Summary

The ketogenic diet is a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet long used to treat refractory epilepsy; ketogenesis (ketone body formation) is a physiological phenomenon also observed in patients following low-carbohydrate, low-calorie diets prescribed for rapid weight loss.

We report the case of a pair of twin sisters, whose high-frequency migraine improved during a ketogenic diet they followed in order to lose weight.

The observed time-lock between ketogenesis and migraine improvement provides some insight into how ketones act to improve migraine.

Keywords: ketogenic diet, migraine, prophylaxis, weight loss

Introduction

The ketogenic diet (KD) was introduced in 1921 to improve drug-resistant epilepsy (Wheless, 2008), but its benefits in other neurological disorders, such as migraine, remain unclear (Maggioni et al., 2011). From the 1970s, many physicians proposed modified KD regimens, characterized by low-carbohydrate and lowfat intake (adipose tissue catabolism accounted for the ketone body production), as a means of achieving rapid weight loss since this is promoted by the anorectic effect of ketosis and protein-induced sense of satiety (Astrup et al., 2004). We describe the case of two twin sisters whose high-frequency migraine was found to benefit from a weight-loss KD. This accidental, retrospective observation prompted us to hypothesise that a KD might be useful for migraine patients.

Case report

Two 47-year-old twin sisters (Patients 1 and 2), were brought to our attention by their nutritionist because their high-frequency migraine without aura had unexpectedly vanished during a weight-loss KD.

Before starting the diet, both patients experienced an average of 5–6 attacks/month of severe throbbing headache, of up to 72 hours’ duration; the severity was increased by movement and the attacks were accompanied by photophonophobia, nausea and, very occasionally, vomiting. In the past, they had tried several prophylactic treatments for their migraine; all of these had been discontinued (more than one year previously) because of undesired weight gain and/or ineffectiveness. Fortunately, however, both women had continued to fill in their headache diaries, which showed that their migraine had never become chronic (>15 days/month), and that they had never fulfilled the criteria for medication overuse headache (MOH), a clinical condition in which the high number of symptomatic analgesics taken to treat headache attacks turns into the cause of pain chronification (Olesen et al., 2006).

Wanting to lose weight – both women have a height of 165 cm; Patient 1 weighed 78 kg with a body mass index (BMI) of 28.65, while Patient 2 weighed 73 kg with a BMI of 26.81 –, they consulted a nutritionist who prescribed a weight-loss KD (<1 g/kg/day carbohydrates; 1.2–1.6 g/kg/day proteins) comprising three daily meals consisting of ad hoc developed dietary products (meal replacements by S.D.M., Genola, Italy), plus one daily meal of meat (200 g) or fish (350 g), and nutraceutical integrators (Table I, over). Salads were allowed ad libitum dressed with a spoonful of olive oil. Urine testing sticks, used daily, confirmed ketogenesis. According to the S.D.M. guidelines, the S.D.M. diet was adopted for repeated 4-week cycles separated by two-month intervals during which the patients followed a transitional low-calorie, non-ketogenic low-carbohydrate diet. During ketogenesis, the patients were under medical supervision and had laboratory blood tests every two weeks (alanine amino-transferase, aspartate aminotransferase, gamma glutamic transpeptidase, lactic dehydrogenase, alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin, blood urea nitrogen and creatinine), which were always normal. After the third transitional period, a balanced diet was prescribed to allow the patients to maintain their new weight (Patient 1: 58 kg, BMI 21.30; Patient 2: 59 kg, BMI 21.67).

Table I.

Daily supplements of micronutrients taken by the patients.

| daily dose | daily dose | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Vit A | 800 mcg | Vit C | 60 mg |

| Vit B1 | 1.4 mg | Vit D | 5 mcg |

| Vit B2 | 1.6 mg | Vit E | 10 mg |

| Vit B3 | 18 mg | Ca | 800 mg |

| Vit B5 | 6 mg | Cr | 7.5 mcg |

| Vit B6 | 2 mg | Cu | 0.6 mg |

| Vit B8 | 150 mcg | Mg | 90 mg |

| Vit B9 | 200 mcg | Mn | 1.75 mg |

| Vit B12 | 1 mcg | Zn | 7.5 mg |

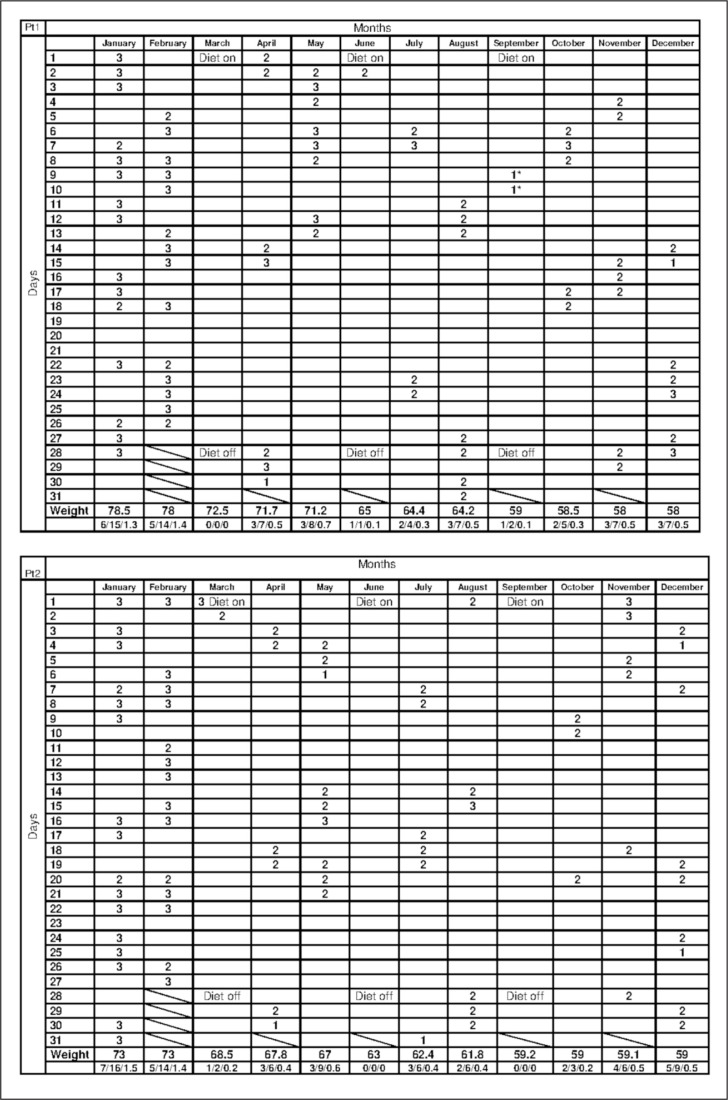

Both sisters, using headache diaries, kept a daily record of their migraine-induced disability. They reported about five to seven attacks/month (14–16 days/month) in the two months prior to starting the KD (Fig. 1). In both cases, the disappearance of migraine coincided with each ketogenic period (headache disappeared as from day 3 after the KD was started/resumed) and returned during the transitional diet periods, albeit with reduced frequency, duration and intensity. During the observation period, reported in figure 1, the patients did not take any preventive medication. Tests for celiac disease were negative, thereby excluding a role of dietary gluten avoidance.

Figure 1.

Diary chart.

The columns show the months, the rows the days. Patients recorded their degree of migraine disability daily on a 3-point scale: 1 = mild; 2 = moderate; 3 = severe.

In the “Weight” row, the patient’s weight, in kg, on the last day of the month is reported. The last row in each chart gives, month by month, the monthly migraine frequency (number of attacks), number of days with migraine in the month, and a monthly mean migraine disability index (sum of day-to-day disability divided the number of days with migraine in the month).

Neither patient experienced migraine attacks during the ketogenic diet, except for a non-migraine headache during menses and influenza in Patient 1 (*). The number of attacks, days with migraine, and the disability index all diminished during and after the ketogenic diet.

Discussion

We have described the case of a pair of twins who obtained a transient improvement of their migraine during a KD that was cyclically repeated as part of a weight loss dietary program. A previous report described a patient with MOH in whom a weight-loss KD surprisingly led to disappearance of the headache (Strahlman, 2006), but the real efficacy of ketogenesis on migraine is still under scrutiny (Maggioni et al., 2011). In fact, available data on the effects of ketogenesis in migraine patients are discordant: although a good response to KD is often described in anecdotal reports, this finding is not confirmed by all authors (Maggioni et al., 2011). In particular, in a pilot study performed on adolescents with chronic daily headache (CDH) no protective effect of KD was observed (Kossoff et al., 2010). However, this study was affected by several limitations: the normal-weight adolescents did not comply well with the diet; the fat-rich KD exposes patients to gastrointestinal problems that can reduce their compliance; the patients diagnosed with CDH could have included not only chronic migraineurs but also patients with other comorbidities (other types of headache and/or psychological problems).

It has recently been proposed that weight loss could, in itself, improve migraine in obese women (Bond et al., 2013), however, this is not the case of the twin sisters reported here. Indeed, the fact that migraine improvement coincided with ketogenesis and recurred out of KD (Fig. 1) led us to consider this beneficial effect a consequence of the ketogenesis.

Although several other factors (discontinuing analgesics, avoiding trigger foods and taking nutraceuticals) might have concurred to generate the unexpected outcome observed in these sisters, our experience corroborates and extends the observation that KD improves migraine, prompting several considerations. First, as already indicated (Fig. 1), the migraine improved before the final weight loss, thus this improvement was not a consequence of the latter; on the contrary, the cyclic withdrawal of the KD was associated with recurrence of migraine, despite the ongoing weight loss. Second, nutraceuticals – magnesium, coenzyme Q10, riboflavin, alpha lipoic acid (Sun-Edelstein and Mauskop, 2009) – presumably did not play a role in the migraine improvement, since they need to be assumed at higher concentrations and for a longer time in order to induce therapeutic effects. Third, migraine trigger compounds – phenylethylamine, tyramine, aspartame, monosodium glutamate, nitrates, nitrites, caffeine (Sun-Edelstein and Mauskop, 2009) – were not avoided during the KD. Hence, we attribute the improvement observed in these patients to ketogenesis, the sole event found to be time-locked to the disappearance (and recurrence) of their migraine attacks (Fig. 1); the improvement may be linked to modulation of cortical excitability (Wheless, 2008), dampening of inflammation and neuroinflammatory phenomena (Cullingford, 2004), and inhibition of oxidative stress (leading to reduced free radical formation) in neurons (Maalouf et al., 2007) and of the cortical spreading depression phenomenon (de Almeida Rabello Oliveira et al., 2008). Moreover, ketones are known to improve brain mitochondrial metabolism by enhancing mitochondrial genetic expression (Bough et al., 2006). Interestingly, mitochondrial genetics have already been related to the efficacy of riboflavin, a mitochondrial enhancer, in migraine prophylaxis (Di Lorenzo et al., 2009): a similar effect might be supposed to explain the improvement observed in migraineurs following a KD.

Our report provides Class IV evidence (i.e. a clinical opinion) since our hypothesis that weight-loss KD results in migraine improvement is based only on retrospective observation of a couple of cases. However, in view of the cases here reported, we have designed a more extensive prospective observational study in a population of overweight patients recruited at a dietician’s clinic. Preliminary results of this study in 108 migraineurs (52 treated with KD and 56 with a low-calorie diet), presented to the Italian Society for the Study of Headaches (SISC) (abstract only), seem to confirm that ketogenesis and not weight loss improves migraine: there was a very high responder rate (about 90%) during a one-month KD, while two months after the four-week period of ketogenesis the KD group did not differ from the standard diet group in terms of headache reduction. 0

Our observation, if confirmed by further, more extensive studies, may be an indication that overweight patients with high-frequency migraine can benefit from KD in repeated cycles: since most prophylactic treatments for migraine can potentially induce weight gain, the information we report could be very helpful for physicians caring for migraine patients.

References

- Astrup A, Meinert Larsen T, Harper A. Atkins and other low-carbohydrate diets: hoax or an effective tool for weight loss? Lancet. 2004;364:897–899. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16986-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond DS, O’Leary KC, Thomas JG, et al. Can weight loss improve migraine headaches in obese women? Rationale and design of the Women’s Health and Migraine (WHAM) randomized controlled trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;35:133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bough KJ, Wetherington J, Hassel B, et al. Mitochondrial biogenesis in the anticonvulsant mechanism of the ketogenic diet. Ann Neurol. 2006;60:223–235. doi: 10.1002/ana.20899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullingford TE. The ketogenic diet; fatty acids, fatty acid-activated receptors and neurological disorders. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2004;70:253–264. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Almeida Rabello Oliveira M, da Rocha Ataíde T, de Oliveira SL, et al. Effects of short-term and long-term treatment with medium- and long-chain triglycerides ketogenic diet on cortical spreading depression in young rats. Neurosci Lett. 2008;434:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lorenzo C, Pierelli F, Coppola G, et al. Mitochondrial DNA haplogroups influence the therapeutic response to riboflavin in migraineurs. Neurology. 2009;72:1588–1594. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a41269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kossoff EH, Huffman J, Turner Z, Gladstein J. Use of the modified Atkins diet for adolescents with chronic daily headache. Cephalalgia. 2010;30:1014–1016. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2009.02016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggioni F, Margoni M, Zanchin G. Ketogenic diet in migraine treatment: a brief but ancient history. Cephalalgia. 2011;31:1150–1151. doi: 10.1177/0333102411412089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maalouf M, Sullivan PG, Davis L, Kim DY, Rho JM. Ketones inhibit mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species production following glutamate excitotoxicity by increasing NADH oxidation. Neuroscience. 2007;145:256–264. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.11.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olesen J, Bousser MG, Diener HC, et al. New appendix criteria open for a broader concept of chronic migraine. Cephalalgia. 2006;26:742–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strahlman RS. Can ketosis help migraine sufferers? A case report. Headache. 2006;46:182. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00321_5.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun-Edelstein C, Mauskop A. Foods and supplements in the management of migraine headaches. Clin J Pain. 2009;25:446–452. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31819a6f65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheless JW. History of the ketogenic diet. Epilepsia. 2008;49(Suppl 8):3–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]