Abstract

In the 9 years since the last World Health Organization (WHO) classification for head and neck tumors, a great deal has changed. In particular, human papillomavirus (HPV) has emerged as the major etiologic agent and patient prognostic marker for squamous cell carcinoma, most profoundly in the oropharynx. It also casts a long shadow over all of the rest of head and neck cancer given its biologic and prognostic implications. By contrast, little has changed regarding our knowledge of Epstein–Barr virus in head and neck cancers, except as it relates to HPV in nonkeratinizing-type nasopharyngeal carcinomas. This article discusses some of the major advances in our understanding of virus-related squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck and suggests several specific concepts and terminology for incorporation into the next WHO classification.

Keywords: Squamous cell carcinoma, Human papillomavirus, Epstein–Barr virus, World Health Organization, Classification, p16

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) tumor classification series of books has been instrumental for pathologists and clinicians to understand and categorize human tumors. The most recent head and neck “Blue Book” (as they are often called) was published in 2005 by an expert panel of pathologists [1]. However, over the last 9 years, much has changed in our understanding of these tumors. One of the greatest changes is in the recognition and characterization of human papillomavirus (HPV) in a subset of carcinomas, particularly in squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) of the oropharynx. HPV now casts a very large shadow over head and neck oncology, being present in transcriptionally-active (and clinically important) form in as many as 1/3rd of all head and neck SCC [2–4], with the vast majority arising from tonsillar crypt epithelium of the palatine tonsils and tongue base. As many as 12,000 new cases of HPV-related oropharyngeal SCC were reported yearly from 2004 to 2008 in the United States [2]. It has increased by as much as 225 % in the past 20–30 years while typical head and neck SCC has decreased by approximately 50 % [4].

Our understanding of the biology of HPV-related tumors has resulted in great advances in their diagnosis, classification, and treatment since the last WHO classification was formulated. The presence of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), on the other hand, has long been recognized in a subset of nasopharyngeal carcinomas with little change over the last decade, other than how it relates to HPV-related nasopharyngeal SCC cases. This article will discuss progress that has been made in our understanding of HPV-related carcinomas and suggest several specific concepts and terminology for incorporation into the new WHO classification of head and neck tumors.

Discussion

Oropharyngeal Carcinomas

Suggestion #1

Separate oral cavity and oropharyngeal tumors and discuss p16 positive/HPV-related oropharyngeal SCC in its own unique section, separate from conventional SCC.

The current WHO classification combines tumors of the oral cavity and oropharynx into one chapter [1]. In the past, and particularly before the rise in HPV-related tumors, this probably was appropriate given the similar morphology, biology, and prognosis of oral cavity and oropharyngeal SCC. However, HPV-related oropharyngeal SCC arising from the tonsillar crypts is biologically and clinically distinct with dramatic differences in prognosis and emerging differences in treatment [3]. Given the ever increasing recognition of the distinct biology of SCC and many other neoplasms by their anatomic subsite and the increasing number of entities, such as verrucous carcinoma, that typically arise in the oral cavity but almost never occur in the oropharynx, the WHO should have separate sections for tumors of the oral cavity and oropharynx. There should also be a separate sub-section of the oropharynx chapter entitled “HPV-related SCC”.

Suggestion #2

Recommend testing of all new primary oropharyngeal SCCs for p16 immunohistochemistry, possibly combined with an HPV-specific test, because patients with HPV-related tumors have favorable outcomes, can potentially be managed differently within the spectrum of current standard of care treatments, and can be properly counseled regarding prognosis.

The clinical significance of transcriptionally-active high risk HPV in patients with primary oropharyngeal SCC is now well established [3, 4]. Patients have better response to treatment and improved survival. Although there are no direct comparative studies, it is believed that oncologic outcomes are essentially comparable regardless of treatment approach, whether it be primary surgical (with pathologically-driven decision making for adjuvant therapy) or non-surgical. While there is extensive speculation about de-intensifying treatments in HPV positive oropharyngeal SCC patients due to their favorable prognosis, at our present state of knowledge (and this cannot be stated emphatically enough), these patients must still be treated within the confines of current standard of care for oropharyngeal cancer. HPV status can and does, though, form the basis for entry into (and stratification of) ongoing clinical trials which will then actually define the specialized treatments appropriate for HPV-related tumors [5]. HPV status is currently important, though, for counseling patients on their prognosis and for determining appropriate follow up and surveillance after treatment.

How to test for transcriptionally-active high risk HPV in routine clinical practice is very controversial, and an in depth examination of this issue is beyond the scope of this article. In brief, transcriptionally-active high risk HPV related oropharyngeal SCC can be established by directly testing for HPV E6/E7 mRNA [6, 7], but this testing is expensive and not currently available in clinical practice. One is then left with less specific HPV-specific tests like HPV DNA in situ hybridization (ISH) or DNA PCR. Marked p16 overexpression has been shown to be a very sensitive and easily assessed marker of active HPV in SCC and is strongly prognostic in a large amount of literature. Further, some studies have suggested that p16 overexpression, by itself, is indicative of favorable biology in oropharyngeal SCC. Given its strong prognostic power, widespread availability, and ease of use, many use it as a single test for HPV and prognostication in oropharyngeal SCC patients, with a >75 % cutoff for positivity. However, many combine p16 immunohistochemistry with HPV DNA ISH or PCR, with the p16 being the “sensitive” screening test and the HPV DNA test being the “specific” confirmatory test [8, 9]. The rates and clinical significance of tumors that show discrepant p16 and HPV specific tests are the focus of ongoing research and discussion. Practice is evolving and may ultimately be defined by the test(s) used for large, ongoing, prospective clinical trials.

Many are of the view that p16 immunohistochemistry alone is a suitable single test, at this point, for providing the appropriate information about tumors to the clinicians [10]. However, there is still a looming question of how frequently p16 positive oropharyngeal SCCs are actually HPV negative and what significance this has [8]. Some early data, particularly out of European centers, suggests this number could be as high as 10–15 % of p16 positive oropharyngeal SCC patients and that they may have a poorer prognosis [11]. Other studies have not found this degree of difference. Given the lack of quality data or consistent findings, this issue is yet to be clearly resolved. The future probably holds for a combination of p16 immunohistochemistry and an RNA (or protein)-based HPV specific test such as RNA ISH. In the meantime, the WHO should recommend at least performing p16 immunohistochemistry (with or without HPV specificity) for all patients with oropharyngeal SCC in routine clinical practice.

Suggestion #3

Recognize “nonkeratinizing SCC” as a specific pathologic subtype of HPV-related oropharyngeal SCC.

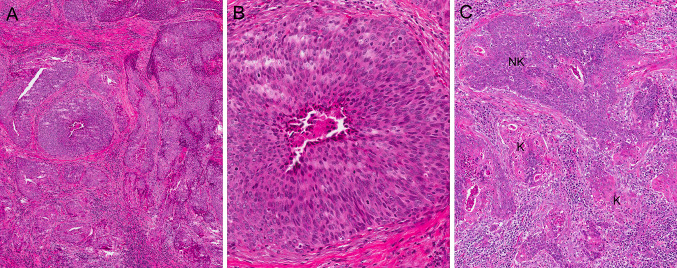

Up to 80 % of oropharyngeal SCC have a distinct morphology, described as “poorly keratinized” in the late 1990s and then termed by El-Mofty et al. [12] as “nonkeratinizing SCC” in 2003. The tumors arise from the deeply invaginated tonsillar crypt epithelium and have a “blue cell” appearance. The nests are variably sized, but usually are large, well-circumscribed, and smooth-edged with little or no stromal reaction (Fig. 1a). The cells have indistinct borders, scant to modest amounts of eosinophilic cytoplasm, and hyperchromatic, oval to spindled nuclei, which lack (or have inconspicuous) nucleoli (Fig. 1b). There is brisk mitotic activity and abundant apoptosis with frequent comedo-type necrosis. Maturing squamous differentiation is typically focal or absent (and, as initially defined, should constitute less than 10 % of the surface area of the tumor [13]). However, in some tumors, it is more prominent and extensive (Fig. 1c). When it is >10 %, such tumors have been termed “nonkeratinizing SCC with maturation [13].”

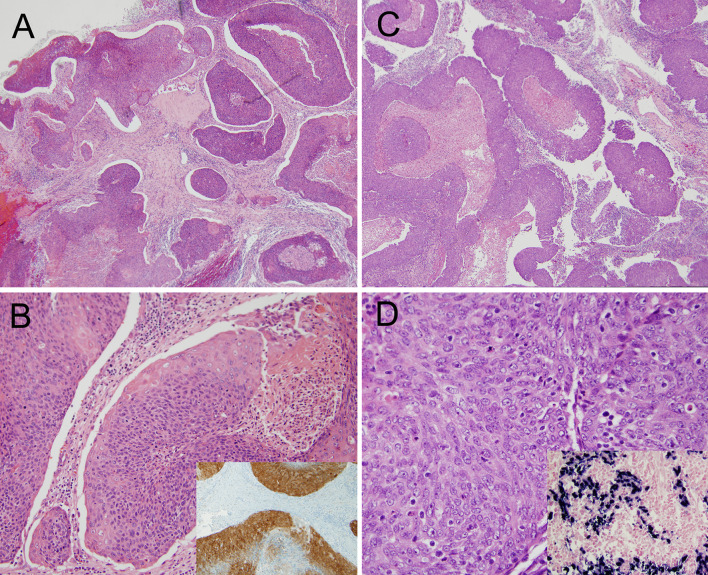

Fig. 1.

Nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma. a Low power H&E (×5 magnification); b high power H&E showing nuclear features (×20); c nonkeratinizing (NK) squamous cell carcinoma with maturation due to >10 % surface area consisting of maturing squamous differentiation (K) (×10)

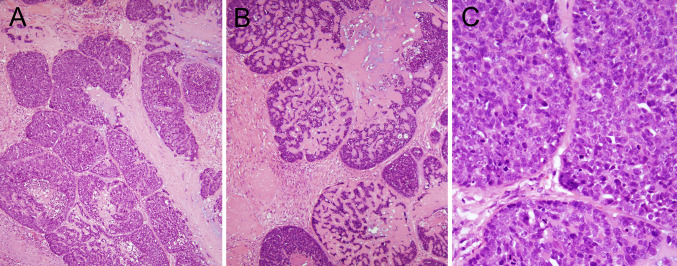

Nonkeratinizing SCC is frequently confused with basaloid SCC, a variant with very similar, but distinct, histologic features [14, 15]. While both share solid nests of highly proliferative, “basaloid” tumor cells in lobules, they differ in many other ways. In basaloid SCC, the nests frequently mold to each other in a “jigsaw” puzzle pattern like they have been pushed together, giving the sense of an overall “organization” to the tumor. The tumor cell nuclei are consistently round to oval but not spindled, and there is often stromal hyalinization and/or myxoid, basophilic areas mimicking mucin production (Fig. 2a–c). These latter stromal features are never seen in nonkeratinizing SCC. In nonkeratinizing SCC, the tumor cell nuclei are ovoid to spindled in shape, and when there is maturing squamous differentiation, it is usually patchy and present mainly at the periphery of the nests (Fig. 1b, c), whereas in basaloid SCC, if maturing differentiation is present, it is as focal and abrupt foci of keratinizing type SCC. So, by applying strict criteria for basaloid SCC, it can be appreciated as an entity distinct from oropharyngeal nonkeratinizing SCC. However, it does bear mentioning that in the oropharynx, rare tumors with mixed nonkeratinizing and basaloid features do occur. In personal experience, these are always HPV-related. Pure oropharyngeal basaloid SCC is a mixed variant in the oropharynx, with approximately 75 % of tumors harboring transcriptionally-active high risk HPV [15]. The HPV negative patients, although rare, appear to have clinically aggressive tumors [14]. The final, and most important, distinction between basaloid and nonkeratinizing SCCs is that nonkeratinizing morphology is uncommon outside of the oropharynx while basaloid SCC is often seen as primary tumors of the hypopharynx, supraglottic larynx, and oral cavity. In all of these latter sites, basaloid SCC is HPV negative and clinically very aggressive with high rates of distant metastasis [14, 15].

Fig. 2.

Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma. a Low power H&E showing jigsaw puzzle pattern (×10 magnification); b low power H&E showing extensive hyaline stromal material between the tumor cells (×10); c high power H&E view showing round, highly proliferative nuclei (×40)

Nonkeratinizing SCC in the oropharynx, on the other hand, is virtually synonymous with the presence of transcriptionally-active HPV with 98–99 % of them diffusely positive for p16 and harboring high risk HPV E6/E7 mRNA (authors’ unpublished data). Nonkeratinizing morphology is thus synonymous with more favorable outcomes [7, 12, 13]. In the new WHO classification, nonkeratinizing SCC should be recognized as a specific pathologic tumor subtype in the oropharynx that is histologically distinct from basaloid SCC.

Suggestion #4

Recommend that for p16 positive/HPV-related oropharyngeal SCCs, no grading should be performed. These tumors should be reported as “p16 positive (or HPV-related) squamous cell carcinoma (specify histologic type).”

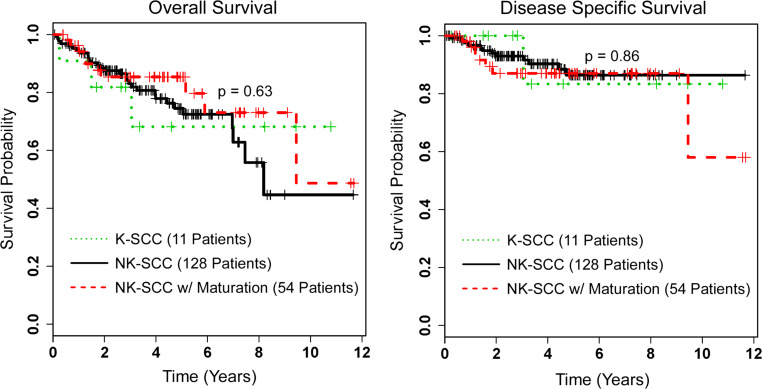

In this era of molecular diagnostics, whole genome sequencing, expression analysis, and theragnostics, the basic hematoxylin and eosin stained slide with a well-trained pathologist still holds as the best diagnostic tool. However, it is clear that there are limits to this “tried and true” examination. The data emerging in oropharyngeal SCC argues very strongly that if the tumor is driven by transcriptionally-active high risk HPV, then histologic SCC subtype is not clinically important for tumor behavior. Active HPV infection has been examined in every grade and major pattern of oropharyngeal SCC, and across all of them, patients appear to have comparably favorable prognosis. Take first, for example, degree of keratinization. Figure 3 shows Kaplan–Meier survival curves for the 193 p16 positive oropharyngeal SCC from the authors’ personal research database. When p16 positive tumors are segregated by degree of keratinization (nonkeratinizing, nonkeratinizing with maturation, and keratinizing), there is no difference in patient survival [13]. The morphology of SCC still matters for other reasons, though, such as in comparing metastases to the primary tumor, for identifying tumor in frozen sections and in margin specimens, and for aiding in the assessment of subsequent head and neck SCCs as either recurrences or new primary tumors.

Fig. 3.

Kaplan-Meier overall and disease specific survival curves for p16 positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) from the authors’ research database, stratified by degree of keratinization (NK nonkeratinizing, K keratinizing)

Grading of oropharyngeal SCC has traditionally been recommended (including by the 2005 WHO classification). It states that “the findings (for SCC) in the oral cavity and oropharynx do not differ significantly from those of the larynx and hypopharynx SCC” and that “the tumors are traditionally graded into well-, moderately-, and poorly-differentiated SCC.” [1]. This long held system for SCC, generalized across all head and neck anatomic subsites, has modest correlation with patient outcomes, but it completely breaks down for HPV-related oropharyngeal SCC. The vast majority of nonkeratinizing SCC would be classified as “poorly differentiated” tumors according to this system, but these are the patients who have excellent survival (and better than moderately or well-differentiated keratinizing SCC, most of which are HPV negative). As such, this form of “grading”, when applied to oropharyngeal SCC, conveys the complete opposite message to patients and clinicians from what it should.

Most of the other specific variants have also been examined for outcomes when arising in the oropharynx and when HPV-related (although in smaller case numbers). Two major series have shown that ~75 % of oropharyngeal basaloid SCC harbor transcriptionally-active high risk HPV [14, 15]. The survival for the HPV positive patients is comparable to large cohorts of conventional, HPV-related oropharyngeal SCC patients. Survival for the very few oropharyngeal HPV negative patients was quite poor, but the number of reported cases is so low that the data is not reliable [14, 15]. Papillary SCC has a favorable prognosis across all head and neck sites, including the oropharynx. As many as 40–45 % of papillary SCC arise here, and the prognosis is comparable to other HPV-related oropharyngeal SCC [16, 17]. Undifferentiated carcinoma, frequently with a lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma pattern akin to nasopharyngeal carcinomas, is uncommon in the oropharynx. Two small series have shown, however, that more than 90 % of these are HPV-related and that their prognosis is again comparable to other HPV-related oropharyngeal SCC [18, 19].

Finally, adenosquamous carcinoma, a rare type of SCC where the tumor has a component of well-formed glands, usually with mucin, can occur in the oropharynx. In the one small series of adenosquamous carcinomas assessing for HPV with E6/E7 RNA ISH, two of the three oropharyngeal tumors were HPV positive [20]. These patients were alive and disease free at 34 and 53 months follow up. Based on these findings, the new WHO classification should clarify that HPV-related oropharyngeal SCC should not be “graded” and that no currently defined additional morphologic features correlate with outcome. In practice, the diagnostic line may be best put simply as “p16 positive (or HPV-related) squamous cell carcinoma (specify histologic type).”

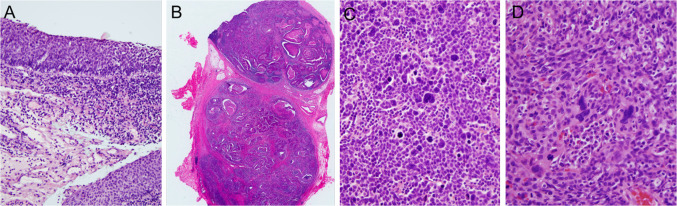

Despite the above, there are some newly described histologic features that may emerge as prognostic in HPV-related oropharyngeal SCC. Tumor cell anaplasia and/or multinucleation (Fig. 4c, d) can be seen, either focally or rarely, diffusely, in ~50–60 % of tumors. In the one series to examine their significance, the presence of these features among 149 p16 positive oropharyngeal SCC cases (57 % of which showed these features) correlated with an almost three times higher likelihood of disease recurrence and also with statistically significantly poorer disease specific survival in multivariate analysis [21].

Fig. 4.

Features of nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma. Early nodal metastasis: a biopsy showing apparent in situ carcinoma (×20 magnification); b large (>5 cm) neck lymph node metastasis from the same patient as a (×0.5). Anaplasia and multinucleation: c Another nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma that shows numerous anaplastic nuclei (×40 magnification); d nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma showing numerous multinucleated, large and bizarre tumor cells (×40)

Suggestion #5

Acknowledge that there is no morphologic distinction between tonsillar crypt in situ and invasive SCC.

The majority of invasive HPV-related SCCs arise in the tonsillar crypts and, thus, tonsillar ‘crypt dysplasia’, as a precursor to these tumors, should theoretically exist. However, a number of issues complicate this diagnosis. First, because HPV-related tonsillar SCCs are characteristically ‘nonkeratinizing’ and composed of nests with pushing borders and little stromal desmoplasia, the point at which the tumor becomes frankly invasive is often difficult to identify, especially for small tumors (Fig. 4a). Distinguishing invasive from non-invasive lesions is further complicated by the presence of deeply invaginated and folded crypt epithelium well away from the surface mucosa. Thus, neither distance from the surface epithelium nor presence of infiltrative nests with stromal reaction (both features that are heavily relied upon for the diagnosis of invasion in conventional ‘keratinizing’ SCC) can be used for detecting frank stromal invasion in HPV-related ‘nonkeratinizing’ SCC. Lastly, studies with electron microscopy have shown that the tonsillar crypt epithelium, which is reticulated and irregular, actually has a discontinuous basement membrane and contains numerous small blood vessels [22, 23]. This suggests that the tumors don’t even have to breach a basement membrane in order to metastasize. Metastasis to cervical nodes occurs early on, even in lesions that histologically appear ‘in situ’ [23]. Many patients have neck nodal metastases as large as 5 cm or more (Fig. 4b) but have clinically occult primary tumors [24]. The new WHO classification should consider all HPV-related neoplasia of the tonsillar crypts as invasive (or potentially so), discarding the classifier in situ. p16 (±HPV) testing should be performed on specimens having only foci with this appearance, and the simple term “squamous cell carcinoma” should be applied, regardless of the pattern of tonsillar crypt involvement.

Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma

Suggestion #6

Acknowledge the existence of true nasopharyngeal nonkeratinizing SCC with transcriptionally-active HPV (and lacking EBV) and how such tumors fit into the morphologic classification.

In primary nasopharyngeal carcinomas, the WHO classification generally regards tumors as being EBV-related or as lacking any association with an oncogenic virus. This appears to have changed with the epidemic of HPV-related SCC, primarily in Western and non-EBV endemic locations. Several recent studies have shown that a minority of nasopharyngeal SCC patients, specifically Caucasian North Americans and British with tumors with nonkeratinizing morphology, are EBV negative and high risk HPV-related [25–27].

The 2005 WHO classification lists nasopharyngeal carcinomas as “keratinizing” or Type 1, “nonkeratinizing, differentiated” or Type 2A, “nonkeratinizing, undifferentiated” or Type 2B, and “basaloid” or Type 3 [28]. Around the world, the nonkeratinizing types are almost implicitly EBV-related, and no specific EBV testing has been considered necessary in routine practice. Basaloid SCC of the nasopharynx is exceedingly rare, but most of these cases are EBV-related. Keratinizing SCC, on the other hand, particularly in Western countries, is almost always EBV negative.

Given this recent revelation that as many as 50 % of EBV negative nasopharyngeal carcinomas harbor transcriptionally-active high risk HPV [25], it is important for the WHO classification to at least reflect their existence, their morphologic overlap with EBV-related carcinomas, and potential significance. Both HPV-related oropharyngeal (and nasopharyngeal) SCC and EBV-related nasopharyngeal carcinoma are termed “nonkeratinizing”. EBV-related nasopharyngeal nonkeratinizing carcinomas are either undifferentiated and “lymphoepithelioma-like” with cells with syncytial arrangement and with round, vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli (WHO Type 2B) or they have a more mature appearance with more prominent cytoplasm and sharper edges to the nests (WHO Type 2A). The latter lacks maturing squamous differentiation and retains the vesicular chromatin and prominent nucleoli seen in Type 2B (Fig. 5). One recent study described the morphology of HPV-related nasopharyngeal carcinoma in detail [27]. Among 67 patients over 12 years, 11 (16.4 %) were p16 and HPV DNA ISH positive (all EBV negative). There were two keratinizing SCCs (18.2 %), seven nonkeratinizing differentiated carcinomas (63.6 %), and two nonkeratinizing undifferentiated carcinomas (18.2 %). So, although there may be subtle morphologic differences between HPV and EBV-related tumors, there is clearly significant histologic overlap between the two virus-related carcinomas. Until any consistent morphologic differences can be better appreciated and defined, one is left using the same terms of the current WHO classification for both EBV and HPV-related tumors (i.e. "nonkeratinizing"). Interestingly, although data are limited by small numbers, the HPV related tumors have not clearly been shown to have an improved prognosis relative to either EBV positive or to EBV/HPV negative carcinomas [25–27]. However, EBV-related tumors have shown improved prognosis. This may have to do with treatment regimens, but larger studies are needed to better define this.

Fig. 5.

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. a, b An HPV-related nasopharyngeal carcinoma showing ribbons of blue tumor with smooth edges and central necrosis. The inset shows positive p16 expression (a, ×4 magnification; b, ×20 magnification; b, inset ×10). c, d An EBV-related nasopharyngeal carcinoma also showing a ribbony appearance with smooth-edged nests and oval nuclei with vesicular chromatin and relatively inconspicuous nucleoli. The inset shows positivity for EBV early RNA by in situ hybridization. (c, ×4; d, ×40; d, inset ×20) (Images courtesy of Simion Chiosea M.D., University of Pittsburgh Medical Center)

Given the known clinical importance of EBV tumor association, testing of all nonkeratinizing nasopharyngeal carcinomas for EBV, regardless of any subtle morphologic differences, seems to have now become necessary. The data shows that EBV and HPV are usually exclusive of each other and that p16 immunohistochemistry is almost always negative in EBV-related nasopharyngeal carcinomas [25, 26, 29, 30]. All nonkeratinizing carcinomas should be tested for EBV (typically by ISH for EBV encoded RNA/EBER). At this time, however, p16 and/or HPV specific testing cannot be recommended for the EBV negative tumors because the significance of HPV-related nasopharyngeal SCC is still uncertain. It is just not clear what this information means for the patients. While traditionally, nonkeratinizing morphology essentially implied EBV association, it is clear that the minority of such tumors are EBV negative and HPV positive, necessitating the above approach. Future studies will hopefully more clearly define the biology and potential treatment ramifications for HPV versus EBV-related nasopharyngeal carcinomas. In summary, the WHO classification should acknowledge the existence of HPV-related nasopharyngeal carcinomas, should describe the category of “nonkeratinizing” carcinoma in more detail to include both EBV and HPV-related tumors, and should recommend EBV testing of all nonkeratinizing morphology nasopharyngeal carcinomas in routine practice (at least in Western countries).

HPV in Other Sites and Lesions

Many additional issues relating to HPV in head and neck lesions are beyond the scope of this current article. In particular, data shows high rates of transcriptionally-active HPV in SCC cervical nodal metastases, particularly cystic ones and those of unknown primary. Data about fine needle aspiration findings and on HPV testing of such specimens are emerging as well. Further, relatively large retrospective studies are defining the rates of transcriptionally-active HPV in SCCs of the sinonasal tract, oral cavity, larynx, and hypopharynx, and in dysplastic lesions, particularly those of the oral cavity. However, the clinical significance of HPV in SCCs of these sites is uncertain at this time. In benign lesions such as squamous papillomas and sinonasal Schneiderian papillomas, the rates and roles of low and high risk HPV are being better characterized. Finally, transcriptionally-active HPV is being found in unusual niches, such as in salivary gland carcinomas. All of these should be addressed in the new WHO classification to the extent of the available data.

Conclusion

Since the last WHO classification for head and neck tumors, a great deal has changed regarding our knowledge of HPV in head and neck SCC, particularly those of the oropharynx and nasopharynx. We suggest that the new version reflect many differences, particularly regarding p16/HPV testing in oropharyngeal SCC in routine practice, the morphologic features of such tumors and their clinical importance, and the rates and significance of HPV in non-oropharyngeal SCC. These suggestions should help pathologists to better identify the SCCs, characterize them, and report them clearly, and will help clinicians to counsel and treat their patients appropriately.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Samir K. El-Mofty DMD, PhD, for his longtime friendship, support of our careers in head and neck pathology, and particularly for inciting our interest in HPV-related tumors. The authors also thank Jingqin (Rosy) Luo, PhD, for the survival analysis and Kaplan–Meier survival curves shown in Fig. 3 on the patients in the authors’ research database, and thank Brian Nussenbaum MD and Wade L. Thorstad MD for their input on the clinical perspectives on treatment of HPV-related oropharyngeal SCC patients.

Contributor Information

James S. Lewis, Jr., Phone: +1-314-3627753, FAX: +1-314-7472040, Email: jlewis@path.wustl.edu

Rebecca D. Chernock, Phone: +1-314-4548854, FAX: +1-314-3628950, Email: rchernock@path.wustl.edu

References

- 1.Johnson N, Francheschi S, Ferlay J, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity and oropharynx. In: Barnes EL, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidranksy D, et al., editors. World Health Organization classification of tumours—pathology and genetics head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2005. pp. 168–175. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu X, Watson M, Wilson R, et al. Human papillomavirus-associated cancers—United States, 2004–2008. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(15):258–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):24–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, et al. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(32):4294–4301. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.4596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ang KK, Sturgis EM. Human papillomavirus as a marker of the natural history and response to therapy of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2012;22(2):128–142. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jordan RC, Lingen MW, Perez-Ordonez B, et al. Validation of methods for oropharyngeal cancer HPV status determination in US cooperative group trials. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36(7):945–954. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318253a2d1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ukpo OC, Flanagan JJ, Ma XJ, et al. High risk human papillomavirus E6/E7 mRNA detection by a novel in situ hybridization assay strongly correlates with p16 expression and patient outcomes in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35(9):1343–1350. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318220e59d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robinson M, Schache A, Sloan P, et al. HPV specific testing: a requirement for oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma patients. Head Neck Pathol. 2012;6(Suppl 1):S83–S90. doi: 10.1007/s12105-012-0370-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robinson M, Sloan P, Shaw R. Refining the diagnosis of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma using human papillomavirus testing. Oral Oncol. 2010;46(7):492–496. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis JS., Jr p16 immunohistochemistry as a standalone test for risk stratification in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2012;6(Suppl 1):75–82. doi: 10.1007/s12105-012-0369-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rietbergen MM, Brakenhoff RH, Bloemena E, et al. Human papillomavirus detection and comorbidity: critical issues in selection of patients with oropharyngeal cancer for treatment de-escalation trials. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(11):2740–5. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Mofty SK, Patil S. Human papillomavirus (HPV)-related oropharyngeal nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma: characterization of a distinct phenotype. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101(3):339–345. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chernock RD, El-Mofty SK, Thorstad WL, et al. HPV-related nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx: utility of microscopic features in predicting patient outcome. Head Neck Pathol. 2009;3(3):186–194. doi: 10.1007/s12105-009-0126-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chernock RD, Lewis JS, Jr, Zhang Q, et al. Human papillomavirus-positive basaloid squamous cell carcinomas of the upper aerodigestive tract: a distinct clinicopathologic and molecular subtype of basaloid squamous cell carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2010;41(7):1016–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Begum S, Westra WH. Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck is a mixed variant that can be further resolved by HPV status. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32(7):1044–1050. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31816380ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jo VY, Mills SE, Stoler MH, et al. Papillary squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: frequent association with human papillomavirus infection and invasive carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33(11):1720–1724. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181b6d8e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mehrad M, Carpenter DH, Chernock RD, et al. Papillary squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: clinicopathologic and molecular features with special reference to human papillomavirus. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37(9):1349–1356. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318290427d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carpenter DH, El-Mofty SK, Lewis JS., Jr Undifferentiated carcinoma of the oropharynx: a human papillomavirus-associated tumor with a favorable prognosis. Mod Pathol. 2011;24(10):1306–1312. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singhi AD, Stelow EB, Mills SE, et al. Lymphoepithelial-like carcinoma of the oropharynx: a morphologic variant of HPV-related head and neck carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34(6):800–805. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181d9ba21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Masand RP, El-Mofty SK, Ma XJ, et al. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the head and neck: relationship to human papillomavirus and review of the literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2011;5(2):108–116. doi: 10.1007/s12105-011-0245-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewis JS, Jr, Scantlebury JB, Luo J, et al. Tumor cell anaplasia and multinucleation are predictors of disease recurrence in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma, including among just the human papillomavirus-related cancers. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36(7):1036–1046. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182583678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perry ME. The specialised structure of crypt epithelium in the human palatine tonsil and its functional significance. J Anat. 1994;185(Pt 1):111–127. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Westra WH. The morphologic profile of HPV-related head and neck squamous carcinoma: implications for diagnosis, prognosis, and clinical management. Head Neck Pathol. 2012;6(Suppl 1):S48–S54. doi: 10.1007/s12105-012-0371-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park GC, Lee M, Roh JL, et al. Human papillomavirus and p16 detection in cervical lymph node metastases from an unknown primary tumor. Oral Oncol. 2012;48(12):1250–1256. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dogan S, Hedberg ML, Ferris RL et al. Human papillomavirus and Epstein–Barr virus in nasopharyngeal carcinoma in a low-incidence population. Head Neck. 2013. doi:10.1002/hed.23318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Maxwell JH, Kumar B, Feng FY, et al. HPV-positive/p16-positive/EBV-negative nasopharyngeal carcinoma in white North Americans. Head Neck. 2010;32(5):562–567. doi: 10.1002/hed.21216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robinson M, Suh YE, Paleri V, et al. Oncogenic human papillomavirus-associated nasopharyngeal carcinoma: an observational study of correlation with ethnicity, histological subtype and outcome in a UK population. Infect Agent Cancer. 2013;8(1):30. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-8-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan JKC, Bray F, McCarron P, et al. Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. In: Barnes EL, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidranksy D, et al., editors. World Health Organization classification of tumours—pathology and genetics of head and neck tumors. Lyon: IARC Press; 2005. pp. 85–97. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lo EJ, Bell D, Woo J, et al. Human papillomavirus and WHO type I nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Laryngoscope. 2011;120(Suppl 4):S185. doi: 10.1002/lary.21649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Punwaney R, Brandwein MS, Zhang DY, et al. Human papillomavirus may be common within nasopharyngeal carcinoma of Caucasian Americans: investigation of Epstein–Barr virus and human papillomavirus in eastern and western nasopharyngeal carcinoma using ligation-dependent polymerase chain reaction. Head Neck. 1999;21(1):21–29. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199901)21:1<21::AID-HED3>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]