Abstract

Background:

Postanesthetic shivering (PAS) is an accompanying part of general anesthesia with different unpleasant and stressful complications. Considering the importance of proper prevention of PAS in order to reduce its related adverse complications in patients undergoing surgery, in this study, we investigated the effect of orally administrated tramadol in the prevention of this common complication of general anesthesia.

Materials and Methods:

In this prospective randomized double-blind clinical trial, 80 ASA I and II patients aged 15-70 years, scheduled for elective surgery under general anesthesia, were randomized to intervention (oral tramadol 50 mg) and placebo groups. PAS was evaluated during surgery and in the recovery room, and compared in the two study groups.

Results:

PAS was seen in 5 patients (12.5%) in the intervention group and 10 patients (25%) in the placebo group (P = 0.12). The prevalence of grade III and IV shivering was 7.5% (3/40) and 25% (10/40) in tramadol and placebo groups, respectively (P = 0.03).

Conclusion:

The overall prevalence of PAS was not significantly different in the two study groups, but the higher grades of shivering which needed treatment were significantly lower in the tramadol group than in the placebo, and those patients who received tramadol experienced milder form of shivering. It is suggested that higher doses of tramadol would have better anti-shivering as well as analgesic effects. Studying different doses of tramadol would be helpful in this regard.

Keywords: Oral, postanesthetic shivering, tramadol

INTRODUCTION

Postanesthetic shivering (PAS) is an accompanying part of general anesthesia, with an estimated rate up to 50%.[1] It has different unpleasant and stressful consequences for patients undergoing surgery due to some physiological changes including increasing oxygen consumption, hypoxemia, lactic acidosis, and hypercarbia.[2] These changes, in addition to increasing intraocular and intracranial pressure, may complicate the recovery process during anesthesia and increase the wound pain.[3]

Several studies have investigated the underlying mechanisms of PAS. Accordingly, thermoregulatory and non-thermoregulatory reactions are responsible in this regard.[4,5,6] So, different pharmacologic interventions were studied considering these reactions, but the precise origin of it is not understood yet.[7]

Opioids have significant role among the identified drugs because the effects of different opioids have been studied frequently in this regard and some of them such as pethidine are commonly used for both treatment and prevention of PAS and it considered as the most effective anti-shivering drug.[5,8] But some adverse effects such as respiratory depression, especially in patients with previous history of opioids and anesthetics administration, hypotension, postoperative nausea and vomiting have limited its use.[9]

Recent studies have investigated the effectiveness of tramadol, a synthetic opioid with low risk of respiratory depression, tolerance, and dependence, in treatment and prophylaxis of PAS.[10,11,12]

Tramadol is a centrally acting analgesic with a dual mechanism of action which inhibits the reuptake of 5HT, norepinephrine, and dopamine, and also facilitates 5-hydroxytryptamine 5HT release.[13]

Different studies have evaluated the effect of tramadol, mostly intravenous form, in reducing or preventing PAS, whereas there are reports regarding the side effects of intravenously administrated tramadol and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) also has not approved the use of this form of tramadol.[14] In addition, it seems that oral form of the drug is of low cost compared with its intravenous form.[15] So, considering the importance of proper prevention of PAS in order to reduce its related adverse complications in patients undergoing surgery, in this study, we investigated the effect of orally administrated tramadol in the prevention of this common complication of general anesthesia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this prospective randomized double-blind clinical trial, 80 ASA I and II patients aged 15-70 years, scheduled for elective surgery under general anesthesia in hospitals affiliated to Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, were enrolled.

Patients with a history of convulsions and drug history of using antidepressants, carbamazepine, and sedatives, narcotic or alcohol dependence, or patients who had recent febrile disorder or were dehydrated were excluded from the study. In addition, patients who were hemodynamicaly unstable or had severe bleeding during surgery were excluded.

The Medical Ethics Committee of the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences approved the study protocol and all subjects gave their written consent.

The patients were randomly allocated according to a random number table to receive oral tramadol (50 mg capsule) in the intervention group and placebo (50 mg capsule) with 50 ml water in the placebo group, 1 h before surgery by a physician who was blinded to the name of drugs.

The anesthetic management of the patients was performed according to the standard protocol similarly in the two study groups. The anesthesia was induced with IV fentanyl 2 μg/kg, atracurium 0.5 mg/kg, and thiopental sodium 5 mg/kg. After orotracheal intubation, anesthesia was maintained with nitrous oxide 60% in oxygen and isoflurane 1-1.5%. Morphine was also administered in a dose of 0.1 mg/kg IV to all patients of the study groups.

Oxygen saturation, electrocardiography (ECG), non-invasive blood pressure (NIBP), pulse oximetery (SpO2), and end-tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2) were recorded during surgery. BP (systole and diastole) was monitored before induction of anesthesia, every 5 min during the first 15 min, and every 10 min till the end of surgery. EtCO2 during surgery was maintained at 30-35 mmHg. Central body temperature was recorded via tympanic thermometer during surgery and in the recovery room every 15 min.

Residual neuromuscular blockade was antagonized using neostigmine 0.04 mg/kg and atropine 0.02 mg/kg at the end of surgery. During surgery, skin surface and IV fluid warming were not used. The operating room temperature was set at 22°C-25°C.

After the completion of surgery, when the patient had adequate respiratory efforts and responded to verbal commands properly, the trachea was extubated. The type and duration of anesthesia and surgery were recorded. Anesthesia time was considered as the duration between induction of anesthesia and tracheal extubation. Also, the time from starting of skin incision till wound suture was considered as the surgery time.

In the recovery room, all patients were evaluated for PAS for 1 h and its occurrence was recorded by a trained nurse.

The severity of shivering was evaluated by a four-grade scale by another physician who was not aware of the drugs used. The grading was as follows: 0, no shivering; 1, no muscle contraction but mild fasciculations of face or neck or peripheral vasoconstriction; 2, visible tremor involving one muscle group; 3, visible tremor involving more than one muscle group; and 4, gross muscular activity involving the entire body.[16]

In cases with grade 3-4 shivering for more than 4 min duration, the prophylaxis was considered ineffective and intravenous pethidine 25 mg was administered.

Also, drug side effects and duration of extubation were evaluated and recorded. Patients were discharged from recovery based on modified Aldrete Score criteria.

Side effects of the studied drug, including nausea, vomiting, constipation, light headedness, dizziness, drowsiness, headache, seizure, fever, diarrhea, rash, and itching, were recorded if any.

Statistical analysis

The obtained data were analyzed using SPSS version 15 for windows software, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Chi-square test for all quantitative and qualitative data. P < 0.05 was considered as significant.

RESULTS

In this study, 80 patients (ASA I-II) were randomized in two groups (40 in intervention and 40 in placebo groups).

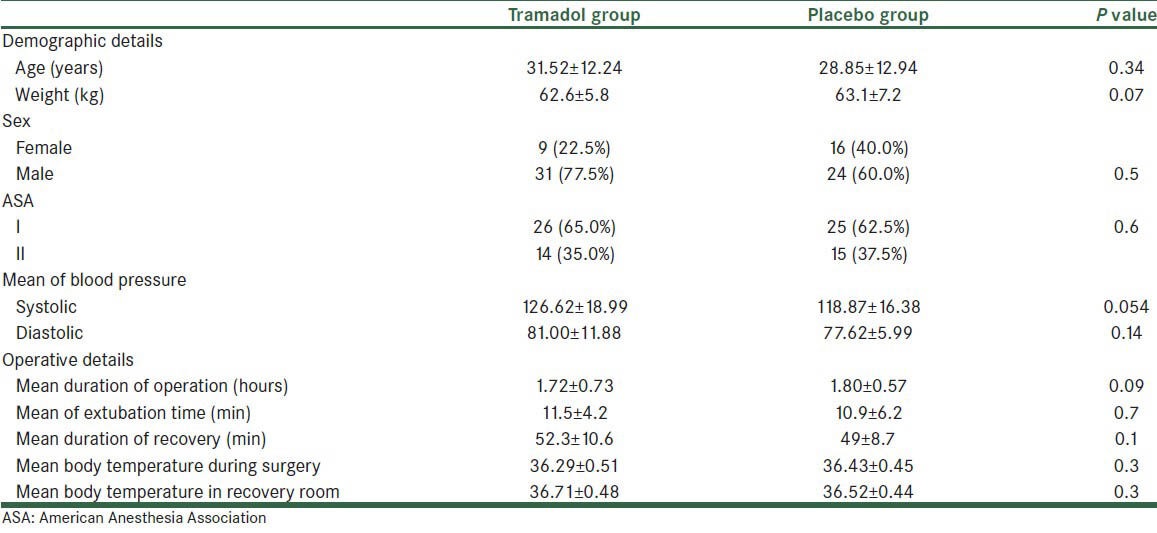

Demographic characteristics and operative details of the studied population in the two study groups are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and operative details of patients in intervention (tramadol) and placebo groups

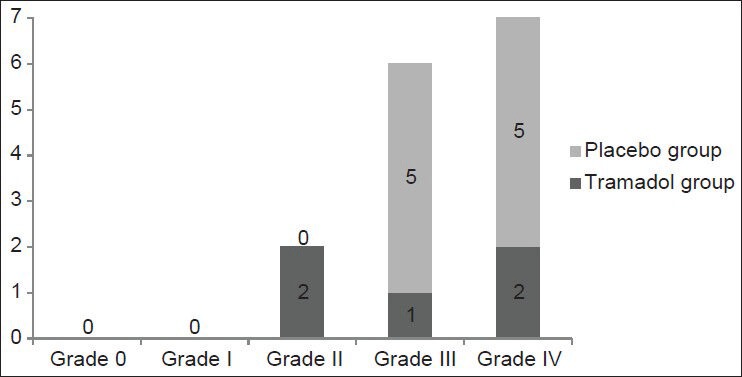

PAS was seen in 5 (12.5%) in the intervention group and 10 (25%) in the placebo group (P = 0.12). Frequency of different grades of shivering in the two study groups is presented in Figure 1. The prevalence of grade III and IV shivering which needed treatment with pethidine (ineffective prophylaxis) was 7.5% (3/40) and 25% (10/40) in tramadol and placebo groups, respectively (P = 0.03).

Figure 1.

Frequency of different grades of shivering in tramadol and placebo groups. P = 0.03 for grade III and IV shivering. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in grade 0, I, II shivering (P > 0.05)

No complication was seen in any of the patients.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the effect of tramadol in preventing PAS was compared with that of placebo. The results indicated that the overall prevalence of PAS was not significantly different from placebo, but the higher grades of shivering which needed treatment were significantly lower in the tramadol group than in the placebo group, and those patients who received tramadol experienced milder form of shivering.

Though many trials have investigated the efficacy of different agents in preventing PAS, in this study, considering the advantages of tramadol, we studied the effect of its oral form for the above-mentioned purpose.

Tramadol is a synthetic opioid which was synthesized in 1962. It has duel mechanism of action by blocking norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake and weak activating the μ-opioid receptors MORs.[13]

The opioid effect of tramadol, mainly mediated through μ receptor and kappa or sigma binding sites, is minimal. But it is suggested that the anti-shivering effect of tramadol is due to the additive or synergistic action of both kappa opioid receptor and α2 adrenergic mechanisms.[17]

Tramadol has higher oral bioavailability and it is highly metabolized, and these characteristics make it an appropriate drug for PAS.[18]

The usefulness of tramadol in PAS has been investigated in many studies. They reported equal or even superior effect to pethidine for tramadol in the prevention of PAS.[10,11,12,13,14,15] Considering that tramadol has less respiratory depression effect and low risk of tolerance and dependence than pethidine, the importance of evaluating its effect becomes more useful.

Many studies conducted for preventing PAS commonly have investigated the effect of IV form of the drug. But there were reports regarding the side effects of its IV form and FDA did not approve the use of tramadol in IV form.[14] In addition, the cost of oral tramadol, even its Sustain Release form, is lower than IV form.[15] So, in this study, the effect of oral tramadol in preventing PAS was determined. We did not find any similar study on literature review.

As mentioned earlier, several studies have confirmed the effectiveness of tramadol in IV form for preventing PAS. Mohta et al. have investigated the effect of different doses of tramadol, i.e., 1, 2, and 3 mg/kg, for prevention of PAS and showed that in all mentioned doses tramadol was useful for the purpose. Moreover, they indicated that tramadol in a dose of 2 mg/kg had the best combination of anti-shivering and analgesic efficacy without excessive sedation. They concluded that tramadol could be a good agent for both anti-shivering and analgesic effects if it is administrated at the time of wound closure.[19]

Heid et al. reported that compared with placebo, intraoperative intravenous administration of tramadol in a dose of 2 mg/kg reduced the incidence and severity of postoperative shivering.[20]

De Witte and colleagues showed that administration of higher dose of tramadol (3 mg/kg) at the time of wound closure prevented PAS in all studied patients.[21] In this study, we used a single dose of 50 mg tramadol capsule; it seems that the dose is lower than 1 mg/kg and if we had used higher dose of oral tramadol, it would have been more effective for preventing PAS.

The effect of tramadol for PAS has been investigated in some studies in Iran. In Tabriz, Atashkhoyi et al. studied the effect of single dose of tramadol on prevention of PAS prior to induction of general anesthesia and showed that the rate of PAS was significantly lower in the tramadol group than in the placebo group.[22]

Javaherforoush et al. have reported similar results; accordingly, their findings support the safety and effectiveness of tramadol in prevention and treatment of PAS.[17]

In this study, though the overall incidence of PAS was not significantly different in the two groups, severe grades of PAS were significantly lower in the tramadol group. It may be due to small sample size and the administered dose of tramadol. It seems that 100 mg tramadol would have better anti-shivering and analgesic effects. However, it would be investigated in future studies.

The limitation of our study was the small sample size of the studied population. We recommended that for achieving more conclusive results, the effect of tramadol in preventing postoperative shivering is to be compared with pethidine, the most effective drug in this field. Also, studying different doses of tramadol would be helpful in this regard.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was funded by the Bureau for Research, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. We thank all doctors, nurses, and the staff working in hospitals affiliated to Isfahan University of Medical Sciences and patients for their kind cooperation with our research project.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Bureau for Research, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asl ME, Isazadefar K, Mohammadian A, Khoshbaten M. Ondansetron and meperidine prevent postoperative shivering after general anesthesia. Middle East J Anesthesiol. 2011;21:67–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gecaj-Gashi A, Hashimi M, Sada F, Salihu S, Terziqi H. Prophylactic ketamine reduces incidence of postanaesthetic shivering. Niger J Med. 2010;19:267–70. doi: 10.4314/njm.v19i3.60181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sessler DI. Temperature monitoring. In: Miller RD, editor. Miller's anesthesia. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2005. pp. 1571–97. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhattacharya PK, Bhattacharya L, Jain RK, Agarwal RC. Post Anesthesia Shivering: A review. Indian J Anaesth. 2003;47:88–93. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shrestha AB. Comparative study on effectiveness of doxapram and pethidine for postanaesthetic shivering. J Nepal Med Assoc. 2009;48:116–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alfonsi P. Postanaesthetic shivering: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and approaches to prevention and management. Minerva Anestesiol. 2003;69:438–42. Review. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahamood MA, Zweifler RM. Progress in shivering control. J Neurol Sci. 2007;261:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roy JD, Girard M, Drolet P. Intrathecal meperidine decreases shivering during cesarean delivery under spinal anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2004;98:230–4. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000093251.42341.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Techanivate A, Dusitkasem S, Anuwattanavit C. Dexmedetomidine compare with fentanyl for postoperative analgesia in outpatient gynecologic laparoscopy: A randomized controlled trial. J Med Assoc Thai. 2012;95:383–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.le Roux PJ, Coetzee JF. Tramadol today. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2000;13:457–61. doi: 10.1097/00001503-200008000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mathews S, Al Mulla A, Varghese PK, Radim K, Mumtaz S. Postanaesthetic shivering-a new look at tramadol. Anaesthesia. 2002;57:394–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2002.2457_3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trekova NA, Buniation AA, Zolicheva NI. Tramadol hydrochloride in the treatment of postoperative shivering. Anesteziol Reanimatol. 2004:86–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grond S, Sablotzki A. Clinical pharmacology of tramadol. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004;43:879–923. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200443130-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.U.S. Food and drug administration web site; [Last accessed on 2011 May 1]. Drugs @ FDA page. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/default.htm . [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaye K, Theaker N New South wales therapeutic assessment group. Sydney: NSW TAG; 2001. TRAMADOL: A position statement of the NSW therapeutic assessment group Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crossly AW, Mahajan RP. The intensity of postoperative shivering is unrelated to axillary temperature. Anaesthesia. 1994;49:205–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1994.tb03422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Javaherforoosh F, Akhondzadeh R, Aein KB, Olapour A, Samimi M. Effects of Tramadol on shivering post spinal anesthesia in elective cesarean section. Pak J Med Sci. 2009;25:12–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raffa RB, Nayak RK, Minn FL. The mechanism(s) of action and pharmacokinetics of tramadol hydrochloride. Rev Contemp Pharmacother. 1995;6:485–97. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohta M, Kumari N, Tyagi A, Sethi AK, Agarwal D, Singh M. Tramadol for prevention of postanaesthetic shivering: A randomised double-blind comparison with pethidine. Anaesthesia. 2009;64:141–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2008.05711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heid F, Grimm U, Roth W, Piepho T, Kerz T, Jage J. Intraoperative tramadol reduces shivering but not pain after remifentanil-isoflurane general anaesthesia. A placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2008;25:468–72. doi: 10.1017/S0265021508003645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Witte J, Deloof T, De Veylder J, Housemans PR. Tramadol in the treatment of postanaesthetic shivering. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1997;41:506–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1997.tb04732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atashkhoyi S, Niazi M, Iranpour A. Effect of tramadol adiministratian previous to induction of general anesthesia on prevention of postoperative shivering. J Zanjan Univ Med Sci Health Serv. 2008;16:29–36. [Google Scholar]