Abstract

We aimed to explore perceptions, attitudes and practices toward research among medical students. A self-administered questionnaire was distributed among senior medical students at the King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Hundred and seventy two students participated in the study, with 97 males (65.5%). The majority of the students agreed that research is important in the medical field (97.1%, 167/172). A total of 67.4% (116/172) believed that conducting research should be mandatory for all medical students. During medical school, 55.3% (88/159) participated in research.

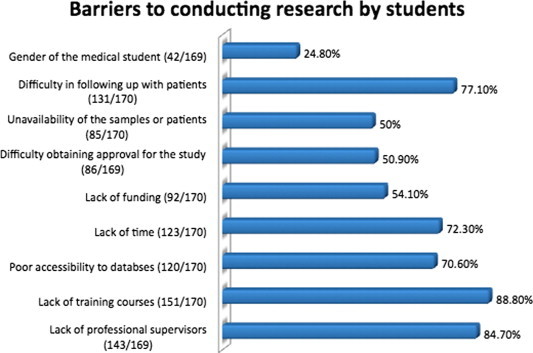

The obstacles that prevented the students from conducting research included lack of professional supervisors (84.7%, 143/169), lack of training courses (88.8%, 151/170), lack of time (72.3%, 123/172) and lack of funding (54.1%, 92/170).

Although the majority of students believe that research is important in the medical field, only around half of the students participated in research during medical school.

Keywords: Medical students, Research, Teaching, Training, Attitudes, Obstacles

1. Introduction

Health research training has been recognized as an important component of medical education because the rapid expansion and progress in biomedical research is expected to transform medical care (Scaria, 2004). Physician-investigators play key roles in translating progress in basic science into clinical practice by defining physiological and pathological implications at the molecular level, guiding basic science research into clinically relevant directions and designing and evaluating new therapies based on basic scientific discoveries (Wyngaarden, 1981; Rosenberg, 1999; Zemlo et al., 2000). Studies have shown that research experience during medical school is strongly associated with postgraduate research initiatives (Segal et al., 1990; Reinders et al., 2005) and future career achievements in academic medicine (Brancati et al., 1992). The development of research capacity is imperative at the individual and institutional levels to attain a sustainable improvement in health research (Sadana et al., 2004). To fill the void of physician-scientists in developing countries, initiatives are being taken to motivate medical students to undertake careers in research (Bickel and Morgan, 1980). Various strategies are being employed for this purpose, which include mandatory and elective research assignments, student sections in indexed journals, organization of student scientific conferences, molding of medical curriculum to integrate capacity building for research and holding of workshops on different aspects of conducting research (Khan and Khawaja, 2007).

There has been a documented decline in the number of physician-scientists in the medical practice (Solomon et al., 2003). Postulated explanations for the decline include less financial incentive, family, practice philosophy and inadequate exposure to research before career paths are determined (Lloyd et al., 2004; Neilson, 2003).

However, given the demands and competing interests of formulating an undergraduate medical curriculum and the attitudes of other learners during medical training, it appears pivotal to experience research during medical school (Siemens et al., 2010). The objective of our study was to explore perceptions, attitudes and practices toward research among senior medical students.

2. Methods

This was a cross-sectional survey conducted on all male and female fourth and fifth year medical students at the King Saud University (KSU) Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, from March to June 2011. The medical program at KSU is a 5-year curriculum, where the fourth and fifth years are considered senior years. The education system in most Saudi universities, including KSU, permits the students to enter medical school immediately after high school.

2.1. Data collection

The survey questions were collected from previous studies about the attitudes of medical students toward research. The questions were modified to develop a complete version to fit our culture. The survey was pilot tested on 50 students before distribution to estimate the time required to complete the questionnaire and determine the comprehension of the questions by the participants so that it could be refined accordingly. Pilot questionnaires were excluded from the final analysis. The final self-administered questionnaire consisted of 24 questions, which required approximately 5 min to answer. The local ethics committee approved this study.

2.2. Questionnaire

An information sheet was attached to each questionnaire with a short description of the aim of the study and instructions on how to complete the questionnaire.

The questionnaire was subdivided into categories in which the first part included the perceptions of medical students of the importance of research and its impact on their career. The second part highlighted the important obstacles to conducting research. The following section contained questions about practicing research and experiences in this domain. Finally, socio-demographic information of the participating students including age, gender, income, medical year and residency program of interest was collected.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Version 16 of the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) program was used for statistical analysis. Numerical variables were reported as a mean ± standard deviation. A Chi-square test was used for assessment of the association between different categorical variables. The statistical significance was based on a p-value <0.05.

3. Results

One hundred and seventy-two students participated in the study. The individuals sampled included 97 males (65.5%). The mean age was 23 years (SD = 1.17, range = 21–32). Fifty-two percent were fourth year students. Regarding interest in residency programs, 41.2% (61/148) were interested in a medical specialty residency, 49.3% (73/148) were interested in a surgical specialty residency, and the rest were either undecided or interested in a basic science residency program. The program of interest to the student was regarded as competitive by 74.2% (109/147) of participants, while 25.9% (38/147) stated it that it was not competitive.

3.1. Perceptions about research

The majority of the students agreed that research is important in the medical field (97.1%, 167/172). The majority also agreed that conducting research during medical school is important (87.7%, 151/172). Many students (67.4%, 116/172) believed that conducting research should be mandatory for all medical students, and 91.9% (158/172) believed that research methodology should be a part of the medical school curriculum. Forty-three percent (74/172) agreed that their research experience should be an important criterion for acceptance in residency, while 13.4% (23/172) were neutral about this issue and 1.8% (3/172) disagreed.

The barriers to conducting research stated by the participating medical students varied widely and included lack of professional supervisors (84.7%, 143/169), lack of training courses (88.8%, 151/170), lack of time (72.3%, 123/172) and lack of funding (54.1%, 92/170) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Barriers to conducting research among the 172 students participating in the study.

3.2. Attitudes toward research

The motives of the students behind conducting research during medical school included the following: research being mandatory in the curriculum (78.5%, 124/158), facilitating acceptance to a residency program (82.9%, 131/158), a positive achievement on their resume (86.7%, 137/158), fulfilling research interests (74.1%, 117/158), improving research skills (93%, 147/158) and attaining a research publication (79.7%, 126/159). The majority of the students (82.3%, 130/158) believed that conducting research reinforces a teamwork spirit.

3.3. Research practice during medical school

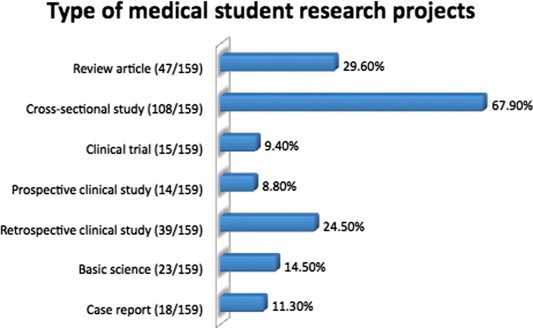

Of the participating students, 55.3% (88/159) participated in research during medical school, while 44.7% (71/159) did not. A chi-square test to associate conducting research and the various socio-demographic data did not show any significance (data not shown). Students who participated in research during medical school contributed to the process in the following ways: the concept of research (80.8%, 126/156), literature review (83.1%, 128/154), writing of the proposal (51.9%, 80/154), real execution (84.6% 132/156), data entry (60%, 93/155), data analysis (52.6%, 82/156) and manuscript writing (50.3%, 78/155). The types of research projects that students participated in included case reports (11.3%, 18/159), basic science projects (14.5%, 23/159), retrospective clinical studies (24.5%, 39/159), prospective clinical studies (8.8%, 14/159), clinical trials (9.4%, 15/159), cross-sectional studies (67.9%, 108/159) and review articles (29.6%, 47/159) (Fig. 2). The mean number of hours students spent on their research projects every week was 3.3 ± 5.2. The mean number of poster presentations students utilized to present their research was 0.4 ± 0.8, but the mean number of oral presentations was 1.0 ± 1.5, and the mean number of publications was 0.4 ± 0.91.

Figure 2.

Type of research projects conducted by the 172 students included in the study.

4. Discussion

Our study focused on the perceptions, attitudes and practices of senior medical students toward research. This topic is extremely important because understanding the perceptions and attitudes of students toward this issue can lead to improvement of research practices among future physicians.

The negative attitudes of medical students toward research have been found to serve as an obstacle to learning associated with poor performance in research (Siemens et al., 2010). Most of the medical students are not aware of why research is crucial to health care. Lack of student conferences and research workshops on how to write and organize research papers is among the reasons for such negative attitudes (Siemens et al., 2010).The encouragement of those young researchers is not sufficient. Lack of time was seen as a significant barrier to pursuing research during medical school due to the busy curriculum (Siemens et al., 2010). This factor results in a decreased number of medical students interested in participating in research.

Our results are comparable to the results of a study performed in Canada. This study found that although the majority of medical students felt that participation in research activities was likely beneficial to their education, only 44% felt that research will play a significant role in their future career, and only 38% agreed that more time should be set aside in medical school to facilitate more research experience (Siemens et al., 2010). In our study, the majority believed that research was important in the medical field (97.1%, 167/172) and a boosting factor for their careers, but only 55.3% (88/159) participated in research during medical school.

Even if research experience as a student does not lead to a career in academic medicine, the experience can help improve a student’s skills in searching and critically appraising the medical literature and independent learning (Houlden et al., 2004; Frishman, 2001). Such exposure to research as a student can also help identify future careers, establish important contacts and secure better residency positions. Given the many benefits of doing a research project as a student, not surprisingly, 97% of students included in an American study considered research a useful alternative to electives, (Frishman, 2001) while in our study, 67.4% (116/172) agreed that research should be mandatory for all medical students.

In the Canadian study, 43% stated that they had no significant involvement in research projects during medical school, and 24% had no interest in any research endeavors (Siemens et al., 2010). However, in Germany, medical students authored 28% of the publications of one institution, including first authorship in 7.8% of papers (Cursiefen and Altunbas, 1998). Research is not considered a part of the medical curriculum in many developing countries. In a study from India, for example, 91% of interns reported no research experience in medical school (Chaturvedi and Aggarwal, 2001). Thus, students in India are rarely exposed to research at the stage of their academic development when such exposure could encourage further research (Aslam et al., 2005). In Saudi Arabia, it seems that our results are similar to the Canadian results, where we are in the middle between Germany and India. About half of the students have been involved with research and participated in writing manuscripts for publication.

In the Canadian study, 43% of respondents agreed that the main reason to participate in research during medical school was to facilitate acceptance into a residency of choice (Siemens et al., 2010). In our study, the motives behind conducting research during medical school included the following: research being mandatory in the curriculum (78.5%, 124/158), facilitating acceptance into a residency program (82.9%, 131/158), a positive achievement on their resume (86.7%, 137/158), fulfilling research interests (74.1%, 117/158), improving research skills (93%, 147/158) and to attain a research publication (79.7%, 126/159).

In the Canadian study, lack of time was a significant barrier to pursuing research during medical school as only 31% of all respondents felt there was adequate allotted time for research endeavors (Siemens et al., 2010). Furthermore, only 15% of respondents felt that there was sufficient training in research methodology in medical school, and only 25% agreed that there was adequate training in the critical appraisal of scientific literature. Another perceived barrier to participation in research was the difficulty in attaining a research supervisor; only 44% of respondents agreed that it was relatively easy to find a research mentor (Siemens et al., 2010). The barriers to participating in research in our study included lack of professional supervisors (84.7%, 143/169), lack of training courses (88.8%, 151/170), lack of time (72.3%, 123/172) and lack of funding (54.1%, 92/170).

We believe that finding ways to overcome the obstacles students face is needed to motivate students to participate in research. Medical schools should update their curricula to include teaching of research methodology, to allocate specific time for research and to require research experience for all medical students. Medical schools should also assign supervisors for student research. Faculty should encourage and motivate students to participate in research.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate the perceptions, practices, obstacles and attitudes toward research among medical students in the Middle East. We not only addressed a previously neglected issue in our region but also attempted to comprehensively assess this issue to find ways to overcome the obstacles faced by students. These efforts could lead to an increased involvement of medical students in research.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. D. Robert Siemens for providing us with a copy of the survey used in his research.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Aslam F., Shakir M., Qayyum M.A. Why medical students are crucial to the future of research in South Asia. PLoS Med. 2005;2(11):e322. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel J., Morgan T.E. Research opportunities for medical students: an approach to the physician-investigator shortage. J. Med. Educ. 1980;55(7):567–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brancati F.L., Mead L.A., Levine D.M., Martin D., Margolis S., Klag M.J. Early predictors of career achievement in academic medicine. JAMA. 1992;267(10):1372–1376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi S., Aggarwal O.P. Training interns in population-based research: learners’ feedback from 13 consecutive batches from a medical school in India. Med. Educ. 2001;35(6):585–589. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cursiefen C., Altunbas A. Contribution of medical student research to the Medline-indexed publications of a German medical faculty. Med. Educ. 1998;32(4):439–440. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1998.00255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frishman W.H. Student research projects and theses: should they be a requirement for medical school graduation? Heart Dis. 2001;3(3):140–144. doi: 10.1097/00132580-200105000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houlden R.L., Raja J.B., Collier C.P., Clark A.F., Waugh J.M. Medical students’ perceptions of an undergraduate research elective. Med. Teach. 2004;26(7):659–661. doi: 10.1080/01421590400019542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan H., Khawaja M.R. Impact of a workshop on the knowledge and attitudes of medical students regarding health research. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2007;17(1):59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd T., Phillips B.R., Aber R.C. Factors that influence doctors’ participation in clinical research. Med. Educ. 2004;38(8):848–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neilson E.G. The role of medical school admissions committees in the decline of physician-scientists. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;111(6):765–767. doi: 10.1172/JCI18116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinders J.J., Kropmans T.J., Cohen-Schotanus J. Extracurricular research experience of medical students and their scientific output after graduation. Med. Educ. 2005;39(2):237. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.02078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg L.E. Physician-scientist endangered and essential. Science. 1999;283(5400):331–332. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5400.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadana R., D’Souza C., Hyder A.A., Chowdhury A.M. Importance of health research in South Asia. BMJ. 2004;328(7443):826–830. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7443.826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaria V. Whisking research into medical curriculum: the need to integrate research in undergraduate medical education to meet the future challenges. Calicut Med. J. 2004;2(1):e1. [Google Scholar]

- Segal S., Lloyd T., Houts P.S., Stillman P.L., Jungas R.L., Greer R.B., 3rd. The association between students’ research involvement in medical school and their postgraduate medical activities. Acad. Med. 1990;65(8):530–533. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199008000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemens D.R., Punnen S., Wong J., Kanji N. A survey on the attitudes towards research in medical school. BMC Med. Educ. 2010;10:4. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-10-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon S.S., Tom S.C., Pichert J., Wasserman D., Powers A.C. Impact of medical student research in the development of physician-scientists. J. Invest. Med. 2003;51(3):149–156. doi: 10.1136/jim-51-03-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyngaarden J.B. The clinical investigator as an endangered species. Bull. NY Acad. Med. 1981;57(6):415–426. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemlo T.R., Garrison H.H., Partridge N.C., Ley T.J. The physician-scientist: career issues and challenges at the year 2000. FASEB J. 2000;14(2):221–230. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.14.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]