Abstract

Kinship systems which tend to be based on ecologies of subsistence also assign differential power, privilege and control to human connections that present pathways for manipulation of resource access and transfer. They can be used in this way to channel resource concentrations in women and hence their reproductive value. Thus, strategic female life course trade-offs and their timing are likely to be responsive to changing preferences for qualities in women as economic conditions change. Female life histories are studied in two ethnic groups with differing kinship systems in N.E. India where the competitive market economy is now being felt by most households. Patrilineal Bengali (599 women) practice patrilocal residence with village exogamy and matrilineal Khasi (656 women) follow matrilocal residence with village endogamy, both also normatively preferring three-generation extended households. These households have helpful senior women and significantly greater income. Age at first reproduction (AFR), achieved adult growth (height) and educational level (greater than 6 yrs or less) are examined in reproductive women, ages 16–50. In both groups, women residing normatively are older at AFR and taller than women residing non-normatively. More education is also associated with senior women. Thus, normative residence may place a woman in the best reproductive location, and those with higher reproductive and productive potential are often chosen as households face competitive market conditions. In both groups residing in favorable reproductive locations is associated with a faster pace of fertility among women, as well as lower offspring mortality among Khasi, to compensate for a later start.

INTRODUCTION

Life history trade-offs for human females are made in the context of local cultural ecologies that influence resource access, the most fundamental of which are kinship ecologies. Kinship systems provide opportunities for manipulation of resource access and transfer. They may, therefore, provide a framework for strategic utilization of female life course trade-offs and their timing in ways that concentrations of resources in women and hence their reproductive value become channeled. The selective effects of increased pre-reproductive parental investment in females could in this way be enhanced by placing them where resources and social support are greatest, given the particular kinship system. Longer pre-reproductive investment can lead to greater size and more skills development, both of value in producing high-quality children and, therefore, also likely to be in demand in brides in prime kinship-based locations.

Age at first reproduction represents a fundamental shift in the life course from investment in growth to investment in reproduction. Across species, longer, larger pre-reproductive investment is generally associated with greater body size, greater reproductive capacity and greater adult productivity (Charnov and Berrigan, 1993). Focusing on humans, Kaplan (1996) argues that skills acquisition (i.e., education) should be added as an investment and uses the term “embodied capital” for the resulting combination. He provides the theoretical logic for differential embodied capital investment. In effect, in any human population, parental investment in embodied capital responds to the varying potential for future adult productivity of the child and her associated potential for reproductive success, given ecological opportunities. Kinship ecologies offer variable opportunities in terms of reproductive settings. Strategic marital residential placement of women, with respect to resource access and helpers, in combination with assets they possess from pre-reproductive investment is likely to influence their reproductive capabilities. Women with greater embodied capital are likely to find the best reproductive settings as they will either be in demand or be able to exclude women with lesser embodied capital.

Evidence points to greater reproductive capacity in larger women (Sear et al., 2004; Martorell et al., 1981; Kirchengast et al., 1998; Witter et al., 1995) as well as associated greater production capacity (Malina et al., 2004). Larger body size is expected to take longer to achieve and delay reproductive readiness. Data from the Gambia (Sear et al. 2004) and South Korea (Kim et al., 1999) show greater height associated with later age at first reproduction and menarche. Little and Malina (2007), comparing poorly nourished Oaxaca children with well-nourished children from Philadelphia, find shorter height in Oaxacan children due to earlier long bone maturation. In earlier work, both Garn et al. (1986) and Wellens et al. (1992) found women who experience late menarche to be taller than those experiencing early menarche.

As the modern market economy penetrates all parts of the world and creates greater potential opportunity, competition with respect to productivity is likely to increase investment in education (Kaplan, 1996), with associated delays in reproduction (Kaplan et al., 2002). Later age at marriage and first reproduction have occurred where parental resources could sustain the educational investments leading to beneficial pay-offs, at least in economic terms (Kaplan et al., 2002). Investment in girls’ education can prove beneficial in their future roles as mothers producing high quality offspring or as participants in the labor market or businesses. As in other countries undergoing economic development, age at first marriage has risen in India (Ravichandran, 2002; Shenk, 2008). Thus educational investment is likely to play a role in delaying age at first reproduction. Increased associated parental investment in child health, also leading to greater height, is expected to occur concurrently as insurance against loss (via child mortality) of educational investment (Kaplan et al., 2000). Economic development also tends to reduce extrinsic child mortality risks so reproductive delays are potentially less costly (Quinlan, 2007).

Delaying age at first reproduction has potentially high costs in terms of a woman’s reproductive success due to lost time (assuming she survives to reproduce). To overcome this deficit, fertility has to be faster paced1 and/or mortality of offspring lower (Hawkes et al., 1997). Both are possible if underwritten with greater resources, either in maternal embodied capital accumulated prior to age at first reproduction2 or in those accessed through advantageous post-marital social positions.

Age at first reproduction, achieved growth (adult height), and educational level are examined with respect to how they are patterned within differing kinship systems among women in two ethnic groups in N.E. India. Basic to their kinship systems are rules regarding normative village residence of the couple and household formation. The groups are patrilineal Bengali who practice patrilocal residence with village exogamy for women and matrilineal Khasi who follow matrilocal residence with village endogamy for women. Residence in extended households which include the senior generation is also normative in both for adult offspring and their spouses, although not all adult children can follow these normative patterns.

The ecological and economic base differs between the groups in that Bengali are plow agriculturalists whose primary productivity is in their paddy fields on the plains while the Khasi primarily practice swidden horticulture on mountain hillsides but also raise paddy on the valley floors. We know that both patriliny and matriliny have ecological correlates in plow agriculture and horticulture, respectively (Aberle, 1961; Goody, 1976). For Bengali and others who follow a patrilineal system, the logic of cooperative behavior among sons applies where subsistence ecologies depend on heavy labor and defense of inherited land by males. Cooperation among male kin is usually supported by marriage residence rules. Bengali have as an ideal the co-residence of brothers in joint households reflecting this adaptive behavioral complex, even though infrequently fully achieved. Khasi practice swidden horticulture and women usually work the land with light-weight tools. Land rights can fluctuate so cooperation among female kin in work effort may provide the main support for matriliny. Additional benefits of cooperative breeding among related females can also accrue (Leonetti et al., 2005). Generationally extended households usually include youngest daughters who inherit their mother’s house, but elder daughters also sometimes reside with their mothers (Leonetti et al., 2007a). Otherwise, residence close to a woman’s mother and her sisters is desirable and common. Both economies, however, are mixed between subsistence and cash. The large majority of households in both groups (81.5% of Khasi and 88.4% of Bengali), depends on some cash income from wages or businesses. Hence, the effects of an emerging market economy are being felt.

Social contexts for these kinship practices also differ for the two groups. Patrilineal Bengali practice arranged marriages. Divorce and remarriage are greatly discouraged by societal norms and young widowhood is viewed as extremely inauspicious. Women’s lives are also greatly restricted. Women must stay within their home or neighboring compounds and they engage solely in home-based economically productive work (e.g., winnowing, drying and milling of crops). They do not go to the markets where all selling and buying is done by men. In contrast, Khasi women own and inherit property including rights to land. Their marriages are by choice, with divorce and remarriage being common. Women are economically very active, working in their fields, doing wage labor, running businesses, and buying and selling in the local markets. Both groups are monogamous and fertility is high in both groups (Leonetti et al., 2005).

We ask here whether pre-reproductive investments in females are aligned with the marital locations stipulated by residential norms of these kinship systems, specifically village residence and household composition supported by the kinship ideologies. Do patterns of investment emerge that support the idea of manipulation of female embodied resources in response to the ecologies of the differing kinship systems? We also ask, if a fit occurs, whether it appears to be adaptive. Although the ultimate test of adaptiveness would be reproductive success, its measurement cross-sectionally over reproductive women of different ages as well as differing ages at first reproduction is not very reliable. Also many children are still very young. How to assess their importance in a reproductive success measure that counts only children who have survived to some certain age is problematic. We can, however, look for differences in contributors to reproductive success, i.e., pace of fertility and child loss to mortality to date of interview, in relation to kinship variables.

SAMPLES AND METHODS

The research protocol and procedures employed in this research were reviewed and approved by the University of Washington Human Subjects Review Committee.

The samples are community based, from 5 Khasi and 13 Bengali villages. After obtaining permission from village headmen, all women who had at least one live born child (Khasi, 1 to 15; Bengali, 1 to 11 children) were asked permission for an interview. The samples include 599 Bengali and 656 Khasi women, ages 16 to 50. Only one woman per household is represented. Very few households (less than 1%) had more than one eligible woman and in these cases a random choice of one of the women was made. All Bengali women are currently married. Due to cultural circumstances described above, divorced or widowed women would be rare and not available for interview. Of Khasi women, 24% have a history of divorce and 84% are currently married. Structured interviews conducted with Khasi and Bengali interpreters covered current household socioeconomic characteristics (household income), and women’s residential (whether residing in parental village or not) and reproductive histories (age at each birth, age of child at death if deceased). At the time of the interview we ascertained the living and residential status (deceased or alive/residing in the same household with the woman or elsewhere) of the senior generation woman (husband’s mother for Bengali and woman’s mother for Khasi, both denoted as Gm, for grandmother, in the tables and figures). Senior men were so few in number in both groups (due to their deaths, as age difference between marital partners was often large and mortality higher in the past in both groups, or due to divorce in some Khasi cases) that they cannot be included in the analysis.

Age at first reproduction is the exact age of the woman (e.g., 21.5 years) at the time of her first live birth. Height (measured in centimeters with a steel anthropometer) is used as the best indicator of pre-reproductive parental influence on body size, as weight is subject to socioeconomic conditions since marriage. Women’s completed educational levels are low in both groups so we use some education past primary grades (> 6 years) or primary grades or less as our measure (≤ 6 years).

A cumulative risk score for delayed age at first reproduction is computed with each factor (woman’s height above median, normative village residence, living in household with a senior woman, and education above the primary grades) assigned one point resulting in a total score of zero to four, defined here as categories of increased risk.

Pace of fertility is measured as the time between the first birth and the last recorded birth (plus nine months to account for time for the first pregnancy), divided by the number of live births to date of interview, providing a measure of average time devoted to the production of each child. With respect to child loss to mortality, women are divided into two categories 1) if they had any live born children who failed to survive up to five years or to date of interview or 2) if all their live born children were alive, or were alive until age 5 years, at date of interview.

Analysis

Cox regression providing a hazard ratio (HR) and confidence interval (CI) is used to test the difference in risk of first reproduction by age between the two ethnic groups. An HR greater than 1.0 indicates increased risk and below 1.0 decreased risk. If the CI range passes through 1.0 the HR is not significantly different than 1.0 and indicates no difference in risk by that variable. The Generalized Linear Model (GLM) tests for differences in woman’s age at first reproduction and in height between categories of kinship-defined village residence (endogamy or exogamy, i.e., in parental village, yes or no) and household composition (defined by living/residential status of the senior woman) and provides adjusted mean values compared using F tests. The GLM also tests for differences in woman’s age at first reproduction among categories of cumulative risk as define above. Binary logistic regression analysis is used to estimate the odds ratios (OR) of having more than primary education versus primary education or less, and of having at least one child who died under 5 years of age versus having all children alive or survive to age 5, given village residence and status of senior woman. Odds ratios are interpreted similarly to hazard ratios (see above). Pearson r and Spearman rho correlations are also used. P values are provided if significance is less than p < 0.1, given that patterns in the results are what we are looking for rather than single findings and we wish to note results that are marginally significant and may contribute to a pattern.

Data description

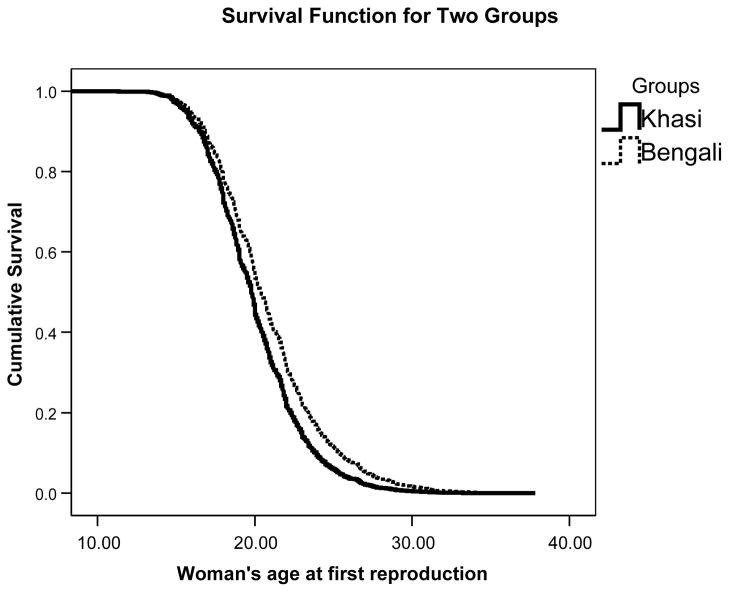

Bengali women are slightly, but significantly, younger than Khasi women and have significantly fewer children after adjustment for the woman’s age (Table 1). Bengali women experienced first reproduction at significantly older ages than Khasi women (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Khasi women are significantly taller than Bengali women. Bengali women significantly, however, are twice as likely to attend grades higher than primary level (Table 1). Bengali and Khasi have almost the same mean number of household members. Both are poor with low median total annual household cash, somewhat higher for Khasi as both men and women can have income.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the samples, for 599 Bengali women and 656 Khasi women, ages 16 to 50 years.

| Samples | Bengali | Khasi | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Woman’s age mean ± S.D. |

30.2±6.0 | 31.7±7.6 | 14.2 | <.001 |

| Woman’s age at first reproductionab mean ± S.E. |

20.8±0.1 | 20.2±0.1 | 11.4 | .001 |

| Children ever live borna mean ± S.E. |

3.6±0.1 | 4.0±0.1 | 3.1 | .001 |

| Woman’s heighta (cm) mean ± S.E. |

146.9±0.2 | 150.4±0.2 | 119.3 | <.001 |

| Woman’s primary educationa (>6 yrs) % |

27.9 | 15.2 | O.R .= 2.1 (C.I. 1.6, 2.7) | <.001 |

| Household size | 6.06 +− 2.19 | 6.12 +− 2.24 | 0.1 | ns |

| Household income median in US$c | 555.00 | 622.00 | - | - |

Adjusted for woman’s age.

Adjusted for woman’s age2

No statistic is applied as the number of earners is not comparable (see text).

Fig. 1.

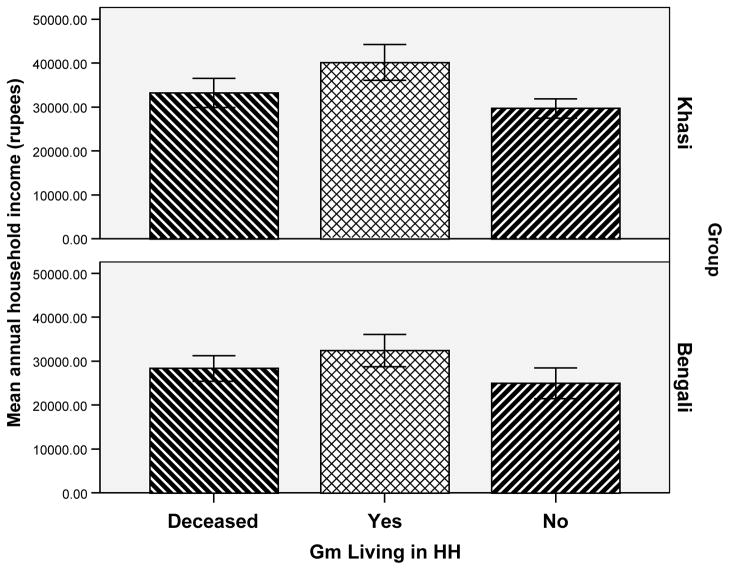

Mean annual household income (rupees) given the status of the grandmother, Gm: woman’s mother for Khasi (n= 161,142, 353 for bars; F = 13.2, p < .001) and her husband’s mother for Bengali (n = 290, 204, 105 for bars; F = 3.9, p = .02). Both adjusted for woman’s age.

RESULTS

In each group the women show a modest but significant positive correlation of age at first reproduction with height (Bengali, r = .12, p = .003; Khasi, r = .08, p = .044), and with education (Bengali, rho = .225, p < .001; Khasi, rho = .195, p < .001), indicative of greater and longer pre-reproductive investment. Height and education are also significantly correlated for Bengali (rho = .126, p = .002) but not for Khasi (rho = .019, ns).

In each group ~80% of women follow the group’s village of residence rule, but only 29% of Bengali and 20% of Khasi also live with a senior woman. Households with female senior generation members in both groups have significantly greater income than those without them (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Cumulative risk of first reproduction by age for Khasi women (n=656) compared to Bengali women (n=599): H.R. 1.35 (C.I., 1.2, 1.5), p < .001 (age adjusted).

For both, age at first reproduction and height reflect village residence, with age at first reproduction being later and height taller for those following the normative pattern (Tables 2 and 3), i.e., Bengali women are older at first reproduction (p = .016) and taller (p = .023) if married exogamously (not living in parental village), while Khasi women are older at first reproduction (p = .09) and taller (p < .001) if married endogamously (yes, living in parental village).

Table 2.

Woman’s age at first reproduction by residence.

| Bengali | Khasi | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Living in parental village | n | Meana | Std. Error | n | Meana | Std. Error |

|

| ||||||

| Yes | 119 | 20.06 | 0.35 | 543 | 20.26 | 0.14 |

| No | 480 | 20.99 | 0.17 | 113 | 19.69 | 0.31 |

|

| ||||||

| F = 5.84, p = .016 | F = 2.88, p = .090 | |||||

Adjusted for woman’s age

Table 3.

Woman’s height (cm) by residence.

| Bengali | Khasi | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Living in parental village | n | Meana | Std. Error | n | Meana | Std. Error |

|

| ||||||

| Yes | 119 | 145.75 | 0.54 | 543 | 151.27 | 0.22 |

| No | 480 | 147.13 | 0.27 | 113 | 146.37 | 0.49 |

|

| ||||||

| F = 5.22, p = .023 | F = 83.87, p < .001 | |||||

Adjusted for woman’s age

It is also evident that Bengali women living exogamously in extended households with their mothers-in-law (Gm) are older by about 2 years at first reproduction (Table 4, shaded value) and somewhat taller by over 2 cm (Table 5, shaded value) than women non-normatively residing in their parental villages and not in extended families (Tables 4 and 5, # signs). Among Khasi, women residing with their mothers (Gm) endogamously are older at first reproduction by about 1.3 years (Table 4, shaded value), and taller by over 5 cm (Table 5, shaded value) compared with women not residing endogamously and not living with their mothers (Tables 4 and 5, # signs). F-tests show that for Bengali women village location of residence is significant for both a woman’s age at first reproduction and height while the mother-in-law’s status (Gm) is significant only for age at first reproduction. For Khasi women, the mother’s status (Gm) is also significant only for age at first reproduction; but height is affected strongly and significantly only by village location of residence.

Table 4.

Woman’s age at first reproduction by the senior woman’s (Gm) status and residence.

| Bengali | Khasi | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Gm Status | Living in parental village | n | Meana | Std. Error | n | Meana | Std. Error |

|

| |||||||

| Deceased | Yes | 64 | #19.78 | 0.38 | 123 | 20.06 | 0.26 |

| No | 227 | 20.64 | 0.24 | 38 | #19.60 | 0.37 | |

| In household | Yes | 31 | 20.85 | 0.42 | 131 | 20.91 | 0.27 |

| No | 172 | 21.71 | 0.27 | 11 | 20.44 | 0.41 | |

| Elsewhere | Yes | 24 | #19.63 | 0.47 | 289 | 20.06 | 0.18 |

| No | 81 | 20.49 | 0.37 | 64 | #19.59 | 0.32 | |

|

| |||||||

| GLM | Gm F= 5.8, p = .003 Village F=4.9, p =.027 |

Gm F= 3.9, p = .020 Village F=1.9, ns |

|||||

Adjusted for woman’s age.

Table 5.

Woman’s height (cm) by the senior woman’s (Gm) status and residence.

| Bengali | Khasi | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Gm Status | Living in parental village | n | Meana | Std. Error | n | Meana | Std. Error |

|

| |||||||

| Deceased | Yes | 64 | #145.66 | 0.59 | 123 | 151.30 | 0.42 |

| No | 227 | 146.97 | 0.37 | 38 | #146.43 | 0.59 | |

| In household | Yes | 31 | 146.35 | 0.66 | 131 | 151.52 | 0.43 |

| No | 172 | 147.64 | 0.43 | 11 | 146.64 | 0.65 | |

| Elsewhere | Yes | 24 | #145.20 | 0.74 | 289 | 151.16 | 0.29 |

| No | 81 | 146.51 | 0.59 | 64 | #146.28 | 0.51 | |

|

| |||||||

| GLM | Gm F= 1.5, ns Village F=4.7, p =.031 |

Gm F= 0.3, ns Village F= 81.5, p < .001 |

|||||

Adjusted for woman’s age.

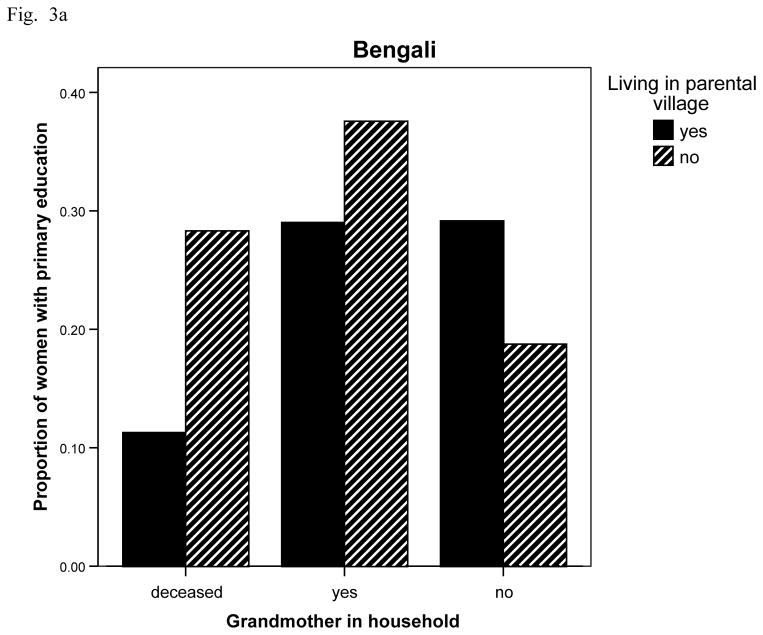

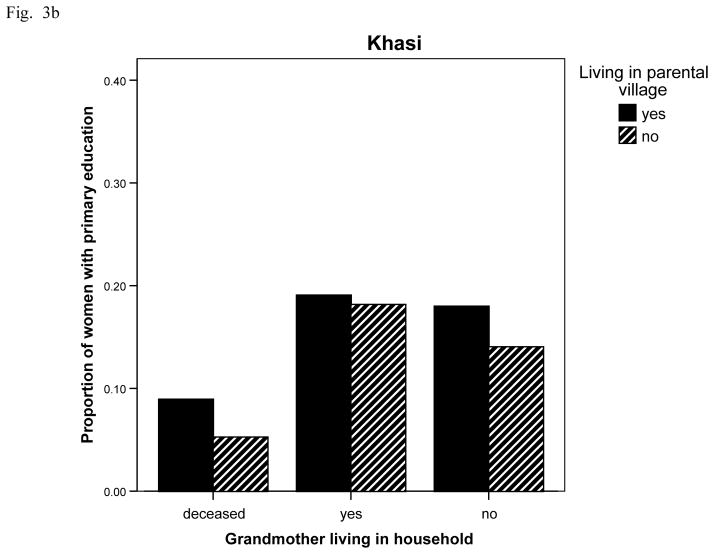

With respect to education (Fig. 3 ab), Bengali women are significantly less likely to have more than primary education if living non-normatively in their parents village (OR = 0.597, CI 0.362, 0.985, p = 043, age adjusted) instead of exogamously. They are also significantly more likely to have more than a primary education if living with their mother-in-law (OR = 1.956, CI 1.123, 3.405, p = .018, age adjusted) compared to where the mother-in-law lives elsewhere. Of those living exogamously with senior women 37.6% have more than a primary education compared to 27.9% overall (Fig. 3 a). Khasi women, however, only show less education if their mothers are deceased (OR = 0.485, CI 0.256, 0.915, p = .027) versus alive, adjusting for woman’s age and village of residence (Fig. 3 b).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3a Proportion of Bengali women with more than 6 years of school by village residence and grandmother (husband’s mother) living/residential status (n = 64, 227, 31, 172, 24, 81 for bars). Living in parental village (compared to not): O.R. = 0.62, C.I., 0.38, 1.03, p = .065; Yes in household (compared to no): O.R. = 1.91, C.I., 1.09, 3.33, p = .023; Deceased (compared to no): ns; age-adjusted.

Fig. 3b Proportion of Khasi women with more than 6 years of school by village residence and grandmother (woman’s mother) living/residential status (n = 123, 38, 131, 11, 289, 64 for bars). Living in parental village (compared to not): ns; Yes household (compared to no): ns; Deceased (compared to not): O.R. = 0.49, C.I., 0.26, 0.92, p = .027; age adjusted.

In a generalized linear model using the cumulative risk score for age at first reproduction as a categorical variable, there is a distinct gradient in age at first reproduction by score value for both ethnic groups (Table 6, p < .001 for both).

Table 6.

Age at first reproduction by cumulative risk scoreb.

| Score | Bengali | Khasi | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| n | Meana | Std. Error | n | Meana | Std. Error | |

|

| ||||||

| 0 | 47 | 19.39 | 0.54 | 72 | 19.01 | 0.38 |

| 1 | 169 | 19.81 | 0.28 | 186 | 20.06 | 0.23 |

| 2 | 203 | 20.67 | 0.26 | 281 | 20.14 | 0.19 |

| 3 | 144 | 22.03 | 0.31 | 100 | 20.94 | 0.31 |

| 4 | 36 | 23.38 | 0.61 | 17 | 22.48 | 0.76 |

|

| ||||||

| GLM | F = 12.89, p < .001 | F = 6.17, p <.001 | ||||

Adjusted for woman’s age.

Score includes one point for each of the following: woman’s height above median, normative village residence, living in household with a senior woman, and education above the primary grades.

We see that among Bengali women the pace of fertility is faster (i.e., shorter time on average devoted to each birth) for women marrying exogamously and living with their mother-in-law (Table 7, shaded value) than for the others, a benefit which may offset the cost of delayed age at first reproduction. For all other women, longer average times devoted to each birth are seen, especially for women whose mother-in-law is deceased and who are living non-normatively in their parent’s village. Bengali women also show no differences in fertility after adjustments for age and age at first reproduction (Table 8) indicating that the normatively marrying group is able to compete, given their faster pace of fertility, even though they have started childbearing later.

Table 7.

Pace of fertility by ethnic group, presented as mean time (yrs) between births from age of first reproduction m to last recorded reproduction, by the senior woman’s (Gm) status and residence.

| Bengali | Khasi | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Gm Status | Living in parental village | Mean | Std. Error | Mean | Std. Error |

|

| |||||

| Deceased | Yes | 2.13 | 0.08 | 1.97 | 0.06 |

| No | 1.91 | 0.05 | 2.01 | 0.09 | |

| In household | Yes | 1.79 | 0.09 | 1.72 | 0.07 |

| No | 1.57 | 0.06 | 1.76 | 0.10 | |

| Elsewhere | Yes | 2.01 | 0.10 | 1.78 | 0.04 |

| No | 1.79 | 0.08 | 1.81 | 0.08 | |

|

| |||||

| GLM: | Village, F = 7.53, p = .006 Gm, F =11.14, p = < .001 |

Village, F = 0.20, ns Gm, F = 4.78, p = .009 |

|||

Table 8.

Number of live born children adjusted for woman’s age and her age at first reproduction, for each ethnic group by status of senior woman (Gm) and whether living in parental village or not.

| Bengali | Khasi | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Gm Status | Living in parental village | Mean | Std. Error | Mean | Std. Error |

|

| |||||

| Deceased | Yes | 3.37 | 0.15 | 3.98 | 0.16 |

| No | 3.46 | 0.10 | 4.59 | 0.22 | |

| In household | Yes | 3.45 | 0.17 | 3.80 | 0.16 |

| No | 3.54 | 0.11 | 4.71 | 0.24 | |

| Elsewhere | Yes | 3.45 | 0.19 | 4.10 | 0.11 |

| No | 3.54 | 0.15 | 4.71 | 0.19 | |

|

| |||||

| GLM: | Village, F = 0.69, ns Gm, F = 0.25, ns. |

Village, F = 10.78, p = .001 Gm, F = 1.72, ns |

|||

For Khasi women, we see that those women residing endogamously with living mothers show the fastest pace of fertility (Table 7, shaded value), but it differs little from the other women whose mothers are alive. Only those with deceased mothers show a slower pace. However, those women living with their mothers in their parental village also have the lowest fertility, even with adjustment for age and age at first reproduction (Table 8, shaded value). Other Khasi women living in the parental village also show lower fertility and the village is the significant factor rather than the mother’s presence. The real advantage, however, for Khasi women of living with or near their mothers in their parental villages is the lower child mortality they experience (Table 9, shaded values). Bengali women do not appear to benefit in this way when living exogamously with their mother-in-law (Table 9, shaded value).

Table 9.

Per cent of women with one or more deceased children who died under age 5 years.

| Gm Status | Living in parental village | Bengali (%) | O.R. (C.I.)a | Khasi (%) | O.R. (C.I.)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Deceased | Yes | 19.0 | Ref. | 18.1 | Ref. |

| No | 16.0 | 0.70 (0.32, 1.51) | 23.3 | 1.03 (0.39, 2.74) | |

| In household | Yes | 10.0 | 0.36 (0.08, 1.59) | 9.5 | 0.35 (0.14, 0.90) |

| No | 18.2 | 0.85 (0.36, 1.99) | 28.7 | 2.02 (0.42, 9.80) | |

| Elsewhere | Yes | 11.8 | 0.55 (0.13, 2.40) | 10.4 | 0.49 (0 .25, 0.94)* |

| No | 22.2 | 1.114 (0.47, 2.78) | 16.8 | 0.67 (0.28, 1.60) | |

p < .05

Adjusted for woman’s age and number of live born children

DISCUSSION

Age at first reproduction, adult height and educational level each signal a life history shift. The first signals a shift of investment from self to reproduction. The second signals the end of investment in self via growth. The third focuses more emphasis on early life investment in greater skills acquisition. The three are unlikely to be tightly linked as investment in self, such as skills development, may occur after growth has ceased. All, however, respond to the way resources are socially distributed in humans and are likely to be subject to manipulation within kinship systems. We might, therefore, expect resource concentrations in individuals according to the kinship ideologies and rules of their ethnic group, with the assumption that kinship systems are frameworks that individuals use to bias the assortment and use of resources for productive and reproductive purposes. Thus, they appear to allow management of the generation, reinforcement, and exploitation of phenotypic correlations, in this case, in women.

The present analysis suggests that kinship lineage and marriage rules can be manipulated to organize the flow of female embodied resources with respect to distance (i.e., village exogamy or endogamy) in ways favorable to the lineage system involved (patrilineal or matrilineal) and the locus of resources in that lineage, i.e. the household location of senior members (in the present case, the woman’s mother-in-law or mother). The presence of the senior woman is associated with more household income3 and provides her helping hand to the reproductive woman (Leonetti et al. 2005). Thus, normative village residence with a senior woman is likely to place a woman in a good reproductive location. We find that later age of first reproduction, greater height, and more education tend to concentrate at this most preferred normative marital location. Individuals controlling these locations are powerful in determining, in ways favorable to themselves with respect to production and reproduction, which women get access to them—those with higher reproductive potential are often chosen. Women less favorably endowed may have to accept less resource rich reproductive settings. In fact, age at first reproduction shows a significant upward gradient in association with increases in our cumulative score based on favorable factors.

Note that not all younger women in the villages have yet reproduced for the first time. This means that a number of younger women were not eligible to be included in our sample which places some limits on our capacity to interpret the data. These women, however, will necessarily experience later ages at first reproduction than their already married same-age counterparts included in the sample. Thus, the trends visible in the data presented are likely to become stronger should inclusion of their reproductive histories be possible.

Life history research points to evolutionary trends toward later age at maturation as an evolved adaptive trait in our species compared to other primates and to earlier hominids because of advantages of larger size and greater reproductive and productive capacities (Charnov and Barrigan, 1993; Hawkes et al., 1998; Hill, 1993; Mace, 2000). Within our species, however, relatively earlier reproduction may be favored as it provides greater probability of reproduction and increases the reproductive span for more births. Given non-market or undeveloped economies, greater parental investment was likely to drive down age at first marriage and reproduction. In the past, the “European marriage pattern” with late average age at marriage and high rates of celibacy was associated with resource (usually land) constraints and requirement for monogamous, neolocal marriage practices in agrarian settings (Hajnal, 1982). Only the wealthy could marry at younger ages (Drake, 1969; Voland et al., 1991; Low, 2005; Low and Clarke, 1992). In other non-western settings, where polygyny often occurred, nutritional constraints probably played an important role and menarche was likely delayed for the poorest. Thus richer, earlier maturing, women could marry at younger ages. In both these cases women from wealthier families probably had higher reproductive value at earlier ages. Examples available in non-Western settings show younger age at marriage and body size are related. Gibson and Mace’s (2007) work on polygyny among the Arsi Oromo in Ethiopia indicated first wives were larger and married at younger ages with higher brideprices than second and third wives. Borgerhoff Mulder (1988) found among the highly polygynous Kipsigis of Kenya that brideprice was higher for “plump” girls, a descriptor that also covered height. Brideprice was also higher for girls reaching menarche at earlier ages.

Nevertheless, in the data presented some advantages may be suggested for delay of reproduction (along with greater growth and/or more education), given its association with the best marital residential locations of each ethnic group. Extended pre-marital parental investment may become desirable and supported where economic development occurs, even in its early stages (Kaplan, 1996). Those who can offer good reproductive locations organized around kinship rules can continue to choose women with greater embodied resources but these qualities now take longer to achieve. The women can then reproduce at a faster pace given these embodied resources plus their new marital resources and help in extended households. Illsley (1955), more than 50 years ago, showed that British women who married into better social circumstances (comparing father’s and husband’s occupations) had better reproductive outcomes than other women, probably a case of higher quality women being selected into these favorable social positions. This argument especially fits the patrilineal Bengali group where families are trying to promote the futures of sons and grandsons in the generally male-biased economy of India. Marriage to a high quality woman promotes this end as she is likely to produce higher quality offspring and her mothering capabilities are enhanced by literacy. Previously reported data on both groups show offspring growth is significantly positively related to mother’s height (Leonetti et al., 2005). Height measurements are only an index of health and somatic resources but even small differences in means, as seen here among Bengali, may reflect greater robusticity that would be visible in other ways to the people involved in arranging these marriages. Height is also associated with education for Bengali. Since among Bengali the groom’s family should generally be of higher status than that of the bride, his family should be able to draw a high quality bride and exogamy can create more control over the bride as her family is not nearby (Mandelbaum, 1970).

The Khasi case has additional dimensions related to cooperative breeding, a practice common among humans (Alexander, 1974; Hrdy, 1999), perhaps stimulating female alliances and underlying matrilineage formation (Knight and Power, 2005; Morgan, 1877). Khasi marital residence rules tend to keep women close to their mothers and sisters. Certainly the positive effects of maternal grandmothers with respect to survival of grand-offspring have been well documented in this and other groups (Lahdenpera et al., 2004; Leonetti et al., 2005, 2007a; Mace and Sear, 2005), as have negative effects in one case (Sear, 2008) where ecological change may have been shifting the kinship system. Documentation of strategizing mothers with intentions to live near daughters has been documented among foragers (Blurton Jones et al., 2005; Scelza and Bliege Bird, 2008). Paternal grandmothers play somewhat different roles as they have no genetic interest in the daughter-in-law, although they may be important in caretaking of grandchildren, as seen among Bengali and others (Leonetti et al., 2005, Stack, 1974; Scelza, personal communication) and be associated with greater resources. Even negative effects of paternal grandmothers have also been shown (Voland and Beise, 2002, 2005; Jamison et al., 2002) as might be expected with the greater potential for conflict with an unrelated daughter-in-law compared to mother-daughter pairs (Voland and Beise, 2005; Cant and Johnstone, 2008). In previous work, Khasi have shown solidarity of the matriline against male mating interests (Leonetti et al., 2007a) and in our data we see the taller, later reproducing women staying close to their mothers. The large height differences seen between Khasi women residing in parental villages (versus not) may even suggest local resource competition among sisters for favorable reproductive locations. The lower fertility of women residing in parental villages, however, suggests that there are costs of mutual support. For the women residing with their mothers who represent the head of the lineage and carry many kin obligations, it may reflect kin selection generating greater inclusive fitness. Since the women living in parental villages whose mothers are alive also enjoy lower offspring mortality, this benefit relative to the cost of lower fertility must be considered as well. Khasi, moreover, are no less sensitive than Bengali to the larger economic environment. They are educating girls as well as boys (Leonetti et al. 2007b). Women have more employment opportunities in this part of India where matriliny is prevalent (State of Meghalaya) so this investment in girls is directly justified via income possibilities as well as indirectly via maternal qualities.

Although we have shown that delayed age at first reproduction (associated with greater height and education) is becoming selected for in the most favorable reproductive locations in these two groups and is possibly compensated by faster pace of fertility, we cannot project greater reproductive success among later marrying women if economic opportunities continue to press people to produce higher quality children. At the time of this study total fertility rates (TFR) in both samples were above 6 children, considerably above pre-demographic transition levels. This important finding of delay in age at first reproduction, however, suggests that households are rising to meet competitive challenges by harnessing greater parental investment to marital placement conducive to use of this investment. Kinship mechanisms are being brought into play via the opportunities they represent for individuals to concentrate embodied capital for the competition ahead as the economy grows. Fertility may even fall first for women in these households if demographic transition is imminent.

The role of kinship and especially lineages in marriage practices and household formation is especially interesting because inclusion/exclusion in households is a process of dispersal, one creating new genetic and phenotypic combinations within cooperating groups. Lineages tend to out-marry, creating circulation of mates within a population given marriage residence rules of exogamy/endogamy (where either women or men circulate). As we have seen, this circulation may be used strategically to enhance breeding arrangements, even beyond the avoidance of inbreeding (Marlowe, 2004). Ecological conditions of subsistence seem to set up cooperative options, with use of large animals (in plow agriculture or pastoralism) and horticulture, respectively conducive to patriliny and matriliny (Aberle, 1961; Goody, 1976). Matriliny may even be replaced by patriliny when large animal husbandry is introduced (Holden and Mace, 2003). The absence of lineage systems is also ecologically appropriate in modern industrial societies and often in forager groups where flexibility is important (Harrell, 1997; Marlowe, 2004; Murdock, 1949; van den Berghe, 1979). In any case, household formation entails a cooperative challenge. In any case, household formation is a basic cooperative challenge. Alvard (2003) points to coordination problems solved by norms regarding whaling group participation according to lineage membership as useful in cooperative endeavors. Household formation, via marriages that create the best possible productive and reproductive future, can also be seen as a problem to be solved to enhance coordination and cooperation appropriate to the subsistence ecology, even as it is transformed by the modern market economy.

The work of Hawkes et al. (1998) has focused on the importance of grandmotherly contributions to grandchild welfare for extension of the human life span substantially past menopause. They have also pointed to delayed maturation and reproduction as a concomitant of this extension, required for developing the requisite somatic resources for sustaining longer life. Our data support viewing the intersection of kinship, cooperative breeding and life span extension as underlying delayed maturation evolutionarily. The intergenerational flow of resources tends to favor certain offspring over others, expecially via residence rules regarding proximity to the senior generation around whom resources are likely concentrated. As we have previously argued (Leonetti et al., 2007a), given greatly extended parental investment in our species, parents have strong motivations to monitor the marital situations of their offspring. Kinship systems appear thereby to have evolved over millennia in apparent attempts by individuals to negotiate resource control and allocation (e.g., via dominance or reciprocity) preferentially among selected kin favored by the local ecology, including support for the best reproductive arrangement. An advantage of these kinship tactics may be to permit cooperative behavior within normatively defined groups (households) that can be mobilized without conflicting allegiances (Alvard, 2003; van den Berghe, 1979). Combining cultural kinship studies with the costs of reproduction and its timing can be ecologically grounded in resource access seen in the critical interplay of kinship resources and marriage rules and reveal paths of change in the construction of human life histories. We suggest here that kinship ideologies (not just kin) can play a selective role in supporting strategic pre-reproductive investment that has been important with respect to evolutionary or facultative shifts in the life history of our species, particularly as this investment shifts in response to changes in resource access.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the INDO-US Programme on Contraceptive and Reproductive Health Research sponsored by the Indian Ministry of Science and Technology and the U.S. National Institute for Child Health and Development; Family Health International; the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation; and the Center for Studies in Demography and Ecology, University of Washington.

Footnotes

Fertility could also continue into older ages but this option butts up against age at menopause a limitation experienced by most women in these high fertility populations and therefore little extra time is available to late starters.

Pre-marital accumulation of capital in the form of dowries can also occur in India but is not applicable in the Bengali community considered here as none are given due to the low socioeconomic level of the group studied. Given Khasi matrilineal system, the logic of dowries also does not apply to them.

When comparing household incomes by status of the grandmothers, household size was not controlled for due to the fact that household composition can vary greatly in these situations both within and between groups and, therefore, the interpretation of the result is not clear. In some cases controlling for household size would control for number of dependents, in other cases it would tend to control for number of earners, and in others simply for the presence of the grandmother, or some combination of these factors. Thus, a finer grained analysis would be necessary to say how the woman’s access to resources was affected by household size. The role of the senior woman, particularly among patrilineal Bengali, in concentrating economic resources is of interest in and of itself but is beyond the scope of this paper.

Contributor Information

Donna L. Leonetti, Department of Anthropology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, 98195-3100, USA

Dilip C. Nath, Department of Statistics, Gauhati University, Guwahati, Assam, INDIA 781014

LITERATURE CITED

- Aberle F. Matrilineal descent in cross-cultural comparison. In: Schneider D, Gough K, editors. Matrilineal kinship. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1961. pp. 655–730. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander R. The evolution of social behavior. Ann Rev Ecol & Syst. 1974;5:325–383. [Google Scholar]

- Alvard M. Kinship, lineage, and an evolutionary perspective on cooperative hunting groups in Indonesia. Human Nature. 2003;14:129–163. doi: 10.1007/s12110-003-1001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blurton Jones N, Hawkes K, O’Connell J. Hadza grandmothers as helpers: residence data. In: Voland E, Chasiotis A, Schiefenhovel A, editors. Grandmotherhood: The evolutionary significance of the second half of female life. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press; 2005. pp. 160–176. [Google Scholar]

- Borgerhoff Mulder M. Kipsigis bridewealth payments. In: Betzig L, Borgerhoff Mulder M, Turke P, editors. Human reproductive behavior. A Darwinian Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1988. pp. 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Cant MA, Johnstone RA. Reproductive conflict and the separation of reproductive generations in humans. PNAS. 2008;105:5332–5336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711911105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charnov E, Berrigan D. Why do female primates have such long lifespans and so few babies? Or life in the slow lane. Evolutionary Anthropology. 1993;2:191–194. [Google Scholar]

- Drake M. Population and society in Norway: 1735–1865. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson M, Mace R. Polygygy, reproductive success and child health in rural Ethiopia: Why marry and married man? Journal of Biosocial Science. 2007;39:287–300. doi: 10.1017/S0021932006001441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goody J. Production and Reproduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Hajnal J. Household formation patterns in historical perspective. Population and Development Review. 1965;8:449–494. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton W. The genetic evolution of social behavior. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 1964;7:1–52. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(64)90038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell S. Human Families. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes K, O’Connell JF, Blurton Jones NG. Hadza women’s time allocation, offspring provisioning, and the evolution of long post-menopausal life spans. Current Anthropology. 1997;38:551–577. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes K, O’Connell J, Blurton Jones N, Alvarez H, Charnov E. Grandmothering, menopause and the evolution of human life histories. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95:1336–1339. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill K. Life history theory and evolutionary anthropology. Evolutionary Anthropology. 1993;2:78–88. [Google Scholar]

- Holden C, Mace R. Spread of cattle led to the loss of matrilineal descent in Africa: a co-evolutionary analysis. Proceedings of the Royal Society London B. 2003;270:2425–2433. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden C, Sear R, Mace R. Matriliny as daughter-biased investment. Evolution and Human Behavior. 2003;24:99–112. [Google Scholar]

- Hrdy SB. Maternal instincts and how they shape the human species. New York: Ballantine Books; 1999. Mother nature. [Google Scholar]

- Illsley R. Social class selection and class differences in relation to stillbirth sand infant deaths. British Medical Journal. 1955;(Dec 24):1520–1524. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.4955.1520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamison ES, Cornell LL, Jamison PL, Nakazato H. Are all grandmothers equal? A review and preliminary test of the “grandmother hypothesis” in Tokugawa, Japan. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 2002;119:67–76. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.10070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan H. A theory of fertility and parental investment in traditional and modern human societies. Yearbook of Physical Anthropology. 1996;39:91–135. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan H, Hill K, Lancaster J, Hurtado AM. A theory of human life history evolution: Diet, intelligence, and longevity. Evolutionary Anthropology. 2000;9:156–185. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan H, Lancaster J, Tucker WT, Anderson KG. Evolutionary approach to below replacement fertility. American Journal of Human Biology. 2002;14:233–256. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.10041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchengast S, Hartman B, Schweppe KW. Impact of maternal body build characteristics on newborn size in two different European populations. Human Biology. 1998;70:761–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight C, Power C. Grandmothers, politics, and getting back to science. In: Voland E, Chasiotis A, Schiefenhovel A, editors. Grandmotherhood: The evolutionary significance of the second half of female life. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press; 2005. pp. 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- Lahdenpera M, Lummaa V, Helle S, Tremblay M, Russell AF. Fitness benefits of prolonged post-reproductive lifespan in women. Nature. 2004;428:178–181. doi: 10.1038/nature02367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonetti DL, Nath DC, Hemam NS, Neill DB. Kinship Organization and the Impact of Grandmothers on Reproductive Success among the Matrilineal Khasi and Patrilineal Bengali of Northeast India. In: Voland E, Chasiotis A, Schiefenhovel A, editors. Grandmotherhood: The evolutionary significance of the second half of female life. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press; 2005. pp. 194–214. [Google Scholar]

- Leonetti DL, Nath DC, Hemam NS. In-law conflict: Women’s reproductive lives and the roles of their mothers and husbands among the matrilineal Khasi. Current Anthropology. 2007a;48:861–890. [Google Scholar]

- Leonetti DL, Nath DC, Heman NS. The behavioral ecology of family planning. Two ethnic groups in Northeast India. Human Nature. 2007b;38:225–241. doi: 10.1007/s12110-007-9010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low B. Women’s lives there, here, then now: a review of women’s ecological and demographic constraints cross-culturally. Evolution and Human Behavior. 2005;26:64–87. [Google Scholar]

- Low B, Clarke A. Resources and the life course: patterns through the demographic transition. Ethnology and Sociobiology. 1992;13:463–494. [Google Scholar]

- Mace R. Evolutionary ecology of human life history. Animal Behavior. 2000;59:1–10. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1999.1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mace R, Sear R. Are humans cooperative breeders? In: Voland E, Chasiotis A, Schiefenhovel A, editors. Grandmotherhood: The evolutionary significance of the second half of female life. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press; 2005. pp. 143–159. [Google Scholar]

- Mandelbaum DG. Society in India. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Marlowe F. Marital residence among foragers. Current Anthropology. 2004;45:277–284. [Google Scholar]

- Martorell R, Delgado H, Valverde V, Klein R. Maternal stature, fertility and infant mortality. Human Biology. 1981;53:303–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan LH. Ancient Society. London: MacMillan; 1877. [Google Scholar]

- Murdock GP. Social Structure. New York: Macmillan; 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan RJ. Gender and risk in a matrifocal Caribbean community: A view from behavioral ecology. American Anthropologist. 2005;108:464–479. [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan RJ. Human parental effort and environmental risk. Proceedings Royal Society B Biological Sciences. 2007;274 (1606):121–125. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravichandran N. Propulation, reproductive health and development. New York: Population Council; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Scelza B, Bliege Bird R. Group structure and female cooperative networks in Australia’s Western Desert. Human Nature. 2008;19:231–248. doi: 10.1007/s12110-008-9041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sear R. Kin and child survival in rural Malawi. Human Nature. 2008;19:277–293. doi: 10.1007/s12110-008-9042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sear R, Allal N, Mace R. Height, marriage and reproductive success in Gambian women. Socioeconomic aspects of human behavioral ecology. In: Alvard M, editor. Special volume of Research in Economic Anthropology. Vol. 23. 2004. pp. 203–224. [Google Scholar]

- Shenk MK. Causes and consequences of the demographic transition in urban south India: Transitions in total fertility and age of first reproduction. International Union for the Scientific Study of Population International Seminar on Tarde-0offs in Female Life Histories: Raising New Questions in an Integrative Framework; Bristol, United Kingdom. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Stack CB. Strategies for survival in a Black community. Harper & Row Publications; New York: 1974. All our kin. [Google Scholar]

- van den Berghe P. Human family systems: An evolutionary view. New York: Elsevier; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Voland E, Beise J. Opposite effects of maternal and paternal grandmothers on infant survival in historical Krummhorn. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 2002;52:435–443. [Google Scholar]

- Voland E, Beise J. ‘The husband’s mother is the devil in house’ Data on the impact of the mother-in-law on stillbirth mortality in historical Krummhorn (1750–1874) and some thoughts on the evolution of postgenerative female life. In: Voland E, Chasiotis A, Schiefenhovel A, editors. Grandmotherhood: The evolutionary significance of the second half of female life. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press; 2005. pp. 239–255. [Google Scholar]

- Voland E, Siegelkow E, Engel C. Cost/benefit oriented parental investment by high status families. Ethology and Sociobiology. 1991;12:105–118. [Google Scholar]

- Winkvist A, Rasmussen K, Lissner L. Associations between reproduction and maternal body weight: Examining the component parts of a full reproductive cycle. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2003;57:114–127. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witter F, Caulfield L, Stoltzfus R. Influence of maternal anthropometric status and birth weight on the risk of cesarean delivery. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1995;85:947–951. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]