Abstract

The tumor suppressor gene p53 and its family members p63/p73 are critical determinants of tumorigenesis. ΔNp63 is a splice variant of p63, which lacks the N-terminal transactivation domain. It is thought to antagonize p53-, p63- and p73- dependent translation, thus blocking their tumor suppressor activity. In our studies of the pediatric solid tumors neuroblastoma and osteosarcoma, we find overexpression of ΔNp63; however, there is no correlation of ΔNp63 expression with p53 mutation status. Our data suggest that ΔNp63 itself endows cells with a gain of function that leads to malignant transformation, a function independent of any p53 antagonism. Here, we demonstrate that ΔNp63 overexpression, independent of p53, increases secretion of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and interleukin-8 (IL-8), leading to elevated phosphorylation of STAT-3 (Tyr-705). We show that elevated phosphorylation of STAT-3 leads to stabilization of HIF-1α protein, resulting in VEGF secretion. We also show human clinical data, which suggests a mechanistic role for ΔNp63 in osteosarcoma metastasis. In summary, our studies reveal the mechanism by which ΔNp63, as a master transcription factor, modulates tumor angiogenesis.

Keywords: p63, angiogenesis, metastasis, osteosarcoma, neuroblastoma

INTRODUCTION

p63 exhibits high sequence and structural homology to the tumor suppressor protein p53 (Trp53), and to another member of this family, p73 (Trp73) (1,2). Studies using genetically engineered mice have elucidated a central role for p63 in skin development and the aging of epithelial tissues (3–7). Through the use of alternative promoters, the p63 gene generates transcripts encoding two major classes of protein isoforms: TAp63 and ΔNp63. TAp63 contains an N-terminal transactivation (TA) domain, whereas ΔNp63 lacks this domain (2). Additional diversity arises through alternative splicing, which generates proteins with unique C-termini, designated α, β and γ. Together, these give rise to six unique p63 transcripts. All of these maintain a DNA-binding domain with significant homology to p53, but with somewhat altered target specificity (8,9).

Several reports both from in vitro and in vivo experiments have suggested that the TAp63 isoforms act as tumor suppressor genes. For instance, TAp63 isoforms suppress metastasis through induction of senescence (10) and transcriptional activation of Dicer1 and mir-130b (11). TAp63−/− mice develop metastatic mammary and lung adenocarcinoma, as well as squamous cell carcinoma with metastases to the lung, liver and brain (11).

The roles of the ΔNp63 isoforms seem to be more complex. Early studies showed that the ΔNp63 isoforms oppose p53-, TAp63- and TAp73- mediated transcription (and therefore apoptosis and cell cycle arrest), suggesting an oncogenic role for ΔNp63 isoforms (2,9,12–14). Other studies have demonstrated effects that are independent of any dominant negative inhibitory activity, such as targeting of the chromatin remodeler Lsh by ΔNp63, which results in stem cell proliferation and tumorigenesis (15). Some reports show that ΔNp63 isoforms retain transcriptionally activity and can transactivate genes involved in epidermal morphogenesis (16,17) and DNA repair (18). ΔNp63 is overexpressed in some types of adult human cancer (19), particularly squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) (20), where it promotes oncogenesis by suppressing TAp73 (21). In other tumor types, such as adenocarcinoma of the breast and prostate, ΔNp63 expression is lost during the tumorigenic process (22). While mice which exhibit knocked down (17) or total loss of expression (23) of ΔNp63 have been described, their cancer-associated phenotypes have not yet been reported.

Taken together, the role that p63 isoforms play in cancer merits further investigation. Here, we show that two childhood malignancies, neuroblastoma and osteosarcoma, overexpress ΔNp63. We find in these tumors no correlation between p53 mutation and ΔNp63 overexpression. We hypothesize that ΔNp63 is a key modulator of tumorigenesis in these childhood cancers, independent of p53 status. We demonstrate that ΔNp63α exhibits gain of function activity, which leads to the expression of crucial angiogeneic factors and promotes tumor development. Finally, we show that there is a selection for cells expressing high levels of ΔNp63 in osteosarcoma metastasis. Together, these data suggest a central role for ΔNp63 in the progression and dissemination of these childhood cancers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal studies

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with institutional animal care and use committee of the research Institute at Nationwide Children's Hospital. Approved protocols were designed to minimize the numbers of mice used and to minimize any pain or distress. For analysis of tumorigenicity, lentiviral transduced cells (1.5 × 106 cells per mouse) were suspended in 100 µl of 1×PBS and injected subcutaneously into the flank of 6-week-old CB17SC scid−/− female mice (Taconic Farms, Germantown NY). All mice were maintained under barrier conditions. Tumor volumes were measured once per week as previously described (24).

Cell culture

The neuroblastoma cell line SKNSH was maintained in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS. SKNDZ was maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS plus 0.1 mM NEAA. OHS osteosarcoma cells were obtained from Dr. Oystein Fodstad (Radium Hospital Oslo, Norway). OS-17 and OHS were cultured in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS. HEK-293T cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. Normal Human Dermal Fibroblasts (NHDF) were obtained from American Type Cell Collection (ATCC) and cultured in Fibroblast Basal Medium (ATCC, PCS-201-030) supplemented with Fibroblast Growth Kit-Low serum (ATCC, PCS-201-041) and Penicillin-Streptomycin (Life Technologies). JHU-011 cells were a generous gift of Dr. David Sidransky, (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD) and maintained in RPMI with 10% FBS. Control and STAT3−/− MEFs kindly provided by Dr. Valeria Poli (University of Dundee, United Kingdom) were cultured in in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC).

Immunoprecipitation and chromatin immunoprecipitation assay

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (EZ ChIP™ Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Kit, Millipore). Protein–DNA complexes were precipitated using a p63 antibody (4A4, Santa Cruz) and PCR was carried out using following specific primers: IL-6, forward: 5’- TAATAAGGTTTCCAATCAGCC-3’ reverse: 5’- CTCCAGTCCTATATTTATTGG-3’, IL-8 forward: 5’-CATCAGTTGCAAATCGTGGA-3’, reverse: 5’-GTTTGTGCCTTATGGAG TGCT-3’

Immunoblot, immunohistochemistry (IHC) and cell cycle analysis

Cells were lysed on ice with lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Thermoscientific), and 1mM PMSF (Sigma). Immunoblots were probed with the following antibodies: Antibodies for the detection of β-Actin and p63 (4A4) were purchased from Santa Cruz. STAT3, pSTAT3 (Tyr-705), PARP, HIF-1α and VHL were detected using Cell Signaling Technology antibodies. Total proteins of control tissues were purchased from BioChain. Immunohistochemistry assay was performed as previously described (25). For the cell cycle analysis, osteosarcoma and neuroblastoma cells (60% confluent) were transfected with scrambled or targeting ΔNp63 siRNAs, and cell cycle distribution was determined by FACs analysis staining the DNA with Propidium Iodide (BD Bioscience) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

VEGF luciferase assays, quantitative ELISA and human cytokine array

Luciferase assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega) by using following plasmids: The VEGF-Luc reporter construct was kindly provided by Dr. P. Amore (Harvard Medical School) and HRE-Luc reporter plasmid obtained from Addgene (Plasmid 26731). pcDNA3.1 is from Invitrogen and pcDNA3.1-ΔNp63α is from Addgene (Plasmid: 26979). VEGF secretion assays were performed by using Human VEGF Quantikine ELISA Kit (Cat. No. DVE00) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (R&D Systems). For human cytokine array, proteome profiler antibody array (R&D Systems) was used according to manufacturer's instructions to detect the relative levels of expression of 36 different cytokine-related proteins in NHDF electroporated with pcDNA.3 or pcDNA.3-ΔNp63α.

Quantitative migration, wound healing and endothelial cell tube formation assay

Transwell migration assays were performed using previously published methods (25). Migration was quantified using the ratio of the migrated cells over the total cells (migrated plus remaining cells) to determine the fraction of migrated cells in each individual experiment. Each experiment was performed in duplicate. Wound healing and endothelial cell tube formation assay were performed as previously described (25).

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and real time PCR (RT-PCR)

RNA isolation and reverse transcription were performed using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and Omniscript Reverse Transcriptase (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. qPCR was performed on an ABI Prism 7900HD Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems) using the TaqMan Universal Mastermix (Applied Biosystems). TAp63 and ΔNp63 expression was quantified in real-time with a specific FAM-labeled MGB-probe (Applied Biosystems) and normalized to GAPDH (Applied Biosystems). Total RNA from control tissues used as a negative control in Real-time PCR assays were purchased from BioChain.

qRT-PCR analysis of FFPE primary osteosarcomas and lung metastases

Tissue from FFPE primary osteosarcomas and corresponding lung metastases was identified through our local pathology department after approval by our local Institutional Review Board. Eleven 5 micron sections were cut from each tumor and dried on glass slides. The central section was stained with H&E and scanned to a virtual slide. Non-tumor portions of each unstained slide were scraped away using microdissecting blades. The remaining tissue was then deparaffinized in xylene and fresh 100% ethanol ×2, then scraped into a microcentrifuge tube. This was then processed using a Qiagen FFPE RNeasy kit according to the protocol recommended by the manufacturer. cDNA was generated using 0.5 ug of the isolated RNA using a High Capacity Reverse Transcriptase kit from Applied Biosciences, utilizing the gene-specific primers as noted below (pooled reverse primers). This resulting cDNAs were used as template to perform qPCR with RT2 SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix from Qiagen on an Applied Biosciences 7900HT machine. Dissociation curves were generated for each reaction and the specificity of each reaction was verified by single peak formation. Samples were normalized to the geometric mean of the expression of beta-actin and RPL13A. Primers used were: ΔNp63 forward 5’ – ACCTGGAAAACAATGCCCAGA -3’, reverse 5’ – ACGAGGAGCCGTTCTGAATC -3’, 99 bp product ACTB forward 5’ – ACAGAGCCTCGCCTTTGC – 3’,reverse 5’ – CGCGGCGATATCATCATCCA – 3’, 76 bp product RPL13A forward 5’ – GGCCCAGCAGTACCTGTTTA -3’, reverse 5’ – AGATGGCGGAGGTGCAG – 3’, 93 bp product.

Lentiviral production and siRNAs

The shRNA lentiviral constructs and high-titer lentiviral stocks were generated as described in Addgene’s pLKO.1 protocol. siRNAs targeting IL-6 and IL-8 were purchased from Dharmacon and transfected with Lipofectamin 2000 (Invitrogen) into the neuroblastoma and osteosarcoma cell lines.

RESULTS

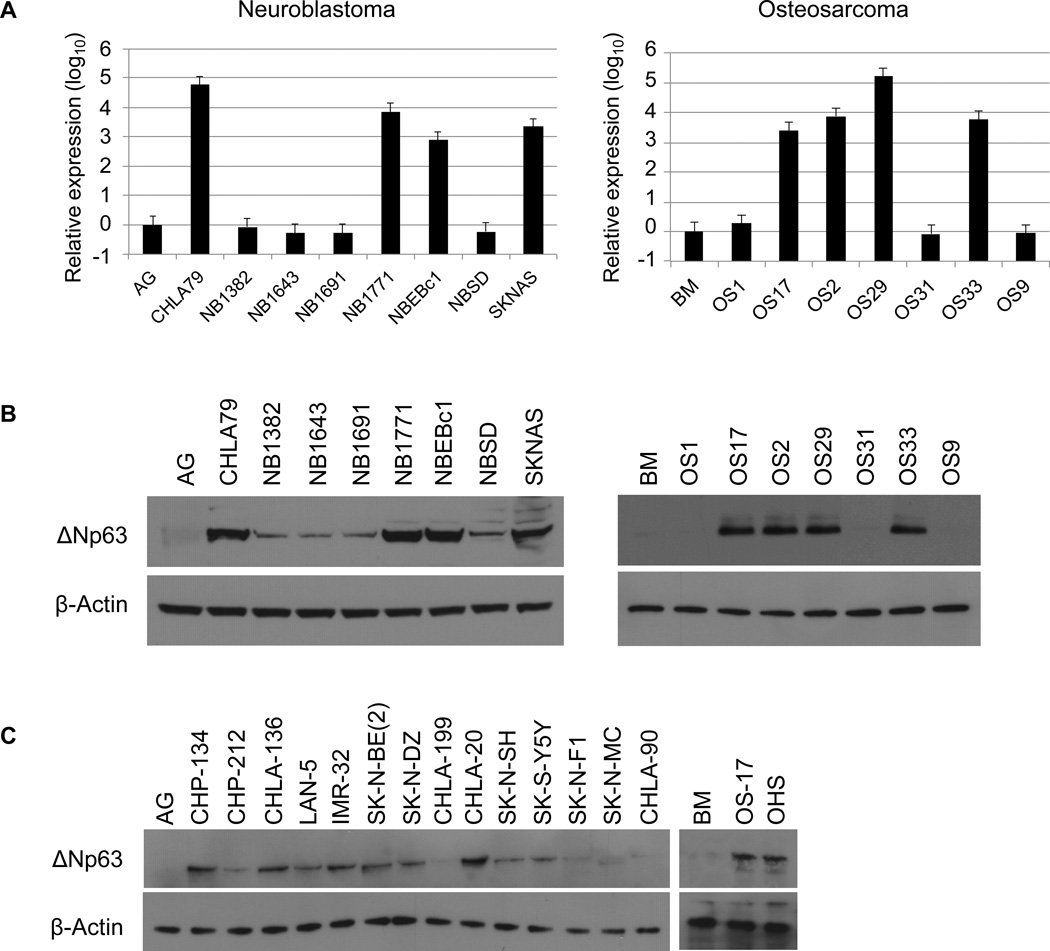

Childhood neuroblastoma and osteosarcoma express high levels of ΔNp63α

To examine the expression of ΔNp63 in childhood cancers, we surveyed the solid tumor models available through the Pediatric Preclinical Testing Program (PPTP) (Supplementary Fig. S1). Using qRT-PCR with primers designed to distinguish TA from ΔN isoforms of p63, we found that the ΔNp63 isoform is highly expressed in more than 50% of neuroblastoma and osteosarcoma tumor xenografts, ranging in abundance from 3 to 4.5 log of expression in contrast to tissues of origin (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, TA isoforms of p63 were not detectable by qRT-PCR in any of the analyzed samples. We also examined p63 protein expression in these xenografts. As shown in Fig. 1B, the expression of the ΔNp63 protein in these xenografts correlated with the expression of the ΔNp63 mRNA transcript (Fig. 1A). In addition to xenografts, we also examined p63 protein expression in neuroblastoma and osteosarcoma cell lines. We found high-level ΔNp63α expression in more than 50% of the analyzed neuroblastoma cell lines and two analyzed osteosarcoma cell lines (Fig. 1C). Consistent with prior studies showing ΔNp63α to be the major isoform (26,27), we detected p63 protein migration at 68 kDa, which is consistent with the mobility for the ΔNp63α isoform.

Figure 1.

Neuroblastoma and osteosarcoma Childhood tumors overexpress ΔNp63. A, qRT-PCR was used to assay ΔNp63 mRNA levels in neuroblastoma and osteosarcoma xenografts relative to control tissue samples. Total RNA isolated from xenografts and control tissues (AG: adrenal gland, BM: bone marrow) was reverse-transcribed and subjected to real-time PCR with probes specific for ΔNp63. Results were normalized to GAPDH. B, Immunoblot analysis of p63 protein expression in neuroblastoma and osteosarcoma xenografts. The predominant band detected corresponds to ΔNp63α and levels of ΔNp63 mRNA correlate with those of ΔNp63α protein. C, p63 protein expression analysis in neuroblastoma and osteosarcoma cell lines. Cell extracts were analyzed by western blot with antibodies as shown.

Oncogenic effects of ΔNp63α in neuroblastoma and osteosarcoma

ΔNp63α has been hypothesized to contribute to tumorigenesis based on its ability to inhibit p53-dependent transactivation (2,28). By this argument, overexpression of ΔNp63α might simply inactivate p53, abrogating the requirement for its loss during tumorigenesis. Were that hypothesis true, one would expect to find either ΔNp63 overexpression or p53 mutation, but not both. We found no consistent correlation between p53 mutation and ΔNp63α overexpression in neuroblastoma and osteosarcoma (Supplementary Table 1), which makes this hypothesis difficult to substantiate, at least in these tumors. We therefore hypothesized that ΔNp63α might endow cells with a gain of function, rather than simply blocking transcription of p53, TAp63 and TAp73.

To explore the precise function and biochemical mechanisms of ΔNp63α activity, we chose two representative cell lines from each tumor type that differ in their p53 status. We sought to understand the biologic consequence of high-level ΔNp63α expression in neuroblastoma and osteosarcoma by using a Lentiviral-mediated shRNA approach. We designed and tested three constructs expressing ΔNp63-targeted short hairpin RNA (shRNA) in pLKO.1 vectors (Supplementary Fig. 2A). None of these shRNA constructs inhibited expression of the TAp63 isoform (Supplementary Fig. 2B). Importantly, we were able to optimize lentiviral production and infection conditions in order to ensure essentially 100% infection of targeted cells, as assessed using viruses coexpressing the eGFP protein (Supplementary Fig. 2C). Under these conditions, we observed approximately 80% knockdown of endogenous ΔNp63α protein and mRNA in JHU-011 cells. These same constructs were used to infect two different neuroblastoma (SKNSH express wild-type p53 and SKNDZ express mutated p53) and osteosarcoma (OS-17 express wild-type p53 and OHS express mutated p53) cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 2D).

These transduced cell lines were used to study the effects of ΔNp63α expression on anchorage-independent growth and cell proliferation. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 3A–B, we found that inhibition of ΔNp63α significantly reduced both cell proliferation and colony formation in a soft agar assay. There was no difference in proliferation or colony formation that could be attributed to p53 status. The reduction in cell proliferation and colony formation following knockdown of endogenous ΔNp63α was not associated with apoptosis (Supplementary Fig. 3C).

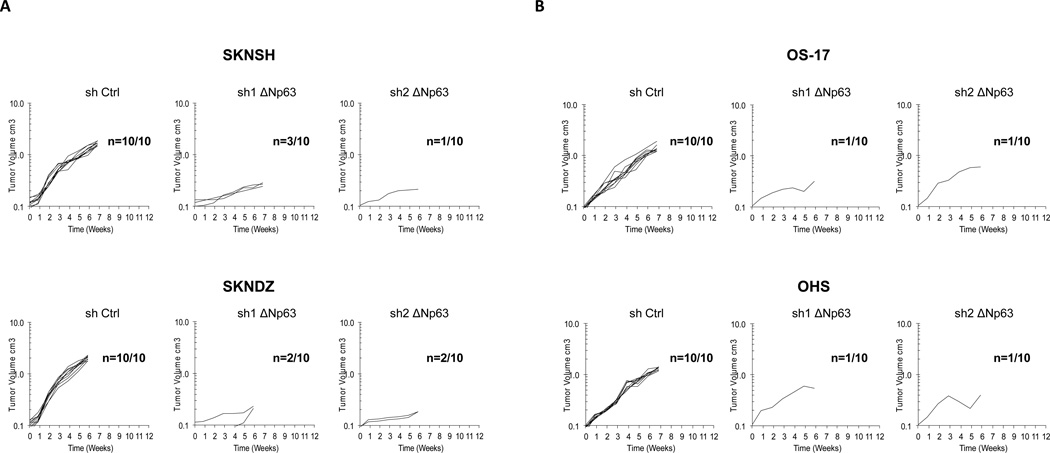

We next investigated whether high ΔNp63α expression contributes to the tumorigenic phenotype in neuroblastoma and osteosarcoma. As shown in Fig. 2, all neuroblastoma and osteosarcoma cells lines transduced with a nonsilencing control shRNA formed tumors in nude mice. By contrast, neuroblastoma cell lines with silenced ΔNp63α expression formed tumors in only 8 of 40 mice (Fig. 2A), while osteosarcoma cell lines formed tumors in only 4 of 40 mice (Fig. 2B). Similar to our in vitro experiment, decrease in tumorigenicity of neuroblastoma and osteosarcoma cells lines did not correlate with the p53 status of the injected cells.

Figure 2.

Knockdown of endogenous ΔNp63α reduces tumor growth A, neuroblastoma cell lines, SKNSH and SKNDZ transduced with a nonsilencing control shRNA or two different shRNAs targeting ΔNp63 isoforms were injected subcutaneously into 4- to 6-week-old CB17SC scid−/− mice and observed for up to 7 weeks (n=10 for each treatment). Tumor volumes were measured every week. B, osteosarcoma cell lines, OS-17 and OHS transduced with a nonsilencing control shRNA or two different shRNAs targeting ΔNp63 isoforms were injected subcutaneously into 4- to 6-week-old CB17SC scid−/− mice and observed for up to 7 weeks (n=10 for each treatment). Tumor volumes were measured every week.

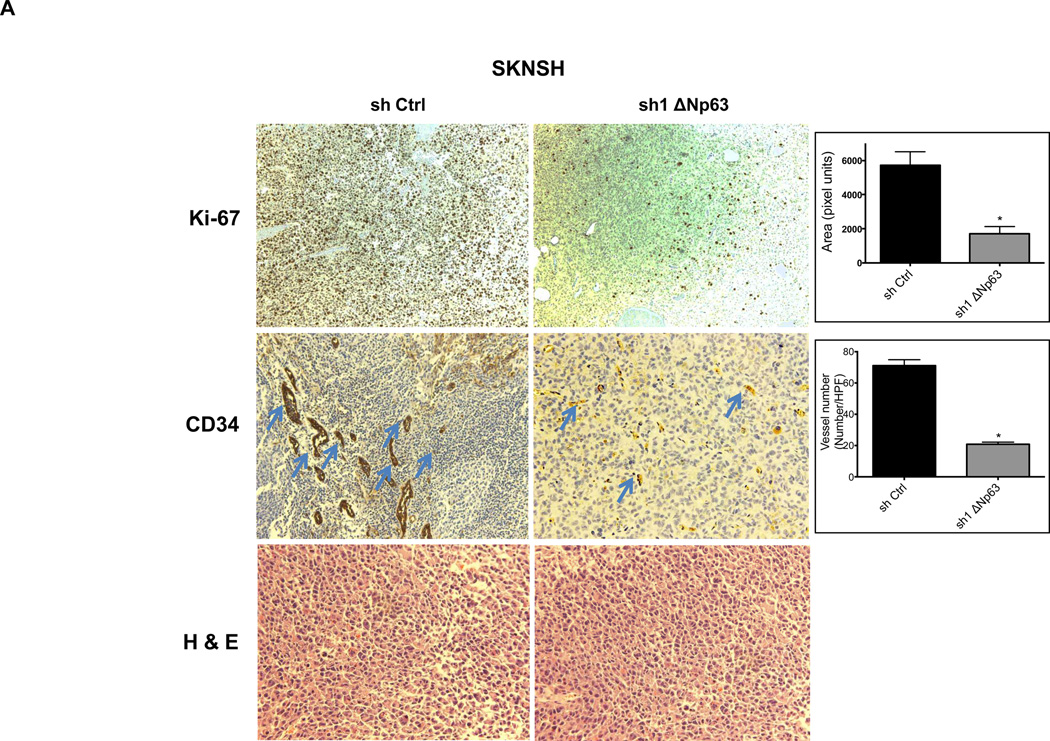

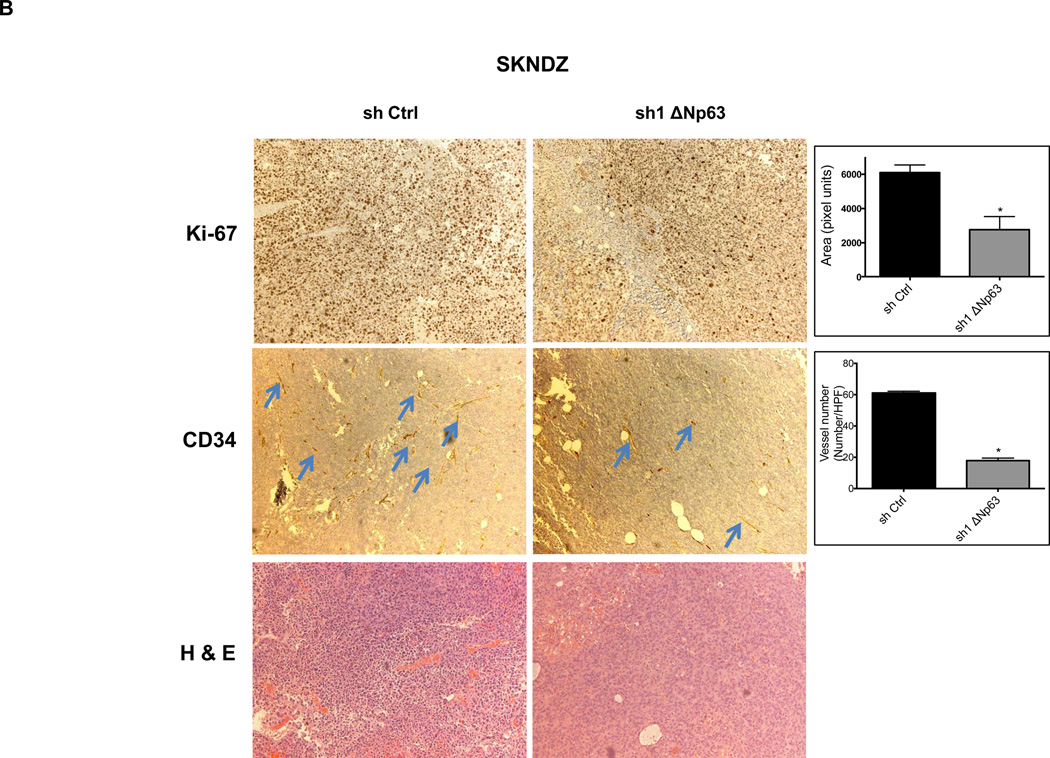

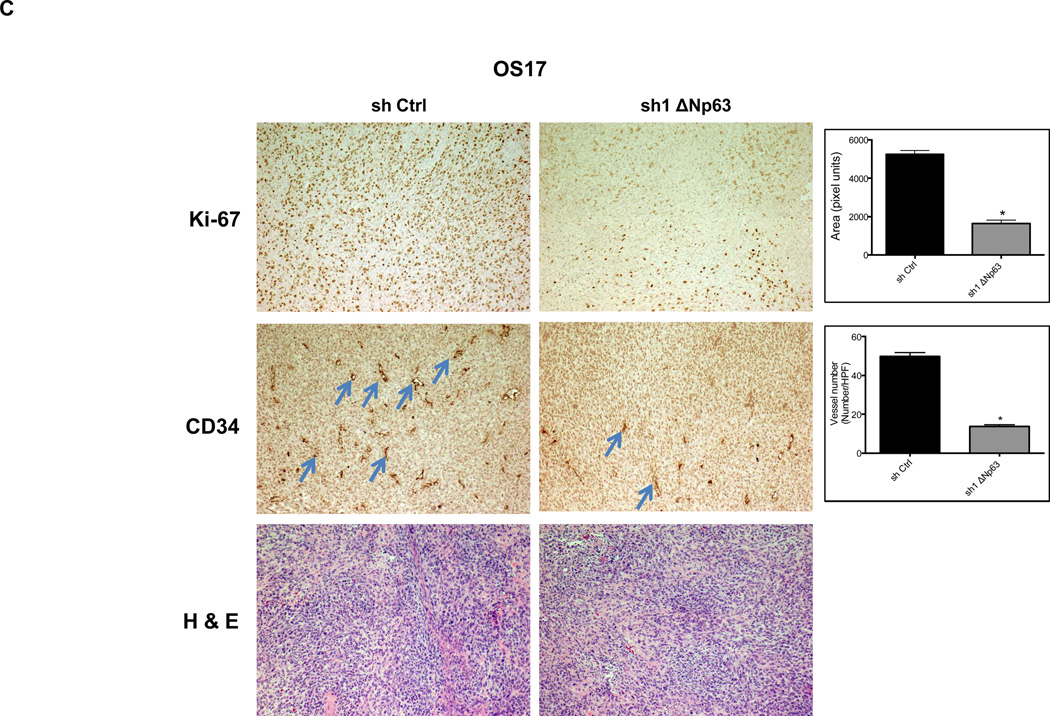

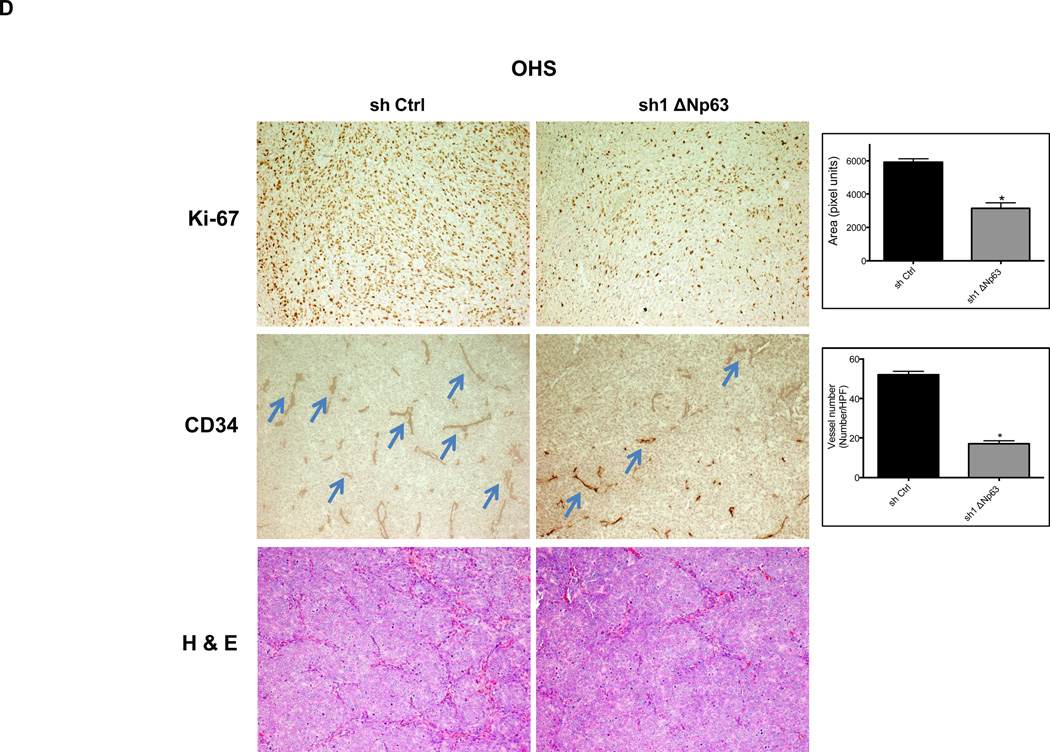

We assessed these tumors for expression of Ki-67, a well-described marker of proliferative activity. Depletion of endogenous ΔNp63α, significantly reduced Ki-67 reactivity in tumors (Fig. 3A–B). Given the essential role that angiogenesis plays in tumor formation, we sought to evaluate angiogenic activity in these same tumors. Inhibition of endogenous ΔNp63α resulted in significant decrease of CD34 immunostaining, a well-established marker for tumor angiogenesis (Fig. 3A–B). These data suggested that the contribution of ΔNp63 to progression in these tumors lies in a p53-independent, gain-of-function mechanism that involves both growth and angiogenic pathways.

Figure 3.

Depletion of endogenous ΔNp63α results in significant decrease in CD34 and Ki-67 expression. A–D, Immunohistochemistry staining of neuroblastoma and osteosarcoma tumors, which were obtained from tumors that grew in experiments presented in Figure 2. The tumor sections were stained with CD34, and Ki-67 antibodies and hematoxylin-eosin (H&E). The number of cells staining positive or vessel numbers were counted by a blinded observer in 5 random 40× fields. Treated (sh1 ΔNp63) and controls (sh Ctrl) were compared using Student t test and are quantified in histograms (Right).

ΔNp63α regulates VEGF activity and promotes migration

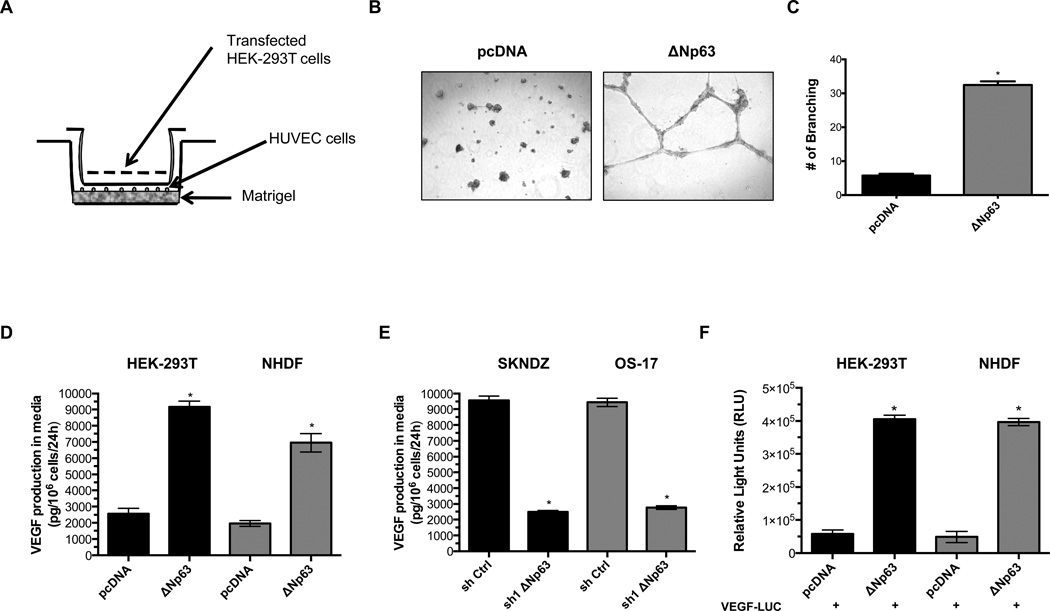

We sought to understand the mechanisms by which ΔNp63α modulates angiogenesis in neuroblastoma and osteosarcoma. One quick assessment of angiogenesis in vitro is the measurement of the ability of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) to form three-dimensional structures (tube formation). To test whether overexpression of ΔNp63α in HEK-293T could stimulate tube formation in endothelial cells, we examined endothelial tube formation using a transwell assay system, where soluble factors from HEK-293T cells stimulate endothelial tube formation (Fig. 4A). We found that overexpression of ΔNp63α in HEK-293T cells resulted in stimulation of tubular structures in HUVEC cells (Fig. 4B–C). Moreover, we found that overexpression of ΔNp63α increased wound-healing motility in HEK-293T and in primary normal human dermal fibroblast (NHDF) (Supplementary Fig. 4A–B). Depletion of the ΔNp63 isoform in neuroblastoma (SKNDZ) and osteosarcoma (OS-17) cell lines reduced wound healing motility, an effect not seen in control shRNA-treated cells (Supplementary Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Effect of ΔNp63α on endothelial tube formation, VEGF secretion and VEGF promoter activity. A, Schematic illustration of the transwell assay. HUVECs were incubated on matrigel in the lower chamber, and transfected HEK-293T cells were grown in the upper chamber separated from the HUVECs. Only secreted mediators can diffuse into the lower chamber to stimulate HUVEC tube formation. B, Tube formations in HUVECs were determined after 20 hr by staining with calcein-AM dye. C, To quantify tube formation, branching points of HUVEC cells were counted under a fluorescence microscope. D, Ectopic expression of ΔNp63α in HEK-293T and NHDF induces VEGF secretion. E, Knockdown of endogenous ΔNp63 in SKNDZ and OS-17 cell lines results in decreased secretion of VEGF. F, Ectopic expression of ΔNp63α induces VEGF promoter activity in HEK-293T and NHDF. Data shown are mean±SD from triplicate analysis.

To determine whether the ΔNp63α isoform regulates VEGF secretion, we used ELISA to assess secreted VEGF levels in HEK-293T and NHDF cells transfected with either empty vector or a ΔNp63α expression construct. In contrast to control cells, ΔNp63α overexpressing cells secreted ~4-fold more VEGF in to the medium (Fig. 4D). Moreover, ΔNp63 knockdown markedly decreased VEGF secretion in SKNDZ and OS-17 cell lines (Fig. 4E), suggesting a key role for ΔNp63α in VEGF secretion in these childhood tumors.

Given that p63 isoform are proteins with sequence-specific DNA-binding properties we hypothesized that ΔNp63α might alter the expression of genes critical to angiogenesis. Therefore, we examined VEGF expression in the presence of ΔNp63α in HEK-293T and NHDF cells. As shown in Figure 4F, expression of ΔNp63α increased luciferase activity in HEK-293T and NHDF cells that were co-transfected with a VEGF promoter-luciferase construct.

ΔNp63α induces STAT3 (Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3) phosphorylation

NHDF and HEK-293T cells do not express detectable amounts of endogenous p63 or p73, and HEK-293T cells express SV40 large T antigen that inhibits endogenous p53. Thus, transcriptional activation of the VEGF-Luc reporter by the ΔNp63α isoform was not likely due to any dominant negative effect on endogenous p53, p73 or p63. It is more probable that ΔN isoforms mediate a gain of function, which modulates cellular factor(s) that are important in the regulation of VEGF promoter activity.

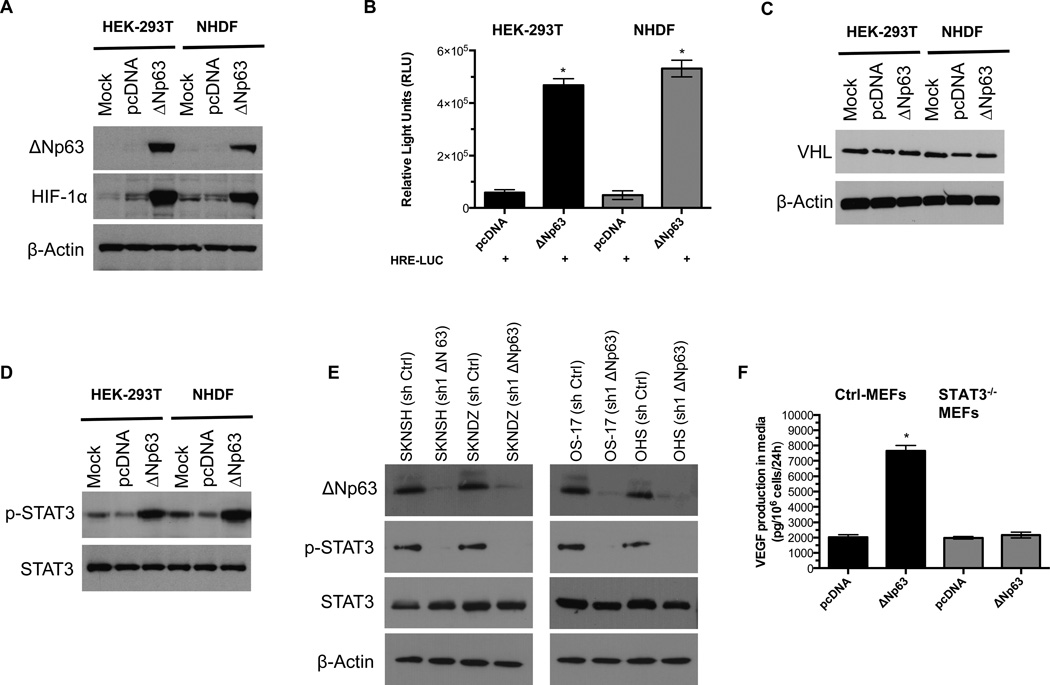

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) is a heterodimeric transcription factor that regulates transcription of several genes associated with angiogenesis including VEGF (29,30). It has been shown that ΔNp63 promotes HIF-1 stabilization in the H1299 cell line by an unknown mechanism (31). Consistent with this report, we determined that overexpression of ΔNp63α isoforms induced HIF-1 stabilization in primary NHDF and HEK-293T cells under normoxic conditions (Fig. 5A), leading to strong hypoxia response element (HRE) reporter activity (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

ΔNp63α induces HIF-1α stabilization and activates STAT3. A, HEK-293T and NHDF were transfected with pcDNA3-ΔNp63 or control vector (pcDNA.3). After 48h incubation, cell extracts were analyzed by western blot with antibodies as shown. B, Overexpression of ΔNp63α induces Hypoxia Response Element (HRE) promoter activity in HEK-293T and NHDF. C, ΔNp63α induces HIF-1stabilisation independent of VHL protein. The same sets of HEK-293T and NHDF as in Fig. 5A were examined for VHL protein. D, ΔNp63α induces STAT3 phosphorylation. After pcDNA3 or pcDNA3-ΔNp63α transfection, cells cultured in media containing 0.1% FBS for 24h and cell extracts were examined for total and phospho-STAT3 (Tyr-705). E, Depletion of endogenous ΔNp63α abrogates STAT3 phosphorylation in neuroblastoma and osteosarcoma cell lines. After sh Ctrl or sh1 ΔNp63 transduction, cells were cultured in media containing 0.1% FBS for 24h and cell extracts were analyzed by western blot with antibodies as shown. F, ΔNp63α induces VEGF secretion in a STAT3-dependent manner. Control and STAT3−/− knockout MEFs were electroporated (Amaxa) with 10µg control (pcDNA3) or pcDNA3-ΔNp63α vector. VEGF secretion assay was performed as described in Materials and Methods.

We then focused on the underlying mechanism of HIF-1 stabilization in our models. Under normoxic conditions, Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) protein directs the ubiquitination and subsequent proteosomal degradation of the HIF-1 protein, we hypothesized that high level ΔNp63 expression might reduce VHL protein expression, leading to increased HIF-1 protein levels. To test this hypothesis, we examined the VHL protein expression in the same cell lysates. As shown in Fig. 5C, the expression of VHL protein level did not change with ΔNp63α overexpression in either cells line, suggesting a mechanism of stabilization that is independent of VHL protein expression.

Others have shown that STAT3 can modulate the stability and activity of HIF-1, leading to VEGF expression (32). It has also been shown that transcriptional activity of the ΔNp63 promoter can be regulated by STAT3 and that expression of ΔNp63 cells induces STAT3 phosphorylation (Tyr-705) in Hep3B cells, generating a positive feedback loop between STAT3 and ΔNp63 (33). To investigate whether a similar process might be occurring in our NHDF and HEK-293T cells, we probed cell lysates for activated STAT3. We found that only ΔNp63α-overexpressing cells showed increased STAT3 phosphorylation at Tyr-705 (Fig. 5D). In addition, ΔNp63 knockdown in SKNDZ and OS-17 cell lines markedly decreased STAT3 phosphorylation at Tyr-705 (Fig. 5E). To show whether increased stability of HIF-1, and in turn, up-regulation of VEGF secretion, by ΔNp63α is indeed dependent on STAT3, we analyzed the effects of ΔNp63α expression on STAT3−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). As shown in Figure 5F, ΔNp63α expression on STAT3−/− MEFs did not result in a significant increase in VEGF secretion, where VEGF production was evident in the control MEFs. We also found that ΔNp63α-dependent cell migration and the induction of HIF-1 reporter were abrogated in the absence of STAT3 (Supplementary Fig. 5A–C). Taken together, our data provide direct evidence that STAT3 activation by ΔNp63 is necessary to enhance HIF-1 stability, and therefore to increase VEGF secretion.

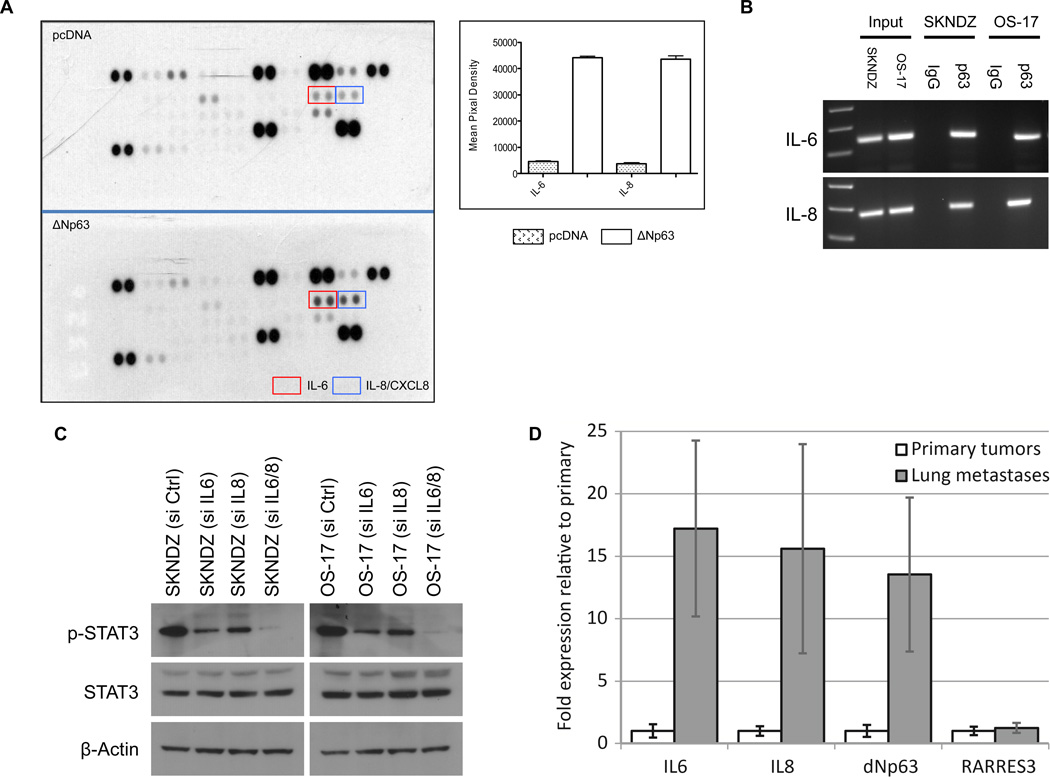

Transcriptional activity of Interleukin (IL-6 and IL-8) promoters are regulated by ΔNp63α

We next investigated the underlying molecular mechanism of STAT3 activation by ΔNp63 isoform. We compared the profiles of secreted cytokines in the presence or absence of ΔNp63α using a human cytokine antibody array. As shown in Figure 6A, in contrast to control cells, ΔNp63α-overexpressing NHDF cells showed significantly higher expression of IL-6 and IL-8 proteins. Canonical IL-6 and IL-8 signaling occurs through Janus kinases (JAKs), which in turn phosphorylate and activate STATs, including STAT3. This made a logical connection with our previous results.

Figure 6.

ΔNp63α activates IL-6 and IL-8 expression. A, After NHDF were electroporated (Amaxa) with 10µg pcDNA3 or pcDNA3-ΔNp63α vectors, cell extracts were analyzed using a proteome profiler cytokine antibody array. B, ΔNp63α binds on IL-6 and IL-8 promoters. SKNDZ and OS-17 cell extracts were used for Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay (ChIP). ChIP assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (EZ ChIP™ Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Kit, Millipore). C, Combined inhibition of IL-6 and IL-8 by specific siRNAs abrogates STAT3 activation in SKNDZ and OS-17 cell lines. After siRNA transfection, tumor cell lines were cultured in media containing 0.1% fetal bovine serum (FBS) for 72 hr, and cell extracts were analyzed by western blot with antibodies as shown. D, Sixteen samples taken from primary osteosarcoma tumors or lung metastases from patients with osteosarcoma were assessed for expression of IL-6, IL-8 and ΔNP63 by qRT-PCR. Results shown were normalized first to internal control housekeeping genes and then to the average expression in primary tumors. The Y-axis shows fold expression of ΔNP63 relative to primary tumors. Statistical comparison was made using nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test, which shows a significant difference between groups at the p = 0.024 level.

As to the upstream elements that affect IL-6 and IL-8 expression, recently published data showed that ΔNp63, RelA, and cRel members of the NF-κB family can interact together to affect transcription of NF-κB/Rel target genes, including IL-8 (34). To test whether ΔNp63 binds IL-6 and IL-8 promoter regions (which containing known NF-κB/Rel regulatory elements) in neuroblastoma and osteosarcoma cells, we conducted chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays. As shown in Figure 6B, we detected significant p63 binding activity on IL-6 and IL-8 promoters in neuroblastoma and osteosarcoma cell lines. We also examined the necessity of IL-6 and IL-8 for STAT3 activation in neuroblastoma and osteosarcoma cells. To test this, we first treated cell lines with either single or combined siRNAs specific for IL-6 and IL-8. After confirming siRNA knockdown efficiency by ELISA (Supplementary Fig.6), we performed immunoblot analysis for STAT3 phosphorylation (Tyr-705). As shown in Figure 6C, only combined inhibition of IL-6 and IL-8 by specific siRNAs significantly reduced STAT3 phosphorylation level, indicating that either IL-6 or IL-8 activity induced by ΔNp63α- is sufficient to keep STAT3 activated.

ΔNp63 expression is enhanced in osteosarcoma lung metastases

We suspected that ΔNp63 expression might endow these childhood tumors with greater metastatic potential. To address this question, we analyzed tissue samples taken from primary osteosarcoma tumors or lung metastases from patients with osteosarcoma for expression of ΔNp63 by qRT-PCR. We hypothesized that, if primary tumors contain cells that are heterogeneous for the expression of many different genes, then metastases themselves would show a selection for genes important to metastasis. As shown in Fig.6D, lung metastasis from patients with osteosarcoma reveal markedly increased expression of ΔNp63, IL-6, and IL-8 when compared to primary tumors from the same patients. To ensure that we were not observing global enrichment of inflammatory genes, we tested for expression of a related chemokine, RARRES3, but did not find enrichment. This result provides strong support for the hypothesis that IL-6 and IL-8 expression, driven by ΔNp63, plays a central role in the malignant progression of these childhood tumors. These clinical data provide first evidence that ΔNp63 expression may be a crucial factor to drive lung metastasis in osteosarcoma.

DISCUSSION

While the role of p63 in epithelial development has been well described, the mechanism by which p63 contributes to tumor pathogenesis has remained uncertain. Here we demonstrate that ΔNp63 is frequently overexpressed in osteosarcoma and neuroblastoma tumor xenografts and in clinical lung metastases of osteosarcoma. We have shown compelling evidence that ΔNp63 drives expression of IL-6 and IL-8, and have demonstrated the importance of these pathways in growth, motility, and angiogenesis within these tumors. We have also shown data from human samples suggesting a role for this process in metastasis. Importantly, we find that the mechanisms that drive these processes function independent of p53 status.

The upstream mechanisms that result in ΔNp63 overexpression remain to be elucidated. We suspect that gene amplification or polymorphisms within the internal promoter region of ΔNp63 might contribute. Indeed, polymorphisms within the internal promoter of the p53 gene have been shown to drive the overexpression of Δ133p53, an oncogenic isoform of that gene in other tumor types (35). We anticipate that future studies will delineate this process.

As tumor cells multiply, hypoxia develops. Tumor cells must drive angiogenesis in order to progress further. The ability to activate this angiogenic switch is considered a hallmark of malignancy. We have shown that ΔNp63 drives tumors to express VEGF. The ability to promote angiogenesis is likely to be one mechanism that drives the selection for these cells among metastases. While we wish to emphasize the potential role of ΔNp63 expression in angiogenesis, we note that it is difficult to establish the degree to which in vivo tumor take was impaired by decreased cell proliferation compared to the inability to form new vessels. We did make efforts to address this caveat, and provide data in supplementary Fig.7, which shows that knockdown of ΔNp63 results in G1 arrest. This suggests that ΔNp63 expression drives sustained chronic proliferation in these cell lines, making it difficult to separate in vivo effects on cell cycle from effects on angiogenesis. Indeed, the direct induction of angiogenesis by oncogenes that also drive proliferative signaling has been previously shown (e.g. Ras and Myc) illustrates the important principle that distinct hallmark capabilities (proliferative as well as inducing tumor angiogenesis) can be coregulated by the same transforming agent (e.g. ΔNp63, Ras and Myc).

Previous studies had shown that ΔNp63α activates STAT3 through phosphorylation, which leads directly to transcriptional activation of the ΔNp63 gene through binding to that gene’s promoter and generating a positive feedback loop (33). The mechanisms that led from ΔNp63 to phosphorylation and activation of STAT3, however, had not been established. Here we show that this occurs when ΔNp63 binds both IL-6 and IL-8 promoters, and that these cytokines drive STAT3 phosphorylation in an autocrine loop. We also demonstrated that stabilization of HIF-1 protein by ΔNp63α was the necessary step driving VEGF production, which is dependent on STAT3 activation. We were interested to find that this process occurs independent of alterations in VHL protein levels. The precise mechanism, which links STAT3 to the stabilization of HIF-1α, remains to be elucidated. One area of future investigation may be to determine whether STAT3 directly binds to HIF-1α and recruits it to the human VEGF promoter.

We are intrigued by the finding that tumors excised from the lungs of patients with osteosarcoma show marked high-level expression of ΔNp63 expression relative to the primary lesions from the same patients. We hypothesize that ΔNp63 endows cells with greater metastatic efficiency, as would be suggested given the way that ΔNp63 drives the production of pro-inflammatory (IL-6, IL-8) and angiogenic (VEGF) factors. Such a phenomenon would explain the profound selection for ΔNp63-expressing cells that we observed in the lung metastases (Supplementary Fig. 8). While the observations we report here do not provide conclusive evidence of this, they certainly support such a hypothesis and at the very least suggest a central role in the process.

Taken together, we demonstrate that ΔNp63 promotes tumor growth in neuroblastoma and osteosarcoma by promoting chronic proliferation and later on tumor angiogenesis by increasing secretion of IL-6 and IL-8 leading to elevated phosphorylation of STAT-3. Moreover, we found that elevated phosphorylation of STAT-3 induced stabilization of HIF-1α protein leading to increased VEGF secretion, which might be the driving force for tumor invasion and metastasis in these childhood tumors. Importantly, our clinical data provide the first evidence that analyzing of ΔNp63 expression in osteosarcoma patient with lung metastasis might be used as a prognostic factor. Furthermore, the understanding the underlying molecular mechanism of lung metastasis by high-level ΔNp63 expression will provide new therapeutic approaches targeting lung metastasis in osteosarcoma patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We like to thank Doris Phelps for the technical assistance. Nationwide Children’s Hospital’s Morphology Core for the preparation of IHC slides and for performing Flow Cytometry analysis.

Financial support: This work was supported by start-up funds from the Nationwide Children’s Hospital and MBCG seed grant from The Ohio State University (HC) and by a Translational Research Grant from the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital (RDR) and by a Pelotonia Postdoctoral Fellowship Grant (HKB), and CA165995 (PJH).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Authors' Contributions

Conception and design: H Cam

Development of methodology: HK Bid, RD Roberts, M Cam, A Audino, RT Kurmasheva

Acquisition of data (provided animals, acquired and managed patients, provided facilities, etc.): HK Bid, RD Roberts, M Cam, A Audino, RT Kurmasheva

Analysis and interpretation of data (e.g., statistical analysis, biostatistics, computational analysis): HK Bid, RD Roberts, M Cam, A Audino, RT Kurmasheva, H Cam

Writing, review, and/or revision of the manuscript: PJ Houghton, RD Roberts, H Cam, Study supervision: H Cam

Other: PJ Houghton and J Lin provided critical insights and expertise throughout.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yang A, McKeon F. P63 and P73: P53 mimics, menaces and more. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 2000;1:199–207. doi: 10.1038/35043127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang A, Kaghad M, Wang Y, Gillett E, Fleming MD, Dötsch V, et al. p63, a p53 homolog at 3q27–29, encodes multiple products with transactivating, death-inducing, and dominant-negative activities. Mol Cell. 1998;2:305–316. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80275-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keyes WM, Wu Y, Vogel H, Guo X, Lowe SW, Mills AA. p63 deficiency activates a program of cellular senescence and leads to accelerated aging. Genes & development. 2005;19:1986–1999. doi: 10.1101/gad.342305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mills AA, Zheng B, Wang XJ, Vogel H, Roop DR, Bradley A. p63 is a p53 homologue required for limb and epidermal morphogenesis. Nature. 1999;398:708–713. doi: 10.1038/19531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mills AA, Qi Y, Bradley A. Conditional inactivation of p63 by Cre-mediated excision. Genesis (New York, NY.:2000) 2002;32:138–141. doi: 10.1002/gene.10067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pellegrini G, Dellambra E, Golisano O, Martinelli E, Fantozzi I, Bondanza S, et al. p63 identifies keratinocyte stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S. 2001;98:3156–3161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061032098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang A, Schweitzer R, Sun D, Kaghad M, Walker N, Bronson RT, et al. p63 is essential for regenerative proliferation in limb, craniofacial and epithelial development. Nature. 1999;398:714–718. doi: 10.1038/19539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harms K, Nozell S, Chen X. The common and distinct target genes of the p53 family transcription factors. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS. 2004;61:822–842. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3304-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Westfall MD, Mays DJ, Sniezek JC, Pietenpol JA. The Delta Np63 alpha phosphoprotein binds the p21 and 14-3-3 sigma promoters in vivo and has transcriptional repressor activity that is reduced by Hay-Wells syndrome-derived mutations. Molecular and cellular biology. 2003;23:2264–2276. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.7.2264-2276.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo X, Keyes WM, Papazoglu C, Zuber J, Li W, Lowe SW, et al. TAp63 induces senescence and suppresses tumorigenesis in vivo. Nature cell biology. 2009;11:1451–1457. doi: 10.1038/ncb1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Su X, Chakravarti D, Cho MS, Liu L, Gi YJ, Lin YL, et al. TAp63 suppresses metastasis through coordinate regulation of Dicer and miRNAs. Nature. 2010;467:986–990. doi: 10.1038/nature09459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee H, Kimelman D. A dominant-negative form of p63 is required for epidermal proliferation in zebrafish. Developmental cell. 2002;2:607–616. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00166-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bakkers J, Hild M, Kramer C, Furutani-Seiki M, Hammerschmidt M. Zebrafish DeltaNp63 is a direct target of Bmp signaling and encodes a transcriptional repressor blocking neural specification in the ventral ectoderm. Developmental cell. 2002;2:617–627. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang A, Zhu Z, Kettenbach A, Kapranov P, McKeon F, Gingeras TR, et al. Genome-wide mapping indicates that p73 and p63 co-occupy target sites and have similar dna-binding profiles in vivo. Plos One. 2010;5:e11572. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keyes WM, Pecoraro M, Aranda V, Vernersson-Lindahl E, Li W, Vogel H, et al. DeltaNp63alpha is an oncogene that targets chromatin remodeler Lsh to drive skin stem cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. Cell stem cell. 2011;8:164–176. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vigano MA, Lamartine J, Testoni B, Merico D, Alotto D, Castagnoli C, et al. New p63 targets in keratinocytes identified by a genome-wide approach. Embo J. 2006;25:5105–5116. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koster MI, Dai D, Marinari B, Sano Y, Costanzo A, Karin M, et al. p63 induces key target genes required for epidermal morphogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S. 2007;104:3255–3260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611376104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin YL, Sengupta S, Gurdziel K, Bell GW, Jacks T, Flores ER. p63 and p73 transcriptionally regulate genes involved in DNA repair. Plos Genet. 2009:5:e1000680. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 19.Su X, Chakravarti D, Flores ER. p63 steps into the limelight: crucial roles in the suppression of tumorigenesis and metastasis. Nature reviews. Cancer. 2013;13:136–143. doi: 10.1038/nrc3446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hibi K, Trink B, Patturajan M, Westra WH, Caballero OL, Hill DE, et al. AIS is an oncogene amplified in squamous cell carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S. 2000;97:5462–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rocco JW, Leong CO, Kuperwasser N, DeYoung MP, Ellisen LW. p63 mediates survival in squamous cell carcinoma by suppression of p73-dependent apoptosis. Cancer cell. 2006;9:45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Di Como CJ, Urist MJ, Babayan I, Drobnjak M, Hedvat CV, Teruya-Feldstein J, et al. p63 expression profiles in human normal and tumor tissues. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2002;8:494–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Romano RA, Smalley K, Magraw C, Serna VA, Kurita T, Raghavan S, et al. DeltaNp63 knockout mice reveal its indispensable role as a master regulator of epithelial development and differentiation. Development (Cambridge, England) 2012;139:772–782. doi: 10.1242/dev.071191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Houghton PJ, Morton CL, Tucker C, Payne D, Favours E, Cole C, et al. The pediatric preclinical testing program: description of models and early testing results. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2007;49:928–940. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bid HK, Oswald D, Li C, London CA, Lin J, Houghton PJ. Anti-angiogenic activity of a small molecule STAT3 inhibitor LLL12. Plos One. 2012:7:e35513. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parsa R, Yang A, McKeon F, Green H. Association of p63 with proliferative potential in normal and neoplastic human keratinocytes. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 1999;113:1099–1105. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sniezek JC, Matheny KE, Westfall MD, Pietenpol JA. Dominant negative p63 isoform expression in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. The Laryngoscope. 2004;114:2063–2072. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000149437.35855.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.King KE, Ponnamperuma RM, Yamashita T, Tokino T, Lee LA, Young MF, et al. deltaNp63alpha functions as both a positive and a negative transcriptional regulator and blocks in vitro differentiation of murine keratinocytes. Oncogene. 2003;22:3635–3644. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iyer NV, Kotch LE, Agani F, Leung SW, Laughner E, Wenger RH, et al. Cellular and developmental control of O2 homeostasis by hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha. Genes & development. 1998;12:149–162. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.2.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kotch LE, Iyer NV, Laughner E, Semenza GL. Defective vascularization of HIF-1alpha-null embryos is not associated with VEGF deficiency but with mesenchymal cell death. Developmental biology. 1999;209:254–267. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Senoo M, Matsumura Y, Habu S. TAp63gamma (p51A) and dNp63alpha (p73L), two major isoforms of the p63 gene, exert opposite effects on the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) gene expression. Oncogene. 2002;21:2455–2465. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jung JE, Lee HG, Cho IH, Chung DH, Yoon SH, Yang YM, et al. STAT3 is a potential modulator of HIF-1-mediated VEGF expression in human renal carcinoma cells. Faseb J. 2005;19:1296–1298. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3099fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chu WK, Dai PM, Li HL, Chen JK. Transcriptional activity of the DeltaNp63 promoter is regulated by STAT3. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:7328–7337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800183200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang X, Lu H, Yan B, Romano RA, Bian Y, Friedman J, et al. DeltaNp63 versatilely regulates a Broad NF-kappaB gene program and promotes squamous epithelial proliferation, migration, and inflammation. Cancer research. 2011;71:3688–3700. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bellini I, Pitto L, Marini MG, Porcu L, Moi P, Garritano S, et al. DeltaN133p53 expression levels in relation to haplotypes of the TP53 internal promoter region. Human mutation. 2010;31:456–465. doi: 10.1002/humu.21214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.