Abstract

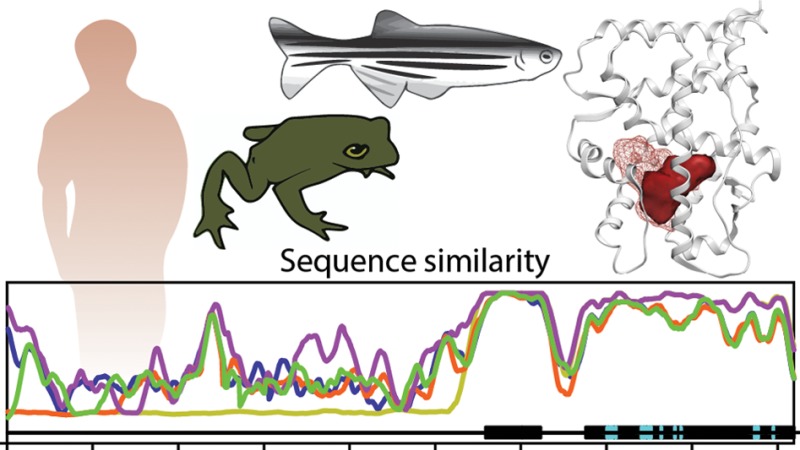

Pharmaceuticals and industrial chemicals, both in the environment and in research settings, commonly interact with aquatic vertebrates. Due to their short life-cycles and the traits that can be generalized to other organisms, fish and amphibians are attractive models for the evaluation of toxicity caused by endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) and adverse drug reactions. EDCs, such as pharmaceuticals or plasticizers, alter the normal function of the endocrine system and pose a significant hazard to human health and the environment. The selection of suitable animal models for toxicity testing is often reliant on high sequence identity between the human proteins and their animal orthologs. Herein, we compare in silico the ligand-binding sites of 28 human “side-effect” targets to their corresponding orthologs in Danio rerio, Pimephales promelas, Takifugu rubripes, Xenopus laevis, and Xenopus tropicalis, as well as subpockets involved in protein interactions with specific chemicals. We found that the ligand-binding pockets had much higher conservation than the full proteins, while the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ and corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 1 were notable exceptions. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the conservation of subpockets may vary dramatically. Finally, we identified the aquatic model(s) with the highest binding site similarity, compared to the corresponding human toxicity target.

Introduction

Aquatic vertebrates are targeted by pharmaceutical and industrial chemicals, both intentionally and unintentionally, in a variety of research and environmental contexts. In the wild, these animals are exposed to the pharmaceuticals and industrial chemicals present in the surface waters. In research settings, aquatic vertebrates may be used to evaluate novel chemicals for toxicity, including the early identification of adverse drug reaction (ADR) or endocrine disruption (ED) potential of pharmaceutical candidates and industrial chemicals.

Lower order vertebrates, such as amphibians and fish, are being increasingly viewed as a replacement for rodent models. They are convenient and cost-effective model organisms due to their short life-cycles and the presence of traits that can be generalized to other organisms.1 Species that are commonly used for toxicological evaluations include Danio rerio (zebrafish), Pimephales promelas (fathead minnow), Takifugu rubripes (Japanese pufferfish), Xenopus laevis (African clawed frog), and Xenopus tropicalis (Western clawed frog).1−4 Specifically, D. rerio has been widely used to study ADRs that include reproductive toxicity, cardiotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, and neurotoxicity,5 as well as the evaluation of potential endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs; reviewed in ref (1)). P. promelas has been used to predict the aquatic toxicity of environmental chemicals,2 and T. rubripes has been used to evaluate EDCs.6,7 Amphibians are known to be good models for studying EDCs that interact with thyroid hormone receptors8 and X. laevis has been used to study ADRs related to membrane transporters.9

Toxicity, for chemicals with low concentrations in the target organisms, is most frequently caused by their specificity to particular proteins in the organism. Comparing the protein sequences and structures of human toxicity targets to their orthologs in aquatic species can assist in the identification of the most similar ortholog.

For the reliable prediction of pharmaceutical or environmental toxicity, robust animal models are required whose proteins are highly similar to the orthologous human ADR and toxicity targets. Additionally, in the wild, these species are more vulnerable than others to pharmaceuticals present in the environment that have been specifically designed for high-affinity interactions with the designated proteins.10

Typically in toxicity studies, one rodent model and one nonrodent model are employed.11 However, depending on the target and the class of chemicals in question, some animal models may be more relevant than others. The ever-increasing number of species with fully sequenced genomes has begun to allow for druggable genome and proteome comparisons. Recently, the genomes of eight relevant toxicological species were compared to the human genome.12 Target similarity has been assessed at the level of protein sequence, with the degree of conservation of specific drug targets in humans and model organisms evaluated by performing sequence-by-sequence alignments,10 and limited studies have been conducted on the domain conservation for the androgen receptor (AR) and estrogen receptor α (ERα).13

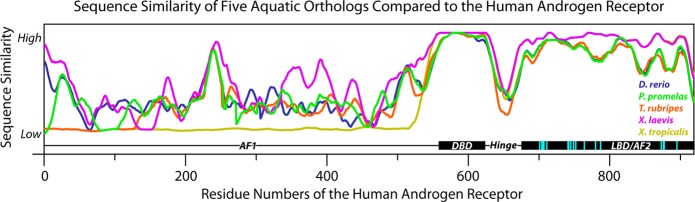

Nevertheless, the levels of conservation between orthologous sequences usually vary throughout the sequence (Figure 1). Thus, it is important to focus on the similarity of sections of the sequence that are most relevant to chemical interactions. The conservation of residues directly involved in ligand binding is a more relevant parameter for evaluation of aquatic species models than full sequence similarity. Interspecies variations in the amino-acid composition of the binding-pocket can sometimes have dramatic effects on the utility of species in pharmacological assays. For example, in the serotonin 6 receptor (5-HT6R), two residues in the ligand-binding pocket were found to significantly change the pharmacology of the mouse 5-HT6R (resulting in a systematic one log unit shift of the 5-HT6R ligands), compared to the human and rat 5-HT6R,15,16 making the mouse model an unfavorable choice for testing 5-HT6R-targeting pharmaceuticals, while the rat 5-HT6R binding pocket is identical to humans. Similarly, two (out of 13) minor amino-acid substitutions (Thr to Ala and Ala to Val) in the binding pocket of the rat and mouse histamine H3 receptors (H3R), compared to the human H3R, lead to a systematic compound potency measurement error and limits both of their utilities in H3-related studies.17

Figure 1.

Variations in sequence conservation across the sequence of the AR for D. rerio, P. promelas, T. rubripes, X. laevis, and X. tropicalis compared to the human AR (binding site residues highlighted in cyan). All sequences were window averaged across 25 residues. Abbreviations: AF1/2, activation function 1/2; DBD, DNA binding domain; LBD, ligand binding domain.14

Because orthologous proteins in different species typically bind the same or similar endogenous ligands,8 the conservation of the binding pockets far exceeds the full length sequence conservation. They are also likely to bind the same exogenous chemicals. The aim of this research was to identify the aquatic organisms (from the set of D. rerio, P. promelas, T. rubripes, X. laevis, and X. tropicalis) that share the highest binding pocket similarity with humans in each of the 28 best-characterized toxicity targets. X-ray crystal structures were used to identify the amino-acid residues constituting the ligand-binding pockets, which were extrapolated to the aquatic orthologs. Sequence similarity and identity were calculated for the ligand-binding sites, and the most similar orthologs to the 28 human toxicity targets were identified.

Materials and Methods

Selection of Human EDC and ADR Targets

An initial set of 85 unique human proteins that have been previously characterized as side-effect and toxicity targets were compiled from the 73 protein assays listed in the Novartis in vitro safety panels (Table S1, Supporting Information), 11 targets from the VirtualToxLab,18,19 and the Constitutive Androstane Receptor (CAR; NR1I3). All 85 proteins were used for sequence analyses. For binding pocket similarity analyses, the 85 targets were matched against the Pocketome encyclopedia (http://pocketome.org),20 a collated set of annotated, binding pocket structure ensembles from the Protein Data Bank (PDB).21 At the time of this study, 28 out of the 85 targets had Pocketome entries for their ligand-binding pockets available (Table S1, Supporting Information) that contained at least one cocrystallized ligand making it possible to precisely identify the binding site residues. These 28 targets were used for binding site similarity and identity comparisons.

Identification of Orthologs of Human EDC and ADR Targets in the Aquatic Species

The complete proteomes of D. rerio, Mus musculus (mouse), P. promelas, Rattus norvegicus (rat), T. rubripes, X. laevis, and X. tropicalis were downloaded in FASTA format from the UniProt Knowledgebase.22 The M. musculus and R. norvegicus results have been included in all Supporting Information for comparison purposes. For each of the files, BLAST search index was generated using the bioinformatics module of the Internal Coordinate Mechanics (ICM) software version 3.7-3a (Molsoft L.L.C., La Jolla, CA).23,24 A BLAST search25 was performed to identify orthologs of the 85 human proteins in the corresponding aquatic species. One hit per target per species was retained using the following prioritization rules: (i) manually annotated orthologs of the toxicity and side-effect targets were retained with the highest priority; (ii) for automatically annotated analogues, orthologs with the same gene name as the human protein and the highest probability score to the human protein were kept; (iii) if only sequence fragments were available, the longest fragment was retained.

Sequence Alignment and Analysis

Pairwise alignments were constructed between the full sequence of human protein and the corresponding orthologs, and pairwise sequence scores were calculated with the Needleman and Wunsch algorithm26 modified for the zero end-gap penalties (the ZEGA algorithm27) as implemented in the ICM program. We used gap opening and gap extension penalties of 2.4 and 0.15, respectively. Sequence identity was represented by the number of identical residues over the total number of aligned residues. Sequence similarity was calculated using the GONNET residue substitution comparison matrix.28

Binding Site Definition and Classification Using Ligand Contact Strength Fingerprints

For each ligand in the pocketome entry and each non-hydrogen atom in the protein, distance-dependent contact strengths were calculated using the parameters developed in context of GPCR Dock 2010 evaluation.29,30 The per-atom contact strengths were aggregated into per-residue contact strength values by taking the sum over all non-hydrogen atoms in the residue side-chain. Only residue side-chains were included in the calculation because, except for proline, ligand contacts with backbone atoms may not be affected by residue substitutions between species. If a ligand was cocrystallized in multiple structures, the vectors of per-residue contact strengths were averaged. To reduce noise and binding site definition artifacts associated with increased conformational variability of individual residues, the contact strength vector components were multiplied by a factor ranging from 0 to 1 and inversely proportional to the observed conformational variability of the corresponding residue in the Pocketome ensemble.

Each unique ligand Li was characterized by a vector FPi of per-residue numbers ranging from 0 (no contact) to 32 (extensive close contact with Phe168 in the adenosine A2A receptor (A2AR); Table S1, Supporting Information). Normalized fingerprint distance between ligands Li and Lj was calculated as D = 1 – (ΣMin(FPi,FPj))/(Σ(FPi + FPj)/(2)) where Min(FPi,FPj) and (FPi+FPj)/2 are vectors of element-wise minima and element-wise averages between vectors FPi and FPj, respectively.30 When defined that way, ligand fingerprint distances range from 0 (for identical fingerprints) to 1 (for nonoverlapping fingerprints). Ligand interaction fingerprints were clustered at the distance cutoff of D = 0.35 to identify classes of ligand occupying distinct areas in the binding site. The cutoff of 0.35 was found to be the optimal trade-off between the excessive number of clusters and the unwanted aggregation of substantially different ligand chemotypes in multiple targets. This cutoff indicates that the ligands will be classified as belonging to different clusters if their fingerprints vary by one-third (or more) of the contacts.

Next, clusters of unique crystallographic ligands were ordered by their size, starting with the most populated one and ending with singletons (i.e., clusters containing only a single ligand). Top clusters containing 80% of the ligands were combined to define the set of residues interacting with the majority of the ligands. The remaining 20% were disregarded in the pocket definition to ensure that it is not affected by occasional or spurious contacts.

Binding Pocket Sequence Identity and Similarity Calculations

For each subpocket in the binding site, as determined by ligand contact strength fingerprint clustering, a subalignment was extracted by projecting the full sequence alignment between human and ortholog sequences onto the corresponding residue selection. Binding pocket/subpocket identity and similarity were calculated from these subalignments using the same parameters as the full sequence alignments. The same was done for the set of residues forming the interaction site(s) for at least 80% of the ligands, as described above, and thus represent the aggregation of the consistently populated regions of the pocket. The comparison of complete pockets (including interaction fingerprints of all crystallographic ligands) is available in Supporting Information.

Results

Orthologs of Human EDC and ADR Targets in Aquatic Vertebrates

Five fish and amphibians frequently used in toxicological evaluations were used in this study: D. rerio, P. promelas, T. rubripes, X. laevis, and X. tropicalis. In their proteomes, we identified the orthologs of the known human side-effect and environmental target proteins. In some cases, orthologs could not be found: 89% of the toxicity targets were identified in D. rerio, 20% in P. promelas, 84% in T. rubripes, 51% in X. laevis, and 85% in X. tropicalis (Table S1, Supporting Information). This may be explained by the fact that only the genomes of D. rerio,31,32T. rubripes,33 and X. tropicalis(34) have been fully sequenced, while the remaining two genomes (P. promelas and X. laevis), and thus proteomes, are incomplete. Additionally, in some cases, only protein fragments of the toxicity target orthologs have been identified. The sequences of the human and orthologous toxicity proteins were aligned, and the full sequence similarity was calculated (Figure 2a, Table S1, Supporting Information).

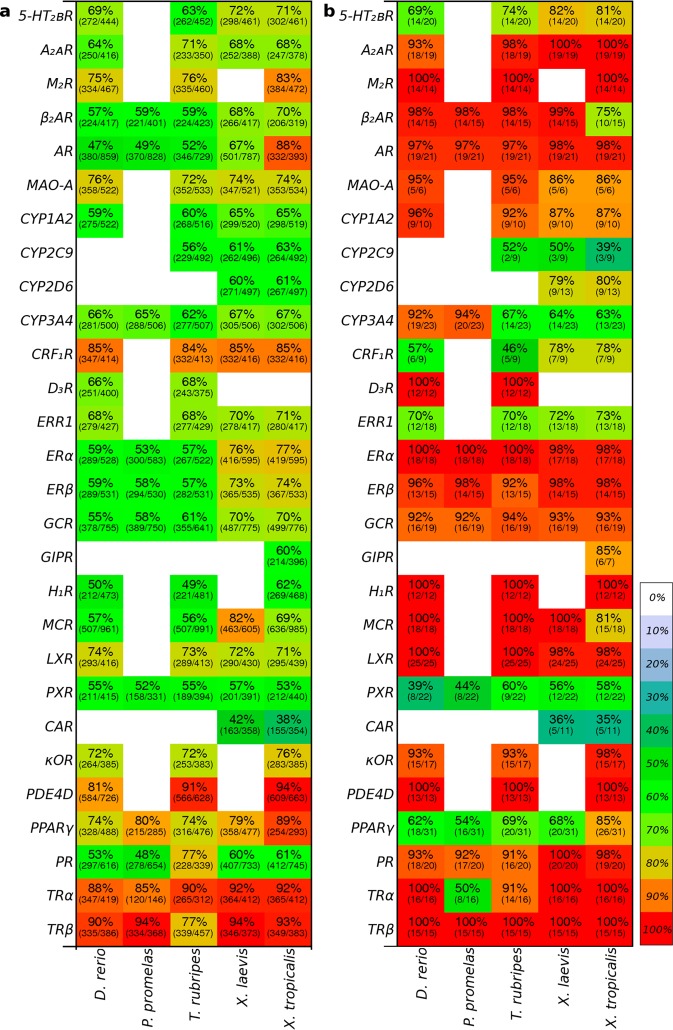

Figure 2.

Sequence similarity (percentage and color) and sequence identity (number of identical residues/number of aligned residues is shown in parentheses) for the 28 toxicity target proteins of (a) the full sequence and (b) the ligand-contact residues conserved for 80% of the cocrystallized ligands. White spaces indicate that no ortholog was identified (often due to an incomplete proteome).

Full Sequence Similarity between Human EDC/ADR Targets and Their Orthologs in Aquatic Vertebrates

The relevance of a model organism for prediction of toxicity in humans has previously been evaluated using the amino acid conservation across entire protein sequences, e.g., ref. (10). In the present study, the majority of the human toxicity targets displayed 60–70% sequence similarity with their aquatic vertebrate orthologs (Figure 2a). The average full sequence similarity between the human proteins and the aquatic orthologs was 69% for D. rerio, 63% for P. promelas, 70% for T. rubripes, 71% for X. laevis, and 72% for X. tropicalis (Figure S1, Supporting Information). In some cases, the overall sequence similarity was relatively high. For example, X. tropicalis had the highest full sequence similarity for the androgen receptor (AR, 88%). However, the protein sequence for X. tropicalis was only a fragment of the full sequence that lacked the N-terminal domain of the protein compared to the other species, giving artificially higher sequence similarity. The corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 1 (CRF1R) is highly conserved in four species (∼85% sequence similarity). The interspecies variations in full sequence similarity were more informative for the estrogen receptors α and β (ERα and ERβ, respectively), and the glucocorticoid receptor (GR), where the full sequences were similar in length. X. laevis and X. tropicalis shared higher conservation of these receptors with human (9–24% higher sequence similarity) than with D. rerio, P. promelas, and T. rubripes. The impact of the variability of the sequence length on the full sequence similarity demonstrates the difficulties with using the full protein sequence (or longest available sequence) in these calculations.

Ligand-Binding Pocket Similarity between Human EDC/ADR Targets and Their Orthologs in Aquatic Vertebrates

As expected, the ligand-binding pockets of the orthologous proteins generally shared higher sequence conservation with the human toxicity targets than the full protein sequences (Figure 2b). For example, the ligand-binding site of human AR shared ∼98% sequence similarity with all five species, whereas the full sequence similarity was only 47–88%. Likewise, the binding sites of ERα, ERβ, and GR are 92–100% conserved in all five aquatic species, while the highest full sequence conservation observed in X. laevis and X. tropicalis did not exceed 70–76%. The relative ranking of species by the full sequence similarity to humans often varies from that by binding pocket similarity. For example, on the basis of full sequence similarity, one would choose X. laevis or X. tropicalis as the most relevant model for testing ERα-targeting chemicals; however, our pocket similarity analysis indicates that all five species are almost equally good, with the fish species having a slight advantage over the frogs. Similarly, despite being most similar to human in terms of full β2 adrenergic receptor (β2AR) sequence, X. tropicalis is probably the least accurate of the five models for evaluation of β2AR ligand pharmacology, as it has as many as 5 residue substitutions in the binding pocket (Figure S3, Supporting Information).

Surprisingly, two targets had lower sequence conservation in the binding site as compared to the full sequence. These were the obesity- and stress-related targets, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) and CRF1R. PPARγ displayed lower binding-site similarity (56–85%) than full sequence similarity (74–89%). CRF1R displayed higher sequence similarity across the full protein sequence (∼85%) than in the peptide-binding site in its extracellular domain (46–78%). However, GPCRs often have a greater degree of sequence variability in the extracellular domains; hence, the lower sequence similarity in the peptide-binding site of CRF1R is consistent with the nature of this receptor.

Ligand-Binding Pockets in ADR/EDC Targets: One Size Does Not Fit All

On closer inspection of the ligand-binding interactions in the X-ray crystal structures of the human EDC and ADR targets, there were often noticeably different residue interaction fingerprints for different ligand chemotypes. In some cases, different chemotypes can bind to distinct ligand-binding pockets or “sub-pockets” of the proteins.

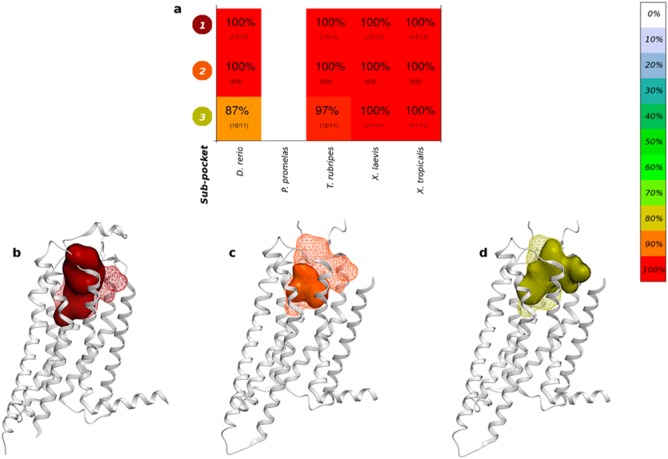

This is exemplified by the identification of three different subpockets of the adenosine A2A receptor (A2AR). Promisingly, the three subpockets identified for A2AR (Figure 3a) correspond to an agonist-bound structure (Figure 3b), the endogenous agonist-bound structure (Figure 3c), and the antagonist-bound structures (Figure 3d), respectively. All subpockets were fully conserved in X. laevis and X. tropicalis. Additionally, significant variations in the conservation of subpockets can be observed for the ortholog of β2AR in X. tropicalis (Figure S3, Supporting Information), where subpocket 1 displays 75% conservation, yet subpocket 2 has only 48% sequence similarity.

Figure 3.

(a) Sequence similarity (percentage and color) and sequence identity (number of identical residues/number of aligned residues is shown in parentheses) for the three A2AR subpockets (white spaces indicate that no ortholog was identified). A2AR crystal structures (gray ribbons), all cocrystallized ligands (mesh), and subpocket (solid surface); (b) subpocket 1 (agonist-bound structures), (c) subpocket 2 (the endogenous agonist-bound structure), and (d) subpocket 3 (antagonist-bound structures).

Because the likelihood of a chemical interacting with an aquatic species ortholog of its target protein largely depends on the conservation of specific interacting residues and not the entire binding site, we sought to identify the individual subpockets in each of the target pockets and to separately evaluate their similarity to the corresponding subpockets in the studied aquatic organisms. Subpockets were identified by the clustering of contact-strength fingerprints (see Materials and Methods).

GPCR Subpocket Sequence Conservation

GPCRs are a superfamily of membrane bound proteins characterized by seven transmembrane (TM) helices and many have been implicated in ADRs, endocrine disruption, and reproductive toxicity.35 The A2AR is implicated in a number of ADRs such as palpitations and angina.18 ADRs for the β2 adrenergic receptor (β2AR) include tremor, cardiac failure, and angina;18 it has also been implicated in ED in aquatic vertebrates.4,36 The serotonin 2B receptor (5-HT2BR) is linked to valvular heart disease;37 the histamine H1 receptor (H1R) is involved in sedation, and the human M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor (M2R) is associated with constipation.18 The dopamine D3 receptor (D3R) is implicated in dyskinesia and Parkinsonism18 and shown to bind the known endocrine disruptor BPA.38 Two class B GPCRs were also evaluated: CRF1R, which is implicated in stress-related disorders,39,40 and the gastric inhibitory polypeptide receptor (GIPR), which is implicated in diabetes and obesity.41

Two subpockets were identified for β2AR (Figure S3, Supporting Information), the classical orthosteric site (subpocket 1) and the orthosteric site with some additional residues from the less conserved TM1/TM2/TM7 region (subpocket 2). Generally, X. tropicalis displayed poor ligand-binding pocket conservation to the human β2AR (75% and 48%, subpockets 1 and 2, respectively). Due to the scarcity of multiple crystal structures for many GPCRs, subpockets were unable to be explored for the 5-HT2BR, D3R H1R, κ opioid receptor (κOR), and M2R; however, the binding pockets were generally well conserved (69–100%; Figures 2b and S4, Supporting Information).

At the time of this study, crystal structures were only available for the extracellular domains of the GPCRs CRF1R and GIPR, which contain the peptide-binding sites. These peptide-binding sites were expected to have lower levels of conservation because it is well established that the extracellular domains of GPCRs have a large degree of sequence variability. Only X. tropicalis had a moderately conserved ortholog for GIPR (61%, Figure S4, Supporting Information), indicating that alternate animal models should also be investigated. X. laevis and X. tropicalis displayed higher ligand-binding pocket similarity across both subpockets (60–78%, Figure S4, Supporting Information). However, it is unlikely that peptides in the environment would result in endocrine disruption via the peptide-binding site of CRF1R and GIPR in either humans or the fish and amphibians evaluated in this study, as potential ED peptides are unlikely to be readily absorbed. Consequently, this technique should also be applied to the small molecule binding site of GIPR when a structure becomes available and to the recently released structure of CRF1R.42

Nuclear Receptor Subpocket Conservation

Nuclear receptors are a superfamily of proteins that regulate development, growth, and homeostasis, and they are commonly implicated in endocrine disruption. Some classic examples of ED that occur via nuclear receptors include the weak agonistic activity of the plasticizer bisphenol A (BPA) against the ERα;43 the feminization of fish by 17α-ethinylestradiol (EE2), a synthetic estrogen in human contraceptives;44 and modulation of PPARγ by EDCs, which is implicated in obesity.45

ERα subpockets were generally highly conserved across the aquatic species (94–100%, Figure S5, Supporting Information), with the exception of T. rubripes for subpocket 8, which is bound to a large estradiol metal chelate ligand (88%). The binding pocket of ERβ across the five species, compared to the human ERβ, was generally highly conserved (92–100%, Figure S4, Supporting Information). However, across all the subpockets, T. rubripes was slightly less conserved (92–95% vs. 98–100%). ERR1 has only been cocrystallized with two unique ligands in two unique subpockets (Figure S4, Supporting Information), with subpocket 2, cocrystallized with a thiazolidinedione, having higher sequence conservation (82–89% vs. 54–60%). The subpockets of the glucocorticoid receptor (GCR) were generally well conserved with the human receptor (91–98%, Figure S4, Supporting Information). The binding sites of the progesterone receptor (PR) for X. laevis and X. tropicalis shared slightly higher pocket conservation with the human receptor (98–100%, Figure S4, Supporting Information). The subpockets of the androgen receptor (AR) were highly conserved (96–100%, Figure S6, Supporting Information), and the subpockets of the thyroid hormone receptor β (TRβ) were fully conserved (100%, Figure S4, Supporting Information). Unlike TRβ, the thyroid hormone receptor α (TRα) did not show full sequence conservation across all species (86–100%; Figure S4, Supporting Information). All subpockets across all species (except for P. promelas for which no ortholog was identified) were fully conserved for the Liver X Receptor (LXR; Figure S4, Supporting Information). While no subpockets were identified for the mineralocorticoid receptor (MCR; Figure S4, Supporting Information), X. tropicalis had the lowest LBD similarity (81%). Of the five aquatic species, T. rubripes consistently displayed higher homology to the human Pregnane X receptor (PXR; 54–64%, Figure S7, Supporting Information). Despite this, the overall pocket similarity was relatively low (maximum 64%), indicating that PXR is not well conserved in these aquatic vertebrates and that other animal models with higher binding site conservation should also be investigated. Similarly, low binding-pocket conservation was observed for the Constitutive Androstane Receptor (CAR; 35–43%; Figure S4, Supporting Information). In 15 out of the 16 subpockets, X. tropicalis had the highest ligand-binding pocket sequence similarity to the human PPARγ (81–100%; Figure S8, Supporting Information). Interestingly X. laevis, a close relative of X. tropicalis, had significantly lower ligand-binding pocket sequence similarity (50–80%).

Cytochrome P450 Subpocket Sequence Conservation

Cytochrome P450s (CYPs) are a superfamily of enzymes that catalyze the oxidation of a diverse range of organic compounds and are commonly involved in the metabolism of xenobiotic compounds. CYPs typically have large and conformationally flexible binding sites in order to accommodate a wide range of chemically dissimilar compounds,46,47 which is supported by the diverse array of subpockets identified. There were closely related orthologs to the human CYP1A2, with D. rerio having the highest pocket similarity (96%, Figure S4, Supporting Information). Both D. rerio and P. promelas had closely related orthologs of CYP3A4 across five out of six subpockets (89–100%, Figure S9, Supporting Information). X. laevis and X. tropicalis had the highest subpocket similarities for CYP2C9 (60–78%); however, the ligand-binding pocket conservation was moderate (Figure S4, Supporting Information). Orthologs of CYP2D6 were only identified in X. laevis and X. tropicalis, which displayed good conservation to the human protein (Figure S4, Supporting Information).

Subpocket Sequence Conservation of Other Enzymes

Monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A) is involved in the catabolism of neurotransmitters and dietary amines; inhibition can lead to neuroendocrine disruption,48 and it is implicated in ADRs including psychosis and hypertensive crisis.49 ADRs associated with cAMP-specific 3′,5′-cyclic phosphodiesterase 4D (PDE4D) include diarrhea and nausea,50 and due to its role in the endocrine system, PDE4D may also be a target for EDCs.51 The binding site of PDE4D was fully conserved across the identified ortholog binding sites (100%, Figure S4, Supporting Information). The subpockets for MAO-A, however, displayed higher sequence similarity for D. rerio and T. rubripes (95%, Figure S4, Supporting Information).

Discussion

The present study performs a comparison of 28 human toxicity targets to their orthologs in five aquatic species, with the goal of identifying the aquatic organisms with the highest ligand-binding pocket sequence similarity to the human toxicity target. The comparison was performed not only at the level of full protein sequences but also, more relevantly, at the level of the ligand-binding sites. By using the X-ray crystal structures of human toxicity targets, residue-level interaction fingerprints were calculated for each unique cocrystallized ligand, and binding pockets and spatially distinct subpockets were identified, with each residue selection extrapolated onto the orthologous proteins in the five aquatic vertebrates. In some cases, the contact fingerprints could also separate the toxicity target crystal structures based on the mode of action of the cocrystallized ligands (such as A2AR; Figure 3), providing a basis for understanding the subpocket sequence conservation.

We identified the aquatic vertebrate(s) that share the highest sequence similarity for the ligand-binding pockets (Table 1), compared to the human toxicity targets, as well as determined the sequence similarity of the spatially distinct subpockets. X. tropicalis had the largest number of orthologs that shared the highest conservation with the human toxicity targets (out of the five aquatic species), having the highest ligand-binding site similarity for 21 out of the 28 toxicity targets, closely followed by D. rerio (19), T. rubripes (19), and X. laevis (18). P. promelas had the lowest number of highly conserved ligand-binding pockets with only 7 ligand-binding sites with high similarity, which can be partially attributed to an incomplete genome.

Table 1. Identification of the Aquatic Vertebrate Model(s) with the Highest Ligand-Binding Pocket Similarity (Denoted by X) Compared to the Corresponding Human Toxicity Targeta.

| aquatic

vertebrate model(s) with the highest ligand-binding pocket similarity |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| receptora | D. rerio | P. promelas | T. rubripes | X. laevis | X. tropicalis |

| 5-HT2BR | X | X | |||

| A2AR | X | X | X | X | |

| M2R | X | X | X | ||

| β2AR | X | X | X | X | |

| AR | X | X | X | X | X |

| MAO-A | X | X | |||

| CYP1A2 | X | X | |||

| CYP2C9* | X | X | |||

| CYP2D6 | X | X | |||

| CYP3A4 | X | X | |||

| CRF1R | X | X | |||

| D3R | X | X | |||

| ERR1 | X | X | X | X | |

| ERα | X | X | X | X | X |

| ERβ | X | X | X | X | X |

| GCR | X | X | X | X | X |

| GIPR | X | ||||

| H1R | X | X | X | ||

| MCR | X | X | X | ||

| LXR | X | X | X | X | |

| PXR* | X | X | X | ||

| CAR* | X | X | |||

| κOR | X | X | X | ||

| PDE4D | X | X | X | ||

| PPARγ | X | ||||

| PR | X | X | |||

| TRα | X | X | X | ||

| TRβ | X | X | X | X | X |

∗ indicates targets where other species should be investigated due to orthologs with only low or moderate pocket similarity.

In this study, we demonstrated that the major difficulty faced when using the full sequence similarity for the comparison of toxicity target orthologs to human proteins is due to variations in the length of the amino acid sequences. For example, while X. tropicalis has the highest full sequence similarity for AR (88%), the longest available sequence of the AR of X. tropicalis was actually incomplete, lacking the N-terminal of the protein including the DNA binding domain (393 residues vs. >729 residues), thus giving artificially higher sequence similarity. This also occurred for some of the aquatic orthologs of MCR, PDE4D, PPARγ, PR, TRα, and TRβ. Additionally, we have shown that high full sequence similarity does not always correlate with high ligand-binding site conservation. For example, the sequence similarity for the extracellular domains of CRF1R for all species is high (∼85%), yet the peptide-binding sites have lower conservation (46–78%). Generally, we have demonstrated that the ligand-binding sites share higher conservation between orthologs, compared to the full sequences (Figure 2). Consequently, we also have shown that the ligand-binding site similarity is the preferred method for the identification of the most conserved orthologs, because it is more informative than the full sequence similarity and it is not influenced by variations in the length of the longest available amino acid sequence of an ortholog. Additionally, if full sequence similarity alone is to be considered, variations in the length of the full (or longest available sequence) should also be incorporated into these assessments.

There are a few caveats that need to be taken into consideration when using orthologous sequence comparisons to aid in the selection of animal models for the evaluation of toxicity. First, the provided principles only suggest toxicity target orthologs in aquatic species based on sequence similarity, without attention to possible variations in the protein function or the downstream pathways.10,52 This method unfortunately does not provide any detail regarding the signaling pathways for orthologous protein and will, of course, require a certain level of understanding of the animal model. Binding pocket similarity may be a necessary but not a sufficient condition for model utility, as exemplified by the pair of human and rat ARs: a large-scale study of interspecies variations in binding affinity of chemicals17 identified this pair as having systematic one log unit differences in potency of multiple diverse chemicals, despite the fact that not only the binding pockets but also the entire ligand binding domain of AR is strictly conserved between human and rat. Second, our method is reliant on the availability of the proteome of the organisms or, at the very least, the availability of sequences of the orthologs of the toxicity targets. Third, calculating ligand-binding site conservation requires X-ray crystal structures of the human toxicity targets, preferably in a complex with a diverse range of chemicals. Both of the problems regarding the availability of the full proteomes and crystal structures can be addressed in future studies, due to the increasing availability of these data. Thus, this study could be expanded to a wider range of toxicity targets and species, including toxicity targets that lack crystal structures, by using crystal structures of highly homologous proteins.

By calculating the amino acid similarity in the ligand-binding pockets, we have successfully avoided the problem of full sequence length variability in sequence similarity calculations, to determine the aquatic orthologs with the most similar ligand-binding pockets for 28 human toxicity targets. This method also allows for the calculation of binding site similarity for subpockets that are involved in the specific chemical–protein interactions. We believe that this study will be a useful tool when designing target-specific assays for the assessment of ADRs and ED potential of chemicals.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by NIH Grants R01 GM071872, U01 GM094612, and U54 GM094618. V.S. was a recipient of a Genentech Foundation research scholarship. The authors gratefully acknowledge Prof. Bryan W. Brooks for useful discussions and sharing his expertise, as well as Clarisse Ricci for useful discussions and for critically reading the manuscript.

Supporting Information Available

Supporting Table S1, the full sequence similarity for D. rerio, P. promelas, T. rubripes, X. laevis, and X. tropicalis, as well as M. musculus and R. norvegicus against all 85 toxicity targets, including the details of the 28 Pocketome entries. Figures S1 and S2, the average sequence similarity of orthologs compared to the corresponding human toxicity target; Figures S3 and S5–S9, selected heat maps of sequence similarity and crystal structures for selected toxicity targets; Figure S4, the heat maps for the remaining toxicity targets. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Segner H. Zebrafish (Danio rerio) as a model organism for investigating endocrine disruption. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C 2009, 1492187–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankley G. T.; Villeneuve D. L. The fathead minnow in aquatic toxicology: Past, present and future. Aquat. Toxicol. 2006, 78191–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg C.; Gyllenhammar I.; Kvarnryd M. Xenopus tropicalis as a test system for developmental and reproductive toxicity. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health, Part A 2009, 723–4219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massarsky A.; Trudeau V. L.; Moon T. W. β-Blockers as endocrine disruptors: The potential effects of human β-blockers on aquatic organisms. J. Exp. Zool., Part A 2011, 315A5251–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath P.; Li C.-Q. Zebrafish: A predictive model for assessing drug-induced toxicity. Drug Discovery Today 2008, 139–10394–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milnes M. R.; Garcia A.; Grossman E.; Grün F.; Jason S.; Tabb M. M.; Kawashima Y.; Katsu Y.; Watanabe H.; Iguchi T.; Blumberg B. Activation of steroid and xenobiotic receptor (SXR, NR1I2) and its orthologs in laboratory, toxicologic, and genome model species. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008, 1167880–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oba Y.; Yamauchi A.; Hashiguchi Y.; Satone H.; Miki S.; Nassef M.; Shimasaki Y.; Kitano T.; Nakao M.; Kawabata S.-i.; Honjo T.; Oshima Y. Purification and characterization of tributyltin-binding protein of tiger puffer, Takifugu rubripes. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C 2011, 153117–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloas W.; Urbatzka R.; Opitz R.; Würtz S.; Behrends T.; Hermelink B.; Hofmann F.; Jagnytsch O.; Kroupova H.; Lorenz C.; Neumann N.; Pietsch C.; Trubiroha A.; Van Ballegooy C.; Wiedemann C.; Lutz I. Endocrine disruption in aquatic vertebrates. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2009, 11631187–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacomini K. M.; Huang S.-M.; Tweedie D. J.; Benet L. Z.; Brouwer K. L. R.; Chu X.; Dahlin A.; Evers R.; Fischer V.; Hillgren K. M.; Hoffmaster K. A.; Ishikawa T.; Keppler D.; Kim R. B.; Lee C. A.; Niemi M.; Polli J. W.; Sugiyama Y.; Swaan P. W.; Ware J. A.; Wright S. H.; Yee S. W.; Zamek-Gliszczynski M. J.; Zhang L.; Membrane transporters in drug development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2010, 93215–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnarsson L.; Jauhiainen A.; Kristiansson E.; Nerman O.; Larsson D. G. J. Evolutionary conservation of human drug targets in organisms used for environmental risk assessments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42155807–5813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixit R.; Boelsterli U. A. Healthy animals and animal models of human disease(s) in safety assessment of human pharmaceuticals, including therapeutic antibodies. Drug Discovery Today 2007, 127–8336–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vamathevan J. J.; Hall M. D.; Hasan S.; Woollard P. M.; Xu M.; Yang Y.; Li X.; Wang X.; Kenny S.; Brown J. R.; Huxley-Jones J.; Lyon J.; Haselden J.; Min J.; Sanseau P. Minipig and beagle animal model genomes aid species selection in pharmaceutical discovery and development. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2013, 2702149–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohno S.; Katsu Y.; Iguchi T.; Guillette L. J. Novel approaches for the study of vertebrate steroid hormone receptors. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2008, 484527–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho C. K. M.; Habib F. K. Estrogen and androgen signaling in the pathogenesis of BPH. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2011, 8129–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setola V.; Roth B. L. Why mice are neither miniature humans nor small rats: A cautionary tale involving 5-hydroxytryptamine-6 serotonin receptor species variants. Mol. Pharmacol. 2003, 6461277–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst W. D.; Abrahamsen B.; Blaney F. E.; Calver A. R.; Aloj L.; Price G. W.; Medhurst A. D. Differences in the central nervous system distribution and pharmacology of the mouse 5-hydroxytryptamine-6 receptor compared with rat and human receptors investigated by radioligand binding, site-directed mutagenesis, and molecular modeling. Mol. Pharmacol. 2003, 6461295–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger F. A.; Overington J. P. Global analysis of small molecule binding to related protein targets. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2012, 81e1002333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lounkine E.; Keiser M. J.; Whitebread S.; Mikhailov D.; Hamon J.; Jenkins J. L.; Lavan P.; Weber E.; Doak A. K.; Cote S.; Shoichet B. K.; Urban L. Large-scale prediction and testing of drug activity on side-effect targets. Nature 2012, 4867403361–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vedani A.; Dobler M.; Smiesko M. VirtualToxLab - A platform for estimating the toxic potential of drugs, chemicals and natural products. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2012, 2612142–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kufareva I.; Ilatovskiy A. V.; Abagyan R. Pocketome: An encyclopedia of small-molecule binding sites in 4D. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40Database IssueD535–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman H. M.; Westbrook J.; Feng Z.; Gilliland G.; Bhat T. N.; Weissig H.; Shindyalov I. N.; Bourne P. E. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 281235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reorganizing the protein space at the Universal Protein Resource (UniProt). Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40D1D71–D75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ICM, version 3.7-a; Molsoft L.L.C.: La Jolla, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Abagyan R.; Totrov M. Biased probability Monte Carlo conformational searches and electrostatic calculations for peptides and proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 1994, 2353983–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S. F.; Gish W.; Miller W.; Myers E. W.; Lipman D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 2153403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needleman S. B.; Wunsch C. D. A general method applicable to the search for similarities in the amino acid sequence of two proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 1970, 483443–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abagyan R. A.; Batalov S. Do aligned sequences share the same fold?. J. Mol. Biol. 1997, 2731355–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonnet G.; Cohen M.; Benner S. Exhaustive matching of the entire protein sequence database. Science 1992, 25650621443–1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kufareva I.; Rueda M.; Katritch V.; Stevens R. C.; Abagyan R. Status of GPCR modeling and docking as reflected by community-wide GPCR dock 2010 assessment. Structure 2011, 1981108–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kufareva I.; Abagyan R.. Methods of Protein Structure Comparison. In Homology Modeling; Orry A. J. W., Abagyan R., Eds.; Humana Press: New York, 2012; Vol. 857, pp 231–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postlethwait J. H.; Yan Y.-L.; Gates M. A.; Horne S.; Amores A.; Brownlie A.; Donovan A.; Egan E. S.; Force A.; Gong Z.; Goutel C.; Fritz A.; Kelsh R.; Knapik E.; Liao E.; Paw B.; Ransom D.; Singer A.; Thomson M.; Abduljabbar T. S.; Yelick P.; Beier D.; Joly J. S.; Larhammar D.; Rosa F.; Westerfield M.; Zon L. I.; Johnson S. L.; Talbot W. S. Vertebrate genome evolution and the zebrafish gene map. Nat. Genet. 1998, 184345–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amores A.; Force A.; Yan Y.-L.; Joly L.; Amemiya C.; Fritz A.; Ho R. K.; Langeland J.; Prince V.; Wang Y.-L.; Westerfield M.; Ekker M.; Postlethwait J. H. Zebrafish hox clusters and vertebrate genome evolution. Science 1998, 28253941711–1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio S.; Chapman J.; Stupka E.; Putnam N.; Chia J.-m.; Dehal P.; Christoffels A.; Rash S.; Hoon S.; Smit A.; Gelpke M. D. S.; Roach J.; Oh T.; Ho I. Y.; Wong M.; Detter C.; Verhoef F.; Predki P.; Tay A.; Lucas S.; Richardson P.; Smith S. F.; Clark M. S.; Edwards Y. J. K.; Doggett N.; Zharkikh A.; Tavtigian S. V.; Pruss D.; Barnstead M.; Evans C.; Baden H.; Powell J.; Glusman G.; Rowen L.; Hood L.; Tan Y. H.; Elgar G.; Hawkins T.; Venkatesh B.; Rokhsar D.; Brenner S. Whole-genome shotgun assembly and analysis of the genome of Fugu rubripes. Science 2002, 29755851301–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellsten U.; Harland R. M.; Gilchrist M. J.; Hendrix D.; Jurka J.; Kapitonov V.; Ovcharenko I.; Putnam N. H.; Shu S.; Taher L.; Blitz I. L.; Blumberg B.; Dichmann D. S.; Dubchak I.; Amaya E.; Detter J. C.; Fletcher R.; Gerhard D. S.; Goodstein D.; Graves T.; Grigoriev I. V.; Grimwood J.; Kawashima T.; Lindquist E.; Lucas S. M.; Mead P. E.; Mitros T.; Ogino H.; Ohta Y.; Poliakov A. V.; Pollet N.; Robert J.; Salamov A.; Sater A. K.; Schmutz J.; Terry A.; Vize P. D.; Warren W. C.; Wells D.; Wills A.; Wilson R. K.; Zimmerman L. B.; Zorn A. M.; Grainger R.; Grammer T.; Khokha M. K.; Richardson P. M.; Rokhsar D. S. The genome of the western clawed frog Xenopus tropicalis. Science 2010, 3285978633–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M. T.; Knudsen T. B.; Reif D. M.; Houck K. A.; Judson R. S.; Kavlock R. J.; Dix D. J. Predictive model of rat reproductive toxicity from ToxCast high throughput screening. Biol. Reprod. 2011, 852327–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen S. F.; Giltrow E.; Huggett D. B.; Hutchinson T. H.; Saye J.; Winter M. J.; Sumpter J. P. Comparative physiology, pharmacology and toxicology of β-blockers: Mammals versus fish. Aquat. Toxicol. 2007, 823145–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman R. B.; Baumann M. H.; Savage J. E.; Rauser L.; McBride A.; Hufeisen S. J.; Roth B. L. Evidence for possible involvement of 5-HT2B receptors in the cardiac valvulopathy associated with fenfluramine and other serotonergic medications. Circulation 2000, 102232836–2841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuo K.; Narita M.; Yoshida T.; Narita M.; Suzuki T. Functional changes in dopamine D3 receptors by prenatal and neonatal exposure to an endocrine disruptor bisphenol-A in mice. Addict. Biol. 2004, 9119–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overstreet D. H.; Knapp D. J.; Breese G. R. Can CRF1 receptor antagonists become antidepressant and/or anxiolytic agents?. Drug Dev. Res. 2005, 654191–204. [Google Scholar]

- Hauger R. L.; Grigoriadis D. E.; Dallman M. F.; Plotsky P. M.; Vale W. W.; Dautzenberg F. M. International Union of Pharmacology. XXXVI. Current status of the nomenclature for receptors for corticotropin-releasing factor and their ligands. Pharmacol. Rev. 2003, 55121–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin N.; Flatt P. R. Therapeutic potential for GIP receptor agonists and antagonists. Best Pract. Res., Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 234499–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenstein K.; Kean J.; Bortolato A.; Cheng R. K. Y.; Dore A. S.; Jazayeri A.; Cooke R. M.; Weir M.; Marshall F. H. Structure of class B GPCR corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 1. Nature 2013, 4997459438–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint S.; Markle T.; Thompson S.; Wallace E. Bisphenol A exposure, effects, and policy: A wildlife perspective. J. Environ. Manage. 2012, 104, 19–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott J. L.; Blunt B. R. Life-cycle exposure of fathead minnows (Pimephales promelas) to an ethinylestradiol concentration below 1 ng/L reduces egg fertilization success and demasculinizes males. Environ. Toxicol. 2005, 202131–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janesick A.; Blumberg B. Minireview: PPARγ as the target of obesogens. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2011, 1271–24–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pochapsky T. C.; Kazanis S.; Dang M. Conformational plasticity and structure/function relationships in cytochromes P450. Antioxid. Redox Signaling 2010, 1381273–1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekroos M.; Sjögren T. Structural basis for ligand promiscuity in cytochrome P450 3A4. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006, 1033713682–13687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milestone C. B.; Orrego R.; Scott P. D.; Waye A.; Kohli J.; O’Connor B. I.; Smith B.; Engelhardt H.; Servos M. R.; MacLatchy D. L.; Smith D. S.; Trudeau V. L.; Arnason J. T.; Kovacs T.; Heid Furley T.; Slade A. H.; Holdway D. A.; Hewitt L. M. Evaluating the potential of effluents and wood feedstocks from pulp and paper mills in Brazil, Canada, and New Zealand to affect fish reproduction: Chemical profiling and in vitro assessments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 4631849–1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolato M.; Chen K.; Shih J. C. Monoamine oxidase inactivation: From pathophysiology to therapeutics. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2008, 6013–141527–1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boswell-Smith V.; Spina D. PDE4 inhibitors as potential therapeutic agents in the treatment of COPD-focus on roflumilast. Int. J. Chronic Obstruct. Pulm. Dis. 2007, 2, 121–129. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vezzosi D.; Bertherat J. Phosphodiesterases in endocrine physiology and disease. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2011, 1652177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searls D. B. Pharmacophylogenomics: Genes, evolution and drug targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2003, 28613–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.