Abstract

Faulty inhibition is implicated in age-related working memory decline. ERP signs of selection and inhibition of items in working memory (WM) are, respectively, a cue-locked parietal positivity (~ 350 ms) and a probe-locked frontal negativity (~ 520 ms). To determine when in the older age range differences in selective and inhibitory processes might occur, ERPs were recorded in a WM task from 20 young (20–28), 20 young-old (60–70) and 20 old-old (71–82) adults. A 4-digit display was followed by a cue indicating which 2 of 4 digits were relevant. Proactive interference (PI), the reaction time difference between a matching and non-matching to-be-ignored digit was larger, relative to the young, in both older groups. Compared to the young, both the cue- and probe-locked activities were prolonged in the older groups. Although there were no topographic differences among the age groups, the prolonged PI and associated ERPs suggest a relative age-related deficit in inhibition.

Keywords: Working Memory, Proactive Interference, Cognitive Aging, Selection, Event-Related Potential

1. Introduction

Working memory (WM) refers to the concurrent maintenance and processing of task-relevant information while keeping task-irrelevant information from interfering with current task goals (Baddeley, 1986; Baddeley & Hitch, 1974). WM is not a unitary store. For example, in the embedded-processes model, Cowan, (1999) has proposed that information is represented at three levels: information in the focus of attention, which is maintained and can be directly manipulated in WM; information not currently in the focus of attention, but which is active in long term memory (LTM) and can be accessed at any time; information in LTM which is no longer active. In support of this conceptual viewpoint, behavioral studies have shown that information once relevant but subsequently removed from the focus of attention can affect recognition, which is manifested by proactive interference (PI)(Oberauer, 2001, 2005; Yi, Driesen, & Leung, 2009; Yi & Friedman, 2011). For example, in a delayed recognition task (Oberauer, 2001), after a list of words was presented, participants were cued to remember a subset of the words and ignore the others. Thus, the to-be-ignored words became task-irrelevant. At the probe stage, participants had to decide whether the probe word matched one of the relevant words they were required to maintain in WM. PI was defined as the reaction time (RT) difference between rejecting the no-longer-relevant words (i.e., intrusion probes) and rejecting words not on the initial list (non-intrusion probes), where both required negative responses. Even though participants correctly rejected the task-irrelevant words, a reliable PI effect was found, i.e., RT was longer to the intrusion than non-intrusion probe, indicating that the task-irrelevant words were still activated in LTM, although presumably not in the focus of attention.

Successfully selecting task-relevant information and removing or inhibiting task-irrelevant information from the focus of attention are critical for fulfilling the goals of ongoing cognitive task performance and have been suggested to be the most important functions of WM (Baddeley, 1996). Older adults have shown greater difficulty than younger adults when asked to ignore task-irrelevant information (e.g., Hasher & Zacks, 1988; Oberauer, 2001) and, not surprisingly, a well-established finding is that WM performance declines as one gets older. A deficit in inhibiting task-irrelevant information has been suggested as a critical factor in this decline (Hasher & Zacks, 1988). Hence, a large number of studies have shown impaired inhibitory function in older (above 60 years old) compared to young adults during WM tasks (Borella, Carretti, & De Beni, 2008; Oberauer, 2001, 2005; Persad, Abeles, Zacks, & Denburg, 2002; Robert, Borella, Fagot, Lecerf, & de Ribaupierre, 2009; Zacks, Radvansky, & Hasher, 1996). For example, Oberauer (2001) found that it took longer in older, relative to younger, adults to reject the familiar, but task irrelevant probe, suggesting that the prolongation may have been due to an age-related decline in inhibitory function (but, see discussion of Oberauer, 2005 and Duarte, et al., 2013 below)

A further example of putative reduced inhibitory control in older adults has been provided by De Beni & Palladino, (2004). In their behavioral WM updating study, a series of words was presented sequentially and participants were required to maintain in WM the word representing the smallest item from the list, and remember it when subsequently probed. To perform the task correctly, the participant had to update WM whenever an item had been encountered that was smaller than any of the items that had preceded it. In this task, failure to inhibit or remove a no-longer-relevant word interfered with recall of the task-relevant items. Specifically, the results showed that memory-recall accuracy decreased and intrusions from irrelevant words increased with increasing age. To determine at which ages in the older-adult lifespan the decline was more pronounced, De Beni & Palladino (2004) recruited three groups of older adults, young-old (55–65 years of age), old (66–75 years of age) and old-old (76–88 years of age). The old-old participants showed a larger intrusion error rate than the young-old and old participants, consistent with the results of other WM tasks and neuropsychological measurements, in which poorer inhibitory functions have been found in old-old (usually above 70 or 75 years old) than young-old participants (usually below 70 years of age --Arbuckle & Gold, 1993; Borella, et al., 2008; Gold & Arbuckle, 1995; Norman, Kemper, Kynette, Cheung, & Anagnopoulos, 1991; Persad, et al., 2002). These data suggest that older adults were not as able as the young to efficiently inhibit the irrelevant items from the activated portion of LTM. Further and importantly, this age trajectory is a key reason that young-old and old-old adults were recruited for the current study.

On the other hand, the results of a subsequent behavioral study by Oberauer, (2005) suggested that, rather than a deficit in inhibition, older adults might not be able to maintain within the focus of attention the binding of the item’s context with its content. In Oberauer’s (2005) study, in which there were several tasks, two most relevant to the current investigation are described here. The modified Sternberg task was similar to the paradigm used in Oberauer’s (2001) initial study, and presumably required inhibition of task-irrelevant items in the activated portion of LTM. By contrast, in the local recognition task inhibition was not necessary. In this latter task, words were presented sequentially, with each word enclosed within a frame. After a 500 ms delay following the disappearance of the last word, the probe was also presented within a frame. The participant had to compare the probe with the words in the same frame from the initial memory list. In this paradigm, PI refers to the RT difference between rejecting a probe that was in the memory list but had been presented within a different frame, and a probe not in the list. Therefore, to produce a correct response, participants had to bind the frame with the word, as failure to retrieve the word and its contextual frame would result in an error. If an inhibition deficit accounts for the prolongation of PI in the older adults, one would expect to observe greater age-related differences in the modified Sternberg task than in the local recognition task, as inhibition is involved in the former but not the latter. However, PI prolongation of the same magnitude was observed in young and older adults for both tasks, but was larger overall for the older adults. This pattern of findings cannot easily be explained by the inhibition-deficit hypothesis. Rather, Oberauer (2005) suggested that a deficit in context-content binding was responsible for the age-related difference in PI.

Although it has been suggested that older adults’ ability to inhibit task-irrelevant information is impaired, relatively little is known about age-related differences in the timing of the processes implicated in the selection of relevant information from and the removal of no-longer-relevant information out of WM. However, to assess the temporal patterning of selective and inhibitory processes across the older-adult lifespan, one needs a technique that can track these cognitive processes in a manner in line with the speed at which they transpire. The event-related brain potential (ERP) provides such high-resolution temporal information in the millisecond range. This kind of precise temporal information is not available with more sluggish hemodynamic techniques, which typically take seconds to reach peak activity.

Previous ERP studies have shown that the enhancement of a parietal positivity, most likely the P3b or P300 (Donchin & Coles, 1988; Sutton, Braren, Zubin, & John, 1965), is associated with updating task-relevant information and removing no-longer-relevant information from the focus of attention in young adults (Kiss, Pisio, Francois, & Schopflocher, 1998; Kiss, Watter, Heisz, & Shedden, 2007). For example, in Kiss et al.‘s (1998) study, a series of digits (2 to 9 digits) was presented sequentially followed by a probe digit pair. Participants had to decide whether the digit pair matched the last 2 digits in the series. As participants did not know the string length, they had to maintain the last 2 digits within the focus of attention in WM, while removing the irrelevant digits from that focus. The amplitude of the positivity at centro-parietal sites increased as serial position increased, (i.e., up to 9 digits). Hence, this component could have reflected the shifting of internal attention to the current task-relevant digits and the removal of the no-longer-relevant digits from the focus of attention.

However, few WM investigations have assessed the updating and maintenance of information in older adults. In one such investigation, Friedman (2007) used a digit-WM experiment, in which 4, 5, 7, 9 or 11 digits were presented sequentially in strings (participants did not know which string length would occur prior to a given trial). Subjects were instructed to remember, in order of presentation, the last 4 digits presented during the trial. During the low-load, delayed match-to-sample task (DMS), participants were asked to remember the first 4 digits. At test, participants had to decide whether the 4 testing digits were in the same or different order than the 4 relevant digits in the previous string of digits. A match occurred if the test digits were identical in sequence to the four to-be-remembered digits. In the higher-load WM condition, participants had to update the contents of WM when the fifth digit occurred. Following this digit, participants would have to remove the first digit from the focus of attention in WM and shift their attention to the next digit. When the fifth digit occurred, young adults showed a significant increment in P3 amplitude, indicating that WM had been updated and that this digit was now within the focus of attention. Unlike the young adults, a P3 amplitude increase was not observed in older adults. However, when WM load was low, as in the DMS task, and participants simply had to remember the first 4 digits of the series, P3 amplitude to the fourth digit (when updating would have been completed) was just as large in the older adults as it was in the young adults. Coupled with an age-related performance decrement in the WM but not the DMS task, these findings are consistent with the notion that older adults may be less efficient in shifting their internal attention to task-relevant representations in WM.

Unlike the previously discussed ERP paradigms, recent investigations of WM have included a cue to enable participants to shift their internal attention to a relevant subset of items in WM. The cue is typically followed by a subsequent probe of the contents of WM. For example, a very recent study has suggested that older adults do not have a deficit in selecting task-relevant information, and are able to remove irrelevant items from the focus of attention (Duarte, et al., 2013). In Duarte et al.’s study, two, three or four color squares were presented simultaneously to each hemisphere, and both young and older adults were instructed to remember all of the color squares presented to one hemisphere and ignore the color squares presented to the other hemisphere. Following an 800 ms delay, in the retro-cue condition, an arrow indicated the location of the to-be-tested probe item. In the no-cue condition, a central cross instead of a retro-cue was presented, in which selection was not needed. In both conditions, the cue was followed by a subsequent probe of the contents of WM. By subtracting the waveforms elicited over the contralateral from those over the ipsilateral hemisphere, a sustained negative waveform (labeled, contralateral delay activity, or CDA; see also Vogel & Machizawa, 2004) was obtained. The authors interpreted the CDA as reflecting the amount of information held in WM. The authors found that, in both young and older adults, the CDA elicited in the retro-cue condition was smaller than that elicited in the no-cue condition, suggesting that the WM load was reduced following the retro cue. That is, the no-longer-relevant information had been removed from WM. This result suggests that the older adults were just as efficient as the young in removing the no-longer-relevant information from the focus of attention.

According to the embedded-processes model, removal of irrelevant information from the focus of attention and inhibition of activated representations in LTM are distinct processes (Oberauer, 2001). Hence, as discussed earlier, the no-longer-relevant information, though removed from the focus of attention, is still active within LTM and, therefore, can influence decisions made at the probe stage. Hence, one possibility is that older adults might exhibit a deficit at the probe stage (which Duarte et al. did not include in their experiment) in rejecting the task-irrelevant information from the active portion of LTM (Oberauer, 2001; Yi & Friedman, 2011).

In fact, some recent ERP studies that have examined PI resolution at the probe stage of WM tasks suggest that a negative-going, frontally-oriented component between 300 and 500 ms (labeled the frontal negativity or FN; see Folstein & Van Petten, 2008 for a review) is associated with PI resolution, that is, rejecting a familiar but task-irrelevant probe. Unfortunately, most of these studies have been performed with young adults as participants (Du, et al., 2008; Tays, Dywan, Mathewson, & Segalowitz, 2008; Tays, Dywan, & Segalowitz, 2009; Yi & Friedman, 2011; Zhang, Wu, Kong, Weng, & Du, 2010)). In the only study, to the best of our knowledge, that has compared young and older adults in this paradigm, Tays, et al., (2008) asked participants to view a 4-letter memory set followed by a probe. Participants then decided whether the probe matched a letter from the memory set. The negative probe could either match a letter comprising the memory set of the previous trial (familiar condition), or not match any letter in the previous two trials (neutral condition). Compared to the neutral condition, a larger frontal negativity, at around 450 ms, was observed in the familiar condition for the young but not the older adults. These data could be interpreted to mean that older adults had difficulty in rejecting (i.e., inhibiting) the familiar, but now task-irrelevant probe item that was active in LTM.

Similarly, findings from the Stroop task, in which a pre-potent response must be overridden to produce a correct decision, have shown that the FN, which has been reported to be greater in the incongruent (word and color do not match) than congruent (word and color match) condition, is attenuated in older-relative to young-adult participants (West, 2004; West & Alain, 2000; West & Schwarb, 2006). Taken as a whole, the WM-probe and Stroop findings suggest that diminished inhibitory processes in older adults may be reflected in the age-related alterations of the FN at the probe stage in WM tasks.

Hence, although age-related studies of PI resolution have been performed, the vast majority at the probe stage (Du, et al., 2008; Tays, et al., 2008; Tays, et al., 2009; Zhang, et al., 2010), information on declines in the selection and inhibition or removal of information at the cue stage in WM has, to the best of our knowledge, only been investigated in one study (Duarte, et al., 2013). In addition, it remains unclear whether a deficit in inhibition accounts for the age-related differences in rejecting the activated information in LTM at the probe stage. Therefore, the primary purpose of the current study was to investigate age-related differences in the timing of selective and inhibitory processes, respectively at the cue and probe stages in WM.

As a starting point for assessing age-related difference in WM, Yi and Friedman (2011) investigated cue- and probe-related processes by recording ERPs with young adult participants. In this study, three types of cues were compared. In the selection condition, a 4-digit, memory-set display was followed by a selection cue indicating which two of the four digits to remember for the probe stage. In the neutral-2 and neutral-4 control conditions, participants had to remember, respectively, either 2 or 4 digits and maintain them in WM following the corresponding cue, after which selection was not necessary. Consistent with task-irrelevant information in the activated portion of LTM influencing the probe-related decision, a reliable PI effect was found. The ERP data indicated, in similar fashion to the data of Kiss et al (1998, 2007), a larger positivity (i.e., P3 or P3b; Donchin & Coles, 1988) at parietal locations to the selection- relative to the neutral-2 and neutral-4 cues. This positivity (~350 ms), therefore, could have reflected the internal shifting of attention to the task-relevant information, thereby initiating the selection of the task-relevant digits. By contrast, the neutral-4 and selection conditions shared the same initial memory load, i.e., 4 digits. Therefore, the greater negative-going (or less positive) activity at frontal sites following the presentation of the selection relative to the neutral-4 cue could have reflected the removal of the no-longer-relevant information from the focus of attention (labeled FNcue – ~490 ms). At the probe stage, the negative-going activity elicited by the probe (intrusion greater than non-intrusion; labeled FNprobe – ~520 ms) was largest over fronto-central scalp and could have reflected the processes involved in overcoming the interference engendered by the familiar, but now irrelevant, intrusion probe (Du, et al., 2008; Tays, et al., 2008; Tays, et al., 2009; Zhang, et al., 2010).

Hence, here we used Yi and Friedman’s (2011) young adults as the baseline control group and the same digit WM recognition task from that investigation. As mentioned earlier, based on prior data that showed a distinction in WM processes between old-old and young-old adults (Arbuckle & Gold, 1993; Borella, et al., 2008; De Beni & Palladino, 2004; Gold & Arbuckle, 1995; Norman, et al., 1991; Persad, et al., 2002), two groups of older adults were recruited to more precisely chart age-related differences in putative selection and inhibition processes. The young-old group comprised participants between the ages of 60 and 70, whereas the old-old group included participants between the ages of 71 and 82. The current WM paradigm was designed to be relatively easy to perform, so that older adults were expected to be as accurate as their young-adult counterparts. Hence, one important aspect of the present methodology is that age-related differences in neural activity, if observed, cannot be due, in any simple fashion, to age-related differences in accuracy.

Thus, based on the embedded-processes model, we made the following predictions for the behavioral results:1) if older adults can successfully remove information from the focus of attention, decisions at the probe stage would be based on the items remaining within the focus of attention. That is, the RT to the positive probe in the selection condition would be similar to that in the neutral-2 condition, whereas both should be faster than that of the neutral-4 condition. However, if older adults have difficulty in removing information from the focus of attention, the RT of the positive probe in the selection condition would be similar to that in the neutral-4 condition; 2) if a deficit in inhibition accounts for the age-related differences in PI resolution, we predicted larger intrusion costs (i.e., PI) with increased age; 3) similarly, if older adults have a deficit in binding the relevant information with its context (i.e., location), we also predicted larger PI with increased age. However, it should be noted that, given the current experimental conditions, it would be difficult to distinguish between the inhibition- and context-content binding-deficit accounts of prolonged PI in older adults.

Our ERP predictions were based on prior investigations that had compared young- and older-adult participants (e.g., Tays, et al., 2008), and we extrapolated from the previously published young-old adult data (which is the primary age group used in most cognitive aging studies) to those of the old-old adults of the current investigation. However, because, to the best of our knowledge, there is only one age-related investigation of cue-related activity (Duarte et al., 2013), predictions concerning such brain activity were difficult to make. Friedman’s (2007) older adults did not appear to upregulate their attention when the contents of WM had to be updated. Although the task used in this study is quite different from the current paradigm, the Friedman (2007) result suggests that older adults in the current investigation, perhaps due to limited processing resources, might not be able to recruit the necessary resources to shift their attention internally and efficiently to the task-relevant digits in WM. Therefore, relative to young adults, the selection cue might not elicit, at parietal locations, larger P3b than the neutral-2 or neutral-4 cues. On the other hand, the cue-related results of Duarte et al., (2013), whose paradigm is much closer in design to that of the current study, imply that older adults might show an intact selection mechanism. This would be reflected in an enhanced P3b to the selection relative to the other cue conditions. Second, based on Oberauer’s (2001, 2005) behavioral and Duarte et al.’s ERP studies, we predicted that older adults would be able to removeno-longer-relevant information from the focus of attention. That is, the selection andneutral-2 cues at frontal sites (Yi & Friedman, 2011) should produce the same-magnitude waveforms, both of smaller amplitude than the neutral-4 cue. This result would indicate that the memory load was reduced to 2 items via the selection cue in similar fashion for all age groups.

At the probe stage, rejecting the intrusion probe involves inhibiting a pre-potent, incorrect motor response to a highly-familiar, but task-irrelevant item currently active in LTM. Therefore, if age-related prolongation of PI is due to a deficit in inhibitory control then, when contrasting the intrusion with the non-intrusion probe, we expected to observe similar-magnitude waveforms at fronto-central sites (Yi & Friedman, 2011) in the older relative to young adults (who should show a large difference between the two probe types). That is, the ERP difference between these two probe types should be smaller in the older relative to the young adults, which would presumably reflect a relative deficit in the resolution of PI. Moreover, based on the prediction that PI might be prolonged in older adults, a similar prolongation in the latency of the PI-related waveforms would also be expected. However, as discussed earlier, a deficit in context-content binding might also account for this pattern of results.

2. Material and Methods

2.1 Participants

Forty older adults (10 males; M age = 71; range 60–82) and twenty young adults (9 males; M age = 24; range 20–28) were recruited from the community in the vicinity of the Columbia University Medical Center through local newspaper and internet advertisements. The 40 older adults were divided into two age groups: young-old (range 60 – 70, five males) and old-old (range 71 – 82, five males) with 20 participants in each group. All participants were right handed, and compensated monetarily for their participation. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the study was approved by the New York State Psychiatric Institute’s Institutional Review Board.

2.2 Neuropsychological Assessments

Prior to entry into the study, participants were administered an extensive telephone screen which solicited information on their physical and mental health. All participants reported themselves to be in good physical and mental health and free from medications that could potentially affect the central nervous system. For the older adults, the verbatim telephone screens were then reviewed by a board-certified neurologist in order to assess these prospective older volunteers for the presence of neurodegenerative disorders, clinically detectable neurovascular disease, possible disturbances in gait, the presence of tremors or rheumatological disorders and the taking of medications that might interfere with central nervous system function. All of the participants included here passed this initial screen.

All participants were administered the Modified Mini-Mental Status examination (mMMS; Mayeux, Stern, Rosen, & Leventhal, 1981) and achieved a score within the normal range. IQ was obtained from the vocabulary and block-design subtest of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–III (WAIS-III; Wechsler, 1997) for the young participants and from the full WAIS-III for the older participants. Scores from the Beck Depression Inventory indicated that all participants were free from depression. The participants’ demographic information and neuropsychological measures are listed in Table 1. Except for age, significant between-group differences were not observed (ps> .10).

Table 1.

Mean (±SD) Demographic Characteristics and Neuropsychological Measures for the Young, Young-Old and Old-Old participants.

| Young (n = 20) |

Young-old (n = 20) |

Old-old (n = 20) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 24.2 (2.2) | 65.4 (3.0) | 76.6 (4.3) |

| SES | 49.5 (15.7) | 47.2 (16.9) | 42.4 (15.4) |

| Modified Mini-mental Status Exam | 55.5 (1.6) | 55.0 (1.6) | 54.3 (1.7) |

| Beck Depression Inventory | 2.4 (3.0) | 3.1 (3.8) | 3.4 (2.9) |

| Forward digit span | 7.6 (1.2) | 6.8 (1.4) | 6.9 (1.1) |

| Backward digit span | 6.1 (1.3) | 5.3 (1.4) | 5.3 (1.3) |

| Verbal IQ | 122.0 (11.5) | 116.9 (8.3) | 121.3 (7.7) |

| Performance IQ | 113.0 (13.3) | 113.5 (11.6) | 114.8 (10.2) |

2.3 Experimental Procedure

The digit WM (WM) recognition task was identical to that detailed in Yi and Friedman (2011). The paradigm is illustrated in Figure 1. Each trial started with a fixation cross of 500 ms duration and was followed by a memory-set display of four digits presented simultaneously in two columns for a duration of 500 ms. Two seconds after the disappearance of the digits, an arrow cue was presented for 1000 ms. Participants were required to focus on the digits indicated by the direction in which the arrow pointed. In the selection condition, the arrow pointed to the left or right and the participants needed to remember the two digits on the side to which the arrow pointed and ignore the two digits on the other side (Figure 1A). In the neutral-4 and neutral-2 conditions, the arrow was double headed, pointing to both directions, indicating that the participant needed to hold all of the digit sin WM (Figure 1B and 1C). In the neutral-4 condition, the initial digits were all different. In the neutral-2 condition, the left and right columns were comprised of the same digits. Following the disappearance of the arrow by 2000 ms, a probe digit appeared. The probe stayed on the screen for 2000 ms and participants had to decide whether this digit matched any of the task-relevant (i.e., cued) digits. Participants made a left-right, choice button-press decision using their left/right index finger. They were instructed to respond with an equal emphasis on accuracy and speed. The hands used to respond were counterbalanced across participants.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the experimental paradigm showing the selection (A), neutral-4 (B) and neutral-2 (C) conditions.

There were three probe types in the selection condition: the positive probe matched one of the to-be-remembered digits; the non-intrusion probe did not match any of the to-be-remembered digits (i.e., they were task-irrelevant); the intrusion probe matched one of the task-irrelevant digits that was to be ignored. Half of the probes were positive, while the remaining half were non-intrusion and intrusion probes, which were equiprobable. There were two probe types in the neutral-4 and neutral-2 conditions: positive and non-intrusion probes. The number of positive and non-intrusion probes was equal in both the neutral-4 and neutral-2 conditions. A variable delay period between 1000 and 1500 ms followed the presentation of the probe. In each block, there was a total of 16 trials with half comprised of the selection condition and one-quarter comprised of neutral-4 and neutral-2 conditions. The trials from the 3 conditions were intermixed randomly. To reduce the effect of trial history, the probe on a given trial could not match a digit from the immediately preceding trial.

2.4 Behavioral Data Analysis

The intrusion cost, which reflected PI, was defined as the RT difference between the intrusion and non-intrusion probe decisions. ANOVA was performed on the accuracy and RT data from the selection condition with the within-subjects factor of Probe type (non-intrusion, intrusion) and the between-subjects factor of Age Group (young, young-old, old-old). In addition, to assess the differences among the three cue conditions, a Cue type (selection, neutral-4 and neutral-2) X Age Group (young, young-old, old-old) ANOVA was performed on the accuracy and RT data associated with the positive probe. The Greenhouse-Geisser epsilon (ε) correction was used when appropriate, and uncorrected degrees of freedom and ε are reported. Partial eta squared ( ), a measure of effect size, is also reported. Bonferroni adjustment was applied separately for each set of post-hoc comparisons when there were more than two comparisons. For example, in the Cue Type ANOVA, the main effect is comprised of three levels, resulting in three post-hoc comparisons. Hence to reach significance at an alpha level of .05, each of the comparisons would have had to have been associated with a p-value of .017 (i.e., .05/3). Therefore, in the results below, all post-hoc comparisons are reliable at p <0.05 according to the Bonferroni adjustment. Thus, post-hoc p-values are not listed in the results below.

2.5 EEG Recording

The EEG was recorded continuously from electrodes (sintered Ag/AgCl) mounted in an Electro-cap, with 62 locations in accord with the extended 10–20 system (Sharbrough, et al., 1990). All sites were referenced to the nose tip and re-referenced off-line to averaged mastoids. EEG was recorded with a sampling rate of 500 Hz (DC; low-pass filter set at 100 Hz; right-forehead ground). Horizontal eye movements were recorded bipolarly from electrodes located at the outer canthi of the two eyes. Vertical eye movements were recorded bipolarly from electrodes placed above and below the left eye. Impedance of all electrodes was kept below 5kΩ.

2.6 ERP Data Analysis

Data from the cue and probe stages were epoched from 100 ms pre-cue until 1900 ms post-probe. Only correct trials were included in the averages. Eye movements were corrected offline (Semlitsch, Anderer, Schuster, & Presslich, 1986) and other artifacts were rejected manually. Channels with artifacts were interpolated on a trial-by-trial basis using a spherical spline algorithm (Perrin, Pernier, Bertrand, & Echallier, 1989). No more than four channels were interpolated for a given trial, otherwise the trial was rejected. Table 2 lists the mean number (and range) of trials included in the averages for each condition and age group.

Table 2.

Number (and range) of trials included in each condition of each Age Group

| Stage | Condition | Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Young | Young-old | Old-old | ||

| Cue | Neutral-2 | 101 (83–110) | 102 (68–112) | 104 (95–112) |

| Neutral-4 | 100 (84–108) | 101 (76–111) | 103 (92–111) | |

| Selection | 204 (181–222) | 202 (162–223) | 206 (173–222) | |

| Probe | Positive | 100 (60–110) | 102 (71–112) | 103 (85–110) |

| Non-intrusion | 51 (30–56) | 52 (33–56) | 53 (45–56) | |

| Intrusion | 49 (32–55) | 50 (39–56) | 49 (37–56) | |

To investigate potential age-related difference in the timing and magnitude of processes putatively related to selection and inhibition, five successive time windows were analyzed: 300–400, 400–500, 500–600, 600–700, 700–800 ms for both cue and probe stages. The mean amplitude of each time window was obtained for each cue/probe condition at pre-selected frontal or parietal electrode sites. These locations were chosen on the basis of the data from Yi and Friedman (2011), as well as where the effects were largest in the current data. Use of averaged voltages obviates the need for peak latencies and yields a way of assessing (although with relatively limited temporal resolution) the onset and duration of any age-related differences that might be present.

First, to assess within-group condition effects at the Cue stage, two-way ANOVAs were performed with the within-subjects factors of Cue Type (neutral-2, neutral-4, selection) and Electrode. As in Yi and Friedman (2011), cue-related activities were manifested at frontal and parietal sites. Hence, three frontal electrodes (F5, Fz, F6) and three parietal electrodes (P5, Pz, P6) were chosen for analysis. At the probe stage, two-way ANOVAs were performed with the within-subjects factors of Probe Type (positive, non-intrusion, intrusion) and Electrode. The most prominent activity was observed at fronto-central electrode locations with a left-sided focus. Hence, the data from Fz, Cz, F5, and C5 were analyzed. Second, to assess any age-related differences that might be present, ANOVAs with the between-subjects factor of Age Group (young, young-old, old-old), and the within-subjects factors of Cue or Probe Type and Electrode were performed on the averaged voltages.

To examine whether the topographic distributions elicited by the cue and probe differed among age groups and, therefore, may have engaged qualitatively dissimilar processes, two-way ANOVAs of Age Group (young, young-old, old-old) X Electrode (60 channels) were performed on the averaged voltages computed from the difference waveforms. Three difference waveforms were computed: two for the Cue Stage, selection vs. neutral-2, and selection vs. neutral-4; and one for the Probe Stage, intrusion vs. non-intrusion. The averaged amplitude of the first 100-ms time window where the amplitude difference was significant in each age group was subjected to ANOVA.

3. Results

3.1 Behavioral Data

The complete set of RT and accuracy data are presented, respectively, in Tables 3 and 4. Figure 2 shows the RT and accuracy data from the selection condition only.

Table 3.

Grand Mean RT Data (±SE) at the Probe Stage for each Age Group

| Cue | Probe | Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Young | Young-old | Old-old | ||

| Selection | Positive | 633 (22) | 843 (47) | 953 (42) |

| Non-intrusion | 662 (23) | 879 (41) | 958 (40) | |

| Intrusion | 764 (31) | 1097 (57) | 1178 (48) | |

| Neutral-2 | Positive | 633 (24) | 865 (45) | 945 (45) |

| Non-intrusion | 641 (25) | 849 (35) | 926 (42) | |

| Neutral-4 | Positive | 793 (36) | 1066 (55) | 1148 (56) |

| Non-intrusion | 737 (30) | 1006 (47) | 1080 (47) | |

Table 4.

Grand Mean accuracy data (±SE) at the Probe Stage for each Age Group

| Cue | Probe | Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Young | Young-old | Old-old | ||

| Selection | Positive | .97 (.008) | .97 (.007) | .96 (.010) |

| Non-intrusion | .98 (.004) | .99 (.003) | .98 (.007) | |

| Intrusion | .95 (.011) | .96 (.011) | .94 (.010) | |

| Neutral-2 | Positive | .97 (.012) | .98 (.008) | .98 (.006) |

| Non-intrusion | .98 (.008) | .99 (.004) | .99 (.004) | |

| Neutral-4 | Positive | .94 (.016) | .95 (.012) | .95 (.011) |

| Non-intrusion | .98 (.007) | .98 (.006) | .99 (.006) | |

Figure 2.

Grand-mean (±SE) RT (A), and accuracy (B) of the three groups to the positive, non-intrusion and intrusion probes in the selection condition.

Figure 2A depicts the grand-mean RTs to the three probe types following the selection cue. An Age Group X Probe Type (non-intrusion and intrusion) ANOVA was performed on the RT data. As expected, the effect of age was significant (F (2, 57) = 21.41, , p < .001). Post-hoc analysis showed that young adults responded faster than both young-old and old-old adults, whereas the difference between young-old and old-old adults was not significant. The main effect of Probe Type was significant (F (1, 57) = 225.39, ε = 1.00, , p < .001). Relative to the non-intrusion probe, RT was longer to the intrusion probe, revealing a robust PI effect. A one-way between-Age Group ANOVA on the RT measure of PI was significant (F (2, 59) = 10.60, , p < .001), and post hoc analysis indicated that the lowest-magnitude PI was observed in young adults (102 ms) compared to the two older-adult groups. The difference between young-old (218 ms) and old-old (220 ms) adults was not significant. To exclude the possibility that the longer PI observed in older adults was due to overall longer RTs in these two age groups (i.e., general slowing), a proportional index was computed. The RT index of PI was divided by the sum of the intrusion and non-intrusion probe RTs (i.e., Proportional PI = PI/(intrusion RT + non-intrusion RT)). The index for the young, young-old and old-old groups was, respectively, .07, .11 and .10. A one-way Age Group ANOVA on this index returned the same result as the original analysis (F (2, 59) = 4.57, , p < .05). Post hoc analysis indicated that the proportion was lower in the young adults than the two older-adult groups, while the difference between young-old and old-old adults was not significant.

To determine if the selection cue had the effect of reducing RT relative to the neutral-2 and neutral-4 conditions (see Table 3), a Cue Type (neutral-2, neutral-4, selection) X Age Group (young, young-old, old-old) ANOVA was performed on the RTs to the positive probe. The main effect of Cue Type was significant (F (2, 114) = 163.10, ε = .97, , p < .001). Post-hoc analysis revealed that positive probe RT in the neutral-4 condition was longer than those in the neutral-2 and selection conditions. The difference between the neutral-2 and selection conditions was not significant.

To determine if the selection cue had the effect of reducing the memory load to 2 items in similar fashion in the three age groups, the RT difference between the neutral 4 condition (which produced the longer RTs; Table 3) and the selection condition were calculated. These mean RT differences were 160 ms, 222 ms and 195 ms, respectively, for the young, young-old, and old-old groups. A one-way ANOVA on the RT differences showed that the effect of age group was not significant (F (2, 57) = 2.02, , p > .10). The RT reductions could have reflected the selection cue’s effect of reducing the memory load via selection of the 2 task-relevant digits. On this view, these data suggest that, given enough time, all three groups did equally well in removing the irrelevant subset of digits from the focus of attention.

Figure 2B depicts the percent accuracy in the selection condition to the three probe types in the three age groups. As can be seen, accuracy tended towards ceiling (> 94% in all conditions). An Age Group X Probe Type (non-intrusion, intrusion) ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of Probe Type (F (1, 57) = 44.98, ε = 1.00, , p < .001). Accuracy was lower to the intrusion than non-intrusion probe, indicating a robust PI effect. No other effects were significant (ps>.10).

To compare the selection with the two neutral conditions, a Cue Type X Age Group ANOVA was performed on accuracy to the positive probe. The main effect of Cue Type was significant (F (2, 114) = 12.65, ε = .93, , p < .001). Post-hoc analysis revealed that accuracy in the neutral-4 condition was lower than those in the selection and neutral-2 conditions, whereas the difference between the neutral-2 and selection conditions was not significant.

In sum, there was a robust PI effect: RT was longer and accuracy lower to the intrusion than non-intrusion probe in the selection condition. Importantly, as expected, accuracy was similar in the young and older-adult groups. Nevertheless, relative to young adults, a larger PI effect was observed in both young-old and old-old adults. RT was faster and accuracy was higher in the selection than in the neutral-4 condition but comparable to that in the neutral-2 condition, suggesting that the selection cue effectively reduced the memory load to 2 items in similar fashion for all age groups.

3.2 Cue-Locked ERP Data

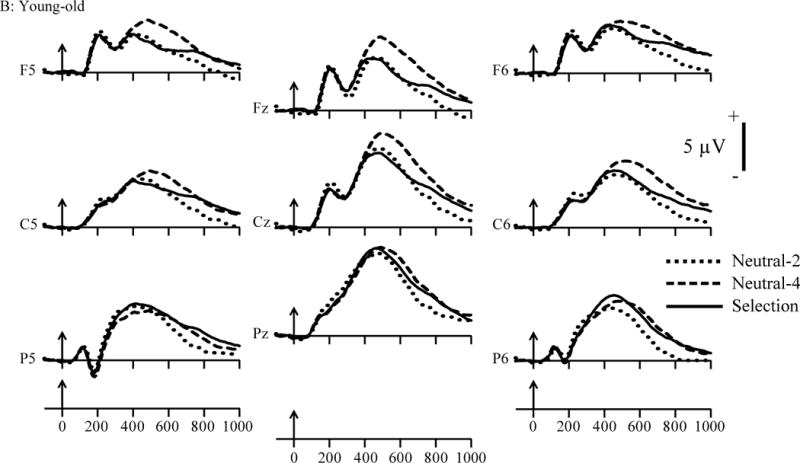

The cue-locked ERPs are plotted in Figure 3 A–C. All three cue types appear to elicit a P3 component (i.e., P3b; Donchin & Coles, 1988; Sutton, et al., 1965), which is maximal over parietal scalp. These data exhibit two different patterns: At parietal locations, the positivity elicited by the selection cue is larger than that associated with the neutral-2 cue. Because these 2 conditions have the identical memory load, the difference between them suggests that the larger positivity reflects processes involved in selection of the relevant digits. At frontal scalp, compared to the neutral-4 cue, the selection cue is more negative-going (or less positive). This suggests that an overlapping negative-going activity superimposed on the P3 to the selection cue might be responsible for the amplitude reduction (see also Yi & Friedman, 2011). Note also that, at frontal sites, the neural activity elicited by the neutral-2 and selection cues do not appear to differ in magnitude, in accord with their identical memory load of 2 items.

Figure 3.

Grand-mean waveforms (averaged across the 20 participants in each age group) at selected electrode sites elicited by the cue in the selection, neutral-2, and neutral-4 conditions. Vertical arrows mark stimulus onset. (A) young adult group; (B) young-old group; (C) old-old group.

3.2.1 Within-Group analyses

As noted in the methods, two-way, Cue Type (selection, neutral-2, neutral-4) X Electrode ANOVAs() were performed on the averaged amplitudes of each 100 ms time window at frontal and parietal locations in each age group. Table 5 lists the Cue Type main effect F-values. To elucidate cue-related differences, pairwise comparisons were performed between the selection and neutral-2 cues at parietal sites, as this difference should reflect the shifting of attention to the task-relevant information (Yi & Friedman, 2011).

Table 5.

F-ratios from the within-group Cue Type ANOVAs (df = 2, 38)

| Time | Parietal electrodes

|

Frontal electrodes

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young | Young-old | Old-old | Young | Young-old | Old-old | |

| 300–400 ms | 13.36*** | 2.62 | 9.46*** | 3.56* | 3.14 | 2.90 |

| 400–500 ms | 13.48*** | 0.74 | 10.86*** | 5.87* | 7.86** | 1.32 |

| 500–600 ms | 18.75*** | 2.61 | 9.50*** | 5.61** | 11.39*** | 7.51** |

| 600–700 ms | 23.61*** | 4.71* | 6.08** | 7.56** | 11.89*** | 10.82*** |

| 700–800 ms | 13.74*** | 4.68* | 4.48* | 7.02** | 9.25*** | 6.59** |

Notes. The asterisks following the F-value in the table indicate the significance level of the Cue Type main effect:

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001.

Accordingly, at parietal electrodes, the main effect of Cue Type revealed, as indicated by follow-up, pairwise comparisons, that the selection cue was more positive than the neutral-2 cue between 300 and 800 ms in the young adults, and between 400 and 700 ms in the old-old adults. For young-old adults, although the difference between the selection and neutral-2 cue was not significant in any time window, the Cue Type X Electrode interactions were significant between 300 and 600 ms (ps< .05). To parse the interactions, Cue Type subsidiary ANOVAs were performed. The Cue Type main effect combined with pairwise comparisons revealed that the selection cue was more positive than the neutral-2 cue between 500 and 600 ms at P6.

Difference waveforms (selection – neutral-2) were computed to isolate the effect of selection from that of memory load. Figure 4A depicts the scalp distributions based on the difference waveforms. As seen in the figure, the difference has a focus at parietal locations in all three age groups. The maps denoted by asterisks (*) indicate that the amplitude difference between the selection and neutral-2 cues is significant.

Figure 4.

Spline-interpolated topographic maps based on the averaged reference computed on the difference waveforms for the selected time windows. The maps denoted by asterisks (*) indicate the time windows where reliable differences were obtained. Shaded regions = negativity; unshaded regions = positivity. (A) Selection cue minus neutral-2 cue; (B) Selection cue minus neutral-4 cue.

At frontal scalp sites, because the neutral-2 and selection cue ERPs should reflect the same memory load (i.e., 2), but differ from the neutral-4 cue with a memory load of 4, all three cue types were compared. Hence, in the ANOVA at frontal sites, the Cue Type main effect combined with pairwise comparisons revealed that the amplitudes of the neutral-2 and selection cue, which did not differ, were more negative-going (or less positive) than the neutral-4 cue. This difference was significant from 400–500 ms in the young adults, and from 500–800 ms in the young-old and old-old adults.

To isolate the effect of memory load reduction, difference waveforms were computed by subtracting the ERPs to the neutral-4 from those to the selection cue. As observed in Figure 4B, the scalp distributions based on the difference ERPs has a negative focus at frontal sites in all three groups. The maps denoted by asterisks (*) indicate that the amplitude difference between the selection and neutral-4 cues is significant.

3.2.2. Between-Group Analyses

To examine age-related differences, three-way ANOVAs (Age Group X Cue Type [selection, neutral-2, neutral-4] X Electrode) were performed on the averaged amplitudes of each 100 ms time window, separately at frontal and parietal locations. Only interactions with Age Group are of interest here, so main effects of Age Group are not reported. At parietal electrodes, the three way interaction was not significant for any time window (ps> .10). However, the Cue Type X Age Group interaction was significant for all time windows (ps< .05), suggesting that the effect of Cue Type differed among Age Groups. As shown in Table 5, the main effect of Cue Type was significant between 300 and 600 ms in the young and old-old adults but not in the young-old adults (see 3.2.1, within-group analyses above for details). Between 600 and 800 ms, the main effect of Cue Type was significant for all age groups. Pairwise comparisons indicated that the selection cue was more positive than the neutral-2 cue between 600 and 800 ms in the young and old-old adults but not in the young-old adults (see Figure 4A and 3.2.1 within-groups analyses above).

At frontal locations, the Age Group X Cue Type X Electrode interaction was significant between 300 and 400 and 500 and 800 ms (ps< .05). As observed in Table 5, the main effect of Cue Type was significant in the young group between 300 and 400 ms. This was not the case in the young-old or old-old groups. Pairwise comparisons showed that the interaction between 500 and 800 ms was due to two different patterns: 1) theneutral-4 cue was more positive than the neutral-2 cue between 500 and 800 ms in all age groups; and 2) the neutral-4 cue was more positive than the selection cue between 500 and 800 ms in young-old and old-old groups, but not in the young.

The analysis of cue-locked topographic differences among age groups (selection minus neutral-2 cue; selection minus neutral-4 cue) did not reveal reliable Age Group X Electrode interactions (Fs (118, 3336) < 1, ps>0.10), indicating that the cue-related scalp distributions did not differ among age groups, as is evident in Figure 4A and B.

To summarize the within- and between-group analyses, at parietal sites, the selection cue elicited larger positive amplitude than the neutral-2 cue in all three age groups. However, this effect occurred, relative to the young, at longer latencies in the young-old and old-old. At frontal sites, the amplitudes to the selection and neutral-2 cues did not differ significantly suggesting, in accord with the behavioral data, that the selection cue had the effect of reducing the memory load to two items. At frontal loci, compared to the neutral-4 cue, the selection cue elicited a more negative-going waveform in all age groups although, relative to the young and young-old, the old-old group exhibited this effect at a longer-latency. Taken as a whole, these data suggest a dissociation between the ERPs at frontal and parietal regions. Putative memory-selection processes may be reflected by the enhanced positivity to the selection relative to the neutral-2 cue at parietal scalp. The presumed removal of no-longer-relevant information from the focus of attention might be reflected by the negative-going amplitude of the selection- relative to the neutral-4 cue at frontal locations. The processes reflected in these effects appear to be similar in the three age groups, as between-age group scalp distribution differences were not observed.

3.3 Probe-Locked ERP Results

The grand-mean averages elicited by the three probes in the selection condition are shown in Figure 5 for the three age groups. Like the cue-locked data, each of the three probes appears to elicit a P3 or P3b component, which has a focus at parietal scalp. At fronto-central scalp sites, the P3b to the intrusion probe is more negative-going (or less positive) than that to the non-intrusion probe.

Figure 5.

Grand-mean waveforms (averaged across the 20 participants in each age group) at selected electrode sites elicited by the positive, non-intrusion and intrusion probes in the selection condition. Vertical arrows mark stimulus onset. (A) young adults (B) young-old adults (C) old-old adults.

3.3.1. Within-Group Analyses

To assess probe-locked differences, two-way Probe-Type (positive, non-intrusion, intrusion) X Electrode (Fz, Cz, F5, C5) ANOVAs were performed on the averaged amplitudes in each time window. Of primary interest in these ANOVAs is the comparison between the intrusion and non-intrusion probes, as this difference should reflect the resolution of PI.

Table 6 lists the Probe-Type main effect F-values. To elucidate differences among Probe Types, pairwise comparisons were performed. The main effect of Probe Type combined with pairwise comparisons showed that the intrusion probe was more negative-going than the non-intrusion probe between 400 and 600 ms in the young adults, and between 500 and 700 ms in both young-old and old-old adults.

Table 6.

F-ratios from the within-group Probe Type ANOVAs (df = 2, 38)

| Time | Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Young | Young-old | Old-old | |

| 300–400 ms | 41.17*** | 0.00 | 0.84 |

| 400–500 ms | 29.95*** | 1.60 | 2.09 |

| 500–600 ms | 5.51* | 11.83*** | 8.22** |

| 600–700 ms | 0.97 | 14.15*** | 8.25** |

| 700–800 ms | 1.44 | 10.49*** | 4.82* |

Notes. The asterisks following the F-value in the table indicate the significance level of the Probe Type main effect:

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001.

To isolate the effect of PI, difference waveforms were computed by subtracting the ERPs to the non-intrusion from those to the intrusion probe. As can be seen in Figure 6, the topographic maps show a negative focus over left fronto-central scalp sites. The maps denoted by asterisks (*) indicate that the amplitude difference between the intrusion and non-intrusion probes is significant.

Figure 6.

Spline-interpolated topographic maps based on the averaged reference computed on the difference waveforms (intrusion minus non-intrusion probe) for the selected time windows. The maps denoted by asterisks (*) indicate the time windows where reliable differences were obtained. Shaded regions = negativity; unshaded regions = positivity.

3.3.2. Between-Group Analyses

To examine age-related differences, three-way ANOVAs (Age Group X Probe Type X Electrode) were performed. The three way interaction was not significant for any time window (ps> .05). However, the Probe Type X Age Group interaction was significant between 300 and 500 ms and 600 and 800 ms (ps< .01), suggesting that the effect of Probe Type differed among Age Groups. Between 300 and 500 ms, the Probe Type effect (intrusion more negative-going than non-intrusion) was significant in the young adults but not in the young-old or old-old adults. Between 600 and 800 ms, by contrast, the Probe Type effect was observed in the young-old and old-old, but not in the young (See Table 6 and 3.3.1).

The analysis of probe-locked topographic differences among age groups (non-intrusion – intrusion probe) did not reveal a reliable Age Group X Electrode interaction (Fs (118, 3336) < 1, Ps >0.10), indicating that the probe-related scalp distributions did not differ among age groups.

To summarize the probe-locked data, the distinction between the intrusion and non-intrusion probes occurred, relative to the young, later in the young-old and old-old adults. The lack of topographic differences among age groups suggests that the negative difference between the intrusion and non-intrusion probes might reflect the same set of processes in all three age groups, that is, the resolution of proactive interference.

4. Discussion

To reiterate briefly, the purpose of this study was to investigate, using the embedded-processes model as a template, how the timing of the processes comprising cue-related memory selection and removal, and probe-related inhibition and PI resolution differ across the older portion of the age span. At the cue stage, we investigated the processes involved in the shifting of attention to items in WM and removing no-longer-relevant information from the focus of attention. At the probe stage, the processes implicated in rejecting the highly familiar, but no-longer relevant intrusion probe were assessed. To accomplish these goals, we used behavioral as well as ERP techniques. Three groups of participants were compared: young, young-old and old-old. Relative to the young, in line with one of our predictions, PI magnitude was larger in both young-old and old-old participants. At the cue stage, the selection cue elicited a larger parietal P3 than the neutral-2 cue, suggesting that this activity reflected processes instrumental in the selection of task-relevant information in all three age groups. Compared to young participants, this differential activity was delayed in both young-old and old-old participants. We also observed over frontal sites, in accord with expectation, greater negative-going (or less positive) activity to the selection than neutral-4 cue, presumably indicating that this activity reflected processes engaged in removing the irrelevant digits from the focus of attention. Compared to young and young-old participants, the latency of this differential activity was delayed in old-old participants.

Also consistent with prediction, at the probe stage the intrusion probe elicited more negative-going (less positive) activity at fronto-central sites than the non-intrusion probe, suggesting that this difference may reflect processes recruited to enable the resolution of PI induced by the intrusion probe (Du, et al., 2008; Tays, et al., 2009; Yi & Friedman, 2011; Zhang, et al., 2010). This differential activity was again prolonged, relative to the young, in the two older age groups. Nonetheless, the scalp topographies of the cue- and probe- locked difference waveforms did not differ among age groups, suggesting an age-related similarity in the processes reflected by these brain activities. We discuss these findings in more detail in the following sections.

4.1 Behavioral Data

In all three groups, the RT to the positive probe in the selection-cue condition did not differ from that in the neutral-2 cue condition while, relative to these two conditions, RTs in the neutral-4 condition were reliably prolonged and no significant age differences in these effects were obtained. This suggests that the memory load was reduced to two in the selection condition and that older adults can successfully remove no-longer-relevant information from the focus of attention. This result is consistent with previous findings (Duarte, et al., 2013; Oberauer, 2001, 2005). Nonetheless, as suggested in previous behavioral studies, no-longer-relevant information, although putatively removed from the focus of attention, was still in the active portion of LTM as demonstrated by reliable PI effects in all three groups (Oberauer, 2001; Yi, et al., 2009). Moreover, both young-old and old-old adults showed greater PI relative to the young.

On presentation of the intrusion probe, participants would have had to reject the task-irrelevant, but highly-familiar probe. Hence, one explanation of the prolonged PI in older adults could be that, for example, due to compromised inhibitory function (Hasher & Zacks, 1988), older, relative to young, adults might require a longer time period to inhibit an incorrect response to the irrelevant intrusion probe. Therefore, the lack of a difference in PI magnitude between the two older groups could be interpreted to mean that inhibitory functions may not necessarily decline in the oldest old. In support of this claim, Robert, et al., (2009) compared children (10 – 12 years old), young (19–24 years old), young-old (60 - 69 years old) and old-old participants (70 - 88 years old) in a reading span task. In this task, participants were required to read 2 to 5 sentences and make a judgment as to whether each sentence was semantically correct or not. At the same time, participants had to maintain the last words of the sentences in WM and, following a delay, recall the last word of each sentence. In this task, participants might recall the last word from a previously-presented, but now irrelevant set of sentences, or a word that was in the relevant sentence, but was not the last word. As in the current study, these were labeled intrusion errors. Intrusion errors like these were greater in young-old than in young participants, but were equivalent to those of the old-old. Moreover, other studies have also observed that some aspects of presumed inhibitory function may not decline further, relative to the young-old, in old-old adults (Bisiacchi, Borella, Bergamaschi, Carretti, & Mondini, 2008; Spieler, Balota, & Faust, 1996).

Alternatively, it could be argued that the larger-magnitude PI in older adults might be due to a general slowing mechanism (Salthouse, 1996). This is less likely to be the case, however, as the significance of the age-related PI effect survived after a proportional index was computed, which ruled out the possibility that overall age-related differences in RT level could have influenced the age-related differences in the PI measure.

Rather than an inhibitory deficit, an alternative account posits that older adults exhibit difficulty in context-content binding (Oberauer, 2005). That is, on this view, a deficit in binding the relevant item with its context (i.e. the left- or right-sided location of the item) could also account for the increased PI in the older adults. Oberauer (2005) has suggested that, to respond correctly (i.e., “No”) to an intrusion probe (the representation of which is resident in the activated portion of LTM), one must overcome the high familiarity signal it engenders by recollecting the context in which that probe previously occurred (in this case in the irrelevant memory set, whose context is either the left or right side of the memory-set display). The processes involved in recollection are more robust than those of familiarity, but take longer to transpire (McElree, Dolan, & Jacoby, 1999). Hence, by this account, the prolongation of PI in older adults might be due to a deficit in or prolongation of recollective processing rather than a deficit in inhibitory processing. This explanation would be consistent with a fairly large literature that suggests an age-related deficit in recollection-based processes, but a relative sparing of familiarity-based processes (see Friedman, Nessler, & Johnson, 2007 for a review; see also Hay & Jacoby, 1999).

4.2 ERP Data: The selection stage

The selection cue could have initiated processes comprised of the selection of task-relevant items and the removal of the no-longer-relevant digits from the focus of attention. These two sets of processes were presumably reflected in, respectively, a parietally-based activity (selection positivity) that was more positive to the selection than the neutral-2 cue, and a frontally-based activity that was more negative-going to the selection than the neutral-4 cue.

The memory load was the same following the selection and the neutral-2 cues. Hence, the difference between these two cue conditions could not have been due to a difference in memory load. Rather, the greater amplitude elicited by the selection relative to the neutral-2 cue at parietal electrodes likely reflects the internal shifting of attention to the task-relevant information (Yi & Friedman, 2011). This possibility is supported, in part, by the results of previous WM-updating tasks. For example, Kiss and colleague (Kiss, et al., 1998; Kiss, et al., 2007; see also, Friedman, 2007) showed that, relative to a condition in which updating was unnecessary, a greater-magnitude P3b component was elicited when information had to be updated and brought into the focus of attention. Additionally, Yi et al. (2009), in an fMRI investigation, found a negative correlation between selection-related activity in the posterior parietal cortex and the magnitude of the reduction in the RT measure of PI. On the basis of this relation, they suggested that it was the internal shifting of attention to the relevant information that contributed to the reduction of PI to the no-longer-relevant information delivered at the probe stage (Yi, et al., 2009).

In both the selection and neutral-4 conditions, participants had to hold 4 items in WM prior to the cue. However, following the cue in the selection condition, subjects would have had to hold only 2 items in WM, whereas following the neutral-4 cue they would have had to maintain all 4 items in WM. Therefore, the negative-going difference at frontal locations between the selection and neutral-4 cues might have isolated processes involved in the removal of the no-longer-relevant information and, hence, in the reduction of the memory load to two items. In other words, in the selection condition, only two items had to be maintained in WM and, at frontal sites, the magnitude of brain activity to the selection cue was similar to that of the neutral-2 cue, but smaller than that to the neutral-4 cue in all three age groups (i.e., in the condition with the greatest memory load). This latter result is consistent with the RT finding that the no-longer-relevant information was removed from the focus of attention. Furthermore, the memory-load interpretation of the reduction in the frontally-oriented P3 waveform receives support from a study by Shucard and colleagues (Shucard, Tekok-Kilic, Shiels, & Shucard, 2009). In this investigation, participants had to either remember letters or the locations of the letters. Set-size was either 1 or 3 items. Shucard et al. (2009) found that the amplitude of the P3 at frontal sites became larger as more items had to be held within the focus of attention in WM.

Although Friedman (2007) has suggested that older adults, due to limited processing resources, may not be efficient in shifting their attention internally and removing the task-irrelevant digits from the focus of attention, this was not observed in the current study. Rather, older adults exhibited the same amplitude enhancement to the selection relative to the neutral-2 cue at parietal sites and the same magnitude reduction in frontally-based activity to the selection relative to the neutral-4 cue. This pattern of findings indicates that older adults were quite able to select task-relevant information and remove the no-longer relevant items from the focus of attention. On the other hand, as age increased, the cue-locked activities were prolonged in old-old adults compared to the young and young-old age groups, indicating that it took longer for these individuals to remove no-longer-relevant information from the focus of attention. The prolonged cue-locked activity is consistent with findings from a recent ERP study by Jost and colleagues (Jost, Bryck, Vogel, & Mayr, 2011). In two conditions of this investigation, participants were instructed to remember one of three color bars (surrounded by two distractors) presented to one hemisphere or to remember all three color bars (with no distractors) presented to the same hemisphere. The authors first calculated the CDA to measure the amount of information held in WM (Vogel & Machizawa, 2004). Then the authors subtracted these two difference waveforms (i.e., the ERP elicited by one item with distractors was subtracted from the ERP elicited by all three items without distractors). According to the authors, this double subtraction yielded a waveform that reflected the timing of the removal of the two to-be-ignored items from WM. In other words, the difference waveform presumably reflected the processes involved in filtering task-irrelevant items out of visual WM. Consistent with the age-related delay in cue-locked activity observed here, older, relative to, younger adults in the Jost et al. (2011) study showed delays in this filtering activity.

4.3 ERP Data: The probe stage

At this stage, participants would have had to reject the highly-familiar, but no-longer-relevant digit. A fronto-central negative-going activity was observed when contrasting the ERPs elicited by the intrusion and non-intrusion probes. As noted earlier, a similar, frontally-distributed negativity has also been observed in other paradigms that required the rejection of a no-longer-relevant, though familiar item (Du, et al., 2008;Tays, et al., 2009; Zhang, et al., 2010). In the current study, the presence of a significant PI effect indicated that the no-longer-relevant information was still in the activated portion of LTM. Hence, to respond correctly, participants would have to inhibit an inappropriate motor response engendered by the highly familiar but no-longer-relevant intrusion probe. That is, the high familiarity of the intrusion probe would have induced a potent tendency to produce a “Yes” response which had to be overridden in order to generate a correct “No” decision. By contrast with prediction, older adults displayed a highly-similar difference between the intrusion and non-intrusion probes to that of the young adults. Nevertheless, this fronto-central differential activity was delayed in the older adults, consistent with the behavioral finding that PI was prolonged in these participants.

As noted earlier, a prolongation or deficit in recollection-based processes could have led to the older adults’ prolonged PI (i.e. Oberauer, 2005). However, we have no direct ERP evidence of this. That is, in episodic-recognition memory (EM) paradigms, the ERPs to previously viewed items (i.e., old) can be compared with those elicited by previously unseen items (i.e., new) and a parietally-focused EM effect, which reflects the recollective aspect of EM, can be computed (see Friedman & Johnson, 2000 for a review; see also Vilberg, Moosavi, & Rugg, 2006). No such comparison is possible here. Future WM experiments in which the design affords this type of comparison might aid in disentangling recollection- and inhibition-based accounts of PI in WM experiments of the kind described here.

Similarly, the current ERP and behavioral data are silent with respect to the context-content binding and inhibition-deficit accounts of age-related differences in WM. Nonetheless, no matter which explanation turns out to be correct, the current samples of young-old and old-old adults do not appear to exhibit profound deficits in the processes that underpin performance in this particular task.

5. Conclusions

Young and older adults appeared to engage similar cognitive processes when selecting task-relevant information and removing no-longer relevant information at the cue stage, and presumably inhibiting task-irrelevant information at the probe stage. Nonetheless, these activities were all delayed in older adults. In all three groups, the cue-locked selection positivity at parietal sites might reflect the internal shifting of attention to task-relevant information. The negative-going activity at frontal sites to the selection relative to the neutral-4 cue might reflect removal of no-longer-relevant information from within the focus of attention, and, therefore, the reduction of the memory load to two items. At the probe stage, processes reflected by the negative-going activity to the intrusion relative to the non-intrusion probe likely involve the resolution of PI engendered by the no-longer-relevant intrusion probe. On the whole, and to the extent that these brain activities reflect the processes we have suggested, our findings indicate that selection- and removal-related processes recruited by the current task do not differ dramatically with age but, as one ages, take longer to unfold. By contrast, the prolongation of PI and the associated waveforms do suggest a relative age-related impairment in inhibition-related processes initiated by the probe.

Acknowledgments

The present work was supported by Grant #AG005213 from the NIA and the New York State Department of Mental Hygiene. We thank Timothy Martin, Julianna Kulik and Jenny Chen for assistance with data collection. We thank Mr. Charles Brown, III for his help in the programming of the experiment. We are also grateful to all the participants who volunteered for this study.

References

- Arbuckle TY, Gold DP. Aging, inhibition, and verbosity. The Journals of Gerontology. 1993;48:P225–232. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.5.p225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley AD. Working memory. New York, NY, US: Clarendon Press/Oxford University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley AD. Exploring the central executive. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Experimental Psychology. 1996;49A:5–28. [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley AD, Hitch GJ. Working Memory. In: Bower GH, editor. The psychology of learning and motivation. Vol. 8. New York: Academic Press; 1974. pp. 47–89. [Google Scholar]

- Bisiacchi PS, Borella E, Bergamaschi S, Carretti B, Mondini S. Interplay between memory and executive functions in normal and pathological aging. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2008;30:723–733. doi: 10.1080/13803390701689587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borella E, Carretti B, De Beni R. Working memory and inhibition across the adult life-span. Acta Psychologica (Amst) 2008;128:33–44. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan N. An Embedded-Processes Model of working memory. In: Miyake A, Shah P, editors. Models of working memory: Mechanisms of active maintenance and executive control. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1999. pp. 62–101. [Google Scholar]

- De Beni R, Palladino P. Decline in working memory updating through ageing: intrusion error analyses. Memory. 2004;12:75–89. doi: 10.1080/09658210244000568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donchin E, Coles MGH. Is the P300 Component a Manifestation of Context Updating. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1988;11:357–374. [Google Scholar]

- Du Y, Xiao Z, Song Y, Fan S, Wu R, Zhang JX. An electrophysiological signature for proactive interference resolution in working memory. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2008;69:107–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte A, Hearons P, Jiang Y, Delvin MC, Newsome RN, Verhaeghen P. Retrospective attention enhances visual working memory in the young but not the old: an ERP study. Psychophysiology. 2013;50:465–476. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein JR, Van Petten C. Influence of cognitive control and mismatch on the N2 component of the ERP: a review. Psychophysiology. 2008;45:152–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00602.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman D. A Neurocognitive Overview of Aging Phenomena Based on the Event-Related Brain Potential (ERP) In: Stern Y, editor. Cognitive reserve: Theory and applications. Philadelphia, PA: Taylor & Francis; 2007. pp. 285–304. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman D, Johnson R., Jr Event-related potential (ERP) studies of memory encoding and retrieval: a selective review. Microscopy Research and Technique. 2000;51:6–28. doi: 10.1002/1097-0029(20001001)51:1<6::AID-JEMT2>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman D, Nessler D, Johnson R., Jr Memory encoding and retrieval in the aging brain. Clinical, EEG and Neuroscience. 2007;38:2–7. doi: 10.1177/155005940703800105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold DP, Arbuckle TY. A longitudinal study of Off-Target Verbosity. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B Psychological Science and Social Science. 1995;50:P307–315. doi: 10.1093/geronb/50b.6.p307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasher L, Zacks RT. Working memory, comprehension, and aging: A review and a new view. In: Bower GH, editor. Psychology of learning and motivation: Advances in research and theory. Vol. 22. San Diego: Academic Press; 1988. pp. 193–225. [Google Scholar]

- Hay JF, Jacoby LL. Separating habit and recollection in young and older adults: effects of elaborative processing and distinctiveness. Psychology and Aging. 1999;14:122–134. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.14.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jost K, Bryck RL, Vogel EK, Mayr U. Are old adults just like low working memory young adults? Filtering efficiency and age differences in visual working memory. Cerebral Cortex. 2011;21:1147–1154. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss I, Pisio C, Francois A, Schopflocher D. Central executive function in working memory: event-related brain potential studies. Cognitive Brain Research. 1998;6:235–247. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(97)00035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss I, Watter S, Heisz JJ, Shedden JM. Control processes in verbal working memory: an event-related potential study. Brain Research. 2007;1172:67–81. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.06.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayeux R, Stern Y, Rosen J, Leventhal J. Depression, intellectual impairment, and Parkinson disease. Neurology. 1981;31:645–650. doi: 10.1212/wnl.31.6.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElree B, Dolan PO, Jacoby LL. Isolating the contributions of familiarity and source information to item recognition: a time course analysis. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning Memory and Cognition. 1999;25:563–582. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.25.3.563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman S, Kemper S, Kynette D, Cheung HT, Anagnopoulos C. Syntactic complexity and adults’ running memory span. The Journals of Gerontology. 1991;46:P346–351. doi: 10.1093/geronj/46.6.p346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberauer K. Removing irrelevant information from working memory: a cognitive aging study with the modified Sternberg task. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning Memory and Cognition. 2001;27:948–957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberauer K. Binding and inhibition in working memory: individual and age differences in short-term recognition. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2005;134:368–387. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.134.3.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin F, Pernier J, Bertrand O, Echallier JF. Spherical splines for scalp potential and current density mapping. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 1989;72:184–187. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(89)90180-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persad CC, Abeles N, Zacks RT, Denburg NL. Inhibitory changes after age 60 and their relationship to measures of attention and memory. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B Psychological Science and Social Science. 2002;57:P223–232. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.3.p223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert C, Borella E, Fagot D, Lecerf T, de Ribaupierre A. Working memory and inhibitory control across the life span: Intrusion errors in the Reading Span Test. Memory & Cognition. 2009;37:336–345. doi: 10.3758/MC.37.3.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA. The processing-speed theory of adult age differences in cognition. Psychological Review. 1996;103:403–428. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.103.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semlitsch HV, Anderer P, Schuster P, Presslich O. A solution for reliable and valid reduction of ocular artifacts, applied to the P300 ERP. Psychophysiology. 1986;23:695–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1986.tb00696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharbrough F, Chatrian GE, Lesser RP, Lüders H, Nuwer M, Picton TW. Guidelines for standard electrode position nomenclature. Bloomfield, IL: American EEG Society; 1990. [Google Scholar]