Abstract

Interventions by the pharmacists have always been considered as a valuable input by the health care community in the patient care process by reducing the medication errors, rationalizing the therapy and reducing the cost of therapy. The primary objective of this study was to determine the number and types of medication errors intervened by the dispensing pharmacists at OPD pharmacy in the Khoula Hospital during 2009 retrospectively. The interventions filed by the pharmacists and assistant pharmacists in OPD pharmacy were collected. Then they were categorized and analyzed after a detailed review. The results show that 72.3% of the interventions were minor of which 40.5% were about change medication order. Comparatively more numbers of prescriptions were intervened in female patients than male patients. 98.2% of the interventions were accepted by the prescribers reflecting the awareness of the doctors about the importance of the pharmacy practice. In this study only 688 interventions were due to prescribing errors of which 40.5% interventions were done in changing the medication order of clarifying the medicine. 14.9% of the interventions were related to administrative issues, 8.7% of the interventions were related to selection of medications as well as errors due to ignorance of history of patients. 8.2% of the interventions were to address the overdose of medications. Moderately significant interventions were observed in 19.4% and 7.5% of them were having the impact on major medication errors. Pharmacists have intervened 20.8% of the prescriptions to prevent complications, 25.1% were to rationalize the treatment, 7.9% of them were to improve compliance. Based on the results we conclude that the role of pharmacist in improving the health care system is vital. We recommend more number of such research based studies to bring awareness among health care professionals, provide solution to the prescription and dispensing problems, as it can also improve the documentation system, emphasize the importance of it, reduce prescribing errors, and update the knowledge of pharmacists and other health care professionals.

Keywords: Pharmacists intervention, Pharmaceutical care, Out-patient pharmacy, Prescriptions

1. Introduction

The role of pharmacist has been diversified from dispensing medications to patient care, patient counselor, health care educator, and community service to clinical practice. The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) has recommended that all prescriptions must be reviewed by pharmacists before dispensing and stressed that the outcomes should be documented as a result of direct patient care by the pharmacy (Liya et al., 2003). Any error in ordering, transcribing, dispensing, administering and monitoring in the process of medication is called medication error (Kim and Schepers, 2003). Intervention by the pharmacist is warranted to detect these medication therapy problems, after which, solutions for these problems can be invented or drug therapy optimized for each patient. These interventions have developed by time and their forms, vary from the simplest handwritten form to the computerized databases (Kim and Schepers, 2003; US Food and Drug Administration, 2011). Furthermore, many of these problems can be prevented by educating health care providers about them (Bieszk et al., 2002).

Health care professionals expecting the pharmacists and pharmacies to have diversified responsibilities include monitoring medication for people with acute and chronic disease, operating repeat prescription services, reviewing medication for long-term users, prescribing under protocols, advising on the management of common conditions and participating in local and national health promotion or disease prevention activities (Felicity, 2009). Documentation of their interventions is important for justifying pharmacists’ services to the patient, healthcare administrators and providers, patient care takers, to strengthen the profession and the society in total (Felicity, 2009). These clinical interventions of pharmacists not only have a positive impact on patient care but also decreased cost. Recently, electronic systems and commercially available products and software packages are used for documentation of clinical pharmacy interventions more efficiently than paper systems. However, most out-patient pharmacies do not have a central database for capturing interventions at experiential locations (Majumdar and Soumerai, 2003; Fox, 2011).

A study done in USA, 2001 showed that the majority of the prescriptions (76%) did not reach the patient, but had the potential to cause morbidity or mortality significantly, 22% were duplicate orders, 19% were wrong doses, 16% were wrong frequencies and other interventions contracted 19% (Kim and Schepers, 2003). An Australian study carried out in a teaching hospital indicates that 41.7% of the initial total interventions were excluded as they were considered as minor to moderate in significance that would be likely to improve the therapeutic outcome, without having a major impact upon the patient’s health. The most common category of interventions was high dose errors, that constitute for 43.6% of the severe interventions (Alderman and Farmer, 2001). It has been proven that the clinical interventions improve adherence to national clinical practice guidelines and optimizing the pharmacy benefit for elderly. Interventions by the pharmacist in a psychiatric hospital showed that 64.5% of the interventions were of no significance, 24.2% of minimal clinical significance, 11.4% of clinical significance, and none was potentially life-threatening (Bosma, 2007; Bieszk et al., 2002).

The documentation of interventions by the pharmacist at the out-patient department of the Khoula Hospital has been started from 2009 and during this time many interventions have been made by the working pharmacists and assistant pharmacists. However, its impact on regular medical practice, patient safety and improvement in patient care is not known. In OPD, they still use the handwritten interventions, where pharmacists have to send the prescription back to the doctor with their comments in it, to clarify any unclear issues about the case or medications. Sometimes, interventions are done by calling the doctor. Importance of many pharmaceutical interventions by the pharmacist in an OPD pharmacy is unnoticed or unreported due to the lack of documentation. It was hypothesized that, these interventions by the pharmacists were more significant in clinical practice and patient care in reducing drug associated problems. Furthermore, we wanted to test if there is any association between pharmaceutical intervention, on the one hand, and prevention of complications, morbidity and improvement of cost and compliance, on the other hand.

The main aim of the study was to know the prevalence of different types of intervened medication errors, types of interventions, and action taken at OPD pharmacy in Khoula Hospital Muscat, Oman during 2009.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study design

The present study is a systematic retrospective study carried out by collecting the intervened prescriptions available at the Out-patient pharmacy of Khoula Hospital Muscat. It was conducted after an official permission obtained from the Director General of Khoula Hospital. All prescriptions of 2009 intervened by the pharmacist and filled in an OPD pharmacy were collected and included in the study. Utmost care was taken to include only those prescriptions which were intervened by the pharmacists and documented well by their comment on the prescription. The work experience of the staff, that used to do the interventions independently, varies from as low as 2 years to more than 10 years. All prescriptions that were illegible or the intervention done by the pharmacist was not clearly written, and any prescription that did not meet the inclusion criteria was excluded. Confidentiality of the information is maintained by not disclosing patient name, patient ID, name of the doctor who prescribed, and name of the pharmacist who did the interventions. British National Formulary, Oman National Formulary and Dipiro’s Pharmacotherapy are used as standards to substantiate correct interventions by the pharmacists.

2.2. Categorization of interventions

Pharmacists’ intervention and comments written on the prescriptions were used to revise each error and classify it into the following categories: (1) Change medication order/Clarify medicine; (2) Medication selection recommendation; (3) Prescribing medication without indication; (4) Therapeutic duplication; (5) Overdose; (6) Sub-therapeutic dose or duration; (7) ADRs/drug–drug interaction; (8) Addition of another medicine; (9) Transcription error; (10) Administrative issues; (11) Not reviewing past medical history of pts.

2.3. Severity of consequences

Based on the seriousness of consequences caused by the intervened medication errors the severity was categorized as minor those that do not harm the patient and need monitoring; moderate those that can cause a temporary harm if used; major were those that can harm temporarily may be leading to hospitalization, resulting in permanent harm, near-death or death and others were those related to issues of administration and pharmacoeconomics.

2.4. Reasons of interventions

The reasons for interventions written on the prescriptions were read and categorized as to prevent complications and morbidity, to rationalize the treatment, improve compliance and cost and others.

2.5. Analysis of data

In a monthlywise statistic report, the data from the interventions was recorded and then entered into an SPSS. After that, the data was reviewed and evaluated. In the final step, data was analyzed and categorized. Based on pharmacists’ intervention, an effort was made to identify the most common intervention, and other factors. The data is presented in percent and numbers.

3. Results

The total number of prescriptions dispensed from the OPD pharmacy at Khoula Hospital during the year 2009 was 30,563. The number of interventions collected by the pharmacy in the same year was 692 interventions which are about 2.3% of the total dispensed. 688 interventions out of 692 were prescribing errors. The results are described in the following charts and tables:

3.1. Demography of intervened prescriptions

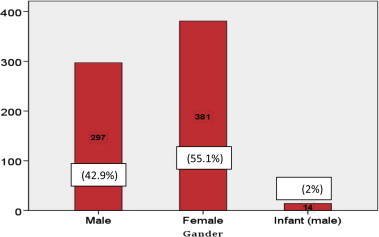

As shown in Fig. 1, 297 of the intervened prescriptions were of male patients constituting 42.9% of the total and 381 were of the female patients constituting 55.1% of the total intervened prescriptions. 2% of the prescriptions were of infants having 14 in numbers.

Figure 1.

Demography of intervened prescriptions.

3.2. Types of interventions at OPD pharmacy

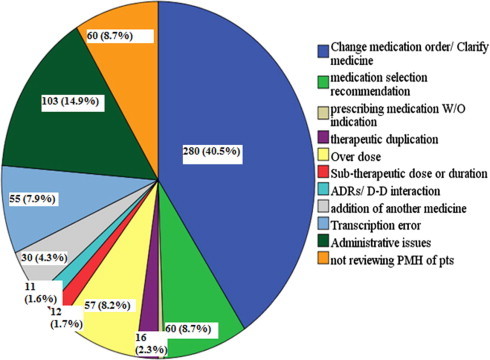

In this study only 688 interventions were due to prescribing errors of which 40.5% interventions were done in changing the medication order of clarifying the medicine. 14.9% of the interventions were related to administrative issues, 8.7% of the interventions were related to selection of medications as well as errors due to ignorance of history of patients. 8.2% of the interventions were to address the overdose of medications. Transcription errors were intervened in 7.9% of the prescriptions (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Types of interventions at OPD pharmacy.

3.3. Intervened medication errors of other category

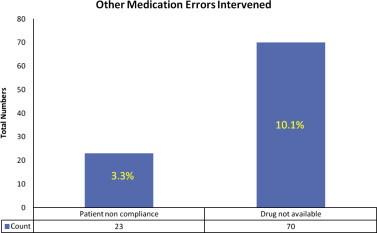

Fig. 3 shows that there were some interventions done by the pharmacist due to some other reasons. 23 of them were related to patient non-compliance causing 3.3% and 10.1% of the interventions were related to availability of the drug.

Figure 3.

Intervened medication errors of others category.

3.4. Percent of interventions accepted/rejected by prescribers

As shown in Table 1, 98.2% of the interventions made by the pharmacists were accepted by the prescribers and 1.7% of them were not accepted citing the medical conditions and other circumstances.

Table 1.

Percent of interventions accepted/rejected by prescribers.

| Value | Count | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Accepted | 680 | 98.2 |

| 2 | Rejected | 12 | 1.7 |

3.5. Severity of intervened medication errors

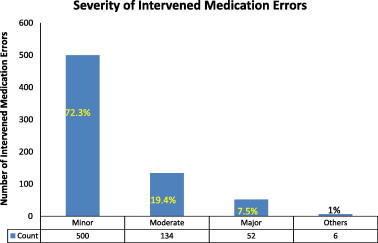

As depicted in Fig. 4, 72.3% of the interventions were carried out mainly to address the minor significant medication errors. Moderately significant interventions were observed in 19.4% and 7.5% of them were having the impact on major medication errors.

Figure 4.

Severity of intervened medication errors.

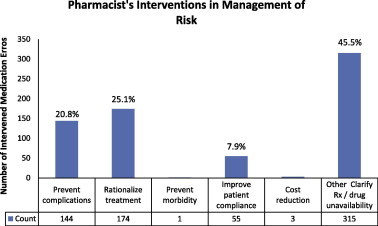

3.6. Pharmacists’ interventions for risk management

Pharmacists have intervened 20.8% of the prescriptions to prevent complications, 25.1% were to rationalize the treatment, 7.9% of them were to improve compliance, three of them were to reduce the cost, one was to prevent morbidity and major contribution was to clarify the medication or non-availability of the medication (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Pharmacist’s interventions for risk management.

4. Discussion

Most of the clinical interventions recorded by the dispensing pharmacists in an OPD pharmacy showed that the majority of the prescriptions (72.3%) were categorized as minorly significant having no potential to cause morbidity or mortality significantly whereas, 19.4% interventions were moderately significant and 7.5% were majorly significant. These results are similar to the study carried out in 2001 in USA at a dispensing pharmacy (Liya et al., 2003). However, these results support the outcome of study conducted in an Australian teaching hospital where they found 41.7% of interventions were mild–moderate (Alderman and Farmer, 2001). Also, the study that was done in UK in 2004 showed closer results (Stubbs et al., 2004). A Danish prospective study has shown 32% interventions were clinical and 68% administrative by nature. In the study period, a total of 55,522 prescriptions were filled out together with 3,069 dose-dispensing packages, giving a rate of 10.2 (9.4–11.1) interventions per 1000 prescriptions (Anton et al., 2011). However, results of our study contradicts the inpatient interventions by clinical pharmacists at Sultan Qaboos University Hospital, Muscat where 33% of interventions were recorded to be majorly significant, 39% of interventions were undertaken to improve efficacy and 30% of interventions were to reduce the toxicity (Al Zadjali, 2007).

It is hard to believe that 40.5% of interventions were to change medication order or to clarify the reason for prescribing that medication. It is a concern in pharmacy practice and needs to be addressed. 14.9% administrative issues, 8.7% selection of medication and need of reviewing past medical history of patients each, 8.2% overdose, 7.9% transcription errors and other interventions contracted 11%. The total documented interventions were 2.3% of the total dispensed prescriptions in a year. In contrast, in a US study 92% of the interventions were to change medication order, 11% need to review past medical history, 73% medication selection recommendation, and other interventions were 5%. A study in UK showed that 76.3% of the interventions were about errors in the prescription writing (administrative issues), including transcribing medication order, omission of prescriber’s signature, incomplete prescription, etc. (Liya et al., 2003; Kim and Schepers, 2003; Alderman and Farmer, 2001. Stubbs et al., 2004). A study carried out in an ambulatory neurologic clinic notified 29% to discontinue a medication, 24% to add a medication, 23% to change a dose, 20% for therapeutic substitutions, and 4% for therapeutic monitoring (Swain and Lindy, 2012).

In some cases pharmacists have intervened to reduce the cost of medications to improve the patient compliance and affordability. A similar, kind of effort was also observed in a recommendation passed by Capitated senior drug benefit plan 2002. One of the studies in USA, concluded that the cost saving interventions with cost avoidance potentials were not well documented by most pharmacies (Kim and Schepers, 2003; Bieszk et al., 2002).

Interventions in prescriptions obtained by females were 55.1% when compared to males of 42.9% this can be explained due to the fact that female patients are more interested to know about drugs, their indications and any drug therapy problems from pharmacists. Similar results were viewed in a Dutch study where male’s interventions constitute 41%, but the opposite was in Australia where a research revealed 78.9% male and 21.1% female interventions (Alderman and Farmer, 2001; Bosma, 2007).

One of the most important things noticed by the dispensing pharmacists was problem with medication compliance. In this study it was observed that 3.3% of interventions were to improve the compliance of patients and 10.1% of interventions due to non-availability of medications. These results indicate that the dispensing pharmacists at OPD pharmacy are interacting with the patients and counseling them to improve medication compliance and also making them to understand the importance of compliance.

The pharmacists’ intervention improved the balance between necessity and concern beliefs about medication, and efficiently resolved practical barriers in medication taking thereby improving medication adherence in non-adherent RA patients (Zwikker et al., 2012).

One of the recent prospective study carried out to know the impact of clinical pharmacists’ interventions concluded that the impact of clinical pharmacist providing patient counseling had a positive impact on medication adherence and quality of life (Ramanath, 2012; US Food and Drug Administration, 2011).

The best thing found in the study is that the interventions undertaken by the pharmacists are well received and accepted (98.2%) by the working physicians in the hospital symbolizing that the health care system in the Khoula Hospital is patient centered. These results are better than the results of a Dutch research, where 82% of the interventions were accepted by the prescribers (Bosma, 2007) In one of the prospective study lasting 4 years, the frequency of Pharmacists’ interventions remained constant throughout the study period, with 47% accepted, 19% refused and 34% not assessable. The most frequent DRP concerned improper administration mode (26%), drug interactions (21%) and overdosage (20%). These resulted in changing in the method of administration (25%), dose adjustment (24%) and drug discontinuation (23%) with 307 drugs being concerned by at least one pharmacists’ intervention. Paracetamol was involved in 26% of overdosage pharmacists’ interventions. Erythromycin as a prokinetic agent, presented a recurrent risk of potentially severe drug–drug interactions especially with other QT interval-prolonging drugs. Following an educational seminar targeting this problem, the rate of acceptation of pharmacists’ intervention concerning this drug related problem increased (Charpiat et al., 2012).

How important these interventions can be realized from the data obtained in the study; 25.1% of interventions were to rationalize the treatments, 20.8% of them were to prevent complications, 7.9% of them were to improve patient compliance and 45.5% of them were on clarification and drug non-availability. In summary, we can say that 46% of interventions have prevented morbidity, complications and rationalized the therapy (Stubbs et al., 2004; Bosma, 2007). In one of the recently conducted study it has been noted that the most commonly identified drug-related problems were drug interactions (37%), overdosage (28%), non-conformity to guidelines or contra-indications (23%), underdosage (10%) and improper administration (2%). The clinical pharmacist’s interventions consisted of dose adjustment (38%), addition of drugs (31%), changes in drugs (29%) and optimization of administration (2%) (Al-Hajje et al., 2012).

The Directors of Hospital Pharmacy recommended documentation of pharmacists’ interventions which can help in enhancing the communication with other health care providers, justifying workload, and identifying opportunities for focused drug use review. Also, they pointed out that these interventions reflect the wide range of services provided by pharmacy. A study titled: Pharmacists’ intervention documentation in US health care system, showed that 61% of the pharmacy directors reported dissatisfaction with their documentation system, 14% were neutral, and 25% were satisfied (Kim and Schepers, 2003).

Based on the outcome of the present study and recommendations of previous studies we recommend to digitize the pharmacists’ intervention documentation to allow maximum flexibility in data capture, analysis and reporting. This would assist in providing customizable exporting/reporting features focus on the sharing of intervention data within and outside the pharmacy and health care services (Fox, 2011; King et al., 2007). The newer electronic systems using handheld technology or web-based programs (Fox, 2011; MacKinnon, 2003), and other commercial intervention documentation tools like Qunatifi support easy documentation of pharmacists’ interventions in the health care setting. As shown these systems would provide consistency and efficiency and a broad application to an entire health care service; however, the outpatient interventions required substantial development (Fox, 2011; MacKinnon, 2002). After implementation, we recommend continued evaluation of the system and how it is used, as well as longitudinal training for pharmacists working not only in outpatient but also in other departments of the hospital (Fox, 2011).

We also recommend further research to identify environmental, organizational, financial, socio-cultural, personal, family or other contextual factors that may be pre-requisites for the success of any interventions, and how the quality of outpatient pharmacy services can be enhanced within a wider reform framework.

Acknowledgements

We take this opportunity to thank all OPD pharmacy staff at Khoula Hospital specially Mr. Zakariya Al Zadjali, Ms. Wadha Al Kalbani and Ms. Sumaiya Al Zadjali for their assistance in data collection and analysis. We would like to thank Dr. Jayasekhar P, Head, Department of Pharmacy, Oman Medical College, Bausher Campus Muscat and Dr. Diana Beattie, Dean, Pre-medicine and Pharmacy Programme, Oman Medical College, Bausher Campus, Muscat for their constant support and providing required facilities to successfully carry out the study. We also acknowledge the assistance of those who have contributed with their time, knowledge, skills, analysis and support without which the research would not have been completed.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Alderman Christopher P., Farmer Christopher. A brief analysis of clinical pharmacy interventions undertaken in an Australian teaching hospital. ISMP Medication Safety Alert. 2001;1:4. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1762.2001.00428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hajje A.H., Atoui F., Awada S., Rachidi S., Zein S., Salameh P. Drug-related problems identified by clinical pharmacist’s students and pharmacist’s interventions. Ann. Pharm. 2012;70(3):169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.pharma.2012.02.004. (Epub 2012 Mar 20) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Zadjali Badriya Analysis of clinical pharmacists’ interventions in a tertiary care teaching hospital in Oman. Sultan Qaboos University Annual Report. 2007;52:2005–2007. [Google Scholar]

- Anton Pottegard, Jesper Hallas, Jens Sondergaard. Pharmaceutical interventions on prescription problems in a Danish pharmacy setting. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2011;33(6):1019–1027. doi: 10.1007/s11096-011-9580-4. (Epub 2011 Nov 15) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieszk Nella., Bhargava Vinay., Pettita Tony., Whitelaw Nancy., Zarowitz Barbara. Quality and cost outcomes of clinical pharmacist interventions in a capitated senior drug benefit plan. J. Manag. Care Pharm. 2002;8(2):124–131. [Google Scholar]

- Bosma Liesbeth, Jansman Frank G.A., Franken Anton M., Harting Johannes W., Van den Bemt Patricia M.L.A. Evaluation of pharmacist clinical interventions in a Dutch hospital setting. Pharm. World Sci. 2007 doi: 10.1007/s11096-007-9136-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charpiat B., Goutelle S., Schoeffler M., Aubrun F., Viale J.-P., Ducerf C., Leboucher G., Allenet B. Prescriptions analysis by clinical pharmacists in the post-operative period: a 4-year prospective study. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2012 Sep;56(8):1047–1051. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2011.02644.x. (Epub 2012 Jan 31) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felicity Smith. Private local pharmacies in low- and middle-income countries: a review of interventions to enhance their role in public health. Tropical Med. Int. Health. 2009;14(3):362–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox Brent I., Andrus Miranda, Hester Kelly, Byrd Debbie C. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2011;75(2) doi: 10.5688/ajpe75237. (Article 37) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Youngmee, Schepers Gregory. Pharmacist intervention documentation in US health care system. Hospital Pharm. 2003;38(12):1141–1147. (Walters Kluwer Health) [Google Scholar]

- King E.D., Wilson M.A., Van L., Emanuel F.S. Documentation of pharmacotherapeutic interventions of pharmacy students. Pharm. Pract. 2007;5(2):83–88. doi: 10.4321/s1886-36552007000200008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davydov Liya, Caliendo Gina C., Smith Lawrence G., Mehl Bernard. Analysis of clinical intervention documentation by dispensing pharmacists in a teaching hospital. Hospital Pharm. 2003;38(4):346–350. (Walters Kluwer Health) [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon G.E., III. Documenting pharmacy student interventions via scannable patient care activity records (PCAR) Pharm. Educ. 2002;2(4):191–197. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon G.E., III Analysis of pharmacy student interventions collected via an internet based system. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2003;67(3):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar S.R., Soumerai S.B. Why most interventions to improve physician prescribing do not seem to work. Commentary Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2003;169(1):30–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanath K.V., Balaji D., Nagakishore C.H., Kumar S.M., Banuprakash M. A study on impact of clinical pharmacist interventions on medication adherence and quality of life in rural hypertensive patients. J. Young Pharm. 2012;4(2):95–100. doi: 10.4103/0975-1483.96623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs Jean, Haw Camilla, Cahill Caroline. Auditing prescribing errors in a psychiatric hospital. Are pharmacist interventions effective. Hospital Pharm. May 2004;11:203–206. [Google Scholar]

- Swain, Lindy D. A pharmacist’s contribution to an ambulatory neurology clinic. Consult. Pharm. 2012;27(1):49–57. doi: 10.4140/TCP.n.2012.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Food and Drug Administration, 2011. Medication errors reports, Strategies to reduce medication errors: working to improve medication safety. US FDA, 08/12/2011.

- Zwikker, Hanneke, van den Bemt, Bart, van den Ende, Cornelia, van Lankveld, Wim, Broeder, Alfons den, van den Hoogen, Frank, van de Mosselaar, Birgit, van Dulmen, Sandra, Development and content of a group-based intervention to improve medication adherence in non-adherent patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Patient Educ Couns. 89 (1), 143–151 (Epub 2012 Aug 9). [DOI] [PubMed]