Abstract

Background:

Inadequate bowel preparation prior to colonoscopy compromises the medical value of the procedure. The aim of this study is to explore the factors associated with pre-colonoscopy sub-optimal bowel preparation from the perspective of the physician.

Methods:

Using a cross-sectional study design, we examined the role of various factors thought to be associated with sub-optimal bowel preparation as reported by a sample of practicing Gastroenterologists across the United States. We conducted a survey among active members of the American College of Gastroenterology to assess Gastroenterologists’ perceptions about barriers faced by the patients in the bowel preparation process. Descriptions of factors associated with sub-optimal bowel preparation prior to screening colonoscopy were identified and described, including health conditions, patient cognitive/behavioral characteristics and medication use.

Results:

Health conditions (including constipation and diabetes) and particular patient characteristics (including older age) were the most common perceived determinants of sub-optimal bowel preparation. Although some barriers to colonoscopy preparation (e.g., older age), cannot be modified, many are amenable to change through education.

Conclusions:

This study indicates the potential value of a personalized approach to bowel preparation, which addresses the specific needs of an individual patient like chronic constipation and diabetes and those with poor literacy skills or poor fluency in English. Development and evaluation of educational interventions to address these factors warrants investment.

Keywords: Bowel preparation, colonoscopy, colon cancer prevention

INTRODUCTION

The quality of bowel preparation prior to colonoscopy facilitates clear visualization of the colon, cecal intubation and the detection of adenomas and neoplasia-key factors directly impacting the effectiveness of colonoscopy.[1] Reported in as many as one-third of all colonoscopies,[2] sub-optimal bowel preparation can lead to missed lesions,[3] shortened surveillance intervals,[4] increased screening costs[5] and may expose patients to increased risk and further inconvenience associated with repeat procedures.

To minimize the incidence of sub-optimal preparation, numerous strategies have been employed, including the use of alternative preparations, varying volumes of polyethylene glycol, use of split dosing and low residue diet.[6] Despite the availability of an array of bowel cleansing methods, preparation regimens are often adopted broadly in a “one size fits all” approach. Research on predictors of sub-optimal bowel preparation indicates that factors related to the patient, the physician and the procedure all influence preparation quality.[7] Factors at the individual level that have been reported include having lower educational attainment, being unmarried, Medicaid insurance coverage, certain comorbidities, antidepressant use, inability to ingest the full volume of purgative and failure to properly follow instructions.[7,8] Physician practice type and time of the procedure, use of split dosing and type of purgative also contribute to the quality of the bowel preparation.[9,10,11] These studies, however, tend to be conducted within single centers with results that vary widely, producing no clear consensus on the determinants of suboptimal bowel preparation.

The purpose of this study was to examine the role of various factors thought to be associated with sub-optimal bowel preparation as reported by a sample of practicing Gastroenterologists across the US. This study received approval from the Institutional Review Boards at Columbia University and William Paterson University.

METHODS

We conducted a survey among active members of the American College of Gastroenterology in the United States. As previously described[4] a complete list of members was provided by the American College of Gastroenterology (n = 10,228). From this list, we excluded inactive members and all members who were not an MD or DO, who were retired, or who had a specialty that did not include conducting screening colonoscopies in adult populations in their scope of work. Of the remaining 6,777 active members, about 20% probability sample was selected. Due to the large sample size and financial restrictions, it was not feasible to survey all members of the American College of Gastroenterology, therefore a random sample was selected to represent the larger group. The choice of 20% was based on the number of total possible participants and the time and resources available. As reported by Rothman and Greenland,[12] the advantage of randomization is that it creates a study group with a balanced and representative distribution of the factors under consideration. Randomization, thus, quantitatively accounts for potential confounders that are frequently associated with alternative sample selection techniques. Randomization was performed using the random sample generator function of IBM SPSS version 19 statistical software (IBM Corp. Released 2010. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 19.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Of the 1354 members in our random sample, an additional 355 did not meet the eligibility criteria, were deceased, could not be located, or had retired from practice. Of the remaining eligible members (n = 999) in our sample who received surveys, 288 responded.

Data were collected between September 2010 and March 2011. Surveys were sent to all eligible participants, first by E-mail with two follow-up emails at 2-week intervals for non-respondents. If there was still no response, hard copies of the survey were sent via postal mail delivered with a self-addressed stamped envelope.

The main focus of the survey was to assess Gastroenterologists’ perceptions about barriers faced by patients in the bowel preparation process. An open-ended question was used to assess respondents’ descriptions of factors associated with sub-optimal bowel preparation prior to screening colonoscopy among average risk adults, aged 50 years and older: How would you characterize persons who are most likely to have suboptimal (fair, poor or inadequate) bowel preparations? All the results were coded into categories based on the most frequently reported factors that gastroenterologists indicated were related to sub-optimal bowel preparation among their patients. One coder (CHB) categorized responses and then blindly coded them again with 100% similarity. A second coder (GCH) took a random sample of 50 responses and coded them with 100% similarity to the first coder.

RESULTS

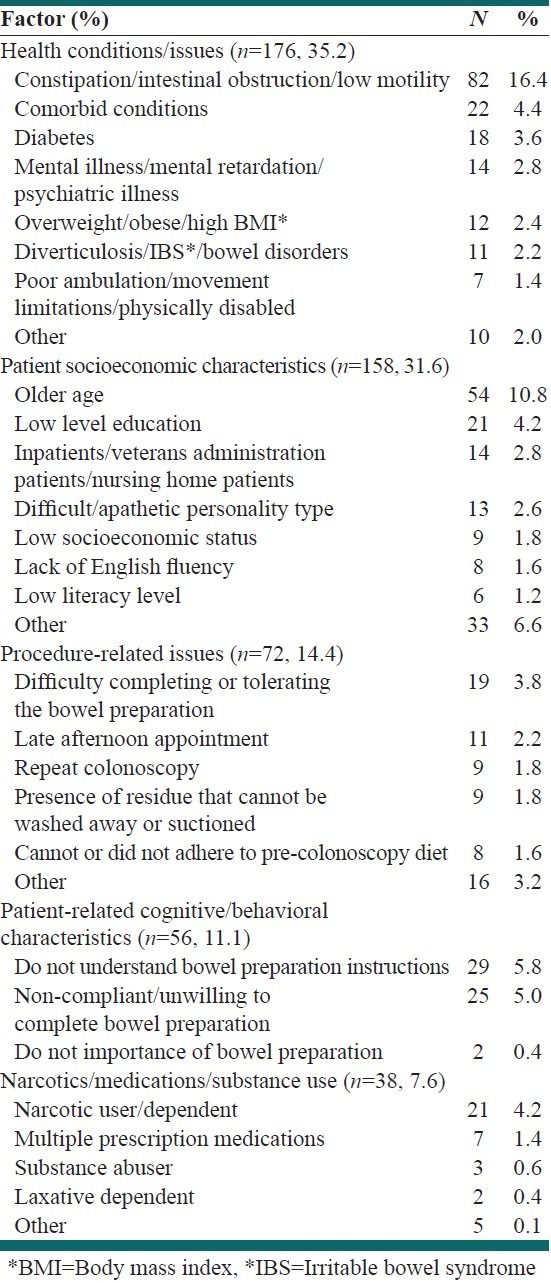

A total of 288 respondents (29% response rate) answered the question, with a total of 500 individual reasons. Characteristics of the respondents are described in greater detail elsewhere.[4] Briefly, participants were younger (mean 48.6 years of age), male and white. Most were educated in the United States and had approximately 17 years of gastroenterology experience and were located in urban areas around the US. The most common factors were grouped into five inductively generated categories such as: Health conditions (35.2%), patient demographic characteristics (31.6%), procedure related issues (14.4%), patient related behavioral characteristics (11.1%) and narcotics/medications/substance use (7.6%) [Table 1]. The most frequently cited health conditions were constipation, intestinal obstruction and low motility followed by general presence of co-morbid conditions and diabetes. Older patients (10.8%) were thought to be more likely to present with sub-optimal bowel preparation as well as those with perceived lower levels of education (4.2%). The Gastroenterologists in our sample less often believed that issues related to the preparation such as difficulty completing or tolerating the purgative (3.8%) contribute substantially to sub-optimal bowel preparation but still noted this factor more often than other issues surrounding the procedure. Similarly, cognitive issues were not a major concern with the exception of a perception that the patient does not understand the instructions (5.8%) or may be unwilling to comply with the full bowel preparation procedure (5.0%). Narcotic use or dependence was believed by a small number of Gastroenterologists (4.2%) to negatively influence bowel preparation quality.

Table 1.

Factors associated with suboptimal bowel preparation (n=500) prior to screening colonoscopy among average risk adults, aged 50 years and older reported by a random sample of American college of gastroenterology physicians (n=288)

DISCUSSIONS

Our study demonstrates that, in the opinion of a national sample of gastroenterologists, patient factors, particularly health conditions and issues followed by patient characteristics, are the most common determinants of sub-optimal bowel preparation. These findings represent consistency in the experience of physicians performing screening colonoscopy on average risk adults from differing practice sizes and types, geographic locations and patient populations across the US. Although others have sought to explore sub-optimal bowel preparation in isolation within the confines of their individual healthcare system among their specific patient population, no single study has queried a large sample of gastroenterologists with an open-ended question to elaborate on their personal experience with the determinants of sub-optimal bowel preparation.

The most commonly reported health conditions by Gastroenterologists in our study, constipation and diabetes, are consistent with the findings of others.[2,7] Factors known to predispose patients to constipation, including Parkinson's disease, use of narcotics and anti-depressants and irritable bowel syndrome were also found to be associated with poor bowel preparation in our study as well as in others.[2,7] Similarly, the concomitant health and life-style issues associated with diabetes reported as predictors of sub-optimal bowel preparation, such as increased body mass index and overweight and obesity, decreased levels of physical activity and poor diet, may serve as surrogate indicators of underlying constipation.[2,13] Certain conditions may serve as proxies for constipation, which may be the more accurate determinant of poor bowel preparation quality.

Patient socio-economic characteristics typical of those most likely to inadequately perform bowel preparation reported by gastroenterologists in our study point to more complex personal and social issues. These may signify deficiencies in literacy, memory, vision and communication skills. Interventions to increase bowel preparation quality utilizing visual aids (cartoons and photographs), simplified written materials and in-person and telephone counseling have resulted in mixed findings, but show promise in certain populations.[14,15]

Despite these findings, this study has limitations. First, the response rate was not optimal, however it is consistent with studies using a similar design in this sample.[16] Other studies of the membership of the American College of Gastroenterology have reported response rates ranging from 5.8% to 32.7%,[16,17,18,19,20] placing our rate of 29% near the top to be expected from this group. We can only speculate that low response rates of this particular group may be related to lack of time, lack of interest, many requests for participation in studies, or lack of appropriate incentives. Randomization of the members in our study, however, was used to control the variation and to improve generalizability of our findings. Second, this is a cross-sectional study and as such the views expressed only represent a single point in time. Third, we know that some barriers to colonoscopy preparation (e.g., older age), cannot be modified. However, many are amenable to change through education.

CONCLUSIONS

This brief report indicates the potential value of a personalized approach to bowel preparation, which addresses the needs of patients with special needs like chronic constipation and diabetes and those with poor literacy skills or poor fluency in English. Additional research to confirm and extend these findings would be useful. In addition, the development and evaluation of educational interventions to address these factors warrants investment.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This study was supported by a National Institute of Health Grant 1U24 CA171524 to GC Hillyer; B. Lebwohl is supported by the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH; Grant Number KL2 RR024157); C.E. Basch is supported by the American Cancer Society (Grant Number RSGT-09-012-01-CPPB), C.H. Basch was supported by a post- doctoral fellowship (R25 CA094601) from the National Cancer Institute at the time this research was conducted and from the ART awards at William Paterson University.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Harewood GC, Sharma VK, de Garmo P. Impact of colonoscopy preparation quality on detection of suspected colonic neoplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:76–9. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hassan C, Fuccio L, Bruno M, Pagano N, Spada C, Carrara S, et al. A predictive model identifies patients most likely to have inadequate bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:501–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lebwohl B, Kastrinos F, Glick M, Rosenbaum AJ, Wang T, Neugut AI. The impact of suboptimal bowel preparation on adenoma miss rates and the factors associated with early repeat colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:1207–14. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.01.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hillyer GC, Basch CH, Lebwohl B, Basch CE, Kastrinos F, Insel BJ, et al. Shortened surveillance intervals following suboptimal bowel preparation for colonoscopy: Results of a national survey. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28:73–81. doi: 10.1007/s00384-012-1559-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rex DK, Imperiale TF, Latinovich DR, Bratcher LL. Impact of bowel preparation on efficiency and cost of colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1696–700. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.A-Rahim YI, Falchuk M. Bowel preparation for flexible sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy. UpToDate®. [Last updated on 2012 Nov 13]. Available from: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/bowelpreparation-for-colonoscopy?source=search_result&search=colonoscopy&selectedTitle=3~150 .

- 7.Ness RM, Manam R, Hoen H, Chalasani N. Predictors of inadequate bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1797–802. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belsey J, Epstein O, Heresbach D. Systematic review: Oral bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:373–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanaka MR, Shah N, Mullen KD, Ferguson DR, Thomas C, McCullough AJ. Afternoon colonoscopies have higher failure rates than morning colonoscopies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2726–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siddiqui AA, Yang K, Spechler SJ, Cryer B, Davila R, Cipher D, et al. Duration of the interval between the completion of bowel preparation and the start of colonoscopy predicts bowel-preparation quality. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:700–6. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wexner SD, Beck DE, Baron TH, Fanelli RD, Hyman N, Shen B, et al. A consensus document on bowel preparation before colonoscopy: Prepared by a task force from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:894–909. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.03.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rothman K, Greenland S. Modern Epidemiology. 3rd ed. New York: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2008. Accuracy considerations in study design. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borg BB, Gupta NK, Zuckerman GR, Banerjee B, Gyawali CP. Impact of obesity on bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:670–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calderwood AH, Lai EJ, Fix OK, Jacobson BC. An endoscopist-blinded, randomized, controlled trial of a simple visual aid to improve bowel preparation for screening colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:307–14. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tae JW, Lee JC, Hong SJ, Han JP, Lee YH, Chung JH, et al. Impact of patient education with cartoon visual aids on the quality of bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:804–11. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trindade AJ, Morisky DE, Ehrlich AC, Tinsley A, Ullman TA. Current practice and perception of screening for medication adherence in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:878–82. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182192207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cattau EL., Jr Colonoscopy capacity in Tennessee: Potential response to an increased demand for colorectal cancer screening. Tenn Med. 2010;103:37, 8–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen LB, Wecsler JS, Gaetano JN, Benson AA, Miller KM, Durkalski V, et al. Endoscopic sedation in the United States: Results from a nationwide survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:967–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sorbi D, Gostout CJ, Peura D, Johnson D, Lanza F, Foutch PG, et al. An assessment of the management of acute bleeding varices: A multicenter prospective member-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2424–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.t01-1-07705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spergel JM, Book WM, Mays E, Song L, Shah SS, Talley NJ, et al. Variation in prevalence, diagnostic criteria, and initial management options for eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases in the United States. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:300–6. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181eb5a9f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]