Abstract

Surgery induces learning and memory impairment. Neuroinflammation may contribute to this impairment. Nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) is an important transcription factor to regulate the expression of inflammatory cytokines. We hypothesize that inhibition of NF-κB by pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (PDTC) reduces neuroinflammation and the impairment of learning and memory. To test this hypothesis, four-month old male Fischer 344 rats were subjected to right carotid exploration under propofol and buprenorphine anesthesia. Some rats received two doses of 50 mg/kg PDTC given intraperitoneally 30 min before and 6 h after the surgery. Rats were tested in the Barnes maze and fear conditioning paradigm begun 6 days after the surgery. Expression of various proteins related to inflammation was examined in the hippocampus at 24 h or 21 days after the surgery. Here, surgery, but not anesthesia alone, had a significant effect on prolonging the time needed to identify the target hole during the training sessions of Barnes maze. Surgery also increased the time for identifying the target hole in the long-term memory test and decreased context-related learning and memory in fear conditioning test. Also, surgery increased nuclear expression of p65, a NF-κB component, decreased cytoplasmic amount of inhibitor of NF-κB, and increased the expression of interleukin-1β, interleukin-6, ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule 1 and active matrix metalloproteinase 9. Finally, surgery enhanced IgG extravasation in the hippocampus. These surgical effects were attenuated by PDTC. These results suggest that surgery, but not propofol-based anesthesia, induces neuroinflammation and impairment of learning and memory. PDTC attenuates these effects possibly by inhibiting NF-κB activation and the downstream matrix metalloproteinase 9 activity.

Keywords: neuroinflammation, nuclear factor κB, pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate, surgery, rat

Introduction

Postoperative cognitive dysfunction (POCD) is a significant clinical syndrome (Moller et al., 1998; Monk et al., 2008). It not only affects the quality of life of patients, but also is associated with increased mortality after surgery (Moller et al., 1998; Monk et al., 2008). Thus, it is urgently needed to identify the mechanisms for POCD and to develop strategies to prevent it.

Recent animal studies from our laboratory and others have strongly suggested the role of neuroinflammation in the development of cognitive dysfunction after surgery and/or exposure to volatile anesthetics (Cibelli et al., 2010; Lin and Zuo, 2011; Terrando et al., 2011; Cao et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2012; Shen et al., 2013). These previous studies have shown that surgery or anesthetics increase the expression of inflammatory cytokines and activation of microglia and/or infiltrated macrophages in the brain. Blocking the effects of inflammatory cytokines reduces cognitive dysfunction. However, many of these blocking methods used in animals are antibodies against cytokines or transgenic mice lacking certain components for cytokine responses (Cibelli et al., 2010; Terrando et al., 2011) and, therefore, have a low potential for clinical translation.

Nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) is a transcription factor that plays a central role in enhancing expression of cytokines (Liu et al., 1999). A recent study has implied that activation of NF-κB plays a role in the neuroinflammation after a tibial fracture and stabilization surgery because deletion of a NF-κB activation protein kinase reduces inflammatory cytokine production in mouse hippocampus (Terrando et al., 2011). However, it is not clear yet whether surgery activates NF-κB and whether inhibition of NF-κB attenuates cognitive impairment after surgery.

Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (PDTC) is a NF-κB inhibitor (Liu et al., 1999). Interestingly, dithiocarbamates are metal chelators and have been used in treating metal poisoning and fungal infections in humans. Also, PDTC has been evaluated as an antiviral agent for humans (Si et al., 2005). Pre-clinical toxicity study has shown that it is a safe drug (Chabicovsky et al., 2010). In this study, we used PDTC to test the hypothesis that postoperative impairment of learning and memory requires activation of NF-κB in the brain. We subjected rats to a carotid artery exploration, a procedure that often occurs during carotid endarterectomy. This surgery is frequently performed in the elderly, a patient population who is very susceptible to POCD (Monk et al., 2008).

Cyclophilin A has been shown to play a critical role in regulating inflammatory responses (Arora et al., 2005). A recent study has shown that activation of the cyclophilin A-NF-κB-matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) signaling pathway can significantly impair the cerebrovascular integrity (Bell et al., 2012). Since the increased permeability of blood-brain barrier (BBB) may be part of the neuropathology contributing to learning and memory impairment after surgery (Terrando et al., 2011), we also determined whether the cyclophilin A-NF-κB-MMP-9 signaling pathway was activated after the surgery in our study.

Materials and methods

The animal protocol was approved by the institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Virginia (Charlottesville, VA). All animal experiments were carried out in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH publications number 80–23) revised in 2011.

Animals

Four-month old male Fischer 344 rats weighing 290 – 330 g from Charles River Laboratories International Inc. (Wilmington, MA) were assigned to five groups: control group, anesthesia group, surgery group (equal volume of saline as vehicle for PDTC was given at corresponding time points), PDTC group and surgery plus PDTC group. PDTC solution was injected intraperitoneally at 50 mg/kg 30 min before and 6 h after surgery or at the corresponding times for the rats in the PDTC only group. PDTC solution (50 mg/ml) was prepared freshly by dissolving PDTC powder (P8765, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MI) in normal saline.

The learning and memory were started to be assessed by Barnes maze and fear conditioning tests at 6 days after animals were subjected to various conditions (n = 8 – 13 per group). In another experiment, separate rats under those five experimental conditions (n = 5 – 12 per condition) were sacrificed at 24 h after surgery to harvest brains for western blotting and immunohistochemistry.

Anesthesia and surgery

We performed a right carotid artery exploration surgery. Briefly, a rat was held in a box and the left or right lateral tail vein was cannulated with a 24G intravenous catheter. Propofol (APP Pharmaceuticals, Lake Zurich, IL) at 15 mg/kg was infused intravenously to induce anesthesia and then at a rate of 60 mg/kg/h to maintain anesthesia. After loss-of-righting reflex, 0.15 mg/kg buprenorphine hydrochloride (Recktt Benckiser Healthcare Ltd., Kingston-upon-Thames, UK) was injected subcutaneously. The rat was intubated with a 16-gauge catheter and mechanically ventilated with 100% O2. A 2.2-cm midline neck incision was made 10 min after the induction of anesthesia. The soft tissues over the trachea were retracted gently. One-centimeter long right common carotid artery was carefully dissected free from other tissues. Care was taken to avoid damage to the vagus nerve. The wound was then irrigated and closed using surgical suture. The surgical procedure was performed under sterile conditions and lasted for 15 min. After the surgery, the propofol infusion rate was reduced to 45 mg/kg/h. The infusion rate was further decreased to 30 mg/kg/h at 1.5 h after the initiation of anesthesia. The total duration of anesthesia was for 2 h. No response to toe pinching was observed during the anesthesia period. Propofol infusion was stopped at 2 h after the initiation of propofol infusion. Animals were extubated when righting reflex was recovered. During the anesthesia, rectal temperature was monitored and maintained at 37°C with the aid of servo-controlled warming blanket (TCAT-2LV, Physitemp instruments Inc., Clifton, NJ). Animals in the propofol-based anesthesia only group received propofol and buprenorphine in the same way as described here.

Barnes maze

Six days after being exposed to various experimental conditions, animals were subjected to Barnes maze as we previously described (Lin et al., 2011) to test their spatial learning and memory. Barnes maze is a circular platform with 20 equally spaced holes (SD Instruments, San Diego, CA). One of the holes was connected to a dark chamber that was called target box. The test started by placing animals in the middle of the Barnes maze. Aversive noise (85 dB) and bright light (200 W) shed on the platform were used to encourage rats to find this box. Animals were trained in a spatial acquisition phase that took 4 days with 3 min per trial, 4 trials per day and 15 min between each trial. Their reference memory was tested on day 5 (short-term retention) and day 12 (long-term retention). Each animal had one trial on each of these two days. No test was performed during the period from day 5 to day 12. The latency to find the target box during each trial was recorded with the assistance of ANY-Maze video tracking system (SD Instruments).

Fear conditioning

Rats were subjected to fear conditioning test as we previously described (Lin et al., 2011) at 24 h after the Barnes maze test. Each animal was placed in a test chamber wiped with 70% alcohol and subjected to 3 tone-foot shock pairings (tone: 2000 Hz, 85 db, 30 s; foot shock: 1 mA, 2 s) with an intertrial interval 1 min in a relatively dark room. Animal was removed from this test chamber 30 s after the conditioning training. Twenty-four hours later, the animal was placed back to the same chamber for 8 min without the tone and shock. The amount of time with freezing behavior was recorded in an 8 s interval. The animal was placed 2 h later in a test chamber that was different in context and smell from the first test chamber (this second chamber was wiped with 1% acetic acid) in a relatively light room. Freezing behavior was recorded for 3 min without any stimuli. The tone stimulus then was turned on for 3 cycles, each cycle for 30 s followed by 1-min inter-cycle interval (total 4.5 min). The freezing behavior in this 4.5 min was recorded. Freezing behavior recorded in the video was scored by an observer who was blind to group assignment of animals.

Brain tissue harvest

Rats were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane and perfused transcardially with saline at 24 h after being exposed to various experimental conditions. Brains were harvested. The left hippocampus was dissected out immediately for Western blotting. The right cerebral hemisphere at Bregma -3 to -6 mm was used for immunohistochemistry. In another experiment, the hippocampi of rats were harvested in the same way 30 min after the completion of cognitive tests (21 days after the surgery) for immunohistochemistry and Western blotting.

Preparation of cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins

The cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins were prepared as we described before (Li et al., 2013). Briefly, hippocampus tissues were homogenized in a buffer containing 10 mM HEPES, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol and 0.05% NP40 (pH 7.9) as well as protease inhibitor cocktail (10 mg/ml aproteinin, 5 mg/ml pepstatin, 5 mg/ml leupeptin, and 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonylfluoride) and incubated on ice for 10 min. The homogenates were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was kept as the fraction containing cytoplasmic proteins. The resulted pellet was resuspended in a buffer containing 5 mM HEPES, 300 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol and 26% glycerol (v/v) (pH 7.9) and was homogenized with 20 full strokes in a glass homogenizer. They were left on ice for 30 min and then centrifuged at 24,000 g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant was harvested as the fraction containing nuclear proteins. The protein concentration was determined by the Bradford assay.

Western blot analysis

Fifty microgram proteins per lane were separated on a polyacrylamide gel. The proteins were then transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The membranes were blocked with Protein-Free T20 Blocking Buffer (#37573, Thermo Scientific, Logan, UT) and incubated with the following primary antibodies overnight at 4°C: rabbit monoclonal anti-NF-κB p65 antibody (1:1000, #8242, Cell signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), rabbit polyclonal anti-histone H3 antibody (1:1000, #9715, Cell signaling Technology), rabbit polyclonal anti-IL-6 (1:1000, ab6672, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), rabbit polyclonal anti-IL-1β (1:1000, ab15077, Abcam), rabbit polyclonal anti-cyclophilin A (1:1000, ab41684, Abcam), rabbit polyclonal anti-MMP-9 (1:500, ARP33090_T100, Aviva Systems Biology, San Diego, CA), rabbit monoclonal anti-inhibitor of κB (IκB)α antibody (1:100, #4812, Cell signaling Technology), and rabbit polyclonal anti-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (1:5000, G9545, Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MI). Appropriate secondary antibodies were used. Protein bands were visualized by Genesnap version 7.08 and quantified by Genetools version 4.01. The results of nuclear NF-κB p65 were normalized to those of H3. The data of cytoplasmic cyclophilin A, MMP-9, IL-1β and IL-6 were normalized to those of GAPDH. The results from animals under various experimental conditions then were normalized by the mean values of corresponding control animals.

Immunohistochemistry

BBB disruption was assessed by IgG immunostaining as previously described (Wang et al., 2011; He et al., 2012). Brains were harvested, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline at 4°C for 18 h and embedded in paraffin. Hippocampal coronal sections at 5 μm were cut sequentially at Bregma -3 to -6 mm and mounted on slides. Antigen retrieval was performed in Tris/EDTA buffer (10 mM Tris base, 1 mM EDTA, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 9.0) at 95 – 100°C for 20 min. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked with 0.3% H2O2 for 30 min. The slides were immersed in 5% normal goat serum with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) for 2 h at room temperature. The sections were incubated with biotinylated goat anti-rat IgG (1:200; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with an avidin-biotin-HRP complex reagent (1:200, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) at room temperature for 2 h. The staining was developed with DAB method.

To stain ionized calcium binding adapter molecule 1(Iba-1), the antigen retrieval was performed as described above. Sections were washed in TBS plus 0.025% triton-X 100 and then blocked in 10% donkey serum with 1% BSA in TBS for 2 h at room temperature. The sections were incubated at 4°C overnight with rabbit polyclonal anti-Iba-1 (1:500, 019-19741, Wako Chemicals USA, Richmond, VA). Sections were rinsed in TBS with 0.025% triton-X 100. The donkey anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with NL557 (1:200, NL004, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) were applied and incubated for 1 h at room temperature in a dark room. After washed in TBS, sections were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (#62249, Thermo Scientific), rinsed, and mounted with Vectashield mounting medium (H-1000, Vector labs). Images were acquired with a fluorescence microscope with a CCD camera. A negative control omitting the incubation with the primary antibody was included in all experiments.

For quantification, 3 independent microscopic fields in each section were randomly acquired in the hippocampal CA3 or dentate gyrus area using a counting frame size of 0.4 mm2 (Terrando et al., 2011). Three sections per rat were imaged. The number of pixels per image with intensity above a predetermined threshold level was considered to be positively stained areas. This measurement was performed by using Image J 1.47n software. The degree of positive immunoreactivity was reflected by the percentage of the positively stained area in the total area of interested structure in the imaged field. All quantitative analyses were performed in a blinded fashion.

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as mean ± S.D. (n ≥ 5). Data from the training sessions of Barnes maze were analyzed by two-way repeated measures of variance followed by Tukey test. The other data were tested by one way analysis of variance followed by Tukey test or one way analysis of variance on ranks followed by Dunn’s method. Differences were considered significant at a p ≤ 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed with SigmaStat (Systat Software, Inc., Point Richmond, CA, USA).

Results

PDTC attenuated surgery-induced learning and memory impairment

No rats had an episode of hypoxia (pulse oximeter oxygen saturation < 90%) during surgery or anesthesia. All rats survived until the end of the study.

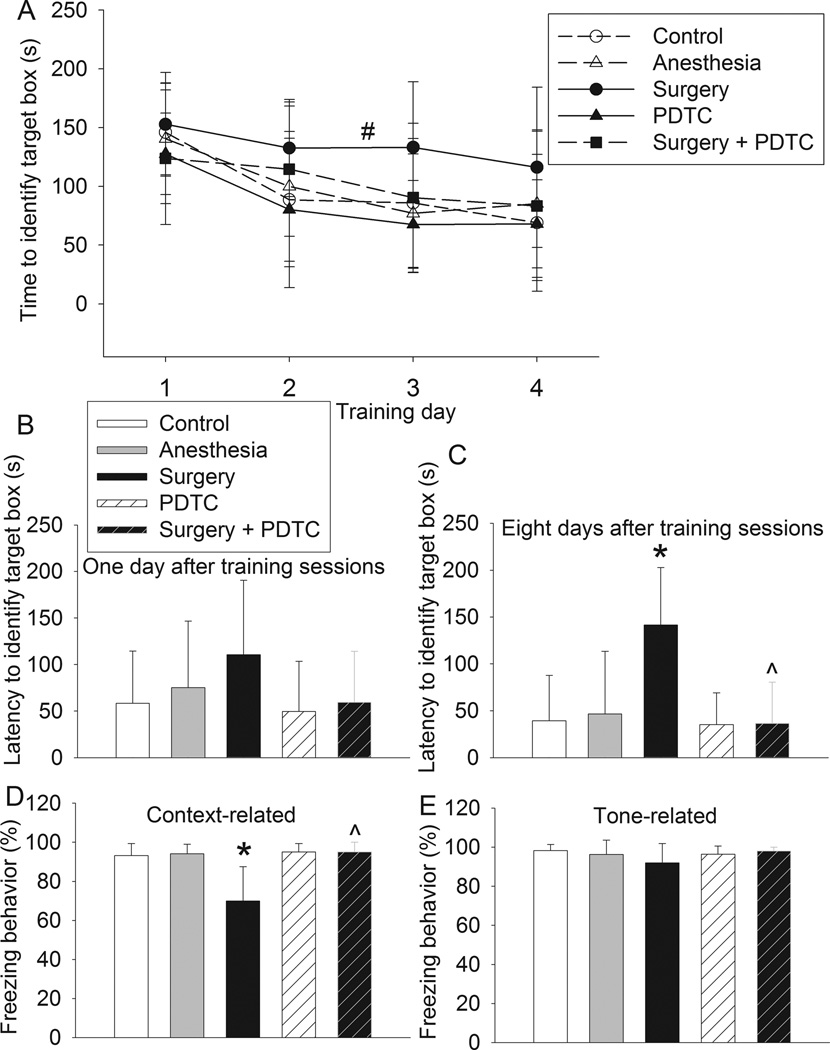

During the Barnes maze test, training sessions had a main effect on the time needed to identity the target hole [F(1,3) = 10.692, P < 0.001]. Neither anesthesia nor PDTC alone had a significant effect on the latency to identify the target hole. However, surgery had a significant effect on this latency [F(1,24) = 6.544, P = 0.017]. This surgical effect was abolished by PDTC [F(1,3) = 0.127, P = 0.725; comparison between control group and surgery plus PDTC group]. Surgery also significantly increased the latency to identify the target hole when tested at 8 days after the training sessions. This effect was abolished by PDTC. Although a similar pattern of changes occurred when the tests were performed at 1 day after the training sessions, the changes were not statistically significant (Figs. 1A to 1C).

Fig. 1. PDTC attenuated surgery-induced learning and memory impairment.

Four-month old Fischer 344 rats were subjected to or not subjected to right carotid artery exploration under propofol-buprenorphine anesthesia. Anesthesia was for 2 h. They were tested by Barnes maze 6 days later and fear conditioning 18 days later. A: performance in the training sessions of Barnes maze. # P = 0.017 compared with control rats by two-way repeated measures analysis of variance. B and C: latency to identify the target hole at 1 day or 8 days after the training sessions. D and E: performance in fear conditioning. Results are mean ± S.D. (n = 8 – 13). * P < 0.05 compared with control. ^ P < 0.05 compared with surgery.

Rats in the surgery group had decreased freezing behavior in the context-related fear conditioning test when compared with control animals. This decrease was attenuated by PDTC. PDTC alone did not affect the context-related freezing behavior. However, the tone-related freezing behavior was not affected by any experimental conditions (Figs. 1D and 1E). These results suggest that surgery impairs hippocampus-dependent learning and memory (context-related) but does not significantly affect hippocampus-independent learning and memory (tone-related) (Kim et al., 2009).

PDTC attenuated surgery-induced NF-κB activation and neuroinflammation at 24 h after surgery

No experimental conditions affected the expression of cyclophilin A in the hippocampus (Figs. 2A and 2B). However, surgery but not anesthesia alone significantly increased the nuclear expression of p65, a component of NF-κB. This increase was attenuated by PDTC. PDTC alone did not affect the amount of p65 in the nuclei (Figs. 2A and 2C). Similar pattern of changes occurred to IL-1β and IL-6 in the hippocampus (Figs. 2A, 2D and 2E). Surgery also decreased cytoplasmic IκB (control: 1.00 ± 0.31 vs. surgery: 0.47 ± 0.10 of the control, n = 5, P = 0.04). This decrease was abolished by PDTC (1.19 ± 0.41 of the control, n = 5, P = 0.006 vs. surgery group). Two protein bands at ~92 and 78 kDa were detected by the anti-MMP-9 antibody. These molecular weights correspond to these of pro-MMP-9 and active MMP-9, respectively (Bell et al., 2012). The expression of pro-MMP-9 was not changed by any experimental conditions. On the other hand, surgery increased the active MMP-9, which was inhibited by PDTC (Figs. 2A, 2F and 2G).

Fig. 2. PDTC attenuated surgery-induced nuclear translocation of p65 and expression of IL-1β, IL-6 and active MMP-9.

Four-month old Fischer 344 rats were subjected to or not subjected to right carotid artery exploration under propofol-buprenorphine anesthesia. Anesthesia was for 2 h. Hippocampus was harvested 24 h later. Nuclear fraction and whole tissue lysates were prepared to detect p65 and other proteins by Western blotting. A: representative Western blot images. B to G: graphic presentation of cyclophilin A, p65, IL-1β, IL-6, pro-MMP-9 and active MMP-9 protein abundance. Values are expressed as fold changes over the mean values of control rats and are presented as mean ± S.D. (n = 5). * P < 0.05 compared with control. ^ P < 0.05 compared with surgery. Con: control, Anes: anesthesia, Sur: surgery.

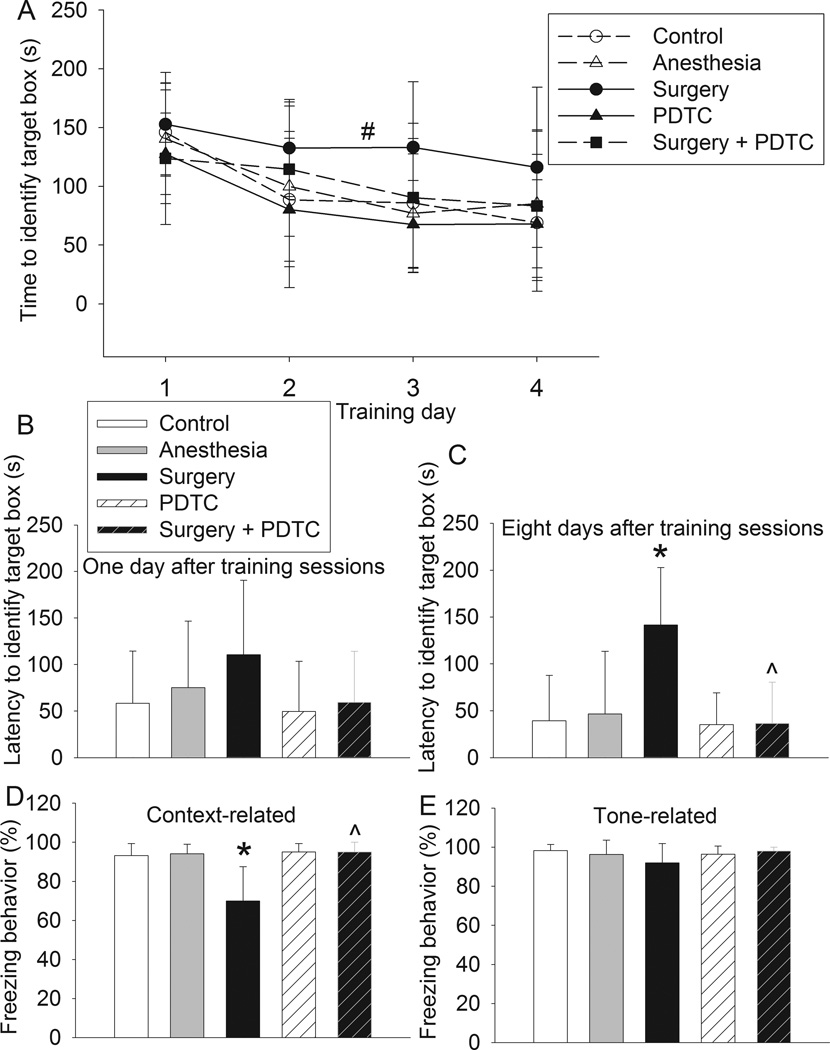

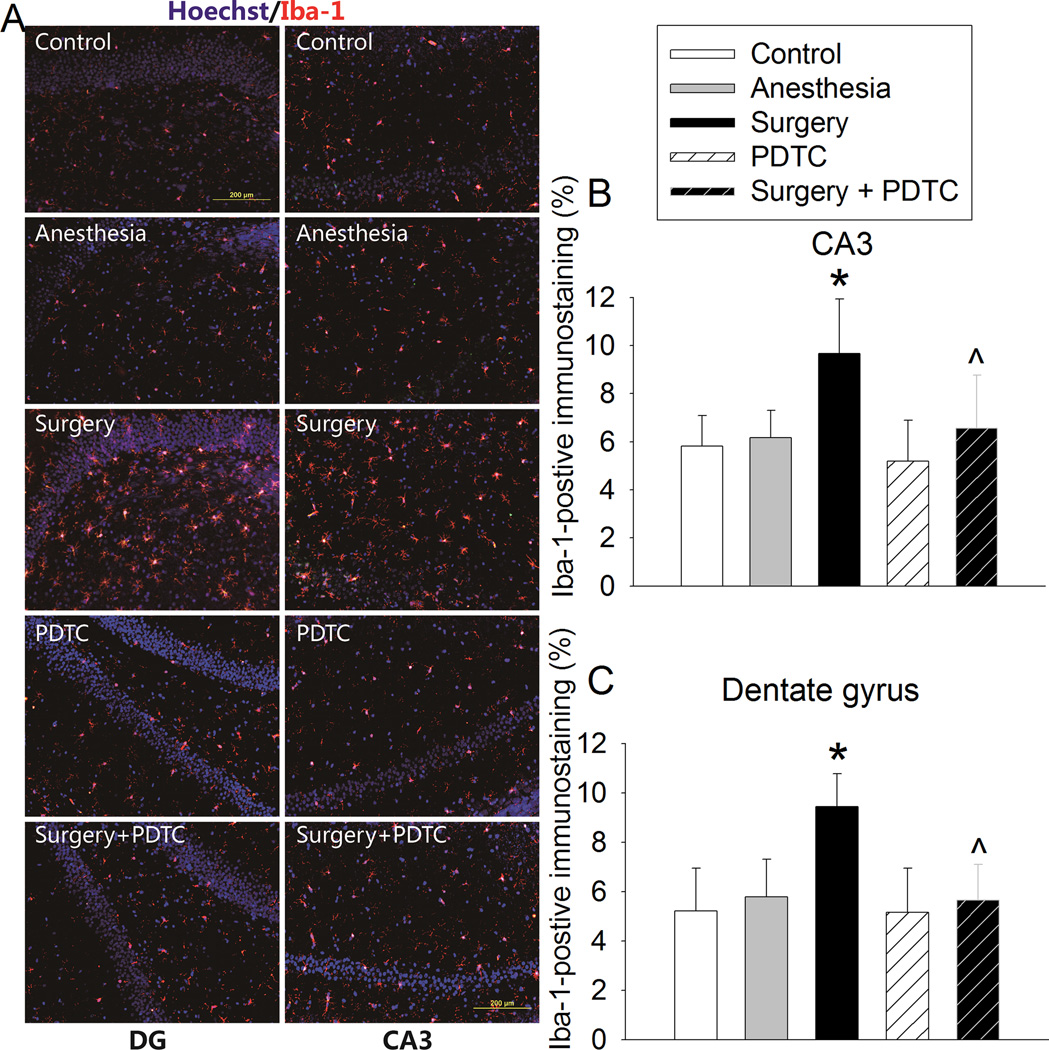

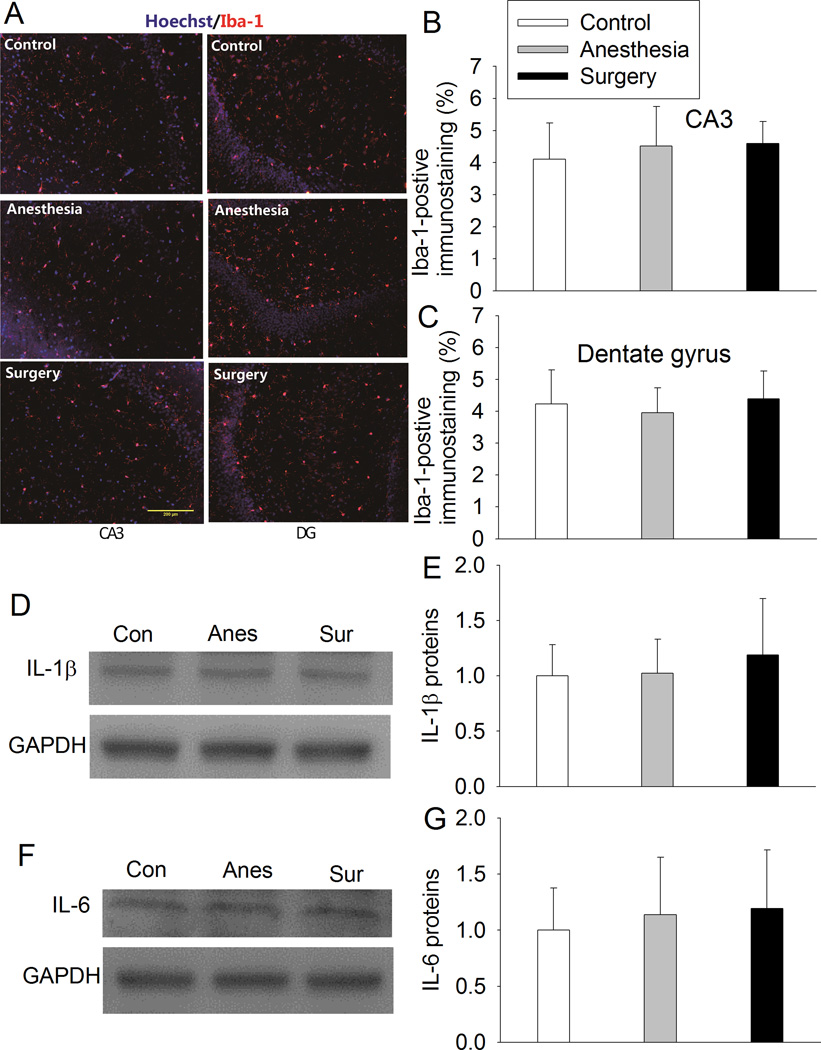

The Iba-1 immune intensity in CA3 and dentate gyrus was significantly increased by surgery. This increase was inhibited by PDTC (Fig. 3). Also, surgery increased IgG extravasation in CA3, which was inhibited by PDTC (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3. PDTC attenuated surgery-induced increase of Iba-1 expression.

Four-month old Fischer 344 rats were subjected to or not subjected to right carotid artery exploration under propofol-buprenorphine anesthesia. Anesthesia was for 2 h. Brain was harvested 24 h later for immunostaining of Iba-1. A: representative immunostaining images. B and C: graphic presentation of the percentage area that is Iba-1-postive staining in the CA3 and dentate gyrus. Values presented as mean ± S.D. (n = 10 – 12). * P < 0.05 compared with control. ^ P < 0.05 compared with surgery.

Fig. 4. PDTC attenuated surgery-induced IgG extravasation in the hippocampal CA3.

Four-month old Fischer 344 rats were subjected to or not subjected to right carotid artery exploration under propofol-buprenorphine anesthesia. Anesthesia was for 2 h. Brain was harvested 24 h later for immunostaining of IgG. A: representative immunostaining images. B: graphic presentation of the percentage area that is IgG-positive staining in the hippocampus. Values presented as mean ± S.D. (n = 9). * P < 0.05 compared with control. ^ P < 0.05 compared with surgery.

Surgery might not induce persistent neuroinflammation

Neither anesthesia nor surgery plus anesthesia affected the Iba-1 immune intensity in the CA3 and dentate gyrus at 21 days after the surgery (Figs. 5A to 5C). Similarly, anesthesia or surgery plus anesthesia did not change the expression of IL-1β and IL-6 in the hippocampus at this time point (Figs. 5D to 5G).

Fig. 5. Surgery did not induce persistent neuroinflammation.

Four-month old Fischer 344 rats were subjected to or not subjected to right carotid artery exploration under propofol-buprenorphine anesthesia. Anesthesia was for 2 h. Hippocampus was harvested 21 days later. A: representative immunostaining images of Iba-1. B and C: graphic presentation of the percentage area that is Iba-1-postive staining in the CA3 and dentate gyrus. D and F: representative Western blot images of IL-1β and IL-6. E and G: graphic presentation of IL-1β and IL-6 protein abundance. Values are expressed as fold changes over the mean values of control rats and are presented as mean ± S.D. (n = 6). Con: control, Anes: anesthesia, Sur: surgery.

Discussion

Animal studies have suggested that neuroinflammation plays a critical role in the learning and memory impairment after surgery and/or anesthesia (Cibelli et al., 2010; Lin and Zuo, 2011; Terrando et al., 2011; Cao et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2012; Shen et al., 2013). A human study suggests that surgery induces neuroinflammation (Tang et al., 2011). Since NF-κB is a major transcription factor to regulate the expression of inflammatory mediators, such as cytokines (Liu et al., 1999), activation of NF-κB may be a critical step to lead to neuroinflammation and cognitive dysfunction after surgery. Indeed, mice with deletion of IκB kinase, a NF-κB activation kinase, in the microglia and bone marrow-derived macrophages have no significant inflammation in the hippocampus after tibial surgery (Terrando et al., 2011). However, it is not known whether surgery activates NF-κB in the brain and whether interfering the activation or activity of NF-κB can attenuate the cognitive dysfunction after surgery. Also, IκB kinase can phosphorylate proteins other than IκB (Reiley et al., 2005). Phosphorylation of IκB releases its binding with NF-κB, which allows nuclear translocation of NF-κB so that NF-κB can regulate the expression of its downstream proteins (Gilmore, 2006). Here, we showed that surgery increased the nuclear expression of p65, a NF-κB subunit (Li et al., 2013), suggesting that surgery activates NF-κB. PDTC, a known NF-κB activation inhibitor (Liu et al., 1999), reduced surgery-induced p65 nuclear translocation, inflammatory cytokine production, neuroinflammatory and cognitive impairment. These results strongly suggest a critical role of NF-κB activation in the surgery-induced neuroinflammation and dysfunction of learning and memory.

PDTC has been shown to inhibit NF-κB activation induced by various factors (Schreck et al., 1992; Liu et al., 1999). PDTC does not inhibit activation of the transcription factors activator protein 1, specificity protein 1 and cAMP response element binding protein (Liu et al., 1999), suggesting its specificity on NF-κB. The mechanisms for PDTC to inhibit NF-κB are not fully understood but may be due to its metal chelating and antioxidant properties that may reduce the release of NF-κB from the binding with its inhibitor IκB (Schreck et al., 1992). Inactivated NF-κB binds to IκB in the cytoplasm. Interruption of this binding frees NF-κB for nuclear translocation and the degradation of IκB (Jacobs and Harrison, 1998). Consistent with these findings, surgery reduced cytoplasmic IκBα and PDC attenuated these changes.

Cyclophilin A is an abundant cytosolic protein with a molecular weight at ~18 kDa. It is an important regulator of inflammatory responses (Arora et al., 2005). A recent study suggests that activation of cyclophilin A-NF-κB-MMP-9 signaling pathway in the pericytes contributes to the apolipoprotein E4-associated BBB breakdown ((Bell et al., 2012). Our study showed that surgery did not increase cyclophilin A expression, indicating that surgery may not activate NF-κB through cyclophilin A in the brain. Since tibial surgery in mice can disrupt the integrity of BBB (Terrando et al., 2011), the peripheral inflammatory cytokines and cells can permeate into brain parenchyma to activate NF-κB in the brain tissues.

Our results showed that the IgG extravasation was significantly increased by surgery, suggesting the disruption of the BBB. MMP-9 is a major gelatinase and collagenase and is known to be involved in the breakdown of the BBB under pathological conditions, such as brain ischemia (Asahi et al., 2000). Our results showed that surgery increased active MMP-9 expression and that PDTC inhibited this increase and the increase of IgG extravasation. These results, together with the previous findings in the literature (Asahi et al., 2000), suggest that activation of NF-κB-MMP-9 contributes to the disruption of the BBB.

We and others have provided evidence for a critical role of neuroinflammation in the cognitive impairment after surgery and anesthesia (Cibelli et al., 2010; Lin and Zuo, 2011; Terrando et al., 2011; Cao et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2012; Shen et al., 2013). Isoflurane anesthesia for 2 h increased IL-1β in the hippocampus and induced cognitive impairment in rodents but failed to induce cognitive impairment in IL-1β deficient mice (Cao et al., 2012). IL-1 receptor antagonist prevented cognitive impairment after surgery in rodents (Cibelli et al., 2010; Barrientos et al., 2012). Higher circulating IL-6 levels were associated with worse cognitive function and steeper cognitive decline in aged humans (Mooijaart et al., 2013). These findings suggest a role of IL-1β and IL-6 in learning and memory impairment. Consistent with this suggestion, we showed here that surgery increased IL-1β and IL-6 in the hippocampus and induced cognitive impairment and that PDTC attenuated these changes. However, a study has shown that laparotomy significantly increased IL-1β mRNA in the hippocampus of 23 – 25 month old mice. Laparotomy did not affect the basic performance of these aged mice in Morris water maze but these mice had poorer performance during the reversal testing in the maze. The authors concluded that laparotomy induces significant neuroinflammation but does not lead to significant learning and memory impairment (Rosczyk et al., 2008). On the contrary, a recent study showed that laparotomy increased IL-1 proteins in the hippocampus and impaired cognitive function as measured by fear conditioning in 24 month old rats. These findings seem different but actually are consistent because the study with using aged mice showed cognitive impairment after surgery as well (Barrientos et al., 2012).

We used propofol plus buprenorphine to provide surgical anesthesia in this study. No animals moved in response to surgical stimulation under anesthesia. The animals exposed to anesthesia only performed as well as control animals in the Barnes maze and fear conditioning. Anesthesia alone also did not change the expression of Iba-1, IL-1β and IL-6. These results suggest that propofol-based general anesthesia at surgical anesthesia level for 2 h did not cause cognitive impairment and neuroinflammation. Interestingly, propofol has been shown to reduce lipopolysaccharide-induced proinflammatory cytokine production in microglial and macrophage cultures (Wu et al., 2009; Gui et al., 2012). It is not known whether propofol anesthesia has partly inhibited surgery-induced neuroinflammation in our study. This effect is difficult to assess because it is not possible to perform surgery without anesthesia and other general anesthetics, such as isoflurane, can also affect NF-κB activity and inflammatory cytokine production (Li et al., 2013). Since surgery under propofol and buprenorphine anesthesia still induced significant neuroinflammation in our study, these results suggest that surgery-induced neuroinflammation is not completely inhibited by propofol even if propofol provides significant inhibition on neuroinflammation under this in vivo condition.

Our results showed that the expression of Iba-1, IL-1β and IL-6 was not increased in the hippocampus of rats at 21 days after surgery, suggesting that surgery did not induce persistent neuroinflammation. Apparently, rats still had cognitive impairment at this time point. These results suggest that neuroinflammation may induce secondary event(s) for cognitive impairment to occur in a delayed phase. For example, incubation with IL-1β for 24 h induces synapse loss in rat hippocampal neuronal cultures (Mishra et al., 2012). Proinflammatory cytokines also reduce stimulation-induced brain derived neurotrophic factor production in rat hippocampus (Gonzalez et al., 2013). Nevertheless, our results suggest that surgery-induced neuroinflammation plays a critical role in initiating the processes to lead to the delayed phase of learning and memory impairment because PDTC that was given only on the day of surgery attenuated the neuroinflammation and cognitive impairment after surgery.

We performed carotid artery exploration in this study. This is a necessary part of carotid endarterectomy in humans. Care was taken not to occlude the carotid artery anytime so that significant brain ischemia and the subsequent ischemic brain injury will not occur. This model creates a pure aseptic surgical trauma, and has a minimal blood loss and direct effects on immune system.

Obviously, it is not appropriate to extrapolate our findings in rats directly to humans. In addition to the species difference, studies including ours do not exactly simulate clinical situation of POCD. For example, not all patients will develop POCD (Moller et al., 1998; Monk et al., 2008). It will be extremely valuable if we can identify the patients who will develop POCD before or during surgery and work on these patients. However, animal studies consider all animals in a study group the same and do not include pre-surgery and post-surgery cognitive tests to really identify individual animals that have impairment of learning and memory after surgery. This practice in animal study is due to the concern of learning effects if animals are repeatedly tested by the same learning and memory paradigms. Better design on animal tests may more closely simulate human situation in the future.

In summary, we have shown that surgery but not propofol-based general anesthesia induces neuroinflammation and impairment of learning and memory in rats. These effects of surgery may be mediated by activation of NF-κB. Inhibition of NF-κB pathway by small molecules, such as PDTC, may be an effective and practical intervention for reducing surgery-induced neuroinflammation and cognitive dysfunction.

Highlights.

Surgery but not propofol anesthesia induces neuroinflammation and cognitive impairment

Surgery-induced neuroinflammation and cognitive impairment may be mediated by NF-κB

PDTC attenuated surgery-induced neuroinflammation and cognitive impairment

Acknowledgments

Grant support: This study was supported by grants (R01 GM065211 and R01 GM098308 to Z Zuo) from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, by a grant from the International Anesthesia Research Society (2007 Frontiers in Anesthesia Research Award to Z Zuo), Cleveland, OH, by a Grant-in-Aid from the American Heart Association Mid-Atlantic Affiliate (10GRNT3900019 to Z Zuo), Baltimore, MD, and the Robert M. Epstein Professorship endowment, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA.

Abbreviations

- BBB

blood-brain barrier

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- IκB

inhibitor of κB

- MMP-9

matrix metalloproteinase 9

- NF-κB

nuclear factor κB

- PDTC

pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate

- POCD

postoperative cognitive dysfunction

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure/conflict of interest: The authors declare no other financial supports for this study except for those grants stated above from funding agencies for non-profit. The authors also declare no conflict of interest in the content of this study.

References

- Arora K, Gwinn WM, Bower MA, Watson A, Okwumabua I, MacDonald HR, Bukrinsky MI, Constant SL. Extracellular cyclophilins contribute to the regulation of inflammatory responses. J Immunol. 2005;175:517–522. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahi M, Asahi K, Jung JC, del Zoppo GJ, Fini ME, Lo EH. Role for matrix metalloproteinase 9 after focal cerebral ischemia: effects of gene knockout and enzyme inhibition with BB-94. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:1681–1689. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200012000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos RM, Hein AM, Frank MG, Watkins LR, Maier SF. Intracisternal interleukin-1 receptor antagonist prevents postoperative cognitive decline and neuroinflammatory response in aged rats. J Neurosci. 2012;32:14641–14648. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2173-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RD, Winkler EA, Singh I, Sagare AP, Deane R, Wu Z, Holtzman DM, Betsholtz C, Armulik A, Sallstrom J, Berk BC, Zlokovic BV. Apolipoprotein E controls cerebrovascular integrity via cyclophilin A. Nature. 2012;485:512–516. doi: 10.1038/nature11087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao L, Li L, Lin D, Zuo Z. Isoflurane induces learning impairment that is mediated by interleukin 1beta in rodents. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51431. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabicovsky M, Prieschl-Grassauer E, Seipelt J, Muster T, Szolar OH, Hebar A, Doblhoff-Dier O. Pre-clinical safety evaluation of pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;107:758–767. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2010.00573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cibelli M, Fidalgo AR, Terrando N, Ma D, Monaco C, Feldmann M, Takata M, Lever IJ, Nanchahal J, Fanselow MS, Maze M. Role of interleukin-1beta in postoperative cognitive dysfunction. Ann Neurol. 2010;68:360–368. doi: 10.1002/ana.22082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore TD. Introduction to NF-kappaB: players, pathways, perspectives. Oncogene. 2006;25:6680–6684. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez P, Machado I, Vilcaes A, Caruso C, Roth GA, Schioth H, Lasaga M, Scimonelli T. Molecular mechanisms involved in interleukin 1-beta (IL-1beta)-induced memory impairment. Modulation by alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (alpha-MSH) Brain Behav Immun. 2013;34:141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gui B, Su M, Chen J, Jin L, Wan R, Qian Y. Neuroprotective effects of pretreatment with propofol in LPS-induced BV-2 microglia cells: role of TLR4 and GSK-3beta. Inflammation. 2012;35:1632–1640. doi: 10.1007/s10753-012-9478-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He HJ, Wang Y, Le Y, Duan KM, Yan XB, Liao Q, Liao Y, Tong JB, Terrando N, Ouyang W. Surgery upregulates high mobility group box-1 and disrupts the blood-brain barrier causing cognitive dysfunction in aged rats. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2012;18:994–1002. doi: 10.1111/cns.12018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs MD, Harrison SC. Structure of an IkappaBalpha/NF-kappaB complex. Cell. 1998;95:749–758. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81698-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JA, Li L, Zuo Z. Isoflurane induces a postconditioning effect on bovine pulmonary arterial endothelial cells exposed to oxygen-glucose deprivation. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;615:144–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Yin J, Li L, Deng J, Feng C, Zuo Z. Isoflurane postconditioning reduces ischemia-induced nuclear factor-kappaB activation and interleukin 1beta production to provide neuroprotection in rats and mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;54:216–224. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D, Cao L, Wang Z, Li J, Washington JM, Zuo Z. Lidocaine attenuates cognitive impairment after isoflurane anesthesia in old rats. Behav Brain Res. 2012;228:319–327. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D, Li G, Zuo Z. Volatile anesthetic post-treatment induces protection via inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta in human neuron-like cells. Neurosci. 2011;179:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.01.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D, Zuo Z. Isoflurane induces hippocampal cell injury and cognitive impairments in adult rats. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61:1354–1359. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu SF, Ye X, Malik AB. Inhibition of NF-kappaB activation by pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate prevents In vivo expression of proinflammatory genes. Circulation. 1999;100:1330–1337. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.12.1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra A, Kim HJ, Shin AH, Thayer SA. Synapse loss induced by interleukin-1beta requires pre- and post-synaptic mechanisms. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2012;7:571–578. doi: 10.1007/s11481-012-9342-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller JT, Cluitmans P, Rasmussen LS, Houx P, Rasmussen H, Canet J, Rabbitt P, Jolles J, Larsen K, Hanning CD, Langeron O, Johnson T, Lauven PM, Kristensen PA, Biedler A, van Beem H, Fraidakis O, Silverstein JH, Beneken JE, Gravenstein JS. Long-term postoperative cognitive dysfunction in the elderly ISPOCD1 study. ISPOCD investigators. International Study of Post-Operative Cognitive Dysfunction. Lancet. 1998;351:857–861. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)07382-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk TG, Weldon BC, Garvan CW, Dede DE, van der Aa MT, Heilman KM, Gravenstein JS. Predictors of cognitive dysfunction after major noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:18–30. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000296071.19434.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooijaart SP, Sattar N, Trompet S, Lucke J, Stott DJ, Ford I, Jukema JW, Westendorp RG, de Craen AJ, Group PS. Circulating interleukin-6 concentration and cognitive decline in old age: the PROSPER study. J Intern Med. 2013;274:77–85. doi: 10.1111/joim.12052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiley W, Zhang M, Wu X, Granger E, Sun SC. Regulation of the deubiquitinating enzyme CYLD by IkappaB kinase gamma-dependent phosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:3886–3895. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.10.3886-3895.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosczyk HA, Sparkman NL, Johnson RW. Neuroinflammation and cognitive function in aged mice following minor surgery. Exp Gerontol. 2008;43:840–846. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreck R, Meier B, Mannel DN, Droge W, Baeuerle PA. Dithiocarbamates as potent inhibitors of nuclear factor kappa B activation in intact cells. J Exp Med. 1992;175:1181–1194. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.5.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X, Dong Y, Xu Z, Wang H, Miao C, Soriano SG, Sun D, Baxter MG, Zhang Y, Xie Z. Selective anesthesia-induced neuroinflammation in developing mouse brain and cognitive impairment. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:502–515. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182834d77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Si X, McManus BM, Zhang J, Yuan J, Cheung C, Esfandiarei M, Suarez A, Morgan A, Luo H. Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate reduces coxsackievirus B3 replication through inhibition of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. J Virol. 2005;79:8014–8023. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.13.8014-8023.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang JX, Baranov D, Hammond M, Shaw LM, Eckenhoff MF, Eckenhoff RG. Human Alzheimer and inflammation biomarkers after anesthesia and surgery. Anesthesiology. 2011;115:727–732. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31822e9306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrando N, Eriksson LI, Ryu JK, Yang T, Monaco C, Feldmann M, Jonsson Fagerlund M, Charo IF, Akassoglou K, Maze M. Resolving postoperative neuroinflammation and cognitive decline. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:986–995. doi: 10.1002/ana.22664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Leng Y, Tsai LK, Leeds P, Chuang DM. Valproic acid attenuates blood-brain barrier disruption in a rat model of transient focal cerebral ischemia: the roles of HDAC and MMP-9 inhibition. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31:52–57. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu GJ, Chen TL, Chang CC, Chen RM. Propofol suppresses tumor necrosis factor-alpha biosynthesis in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages possibly through downregulation of nuclear factor-kappa B-mediated toll-like receptor 4 gene expression. Chem Biol Interact. 2009;180:465–471. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]