Abstract

Targeting CD14+ dermal-derived dendritic cells (DDCs) is a rational approach for vaccination strategies aimed at improving humoral immune responses, because of their natural ability to stimulate naïve B-cells. Here, we show that CD14+ DDCs express mRNA for TLRs 1–9, but respond differentially to single or paired TLR ligands. Compared to single ligands, some combinations were particularly effective at activating CD14+ DDCs, as shown by enhanced expression of B-cell stimulatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-10 and TNF-α) and more pronounced phenotypic maturation. These combinations were Resiquimod (R-848) plus Polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (Poly(I:C)); R-848 plus LPS; Pam3CSK4 plus Poly(I:C); LPS plus Poly(I:C). We also found that selected TLR ligand pairs (R-848 plus either LPS or Poly(I:C)) were superior to individual agents at boosting the inherent capacity of CD14+ DDCs to induce naïve B-cells to proliferate and differentiate into CD27+ CD38+ B-cells that secrete high levels of IgG and IgA. When treated with the same TLR ligand combinations, CD14+ DDCs also promoted the differentiation of Th1 (IFN-γ-secreting) CD4+ T-cells, but not of Th2 or Th17 CD4+ T-cells. These observations may help to identify adjuvant strategies aimed at inducing protective immune responses to various pathogens, including but not limited to HIV-1.

Keywords: Vaccination, TLR ligands, dendritic cells, B-cells

Introduction

Vaccination is medical science’s strongest weapon against the spread of infectious diseases. There remain, however, many pathogens for which there are no effective vaccines, including most parasites and HIV-1. Traditional vaccines rely on live attenuated or inactivated whole microorganisms and do not require adjuvants; their naturally immunostimulatory microbial components mimic what happens during infections. Subunit vaccines consisting of pathogen proteins offer safety and production advantages and are particularly valuable for inducing B-cell responses, including virus-neutralizing Abs (NAbs). However, proteins are generally poorly immunogenic by themselves and require adjuvants to enhance Ab production (1). Until recently, the only adjuvant approved for human use in the USA was Alum, which is effective at boosting Ab titers in a Th2-biased response (2). Effective vaccines against, for example, HIV-1 and malaria are likely to require both humoral and T-cell immunity, particularly Th1 responses. Consequently, considerable effort is being applied to developing new adjuvants that can promote protective immunity via both Abs and T-cells.

TLR ligands are the basis of a new generation of adjuvants (1, 3, 4). TLRs are a class of pattern-recognition receptors that sense invading pathogens by recognizing conserved pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). Each TLR is triggered by a distinct set of microbial products; thus, TLR3 responds to double-stranded (ds)RNA (mimicked by Poly(I:C)); TLR4 to LPS; and TLRs 7 and 8 to stimulatory single-stranded RNA (5, 6). The combination of Alum with a non-toxic LPS derivative (Monophosphoryl Lipid A (MPL®)) comprises the active component of the recently licensed AS04 adjuvant used in the Cervarix® and Fendrix® vaccines for human papilloma virus and hepatitis B virus, respectively (1). Most TLRs are present at the cell surface, enabling detection of PAMPs such as LPS that are accessible at that site, whereas microbial nucleic acids are sensed by endosomal TLRs (3, 7, 8 and 9) after uptake by the cell (5). The coupling of TLRs to signal transduction pathways is, except for TLR3, mediated via the MyD88 adaptor protein; TLR3, and also TLR4, link to the adaptor protein Toll/IL-1 receptor domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β (TRIF) (7).

Dendritic cells (DCs), the most potent of professional APCs, are unique in their ability to prime naïve CD4+ T-cells (8). Ligation of TLRs triggers DC maturation, a complex process characterized by migration to secondary lymphoid tissues, up-regulation of MHC and co-stimulatory molecules, and secretion of Th-polarizing cytokines that are essential for priming naïve CD4+ T-cells. This chain of events effectively links innate and adaptive immune responses. DCs are remarkable for their plasticity; the nature of the pathogen they encounter in the periphery determines how they respond (9–13). For example, when myeloid DCs (mDCs) are triggered via TLRs 4, 7 and 8 in vivo, they secrete abundant IL-12p70 and promote naïve CD4+ T-cells to differentiate into IFN-γ-expressing Th1-cells (13). By activating macrophages, NK cells and CTLs, IFN-γ drives cellular immune responses against intracellular pathogens and stimulates B-cells to produce opsonizing Abs. Alternatively, DCs triggered via TLR2 (through heat killed yeast or zymosan particles) secrete IL-10, which favors Th2-cell differentiation and drives humoral responses (14). Recently, LPS-stimulated DCs were shown to induce the differentiation not only of Th1-cells, but also of Tfh-cells (15). The latter, defined by expression of IL-21, CXCR5, Bcl-6, ICOS and CD200, are highly specialized providers of B-cell help (16).

As well as priming CD4+ T-cells with B-cell helper function, mDCs can also directly promote B-cell differentiation by secreting various stimulatory cytokines, including IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, TGF-β, A Proliferation Inducing Ligand (APRIL) and B-cell-activating factor (BAFF) (17–21). Indeed, DC-derived IL-12 is a critical factor in the differentiation of naïve B-cells into IgM-secreting plasma cells, synergizing with the IL-6/soluble IL-6Rα-chain complex (22).

The skin is a logical site for vaccine delivery because it contains abundant immature DCs (23–25). One skin DC population consists of the prototypic epidermal Langerhans’ cells (LCs), which are potent stimulators of naïve T-cells (26–29). The dermis contains both CD1a+ dermal DCs (DDCs) and a minor population of CD14+ DDCs (30), the functions of which are less known. A clearer understanding of the biology of human skin DCs would help vaccine design, but research in this area has been hampered by the difficulty of isolating enough cells for functional assessment. To overcome this problem, skin-like DC subsets can be generated by culturing CD34+ progenitors with GM-CSF and TNF-α (31, 32). Akin to their in vivo counterparts, “LC-like” DCs are potent stimulators of both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells (26, 29). Strikingly, the resulting CD14+ “dermal-like” DCs have a unique capacity to induce naïve B-cells to differentiate into IgM-secreting cells, via CD40 triggering and IL-2 (32). Furthermore, skin-derived CD14+ DDCs prime Tfh-like cells that can induce class switching in B-cells (26). Thus, the initiation of humoral responses and cellular responses appears to be regulated by CD14+ DDCs and LCs, respectively.

Knowing how TLR ligands affect the functionality of skin DCs would improve our understanding of their adjuvant capabilities. Combining selected TLR ligands induces stronger responses, which may be particularly relevant for poorly immunogenic subunit proteins such as HIV-1 gp120 (33, 34). For example, including TLR4 and TLR7 ligands with Ag-containing nanoparticles has a synergistic effect on the induction of NAbs in mice (35). In another in vivo study, activating DCs through both TLR3 and TLR9 strongly increased Ag-specific CD8+ T-cell responses (36). Finally, TLR3 and TLR4 synergize with TLR7/8 to induce higher levels of bioactive IL-12p70 in human monocyte-derived DCs (MoDCs) in vitro, which in turn increases the extent of Th1-cell differentiation (37, 38).

How TLR ligands cooperate to activate skin DCs has not yet been studied. Here, we have investigated how human CD14+ DDCs respond to selected TLR ligand combinations, by measuring their phenotypic maturation, release of cytokines and capacity to stimulate naïve B and CD4+ T-cells. We identified two TLR ligand combinations (Poly(I:C) plus R-848 and LPS plus R-848) that reliably activate CD14+ DDCs to both stimulate naïve B-cells and induce Th1 differentiation. Either combination may be a suitable adjuvant for an intradermal vaccination strategy aimed at inducing both Ab and cell-mediated responses.

Materials and Methods

Collection and preparation of human skin

Normal human skin samples were obtained from the New York Firefighters’ skin bank, New York Presbyterian Hospital, New York, NY. Skin was removed from cadaveric donors within 12 h post mortem (median age 45 years; range, 17–58 years). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants’ next of kin. Skin was rinsed twice in ice-cold PBS containing 200 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin (HyClone; Perbio Sciences) and 200 μg/ml of gentamicin (Sigma-Aldrich). The rinsed skin was then used to prepare explants (for collection of migratory DCs), or enzyme treated (for isolation of tissue-resident DCs).

Isolation of migratory skin CD14+ DDCs and CD1a+ DCs

In all experiments (unless otherwise indicated), CD14+ DDCs were isolated from migratory cells. Skin explants composed of epidermis and a thin layer of dermis were cultured, epidermal side up, in 100-mm Petri dishes (Falcon) in RPMI 1640 medium (Cellgro, Mediatech Inc.) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated (HI) normal human serum (from human male AB plasma; Sigma-Aldrich), 20 mM HEPES, 2 mM L-glutamine (Gibco, Life Technologies), 200 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin and 200 μg/ml gentamicin. Total skin migratory cells were collected ~24 h after the skin explant cultures were started. Migratory cells (DCs and T-cells) were removed from the Petri dishes after a 24-h culture, passed through 70-μm filters and washed twice in sterile ice-cold PBS containing antibiotics. Dead cells (typically 2–5% of migratory cells) were removed using a Dead Cell Removal Kit (Miltenyi Biotech). Viable cells were collected as the negative (unlabeled) flow-through from Large Cell Isolation Columns, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Miltenyi Biotech). CD14+ CD1a− DDCs were isolated by positive selection using CD14-labeled microbeads; CD1a+ CD14− DCs were subsequently isolated from the CD14-negative fraction using CD1a-labeled microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech). A second column was used to further purify the positive fractions to > 94%. The viability of DCs was assessed following staining with 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) and annexin V according to the manufacturer’s instructions (BD Biosciences). For assessing TLR mRNA expression, migratory DCs were isolated by FACS using a Becton Dickinson Vantage Cell Sorter, after staining with monoclonal Abs (MAbs) against CD1a (clone HI149), CD14 (clone 61D3) and HLA-DR (clone G46-6).

Isolation of tissue-resident skin DCs

To isolate epidermal LCs and CD1a+ DDCs, skin was cut into 5 × 5 cm pieces and treated overnight at 4°C with 2.4 U/ml dispase (Invitrogen) in RPMI 1640 medium, followed by incubation for 1 h at 37°C to allow manual separation of the epidermis from the dermis. The epidermis was carefully separated from the dermis using sterile forceps. Single-cell epidermal suspensions were prepared by gently pipetting epidermal fragments before passage through a 70 μm filter to remove debris. Dermal sheets were cleared of any residual epidermis and digested for another 1–2 h (at 37°C) with 0.2% Clostridium histolyticum collagenase (Roche). The resulting single-cell suspension was overlaid on an equal volume of Lymphocyte Separation Medium (1.077–1.08 g/ml; Cellgro, Mediatech Inc.) and centrifuged at 400 g for 30 min at room temperature (RT). The cells were washed twice in ice-cold MACS buffer (PBS containing 5 mM EDTA (Sigma-Aldrich), 1% HI human serum, 200 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin, 200 μg/ml gentamicin) prior to isolation of CD1a+ DCs from both epidermal cell (i.e., LCs) and dermal cell suspensions by positive selection using CD1a-labeled microbeads and Large Cell Isolation columns. After two passages through the columns, the purity of cells with the CD1a+ HLA-DR++ phenotype was > 94%.

For some experiments, CD14+ DDCs were isolated from freshly digested dermal cells as described elsewhere (39). Briefly, skin was treated for 1 h at 37°C with 1 mg/ml dispase in RPMI 1640. The epidermal tissue was removed and the dermal sheets were then cut into 0.5-cm squares and incubated for 8–12 h at 37°C with 0.8 mg/ml collagenase in RPMI 1640 containing 10% HI FBS (Gibco, Life Technologies). Single-cell suspensions were prepared by filtration through 70-μm filters, followed by two washes in RPMI 1640, enrichment of live cells after density centrifugation with Lymphocyte Separation Medium (as before) and two further washes in PBS containing 2.5% HI FBS. Dermal-derived cells were stained with MAbs specific for CD45 (clone 2D1), CD14 (clone 61D3), HLA-DR (clone L243), CD1c (L161) and CD1a (HI149), followed by two washes in PBS containing 2.5% FBS and then stained with 7-AAD. Live CD14+ DDCs were identified as 7-AAD− CD45+ HLA-DR++ CD14+ CD1a− SSClo CD1c+ DCs and isolated to >95% purity by FACS.

Propagation of MoDCs

MoDCs were generated from peripheral blood monocytes purified from human PBMCs. Human blood samples from healthy donors were obtained from the New York City Blood Bank, Long Island City, NY. PBMCs were obtained after density centrifugation with Lymphocyte Separation Medium (as described above) and CD14+ monocytes were positively selected to a purity >96% using CD14-labeled microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech). Monocytes were seeded into 6-well plates (2 × 106 cells/ml) and maintained in RPMI 1640 containing 2 mM L-glutamine, 200 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin, 10% HI human serum and 1000 U/ml recombinant GM-CSF (Biosource) and IL-4 (R & D Systems) for 6 days. Culture medium was replaced every 2 days with fresh medium supplemented with cytokines. On day 6, the non-adherent cell fraction was harvested and their phenotype was analyzed by flow cytometry.

Isolation of naïve B-cells and naïve allogeneic CD4+ T-cells

CD8+ T-cell-depleted PBMCs were isolated by incubation with a human CD8-depletion cocktail (RosetteSep®) followed by density centrifugation with Lymphocyte Separation Medium (see above). Prior to the isolation of naïve B-cells, residual T-cells were first depleted using CD3-labeled microbeads, with CD3 negative fractions collected from LD depletion columns (Miltenyi Biotech). Naïve B-cells and naïve CD4+ T-cells were purified to >95% by negative selection using the appropriate isolation kits (Miltenyi Biotech). Naïve B-cells were defined as CD19+ CD20+ HLA-DR+ CD27−, naïve CD4+ T-cells as CD3+ CD4+ CD45RO− CD27+.

DC stimulation

TLR ligands (InvivoGen unless otherwise stated) were used at the following concentrations to stimulate CD14+ DDCs (~2 × 104 cells) and MoDCs (~105 cells) in 96-well and 48-well flat-bottomed plates, respectively: Pam3CSK4 (0.2 μg/ml); Peptidoglycan (PGN) (2 μg/ml); Lipoteichoic acid (1 μg/ml); Zymosan (10 μg/ml); Poly(I:C) (30 μg/ml); LPS from Salmonella typhimurium (Sigma-Aldrich) (100 ng/ml); Ultrapure Flagellin (5 μg/ml); R-848 (5 μg/ml); CpG-2395 (type C CpG; 1 μM). In some studies, LPS-EB Ultrapure from Escherichia coli 0111:B4 (100 ng/ml) was used.

CD14+ DDC and naïve B-cell co-cultures

Naïve B-cells were added to skin DCs at ratios ranging from 2:1 – 100:1 (see Results) and cultured in 96-well U-bottomed plates for 5 days (BrdU and CFSE proliferation assays), 7 days (B-cell phenotypic analysis) or 14 days (Ig quantification). Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% HI FBS, 20 mM HEPES, MEM non-essential amino acids (Gibco, Life Technologies), 2 mM L-glutamine, 200 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin and 200 μg/ml gentamicin (B-cell Complete Medium). Cultures were also supplemented with recombinant IL-2 (20 U/ml; Roche) and CD40L (200 ng/ml; Enzo Laboratories). In some experiments (i.e. those not involving TLR ligands; see Results), cultures were also supplemented with recombinant IL-10 (10 ng/ml; R & D Systems). In the CFSE proliferation assays, F(ab′)2 anti-human IgM/IgG/IgA (anti-Ig; 2.5 μg/ml; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) was added, as an alternative to CD40L, to induce BCR ligation. As controls, naïve B-cells were cultured without DCs in the presence of IL-2, (± IL-10) and CD40L, or with anti-Ig alone.

To assess the functional capacity of TLR-ligand activated CD14+ DDCs, freshly isolated cells were directly added to naïve B-cells (DDC : B-cell ratios varying from 1:5 – 1:100) and stimulated in the continuous presence of TLR ligands. For comparison, naïve B-cells were stimulated with the same TLR ligands (plus CD40L and IL-2, or anti-Ig), but in the absence of CD14+ DDCs. All cultures were supplemented with CD40L and IL-2, or with anti-Ig (CFSE assays only). In some studies, CD14+ DDCs were pre-activated for 12 h with TLR ligands, then washed twice (to remove TLR ligands) with B-cell Complete Medium before co-culturing with naïve B-cells.

Transwell experiments were conducted using 96-well plates with transwell (0.4 μm pore-size) inserts (Costar). Naïve B-cells (6.25 × 105) were seeded in the bottom well (final volume 235 μl) while CD14+ DDCs (2 × 104 (1:30 ratio) and 1.25 × 105 (1:5 ratio)) were added to the upper chamber (final volume 75 μl) in the presence of CD40L, IL-2 ± IL-10. For comparison, the same numbers of CD14+ DDCs and naïve B-cells were directly co-cultured in adjacent wells. B-cell cultures without CD14+ DDCs (but with CD40L, IL-2, ± IL-10) served as negative controls, and were maintained for 5 days (for assessing proliferation), 7 days (for determining phenotype) or 14 days (for quantification of Ig release). In some experiments, neutralizing mouse MAbs (all from R & D Systems) against IL-6 (clone 6708), TNF-α (clone 1825) or IL-10 (clone 25209) were added to DC-B-cell co-cultures at 10μg/ml. Appropriate isotype matched (IgG1 or IgG2B) control MAbs were tested for comparison.

MLRs

Naïve CD4+ T-cells (CD3+ CD4+ CD45RO− CD27+) were added directly to cutaneous DCs in 96-well flat-bottomed plates at different stimulator to responder cell ratios (ranging from 1:5 – 1:20) in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% HI human serum. After 5 days of culture, the cells were pulsed with BrdU for 5 h to allow quantification of CD4+ T-cell proliferation. ELISAs were used to quantify cytokine secretion (IFN-γ and IL-5) in co-culture supernatants on day 6 or 7 (outlined in the text), in comparison to supernatants from T-cell or DC cultures.

To assess the functional capacity of TLR ligand-stimulated CD14+ DDCs, DDCs were first stimulated for 12 h and then washed before addition of naïve CD4+ T-cells (T-cell to DDC ratio, 25:1). After culturing for 6 days, the MLR supernatants were removed (see above). For detecting cytokine production at the cellular level, resting CD4+ T-cells were restimulated with 100 ng/ml PMA and 1 μg/ml ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 6 h, with brefeldin A (1 μg/ml) also present for the last 4 h. For intracellular cytokine staining, CD4+ T-cells were first stained with an anti-CD3 MAb (clone HIT3a), washed and then permeabilized using the Cytofix/Cytoperm™ kit (BD Biosciences), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were then incubated for 20 min at RT with MAbs specific for IFN-γ (clone 25723.11), IL-17 (clone SCPL1362) or with isotype control MAbs (murine IgG2b-APC (clone 27–35) and IgG1-PE (clone MOPC-21)).

Proliferation assays

B-cell and CD4+ T-cell proliferation were assessed using the BrdU (colorimetric) cell proliferation ELISA according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Roche). Briefly, after a 5-day co-culture with DC subsets, cells were transferred to 96-well flat-bottomed plates, pulsed for 5 h with 10 μM BrdU, centrifuged at 300 × g for 10 min at RT, dried at 60°C for 1 h, fixed and labeled. Absorbance was measured in an ELISA reader at 450 nm, with data presented as mean O.D. values (± SEM) from triplicate wells.

Alternatively, B-cell proliferation was measured using a CFSE dilution assay. Purified naïve B-cells (1 × 106/ml in PBS with 10% FBS) were labeled with 0.5 μM CFSE (Molecular Probes) for 7 min at 37°C and washed three times with RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS. CFSE-labeled cells were harvested after 5 days of culture, and stained with allophycocyanin-labeled CD19 to allow the exclusion of residual CD14+ DDCs. Proliferation was measured by a LSR II cytometer, with the data analyzed by Flowjo™ software (Tree Star).

Phenotypic analysis by flow cytometry

Skin DC subsets were phenotyped by 5-color flow cytometry using MAbs against CD1a (clone HI149), CD14 (clone 61D3), CD11c (clone B-ly6), CD40 (clone 5C3), CD45 (clone 2D1), CD80 (clone L307.4), CD83 (clone HB15e), CD86 (clone IT2.2), CD207 (clone DCGM4) and HLA-DR (clone G46-6). Appropriate Ig isotype controls were always included to determine non-specific staining. B-cells were analyzed on day 7 of the co-culture, using MAbs against CD19 (clone H1B19), CD20 (clone 2H7), CD27 (0323), CD38 (clone HIT2) and HLA-DR (clone G46-6). CD4+ T-cells were analyzed after 6 days co-culture using MAbs against CD3 (clone HIT3a), CD4 (clone SK3), CD45RO (clone UCHL1), CD27 (clone 0323), and CD62L (clone DREG56). Non-specific MAb binding was prevented by adding 10% human serum for 30 min on ice to block Fc receptors. Pre-titrated MAbs were then added for 30 min (on ice). Cells were washed twice in ice-cold buffer (PBS plus 2.5% FBS), fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde and analyzed with the LSR II cytometer and Flowjo™ software.

Immunoglobulin quantification

After 14 days of co-culture, supernatants were removed and screened for IgM, IgA and IgG using ELISA kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Bethyl Laboratories). Absorbance was measured using an ELISA reader (Molecular Devices) at 450 nm, with data presented as means ± SEM of values from duplicate wells.

Quantification of cytokines in supernatants

Following cell stimulation, supernatants were harvested and stored at −80°C until analysis. The cytokine content of duplicate samples was quantified using ELISA kits: IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12p40, IL-12p70, TNF-α and IFN-γ (BD OptEIA ELISA kits; BD Biosciences); IL-5 (R & D Systems). Endpoints were determined using a Molecular Devices Emax microplate reader. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm, with data presented as means ± SEM of values from duplicate wells. In some experiments, a multiplex (MSD 7-spot) system was used to quantify IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12p70, TNF-α and IFN-γ.

Analysis of synergistic effects of TLR ligands

Several factors precluded calculations of concentration-based synergy indices for the TLR ligand combinations (40, 41). Cytokine secretion cannot be expressed as a fraction of a shared maximum for the different stimuli; sometimes one or both components of a combination had no effect when used as single agents; the wide titration ranges did not elicit effects that increased monotonously from baseline to a plateau; and the curves often peaked for both individual agents and their combinations. As an alternative, we analyzed synergy in extent, taking advantage of the near-linearity of the pre-peak dose-effect curves. Under such conditions, the effects of the individual stimuli can be summed as a criterion for additivity (40). Thus, we calculated the ratio between the highest cytokine response elicited by combined stimuli and the sum of the responses to the two individual agents at their constituent concentrations. These ratios were based on repeat measurements of each response with little to no variation, although there were too few replicates to allow a statistical evaluation. A ratio > 1 is indicative of synergy, = 1 of additivity, and < 1 of antagonism. When only one of the agents, or neither, is effective on its own but the combination gives a ratio > 1, the respective terms potentiation and coalism can be applied. Apart from the mathematical applicability of effect summation (40), it is noteworthy that, when the secretion of the same cytokine is stimulated by the independent ligation of distinct receptors, the combined non-interactive responses should be the sum of the individual responses. When the combined responses exceed the sums, this could indicate crosstalk between the receptors; when weaker, it could mean that the cytokine production capacity of the cell has been exceeded. In this special situation, effect summation is arguably justified as an additivity criterion.

RT-PCR reaction conditions

Total RNA was isolated from highly purified DC subsets using RNAeasy Mini Spin Columns (Qiagen™) as recommended by the manufacturer. Contaminating DNA was removed using the on-column DNase digestion kit (Qiagen™). Secondary RNA structure was denatured by heating for 5 min at 70°C. First-strand cDNA synthesis was carried out for 1 h at 37°C in a 20 μl total volume containing 25 μg/ml random primers, 0.5 mM deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs), 5 mM DTT, 40 U of RNase Inhibitor and 200 U of Murine Moloney Leukemia Virus reverse transcriptase (M-MLV) in 1 × M-MLV buffer (Promega), followed by denaturation at 70°C. Amplification of the housekeeping gene Hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyl transferase (HPRT) was carried out for 35 cycles (94°C for 60 s, 55°C for 60 s, 72°C for 60 s), followed by a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min, to confirm that genomic DNA was removed and that amplifiable material was present prior to quantitative RT-PCR analysis. The HPRT forward primer was: 5′-CAG TCA ACA GGG GAC ATA AAA-3′, the reverse primer was: 5′-TGA ATC CTC ATC TTA GGC TTT G-3′. PCR reaction mixtures consisted of 2 μl of cDNA, 20 pmol of each oligonucleotide primer (Sigma–Genosys); 200 μM of each dNTP and 2.5 U Taq polymerase (Promega) in 1 × buffer (50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 9.0), 1.5 mM MgCl2; Promega). TLR primers were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Taqman® assays (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies) were performed in triplicate using commercially available reagents (inventoried assays) to quantify the expression of the following genes: GAPDH (Hs0275899_g1); BAFF (Hs00198106_m1); APRIL (Hs00601664); TGF-β (Hs00998133_m1); TLR1 (Hs00413978_m1); TLR2 (Hs01872448_s1); TLR3 (Hs01551078_m1); TLR4 (Hs00152939_m1); TLR5 (Hs01920773_s1); TLR6 (Hs00271977_s1); TLR7 (Hs01933259_s1); TLR8 (Hs00152972_m1); TLR9 (Hs00370913_s1). Reactions were prepared in a 384-well plate μl containing 1 × Taqman® reaction mix and 0.5 μl Taqman® gene expression assay solution (containing a FAM dye-labeled minor groove binder probe), using a 7500 Real-Time PCR machine (Applied Biosystems). The ΔΔCT method was applied to calculate the relative gene expression (in arbitrary units), compared to the universally expressed housekeeping gene GAPDH, using the formula: ΔCt = Ct of target gene – Ct of GAPDH; ΔΔCt = ΔCt(sample) - ΔCt(calibrator). The resulting values were converted into arbitrary (normalized) units: 2−ΔΔCt.

Data analysis

Differences between 2 groups were analyzed by the Paired Student t test. Statistical analysis was performed using Prism Version 5 (GraphPad) software. A P value < .05 was considered to be significant.

Results

Isolation and characterization of human skin DC subsets

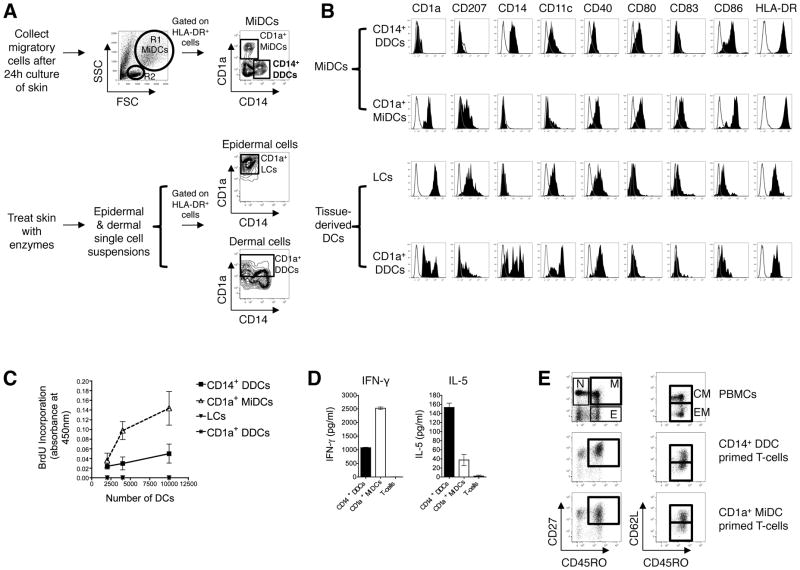

Before functionally comparing human CD14+ DDCs with other cutaneous DC subsets, we determined the phenotype of isolated DC populations to assess their relative maturation. Although FACS can be used to isolate CD14+ DDCs directly from digested dermis without contamination by dermal CD14+ macrophages (39), we were unable to isolate sufficient CD14+ DDCs for large-scale assays using this method. Instead, we cultured skin explants for 24 h, without enzyme treatment, to allow CD14+ DDCs to spontaneously migrate into the medium through the dermal afferent lymphatic system, and then purified the cells using CD14 microbeads. We found that this method also avoids contamination by dermal CD14+ macrophages, and that the purified CD14+ DDCs behave similarly to DDCs isolated by FACS (see below). Migratory DCs (MiDCs) are easily identified by their large size and granularity (Fig. 1A, top panel). Migratory lymphocytes are small and non-granular (Fig. 1A) and comprise mostly (>80%) activated memory (HLA-DR+ CD45RO+) T-cells (not shown). Three MiDC subsets were identified by CD14 and CD1a surface expression: CD14+ CD1a− DCs (henceforth referred to as CD14+ DDCs), CD1a+ CD14− DCs and CD14− CD1a− DCs (28). In some experiments, CD1a+ epidermal LCs and dermal CD1a+ DCs were isolated after treating skin with enzymes (Fig. 1A, bottom panel).

FIGURE 1. Purification, characterization and allogeneic CD4+ T-cell stimulatory function of CD14+ DDCs.

(A) (Top): Migratory cells were collected after a 24-h culture of skin explants. MiDCs are identified by their large size (FSChi) and granularity (SSChi) (R1) compared to migratory lymphocytes (R2: FSClo SSClo). According to the surface expression of CD14 and CD1a, three subsets of HLA-DR+ MiDCs are identified: CD14+ CD1a− DDCs; CD1a+ CD14− MiDCs and CD14− CD1a− DCs. CD14+ DDCs and CD1a+ MiDCs were isolated using CD14 and CD1a microbeads (MACS), respectively. (Bottom): LCs and dermal CD1a+ HLA-DR+ DCs were enriched following overnight treatment with dispase, separation of epidermal and dermal tissue, further collagenase treatment of dermal tissue and then isolation of DCs with CD1a microbeads. Dot plots show CD1a+ CD14− LCs and CD1a+ CD14+/− DDCs contained within epidermal and dermal digested tissue, respectively, after sequential gating on FSChi SSChi, CD45+, HLA-DR+ cells.

(B) Phenotype of isolated cutaneous DC subsets. DCs were gated based on their large size and granularity and their high expression of MHC class II (HLA-DR), and analyzed for their expression of CD1a, CD207 (langerin), CD14, CD11c, CD40, CD80, CD83 and CD86. One representative study of four is shown. Tissue-extracted LCs are characterized by high level expression of CD1a and langerin (CD207) but do not express CD14. Dermal CD1a+ DCs are heterogeneous, with variable levels of CD1a and langerin. CD1a+ CD14− MiDCs contain langerin-expressing DCs, whereas CD14+ DDCs do not.

(C) Proliferation of allogeneic naïve CD4+ T-cells following priming with graded numbers of skin DC subsets was assessed by BrdU incorporation after 5 days stimulation. Data are presented as mean O.D values ± SEM of triplicate wells from one representative experiment of three.

(D) Cytokine secretion by responder allogeneic CD4+ T-cells following 6 days allo-stimulation with CD14+ DDCs (black bars) and CD1a+ MiDCs (white bars). The Th-derived cytokines IFN-γ and IL-5 were quantified in MLR supernatants by ELISA. Data are presented as means ± SEM of duplicates of one representative experiment of three.

(E) Phenotypic analysis of CD4+ T-cells following a 6-day co-culture with allogeneic migratory CD14+ DDCs and CD1a+ DCs. Primed CD4+ T-cells were defined as CD45RO+ CD27+ memory (M) and CD45RO+ CD27− effector (E) T-cells. (N = naïve). Memory CD4+ T-cells were further defined as either CD62L+ central memory (CM) or CD62L− effector memory (EM) cells.

MiDCs express higher levels of CD80, CD86 and HLA-DR than tissue-derived LCs and dermal CD1a+ DCs, which is consistent with a more mature phenotype (Fig. 1B). However, we confirmed that CD14+ DDCs are phenotypically more immature than both CD1a+ MiDCs (which include both migratory LCs and dermal CD1a+ DCs) (Fig. 1B) and CD1a− CD14− MiDCs (data not shown), as judged by their lower expression of HLA-DR, CD40, CD80, CD83 and CD86 (28). Since migratory CD14+ DDCs are phenotypically semi-immature, we judged them to be particularly suitable for studying the effects of TLR ligands on the maturation process. Prior to functional assessment of CD14+ DDCs, we validated that the purification procedure did not compromise their viability by staining cells with 7-AAD and annexin V: 95% of purified CD14+ HLA-DR++ cells were 7-AADneg annexin Vneg (Supplementary Fig. 1A).

Cutaneous DC subsets have different capacities to polarize CD4+ T-cells

We next compared the capacity of human skin-derived DC subsets to stimulate naïve allogeneic CD4+ T-cells. Pure populations of naïve CD4+ T-cells (>95%) were freshly isolated from PBMCs (Supplementary Fig. 1B). DC subsets were isolated as described previously. We found that CD14+ DDCs were weaker than CD1a+ MiDCs at stimulating naïve CD4+ T-cell proliferation (Fig. 1C), but stronger than both freshly isolated LCs and dermal CD1a+ DCs; the rank order is consistent with the relative maturation of the DC subsets (Fig. 1B). Consistent with previous observations (28), CD14+ DDCs were weaker inducers of Th1 (IFN-γ secreting) cell differentiation but more strongly biased the process towards a Th2-type (IL-5 secreting) phenotype; the outcome was a mixed Th1/Th2 response (Fig. 1D). Both MiDC subsets induced the differentiation of central memory (CD45RO+ CD27+ CD62L+) and effector memory (CD45RO+ CD27+ CD62L−) CD4+ T-cells (Fig. 1E).

CD14+ DDCs are more potent stimulators of naïve B-cells than other cutaneous DCs

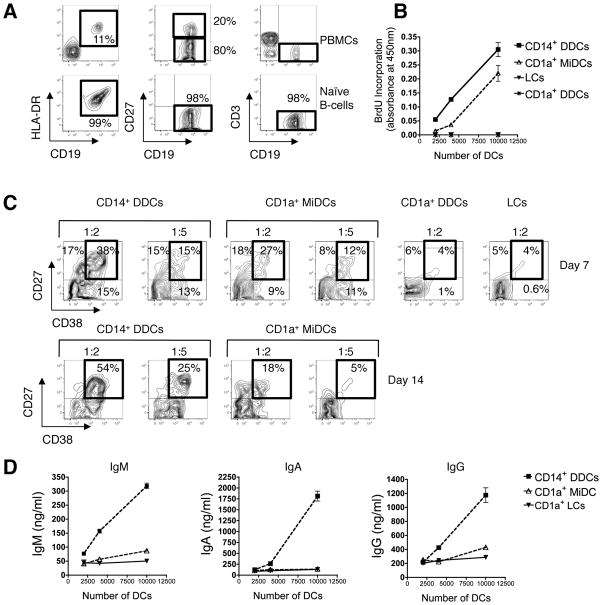

We next assessed the natural capacity of CD14+ DDCs to directly stimulate naïve B-cells, as measured by proliferation, differentiation and Ig class-switching. As blood from the skin donors was unavailable, we isolated naïve B-cells from PBMCs of other individuals, verifying that B-cell preparations were free of contaminating allogeneic (CD4+) T-cells (Fig. 2A). Preliminary experiments showed that skin-derived CD14+ DDCs were capable of inducing naïve B-cells to proliferate at low levels in the presence of CD40L alone, a response that was increased when IL-2 was also added (Supplementary Fig. 2). The most robust effect of CD14+ DDCs upon naïve B-cell proliferation and Ig secretion was seen when CD40L, IL-2 and IL-10 were all present in the cultures (Supplementary Fig. 2A and 2B), consistent with previous reports using CD34+ progenitor cell generated “skin-like” DCs (42). In addition, migratory CD14+ DDCs were functionally comparable to CD14+ DDCs that were isolated directly from dermis, in respect of their ability to induce naïve B-cells to proliferate (Supplementary Fig. 2C and 2D).

FIGURE 2. CD14+ DDCs are more efficient than other cutaneous DC subsets at stimulating naïve B-cells to proliferate and differentiate into Ig-secreting B-cells.

(A) Highly enriched naïve B-cells (CD19+ HLA-DR+ CD27−), free from allogeneic CD3+ CD4+ T-cells, were isolated from healthy donors’ PBMCs by negative selection using magnetic microbeads. Numbers represent the percentage of cells within the indicated gates.

(B) Proliferation of naïve B-cells following co-culture with migratory CD14+ DDCs, CD1a+ MiDCs and tissue-isolated LCs and dermal CD1a+ DCs. Proliferation was measured by BrdU incorporation after 5 days stimulation. B-cells were cultured in a final volume of 250 μl in the presence of CD40L (100 ng/ml), IL-2 (20 U/ml) and IL-10 (10 ng/ml). Data are presented as mean O.D. values ± SEM of three replicates from one representative experiment of four.

(C) Flow-cytometry analysis of B-cells following co-culture with skin DC subsets (CD14+ DDCs, CD1a+ MiDCs, CD1a+ DDCs and LCs). B-cells were analyzed for surface expression of CD27 and CD38 after 7 days (top panel) and 14 days (bottom panel). Numbers in boxed regions indicate relative percentage of CD27+ CD38+ B-cells. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

(D) Ig secretion following co-culture of naïve B-cells with the indicated numbers of DC subsets for 14 days in the presence of CD40L, IL-2 and IL-10. IgA, IgG and IgM levels in culture supernatants were quantified by ELISA. Data are presented as means ± SEM of duplicate measurements from one representative donor out of four tested.

For comparison, we also tested various DC subsets from the same donors under identical culture conditions (with CD40L, IL-2 and IL-10). Although CD1a+ MiDCs are the most potent stimulators of CD4+ T-cell proliferation (Fig. 1C), we found that CD14+ DDCs were stronger inducers of naïve B-cell proliferation (Fig. 2B). After 7 days, a similar proportion (~50%) of the B-cells in co-cultures with CD1a+ MiDCs or CD14+ DDCs expressed CD27, a marker associated with memory B-cell differentiation (Fig. 2C, top panel), but fewer did so in response to tissue-derived LCs or dermal CD1a+ DCs (Fig. 2C). In contrast, CD14+ DDCs potently triggered CD38 expression by day 7, and the CD27+ CD38+ phenotype was sustained at day 14 (Fig. 2C, bottom panel). Neither CD1a+ MiDCs (Fig. 2C) nor tissue-derived DCs (not shown) could mimic CD14+ DDCs in this regard. Furthermore, stimulating naïve B-cells with CD14+ DDCs induced markedly higher IgM, IgA and IgG levels than when other DC subsets were used (Fig. 2D).

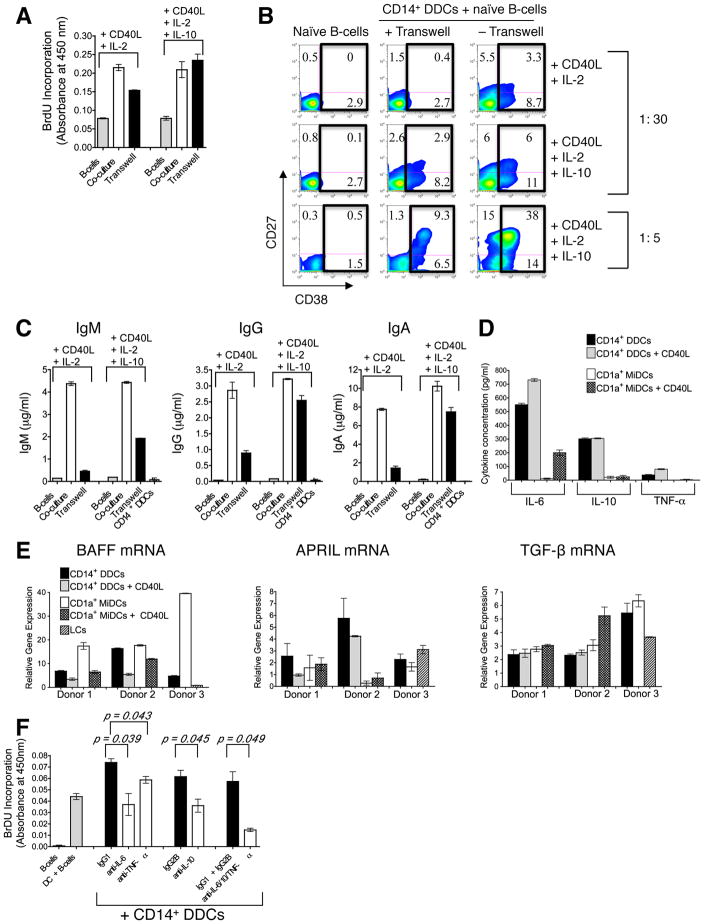

Induction of B-cell proliferation and Ig secretion by unstimulated CD14+ DDCs is dependent on both contact and soluble factors

We next investigated the mechanism(s) by which CD14+ DDCs activate naïve B-cells, by addressing whether cell-cell interactions or soluble molecules were involved. A transwell system was used in which CD14+ DDCs (upper chamber) were separated from naïve B-cells (lower chamber) by a semi-permeable membrane. For comparison, naïve B-cells were cultured alone (in the absence of CD14+ DDCs), or directly co-cultured with CD14+ DDCs in the lower chamber. Every culture contained soluble CD40L and IL-2, either with or without IL-10.

When CD40L and IL-2 were present, CD14+ DDCs could enhance the proliferation of naïve B-cells in the transwell system, but not as well as when the two cell types were directly co-cultured (Fig. 3A). However, when IL-10 was also present, B-cell proliferation was enhanced to similar extents whether the two cell types were in direct contact or separated by the transwell membrane (Fig. 3A). The up-regulation of CD38, a marker associated with plasma cell differentiation, was substantially lower when B-cells and CD14+ DDCs (plus CD40L and IL-2) were separated than in the direct co-culture system (Fig. 3B). When IL-10 was also present, CD38 up-regulation on B-cells was greater in the membrane-separated, transwell cultures (11%) than when the B-cells were cultured with only CD40L, IL-2 and IL-10 (< 3%). Hence soluble factors from the CD14+ DDCs contribute to plasma cell differentiation. However, CD38 up-regulation was even more pronounced (17%) when CD14+ DDCs were in direct contact with B-cells in the presence of CD40L, IL-2 and IL-10; this effect was evident at DC : B-cell ratios of 1:30 (described above) and 1:5 (Fig. 3B lower panel). Thus, cell-cell contact is required for optimal B-cell differentiation.

FIGURE 3. The induction of B-cell proliferation and Ig secretion by CD14+ DDCs is dependent on both cell-cell contact and soluble factors.

(A) Proliferation of naïve B-cells co-cultured with CD14+ DDCs directly, or separated by a membrane in a transwell system, in the presence of CD40L (100 ng/ml), IL-2 (20 U/ml) ± IL-10 (10 ng/ml). Naïve B-cells (6.25 × 105) were cultured in the lower compartment while CD14+ DDCs (2 × 104 (1:30 ratio) or 1.25 × 105 (1:5 ratio)) were either added separately to the upper chamber (labeled on charts as “transwell”) or to the lower compartment (labeled as “co-culture”). Proliferation was measured by BrdU incorporation on day 5. The data are presented as mean O.D. values ± SEM of three replicates within one representative experiment.

(B) Phenotypic analysis of B-cells co-cultured with CD14+ DDCs directly, or separated using a transwell system (same conditions as in A), after 7 days. DC: B-cell ratios of both 1:30 and 1:5 were tested. The numbers in the boxed regions indicate the relative percentage of CD38+ B-cells.

(C) Ig levels in separated or non-separated CD14+ DDC and B-cell co-cultures were quantified by ELISA. Results from one representative donor of four are shown, with the data displayed as means ± SEM of duplicate values.

(D) Endogenous cytokine secretion by CD14+ and CD1a+ MiDC subsets. DCs were isolated and cultured (5 × 104 cells/ml) ± CD40L for 24 h. ELISA was used to quantify IL-6, IL-10 and TNF-α secretion. Results from one representative donor of three are shown, with the data displayed as means ± SEM of duplicates.

(E) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of BAFF, APRIL and TGF-β mRNA expression in freshly isolated cutaneous DC subsets and DCs stimulated for 4 h ± CD40L (donors 1 and 2). Values were normalized against the housekeeping gene GAPDH (arbitrary units). Data are presented as means ± SEM of triplicate measurements.

(F) Contributions of IL-6, IL-10 and TNF-α to CD14+ DDC-induced B-cell proliferation. B-cells were co-cultured with CD14+ DDCs (1 DDC: 2 B-cells, plus CD40L and IL-2) in the presence of NAbs against IL-6, IL-10 or TNF-α. Proliferation was measured by BrdU incorporation on day 5. Isotype-matched irrelevant MAbs served as controls. The data shown are from one of three experiments performed, and are presented as mean O.D. values ± SEM of triplicate measurements.

Higher levels of IgM, IgG and IgA were detected in supernatants from direct co-cultures than those from the transwell system (plus CD40L and IL-2), again implying that cell-cell contact is beneficial for Ig secretion and class switching. However, as Ig levels were consistently higher in the transwell cultures than when B-cells were cultured with only CD40L and IL-2, soluble factor(s) must also be involved (Fig. 3C). When IL-10 was also present, IgG and IgA secretion levels were almost as high in the transwell cultures as when the naïve B-cells were in direct contact with DDCs (Fig. 3C).

CD70 and ICAM-1 (CD54) are surface molecules important for B-cell activation (43, 44). However, CD14+ DDCs did not express CD70, either before or after stimulation with CD40L or TLR ligands (data not shown). ICAM-1 was expressed at high levels on CD14+ DDCs, both endogenously and after stimulation, but comparably to what was seen on CD1a+ MiDCs (data not shown). Since CD1a+ MiDCs are comparatively weak activators of naïve B-cells, other factors seem likely to be involved in the stimulatory effects of CD14+ DDCs.

The above findings prompted us to study the contribution of soluble factors released by CD14+ DDCs and CD1a+ MiDCs. In the absence of stimulation, CD14+ DDCs released substantial amounts of B-cell-activating cytokines, notably IL-6 (500 ± 65 pg/ml from 5 × 104 DCs) but also IL-10 and TNF-α, whereas CD1a+ MiDCs expressed lower levels of these cytokines even after CD40 ligation (Fig. 3D). Neither DC subset expressed IFN-α and IL-12p70 at levels detectable either by ELISA or quantitative RT-PCR, either before or after CD40 ligation or TLR stimulation (data not shown).

Of note is that the expression of BAFF transcripts was not confined to CD14+ DDCs but was also detected in both CD1a+ MiDCs and freshly obtained LCs (Fig. 3E). Surprisingly, endogenous BAFF mRNA levels were higher in CD1a+ MiDCs than CD14+ DDCs but the converse was seen for APRIL mRNA, while TGF-β was expressed to similar extents in both DC subsets (Fig. 3E). Since CD40L was present in the DC-B-cell co-culture system, we studied its effects on mRNA expression in DDC over a 36-h period. Both BAFF and APRIL mRNAs were soon down-regulated when CD14+ DDCs were exposed to CD40L (Fig. 3E; 4 h time-point shown), although the differential expression pattern in the two MiDC subsets remained unaltered. There was no change in TGF-β mRNA expression 4 h after CD40L addition (Fig. 3E), although down-regulation did occur after longer exposures (12 h and 36 h; not shown). Taken together, these data suggest that BAFF, APRIL and TGF-β are not responsible for the B-cell stimulatory capacity of CD14+ DDCs.

We therefore addressed the relative contribution of secreted cytokines (IL-6, IL-10 and TNF-α) in CD14+ DDC-induced B-cell activation by performing blocking experiments with NAbs to IL-6, IL-10 and TNF-α. Blocking these cytokines partially inhibited B-cell proliferation. Thus, relative to DC-B-cell co-cultures containing isotype-matched control MAbs, the NAbs against IL-6, IL-10 and TNF-α reduced B-cell proliferation by ~50% (± 22.6%; p = 0.039), 58% (± 16.0%; p = 0.045) and ~21% (± 6.9%; p = 0.043) respectively (Figure 3F). Blocking all three cytokines together reduced B-cell proliferation by 74% (± 4.4%; p = 0.049). The inference is that multiple factors, including but perhaps not limited to IL-6, IL-10 and TNF-α, are involved in the activation of naïve B-cells by CD14+ DDCs.

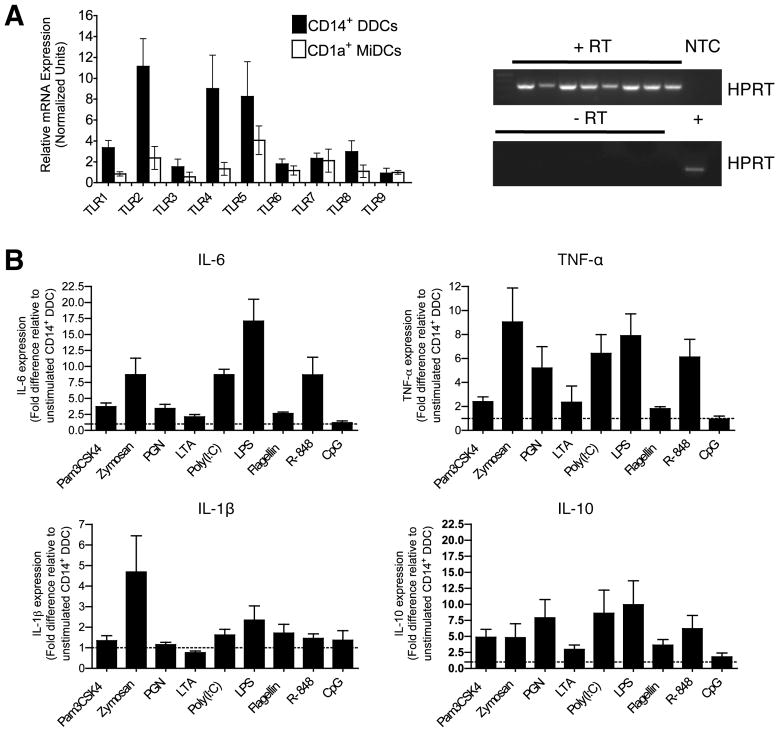

TLR expression by CD14+ DDCs and their response to individual TLR ligands

The potent ability of CD14+ DDCs to stimulate naïve B-cells (in the presence of CD40L and cytokines) implies that they are suitable targets for vaccine strategies when a strong humoral immune response is required. Accordingly, we determined whether we could further enhance their inherent functionality via stimulation with TLR ligands. First, we quantified the endogenous mRNA expression levels of TLRs 1-9 in freshly isolated, highly purified (by FACS) CD14+ DDCs and CD1a+ MiDCs from four different donors. We confirmed the presence of amplifiable material and absence of genomic DNA by housekeeping gene (HPRT) RT-PCR prior to qPCR analysis (Fig. 4A gel images). In general, CD14+ DDCs expressed higher levels of transcripts for cell-surface TLRs that recognize bacteria (in particular, TLR2, TLR4 and TLR5), whereas the two DC subsets expressed similar levels of the endosomally located TLRs, which recognize viral RNA (TLRs 3, 7 and 8) and prokaryotic DNA (TLR9) (Fig. 4A).

FIGURE 4. CD14+ DDCs express a broad TLR profile but have differential cytokine responses to TLR ligands.

(A) TLR mRNA expression in highly purified skin DC subsets was assessed by quantitative Taqman® RT-PCR. RNA was extracted from highly purified CD14+ DDCs and CD1a+ MiDCs from four different donors and used for cDNA preparation. cDNA samples were first shown to contain amplifiable material (+RT), and to be free of genomic DNA (-RT), by conventional HPRT RT-PCR (gel images). NTC, no template control; +RT, plus reverse transcriptase; -RT, without reverse transcriptase; +, positive cDNA control. For quantitative RT-PCR, mRNA expression values were normalized against the GAPDH gene. Data are presented as means ± SEM of triplicate measurements.

(B) Cytokine secretion by CD14+ DDCs after stimulation for 48 h with the indicated TLR ligands. Data are presented as fold differences relative to unstimulated CD14+ DDCs, and are derived from four independent experiments (means ± SEM).

Since CD14+ DDCs endogenously expressed TLRs 1-9 (albeit to different extents), we stimulated these cells with a panel of TLR 1-9 ligands for 48 h and measured cytokine levels in the supernatants (Fig. 4B). All the TLR ligands except CpG-2395 (type C CpG) triggered release of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α, but the most consistently potent were zymosan, LPS, Poly(I:C) and R-848. Secretion of IL-1β was more modest, with zymosan, Poly(I:C) and LPS having the greatest effect. As seen with IL-6 and TNF-α, all the TLR ligands except CpG-2395 stimulated IL-10 expression, Poly(I:C) and LPS doing so most strongly. Consistent with reports that cutaneous DCs do not express IL-12p70 (even after CD40 ligation), this cytokine was not detected as a response to any of the TLR ligands (not shown; (28)). With the exception of Poly(I:C), TLR ligands up-regulated maturation markers to only a limited extent (data not shown).

Some TLR ligand pairs enhance CD14+ DDC maturation and cytokine secretion

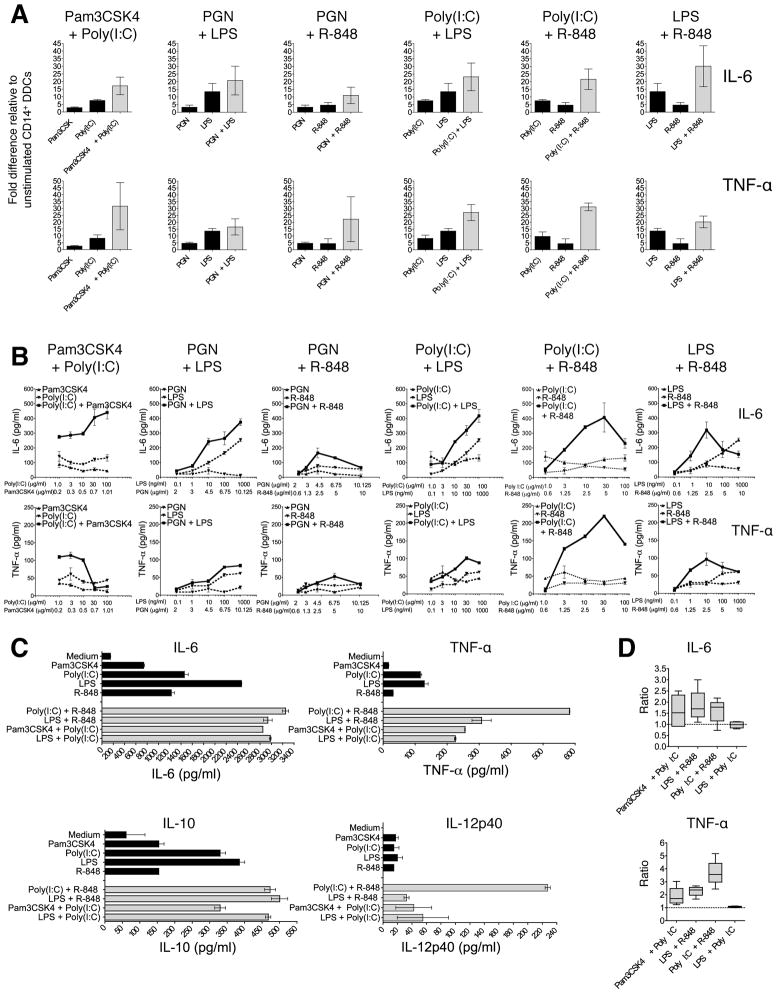

The dual TLR ligation of MoDCs synergistically enhances IL-12p70 release and Th1-cell differentiation (37). We therefore sought to identify which, if any, TLR ligand combinations boosted cytokine expression by CD14+ DDCs. To do so, we exposed cells from three different donors to the above ligands for TLRs 1-9, and to all (36) possible dual-ligand combinations. In all three donors, six TLR ligand combinations increased the secretion of IL-6 and TNF-α to at least an additive extent (Fig. 5A): Pam3CSK4 plus Poly(I:C); PGN plus either LPS or R-848; Poly(I:C) plus either LPS or R-848; and LPS plus R-848. These six combinations were therefore tested over a wide concentration range, including ones normally sub-optimal for cytokine stimulation. Four combinations were effective over a range of concentrations: Pam3CSK4 plus Poly(I:C); Poly(I:C) plus either LPS or R-848; LPS plus R-848 (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5. Selected combinations of TLR ligands potently induce cytokine secretion by CD14+ DDCs.

(A) Cytokine expression by CD14+ DDCs following exposure to individual TLR ligands or combinations for 24 h. Data are presented as means ± SEM from three independent experiments.

(B) Cytokine production after stimulation of CD14+ DDCs for 24 h with a range of concentrations (horizontal axes) of Pam3CSK4, Poly(I:C), PGN, LPS or R-848, or with combinations of these TLR ligands. Data are presented as means ± SEM of duplicates from one donor. Solid lines represent treatment with combined TLR ligands. Dashed lines represent treatment with a single TLR ligand.

(C) Cytokine expression from CD14+ DDCs treated for 24 h with individual TLR ligands (Pam3CSK4, Poly(I:C), LPS and R-848) and four combinations (Pam3CSK4 plus Poly(I:C); LPS plus Poly(I:C); Poly(I:C) plus R-848; LPS plus R-848). Data are presented as means ± S.D. of duplicates from one representative experiment of five.

(D) Validation of potential synergistic effects of four TLR ligand combinations on cytokine expression. Data are presented as means ± SEM of four independent experiments. The ratio of the highest cytokine response elicited by combined stimuli over the sum of the responses for the two individual agents at their constituent concentrations was calculated. A ratio >1 is indicative of synergy, =1 of additivity, and < 1 of antagonism.

In most donors, the latter four TLR ligand combinations consistently increased both IL-6 and TNF-α secretion relative to treatment with the individual agents, and they also had a modest effect on IL-10 expression (Fig. 5C). Neither BAFF nor APRIL was detected in CD14+ DDC-derived supernatants, whereas TGF-β release was increased upon stimulation with R-848 plus either Poly(I:C) or LPS (data not shown). Furthermore, none of the TLR ligands/combinations increased BAFF or APRIL mRNA expression over 4–24 h, except for Poly(I:C) which triggered a marginal (<2-fold) elevation in BAFF transcripts (data not shown). Again, IL-12p70 was not detected in supernatants obtained from TLR-stimulated CD14+ DDCs, although it is expressed by MoDCs under the same experimental conditions (Supplemental Fig. 3A). However, levels of the IL-12p40 protein subunit (which is common to both IL-12p70 and IL-23) were further increased following stimulation of CD14+ DDCs with TLR ligand combinations, particularly when Poly(I:C) was combined with R-848 (Fig. 5C; Supplemental Fig. 3B). Of note is that CD14+ DDCs from none of the donors expressed IFN-α (assessed by both quantitative RT-PCR and ELISA) in response to any TLR ligand combination (not shown). In this regard, CD14+ DDCs differ from plasmacytoid DCs, which secrete high levels of this B-cell stimulatory cytokine upon TLR stimulation. The same four TLR ligand combinations also modestly enhanced the phenotypic maturation of CD14+ DDCs, in that they were superior to the individual agents at triggering the up-regulation of CD86, HLA-DR and CD40 (Supplemental Fig. 3C). This observation is consistent with a previous report (37).

We next investigated whether the enhancing effects of the above four combinations were indicative of synergy or additivity. To do so, CD14+ DDCs from four different donors were stimulated with a range of TLR ligand(s) concentrations (as in Fig. 5B). The LPS plus Poly(I:C) combination had an additive effect on cytokine production, whereas the other three combinations were synergistic (ratio > 1) stimulators of both IL-6 and TNF-α expression, but not IL-10 (data not shown). The rank order was Poly(I:C) plus R-848 > LPS plus R-848 > Pam3CSK4 plus Poly(I:C) (Fig. 5D).

Based on the consistency and potency of their stimulatory effects on CD14+ DDCs and the availability of clinically relevant modifications of Poly(I:C) (i.e., Hiltonol (Poly(I:CLC)) and LPS (i.e., MPL and glucopyranosyl lipid A (GLA)), we selected the Poly(I:C) plus R-848 and LPS plus R-848 combinations for further studies. Both pairs enhanced IL-6 and IL-10 expression from 18–48 h after addition but boosted TNF-α expression more rapidly and transiently; the latter response was visible by 4 h, peaked between 6 and 18 h and was still apparent at 48 h (Supplemental Fig. 3D). Notably, these selected TLR ligand combinations also enhanced IL-6 and TNF-α expression in CD14+ DDCs isolated directly from dermal tissue (Supplementary Fig. 3E).

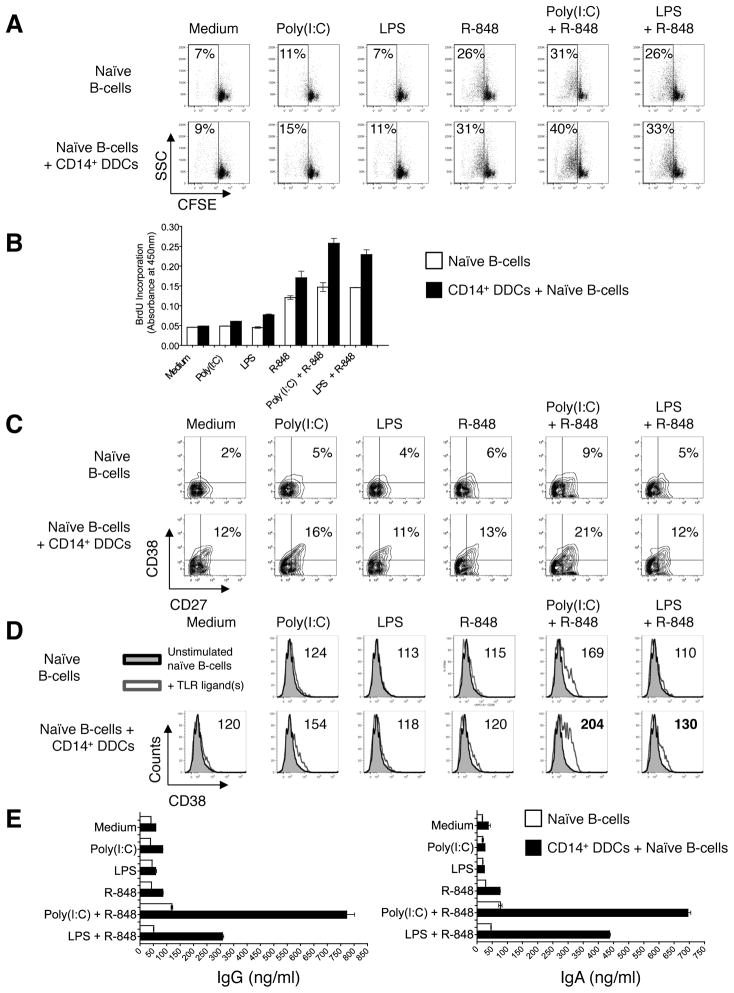

Enhanced B-cell stimulatory capacity of dual TLR ligand-stimulated CD14+ DDCs

We next studied how the TLR ligand-stimulated CD14+ DDCs affected the differentiation of naïve B-cells. In initial experiments, CD14+ DDCs were first exposed to TLR ligands for 12 h and then washed before initiating the co-culture, so as to avoid direct activation of B-cells by the added TLR ligands. Under these conditions, CD14+ DDCs stimulated with the TLR ligand pairs were only a little better at stimulating B-cell proliferation or Ig secretion than when single ligands were used (data not shown and Supplemental Fig. 4A). The most likely explanation for the lack of synergy in this experimental setup is a diminished production of B-cell stimulatory cytokines by the CD14+ DDCs once they are washed free of TLR ligands after short-term (4–12 h) stimulation, a procedure that aborts their stimulation (Supplemental Fig. 4B).

To further gauge the role of accumulated cytokines, we assessed whether conditioned media from CD14+ DDCs that had been stimulated for 24 h with TLR ligand(s) could activate CFSE-labeled naïve B-cells. Anti-Ig was included in the cultures, to induce BCR ligation. Under these conditions, supernatants from Poly(I:C) plus R-848-stimulated CD14+ DDCs were the strongest activators of B-cell proliferation, while the use of LPS plus R-848 as stimulants had a more modest effect (Supplemental Fig. 4C). For comparison, we tested authentic TLR ligands at the same concentrations, to determine what effects they had in the context of anti-Ig stimulation. This control was necessary as human naïve B-cells express low levels of mRNA to several TLRs, including TLR7, and can be directly activated by TLR ligands, including R-848 (45). We found that R-848, but not LPS, consistently induced B-cell proliferation, while Poly(I:C) had a modest effect that was enhanced by R-848 addition. Furthermore, supernatants from TLR-treated CD14+ DDCs stimulated B-cell proliferation to a greater extent than control supernatants.

Taken together, the above studies showed that soluble factor(s) from CD14+ DDCs are required for optimal stimulation of naïve B-cells (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 4C), and that cytokine expression is compromised if CD14+ DDCs are exposed to TLR ligands for only a short period (Supplementary Fig. 4B). Hence, all the following experiments were conducted by co-culturing CD14+ DDCs and naïve B-cells in the continuous presence of TLR ligands and either anti-Ig (in the CFSE proliferation assays only), or with IL-2 plus CD40L (to mimic T-cell help). The latter arrangement mimics the ménage-à-trois between DCs, B-cells and T-cells (46). For comparison, naïve B-cells were cultured without CD14+ DDCs, but in the presence of the same soluble agents.

We tested the capacity of our selected TLR ligand combinations to induce naïve B-cell proliferation in the presence of CD14+ DDCs. CFSE-labeled naïve B-cells were cultured alone, or co-cultured with CD14+ DDCs plus the indicated TLR ligands in the presence of anti-Igs, for 5 days before cell proliferation was assessed by flow cytometry. In the absence of CD14+ DDCs, R-848 again induced proliferation, a response that was further augmented by adding Poly(I:C) (Fig. 6A). Strikingly, adding CD14+ DDCs together with Poly(I:C) plus R-848 substantially increased the proliferation of naïve B-cells, while the use of LPS plus R-848 had a more modest effect. Similar trends were also observed when CD40L and IL-2 were used instead of anti-Ig (data not shown). When B-cell proliferation was measured using the BrdU assay (plus CD40L and IL-2) instead of by CFSE dilution, similar results were obtained; again, adding CD14+ DDCs together with the Poly(I:C) plus R-848 combination had a particularly pronounced effect (Fig. 6B).

FIGURE 6. Dual TLR-ligand stimulated CD14+ DDCs have an increased capacity to induce naïve B-cells to proliferate and differentiate into Ig-secreting B-cells.

(A) Proliferation of B-cells after stimulation with TLR ligands in the presence or absence of CD14+ DDCs, measured by CFSE dilution. Naïve B-cells were labeled with CFSE and cultured in the presence of anti-Ig and the indicated TLR ligands, with or without CD14+ DDCs (DC: B-cell ratio of 1:5). Proliferation was assessed by flow cytometry after 5 days. B-cells were gated as CD19+, and DCs were excluded from the analysis. The percentage of CFSE-low (divided B-cells; boxed area) is indicated.

(B) Proliferation of B-cells after stimulation with TLR ligands in the presence or absence of CD14+ DDCs, measured by BrdU incorporation. Naïve B-cells were isolated and cultured for 5 days with selected TLR ligands in the presence of CD40L and IL-2, and with or without CD14+ DDCs (DC: B-cell ratio of 1:5). Data are presented as mean O.D. values ± SEM of triplicate wells from one representative experiment of three.

(C) Phenotypic analysis of B-cells after 7 days of stimulation with selected TLR ligand combinations in the presence or absence of CD14+ DDCs (plus CD40L and IL-2). Numbers denote the percentage of CD38+ CD27+ B-cells.

(D) Expression levels of surface CD38 on B-cells after stimulation for 7 days with selected TLR ligand combinations (open gray histograms) in the presence or absence of CD14+ DDCs (plus CD40L and IL-2), relative to B-cells cultured without TLR ligands (filled gray histograms). Numbers denote the relative mean (geometric) fluorescence intensity of CD38.

(E) Ig secretion in B-cell cultures following stimulation for 14 days with the indicated TLR ligands and CD40L plus IL-2, in the presence or absence of CD14+ DDCs. Ig secretion was quantified by ELISA. Data are presented as means ± SEM of duplicates from one representative experiment of three.

Next, we addressed whether CD38 and CD27 were up-regulated on B-cells in response to TLR ligand-activated CD14+ DDCs. When naïve B-cells were co-cultured with control DDCs, 12% acquired the CD38+ CD27+ phenotype, similar to what was seen on naïve B-cells after exposure to Poly(I:C) plus R-848 (9%) in the absence of DDCs. Co-culturing B-cells with DDCs and either Poly(I:C) or R-848 lead to only a marginal, or no, increase in the proportion of CD38+ CD27+ B-cells, to 16% and 13% respectively (Fig. 6C). A more pronounced increase, to 21%, was observed in co-cultures containing the combination of Poly(I:C) plus R-848. In contrast, combining LPS with R-848 had little or no effect on the proportion of CD38+ CD27+ B-cells, compared to either TLR ligand alone (Fig. 6C). However, the CD38 expression level (mean fluorescence intensity) was increased when either TLR ligand combination was added in the presence of CD14+ DDCs, although more pronounced with Poly(I:C) plus R-848 than with LPS plus R-848 (Fig. 6D).

Immunoglobulin secretion was strongly enhanced in the presence of CD14+ DDCs and Poly(I:C) plus R-848, less so when the LPS plus R-848 combination was used instead. Moreover, IgG and IgA production was ~8-fold greater when naïve B-cells were treated with CD14+ DDCs and Poly(I:C) plus R-848 compared to when only the TLR ligands were used as stimulants (Fig. 6E). Taken together, the above results indicate that when the Poly(I:C) plus R-848 combination, and to a lesser extent LPS plus R-848, is used in association with CD14+ DDCs, naïve B-cells are efficiently activated. The stimulated B-cells both proliferate and differentiate to CD38-expressing B-cells that secrete IgA and IgG.

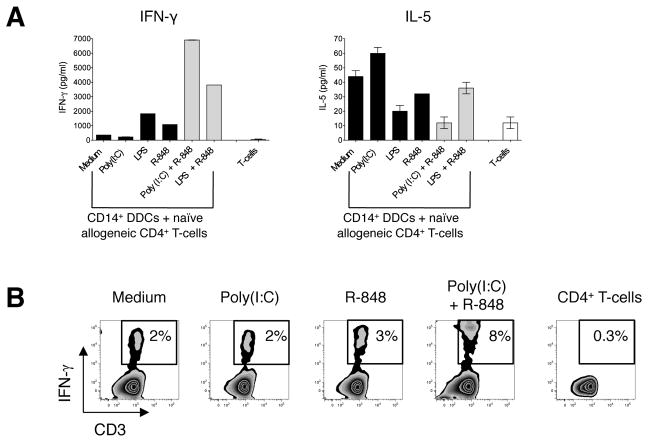

CD14+ DDCs have enhanced Th1-polarizing capacity when stimulated with selected TLR ligand combinations

We next evaluated how TLR ligation affected the Th-priming capabilities of CD14+ DDCs. We therefore stimulated CD14+ DDCs with single TLR ligands or the combinations highlighted above, and tested their capacity to prime naïve allogeneic CD4+ T-cells from several donors. Of note is that when CD14+ DDCs were first stimulated with either LPS plus R-848 or Poly(I:C) plus R-848, they induced Th1-cell polarization to a much greater extent than when single TLR ligands were used, irrespective of whether the endpoint was IFN-γ production (Fig. 7A) or the percentage of IFN-γ positive cells (Fig. 7B). In contrast, TLR ligand-stimulated CD14+ DDCs never triggered naïve CD4+ T-cells to differentiate into Th17 cells (data not shown). The Th2-associated cytokine IL-5 was produced at lower levels in co-cultures involving CD14+ DDCs previously exposed to selected TLR ligand combinations than when unstimulated DDCs, or DDCs treated with only a single ligand, were used (Fig. 7A). This data pattern is consistent with the increased production of IFN-γ, a cytokine that inhibits Th2-cell differentiation, under the same conditions (Fig. 7A).

FIGURE 7. Dual TLR ligand-stimulated CD14+ DDCs have enhanced Th1-polarizing capacity.

(A) Cytokine secretion by responder allogeneic CD4+ T-cells following culture for 6 days with TLR ligand-stimulated CD14+ DDCs. CD14+ DDCs were stimulated for 12 h with Poly(I:C), LPS, R-848, Poly(I:C) plus R-848 or LPS plus R-848, washed and co-cultured with allogeneic naïve (CD27+ CD45RO−) CD4+ T-cells from a healthy donor. Supernatants were collected on day 6 of the co-culture and screened for IFN-γ and IL-5 by ELISA. Data are representative of three independent experiments and are presented as means ± SEM of duplicate samples.

(B) Intracellular cytokine expression by responder allogeneic CD4+ T-cells after 6 days of co-culture. T-cells were tested for their capacity to secrete IFN-γ after re-stimulation for 6 h with PMA and ionomycin in the presence of brefeldin. The numbers in the boxed regions indicate the percentage of CD4+ T-cells expressing intracellular IFN-γ. Data are from one of three experiments performed.

Discussion

Targeting the skin is a rational approach to vaccination as this organ contains abundant and diverse DC subsets. However, to make better vaccines, we need to further understand the diversity and biology of these subsets so as to avoid eliciting an unfavorable (e.g., Th17-polarized) or irrelevant immune response (e.g., CTL induction against a parasitic worm). The functional specializations of skin DCs are now becoming better defined (25, 26, 28), although some uncertainties remain. It has been argued that selectively targeting distinct DC subsets would be advisable when a specific immune response is required. For example, a strong CTL response would be best achieved via epidermal LCs, whereas CD14+ DDCs would be advantageous for strong humoral responses (26). Our goals here were: first, to assess whether bona fide CD14+ DDCs can induce humoral immune responses ex vivo; second, to identify which TLR ligands can further augment the B-cell and CD4+ T-cell stimulatory capacity of these cells, and hence might serve as adjuvants for intradermal or subcutaneous vaccines.

One focus of our studies was to investigate the effects that skin-derived CD14+ DDCs have on the differentiation of naïve B-cells. When CD40L was added (to mimic activated CD4+ T-cells), CD14+ DDCs were highly potent at inducing naïve B-cells to proliferate and differentiate into CD38+ CD27+ B-cells that secrete high levels of IgG and IgA. Our findings are consistent with observations made using CD34+ progenitor-derived CD14+ DDCs (32). Moreover, we found that CD14+ DDCs were the most potent skin DC subset in this regard, markedly superior to CD1a+ MiDCs (comprising both migratory LCs and dermal CD1a+ DCs) and tissue-derived DCs.

Of note is that the B-cell stimulatory function of CD14+ DDCs appears to involve both secretory factors and cell-cell contact. Transwell studies showed that CD14+ DDCs were capable of inducing relatively high levels of B-cell proliferation and enhancing Ig class-switching when CD40L and IL-2 were present, although not as potently as when DDCs were in direct contact with naïve B-cells. When IL-10 was also included in the system, B-cell proliferation was similar irrespective of whether the two cell types were separated or in direct contact. Furthermore, IgG and IgA secretion levels were only slightly lower when B-cells and DDCs were separated than when they were in direct contact.

When considering the role of cell-cell contact in how CD14+ DDCs activate B-cells, we noted that CD70 was recently identified as an important factor on plasmacytoid DCs for regulating B-cell growth and differentiation (43). However, we found no evidence for CD70 expression on CD14+ DDCs, even after CD40 ligation (unpublished data). pDCs can also activate B-cells through the ICAM-1-LFA-1 pathway (44). Although we did find high levels of ICAM-1 (CD54) on freshly isolated CD14+ DDCs, there were no consistent differences between CD14+ DDCs and CD1a+ MiDCs in this regard, even after stimulation with CD40L. As CD1a+ MiDCs are comparatively poor stimulators of naïve B-cells, ICAM-1 expression is not sufficient. Hence, it is likely that other factors are involved in B-cell activation by CD14+ DDCs.

The above studies implicate the involvement of soluble factors in B-cell activation. Accordingly, we measured the expression of cytokines known to be promoters of B-cell growth and differentiation, including IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, IFN-α, TGF-β, BAFF and APRIL. In the absence of any additional stimulation, CD14+ DDCs secreted higher levels of IL-6, IL-10 and TNF-α than the other DC subsets we studied. Of note is that CD14+ DDCs expressed lower levels of BAFF mRNA than CD1a+ MiDCs, even after CD40 ligation, suggesting that this cytokine may not be responsible for their potent B-cell stimulatory capacity. Conversely, CD14+ DDCs endogenously expressed comparatively high levels of APRIL mRNA. However, this mRNA was down-regulated when the cells were stimulated with CD40L and we were unable to detect secreted APRIL by ELISA (either before or after DC stimulation). It is, therefore, unlikely that APRIL plays a role in how CD14+ DDCs activate naïve B-cells. In blocking experiments, NAbs against IL-6, IL-10 and TNF-α reduced the extent of B-cell activation by CD14+ DDC, implicating these cytokines in the process. Overall, the inherently different functional specializations of CD14+ and CD1a+ MiDCs are likely to be attributable to their endogenous cytokine expression profiles. Thus, CD14+ DDCs produce several B-cell stimulatory cytokines at high levels whereas CD1a+ MiDCs express greater amounts of co-stimulatory molecules and MHC class II molecules that render them efficient stimulators of naïve CD4+ T-cells.

We next assessed whether we could further enhance the already potent B-cell stimulatory capacity of CD14+ DDCs by treating them with potential adjuvants, specifically TLR ligands. We identified several TLR ligand combinations that were highly effective in this regard, and in a donor-independent manner: Pam3CSK4 plus Poly(I:C); LPS plus Poly(I:C); Poly(I:C) plus R-848; LPS plus R-848. Compared to the individual components, three combinations (Pam3CSK4 plus Poly(I:C); Poly(I:C) plus R-848 and LPS plus R-848) synergistically enhanced cytokine secretion, the latter two combinations being the most potent. The enhancing effect of these TLR ligand pairs is consistent with findings that the TRIF-dependent pathway (activated by Poly(I:C) or LPS) amplifies the MyD88-dependent pathway (activated by Pam3CSK4, LPS or R-848) through a JNK-dependent mechanism (36, 37). The Poly(I:C) plus R-848 and LPS plus R-848 combinations are known to be strongly synergistic at inducing IL-12p70 expression in MoDCs and the concomitant triggering of Th1-cell differentiation (37). We can now extend these observations to skin-derived CD14+ DDCs and the activation of naïve B-cells.

As noted, CD14+ DDCs stimulated with R-848 plus either Poly(I:C) or LPS can strongly stimulate naïve B-cells to proliferate and differentiate into CD38+ B-cells that secrete high levels of Ig. These B-cell responses to activated CD14+ DDCs are superior to when naïve B-cells were stimulated only with the same TLR ligands. Soluble factors are involved, since cell-free supernatants from TLR-stimulated CD14+ DDCs strongly activated the B-cells. This finding is consistent with the observation that dual TLR ligation of CD14+ DDCs triggers the up-regulation of several B-cell stimulatory cytokines, notably IL-6, IL-10 and TNF-α, but not BAFF mRNA. Although APRIL mRNA is endogenously expressed at a high level, it was not up-regulated upon TLR ligation.

The Poly(I:C) plus R-848 combination was also superior to the individual ligands at directly activating naïve B-cells; i.e., in the absence of CD14+ DDCs. While human naïve B-cells endogenously express low levels of mRNA for TLRs 7 and 9 (47), they have not been reported to express TLR3, the target for Poly(I:C). However, it is possible that a second family of pattern recognition receptors, namely the intracellular helicases retinoic acid-inducible gene-1 (RIG-1) and melanoma differentiation-associated antigen-5, both of which recognize dsRNA, may be involved (1).

We confirmed that combining either Poly(I:C) or LPS with R-848 enhanced the Th1-polarization capability of CD14+ DDCs (and also MoDCs; our unpublished observations) (37). Although high levels of IL-12p70 were induced in MoDCs, this was not the case with CD14+ DDCs. Hence, the IL-12p70-independent Th1 polarization pathway may be involved (28). As the induction of a strong Th1 response would be highly desirable when potent cellular immunity is required, it is notable that CD14+ DDCs were as capable as CD1a+ MiDCs at inducing Th1 polarization when activated with Poly(I:C) plus R-848 (unpublished data).

Traditionally, vaccines are administered subcutaneously or intramuscularly, but there is evidence that targeting the skin directly could be advantageous (48–50). Thus, the intradermal route was superior to subcutaneous or transcutaneous delivery for inducing polyvalent immune responses to HIV-1 Gag (51). Another attractive strategy is to combine intradermal delivery of vaccine adjuvants with specific targeting of cutaneous DC subsets, for example by conjugating the Ag (or adjuvant) to a MAb specific for a DC-expressed surface molecule. Indeed, a fusion protein between HIV-1 Gag and an anti-DEC-205 MAb is now in clinical trials (52, 53). One factor relating to the use of TLR ligands as adjuvants is their potential effects on other skin-resident cells. Perhaps not surprisingly, there is overlap of TLR expression (e.g., TLR3) within resident skin DC subsets such as LCs (54, 55). We have not yet studied how our selected TLR ligand combinations affect other skin DC subsets.

While the toxicity of LPS precludes its clinical use, safer derivatives such as GLA or MPL are now approved for humans (1, 4). Applied as a gel, R-848 markedly reduces the reactivation of human anogenital HSV-2, implying it is safe and effective in vivo (56). The vulnerability of Poly(I:C) to serum RNases limits its clinical application, but a more stable version, Hiltonol, is now in late-stage clinical trials (1). We are now testing these various clinically relevant TLR activators for their effects on CD14+ DDCs in vitro.

Activating multiple DC subsets by engagement of TLRs, e.g., by combining Hiltonol with R-848, or MPL with R-848, might be particularly advantageous for any vaccine by inducing polyvalent immune responses. Thus, the engagement of several TLRs (TLRs 2, 7, 8 and 9) by different DC subsets underlies the highly successful yellow-fever (YF-17D) vaccine (57). Strong NAb responses to influenza hemagglutinin (HA) were found when synthetic nanoparticles containing HA and the adjuvants MPL (TLR4) plus R-848 (TLR7/8) were administered subcutaneously (35). Similar studies with other pathogen Ags such as HIV-1 and Ebola glycoproteins seem justified.

In summary, we have shown that targeting CD14+ DDCs is a desirable strategy when the induction of a strong humoral immune response is required. Thus, two potential vaccine adjuvant combinations (Poly(I:C) plus R-848 and LPS plus R-848) further enhanced the endogenous capacity of CD14+ DDCs to differentiate naïve B-cells into CD38+ CD27+ B-cells capable of secreting high levels of immunoglobulins. Furthermore, the dual TLR-stimulated CD14+ DDCs also have strongly augmented Th1-polarizing capacity. Targeting these cells may be useful when the goal is to induce both a strong humoral immune response and Th1 polarization, for example when vaccinating against intracellular pathogens such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Ebola virus and HIV-1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by NIH grants AI36082 and AI45463 to JPM. RWS is a recipient of a Vidi grant from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) and a Starting Investigator Grant from the European Research Council (ERC-StG-2011-280829-SHEV).

We sincerely thank the skin donors and their next of kin for their kind donation of tissue. We are also grateful to all members of the New York Firefighters’ Skin Bank team at the New York Presbyterian Hospital, particularly Professor Roger Yurt, Nancy Gallo, Heather Locklear, Paul Rizza, Avery Henix, Truman Cazales and Randy Chisholm. We sincerely appreciate the provision of FACS sorting facilities and helpful discussions with both Dr. Sergei Rudchenko and Mihaela Stevanovic (Hospital for Special Surgery, New York). We also thank Iain Finlayson for assisting with Figures.

Abbreviations

- DCs

dendritic cells

- MiDCs

migratory DCs

- CD14+ DDCs

CD14+ dermal-derived DCs

- LCs

Langerhans’ cells

- MoDCs

monocyte-derived DCs

- Poly(I,C)

Polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid

- R-848

resiquimod

References

- 1.Coffman RL, Sher A, Seder RA. Vaccine adjuvants: putting innate immunity to work. Immunity. 2010;33:492–503. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marrack P, McKee AS, Munks MW. Towards an understanding of the adjuvant action of aluminium. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2009;9:287–293. doi: 10.1038/nri2510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pashine A, Valiante NM, Ulmer JB. Targeting the innate immune response with improved vaccine adjuvants. Nature Medicine. 2005;11:S63–68. doi: 10.1038/nm1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duthie MS, Windish HP, Fox CB, Reed SG. Use of defined TLR ligands as adjuvants within human vaccines. Immunological Reviews. 2011;239:178–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00978.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Regulation of adaptive immunity by the innate immune system. Science. 2010;327:291–295. doi: 10.1126/science.1183021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptor control of the adaptive immune responses. Nature Immunology. 2004;5:987–995. doi: 10.1038/ni1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akira S, Takeda K. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2004;4:499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–252. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fonteneau JF, Gilliet M, Larsson M, Dasilva I, Munz C, Liu YJ, Bhardwaj N. Activation of influenza virus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells: a new role for plasmacytoid dendritic cells in adaptive immunity. Blood. 2003;101:3520–3526. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diebold SS, Montoya M, Unger H, Alexopoulou L, Roy P, Haswell LE, Al-Shamkhani A, Flavell R, Borrow P, Reis e Sousa C. Viral infection switches non-plasmacytoid dendritic cells into high interferon producers. Nature. 2003;424:324–328. doi: 10.1038/nature01783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Jong EC, Vieira PL, Kalinski P, Schuitemaker JH, Tanaka Y, Wierenga EA, Yazdanbakhsh M, Kapsenberg ML. Microbial compounds selectively induce Th1 cell-promoting or Th2 cell-promoting dendritic cells in vitro with diverse th cell-polarizing signals. J Immunol. 2002;168:1704–1709. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.4.1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manickasingham SP, Edwards AD, Schulz O, Reis e Sousa C. The ability of murine dendritic cell subsets to direct T helper cell differentiation is dependent on microbial signals. European Journal of Immunology. 2003;33:101–107. doi: 10.1002/immu.200390001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pulendran B. Modulating vaccine responses with dendritic cells and Toll-like receptors. Immunological Reviews. 2004;199:227–250. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edwards AD, Manickasingham SP, Sporri R, Diebold SS, Schulz O, Sher A, Kaisho T, Akira S, Reis e Sousa C. Microbial recognition via Toll-like receptor-dependent and -independent pathways determines the cytokine response of murine dendritic cell subsets to CD40 triggering. J Immunol. 2002;169:3652–3660. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmitt N, Morita R, Bourdery L, Bentebibel SE, Zurawski SM, Banchereau J, Ueno H. Human dendritic cells induce the differentiation of interleukin-21-producing T follicular helper-like cells through interleukin-12. Immunity. 2009;31:158–169. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crotty S. Follicular helper CD4 T cells (TFH) Annual Review of Immunology. 2011;29:621–663. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cerutti A, Qiao X, He B. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells and the regulation of immunoglobulin heavy chain class switching. Immunology and Cell Biology. 2005;83:554–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2005.01389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Saint-Vis B, Fugier-Vivier I, Massacrier C, Gaillard C, Vanbervliet B, Ait-Yahia S, Banchereau J, Liu YJ, Lebecque S, Caux C. The cytokine profile expressed by human dendritic cells is dependent on cell subtype and mode of activation. J Immunol. 1998;160:1666–1676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Litinskiy MB, Nardelli B, Hilbert DM, He B, Schaffer A, Casali P, Cerutti A. DCs induce CD40-independent immunoglobulin class switching through BLyS and APRIL. Nature Immunology. 2002;3:822–829. doi: 10.1038/ni829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]