Abstract

The use of chemoradiation therapy in laryngeal cancer has resulted in significant reconstructive challenges. Although reconstruction of salvage laryngectomy defects remains controversial, current literature supports aggressive management of these defects with vascularized tissue, even when there is sufficient pharyngeal tissue present for primary closure. Significant advancement in reconstructive techniques has permitted improved outcomes in patients with advanced disease who require total laryngopharyngectomy or total laryngoglossectomy. Use of enteric and fasciocutaneous flaps result in good patient outcomes. Finally, wound complication rates after salvage surgery approach 60% depending on comorbid conditions such as cardiac insufficiency, hypothyroidism, or extent of previous treatment. Neck dehiscence, great vessel exposure, fistula formation, or cervical skin necrosis results in complex wounds that can often be treated initially with negative pressure dressings followed by definitive reconstruction. The timing of repair and approach to the vessel-depleted neck also present challenges in this patient population. Currently, there is significant institutional bias in the management of the patient with postchemoradiation salvage laryngectomy. Future prospective multi-institutional studies are certainly needed to more clearly define optimal treatment of these difficult patients.

Keywords: salvage surgery, laryngectomy, wound complications, head and neck cancer, free flap

Primary chemoradiation therapy for advanced laryngeal cancer has resulted in larynx-preservation rates of up to 64% of surviving patients thereby achieving cure rates similar to that of total laryngectomy followed by radiation therapy.1 Successful surgical salvage of patients with persistent or recurrent cancer after tissue damage from chemoradiation therapy has therefore become an evolving aspect in the management of advanced laryngeal cancer.

The damaging effects of radiation therapy have been well established in the literature, and the addition of chemotherapy to radiation has been shown to have profound additive effects.2,3 Several studies have demonstrated high rates of wound complications associated with salvage laryngectomy after chemoradiation. Major wound complications occurred in 61% of patients who underwent surgery after organ-preservation therapy conducted by the Veteran’s Administration Laryngeal Cancer Study Group.4 Data from the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 91-11 study found an overall wound complication rate between 52% and 59% with a pharyngocutaneous fistula rate of 15% to 30%.5 Others report 45% incidence of local wound complications and 32% rate of pharyngocutaneous fistulas after chemoradiation therapy. In this study, the authors report that primary chemoradiation therapy was an independent predictor of postlaryngectomy complications.6

Salvage Laryngectomy Defects

Laryngectomy defects can generally be classified into 3 general categories: (1) sufficient mucosa to close primarily, (2) mucosa present but insufficient to close (requiring patch reconstruction), and (3) total laryngopharyngectomy where no mucosal strip of tissue is present and therefore requires a tubed reconstruction. The section immediately below addresses the first and second scenarios, whereas the section on total laryngopharyngectomy addresses the third scenario.

Salvage Laryngectomy with Sufficient Mucosa

After total laryngectomy with or without partial pharyngectomy, the remaining pharyngeal defect can be repaired either by primary closure or with additional tissue depending on the amount of pharyngeal tissue remnant available. Traditionally, approximately 3 cm of stretched non-radiated pharyngeal mucosa is sufficient for primary closure after laryngectomy. The relaxed and stretched widths of the pharyngeal remnant can be measured after removal of the laryngeal specimen. It has been demonstrated that the narrowest width of the pharyngeal remnant is 1.5 cm relaxed (or 2.5 cm stretched) in the absence of tumor recurrence or radiation is sufficient both for primary closure of the pharynx and in restoring swallowing function.7 Several reports support the use of free vascularized tissue reinforcement of the primary pharyngeal closure in salvage laryngectomy after failed chemoradiation therapy to prevent major wound complications but did not significantly impact overall fistula rate.8 Use of a “patch” radial forearm free flap in patients with sufficient pharyngeal mucosa has been advocated in patients undergoing salvage surgery. Free flap reconstruction had a lower rate of fistula (18%) compared with the primary closure group (50%). A lower rate of stricture formation (18% vs 25%) and feeding tube dependence (23% vs 45%) was also observed in the free flap reconstruction group compared with the primary closure group.9

Use of the pectoralis major myocutaneous flap as the optimal reconstruction for salvage laryngectomy with sufficient mucosa for closure remains controversial. Some authors have found that when a pectoralis myofascial flap reinforcement of the closure is performed after salvage laryngectomy, the fistula rate is significantly reduced compared to primary closure.10 However, others have found that in a much larger cohort, patients undergoing salvage laryngectomy with primary closure develop pharyngocutaneous fistulas (24%) at a similar rate compared to reconstruction using the pectoralis major flap (27%).11

Salvage Laryngectomy without Sufficient Mucosa

In the setting of insufficient pharyngeal mucosa for closure, vascularized tissue is needed, but the choice of donor site for reconstructive tissue has been controversial. The pectoralis major myocutaneous flap has served as a popular choice and is certainly a reliable reconstruction in patients with significant comorbidities. A comparison between the pectoralis major myocutaneous flap and free tissue flaps in oral and oropharyngeal reconstruction showed no statistically significant differences (p > .05) other than a longer operative time for free flap reconstruction when comparing costs and morbidity.12 In cases of total laryngectomy, the pectoralis major myocutaneous flap can be directly sutured to the pharyngeal and esophageal stumps and the prevertebral fascia, which eventually represented the posterior wall of the neohypopharynx. In cases of partial pharyngolaryngectomy, the pectoralis flap can be sutured to the posterior wall of the neohypopharynx and consist of a residual strip of pharyngeal mucosa. Although microvascular free flaps are reliable, the pectoralis major myocutaneous flap can be applied to hypopharyngeal reconstruction with expediency and a low complication rate.13 It is unusual, however, for studies advocating pectoralis flaps to address donor site morbidity. In our experience, the associated donor site morbidity of shoulder dysfunction, pulmonary comorbidity, and cosmesis is less tolerated than the free tissue donor sites of the radial forearm or anterolateral thigh free flap. Therefore, we favor free tissue reconstruction for pharyngeal closure in the setting of insufficient pharyngeal mucosa. Furthermore, this reserves the pectoralis flap for subsequent repair of salvage surgery defects or other management of postoperative wound complications.

The selection of free tissue donor site for pharyngeal reconstruction has also remained controversial. The most common donor sites include the radial forearm, anterolateral thigh, and rectus flap for partial pharyngeal reconstruction. A study of 19 patients who were randomized into either anterolateral thigh flaps or radial forearm flaps for pharyngeal reconstruction, there was a significant (p = .04) increase in reconstructive complications in the anterolateral thigh group, including esophageal stenosis and pharyngeal fistulas. There was no reported significant difference in donor-site complications.14

In the setting of patients with sufficient pharyngeal mucosa in salvage laryngectomy after chemoradiation therapy, we have advocated the use of free vascularized tissue. Although the patient’s body habitus influences donor site selection, we have favored the use of the radial forearm free flap. In patients with significant comorbidities, it may be expedient to use the pectoralis major myocutaneous flap due to its reliability and ease. Although it is often wiser to leave the pectoralis major flap as an alternative if any additional reconstructive procedures are needed.

Total Laryngopharyngectomy

Classically, the reconstruction of total laryngopharyngectomy defects is considered in a different light when compared to the total laryngectomy where a strip of posterior pharyngeal wall mucosa has been left. Historically, total laryngopharyngectomy defects were very difficult to reconstruct. Local tissue flaps, such as the Wookey flap, require multiple surgical stages and was fraught with patient morbidity and extended and prolonged hospital stays. The advent of pedicle flaps demonstrated that the pectoralis major myocutaneous flap could be tubed or sutured to the deep neck fascia. Although this improved wound healing and allowed patients to be discharged earlier with decreased morbidity, it often times resulted in fistulas or strictures.

Reconstruction of the total laryngopharyngectomy defect can be divided into tubed skin or an enteric free flap. Initially, total laryngopharyngectomy defects were reconstructed using jejunal free flaps. The ability to use a tubed enteric flap seemed intuitive and relatively straightforward, and the success rates were acceptable. The advent and common usage of the radial forearm flap began to see the use of a tubed radial forearm flap instead of a jejunal flap. Although there are many pros and cons to each donor site, it seems that institutions and surgeons developed their own personal preferences. Consequently, the discussion of this topic will be approached from an outcome and morbidity perspective comparing these 2 major reconstructive modalities.

The morbidity of a jejunal or enteric free flap is that the abdominal cavity must be opened in order for the jejunum to be harvested. Although there have been single institutional reports of endoscopic harvest of a jejunum, this is not widely performed. Jejunal flap harvest is performed by a general surgeon and there is relatively minor morbidity and long-term abdominal issues reported. The most common issue with harvesting of a jejunal free flap is the increase in length of stay secondary to the patients’ recovery of abdominal function. The comparison of length of stay between 2 institutions demonstrated that the average was approximately 13 days for patients with enteric flaps as opposed to 9 days for patients with tubed skin flaps; which has significant cost implications. Intra-abdominal complications are rare and are usually reported anecdotally with an incidence of less than 5% in most series where numbers can be generated to yield statistics.15,16 Harvesting of an enteric flap usually does not involve any increase in blood loss or extra surgical time. However, marked increase in fluids are required during the harvest, although there has never been adequate documentation that these fluid shifts are detrimental to flap survival. The short-term and long-term donor morbidity associated with harvesting of a fascial flap from the forearm has been well documented in the literature.17,18 The issues are mainly of a wound healing nature with loss of parts of the skin graft and occasional dressing changes and wound care issues that may last over a month or 2. Studies from multiple institutions demonstrate a fistula rate of approximately 3% to 14%.19,20

Most fistulas in the enteric flaps would seem to arise from the superior anastomosis. The lower anastomosis is more easily closed in a watertight fashion compared to the superior anastomosis because of the oropharyngeal circumference. Incising the jejunum may improve results, but the tongue base is not as malleable as the esophagus and suturing at the lateral borders may break down. It is oftentimes easier to adapt the large oropharyngeal circumferential opening and a small cervical esophageal opening by tubing a fascial flap. Whereas a small leak from a visceral flap or rectus flap that has adequate tissue coverage may not manifest as a fistula, a leak from a tubed radial forearm flap will ultimately show itself through a fistula formation in the neck.

The anterolateral thigh flap is a fascial cutaneous flap that has become much more popular in recent years. A small number of series have described the use of this flap for reconstruction of total laryngopharyngectomy defects, but the forearm has been found to be superior. In many populations, the size of the fat and subcutaneous tissue precludes use of this flap as it becomes difficult to mold it into a 3-dimensional shape, much like the pectoralis muscle myocutaneous flap was difficult to form into a tube. In certain patient populations, or in highly selected patients where the subcutaneous tissue is not very thick, this flap can also be folded into a tube. The amount of skin that can be harvested is greater than that with a radial forearm, and the added layer of fascia or taking a strip of the rectus femoris muscle allows for a second layer, which can help cover the anastomotic or a long suture line. Molding it in 3-dimensionally because of the subcutaneous fat is the issue, although the flap can be rotated in a spiral closure to create a tube.

Functional Outcomes in Total Laryngopharyngectomy Defects

Strictures in tubed flap reconstructions are common at the lower esophageal anastomosis. The oro-pharyngeal site tends to fistulize more, but once it heals, stricture rates seem to be low because of the large size of the oropharyngeal inlet. The upper esophagus that is used for anastomosis has most often seen previous chemoradiation, and thus, is inclined to form more scar tissue and contribute to stricture formation. Stricture formation for tubed skin flaps is reported in up to 50% to 60% of patients, whereas stricture formation in jejunal flaps occurs in up to 20% of patients.15,19,21,22 Most studies are retrospective single-institution reports with small patient numbers, which makes it hard to compare from one institution to another because of the multiple criteria for surgery, surgical preferences, and pretreatments. Most patients have their strictures treated with serial dilations, therefore, surgical intervention is rarely required.

It is important to differentiate a patient’s dependency on a gastrostomy tube based on inadequate oral intake that is caused by a stricture as opposed to swallowing dysfunction from the overall patient condition or their prior treatment. In our experience, patients without anatomic obstruction can remain gastrostomy dependent because of pre-existing postchemoradiation treatment swallowing dysfunction. Notwithstanding this, approximately a quarter of patients with tubed skin flaps will ultimately require a gastrostomy tube for complete enteral support. In a jejunal free flap, this is usually reported up to 13%.16,23 Again, comparison from a statistical perspective is difficult due to the selection criteria and the small numbers from single institutions. However, with intensification of chemoradiation, patients demonstrate no anatomic obstruction but have diffuse swallowing disorders of the oral cavity and cervical remnants of the cervical esophagus secondary to their prior treatment. Tracheoesophageal puncture can be performed in patients that undergo enteric or fasciocutaneous flap reconstructions. The institutions that have dedicated speech language pathologists and a particular interest in language rehabilitation have demonstrated excellent results with up to half of these patients achieving some form of speech. Compared to radial forearm reconstruction, results in a jejunal flap is wet, moist, and is not as understandable as that with a radial forearm flap. Results comparing the 2 flaps are oftentimes difficult because the institution and surgical preference will preclude use of the comparison flap.19,23,24

In summary, whether one chooses a fasciocutaneous flap or an enteric flap depends on surgical judgment, expected donor site morbidity and, to some extent, the institutional experience such as nursing care. Enteric flaps are associated with longer length of stay; whereas fasciocutaneous tubed flaps have wound care issues due to fistulas. Ultimately, patients with both types of reconstruction tend to heal over time and a significant number are ultimately free of gastrostomy dependence.

Total Glossectomy with Laryngectomy

Very extensive tumors, or less commonly, synchronous primary cancers, may necessitate total glossectomy concurrently with laryngectomy. A laryngectomy may also be performed with a total glossectomy when recurrent aspiration is felt to be unavoidable. In cases of total glossectomy with laryngectomy, the functions of both deglutition and phonation are lost; however, aspiration is not a concern. The main goal of reconstruction is to create a conduit to the esophagus that relies primarily on gravity for transit of food and liquid.

Laryngoglossectomy defects can be reconstructed in subunits: the oral defect separately, with a pedicled or free flap, and proceed with pharyngeal reconstruction by 1 of the methods described previously. In most cases, however, it is usually desirable to perform reconstruction of the entire defect with a single flap. The challenge of reconstruction with a single flap is that the flap must be both long enough to extend from the lingual surface of the mandible to the cervical esophagus and wide enough to span the entire floor of the mouth and reach the lateral oropharyngeal walls on each side.

The jejunal free flap has been modified to achieve the requisite width to span the floor of the mouth and reach the lateral oropharyngeal walls by splitting the small intestine along its antimesenteric border then folding and suturing it either into a “J” or “S” shape to effectively double or triple the width of the flap, respectively.25,26 An alternative to the jejunal free flap is the ileocolic free flap.27 The ileocolic free flap is mucosally lined, like the jejunal free flap, but has a much larger diameter so that folding and additional suture lines are unnecessary to achieve the required width. The advantages of the modified jejunal and ileocolic free flaps are that they are lubricated with mucous secretions, have good caliber pedicle blood vessels, and the length of tissue available is ample. On the other hand, longer length of hospital stay is associated with an enteric flap harvest, as noted above.

Another alternative is the use of fasciocutaneous or myocutaneous free flaps, such as the rectus abdominis myocutaneous and anterolateral thigh (ALT) free flaps (Figure 1).28 The flap, which needs to be about 10 cm wide, can be used to line the floor of the mouth and used as a patch for partial pharyngectomy defects or tubed to reconstruct circumferential pharyngeal defects. In patients with adequate skin laxity, the donor-site defect can be closed primarily. It is not uncommon that these advanced-stage malignancies will require resection of additional structures such as a portion of the mandible (as shown in Figure 1) or cervical skin. As previously mentioned, the advantages of using cutaneous and myocutaneous free flaps are that a laparotomy and intestinal anastomosis are avoided and the neck vessels can be better covered by these bulky flaps, particularly when a muscle component is included, and that the flap can sometimes be designed to simultaneously reconstruct anterior neck skin defects (see below).

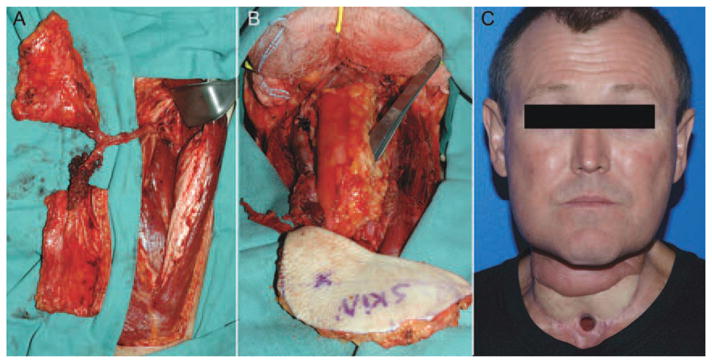

FIGURE 1.

(A) A surgical defect after a total glossectomy, laryngopharyngectomy, and segmental mandibulectomy. (B) The tongue and pharynx were replaced with an anterolateral thigh free flap that was tubed inferiorly. (C) Postoperative result. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Cutaneous Defects

A more common problem than the need to reconstruct both a glossectomy and laryngectomy defect is when the anterior neck skin must be replaced along with repairing the pharynx. In addition to when skin is resected because it is involved with or very close to the anterior margin of the tumor, previously irradiated neck skin tends to contract after skin flap elevation and may be at high risk for wound healing problems if closed under tension (Figure 2). Suture lines may be especially tight along the tracheal stoma when a distal tracheal resection has been performed. In addition to potential exposure of the major neck vessels, a wound dehiscence in the region of the tracheal stoma or pharyngeal closure can result in significant further morbidity.

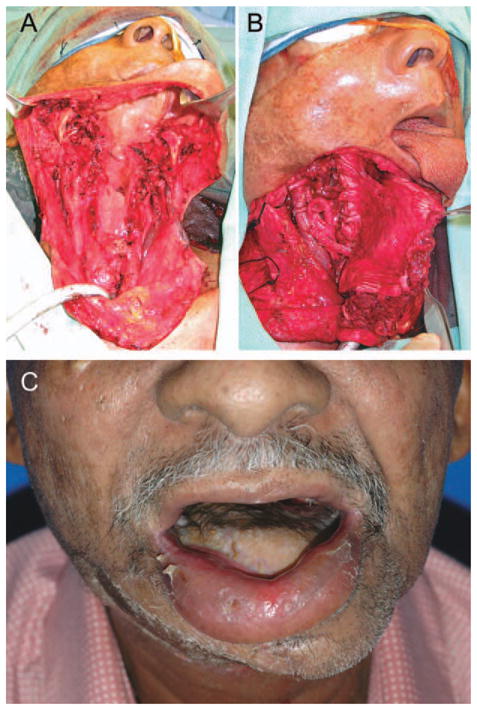

FIGURE 2.

Reconstruction of a circumferential hypopharyngeal defect and cutaneous defect in a patient undergoing salvage laryngopharyngectomy for recurrent laryngeal cancer. (A) An anterolateral thigh free flap was harvested with two skin paddles based on independent perforators. One skin paddle was used to reconstruct the pharynx and the other was used to reconstruct the anterior neck skin above the stoma (B); and postoperative result (C). [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Reconstruction of the anterior neck skin often requires a second flap; another free flap or a pedicled flap. The pectoralis major myocutaneous flap or muscle flap covered by a skin graft is frequently used to reconstruct the peristomal neck skin. This flap is well vascularized and easily reaches the anterior neck. Unilateral or bilateral deltopectoral flaps can also be used for this application.29 The deltopectoral flap is based on 3 to 4 internal mammary perforating blood vessels and is very reliable when its length is not extended beyond the deltopectoral groove. The advantage of the deltopectoral flaps is that they are less bulky and, therefore, have fewer problems in the immediate postoperative period with occluding the stomal airway than pectoralis major myocutaneous flaps.

An elegant solution is to use a single flap to reconstruct both the pharynx and the anterior neck skin. The ALT or rectus free flap can often be designed with 2 skin paddles based on independent cutaneous perforating blood vessels that join together proximally within the main vascular pedicle, thus requiring only a single set of arterial and venous anastomoses to complete the reconstruction.30 When more than 1 perforator is not available, the vastus lateralis muscle can be included with the ALT free flap and skin grafted to reconstruct the neck skin defect. Alternately, the ALT free flap or other fasciocutaneous free flaps can be partially de-epithelialized and a portion of the skin paddle can be used to reconstruct the neck skin defect.31

Complications in Patients with Salvage Laryngectomies

Wound dehiscence after laryngectomy often begins a cascade of problems that are often as difficult to predict as they are to manage. The absence of large randomized trials evaluating pharyngeal wound complications makes scientific statements about this patient population very difficult, if not impossible. However, enough retrospective data has accumulated from patients undergoing laryngectomy to identify factors that contribute to wound healing complications and their incidence. Factors that contribute to wound breakdown have been established and can help guide preoperative management and predict surgical outcome. Unfortunately, tissue quality varies significantly in patients who have undergone medical management as normal tissues respond differently to chemotherapy and radiation. When postlaryngectomy wound complications do occur, there are varieties of management strategies that can be applied.

Preoperative Predictors

Poor wound healing after laryngectomy manifests most commonly as cutaneous or mucosal epithelial edge dehiscence. Pharyngocutaneous fistulas have been reported to occur in approximately 20% to 50% of patients after laryngectomy, with higher rates associated with previous radiation therapy.19,32 Aggressive perioperative management of patients at risk for complications requires a clear understanding of conditions that predispose epithelial dehiscence and subsequent fistula formation. Risk factors identified for fistulas include a low postoperative hemoglobin level (less than 12.5 grams/dL), pre-operative radiotherapy, hypothyroidism, and concurrent neck dissection.33 Radiotherapy typically triples the risk of a postoperative fistula and has been well established as an independent risk factor in partial and total laryngectomy wound complications.34–36 Higher rates of complications are often reported with the addition of chemotherapy.37 Effects of epidermal growth factor targeted therapy on wound complications remains unknown.

Patients undergoing neck dissection at the time of laryngectomy have been found by us and others to have an increased risk of fistulas.33,38 In fact, others have reported that cervical lymph node metastasis correlates with fistula formation,39 which may simply reflect the fact that a neck dissection was performed in those patients. Cervical lymphatic dissections likely promote fistula formation because they require large incisions that devascularize tissues and create significant dead space or potential planes for fluid to collect.

Hypothyroidism is known to increase wound complications and is common in patients with head and neck cancer. Characteristics most associated with hypothyroidism include female sex, preoperative radiotherapy, or cervical metastasis.40 Postoperatively, almost 50% of patients will become hypothyroid after laryngectomy with most cases presenting in the first 14 months.41 Importantly, this study found patients with euthyroid who developed a postoperative fistula are subsequently at an increased risk for hypothyroidism. As a result, thyroid-stimulating hormone should be assessed in salvage laryngectomy cases frequently during the first 18 months after surgery because normal preoperative levels may not predict postoperative levels.

Although medical comorbidities are reported to impede wound healing, the literature does not consistently identify individual conditions, which is likely a result of their coexistence. Medical factors such as diabetes, chronic pulmonary disease, and congestive heart failure have been shown to correlate with post-laryngectomy fistula formation.33,42,43 Interestingly, the development of pharyngocutaneous fistulas is more commonly associated with congestive heart failure than diabetes.34,42

Management of Postlaryngectomy Fistulas

Management of pharyngocutaneous fistulas that occur after surgery, especially in a salvage case, remains very challenging. If vascularized tissue is introduced into the salvage laryngectomy wound at the time of closure, the fistula formation rate is generally between 15% and 20%, but between 20% and 50% with primary closure.19,20,32,44–46 Importantly, fistulas will usually heal spontaneously in the presence of vascularized reconstruction with conservative management over a period of 2 to 3 months.19,32 Reconstruction of fistulas after salvage laryngectomy is complicated by several factors: the paucity of vessels within the neck for flap reconstruction, limited mobility of the neck, and absence of the ability to close the neck primarily due to poor quality of cervical skin.47 Management of this patient population is not well published and varies significantly between surgeons.

Fistula formation after laryngectomy can result in a safe or unsafe wound. Pharyngeal secretions washing across an irradiated and/or skeletonized carotid sheath after neck dissection put these vessels at high risk of rupture and require prolonged observation or surgical management. Failure of granulation tissue to be seen in the wound or progressive necrosis usually requires placement of vascularized tissue between the secretions and the vessels at risk. The pectoralis myofascial flap can be raised and sutured over the carotid in such a way as to let the secretions drain out over the pectoralis flap. Attempting to close both the fistula and cover the carotid artery usually fails to do both. Conversion to a safe wound allows for patient discharge from the hospital with a period of conservative management with subsequent surgical repair if necessary. For carotid coverage, use of the pectoral major myofascial flap is favored because it is expedient and vessels for microvascular anastomosis do not need to be exposed in a contaminated field. If a herald bleed of the carotid system occurs, interventional radiology can be requested to stent the affected vessel. Subsequent exposure of the stent can occur over time in heavily pretreated patients and will require procedures that are more aggressive. Hyperbaric oxygen can be used as an adjuvant therapy to improve soft tissue healing and has become more easily accessible to patients.48,49 Although use of hyperbaric oxygen remains controversial in patients with cancer, the data does not suggest that it promotes short-term growth of cancer.50,51

Pharyngocutaneous fistulas or the dehiscence of cervical skin after total laryngectomy without vessel exposure can be managed conservatively using dressing sponges in saline or antibacterial solutions. Alternatively, negative pressure dressings can be used as primary management or as an adjuvant to surgical procedures.52–54 Compared to conventional dressings, negative pressure dressings promote wound contraction, rapid formation of granulation tissue,55 and limit exposure of the tissue to direct contact with pharyngocutaneous secretions. Complete fistula closure can be obtained in 1 to 2 weeks using the system.53 However, the negative pressure dressing cannot be used in the setting of necrotic tissue; instead traditional wet to dry dressings should be used. The most significant disadvantage of the negative pressure dressings is the cost (several hundred dollars per day)55 and the difficulty of holding suction around the tracheostomy or stoma.

The difficulty of achieving negative pressure around the tracheostoma can be managed in the operative setting. The wound can be aggressively debrided and then a large (8.0 or 8.5) endotracheal tube (with the balloon air cannula skeletonized to reduce the length) can be placed in the stoma and sutured into place (Figure 3). The negative pressure dressing can then be placed around the endotracheal tube. The negative pressure dressing, if the vacuum seal can be effectively maintained, can be changed biweekly or weekly. These dressings have been safely used to promote granulation tissue over the carotid artery or internal jugular vein. Patients who develop a fistula often stay in the hospital for approximately 2 weeks as the defect matures to a safe wound, during this time, aggressive management with negative dressings is ideal.32

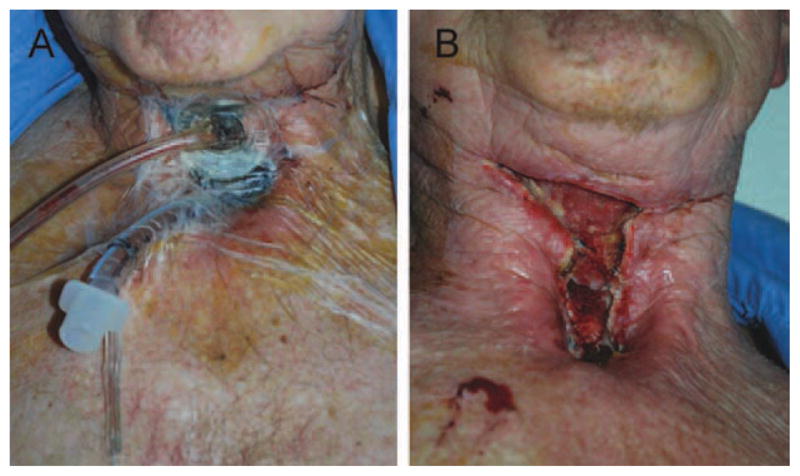

FIGURE 3.

Use of negative pressure dressing to manage a wound dehiscence after narrow field salvage laryngectomy. (A) A seal can be achieved by insertion of an 8.0 or 8.5 endotra-cheal tube into the tracheostoma and the pilot balloon cannula skeletonized to decrease the dead space within the endotra-cheal tube. After removal of the negative pressure dressing (5 days). [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Surgical closure of pharyngocutaneous fistulas should be performed after failure of conservative measures and medical comorbidities have been optimized, especially thyroid function and failure of conservative management. There is usually insufficient cervical skin to allow for primary closure of the cervical skin and a plan should be in place for external neck coverage. Some authors have suggested use of a dual paddle anterolateral thigh flap,47 alternatively a 2-flap solution including a radial forearm flap for tubed or patch reconstruction followed by a pectoral myofascial flap for external neck coverage. Use of external carotid system for microvascular anastomosis should be avoided because dissection of the external carotid system exposes the vessels to a potential fistula and may result in a stretch injury to the 12th nerve. Use of the transverse cervical vessels or internal mammary vessels is preferable in this setting (see below).

Judicious use of aggressive surgical intervention is critical during the prolonged hospital course associated with complex head and neck wounds. Immediate fistula repair in a wound without vessel exposure is appropriate in cases where frequent stomal contamination occurs; however, if pharyngeal secretions are in communication with major vascular structures, management should focus on creating a safe wound.

Recipient Vessel Selection in Salvage Surgery or Fistula Repair

In most cases of previously untreated disease, recipient blood vessels of adequate length, caliber, and flow for microvascular anastomosis are readily available. Most surgeons prefer to perform end-to-end anastomoses to branches of the external carotid artery, such as the facial or superior thyroid arteries, and branches of the internal jugular vein when these vessels are available. End-to-side anastomoses into the external carotid artery and/or internal jugular vein are also reasonable options. The external jugular vein is also frequently used as a recipient vein, although some series have found higher rates of thrombosis, possibly due to surgical trauma during neck dissection, low flow, and susceptibility to external compression due to its superficial location.56 However, in cases of prior irradiation and/or neck dissection, adequate recipient blood vessels may be ligated or nonpatent due to thrombosis.57,58 In other cases, extensive scar tissue formation may render dissection of the carotid and jugular vessels so perilous due to the risk of irreparable rupture, that dissection is best avoided.

The transverse cervical artery and vein are excellent alternatives to the external carotid artery and internal/external jugular vein systems. These vessels are usually preserved during neck dissections. The transverse cervical artery arises medially in the neck from the thyrocervical trunk, or occasionally from the subclavian artery directly. The transverse cervical vein drains into the external jugular vein or the subclavian vein. The omohyoid muscle is a surgical landmark for the transverse cervical artery and vein, which are deep to the muscle within the loose supraclavicular fatty tissue.59

The cephalic vein can also be an excellent source of venous drainage in head and neck microvascular surgery. Advantages of the cephalic vein are that it provides a long pedicle, lies outside the zone of radiation or prior surgery, and is associated with a generous diameter for microvascular anastomosis.60 The proximal cephalic vein is located in the deltopectoral groove and traced is distally adjacent to the lateral bicipital groove.

The use of internal mammary vessels for head and neck surgery has not commonly been reported but is well known in breast reconstruction with autologous free tissue transfer.61 The internal mammary vessels are usually located by removal of the second or third costal cartilage after division of the overlying pectoralis muscle (Figure 4). Inferior to the third rib, the caliber of the vein diminishes and is usually less than 1.5 mm.

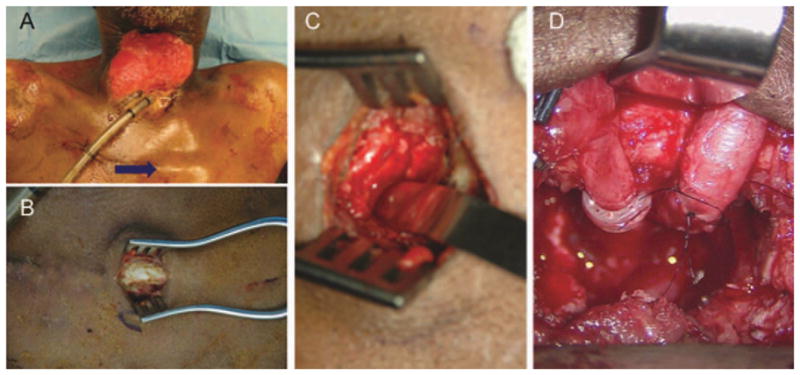

FIGURE 4.

Use of internal mammary vessels in the vessel depleted neck. At the Angle of Louis (blue arrow) (A), the second rib can be skeletonized (B), and removed (C). After microvascular anastomosis (D). [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

The thoracoacromial artery and vein have also been described as a potential source for recipient vessels in head and neck reconstruction.62,63 The thoracoacromial artery arises from the axillary artery and divides into acromial, deltoid, clavicular, and pectoral branches. Use of the pectoral branch of the thoracoacromial trunk for end-to-end anastomoses obviously prevents use of the pedicle pectoralis major muscle or myocutaneous flap as a secondary flap for reconstruction. However, in cases where the pectoralis major muscle flap has already been transferred and adequate healing has taken place, division and use of the pectoral branches, which remain well preserved within the perivascular fat pad, as recipient vessels has been reported.63

Acknowledgments

This review is a product of the American Head and Neck Society Reconstructive Committee.

References

- 1.The Department of Veterans Affairs Laryngeal Cancer Study Group. Induction chemotherapy plus radiation compared with surgery plus radiation in patients with advanced laryngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1685–1690. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199106133242402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hom DB, Adams GL, Monyak D. Irradiated soft tissue and its management. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1995;28:1003–1019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore MJ. The effect of radiation on connective tissue. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1984;17:389–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sassler AM, Esclamado RM, Wolf GT. Surgery after organ preservation therapy. Analysis of wound complication. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;121:162–165. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1995.01890020024006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weber RS, Berkey BA, Forastiere A, et al. Outcome of salvage total laryngectomy following organ preservation therapy. The Radiation Therapy Oncology Group trial 91–11. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:44–49. doi: 10.1001/archotol.129.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ganly I, Patel S, Matsuo J, et al. Postoperative complications of salvage total laryngectomy. Cancer. 2005;103:2073–2081. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hui Y, Wei WI, Yuen PW, Lam LK, Ho WK. Primary closure of pharyngeal remnant after total laryngectomy and partial pharyngectomy: how much residual mucosa is sufficient? Laryngoscope. 1996;106:490–494. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199604000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fung K, Teknos TN, Vandenberg CD, et al. Prevention of wound complications following salvage laryngectomy using free vascularized tissue. Head Neck. 2007;29:425–430. doi: 10.1002/hed.20492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Withrow KP, Rosenthal EL, Gourin CG, et al. Free tissue transfer to manage salvage laryngectomy defects after organ preservation failure. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:781–784. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e3180332e39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel UA, Keni SP. Pectoralis myofascial flap during salvage laryngectomy prevents pharyngocutaneous fistula. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;141:190–195. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gil Z, Gupta A, Kummer B, et al. The role of pectoralis major muscle flap in salvage total laryngectomy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;135:1019–1023. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2009.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smeele LE, Goldstein D, Tsai V, et al. Morbidity and cost differences between free flap reconstruction and pedicled flap reconstruction in oral and oropharyngeal cancer: matched control study. J Otolaryngol. 2006;35:102–107. doi: 10.2310/7070.2005.5001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spriano G, Pellini R, Roselli R. Pectoralis major myocutaneous flap for hypopharyngeal reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:1408–1413. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000029350.61515.39. discussion 1414–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrissey AT, O’Connell DA, Garg S, Seikaly H, Harris JR. Radial forearm versus anterolateral thigh free flaps for laryngopharyngectomy defects: prospective, randomized trial. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;39:448–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ayshford CA, Walsh RM, Watkinson JC. Reconstructive techniques currently used following resection of hypopharyngeal carcinoma. J Laryngol Otol. 1999;113:145–148. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100143403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Disa JJ, Pusic AL, Hidalgo DA, Cordeiro PG. Microvascular reconstruction of the hypopharynx: defect classification, treatment algorithm, and functional outcome based on 165 consecutive cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:652–660. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000041987.53831.23. discussion 661–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bardsley AF, Soutar DS, Elliot D, Batchelor AG. Reducing morbidity in the radial forearm flap donor site. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;86:287–292. discussion 293–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenthal E, Carroll W, Dobbs M, Scott Magnuson J, Wax M, Peters G. Simplifying head and neck microvascular reconstruction. Head Neck. 2004;26:930–936. doi: 10.1002/hed.20076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Withrow KP, Rosenthal EL, Gourin CG, et al. Free tissue transfer to manage salvage laryngectomy defects after organ preservation failure. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:781–784. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e3180332e39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teknos TN, Myers LL, Bradford CR, Chepeha DB. Free tissue reconstruction of the hypopharynx after organ preservation therapy: analysis of wound complications. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:1192–1196. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200107000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salamoun W, Swartz WM, Johnson JT, et al. Free jejunal transfer for reconstruction of the laryngopharynx. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1987;96:149–150. doi: 10.1177/019459988709600206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scharpf J, Esclamado RM. Analysis of recurrence and survival after hypopharyngeal ablative surgery with radial forearm free flap reconstruction. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:429–432. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000157856.54767.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oniscu GC, Walker WS, Sanderson R. Functional results following pharyngolaryngooesophagectomy with free jejunal graft reconstruction. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2001;19:406–410. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(01)00618-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scharpf J, Esclamado RM. Reconstruction with radial forearm flaps after ablative surgery for hypopharyngeal cancer. Head Neck. 2003;25:261–266. doi: 10.1002/hed.10197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones NF, Eadie PA, Myers EN. Double lumen free jejunal transfer for reconstruction of the entire floor of mouth, pharynx and cervical oesophagus. Br J Plast Surg. 1991;44:44–48. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(91)90177-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Imanishi Y, Isobe K, Nameki H, et al. Extended sigmoid-shaped free jejunal patch for reconstruction of the oral base and pharynx after total glossectomy with laryngectomy. Br J Plast Surg. 2004;57:195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rossmiller SR, Ghanem TA, Gross ND, Wax MK. Modified ileo-colic free flap: viable choice for reconstruction of total laryngo-pharyngectomy with total glossectomy. Head Neck. 2009;31:1215–1219. doi: 10.1002/hed.21083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okazaki M, Asato H, Takushima A, et al. Reconstruction with rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap for total glossectomy with laryngectomy. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2007;23:243–249. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-981502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCarthy CM, Kraus DH, Cordeiro PG. Tracheostomal and cervical esophageal reconstruction with combined deltopectoral flap and microvascular free jejunal transfer after central neck exenteration. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:1304–1310. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000156916.82294.98. discussion 1311–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu P. One-stage reconstruction of complex pharyngoesophageal, tracheal, and anterior neck defects. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:949–956. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000178042.26186.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agarwal JP, Stenson KM, Gottlieb LJ. A simplified design of a dual island fasciocutaneous free flap for simultaneous pharyngoseophageal and anterior neck reconstruction. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2006;22:105–112. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-932504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andrades P, Pehler SF, Baranano CF, Magnuson JS, Carroll WR, Rosenthal EL. Fistula analysis after radial forearm free flap reconstruction of hypopharyngeal defects. Laryngoscope. 2008;118:1157–1163. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31816f695a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paydarfar JA, Birkmeyer NJ. Complications in head and neck surgery: a meta-analysis of postlaryngectomy pharyngocutaneous fistula. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:67–72. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cavalot AL, Gervasio CF, Nazionale G, et al. Pharyngocutaneous fistula as a complication of total laryngectomy: review of the literature and analysis of case records. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;123:587–592. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2000.110617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ganly I, Patel SG, Matsuo J, et al. Analysis of postoperative complications of open partial laryngectomy. Head Neck. 2009;31:338–345. doi: 10.1002/hed.20975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ganly I, Patel S, Matsuo J, et al. Postoperative complications of salvage total laryngectomy. Cancer. 2005;103:2073–2081. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Furuta Y, Homma A, Oridate N, et al. Surgical complications of salvage total laryngectomy following concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Int J Clin Oncol. 2008;13:521–527. doi: 10.1007/s10147-008-0787-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bohannon IA, Desmond RA, Clemons L, Magnuson JS, Carroll WR, Rosenthal EL. Management of the N0 neck in recurrent laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:58–61. doi: 10.1002/lary.20675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pinar E, Oncel S, Calli C, Guclu E, Tatar B. Pharyngocutaneous fistula after total laryngectomy: emphasis on lymph node metastases as a new predisposing factor. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;37:312–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gal RL, Gal TJ, Klotch DW, Cantor AB. Risk factors associated with hypothyroidism after laryngectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;123:211–217. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2000.107528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Léon X, Gras JR, Pérez A, et al. Hypothyroidism in patients treated with total laryngectomy. A multivariate study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2002;259:193–196. doi: 10.1007/s00405-001-0418-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jovanović M, Perović J, Grubor A. The impact of diabetes mellitus on postoperative morbidity in laryngeal surgery. Acta Chir Iugosl. 2006;53:51–55. doi: 10.2298/aci0601051j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fradis M, Podoshin L, Ben David J. Post-laryngectomy pharyngocutaneous fistula—a still unresolved problem. J Laryngol Otol. 1995;109:221–224. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100129743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fung K, Teknos TN, Vandenberg CD, et al. Prevention of wound complications following salvage laryngectomy using free vascularized tissue. Head Neck. 2007;29:425–430. doi: 10.1002/hed.20492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosenthal E, Couch M, Farwell DG, Wax MK. Current concepts in microvascular reconstruction. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;136:519–524. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gil Z, Gupta A, Kummer B, et al. The role of pectoralis major muscle flap in salvage total laryngectomy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;135:1019–1023. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2009.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iteld L, Yu P. Pharyngocutaneous fistula repair after radiotherapy and salvage total laryngectomy. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2007;23:339–345. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-992343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Korpinar S, Cimsit M, Cimsit B, Bugra D, Buyukbabani N. Adjunctive hyperbaric oxygen therapy in radiation-induced non-healing wound. J Dermatol. 2006;33:496–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2006.00117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Uhl E, Sirsjö A, Haapaniemi T, Nilsson G, Nylander G. Hyper-baric oxygen improves wound healing in normal and ischemic skin tissue. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;93:835–841. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199404000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shi Y, Lee CS, Wu J, et al. Effects of hyperbaric oxygen exposure on experimental head and neck tumor growth, oxygenation, and vasculature. Head Neck. 2005;27:362–369. doi: 10.1002/hed.20169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schönmeyr BH, Wong AK, Reid VJ, Gewalli F, Mehrara BJ. The effect of hyperbaric oxygen treatment on squamous cell cancer growth and tumor hypoxia. Ann Plast Surg. 2008;60:81–88. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e31804a806a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dhir K, Reino AJ, Lipana J. Vacuum-assisted closure therapy in the management of head and neck wounds. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:54–61. doi: 10.1002/lary.20000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Andrews BT, Smith RB, Hoffman HT, Funk GF. Orocutaneous and pharyngocutaneous fistula closure using a vacuum-assisted closure system. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2008;117:298–302. doi: 10.1177/000348940811700410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rosenthal EL, Blackwell KE, McGrew B, Carroll WR, Peters GE. Use of negative pressure dressings in head and neck reconstruction. Head Neck. 2005;27:970–975. doi: 10.1002/hed.20265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vidrine DM, Kaler S, Rosenthal EL. A comparison of negative-pressure dressings versus Bolster and splinting of the radial forearm donor site. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133:403–406. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chalian AA, Anderson TD, Weinstein GS, Weber RS. Internal jugular vein versus external jugular vein anastomosis: implications for successful free tissue transfer. Head Neck. 2001;23:475–478. doi: 10.1002/hed.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Head C, Sercarz JA, Abemayor E, Calcaterra TC, Rawnsley JD, Blackwell KE. Microvascular reconstruction after previous neck dissection. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:328–331. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.3.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hanasono MM, Barnea Y, Skoracki RJ. Microvascular surgery in the previously operated and irradiated neck. Microsurgery. 2009;29:1–7. doi: 10.1002/micr.20560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yu P. The transverse cervical vessels as recipient vessels for previously treated head and neck cancer patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:1253–1258. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000156775.01604.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Horng SY, Chen MT. Reversed cephalic vein: a lifeboat in head and neck free-flap reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;92:752–753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Urken ML, Higgins KM, Lee B, Vickery C. Internal mammary artery and vein: recipient vessels for free tissue transfer to the head and neck vessel-depleted neck. Head Neck. 2006;28:797–801. doi: 10.1002/hed.20409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Harris JR, Lueg E, Genden E, Urken ML. The thoracoacromial/cephalic vascular system for microvascular anastomoses in the vessel-depleted neck. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:319–323. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.3.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Aycock JK, Stenson KM, Gottlieb LJ. The thoracoacromial trunk: alternative recipient vessels in reoperative head and neck microsurgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:88–94. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000293858.11494.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]