Abstract

The chemokine receptor, CXCR4, plays an essential role in guiding neural development of the CNS. Its natural agonist, CXCL12 [or stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1)], normally is derived from stromal cells, but is also produced by damaged and virus-infected neurons and glia. Pathologically, this receptor is critical to the proliferation of the HIV virus and initiation of metastatic cell growth in the brain. Anorexia, nausea and failed autonomic regulation of gastrointestinal (GI) function cause morbidity and contribute to the mortality associated with these disease states. Our previous work on the peripheral cytokine, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, demonstrated that similar morbidity factors involving GI dysfunction are attributable to agonist action on neural circuit elements of the dorsal vagal complex (DVC) of the hindbrain. The DVC includes vagal afferent terminations in the solitary nucleus, neurons in the solitary nucleus (NST) and area postrema, and visceral efferent motor neurons in the dorsal motor nucleus (DMN) that are responsible for the neural regulation of digestive functions from the oral cavity to the transverse colon. Immunohistochemical techniques demonstrate a dense concentration of CXCR4 receptors on neurons throughout the DVC and the hypoglossal nucleus. CXCR4-immunoreactivity is also intense on microglia within the DVC, though not on the astrocytes. Physiological studies show that nanoinjection of SDF-1 into the DVC produces a significant reduction in gastric motility in parallel with an elevation in the numbers of cFOS-activated neurons in the NST and DMN. These results suggest that this chemokine receptor may contribute to autonomically mediated pathophysiological events associated with CNS metastasis and infection.

Keywords: chemokines, gastric, hindbrain, vagus

Introduction

Chemokine receptors in the brain are significant regulators of neural development and also play a critical role in neural pathophysiology. Successful brain development is critically dependent on the CXCR4 receptor. Deletion of either the gene for the CXCR4 receptor or its agonist, stromal cell-derived factor-1 (i.e. SDF-1 or CXCL-12), causes grossly abnormal neural development (Lu et al., 2002; Li & Pleasure, 2005). The pleiotropic nature of this agonist / receptor combination is revealed by the involvement of SDF-1 / CXCR4 in neurological disorders associated with neuroinflammation, such as multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases (Ransohoff et al., 1996; Glabinski et al., 2000). The SDF-1 / CXCR4 interaction also appears to be critical in the initiation and maintenance of glial metastasis (Gabuzda & Wang, 2000). Furthermore, the CXCR4 receptor may serve as the portal of entry by the HIV virus into neurons and glia in acquired immune deficiency syndrome (Gabuzda & Wang, 2000).

CNS neuroinfection and metastasis, processes that are correlated with elevated SDF-1 (Gabuzda & Wang, 2000), are also accompanied by a morbidity or sickness syndrome variously comprised of anorexia, nausea, emesis and failed gastrointestinal (GI) transit (Plata-Salaman, 2000; Lazarini et al., 2003; Elenkov et al., 2005; Lagman et al., 2005). This suggests that another site of action of SDF-1 may be within the neural circuitry involved in the control of gastric function.

The medullary circuits responsible for coordinating autonomic reflex control of the gut are contained within the dorsal vagal complex (DVC). The DVC is composed of the nucleus of the solitary tract (NST) and area postrema (AP), which receive the general visceral afferent input from the afferent vagus, and the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMN), which is the principal source of parasympathetic efferent control over the GI tract. The NST is an important organizer and processor of visceral afferent activity, and it regulates GI function via vago-vagal reflex connections with the DMN (see Rogers et al., 2005 for review). The NST is also critically important for the production of emesis (Andrews & Horn, 2006). Indeed, the perception of nausea associated with emesis may be the subliminal awareness of the profound gastric relaxation that precedes the emetic act (Andrews et al., 1990; Miller, 1999; Hornbuckle & Barnett, 2000; Andrews & Horn, 2006). The NST is also the first CNS sensory neuron involved in relaying information about the nutritional status of the viscera to more rostral brainstem and diencephalic structures involved in the control of feeding behavior and energy balance. Thus, these rostral-projecting NST neurons are activated by stimuli associated with both satiety and anorexia (Berthoud, 2002; Grill & Kaplan, 2002).

Perhaps the misregulation of autonomic functions that attends CNS neuroinflammation and metastasis may involve activation of the CXCR4 receptor within the caudal brainstem, i.e. the DVC. These studies were designed to: (i) demonstrate the existence of these receptors in the hindbrain; (ii) verify activation of these receptors by the agonist; and (iii) identify potential physiological consequences of the activation of these receptors.

Materials and methods

Long–Evans rats (200–400 g; either gender), obtained from the breeding colony located at Pennington Biomedical Research Center, were used in these studies. All animals were maintained in a room with a 12 : 12 h light : dark cycle with constant temperature and humidity, and given food and water ad libitum. Rats were randomly assigned to one of four different experimental studies. All experimental protocols were performed according to the guidelines set forth by the National Institutes of Health, and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the Pennington Biomedical Research Center.

Distribution and phenotypic identification of hindbrain cells possessing CXCR4 receptors – double immunohistochemical (IHC) studies

IHC staining techniques were used to locate CXCR4 receptor-bearing elements in the CNS. Identification of these CXCR4-positive components was investigated by IHC staining for neurons [i.e. neuron-specific nuclear antibody (NeuN); Wolf et al., 1996; vs glia (i.e. glial fibrillary acidic protein, GFAP; Debus et al., 1983; Hermann et al., 2001a). Further characterization of these CNS-CXCR4-positive elements was pursued by IHC staining for specific subsets of neurons [i.e. tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) identifies presumptive catecholaminergic neurons (Cuello et al., 1983); neuronal nitric oxide synthase (NOS) identifies nitrergic neurons (Norris et al., 1995); glutamate acid decarboxylase (GAD)-67 identifies γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurons (Fong et al., 2005) choline acetyl transferase (ChAT) identifies cholinergic neurons (Manier et al., 1987)]. The possibility that CXCR4 receptors were located on dendritic processes was evaluated by IHC for neurofibrillary protein (NF; Hermann et al., 2001a). Lastly, further characterization of specific subsets of glia was evaluated by IHC for microglial-specific antigen (OX-42; Hermann et al., 2001a) and oligodendrocyte-specific antigen (CNPase; Hermann et al., 2001a).

Animals (N = 26) were anesthetized with urethane (ethyl carbamate, Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA; 1 g / kg, i.p.) and transcardially perfused with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. The brain was removed from the cranium and postfixed overnight in a 30% sucrose solution at 4 °C. The brainstem and cortex were cut into 40-micron sections on a freezing microtome. [Histological sections of the cortex served as positive control comparisons with previous work by Banisadr et al. (2002, 2003)].

The free-floating histological sections were placed in PBS prior to dual immunofluorescence staining. (Note: between each incubation step the sections were triple-rinsed in PBS; 5 min per rinse.) The tissue sections were pretreated with 1% sodium borohydride to remove residual aldehyde fixative. To quench endogenous peroxidase, the tissue was placed in a 0.3% hydrogen peroxide solution. The blocking step consisted of 3% normal donkey serum, 0.1% Triton X-100 and PBS for 2 h. After a brief PBS rinse, the sections were incubated in a cocktail of dual primary antibodies: anti-human CXCR4 [fusin (C-20) 1 : 50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA; cat. no. sc-6190; goat polyclonal], plus one of the following identifying cellular phenotype antibodies overnight at room temperature on a shaker table:

TH (1 : 500; ImmunoStar, Hudson, WI, USA, cat. no. 22941; mouse monoclonal)

ChAT (1 : 200; Chemicon, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA; cat. no. AB5042; rabbit polyclonal)

GAD (identifies GABAergic neurons, GAD-67, 1 : 500; Chemicon, cat. no. MAB5406; mouse monoclonal)

NeuN (1 : 500; Chemicon; cat. no. MAB377; mouse monoclonal)

GFAP (1 : 500; Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA; cat. no. Z0334; rabbit polyclonal)

Microglia marker (OX-42, 1 : 500; Chemicon; cat. no. CBL1512; mouse monoclonal)

Oligodendrocyte marker (CNPase, 1 : 200; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA; cat. no. AB6319; mouse monoclonal)

Cytoskeleton NF (1 : 200; Chemicon; cat. no. MAB1623; mouse monoclonal).

To demonstrate the CXCR4 receptor, a tyramide signal amplification [Perkin Elmer-NEN Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA) Kit] was applied to the tissue sections. Briefly, following incubation in appropriate secondary antibody, the sections were placed in Vector Elite avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (Vector Laboratories) for 1 h. The tissue was then placed in the TSA-FITC (1 : 50) solution for 5 min. The sections were mounted on gelatine-coated slides and coverslipped with Vectashield.

Localization of CXCR4 receptors on identified gastric-projecting DMN neurons

Our preliminary IHC results suggested that the CXCR4 receptors were densely concentrated on neurons of the DMN of the vagus. To determine if the CXCR4-labeled DMN neurons were those that projected to the stomach, rats (n = 4) were anesthetized with pentobarbital (50 mg / kg, i.p.; Nembutal; Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL, USA). Using aseptic techniques, an abdominal laparotomy was performed and rhodamine-coated latex nanospheres (Lumafluor, Naples, FL, USA) were injected in the fundus and corpus of the stomach. Between 10 and 15 nanoinjections (1 μL volume / injection) of a neat solution of the spheres were made in each rat to specifically label gastric DMN neurons by retrograde transport (Zheng et al., 1999). After wound closure and recovery from the anesthesia, the animals were returned to their home cages. Rhodamine-coated beads were allowed to transport retrogradely up the vagus nerve for 7–10 days. At this time, rats were re-anesthetized and transcardially perfused as described above; histological sections were prepared for IHC staining for CXCR4. Distribution of CXCR4-immunoreactivity on rhodamine-prelabeled gastric-projecting DMN neurons was evaluated.

SDF-1-mediated CXCR4 activation of cFOS

Separate studies examined the effects on neuronal activation, as estimated by cFOS upregulation, evoked by SDF-1 within the DVC. Rats (total n = 24) were anesthetized with the long-acting thiobuta-barbital (Inactin, 150 mg / kg i.p., Sigma). This anesthetic is known not to interfere with autonomic reflexes or cytokine production (Buelke-Sam et al., 1978; Hermann et al., 1999); additionally, this agent does not independently induce cFOS activation as has been observed with urethane (Takayama et al., 1994). The anesthetized animal was placed in a stereotaxic frame. Using aseptic technique, the floor of the fourth ventricle was exposed as described in previous studies (Hermann & Rogers, 1995; Hermann et al., 2005a; Hermann et al., 2006).

Glass micropipettes for direct injection into the DVC were pulled using a vertical pipette puller (Model PE-2, Narishige, Japan) and beveled (Model BV-10, Sutter Instrument, Novato, CA, USA) such that finished micropipettes had sharply beveled tips with an inner diameter of 20–30 microns. Micropipettes were filled with 10−5, 10−6 or 10−7 m SDF-1 (dissolved in PBS) or PBS alone.

Rats received unilateral injections of one of the four conditions listed above into the NST / DMN border area (0.3 mm lateral and 0.3 mm anterior to calamus scriptorum; 0.35 mm below brainstem surface). Nanoinjections (40 nL volume) of either SDF-1 (10−5 m, n = 6; 10−6 m, n = 5; 10−7 m, n = 4) or PBS (n = 5) were made into the DVC (total dose, 3.2 ng, 0.3 ng, 0.03 ng or 0 ng SDF-1, respectively) via a micropressure controller under direct visual guidance (see Rogers & Hermann, 1985 for description). A fifth group of rats (n = 4) was used to demonstrate that the specific CXCR4 antagonist, AMD3100 (octahydrochloride, Sigma-Aldrich) could functionally block the ability of SDF-1 to activate CXCR4 receptors. In this case, double-barrel micropipettes (40 micron total outer diameter) were used to deliver the antagonist and agonist to the same site (as described above); one barrel contained SDF-1 and the other contained AMD3100. The nanoinjection of the antagonist, AMD3100 (1 ng in 40 nL) immediately preceded the microinjection of SDF-1 (0.32 ng in 40 nL; ratio of agonist to antagonist determined as per Schols et al., 1997). All other preparations and processing was identical to the other cFOS groups. To allow for maximal cFOS activation in response to agonist exposure, these anesthetized rats survived for an additional 90 min post-injection, at which point they were transcardially perfused and prepared for cFOS IHC as described previously (Hermann et al., 2001a,b; Rogers et al., 2003).

All sections through the medullary brainstem were saved and processed for the demonstration of nuclear cFOS protein, a marker for prolonged and significant neuronal excitation (Rinaman et al., 1993). This protocol is available in detail elsewhere (Rinaman et al., 1993; Hermann et al., 2001b). Briefly, all tissue sections were rinsed in PBS and incubated in sodium borohydride and hydrogen peroxide to eliminate remaining fixative and to block endogenous peroxidase. Sections were then rinsed and blocked in 5% normal goat serum, re-rinsed in PBS and then incubated in rabbit, anti-rat cFOS primary antibody (cFOS, 1 : 20 000; Oncogene Science Diagnostics, La Jolla, CA, USA; AB-5; rabbit polyclonal) overnight at room temperature on a shaker table. Sections were rinsed in PBS and incubated with biotinylated goat, anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1 : 600; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). Sections were rinsed in PBS and incubated in Vector ABC peroxidase reagent, followed by the Vector peroxidase chromogen Nova Red. cFOS staining was revealed in this protocol as brick-red nuclei. Omission of primary antibody or incubation with inappropriate secondary antibody produced no cFOS label.

Neurons within the DVC area that demonstrated nuclei positive for cFOS-immunoreactivity (cFOS-ir) were counted in all hindbrain sections that included the AP (i.e. the immediate area of the injection site). Inclusion of labeled neurons required that their nuclei be a minimum of 6 μm in diameter and exhibit a nucleolus. These criteria guaranteed that staining artifacts and nuclear fragments would not be included in the count. An investigator unaware of the experimental condition being analysed counted cFOS-stained nuclei; a second observer verified counts. The agreement between counts of the two observers was within 10%. Counts of cFOS+ neurons located in the NST and DMN ipsilateral to the side of injection as well as those nuclei contralateral to the side of injection were tallied separately. The total number of cFOS neurons in each of these areas was divided by the number of histological sections (i.e. averaged number of positive cells per histological section per animal), and this figure was used for statistical comparison. Numbers of cFOS-activated NST neurons ipsilateral to the injection under each stimulation condition were compared statistically using one-way analysis of variance (anova); values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Dunnett’s post hoc comparisons against the PBS control nano-injections were made.

Microscopic imaging was done with a Nikon E800 equipped with both normal epifluorescence illumination as well as a Perkin Elmer CSU10-Ultraview laser confocal system. Images were captured with a Hamamatsu Orca-ER CCD camera.

Effects of SDF-1 in the DVC on gastric motility

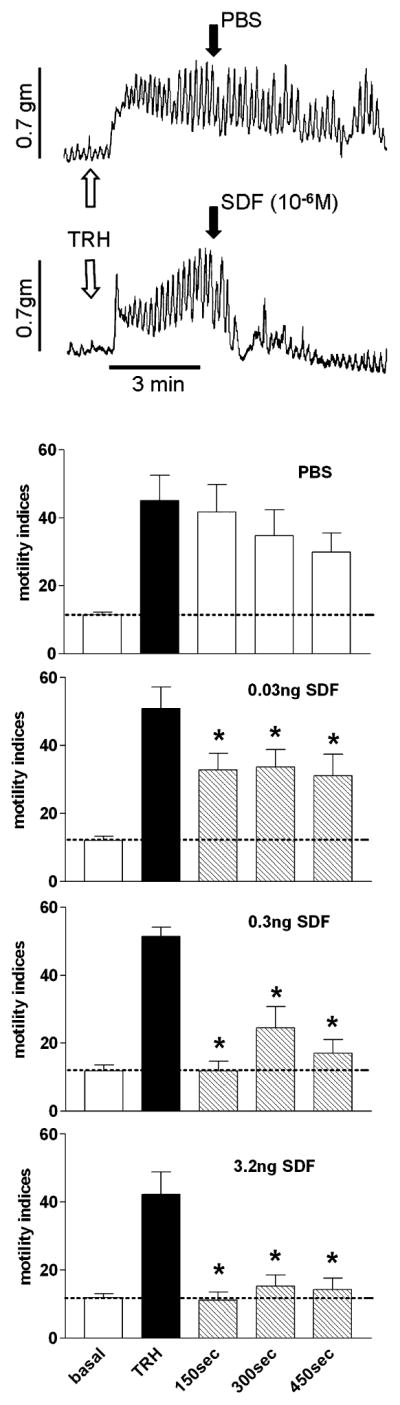

Modulation of gastric function by SDF-1 in the DVC was examined in 32 rats that had been anesthetized with thiobutabarbital and instrumented with a miniature strain gage (RB Products, Madison, WI, USA) on the corpus of the stomach (see full description in Hermann & Rogers, 1995). These anesthetized and instrumented rats were mounted in a stereotaxic frame; the floor of the fourth ventricle was exposed as described previously (Hermann & Rogers, 1995). Strain gage data were monitored continuously and collected in real time on a polygraph, and stored on a PC-based data logger for additional analysis (Data Pac 2000, Laguna Hills, CA, USA). Basal gastric motility and tone of fasted, anesthetized animals tend to be minimal. Given that we predicted SDF-1 to reduce gastric tone and motility, we applied 0.2 nmoles (2 μL of 100 μm = 0.07 ng) of thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) onto the floor of the fourth ventricle to activate vagal efferent pathways to the stomach (McCann et al., 1988; Hermann & Rogers, 1995). TRH acts within the DVC by both activating vagal cholinergic efferent neurons in the DMN and inhibiting NST neurons that receive afferent input from the gut (Rogers et al., 2005), thus resulting in a profound increase in gastric motility (Hermann & Rogers, 1995). This TRH-induced increase in gastric motility reaches a plateau within 5 min of application, at which time 40 nL volume of either SDF-1 (10−5 m, n = 7; 10−6 m, n = 7; 10−7 m, n = 7) or PBS (n = 9) was unilaterally nanoinjected into the DVC (total dose, 3.2 ng, 0.3 ng, 0.03 ng or 0 ng SDF-1, respectively), as described above.

Gastric motility was continuously monitored via the miniature strain gage connected to a Wheatstone bridge-based amplifier. Each gage was calibrated with specific weights; calibration curves convert voltage data from the amplifier into approximate grams of force. Motility data were converted to motility indices (MIs) for statistical and graphic purposes according to Ormsbee & Bass (1976). Essentially, gastric contractions recorded by the strain gage are graded according to the relationship:

where MI is a quantification of motility per unit time (e.g. 150 s); nA1–2 is the number of contractions in the amplitude range from just-detectable to twice just-detectable; nA2–4 is the number of contractions in the amplitude range of 2–4 × larger than just-detectable, etc. MIs were collected for five 150-s time periods: (i) ‘Basal’, 150 s prior to TRH application; (ii) ‘TRH effect’, during the plateau phase of the TRH-mediated increase in gastric motility and150 s before SDF-1 nanoinjection; (iii)–(v) ‘SDF-1 effect’, 0–150 s, 150–300 s and 300–450 s, respectively, after SDF-1 nanoinjection. MI data from each of the three treatment groups were analysed across the five time points. As appropriate, repeated-measures anova for each group was followed by Dunnett’s post hoc tests. Comparisons were made between the TRH-stimulated MI (i.e. ‘control’ period) and the suppression induced by SDF-1 nanoinjections into the DVC.

Results

Localization of CXCR4 receptors using IHC

Technical validation of immunohistochemistry: CXCR4-ir in cortex and caudate putamen

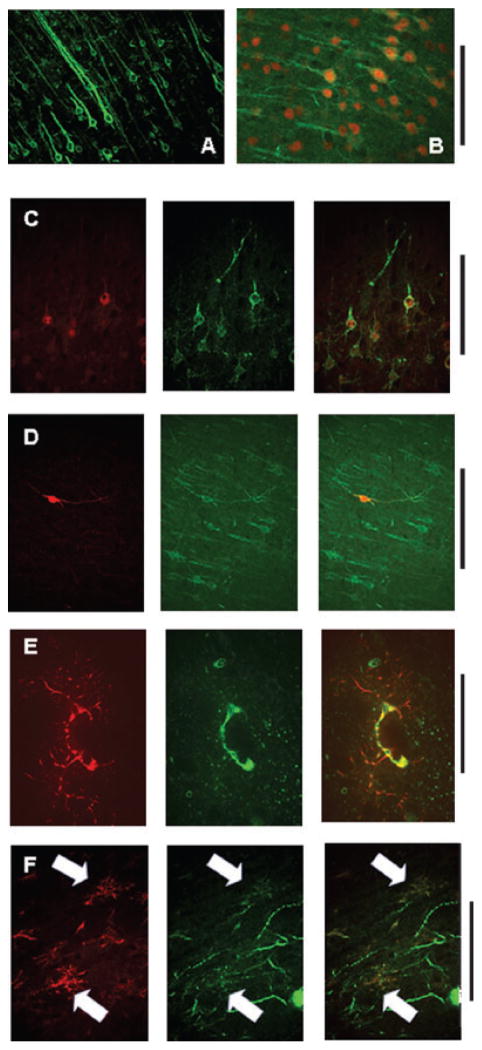

Previous work has shown that the CXCR4 receptor is distributed widely, but not uniformly, within the brain, anterior to the medulla (Banisadr et al., 2002, 2003). To validate our own IHC methods, we sought to replicate the essential findings of Banisadr’s laboratory as well as investigate the distribution of these receptors in the hindbrain. Figure 1 shows that, as previously reported, the CXCR4 receptor is found on neurons, astrocytes and microglia within the cortex and caudate putamen. The CXCR4-ir appears concentrated on proximal dendrites. Our IHC staining confirmed that a substantial majority of NeuN-ir and ChAT-ir cells (i.e. cholinergic neurons) in the cortex possess the CXCR4 receptor. Additionally, we observed occasional instances where NOS-ir-positive cortical interneurons coexpressed the CXCR4 receptor as well. While TH-ir (catecholaminergic) fibers permeate the cortex and caudate putamen, these fibers did not show CXCR4-ir (data not shown). As previously reported (Banisadr et al., 2002), we too observed that essentially all astrocytes (GFAP-ir-positive) and microglia (OX42-ir-positive) in the cerebral cortex and the caudate putamen were double-labeled for the phenotypic glial markers as well as for CXCR4. Oligodendroglia (CNPase-ir positive) in the cortex did not express CXCR4 (data from cortex not shown, but see Fig. 4 showing a lack of double CXCR-CNPase immunoreactivity in the medulla).

Fig. 1.

IHC methods described by Banisadr et al. (2002, 2003) were used to replicate their observations of CXCR4 receptor expression on neurons and glia widely throughout the cortex and caudate / putamen. These same methods were applied to our investigations of CXCR4 receptor expression in the hindbrain (Figs 2–6). Note: CXCR4-ir was green and all phenotypic identification IHC was red. (A) CXCR4-ir alone in cortical layer five; scale: 1 mm. (B) NeuN-CXCR4 double-labeled neurons in cortical layer five; scale: 0.5 mm. (C) ChAT-CXCR4 double-ir in cortical neurons; scale: 0.5 mm. (D) NOS-CXCR4 double-ir-labeled cortical interneuron; scale: 0.5 mm. (E) GFAP-CXCR4 double-ir-labeled astrocyte in cortex seen surrounding a capillary cut in cross-section; scale: 50 microns. (F) OX42-CXCR4 double-ir-labeled microglia in the border between external capsule and caudate / putamen; scale: 50 microns. (C–F) Phenotype-ir, left column (red); CXCR4-ir, middle column (green); merged image, right column (yellow, colocalization).

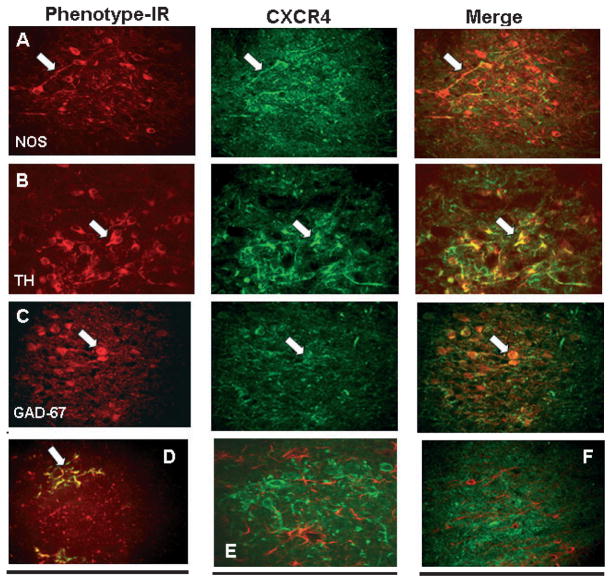

Fig. 4.

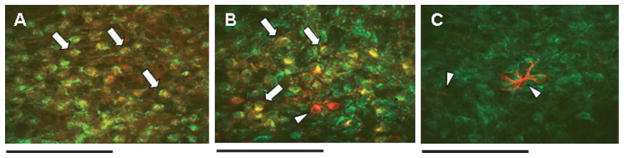

Phenotypic identification (red, phenotypic-ir; e.g. NOS, TH, GAD-67, OX-42, GFAP and CNPase) of cells in the NST that express CXCR4 receptors (green, CXCR4-ir). Virtually all NOS+, TH+ and GAD-67+ neuronal phenotypes, as well as microglia, also express CXCR4 receptors. Arrows point out prominent double-labeled features in the different plates. (A) Nitrergic (NOS-ir; left panel) NST neurons express CXCR4 (CXCR-ir; middle panel) receptors (merged image; right panel). (B) Catecholaminergic (TH-ir) NST neurons express CXCR4 receptors. (C) GABAergic (GAD-67-ir) NST neurons express CXCR4 receptors. (D) Microglia (OX-42-ir) in the NST express CXCR4 receptors. (E) Unlike astrocytes in the cortex (see Fig. 1), astrocytes (red, GFAP-ir) in the NST do NOT express CXCR4 (green) (see also astrocytes in AP in Fig. 7C). Note that this region of the hindbrain does not have a functional blood–brain barrier. (F) Similar to oligodendrocytes in the cortex, oligodendrocytes (CNPase-ir) in the NST do not express CXCR4. Scale bar: 100 microns (A–C); 20 microns (D–F). GAD-67, glutamate acid decarboxylase-67; NOS, neuronal nitric oxide synthase; TH, tyrosine hydroxylase.

Distribution and phenotypic identification of hindbrain cells possessing CXCR4 receptors

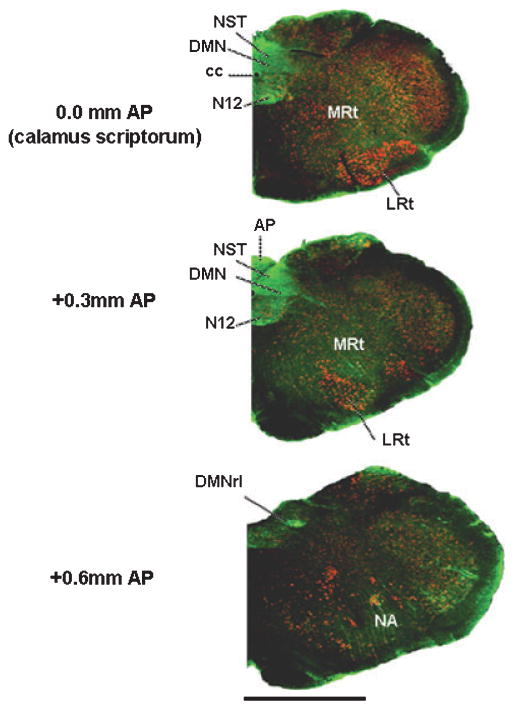

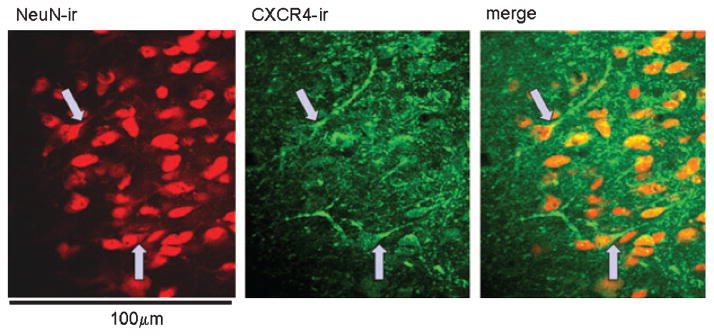

A low-power image of the medulla in cross-section (Fig. 2) shows that CXCR4-ir is concentrated heavily within the DVC (i.e. AP, NST and DMN). CXCR-ir label is also apparent in the hypoglossal and ambiguus nuclei. IHC studies staining for neurons (NeuN-ir) that possess CXCR receptors indicate that virtually all NST neurons express CXCR4-ir. The label is most apparent on the proximal dendrites, as illustrated in Figs 3 and 4. The impression of uniform expression of CXCR4-ir in the NST is reinforced by observations of colocalization on TH, NOS and GAD-67-ir neurons.

Fig. 2.

Low-magnification coronal view of caudal medullary hemisections at the level of the calamus scriptorum (levels are 0.0 mm, 0.3 mm anterior and 0.6 mm anterior to calamus) immunohistochemically stained for CXCR4 receptors. CXCR4 receptors are intensely concentrated in the DVC (AP, NST and DMN), and are also apparent in the hypoglossal and ambiguus motor nuclei. Green, CXCR4-ir; red, NeuN-ir (neurons). Scale bar: 2000 microns. AP, area postrema; cc, central canal; DMN, dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus; DMNrl, rostro-lateral portion of the DMN; LRt, lateral reticular nucleus; MRt, medial reticular nucleus; N12, hypoglossal nucleus; NA, nucleus ambiguous; NST, solitary nucleus.

Fig. 3.

Medial NST showing that virtually all neurons (red, NeuN-ir; left panel) in this region express CXCR4 receptors (green, CXCR4-ir; middle panel), primarily on their proximal dendrites (merged image; right panel). Arrows show some of the clearer examples. Scale bar: 100 microns. NeuN, neuron-specific nuclear antibody.

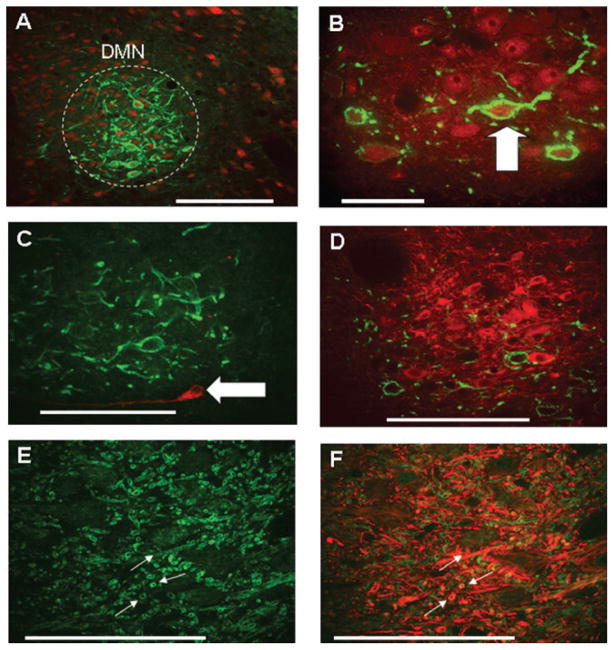

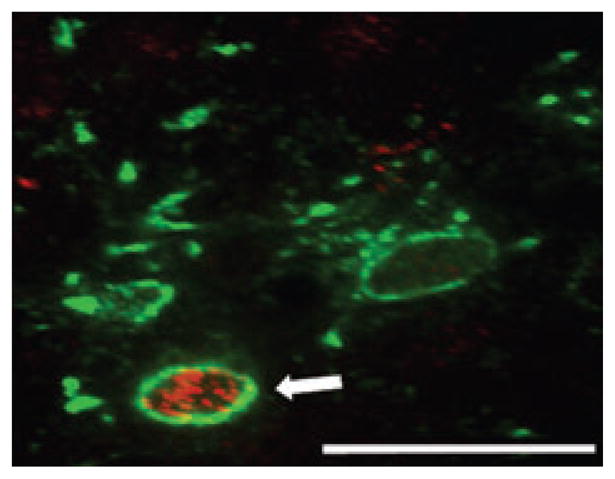

Labeling for CXCR4-ir in the DMN appeared throughout this structure, but was concentrated principally in the rostral and lateral portions. CXCR4-ir was colocalized to DMN neurons of the ChAT (cholinergic) phenotype (Fig. 5A and B). As previously described (Kalia et al., 1984; Krowicki et al., 1997; Zheng et al., 1999; Guo et al., 2001), the DMN possesses catecholaminergic (TH+) and nitrergic (NOS+) neurons, though none of these was CXCR4-positive (Fig. 5C and D). Hypoglossal neurons also express CXCR4-ir, primarily on the proximal dendrites (Fig. 5E and F). Of the 264 DMN neurons (n = 4 rats) that were specifically labeled with rhodamine nanospheres after retrograde transport from gastric wall injections, 239 (90%) were immunopositive for the CXCR4 receptor (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

CXCR4 receptors on vagal motor neurons in the dorsal motor nucleus (DMN) and hypoglossal nucleus are only found on the ChAT phenotype. Note: red, phenotypic identification; green, CXCR4-ir. (A) Low-magnification photomicrograph showing dense CXCR4 receptor expression (green, CXCR-ir) on DMN neurons [red, NeuN (neuron-specific nuclear stain)]. (B) High-magnification photomicrograph showing CXCR4-ir on ChAT-ir DMN neurons. Note that practically all CXCR4-ir neurons in the DMN were also ChAT-positive. (C) A few neurons in the DMN are TH-ir (red; Armstrong et al., 1990), though none was CXCR4-immunoreactive. (D) Though a number of rostro-lateral DMN neurons are NOS-ir positive (red; Krowicki et al., 1997; Zheng et al., 1999; Guo et al., 2001), none was CXCR4-immunoreactive. (E) Dendritic neuropil in the hypoglossal nucleus is CXCR4-immunopositive (green). (F) Same field as (E) showing colocalization of CXCR4-ir on neurofilaments (NF-ir, red). Scale bar: 100 microns (A, C–F); 50 microns (B).

Fig. 6.

Rhodamine-dextran-covered latex nanospheres injected into the wall of the stomach were used to identify gastric-projecting DMN neurons. Of 264 DMN neurons retrogradely labeled with rhodamine spheres (rhodamine label, red), 239 (i.e. 90%) expressed CXCR4 receptors (CXCR4-ir, green). Scale bar: 75 microns.

Although the focus of this study was to determine the localization and possible physiological function of CXCR4 receptors on vago-vagal circuitry directly involved in gastric function (Rogers et al., 2005), it is clear that these receptors are localized on components of the AP. While complete characterization of AP phenotypes is material for its own study, it appears that, not unlike the NST, CXCR4-ir is uniformly expressed on neurons (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Not unlike the NST (see Fig. 4), virtually all neurons in the AP express CXCR4 receptors and astrocytes do not. (A) Cholinergic (ChAT-ir; red) AP neurons express CXCR4 receptors (green); colocalization appears yellow (examples at arrows). (B) Catecholaminergic (TH-ir; red) AP neurons express CXCR4 receptors (green); colocalization appears yellow. Note two rare TH-ir neurons that do not possess CXCR4 receptors (indicated at triangle). (C) Not unlike the NST, astrocytes (GFAP-ir; red), indicated at triangles, in the AP do not possess CXCR4 receptors (green). Scale bars: 80 microns (A); 40 microns (B); 20 microns (C).

Microglia (OX42-ir-positive) in the hindbrain were uniformly positive for CXCR4-ir. Additionally, as observed in the cortex, oligodendrocytes (CNPase-ir-positive) did not express CXCR4-ir. Surprisingly, in contrast to the cortex, astrocytes (GFAP-ir-positive) in the dorsal medulla, including the AP, did not express CXCR4-ir (Figs 1, 4 and 8, compare with Banisadr et al., 2002).

Fig. 8.

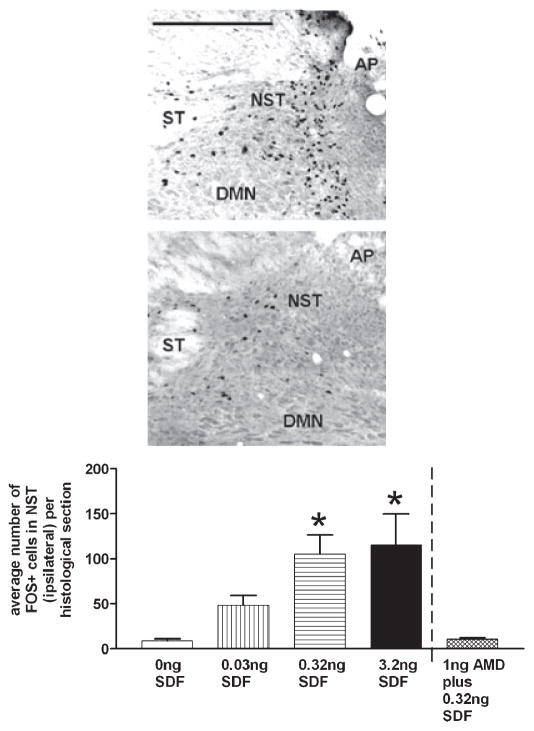

cFOS activation of neurons in the DVC by SDF-1 is dose dependent. Left panel: photomicrographs of cFOS-positive neurons in the NST and DMN in response to unilateral nanoinjections of either SDF-1 (40 nL containing 3.2 ng; top photo) or PBS (40 nL; bottom photo). AP, area postrema; DMN, dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus; NST, nucleus of the solitary tract; ST, solitary tract. Scale bar: 400 microns. Right panel: number of cFOS-activated neurons within the DVC at the level of the AP (i.e. rostro-caudal extent of the injection) were tabulated and averaged per histological section. The number of cFOS-activated neurons in the NST demonstrated a dose-dependent increase across the different doses of SDF-1. These differences were statistically significant when compared with the number of cFOS-activated neurons in the PBS-injected group [NST: ANOVA F4,18 = 4.7; P < 0.05; Dunnett’s post hoc comparisons against PBS control (‘0 ng SDF’); *P < 0.05]. The specificity of SDF-1-mediated CXCR4 activation (as shown by cFOS upregulation) was demonstrated by nanoinjection of the specific CXCR4 antagonist (AMD3100) into the DVC region immediately preceding nanoinjection of SDF-1. The number of cFOS-activated neurons in the NST was no different than that seen with nanoinjection of PBS into this region. AMD, AMD3100; SDF-1, stromal cell-derived factor-1.

SDF-1 evokes cFOS activation in the caudal, dorsal medulla

Direct nanoinjection of SDF-1 into the DVC produced a dose-dependent activation of cFOS in neurons. Figure 8 presents an example of cFOS activation in response to unilateral direct nanoinjection of SDF-1 (or PBS) into the DVC. The number and distribution of cFOS-activated neurons within the DVC at the level of the AP (i.e. the rostro-caudal extent of the injection) were tabulated and averaged per histological section. The vast majority of cFOS-activated neurons were found in the ipsilateral NST, though the NST contralateral (data not shown) and DMN ipsilateral to the site of injection also demonstrated dose-related increases in cFOS expression in response to SDF-stimulation. Figure 8 and Table 1 represent the number of cFOS-activated neurons found in the ipsilateral NST and DMN across the different doses. The number of NST and DMN neurons activated were statistically significant (NST: ANOVA F4,18 = 4.7; P < 0.05; DMN: ANOVA F4,18 = 7.0; P < 0.05; Dunnett’s post hoc comparisons against appropriate PBS control; *P < 0.05). The microinjection of the CXCR4 antagonist, AMD3100, into the DVC immediately preceding the microinjection of SDF-1 blocked the cFOS activation normally produced by SDF-1 (Table 1 and Fig. 8).

Table 1.

Average number of cFOS+ cells per histological section

| SDF-1 dose | 0 ng SDF-1 | 0.03 ng SDF-1 | 0.32 ng SDF-1 | 3.2 ng SDF-1 | 1 ng AMD3100 plus 0.32 ng SDF-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NST | 9.1 ± 2.1 | 31.0 ± 4.2 | 80.0 ± 30.0* | 120.0 ± 34.0* | 11.0 ± 1.3 |

| DMN | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 4.0 ± 1.4 | 6.7 ± 1.4* | 0.8 ± 0.2 |

Data are presented ± SEM. NST and DMN neurons, ipsilateral to injection site, demonstrated a dose-related increase in the number of cFOS-activated neurons with increasing doses of SDF-1 (Dunnett’s post hoc comparisons against appropriate PBS control;

P < 0.05). DMN, dorsal motor nucleus; NST, nucleus of the solitary tract; SDF-1, stromal cell-derived factor-1.

Effect of SDF-1 on vagally stimulated gastric motility

Gastric motility in anesthetized rats tends to be depressed. Given that we anticipated SDF-1 to suppress motility, we used a direct application of TRH (0.07 ng = 0.2 nmole) to the floor of the fourth ventricle to activate vagal efferent projections to the stomach. (TRH acts within the DVC by both activating vagal cholinergic efferent neurons in the DMN and inhibiting NST neurons that receive afferent input from the gut; McCann et al., 1988; Hermann & Rogers, 1995; Rogers et al., 2005.) The result is a dramatic increase in gastric motility (Fig. 9). Nanoinjection of SDF-1 into the DVC produced a significant, dose-dependent reduction in TRH-stimulated gastric motility (Fig. 9). MIs were determined for each animal; number and magnitude of contractions were tallied within 150-s epochs according to the Ormsbee and Bass MI equation (see above). Repeated-measures ANOVA for each of the four treatment groups yielded P-values < 0.0001. Dunnett’s post hoc tests, where the TRH-stimulated MI served as the basis of comparison, indicated that, unlike nanoinjection of PBS into the DVC area, all doses of SDF-1 tested suppressed the TRH-induced increase in gastric motility (*P < 0.05; Dunnett’s post hoc).

Fig. 9.

SDF-1 produces a significant, dose dependent inhibition of gastric motility. Upper panel: examples of raw polygraph motility records from extraluminal strain gages over time. Gastric motility in anesthetized rats tends to be depressed. Given that we anticipated SDF-1 to suppress motility, we used a direct application of TRH to the floor of the fourth ventricle to activate vagal efferent projections to the stomach (indicated at white arrow). Within 3 min, gastric motility is maximally stimulated. Nanoinjection of PBS (40 nL; indicated at black arrow, upper trace) into the DVC does not suppress this stimulated motility. In contrast, nanoinjection of SDF-1 (3.2 ng in 40 nL) into the DVC produced significant, dose-dependent reductions in TRH-stimulated gastric motility within 1 min of injection. Lower panel: MIs were determined for each animal; number and magnitude of contractions were tallied within 150-s epochs according to the Ormsbee and Bass MI equation (see Materials and methods). Repeated-measures ANOVA for each of the four treatment groups yielded P-values < 0.0001. Dunnett’s post hoc tests, where the TRH-stimulated MI served as the basis of comparison, indicated that, unlike nanoinjection of PBS into the DVC area, all doses of SDF-1 tested suppressed the TRH-induced increase in gastric motility (*P < 0.05; Dunnett’s post hoc). PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; SDF-1, stromal cell-derived factor-1; TRH, thyrotropin-releasing hormone.

Discussion

Our IHC studies show that the CXCR4 receptor is highly expressed in the NST and DMN, i.e. dorsal medullary areas known to be important to the regulation of GI function. The adjacent AP, a region known to initiate emesis, food aversion and nausea when activated (Blessing, 1997), also expresses CXCR4. Essentially every neuron in the NST and AP has the CXCR4 receptor. ChAT-ir neurons in the rostral and lateral DMN express the chemokine receptor, but TH- and NOS-phenotypes of DMN neurons do not. The subjacent hypoglossal nucleus (i.e. origin of XII cranial motor projections to the tongue) also contains the CXCR4 receptor on proximal dendrites. Additional IHC studies verify that gastric-projecting DMN neurons (labeled retrogradely via rhodamine-coated latex beads) specifically express CXCR4 receptors (see Fig. 6).

Direct injection of SDF-1 into the DVC causes a significant and dose-dependent elevation in cFOS expression in neurons of the NST and the DMN. Activation of NST and subsets of DMN neurons are associated with profound reductions in gastric motility and tone (Rogers et al., 2005). As predicted, direct injection of SDF-1 into the DVC caused an immediate decline in stimulated gastric motility and tone of the sort that has been associated with another pro-emetic cytokine, tumor necorsis factor-alpha (TNFα; Hermann & Rogers, 1995; Hermann et al., 2005b; Rogers et al., 2005). TNFα, like SDF-1, activates gastric reflex control circuits in the DVC, resulting in a significant reduction in gastric tone and motility (Hermann & Rogers, 1995; Hermann et al., 2005b; Rogers et al., 2005, 2006). Significant reductions in gastric function depress transit. These gastric effects are perceived as nausea and often herald emesis (Lang, 1990; Morrow et al., 2002). This gastric state is also associated with anorexia.

While the primary role of SDF-1 (also referred to as CXCL12, the natural agonist for the CXCR4 receptor) is essential for normal development of neurons and glia (Chalasani et al., 2003; Knaut et al., 2005; Lieberam et al., 2005), it is also released as a consequence of several neuropathological processes, especially neuroinfection and metastasis (Gabuzda & Wang, 2000; Lazarini et al., 2003; Elenkov et al., 2005; Lagman et al., 2005). Immunohistological studies of Banisadr et al. (2002, 2003) have shown that the CXCR4 receptor is constitutively expressed on astrocytes and microglia as well as neurons in different loci in the forebrain. The interaction between the HIV virus and the CXCR4 receptor (in the forebrain) as a portal of entry, and the critical role of SDF-1 / CXCR4 in maintaining glia metastasis provide support for hypotheses connecting activation of the CXCR4 receptor to dementia and movement disorders in acquired immune deficiency syndrome and brain metastasis (Banisadr et al., 2002, 2003). Thus, the results from our present study suggest that the gastric stasis, nausea and anorexia that occur during neuroinfection, neuroinflammation and metastasis could be caused, in part, by SDF-1 / CXCR4 interaction with visceral afferent and efferent control circuits in the dorsal medulla.

The cFOS and CXCR4-double IHC results suggest that this chemokine activates a broad spectrum of NST phenotypes, i.e. virtually all NST neurons express CXCR4-ir and included all three neuronal phenotypes examined (i.e. TH, NOS and GAD-67). The main physiological effects of NST activation in gastric vago-vagal reflexes are the inhibition of vagal motor neurons that normally signal increases in gastric motility and tone as well as the excitation of inhibitory vagal efferents [i.e. non-adrenergic non-cholinergic (NANC)] that are normally silent (Rogers et al., 2005). CXCR4-immunoreactivity on vagal motor neurons (see Figs 5 and 6) was concentrated on cells located in the rostro-lateral portion of the DMN (i.e. the location of NANC vagal motor neurons; Krowicki et al., 1999; Hermann et al., 2005a), suggesting that this chemokine may directly activate this inhibitory path to the stomach. This inhibition of gastric motility was demonstrated in our in vivo physiological studies (Fig. 8).

While we have successfully replicated the observation by Banisadr et al. (2002, 2003) of abundant CXCR4-ir on astrocytes in the cerebral cortex, our results demonstrated that astrocytes in the DVC clearly do not express this marker. The CXCR4 receptor has been implicated as an important regulator of blood–brain barrier function, and may be an especially important factor in regulating access of viral particles and immune cells to the neuropil (Wu et al., 2000; Kanmogne et al., 2007). It is interesting to note that the NST and the adjacent AP do not possess a functional blood–brain barrier (Gross et al., 1990; Broadwell & Sofroniew, 1993). Given that astrocytes are physiologically and morphologically responsible for the maintenance of the diffusion barrier in other parts of the brain, it is tempting to speculate that the lack of the CXCR4 receptor on these cell types is related to the lack of barrier function in this medullary circumventricular organ.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants DK52142, DK56373 and HD047643.

Abbreviations

- AP

area postrema

- ChAT

choline acetyl transferase

- DMN

dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus

- DVC

dorsal vagal complex

- GABA

γ-aminobutyric acid

- GAD

glutamic acid decarboxylase

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- GI

gastrointestinal

- IHC

immunohistochemical

- MI

motility index

- NANC

non-adrenergic non-cholinergic

- NeuN

neuron-specific nuclear antibody

- NF

neurofibrillary protein

- NOS

neuronal nitric oxide synthase

- NST

nucleus of the solitary tract

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- SDF-1

stromal cell-derived factor-1

- TH

tyrosine hydroxylase

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-alpha

- TRH

thyrotropin-releasing hormone

References

- Andrews PL, Davis CJ, Bingham S, Davidson HI, Hawthorn J, Maskell L. The abdominal visceral innervation and the emetic reflex: pathways, pharmacology, and plasticity. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1990;68:325–345. doi: 10.1139/y90-047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews PL, Horn CC. Signals for nausea and emesis: implications for models of upper gastrointestinal diseases. Auton Neurosci. 2006;125:100–115. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong DM, Manley L, Haycock JW, Hersh LB. Co-localization of choline acetyltransferase and tyrosine hydroxylase within neurons of the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus. J Chem Neuroanat. 1990;3:133–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banisadr G, Fontanges P, Haour F, Kitabgi P, Rostene W, Melik Parsadaniantz S. Neuroanatomical distribution of CXCR4 in adult rat brain and its localization in cholinergic and dopaminergic neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:1661–1671. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banisadr G, Skrzydelski D, Kitabgi P, Rostene W, Parsadaniantz SM. Highly regionalized distribution of stromal cell-derived factor- 1 / CXCL12 in adult rat brain: constitutive expression in cholinergic, dopaminergic and vasopressinergic neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:1593–1606. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthoud HR. Multiple neural systems controlling food intake and body weight. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2002;26:393–428. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(02)00014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blessing WW. The Lower Brainstem and Bodily Homeostasis. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1997. Eating and metabolism; pp. 323–372. [Google Scholar]

- Broadwell RD, Sofroniew MV. Serum proteins bypass the blood–brain fluid barriers for extracellular entry to the central nervous system. Exp Neurol. 1993;120:245–263. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1993.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buelke-Sam J, Holson JF, Bazare JJ, Young JF. Comparative stability of physiological parameters during sustained anesthesia in rats. Lab Anim Sci. 1978;28:157–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalasani SH, Sabelko KA, Sunshine MJ, Littman DR, Raper JA. A chemokine, SDF-1, reduces the effectiveness of multiple axonal repellents and is required for normal axon pathfinding. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1360–1371. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-04-01360.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuello AC, Priestley JV, Sofroniew MV. Immunocytochemistry and neurobiology. Q J Exp Physiol. 1983;68:545–578. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1983.sp002748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debus E, Weber K, Osborn M. Monoclonal antibodies specific for glial fibrillary acidic (GFA) protein and for each of the neurofilament triplet polypeptides. Differentiation. 1983;25:193–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1984.tb01355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elenkov IJ, Iezzoni DG, Daly A, Harris AG, Chrousos GP. Cytokine dysregulation, inflammation and well-being. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2005;12:255–269. doi: 10.1159/000087104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong AY, Stornetta RL, Foley CM, Potts JT. Immunohistochemical localization of GAD67-expressing neurons and processes in the rat brainstem: subregional distribution in the nucleus tractus solitarius. J Comp Neurol. 2005;493:274–290. doi: 10.1002/cne.20758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabuzda D, Wang J. Chemokine receptors and mechanisms of cell death in HIV neuropathogenesis. J Neurovirol. 2000;6 (Suppl 1):S24–S32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glabinski AR, O’Bryant S, Selmaj K, Ransohoff RM. CXC chemokine receptors expression during chronic relapsing experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;917:135–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill HJ, Kaplan JM. The neuroanatomical axis for control of energy balance. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2002;23:2–40. doi: 10.1006/frne.2001.0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross PM, Wall KM, Pang JJ, Shaver SW, Wainman DS. Microvascular specializations promoting rapid interstitial solute dispersion in nucleus tractus solitarius. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1990;259:R1131–R1138. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1990.259.6.R1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo JJ, Browning KN, Rogers RC, Travagli RA. Catecholaminergic neurons in rat dorsal motor nucleus of vagus project selectively to gastric corpus. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;280:G361–G367. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.280.3.G361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann GE, Travagli KA, Rogers RC. Esophageal-gastric relaxation reflex in rat: dual control of peripheral nitrergic and cholinergic transmission. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R1570–R1576. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00717.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann GE, Emch GS, Tovar CA, Rogers RC. c-Fos generation in the dorsal vagal complex after systemic endotoxin is not dependent on the vagus nerve. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001b;280:R289–R299. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.280.1.R289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann GE, Holmes GM, Rogers RC. TNF (alpha) modulation of visceral and spinal sensory processing. Curr Pharm Des. 2005b;11:1391–1409. doi: 10.2174/1381612053507828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann GE, Nasse JS, Rogers RC. Alpha-1 adrenergic input to solitary nucleus neurones: calcium oscillations, excitation and gastric reflex control. J Physiol. 2005a;562:553–568. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.076919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann G, Rogers RC. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha in the dorsal vagal complex suppresses gastric motility. Neuroimmunomodulation. 1995;2:74–81. doi: 10.1159/000096874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann GE, Rogers RC, Bresnahan JC, Beattie MS. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces cFOS and strongly potentiates glutamate-mediated cell death in the rat spinal cord. Neurobiol Dis. 2001a;8:590–599. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann GE, Tovar CA, Rogers RC. Induction of endogenous tumor necrosis factor-alpha: suppression of centrally stimulated gastric motility. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1999;276:R59–R68. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.1.R59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornbuckle K, Barnett JL. The diagnosis and work-up of the patient with gastroparesis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;30:117–124. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200003000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia M, Fuxe K, Goldstein M, Harfstrand A, Agnati LF, Coyle JT. Evidence for the existence of putative dopamine-, adrenaline- and noradrenaline-containing vagal motor neurons in the brainstem of the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1984;50:57–62. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(84)90462-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanmogne GD, Schall K, Leibhart J, Knipe B, Gendelman HE, Persidsky Y. HIV-1 gp120 compromises blood–brain barrier integrity and enhances monocyte migration across blood–brain barrier: implication for viral neuropathogenesis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:123–134. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaut H, Blader P, Strahle U, Schier AF. Assembly of trigeminal sensory ganglia by chemokine signaling. Neuron. 2005;47:653–666. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krowicki ZK, Sharkey KA, Serron SC, Nathan NA, Hornby PJ. Distribution of nitric oxide synthase in rat dorsal vagal complex and effects of microinjection of nitric oxide compounds upon gastric motor function. J Comp Neurol. 1997;377:49–69. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970106)377:1<49::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krowicki KZ, Sivarao VD, Abrahams PT, Hornby JP. Excitation of dorsal motor vagal neurons evokes non-nicotinic receptor-mediated gastric relaxation. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1999;77:83–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagman RL, Davis MP, LeGrand SB, Walsh D. Common symptoms in advanced cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85:237–255. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang IM. Digestive tract motor correlates of vomiting and nausea. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1990;68:242–253. doi: 10.1139/y90-038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarini F, Tham TN, Casanova P, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Dubois-Dalcq M. Role of the alpha-chemokine stromal cell-derived factor (SDF-1) in the developing and mature central nervous system. Glia. 2003;42:139–148. doi: 10.1002/glia.10139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Pleasure SJ. Morphogenesis of the dentate gyrus: what we are learning from mouse mutants. Dev Neurosci. 2005;27:93–99. doi: 10.1159/000085980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberam I, Agalliu D, Nagasawa T, Ericson J, Jessell TM. A Cxcl12-CXCR4 chemokine signaling pathway defines the initial trajectory of mammalian motor axons. Neuron. 2005;47:667–679. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M, Grove EA, Miller RJ. Abnormal development of the hippocampal dentate gyrus in mice lacking the CXCR4 chemokine receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:7090–7095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092013799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manier M, Mouchet P, Feuerstein C. Immunohistochemical evidence for the coexistence of cholinergic and catecholaminergic phenotypes in neurones of the vagal motor nucleus in the adult rat. Neurosci Lett. 1987;80:141–146. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(87)90643-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann MJ, Hermann GE, Rogers RC. Dorsal medullary serotonin and gastric motility: enhancement of effects by thyrotropin-releasing hormone. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1988;25:35–40. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(88)90005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AD. Central mechanisms of vomiting. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:39S–43S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow GR, Roscoe JA, Hickok JT, Andrews PL, Matteson S. Nausea and emesis: evidence for a biobehavioral perspective. Support Care Cancer. 2002;10:96–105. doi: 10.1007/s005200100294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris PJ, Charles IG, Scorer CA, Emson PC. Studies on the localization and expression of nitric oxide synthase using histochemical techniques. Histochem J. 1995;27:745–756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormsbee HS, 3rd, Bass P. Gastroduodenal motor gradients in the dog after pyloroplasty. Am J Physiol. 1976;230:389–397. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1976.230.2.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plata-Salaman CR. Central nervous system mechanisms contributing to the cachexia–anorexia syndrome. Nutrition. 2000;16:1009–1012. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(00)00413-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransohoff RM, Glabinski A, Tani M. Chemokines in immune-mediated inflammation of the central nervous system. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1996;7:35–46. doi: 10.1016/1359-6101(96)00003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaman L, Verbalis JG, Stricker EM, Hoffman GE. Distribution and neurochemical phenotypes of caudal medullary neurons activated to express cFos following peripheral administration of cholecystokinin. J Comp Neurol. 1993;338:475–490. doi: 10.1002/cne.903380402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers RC, Hermann GE. Dorsal medullary oxytocin, vasopressin, oxytocin antagonist, and TRH effects on gastric acid secretion and heart rate. Peptides. 1985;6:1143–1148. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(85)90441-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers RC, Hermann GE, Travagli RA. Brainstem control of gastric function. In: Johnson LR, editor. Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract. 4. Elsevier; San Diego: 2005. pp. 851–875. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers RC, Travagli RA, Hermann GE. Noradrenergic neurons in the rat solitary nucleus participate in the esophageal-gastric relaxation reflex. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;285:R479–R489. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00155.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers RC, Van Meter MJ, Hermann GE. Tumor necrosis factor potentiates central vagal afferent signaling by modulating ryanodine channels. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12642–12646. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3530-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schols D, Struyf S, Van Damme J, Este JA, Henson G, De Clercq E. Inhibition of T-tropic HIV strains by selective antagonization of the chemokine receptor CXCR4. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1383–1388. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.8.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayama K, Suzuki T, Miura M. The comparison of effects of various anesthetics on expression of Fos protein in the rat brain. Neurosci Lett. 1994;176:59–62. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90871-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf HK, Buslei R, Schmidt-Kastner R, Schmidt-Kastner PK, Pietsch T, Wiestler OD, Blumcke I. NeuN: a useful neuronal marker for diagnostic histopathology. J Histochem Cytochem. 1996;44:1167–1171. doi: 10.1177/44.10.8813082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu DT, Woodman SE, Weiss JM, McManus CM, D’Aversa TG, Hesselgesser J, Major EO, Nath A, Berman JW. Mechanisms of leukocyte trafficking into the CNS. J Neurovirol. 2000;6 (Suppl 1):S82–S85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng ZL, Rogers RC, Travagli RA. Selective gastric projections of nitric oxide synthase containing vagal brainstem neurones. Neuroscience. 1999;90:685–694. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00586-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]