Abstract

Objective. To systematically evaluate the evidence of whether massage therapy (MT) is effective for neck pain. Methods. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were identified through searches of 5 English and Chinese databases (to December 2012). The search terms included neck pain, neck disorders, cervical vertebrae, massage, manual therapy, Tuina, and random. In addition, we performed hand searches at the library of Nanjing University of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Two reviewers independently abstracted data and assessed the methodological quality of RCTs by PEDro scale. And the meta-analyses of improvements on pain and neck-related function were conducted. Results. Fifteen RCTs met inclusion criteria. The meta-analysis showed that MT experienced better immediate effects on pain relief compared with inactive therapies (n = 153; standardised mean difference (SMD), 1.30; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.09 to 2.50; P = 0.03) and traditional Chinese medicine (n = 125; SMD, 0.73; 95% CI 0.13 to 1.33; P = 0.02). There was no valid evidence of MT on improving dysfunction. With regard to follow-up effects, there was not enough evidence of MT for neck pain. Conclusions. This systematic review found moderate evidence of MT on improving pain in patients with neck pain compared with inactive therapies and limited evidence compared with traditional Chinese medicine. There were no valid lines of evidence of MT on improving dysfunction. High quality RCTs are urgently needed to confirm these results and continue to compare MT with other active therapies for neck pain.

1. Introduction

Neck pain is a very common condition. It has one-month prevalence between 15.4% and 45.3% and 12-month prevalence between 12.1% and 71.5% in adults [1]. Despite its high prevalence, neck pain frequently becomes chronic and affects 10% of males and 17% of females [2].Consequently, neck pain has been a source of disability and may require substantial health care resources and treatments [3–6].

Massage therapy (MT), as one of the earliest and most primitive tools for pain, has been widely used for neck pain. It is defined as a therapeutic manipulation using the hands or a mechanical device, in which numerous specific and general techniques are used in sequence, such as effleurage, petrissage, and percussion [7]. There are, however, inconsistent conclusions on effects of MT for neck pain. Some prior reviews maintained that there was inconclusive evidence on effects of MT for neck pain [8–11], but the others suggested that MT had immediate effects for neck pain [12, 13]. In addition, most reviews did not include Chinese randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of MT for neck pain due to language barrier or limited retrieving resources [8, 9, 11, 12]. But Chinese MT, as one of the primitive complementary and alternative treatments, has been employed by most Chinese patients with neck pain, and a mass of studies have been reported [10]. They are important for evaluating the evidence of MT for neck pain.

Therefore, we performed an updated systematic review of all currently available both English and Chinese publications and conducted quantitative meta-analyses of MT on neck pain and its associated dysfunction to determine whether MT is a viable complementary and alternative treatment for neck pain.

2. Materials and Methods

The following electronic databases were searched from their inception to December 2012: PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, China Knowledge Resource Integrated Database (CNKI), and Wan Fang Data. The main search terms were neck pain, neck disorders, cervical vertebrae, massage, manual therapy, Tuina, and random. And we performed hand searches at the library of Nanjing University of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Reference lists of retrieved articles were also screened. No restrictions on publication status were imposed.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

Only the studies that met the following criteria were included: (1) RCTs of MT for neck pain; (2) neck pain was not caused by fractures, tumors, infections, rheumatoid arthritis, and so forth; (3) MT was viewed as an independent therapeutic intervention for neck pain, which did not combine with other manual therapies such as spinal manipulation, mobilization, and chiropractic; (4) the control interventions included inactive and active therapies; the inactive therapy controls included sham, placebo, no treatment, standard care, and others (i.e., massage + exercise versus exercise); the active therapy controls may be any active treatment not related to MT; (5) the main outcome measures were pain and neck-related dysfunction; no restrictions were set on the measurement tools used to assess these outcomes, since a large variety of outcome measures were employed in the studies; (6) the language was either English or Chinese.

2.2. Data Abstraction

Two reviewers independently extracted data onto predefined criteria in Table 1. We contacted primary authors when relevant information was not reported. Differences were settled by discussion with reference to the original article. For crossover studies, we considered the risk for carryover effects to be prohibitive, so we selected only the first phase of the study. We considered that effects of MT included immediate effects (immediately after treatments: up to one day) and follow-up effects (short-term follow-up: between one day and three months, intermediate-term follow-up: between three months and one year, and long-term follow-up: one year and beyond).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included randomized controlled trials.

| First authors, year, country |

Pain duration | Sample size, mean age (year) |

Duration weeks | Follow-up weeks |

Main outcome assessments |

Experimental group intervention* |

Control group intervention* |

Main conclusion (mean improvements on pain) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irnich [17] 2001 Germany |

42% >5 years | 177 52 |

3 | 12 | Pain VAS (0–100) Cervical mobility |

Massage therapy (MT) (30 min/5 sessions) |

(1) Acupuncture (AC) (2) Sham laser AC (30 min/5 sessions) |

MT (12.70) < AC (25.30); MT (12.70) < sham laser AC (19.20) |

| Cen [18] 2003 USA |

NR | 31 49 |

6 | 6 | Pain NPQ (0–100) ROM |

Chinese traditional massage (CTM) (30 min/18 sessions) |

(1) Exercise (EX) (20 min/day) (2) Standard care (SC) |

CTM (19.22) > EX (7.58) CTM (19.22) > SC (−4.13) |

| Fryer [19] 2005 Australia |

NR | 37 23 |

1 day | — | PPT | Manual pressure release (MPR) (1 session) |

Sham myofascial release (SMR) (1 session) |

MPR (2.05) > SMR (−0.08) |

| Meseguer [20] 2006 Spain |

NR | 54 40 |

1 day | — | Pain VAS (0–10) | Classical strain/counterstrain technique (CST) Modified strain/counterstrain technique (MST) (1 session) |

SC | CST = MST (2.60) CST (2.60) > SC (0.03) |

| Zaproudina [21] 2007 Finland |

11.2 years | 105 42 |

1 or 2 | 48 | Pain VAS (0–100) NDI (0–100) |

MT (30 min/5 sessions) |

(1) Traditional bone setting (TBS) (90 min/5 sessions) (2) Physical therapy (PT) (45 min/5 sessions) |

MT (21.20) < TBS (31.60) MT (21.20) > PT (17.20) |

| Blikstad [22] 2008 UK |

4–12 weeks | 45 24 |

1 day | — | Pain VAS (0–10) ROM |

Myofascial band therapy (MBT) (1 session) |

(1) Activator trigger point therapy (ATPT) (2) Sham ultrasound (SU) (1 session) |

MBT < ATPT MBT = SU |

| Zuo [23] 2008 China |

10.4 years | 60 42 |

2 | — | Pain VAS (0–10) NDI (0–50) |

CTM (30 min/6 sessions) |

Traction (TR) (20 min/14 sessions) |

CTM (5.47) > TR (4.87) |

| Sherman [24] 2009 USA |

7.6 years | 64 47 |

10 | 16 | NDI (0–50) CNFDS |

MT (10 sessions) |

SC | NDI: MT (5.50) > SC (2.20) |

| Jiang [25] 2010 China |

— | 60 <60 |

3 | — | Pain VAS (0–10) | CTM (30 min/18 sessions) |

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) (2/18 sessions) |

CTM (3.40) > TCM (2.16) |

| Madson [26] 2010 USA |

37.9 months | 23 50 |

4 | — | Pain VAS (0–100) NDI (0–50) |

MT plus moist heat packs and EX (60 min/8–12 sessions) |

Joint mobilization (JM) plus moist heat packs and EX (60 min/8–12 sessions) |

MT (8.50) < JM (24.45) |

| Liu [27] 2011 China |

31.6 months | 90 42 |

2 | — | Pain VAS (0–10) NDI (0–50) ROM |

CTM (30 min/10 sessions) |

(1) AC in abdomen (2) AC in neck and shoulder (30 min/10 sessions) |

CTM (3.97) < AC1 (4.78) CTM (3.97) < AC2 (5.93) |

| Zhang [28] 2011 China |

1–3 years | 120 23 |

10 days | 24 | Pain VAS (0–10) | CTM (20 min/10 sessions) |

TR (15 min/10 sessions) |

CTM (5.56) > TR (3.85) |

| Lin [29] 2012 China |

7.7 months | 70 33 |

4 | — | Pain VAS (0–10) ROM |

CTM (12 sessions) |

TCM (3/28 sessions) |

CTM (4.17) > TCM (3.49) |

| Wang [30] 2012 China |

1 week–5 years | 66 38 |

2 | — | Pain VAS (0–100) | CTM (20 min/6 sessions) |

TR (20 min/6 sessions) |

CTM (2.38) > TR (1.39) |

| Topolska [31] 2012 Poland |

50% >11 years | 60 63 |

10–15 days | — | Pain VAS (0–10) NDI (0–50) ROM |

MT plus PT and kinesiotherapy (NR) |

PT and kinesiotherapy (NR) |

MT (1.40) < control (1.63) |

VAS: visual analog scale; ROM: range of motion; NR: not reported; NPQ: Northwick park neck pain questionnaire; PPT: pressure pain threshold; NDI: neck disability index; CNFDS: Copenhagen neck functional disability scale.

*Intervention/dose: number of intervention times/number of sessions, number of Chinese herbal medicines every day/number of sessions.

2.3. Methodological Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of RCTs was assessed independently in line with PEDro scale by two reviewers, which is based on the Delphi list and has been reported to have a fair to good reliability for RCTs of the physiotherapy in systematic reviews. And the authors compared the results and discussed difference according to the PEDro operational definitions until agreement was reached. The PEDro score ranged from 0 to 10, and a higher score represents a better methodological quality. A cut point of 6 was used to indicate high quality studies as it has been reported to be sufficient to determine high quality versus low quality in previous studies [14, 15]. If additional clarification was necessary, we contacted primary authors.

2.4. Data Synthesis and Analysis

The detailed subgroup meta-analyses were performed based on different control therapies. Each subgroup should include at least 2 RCTs. Standardised mean difference (SMD) was used in meta-analyses because the eligible studies assessed the outcome based on different scales (e.g., VAS 0–10 and VAS 0–100). And the SMD and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated in the meta-analyses. We used the more conservative random effects model to account for the expected heterogeneity. The I 2 was used to assess statistical heterogeneity. The reviewers determined that heterogeneity was high when the I 2 was above 75% [16]. The Cochrane Collaboration software (Review Manager Version 5.0 for Windows; Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre) was used for the meta-analyses.

3. Results

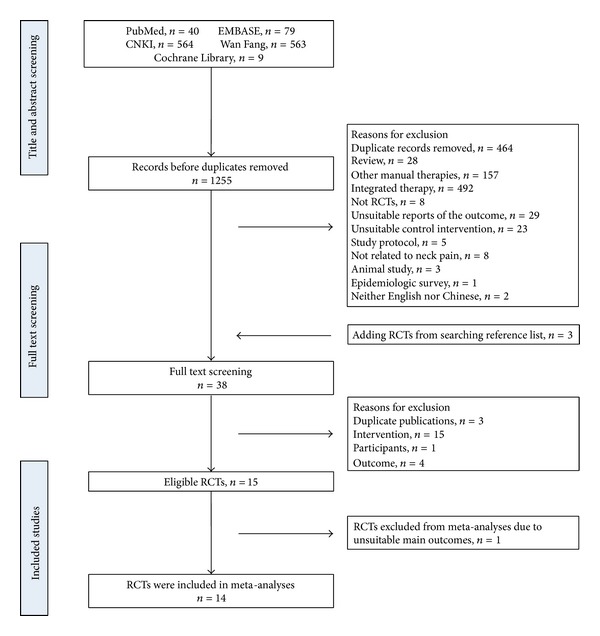

We identified 1255 records from English and Chinese databases. After the initial titles and abstracts screening, we excluded 1220 because of a large number of duplicate records and because some reports failed to meet the inclusion criteria. We retrieved and reviewed 38 full articles including 3 studies from the reference lists of related reviews. 15 RCTs were eligible [17–31]. Of all the excluded studies, the trials were excluded due to duplicate publications (n = 3), interventions (n = 15), participants (n = 1), and outcomes (n = 4) in Table 2. And one RCT was excluded from meta-analyses for its unsuitable main outcomes [22]. The study selection process was summarized in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Studies excluded in full text screening.

| Studies | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Chen et al. (2010) [32] | Intervention: multimodal including massage, mobilization, and manipulation |

| Fan (2010) [33] | Intervention: massage and manipulation |

| Fan et al. (2011) [34] | Intervention: massage and manipulation |

| Fu and Yuan (2001) [35] | Intervention: massage and manipulation |

| Huang (2010) [36] | Intervention: massage and Chinese herb |

| König et al. (2003) [37] | Duplicate publications as Irnich et al. (2001) [17] |

| Li and Fan (2001) [38] | Intervention: massage and manipulation |

| Lin et al. (2004) [39] | Intervention: multimodal including massage, mobilization, and manipulation |

| Lin et al. (2011) [40] | Duplicate publications as Lin et al. (2012) [29] |

| Li (2012) [41] | Intervention: massage and manipulation |

| Mai et al. (2010) [42] | Intervention: high-velocity and low-amplitude manipulation |

| Pan (2011) [43] | Intervention: multimodal including massage, mobilization, and manipulation |

| Qu and Wang (2012) [44] | Intervention: massage or manipulation |

| Sefton et al. (2011) [45] | Participants: healthy adults |

| Tan (2010) [46] | Outcome: Traditional Chinese Medicine Treatment Effect Rating Scale is employed; it is a composite of clinical symptoms, physical examination, and activities of daily life |

| Wang (2010) [47] | Intervention: massage and mobilization |

| Yang and Li (1991) [48] | Intervention: multimodal including massage, mobilization, and manipulation |

| Ylinen et al. (2007) [49] | Intervention: multimodal including mobilization, traditional massage, and passive stretching |

| Zhang et al. (2005) [50] | Outcome: Transcranial Cerebral Doppler and clinical symptoms (headache, vertigo, etc.) |

| Zhang et al. (2011) [51] | Duplicate publications as Zhang et al. (2011) [28] |

| Zhao (2011) [52] | Intervention: massage or manipulation |

| Zhang and Yu (2012) [53] | Outcome: Traditional Chinese Medicine Treatment Effect Rating Scale is employed; it is a composite of clinical symptoms, physical examination, and activities of daily life |

| Zheng and Xu (2011) [54] | Outcome: Traditional Chinese Medicine Treatment Effect Rating Scale is employed; it is a composite of clinical symptoms, physical examination, and activities of daily life |

Figure 1.

Study selection process. RCTs: randomized controlled trials.

One study was contacted to request for mean and standard deviation data on primary outcomes [24]. Another trial was contacted to provide details on therapeutic technique and study design [31].

3.1. Study Characteristics

Fifteen eligible studies including 1062 subjects with mean age of 41.9 ± 12.4 were, respectively, conducted in Australia, China, Finland, Germany, Poland, Spain, USA, and UK between 2001 and 2012. The disease duration ranged from 1 week to 11.2 years and the study duration 1 day to 10 weeks. The session and time of MT, respectively, were 8.1 ± 5.6 (range 1–18) and 31.1 ± 11.7 minutes (range 20–60 minutes). The follow-up time ranged from 6 to 48 weeks.

MT in the studies included Chinese traditional massage, common Western massage, manual pressure release, strain/counterstrain technique, and myofascial band therapy. The control therapies contained inactive therapies (standard care and sham therapies) and active therapies including acupuncture, traction, physical therapy, exercise, traditional bone setting, traditional Chinese medicine, joint mobilization, and activator trigger point therapy. The characteristics of all studies were summarized in Table 1.

3.2. Methodological Quality

The quality scores were presented in Table 3. The quality scores ranged from 5 to 9 points out of a theoretical maximum of 10 points. The most common flaws were lack of blinded therapists (87% of studies) and blinded subjects (80% of studies). Although all studies adopted random assignment of patients, eight trials did not use adequate method of allocation concealment [17–20, 23, 25, 30, 31]. The blinded assessors were not performed in six trials [25, 27–31]. Four studies were lacking of analysis by intention-to-treat because they cancelled the dropout data in the last results [18, 21, 22, 29]. For other items on PEDro scale, the included studies showed higher methodological quality in measure of similarity between groups at baseline, less than 15% dropouts, between-group statistical comparisons, and point measures and variability data.

Table 3.

PEDro scale of quality for included trials.

| Study | Eligibility criteria | Random allocation | Concealed allocation | Similar at baseline | Subjects blinded | Therapists blinded | Assessors blinded | <15% dropouts | Intention- to-treat analysis |

Between- group comparisons |

Point measures and variability data | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irnich et al. [17] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Cen et al. [18] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Fryer and Hodgson [19] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Meseguer et al. [20] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Zaproudina et al. [21] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Blikstad and Gemmell [22] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| Zuo et al. [23] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Sherman et al. [24] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Jiang [25] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Madson et al. [26] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Liu [27] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Zhang et al. [28] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Lin et al. [29] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Wang et al. [30] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Topolska et al. [31] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

0: did not meet the criteria; 1: met the criteria.

3.3. The Effects of MT on Pain

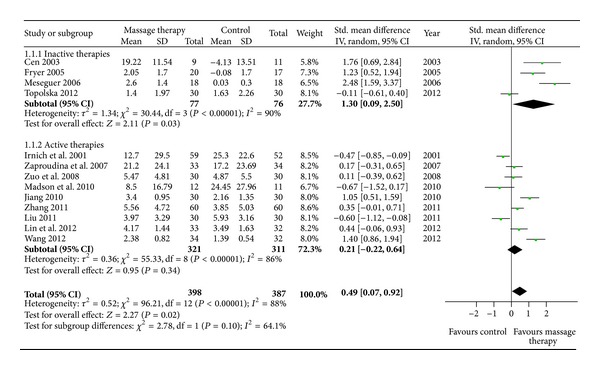

Fourteen RCTs examined the immediate effect of MT for neck pain versus inactive therapies or active therapies. Thirteen of them were included in the meta-analysis [17–21, 23, 25–31]. The aggregated results suggested that MT showed better immediate effects on pain relief (n = 785; SMD, 0.49; 95% CI 0.07 to 0.92; P = 0.02, in Figure 2). But the subgroup meta-analysis suggested that MT only showed superior immediate effects on pain relief compared with inactive therapies (n = 153; SMD, 1.30; 95% CI 0.09 to 2.50; P = 0.03, in Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the immediate effect of MT on pain. CI: confidence interval; IV: independent variable; Std.: standard.

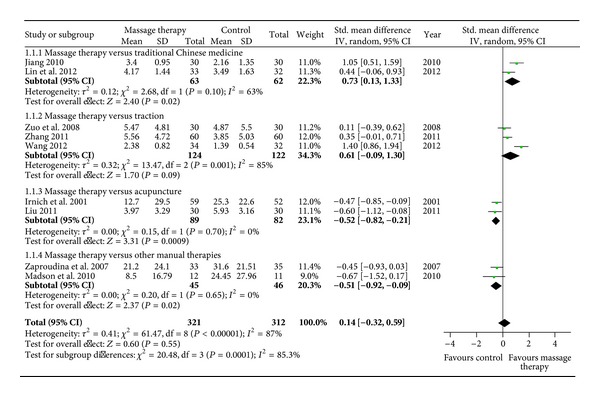

Although MT did not show significant immediate effects on pain relief compared with active therapies (n = 632; SMD, 0.21; 95% CI −0.22 to 0.64; P = 0.34, in Figure 2), MT showed superior immediate effects on pain relief versus traditional Chinese medicine (n = 125; SMD, 0.73; 95% CI 0.13 to 1.33; P = 0.02, in Figure 3) in subgroup meta-analyses based on different active therapies. However, MT did not show significant immediate effects on pain relief versus traction (n = 246; SMD, 0.61; 95% CI −0.09 to 1.30; P = 0.09, in Figure 3). What is more, acupuncture (n = 171; SMD, −0.52; 95% CI −0.82 to −0.21; P = 0.0009, in Figure 3) and other manual therapies (n = 91; SMD, −0.51; 95% CI −0.92 to −0.09; P = 0.02, in Figure 3) showed superior immediate effects on pain relief versus MT.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the immediate effect of MT on pain versus different active therapies. CI: confidence interval; IV: independent variable; Std.: standard.

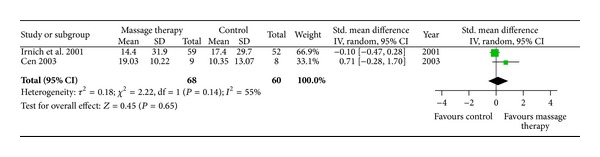

With regard to pain relief, two RCTs assessed short-term effects of MT compared with acupuncture after 12 weeks of follow-up (n = 111; SMD, −0.10; 95% CI −0.47 to 0.28, in Figure 4) [17] and exercise after 6 weeks of follow-up (n = 17; SMD, 0.71; 95% CI −0.28 to 1.70, in Figure 4) [18]. One trial tested the intermediate-term effect of MT versus traditional bone setting (VAS mean improvements, 16.53 versus 23.97) and physical therapy (VAS mean improvements, 16.53 versus 13.54) after 48 weeks of follow-up [21]. The other trial did not report detailed results [28].

Figure 4.

Forest plot of follow-up effects of MT on pain. CI: confidence interval; IV: independent variable; Std.: standard.

3.4. The Effects of MT on Dysfunction

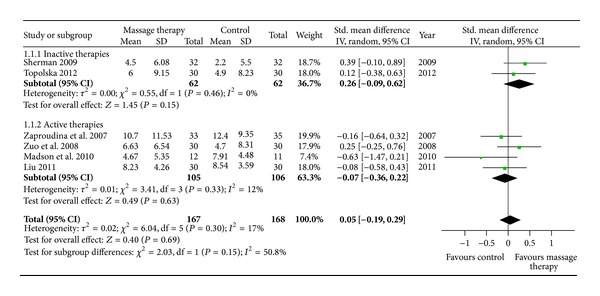

Six RCTs examined the immediate effect of MT on dysfunction by neck disability index (NDI) versus inactive therapies [24, 31] or active therapies [21, 23, 26, 27]. All of them were included in the meta-analysis. The aggregated results suggested that MT did not show significant immediate effects on dysfunction compared with inactive therapies (n = 124; SMD, 0.26; 95% CI −0.09 to 0.62; P = 0.15, in Figure 5) or active therapies (n = 211; SMD, −0.07; 95% CI −0.36 to 0.22; P = 0.63, in Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Forest plot of the immediate effect of MT on dysfunction. CI: confidence interval; IV: independent variable; Std.: standard.

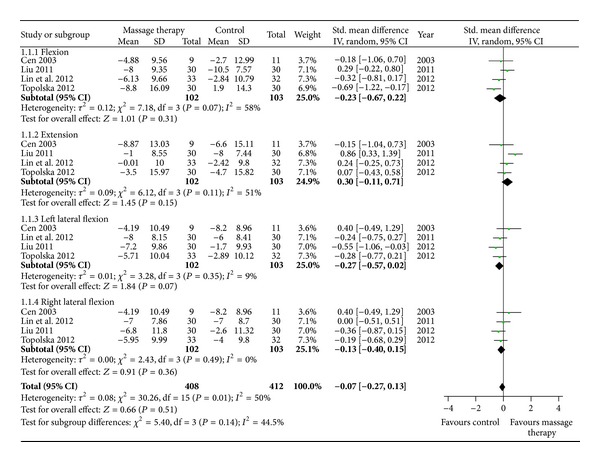

Four RCTs assessed the immediate effect of MT on range of motion of the neck compared with exercise (or standard care) [18], acupuncture [27], traditional Chinese medicine [29], and physical therapy [31]. MT did not show superior effects in range of flexion (n = 205; SMD, −0.23; 95% CI −0.67 to 0.22; P = 0.31, in Figure 6), extension (n = 205; SMD, 0.30; 95% CI −0.11 to 0.71; P = 0.15, in Figure 6), left lateral flexion (n = 205; SMD, −0.27; 95% CI −0.57 to 0.02; P = 0.07, in Figure 6), or right lateral flexion (n = 205; SMD, −0.13; 95% CI −0.40 to 0.15; P = 0.36, in Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Forest plot of the immediate effect of MT on range of motion. CI: confidence interval; IV: independent variable; Std.: standard.

Two trials assessed the follow-up effects of MT on functional improvements by NDI. One study assessed intermediate-term effects of MT compared with traditional bone setting (mean improvements, 4.58 versus 9.46) and physical therapy (mean improvements, 4.58 versus 6.20) after 48 weeks of follow-up [21]. The other tested intermediate-term effects of MT were compared with standard care (mean improvements, 4.7 versus 2.8) after 16 weeks of follow-up [24].

3.5. Adverse Events

Only two studies reported side effects. One study reported that 21% of the participants experienced low blood pressure following treatment [17]. The other trial reported that 9 (about 28%) participants had mild adverse experiences including discomfort, pain, soreness, and nausea [24].

4. Discussion

The purpose of our systematic review was to evaluate the evidence of MT for neck pain. Our meta-analyses found beneficial evidences of MT for neck pain. Compared with inactive therapies, MT showed moderate evidence for immediate improvement of pain, and compared with traditional Chinese medicine there was limited evidence for immediate improvement of pain due to few eligible studies. However, MT did not show better effects versus other active therapies (including acupuncture, traction, and other manual therapies). And there was no evidence that MT showed superior immediate effects on improving dysfunction in patients with neck pain. On follow-up effects, there was not enough evidence of MT for neck pain.

Our review contained six Chinese RCTs of MT for neck pain. Although MT is widely used for neck pain in China, most of the previous reviews included few Chinese RCTs of MT for neck pain due to limitations of retrieving resources and methodological qualities. In our review, all Chinese RCTs performed eligible random allocation and the quality scores were more than 6 in terms of PEDro scores. They failed to blind the subjects and therapists, but three RCTs [27–29] performed eligible concealed allocation, and one [23] employed blinded assessors. What is more, it is difficult to blind the patients and therapists in MT studies. In general, methodological quality of Chinese RCTs of MT for neck is becoming better.

In our review, there were more detailed subgroup analyses based on inventions of control groups. In order to address the question of what her MT is an effective therapy for neck pain, we analyzed studies comparing MT with inactive therapies including sham therapies and standard care. The result only showed that MT may be more effective than standard care. And we also compared MT with active therapies including acupuncture, traction, traditional Chinese medicine, physical therapy, exercise, and other manual therapies for assessing the question of what her MT is a better therapy for neck pain. The meta-analysis showed that MT has better immediate effects than traditional Chinese medicine, but eligible studies were few. And the treatment process of traditional Chinese medicine is usually longer; 3 to 4 weeks of traditional Chinese medicine may be shorter for neck pain [25, 29]. So we considered that MT did not show better effects than other active therapy. In addition, we also paid attention to dysfunction related neck pain and follow-up effects of MT for neck pain.

4.1. Agreements and Disagreements with Other Reviews

The Patel systematic review was the most last review of MT for neck pain, which included fifteen trials (published from 2003 to 2009) with low or very low methodological quality. And it supported the effectiveness of massage for neck pain remained uncertain [8]. Its result concurred with the result of our review, but our review excluded a few studies that Patel had included because they used treatments related to MT in control groups [55–58]. These were limited to evaluating the specific effect of MT. And some studies were not eligible for inclusion criteria of our review [59–62]. Moreover, our systematic review included eight new RCTs [23, 25–31] published from 2008 to 2012. Of notes, our review contained six Chinese RCTs of MT for neck pain [23, 25, 27–30]. And we assessed the effect of MT on neck pain and its associated dysfunction. We also paid attention to the immediate and follow-up effects of MT. So our update provides stronger evidence of MT for neck pain.

Our results differ from systematic reviews [12, 13]. Ottawa panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, including five RCTs with high methodological quality (>3) according to the Jadad scale, suggested that MT was effective for relieving immediate posttreatment neck pain symptoms [12]. One suspected reason for this difference is that a mass of new RCTs [20, 21, 23, 25–31] have been published, which were not included in their review. Another possible explanation for the difference is that Jadad scale was replaced by PEDro scale in our review, which is a more detailed method based on the Delphi list and has been reported to have a fair to good reliability for RCTs of the physiotherapy in systematic reviews. In addition, detailed meta-analyses were performed based on more RCTs in our review. Ottawa panel clinical practice guidelines declined to combine the trials because of fewer trials. Moreover, we separately compared MT with inactive therapies and active therapies, and assessed the effect of MT on neck pain and its associated dysfunction in our review. More eligible RCTs, classification of quantitative data synthesis, and detailed assessment of MT on neck pain and its associated dysfunction strengthened our confidence in our systematic review.

4.2. Limitations

There are several limitations in our review as follows. (a) Although the predetermined cutoff 6 was exceeded, there were serious flaws in blinding methods of most Chinese RCTs. It is difficult to blind the patients and impossible to blind the therapists, but blinded assessors and concealed allocation must attempt to make up for the lack of blinding. However, some Chinese RCTs did not perform these compensated methods. Thus, these studies could not be considered to be of high quality. (b) Our review may also be affected by dosing parameters of MT such as duration (time of each MT), frequency (sessions of MT per week), and dosage (size of strength). MT commonly combines different techniques (stroking, kneading, percussion, etc.), and each therapist may perform them in different dosing parameters. So the dose-finding studies are warranted to establish a minimally effective dose. (c) The results may be influenced by different outcome measures of pain and dysfunction in eligible RCTs. So the reliable and valid outcome measures is essential to reduce bias, provide precise measures and perform valid data synthesis. (d) There were less eligible trials in some subgroups of meta-analyses because of strict eligibility criteria for considering studies in our review. It may influence combining results, but low eligibility criteria would generate more doubtful results. (e) The majority of trials did not report adverse events, so it was not clear from the reports whether adverse effects had been measured or not.

5. Conclusions

Although there were no valid lines of evidence of MT on improving dysfunction in patients with neck pain, this systematic review found moderate evidence of MT on improving pain in patients with neck pain compared with inactive therapies and limited evidence compared with traditional Chinese medicine due to few eligible studies. These are beneficial evidence of MT for neck pain. Assuming that MT is at least immediately effective and safe, it might be preliminarily recommended as a complementary and alternative treatment for patients with neck pain. But more high quality RCTs are urgently needed to confirm these results and continue to compare MT with other active therapies for neck pain.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Hogg-Johnson S, van der Velde G, Carroll LJ, et al. The burden and determinants of neck pain in the general population: results of the bone and joint decade 2000–2010 task force on neck pain and its associated disorders. Spine. 2008;33(4):S39–S51. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31816454c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bovim G, Schrader H, Sand T. Neck pain in the general population. Spine. 1994;19(12):1307–1309. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199406000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bokarius AV, Bokarius V. Evidence-based review of manual therapy efficacy in treatment of chronic musculoskeletal pain. Pain Practice. 2010;10(5):451–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2010.00377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Côté P, Cassidy JD, Carroll L. The Saskatchewan health and back pain survey: the prevalence of neck pain and related disability in Saskatchewan adults. Spine. 1998;23(15):1689–1698. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199808010-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Linton SJ, Hellsing A-L, Halldén K. A population-based study of spinal pain among 35–45-year-old individuals. Prevalence, sick leave, and health care use. Spine. 1998;23(13):1457–1463. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199807010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mäkelä M, Heliövaara M, Sievers K, Imprivaara O, Knekt P, Aromaa A. Prevalence, determinants, and consequences of chronic neck pain in Finland. The American Journal of Epidemiology. 1991;134:1356–1367. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imanura M, Furlan AD, Dryden T, Irvin EL. Massage therapy. In: Dagenais S, Haldeman S, editors. Evidence-Based Management of Low Back Pain. St. Louis, Mo, USA: Elsevier; 2012. pp. 216–268. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haraldsson BG, Gross AR, Myers CD, et al. Massage for mechanical neck disorders. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004871.pub3.CD004871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gross AR, Goldsmith C, Hoving JL, et al. Conservative management of mechanical neck disorders: a systematic review. The Journal of Rheumatology. 2007;34:1083–1102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kong LJ, Zhan HS, Cheng YW, Yuan WA, Chen B, Fang M. Massage therapy for neck and shoulder pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:10 pages. doi: 10.1155/2013/613279.613279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tugwell P. Philadelphia panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines on selected rehabilitation interventions for neck pain. Physical Therapy. 2001;81(10):1701–1717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brosseau L, Wells GA, Tugwell P, et al. Ottawa panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines on therapeutic massage for neck pain. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 2012;16:300–325. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bronfort G, Haas M, Evans R, Leininger B, Triano J. Effectiveness of manual therapies: the UK evidence report. Chiropractic and Osteopathy. 2010;18, article 3 doi: 10.1186/1746-1340-18-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maher CG, Sherrington C, Herbert RD, Moseley AM, Elkins M. Reliability of the PEDro scale for rating quality of randomized controlled trials. Physical Therapy. 2003;83(8):713–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macedo LG, Elkins MR, Maher CG, Moseley AM, Herbert RD, Sherrington C. There was evidence of convergent and construct validity of physiotherapy evidence database qualityscale for physiotherapy trials. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2010;63(8):920–925. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. British Medical Journal. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Irnich D, Behrens N, Molzen H, et al. Randomised trial of acupuncture compared with conventional massage and “sham” laser acupuncture for treatment of chronic neck pain. British Medical Journal. 2001;322(7302):1574–1578. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7302.1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cen SY, Loy SF, Sletten EG, Mclaine A. The effect of traditional Chinese therapeutic massage on individuals with neck pain. Clinical Acupuncture & Oriental Medicine. 2003;4(2-3):88–93. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fryer G, Hodgson L. The effect of manual pressure release on myofascial trigger points in the upper trapezius muscle. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 2005;9(4):248–255. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meseguer AA, Fernández-de-las-Peñas C, Navarro-Poza JL, Rodríguez-Blanco C, Gandia JJB. Immediate effects of the strain/counterstrain technique in local pain evoked by tender points in the upper trapezius muscle. Clinical Chiropractic. 2006;9(3):112–118. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zaproudina N, Hänninen OOP, Airaksinen O. Effectiveness of traditional bone setting in chronic neck pain: randomized clinical trial. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. 2007;30(6):432–437. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blikstad A, Gemmell H. Immediate effect of activator trigger point therapy and myofascial band therapy on non-specific neck pain in patients with upper trapezius trigger points compared to sham ultrasound: a randomised controlled trial. Clinical Chiropractic. 2008;11(1):23–29. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zuo Y, Fang M, Jiang S, Yan J. Clinical study on Tuina therapy for cervical pain and disability quality of life of patients with cervical spondylosis. Shanghai Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2008;42:54–55. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Hawkes RJ, Miglioretti DL, Deyo RA. Randomized trial of therapeutic massage for chronic neck pain. Clinical Journal of Pain. 2009;25(3):233–238. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31818b7912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang YQ. Clinical research on the treatment of cervical spondylotic radiculopathy by Tuina manipulation of give priority to massage Jiaji acupoint [dissertation] Jinan, China: Shandong TCM University; 2010 (Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Madson TJ, Cieslak KR, Gay RE. Joint mobilization vs massage for chronic mechanical neck pain: a pilot study to assess recruitment strategies and estimate outcome measure variability. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. 2010;33(9):644–651. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu JW. Comparative research on cervical spondylopathy treating by Bo’s abdominal acupuncture, acupuncture, and massage treatment [dissertation] Guangzhou, China: Guangzhou TCM University; 2011 (Chinses) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang J, Lin Q, Yuan J. Therapeutic efficacy observation on tuina therapy for cervical spondylotic radiculopathy in adolescence: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Acupuncture and Tuina Science. 2011;9(4):249–252. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin LL, Liao J, Wang SZ, Yan XD. The evaluation of massage therapy for cervical spondylotic by functional instrument of neck muscle. Guangming Zhong Yi. 2012;27:323–324. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang GM, Ji Q, Zhao GH. Immediate effects of foulage manipulation for neck pain. Lishizhen Medicine and Materia Medica Research. 23:2261–2262. 2012 (Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Topolska M, Chrzan S, Sapuła R, Kowerski M, Soboń M, Marczewski K. Evaluation of the effectiveness of therapeutic massage in patients with neck pain. Ortopedia Traumatologia Rehabilitacja. 2012;14:115–124. doi: 10.5604/15093492.992301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen LS, Wu SL, Mai MQ Rehabilitation medical association professional committee of China. Immediate and short term effect on mechanical neck pain after a single manual therapy and physical modality therapy in subjects: a randomized controlled trial. Proceedings of the 7th Chinese Congress on Rehabilitation; Nanning, China. pp. 109–117. November 2010 (Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fan ZG. The massage technique treatment nerve root cervical vertebra got sick 120 example curative effect observation. Chinese Manipulation & Rehabilitation Medicine. 2010;1:47–48. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fan JQ, Guo CX, Chen BL, Lin DK, Xie WX. The observation of effects of Guo’s manual therapy for nerve root type cervical spondylosis. The Journal of Practical Medicine. 2011;27:2267–2269. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fu ZX, Yuan JL. Studies on manual therapy’s effectiveness of cervical spondylosis of the vertebral artery type. The Journal of Cervicodynia and Lumbodynia. 2001;22:8–11. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang DL. Arm neck and shoulder massage treatment of nerve root type cervical spondylosis clinical observation [dissertation] Chengdu, China: Chengdu TCM University; 2010 (Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 37.König A, Radke S, Molzen H, et al. Randomised trial of acupuncture compared with conventional massage and “sham” laser acupuncture for treatment of chronic neck pain—range of motion analysis. Zeitschrift für Orthopädie und ihre Grenzgebiete. 2003;141(4):395–400. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-41566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li JB, Fan YH. The effect on blood flow of the brain of one finger zen for vertebral artery type of cervical spondylosis. Modern Rehabilitation. 2001;5:86–87. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin L, Liu XZ, Feng RH. The effect of Tuina versus traction for cervical spondyllosis. Chinese Manipulation & Qi Gong Therapy. 2004;20:p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin LL, Liao J, Wang SZ, Yan XD. Manipulations based on MCU systematic review in treating 33 case of cervical syndrome. Journal of Fujian University of TCM. 2011;21:4–6. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li RF. The study of traditional Chinese massage for cervical spondylosis. Chinese Journal of Ethnomedicine and Ethnopharmacy. 2012;13:p. 89. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mai M-Q, Wu S-L, Ma C, Chen L-S. Manipulation and physical therapy for patients with chronic mechanical neck pain: comparisons of immediate and short-term effects in pain and joint motion. Journal of Clinical Rehabilitative Tissue Engineering Research. 2010;14(46):8691–8694. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pan WS. Tuina for nerve root type cervical spondylosis. Contemporary Medicine. 2011;17:p. 150. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qu L, Wang ZD. The study of cervical physiological curve of mechanical equilibrium Tuina for cervical spondylosis. Heilongjiang Journal of TCM. 2012;3:20–22. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sefton JM, Yarar C, Carpenter DM, Berry JW. Physiological and clinical changes after therapeutic massage of the neck and shoulders. Manual Therapy. 2011;16(5):487–494. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tan QR. Clinical study on the efficacy of treating local cervical spondylosis between self-massage and manipulation [dissertation] Guangzhou, China: Guangzhou TCM University; 2010 (Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang FY. 32 cases of manual therapy for nerve root type cervical spondylosis. Journal of Chinese TCM Information. 2010;2:p. 140. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang JW, Li GH. Clinical observation of massage therapy for cervical spondylosis. Chinese Journal of Sports Medicine. 1991;10:233–235. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ylinen J, Kautiainen H, Wirén K, Häkkinen A. Stretching exercises vs manual therapy in treatment of chronic neck pain: a randomized, controlled cross-over trial. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2007;39:126–132. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang SQ, Shi X, Zhang JP. The therapeutic effect of acupoint massage on vertebral artery type cervical spondylosis and its influence on hemodynamics. The Journal of Traditional Chinese Orthopedics and Traumatology. 2005;17:11–12. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang JF, Lin Q, Yuan J Association of Chinese Medicine. The observation of effects of manual therapy for cervical spondylosis in adolescence. Proceedings of the 12th Chinese Congress on Tuina; Nanning, China. pp. 477–480. November 2011 (Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao K. Manual therapy for cervical spondylosis. Journal of Chinese TCM Information. 2011;3:58–60. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang J, Yu ZL. Clinical observation of strong Tuina for vertebral artery type of cervical spondylosis. Journal of Practical TCM. 2012;28:p. 394. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zheng MQ, Xu SN. Clinical observation of acupoint massage for cervical spondylosis. Guangming Zhong Yi. 2011;26:531–532. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fernández-de-las-Peñas C, Alonso-Blanco C, Fernández-Carnero J, Carlos Miangolarra-Page J. The immediate effect of ischemic compression technique and transverse friction massage on tenderness of active and latent myofascial trigger points: as pilot study. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 2006;10(1):3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gemmell H, Miller P, Nordstrom H. Immediate effect of ischaemic compression and trigger point pressure release on neck pain and upper trapezius trigger points: a randomised controlled trial. Clinical Chiropractic. 2008;11(1):30–36. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gemmell H, Allen A. Relative immediate effect of ischaemic compression and activator trigger point therapy on active upper trapezius trigger points: a randomised trial. Clinical Chiropractic. 2008;11(4):175–181. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kostopoulos D, Nelson AJ, Jr., Ingber RS, Larkin RW. Reduction of spontaneous electrical activity and pain perception of trigger points in the upper trapezius muscle through trigger point compression and passive stretching. Journal of Musculoskeletal Pain. 2008;16(4):266–278. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Briem K, Huijbregts P, Thorsteinsdottir M. Immediate effects of inhibitive distraction on active range of cervical flexion in patients with neck pain: a pilot study. Journal of Manual and Manipulative Therapy. 2007;15(2):82–92. doi: 10.1179/106698107790819882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hanten WP, Barrett M, Gillespie-Plesko M, Jump KA, Olson SL. Effects of active head retraction with retraction/extension and occipital release on the pressure pain threshold of cervical and scapular trigger points. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. 1997;13(4):285–291. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hanten WP, Olson SL, Butts NL, Nowicki AL. Effectiveness of a home program of ischemic pressure followed by sustained stretch for treatment of myofascial trigger points. Physical Therapy. 2000;80(10):997–1003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yağci N, Uygur F, Bek N. Comparison of connective tissue massage and spray-and-stretch technique in the treatment of chronic cervical myofascial pain syndrome. The Pain Clinic. 2004;16(4):469–474. [Google Scholar]