Abstract

School bullying incidents, particularly experiences with victimization, are a significant social and health concern among adolescents. The current study extended past research by examining the daily peer victimization experiences of Mexican-American adolescents and examining how chronic (mean-level) and episodic (daily-level) victimization incidents at school are associated with psychosocial, physical and school adjustment. Across a two-week span, 428 ninth and tenth grade Mexican-American students (51 % female) completed brief checklists every night before going to bed. Hierarchical linear model analyses revealed that, at the individual level, Mexican-American adolescents’ who reported more chronic peer victimization incidents across the two-weeks also reported heightened distress and academic problems. After accounting for adolescent’s mean levels of peer victimization, daily victimization incidents were associated with more school adjustment problems (i.e., academic problems, perceived role fulfillment as a good student). Additionally, support was found for the mediation model in which distress accounts for the mean-level association between peer victimization and academic problems. The results from the current study revealed that everyday peer victimization experiences among Mexican-American high school students have negative implications for adolescents’ adjustment, across multiple domains.

Keywords: Bullying, Peer victimization, Adolescence, Mexican-American students, Daily methods

Introduction

School bullying experiences are a significant social and health concern among youth, both in the United States and around the world. Adolescents who are victimized by peers are more likely to have maladaptive psychological and academic outcomes (e.g., Juvonen et al. 2003, 2011). Moreover, there is emerging evidence to suggest that victimization experiences are associated with adolescents’ physical health (e.g., Gini and Pozzoli 2009). Peer victimization is broadly defined as the experience of being a target of aggressive actions (e.g., name-calling, threats, spreading rumors, pushing) by other peers (e.g., Bauman 2008; Graham 2006). Given the important role of peers during adolescent development (Kupersmidt and Coie 1990), negative peer interactions in the form of victimization can disrupt adolescents’ emotional, social and even physical development. These associations are particularly disconcerting given that school victimization incidents are not uncommon for adolescents; a nationally representative study of over 7,000 students in sixth through tenth grades shows that about 13 % of adolescents are physically victimized and 37 % are verbally victimized (Wang et al. 2009). Thus, peer victimization is a topic of concern for researchers, parents, clinicians, and school personnel.

Although much has been learned about adolescents’ experiences with peer victimization from previous research, some important limitations still exist in the current literature. One limitation is that research on peer victimization predominately has focused on the experiences of White students, with little known about the experiences of ethnic minority youth. Despite the growing inclusion of ethnically diverse samples in school victimization research (e.g., Bellmore et al. 2004; Tharp-Taylor et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2009), we know very little about the experiences and consequences of peer victimization among Mexican-American adolescents (see Bauman and Summers 2009 for an exception). Mexican-American youth are the largest Latino group in the United States and their representation in public school systems is rapidly growing (Pew Hispanic Research Center 2011). Mexican-American youth are at elevated risk for both mental health problems (e.g., Roberts et al. 1997) and of doing poorly in school (e.g., Kohler and Lazarin 2007). Therefore, it is important to better understand how peer victimization experiences are related to their adjustment.

Another limitation in the field is that, to date, peer victimization research has been limited in the types of methodology used. Despite the fact that daily assessments are recognized as a promising and useful method (Bolger et al. 2003), they only have been used in a handful of peer victimization studies (Nishina and Juvonen 2005; Lehman and Repetti 2007). Thus, given that an overwhelming majority of peer victimization studies rely on traditional, one-time surveys, the use of daily diary methodology will extend current research.

Furthermore, given that past studies indicate that peer victimization peaks during middle school and is more common in the middle school years compared to the high school years (e.g., Kaufman et al. 1999; Nansel et al. 2001), much of the victimization literature has focused on victimization incidents during middle school. Despite being more rare, understanding peer victimization experiences that occur in late adolescence, during the high school years, is important because it has been suggested that these incidents can propel adolescents towards school withdrawal (Kupersmidt et al. 1990) during a developmental time that is critical for school success (National High School Center 2007). In the current study, these gaps are addressed by relying on daily report methodology to examine whether peer victimization incidents are associated with psychosocial, physical and school adjustment, among a sample of Mexican-American high school students.

Adolescents’ School Peer Victimization Experiences

Results of large-scale survey studies among adolescent students reveal that peer victimization experiences are associated with indicators of psychosocial adjustment such as depression, anxiety, loneliness, and suicidal ideation (e.g., Fitzpatrick et al. 2010; Juvonen et al. 2003; Kochenderfer and Ladd 1997; Menesini et al. 2009) as well as health problems, including headaches and stomachaches (Nishina et al. 2005). For example, among a diverse sample of sixth grade students, Juvonen et al. (2003) found that students who were victimized by their peers reported higher levels of depression, social anxiety and loneliness when compared to students who were classified as bullies, bully-victims or uninvolved in bullying. Less research has examined associations with physical health symptoms (e.g., Nishina et al. 2005). Results from a small meta-analysis revealed that, across 11 samples, youth who were targeted by peers were at two times higher risk for psychosomatic complaints (compared to uninvolved youth; Gini and Pozzoli 2009). There is growing evidence showing that an association exists between peer victimization experiences and adolescents’ physical health, but overall results are still mixed.

In addition, research relying on traditional survey methods shows that peer victimization is associated with school adjustment. A meta-analysis concluded that victimized students are more likely to earn lower grades and score lower on achievement tests (Nakamoto and Schwartz 2010). Relying on longitudinal data across the 3 years of middle school, Juvonen, Wang and Espinoza (2011) examined how school-based peer victimization experiences compromise urban students’ (44 % Latino) academic performance. After controlling for demographic and school-level differences, results showed that victims of peer victimization had lower GPAs and were perceived as less engaged by their teachers across all 3 years of middle school. Support also exists for indirect, or mediational models, such that victims tend to be less engaged in school, with psychosocial problems mediating the effects (Nishina et al. 2005). Teens who are ridiculed are likely to feel more depressed or anxious and, therefore, may disengage from school activities and have difficulty concentrating on tasks (Buhs and Ladd 2001). Evidence suggests that peer victimization has direct and indirect associations with school adjustment.

Most studies examining peer victimization and adjustment have relied on cross-sectional designs, making it difficult to draw inferences about the direction of effects. Although peer victimization research has supported both possible directions (i.e., victimized youth have greater adjustment problems, and youth who have adjustment problems are also more likely to be victimized by their peers) evidence from existing longitudinal studies seem to provide more evidence for the model in which victimization incidents are associated with later psychosocial and academic maladjustment. A study of Dutch children showed that those children who were bullied at the beginning of the school year were more likely to develop psychosocial symptoms during the course of the school year (Fekkes et al. 2006). Although results also showed that children with psychosocial problems the beginning of the school year were at higher risk of being targeted at the end of school year, the odds ratio for depression and anxiety were lower in this direction. In a study of Australian adolescents, (Bond et al. 2001) found that victimization during eighth grade was associated with anxiety and depression during ninth grade. No support was found for the hypothesis that depression and anxiety in eighth grade predict later victimization. Furthermore, Kochenderfer and Ladd (1996) showed that being bullied at school was a precursor to school problems such as lower academic achievement and higher school avoidance, but school adjustment problems in the fall did not predict later school bullying. In sum, evidence from traditional cross-sectional and longitudinal studies indicate that being targeted by peers affect victims’ psychosocial and school adjustment.

A Focus on the Experiences of Mexican-American Adolescents

Generally, Mexican-American adolescents living in the United States are at heightened risk for several mental health and school problems. For example, Mexican-American adolescents report higher levels of depressive symptoms com-pared to adolescents from other ethnic backgrounds (Hill et al. 2003; Joiner et al. 2001). With regards to academics, whether the objective index of school failure is low engagement, dropout rates, low standardized test performance or low college-entrance rates, Mexican-American students are represented disproportionately as at-risk for school failure. For example, since 1980, Mexican-Americans have had the lowest rates of high school completion, compared to Whites, Blacks and Asian and Pacific-Islander groups and also compared to youth from other Latino groups (e.g., Puerto Ricans; U.S. Census Bureau 2010). Ream and Rumberger (2008) found that Mexican-American students spent less time on homework and extracurricular activity involvement, compared to non-Latino White students. Across objective school success indicators and informal scholastic activities, Mexican-American youth struggle academically.

To date, ethnic minority youth peer victimization experiences predominately have been studied within the context of ethnic group comparisons. Hanish and Guerra (2000) found that although they reported less victimization than White or African-American students, Latino students were more likely to be victimized repeatedly when they were targeted. Although comparative studies are important, several researchers (e.g., García Coll et al. 1996) have indicated that studies of ethnic differences provide limited information about the development and adjustment of ethnic minority youth and the importance of studying within group patterns and differences has been stressed (e.g., Han 2008). Thus, we build on the ethnic-comparative work on the associations of bullying and adjustment among adolescents to explore potential within group differences in daily-level associations based on the grade, gender, and generational status of Mexican-American high school students. For example, given that the high school transition year is particularly disconcerting for students (e.g., Barber and Olsen 2004; Benner and Graham 2009), victimization experiences may be particularly distressing and related to maladjustment for ninth grade students who have just transitioned into high school, compared to tenth grade students. Also, while some evidence suggests that boys and girls differ in the extent to which victimization experiences are perceived as harmful and associated with their adjustment (Crick et al. 1996), other studies find no gender differences (e.g., La Greca and Harrison 2005). Furthermore, it is less known whether gender may moderate associations with school adjustment indicators and victimization among Mexican-American adolescents.

Additionally, few studies have tested empirically whether generational status moderates associations between victimization and adjustment. Some researchers speculate that given the additional challenges that immigrant adolescents face (e.g., identity development, “fitting in” with peer groups), experiencing victimization may be more detrimental to their adjustment compared to nonimmigrant youth (i.e., third generation; McKenney et al. 2006). Conversely, given that second- and third-generation students may have more friends and generally place more importance on peers than first generation students (e.g., Strohmeier et al. 2011), being threatened or insulted by peers may be especially harmful for them compared to first generation students. Examining whether the impact of peer victimization varies among Mexican-American adolescents depending on their grade, gender or generational status will provide insights into the within group differences that may exist.

Most programs and policies aimed at promoting health and school success among Latino groups emphasize the family role (Hill and Torres 2010), with little attention paid to peer influences. Indeed, research has pointed towards several family, home and neighborhood factors that may help explain why Mexican-American adolescents do poorly in school, such as experiences of discrimination (Stone and Han 2005; Wayman 2002) and harsh parenting practices (Dumka et al. 2009). Although these home and family factors are important to consider, it is also critical to extend current research and examine how everyday school peer victimization experiences may compromise not only the school adjustment of Mexican-American adolescents but also their psychosocial and physical well-being. Also, there is a growing need to understand the underlying processes that can account for the associations between discrete, everyday victimization experiences and adjustment problems. Utilizing daily assessments allows us to examine associations and underlying processes at both the mean (between-subjects) and daily (within-subjects) level.

A Daily Checklist Approach

Previous school peer victimization research that has largely relied upon traditional, mean-differences measures holds some key limitations that a daily-checklist approach can address. One limitation is that the peer victimization associations found in traditional surveys may be driven by numerous individual-differences such as adolescents’ coping strategies, number of friends, limited social support or a hostile attribution bias (e.g., Baldry and Farrington 2005; Dodge 2006; Nakamoto and Schwartz 2011; Naylor et al. 2001). Daily-level methodology provides reassurance that associations are not a result of unmeasured individual differences because responses are compared within-individuals over time. Additionally, we have a limited understanding of how victimization experiences impact adolescents on a day-to-day basis. That is, research has shown that students who, on average, experience more victimization report greater distress and more school problems, compared to their peers who are not targeted. Although longitudinal designs across spans of several months or years indicate that, across multiple time points, victimization is associated with poor adjustment, these designs do not specify whether a single incident of being threatened or insulted on any given school day, over and above mean-levels of victimization, is sufficient for an adolescent to report more distress or school problems. Utilizing daily methods allows us to examine specifically how peer victimization experiences are associated with adolescents’ adjustment on a daily basis.

Daily assessment methodology has been described as a useful tool for “capturing life as it is lived” (Bolger et al. 2003) and has several methodological strengths. With traditional, one-time measures, youth must rely on retrospective accounts. Asking teens to report on specific experiences, feelings and behaviors on a daily basis reduces the time elapsed between the actual experience and their account of the experience. This provides more reliable information than surveys that ask students to think back on experiences that happened in the last several months or year. Moreover, by repeatedly assessing the associations between victimization encounters and various indicators of adjustment, we may be able to better capture the dynamic nature of how and why discrete social experiences are related to emotional distress and other adjustment indices (Laurenceau et al. 2005). As previously mentioned, daily methods allow estimation of the associations between variables of interest at the between-persons, mean level and within-person, daily level. Mean level questions can be addressed, such as whether adolescents who experience chronic levels of peer victimization also report high levels of distress, and daily level questions such as whether Mexican-American adolescents report more academic problems, such as doing poorly on a quiz, on days that they are victimized by their peers at school. Testing episodic (e.g., daily level) victimization associations allows an estimation of whether specific events, behaviors or feelings co-occur with one another on a daily basis to provide a more complete picture of Mexican-American adolescents’ everyday peer victimization experiences.

The few peer victimization studies that have relied on daily checklists highlight the usefulness and affordances of the method (e.g., Repetti 1996). Based on daily reports across five days, Lehman and Repetti (2007) found that negative peer experiences at school (e.g., being teased) led to negative changes in mood and self-esteem, which, in turn, were associated with aversive interactions with their parents. Based on sixth grade students’ daily reports on five school days, Nishina and Juvonen (2005) found that on days when youth reported being victimized, they reported more feelings of anger and anxiety. To date, the few school victimization studies that have used daily methods have been conducted with elementary- or middle school-aged children. Given that experiences with peer victimization do not follow a stable trajectory through adolescence (e.g., Nansel et al. 2001), it is important to understand how daily experiences are associated with adolescents’ psychosocial, physical and academic adjustment during the high school years.

Current Study

The current study is guided by three research aims. The first aim is to describe how frequently Mexican-American high school students experience peer victimization in their day-to-day lives and examine if differences in prevalence exist based on grade, gender or generational status. The second aim is to examine whether episodic and/or chronic peer victimization is related to Mexican-American adolescents’ psychosocial (i.e., distress), physical and school (i.e., academic problems, role fulfillment as a good student) adjustment. Moreover, whether significant variability found in daily-level associations vary by individual-level factors including grade, gender or generational status will be tested. The third and final aim is to test whether adolescents’ levels of distress mediate the association between victimization and school adjustment.

We focused on the experiences of ninth and tenth grade students because research indicates that students’ experiences in their first years of high school can be influential in determining success for the rest of the high school years (National High School Center 2007). In particular, it has been posited that the engagement of Mexican-American students can be particularly sensitive to the social environment of the school (Mehan et al. 1996). In addition, although victimization peaks in the middle school grades (e.g., Kaufman et al. 1999; Nansel et al. 2001), past research indicates that there is also a peak in peer victimization incidents following the transition to high school and that it is more common among the first 2 years of high school compared to the final high school years (Nansel et al. 2001; Pepler et al. 2006). Thus, it is important to examine how everyday peer victimization incidents that occur in the early high school years are related to multiple adjustment indices among Mexican-American students.

Methods

Participants

Ninth and tenth grade Mexican-American students were recruited from two public high schools in the Los Angeles area. These schools were chosen because they both were comprised of a large Latino student population and had similar student socio-economic status and achievement levels. The first school was comprised of mostly Latino (62 %), African-American (16 %) and Asian (10 %) students and 73 % of students were eligible for free or reduced lunch. This school tended to be between average and below average in the academic performance index (API) distribution for schools in California. The second school consisted of predominately Latino (94 %) students and 71 % of students were eligible for free or reduced lunch. This school falls between below and well-below average in the California schools API ranking.

Ninth and tenth grade students with Mexican backgrounds in the two schools were invited to participate. Among all students who were invited and eligible, 63 % agreed to participate (e.g., parents provided consent and adolescents provided assent), a rate which compares favorably with similarly intensive daily diary studies of Latino families (e.g., Updegraff et al. 2005). A total of 428 adolescents (Mage = 15.02 years, SDage = .83 years) participated and the sample was equally split by gender (51 % female) and across the ninth and tenth grades. A majority of the adolescents (70 %) were second-generation, that is, the adolescent was born in the United States and at least one parent was born in Mexico. Seventeen percent were first-generation (i.e., adolescent and parents born in Mexico) and 13 % were third generation (i.e., adolescent and parents born in the U.S.). Slightly more than half (55 %) of adolescents reported that they spoke both English and Spanish in their home, 35 % spoke only Spanish and 10 % reported that they spoke only English at home. The primary caregivers were predominantly adolescents’ mothers (83 %), but fathers (13 %) and grandparents, aunts, or uncles (4 %) also participated in the study. Educational levels of the primary caregivers showed variation; 29 % of caregivers attended only elementary school, 45 % attended up to secondary school, and 26 % attended some college.

For the current study focusing on daily school peer victimization experiences, only the adolescent daily checklist data were used. Moreover, although adolescents were asked to complete 14 consecutive days of checklists, only data from the days that students attended school were used. This usually resulted in a maximum of 10 days being used in analyses. It is possible that for some students there were less than ten checklist days analyzed, if, for example, there was a school holiday or the adolescent did not attend school because they felt sick. The final analytic sample for the current study included 368 adolescents who completed at least one checklist during a school day across the two-week span, although as described below, virtually all of the checklist days were completed by the sample. Independent sample t tests were run to examine if differences existed between the participants who completed the daily checklists and those who did not complete the checklists but did complete the initial questionnaire. Results revealed no differences on demographics such as age, generational status, and number of adults living in home and also no differences for psychological indicators (e.g., self-esteem, anxiousness), physical symptoms or school motivation indicators (e.g., educational aspirations; all p’s >.05).

Procedures

Participant recruitment and participation was distributed across the 2009–2010 school year. Students received information about the study via home mailings (in English and Spanish) as well as classroom presentations made by graduate students. Following the home mailing and classroom presentations, trained researchers made calls to parents or guardians to further describe the study and invite them to participate. As part of the larger study design, parents were also invited to participate. If the caretaker-child dyad agreed to participate, a meeting time was scheduled (most often in the family home) to complete the consent and assent process in-person and complete a questionnaire. Adolescents completed the paper and pencil questionnaire independently in a private space.

After completing the initial questionnaire, adolescents were given a 14-day supply of checklists to complete at home every night before going to bed. The adolescents received instructions on how to complete the checklists and they were given a number for the study that they could call if they had questions. Participants received a phone call on the second and seventh day to remind them to complete the checklists every night and to answer any questions they may have. It took adolescents approximately 5 min to complete the checklist each night. After completing the daily checklist, participants were instructed to fold it over and stamp the seal with an electronic time-stamper. The time stamper is a small, hand-held device that imprints the current date and time and is password-protected so that the data and time cannot be changed. At the end of the two-week period the researcher picked up the checklists, and each adolescent received $30 for participating. As an additional incentive, adolescents were told that they would receive two movie passes in the mail, if upon inspection of the checklists it seemed that they had completed them correctly and on time. These methods of monitoring daily checklists completion resulted in high compliance; 96 % of the checklists were completed and 81 % of all were completed on time. A checklist was considered on time if it was completed either on the same night or before 7:00am on the following day. Analyses were run including only the checklists that were completed on time and because the results from these analyses did not differ from those including all completed checklists, the findings reported in the results section include all of the completed checklists, whether or not they were completed on time.

Measures

All measures used in the current study were reported in the adolescent daily checklists, with the exception of demographics that were reported in both the parent and adolescent questionnaires. The questionnaires included the primary caregiver’s reports of birthplace and the adolescent’s reports of their grade level, birthplace, age and languages spoken at home. The daily checklists assessed a variety of events, activities and moods. The specific daily checklist measures that were used are described below and Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the mean-level computed variables (averages across all days).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for mean level variables

| Mean | SD | Scale range |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Peer victimization | .06 | .15 | 0–1 |

| Distress | 1.57 | .60 | 1–5 |

| Physical symptoms | 1.56 | .62 | 1–5 |

| Academic problems | .14 | .19 | 0–1 |

| Role fulfillment as a good student | 4.19 | 1.86 | 1–7 |

Daily School Peer Victimization

Two items were used to assess peer victimization incidents. Specifically, on all school days adolescents were asked to indicate if “someone from school threatened, insulted or made fun of you” and if “someone from school hit, kicked or shoved you” during the day. The items tap into verbal and physical victimization, respectively. These items have been used previously in a daily diary study (Nishina and Juvonen 2005). Correlation analysis revealed that both items are strongly correlated (r = .44, p < .001), thus, the two items were combined to form a single, daily victimization item. Given that intercorrelations across victimization items tend to be moderate to high, it is not uncommon to combine items across different victimization forms (e.g., Bellmore and Cillessen 2006; Juvonen et al. 2011)

Daily Distress

The psychosocial adjustment indicator, distress, was assessed with seven items from the anxiety and depression sub-scales of the Profile of Moods States (POMS; Lorr and McNair 1971). The items are prefaced with “The following is a list of feelings or experiences. How much did you experience them today?” Each evening, adolescents rated the extent to which they had anxious feelings (items include: on edge, nervous, uneasy and unable to concentrate) and depressive feelings (items include: discouraged, hopeless and sad). The items are rated on a 5-point scale labeled not at all (1) and extremely (5) at its end points. Given the high correlation (r = .80, p < .001) between the anxiety and depressive feelings subscales, they were combined to form an index of psychological distress (α = .90). The daily distress measure has been used before in adolescent studies (e.g., Fuligni and Masten 2010; Telzer and Fuligni 2009).

Daily Physical Symptoms

Three items were used to assess physical symptoms. Participants indicated whether they had headaches, trouble sleeping and back, joint or muscle pain on a 5-point scale ranging from not at all to extremely such that higher values indicate more symptoms. The measure showed good internal reliability (α = .74).

Daily School Adjustment

To assess school adjustment, two measures were used: academic problems and perceived role fulfillment as a good student.

Academic Problems

A single checklist item was used to assess academic problems. Participants reported whether they did poorly on a test, quiz or homework. Given that this is a binary (0 = no, 1 = yes), single item an alpha coefficient cannot be calculated.

Role Fulfillment as a Good Student

To assess adolescents’ perceived role fulfillment as good students, each evening they responded to a single item asking how much they felt like a good student during the day on a 7-point scale ranging from not at all to extremely. Higher values indicate stronger feelings of role fulfillment.

Results

Descriptive results based on traditional mean differences to examine overall frequencies and trends in peer victimization experiences are presented before describing the results from the hierarchical linear modeling (HLM; Bryk and Rauden-bush 1992) analyses. The HLM models simultaneously tested the mean, between-persons and daily, within-persons associations between adolescents’ victimization experiences and their psychological distress, physical symptoms and school adjustment, which controlling for school attended. Finally, based on the results from the HLM models, the mediation analysis examining whether psychological distress accounts for potential associations between peer victimization incidents and school adjustment are presented.

Peer Victimization: Overall Frequencies and Group Differences

Daily peer victimization reports were averaged across all school days to create a score that indicated the proportion of days that students reported victimization incidents. On average, victimization occurred on 6 % of days (M = .06, SD = .15). Overall, 26 % of adolescents reported at least one incident across the school days such that 13 % reported one incident, 8 % reported two incidents and 5 % reported three or more victimization incidents in a two-week span. Independent samples t tests revealed no gender t(358) = .19, p >.05, or grade differences t(358) = .96, p > .05. To test generational status differences, a one-way analysis of variance test was run and the results revealed a significant difference, F(2, 357) = 3.91, p = .02, η2 = .02. Post hoc tests showed that third generation Mexican-American students (M = .11, SD = .02) reported more victimization than first generation Mexican-American students (M = .03, SD = .02).

Peer Victimization Associations with Distress, Physical Symptoms and School Adjustment

HLM was used to test the extent to which both mean- and daily-levels of peer victimization (chronic and episodic, respectively) predict adolescents’ distress, physical symptoms and school adjustment problems. Additional analyses were conducted to test for individual differences in the daily-level associations based on Mexican-American adolescents’ grade, gender or generational status. Although there were no differences in peer victimization incidents across the two schools (p < .05), we also controlled for school effects in the models. HLM2 models in the Hierarchical Linear Modeling software (Version 6; Raudenbush et al. 2004) were run which can handle missing data at Level 1 (i.e., daily level) by listwise deletion when the analysis is run. A noted advantage of HLM is that it is able to calculate the intercepts and slopes as long as some data points exist for the individual. Thus, even those participants who are missing data on some days are included in the analyses.

In the HLM models, a mean-level victimization predictor was entered at the intercept of Level 2 to indicate whether students who on average report more peer victimization are also on average, more likely to report adjustment problems. The daily-level predictor, entered at Level 1, extends the mean-level variable inclusion by examining whether adolescents experienced more distress, physical symptoms and school adjustment problems on days that they were victimized by peers at school. Given that the mean-level victimization predictor (grand-mean centered) is included in the models, this between-persons variation was removed from the daily-level peer victimization predictor by group mean centering the level 1 predictor (West et al. 2011). To group mean center, the raw score of victimization each day was transformed into values that represent the daily deviation from an adolescent’s average victimization (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002). That is, the group mean centered, daily victimization predictor captures the within-subject fluctuations across the two-week span. Via the method of centering and including victimization predictors at both levels of the models, the overall effect of victimization was partitioned into distinct between-persons effect and within-persons effect (West et al. 2011), allowing us to capture the associations with both chronic and episodic victimization incidents.

Five models were estimated in which each outcome was predicted from adolescents’ victimization experiences. For example, the Level 1 equation estimated to predict daily academic problems from peer victimization was:

| (1) |

In this model, academic problems on a particular day (i) for a particular adolescent (j) is modeled as a function of the adolescents’ intercept, or the average academic problems across days (b0j) and daily fluctuations in peer victimization (i.e., group mean centered victimization; b1j). The error term (eij) accounts for variance in academic problems that is unexplained by the predictors. The basic Eq. 1 model predicting daily academic problems also included the following individual-level equations for Level 2:

| (2) |

| (3) |

In Eq. 2, average victimization (c01) represents the relationship between mean levels of victimization and academic problems. School (c02) attended also was controlled for and this variable was effect coded (i.e., −1 and 1 codes). The coefficients u0j and u1j account for the remaining variance in the intercept and slope that is not explained by the other variables in the model.

The results from the models are shown in Table 2. In predicting adolescents’ distress, results revealed that adolescents who, on average, report higher levels of victimization, also report feeling more distress. However, adolescents did not report feeling more distress on any given day that they deviated from their average level of victimization. That is, the mean-level victimization predictor was associated significantly with distress, but not the daily-level predictor. In predicting physical symptoms neither mean- nor daily-level peer victimization was significant. However, results from the additional school adjustment indicators revealed that adolescents who on average reported more victimization incidents also reported more academic problems. Yet, mean levels of victimization did not significantly predict the adolescent’s perceived role fulfillment as a good student. Even after accounting for the mean-level victimization associations and school effects, results showed that adolescent’s reported more academic problems and felt like less of a good student on days that they deviated from their own average levels of daily victimization.

Table 2.

Hierarchical linear modeling with mean and daily peer victimization experiences as predictors

| Distress |

Physical symptoms |

Academic problems |

Role fulfillment |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | |

| Intercept | 1.59*** | .04 | 1.58*** | .04 | .14*** | .01 | 4.05*** | .12 |

| L1 daily peer victimization | .08 | .05 | .05 | .07 | .10** | .04 | −.22* | .11 |

| L2 mean peer victimization | .55* | .23 | .32 | .22 | .29** | .09 | −.80 | .66 |

| School | −.05 | .04 | .02 | .04 | −.01 | .01 | .78*** | .12 |

| Standard deviation estimate | .11*** | .03 | .23*** | .05 | ||||

Four separate HLM models are shown. Peer victimization coefficients represent unstandardized estimates of the daily-level association. The “standard deviation estimate” is the estimate of the degree of individual variability in the estimates of the daily associations between victimization and each of the outcomes (e.g., distress, physical symptoms)

p <.05,

p <.01,

p <.001

Estimates of the degree of individual variability in the daily-level associations are also presented in Table 2. There was significant individual variability in the association of daily peer victimization with distress and academic problems. The individual variability in the association between victimization and physical symptoms and perceived role fulfillment as a good student was non-significant. The non-significant findings in the estimates of individual variability suggest that the impact of peer victimization on physical symptoms and perceived role fulfillment as a good student was generally similar across adolescents. Thus, the extent to which these associations vary by factors such as gender are not examined.

Do Gender, Grade and Generational Status Explain Significant Variability?

Additional HLM models examined whether the significant variability found in the daily-level associations of victimization with distress and academic problems can be explained by gender, grade or generational status differences. For example, the basic Eq. 1 model predicting daily academic problems included the following individual-level equations:

| (4) |

| (5) |

The gender (male = – 1, female =1) and grade (ninth grade = – 1, tenth grade =1) variables were effect coded and generational status was dummy coded (first generation = 0, second generation = 1, third generation = 1) with the first generation Mexican-American students as the baseline group. Equation 4 tests whether there are average victimization, gender, grade or generational status differences in the intercept, or the average daily academic problems. Equation 5 tests whether the daily association of victimization with academic problems is predicted by the adolescents’ gender, grade or generational status. The coefficients u0j and u1j account for the remaining variance in the intercept and slope that is not explained by the variables in the model. The same models were run with distress as the outcome variable.

The results indicated that for distress, there was a significant association of gender with the intercept, or average daily distress, such that girls tend to report higher levels of distress at the daily level (b = .08, SE = .03, p = .007). Similarly to the previously tested models, average levels of victimization was associated with distress. No other significant findings emerged at the intercept level or the slope. In the model with academic problems, results indicated that gender, grade and generational status did not account for the variability in the daily associations with school bullying.

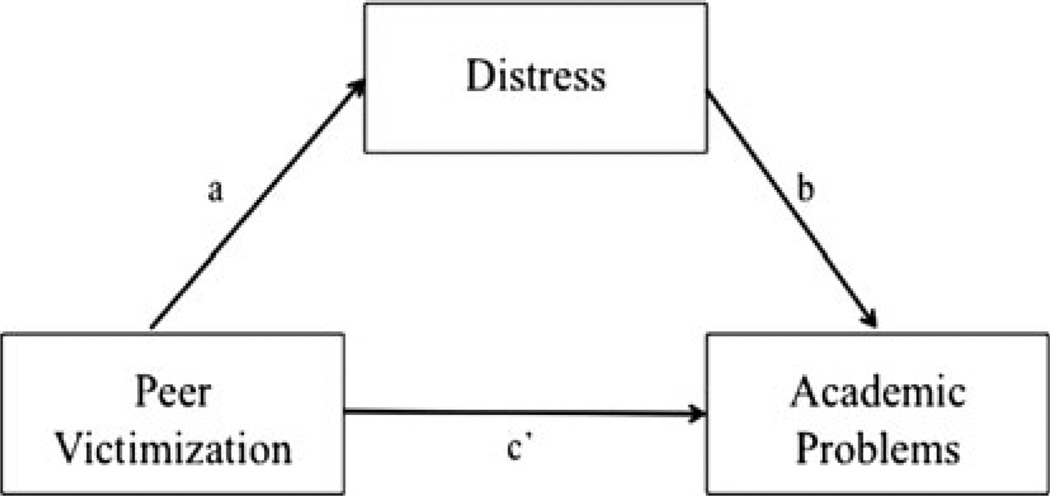

Testing the Mediating Role of Distress

At the mean-level, chronic peer victimization was associated with distress and academic problems. Thus, the mediation hypotheses in which mean levels of distress explain the association between peer victimization and this school adjustment indicator, at the mean-level was tested (see Fig. 1). Given that the mediation tests focused on the individual level links, analyses moved from HLM to ordinary least squares with hierarchical linear regression analyses. All models controlled for school, grade, gender and generational status. First, the necessary conditions for examining mediation such as significant associations between the main predictor and the mediator were established (Baron and Kenny 1986). Path analyses were subsequently conducted to estimate direct and indirect effects between victimization and academic problems (MacKinnon et al. 2007). The test of the mediated effect (Sobel 1982) resulted in a significant mediation effect (z = 2.28, p = .02) and distress accounted for 11 % of the effect of victimization on academic problems. Post hoc tests were conducted using the PRODCLIN program (MacKinnon et al. 2007), which computes asymmetric confidence limits based on the distribution of products. MacKinnon et al. (2007) assert that these confidence limits are more powerful and produce more accurate Type 1 error rates, compared to Baron and Kenny’s (1986) method. Results revealed that the confidence interval (CI: .01–.07) does not include zero, consistent with a statistically significant mediation. The results suggest that, on average, adolescents who experienced more victimization incidents were more likely to report higher distress levels, such as sadness and anxiety and this, in turn, partially explained why they tend to have more academic problems.

Fig. 1.

Between-persons mediation models with distress as the mediator in the association of peer victimization with academic problems

Discussion

The current study extended prior peer victimization research by addressing several gaps in the existing peer victimization literature. We focused on the experiences of Mexican-American high school students, a rapidly growing segment of the population that is at risk for psychosocial and academic maladjustment (Hill et al. 2003; Joiner et al. 2001; Ream and Rumberger 2008), but one that continues to be understudied, particularly in peer relations research. Moreover, this study relied on daily reports (Bolger et al. 2003), a methodology largely underutilized in peer victimization, to demonstrate that everyday victimization experiences among Mexican-American adolescents are associated with heightened distress and school adjustment problems. Furthermore, to better understand whether distress serves as a mediating mechanism in the association between peer victimization and academic problems a mediation model was tested and support was found for this model. Overall, the results from the current study contribute to the existing literature in several ways, highlighting the importance of studying day-to-day peer victimization experiences among Mexican-American adolescents.

Findings regarding the prevalence of peer victimization and group differences revealed that everyday victimization incidents were not uncommon among Mexican-American high school students; one-fourth of adolescents reported experiencing at least one incident of verbal or physical victimization across a two-week period. Reports of victimization did not differ among ninth and tenth graders suggesting that victimization experiences remain stable at least during the first two years of high school. There were also no differences by gender. Although there is some evidence from prior studies that victimization rates differ between boys and girls, the few studies that have focused on Mexican-American children (Bauman 2008) and adolescents (Bauman and Summers 2009) have found no gender differences. Interestingly, third generation Mexican-American adolescents were more likely to report victimization incidents compared to first generation Mexican-American adolescents. One explanation is that more acculturated, third-generation adolescents may be more likely to place greater importance on peer relationships rather than family relationships, spend more time with peers and, thus, simply have more interactions and opportunities to be targeted by peers. It has been speculated that first-generation Mexican immigrant adolescents in U.S. high schools have smaller, tightly knit peer groups, and therefore, they might shield themselves and stay better protected from negative interactions with the dominant-culture peer group (Matute-Bianchi 1986; Wall et al. 1993). Future research across various developmental periods is needed to better understand how the generational status or acculturation level of Mexican-American youth may influence their vulnerability to be targeted by peers at school.

Adolescents’ reports of school peer victimization experiences were associated with their adjustment across several domains, including psychosocial and school adjustment. Specifically, both chronic and episodic victimization by peers was associated with academic problems. Why may peer victimization be associated with whether an adolescent does poorly on an academic assignment? One explanation is that the targeted teen may feel too upset and distracted after the incident, which leads them to do poorly on a quiz or test. That is, the unpleasant experience (captured by their levels of distress) of being victimized by peers may make it difficult for a student to do well academically. Indeed, mediation results revealed that distress accounted for the association between peer victimization and academic problems. This is consistent with and extends past research of indirect models among middle school students in which psychosocial maladjustment mediated the association between victimization and school functioning, specifically GPA (Nishina et al. 2005). Furthermore, past research has highlighted that negative emotions resulting from peer victimization, such as anxiety and anger, are incompatible with specific school outcomes such as school liking or attentional focus during class activities (e.g., Erath et al. 2008; Wentzel 1999) which is in line with the results found in this study. To our knowledge, this is the first study to show that daily peer victimization incidents among Mexican-American youth are associated with school problems. Given the many scholastic difficulties faced by Latino youth, particularly Mexican-American youth, it is critical to identify factors that may be contributing to their lower school performance and engagement. The role of peers among Mexican-American youth is often overshadowed by the emphasis placed on home and family factors. These results show that negative peer interactions also may help explain why students struggle with academic tasks.

In the current study, there were also distinct findings based on the chronic and episodic predictors included in the analyses that highlight the usefulness of understanding victimization experiences at both levels. Consistent with research from traditional survey methods, students who reported more victimization incidents reported greater psychosocial adjustment problems (Rigby and Slee 1999). However, in contrast to previous research showing that on days when adolescents were victimized at school they were more likely to report negative affect (e.g., anger, anxiety; Nishina and Juvonen 2005), this study found that after accounting for chronic victimization experiences, there is no daily association between distress and victimization. Moreover, there was no association between chronic peer victimization and physical symptoms. The lack of findings suggests that associations with physical symptoms may not be fully captured within a short period of time. That is, it may be that peer victimization does not result in headaches or pains during the same day of the incident or from chronic experiences spanning a couple of weeks. Rather, it may be adolescents who across longer periods of time (i.e., weeks, months) experience more peer victimization incidents and who have a stress response that is more often activated who are more likely to report physical symptoms. Indeed, the chances of disease or illness are heightened when stress responses are chronically activated (Sapolsky 2004). Moreover, research on discrimination experiences among adolescents suggests that anxiety or rumination about negative events across time may lead to physiological responses that translate into physical symptoms such as pains and trouble sleeping (Huynh and Fuligni 2010). A similar process may be occurring among Mexican-American adolescents who are victimized by peers at school and future research should examine whether long-term victimization experiences are associated with physical symptoms among this population.

In addition, episodic peer victimization experiences were related negatively with perceived role fulfillment as a good student, but not with chronic victimization. That is, in general, students who reported more victimization experiences did not differ in their overall sense of being a good student, yet, on any given day that an adolescent was victimized at school they were less likely to feel like a good student on the same day. Past research suggests that as children experience victimization at school, their sense of relatedness or belongingness within the school context wavers (Buhs 2005; Furrer and Skinner 2003) and that students who are victimized tend to report less positive perceptions of their schoolwork and academic ability (Neary and Joseph 1994). This study extends research by showing that any given incident of peer victimization is associated with an immediate lowered sense of being a good student.

Despite the strengths and contributions of the current study in our understanding of Mexican-American adolescents’ daily experiences with peer victimization, there are limitations that are important to note. For example, the reliance on self-report items and the small number of items used to assess each construct are limitations of the study, including the single item used to assess academic problems. Yet, single-item indicators of behaviors or events are not atypical in daily checklist studies (e.g., Almeida et al. 2001; Chung et al. 2009), given the need to keep reporting demands for participants limited across a study period of two or more weeks. Also, it is unknown if these findings generalize to other students from Mexican-American backgrounds. The participants in this study attended urban high schools comprised of predominately Latino students and most were second-generation. Thus, additional research among Mexican-American youth from varying backgrounds is needed to further examine how daily peer victimization experiences are associated with their adjustment.

Another limitation of the current study is that the significant variability in the daily level associations of school victimization with adjustment was not explained by the factors examined, which included gender, grade and generational status. Future research should investigate additional factors that may help explain why victimization is more strongly or weakly associated with adjustment outcomes among Mexican-American adolescents. For example, past research has provided strong evidence for the protective function of family factors. In particular, familism includes placing a high value on familial relationships and feeling a sense of obligation to one’s family (Marín and Marín 1991). Familism tends to be higher among adolescents from Latin American backgrounds such as Mexico compared to adolescents from other ethnic groups (e.g., Telzer and Fuligni 2009). These family values may serve a protective role for children and teens because familism provides a dependable and stable source of social and emotional support for youth (Azmitia et al. 2009; Gonzales et al. 2008). Among a study Mexican-American adolescents, Berkel et al. (2010) found that holding stronger culturally related values (e.g., emotional and obligation familism) reduced the risk of discrimination experiences impacting academic outcomes. Thus, future research should test whether specific family factors, such as familism or emotional support from parents, reduce the distress, physical symptoms or school problems that result from peer victimization experiences.

The findings from the current study showing that episodic and chronic peer victimization incidents are associated with maladjustment among Mexican-American adolescents leads to the question: how can peer victimization incidents be reduced? Several school-based interventions have shown promise in reducing the incidence of peer victimization (i.e., school bullying; Olweus 1996; Salmivalli et al. 2005; also see Smith et al. 2004 for a review). However, it is important to consider whether these interventions might show similar results in a school of predominately Latino adolescents. For example, interventions shown to be effective with some communities, such as middle-class communities, may not be effective in poor, urban communities (Nakamoto and Schwartz 2011). Given that examining mediating mechanisms is important for identifying points of intervention (Shrout and Bolger 2002), the mediation results from the current study suggest that reducing the feelings of distress that result from Mexican-American adolescents’ victimization experiences, in turn, can reduce the more distal associations with school adjustment (i.e., academic problems). Additionally, based on findings with a sample of predominately Latino children showing that peer victimization was associated with poor school engagement and GPA, Nakamoto and Schwartz (2011) suggest that incorporating a school engagement emphasis into bullying programs may break the link between victimization and academic adjustment. Future applied research with Latino youth that tests the effectiveness of bullying interventions will be critical to better understand if prior intervention strategies are equally effective among Latino adolescents.

Across schools, serving children and adolescents from all ethnic backgrounds, peer victimization is an important problem that needs to be addressed. The current study demonstrates that school peer victimization has psychosocial and scholastic implications for Mexican-American adolescents in the first years of high school. It is especially critical to address peer victimization because of their school-related implications. That is, although there are several factors aside from peer relationships that contribute to the dire academic outcomes among Mexican-American adolescents, addressing peer victimization problems in schools appears to be one promising method for improving their school adjustment

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funding through the National Institute of Child and Human Development (R01HD057164). We would like to thank Dr. Thomas Weisner for his feedback on the manuscript and the school principals, teachers and students for their participation in this project.

GE: participated in the design and coordination of the study, performed statistical analyses, drafted initial manuscript, primarily authored the manuscript. NG: acquisition of funding, conceived of the study, participated in the design and coordination of the study, provided feedback on drafts of manuscript. AF: acquisition of funding, conceived of the study, participated in the design and coordination of the study, assisted with interpretation of data, provided feedback on drafts of manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Biographies

Guadalupe Espinoza is a doctoral candidate in the Psychology Department at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), specializing in Developmental Psychology. Her major research interests include adolescent’s social interactions with peers in both the school and online contexts, with a particular focus on ethnic minority youth from Latin American backgrounds.

Nancy A. Gonzales is ASU Foundation Professor of Psychology and Director of the Prevention Research Center at Arizona State University. Her research examines cultural and contextual influences on the social, academic and psychological development of children in low income communities. The ultimate aims of this work are to advance understanding of how children adapt to the demands of their immediate social environments, and to translate finding into community-based intervention that are effective at promoting successful adaptation and reducing health disparities for high-risk youth and families.

Andrew J. Fuligni is a Professor at the University of California, Los Angeles. He received his doctorate in Developmental Psychology from the University of Michigan. His major research interests include adolescent development and social relationships among Asian, Latino, and immigrant families.

Contributor Information

Guadalupe Espinoza, UCLA Department of Psychology, University of California, Los Angeles, 1285 Franz Hall, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1563, USA, g.espinoza@ucla.edu.

Nancy A. Gonzales, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA

Andrew J. Fuligni, Departments of Psychology and Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA

References

- Almeida DM, Wethington E, McDonald DA. Daily variation in paternal engagement and negative mood: Implications for emotionally supportive and conflictual interactions. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:417–429. [Google Scholar]

- Azmitia M, Cooper CR, Brown JR. Support and guidance from families, friends, and teachers in Latino early adolescents’ math pathways. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2009;29(1):142–169. [Google Scholar]

- Baldry AC, Farrington DP. Protective factors as moderators of risk factors in adolescence bullying. Social Psychology of Education. 2005;8:263–284. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK, Olsen JA. Assessing the transitions to middle and high school. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2004;19:3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman S. The association between gender, age, and acculturation, and depression and overt and relational victimization among Mexican American elementary students. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2008;28(4):528–554. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman S, Summers JJ. Peer victimization and depressive symptoms in Mexican American middle school students: Including acculturation as a variable of interest. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2009;31(4):515–535. [Google Scholar]

- Bellmore AD, Cillessen AHN. Reciprocal influences of victimization, perceived social preference, and self-concept in adolescence. Self and Identity. 2006;5(3):209–229. [Google Scholar]

- Bellmore AD, Witkow MR, Graham S, Juvonen J. Beyond the individual: The impact of ethnic context and classroom behavioral norms on victims’ adjustment. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40(6):1159–1172. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, Graham S. The transition to high school as a developmental process among multiethnic urban youth. Child Development. 2009;80(2):356–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C, Knight GP, Zeiders KH, Tein J, Roosa MW, Gonzales NA, et al. Discrimination and adjustment for Mexican American adolescents: A prospective examination of the benefits of culturally related values. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2010;20(4):893–915. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00668.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Davis A, Rafaeli E. Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annual Reviews of Psychology. 2003;54:579–616. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond L, Carlin JB, Thomas L, Rubin K, Patton G. Does bullying cause emotional problems? A prospective study of young teenagers. British Medical Journal. 2001;323:480–484. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7311.480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW. Hierarchical linear models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Buhs ES. Peer rejection, negative peer treatment, and school adjustment: Self-concept and classroom engagement as mediating processes. Journal of School Psychology. 2005;43:407–424. [Google Scholar]

- Buhs ES, Ladd GW. Peer rejection as an antecedent of young children’s school adjustment: An examination of mediating processes. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37(4):550–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung GH, Flook L, Fuligni AJ. Daily family conflict and emotional distress among adolescents from Latin American. Asian and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45(5):1406–1415. doi: 10.1037/a0014163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NE, Bigbee MA, Howes C. Gender differences in children’s normative beliefs about aggression: How do I hurt thee? Let me count the ways. Child Development. 1996;67(3):1003–1014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA. Translational science in action: Hostile attributional style and the development of aggressive behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18:791–814. doi: 10.1017/s0954579406060391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumka LE, Gonzales NA, Bonds DD, Millsap RE. Academic success of Mexican origin adolescent boys and girls: The role of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting and cultural orientation. Sex Roles. 2009;60:588–599. doi: 10.1007/s11199-008-9518-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erath SA, Flangan KS, Bierman KL. Early adolescent school adjustment: Associations with friendship and peer victimization. Social Development. 2008;17(4):853–870. [Google Scholar]

- Fekkes M, Pijpers FIM, Fredriks AM, Vogels T, Verloove-Vanhorick SP. Do bullied children get ill, or do ill children get bullied? A prospective cohort study on the relationship between bullying and health-related symptoms. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1568–1574. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick KM, Dulin A, Piko B. Bullying and depressive symptomatology among low-income, African-American youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39:634–645. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9426-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Masten CL. Daily family interactions among young adults in the United States from Latin American, Filipino, East Asian, and European backgrounds. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2010;34(6):491–499. [Google Scholar]

- Furrer C, Skinner E. Sense of relatedness as a factor in children’s academic engagement and performance. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2003;95:148–162. [Google Scholar]

- García Coll C, Crnic K, Lamberty G, Wasik BH, Jenkins R, García HV, et al. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development. 1996;67(5):1891–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gini G, Pozzoli T. Association between bullying and psychosomatic problems: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2009;123:1059–1065. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Germán M, Kim SY, George P, Fabrett F, Millsap R, et al. Mexican American adolescents’ cultural orientation, externalizing behavior and academic engagement: The role of traditional cultural values. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;41(1-2):151–164. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9152-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham S. Peer victimization in school: Exploring the ethnic context. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15:317–321. [Google Scholar]

- Han W. The academic trajectories of children of immigrants and their school environments. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(6):1572–1590. doi: 10.1037/a0013886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanish LD, Guerra NG. The roles of ethnicity and school context in predicting children’s victimization by peers. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28(2):201–223. doi: 10.1023/A:1005187201519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill NE, Bush KR, Roosa MW. Parenting and family socialization strategies and children’s mental health: Low-income Mexican-American and Euro-American mothers and children. Child Development. 2003;74(1):189–204. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill NE, Torres K. Negotiating the American dream: The paradox of aspirations and achievement among Latino students and engagement between their families and schools. Journal of Social Issues. 2010;66(1):95–112. [Google Scholar]

- Huynh VW, Fuligni AJ. Discrimination hurts: The academic, psychological, and physical well-being of adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2010;20(4):916–941. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Perez M, Wagner KD, Berenson A, Marquina GS. On fatalism, pessimism, and depressive symptoms among Mexican-American and other adolescents attending an obstetrics-gynecology clinic. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2001;39:887–896. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(00)00062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen J, Graham S, Schuster MA. Bullying among young adolescents: The strong, the weak, and the troubled. Pediatrics. 2003;112:1231–1237. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.6.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen J, Wang Y, Espinoza G. Bullying experiences and compromised academic performance across middle school grades. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2011;31(1):152–173. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman P, Chen X, Choy SP, Ruddy SA, Miller AK, Chandler KA, et al. Indicators of school crime and safety (NCES 1999-057/NCJ-178906) Washington, DC: Departments of Education and Justice; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kochenderfer BJ, Ladd GW. Peer victimization: Cause or consequence of school maladjustment. Child Development. 1996;67:1305–1317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochenderfer BJ, Ladd GW. Victimized children’s responses to peers’ aggression: Behaviors associated with reduced versus continued victimization. Development and Psy-chopathology. 1997;9:59–73. doi: 10.1017/s0954579497001065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler A, Lazarín M. Hispanic education in the United States. Washington, DC: National Council of La Raza; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kupersmidt JB, Coie JD. Preadolescent peer status and aggression as predictors of externalizing behavior problems in adolescence. Child Development. 1990;61:1350–1362. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupersmidt JB, Coie JD, Dodge KA. The role of poor peer relationships in the development of disorder. In: Asher SR, Coie JD, editors. Peer rejection in childhood. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1990. pp. 274–305. [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, Harrison HM. Adolescent peer relations, friendships, and romantic relationships: Do they predict social anxiety and depression? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:49–61. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurenceau J, Barrett LF, Rovine MJ. The interpersonal process model of intimacy in marriage: A daily-dairy approach and multilevel modeling approach. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19(2):314–323. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman BJ, Repetti RL. Bad days don’t end when the school bell rings: The lingering effects of negative school events on children’s mood, self-esteem, and perceptions of parent-child interaction. Social Development. 2007;16:596–618. [Google Scholar]

- Lorr M, McNair DM. The profile of mood states manual. San Diego, CA: Educational and Industrial Testing Service; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fritz MS, Williams J, Lockwood CM. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behavioral Research Methods. 2007;39:1–12. doi: 10.3758/bf03193007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín G, Marín BV. Research with Hispanic populations. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Matute-Bianchi ME. Ethnic identities and patterns of school success and failure among Mexican-descent and Japanese-American students in a California high school: An ethnographic analysis. American Journal of Education. 1986;95:233–255. [Google Scholar]

- McKenney KS, Pepler D, Craig W, Connolly J. Peer victimization and psychosocial adjustment: The experiences of Canadian immigrant youth. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology. 2006;9(4):239–264. [Google Scholar]

- Mehan H, Villanueva I, Hubbard L, Lintz A. Constructing school success: The consequences of untracking low-achieving students. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Menesini E, Modena M, Tani F. Bullying and victimization in adolescence: Concurrent and stable roles and psychological health symptoms. The Journal of Genetic Psychology. 2009;170(2):115–133. doi: 10.3200/GNTP.170.2.115-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamoto J, Schwartz D. Is peer victimization associated with academic achievement? A meta-analytic review. Social Development. 2010;19:221–242. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamoto J, Schwartz D. The association between peer victimization and functioning at school among urban Latino children. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2011;32:89–97. [Google Scholar]

- Nansel TR, Overpeck M, Pilla RS, Ruan WJ, Simons-Morton B, Scheidt P. Bullying behaviors among US Youth: Prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. Journal of American Medical Assocition. 2001;285(16):2094–2100. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.16.2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National High School Center, American Institutes for Research. Approaches to dropout prevention: Heeding early warning signs with appropriate interventions. 2007 Retrieved from www.betterhighschools.org/docs/nhsc_approachestodropoutpre vention.pdf.

- Naylor P, Cowie H, del Rey R. Coping strategies of secondary school children in response to being bullied. Child Psychology and Psychiatry Review. 2001;6:114–120. [Google Scholar]

- Neary A, Joseph S. Peer victimization and its relationship to self-concept and depression among schoolgirls. Personality and Individual Differences. 1994;16:183–186. [Google Scholar]

- Nishina A, Juvonen J. Daily reports of witnessing and experiencing peer harassment in middle school. Child Development. 2005;76(2):435–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishina A, Juvonen J, Witkow MR. Sticks and stones may break my bones, but names will make me feel sick: The psychosocial, somatic, and scholastic consequences of peer harassment. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34(1):37–48. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D. Bullying at school: Knowledge base and an effective intervention program. Annals of the New York Academy of Science. 1996;794(1):265–276. [Google Scholar]

- Pepler DJ, Carig WM, Connolly JA, Yuile A, McMaster L, Jiang D. A developmental perspective on bullying. Aggressive Behavior. 2006;32(4):376–384. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Hispanic Research Center. Statistical portrait of Hispanics in the United States, 2009. 2011 Retrieved from: http://pewhispanic.org/factsheets/factsheet.php?factsheetID=70.

- Raudenbush S, Bryk A. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. New York: Sage Publications Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS, Congdon R. HLM 6 for Windows [computer software] Skokie, IL: Scientific Software International, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ream RK, Rumberger RW. Student engagement, peer social capital, and school dropout among Mexican American and non-Latino White students. Sociology of Education. 2008;81:109–139. [Google Scholar]

- Repetti RL. The effects of perceived daily social and academic failure experiences on school-age children’s subsequent interactions with parents. Child Development. 1996;67:1467–1482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigby K, Slee P. Children, involvement in bully-victim problems, and perceived social support. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 1999;29(2):119–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Chen YR. Ethnocultural differences in prevalence of adolescent depression. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1997;25:95–110. doi: 10.1023/a:1024649925737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmivalli C, Kaukiainen A, Voeten M. Anti-bullying intervention: Implementation and outcome. British Journal of Educational Psychology. 2005;75:465–487. doi: 10.1348/000709905X26011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky RM. Social status and health in humans and other animals. Annual Review of Anthropology. 2004;33:393–418. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(4):422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, Schneider BH, Smith PK, Ananiadou K. The effectiveness of whole-school antibullying programs: A synthesis of evaluation research. School Psychology Review. 2004;33(4):547–560. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology. 1982;13:290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Stone S, Han M. Perceived school environments, perceived discrimination, and school performance among children of Mexican immigrants. Children and Youth Services Review. 2005;27:51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Strohmeier D, Kä rnä A, Salmivalli C. Intrapersonal and interpersonal risk factors for peer victimization in immigrant youth in Finland. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47(1):248–258. doi: 10.1037/a0020785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telzer EH, Fuligni AJ. Daily family assistance and the psychological well-being of adolescents from Latin American. Asian and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45(4):1177–1189. doi: 10.1037/a0014728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tharp-Taylor S, Haviland A, D’Amico EJ. Victimization from mental and physical bullying and substance use in early adolescence. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:561–567. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Updegraff KA, McHale SM, Whiteman SD, Thayer SM, Delgado MY. Adolescent sibling relationships in Mexican American families: Exploring the role of familism. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:512–522. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. School enrollment. Washington DC: U.S. Department of Commerce; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wall JA, Power TG, Arbona C. Susceptibility to antisocial peer pressure and its relation to acculturation in Mexican-American adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1993;8(4):403–418. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Iannotti RJ, Nansel TR. School bullying among adolescents in the United States: Physical, verbal, relational, and cyber. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;45:368–375. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wayman JC. Student perceptions of teacher ethnic bias: A comparison of Mexican- American and non-Latino white dropouts and students. The High School Journal. 2002;85(3):27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel KR. Social-motivational processes and interpersonal relationships: Implications for understanding motivation at school. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1999;91(1):76–97. [Google Scholar]

- West SG, Ryu E, Kwok O, Cham H. Multilevel modeling: Current and future applications in personality research. Journal of Personality. 2011;79:2–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]