Abstract

Objective. To assess the effects of problem-based learning (PBL) on the learning achievements of pharmacy students. Methods. We searched for controlled studies that compared PBL to traditional learning in pharmacy courses (graduate and undergraduate) in the major literature databases up to January 2014. Two independent researchers selected the studies, extracted the data, and assessed the quality of the studies. Meta-analyses of the outcomes were performed using a random effects model. Results. From 1,988 retrieved records, five were included in present review. The studies assessed students' impressions about the PBL method and compared student grades on the midterm and final examinations. PBL students performed better on midterm examinations (odds ratio [OR] = 1.46; confidence interval [IC] 95%: 1.16, 1.89) and final examinations (OR = 1.60; IC 95%: 1.06, 2.43) compared with students in the traditional learning groups. No difference was found between the groups in the subjective evaluations. Conclusion. pharmacy students' knowledge was improved by the PBL method. Pharmaceutical education courses should consider implementing PBL.

1. Introduction

Problem-based learning (PBL) is an educational method focused on self-directed learning, small groups discussion with facilitators and working through problems to acquire knowledge [1]. It was first implemented in medical education in the 1960s [2]. This method can be an important tool in healthcare career education, in which students learn by working with real-life cases. In a PBL course, the instructor helps the students develop problem solving skills, self-directed learning, collaboration skills and intrinsic motivation, which led students identify what they know, what they need to know, and how and where to access new information they need [1, 3, 4]. It is expected that professionals will feel more prepared following PBL when faced with similar situations in the workplace.

PBL has also been used in pharmaceutical education courses, and numerous published reports describe the resulting experiences with this educational method [5]. However, the benefits of PBL for graduate and undergraduate pharmacy students have not been clearly shown. Thus, the aim of our study was to assess the effects of PBL in pharmacy education through a systematic review of the literature with meta-analysis.

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol

The current review was registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), registration number: CRD42012002088.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

We considered eligible controlled studies that compared the use of problem-based learning (PBL) methods in graduate (continuous education or postgraduation) or undergraduate (college) pharmacy education courses to the use of traditional methods. The outcomes of interest were the effects on students' learning evaluations.

2.3. Information Sources

We searched the MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), ISI Web of Science, Education Resources Information Center (ERIC), Academic Search Premier, Wilson Education Full Text, ProQuest, Literature in the Health Sciences in Latin America and the Caribbean (LILACS), and Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO) databases. To identify potentially eligible studies, we also hand-searched the Pharmacy Education Journal, the website of the International Pharmaceutical Federation, and references from relevant articles. The last search was performed in January 2014.

2.4. Search Strategy

We used the following strategy for MEDLINE (via PubMed): (“problem-based learning”[mesh] or “problem-based learning”[tiab] or “problem based learning”[tiab] or “problem-based curriculum”[tiab] or “problem-based curricula”[tiab] or “experiential learning”[tiab] or “active learning”[tiab] or “problem solving”[mesh] or “problem solving”[tiab]) and (“pharmacy”[tiab] or “pharmacist”[tiab] or “pharmaceutical”[tiab] or “students, pharmacy”[mesh] or “schools, pharmacy”[mesh] or “education, pharmacy, graduate”[mesh] or “education, pharmacy”[mesh]). Variations of this strategy were applied when searching other sources.

2.5. Study Selection and Data Collection Process

Two researchers (CN, LR) independently reviewed the retrieved studies. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or by a third reviewer (TFG). CN and LR extracted the data and TFG confirmed the extraction.

For crossover design studies, only the results prior to the crossover were included to eliminate the risk of measurement bias from the residual effects of the specific methods.

We designed a data extraction sheet to collect the relevant data from each study, including country, year, type of allocation, funding source, sample size, type of course, intervention duration, intervention description, and subjective and objective evaluations results. We contacted the authors of the studies as needed to obtain relevant data not included in the reports.

2.6. Quality Assessment

For this study, we only included studies that had comparison groups without systematic differences between the groups in the analysis. We considered random assignment to teaching methods an indicator of a high quality study. If the groups were formed by other means, we assessed baseline characteristics to determine if there was a selection bias that could favor any group of students. We also reviewed the losses in planned follow-up procedures to assess if there was any performance bias. Any study that did not meet the quality criteria was not included in this review.

We did not consider allocation concealment (to maintain confidential the information of which group each student belonged until the end of the study) and blinding (not knowing to which group each student belonged) in the quality assessment of the studies because these procedures are not feasible in educational research.

2.7. Data Analysis

The primary outcome was the standardized mean difference (SMD) of objective evaluations of learning. For better interpretation of the SMD, the odds ratio (OR) was further calculated using the equation ln(OR) = π/√3 × SMD [6, 7].

The meta-analyses of SMD were grouped by the random-effects Mantel-Haenszel model and are presented with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Heterogeneity of the results was estimated by the I ², τ 2, and χ 2 (P > 0.10) tests, and the risk of publication bias was assessed by inspection of funnel plot asymmetry.

3. Results

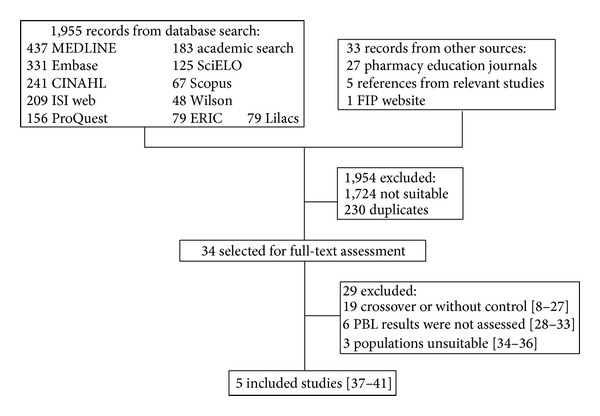

The literature search retrieved 1,988 articles, of which 34 articles were selected for full-text assessment [8–41]. Of that group, five studies were included in this review [37–41]. The flow diagram (Figure 1) illustrates the steps taken to select the studies for the current research.

Figure 1.

The search, selection, and inclusion process used in the study.

3.1. Study Characteristics

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the included studies. Five studies measured the results of the PBL method through objective methods, although one study [40] used only a subjective evaluation involving a questionnaire designed to assess graduating students' perceptions about their preparation for practice. Another study used both objective and subjective methods through final examinations and surveys to assess the students confidence in performing certain practice activities, respectively [37].

Table 1.

The main characteristics of the included studies.

| Study | Country | Dates of research | Population | Random allocation | Type and length of course | PBL intervention (N) | Control intervention (N) | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Raisch et al. 1995 [37] |

USA | 1993-1994 | Undergraduate students | Yes | 8 weekly sessions of two hours during externship | Small group discussion of cases led by facilitator and problem solving (26) | Externship with no modifications (19) | Objective and subjective evaluations |

|

| ||||||||

| Nii 1996 [38] | USA | 1994-1995 | Graduate students (PharmD) | Yes | 2 semesters in the third year preceding clerkship | Small group discussion of cases led by facilitator (58) | Didactic lectures (60) | Objective evaluation (grade point average) |

|

| ||||||||

|

Reeves and Francis 2002 [39] |

United Kingdom | 1997-1998 | Pharmacists | No | 6 months of continuing education | Adverse drug reactions cases in the context of a clinical scenario (16) | Didactic lectures (15) | Objective evaluation (multiple-choice questions) |

|

| ||||||||

|

Whelan et al. 2007 [40] |

Canada | 1998, 2001-2002 | Undergraduate students | No | Entire graduation course | Small group discussion of cases led by facilitator and problem solving (127) | Didactic lectures (59) | Subjective evaluation (survey of perception of preparedness) |

|

| ||||||||

|

Romero et al. 2010 [41] |

USA | 2002–2008 | Graduate students (PharmD) | Yes | 4 weeks of PBL during the first semester of PharmD curriculum | Small group discussion of cases led by facilitator and problem solving (675) | Didactic lectures (645) | Objective evaluation (midterm and final tests) |

Notes:

N: number of students.

PBL: problem-based learning.

PharmD: doctor of pharmacy (professional doctor degree).

The results of the studies were presented as means and standard deviations, using different rating scales. Two studies included a third group of students that was not of interest to this review: a group without intervention and a group in a transitional program using both traditional and PBL methods [39, 40]. Two studies reported losses from the initial sample; one study sent questionnaires to 186 students but finished with 137 students that completed the survey [40]. The other had five losses in the PBL group and four in the traditional curriculum group, and these were explained by refusal to participate, rural internship and scheduling conflicts [37].

Three studies formed groups by randomization [37, 38, 41]. One study assessed the students in the classes before and after PBL implementation and another one compared two courses held at different hospital pharmacies [39, 40]. There was no observed tendency in the selection of study methods and procedures in either group or during follow-up in any study.

3.2. Outcomes

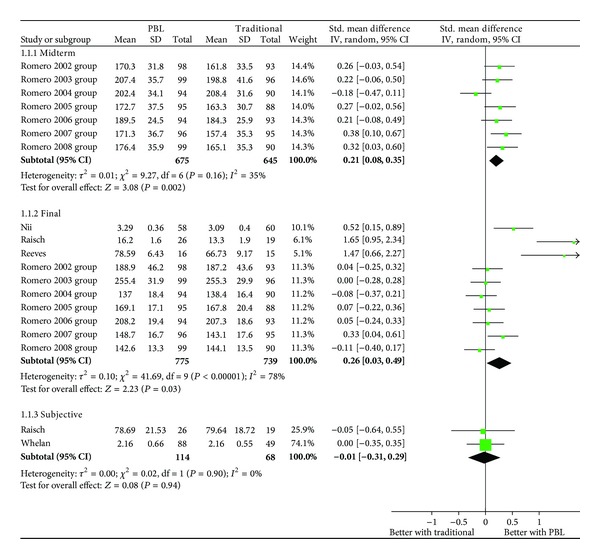

The meta-analysis of both the objective assessments (midterm and final examinations) and subjective assessments is presented in Figure 2. While the final and midterm results significantly favored the PBL group, no difference was observed in the subjective evaluations. a Significant heterogeneity was found in the final exam results (I ² = 78%). The sensitivity analysis revealed that two studies were the major contributors to this result [37, 39], and no quality limitation was found in the studies.

Figure 2.

Results of the objective evaluations (final and midterm exams) and subjective evaluations.

The OR estimates were also statistically significant for the midterm exams (OR = 1.46; IC 95%: 1.16–1.89) and for the final exams (OR = 1.60; IC 95%: 1.06–2.43), which indicates a better performance by PBL students compared with those participating in traditional learning methods. For the subjective assessment, no difference was found between the comparison groups (OR = 0.98; IC 95%: 0.57–1.66).

Despite the small number of studies examined, we assessed the funnel plot asymmetry and found that there was no suggestion of a risk of publication bias.

4. Discussion

The PBL pharmacy students performed better in academic examinations than the students in the traditional learning method group. Subjective evaluations of the students did not differ between the two groups. The findings indicate that the confidence in learning was similar between the two groups, while performance on course assessments was better in PBL. No study reported professional activity-related outcomes. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review with meta-analysis of the effects of PBL in pharmaceutical education.

The present findings for pharmaceutical education are consistent with recent research in nursing [42], medical [43], and dental education [44]. This makes PBL the preferred education method for healthcare courses. The main barriers for implementing PBL are teacher and staff training and a necessary reduction in class size, which could increase the cost of pharmacy education [45, 46]. Research in the field shows, however, that PBL and traditional curriculum costs are comparable, and the main difference is the way teachers and other faculty personnel carry out their duties, because the PBL program requires greater engagement with students [47–49].

Because PBL encourages students to think about and solve real problems, it is likely to aid their use of knowledge in clinical situations, help develop their clinical reasoning, and encourage self-directed learning throughout their professional careers [4, 46]. In healthcare fields, these skills are highly desirable and valuable.

The present results are based on a small number of studies that may not reflect the diversity of pharmaceutical education in different contexts. To avoid missing relevant studies, we followed a registered protocol that comprised sensible searches in the major information databases and included studies conducted in both graduate and undergraduate pharmacy courses. To minimize the risk of bias, only studies of acceptable quality were considered. Another limitation of our review is the absence of studies that assessed effects on the professional achievements of pharmacists who experienced the PBL method compared with the achievements of those who were given traditional methods of instruction. The current results demonstrate that PBL students perform better academically; however, we cannot infer that this improvement results in better professionals.

Future research should prioritize experimental designs that assess outcomes that are more directly associated with professional effectiveness and more valuable in the workplace. More evidence in the field could be provided—without substantially increased costs—by recording and reporting the results of the implementation of PBL methods.

5. Conclusion

The PBL curriculum seems to improve the academic performance of pharmacy students when compared to the traditional method of instruction. Directors and teachers of pharmacy graduate and undergraduate courses should consider gradually introducing PBL methods into their programs. Reporting the results from such initiatives is likely to improve the quality of the existing evidence in support of PBL methods.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Hmelo-Silver CE. Problem-based learning: what and how do students learn? Educational Psychology Review. 2004;16(3):235–266. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donner RS, Bickley H. Problem-based learning in American medical education: an overview. Bulletin of the Medical Library Association. 1993;81(3):294–298. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmidt HG, Rotgans JI, Yew EHJ. The process of problem-based learning: what works and why. Medical Education. 2011;45(8):792–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrows HS. A taxonomy of problem-based learning methods. Medical Education. 1986;20(6):481–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1986.tb01386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cisneros RM, Salisbury-Glennon JD, Anderson-Harper HM. Status of problem-based learning research in pharmacy education: a call for future research. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 2002;66(1):19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chinn S. A simple method for converting an odds ratio to effect size for use in meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine. 2000;19(22):3127–3131. doi: 10.1002/1097-0258(20001130)19:22<3127::aid-sim784>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5. 0. 2, April 2011, http://www.cochrane-handbook.org/

- 8.Busto U, Knight K, Janecek E, Isaac P, Parker K. A problem-based learning course for pharmacy students on alcohol and psychoactive substance abuse disorders. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 1994;58:55–60. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haworth IS, Eriksen SP, Chmait SH, et al. A problem based learning, case study approach to pharmaceutics: faculty and student perspectives. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 1998;62(4):398–405. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sibbald D. Innovative, problem-based, pharmaceutical care courses for self-medication. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 1998;62(2):109–119. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Catney CM, Currie JD. Implementing problem-based learning with WWW support in an introductory pharmaceutical care course. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 1999;63(1):97–104. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rhodes DG. A practical approach to problem-based learning: simple technology makes PBL accessible. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 1999;63(4):410–413. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shih YT, Kauf TL, Biddle AK, Simpson KN. Incorporating problem-based learning concepts into a lecture-based pharmacoeconomics course. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 1999;63(2):152–159. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borrego ME, Rhyne R, Clark Hansbarger L, et al. Pharmacy student participation in rural interdisciplinary education using problem based learning (PBL) case tutorials. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 2000;64(4):355–363. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lubawy W, Brandt B. A variable structure, less resource intensive modification of problem-based learning for pharmacology instruction to health science students. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology. 2002;366(1):48–57. doi: 10.1007/s00210-002-0557-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng JWM, Alafris A, Kirschenbaum HL, Kalis MM, Brown ME. Problem-based learning versus traditional lecturing in pharmacy students’ short-term examination performance. Pharmacy Education. 2003;3(2):117–125. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bratt AM. A large group hybrid lecture and problem-based learning approach to teach Central Nervous System Pharmacology within the third year of an integrated masters level pharmacy degree course. Pharmacy Education. 2003;3(1):35–52. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mackellar A, Silverthorne J, Thomas S, Price G, Cantrill J. Problem-based learning in the fourth year of the MPharm at Manchester. Pharmaceutical Journal. 2005;274(7334):117–120. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hogan S, Lundquist LM. The impact of problem-based learning on students’ perceptions of preparedness for advanced pharmacy practice experiences. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 2006;70(4, article 82) doi: 10.5688/aj700482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saito I, Kogo M, Sasaki K, Sato H, Kiuchi Y, Yamamoto T. Introducing novel learning methods to a pharmacy school in Japan: a preliminary analysis. Pharmacy Education. 2007;7(2):103–108. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ross LA, Crabtree BL, Theilman GD, Ross BS, Cleary JD, Byrd HJ. Implementation and refinement of a problem-based learning model: a ten-year experience. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 2007;71(1, article 17) doi: 10.5688/aj710117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamoudi NM, Nagavi BG, Al-Azzawi AMJ. Problem based learning and its impact on learning behavior of pharmacy students in RAK medical and Health Sciences University. Indian Journal of Pharmaceutical Education and Research. 2010;44(3):206–219. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strohfeldt K, Grant DT. A model for self-directed problem-based learning for renal therapeutics. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 2010;74(9):p. 173. doi: 10.5688/aj7409173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sherman JJ, Riche DM, Stover KR. Instructional design and assessment, physical assessment experience in a problem-based learning course. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 2011;75(8):p. 6. doi: 10.5688/ajpe758156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramsauer VP. An elective course to engage pharmacy students in research activities. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 2011;75(7):p. 6. doi: 10.5688/ajpe757138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Azu OO, Osinubi AA. A survey of problem-based learning and traditional methods of teaching anatomy to 200 level pharmacy students of the university of lagos, Nigeria. African Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 2011;5(2):219–224. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strand LM, Morley PC. Evolving health care systems: academic implications for teaching methodologies with emphasis on administration and practice. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 1987;51(4):402–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Romero RM, Eriksen SP, Haworth IS. A decade of teaching pharmaceutics using case studies and problem-based learning. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 2004;68(2, article 31) doi: 10.5688/aj740466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sekiguchi M, Yamato I, Kato T, Torigoe K. Introduction of active learning and student readership into the teaching of pharmaceutical faculty. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2005;125(7):593–599. doi: 10.1248/yakushi.125.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cahill J, Turner J, Barefoot H. Enhancing the student learning experience: the perspective of academic staff. Educational Research. 2010;52(3):283–295. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ge X, Planas LG, Er N. A cognitive support system to scaffold students' problem-based learning in a web-based learning evironment. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning. 2010;4:30–56. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zakaria SF, Awaisu A. Shared-learning experience during a clinical pharmacy practice experience. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 2011;75(4):p. 6. doi: 10.5688/ajpe75475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Antepohl W, Herzig S. Problem-based learning versus lecture-based learning in a course of basic pharmacology: a controlled, randomized study. Medical Education. 1999;33(2):106–113. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller SK. A comparison of student outcomes following problem-based learning instruction versus traditional lecture learning in a graduate pharmacology course. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 2003;15(12):550–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2003.tb00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Novak S, Shah S, Wilson JP, Lawson KA, Salzman RD. Pharmacy students’ learning styles before and after a problem-based learning experience. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 2006;70(4, article 74) doi: 10.5688/aj700474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abate MA, Meyer-Stout PJ, Stamatakis MK, Gannett PM, Dunsworth TS, Nardi AH. Development and evaluation of computerized problem-based learning cases emphasizing basic sciences concepts. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 2000;64(1):74–82. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raisch DW, Holdsworth MT, Mann PL, Kabat HF. Incorporating problem-based, student-centered learning into pharmacy externship rotations. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 1995;59:265–272. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nii LJ. Comparative trial of problem-based learning versus didactic lectures on clerkship performance. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 1996;60(2):162–164. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reeves JA, Francis SA. A comparison between two methods of teaching hospital pharmacists about adverse drug reactions: problem-based learning versus a didactic lecture. Pharmacy Education. 2002;1:25–35. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whelan AM, Mansour S, Farmer P, Yung D. Moving from a lecture-based to a problem-based learning curriculum-perceptions of preparedness for practice. Pharmacy Education. 2007;7(3):239–247. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Romero RM, Eriksen SP, Haworth IS. Quantitative assessment of assisted problem-based learning in a pharmaceutics course. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 2010;74(4):p. 9. doi: 10.5688/aj740466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shin IS, Kim JH. The effect of problem-based learning in nursing education: a meta-analysis. Advances in Health Sciences Education. 2013;18(5):1103–1120. doi: 10.1007/s10459-012-9436-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tayyeb R. Effectiveness of problem based learning as an instructional tool for acquisition of content knowledge and promotion of critical thinking among medical students. Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons Pakistan. 2013;23:42–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang B, Zheng L, Li C, Li L, Yu H. Effectiveness of problem-based learning in chinese dental education: a meta-analysis. Journal of Dental Education. 2013;77:377–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Finucane PM, Johnson SM, Prideaux DJ. Problem-based learning: its rationale and efficacy. Medical Journal of Australia. 1998;168(9):445–448. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1998.tb139025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jones RW. Problem-based learning: description, advantages, disadvantages, scenarios and facilitation. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care. 2006;34(4):485–488. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0603400417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hamdy H, Agamy E. Is running a Problem-Based Learning curriculum more expensive than a traditional Subject-Based Curriculum? Medical Teacher. 2011;33(9):e509–e514. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.599451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mennin SP, Martinez-Burrola N. The cost of problem-based vs traditional medical education. Medical Education. 1986;20(3):187–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1986.tb01166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Donner RS, Bickley H. Problem-based learning: an assessment of its feasibility and cost. Human Pathology. 1990;21(9):881–885. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(90)90170-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]