Abstract

Purpose

Effective therapies for KRAS mutant colorectal cancer (CRC) are a critical unmet clinical need. Previously, we described GEMMs for sporadic Kras mutant and non-mutant CRC suitable for preclinical evaluation of experimental therapeutics. To accelerate drug discovery and validation, we sought to derive low-passage cell lines from GEMM Kras mutant and wild-type tumors for in vitro screening and transplantation into the native colonic environment of immunocompetent mice for in vivo validation.

Experimental Design

Cell lines were derived from Kras mutant and non-mutant GEMM tumors under defined media conditions. Growth kinetics, phosphoproteomes, transcriptomes, drug sensitivity, and metabolism were examined. Cell lines were implanted in mice and monitored for in vivo tumor analysis.

Results

Kras mutant cell lines displayed increased proliferation, MAPK signaling, and PI3K signaling. Microarray analysis identified significant overlap with human CRC-related gene signatures, including KRAS mutant and metastatic CRC. Further analyses revealed enrichment for numerous disease-relevant biological pathways, including glucose metabolism. Functional assessment in vitro and in vivo validated this finding and highlighted the dependence of Kras mutant CRC on oncogenic signaling and on aerobic glycolysis.

Conclusions

We have successfully characterized a novel GEMM-derived orthotopic transplant model of human KRAS mutant CRC. This approach combines in vitro screening capability using low-passage cell lines that recapitulate human CRC and potential for rapid in vivo validation using cell line-derived tumors that develop in the colonic microenvironment of immunocompetent animals. Taken together, this platform is a clear advancement in preclinical CRC models for comprehensive drug discovery and validation efforts.

Keywords: Kras, MAPK, PI3K, colorectal cancer, GEMM, orthotopic model

INTRODUCTION

Activating KRAS mutations are observed in 40–50% of human colorectal cancer (CRC) and pose a significant therapeutic challenge because of their inherent resistance to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) antibodies, such as cetuximab (Erbitux) or panitumumab (Vectibix) (1). Whereas this underscores the urgent need for development of novel therapeutic strategies, the overall success rate for the clinical approval of oncology drugs continues to be less than 10% (2). As the largest failure rates occur when efficacy in human patients is first directly assessed (phase II trials), robust pre-clinical models that faithfully model human disease are critical to maximize the efficiency of the clinical drug development pipeline.

The majority of CRC genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs) employ germ-line or tissue-wide modification of genes that are critical for CRC carcinogenesis (3). Although these are useful models for hereditary cancer predisposition syndromes, such as Familial Adenomatous Polyposis and Lynch Syndrome, they are poor surrogates for sporadic CRC, which comprises ~80% of all CRC cases (4). Furthermore, the majority of these murine tumors present in the small intestine rather than the colon. To circumvent this problem, we have recently described novel GEMMs for sporadic CRC based on the delivery of adenovirus expressing cre recombinase (AdCre) in a restricted fashion to the distal colon of floxed mice (5). This is a faithful surrogate for human sporadic CRC, as it is based on stochastic and somatic modification of genes known to be important in human CRC, resulting in colonic tumors that develop in the context of the colonic microenvironment of immunocompetent mice. We have successfully used this model to stratify multiple therapeutic responses according to underlying tumor genotype (5, 6). Whereas this is a powerful approach that recreates human CRC with the utmost fidelity, it is more suitable for hypothesis-driven mechanistic interrogation of specific targeted therapies, rather than large-scale high throughput drug discovery efforts.

To create a high throughput drug discovery-validation platform that closely mimics human CRC, we developed a novel GEMM-derived orthotopic transplant model that combines the capability for traditional in vitro high throughput drug screening with rapid in vivo validation in the context of a species-matched tumor-stroma microenvironment and an intact immune system. Several high throughput drug screening approaches rely on the use of pre-existing highly passaged human CRC cell lines with poorly defined genetics; in addition, investigators have utilized patient-derived tumorgraft models in which a human tumor fragment is serially passaged in an immunodeficient mouse host in order to study its biological characteristics and response to therapeutics. Here, we have utilized primary tumor tissue from our GEMMs for sporadic CRC to derive low passage, genetically-defined cell lines, thus providing a platform for rapid in vitro drug discovery. Furthermore, to facilitate rapid in vivo candidate drug validation, we developed a procedure to engraft these cell lines into the native colonic environment of immunocompetent mice, thus modeling the appropriate tumor-stroma-immune microenvironment for CRC carcinogenesis.

Thus, GEMMs have become a useful system in which to recapitulate and investigate a broad spectrum of human diseases, including cancers which derive from somatic genetic events. As is the case with any model of human disease condition, there are benefits as well as limitations to GEMMs as models of human carcinogenesis. Our GEMMs of CRC have certain advantages over traditional human tumor cell lines in that they are low-passage and clearly genetically defined, as well as over human tumorgrafts, in that they can be studied within the context of a colonic environment with a fully intact immune system. Indeed, there are limitations with any GEMMs of human disease, including the possibility that there may be aspects of human CRC not fully captured within the context of the limited driver mutations we have engineered into these models. In addition, the extent to which these models recapitulate the therapeutic response seen in human CRC patients may also be incomplete. Nonetheless, we feel that a successful preclinical effort must take advantage of all possible models of the human disease condition, and that these GEMMs play a useful role within such a comprehensive effort.

Since KRAS mutational status is an independent predictor of treatment response in CRC (1), we generated GEMMs of advanced CRC based on: 1) somatic loss of the tumor suppressors Apc and p53 (AP) and 2) Apc and p53 loss with concomitant gain of an activating Kras mutation (AKP). Subsequently, we derived corresponding panels of murine cell lines and demonstrated that they contain many canonical features of human CRC biology. Finally, we successfully engrafted these cell lines into the appropriate colonic microenvironment of immunocompetent mice and observed robust tumor growth and development. Here we present the development, characterization, and validation of our novel discovery-validation platform and highlight its utility by demonstrating: 1) the predisposition of Kras mutant tumors and tumor-derived cell lines towards enhanced growth and proliferation; 2) the dependency of Kras mutant tumors on oncogenic signaling; 3) the generation of a Kras signature which closely resembles several recently published CRC signatures and is enriched for hallmark CRC characteristics; 4) the propensity of Kras mutant tumors towards aerobic metabolism; and 5) how this phenotypic difference might be exploited for PET-based diagnoses of Kras mutant tumors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genetically Engineered Mouse Models (GEMM)

The generation and genotyping of ApcCKO, KrasLSL-G12D, and p53flox/flox genetically engineered mice has been previously described (Supplemental Figure 1 and (5)). To generate compound mutant mice, ApcCKO and p53flox/flox mice were crossed to generate ApcCKO p53flox/flox (AP) mice and ApcCKO, KrasLSL-G12D, and p53flox/flox mice were crossed to generate ApcCKO, KrasLSL-G12D, and p53flox/flox (AKP) mice.

Adenoviral Infection of the Colonic Epithelium and Endoscopy

12-week old mice were infected with 109 pfu Ad5CMVcre (AdCre) (Gene Transfer Vector Core, University of Iowa) after surgical laparotomy under anesthesia (2% isoflurane), as described (5). Resulting compound genotypes and nomenclature are depicted in Supplemental Figure 1. Mice were followed with biweekly optical colonoscopy for tumor development. The Tumor Size Index (TSI) based on the relative ratio of the cross sectional areas of the tumor to that of the colonic lumen was derived as described (5, 6). Tumor-bearing mice with TSI > 75 were euthanized, and the colons were removed, opened longitudinally, and rinsed with cold PBS. Tumors fragments were isolated for genomic analysis, histology, and cell line establishment. This research protocol was approved by our attending veterinarian, by the Tufts Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), and by the Tufts Medical Institutional Biosafety Committee.

Derivation of Tumor Cell Lines

Tumor samples were washed in 0.04% sodium hypochlorite followed by multiple PBS-gentamycin washes. Samples were minced and digested in collagenase D/dispase (Roche), collected by centrifugation, and digested further in 0.3% pancreatin (Roche) at 37°C. Digested samples were passed through a 40 μm cell strainer (BD Biosciences), collected by centrifugation, re-suspended in defined culture media (DMEM, 10%FBS, 0.2 ng/ml EGF, 1X Insulin-Transferrin-Selenium (Invitrogen), 2.5 μg/ml gentamycin), and plated on 60 mm2 collagen IV coated dishes (BD Biosciences). Mutational analysis was confirmed using our genotyping protocol as described in the Supplemental Methods.

Additional detailed methods are available in the Supplement.

RESULTS

KrasG12D accelerates carcinogenesis in GEMM models of sporadic CRC

Colonic tumors were induced through surgical administration of AdCre to generate ApcCKO p53Δ/Δ (AP) and APCCKO KrasG12D p53ΔΔ (AKP) tumors, respectively (Supplemental Figure S1), and followed by optical colonoscopy (Figure 1A). Whereas initial tumor formation was observed in AP mice by seven weeks after surgical induction, neoplastic lesions were detected in AKP mice in as little as two weeks. Analysis of composite tumor growth curves further confirmed more robust tumor growth in AKP compared to AP mice (Figure 1B). In addition, the rate of histologic progression was accelerated in AKP mice (Figure 1C–D). Collectively, these data suggest that somatically activated oncogenic KrasG12D promotes tumor progression in the context of an ApcCKO p53ΔΔ genetically permissive background.

Figure 1. Heterozygous KrasG12D in AKP GEMM strains accelerates tumor formation.

A) Representative endoscopic images of AP and AKP tumors taken every 2 to 3 weeks. B) Growth curves measured from endoscopy show that the AKP strains develop at a faster rate by ~8x than AP at 10 weeks. C) Resulting primary tumors range from adenomas to carcinomas to invasive carcinomas (representative images of each are shown). D) Frequency of tumor development after AdCre injection.

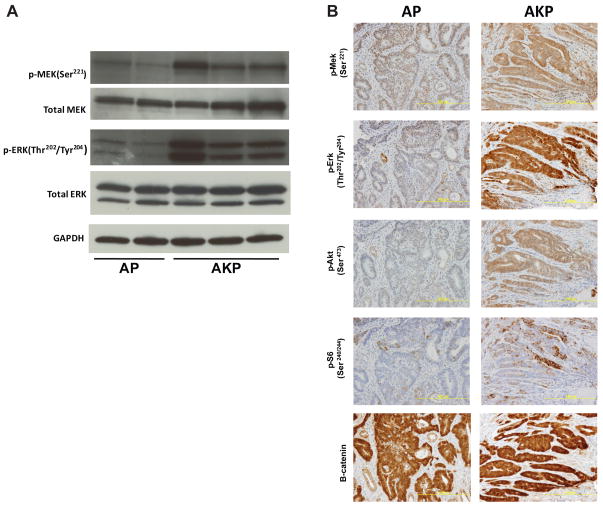

KrasG12D increases MAPK and PI3K/mTOR but has no effect on WNT signaling in colonic tumors

We have previously demonstrated that introduction of KrasG12D activates the downstream MAPK pathway in tumors derived from Apc mutation (5). To examine if a similar response exists in tumors harboring an additional p53 mutation, protein analysis was performed by western blot to compare levels of p-MEK and p-ERK in individual AP and AKP tumors. While levels of total MEK and ERK were equivalent, AKP tumors demonstrated elevated levels of p-MEK and p-ERK throughout their progression (Figure 2A). These findings, along with activation of PI3K and mTOR signaling, were confirmed by immunohistochemistry (Figure 2B). Next, we examined nuclear and cytoplasmic levels of β-catenin and found that tumors from both AP and AKP mice demonstrated specific accumulation relative to adjacent normal mucosa, which is indicative of aberrant WNT signaling (Supplemental Figure 2B). Taken together, these data suggest that KrasG12D activates MAPK and PI3K/mTOR signaling and accelerates tumor progression in the context of colonic tumors with Apc and p53 deficiency.

Figure 2. Elevated levels of MAPK, PI3K and mTOR signaling in tumors from AKP strain.

A) Western blots for MAPK proteins using dissected tumor lysates from AP and AKP strains. Phospho- (pMekSer221 and p-ErkThr220/Tyr204) levels of MAPK signaling are elevated in AKP, while total (Mek and Erk) levels are unchanged. B) Immunohistochemical staining in AP and AKP tumor sections. In AKP strains, elevated levels of MAPK (p-MekSer221 and pErkThr220/Tyr204), PI3K (p-AktSer473), mTorc (p-S6Ser240/244), and WNT (β-catenin) signaling are observed.

AP and AKP tumor-derived cell lines are robust in vitro models for CRC

To interrogate KrasG12D CRC biology in the context of Apc and p53 deficiency, we derived low passage primary cell lines from individual AP and AKP colonic tumors. To verify proper recombination of the genetically engineered alleles, we used PCR to examine both primary tumors and cell lines. As expected, both AP and AKP primary tumors, which are comprised of a heterogeneous mixture of tumor cells, supporting stroma, and immune cells, contain a mixture of both non-recombinant and recombinant alleles. After short-term passage (P<3) in vitro, PCR analysis demonstrated uniform loss of the non-recombinant alleles (Figure 3A). This suggests that the epithelial cells harboring genetically modified alleles obtain a growth advantage in vitro and that these cells eventually dominate the cultured cell population.

Figure 3. Generation of colon epithelial tumor cell lines from AP and AKP GEMM models and characterization of growth kinetics.

A) Deletion of APC, Kras and p53 in cell lines from AP and AKP. PCR genotyping confirms that tail contains non-recombined Apc (flox= 430 bp), Kras (LSL = 500 bp) and p53 (flox = 370 bp) alleles, and cell lines only recombined Apc (CKO = 500 bp), Kras (ΔLSL = 700 bp) and p53 (Δ = 612 bp) alleles. Tumor samples at the time of dissection contain epithelial cells and other cell types, consequently, the floxed Apc, Kras and p53 alleles are present as well as the Cre-recombined alleles. B) Cumulative population doublings (CPDs) in AP and AKP cell lines. AKP lines display a greater rate of doubling compared to AP lines. C) Spheroid growth assay in AP and AKP cell lines on low adhesion nanoculture plates. AKP lines form larger spheroids and enhanced viability over time as evidenced by Cell Titer Glo (CTG). D) In vivo tumor growth in AP, AKP cell lines. Cell lines were transplanted into nude mice subcutaneously and tumor volume was measured over time. AKP lines display an increased rate of in vivo growth compared to AP lines.

Next, we examined the in vitro and in vivo growth characteristics of AP and AKP cell lines. Cumulative population doublings (CPDs) demonstrate that AKP cells grow at a faster rate compared to AP cells (~0.5 vs 1.5 PDs per day, Figure 3B). To further characterize in vitro growth capabilities, AP and AKP cell lines were grown in spheroid-inducing conditions. Consistent with their ability to grow more rapidly in a monolayer, AKP lines also form larger spheroids as evidenced by microscopy as well as a viability assay (Figure 3C). Finally, we performed subcutaneous injections of AP and AKP cells into nude mice. As indicated in Figure 3D, AKP lines displayed an enhanced ability to grow in an immunocompromised in vivo setting compared to AP lines. Taken together, these data demonstrate that the addition of KrasG12D confers a growth advantage in vitro and in vivo.

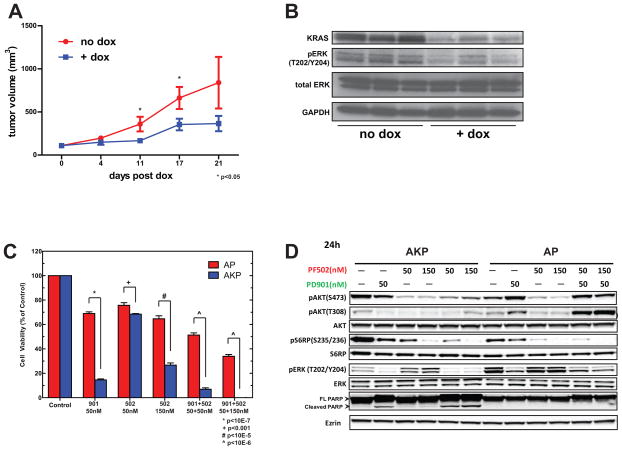

Mutant Kras tumor derived cell lines are dependent on oncogenic signaling

Due to elevated MAPK and PI3K/AKT signaling in vivo (Figure 2), we hypothesized that Kras mutant tumor derived cell lines would also be highly dependent on oncogenic signaling. First, Kras dependency was assessed in AP and AKP cell lines, by examining the effects of two independent hairpins targeting Kras. As shown in Figure S5A, AKP cell lines exhibited a marked decrease in cell viability upon Kras knockdown using small interfering RNA, while AP cell lines were not significantly affected despite protein knockdown being comparable (Figure S5B). These results indicated that the AKP cell lines tested displayed a greater dependency on Kras than AP cell lines, which is consistent with our hypothesis of Kras mutant cell lines require oncogenic Kras for survival. To interrogate the degree of Kras-dependency in AKP cell lines in vivo, we performed inducible RNA-interference of Kras in established tumors in vivo. Following doxycycline administration, pronounced growth inhibition was observed relative to non-induced control tumors (Figure 4A). Following 4 days of doxycycline treatment, we examined tumors from both treated (n=3) and untreated (n=3) mice by Western blot. Tumors exposed to doxycline demonstrated robust knockdown of Kras and consequently loss of p-ERK, suggesting that AKP tumor growth in vivo is reliant on MAPK signaling endowed by oncogenic Kras (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. AKP cell lines are dependent on oncogenic MAPK and PI3K/AKT signaling.

A) In vivo tumor growth inhibition of AKP tumor derived cell lines by doxycycline (dox) inducible Kras knockdown. B) Representative western blot analysis of established subcutaneous tumors following mock or dox treatment. Tumors were harvested 4 days post- induction of shRNA. C) Western blot analysis of the MAPK and PI3K/AKT pathways following single or combination treatment with the pathway selective inhibitors PD-325901 and PF-04691502. AKP and AP cells were treated with control, 50 nM PD-325901, 50 or 150 nM PF-04691502, or combinations for 72 hours, and cell viability was assessed. D) Western blot analysis of AKP and AP cells treated with control, 50 nM PD-325901, 50 or 150 nM PF-04691502, or combinations for 24 hours.

Next we examined the effect of MAPK and PI3K/mTOR inhibition using the pathway selective small molecule inhibitors PD-0325901 and PF-04691502, respectively. Treatment with the MEK inhibitor PD-0325901 revealed significantly greater sensitivity (p ≤ 10−7, Figure 4C) in Kras mutant cells, while treatment with the PI3K/mTOR inhibitor PF-04691502 demonstrated a slightly enhanced sensitivity in Kras mutant cells to a lower dose (50 nM, p ≤ 0.01, Figure 4C). Subsequently, a 3-fold increase in PF-04691502 concentration had a greater impact on cell viability with AKP cells exhibiting greater sensitivity to drug treatment (p≤10−5, Figure 4C). Treatment using combinations of each drug demonstrated an additive effect in both AKP and AP cells with AKP cells showing a marked decrease in viability when compared to non-Kras mutant AP cell lines (p≤10−6, Figure 4C). As expected, Western blot analysis of cells exposed to individual doses of PD-0325901 and PF-04691502 demonstrated a robust attenuation of p-MAPK and p-PI3K/AKT signaling, respectively, at 6 hours (not shown) and 24 hours (Figure 4D). A decrease in both effector pathway phosphosignaling was observed in both AKP and AP cells with combinations of PD-0325901 and PF-04691502 after 6 hours of treatment (not shown); however, restoration of both p-AKTThr308 and p-AKTSer473 occurred only in non-Kras mutant AP cells after 24 hours (Figure 4D). In addition, the appearance of the apoptotic marker cleaved PARP arose only in AKP cells following a 24 hour treatment with either PD-0325901 or the combination of PD-0325901 and PF-04691502 (Figure 4D) and is consistent with the decreased viability observed (Figure 4C). These results suggest that an acquired or intrinsic non-KrasG12D mediated bypass mechanism confers relative resistance in AP cells through the induction of p-AKT. Collectively, these data demonstrate that Kras mutant cell line growth and viability is dependent on oncogenic signaling, as well as Kras itself.

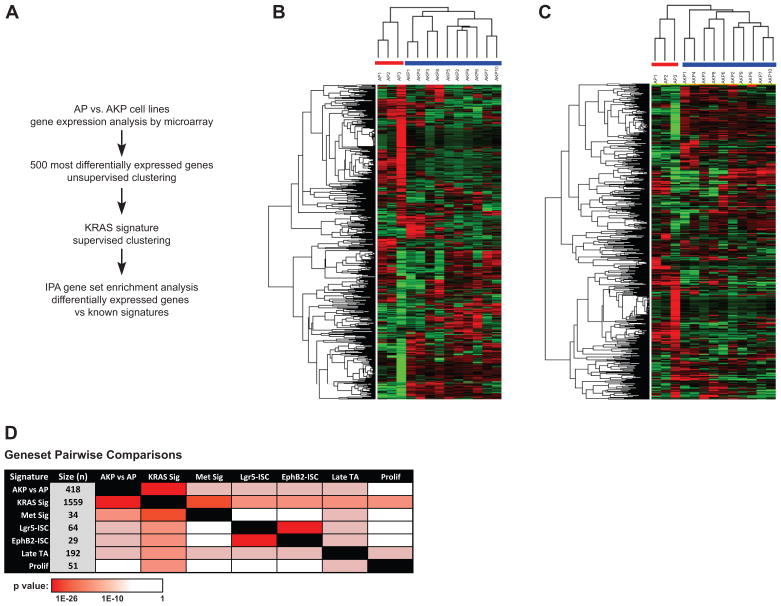

Transcriptomic analysis reveals tumor derived cell lines capture relevant signatures of human CRC

To further characterize the extent to which our GEMM models recapitulate human disease, gene expression profiling was performed on cell lines derived from 13 murine colon adenocarcinomas (analysis scheme outlined in Figure 5A). The 500 most significantly varied genes were identified using a two-sample t-test (FDR<0.05, 2-fold change) and used for hierarchical unsupervised clustering of three AP and ten AKP cell lines. As indicated in Figure 5B, cell lines clustered into two main groups and in concordance with their respective Kras genotypes. Differences in gene expression between AKP vs. AP cell lines was further refined by performing supervised clustering using a composite of published Kras gene signatures (Kras Sig, see Supplemental Methods). This approach was also able to discriminate successfully between AKP and AP status (Figure 5C).

Figure 5. Gene expression analysis of AP and AKP cell lines.

A) Workflow of genomic analysis performed on AP and AKP cell lines. B) Unsupervised clustering results based on the 500 most varied genes from 3 AP and 10 AKP cell lines. Log2 transformed data was further adjusted by means and then clustered. Cell lines clearly cluster based on genotype. C) Supervised clustering was performed on the 3 AP and 10 AKP cell lines, using an independent Kras signature gene list (Kras Sig, see methods). A total of 544 differentially expressed genes were used in this clustering (see methods). Log2 transformed data was adjusted and clustered as in B. Again, cell lines cluster based on genotype. D) Pairwise comparisons using the AKP vs. AP signature and published CRC signatures. A detailed description of each signature is provided in the Supplemental Methods.

To determine if differential gene expression among AKP and AP cell lines contains any significant overlap with published comparative murine-human signature gene datasets, pairwise comparisons were made to several CRC-related and KRAS signatures (7–9). Briefly, the genes differentially expressed in AKP vs. AP were mapped to human orthologues (renamed AKP vs. AP signature, see Supplemental Table S1) and compared to humanized gene signatures of interest, including a composite KRAS signature (9), a CRC metastasis signature (10), and intestinal epithelial signatures (ISC) (11). As indicated in Figure 5D, our list of differentially expressed genes displays significant overlap with several published CRC datasets. Notably, the AKP vs. AP gene set shows a striking overlap with a composite KRAS signature dataset (Kras Sig, Figure 5C). In addition, a significant overlap was observed between our signature with two ISC signatures (Lgr5hi and Ephb2hi), a late TA signature, and a CRC signature derived from a murine experimental metastasis model (11).

To determine whether our AKP vs. AP signature was enriched in known disease genesets or pathways, we utilized Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software. The top five biological disease categories are listed in Supplemental Table S2. Top disease categories include cancer and gastrointestinal disease, as well as metabolic disease, which may contribute in part to the altered growth kinetics observed in AKP lines. Collectively, these findings suggest that our model displays many of the transcriptional and pathway characteristics observed in intestinal biology, CRC, and oncogenic Kras.

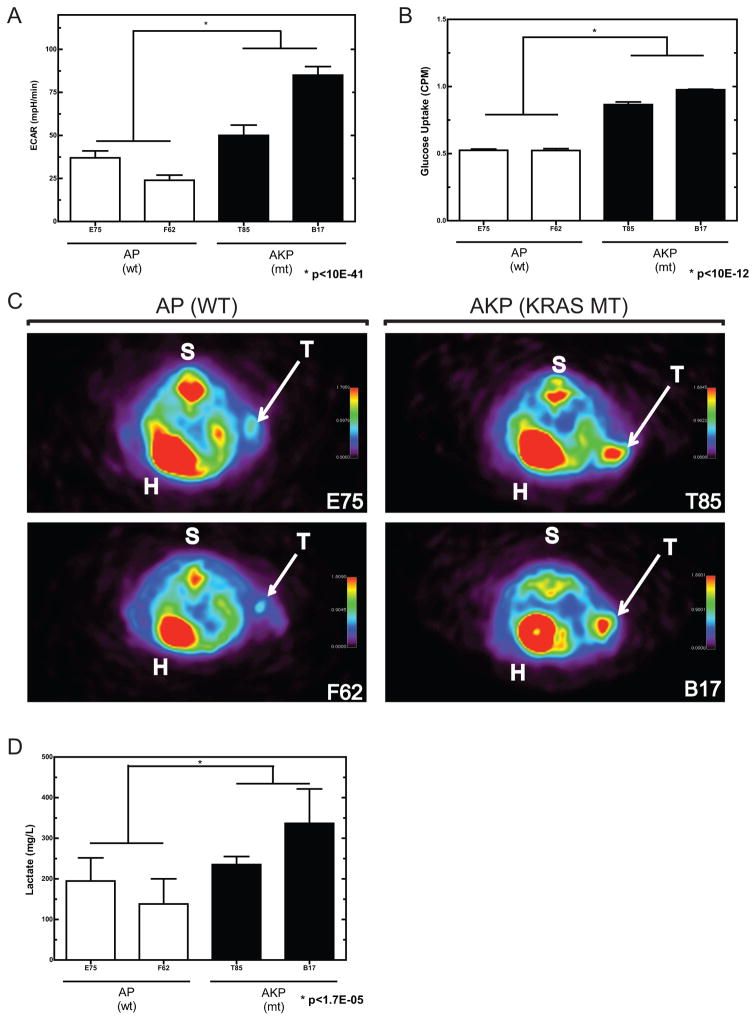

Oncogenic Kras promotes an increase in cellular glucose uptake and lactate production in vitro and in vivo

To examine potential effects of mutant Kras on cellular metabolism, we measured in vitro bioenergetic activity in AP and AKP cell lines, using the ratio of oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR), as a surrogate metabolic determinant. These analyses indicate that AP and AKP cell lines display a differential metabolic profile. OCR/ECAR ratios from Kras mutant cell lines are significantly decreased compared to wild-type counterparts (Supplemental Figure S3B). This is the result of an increased ECAR in AKP compared to AP cell lines (Figure 6A), with OCR remaining relatively similar in the two groups (Supplemental Figure S3A). In addition, AKP cell lines displayed enhanced glucose uptake compared to AP lines (Figure 6B). Taken together, these data indicate that activating Kras mutation may affect the metabolic characteristics of these cell lines.

Figure 6. Assessment of in vivo glucose uptake and lactate production in subcutaneous tumors.

A) In vitro measurement of extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) in AP and AKP cell lines. B) In vitro glucose uptake in AP and AKP cell lines. C) Subcutaneous tumors imaged by positron emission tomography (PET) following injection of 18F-FDG. Regions of enhanced signal include heart (H), spine (S), and tumor (T). Tumors from AKP cell lines (Kras mutant) display a greater signal than those from AP cell lines (Kras wildtype). D) AKP tumors display elevated lactate metabolite abundance.

Given this differential metabolic profile in vitro, we wished to confirm this finding in vivo. To this end, we prepared subcutaneous tumors from AP and AKP cell lines. Upon tumor formation, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) was administered via tail vein injection and mice were imaged by positron emission tomography (PET). As anticipated, FDG-PET produced an appreciable signal in heart (H), spine (S), and tumor (T). As indicated in Figure 6C, subcutaneous tumors from Kras mutant AKP lines produced a significantly higher FDG-PET signal. In addition, both mean and maximum calculated standardized uptake values (SUV) were greater in AKP lines (Supplemental Figures S3C and D). To determine if oncogenic Kras contributed to a concomitant increase in lactate production, intra-tumor lactate concentration was measured biochemically. Subcutaneous tumors from Kras mutant AKP cell lines had significantly more lactate than those with wild-type Kras (Figure 6D), a finding consistent with the Warburg Effect (12). Taken together, this data indicates that oncogenic Kras contributes to enhanced glucose uptake and glycolytic metabolism in our model system. In addition, given these findings, we performed a further investigation of our transcriptomic data to assess whether glucose transporters were differentially regulated. Indeed, the glucose transporter SLC2A1 (GLUT-1) is differentially expressed in our Kras mutant models, as indicated in Figure S6, further suggesting that alterations in Kras may lead to dysregulation of relevant metabolic programs.

Intrasplenic injection of cell lines results in tumor formation at an orthotopic metastatic site

Given that the common therapeutic approach to treating advanced CRC is to treat the metastatic sites, we sought to determine whether our GEMM tumor cell lines could recapitulate metastatic growth. To this end, we performed intrasplenic injections of two independent AKP cell lines and observed growth in the liver. As indicated in Figure S4, both lines created appreciable tumor masses in the liver, as indicated by gross pathology, H&E staining and PET/CT (Figures S4A, B and C, repectively). Thus, these results demonstrate that our GEMM tumor cell line models can be utilized to test future preclinical therapeutic strategies for treating metastatic lesions.

Orthotopic transplantation of cell lines into the distal colon results in invasive adenocarcinoma

To create an orthotopic model of invasive adenocarcinoma in an immunocompetent host, we established a method for transplanting cell lines derived from primary colonic tumors into the native colonic environment of a syngeneic immunocompetent recipient host mouse (see Supplemental Methods). A representative endoscopic image of a tumor established from an injection of AKP cells is shown in Figure S2A. Resulting tumors were excised after 5 weeks and sectioned. As indicated in Figure S2B, H&E sections of tumor and adjacent normal tissue indicated that these tumors are poorly differentiated, while immunohistochemical analysis found that tumor regions contained elevated nuclear β-catenin and phosphorylated constituents of the MAPK pathway compared to adjacent normal tissue, markers of deregulated WNT signaling, and colonic transformation. Furthermore, staining for Ki67 and PECAM (CD31), markers of mitosis and angiogenesis, respectively, indicated an elevated proliferation rate and angiogenic response within tumor areas, as compared to adjacent normal colon tissue (Figure S2B).

DISCUSSION

Activating KRAS mutations are commonly seen in 40–50% of human CRC (13). Whereas the prognostic role of such mutations is controversial, it is evident that they are powerful positive predictors for resistance to treatment with anti-EGFR therapies, such as cetuximab or panitumumab (14, 15). Because of the central role for KRAS in EGFR and other receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) signaling pathways during CRC carcinogenesis (16), robust KRAS-specific treatments are desperately needed for effective CRC treatment. As such efforts have been widely unsuccessful to date (17), the development of novel therapeutic approaches for treatment of KRAS mutant CRC is a critical unmet clinical need.

Despite the identification of many candidate drug compounds during pre-clinical discovery efforts, the subsequent rate of success through the clinical trial pipeline is abysmal (18). Traditional preclinical drug discovery platforms often rely on genetically undefined and highly passaged human tumor cell lines. The in vitro discovery phase is often followed by in vivo validation in immunodeficient mice that suffer from complete species mismatch in the tumor microenvironment. This is a significant shortcoming in light of the increasing evidence implicating the critical interplay between the tumor, its supporting stroma, and the surrounding immununological milieu (19). As the highest failure rate occurs during phase II testing when clinical efficacy in humans is first directly tested, preclinical models that are better surrogates for human disease are needed (20). GEMMs possessing conditional alleles that recapitulate mutations known to be important in human disease provide an attractive and powerful alternative, as they recapitulate the full histologic, genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic spectrum of disease seen in human disease (21, 22). Indeed, numerous successful cancer discovery and validation efforts have been possible through the use of comprehensive comparative oncogenomic and oncoproteomic analyses (22–26). Furthermore, such GEMMs can be used to derive highly successful predictions of eventual therapeutic response in human disease (5, 27). Whereas GEMMs are excellent surrogates for human disease, they are more suited for specific hypothesis-driven efforts rather than high throughput screening. To address this deficiency, we wished to develop a composite platform comprised of 1) high throughput in vitro screening based on CRC GEMMs and 2) closely linked in vivo validation that faithfully recapitulates human disease.

Many CRC GEMMs utilize germline or tissue-wide modification of genes involved in human carcinogenesis that paradoxically results in a high multiplicity of predominantly small intestinal tumors (28). Whereas GEMM-derived cell lines have been described for models of lung and pancreatic cancer (29), CRC GEMM-derived cell lines have not. This may because the large tumor burden in most CRC GEMMs results in premature death, thereby precluding the isolation and characterization of distinct tumor material that is amenable to generation of viable cell lines. Here, we have characterized two novel CRC GEMMs that present with a very low multiplicity of large advanced primary colonic tumors, making these an ideal basis for derivation of cell lines to incorporate into our GEMM derived orthotopic model. We used primary colonic tumor tissue from these two GEMMs to successfully generate low passage cell lines that recapitulate many canonical features of human CRC. In addition, low-passage cell lines derived from primary tumors recapitulate this enhanced proliferative phenotype when propagated in vitro, as well as in subcutaneous space in vivo. Gene expression signatures generated from these low passage Kras mutant cell lines are highly concordant with several signatures associated with KRAS mutation, as well as enhanced proliferation, metastasis, and stem-cell signatures, providing evidence for common biology between our model system and CRC. Furthermore, our CRC GEMM expression signatures are highly enriched for biological functions and processes associated with human cancer, gastrointestinal disease, and altered metabolism. Taken together, these findings suggest that the cell lines derived from primary GEMM tumors recapitulate many canonical features of human CRC biology and are a robust foundation for our orthotpopic model.

Whereas traditional xenograft models suffer from complete species mismatch in the tumor microenvironment, our strategy permits engraftment into immunocompetent, syngeneic hosts. Multiple approaches to develop orthotopic transplant models in mice have been described, including cecal and colonic injections (30–32). Unfortunately, these strategies employ subepithelial injection of tumor cells into the supporting stroma, which is not the native microenvironment for CRC carcinogenesis. Here, we describe a method in which we disrupt the native colonic epithelium, thereby permitting robust and reproducible cell line engraftment in the colonic epithelial compartment. Further, our model allows for the development and reimplantation of syngeneic tumor cells using any number of genetic combinations. Limitations intrinsic to the model itself may include a lack of genetic heterogeneity due to the finite number of initial driver mutations built into the model, as well as, potential for the tumors themselves to manifest a limited level of intratumoral heterogeneity, as compared to human CRC counterparts. To better recapitulate such heterogeneity, implantation of a mixture of primary cell cultures that derive from independent tumor models could be implemented in the future.

there are limitations intrinsic to the model itself, including a lack of genetic heterogeneity due to the finite number of driver lesions built into the model, as well as potential for the tumors themselves to manifest a limited level of intratumoral heterogeneity compared to human CRC counterparts. Nonetheless, we have developed a platform that allows for the validation of findings from high throughput in vitro screens in an in vivo setting that recapitulates CRC carcinogenesis in its native environment.

Given the lack of success in generating selective pharmacological against oncogenic KRAS, several efforts have attempted to identify potential synthetic lethal targets (33–36). To this end, the Kras wild type and mutant models of CRC described and characterized herein will provide future functional screening efforts aimed at identifying and, more critically, validating (37, 38) such synthetic lethal targets in KRAS mutant CRC. In addition, the ability to transplant these low passage cell lines back into the relevant colonic microenvironment and reconstitute a colorectal tumor will provide an invaluable platform for future functional screening efforts to identify putative therapeutic targets using RNAi or genetically engineered gain-of-function approaches. Furthermore, we have demonstrated the feasibility of asking sophisticated hypothesis-driven gain-of-function and loss-of-function questions using relatively simple in vitro genetic manipulations that can be rapidly validated in vivo. In this manner, we can circumvent some of the limitations of traditional CRC GEMMs that require laborious targeting of embryonic stem cells and/or cumbersome mouse breeding.

Activation of oncogenes and/or loss of tumor suppressor genes such as KRAS (39), MYC (40), and TP53 (41) increase glucose uptake and lactate production. These observations are consistent with the ‘Warburg effect’ that stipulates that tumor cells rely mainly on aerobic glycolysis to generate ATP instead of the metabolically more efficient mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (12). Therefore, mutations in diverse oncogenic pathways may affect glucose utilization by tumor cells. Consequently, FDG-PET has been employed as a diagnostic tool to detect metabolically active foci, which are representative of cancer cell dissemination in the clinical setting (42). Given the prevalence of metabolic pathway enrichment in our transcriptome analysis, we wished to determine whether the activation of oncogenic Kras enhanced metabolic activity in our model system. In support of an altered metabolic state, our functional analyses found that Kras mutant cell lines demonstrate decreased in vitro OCR/ECAR ratios, increased in vitro and in vivo FDG-PET signal, and increased in vivo lactate production. These findings are consistent with a metabolic shift towards increased aerobic glycolysis, termed the Warburg effect (43), and are concordant with recent findings implicating a role for oncogenic KRAS in a shift toward increased glycolysis and glucose consumption (44) This shift in metabolism is thought to provide cancer cells with a growth advantage in the tumor microenvironment, (45), and it has been suggested that aerobic glycolysis can contribute to malignant transformation (46). Furthermore, this finding highlights the potential of FDG-PET for non-invasive discrimination between KRAS mutant and non-mutant CRC metastases. Thus, our Kras mutant GEMM model presents with several phenotypes of KRAS mutant CRC, including enhanced proliferation, heightened signaling through MAPK and PI3K pathways, and an increased propensity towards aerobic metabolism.

In conclusion, we present here the establishment of two genetically defined models of sporadic CRC biology, including one that displays several hallmark traits of KRAS driven CRC.

These findings provide evidence that this model system faithfully recapitulates human CRC, thereby making it a highly desirable platform for preclinical therapeutic target identification for KRAS CRC and subsequent in vivo validation.

Supplementary Material

TRANSLATIONAL RELEVANCE.

Treatment of colorectal cancer (CRC) with activating KRAS mutations represents a critical unmet clinical need. To evaluate the efficacy of experimental therapeutics in KRAS mutant CRC, we previously developed novel genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs) for Kras mutant and non-mutant sporadic CRC. To facilitate high throughput screening, we have generated low passage cell lines derived from our GEMM primary colonic tumors under defined conditions. Kras mutant and non-mutant tumor-derived cell lines demonstrated phenotypic differences in tumor growth, dependency on oncogenic signaling, and metabolism. Transcriptomic analysis revealed close intersection with human KRAS CRC biology. Furthermore, we developed an innovative approach to transplant our cell lines into the native colonic microenvironment of immunocompetent mice, resulting in rapid, reproducible, and tractable tumor formation. Taken together, these features provide a complementary platform for large-scale and comprehensive drug discovery efforts.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Sabine Tejpar for critical review of this manuscript.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Except for MS, LR, EC, JR, LL, PH, SL, GG, RB, RX, MV, and UM all other authors are either former or current employees of Pfizer.

GENE EXPRESSION DATA: All gene expression information is available at the Gene Expression Omnibus (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession number GSE39557.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

E.S. M and K.E. H conceived and designed the project. E.S.M., P.J. B., M.J. S., L.G. R, J. Y., E.M. C., J.R., L. L., P. H., S. Y. L., G. G., C. J., J. X., T. X., J.L., S. W., T. V., R.T. B., R.J. X., M.G. V., J. K. U. M., and K.E. H. performed the experiments, analyzed, and interpreted the data. E.S. M, P. J. B, M.J. S, and K.E. H wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Prenen H, Tejpar S, Van Cutsem E. New strategies for treatment of KRAS mutant metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:2921–6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DiMasi JA, Feldman L, Seckler A, Wilson A. Trends in risks associated with new drug development: success rates for investigational drugs. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;87:272–7. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taketo MM, Edelmann W. Mouse models of colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:780–98. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Markowitz SD, Bertagnolli MM. Molecular origins of cancer: Molecular basis of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2449–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hung KE, Maricevich MA, Richard LG, Chen WY, Richardson MP, Kunin A, et al. Development of a mouse model for sporadic and metastatic colon tumors and its use in assessing drug treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:1565–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908682107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roper J, Richardson MP, Wang WV, Richard LG, Chen W, Coffee EM, et al. The dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitor NVP-BEZ235 induces tumor regression in a genetically engineered mouse model of PIK3CA wild-type colorectal cancer. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25132. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arena S, Isella C, Martini M, de Marco A, Medico E, Bardelli A. Knock-in of oncogenic Kras does not transform mouse somatic cells but triggers a transcriptional response that classifies human cancers. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8468–76. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bild AH, Yao G, Chang JT, Wang Q, Potti A, Chasse D, et al. Oncogenic pathway signatures in human cancers as a guide to targeted therapies. Nature. 2006;439:353–7. doi: 10.1038/nature04296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sweet-Cordero A, Mukherjee S, Subramanian A, You H, Roix JJ, Ladd-Acosta C, et al. An oncogenic KRAS2 expression signature identified by cross-species gene-expression analysis. Nat Genet. 2005;37:48–55. doi: 10.1038/ng1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith JJ, Deane NG, Wu F, Merchant NB, Zhang B, Jiang A, et al. Experimentally derived metastasis gene expression profile predicts recurrence and death in patients with colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:958–68. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merlos-Suarez A, Barriga FM, Jung P, Iglesias M, Cespedes MV, Rossell D, et al. The intestinal stem cell signature identifies colorectal cancer stem cells and predicts disease relapse. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:511–24. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324:1029–33. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bos JL, Fearon ER, Hamilton SR, Verlaan-de Vries M, van Boom JH, van der Eb AJ, et al. Prevalence of ras gene mutations in human colorectal cancers. Nature. 1987;327:293–7. doi: 10.1038/327293a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amado RG, Wolf M, Peeters M, Van Cutsem E, Siena S, Freeman DJ, et al. Wild-type KRAS is required for panitumumab efficacy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1626–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.7116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lievre A, Bachet JB, Le Corre D, Boige V, Landi B, Emile JF, et al. KRAS mutation status is predictive of response to cetuximab therapy in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3992–5. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Roock W, De Vriendt V, Normanno N, Ciardiello F, Tejpar S. KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA, and PTEN mutations: implications for targeted therapies in metastatic colorectal cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:594–603. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siena S, Sartore-Bianchi A, Di Nicolantonio F, Balfour J, Bardelli A. Biomarkers predicting clinical outcome of epidermal growth factor receptor-targeted therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1308–24. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ledford H. Translational research: 4 ways to fix the clinical trial. Nature. 2011;477:526–8. doi: 10.1038/477526a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arrowsmith J. Trial watch: Phase II failures: 2008–2010. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:328–9. doi: 10.1038/nrd3439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frese KK, Tuveson DA. Maximizing mouse cancer models. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:645–58. doi: 10.1038/nrc2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maser RS, Choudhury B, Campbell PJ, Feng B, Wong KK, Protopopov A, et al. Chromosomally unstable mouse tumours have genomic alterations similar to diverse human cancers. Nature. 2007;447:966–71. doi: 10.1038/nature05886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carretero J, Shimamura T, Rikova K, Jackson AL, Wilkerson MD, Borgman CL, et al. Integrative genomic and proteomic analyses identify targets for Lkb1-deficient metastatic lung tumors. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:547–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faca V, Krasnoselsky A, Hanash S. Innovative proteomic approaches for cancer biomarker discovery. Biotechniques. 2007;43:279, 81–3, 85. doi: 10.2144/000112541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hung KE, Faca V, Song K, Sarracino DA, Richard LG, Krastins B, et al. Comprehensive proteome analysis of an Apc mouse model uncovers proteins associated with intestinal tumorigenesis. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2009;2:224–33. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin ES, Tonon G, Sinha R, Xiao Y, Feng B, Kimmelman AC, et al. Common and distinct genomic events in sporadic colorectal cancer and diverse cancer types. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10736–43. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Engelman JA, Chen L, Tan X, Crosby K, Guimaraes AR, Upadhyay R, et al. Effective use of PI3K and MEK inhibitors to treat mutant Kras G12D and PIK3CA H1047R murine lung cancers. Nat Med. 2008;14:1351–6. doi: 10.1038/nm.1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uronis JM, Threadgill DW. Murine models of colorectal cancer. Mamm Genome. 2009;20:261–8. doi: 10.1007/s00335-009-9186-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Collisson EA, Sadanandam A, Olson P, Gibb WJ, Truitt M, Gu S, et al. Subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and their differing responses to therapy. Nat Med. 2011;17:500–3. doi: 10.1038/nm.2344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fu XY, Besterman JM, Monosov A, Hoffman RM. Models of human metastatic colon cancer in nude mice orthotopically constructed by using histologically intact patient specimens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:9345–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.20.9345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tseng W, Leong X, Engleman E. Orthotopic mouse model of colorectal cancer. J Vis Exp. 2007:484. doi: 10.3791/484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zigmond E, Halpern Z, Elinav E, Brazowski E, Jung S, Varol C. Utilization of murine colonoscopy for orthotopic implantation of colorectal cancer. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28858. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Babij C, Zhang Y, Kurzeja RJ, Munzli A, Shehabeldin A, Fernando M, et al. STK33 kinase activity is nonessential in KRAS-dependent cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2011;71:5818–26. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barbie DA, Tamayo P, Boehm JS, Kim SY, Moody SE, Dunn IF, et al. Systematic RNA interference reveals that oncogenic KRAS-driven cancers require TBK1. Nature. 2009;462:108–12. doi: 10.1038/nature08460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luo J, Emanuele MJ, Li D, Creighton CJ, Schlabach MR, Westbrook TF, et al. A genome-wide RNAi screen identifies multiple synthetic lethal interactions with the Ras oncogene. Cell. 2009;137:835–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vicent S, Chen R, Sayles LC, Lin C, Walker RG, Gillespie AK, et al. Wilms tumor 1 (WT1) regulates KRAS-driven oncogenesis and senescence in mouse and human models. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:3940–52. doi: 10.1172/JCI44165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Naik G. Scientists’ Elusive Goal: Reproducing Study Results. Wall Street Journal. 2011 Dec 02;2011 [cited; Available from: http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970203764804577059841672541590.html. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chan DA, Giaccia AJ. Harnessing synthetic lethal interactions in anticancer drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:351–64. doi: 10.1038/nrd3374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flier JS, Mueckler MM, Usher P, Lodish HF. Elevated levels of glucose transport and transporter messenger RNA are induced by ras or src oncogenes. Science. 1987;235:1492–5. doi: 10.1126/science.3103217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fan Y, Dickman KG, Zong WX. Akt and c-Myc differentially activate cellular metabolic programs and prime cells to bioenergetic inhibition. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7324–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.035584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matoba S, Kang JG, Patino WD, Wragg A, Boehm M, Gavrilova O, et al. p53 regulates mitochondrial respiration. Science. 2006;312:1650–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1126863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Som P, Atkins HL, Bandoypadhyay D, Fowler JS, MacGregor RR, Matsui K, et al. A fluorinated glucose analog, 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (F-18): nontoxic tracer for rapid tumor detection. J Nucl Med. 1980;21:670–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956;123:309–14. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neuzil J, Rohlena J, Dong LF. K-Ras and mitochondria: Dangerous liasons. Cell Res. 2011 doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gatenby RA, Gillies RJ. Why do cancers have high aerobic glycolysis? Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:891–9. doi: 10.1038/nrc1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kondoh H, Lleonart ME, Gil J, Wang J, Degan P, Peters G, et al. Glycolytic enzymes can modulate cellular life span. Cancer Res. 2005;65:177–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.