Abstract

Ethnographic research among people who inject drugs (PWID) involves complex ethical issues. While ethical review frameworks have been critiqued by social scientists, there is a lack of social science research examining institutional ethical review processes, particularly in relation to ethnographic work. This case study describes the institutional ethical review of an ethnographic research project using observational fieldwork and in-depth interviews to examine injection drug use. The review process and the salient concerns of the review committee are recounted, and the investigators’ responses to the committee’s concerns and requests are described to illustrate how key issues were resolved. The review committee expressed concerns regarding researcher safety when conducting fieldwork and the investigators were asked to liaise with the police regarding the proposed research. An ongoing dialogue with the institutional review committee regarding researcher safety and autonomy from police involvement, as well as formal consultation with a local drug user group and solicitation of opinions from external experts, helped to resolve these issues. This case study suggests that ethical review processes can be particularly challenging for ethnographic projects focused on illegal behaviours, and that while some challenges could be mediated by modifying existing ethical review procedures, there is a need for legislation that provides legal protection of research data and participant confidentiality.

Keywords: Canada, research ethics; ethnographic research; injection drug use; IDUs; case study

INTRODUCTION

Over the past 40 years, ethnographic research on drug use has helped advance scientific understandings of drug use (Moore, 2005), and identify shortcomings of public health responses targeting injection drug use, including needle exchange programs and overdose prevention campaigns (Bourgois, 1998; Moore, 2004). This body of drug use research is distinguished from other modes of inquiry by its methodology, which relies upon direct interaction with drug users, largely within the natural settings of “drug scenes” (Agar, 1997; Moore, 2005). Ethnographic researchers conventionally immerse themselves in the everyday activities of the group being studied in order to describe the social contexts relevant to the topics under consideration (Hammersley & Atkinson, 2006), this is termed “participant-observation”, and is considered to be a fundamental component of ethnographic inquiry.

Conducting ethnographic research with drug users often involves complex ethical issues (Bourgois, 1998; Maher, 2000), and numerous legal issues related to the conduct of ethnographic work among individuals engaged in illegal activities have been examined in the literature (Carey, 1972; Librett & Perrone, 2010; Weppner, 1973). Being present within drug scenes may lead ethnographers to have interactions with the police, face the possibility of arrest, or encounter threats to their own safety in the field (Librett & Perrone, 2010; Williams et al., 1992). Taken collectively, “being there” in drug scenes may represent a significant legal risk for ethnographers conducting research involving drug users (Carey, 1972).

The ability to conduct ethnographic fieldwork with drug users is predicated upon the understanding that the researcher will protect the anonymity of participants and the confidentiality of information obtained (Fitzgerald & Hamilton, 1997; Israel, 2004). However, the ability of researchers to maintain the confidentiality of sensitive information regarding drug use and other illegal acts is often limited by regulatory frameworks governing research ethics. These frameworks typically compel researchers to break confidentiality to report child abuse or to warn a third party of imminent harm, but researchers may also be compelled to breach confidentiality if police were to subpoena their fieldnotes or project data (Israel, 2004; Wiggins & McKenna, 1996). The presence of an ethnographer may expose research participants to legal risks if sensitive information regarding criminal acts were to be disclosed.

Ethnographic research and institutional ethics review

Ethnographic methods seek to investigate social processes and activities in situ. In most ethnographic research, the risks to participants are largely similar to those arising from their “everyday activities” (Canadian Institutes of Health Research, 2009; American Anthropological Association, 2004). However, institutional ethics review boards may have difficulty conceptualizing the risks related to ethnographic projects, partially due to the predominance of the biomedical research model within review frameworks (Bosk & Devries, 2004; Buchanan et al., 2002; Fitch, 2005). While critiques of how ethical review boards assess non-biomedical research have been articulated (Atkinson, 2009; Librett & Perrone, 2010), there is a lack of social science research examining institutional ethical review processes (Anderson & DuBois, 2007). In particular, the review of actual ethnographic research projects has rarely been documented, although such an examination could illustrate key ethical issues and potential solutions to these issues (Bosk & DeVries, 2004).

However, additional ethical considerations exist in relation to ethnographic research focused on illegal activities due to the fact that such research may expose participants to risks that are fundamentally different than those encountered through everyday activities. The presence of a researcher as participants engage in illegal activities carries particular risks for research participants, which do not exist in relation to ethnographic work focused on communities that are not under surveillance by law enforcement. In these instances, if confidentiality of research data is not maintained the disclosure of sensitive information could be very damaging for participants, potentially incriminating them or exposing them to criminal prosecution related to engagement in illegal acts (Stiles & Petrila, 2011). These dynamics are of great concern from the perspective of ethics review committees, and therefore necessitate the examination of many complex ethical issues that are not common to all ethnographic research. Therefore, there is a need to better understand the nature of these risks, and potential strategies to manage them.

There have been calls for case studies to document the ethical review processes for ethnographic research (Buchanan et al., 2002; Bosk & DeVries, 2004), in order to address the lack of empirical information regarding the institutional management of ethnographic research. In addition, there is also a need to better understand institutional review processes in relation to ethnographic research with drug users and other individuals involved in illegal activities. Such accounts may serve to equip ethnographers with potential solutions that could be put forward to research ethics boards to help navigate common concerns regarding ethnographic projects focused on illegal activities, and help institutional review boards better manage such research. This report aims to provide an account of the institutional review process for an ethnographic research project focused on people who inject drugs (PWID), and document the key ethical issues that emerged through the review process, and describe how these were resolved.

METHODS

We utilize an intrinsic case study methodology (Stake, 1988) to describe the institutional ethics review process for our ethnographic research focused on the health harms related to injection drug use in Vancouver, Canada. The case study presents our experiences regarding the adjudication of a research protocol we developed as it underwent institutional review. The authors of this manuscript are referred to as “the investigators” within the case study. We reviewed all written documentation regarding the application and correspondence between the review board and the investigators to identify the most significant concerns related to the proposal. We summarize the review process, requests made by the review board, and our responses, in order to illustrate how salient concerns were navigated. In addition, we present expert opinions obtained through the review process to explore how the most significant issues raised by the review board were perceived by experts external to the institution, and to describe how key issues were eventually resolved. In order to minimize bias in the case study reporting on our protocol and experiences, we have attempted to recount events and occurrences by relying on the record of official communications when reporting the case.

CASE STUDY: THE INSTITUTIONAL REVIEW PROCESS

BACKGROUND

In Canada, the Tri-Council Policy Statement (TCPS) provides the framework for all research ethics reviews, and outlines the responsibilities of institutional review boards, termed review ethics boards (REBs) (Canadian Institutes of Health Research, 2009). Unlike the United States, in Canada statutory mechanisms or legislation designed to protect the confidentiality of sensitive study data (e.g., Certificates of Confidentiality) do not exist, which means that individual REBs must manage these concerns on a case-by-case basis. While Canadian courts have protected the confidentiality of research data in noteworthy instances (Stiles & Petrila, 2011), these decisions have been based upon the specifics of the particular case rather than statutory or legislative protection of research (Palys & Lowman, 2000).

THE APPLICATION AND PROPOSED APPROACHES TO CONSENT

The application did not seek approval under the minimal risk category, due to the focus on marginalized drug users. The objectives of the research focused on blood-borne virus transmission, HIV prevention, and HIV treatment among PWID in Vancouver. Research activities included ethnographic fieldwork with an emphasis on observational activities in public injection settings and the local supervised injection facility (SIF), as well as in-depth interviews with PWID. The research sought to increase understanding of the influence of drug use settings on drug-related harm among PWID in Vancouver, in order to inform policy responses and public health interventions. Qualitative interviews, involving one-to-one conversations in a private setting within a storefront research office, would be audio-recorded, then subsequently transcribed and analysed. Written informed consent would be obtained for office-based interviews and participants would receive $20 CDN honoraria.

Observational activities involved visiting settings where PWID consume drugs, including public injection settings (i.e., streets, alleys, parks) and the SIF. During observational work the research would be explained to potential participants using a verbal script of introduction, and oral informed consent would be obtained. Fieldnotes detailing observations and conversations would be generated subsequently, and these notes would employ arbitrary code names and description of demographic characteristics (age, ethnicity, and gender) in reference to participants encountered during observational work. These methods sought to protect the anonymity of individuals participating in observational research, by rendering them unidentifiable. No monetary compensation would be offered to individuals providing oral consent to be observed and participate in unstructured interviews occurring within field settings.

INITIAL REB RESPONSE: DEFERRAL OF DECISION

When the application was subjected to full Board review, the REB deferred making a decision on the application, and raised three main concerns related to the proposal regarding informed consent, researcher safety, and the researcher’s duty to report criminal activities. Regarding procedures for gaining informed consent, the REB noted that during observational work research participants might be intoxicated and “thus not competent to consent”. In relation to researcher safety, the REB stated that the work entailed engagement with “a potentially vulnerable and/or dangerous group of people”, and therefore requested that the investigators consult with the local police and provide their assessment of this issue to the REB. In addition, the REB requested that the researchers consult a local drug user group, the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users (VANDU) regarding the conduct of the research, and forward VANDU’s assessment of the project to the REB. Regarding the duty to report criminal activities, the REB requested that the investigators obtain the perspective of local police regarding researchers’ witnessing of crimes during the conduct of this research. The investigators were further asked to provide information regarding what action would be taken if researchers were to witness criminal activities including, specifically, property crimes and prostitution.

NEGOTIATING CONSENT, SAFETY, AND DUTY TO REPORT PROTOCOLS

Following the REB’s decision, a revised application responding to the REB’s requests was submitted for consideration. Regarding the issue of consent and intoxicated individuals, the research team expressed a commitment to not invite individuals who were too intoxicated to provide informed consent, highlighting that study staff possessed extensive experience conducting research among drug users in the local context. The investigators challenged the request to obtain the opinion of the police regarding researcher safety, arguing that observational research is more similar to health outreach work than policing. Further, the investigative team had conducted REB-approved outreach activities within their wider research program for years without incident. The investigators explained that research staff received training in conflict de-escalation and employed additional measures designed to reduce the potential for harm when conducting observational work in drug scenes.

Through consultation with the leadership of VANDU, the investigators developed revised protocols for the early phases of the research. An appointed group of VANDU outreach workers, trained to undertake outreach activities in the DTES, would be consulted each time a new set of observational activities was to be initiated, and at least two of the VANDU outreach workers would accompany the project ethnographer during the initial phases of observational work, to facilitate researcher and participant safety.

On the matter of reporting criminal activity, the investigators explained that while the duty to report was recognized, under Canadian law researchers are not obligated to report crimes such as illicit drug use, drug dealing, theft, or prostitution. Regarding the request to liaise with the police, the investigators emphasized the need for the research to remain independent from police, explaining that the perception of police affiliation could negatively impact the study. Perceived police affiliation could reduce willingness to participate among potential participants and prompt concerns regarding the confidentiality of study data and potential disclosure of sensitive information.

REB RESPONSE TO REVISED APPLICATION: APPROVAL WITHHELD

Upon REB review of the revised application, ethical approval was withheld until the following recommendations were responded to:

The board does not expect substantial involvement of the police in this research, but requests a response to the following recommendations:

The researchers must notify the police that the research is taking place.

The researchers must provide the police with the name of the ethnographer, so as to reduce potential harm to him.

The investigators were not supportive of the REB’s request to inform the police regarding the research and the identity of the project ethnographer, due to concerns regarding potential harm to participants and negative impact upon the study resulting from the perception of police involvement. The investigators chose to consult with external experts regarding the REB’s recommendations and to obtain expert opinions prior to responding to the REB’s recommendations.

EXPERT OPINIONS REGARDING REB CONCERNS

To solicit expert opinions, the investigators contacted three individuals who had relevant expertise regarding institutional ethics review and human subjects research involving marginalized populations. These individuals were provided with the correspondence outlining the REB’s requests, and they agreed to write letters to the REB outlining their opinions. The expert opinions were provided by a public health researcher working with disadvantaged populations who had previously served on a REB (Expert #1), a human rights scholar and epidemiologist with experience conducting research among drug users (Expert #2), and an ethicist specializing in health and medical ethics (Expert #3).

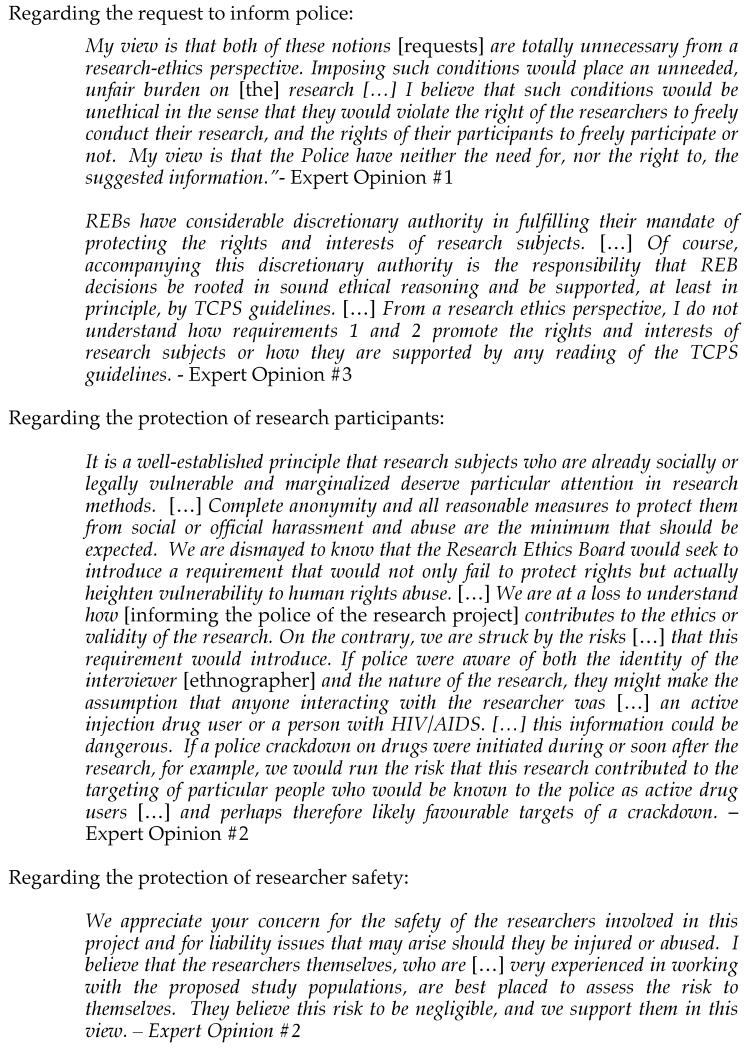

While the experts commended the REB for the rigor demonstrated in their review of the application, there was unanimous concern that the proposed measures would not improve the management of relevant ethical issues. Expert #1 asserted that the request to notify the police represented a barrier to the free conduct of research, and that it would be unethical to require the investigators to inform the police. Similarly, Expert #3 noted that there was no ethical principle supporting the REB’s requests, and that the TCPS does not provide sufficient rationale to impose the REB’s requirements to inform the police regarding the research. While the request to inform the police regarding the ethnographer’s identity was based upon the assumption that this would ensure researcher safety, Expert #2 asserted that the investigators were best positioned to assess the risks involved, based on their previous experiences working with the drug users in the DTES neighbourhood. Expert #2 argued that the principles of research ethics would support measures to ensure complete anonymity, and that the requirement to inform the police would potentially undermine efforts to protect the anonymity of research participants. Further, Expert #2 viewed the request to inform the police regarding the ethnographer’s identity as misguided, as it may in fact heighten vulnerability and the potential for harm among research participants if police were aware that individuals interacting with research staff were drug users. The text of the expert opinions appears in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Expert Opinions regarding REB Requests.

Overall, the expert opinions asserted that the requests were unnecessary, burdened the researchers, and could potentially compromise anonymity or increase the risk of harm to participants. The REB was provided with the expert opinions and investigators’ response to the REB’s recommendations, which articulated the investigators’ opposition to identifying the project ethnographer to police and the requirement to officially notify the police about the research.

APPROVAL & SUBSEQUENT CONDUCT OF THE RESEARCH

The REB conferred ethical approval for this project following consideration of the opinions of external experts and the investigators’ response. During the subsequent conduct of the research, the personal safety of researchers was not threatened within public drug using settings or the local SIF. Obtaining consent from drug users to conduct observational research was not an impediment to the study. However, many participants raised questions regarding the study’s relationship with the police during the process of obtaining consent for both interviews and observational activities. Research participants were concerned regarding the potential disclosure of sensitive information to police, and sometimes required assurance that the research was in no way affiliated with the police, and that the police would not be able to access project data. This suggests that if the investigators had complied with the requests to liaise with police in relation to the study, police involvement may have posed a significant barrier to recruitment.

DISCUSSION

This case study contributes to the literature describing the ethical regulation of human subjects research, as one of few accounts documenting the institutional review of a project and identifying issues raised during the review process. While the case study reports on the review process for our own protocol and our experiences related to this process, it provides significant insight into institutional ethical assessment of an ethnographic project involving study of illegal behaviours. Ethical and legal issues related to ethnographic fieldwork focused on illegal drug use complicated the institutional ethics review process. Within the review process, it necessary to address REB concerns related to consent procedures, researcher safety and requests to inform the police regarding the research. The key issues encountered were largely shaped by the illegal nature of the behaviours being studied, and these issues were resolved through a dialogue with the REB regarding researcher safety, autonomy from police involvement, and the protection of potential participants from harm. The review process also entailed formal consultation with a local drug user group and solicitation of opinions from external ethics experts which asserted that the requirement to inform the police had the potential to increase harm to research participants, and was not adequately supported by the relevant research ethics framework.

Researcher safety

The threats to personal safety related to fieldwork in drug scenes are recognized by ethnographers and other field-based researchers, who have identified strategies for navigating these hazards (Day et al., 2002; Williams et al., 1992). Our study protocol employed these conventional approaches to minimizing potential for harm to researchers, and a unique community consultation process involving a drug user group was utilized. It has been argued that consideration of researcher safety in field settings should be incorporated into ethical review processes (Librett & Perrone, 2010), although concerns have been expressed regarding the potential for institutional procedures assessing risks related to particular research sites, neighbourhoods, and types of participants to place additional burdens on ethnographers and other field-based researchers (Atkinson, 2009).

While assessment of researcher safety is not a formal REB responsibility under the TCPS, an REB may raise concerns regarding researcher safety (Canadian Institutes of Health Research, 2009). University lawyers are increasingly performing formal risk assessments as part of ethics review when researcher safety is a concern (Malone et al., 2006), although Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) committees have taken responsibility for these decisions at some institutions (University of New South Wales, 2010). Concerns regarding researcher safety have featured in cases involving research focused on illegal activities where REBs have withheld ethical approval (Malone et al., 2006), and it has been argued that the increasing focus on institutional risk and liability during ethical review illustrates an emerging tendency towards bureaucratic self-protection and risk aversion on the part of REBs (Burris & Davis, 2009). While minimizing risks to field-based researchers is essential, it would be counterproductive if protocols designed to mediate hazards to researcher safety functioned to impede the institutional approval of research or increase the potential for research participants to experience harm.

Relationships between research and law enforcement

REBs often have concerns related to projects that study illegal activities (Malone et al. 2006), particularly those focused on illicit drug use (Fitzgerald & Hamilton, 1997; Librett & Perrone, 2010). Law enforcement agencies constitute part of the research context for ethnographic studies of drug use (Page, 2005), and police actions may impact both study staff and drug using participants. Ethnographers have predominantly adopted a position of disengagement by remaining independent from police organizations (Maher, 2000; Fitzgerald & Hamilton, 1997), and although some ethnographic projects have developed formal arrangements with relevant law enforcement agencies, published accounts indicate that informing police regarding research does not necessarily protect study staff or participants (Burris & Davis, 2009; Page, 2005). Concerns regarding the relationship between researchers and the police may present an important barrier to recruitment for ethnographic projects involving drug users (Higgs, Moore, & Aitken, 2006), and police endorsements of research may be misinterpreted or viewed negatively by potential participants (Page, 2005). REBs should recognize that police knowledge of a project can seriously affect participants engaged in illegal activities, and may exacerbate the potential for harm, including arrest and incarceration.

Limits of confidentiality and legal considerations

Legal and regulatory constraints placed on researchers’ efforts to protect the confidentiality of study data have great significance for ethnographic studies of illegal behaviours (Fitzgerald & Hamilton, 1997; Israel, 2004), and the potential for harm to participants. Ethically approved projects studying illegal activities may face institutional and legal pressures to breach confidentiality (Israel, 2004; Fitzgerald & Hamilton, 1997; Stiles & Perrone, 2010). While federally funded research conducted in the United States may benefit from Certificates of Confidentiality that legally support researchers’ efforts to protect confidentiality (Anderson & DuBois, 2007), in many settings there is no legal basis for absolute confidentiality due to the lack of a privileged relationship between researchers and research participants (Israel, 2004; Palys & Lowman, 2000). Legal limitations on confidentiality have serious implications for social science research generally and ethnographic research focused on illegal behaviours in particular (Fitzgerald & Hamilton, 1997; Stiles & Petrila, 2011), as potential violations of confidentiality or the disclosure of sensitive information represent one of the greatest risks for harm in relation to such research (Canadian Institutes of Health Research, 2009). If research data is protected by a privileged relationship or legislation, this benefits ethnographic research by supporting researchers efforts to provide the greatest degree of confidentiality possible and reducing risks to participants stemming from disclosure (Stiles & Petrila, 2011), and is particularly important in relation to ethnographic research focused on illegal activities. Legislation protecting the confidentiality of research data may also enhance institutional review processes by permitting REBs to support researchers’ efforts to fully protect confidentiality.

However, court proceedings in the United States which have tested the strength of Certificates of Confidentiality indicate that even federal laws supporting protection of research data may be inadequate to provide absolute confidentiality to research participants (Beskow, Dame, & Costello, 2008; Wiggins & McKenna, 1996), and that efforts to protect research data may result in serious costs to researchers. In light of these dynamics, experts have recommended using additional measures to protect participant identities in recognition that legal protection may not prevent disclosure of sensitive information, and recommend de-identifying research records to the greatest extent possible and anticipating the possibility of demands for disclosure (Stiles& Petrila, 2011).

While ethics frameworks encourage researchers and REBs to consider limits on confidentiality and minimise the potential for harm to participants, REBs and researchers are often limited in their ability to address these hazards due to the lack of legal protection for research data. In fact, the mission ‘creep’ and risk aversion which often characterize institutional ethics oversight has been noted to create potential for breaches of confidentiality or erosion of the anonymity of research participants, particularly in relation to research focused on illegal acts or the police (Librett & Perrone, 2010), by compromising researcher efforts to ensure confidentiality.

Recommendations for enhancing ethical review of ethnographic research

Due to the limitations of existing ethical review processes for adjudicating social science research (Anderson & DuBois, 2007; Bosk & DeVries, 2004), there is a need for modifications to enhance the institutional review of qualitative and ethnographic research. Commentators have consistently recommended improving communication between REBs and researchers who employ ethnographic methods (Fitch, 2005; Librett & Perrone, 2010), articulating remedies to address the lack of fit between existing review frameworks and the character of social science research. REBs adjudicating qualitative and ethnographic research should possess appropriate disciplinary expertise to properly assess proposals, and should include adequate numbers of social scientists familiar with these methods (Fitch, 2005; Librett & Perrone, 2010). Similarly, application processes and forms that are designed to specifically accommodate qualitative and ethnographic proposals appear to be effective in improving communication between researchers and REBs (Fitch, 2005). It has also been suggested that increasing researcher participation in REB discussions and deliberations could foster openness and transparency in the review process, and help to minimize researchers’ frustrations with REB decisions (Gillam et al., 2009).

Research focused on vulnerable populations (such as drug users) is subjected to intense scrutiny during ethical review (Anderson & DuBois, 2007; Gillam et al., 2009), but board members often possess inadequate understandings of the realities of drug users’ lives (Bell & Salmon, 2011), which may result in overly protectionist decisions impeding ethically sound or potentially beneficial research (Burris & Davis, 2009; Librett & Perrone, 2010). Greater involvement of the affected community of drug users in ethical review processes may help to correct these issues (Bell & Salmon, 2011; Striley, 2011). To meaningfully involve representatives of the affected community of drug users in the review process (Fry, Treloar, & Maher, 2005; Strauss et al., 2001), local drug user organizations could be involved through an advisory board mechanism or as an independent review body (Australian Injecting and Illicit Drug Users League, 2010).

People who use drugs should be able to participate in research to the same extent as other social groups and have the right to benefit from research. Challenges stemming from risk aversion inherent within current review processes may impede relevant and innovative research focused on drug use or other illegal behaviours. REBs and researchers have a responsibility to balance the need to protect vulnerable research participants from harm, while at the same time respecting and supporting their right to participate in, and benefit from, research.

CONCLUSION

The process of institutional ethical review can be challenging for ethnographic research proposals, and is especially difficult when projects focus on illegal behaviours, including drug use. While modifications to existing ethical review procedures may benefit the management of ethical issues related to ethnographic research focused on illegal behaviours, in many settings there is a need for legislation that provides legal protection of research data.

Research Highlights.

Institutional ethical review can be challenging for ethnographic studies

Ethnographic studies of illegal activities pose particular risks

Modifying existing review procedures may improve the adjudication of such research

Legal protection of research data could address key risks related to such research

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Agar M. Ethnography: an overview. Substance Use and Misuse. 1997;32:1155–1173. doi: 10.3109/10826089709035470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Anthropological Association [Accessed October 15, 2011.];American Anthropological Association Statement on Ethnography and Institutional Review Boards. 2004 http://www.aaanet.org/stmts/irb.htm.

- Anderson EE, DuBois JM. The need for evidence-based research ethics: a review of the substance abuse literature. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2007;86(2-3):95–105. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson P. Ethics and Ethnography. 21st Century Society. 2009;4(1):17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Injecting and Illicit Drug Users League Australian Injecting and Illicit Drug Users League Research and Policy Update. 2010;6:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Beskow L, Dame L, Costello E. Certificates of confidentiality and compelled disclosure of data. Science. 2008;322:1054–1055. doi: 10.1126/science.1164100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosk C, DeVries R. Bureaucracies of Mass Deception: Institutional review boards and the ethics of ethnographic research. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2004;595:249–263. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgois P. The Moral Economies of Homeless Heroin Addicts: Confronting Ethnography, HIV Risk and Everyday Violence in San Francisco Shooting Encampments. Substance Use and Misuse. 1998;33:2323–2351. doi: 10.3109/10826089809056260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan D, Khoshnood K, Stopka T, Shaw S, Santelices C, Singer M. Ethical Dilemmas Created by the Criminalization of Status Behaviors: Case Examples from Ethnographic Field Research with Injection Drug Users. Health Education & Behavior. 2002;29(1):30–42. doi: 10.1177/109019810202900105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burris S, Davis C. Assessing social risks prior to commencement of a clinical trial: Due diligence or ethical inflation? The American Journal of Bioethics. 2009;9(11):48–54. doi: 10.1080/15265160903197507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell K, Salmon A. What women who use drugs have to say about ethical research: findings of an exploratory qualitative study. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics. 2011;6(4):84–98. doi: 10.1525/jer.2011.6.4.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans. 2009 http://www.pre.ethics.gc.ca/eng/policy-politique/initiatives/tcps2-eptc2/Default/

- Carey JT. Problems of access and risk in observing drug scenes. In: Douglas JD, editor. Research on Deviance. Random House; New York: 1972. pp. 71–92. [Google Scholar]

- Day C, Topp L, Swift W, Kaye S, Breen C, Kimber J, Ross J, Dolan K. Interviewer safety in the drug and alcohol field: a safety protocol and training manual for staff of the National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre. 2002 NDARC Technical Report No. 138. [Google Scholar]

- Fitch KL. Difficult Interactions between IRB’s and Investigators: Applications and Solutions. Journal of Applied Communication Research. 2005;33(3):269–76. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald J, Hamilton M. Confidentiality, disseminated regulation and ethico-legal liabilities in research with hidden populations of illicit drug users. Addiction. 1997;92(9):1099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillam L, Guillemin M, Bolitho A, Rosenthal D. Human research ethics in practice: deliberative strategies, processes and perceptions. Monash Bioethics Review. 2009;28(1):1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammersley M, Atkinson P. Ethnography: Principles in practice. Routledge; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Higgs P, Moore D, Aitken C. Engagement, reciprocity, and advocacy: ethical harm reduction practice in research with injecting drug users. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2006;25:419–423. doi: 10.1080/09595230600876606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel M. Strictly confidential? Integrity, and the disclosure of criminological and socio-legal research. British Journal of Criminology. 2004;44:715–40. [Google Scholar]

- Librett M, Perrone D. Apples and oranges: Ethnography and the IRB. Qualitative Research. 2010;10(6):729–747. [Google Scholar]

- Maher L. Sexed Work: Gender, Race, and Resistance in a Brooklyn Drug Market. Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Malone RE, Yerger VB, McGruder C, Froelicher E. “It’s like Tuskegee in reverse”: a case study of ethical tensions in institutional review board review of community-based participatory research. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(11):1914–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.082172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore D. Key moments in the ethnography of drug-related harm: Reality checks for policy makers? In: Stockwell TR, Gruenewald P, Toumbourou J, Loxley W, editors. Preventing Harmful Substance Use: The Evidence Base for Policy and Practice. John Wiley and Sons; Chichester: 2005. pp. 433–442. [Google Scholar]

- Moore D. Governing street-based injecting drug users: A critique of heroin overdose prevention in Australia. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;59(7):1547–1557. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page JB. International research and local authorities: Interplay between research and police agendas in the field of drug abuse and AIDS. Journal of Urban Health. 2005;82(3S4):iv16–iv 23. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palys T, Lowman J. Ethical and legal strategies for protecting confidential research information. Canadian Journal of Law and Society. 2000;15:39–80. [Google Scholar]

- Stake RE. Case study methods in educational research: Seeking sweet water. In: Jaeger RM, editor. Complementary methods for research in education. American Educational Research Association; Washington, DC: 1988. pp. 253–278. [Google Scholar]

- Stiles P, Petrila J. Research and confidentiality: Legal issues and risk management strategies. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law. 2011;17(3):333–356. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss RP, et al. The role of community advisory boards: involving communities in the informed consent process. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(12):1938–43. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.12.1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striley CW. A review of current ethical concerns and challenges in substance use disorder research. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2011;24(3):186–90. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328345926a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- University of New South Wales OHS Policy Statement. 2010 www.ohs.unsw.edu.au/ohs_policies/policies/statement_OHS_policy.pdf.

- Weppner RS. An anthropological view of the street addict’s world. Human Organization. 1973;32(2):111–121. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins E, McKenna J. Researchers’ reactions to compelled disclosure of scientific information. Law and Contemporary Problems. 1996;59(3):67–93. [Google Scholar]

- Williams T, Dunlap E, Johnson BD, Hamid A. Personal safety in dangerous places. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography. 1992;21(3):343–374. doi: 10.1177/089124192021003003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]