Sue created a scenario and rendered it on a still image, which was then inserted into her vlog as teaching material (DIB1b). Similarly, Figure 2 shows another vlogger explaining how uterine cancer affects pregnancy by drawing a diagram on paper (CAN7a).

Figure 1.

A scenario created by a health vlogger was to teach viewers everyday strategies for diabetes management.

Figure 2.

A drawing by a cancer vlogger showed and explained how uterine cancer could affect pregnancy.

Personal Journals

One of the most common genres of videos was a personal journal. In this genre, vloggers gave updates on their current emotional and physical status or experiences during major stages in their illness trajectories. According to Raun, by sharing such day-to-day changes, vloggers can create a sense of connection with others and reflect upon themselves, working as a therapeutic activity [30].

Many vloggers included current updates to their treatment and shared their thoughts and feelings, akin to a written diary. Some vloggers explicitly mentioned that the goal of their vlog was to serve like a journal (CAN1a, CAN8a). Other vloggers not only gave updates on their disease, but also on their personal lives. In one case, Andy, a diabetes vlogger explained that his video was to update his viewers about the results of his daughter’s diabetes test as negative (DIB10b). Other vloggers updated their medication practices. Nick updated his viewers about his experience with a new medication:

“Today’s the first day I took the medication, and it’s Complera….I’m very nauseous…pain in my chest…stomach is a little hurting.” (Nick, HIV8a)

Sharing such day-to-day experience provides viewers with information about the medication while also building personal connections with consistent followers.

HIV vloggers, compared to other vloggers, tended to be more reflective, sharing their revelations and acceptance of having HIV. Matthew reflected on why he might have contracted HIV: “I love people more than myself – that’s probably one of the reasons I got HIV” (Matthew, HIV1a).

In one case, Blake stated that he was struggling with accepting HIV in his life. He also said that he felt that everyone was constantly judging him, even strangers. Finally, he came to an epiphany on living with HIV and shared it with the viewers:

“[HIV] was owning me. It was taking over…I was so tired of it wearing me down. And I say ‘was’ because I had this epiphany. I was just like…don’t let it own me, own it. How do I do that? Hmm. Personalize it maybe? Own it. Meaning, it’s yours. HIV—the Human Immunodeficiency Virus or BIV—the Blake Immunodeficiency Virus. That’s when it hit me; I don’t have HIV. I have BIV! Own it, bitch!” (Blake, HIV10b)

Viewers for Blake’s video commented that it inspired them greatly, thanking him. Steven, another HIV vlogger, began reading a letter he wrote to HIV:

“I can only blame me, not you, for coming into my life. Since our relationship began, I focused on what I lost, and neglected to see what you’ve actually given me – my life…” (Steven, HIV6b)

Through this letter, Steven was able to share how he integrated HIV as part of his life with his viewers. His interesting approach on speaking directly to HIV, as if it were a person, triggered thanks from the viewers, and many agreed with his thoughts.

Many personal journals used a stylistic format of a talking head, only featuring the author and their head. This style follows the idea of virtual social proxemics [29] and other work that has shown that the size of the image often affects the interaction of a videoconference [11]. Yet, unlike remote videoconferencing, vlogs are one-sided. Vloggers are not able to get immediate feedback from their audience.

Vloggers discussed how they were feeling, current updates, or past experiences using this style. Many would also share past experiences with the audience. In one example, an HIV vlogger explained his initial experience after his diagnosis, “There were times in my life I got really involved in drinking, and I just wanted to forget about life. I wanted it to end” (HIV1b).

Often, vloggers would also take the opportunity to plead for viewers to take action. In the case of HIV, Dan begged viewers to get tested if they hadn’t already and to be safe and protected. He repeatedly said, “It’s not worth your life…yes, I’ll live to a ripe old age, but how long will I live? I don’t know” (HIV7a). A cancer vlogger shared her past experience before getting diagnosed with uterine cancer, explaining some of the symptoms that showed up. She urged viewers that if they were experiencing any of these symptoms to “please go see a doctor to make sure you’re fine and that this is not happening to you” (CAN7a). From these pleas, vloggers are able to show their concern and care for viewers, thus potentially increasing the connection between the vlogger and the viewers.

Self-Documentaries

Vlogs have the ability to capture situated, in-the-moment information that traditional text blogs cannot. Vloggers took advantage of this capability and allowed their viewers a glimpse into their highly situated experiences.

For instance, Sean, audio-recorded a confirmed diagnosis with his doctor, providing subtitles against a black screen. Although the viewers could not see the video of what was happening, the audio, together with the subtitles, intensified the delivery of what happened inside the clinic.

Beyond clinics, vloggers took the camera with them as they participated in various events. Jen had her husband film her during a triathlon (CAN3b). Another vlogger filmed his time at an AIDS conference (HIV9b). One vlogger brought his camera with him as he finished a military-like 5K run (HIV12b). Bringing the camera and allowing the viewers to get a peek into their lives, regardless of whether the content was directly related to the illness or not, allows moments of connectedness between the vlogger and the viewers.

Video Compilations

Vloggers also used creative ways to inspire and encourage their viewers by compiling video portraits of people sending positive messages. Although they were patients, the vloggers in these genres were not the main information givers of the vlogs, but rather, information gatherers.

Video compilations helped create a sense of community with those who are going through the same illness. For example, one diabetes vlogger uploaded a video that simply contained messages from people who attended a diabetes conference, saying their name, how long they have had diabetes, and “you can do this!” or “I’m Type Awesome!” (DIB3a) As written in the caption of the vlog, the purpose of this vlog was to give support to those struggling with living with diabetes.

In another vlog, Nicole started off by dancing and then explained that her friend’s daughter who had Type 1 diabetes was about to get glasses, but was worried that people might make fun of her for wearing glasses and an insulin pump. Nicole said to the camera, “So this video is for her, and I have a few friends that want to help me…c’mon guys!” (DIB3b) and showed a slideshow of both photos and video clips of more than 50 people who were wearing both insulin pumps and glasses.

Some vloggers brought their viewers back into their vlogs for further inspiration for others. For example, Sean compiled videos sent from other viewers into a series. He introduced the series by saying,

“Several people have emailed me because the blog has touched people in so many different ways, so I’m providing an opportunity for people to tell their stories… how they became positive.” (Sean, HIV5b).

Here, the vlogger actively engaged his viewers through his vlogs, which in turn connected him with his viewers.

The Affordances of Video

Vlogs allow a form of presentation that traditional text blogs do not allow. Vloggers used cameras to film themselves talking, show their cats, capture real-time moments, use animations, demonstrate how to do things, or make picture slide shows. This high level of customization enabled vloggers to take control of their vlogs’ presentation and content, which is a means for self-expression [38]. In the following, we discuss several affordances of video, including non-verbal cues, other actors, and context filming as ways vloggers took control of their vlog presentation.

Nonverbal Cues: Connection and Building Rapport

Nonverbal cues are typically visual cues without words. We observed our vloggers trying to build personal connections and rapport with viewers through their nonverbal cues, such as pausing, crying, or giving facial expressions.

Subtle but powerful pauses in speaking can create a range of emotions that vloggers and viewers can share. Jen, who wanted to express how much compassion she had for another cancer survivor’s video, looked directly into the camera and paused for ten seconds, occasionally sniffing to hold back tears and said “I feel closer to you now that I know your family history” (CAN3a_0). Similarly, Felicia, another breast cancer survivor continuously suppressed her tears as she shared her update:

“As much as I don’t want to deal with that, I understand that I have to because it is part of my journey. <pauses and sniffs, sighs> But um, I’m really, really grateful <sniffs, looks down, pauses> that the surgery was a success <clears the throat>. I’m really grateful that I am cancer free.” (Felicia, CAN4b)

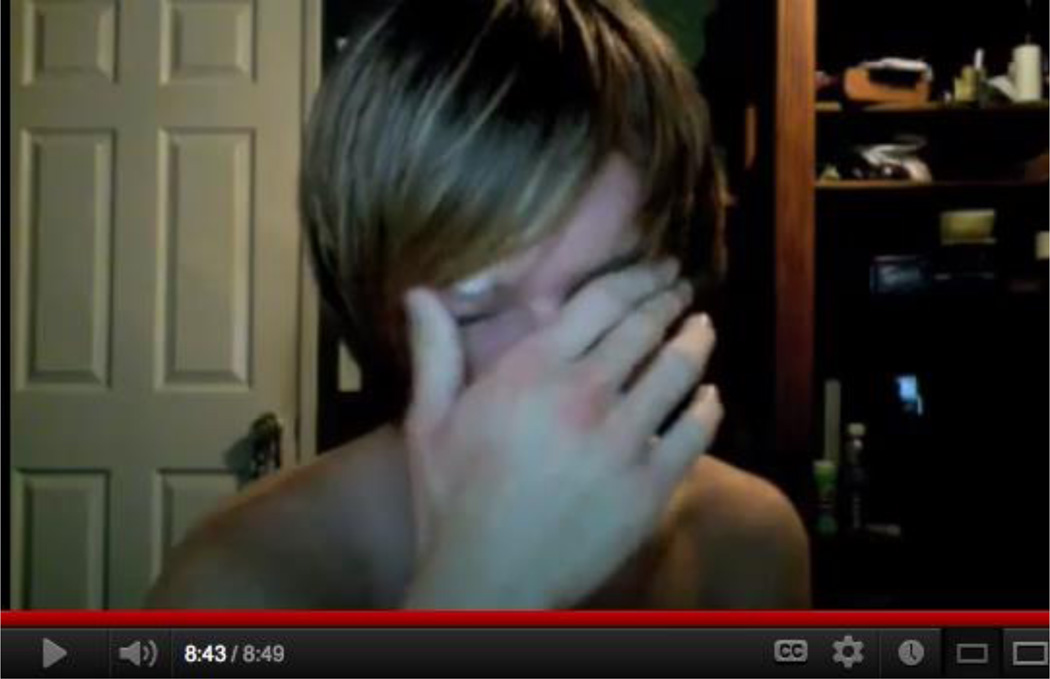

Blake wanted to share his emotional state at the time of diagnosis as HIV positive with his viewers (HIV10a). He paused, glanced, gave emotional expressions, and eventually sobbed (Figure 3), which helped create a personal connection that would have been hard to do with traditional text-blogs.

Figure 3.

Blake (HIV10a) wiped away tears as he shared his experience about being newly diagnosed with HIV.

The vloggers also used humorous expressions to build rapport with the viewers. John wanted to show how regular blood work for HIV patients is done. He asked the nurse to explain the purpose of blood work, blood containers, and then the needle, to which he changed the camera angle to show his face humorously frowning (HIV4a). Eric, a cancer vlogger, adjusted his webcam while making a silly face at the camera (CAN2a).

Most importantly, for highly stigmatized diseases such as HIV, disclosing one’s face, name, and family history in front of a worldwide audience can be quite intimidating. Yet, the vloggers used this disclosure to create intense and personal connections with the viewers.

Other Actors

Another unique component we saw from vlogs was incorporating more than one actor in the scene. These actors included significant others (CAN3b, HIV7b), pets (CAN2b, CAN3a), or health care providers (CAN6b) who provided further context about the vloggers and their situation.

Other actors participated in vlogs to send messages for the vloggers when the vlogger was not available (CAN1b, CAN3b), broadcasted events in the moment as vloggers participated in those events (CAN3b, HIV4a), or became the ambiance of the video that added meaning to the message being delivered to the viewers (HIV7b, DIB7b).

For instance, the goal of Dan’s vlog was to deliver a teaching message on what to do after having unprotected sex with someone who is HIV positive. In this video, Dan’s partner, who is HIV negative, was sitting beside him. The caption of the video says:

“If you think you may have been exposed to HIV or a condom has broken or if you are having unprotected sex, please watch this as this video was done by my partner who is HIV negative and I thank him for his courage…he is amazing” (Dan, HIV7b)

Having an HIV negative person disclose their face with an HIV positive partner can be a highly stigmatized activity. This strengthened Dan’s delivered message of safe sex.

In Sean’s video, his doctor was present, though only through voice. As a form of self-documentary, Sean captured the moment of being diagnosed, shocked by his doctor’s words that Sean had a large viral load (HIV5a).

Doctor: “It’s a positive viral load…you expected that.”

Sean: “I did?”

Doctor: “So…your viral load right is like, a 5,517,000.”

Sean: “5 million? Oh my god. Wow, okay. I was hoping for, like, 12.” (Sean, HIV5a)

The next scene shows Sean’s concerned face outside the hospital, telling the camera that he is now flying home to tell his parents about the diagnosis. In the vlogs, Sean showed himself as being nervous but trying hard to stay calm and positive.

Using the voice exchange with his physician in the video, the emotional progress, and externalization of his inside voices, Sean was able to capture his fear, anger, sadness, and surprise in that moment.

Context-Filming

Videos have a great ability to capture “in-the-moment” without needing to describe them in text. The most frequent background in vlogs was the vloggers’ rooms, especially the back wall behind the vloggers’ talking head. In this case, viewers would then focus on the message being delivered by the vlogger. However, once vloggers began to push the boundaries of where the vlog was filmed as well what their appearance was, richer context began to add onto the vlogs. Furthermore, they began adding rich context to augment and intensify their messages to viewers.

For instance, Ted filmed his first vlog at home in his room, but his last video titled"My HIV Life ‘Obstacles’”, showed himself in front of a red brick wall. He explained that the red bricks were a symbol of strength because they stayed the same throughout any obstacle: “I wanted to intentionally film in front of the red brick wall, so that we all get over obstacles for a reason and to stay strong.” (Ted, HIV3b)

Background transitions in vlogs also helped vloggers effectively convey context. Paul started his cancer vlog by describing his synovial sarcoma and history with the hospital waiting room as his background. As he progressed through the hospital visit, the backgrounds changed from the waiting room to the hospital room, where he was getting his chemotherapy, and then back home. During this transition, he walked through his medical history, current status, and remaining treatments to be done. In the vlog, he gave small show-and-tells, for instance, explaining specifics of how the warm blanket around his arm allowed for easier IV insertion and then showing his arm with the IV inserted (Figure 4). Such show-and-tells, tied with a hospital setting as a background, was Paul’s choice to deliver his context more effectively to his viewers, as he noted, “Once they call me in, I’m just going to go over the different things that they do in the chemo room” (Paul, CAN9a).

Figure 4.

Paul (CAN9) showed viewers what his IV insertion looked like.

Vloggers also captured their vulnerable appearance to inspire others and to help them learn. Ely, a brain tumor patient, filmed himself in a vulnerable state, while lying in a hospital bed with a nasal cannula and wires around him. He then stated, “I wanted to take my experience as a photo journalist to help people learn from my tragedy” (CAN11a). Similarly, Tom presented himself as vulnerable and not willing to live, filming himself in bed 7 days after his diagnosis of HIV. He repeatedly stated, “I refuse to participate in this world” (HIV2a). In contrast, a year after the initial vlog, he posted a photo slideshow as part of his HIV vlog series, where he was standing in front of the White House holding up a picket saying, “I am HIV+” along with pictures of him and many supporters smiling.

One of critical elements in peer patient support is sharing emotional experience situated in context [20]. Through health vlogs, vloggers brought an intense personal connection to the viewers, through nonverbal cues and enriched context of major illness events using other actors and background context. Accordingly, health vlogs are particularly useful for peer patient support. At the same time, not only peer patients but any individual interested in the health problem, such as undiagnosed patients or care providers, could learn about the disease from health vlogs more thoroughly than through traditional text-based blogs.

Requesting Viewer Interaction

In contrast to the implicit methods for vloggers to establish viewer connection that we just described, in this section we describe explicit methods used to request viewer interaction and build a connection with viewers.

Vloggers also sought viewer interaction by verbally responding to comments or certain groups of viewers. In one example, Roger used his vlog to address his reaction to a certain group of his viewers:

“All of you HIV denialists that keep hitting me up and keep leaving comments on my channel…stating that I am misinformed, informing me how HIV is nothing but some kind of scam that was cooked up by the government and Illuminati…I appreciate what you guys are doing, but I will frankly have to say, carry that bullshit to someone else’s page…I don’t want to hear that…” (Roger, HIV11b)

Other vloggers solicited viewers’ interactions by requesting comments or questions. Anthony ended his video with the following message to explicitly request interaction: “If you have any comments or questions, go ahead and shoot it back to me, and I'd be more than happy to answer that” (Anthony, DIB5a).

Another vlogger encouraged his viewers to help guide the direction of future videos by saying, “If you see this, comment on it. I’ll try to add more as I go on” (CAN5a). Others asked the viewers to correct them if they gave out incorrect information, using the viewers as gatekeepers. For example, Anthony said, “Questions, comments, you want to call me out on something? Maybe I got something wrong? Maybe I got lots of things wrong” (DIB5b).

These types of interaction requests were fairly common for many of the vloggers, but some tried to engage their viewers in a unique way to spark further interaction. Carl, a diabetes vlogger uploaded a vlog about a prize giveaway:

“Just leave a comment on this post that includes the words ‘Bacon Wrap My Pump’, and you can be one of six lucky winners of this sweet bacon skin for your Medtronic insulin pump!” (Carl, DIB6b)

Some vloggers provided a way for viewers to communicate by providing external links such as to their Facebook, Twitter, email, website, and even a phone number. Steven, for instance, wrote his phone number and email address on a piece of paper and showed it to the camera, telling the viewers to contact him if they need help (HIV6a).

DISCUSSION

Our results show that health vloggers use a variety of implicit and explicit ways to create a connection with their viewers. Below, we discuss how the vlogger-viewer connection is critical for two main motivations in health vlogging: self-therapy and helping others.

Self-Therapy

Many vloggers stated that they created vlogs for their own benefits. Some mentioned that vlogging was something their psychiatrist recommended, while others just hoped that it would help them in some way. Nonetheless, the self-therapeutic aspect of health vlogs was not confined to helping oneself. As vloggers mentioned in their vlogs, having the added benefit of helping others while helping themselves gave vlogging a greater purpose than a means to indulge in narcissism [12]. Although there was usually no validation that their vlogs had helped anyone, knowing that there was the potential helped many vloggers.

Particularly for the vloggers with diabetes or HIV where the illnesses were dependent on self-management strategies, creating vlogs helped hold the vloggers accountable for their actions. If vloggers stated a plan of action or even suggested their viewers to act upon a plan, vloggers would then be expected to follow suit.

Helping Others: Dealing with the Invisible Audience

Many vloggers also stated in their vlogs and captions that their main purpose was to help others by inspiring them and teaching them with the expertise they gained over many years. In our findings, we discussed altruistic motivations playing into teaching and personal journal vlogs. Many explained that they wanted to share their experiences with those who were recently diagnosed or were struggling with their illness because vloggers did not receive the right kinds of help when they needed them.

However, the interpretation of “helping others” varied. In personal journal vlogs, some vloggers believed that speaking freely to the camera about what was on their mind would be helpful to others. As shown in the teaching vlogs, others took an educational route by including tangible strategies and solutions that could be useful to viewers.

Although vloggers explicitly mentioned helping others as one reason for creating vlogs, we did not find much evidence that they received confirmation from their viewers saying that it was helpful, unless viewers contacted vloggers through comments or private messages. This notion of an invisible audience, where vloggers do not have any knowledge of their viewers, was observed throughout many of the vlogs. For example, Dan, an HIV vlogger said:

“[If] one person listens, and one person doesn't catch this chronic illness…I'll never meet you–whoever you are–then, I'll sleep better tonight.” (Dan, HIV7a)

For vloggers, simply believing that they helped others gave them a sense of peace, perhaps, serving as self-therapy too. At the same time, as we discussed in requesting viewer interaction, some vloggers attempted to gain explicit feedback from their viewers. The attempt to explicitly connect with viewers may have been vloggers’ struggle to grasp their invisible audience into companions, whom vloggers can consider as partners of social support.

DESIGN IMPLICATIONS

Health vloggers experienced challenges in their attempts to interact with their viewers. Below, we walk through those challenges and discuss design implications.

Allowing Personalized Presentation and Message Delivery

Health vloggers used nonverbal cues to enable intense personal connection with their viewers and used various genres to convey their messages more effectively. Current vlogging systems underexplore using vloggers’ nonverbal cues as information resources or giving vloggers the ability to tailor presentation and deliver of vlogs. Health vlogging systems have the potential to use new signal processing techniques to record metadata about the frequency and quality of nonverbal cues (e.g., [4]). Machine learning techniques could be used to determine metadata features automatically. Using this metadata, systems could inform vloggers about their use of nonverbal cues and their potential impact on viewers’ interpretation of the vlog. Systems could also suggest vlogs based on this metadata to viewers who are looking for intense personal connection more so than informational content. However, with current technologies, searching for content and style is much easier to do in text than in video. This search challenge indicates an important gap that requires further research.

Currently, the quality of presentation depends on the vloggers’ technical knowledge and software. Health vlogging systems can provide users with templates to help users create various genres and style of presentation. For instance, for vloggers who want to teach disease management strategies, the wizard can provide templates to use images, pointers, and screen shots. The wizard can also provide ideas for presenting and delivering messages using examples from other vloggers. Health vlogging systems can also support the creation of vlogs through mobile devices, letting users create and upload videos in the moment.

Supporting Distinct Disease Characteristics

About social stigma

Because of YouTube’s open and public nature as well as the identifying characteristics of video and audio, vloggers must be willing to make a public disclosure. HIV vloggers in our study intentionally disclosed their diagnosis to the worldwide audience as a tool to overcome social stigma. However, all the HIV vloggers we studied were homosexual males, implying that the stigmatization of the disease still prevents some from vlogging about their disease thereby limiting the amount of self-therapy they can receive by using this helpful media.

Health vlogging systems could allow vloggers to customize the level of disclosure. YouTube currently offers an option called Xtranormal Movie Maker3 which allows the vlogger to “set up [a] scene, type in [a] script, and animate it instantly.” This feature lets the vlogger share their story and experience without having to fully disclose their face, voice or name. Yet, we did not observe any of the vloggers in our study using this feature. Furthermore, the system allows vloggers to generate a “mask” to hide facial features or to upload only voice with photo slideshows or even blank screen with titles. Systems could further utilize this feature to allow vloggers to restrict personal information and encourage those who are wary to share their experiences.

About differing content

Vloggers used different genres depending on the stage of the disease and emotional state., In turn, these genres created different kinds of interaction. Diabetes vlogs used graphic tools to present workable self-care strategies, whereas vloggers attempting to inspire the newly diagnosed used nonverbal cues, such as crying or sharing raw footage of the time of the diagnosis.

Providing additional information or resources to viewers is not something that is as well supported by current vlogging systems. YouTube allows the vlogger to write a description below the video, but information can sometimes get lost if there is too much of it. To address this problem, health vlogging systems could create a sidebar by the vlog where vloggers can add information at specific timestamps. The information could be about chapters in their teaching messages, stages of illness trajectory, their personal history, resources they might have mentioned, or points of nonverbal cues that viewers can use either to skim what the vlog is about or to “fast-forward” to the moment of their interest. This feature provides more related content to the viewer. It also allows the viewer to search for or scan and choose what segments of the video they are interested in, instead of having to watch the entire video.

Providing Sustainable Viewer Connections

In online communities, members have sustained relationships and reciprocity in sharing experiences and information. However, we saw little of such vlogger-viewer interaction happening in YouTube. The only viewer interaction mechanisms that YouTube support are commenting and voting features. Because the current organization allows for vloggers to interact with a general audience, vloggers can be attacked by harsh comments [21]. This also does not promote long-term connections with viewers. Health vlogging systems should be able to facilitate sustained viewer engagement and community. A variety of modalities could help accomplish this goal. Integrating asynchronous video-based communication systems, such as VideoPal [18], into health vlogging systems could help sustain viewer connection and generate a sense of community. Viewers could leave comments inside particular segments of the vlog. Viewers could also utilize video as a way to communicate back to the vlogger. Systems can record information about participants in these comments to profile users, which then can be used to suggest viewers and vloggers into vlogs or topic based communities within the health vlogging tools. The system can further support local meet ups, virtual gatherings, and suggestions of advocacy and fundraising events.

CONCLUSION

Health vlogs allow individuals with chronic illnesses to share their experience, knowledge, and stories with others. Connections among patients, such as those between vloggers and their viewers, have shown to be a form of social support and are self-therapeutic for health vloggers. However, little has been done in trying to sustain and strengthen health vloggers’ connections with their viewers.

We presented the results of a qualitative study to understand how health vloggers attempt to connect with their viewers as a form of self-therapy and social support. Our results show that health vloggers use the uniqueness of video as a way to create rich and strong connections. Vloggers also use specific genres and other explicit methods to communicate personalized messages and connect with their viewers. Based on the results of our study, we presented design implications to improve and provide more sustainable viewer connections. By supporting and encouraging the vlogger-viewer connection, new technologies can enable health vloggers to help others while helping themselves.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by the NIH NLM training grant (2T15LM007442). We also thank the iMed research group, Gillian Hayes, Norman Makoto Su, and Patrick Shih for their valuable feedback on previous drafts.

Footnotes

Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation on the first page. To copy otherwise, or republish, to post on servers or to redistribute to lists, requires prior specific permission and/or a fee.

Contributor Information

Leslie S. Liu, Email: lsliu@uw.edu.

Jina Huh, Email: jinahuh@uw.edu.

Tina Neogi, Email: tneogi@uw.edu.

Kori Inkpen, Email: kori@microsoft.com.

Wanda Pratt, Email: wpratt@uw.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barrera M, Ainlay S. The Structure of Social Support: A Conceptual and Empirical Analysis. Journal of Community Psychology. 1983:133–143. doi: 10.1002/1520-6629(198304)11:2<133::aid-jcop2290110207>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biemans M, van Dijk B, Dadlani P, van Halteren A. Let’s Stay in Touch: Sharing Photos for Restoring Social Connectedness between Rehabilitants, Friends, and Family. In Proc. SICACCESS’09. :179–186. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brubaker J, Lustig C, Hayes GR. PatientsLikeMe: Empowerment and Representation in a Patient-Centered Social Network. CSCW’10; Workshop on Research in Healthcare: Past, Present, and Future [Google Scholar]

- 4.Byun B, Awasthi A, Chou PA, Kapoor A, Lee B, Czerwinski M. Honest Signals in Video Conferencing. In Proc. ICME'11. :1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charmaz K. Loss of Self: A Fundamental Form of Suffering in the Chronically Ill. Journal of Sociology of Health and Illness. 1983:168–195. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.ep10491512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chou WS, Hunt Y, Folkers A, Auguston E. Cancer Survivorship in the Age of YouTube and Social Media: A Narrative Analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2011 doi: 10.2196/jmir.1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung DS, Kim S. Blogging Activity Among Cancer Patients and Their Companions: Uses, Gratifications, and Predictors of Outcomes. JASIST. 2008:297–306. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandez-Luque L, Elahi N, Grajales FJ., III An Analysis of Personal Medical Information Disclosed in YouTube Videos Created by Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. Studies in Health Technology Information. 2009:292–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Figueiredo MA, Prado P, Camara MA, Alburquerque AM. Empowering Rural Citizen Journalism via Web 2.0 Technologies. In Proc. C&T'09. :77–84. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foucault M. The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1: An Introduction. Éditions Gallimard. 1978 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grayson D, Coventry L. The Effects of Visual Proxemic Information in Video Mediated Communication. SIGCHI Bulletin. 1998:30–39. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffith M, Papacharissi Z. Looking for You: An Analysis of Video Blogs. First Monday. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goffman E. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Anchor. 1959 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henderson A. Abused Women and Peer-Provided Social Support: The Nature and Dynamics of Reciprocity in a Crisis Setting. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 1995:117–128. doi: 10.3109/01612849509006929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hibbard ES, Fels DI. The Vlogging Phenomena: A Deaf Perspective. In Proc. ASSETS'11. :59–66. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoff T, Mishel M, Rowe I. Using New Media to Make HIV Personal: A Partnership of MTV and the Kaiser Family Foundation. Cases in Public Health Communication & Marketing '08. :190–197. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffman DL, Fodor M. Can You Measure the ROI of Your Social Media marketing? MIT Sloan Management Review. 2010:41–49. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inkpen K, Du H, Roseway A, Hoff A, Johns P. Video Kids: Augmenting Close Friendships with Asynchronous Video Conversations in VideoPal. In Proc. CHI'12. :2387–2396. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krause N, Herzog AR, Baker E. Providing Support to Others and Well-being in Later Life. Journal of Gerontology. 1992:300–311. doi: 10.1093/geronj/47.5.p300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurtz LF. Self-Help and Support Groups: A Handbook for Practitioners. Sage. 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lange PG. Commenting on comments: Investigating responses to antagonism on YouTube. Conference of the Society for Applied Anthropology '07. :1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lange PG. Publicly Private and Privately Public: Social Networking on YouTube. Journal of CMC. 2008:361–380. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Markham T. Hunched Over Their Laptops: Phenomenological Perspectives on Citizen Journalism. Presented at MeCCSA'10 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matthews N. Confessions to a New Public: Video Nation Shorts. Media Culture Society. 2007:435–449. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller EA, Pole A. Diagnosis Blog: Checking Up on Health Blogs in the Blogosphere. American Journal of Public Health. 2010:1514–1519. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.175125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Molyneaux H, O'Donnell S. Patient Portals 2.0: The Potential for Online Video. In Proc. COACH'09. :1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nardi BA, Schiano DJ, Gumbrecht M, Swartz L. Why We Blog. Communications of ACM ‘04. :41–46. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nardi BA, Schiano DJ, Gumbrecht M. Blogging as Social Activity, or, Would You Let 900 Million People Read Your Diary? In Proc. CSCW'04. :222–231. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olson GM, Olson JS. Distance Matters. HCI. 2000:139–178. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raun T. DIY Therapy: Exploring Affective Aspects of Trans Video Blogs on YouTube. Palgrave Macmillian. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Renov M, Suderburg E. Resolutions: Contemporary Video Practices. University of Minneapolis Press. 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ressler PK, Bradshaw YS, Gualtieri L, Chui KKH. Communicating the Experience of Chronic Pain and Illness Through Blogging. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2012 doi: 10.2196/jmir.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ridgeway P. Restorying Psychiatric Disability: Learning from First Person Recovery Narratives. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2001:335–343. doi: 10.1037/h0095071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwartz CE, Sendor RM. Helping Others Helps Oneself: Response Shift Effects in Peer Support. Social Science & Medicine. 1999:1563–1575. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sundar SS, Edwards HH, Hu Y, Stavrositu C. Blogging for Better Health: Putting the "Public" Back in Public Health. Routledge. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan L. Psychotherapy 2.0: MySpace Blogging as Self- Therapy. AJP. 2008:143–163. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2008.62.2.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thoits PA. Stress, Coping, and Social Support Processes: Where Are We? What Next? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995:53–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tremayne M. Blogging, Citizenship, and the Future of Media. Routledge. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trier J. "Cool" Engagements With YouTube: Part 1. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy. 2007:408–412. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turkle S. Looking Toward Cyberspace: Beyond Grounded Sociology. Contemporary Sociology. 1999:643–648. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Valverde M. Experience and Truth-Telling in a Post- Humanist World: A Foucauldian Contribution to Feminist Ethical Relations. University of Illinois Press. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waldron J. YouTube, Fanvids, Forums, Vlogs and Blogs: Informal Music Learning in a Convergent On- and Offline Music Community. International Journal of Music Education. 2012:1–16. [Google Scholar]