Abstract

We asked whether aged adults are more susceptible to exercise-induced pulmonary edema relative to younger individuals. Lung diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO), alveolar-capillary membrane conductance (Dm) and pulmonary-capillary blood volume (Vc) were measured before and after exhaustive discontinuous incremental exercise in 10 young (YNG; 27±3 yr) and 10 old (OLD; 69±5 yr) males. In YNG subjects, Dm increased (11±7%, P=0.031), Vc decreased (−10±9%, P=0.01) and DLCO was unchanged (30.5±4.1 vs. 29.7±2.9 ml/min/mmHg, P=0.44) pre- to post-exercise. In OLD subjects, DLCO and Dm increased (11±14%, P=0.042; 16±14%, P=0.025) but Vc was unchanged (58±23 vs. 56±23 ml, P=0.570) pre- to post-exercise. Group-mean Dm/Vc was greater after vs. before exercise in the YNG and OLD subjects. However, Dm/Vc was lower post-exercise in 2 of the 10 YNG (−7±4%) and 2 of the 10 OLD subjects (−10±5%). These data suggest that exercise decreases interstitial lung fluid in most YNG and OLD subjects, with a small number exhibiting evidence for exercise-induced pulmonary edema.

Keywords: Lung fluid, alveolar-capillary membrane conductance, aged adults

1. Introduction

The volume of extravascular pulmonary fluid is a function of pulmonary capillary fluid extrusion relative to the rate of fluid removal from the pulmonary interstitium (Bates et al., 2011). While fluid flux across the pulmonary vasculature is determined by the balance between the hydrostatic pressure in the pulmonary capillaries and the hydrostatic pressure in the interstitial space as well as the permeability of the pulmonary capillaries to fluid, fluid clearance from the interstitial space is largely dependent on the activity of the pulmonary lymphatics. During heavy exercise, the increase in venous return along with an increase in pulmonary blood flow heterogeneity, which causes regional overperfusion in the pulmonary vasculature, results in a marked increase in pulmonary capillary pressure (Bates et al., 2011; Burnham et al., 2009; Eldridge et al., 2006a; Kovacs et al., 2009; Reeves et al., 2005; Younes et al., 1987). Theoretically, such an increase in transcapillary fluid pressure should disturb lung fluid balance by promoting fluid movement from the pulmonary vasculature to the interstitial space via an increase in capillary leakage and, in extreme cases, degradation of the pulmonary microcirculation. However, whether interstitial pulmonary edema develops in response to exercise at sea-level in healthy humans remains controversial with some (Eldridge et al., 2006a; McKenzie et al., 2005; Zavorsky et al., 2006a) (Caillaud et al., 1995; Eldridge et al., 2006b, a; McKenzie et al., 2005; Zavorsky et al., 2006b) but not all (Brasileiro et al., 1997; Gallagher et al., 1988; Hodges et al., 2007; Manier et al., 1999b; Marshall et al., 1971) previous studies reporting an increase in extravascular lung fluid following exercise. While the effects of hypoxia, sex and exercise intensity and duration have been explored, the influence of healthy aging on the incidence exercise-induced pulmonary edema remains unstudied.

Healthy aging is associated with remodelling of the pulmonary vasculature that is characterized by a reduction in capillary density (Butler and Kleinerman, 1970) and distensibility (Reeves et al., 2005), and an increase in pulmonary vascular stiffness and resistance (Ehrsam et al., 1983; Emirgil et al., 1967; Ghali et al., 1992; Gozna et al., 1974; Hosoda et al., 1984). This, along with an increase in the heterogeneity of pulmonary perfusion (Levin et al., 2007) and a reduction in left ventricular compliance (Arbab-Zadeh et al., 2004), serves to markedly increase pulmonary vascular pressures at rest and during exercise of a similar intensity in older relative to younger humans (Ehrsam et al., 1983; Emirgil et al., 1967; Kovacs et al., 2009; Lam et al., 2009; Reeves et al., 2005). In addition, with senescence there is atrophy of lymphatic muscle cells (Gashev and Zawieja, 2010) and a reduction in the phasic contraction amplitude and frequency of thoracic lymphatic ducts, resulting in diminished intrinsic lymphatic pump function and pump flow (Gasheva et al., 2007). In combination, it is possible that the aforementioned age-related changes in the pulmonary system increase fluid flux across the pulmonary vasculature while impairing fluid clearance from the interstitial space, making older adults more susceptible to an exercise mediated accumulation of interstitial pulmonary fluid compared to younger individuals. Despite these important considerations, we are unaware of any previous study that has examined the role of healthy aging in the development of exercise-induced pulmonary edema. Accordingly, the aim of the present study was to determine whether non-sedentary healthy older adults are more susceptible to exercise-induced interstitial pulmonary edema relative to their younger counterparts. We hypothesized that exhaustive exercise would increase interstitial lung fluid to a greater extent in older compared to younger subjects, as evidenced by a greater pre- to post-exercise reduction in the alveolar-capillary membrane conductance (Dm) component of lung diffusing capacity (DLCO).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Subjects

Ten young (YNG; 27 ± 3 years) and 10 old (OLD; 69 ± 5 years) non-smoking male subjects participated in the study (Table 1). All subjects were physically active, were free from cardiovascular and lung disease, and had pulmonary function within normal limits (Table 1). The experimental procedures were approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board and each subject provided written informed consent prior to participation.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics and resting pulmonary function

| YNG | OLD | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 27 ± 3 | 69 ± 5** |

| Stature, cm | 177 ± 4 | 176 ± 4 |

| Body mass, kg | 73.9 ± 7.0 | 75.3 ± 8.1 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.6 ± 2.6 | 24.3 ± 2.7 |

| VO2peak, ml/kg/min | 54.3 ± 11.8 | 34.6 ± 9.0** |

| VO2peak, % age predicted | 130 ± 24 | 133 ± 27 |

| TLC, % predicted | 115 ± 12 | 113 ± 17 |

| FVC, % predicted | 110 ± 9 | 111 ± 21 |

| FEV1, % predicted | 107 ± 11 | 114 ± 19 |

| FEV1/FVC, % predicted | 98 ± 5 | 103 ± 8 |

| FEF25–75, % predicted | 108 ± 11 | 112 ± 23 |

Values are group means ± SD for 10 young (YNG) and 10 old (OLD) subjects. BMI, body mass index; VO2peak, peak oxygen consumption during maximal incremental exercise; TLC, total lung capacity; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FEF, forced expiratory flow.

P < 0.01, values significantly different vs. YNG group.

2.2. Experimental procedures

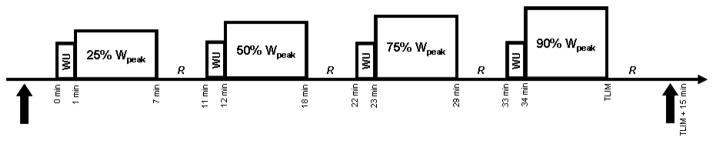

The experimental procedures were conducted during two laboratory sessions that were separated by at least 48 h but no longer than 2 weeks. The subjects abstained from caffeine for 12 h and exercise for 24 h before each session. During the first session, pulmonary function was assessed via body plethysmography (MedGraphics Elite Series Plethysmograph, Medical Graphics Corporation, St. Paul, MN, USA) according to standard procedures (Miller et al., 2005). Subjects then performed a maximal incremental exercise test (20 W every 2 min starting at either 60 W, 80 W or 100 W) on an electromagnetically braked cycle ergometer (Lode Corvial, Lode B.V. Medical Technology, Groningen, The Netherlands). Peak work rate (Wpeak) was calculated as the sum of the final completed work rate plus the fraction of the partially completed work rate performed before exhaustion. Peak O2 uptake (VO2peak) was the highest mean value recorded over the final 30 s of exercise. At the second session, subjects cycled for 6 min at 25%, 6 min at 50% and 6 min at 75% of Wpeak before cycling at 90% of Wpeak to the limit of tolerance (Fig. 1). The subjects rested quietly for 4 min between each exercise bout. Lung diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) and its component parts alveolar-capillary membrane conductance (Dm) and pulmonary capillary blood volume (Vc) were assessed before and 15 min after exercise by measuring the disappearance of small amounts of carbon monoxide (CO) and nitric oxide (NO) during a rebreathe technique (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic depiction of the exercise protocol used in this study. Subjects exercised for 6 min at 25%, 50% and 75% of peak work rate (Wpeak) then at 90% Wpeak to the limit of tolerance (TLIM). A 1 min “warm-up” (WU) at 40% of the workload about to be completed was allowed before each exercise bout and 4 min of quiet recovery (R) was given between each exercise stage. Lung diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO), alveolar-capillary membrane conductance (Dm) and pulmonary capillary blood volume (Vc) were assessed in triplicate at rest before exercise and 15 min after exercise at 90% of Wpeak via a rebreathe method (solid up arrows).

2.3. Lung diffusing capacity & alveolar-capillary membrane conductance

DLCO, Dm and Vc were assessed by simultaneously measuring the disappearance of CO and NO using a rebreathe technique, as we have described previously (Ceridon et al., 2010; Snyder et al., 2006a; Taylor et al., 2011). Subjects sat upright on the cycle ergometer and breathed through a two-way switching valve (Hans Rudolph 4285 series, Hans Rudolph, Kanas City, MO, USA) that was connected to a pneumotachometer (MedGraphics prevent Pneumotach, Medical Graphics Corporation, St. Paul, MN, USA), a mass spectrometer (Marquette 1100 Medical Gas Analyser, Perkin-Elmer, St. Louis, MO, USA) and a NO analyser (Sievers 280i NOA, Sievers, Boulder, CO, USA). The inspiratory port of the switching valve was set to either room air or a 5 L anesthesia bag that was filled with 0.3% CO (C18O), 40 parts per million (ppm) NO (diluted in the bag immediately before the rebreathe manoeuvre from an 800 ppm gas mixture), 35% O2 and N2 balance. The total volume of gas in the anesthesia bag was determined by the resting tidal volume (VT) of each subject. This was not different before vs. 15 min after exercise for either the YNG (group mean VT = 1.16 ± 0.30 vs. 1.19 ± 0.45 L) or the OLD subjects (group mean VT = 0.93 ± 0.29 vs. 0.95 ± 0.33 L). To ensure the volume of the test gas was consistent across multiple rebreathe manoeuvres the bag was filled using a timed switching circuit that, given a constant flow rate from the tank, resulted in the desired volume. The test gas volume given by the switching circuit was verified before and after exercise using a 3 L syringe. Before each rebreathe manoeuvre, the subjects were instructed to breathe normally on room air for 4–5 breaths. At the end of a normal expiration, the subjects were switched to the rebreathe bag and told to “nearly to empty the bag” with each breath for 10–12 consecutive breaths. To ensure that data could be collected over 8–10 breaths before the NO in the test gas decayed completely, the subjects maintained respiratory frequency at 32 breaths/min during each manoeuvre by following a metronome with distinct inspiratory and expiratory tones. Following each maneuver, the rebreathe bag was emptied with a vacuum pump before being refilled for the next manoeuvre. Each subject performed the rebreathe in triplicate before and 15 minutes after exercise. The post-exercise rebreathe measures were initiated 15 min after exercise and took ~6 min to complete. DLCO, Dm and Vc were computed using custom analysis software.

2.4. Exercise responses

Following the pre-exercise rebreathe maneuvers, subjects cycled at 25%, 50% and 75% of Wpeak (each for 6 min) before they cycled at 90% of Wpeak to the limit of tolerance (i.e. until they were unable to maintain pedal cadence above 60 rpm). A 1 min “warm-up” at 40% of the workload about to be completed was allowed before each exercise bout and four min of recovery was given between each exercise stage (Fig. 1). Ventilatory and pulmonary gas exchange indices were measured throughout exercise using the mass spectrometer and pneumotachometer. Heart rate (HR) and arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2) were measured beat-by-beat using a pulse oximeter (Nellcor N-595, Tyco Healthcare Group, Nellcor Puritan Bennett Division, Pleasanton, CA, USA) and a forehead sensor. Capillary blood was sampled from an earlobe at rest and during the final minute of each exercise bout for the determination of blood lactate concentration (Lactate Plus, Nova Biomedical, Waltham, MA, USA). Ratings of perceived exertion (dyspnea and leg discomfort) were obtained at rest and during the final minute of each exercise bout with Borg’s modified CR10 scale (Borg, 1998).

2.5. Statistical analyses

Independent samples t-test was used to compare subject characteristics, measures of lung function and the physiological responses to exercise at equivalent time points between the experimental groups (YNG vs. OLD). In addition, paired samples t-test was used to compare absolute values of lung diffusing capacity, alveolar-capillary membrane conductance and pulmonary capillary blood volume across time (before vs. after exercise) within each experimental group (YNG and OLD). The acceptable type-I error was set at P < 0.05. Results are expressed as group mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 12.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary exercise

During the maximal incremental exercise, Wpeak was greater in the YNG vs. the OLD group (303 ± 38 vs. 202 ± 51 W, P < 0.01). Similarly, VO2peak was greater in the YNG vs. the OLD group (3.96 ± 0.62 vs. 2.59 ± 0.69 L/min, P < 0.01) (Table 1). However, when expressed as percentage of age predicted, VO2peak was not different between the YNG and the OLD subjects (130 ± 24 vs. 133 ± 27% of predicted, P = 0.785) (Hansen et al., 1984) (Table 1).

3.2. Lung diffusing capacity & alveolar-capillary membrane conductance

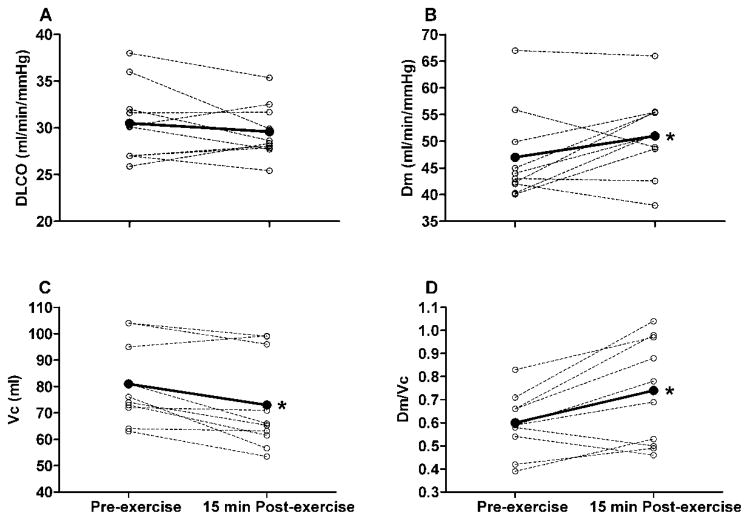

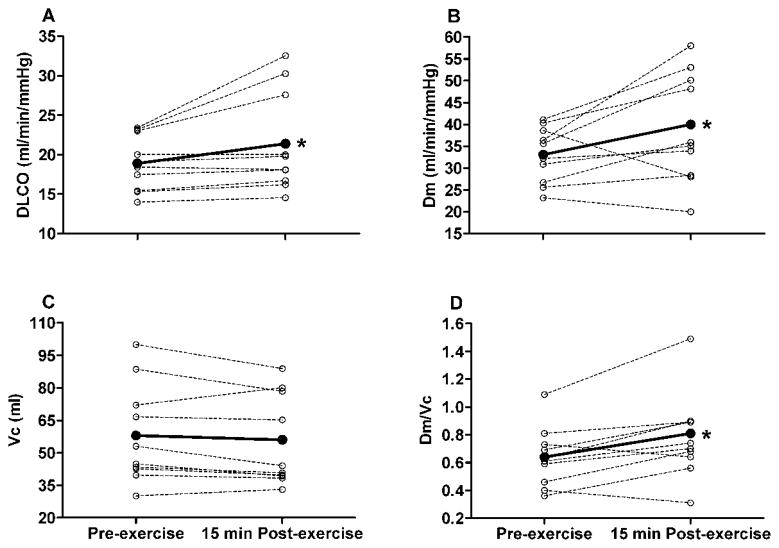

At rest, group mean DLCO, Dm and Vc were greater in the YNG vs. the OLD subjects (DLCO = 30.5 ± 4.1 vs. 18.9 ± 3.5 ml/min/mmHg, P < 0.01; Dm = 47.0 ± 8.5 vs. 33.1 ± 6.4 ml/min/mmHg, P < 0.01; Vc = 81 ± 15 vs. 58 ± 23 ml, P = 0.018). Group mean DLCO, Dm and Vc increased progressively with increasing exercise intensity in both the YNG and OLD subjects (Table 2). Similar to pre-exercise rest values, DLCO, Dm and Vc were greater in the YNG vs. the OLD subjects at each exercise time point (Table 2). In the YNG group, Dm increased (11 ± 7%, P = 0.031) whereas Vc decreased (−10 ± 9%, P = 0.01) from pre- to 15 min post-exercise (Fig. 2). Accordingly, DLCO was not different before vs. 15 min after exercise in the YNG subjects (30.5 ± 4.1 vs. 29.7 ± 2.9 ml/min/mmHg, P = 0.440) (Fig. 2). By contrast, DLCO increased from pre- to 15 min post-exercise in the OLD group (11 ± 14%, P = 0.042) (Fig. 3). This was due to an increase in Dm (16 ± 14%, P = 0.025) as there was no change in Vc (58 ± 23 vs. 56 ± 23 ml, P = 0.570) (Fig. 3). Group mean Dm corrected for Vc (Dm/Vc) was greater after compared to before exercise in both the YNG (23 ± 19%, P = 0.006) and the OLD groups (25 ± 22%, P = 0.023) (Figs. 2 and 3). There was, however, a pre- to post-exercise reduction in Dm/Vc (−7 ± 4%) that was accompanied by a reduction in DLCO (−9 ± 3%) and Dm (−11 ± 2%) in 2 of the 10 YNG subjects (Fig. 2). Similarly, Dm/Vc, DLCO and Dm were lower post-exercise relative to pre-exercise baseline values in 2 of the 10 OLD subjects (−10 ± 5%, −11 ± 4% and −8 ± 5% for Dm/Vc, DLCO and Dm, respectively) (Fig. 3). These data suggest that exercise caused a decrease in interstitial lung fluid in the majority of YNG and OLD adults, with a small number of subjects exhibiting evidence of exercise-induced interstitial pulmonary edema.

Table 2.

Lung diffusion indices at 25%, 50%, 75% and 90% of Wpeak

| YNG

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25% Wpeak | 50% Wpeak | 75% Wpeak | 90% Wpeak | |

| DLCO, ml/min/mmHg | 37 ± 7 | 41 ± 10 | 44 ± 13 | 49 ± 14 |

| Dm, ml/min/mmHg | 60 ± 12 | 62 ± 12 | 66 ± 15 | 72 ± 13 |

| Vc, ml | 99 ± 19 | 105 ± 21 | 113 ± 22 | 127 ± 20 |

| Dm/Vc | 0.61 ± 0.10 | 0.59 ± 0.09 | 0.59 ± 0.14 | 0.58 ± 0.11 |

| OLD

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25% Wpeak | 50% Wpeak | 75% Wpeak | 90% Wpeak | |

| DLCO, ml/min/mmHg | 23 ± 9* | 35 ± 6* | 38 ± 12* | 40 ± 12* |

| Dm, ml/min/mmHg | 35 ± 14* | 54 ± 11* | 57 ± 15* | 64 ± 17* |

| Vc, ml | 66 ± 16* | 90 ± 22* | 99 ± 27* | 113 ± 32* |

| Dm/Vc | 0.54 ± 0.08* | 0.59 ± 0.15 | 0.58 ± 0.14 | 0.57 ± 0.18 |

Values are group means ± SD for 10 young (YNG) and 10 old (OLD) subjects. DLCO, lung diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide; Dm, alveolar-capillary membrane conductance; Vc, pulmonary capillary blood volume.

P < 0.05, values significantly different vs. YNG subjects at same time point.

Fig. 2.

Individual subject (dashed lines) and group mean (solid lines) lung diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO), alveolar-capillary membrane conductance (Dm), pulmonary capillary blood volume (Vc) and Dm relative to Vc at rest before exercise (Pre-exercise) and 15 min after completion of exercise at 90% of Wpeak (15 min Post-exercise) in the young (YNG) adults. Group mean values for 10 subjects. *P < 0.05, group mean values significantly different before vs. after exercise.

Fig. 3.

Individual subject (dashed lines) and group mean (solid lines) lung diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO), alveolar-capillary membrane conductance (Dm), pulmonary capillary blood volume (Vc) and Dm relative to Vc at rest before exercise (Pre-exercise) and 15 min after completion of exercise at 90% of Wpeak (15 min Post-exercise) in the old (OLD) adults. Group mean values for 10 subjects. *P < 0.05, group mean values significantly different before vs. after exercise.

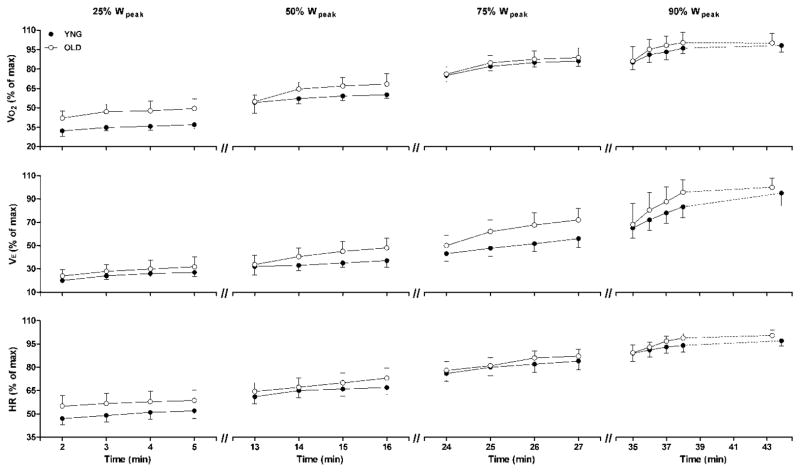

3.3. Exercise responses

Ventilatory, pulmonary gas exchange and perceptual indices at rest and in response to exercise at 90% of Wpeak are shown in Table 3. Exercise time to volitional exhaustion at 90% of Wpeak was not different in the YNG vs. the OLD group (9.87 ± 1.85 vs. 9.31 ± 1.91 min, P = 0.215). In both the YNG and OLD subjects, VO2, minute ventilation (VE) and HR increased steadily throughout exercise at 25%, 50%, 75% and 90% of Wpeak (Fig. 4). In the YNG group, VO2, VE and HR reached 98 ± 6%, 94 ± 8% and 97 ± 2% of peak values, respectively, during the final minute of exercise at 90% of Wpeak (Table 3 and Fig. 4). Similarly, VO2, VE and HR reached 99 ± 7%, 98 ± 9% and 99 ± 3% of peak values, respectively, during the final minute of exercise at 90% of Wpeak in the OLD subjects (Table 3 and Fig. 4). Arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2) was not different from rest to end-exercise in either the YNG or the OLD subjects (Table 3).

Table 3.

Ventilatory, pulmonary gas exchange and perceptual indices at rest and in response to exercise at 90% of Wpeak

| YNG | OLD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Rest | 90% Wpeak | Rest | 90% Wpeak | |

| Work rate, W | 0 ± 0 | 272 ± 34 | 0 ± 0 | 182 ± 45* |

| HR, beats/min | 70 ± 13 | 179 ± 8 | 76 ± 14* | 164 ± 1* |

| HR, % of max | 38 ± 4 | 97 ± 2 | 46 ± 9* | 99 ± 3 |

| SaO2, % | 99.3 ± 0.7 | 96.8 ± 1.5 | 99.4 ± 0.7 | 96.0 ± 2.2 |

| [Lac−]B, mmol/L | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 10.1 ± 1.0 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 9.0 ± 1.7* |

| VE, L/min | 14 ± 4 | 155 ± 26 | 16 ± 11 | 117 ± 20* |

| VE, % of max | 8 ± 2 | 94 ± 8 | 13 ± 5 | 98 ± 9 |

| VT, L | 0.92 ± 0.19 | 3.02 ± 0.4 | 0.96 ± 0.39 | 2.86 ± 0.61 |

| fR, breaths/min | 16 ± 5 | 52 ± 7 | 17 ± 6 | 42 ± 9* |

| VO2, L/min | 0.38 ± 0.07 | 3.80 ± 0.56 | 0.33 ± 0.06 | 2.52 ± 0.61* |

| VO2, % of max | 10 ± 3 | 98 ± 6 | 13 ± 4 | 99 ± 7 |

| VCO2, L/min | 0.31 ± 0.07 | 4.42 ± 0.53 | 0.30 ± 0.07 | 3.00 ± 0.64* |

| RER | 0.81 ± 0.13 | 1.17 ± 0.06 | 0.89 ± 0.08 | 1.20 ± 0.07 |

| VE/VO2 | 39 ± 15 | 41 ± 4 | 37 ± 4 | 47 ± 9* |

| VE/VCO2 | 40 ± 11 | 35 ± 4 | 42 ± 4 | 39 ± 6 |

| PETCO2, mmHg | 34.5 ± 5.6 | 33.0 ± 3.5 | 34.5 ± 3.4 | 30.2 ± 3.9 |

| RPE (dyspnea), CR10 | 0 ± 0 | 9.0 ± 1.8 | 0 ± 0 | 8.9 ± 1.2 |

| RPE (legs), CR10 | 0 ± 0 | 8.8 ± 1.1 | 0 ± 0 | 8.7 ± 1.9 |

Values are group means ± SD for 10 young (YNG) and 10 old (OLD) subjects. HR, heart rate; SaO2, arterial oxygen saturation; [Lac−]B, blood lactate concentration; VE, minute ventilation; VT, tidal volume; fR, respiratory frequency; VO2, oxygen consumption; VCO2, carbon dioxide production; RER, respiratory exchange ration; PETCO2, partial pressure of end-tidal CO2; RPE, rating of perceived exertion.

P < 0.05, values significantly different vs. YNG subjects at same time point.

Fig. 4.

Oxygen consumption (VO2, top row of panels), minute ventilation (VE, middle row of panels) and heart rate (HR, bottom rom of panels) expressed as a percentage of maximum values during exercise at 25%, 50%, 75% and 90% of peak work rate (Wpeak) in young (YNG, closed circles) and old (OLD, open circles) subjects. Values are group mean ± SD for 10 subjects in each group.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main findings

The main finding of this study was that dynamic cycle exercise improved conductance across the alveolar-capillary barrier in the majority of non-sedentary young (YNG) and old (OLD) healthy adults, as evidenced by a ~23–25% increase in alveolar-capillary membrane conductance relative to pulmonary capillary blood volume (Dm/Vc). There was, however, a decrease in Dm/Vc that was accompanied by a reduction in lung diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) in two of the ten YNG and two of the ten OLD subjects; the reduction in Dm/Vc was similar between these YNG and the OLD subjects (~−7 vs. −10%). In combination, these data suggest that exercise causes a decrease in interstitial lung fluid in most non-sedentary YNG and OLD subjects, with a small number of individuals exhibiting evidence of exercise-induced interstitial pulmonary edema. Overall, these findings imply that healthy aging in non-sedentary individuals does not increase susceptibility to an accumulation of extravascular lung fluid from pre- to post-exercise at sea-level in humans.

4.2. Technical considerations

4.2.1. Exercise intensity and duration

One consideration with the present finding is whether or not the demand placed on the pulmonary vasculature during exercise was great enough to disturb lung fluid balance such that interstitial pulmonary fluid would have accumulated in our subjects. That is, if the exercise intensity used did not elevate cardiac output and pulmonary capillary pressure sufficiently to cause a substantial increase in fluid flux from the pulmonary vasculature to the interstitial space then it would perhaps be unsurprising if pulmonary edema was not present after exercise in our young and old adults (Zavorsky, 2007). In the present study, the subjects performed cycle exercise at 75% of Wpeak for 6 minutes before maintaining exercise at 90% of Wpeak to the limit of tolerance (~9.87 min for the YNG subjects and ~9.31 min for the OLD subjects). Moreover, VO2 was maintained at ≥85% of VO2peak for 4 min whilst cycling at 75% of Wpeak and at ≥95% of VO2peak for ~7 min whilst cycling at 90% of Wpeak in both the YNG and OLD subjects (Fig. 4). Based on these considerations, we are confident that the exercise performed in the present study was of sufficient intensity and duration to elicit interstitial pulmonary edema (Zavorsky, 2007), a contention that is supported by the fact that we found evidence of exercise-induced pulmonary edema in two of our YNG and two of our OLD subjects. The physiological factors that may explain why exercise caused an increase extravascular lung fluid in some but not all of our subjects are discussed in detail below (see 4.6. A question of individual susceptibility).

4.2.2. Post exercise time to measurement

A further consideration is that the time elapsed between the end of exercise and the post-exercise measures of lung diffusing capacity and alveolar-capillary membrane conductance may have influenced our primary finding. It is likely that any measure of DLCO and Dm made immediately after exercise would be significantly increased secondary only to the exercise-induced increase in Vc, potentially masking any pulmonary edema mediated post-exercise reduction in lung diffusing capacity. Accordingly, we assessed DLCO, Dm and Vc 15 min after exercise to allow pulmonary blood flow/pulmonary capillary blood volume to return to resting baseline values (Manier et al., 1999a). However, it is also conceivable that an exercise-induced increase in interstitial lung fluid may have recovered during this time. Despite this concern, it has been shown previously that pulmonary edema remains present up to 90 minutes after exercise in healthy women (3 × 5 min cycle exercise, average VO2 ~91% of maximum) (Zavorsky et al., 2006a) and in aerobically trained men (45 min cycle exercise at ~76% of VO2max) (McKenzie et al., 2005). Accordingly, we are confident that our finding of limited evidence of an increase in interstitial lung fluid after exhaustive exercise in the majority of young and old subjects was relevant to the exercise protocol itself and not the result of the time taken between exercise termination and the rebreathe assessment of lung diffusing capacity and alveolar-capillary membrane conductance.

4.3. Comparison to previous studies

Whether interstitial pulmonary edema develops in response to sea-level exercise in healthy humans remains controversial and extensively debated (Hopkins et al., 2010). In the present study, we determined whether exhaustive cycle exercise caused changes in extravascular lung fluid in young and old adults by assessing by DLCO and its component parts Dm and Vc. Specifically, we considered that a pre- to post-exercise increase in interstitial lung water would be reflected by a diffusion limitation relating to the pulmonary membrane (i.e. a reduction in Dm relative to Vc). Contrary to our hypothesis, group mean Dm/Vc increased by ~23% and ~25% from before to after exercise in the non-sedentary YNG and OLD subjects, respectively, suggesting that interstitial lung fluid was decreased post-exercise in most of the subjects studied (Figs. 3 and 4). We did, however, find a ~7% and a ~10% reduction in Dm/Vc that was accompanied by a decrease in DLCO in two of the ten YNG and two of the ten OLD subjects, respectively. These findings are in agreement with some but not all previous studies. For example, Manier et al. (Manier et al., 1999a) found no change in CT derived lung density after 2 h of running exercise maintained at 75% of VO2peak in any of the 9 male athletes (VO2max = 66 ± 5 ml/min/kg) assessed. By contrast, McKenzie et al. (McKenzie et al., 2005) reported a post-exercise increase in MRI determined extravascular lung water in response to 45 min of cycle exercise at ~76% of VO2max 4 of the 8 trained male cyclists (VO2max = 64 ± 3 ml/min/kg) studied. Moreover, Zavorsky et al. (Zavorsky et al., 2006a) demonstrated that repeated bouts of heavy cycle exercise (3 × 5 min, average VO2 ~91% of maximum) either increased (n = 9), decreased (n = 4) or did not affect (n = 1) pulmonary edema score (via chest radiographs) in healthy women. The aforementioned findings, in combination with the findings of the present study, support the notion that exercise induces interstitial pulmonary edema in healthy humans at sea-level only in a specific sub-set of people susceptible to this phenomenon.

4.4. Why is advanced age not associated with increased susceptibility to exercise-induced interstitial pulmonary edema at sea-level?

The volume of extravascular lung fluid is regulated by both passive and active forces between the pulmonary capillaries and the interstitial space, as described by the Starling equation (Starling, 1896). While fluid flux across the pulmonary vasculature is determined by the balance between the hydrostatic pressure in the pulmonary capillaries and the hydrostatic pressure in the interstitial space as well as the permeability of the pulmonary capillaries to fluid, fluid clearance from the interstitial space is largely dependent on the activity of the pulmonary lymphatics. Presently, we theorized that healthy aging would be associated with a substantial disturbance in these lung fluid balance mechanisms, thus making older adults more susceptible to exercise-induced interstitial pulmonary edema relative to their younger counterparts, for three primary reasons. First, with senescence there is an increase in pulmonary vascular stiffness (Gozna et al., 1974; Harris et al., 1965; Hosoda et al., 1984) and a decrease in pulmonary vascular distensibility (Reeves et al., 2005) that is likely mediated by an increase in collagen content and/or a decrease in elastin content of the pulmonary blood vessels (Harris et al., 1965; Hosoda et al., 1984). These changes, along with a reduction in both pulmonary capillary density (Butler and Kleinerman, 1970) and left ventricular compliance (Arbab-Zadeh et al., 2004) serve to markedly increase pulmonary vascular resistance and pulmonary vascular pressures at rest and during exercise of a similar intensity in older relative to younger humans (Ehrsam et al., 1983; Emirgil et al., 1967; Kovacs et al., 2009; Lam et al., 2009). Second, pulmonary blood flow distribution typically becomes more heterogeneous during heavy, sustained exercise in healthy humans with a resultant regional overperfusion of some pulmonary capillary beds (Burnham et al., 2009). Such overperfusion may, in some regions, exceed the distension capacity of the pulmonary capillaries with a subsequent increase in pulmonary capillary pressure. Recent evidence has suggested that, like the distribution of alveolar ventilation, the heterogeneity of pulmonary perfusion also increases with advancing age (Levin et al., 2007). These over-perfused lung regions, in the setting of attenuated pulmonary capillary distensibility, likely cause a further increase in regional pulmonary capillary pressures during exercise in older adults compared to their younger counterparts. These increases in pulmonary vascular pressure may facilitate a greater degree of mechanical stress and fluid leakage from the pulmonary vasculature in aged individuals relative to younger subjects. Finally, it is possible that healthy aging is associated with impairment of lymphatic clearance of extravascular lung fluid. In the healthy lung, fluid that moves from the pulmonary capillaries to the pulmonary interstitium tracks through the interstitial space to the low pressure perivascular spaces. This extravascular fluid is then cleared from this “natural sump” to the hilar lymph nodes via intrinsic contractions of the thoracic lymphatic ducts. However, with healthy aging (>65 years) there is a significant reduction in the number of lymphatics and the number of connections between lymphatics in the human mesentery (Gashev and Zawieja, 2010); whether this also occurs in the thoracic duct is unknown. In addition, with senescence there is significant atrophy of lymphatic muscle cells in the thoracic duct walls in humans (Gashev and Zawieja, 2010). Theoretically, this age-dependent weakening of the thoracic lymphatic musculature may greatly impair the phasic contraction amplitude and frequency of thoracic lymphatic ducts and thus significantly reduce the ability to generate lymphatic flow and promote lung fluid clearance, as has been shown in aged animal models (Gasheva et al., 2007). Taken in combination, we postulated that the aforementioned age-related changes in the pulmonary system would act synergistically to increase fluid flux across the pulmonary vasculature while impairing fluid clearance from the interstitial space, thus making older adults more susceptible to an exercise mediated accumulation of pulmonary interstitial fluid compared to younger individuals.

So why does it appear that non-sedentary healthy older adults are not more susceptible to exercise-induced pulmonary edema at sea-level compared to their younger counterparts? First, it is important to note that an increase in pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP) during exercise does not always cause an increase in lung fluid. During even moderate intensity exercise, mean PAP can increase by ~60% in younger adults (< 50 years) and by ~120% in humans aged > 50 years, often reaching values in excess of 30 mmHg (Kovacs et al., 2009). Thus, although not measured, it is highly likely that both mean PAP and pulmonary capillary pressure were significantly elevated in response to exercise in both the present study and in previous studies that reported either no change or a reduction in extravascular lung water after exercise in some subjects (Hodges et al., 2007; Manier et al., 1999a; McKenzie et al., 2005). Accordingly, it is likely that the age-related increase in pulmonary vascular pressures during exercise secondary to remodelling of the pulmonary vasculature is not sufficient, at least in isolation, to substantially increase susceptibility to exercise-induced pulmonary edema. Second, it has been shown previously that permeability of the pulmonary microvasculature is decreased in chronic left heart failure patients, likely secondary to a thickening of the pulmonary vascular walls in the face of chronic pulmonary hypertension (Davies et al., 1992). Although speculative, it is possible that the age-related augmentation of pulmonary vascular pressures elicit a similar reduction in microvascular permeability, thus providing protection against fluid extrusion into the interstitial space in aged adults. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, it is clear that increased thoracic lymphatic flow during exercise is dependent of extrinsic as well as intrinsic factors. Indeed, it has been shown that, much like the skeletal muscle pump, the intrathoracic pressure oscillations associated with inspiration and expiration act to increase flow through the pulmonary lymphatics (Drake et al., 1982; Parker et al., 1985). Moreover, it is likely that the exercise-mediated increase in circulating catecholamines increases pulmonary lymphatic pressure and flow via stimulation α and β receptors in the pulmonary lymphatic tissue (Ohhashi et al., 1978). Based on our current findings, it seems likely that any age associated increase in fluid flux into the pulmonary interstitium is at least matched, if not bettered, by the rate of fluid clearance from the interstitial space during exhaustive exercise resulting in a net loss of extravascular lung water in the majority of non-sedentary young and old individuals.

4.5. A possible role for cardio-respiratory fitness in exercise-induced pulmonary edema with aging

A further consideration is what effect if any cardiorespiratory fitness level may have on the incidence of exercise-induced intestinal pulmonary edema in older adults. Senescence is commonly associated with a reduction in maximal aerobic capacity secondary to reductions in maximal heart rate, ejection fraction and cardiac output (Goldspink, 2005). If this reduction occurs at a rate equal to or greater than the age-associated deterioration in pulmonary vascular structure and function, then it would be expected that the demand placed on the pulmonary vasculature during exercise (i.e. elevated cardiac output and pulmonary vascular pressures) may be lowered sufficiently enough that lung fluid balance is not disturbed in healthy aged adults. Theoretically, however, maintenance of aerobic fitness level through conditioning may cause the demand for cardiac output during heavy exercise to remain elevated thus causing pulmonary blood flow to be higher in highly fit older subjects relative to their less fit counterparts. Such maintenance of pulmonary blood flow in the face of an age-related increase in pulmonary vascular stiffness and decrease in pulmonary vascular distensibility and pulmonary capillary density would likely further increase pulmonary vascular pressures and may predispose highly fit aged individuals to an exercise-induced accumulation of extravascular lung fluid. In direct contrast, however, it is also possible the physiological adaptations associated with habitual exercise may in fact protect the aged adult from exercise-induced pulmonary edema. Indeed, it has been shown that sustained exercise training both ameliorates the increase in left ventricular stiffness (Arbab-Zadeh et al., 2004) with aging and preserves myocardial relation (Kivisto et al., 2006). Moreover, participation in regular exercise by previously sedentary individuals has been shown to reduce stiffness of the large elastic arteries (Seals et al., 2009). While it is unclear whether such conditioning has a similar effect on the pulmonary artery, any such reduction in pulmonary vascular stiffness along with a reduction in left ventricular stiffness would allow cardiac output and pulmonary blood flow to increase during exercise without large increases in pulmonary pressures and pulmonary vascular resistance, thus reducing the risk of interstitial pulmonary edema. Given that the group mean maximal aerobic capacity of the OLD subjects in this study was greater than 100% of age predicted (VO2peak = 133 ± 27% of age predicted, range 96 – 167%), the aforementioned considerations regarding cardiorespiratory fitness level and exercise-induced edema may be particularly relevant. However, of the 10 OLD subjects studied, four had a VO2peak of ≤107% of age predicted and only five had an exceedingly high VO2peak (>140% age predicted). Moreover, with specific regards to the two OLD subjects who did exhibit evidence of exercise-induced pulmonary, one had a normal cardiorespiratory fitness level (VO2peak 107% age predicted) whereas the other had an elevated maximal exercise capacity (VO2peak 141% age predicted). Accordingly, although based on this somewhat limited data set, the present findings suggest that maintenance of aerobic fitness neither increases nor decreases the susceptibility of aged adults to exercise-induced interstitial pulmonary edema. However, whether the occurrence of pulmonary edema in response to exercise at sea-level is different in highly fit older adults compared to their truly sedentary counterparts remains a pertinent question and requires further investigation.

4.6. A question of individual susceptibility

Our findings in combination with those reported previously suggest that while the rate of pulmonary capillary fluid extrusion during dynamic exercise is matched or bettered by the rate of fluid removal from the pulmonary interstitium in the majority of healthy humans, there are some individuals who do develop interstitial pulmonary edema in response to whole-body exercise (McKenzie et al., 2005; Zavorsky et al., 2006a). Thus, the pertinent question is not whether exercise can induce interstitial pulmonary edema at sea-level but rather what are the contributing factors that make an individual more susceptible to such pulmonary edema with exertion. Unlike the occurrence of high-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE), our current understanding of the risk factors that may predispose humans to the development of exercise-induced interstitial pulmonary edema at sea-level are limited. For example, it has been established that HAPE susceptible individuals typically demonstrate an abnormally large increase in PAP in response to hypoxic exposure at rest and during exercise (Eldridge et al., 1996; Grunig et al., 2000; Hultgren et al., 1971; Mounier et al., 2011). However, as noted above, it is clear that the increase in PAP associated with exercise at sea-level alone does not always result in interstitial pulmonary edema following exertion (Hodges et al., 2007; Manier et al., 1999a; Zavorsky et al., 2006a). Interestingly, individuals susceptible to HAPE also have an exaggerated rise in PAP during normoxic exercise relative to non-HAPE susceptible individuals, demonstrating a generalized hyperreacticity of the pulmonary vasculature in HAPE susceptible subjects (Grunig et al., 2000). Although it is intuitive to assume that individuals who experience the largest increases in PAP during normoxic exercise are also more susceptible to exercise-induced interstitial pulmonary edema at sea-level, whether this is the case remains largely unknown. It has also been shown that HAPE susceptible individuals tend to have smaller lung volumes compared to non-HAPE susceptible subjects (Eldridge et al., 1996; Podolsky et al., 1996). For example, Eldridge et al. (Eldridge et al., 1996) demonstrated that FVC was ~1 L less in HAPE susceptible individuals relative to control subjects despite both groups being of similar age, height and weight. It is likely that a smaller lung volume is associated with a smaller pulmonary vascular cross-sectional area and a resultant increase in pulmonary blood flow velocity and pulmonary vascular pressures that may facilitate transcapillary fluid leakage or even vascular stress failure. By contrast, however, Zavorsky et al. (Zavorsky et al., 2006a) found that the development of post-exercise pulmonary edema was not related to lung volume in 14 females. Moreover, in the present study, the 2 YNG and 2 OLD subjects who did exhibit evidence of exercise-induced pulmonary edema all had a FVC that was similar to or great than their respective groups mean (YNG, 6.31 and 7.23 vs. group mean 6.02 L; OLD, 4.83 and 5.59 vs. group mean 4.79 L). Accordingly, it would appear that unlike the incidence of HAPE, small lung volumes do not increase an individual’s susceptibility to exercise-induced interstitial pulmonary edema at sea-level. Finally, it is possible that genetic variability contributes somewhat to the occurrence of pulmonary edema after exertion at sea-level. The β2-adrenergic receptors (β2-ARs) are located throughout the body including the lungs, the airways, the pulmonary vasculature, and the pulmonary lymphatic tissue, and appear to be heavily involved in lung fluid regulation (Davis et al., 1979; Sartori et al., 2002). Moreover, previous investigations have suggested that lung fluid accumulation is somewhat dependent on β2-AR genotype (Snyder et al., 2006b). More specifically, it has been shown that individuals homozygous for glycine at amino acid 16 of the β2-ARs have an attenuated natriuretic response to intravenous saline infusion compared to subjects homozygous for arginine at that position (Snyder et al., 2006b). Thus, although somewhat speculative, it is possible that lung fluid clearance is impaired during exercise in individuals homozygous for glycine amino acid 16 of the β2-ARs. As such, these subjects may have heightened susceptibility to exercise-induced interstitial pulmonary edema at sea-level. Despite the aforementioned considerations, the factors that underpin the development of exercise-induced pulmonary edema at sealevel certainly remain unclear and require further investigation. The present findings, however, suggest that aging does not increase susceptibility to interstitial pulmonary edema following exertion at sea-level in healthy humans.

4.7. Conclusion

In conclusion, we found that exhaustive cycle exercise performed at sea-level decreased extravascular lung fluid in the majority of non-sedentary young and old healthy adults. We did, however, observe limited evidence of exercise-induced interstitial pulmonary edema in healthy aged adults that was similar in prevalence and magnitude to that found in younger subjects. Overall, we propose that the healthy lung is well designed for sea-level exercise in old as well as young subjects and that healthy aging does not increase susceptibility to exercise-induced interstitial pulmonary edema at sea-level in humans.

Highlights.

Healthy aging is associated with remodeling of the pulmonary vasculature

These changes may increase susceptibility to exercise-induced pulmonary edema

Lung diffusing capacity was assessed before and after exhaustive exercise in young and old men

Evidence for exercise-induced pulmonary edema was found in only a small number of young and old subjects.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Joshua O’Malley for technical help.

Funding

This study was funded by NIH grant HL71478. BJT is supported by AHA grant 12POST12070084.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arbab-Zadeh A, Dijk E, Prasad A, Fu Q, Torres P, Zhang R, Thomas JD, Palmer D, Levine BD. Effect of aging and physical activity on left ventricular compliance. Circulation. 2004;110:1799–1805. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000142863.71285.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates ML, Farrell ET, Eldridge MW. The curious question of exercise-induced pulmonary edema. Pulm Med. 2011;2011:361931. doi: 10.1155/2011/361931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borg G. Borg’s Perceived Exertion abd Pain Scales. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Brasileiro FC, Vargas FS, Kavakama JI, Leite JJ, Cukier A, Prefaut C. High-resolution CT scan in the evaluation of exercise-induced interstitial pulmonary edema in cardiac patients. Chest. 1997;111:1577–1582. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.6.1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnham KJ, Arai TJ, Dubowitz DJ, Henderson AC, Holverda S, Buxton RB, Prisk GK, Hopkins SR. Pulmonary perfusion heterogeneity is increased by sustained, heavy exercise in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2009;107:1559–1568. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00491.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler C, 2nd, Kleinerman J. Capillary density: alveolar diameter, a morphometric approach to ventilation and perfusion. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1970;102:886–894. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1970.102.6.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caillaud C, Serre-Cousine O, Anselme F, Capdevilla X, Prefaut C. Computerized tomography and pulmonary diffusing capacity in highly trained athletes after performing a triathlon. Journal of applied physiology. 1995;79:1226–1232. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.4.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceridon ML, Beck KC, Olson TP, Bilezikian JA, Johnson BD. Calculating alveolar capillary conductance and pulmonary capillary blood volume: comparing the multiple- and single-inspired oxygen tension methods. J Appl Physiol. 2010;109:643–653. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01411.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies SW, Bailey J, Keegan J, Balcon R, Rudd RM, Lipkin DP. Reduced pulmonary microvascular permeability in severe chronic left heart failure. Am Heart J. 1992;124:137–142. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(92)90931-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis B, Marin MG, Yee JW, Nadel JA. Effect of terbutaline on movement of Cl− and Na+ across the trachea of the dog in vitro. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1979;120:547–552. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1979.120.3.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, Adcock DK, Scott RL, Gabel JC. Effect of Outflow Pressure Upon Lymph-Flow from Dog Lungs. Circ Res. 1982;50:865–869. doi: 10.1161/01.res.50.6.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrsam RE, Perruchoud A, Oberholzer M, Burkart F, Herzog H. Influence of age on pulmonary haemodynamics at rest and during supine exercise. Clin Sci (Lond) 1983;65:653–660. doi: 10.1042/cs0650653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldridge MW, Braun RK, Yoneda KY, Walby WF. Effects of altitude and exercise on pulmonary capillary integrity: evidence for subclinical high-altitude pulmonary edema. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100:972–980. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01048.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldridge MW, Podolsky A, Richardson RS, Johnson DH, Knight DR, Johnson EC, Hopkins SR, Michimata H, Grassi B, Feiner J, Kurdak SS, Bickler PE, Wagner PD, Severinghaus JW. Pulmonary hemodynamic response to exercise in subjects with prior high-altitude pulmonary edema. J Appl Physiol. 1996;81:911–921. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.2.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emirgil C, Sobol BJ, Campodonico S, Herbert WH, Mechkati R. Pulmonary circulation in the aged. J Appl Physiol. 1967;23:631–640. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1967.23.5.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher CG, Huda W, Rigby M, Greenberg D, Younes M. Lack of radiographic evidence of interstitial pulmonary edema after maximal exercise in normal subjects. The American review of respiratory disease. 1988;137:474–476. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/137.2.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gashev AA, Zawieja DC. Hydrodynamic regulation of lymphatic transport and the impact of aging. Pathophysiology : the official journal of the International Society for Pathophysiology / ISP. 2010;17:277–287. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasheva OY, Knippa K, Nepiushchikh ZV, Muthuchamy M, Gashev AA. Age-related alterations of active pumping mechanisms in rat thoracic duct. Microcirculation. 2007;14:827–839. doi: 10.1080/10739680701444065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghali JK, Liao Y, Cooper RS, Cao G. Changes in pulmonary hemodynamics with aging in a predominantly hypertensive population. Am J Cardiol. 1992;70:367–370. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(92)90621-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldspink DF. Ageing and activity: their effects on the functional reserve capacities of the heart and vascular smooth and skeletal muscles. Ergonomics. 2005;48:1334–1351. doi: 10.1080/00140130500101247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gozna ER, Marble AE, Shaw A, Holland JG. Age-related changes in the mechanics of the aorta and pulmonary artery of man. J Appl Physiol. 1974;36:407–411. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1974.36.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunig E, Mereles D, Hildebrandt W, Swenson ER, Kubler W, Kuecherer H, Bartsch P. Stress Doppler echocardiography for identification of susceptibility to high altitude pulmonary edema. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:980–987. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00633-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen JE, Sue DY, Wasserman K. Predicted Values for Clinical Exercise Testing. American Review of Respiratory Disease. 1984;129:S49–S55. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1984.129.2P2.S49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris P, Heath D, Apostolopoulos A. Extensibility of the human pulmonary trunk. Br Heart J. 1965;27:651–659. doi: 10.1136/hrt.27.5.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges AN, Sheel AW, Mayo JR, McKenzie DC. Human lung density is not altered following normoxic and hypoxic moderate-intensity exercise: implications for transient edema. J Appl Physiol. 2007;103:111–118. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01087.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins SR, Sheel AW, McKenzie DC. Point:Counterpoint: Pulmonary edmea does/does not occur in human athletes performing heavy sea-level exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2010;109:1270–1275. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01353.2009a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosoda Y, Kawano K, Yamasawa F, Ishii T, Shibata T, Inayama S. Age-dependent changes of collagen and elastin content in human aorta and pulmonary artery. Angiology. 1984;35:615–621. doi: 10.1177/000331978403501001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hultgren HN, Grover RF, Hartley LH. Abnormal circulatory responses to high altitude in subjects with a previous history of high-altitude pulmonary edema. Circulation. 1971;44:759–770. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.44.5.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivisto S, Perhonen M, Holmstrom M, Lauerma K. Assessment of the effect of endurance training on left ventricular relaxation with magnetic resonance imaging. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2006;16:321–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2005.00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs G, Berghold A, Scheidl S, Olschewski H. Pulmonary arterial pressure during rest and exercise in healthy subjects: a systematic review. Eur Respir J. 2009;34:888–894. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00145608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam CS, Borlaug BA, Kane GC, Enders FT, Rodeheffer RJ, Redfield MM. Age-associated increases in pulmonary artery systolic pressure in the general population. Circulation. 2009;119:2663–2670. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.838698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin DL, Buxton RB, Spiess JP, Arai T, Balouch J, Hopkins SR. Effects of age on pulmonary perfusion heterogeneity measured by magnetic resonance imaging. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102:2064–2070. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00512.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manier G, Duclos M, Arsac L, Moinard J, Laurent F. Distribution of lung density after strenuous, prolonged exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1999;87:83–89. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall BE, Teichner RL, Kallos T, Sugerman HJ, Wyche MQ, Jr, Tantum KR. Effects of posture and exercise on the pulmonary extravascular water volume in man. J Appl Physiol. 1971;31:375–379. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1971.31.3.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie DC, O’Hare TJ, Mayo J. The effect of sustained heavy exercise on the development of pulmonary edema in trained male cyclists. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2005;145:209–218. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, Crapo R, Enright P, van der Grinten CP, Gustafsson P, Jensen R, Johnson DC, MacIntyre N, McKay R, Navajas D, Pedersen OF, Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Wanger J. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:319–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mounier R, Amonchot A, Caillot N, Gladine C, Citron B, Bedu M, Chirico E, Coudert J, Pialoux V. Pulmonary arterial systolic pressure and susceptibility to high altitude pulmonary edema. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2011;179:294–299. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohhashi T, Kawai Y, Azuma T. Response of Lymphatic Smooth Muscles to Vasoactive Substances. Pflug Arch Eur J Phy. 1978;375:183–188. doi: 10.1007/BF00584242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker DE, Reschke MF, Arrott AP, Homick JL, Lichtenberg BK. Otolith Tilt-Translation Reinterpretation Following Prolonged Weightlessness - Implications for Preflight Training. Aviat Space Envir Md. 1985;56:601–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podolsky A, Eldridge MW, Richardson RS, Knight DR, Johnson EC, Hopkins SR, Johnson DH, Michimata H, Grassi B, Feiner J, Kurdak SS, Bickler PE, Severinghaus JW, Wagner PD. Exercise-induced VA/Q inequality in subjects with prior high-altitude pulmonary edema. J Appl Physiol. 1996;81:922–932. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.2.922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves JT, Linehan JH, Stenmark KR. Distensibility of the normal human lung circulation during exercise. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288:L419–425. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00162.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartori C, Allemann Y, Duplain H, Lepori M, Egli M, Lipp E, Hutter D, Turini P, Hugli O, Cook S, Nicod P, Scherrer U. Salmeterol for the prevention of high-altitude pulmonary edema. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1631–1636. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seals DR, Walker AE, Pierce GL, Lesniewski LA. Habitual exercise and vascular ageing. J Physiol. 2009;587:5541–5549. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.178822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder EM, Beck KC, Hulsebus ML, Breen JF, Hoffman EA, Johnson BD. Short-term hypoxic exposure at rest and during exercise reduces lung water in healthy humans. J Appl Physiol. 2006a;101:1623–1632. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00481.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder EM, Turner ST, Joyner MJ, Eisenach JH, Johnson BD. The Arg16Gly polymorphism of the beta2-adrenergic receptor and the natriuretic response to rapid saline infusion in humans. J Physiol. 2006b;574:947–954. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.107672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starling EH. On the Absorption of Fluids from the Connective Tissue Spaces. J Physiol. 1896;19:312–326. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1896.sp000596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor BJ, Kjaergaard J, Snyder EM, Olson TP, Johnson BD. Pulmonary capillary recruitment in response to hypoxia in healthy humans: a possible role for hypoxic pulmonary venoconstriction? Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2011;177:98–107. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younes M, Bshouty Z, Ali J. Longitudinal distribution of pulmonary vascular resistance with very high pulmonary blood flow. J Appl Physiol. 1987;62:344–358. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1987.62.1.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavorsky GS. Evidence of pulmonary oedema triggered by exercise in healthy humans and detected with various imaging techniques. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2007;189:305–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2006.01660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavorsky GS, Saul L, Decker A, Ruiz P. Radiographic evidence of pulmonary edema during high-intensity interval training in women. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2006;153:181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]